Filter, Wrapper, and RFE: A Practical Guide to Feature Selection in Cheminformatics

This article provides a comprehensive guide to feature selection methods for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Filter, Wrapper, and RFE: A Practical Guide to Feature Selection in Cheminformatics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to feature selection methods for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational concepts of filter, wrapper, and embedded methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), detailing their mechanisms and ideal use cases in cheminformatics. The content covers practical applications in drug discovery, from sensitivity prediction to molecular property modeling, and addresses common challenges such as data imbalance and computational cost. Through comparative analysis and validation techniques, it offers strategic advice for selecting and optimizing feature selection pipelines to build interpretable, robust, and high-performing machine learning models, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery process.

Demystifying Feature Selection: Core Concepts for Cheminformatics

Why Feature Selection is Critical in Cheminformatics

In the field of cheminformatics, the analysis of chemical data to support drug discovery and development consistently grapples with a central challenge: the curse of dimensionality. Modern high-throughput screening and computational chemistry experiments routinely generate datasets where the number of molecular descriptors or features—such as physicochemical properties, topological indices, and quantum chemical parameters—far exceeds the number of compounds tested. This high-dimensional, small-sample-size problem is analogous to those encountered in microarray gene expression analysis [1] and metabarcoding datasets [2], where thousands to hundreds of thousands of features may be measured across a relatively limited set of biological samples. In such scenarios, feature selection transitions from a mere optimization step to an absolute necessity for building robust, interpretable, and predictive models.

The criticality of feature selection in cheminformatics extends beyond mere performance metrics. It directly influences the scientific validity and translational potential of computational models. Redundant and irrelevant features not only obfuscate the underlying structure-activity relationships but also increase the risk of model overfitting, where a model memorizes noise in the training data instead of learning generalizable patterns [1] [3]. This can have significant practical consequences, leading to failed experimental validation and wasted resources in drug development campaigns. Furthermore, by isolating the most informative molecular descriptors, feature selection enhances model interpretability, providing medicinal chemists with tangible insights into the structural and physicochemical drivers of biological activity, which in turn can guide the rational design of novel compounds [4].

This article objectively compares the performance of three predominant feature selection paradigms—filter, wrapper, and embedded methods—with a specific focus on the role of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) within the wrapper category. By synthesizing evidence from benchmark studies across related computational biology domains and outlining detailed experimental protocols, we aim to provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting and optimizing feature selection strategies in cheminformatics applications.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methodologies

Feature selection techniques are broadly classified into three categories based on their interaction with the predictive model and their search mechanisms. Understanding the fundamental principles, strengths, and weaknesses of each is crucial for their appropriate application.

Filter Methods: The Efficient First Pass

Filter methods assess the relevance of features based on intrinsic data properties, such as statistical measures or correlation coefficients, independently of any machine learning model. They operate as a preprocessing step, filtering out features that fall below a certain relevance threshold.

- Principle of Operation: These methods typically rank all features according to a scoring metric (e.g., correlation with the target variable, mutual information, or chi-squared test) and select the top-k ranked features [3]. The selected subset is then used to train a classifier or regression model.

- Advantages: Their primary advantage is computational efficiency and scalability. Since they do not involve model training, they are very fast, making them suitable for a preliminary reduction of ultra-high-dimensional feature spaces, such as those derived from molecular fingerprints or gene expression data [5] [3]. They also help to avoid overfitting at the feature selection stage due to their model-agnostic nature.

- Disadvantages: A major limitation is that they ignore feature dependencies and interactions with the model. By evaluating features in isolation, they may select redundant features that are individually relevant but do not contribute new information to the model, potentially leading to suboptimal performance [3].

Wrapper Methods: The Performance-Oriented Optimizer

Wrapper methods utilize the performance of a specific machine learning model as the objective function to evaluate and search for the optimal feature subset. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a prominent and widely adopted wrapper method.

- Principle of Operation: RFE operates through a recursive process. It starts with the full feature set, trains a model, and ranks the features based on a model-derived importance metric (e.g., regression coefficients for linear models, or Gini importance for tree-based models). The least important features are then pruned, and the process repeats with the reduced set until a predefined number of features remains [6] [7]. This iterative re-training and re-ranking allow RFE to re-evaluate feature importance in the context of the remaining features.

- Advantages: Wrapper methods, including RFE, generally achieve higher predictive accuracy than filter methods because they are tuned to the specific inductive biases of the learning algorithm [5] [7]. They effectively capture feature interactions.

- Disadvantages: The primary drawback is high computational cost. The need for repeated model training makes them significantly more resource-intensive than filter methods, which can be prohibitive for very large datasets [3]. They also carry a higher risk of overfitting to the training data if not properly validated.

Embedded Methods: The Balanced Integrator

Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. They perform feature selection as a built-in part of the learning process.

- Principle of Operation: These methods leverage the internal structure of learning algorithms to obtain feature importance. A classic example is the Lasso (L1-regularized) regression, which penalizes the absolute size of coefficients, driving the coefficients of less important features to zero, effectively performing feature selection [5]. Tree-based models like Random Forest and XGBoost also provide built-in feature importance measures based on how much a feature decreases impurity across all trees [2].

- Advantages: Embedded methods offer a compelling balance between efficiency and performance. They are more computationally efficient than wrapper methods because they avoid the iterative retraining loop, yet they are more sophisticated than filter methods because the selection is model-guided [5]. They are, therefore, a popular choice for many practical applications.

- Disadvantages: While more efficient than wrappers, they can still be slower than simple filter methods. The feature selection is also tied to a specific model, meaning the selected subset may not be optimal for a different learning algorithm.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methodologies

| Criterion | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods (e.g., RFE) | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Ranks features by statistical scores | Uses model performance to guide search | Integrates selection into model training |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | Moderate |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low | High (if not cross-validated) | Moderate |

| Model Dependency | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ability to Capture Feature Interactions | Poor | Strong | Strong |

| Typical Use Case | Pre-processing for ultra-high-dimensional data | Performance-critical applications with sufficient resources | General-purpose, balanced applications |

Benchmark Performance and Experimental Data

Empirical evidence from various computational biology domains underscores the performance trade-offs between different feature selection approaches. The table below synthesizes quantitative findings from multiple studies, which serve as a proxy for expected outcomes in cheminformatics given the analogous data structures.

Table 2: Benchmark Results of Feature Selection Methods Across Domains

| Study & Domain | Filter Method Performance | Wrapper Method Performance | Embedded Method Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Video Traffic Classification [5] | Low computational overhead, moderate accuracy | Higher accuracy, but longer processing times | Balanced compromise between accuracy and speed | Embedded methods provided a good trade-off for this task. |

| Microarray Cancer Classification [3] | N/A | N/A | Hybrid Filter-GA approach achieved outstanding enhancements in Accuracy, Recall, Precision, and F-measure. | Combining filter and evolutionary algorithms (a wrapper) yielded superior results. |

| Metabarcoding Data Analysis [2] | Linear methods (Pearson/Spearman) were generally less effective than nonlinear. | RFE enhanced Random Forest performance. | Tree ensembles (RF, XGBoost) consistently outperformed other approaches, even without explicit FS. | Robust ensemble models often reduce the critical dependence on feature selection. |

| Educational & Healthcare Data [7] | N/A | RFE with tree models (RF, XGBoost) yielded strong predictive performance but with high computational cost. | A variant, Enhanced RFE, achieved substantial feature reduction with only marginal accuracy loss. | Different RFE variants offer trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of feature selection benchmarks, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The following methodology, commonly employed in rigorous comparisons [5] [2], can be adapted for cheminformatics datasets.

Dataset Preparation and Partitioning:

- Select a curated cheminformatics dataset with a known endpoint (e.g., IC50, solubility, toxicity). The dataset should exhibit high dimensionality (e.g., hundreds or thousands of molecular descriptors).

- Split the dataset into three subsets: Training Set (e.g., 60%), Validation Set (e.g., 20%), and Hold-out Test Set (e.g., 20%). The hold-out test set must be locked away and used only for the final evaluation of the selected model.

Application of Feature Selection Methods:

- Filter Methods: On the training set, apply univariate statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA F-test, mutual information) or correlation-based analyses. Select the top k features based on their scores. The value of k can be tuned on the validation set.

- Wrapper Methods (RFE): Implement RFE wrapped around a classifier (e.g., SVM, Random Forest). Using the training set, perform the recursive elimination process. The stopping criterion (number of final features) should be optimized based on performance on the validation set to prevent overfitting.

- Embedded Methods: Train models with built-in feature selection (e.g., Lasso regression, Random Forest) on the training set. For Lasso, the regularization strength parameter C should be tuned via cross-validation on the training set. Extract the features with non-zero coefficients or high importance scores.

Model Training and Evaluation:

- For each feature selection method, train a final predictive model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) using only the selected features from the training set.

- Evaluate the performance of each model on the hold-out test set using relevant metrics, such as Accuracy, F1-score, Precision-Recall AUC, or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), depending on the task (classification or regression).

- Report the computational time required for the entire feature selection and model training process for each method.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Feature Selection

Implementing a robust feature selection workflow requires leveraging specific computational tools and algorithms. The following table details key "research reagent solutions" essential for experiments in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Algorithms for Feature Selection

| Tool/Algorithm | Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Gain / Chi-Squared | Filter | Ranks features by their statistical dependence on the target variable. | Fast, preliminary feature screening in high-dimensional data [3]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Wrapper | Iteratively removes the least important features based on model weights. | Identifying a compact, high-performance feature subset [6] [7]. |

| Lasso Regression | Embedded | Performs feature selection via L1 regularization, shrinking coefficients of irrelevant features to zero. | Building interpretable linear models with inherent feature selection [5]. |

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Embedded | Provides built-in feature importance measures (e.g., mean decrease in impurity). | General-purpose modeling with robust, non-linear feature importance quantification [2]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Wrapper (Evolutionary) | Uses a population-based search to evolve optimal feature subsets. | Complex optimization problems where the interaction between features is critical [3] [4]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Model for Wrapper | Often used as the core model within RFE (SVM-RFE) for feature ranking. | Particularly effective in bioinformatics and cheminformatics tasks with complex decision boundaries [6]. |

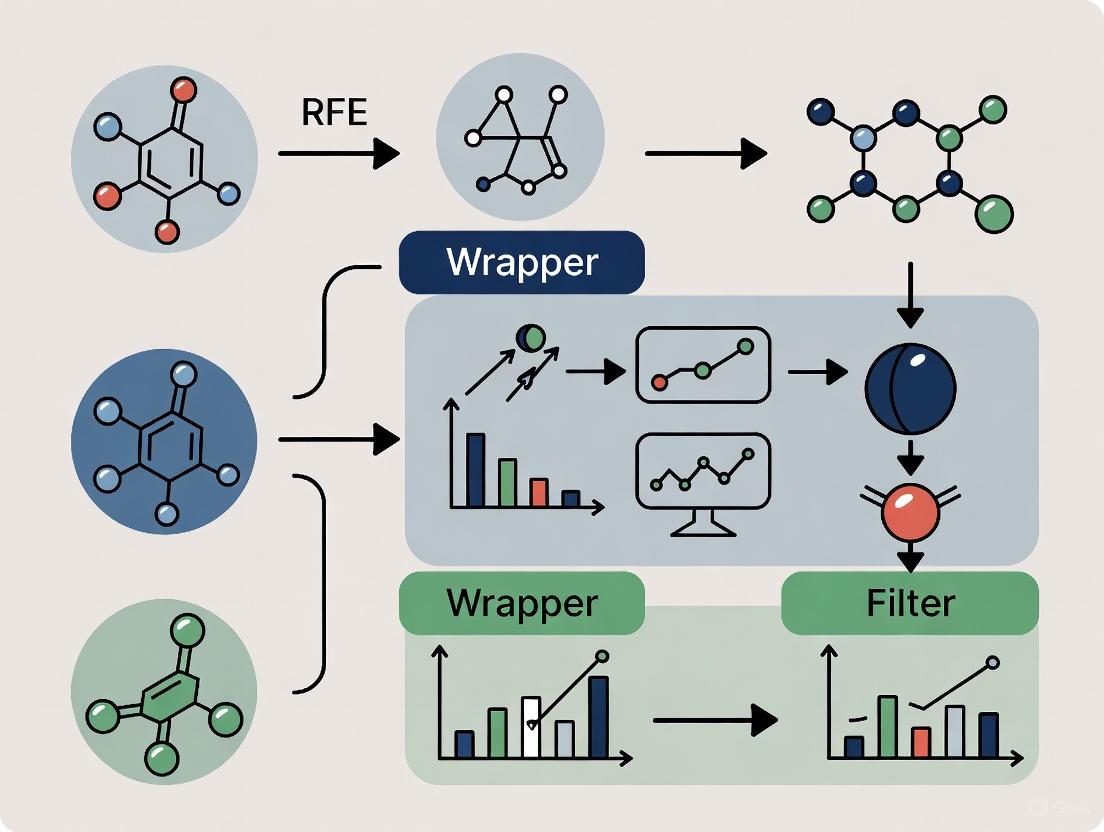

Workflow Visualization: A Roadmap for Feature Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for comparing the three feature selection methodologies, helping researchers visualize the critical decision points and processes involved in a benchmarking study.

The critical role of feature selection in cheminformatics is indisputable. As the field continues to generate increasingly complex and high-dimensional data from sources like molecular dynamics simulations and ultra-high-throughput virtual screening, the strategic implementation of feature selection will become even more central to extracting meaningful biological insights.

Evidence from comparative studies consistently shows that there is no single "best" method for all scenarios. The choice hinges on a trade-off between predictive performance, computational efficiency, and interpretability [5] [2] [7]. Filter methods offer a swift starting point for massive datasets, wrapper methods like RFE can squeeze out maximum performance at a higher computational cost, and embedded methods provide a practical and effective middle ground.

Future advancements are likely to focus on hybrid and adaptive approaches. For instance, using a fast filter method for initial dimensionality reduction before applying a more sophisticated wrapper or embedded method can optimize the efficiency-performance balance [3]. Furthermore, research into dynamic formulations, such as evolutionary algorithms with adaptive chromosome lengths, holds promise for automatically determining the optimal number of features alongside the feature set itself [4]. By thoughtfully applying and continuously refining these techniques, cheminformatics researchers can build more reliable, interpretable, and powerful models, thereby accelerating the pace of drug discovery and development.

In the field of cheminformatics, the ability to identify the most relevant molecular features from high-dimensional data is paramount for successful drug discovery. Machine learning models built for tasks such as activity prediction, toxicity assessment, and virtual screening rely heavily on robust feature selection to improve predictive accuracy, enhance model interpretability, and reduce computational costs [8] [9]. The three dominant feature selection paradigms—filter, wrapper, and embedded methods—each offer distinct mechanisms for this purpose, with recursive feature elimination (RFE) occupying a unique and often debated position within this taxonomy [10] [11] [7].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these three methodologies, focusing on their application in cheminformatics. We present synthesized experimental data, detailed protocols from recent studies, and practical resources to help researchers and drug development professionals select the optimal feature selection strategy for their specific projects.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Defining the Three Paradigms

Filter Methods: These methods select features based on intrinsic data properties and statistical measures, independently of any machine learning algorithm. They operate by ranking features according to criteria such as correlation with the target variable or mutual information. While computationally efficient and fast to implement, a key limitation is that they ignore interactions with a classifier and may not select features optimal for the final predictive model [11] [12]. Common examples include correlation-based scores and mutual information.

Wrapper Methods: These methods evaluate feature subsets by using a specific machine learning algorithm's performance as the objective function. They "wrap" themselves around a predictive model and search for feature subsets that yield the best performance, thereby considering feature interactions and dependencies. Their main drawback is high computational cost, as they require building and evaluating numerous models [13] [11] [12]. Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) and Sequential Backward Selection (SBS) are classic examples.

Embedded Methods: These techniques integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training step. The model itself performs feature selection as part of its learning process, offering a balance between the computational efficiency of filters and the performance-oriented approach of wrappers. They are computationally efficient and can capture feature relevancy. Methods like LASSO (L1 regularization) and tree-based algorithms like Random Forest, which provide built-in feature importance metrics, are prime examples [11] [12].

The Case of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

RFE is a powerful yet often misclassified feature selection algorithm. Its hybrid nature sparks debate, as it exhibits characteristics of multiple paradigms [10] [7].

- Mechanism: RFE operates through a recursive, backward elimination process. It starts with all features, trains a model (e.g., SVM or Random Forest), ranks features by their importance (e.g., model coefficients or Gini importance), prunes the least important ones, and repeats the process with the remaining features until a stopping criterion is met [11] [7].

- Classification Debate: RFE's classification is not straightforward. It is often categorized as a wrapper method because it involves iterative model training to evaluate feature subsets [10]. However, some experts argue it is an embedded method because it uses an internal model's feature weights for ranking, and the feature selection is intertwined with the model's own learning process, unlike a typical wrapper that uses prediction accuracy to guide the search [10] [11]. It is generally not considered a pure filter method, as it relies on a model rather than a simple statistical test [10].

Table 1: Theoretical Comparison of Filter, Wrapper, Embedded Methods, and RFE.

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods | RFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Statistical measures with target variable | Performance of a specific ML model | Built-in model mechanism | Recursive elimination based on model's feature importance |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | Medium | Medium to High |

| Handles Feature Interactions | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low | High | Medium | Medium |

| Model Dependency | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Primary Cheminformatics Use Cases | Initial data filtering, high-dimensionality reduction [9] | Optimizing predictive model performance [13] [12] | Efficient model building with built-in selection [9] [12] | Identifying small, interpretable feature sets in bioinformatics & EDM [7] |

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarking

Benchmarking RFE Variants in Predictive Modeling

A 2025 benchmarking study evaluated various RFE variants across educational and clinical datasets, providing key insights into their performance trade-offs [7].

Table 2: Performance of RFE Variants in a Benchmarking Study [7].

| RFE Variant | Predictive Accuracy | Feature Set Size | Computational Cost | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE with Random Forest | Strong | Large | High | Medium |

| RFE with XGBoost | Strong | Large | High | Medium |

| Enhanced RFE | Good (marginal loss) | Substantially reduced | Lower | High |

Key Findings: The study concluded that RFE wrapped with complex tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost) delivered strong predictive performance but at the cost of retaining larger feature sets and higher computational demands. In contrast, the Enhanced RFE variant achieved a favorable balance, offering substantial feature reduction with only a marginal loss in accuracy, making it suitable for applications where interpretability and efficiency are prioritized [7].

Filter vs. Wrapper vs. Embedded in Cheminformatics

A study on developing classifiers for antiproliferative activity against prostate cancer cell lines (PC3, LNCaP, DU-145) implemented a pipeline using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for feature selection with tree-based algorithms (Extra Trees, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machines, XGBoost) and molecular descriptors (RDKit, ECFP4) [9]. The best-performing models, which used GBM and XGB algorithms, achieved Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) values above 0.58 and F1-scores above 0.8, demonstrating the effectiveness of this embedded/wrapper hybrid approach in a real-world cheminformatics task [9].

Another study proposed a novel Artificial Intelligence based Wrapper (AIWrap) to address the computational intensity of traditional wrappers. In evaluations on both simulated and real biological data, AIWrap showed better or at-par feature selection and model prediction performance compared to standard penalized feature selection algorithms (like LASSO and Elastic Net) and traditional wrapper algorithms [12].

Table 3: Classifier Performance with Feature Selection on Prostate Cancer Cell Line Data [9].

| Cell Line | Algorithm | Molecular Features | MCC | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC3 | Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) | RDKit & ECFP4 | > 0.58 | > 0.8 |

| DU-145 | XGBoost (XGB) | RDKit & ECFP4 | > 0.58 | > 0.8 |

| LNCaP | Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) | RDKit & ECFP4 | > 0.58 | > 0.8 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementation, we outline the methodologies from two key studies.

Protocol 1: Classifier Development with RFE for Antiproliferative Activity Prediction

This protocol is adapted from a study aiming to build robust classifiers for predicting compound activity against prostate cancer cell lines [9].

- Data Curation and Preparation: Collect compounds with experimentally validated antiproliferative activity from databases like ChEMBL. Preprocess the data by removing duplicates and standardizing structures.

- Molecular Feature Generation: Compute multiple sets of molecular features for each compound:

- RDKit Descriptors: A broad range of physicochemical and topological properties.

- ECFP4 Fingerprints: Circular fingerprints encoding atom-centered substructures.

- MACCS Keys: 166 predefined binary structural keys.

- Custom Fragments: Generate data set-specific molecular fragments through statistical analysis and filtering.

- Feature Selection via RFE: Implement Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to retain the most informative descriptors from the generated feature sets. This step reduces dimensionality and mitigates overfitting.

- Model Training and Validation: Split the data into stratified training and test sets. Train multiple tree-based classifiers (ET, RF, GBM, XGB) on the selected features. Optimize hyperparameters using cross-validation.

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the best-performing models on the held-out test set using metrics such as MCC, F1-score, and accuracy.

- Explainability Analysis: Employ SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to interpret model predictions and identify features driving the classification decisions.

Protocol 2: The AIWrap Framework for High-Dimensional Data

This protocol details the AIWrap algorithm, a novel wrapper method designed to reduce computational burden [12].

- Initial Model Sampling: Instead of building models for every possible feature subset, the algorithm begins by building and evaluating models for only a fraction of all possible feature subsets.

- Performance Prediction Model (PPM) Training: An AI model (the PPM) is trained to learn the hidden relationship between the composition of a feature subset and the performance of its corresponding predictive model. This PPM is trained on the results from the initial sampling step.

- Feature Subset Evaluation: For new, unevaluated feature subsets proposed by a search algorithm (e.g., genetic algorithm), the PPM is used to predict their model's performance instead of building and evaluating the actual model.

- Iteration and Final Model Selection: The process of proposing feature subsets and predicting their performance continues until a stopping criterion is met. The best feature subset identified through this process is then used to train the final predictive model.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical relationship and process differences between the standard wrapper method and the AIWrap method.

Successfully implementing feature selection methods in cheminformatics requires a suite of computational tools and molecular data resources.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Feature Selection in Cheminformatics.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Feature Selection | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [8] [9] | Cheminformatics Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints for compound representation. | Generating physicochemical features (e.g., molecular weight, logP) and ECFP4 fingerprints for filter or wrapper methods. |

| scikit-learn [11] | Machine Learning Library | Provides implementations of RFE, various ML models (SVM, Random Forest), and feature selection tools. | Implementing the RFE algorithm with an SVM classifier for recursive feature elimination. |

| SHAP [9] | Explainable AI (XAI) Library | Explains model predictions and quantifies feature importance post-selection. | Interpreting a trained model to understand which molecular features most influenced activity predictions. |

| PMLB [14] | Public Dataset Repository | Provides curated benchmark datasets for testing and comparing feature selection algorithms. | Benchmarking the performance of a new wrapper method against established algorithms on standardized data. |

| Enamine / OTAVA Libraries [15] | Virtual Chemical Libraries | Ultra-large libraries of "make-on-demand" compounds for virtual screening. | Serving as a source of molecules for large-scale virtual screening after feature selection has identified key molecular properties. |

In the field of cheminformatics, where the efficient analysis of vast chemical libraries is paramount for accelerating drug discovery, feature selection methods are indispensable tools. These methods are broadly categorized into filter, wrapper, and embedded techniques, each with distinct strengths and trade-offs. As the volume and dimensionality of chemical and biological data continue to grow, selecting the right feature selection strategy becomes critical for building predictive and interpretable models. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methods, with a focused examination of filter methods, highlighting their inherent advantages in speed and simplicity for research applications.

Methodologies at a Glance: Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded

Understanding the core mechanisms of each feature selection category is the first step in selecting an appropriate method.

- Filter Methods evaluate the relevance of features based on their intrinsic statistical properties, such as their correlation with the target variable, without involving any machine learning algorithm. They are model-agnostic, fast to compute, and provide a general-purpose, preliminary ranking of features. Common techniques include Correlation Coefficient, Chi-Squared Test, and Mutual Information [16].

- Wrapper Methods use the performance of a specific predictive model to evaluate feature subsets. Techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Forward/Backward Selection iteratively train models on different feature combinations to find the optimal subset [17] [16]. While they often yield high-performing feature sets by accounting for feature interactions, this comes at a high computational cost [18].

- Embedded Methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. Examples include the variable importance measures from Random Forest and regularization methods like LASSO [18] [19]. They offer a balance, providing model-specific selection with computational efficiency greater than wrapper methods [19].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental operational differences between these three approaches.

Comparative Performance and Experimental Data

The theoretical differences between these methods translate into tangible variations in performance, accuracy, and computational demand. The following tables summarize experimental findings from multiple studies, providing a data-driven basis for comparison.

Table 1: Classification Performance Across Domains

| Domain | Feature Selection Method | Classifier | Accuracy | Number of Features Selected | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speech Emotion Recognition [17] | Mutual Information (Filter) | - | 64.71% | 120 | Outperformed use of all 170 features (61.42% accuracy) |

| Correlation-Based (Filter) | - | ~63% | Varies with threshold | Balanced simplicity and accuracy effectively | |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (Wrapper) | - | Improved | ~120 | Performance stabilized with sufficient features | |

| Industrial Fault Classification [19] | Random Forest Importance (Embedded) | SVM / LSTM | >98.4% (F1-score) | 10 | Embedded methods achieved high performance with minimal features |

| Mutual Information (Filter) | SVM / LSTM | >98.4% (F1-score) | 10 | Also performed excellently on this task | |

| Microarray Gene Expression [20] | SVM-RFE (Wrapper) | SVM | Varies by dataset | Gene lists | Emphasized that choice of feature selection substantially influences classification success |

Table 2: Computational and Practical Characteristics

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | Very Fast [16] | Slow [18] [16] | Moderate to Fast [19] |

| Model Dependency | None (Model-Agnostic) | High (Model-Specific) | Integrated (Model-Specific) |

| Handling Feature Interactions | Poor (Evaluates individually) [16] | Excellent (Considers combinations) [16] | Good (Model-dependent) |

| Risk of Overfitting | Lower | Higher [16] | Moderate |

| Primary Advantage | Speed and Simplicity for initial filtering [8] [16] | Potential for higher accuracy via feature interaction [16] | Balance of performance and efficiency [19] |

| Ideal Use Case | Pre-processing and large-scale initial filtering [8] | Final model tuning with smaller feature sets | General-purpose model-driven analysis |

Modern cheminformatics relies on a suite of software tools and databases to manage and analyze chemical data. The following table lists key resources relevant to feature selection and drug discovery workflows.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools

| Tool / Database Name | Type | Primary Function in Cheminformatics |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [8] [21] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and handles molecular representation (e.g., SMILES, graphs). |

| PubChem [8] | Chemical Database | Public repository of chemical structures and their biological activities, used for data sourcing. |

| ZINC15 [8] | Virtual Chemical Library | Database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. |

| DrugBank [8] | Bioinformatic & Cheminformatic Database | Contains comprehensive drug and drug target data. |

| ADMETlab / admetSAR [21] | Web Tool / Platform | Predicts Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties. |

| AutoDock Vina [21] | Molecular Docking Tool | Performs structure-based prediction of ligand-protein binding affinity. |

| druglikeFilter [21] | Deep Learning Framework | Enables automated, multidimensional filtering of compound libraries based on drug-likeness. |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

To illustrate how these methods are implemented in real-world research, here are detailed methodologies from cited studies.

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Feature Selection for Enhanced Classification

This study [18] combined the strengths of embedded and wrapper methods to overcome the limitations of single-method approaches.

- Stage 1 (Embedded Pre-filtering): The Random Forest algorithm is trained on the entire dataset. Features are ranked based on their Variable Importance Measure (VIM) score, which is calculated from the total decrease in node impurities (Gini index) across all decision trees. A threshold is applied to eliminate features with low importance, reducing the dimensionality for the next stage.

- Stage 2 (Wrapper Optimization with Improved Genetic Algorithm): An Improved Genetic Algorithm (GA) is used to search for the global optimal feature subset from the pre-filtered features. The GA uses a multi-objective fitness function that minimizes the number of features while maximizing classification accuracy. Adaptive mechanisms and evolution strategies are incorporated to maintain population diversity and prevent premature convergence.

Protocol 2: Comparative Study of Filter and Wrapper Methods for Speech Emotion Recognition

This research [17] provides a clear protocol for benchmarking feature selection methods.

- Feature Extraction: Acoustic features (e.g., MFCC, RMS, ZCR) are extracted from speech signals across three public datasets (TESS, CREMA-D, RAVDESS), resulting in initial feature sets of 157-170 dimensions.

- Method Application:

- Filter Methods: Correlation-based (CB) and Mutual Information (MI) scores are calculated for each feature relative to the emotion label. Features are ranked, and top-k features are selected based on different score thresholds.

- Wrapper Method: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is used, which iteratively constructs a model (e.g., SVM), ranks features by importance, and removes the least important ones until the desired number of features is reached.

- Evaluation: The performance of the selected feature subsets is evaluated using classifiers, with metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Workflow for Cheminformatics Data Filtering

In cheminformatics, filter methods often serve as the first line of defense in processing large chemical libraries. The following diagram outlines a typical workflow for filtering a virtual chemical library to identify promising lead compounds, integrating concepts like the druglikeFilter [21] tool.

Filter, wrapper, and embedded feature selection methods each occupy a critical niche in the cheminformatics pipeline. Filter methods, with their exceptional speed and simplicity, are ideal for the initial stages of drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently pre-process massive virtual libraries and reduce dimensionality before applying more computationally intensive techniques [8] [16]. Wrapper methods can potentially unlock higher accuracy by leveraging feature interactions, making them suitable for fine-tuning models on smaller, curated datasets. Embedded methods offer a powerful and efficient compromise, often delivering robust performance for general-purpose modeling [19].

The choice among them is not a matter of identifying a single "best" method, but rather of strategically sequencing them. A common and effective strategy in modern cheminformatics involves using fast filter methods for initial screening, followed by more refined wrapper or embedded methods for lead optimization, thereby creating an efficient and powerful workflow for accelerating drug development.

In the field of cheminformatics and drug development, the ability to extract meaningful signals from high-dimensional data is paramount. Feature selection serves as a critical preprocessing step, directly influencing the performance, interpretability, and computational efficiency of machine learning models. Among the various strategies, wrapper methods represent a powerful approach that searches for optimal feature subsets by leveraging the learning algorithm itself as a guide. This article provides a comparative analysis of wrapper methods, focusing on their performance and precision against filter and embedded techniques, with a specific emphasis on applications in cheminformatics research. We examine empirical evidence from recent benchmark studies to offer actionable insights for researchers and scientists navigating the complex landscape of feature selection.

Understanding Feature Selection Paradigms

Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three distinct paradigms, each with its own operational philosophy and trade-offs. A clear understanding of these categories is essential for contextualizing the role of wrapper methods.

Filter Methods: These methods select features based on statistical measures of their intrinsic properties, such as correlation with the target variable, without involving any machine learning algorithm. They are computationally efficient, model-agnostic, and serve as an excellent first pass for feature reduction. Common techniques include correlation-based filters and mutual information. Their primary limitation is that they may overlook feature interactions that are meaningful to a specific classifier [22].

Wrapper Methods: Wrapper methods employ a specific machine learning model to evaluate the usefulness of feature subsets. They work by iteratively selecting a subset of features, training a model on them, and evaluating its performance using a predefined metric. This process continues until an optimal subset is found. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a prominent example, which recursively removes the least important features based on model weights or importance scores [23]. While these methods can yield high-performing feature sets tailored to a model, they are computationally intensive and carry a higher risk of overfitting [22].

Embedded Methods: These techniques integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. Models like Lasso (L1 regularization) and tree-based algorithms like Random Forest perform feature selection as part of their inherent learning process. Embedded methods offer a balanced compromise, providing model-specific selection without the prohibitive computational cost of wrappers [23] [22].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of these paradigms.

Table 1: Core Feature Selection Paradigms: A Comparative Overview

| Method Type | Operating Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Selects features based on statistical scores (e.g., correlation, mutual information). | Fast, computationally efficient, model-independent. | Ignores feature interactions with the model; may select redundant features. | Correlation-based, Mutual Information (MI), Fisher Score [17] [19] [22] |

| Wrapper Methods | Uses a model's performance as the objective to evaluate feature subsets. | Model-specific, can capture feature interactions, often high accuracy. | Computationally expensive, high risk of overfitting. | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Sequential Feature Selection (SFS) [17] [23] [19] |

| Embedded Methods | Performs feature selection during the model training process. | Balanced efficiency and performance, model-specific, less prone to overfitting than wrappers. | Limited to specific models; can be less interpretable than filters. | Lasso Regression, Random Forest Importance (RFI) [23] [19] [22] |

Performance Benchmarking in Diverse Domains

The theoretical strengths and weaknesses of wrapper methods are best understood through empirical evidence. Benchmark studies across various scientific domains, from ecology to industrial diagnostics, provide critical insights into their real-world performance.

Cheminformatics and Multi-Omics Data

In a large-scale benchmark analysis focusing on multi-omics data for cancer classification, wrapper methods were evaluated alongside other techniques. The study, which utilized 15 cancer datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), found that wrapper methods like RFE could deliver strong predictive performance, particularly when used with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. However, the study also highlighted a significant drawback: wrapper methods were "computationally much more expensive than the filter and embedded methods." Furthermore, the genetic algorithm (GA), another wrapper method, performed the worst among the subset evaluation methods for both Random Forest and SVM classifiers [24].

Another benchmark on environmental metabarcoding datasets suggested that feature selection, including wrapper methods, is more likely to impair model performance than to improve it for robust tree ensemble models like Random Forests. This indicates that the necessity of wrapper methods may depend on the underlying classifier, with simpler models potentially benefiting more from aggressive feature subset selection [25].

Industrial Diagnostics and General Machine Learning

A study on industrial fault classification using time-domain features compared five feature selection methods. The embedded method, Random Forest Importance (RFI), demonstrated superior effectiveness, while the wrapper method Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) also showed strong performance. The study concluded that embedded methods were highly effective in improving classification performance while reducing computational complexity [19].

A practical experiment on a diabetes dataset compared filter, wrapper (RFE), and embedded (Lasso) methods. The results demonstrated that the embedded method (Lasso) offered the best balance of accuracy and efficiency. While RFE successfully cut the feature set in half (from 10 to 5 features), it resulted in a slight reduction in accuracy (R²: 0.4657) compared to using the filter method (R²: 0.4776) or Lasso (R²: 0.4818). This underscores a common trade-off with wrappers: they can create simpler models but sometimes at the cost of predictive power, especially with smaller datasets [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Domain / Study | Best Performing Method(s) | Wrapper Method Performance | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech Emotion Recognition [17] | Mutual Information (Filter) | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) performance improved with more features, stabilizing at ~120 features. | Accuracy: MI (64.71%), All Features baseline (61.42%) |

| Multi-Omics Cancer Classification [24] | mRMR (Filter), RF-VI (Embedded), Lasso (Embedded) | RFE performed well with SVM, but wrapper methods were computationally most expensive. | Area Under the Curve (AUC) |

| Diabetes Dataset [23] | Lasso (Embedded) | RFE reduced features to 5, but yielded lower R² (0.4657) than Lasso (0.4818). | R² Score |

| Industrial Fault Diagnosis [19] | Random Forest Importance (Embedded) | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) was a strong contender among tested methods. | F1-Score (>98.40%) |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure the reproducibility of feature selection benchmarks, it is crucial to understand the standard experimental protocols. The following workflow diagram and detailed breakdown outline the typical process for evaluating wrapper methods like RFE in a cheminformatics context.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Feature Selection Benchmarking

Detailed Methodology for Wrapper Method Evaluation

The workflow for benchmarking feature selection methods, particularly wrapper techniques, involves several critical stages. The following protocol synthesizes methodologies from the cited research, providing a reproducible framework for cheminformatics applications [23] [24] [26].

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Data Collection: Obtain a relevant dataset, such as a chemical compound library with associated molecular descriptors (e.g., from the ZINC15 database or TCGA) and a target property (e.g., bioactivity, toxicity) [27] [24] [26].

- Data Cleansing: Handle missing values and remove duplicates. The quality of data is paramount, as it directly impacts model performance [26].

- Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into training, calibration (if needed), and hold-out test sets. A common practice is to use a single split or k-fold cross-validation to ensure robust performance estimation [23] [24].

Feature Selection Implementation:

- Wrapper Method (RFE): The core of the evaluation involves implementing the RFE algorithm.

- Model Choice: Select a base estimator (e.g., Linear Regression, Support Vector Machine). The choice of model influences which features are deemed important [23].

- Iterative Elimination: The RFE process starts with all features, fits the model, and obtains a feature importance ranking. The least important feature(s) are pruned, and the process repeats until the desired number of features is reached [23].

- Comparison Methods: Implement filter (e.g., Mutual Information, Correlation-based) and embedded (e.g., Lasso, Random Forest Importance) methods in parallel for a fair comparison [17] [23] [19].

- Wrapper Method (RFE): The core of the evaluation involves implementing the RFE algorithm.

Model Training and Validation:

- Train Classifiers/Regressors: Using the feature subsets selected by each method, train machine learning models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) on the training set.

- Cross-Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) on the training set to tune hyperparameters and avoid overfitting. This step is computationally intensive for wrapper methods [23] [24].

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using relevant metrics such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score for classification, or R² and Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression [17] [23].

For researchers aiming to implement feature selection methods in cheminformatics, the following tools and resources are essential. This table catalogs key computational "reagents" and their functions in conducting a robust feature selection analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cheminformatics Feature Selection

| Research Reagent / Resource | Type / Category | Function in Research | Example Applications / Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors & Fingerprints | Data Representation | Numerical representations of chemical structures that serve as input features for ML models. | Morgan fingerprints (ECFP4), continuous data-driven descriptors (CDDD) [27] [26] |

| Public ADMET & Compound Databases | Data Source | Provide high-quality, curated datasets for training and validating predictive models. | Enamine REAL space, ZINC15, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [27] [24] [26] |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Wrapper Method Algorithm | Iteratively removes the least important features based on model weights to find an optimal subset. | Implemented via scikit-learn; used with Linear Regression, SVM [23] [19] |

| CatBoost / Random Forest Classifier | Machine Learning Algorithm | Serves as the base model for evaluating feature subsets in wrappers or for intrinsic feature importance. | CatBoost used for virtual screening; RF for multi-omics classification [27] [24] |

| Lasso Regression (L1) | Embedded Method Algorithm | Integrates feature selection by penalizing coefficients, shrinking less important ones to zero. | Compared directly against RFE and filter methods [23] [24] |

| Cross-Validation Framework (e.g., 5-fold) | Validation Protocol | Ensures robust performance estimation and mitigates overfitting during model training and feature selection. | Used in nearly all benchmark studies to validate results [23] [24] |

The journey through the performance and precision of wrapper methods reveals a landscape defined by trade-offs. Wrapper methods, particularly Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), stand out for their ability to identify high-performing, model-specific feature subsets by directly optimizing for predictive accuracy. This can lead to highly tuned models, as seen in their strong performance with SVM classifiers in multi-omics data.

However, this precision comes at a significant cost. Benchmark studies consistently highlight their computational intensity and time consumption, making them less suitable for the initial screening of ultra-large chemical libraries or when computational resources are limited. Furthermore, they carry a inherent risk of overfitting, especially with small datasets.

For researchers in cheminformatics and drug development, the choice of a feature selection method is not one-size-fits-all. For rapid filtering of billion-molecule libraries, fast filter or embedded methods are more practical. When model interpretability and robust performance are the goals, especially with complex classifiers like Random Forests, embedded methods often provide an optimal balance. Wrapper methods find their niche in scenarios where computational resources are adequate, and the goal is to squeeze out maximum predictive performance from a specific model, making them a precision tool for the well-equipped scientist's toolkit.

In the field of cheminformatics, the "curse of dimensionality" presents a significant challenge for building robust predictive models for tasks like molecular property prediction and virtual screening. With the ability to generate thousands of molecular descriptors from chemical structures, identifying the most informative features becomes paramount. Feature selection methods are conventionally categorized into three distinct paradigms: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods [28] [22] [29].

Filter methods assess feature relevance based on intrinsic data properties using statistical measures like correlation coefficients or chi-square tests, offering computational efficiency but independently of the model [28] [5]. Wrapper methods, such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), evaluate feature subsets by iteratively training a model and assessing its performance, leading to model-specific optimization at a higher computational cost [7] [29]. Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process, as seen in LASSO regularization or tree-based algorithms, providing a balanced approach [28] [30].

This guide focuses on a nuanced hybrid approach that combines the strengths of Embedded methods and RFE. We will objectively compare their performance against other alternatives, providing supporting experimental data and detailed methodologies to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing optimal feature selection strategies for their cheminformatics projects.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Embedded Methods: Selection through Model Training

Embedded methods perform feature selection as an inherent part of the model training process, combining the efficiency of filter methods with the model-specific relevance of wrapper methods [22]. Key embedded techniques include:

- Regularization-based methods: Algorithms like LASSO (L1 regularization) introduce a penalty term to the model's cost function, which forces the coefficient weights of less important features toward zero, effectively performing feature selection [28] [29]. The regularized cost function is expressed as:

regularized_cost = cost + λ|w|₁, whereλcontrols the penalty strength andwis the feature weight vector [28]. - Tree-based methods: Ensemble algorithms like Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) provide built-in feature importance measurements based on metrics like Gini impurity or mean decrease in accuracy, allowing for implicit feature selection during training [7] [30].

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): A Greedy Wrapper Approach

RFE is a wrapper method that operates through a recursive, backward elimination process [7]. Its algorithm can be broken down into four key steps, as illustrated in Figure 1:

- Train Model: A machine learning model is trained using the entire set of features.

- Rank Features: The importance of each feature is computed and ranked based on model-specific criteria (e.g., coefficient magnitude for linear models, Gini importance for tree-based models).

- Prune Features: The least important feature(s) are removed from the current feature set.

- Repeat/Stop: Steps 1-3 are repeated iteratively until a predefined stopping criterion (e.g., a target number of features) is met [7].

The Hybrid Paradigm: Embedding RFE

The hybrid approach leverages embedded methods to enhance the RFE process. Instead of using a simple model or a single metric, RFE is "wrapped" around a powerful embedded algorithm [7]. For instance, using Random Forest or XGBoost within RFE allows the wrapper method to utilize the sophisticated, non-linear feature importance metrics generated by these embedded algorithms to guide the recursive elimination process more effectively [7]. This synergy can lead to more stable and predictive feature subsets.

Figure 1: Workflow of the Hybrid Embedded-RFE Approach. This diagram illustrates the recursive process of combining an embedded model's feature importance with the RFE wrapper method.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

To objectively evaluate the hybrid Embedded-RFE approach against other feature selection methods, we summarize performance metrics from multiple studies across various domains, including cheminformatics-relevant applications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods

| Method Category | Example Algorithms | Average Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Model Interpretability | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Pearson Correlation, Chi-Square [22] [29] | Moderate (e.g., ~70-80% F1 in traffic classification) [5] | High (Fast, model-agnostic) [22] [5] | High (Simple, statistical basis) [22] | Low to Moderate [5] |

| Wrapper Methods | RFE with Linear Models [7] | High (e.g., ~85.3% accuracy in medical data) [31] | Low (Computationally expensive) [7] [29] | Moderate (Model-specific subset) [7] | Moderate [7] |

| Embedded Methods | LASSO, Random Forest [28] [30] | High (e.g., ~92.4% accuracy with XGBoost) [5] | Medium (Efficient, built-in) [22] [5] | Medium (Tied to model internals) [22] | High [5] |

| Hybrid (Embedded-RFE) | RFE with Random Forest/XGBoost [7] [31] | Very High (e.g., 85.3% avg. accuracy, 81.5% precision [31]) | Low to Medium (Varies with base model) [7] | High (Leverages embedded importance) [7] | High (Enhanced by embedded metrics) [7] |

The data reveals distinct trade-offs. A benchmark study showed that RFE wrapped with tree-based models like Random Forest and XGBoost yields strong predictive performance, though it often retains larger feature sets and has higher computational costs [7]. In medical data analysis, a hybrid framework combining a synergistic feature selector with a distributed multi-kernel classifier achieved an average accuracy of 85.3%, a precision of 81.5%, and a recall of 84.7%, outperforming other methods [31]. Conversely, a variant dubbed "Enhanced RFE" was shown to achieve substantial feature reduction with only marginal accuracy loss, offering a favorable balance [7].

Table 2: Detailed Benchmarking of RFE Variants on Specific Tasks

| RFE Variant | Domain & Task | Key Performance Metrics | Feature Reduction & Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFE with Tree Models (e.g., RF, XGBoost) [7] | Educational & Clinical Data | Strong predictive accuracy | Retains larger feature sets; High computational cost |

| Enhanced RFE [7] | Educational & Clinical Data | Marginal loss in accuracy | Substantial feature reduction; Favorable efficiency-performance balance |

| SKR-DMKCF (Hybrid) [31] | Medical Data Analysis | 85.3% Accuracy, 81.5% Precision | 89% avg. feature reduction; 25% reduced memory usage |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

For researchers seeking to implement and validate these methods, this section outlines standard experimental protocols derived from the cited literature.

Protocol for Embedded-RFE Hybrid Workflow

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully applied RFE with embedded models [7] [31].

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Data Sourcing: Collect a dataset relevant to the cheminformatics problem (e.g., molecular structures and a target property from PubChem [32]).

- Feature Engineering: Generate a pool of candidate features/descriptors. For inorganic materials, use packages like

MendeleevorMatminer; for organic molecules, useRDKitorPaDELto compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints [30]. - Data Cleaning: Handle missing values, remove duplicates, and address outliers. Standardize or normalize the data if necessary [30].

- Train-Test Split: Partition the dataset into training and test sets using an appropriate strategy (e.g., random split, scaffold split for molecules) to ensure a robust evaluation [30].

Model and RFE Configuration:

- Base Model Selection: Choose an embedded algorithm with a robust feature importance metric, such as Random Forest, XGBoost, or SVM with a linear kernel [7].

- RFE Setup: Initialize the RFE class from a library like

scikit-learn. Define the stopping criterion, which can be a fixed number of features, or a threshold of performance to achieve [7]. - Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation on the training set during the RFE process to prevent overfitting and ensure a reliable estimate of model performance for each feature subset [29].

Execution and Evaluation:

- Iterative Elimination: Run the RFE algorithm, which will recursively train the model, rank features, and eliminate the least important ones.

- Optimal Subset Identification: Select the feature subset that delivers the best cross-validated performance.

- Final Model Training: Train a final model on the entire training set using only the selected optimal features.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using domain-appropriate metrics (e.g., ROC-AUC, RMSE, Precision, Recall, F1-score) [32] [31].

Protocol for Comparative Studies

To benchmark the hybrid approach against other methods, as done in electronics and medical research [5] [31], follow this structure:

- Baseline Establishment: Train and evaluate a model using all available features without any selection.

- Multiple Method Application: Apply several feature selection techniques to the same training data:

- A filter method (e.g., Pearson Correlation or variance threshold) [5].

- A wrapper method (e.g., vanilla RFE with a simple model).

- An embedded method (e.g., LASSO or tree-based feature importance as a standalone selector).

- The Hybrid Embedded-RFE method.

- Consistent Evaluation: For each resulting feature subset, train a model of the same type and hyperparameters. Evaluate all models on the same test set, comparing accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and computational time [5].

- Stability Analysis: To assess the stability of the feature selection methods, repeat the process on multiple bootstrapped samples of the dataset and measure the consistency of the selected features across runs [7].

Essential Research Toolkit

The following table details key software and libraries that are essential for implementing the feature selection methods discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Feature Selection Implementation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Feature Selection | Relevance to Cheminformatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn [7] | Python Library | Provides implementations of RFE, various embedded models (LASSO, Random Forest), filter methods, and model evaluation tools. | The primary workhorse for building and evaluating ML pipelines, including feature selection. |

| RDKit [32] [30] | Cheminformatics Library | Generates molecular descriptors and fingerprints from molecular structures, creating the feature pool for selection. | Crucial for converting chemical structures into a numerical feature set for ML. |

| XGBoost / LightGBM [7] [33] | Python Library | Offers high-performance tree-based models with strong built-in (embedded) feature importance measures, ideal for use with RFE. | Often used as the base model in a hybrid RFE approach for its predictive power and feature ranking. |

| Matminer [30] | Python Library | Provides feature generation and data mining tools for materials science, including a wide array of compositional and structural descriptors. | Essential for building feature pools for inorganic materials. |

| SHAP [30] | Python Library | Explains the output of any ML model, providing post-hoc interpretability for complex models and validating the importance of selected features. | Helps validate that the selected features are chemically meaningful. |

The hybrid Embedded-RFE approach represents a powerful synergy in the feature selection landscape for cheminformatics. While pure filter methods offer speed and embedded methods provide efficiency, the combination of RFE's thorough search with the sophisticated feature ranking of embedded models like XGBoost often leads to superior predictive performance and robust feature subsets, as evidenced by benchmark studies [7] [31]. The primary trade-off is increased computational cost.

The choice of an optimal feature selection strategy is not one-size-fits-all and should be guided by the specific project goals. If interpretability and speed are paramount, filter methods are excellent. If the focus is on building a highly accurate model with minimal manual intervention, standalone embedded methods are a strong choice. However, for researchers aiming to maximize predictive performance and gain deep insights into the most relevant molecular descriptors for their target, the hybrid Embedded-RFE approach is a compelling and highly effective strategy.

How Feature Selection Enhances Model Interpretability and Performance

In the field of cheminformatics, where researchers regularly work with high-dimensional molecular descriptor data, feature selection has become an indispensable step in building robust and interpretable models for drug discovery. The process of selecting the most relevant features from thousands of potential molecular descriptors directly addresses the curse of dimensionality that plagues quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and toxicity prediction [34] [35]. By strategically reducing the feature space, researchers can significantly enhance model performance while simultaneously improving the interpretability of the results—a crucial consideration for regulatory acceptance and scientific insight.

The challenge is particularly pronounced in cheminformatics due to the complex, often skewed distribution of active versus inactive compounds in drug discovery datasets [34]. Traditional modeling approaches frequently struggle with both high-dimensional feature spaces and imbalanced class distributions, creating a compelling need for sophisticated feature selection techniques tailored to these specific challenges. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of three dominant feature selection paradigms—filter, wrapper, and recursive feature elimination (RFE) methods—within the context of cheminformatics applications, examining how each approach balances performance optimization with interpretability enhancement.

Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three main types, each with distinct mechanisms and trade-offs between computational efficiency and performance optimization.

Filter Methods: Statistical Pre-screening

Filter methods operate independently of any machine learning algorithm, evaluating features based on statistical measures of relevance such as correlation with the target variable or mutual information [22] [23]. These methods are typically fast and computationally efficient, making them ideal for initial feature screening on large cheminformatics datasets. Common filter techniques include correlation-based feature selection, mutual information, chi-square tests, and ReliefF [17] [34]. The primary advantage of filter methods lies in their speed and model-agnostic nature, though they may overlook complex feature interactions important for predictive accuracy [35].

Wrapper Methods: Performance-Driven Selection

Wrapper methods approach feature selection as a search problem, where different feature subsets are evaluated based on their actual performance with a specific learning algorithm [22] [23]. These methods treat the model as a "black box" and use its performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) as the objective function to guide the search for optimal feature subsets. While wrapper methods can capture feature interactions and often yield superior performance, they are computationally intensive and carry a higher risk of overfitting, particularly with complex models or small datasets [35].

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Hybrid Approach

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) represents a hybrid approach that combines characteristics of both filter and wrapper methods [11] [10]. RFE works by recursively removing the least important features based on model-derived importance rankings (e.g., SVM weights or random forest feature importance) and rebuilding the model with the remaining features [11]. This iterative process continues until the desired number of features is reached. While RFE "wraps" around a specific model to obtain feature weights, it differs from pure wrapper methods in that it doesn't perform an exhaustive search of the feature subset space [10].

Methodological Workflows

The workflow differences between these three approaches can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Performance Analysis in Cheminformatics

Experimental Evidence from Toxicity Prediction

Recent research on toxicity prediction using Tox21 challenge datasets demonstrates the performance advantages of sophisticated feature selection methods. A 2025 study implementing a Binary Ant Colony Optimization (BACO) feature selection algorithm—a wrapper approach—showed significant improvements over traditional methods when predicting drug molecule toxicity [34]. The BACO method addresses both high-dimensional feature spaces and severely skewed distributions of active/inactive chemicals, two common challenges in cheminformatics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Tox21 Datasets

| Method | Type | F-Measure | G-Mean | MCC | AUC | Features Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACO (Wrapper) [34] | Wrapper | 0.6029 | 0.6866 | 0.6170 | 0.7657 | 20 |

| Initial Features [34] | None | 0.5519 | 0.6467 | 0.5727 | 0.7128 | 672 |

| Mutual Information [17] | Filter | 0.6500 | 0.6500 | 0.6500 | 0.6471 | 120 |

| All Features Baseline [17] | None | 0.6142 | 0.6142 | 0.6142 | 0.6142 | 170 |

The BACO wrapper method achieved these improvements by maximizing a weighted combination of three class imbalance performance metrics (F-measure, G-mean, and MCC) through multiple random divisions of the training data, followed by frequency analysis of features appearing in optimal subsets [34]. This approach specifically addresses the imbalanced data distribution problem common in toxicity prediction tasks.

Embedded Methods as Performance Compromise

Research comparing multiple feature selection approaches on standard datasets reveals that embedded methods like Lasso regression often provide an effective balance between performance and efficiency. In a comparative study feature selection techniques, Lasso (an embedded method) achieved the best R² score (0.4818) and lowest Mean Squared Error (2996.21) while retaining 9 of 10 features [23]. The wrapper method (RFE) with linear regression produced slightly lower performance (R²: 0.4657) but with greater feature reduction (5 features), while the filter method based on correlation thresholds demonstrated intermediate performance (R²: 0.4776) [23].

Table 2: Overall Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Method Type | Performance | Computational Cost | Feature Reduction | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High |

| Wrapper Methods | High | Very High | Variable | Moderate |

| RFE | High | Moderate | High | Moderate-High |

| Embedded Methods | High | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Enhancing Model Interpretability Through Feature Selection

The Interpretability Advantage in Cheminformatics

In cheminformatics, model interpretability is not merely a convenience—it's a scientific necessity. Regulatory applications require understanding which molecular features drive toxicity predictions, while drug design efforts benefit immensely from insights into structure-activity relationships [34]. Feature selection directly enhances interpretability by identifying the most relevant molecular descriptors, enabling researchers to focus on the key structural features influencing biological activity.

Filter methods particularly excel at producing interpretable results because their statistical foundations provide transparent criteria for feature importance [22]. However, recent advances in wrapper and hybrid methods have incorporated interpretability considerations directly into their optimization frameworks. For instance, the BACO wrapper method generates high-frequency feature lists that reveal the molecular descriptors most consistently associated with toxicity across multiple validation splits [34].

Stability and Interpretability

A crucial aspect of interpretability in cheminformatics is the stability of selected features—whether similar features are selected across different dataset variations. A 2023 study on feature selection with prior knowledge demonstrated that incorporating domain expertise into the selection process improves both the stability of selected features and the interpretability of chemometrics models [36]. This approach is particularly valuable in cheminformatics, where researchers often possess substantial prior knowledge about molecular descriptors likely to be relevant for specific biological endpoints.

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks

Bridging the Filter-Wrapper Divide

The latest research in feature selection has focused on hybrid frameworks that mediate between filter and wrapper methods to leverage their respective strengths while mitigating their weaknesses. A 2025 proposed a novel three-component framework incorporating an interface layer between filter and wrapper components [35]. This architecture uses Importance Probability Models (IPMs) that begin with filter-based feature rankings and iteratively refine them through wrapper-based evaluations, creating a dynamic collaboration that balances exploration and exploitation in the feature space.

This hybrid approach addresses a fundamental challenge in cheminformatics: filter methods efficiently evaluate individual features but may overlook important combinations, while wrapper methods account for feature interactions but are computationally intensive and prone to overfitting [35]. By employing multiple IPMs in parallel, the framework enhances search diversity and enables exploration of various regions within the solution space.

Hybrid Framework Architecture

The architecture of advanced hybrid feature selection systems can be visualized as follows:

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Feature Selection in Cheminformatics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [8] [32] | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, and molecular representation | Fundamental tool for converting chemical structures into quantitative features for analysis |

| Tox21 Dataset [34] | Benchmark Data | Curated toxicity data for 12,000 environmental chemicals and drugs | Standard benchmark for evaluating feature selection methods in toxicity prediction |

| Modred Descriptor Calculator [34] | Descriptor Generator | Calculates 1,793 molecular descriptors for QSAR modeling | Creates comprehensive feature spaces requiring effective feature selection |

| Scikit-learn [11] [23] | Machine Learning Library | Implementation of RFE, filter methods, and embedded selection techniques | Primary platform for implementing and comparing feature selection algorithms |

| PubChem [8] [32] | Chemical Database | Source of chemical structures and biological activity data | Provides real-world datasets for cheminformatics model development |

| SVM-RFE [11] [10] | Feature Selection Algorithm | Recursive feature elimination using Support Vector Machines | Specifically designed for high-dimensional data with small sample sizes |

The comparative analysis of feature selection methods in cheminformatics reveals a complex trade-off landscape where no single approach dominates all considerations. Filter methods provide computational efficiency and high interpretability but may sacrifice performance on complex structure-activity relationships. Wrapper methods can capture feature interactions and deliver superior predictive accuracy but demand substantial computational resources and may overfit. RFE and embedded methods offer a practical compromise, balancing performance with manageable computational costs.

For cheminformatics researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal feature selection strategy depends on specific project constraints and objectives. In early discovery phases with large feature spaces, filter methods provide efficient initial screening. For lead optimization with established compound series, wrapper methods can extract maximum predictive accuracy from smaller, more focused datasets. RFE approaches offer particular value in QSAR modeling, where they balance performance with interpretability requirements.

The emerging generation of hybrid frameworks that mediate between filter and wrapper methods represents the most promising direction, potentially offering both computational efficiency and high performance while maintaining interpretability. As cheminformatics continues to grapple with increasingly complex datasets and challenging prediction tasks, sophisticated feature selection will remain essential for building models that are both predictive and scientifically informative.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Feature Selection in Drug Discovery Pipelines

Implementing Correlation-Based and Statistical Filter Methods

In the data-rich field of cheminformatics, identifying the most relevant molecular features from high-dimensional datasets is a critical step in building predictive models for tasks like activity prediction and property forecasting. Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three paradigms: filters, which use statistical metrics to select features independent of a learning algorithm; wrappers, which use the model's performance as an objective function to identify useful features; and embedded methods, where feature selection is integrated into the model training process itself [2]. A persistent "best method" paradigm often drives researchers to seek a single superior approach [37]. However, contemporary evidence increasingly suggests that the optimal strategy is highly context-dependent, with hybrid methods often delivering superior results by leveraging the complementary strengths of different techniques [37].