Harnessing dCas9 Systems: A Comprehensive Guide to Reversible Gene Expression Control for Research and Therapy

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of dead Cas9 (dCas9) systems, which have revolutionized genetic research by enabling precise, reversible control over gene expression without creating DNA double-strand breaks.

Harnessing dCas9 Systems: A Comprehensive Guide to Reversible Gene Expression Control for Research and Therapy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of dead Cas9 (dCas9) systems, which have revolutionized genetic research by enabling precise, reversible control over gene expression without creating DNA double-strand breaks. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa), detailing their core mechanisms and key advantages over nuclease-active Cas9. The scope extends to advanced methodological applications across diverse cell types, including high-throughput screening and cell reprogramming, alongside practical strategies for troubleshooting common issues like variable knockdown efficiency. Finally, the article presents rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses with alternative gene-editing technologies, synthesizing key takeaways to highlight the transformative potential of dCas9 systems in functional genomics and the development of next-generation therapeutics.

The dCas9 Revolution: Understanding the Core Principles of Reversible Gene Control

FAQ: Understanding dCas9 Fundamentals

What is dCas9 and how does it fundamentally differ from CRISPR-Cas9?

dCas9, or "dead" Cas9, is a catalytically inactivated form of the CRISPR-associated protein 9. While the active Cas9 protein functions as a molecular "scissor" to create double-stranded breaks in DNA, dCas9 has point mutations (D10A and H840A for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) that disable its nuclease activity [1] [2]. This crucial modification allows dCas9 to still target and bind to specific DNA sequences guided by a gRNA, but without cutting the DNA [1]. It thus transitions from a destructive tool to a precise targeting platform that can be fused with various effector domains for multiple applications beyond simple gene editing [3] [2].

What are the primary technical advantages of using dCas9 over conventional CRISPR-Cas9?

The key advantages of dCas9 systems include:

- Reversible gene expression control: Unlike permanent knockout mutations created by Cas9, dCas9-mediated transcriptional or epigenetic modulation can be temporary and reversible [4] [3].

- Reduced cellular toxicity and DNA damage: By eliminating double-stranded DNA breaks, dCas9 avoids triggering the DNA damage response, p53 pathway activation, and reduces the risk of chromosomal translocations and large deletions [1].

- Precise spatial and temporal control: When coupled with inducible systems or light-sensitive domains (Opto-CRISPR), dCas9 enables precise control over when and where gene regulation occurs [5].

- Multiplexed regulation: Multiple dCas9-effector fusions can be targeted to different genomic loci simultaneously to regulate complex gene networks [3].

What are the main applications of dCas9 in research and therapeutic contexts?

dCas9 serves as a versatile platform for numerous applications:

- Transcriptional modulation (CRISPRi/CRISPRa): By fusing dCas9 to transcriptional repressors (KRAB) or activators (VP64, p65), researchers can precisely downregulate or upregulate gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [3].

- Epigenetic editing: dCas9 fused to epigenetic modifiers (DNMT3A for methylation, TET1 for demethylation) enables targeted rewriting of epigenetic marks to study and potentially reverse disease-associated epigenetic states [4] [3].

- Genome imaging: dCas9 fused to fluorescent proteins allows visualization of specific genomic loci in living cells [3].

- High-throughput screening: dCas9-based libraries enable genome-wide functional screens to identify genes involved in specific biological processes or disease states [5].

dCas9 Applications Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparison of major dCas9 application systems and their key characteristics

| Application Type | Common Effector Domains | Primary Function | Persistence of Effect | Key Research Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional Repression (CRISPRi) | KRAB, SID4x | Suppresses gene transcription | Transient to days | Gene knockdown studies, functional genomics, pathway analysis |

| Transcriptional Activation (CRISPRa) | VP64, p65, Rta | Enhances gene transcription | Transient to days | Gene upregulation, differentiation studies, gene therapy |

| Epigenetic Editing (DNA Methylation) | DNMT3A, DNMT3L | Adds methyl groups to CpG islands | Weeks to months | Studying epigenetic memory, disease modeling, epigenetic therapy |

| Epigenetic Editing (DNA Demethylation) | TET1, TET2 | Removes methyl groups from DNA | Weeks to months | Reactivating silenced genes, epigenetic reprogramming |

| Genome Imaging | GFP, mCherry | Visualizes genomic loci | Real-time | Nuclear organization, chromatin dynamics, live-cell imaging |

Experimental Protocols for dCas9 Applications

Protocol: Targeted Epigenetic Editing with dCas9-TET1 for Gene Reactivation

This protocol details the use of dCas9-TET1 for targeted DNA demethylation and gene reactivation, based on recent research demonstrating successful epigenetic reprogramming [4].

Materials Required:

- dCas9-TET1 fusion construct (addgene #98476 or similar)

- sgRNA expression vector or synthetic sgRNA

- Target cells (e.g., patient-derived iPSCs, cell lines)

- Transfection reagents (lipofectamine, electroporation system)

- DNA extraction kit

- Bisulfite conversion kit for methylation analysis

- RNA extraction kit

- qPCR reagents for gene expression analysis

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- sgRNA Design and Validation: Design 2-3 sgRNAs targeting the promoter region or imprinting control region of your gene of interest. Use tools like CHOPCHOP or CRISPick to minimize off-target potential. In vitro validation of sgRNA efficiency is recommended using electromobility shift assays.

Delivery System Selection: Choose appropriate delivery method based on cell type:

- For HEK293 and similar cell lines: Lipofectamine 3000 transfection

- For primary cells and iPSCs: Electroporation (Neon or Amaxa systems)

- For hard-to-transfect cells: Lentiviral delivery (note: requires additional biosafety precautions)

Cell Transfection/Transduction:

- For plasmid transfection: Use 1:3 ratio (dCas9-TET1:sgRNA) with total DNA not exceeding 2μg per well in 6-well plate

- For RNP delivery: Complex 5μg dCas9-TET1 protein with 2μg synthetic sgRNA for 15 minutes at room temperature before delivery

Incubation and Expression: Allow 48-72 hours for maximal expression and epigenetic modification. Include controls: dCas9-only, non-targeting sgRNA, and untreated cells.

Efficiency Validation:

- Methylation Analysis: Perform bisulfite sequencing at target loci 5-7 days post-transfection. Expect 30-60% reduction in methylation at successfully targeted sites [4].

- Expression Analysis: Measure mRNA levels of target gene by qPCR 3-5 days post-transfection. Normalize to housekeeping genes.

- Functional Assessment: Conduct cell-based assays relevant to your target gene (e.g., differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis) 5-10 days post-transfection.

Persistence Monitoring: Track epigenetic changes and gene expression weekly for 4-6 weeks to determine stability of modifications. For transient effects, consider repeated delivery for maintained effect.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low demethylation efficiency: Optimize sgRNA design, increase dCas9-TET1 concentration, or extend incubation time

- Cellular toxicity: Reduce DNA/RNA concentrations, switch to RNP delivery, or use milder electroporation settings

- Off-target effects: Include multiple sgRNA controls, use high-fidelity dCas9 variants, and analyze potential off-target sites by bisulfite sequencing

Troubleshooting Guide for Common dCas9 Experimental Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting common issues in dCas9 experiments

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low target gene modulation | Inefficient sgRNA, poor dCas9 expression, chromatin inaccessibility | Test multiple sgRNAs; optimize delivery method; use chromatin-opening agents | Validate sgRNAs with dCas9-GFP; use positive control sgRNA; choose accessible genomic regions confirmed by ATAC-seq |

| High off-target effects | Non-specific sgRNA binding, excessive dCas9 expression | Use truncated sgRNAs; employ high-fidelity dCas9 variants; reduce dCas9 concentration | Perform careful bioinformatic sgRNA design; use modified sgRNAs with enhanced specificity; employ orthogonal validation methods |

| Cellular toxicity | Overexpression of dCas9 or effector domains, delivery method | Titrate dCas9 to lowest effective dose; switch delivery method; use inducible systems | Use self-inactivating vectors; employ milder transfection methods; monitor cell viability 24h post-delivery |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Variable delivery efficiency, cell state heterogeneity | Standardize delivery protocol; use larger cell numbers; include internal controls | Use stable cell lines; implement precise cell counting; maintain consistent cell passage numbers |

| Short duration of effect | Epigenetic reversal, cell division dilution, protein degradation | Use multiple dosing; employ more stable epigenetic effectors; create stable cell lines | Choose persistent epigenetic editors (e.g., dCas9-DNMT3A); use integration competent vectors; select slowly dividing cells |

Research Reagent Solutions for dCas9 Experiments

Table 3: Essential reagents and tools for dCas9 research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Systems | dCas9-KRAB (Addgene #126579), dCas9-VP64 (Addgene #122214), dCas9-TET1 (Addgene #98476) | Core effector fusions for transcriptional and epigenetic regulation; choose based on desired outcome |

| Guide RNA Formats | Chemically modified synthetic sgRNAs, IVT sgRNAs, plasmid-based sgRNAs | Modified synthetic guides offer enhanced stability and reduced immune response; ideal for primary cells [6] |

| Delivery Tools | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Electroporation systems, AAV vectors (AAV-DJ/AAV9), Lentiviral particles | LNPs enable transient delivery with minimal immune response; viral vectors provide sustained expression [7] |

| Validation Assays | RNA-seq kits, Bisulfite sequencing kits, ATAC-seq kits, ChIP-seq kits | Multi-omics validation essential for confirming on-target effects and detecting potential off-target changes |

| Control Reagents | Non-targeting sgRNAs, dCas9-only constructs, GFP-reporters | Critical for distinguishing specific from non-specific effects; include in every experiment |

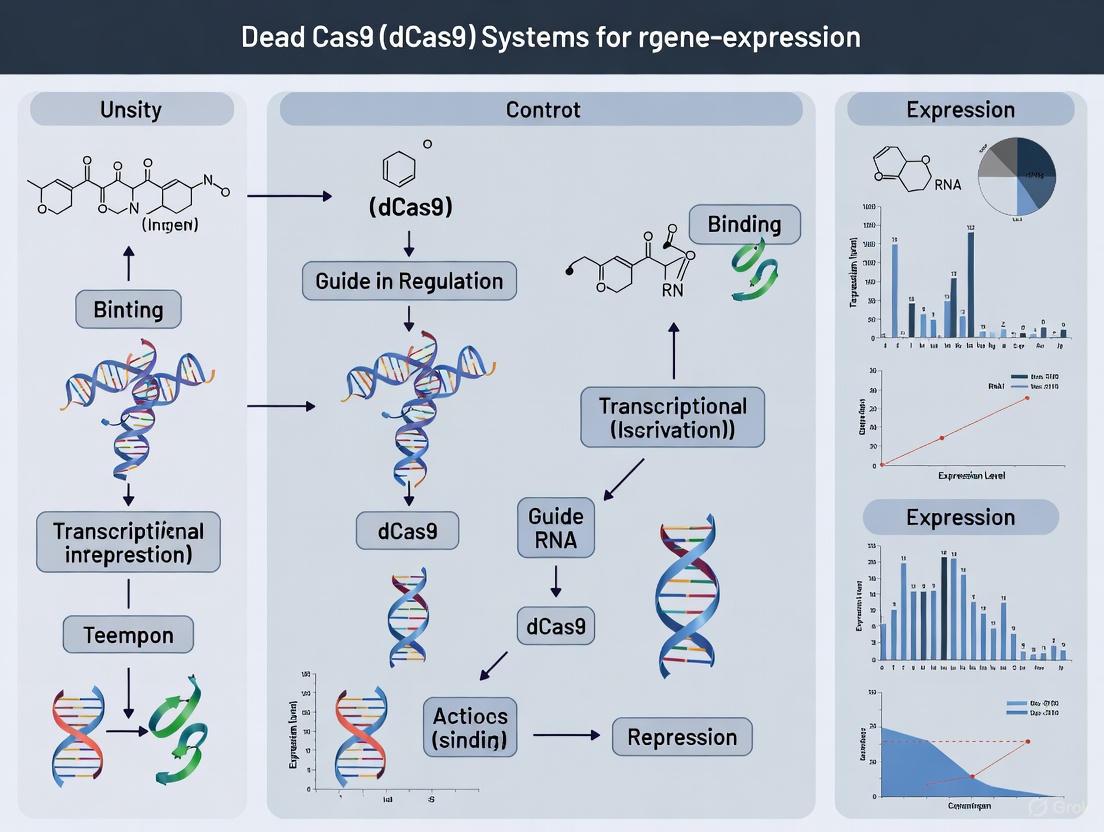

dCas9 Transcriptional Regulation Workflow Diagram

Diagram 1: dCas9 experimental workflow and key considerations

dCas9 Mechanism of Action Diagram

Diagram 2: dCas9 mechanism and functional outcomes

Core FAQs: Fundamental Mechanisms

Q1: What are CRISPRi and CRISPRa, and how do they fundamentally differ from CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko)?

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) are technologies derived from the CRISPR/Cas9 system that enable reversible, programmable control over gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Unlike CRISPR knockout, which uses nuclease-active Cas9 to create permanent double-stranded DNA breaks and disrupt gene function, CRISPRi/a utilizes a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that retains its DNA-binding capability but cannot cut DNA [8] [9] [10].

- CRISPRi silences or represses gene transcription.

- CRISPRa activates or increases gene transcription.

- Both systems function as a "gene dimmer switch," allowing for tunable and reversible control of gene expression levels, whereas CRISPRko acts as a permanent "on/off switch" [9] [10]. This makes them particularly valuable for studying essential genes, modeling drug effects, and investigating complex gene networks [9] [11].

Q2: What is the core component that enables transcriptional control in these systems?

The core component is the dCas9 protein. It is created by introducing point mutations (commonly D10A and H840A in the Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes) that inactivate the two nuclease domains responsible for DNA cleavage (RuvC and HNH) [8] [10]. This dCas9 becomes a programmable DNA-binding module that can be directed to any genomic location by a guide RNA (gRNA) but does not cause DNA damage [12] [11]. Transcriptional control is achieved by fusing this dCas9 to effector domains that influence the local chromatin environment and recruitment of RNA polymerase [13] [9].

Q3: How does dCas9, guided by an RNA molecule, find its specific DNA target?

The targeting specificity is conferred by a single guide RNA (sgRNA), a synthetic RNA molecule that combines the functions of the natural bacterial crRNA and tracrRNA [8] [12]. The sgRNA contains a ~20 nucleotide "spacer" sequence that is complementary to a specific DNA target site. This guides the dCas9-effector fusion complex to bind to that specific locus in the genome. The target site must be adjacent to a short DNA sequence known as a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM); for the commonly used SpCas9, this is the sequence 5'-NGG-3' [13] [12].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CRISPRi, CRISPRa, and Alternative Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Genetic Alteration? | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi | Transcriptional repression at DNA level [8] | No; reversible [14] | Fewer off-target effects than RNAi; titratable [10] [11] | Requires delivery of dCas9-repressor fusion |

| CRISPRa | Transcriptional activation at DNA level [13] | No; reversible [15] | Drives endogenous gene expression; reveals gain-of-function [10] [11] | Activation level can be promoter-dependent |

| CRISPRko | Creates DNA double-strand breaks [8] | Yes; permanent [9] | Complete gene disruption | Cytotoxic; not suitable for essential genes [9] |

| RNAi | mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm [8] | No | Well-established delivery methods | Cytoplasmic activity; can have off-target effects [8] [10] |

Mechanism Visualization: From dCas9 to Transcriptional Control

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanisms of CRISPRi and CRISPRa, showing how different dCas9-effector fusions achieve transcriptional repression or activation.

Diagram 1: Core transcriptional control mechanisms of CRISPRi and CRISPRa. CRISPRi fuses dCas9 to repressor domains like KRAB, which block RNA polymerase or recruit chromatin-condensing complexes. CRISPRa fuses dCas9 to activator domains that recruit the transcriptional machinery to the promoter.

Experimental Design & Troubleshooting

Q4: Where should I design my gRNA for effective CRISPRi or CRISPRa?

The optimal gRNA binding site is critically dependent on the desired outcome and is different from the site used for CRISPRko [10].

- For CRISPRi: The most effective gRNAs target a window from -50 to +300 base pairs relative to the Transcription Start Site (TSS), with the highest efficacy often found within the first 100 bp downstream of the TSS [10] [11]. Binding here allows dCas9 to physically block the progression of RNA polymerase.

- For CRISPRa: The most effective gRNAs target a window from -400 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS [10]. Binding in this promoter/enhancer region allows the activator domains to effectively recruit the transcription machinery without steric hindrance.

Q5: What are the latest advanced effector systems for enhanced regulation?

Early CRISPRa systems using simple dCas9-VP64 fusions showed modest activation. More powerful systems have been developed that recruit multiple distinct activator domains simultaneously [10] [11]. Key advanced platforms include:

- SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator): Uses an engineered sgRNA with MS2 RNA aptamers that recruit additional activator proteins (p65 and HSF1), creating a powerful multi-component activation complex [10] [11].

- VPR: A tripartite fusion of dCas9 directly to three activator domains: VP64, p65, and Rta [11].

- SunTag: A system where dCas9 recruits a tandem array of peptide epitopes, which in turn bind multiple copies of an antibody-activator (e.g., VP64) fusion protein, leading to highly synergistic activation [9] [11].

For CRISPRi, recent research has focused on engineering more potent repressors, such as dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB)-MeCP2(t), which shows improved repression across diverse cell lines and gene targets [14].

Q6: What are common reasons for low efficiency, and how can I troubleshoot them?

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for CRISPRi/a Experiments

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Low Knockdown/Activation | Suboptimal gRNA design or target site chromatin inaccessibility [9] [10] | - Verify TSS annotation for your gene.- Design and test 3-5 gRNAs per gene.- Use algorithms to predict gRNA efficacy. |

| Low dCas9-effector expression | - Use a strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., EF1α).- Validate protein expression via Western blot.- Use a fluorescent reporter (e.g., BFP) fused to dCas9 to sort for high-expression cells [15]. | |

| Inefficient effector domain | - For CRISPRa, switch to a more powerful system (e.g., SAM, VPR) [11].- For CRISPRi, consider newer engineered repressors like dCas9-ZIM3(KRAB) [14]. | |

| High Background Noise/Off-Target Effects | gRNA sequence specificity | - Use bioinformatics tools to check for off-target sites with ≥12 bp homology plus PAM.- Use a non-targeting control gRNA in all experiments [13] [16]. |

| Non-specific dCas9 binding | - Use high-fidelity dCas9 variants [8].- Ensure delivery of components is not in vast excess. | |

| No Phenotype in Screen | Inadequate library coverage or low cell viability | - Maintain a high representation (500-1000x) of each gRNA in the screened cell population.- Optimize viral transduction to avoid multiple integrations per cell [11]. |

Key Research Reagents and Workflows

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for setting up and executing a CRISPRi or CRISPRa experiment, from initial system selection to phenotypic readout.

Diagram 2: A general workflow for a CRISPRi/a experiment, highlighting key decision points from system selection to final analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPRi/a

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples & Formats | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Effector Systems | - Lentiviral vectors for dCas9-KRAB (CRISPRi) [11]- All-in-one lentiviral vectors for dCas9-SAM (CRISPRa) [16]- Purified dCas9-effector protein for RNP delivery [16] | Provides the core DNA-binding and transcriptional modulation function. Format choice depends on application (e.g., screening vs. single-gene study). |

| Guide RNAs (gRNAs) | - Synthetic sgRNA or crRNA:tracrRNA for DNA-free workflows [16]- Lentiviral sgRNA for stable expression [16] [15]- Genome-scale pooled libraries (e.g., 3-10 gRNAs/gene) [13] [10] | Programs the system to target a specific genomic locus. Synthetic RNAs are fast and minimize off-target integration; lentiviral are for stable/ difficult cells. |

| Control Reagents | - Non-targeting control gRNAs [13] [16]- gRNAs targeting "safe harbor" loci (e.g., AAVS1) [16]- gRNAs for positive control genes (e.g., essential genes) [16] | Essential for validating system performance and distinguishing specific from non-specific effects. |

| Delivery Tools | - Lipid nanoparticles or electroporation for synthetic RNA/protein [12]- Lentiviral particles for stable integration [11] [15]- "CRISPR-ready" stable cell lines expressing dCas9 effectors [16] | Enables efficient introduction of CRISPR components into the target cells. Choice is critical and depends on cell type. |

In the field of genetic engineering, the advent of the CRISPR-Cas9 system has provided researchers with an unprecedented ability to modify genomes. However, many research and therapeutic scenarios demand temporary, reversible intervention rather than permanent genetic alteration. This technical support center focuses on dead Cas9 (dCas9), a catalytically inactive variant that has emerged as the cornerstone for reversible gene expression control. Derived from the standard Cas9 nuclease, dCas9 is engineered through point mutations (D10A and H840A) in its RuvC and HNH nuclease domains, rendering it incapable of cleaving DNA while retaining its programmable DNA-binding capability [17]. This fundamental distinction positions dCas9 as a powerful tool for transient epigenetic remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and functional genomics studies where reversibility is paramount [8] [18].

Unlike permanent editing tools that create double-strand breaks and introduce irreversible changes via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), dCas9-based systems achieve reversible control through steric hindrance and recruitment of effector domains without altering the underlying DNA sequence [19] [20]. This technical resource provides comprehensive troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to help researchers effectively implement dCas9 technologies, addressing common challenges and optimizing workflows for reversible gene expression control applications in basic research and drug development.

Technical Comparison: dCas9 vs. Permanent Editing Tools

Understanding the fundamental operational differences between reversible dCas9 systems and permanent genome editing tools is critical for selecting the appropriate technology for your experimental goals. The table below summarizes the key technical distinctions:

Table 1: Comparison of dCas9 systems versus permanent genome editing tools

| Feature | dCas9-Based Systems | Permanent Editing (Cas9 Nuclease) |

|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Activity | Catalytically inactive (no DNA cleavage) | Active (creates double-strand breaks) |

| DNA Lesion | None | Double-strand break |

| Primary Mechanism | Steric hindrance & effector domain recruitment | NHEJ/HDR repair pathways |

| Persistence of Effect | Transient and reversible | Permanent and irreversible |

| Key Applications | Transcriptional regulation, epigenetic studies, functional screening | Gene knockout, gene correction, knock-in |

| Common Delivery Format | Plasmid DNA, mRNA | RNP, plasmid DNA |

| Typical Outcome | Reversible gene expression modulation | Permanent sequence alteration |

The core distinction lies in the reversibility of effects. dCas9 systems achieve temporary gene repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) by blocking transcription factors or recruiting epigenetic modifiers, with effects diminishing as dCas9 dissociates and cellular processes reverse the modifications [8] [18]. In contrast, active Cas9 nuclease creates permanent DNA sequence changes through cellular repair mechanisms that introduce insertions, deletions, or precise edits via donor templates [20]. For research requiring repeated on/off gene regulation or temporal studies of gene function, dCas9 provides a clear advantage, while permanent editing is superior for creating stable cell lines or correcting disease-causing mutations.

Troubleshooting Common dCas9 Experimental Challenges

Low Gene Repression/Activation Efficiency

Problem: Inadequate modulation of target gene expression following dCas9 delivery.

Solutions:

- Verify gRNA Design: Ensure gRNA sequence is complementary to the template strand within the promoter region, ideally 50-100 bp upstream of the transcription start site for CRISPRi [18]. Use bioinformatics tools to select gRNAs with optimal GC content (40-60%) and minimal off-target potential.

- Optimize Effector Domain Selection: For stronger repression, use dCas9 fused to transcriptional repressors like KRAB rather than dCas9 alone. For enhanced activation, employ dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VPR, or SunTag systems [17] [18].

- Check Component Expression: Confirm efficient delivery and expression of both dCas9 and gRNA components. Use Western blotting for dCas9 detection and qRT-PCR for gRNA quantification. Consider codon-optimizing dCas9 for your cell type and using strong, cell-type-appropriate promoters [21].

- Validate Target Accessibility: Chromatin condensation can impede dCas9 binding. Consider targeting accessible regions confirmed by ATAC-seq or DNase-seq data, or use dCas9 fused to chromatin-opening domains [20].

High Off-Target Effects

Problem: dCas9 binding to unintended genomic sites causing non-specific gene regulation.

Solutions:

- Implement Specific gRNA Designs: Truncate gRNAs to 17-18 nucleotides to reduce off-target binding while maintaining on-target activity [8] [20]. Avoid gRNAs with high similarity to other genomic regions, especially near the PAM site.

- Use High-Fidelity dCas9 Variants: Employ evolved dCas9 variants with mutated DNA-binding domains that increase specificity by requiring perfect gRNA:DNA complementarity [20].

- Employ Paired Nickase Systems: Use two gRNAs with Cas9 nickase (nCas9) variants that target adjacent sites on opposite DNA strands, requiring both binding events for functional outcomes [20].

- Optimize Delivery and Dosage: Utilize ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes of preassembled dCas9-gRNA for transient activity that reduces off-target effects. Titrate dCas9-gRNA amounts to the minimum required for efficient on-target activity [20].

Cell Toxicity and Viability Issues

Problem: Reduced cell viability following dCas9 system delivery.

Solutions:

- Modulate Expression Levels: High, constitutive dCas9 expression can cause cellular stress. Use inducible systems (doxycycline, cumate) for transient expression or lower-strength promoters to reduce burden [21].

- Switch Delivery Methods: Viral vectors (particularly lentivirus) can cause prolonged expression and toxicity. Consider transient transfection of plasmid DNA or mRNA, or delivery as RNP complexes [20].

- Verify Effector Domain Compatibility: Some transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64) and repressors (e.g., KRAB) can be cytotoxic at high levels or when targeting certain genes. Titrate expression levels and include empty vector controls to distinguish technology-related toxicity from target-related effects.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for CRISPR Interference (CRISPRi) Using dCas9-KRAB

Principle: This protocol describes sequence-specific gene repression using dCas9 fused to the KRAB transcriptional repressor domain, which recruits chromatin-modifying complexes to promote heterochromatin formation [17].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- gRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design gRNAs targeting the promoter region of your gene of interest, ideally between -50 and -100 bp relative to the transcription start site.

- Clone gRNA sequence into appropriate expression vector (e.g., Addgene plasmid #47108) using BsmBI restriction sites.

- Transform into competent E. coli, select colonies, and verify sequence by Sanger sequencing.

Cell Line Preparation:

- Culture HEK293T or your target cell line in appropriate medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- For lentiviral production, seed HEK293T cells in 6-well plates at 60-70% confluence 24 hours before transfection.

Lentiviral Production (Optional):

- Co-transfect dCas9-KRAB expression vector, gRNA vector, and packaging plasmids (psPAX2 and pMD2.G) using polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent.

- Replace medium after 6-8 hours with fresh complete medium.

- Collect viral supernatant at 48 and 72 hours post-transfection, filter through 0.45μm membrane, and concentrate using PEG-it virus precipitation solution if needed.

Cell Transduction and Selection:

- Transduce target cells with viral supernatant plus 8μg/mL polybrene via spinfection (centrifuge at 600 × g for 60 minutes at 32°C) or standard incubation.

- Begin antibiotic selection (e.g., puromycin, blasticidin) 48 hours post-transduction based on resistance markers in your vectors.

- Maintain selection for at least 5-7 days to establish stable polyclonal cell lines.

Efficiency Validation:

- Harvest cells 5-7 days post-selection for analysis.

- Quantify gene expression changes by qRT-PCR for mRNA levels and/or Western blot for protein levels.

- Assess repression efficiency relative to non-targeting gRNA control.

- For single-cell analysis, perform flow cytometry if targeting a surface marker or using a fluorescent reporter system.

Diagram: CRISPRi experimental workflow for gene repression

Protocol for Transcription Factor Binding Site Disruption (CRISPRd)

Principle: CRISPR disruption (CRISPRd) uses dCas9 without effector domains to sterically hinder transcription factor binding to specific genomic sites, enabling functional analysis of individual regulatory elements [19].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Target Site Identification:

- Identify transcription factor binding sites of interest using ChIP-seq data or motif prediction algorithms.

- Design gRNAs that directly overlap the binding site and include 8-10 bp of flanking sequence to ensure specificity.

dCas9 and gRNA Delivery:

- Use a dual-vector system with doxycycline-inducible dCas9-mCherry and constitutive gRNA expression.

- Deliver both vectors simultaneously via lentiviral transduction or transient transfection depending on cell type.

Induction and Timing:

- Induce dCas9 expression with 1-2 μg/mL doxycycline 48 hours post-transduction.

- Harvest cells at 24, 48, and 72 hours post-induction for time-course experiments.

Functional Assessment:

- Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for the transcription factor of interest to confirm displacement from the target site.

- Measure expression changes of the putative target gene by qRT-PCR.

- Assess phenotypic consequences relevant to the transcription factor's function (e.g., proliferation, differentiation).

Reversibility Testing:

- Remove doxycycline from culture medium to turn off dCas9 expression.

- Monitor recovery of transcription factor binding and gene expression at 24-hour intervals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of dCas9 technologies requires appropriate selection of molecular tools and delivery systems. The table below outlines essential reagents and their functions:

Table 2: Key research reagents for dCas9 experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Variants | Programmable DNA binding without cleavage | dCas9 (D10A, H840A), dCas9-KRAB (repression), dCas9-VP64/VPR (activation), dCas9-p300 (activation) [17] [18] |

| Expression Vectors | Delivery of dCas9 and gRNA components | Lentiviral, piggyBac, episomal plasmids with EF1α, CAG, or inducible promoters; all-in-one or separate vectors |

| Guide RNA Designs | Target sequence specification | 20-nt complementarity region, U6 promoter, minimal structural motifs to prevent hairpins [20] |

| Delivery Methods | Introduction into cells | Lentivirus, AAV, lipid nanoparticles (lipofection), electroporation [20] |

| Validation Tools | Confirmation of editing efficiency | qRT-PCR, Western blot, flow cytometry, RNA-seq, ChIP-qPCR, next-generation sequencing |

When selecting reagents, consider your experimental timeline and desired persistence of dCas9 expression. For transient experiments (1-2 weeks), plasmid transfection or RNP delivery is ideal. For long-term studies, lentiviral integration or stable cell line generation provides consistent expression. Always include appropriate controls: non-targeting gRNAs, empty vector controls, and wild-type cells to distinguish specific from non-specific effects.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How is dCas9 different from active Cas9 nuclease? dCas9 contains point mutations (D10A and H840A) in its RuvC and HNH nuclease domains that abolish DNA cleavage activity while preserving DNA-binding capability. This allows dCas9 to target specific genomic loci without creating double-strand breaks, enabling reversible gene regulation rather than permanent editing [17] [20].

Q2: Can dCas9 systems edit genes without creating double-strand breaks? Yes, this is a fundamental advantage of dCas9 systems. While they cannot directly edit DNA sequences, they can modulate gene expression through steric hindrance or recruitment of epigenetic modifiers without damaging DNA [8] [18]. For precise single-base editing without double-strand breaks, base editing systems (which use Cas9 nickase fused to deaminase enzymes) represent an alternative technology [22].

Q3: What factors influence the reversibility of dCas9-mediated effects? Reversibility depends on dCas9 persistence, the nature of the epigenetic modification, and cell division rate. Transient delivery methods (mRNA, RNP) offer faster reversal than integrated viral vectors. Histone modifications typically reverse more quickly than DNA methylation. Effects reverse most rapidly in dividing cells as modified nucleosomes are diluted [19] [18].

Q4: How can I improve the specificity of my dCas9 system to reduce off-target effects?

- Use truncated gRNAs (17-18 nt) instead of full-length (20 nt) gRNAs

- Select high-fidelity dCas9 variants with reduced off-target binding

- Express dCas9 at minimal effective levels using inducible systems

- Deliver as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for shorter activity windows

- Perform careful bioinformatic gRNA design to avoid off-target sites [8] [20]

Q5: What delivery method is most suitable for dCas9 experiments? The optimal delivery method depends on your cell type and experimental needs. Lentiviral vectors enable stable expression in hard-to-transfect cells. Adenoviral vectors and plasmid transfection work well for transient expression in amenable cell lines. Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes offer the most transient activity with minimal off-target effects but require specialized delivery techniques like electroporation [20].

Q6: How long do dCas9-mediated effects typically last after induction? Effects typically persist for 3-10 days after dCas9 induction or delivery, depending on the stability of the epigenetic modifications and the delivery method. Lentiviral-mediated expression can maintain effects for weeks, while RNP delivery typically lasts 2-4 days. The repression/activation magnitude usually peaks around 3-5 days post-induction [19] [18].

Diagram: Decision guide for selecting gene regulation tools

Core dCas9 System Components: FAQs

Q: What is dCas9 and how does it differ from active Cas9? A: dCas9, or "dead" Cas9, is a catalytically inactive form of the CRISPR-associated protein 9. It contains point mutations (D10A and H840A for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) in its two nuclease domains, RuvC and HNH, which render it unable to cleave DNA [23] [24]. Unlike active Cas9, which creates double-stranded breaks, dCas9 retains its ability to bind DNA based on guide RNA (gRNA) complementarity, serving as a programmable DNA-targeting platform [8] [25].

Q: What are the primary applications of dCas9 systems? A: dCas9 serves as a foundation for diverse transcriptional and epigenetic regulatory tools. When fused to different effector domains, it can be used for:

- CRISPR interference (CRISPRi): Repressing gene expression by blocking RNA polymerase [8] [26].

- CRISPR activation (CRISPRa): Activating gene expression by recruiting transcriptional activators [8] [12].

- Epigenetic engineering: Modifying DNA methylation or histone marks to alter chromatin state [24].

- Genome imaging: Tagging specific genomic loci in living cells [25].

Q: What are the key considerations for designing a dCas9 experiment? A: Successful experiments require careful planning of three core components:

- dCas9 variant selection: Choosing the appropriate dCas9 protein (e.g., dSpCas9, high-fidelity versions) based on PAM requirements and specificity needs [23].

- Effector domain choice: Selecting activators, repressors, or epigenetic modifiers based on the desired outcome [27] [24].

- sgRNA design: Designing guides with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects for the specific application [28].

Effector Domains: Principles and Selection

Effector domains are protein modules that, when fused to dCas9, confer transcriptional or epigenetic regulatory activity. They enable targeted gene activation or repression without altering the underlying DNA sequence.

Table 1: Common Effector Domains for Transcriptional Regulation

| Domain Type | Example Domains | Function & Mechanism | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activator (AD) | VP64, p65, Rta [27] | Recruits transcriptional co-activators and RNA Pol II to enhance gene expression [27]. | Often rich in acidic amino acids, glutamine, or proline; median length ~91 aa [27]. |

| Repressor (RD) | KRAB, SID, CSD [27] [26] | Recruits chromatin-remodeling complexes that promote heterochromatin formation, blocking transcription [27] [24]. | KRAB is a well-characterized, potent repressor domain [27]. |

| Bifunctional (Bif) | Some nuclear receptor domains [27] | Can activate or repress transcription depending on cellular context, cofactors, or ligand binding [27]. | Provides context-dependent regulation. |

| Epigenetic Modifiers | DNMT3A (methylation), TET1 (demethylation) [24] | Directly modifies DNA or histones to alter chromatin accessibility and gene expression potential [24]. | Can induce more stable, long-term transcriptional changes. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Effector Domain Function

To validate the function of a candidate effector domain fused to dCas9, a standardized reporter assay is recommended:

- Construct Assembly: Fuse the candidate effector domain to the C-terminus of dCas9 via a flexible peptide linker.

- Reporter Plasmid Design: Use a plasmid containing a minimal promoter driving a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase or GFP). The promoter should contain a specific DNA-binding site (e.g., Gal4) for a heterologous DNA-binding domain [27].

- Experimental Transfection:

- Co-transfect cells with:

- A plasmid expressing a Gal4-DBD fused to your candidate effector domain.

- The reporter plasmid described above.

- Include positive (e.g., Gal4-VP64) and negative (e.g., Gal4-DBD alone) controls.

- Co-transfect cells with:

- Quantification: Measure reporter gene activity (e.g., luminescence or fluorescence) after 24-48 hours. A significant increase (for activators) or decrease (for repressors) compared to the negative control confirms the domain's transcriptional regulatory function and sufficiency [27].

sgRNA Design for Different Applications

sgRNA design is critical for success and varies significantly depending on the experimental goal.

Table 2: Key Design Parameters for Different dCas9 Applications

| Application | Optimal Target Location | Key Design Considerations | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi / Repression | Promoter region, especially near transcription start site (TSS) [25]. | Target the non-template strand for stronger repression [25]. Avoid nucleosome-occupied regions. | Block RNA polymerase binding or elongation [8]. |

| CRISPRa / Activation | Enhancer or promoter region upstream of the TSS [28]. | The target location is often a narrow window; precision is more critical than for knockouts [28]. | Recruit transcriptional machinery to initiate gene expression [8]. |

| Epigenetic Editing | Promoter or enhancer of the target gene [24]. | Efficiency depends on the initial methylation state of the target region [24]. | Alter chromatin state to stably activate or silence a gene [24]. |

sgRNA Design Workflow:

Best Practices for sgRNA Design:

- Minimize Off-Target Effects: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., Synthego, Benchling) to assess potential off-target sites. Select sgRNAs with the fewest and least homologous potential off-targets [8] [28].

- Optimize On-Target Activity: Select sgRNAs with a high on-target score. Guides with a GC content between 40-60% and higher GC content near the PAM site generally show higher efficiency [8] [28].

- Consider Multiplexing: For enhanced repression or to target large genomic regions, use multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene or locus simultaneously [28] [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q: My dCas9-effector system shows no regulatory effect. What could be wrong? A:

- Verify sgRNA Design: Confirm your sgRNA targets the correct region (promoter for repression/activation). Use established algorithms to check for predicted activity [28].

- Check Component Expression: Ensure both dCas9-effector fusion and sgRNA are expressed in your cells via Western blot (for the fusion) and RT-qPCR (for the sgRNA).

- Optimize Effector Domain Strength: For weak effects, consider using a more potent effector (e.g., KRAB for repression) or a synergistic combination like VP64-p65-Rta (for activation) [27].

- Assess Chromatin Accessibility: The target site may be in a densely packed heterochromatin region. Consult public datasets (e.g., ENCODE) for ATAC-seq or DNase-seq data to choose an accessible target site [24].

Q: I observe high off-target effects. How can I improve specificity? A:

- Use High-Fidelity dCas9 Variants: Switch to engineered dCas9 proteins like eSpCas9(1.1) or SpCas9-HF1, which have reduced off-target binding [23].

- Refine sgRNA Design: Use truncated sgRNAs (shorter than 20 nt) and avoid guides with high similarity to other genomic sites, especially in the seed sequence [8] [23].

- Tune Expression Levels: Lower the expression level of the dCas9-effector protein, as high concentrations can exacerbate off-target binding. Use inducible or weaker promoters [8].

Q: What are the major delivery challenges for dCas9 systems? A: The primary challenge is the large size of dCas9-effector fusions, which often exceeds the packaging capacity of common viral vectors like Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV). Solutions include:

- Split Systems: Delivering dCas9 in separate parts.

- Smaller Cas Orthologs: Using dCas9 from other species with smaller sizes.

- Non-Viral Delivery: Employing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or polymer-based vectors, which have a higher cargo capacity [12] [25] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for dCas9-Based Transcription Regulation Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Effector Plasmid | Expresses the nuclease-dead Cas9 fused to your chosen activator, repressor, or epigenetic modifier. | Core component for targeting the system to a DNA sequence. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Expresses the single guide RNA that directs dCas9 to the specific genomic locus. | Can be cloned into a plasmid with the dCas9-effector or delivered separately. |

| High-Fidelity dCas9 Variants | Engineered dCas9 proteins (e.g., eSpCas9, HypaCas9) with reduced off-target effects. | Critical for applications requiring high specificity, such as therapeutic development [23]. |

| Modified gRNA Scaffolds | gRNA scaffolds with incorporated RNA aptamers (e.g., MS2, PP7). | Used in advanced systems to recruit additional effector proteins to the target site [24]. |

| Reporter Assay Systems | Plasmids with a minimal promoter and a reporter gene (e.g., luciferase, GFP). | Essential for initial validation of effector domain function and system efficiency [27]. |

| Delivery Vehicles | Methods to introduce constructs into cells (e.g., LNPs, AAV, lentivirus, electroporation). | Choice depends on target cell type, cargo size, and required efficiency [12]. |

From Bench to Bedside: Methodological Strategies and Cutting-Edge Applications of dCas9

The Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM), SunTag, and VPR systems are leading platforms for robust gene activation using nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9). Each system employs a distinct protein engineering strategy to recruit transcriptional activators to target DNA sites.

The table below summarizes the core architecture of each system.

Table 1: Core Components of Major dCas9 Activator Systems

| System Name | dCas9 Fusion Component(s) | Recruited Activator(s) | Guide RNA Modification | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM [29] | dCas9-VP64 | MS2-P65-HSF1 | MS2 RNA aptamers | Three-component complex; synergistic action of VP64, p65, and HSF1 activators. |

| SunTag [30] [31] [32] | dCas9 fused to a peptide array (GCN4 epitopes) | scFv antibody domains fused to VP64 | None | Signal amplification via recruitment of up to 24 copies of an activator. |

| VPR [32] | dCas9 directly fused to VP64, p65, and Rta | None (all activators are direct fusions) | None | Single, compact protein combining three potent activation domains. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental architecture and recruitment strategies of these three systems.

Performance Comparison & Selection Guide

Choosing the right activation system depends on the target gene and cellular context, as their performance is not universal.

Table 2: Comparative Performance and Selection Criteria

| Feature | SAM | SunTag | VPR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Potency | Consistently high across many genes and cell types [32] | Very high, can be superior to SAM at some loci (e.g., twi, wg in Drosophila S2 cells) [33] [32] | Very high, often comparable to SAM and SunTag [32] |

| Cell-Type Specificity | Generally robust, but performance can vary (e.g., superior in HEK293T and HeLa, less so in U-2 OS and MCF7) [32] | Performance can be cell-type dependent; can outperform SAM in some lines (e.g., U-2 OS, MCF7) [32] | Performance can be cell-type dependent; can be the most potent in some contexts [32] |

| Locus Specificity | Effective at both promoter-proximal and some enhancer regions [33] | Can activate genes from enhancers tens of kilobases away [33] | Effective at promoter-proximal targets [32] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Effective for simultaneous activation of up to 6 genes [32] | Effective for simultaneous activation of up to 6 genes [32] | Effective for simultaneous activation of up to 6 genes [32] |

| Ideal Use Case | Standardized, high-throughput screens where consistent performance is key [29] [32] | Activating lowly-expressed or refractory genes, or for long-range enhancer studies [33] | A compact, single-vector system for potent activation without complex scaffolding [32] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My gene activation levels are low with the SAM system. What could be wrong?

- Check gRNA design and placement: Ensure your gRNA is targeting the region 0-300 bp downstream of the transcription start site (TSS). TSS annotations can be inaccurate, so verify them using databases like FANTOM or Ensembl [34].

- Confirm component expression: The SAM system requires three parts: dCas9-VP64, MS2-P65-HSF1, and the sgRNA with MS2 aptamers. Verify the expression of all components in your cells [29].

- Use multiple gRNAs: Gene activation can be cooperative. Using a pool of 3-5 validated gRNAs targeting the same promoter can lead to synergistic, higher-level activation [29] [32].

- Consider your target: Some genomic loci are less accessible or responsive to certain activators. If SAM fails, try the SunTag or VPR system, as they may be more effective for your specific gene [33] [32].

Q2: I am observing cellular toxicity. Is this related to the dCas9 system I'm using?

- Reduce component concentration: High levels of dCas9, activators, or gRNA can be toxic. Titrate your transfection reagents or viral titers to find the lowest effective dose [21].

- Review your delivery method: Lipofection and electroporation can stress cells. Optimize delivery protocols for your specific cell type. Using viral vectors (lentivirus, AAV) with inducible promoters can also mitigate toxicity by controlling expression timing [21].

- Evaluate the activator: Strong, constitutive transcriptional activators can disrupt cell physiology. Consider using inducible dCas9 systems to control the timing of activation.

Q3: How do I confirm that my target gene is being repressed or activated?

- Measure mRNA levels: RT-qPCR is the most common and direct method. For repression, gene expression may drop below detection limits; in this case, the detection limit (e.g., Cq of 35-40) can be used as a placeholder for calculations [34].

- Measure protein levels: Confirm functional outcomes at the protein level using Western blot or immunofluorescence analysis [34].

- Verify on-target specificity: Perform RNA-seq to ensure that only your target gene (and potentially nearby genes) is affected, and that genome-wide off-target transcription is minimal [32].

Q4: Can I combine different activator systems to get even stronger gene expression? Extensive research has been conducted to create hybrid systems (e.g., combining SunTag dCas9 with SAM-modified gRNAs). However, these exhaustive attempts have not yielded chimeric systems with enhanced transcriptional activation beyond the already high levels achieved by the individual top systems [32].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Use this flowchart to systematically diagnose and resolve common issues in your dCas9 activation experiments.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential reagents and resources for implementing dCas9 activator systems in your research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for dCas9 Activator Systems

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Stable CRISPRa Cell Lines [29] | Cell lines (e.g., HEK293, HeLa, Jurkat) that stably express dCas9-VP64 and MS2-P65-HSF1. | Provides a convenient platform for activation studies; only requires introduction of the sgRNA-MS2 construct. |

| sgRNA-MS2 Plasmids & Lentiviruses [29] | Ready-to-use vectors or viruses containing a pool of validated sgRNAs fused to MS2 aptamers. | Ensures high-efficiency delivery and activation for your gene of interest. |

| Synthetic sgRNA (CRISPRi) [34] | Chemically synthesized single-guide RNA for transient expression. | Enables rapid gene repression (within 24-72 hours) without the need for viral delivery. |

| dCas9-SALL1-SDS3 Repressor [34] | A proprietary, potent dCas9 fusion repressor for CRISPRi. | Used for specific gene knockdown; more potent than the commonly used dCas9-KRAB repressor. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) [7] | A delivery vehicle for in vivo CRISPR therapy. | Used in clinical trials to systemically deliver CRISPR components, particularly to the liver. |

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) represents a powerful approach for precise gene knockdown in functional genomics research. Utilizing a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9), this system allows for targeted gene repression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. This technical support guide addresses common challenges and provides detailed protocols for researchers implementing CRISPRi technology, particularly within the context of reversible gene expression control studies using dCas9 systems.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

System Design and Selection

What are the key components of a functional CRISPRi system? A standard CRISPRi system requires two core components: a nuclease-dead Cas9 (dCas9) that acts as a programmable DNA-binding block, and a target-specific single guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs dCas9 to the gene of interest. The dCas9, when recruited to the non-template strand of a target gene, acts as a roadblock for RNA polymerase, resulting in targeted transcriptional repression [35]. For enhanced repression, dCas9 is often fused to repressive domains such as KRAB [36].

Which dCas9 ortholog should I use for my experiment? The choice of dCas9 ortholog can significantly impact efficiency. Research has demonstrated that the CRISPR-Cas system from Streptococcus thermophilus is efficient at targeting both reporter and endogenous genes in bifidobacteria [35]. When working with new systems, consider published validation studies or perform pilot tests comparing orthologs from different bacterial species, as PAM requirements and efficiency can vary.

How do I design effective sgRNAs for optimal knockdown?

- Positioning: sgRNAs should be designed to bind the non-template strand within the promoter or early coding regions (near transcription start sites) for optimal repression [35].

- Specificity: Use validated bioinformatic tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP) to minimize off-target effects [37].

- Validation: Always design multiple sgRNAs (at least 3-4) per gene to account for variability in efficiency [38].

Experimental Optimization

Why is my CRISPRi system showing low repression efficiency? Low efficiency can stem from several factors:

Table: Troubleshooting Low Repression Efficiency

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor sgRNA performance | Suboptimal binding site or secondary structure | Design and test multiple sgRNAs targeting different regions of the gene [38] |

| Insufficient dCas9 expression | Weak promoter, poor delivery, or protein instability | Use a stronger promoter, verify delivery efficiency, or try codon-optimized dCas9 |

| Chromatin inaccessibility | Tightly packed heterochromatin at target locus | Consider epigenetic context during sgRNA design; target accessible regions confirmed by ATAC-seq or DNase-seq [36] |

| Inadequate delivery | Low transformation/transduction efficiency | Optimize delivery protocol; for bifidobacteria, a one-plasmid system has shown success across species [35] |

How can I address variable performance between sgRNAs targeting the same gene? This is a common occurrence due to the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence, which affect editing efficiency [38]. To mitigate this:

- Include multiple sgRNAs (3-4) per gene in your experimental design [38].

- Use pooled sgRNA libraries and rely on statistical analysis that aggregates results across multiple guides [38].

- Validate individual sgRNA efficiency in pilot studies before scaling up experiments.

What selection pressure should I use for my screen? The appropriate selection pressure depends on your screening type:

- Negative Screening: Apply relatively mild selection pressure where only a subset of cells (e.g., those with essential gene knockouts) die. Identify hits by detecting sgRNA depletion in surviving populations [38].

- Positive Screening: Apply strong selection pressure where most cells die, and only a small resistant population survives. Identify hits by detecting sgRNA enrichment in survivors [38]. If no significant gene enrichment is observed, consider increasing selection pressure and/or extending screening duration [38].

Data Analysis and Validation

How much sequencing depth is required for CRISPRi screens? For reliable results, it is generally recommended that each sample achieves a sequencing depth of at least 200× [38]. The required data volume can be estimated using the formula: Required Data Volume = Sequencing Depth × Library Coverage × Number of sgRNAs / Mapping Rate For example, a typical human whole-genome knockout screen might require approximately 10 Gb per sample [38].

My mapping rate is low. Should I be concerned? A low mapping rate per se typically does not compromise result reliability, as downstream analysis focuses only on reads that successfully map to the sgRNA library [38]. The critical factor is ensuring the absolute number of mapped reads is sufficient to maintain the recommended sequencing depth (≥200×) [38]. Insufficient data volume, rather than low mapping rate, introduces variability and reduces accuracy.

How do I determine if my CRISPRi screen was successful? The most reliable method is to include well-validated positive-control genes with corresponding sgRNAs in your library [38]. Success is indicated when these controls show significant enrichment or depletion in the expected direction. In the absence of known controls, assess:

- Cellular response (degree of cell killing under selection) [38]

- Bioinformatics outputs (distribution and log-fold change of sgRNA abundance) [38]

Which statistical tools are recommended for analyzing CRISPRi screen data? MAGeCK (Model-based Analysis of Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout) is currently the most widely used tool [38]. It incorporates two primary algorithms:

- RRA (Robust Rank Aggregation): Ideal for single treatment and control group comparisons [38]

- MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimation): Supports joint analysis of multiple experimental conditions [38]

CRISPRi Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for CRISPRi Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Ortholog | Programmable DNA-binding module | S. thermophilus dCas9 [35], S. pyogenes dCas9 [39] |

| Repression Domain | Enhances gene silencing when fused to dCas9 | KRAB domain [36] |

| Delivery Vector | Plasmid system for component delivery | One-plasmid system for bifidobacteria [35], Lentiviral vectors for mammalian cells [36] |

| sgRNA Scaffold | RNA framework for target recognition | Modified scaffolds with RNA aptamers for imaging [39] |

| Selection Markers | Enables population enrichment | Antibiotic resistance genes, Fluorescent markers for FACS [38] |

| Validation Tools | Confirms target engagement and effect | qPCR for expression, Bisulfite sequencing for epigenetic edits [37] |

Advanced Applications and Methodologies

Multiplexed Imaging with CRISPRi Modified sgRNA scaffolds enable advanced applications such as live-cell imaging. By engineering sgRNAs with RNA aptamer insertions (e.g., MS2, PP7) that bind fluorescent protein-tagged effectors, researchers can achieve robust multicolor imaging of genomic elements [39]. This approach is particularly valuable for long-term tracking of chromosomal dynamics due to its tolerance to photobleaching [39].

Epigenetic Editing with Fused Effectors For targeted epigenetic modification, dCas9 can be fused to catalytic domains such as TET1, which catalyzes DNA demethylation [37]. This CRISPR/dCas9-TET1 system has been successfully used to reactivate epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressor genes like miR-200c in breast cancer cells, demonstrating the potential for therapeutic applications [37].

Multicolor Labeling of Genomic Loci The Casilio platform, which combines dCas9 with engineered Pumilio/FBF (PUF)-tethered effectors, enables imaging of nonrepetitive genomic loci using just one guide RNA per locus [40]. This system allows for visualization of dynamic chromatin interactions in live cells and can track the folding dynamics of chromatin loops with dual-color or three-color labeling [40].

CRISPRi Mechanistic Principle

Successful implementation of CRISPRi requires careful attention to system design, experimental optimization, and appropriate data analysis. By addressing these common challenges and following established guidelines, researchers can leverage CRISPRi for robust gene knockdown in their functional genomics studies. The continued development of CRISPRi tools, including enhanced imaging capabilities and epigenetic editing applications, promises to further expand the utility of this technology in reversible gene expression control research.

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) technology, based on a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9), represents a powerful tool for programmable gene upregulation. By fusing dCas9 to transcriptional activation domains and guiding it to specific genomic loci with single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), researchers can investigate gene function and explore therapeutic applications for haploinsufficient disorders [8] [41]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to help scientists effectively implement CRISPRa for endogenous gene activation within their reversible gene expression control research.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the core components of a CRISPRa system?

A CRISPRa system consists of three main components:

- dCas9: A catalytically inactive Cas9 protein that binds DNA without cutting it, serving as a programmable DNA-binding scaffold [8].

- Transcriptional Activation Domain: An effector domain (e.g., VP64, VPR) fused to dCas9 that recruits the cellular transcription machinery to initiate gene expression [41] [42].

- sgRNA: A single-guide RNA complementary to the target DNA sequence, which directs the dCas9-activator complex to specific promoter or enhancer regions [8].

FAQ 2: Why is my CRISPRa system failing to activate the target gene?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Insufficient sgRNA targeting efficiency: Design multiple sgRNAs (3-4) per gene to mitigate variability in individual sgRNA performance [38].

- Suboptimal sgRNA binding location: For strongest activation, target sgRNAs to the proximal promoter region, typically within -50 to +300 base pairs relative to the transcription start site (TSS) [43]. sgRNAs binding downstream of the TSS may sterically hinder transcription [41].

- Weak activation domain: Consider using stronger synthetic activation complexes like VPR (VP64-p65-Rta) instead of minimal VP64, especially for challenging targets [42].

- Inaccessible chromatin state: The responsiveness of individual enhancers to CRISPRa is often restricted by cell type, depending on the local chromatin landscape and availability of trans-acting factors [42].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the specificity of CRISPRa-mediated gene activation?

- Careful sgRNA design: Use bioinformatic tools to select sgRNAs with minimal off-target potential. sgRNAs with 18-21 base pair protospacers show significantly higher activity and specificity than longer versions [43].

- Avoid nucleotide homopolymers: These can strongly negatively impact sgRNA activity [43].

- Validate target engagement: Employ control experiments with mismatched sgRNAs to confirm specific binding [41].

FAQ 4: What is the typical dynamic range of gene upregulation achievable with CRISPRa?

CRISPRa enables modulation of gene expression over a wide dynamic range. When combined with CRISPRi (interference), these technologies collectively enable gene expression modulation across approximately 1000-fold range [43]. For single genes, robust activation of 6-7 fold for endogenous genes like IL1RN and SOX2 has been demonstrated using multiple sgRNAs with strong activation domains [41].

FAQ 5: How can I achieve multiplexed gene activation with CRISPRa?

Introduce multiple sgRNAs targeting different genes simultaneously. Robust multiplexed endogenous gene activation has been achieved by co-expressing sgRNAs targeting multiple genes, allowing for the study of gene networks and combinatorial gene regulation [41]. Newer approaches use random combinations of many gRNAs introduced to individual cells followed by single-cell RNA sequencing to assess multiple perturbations in parallel [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPRa System Assembly and Validation for Endogenous Gene Activation

Principle: This protocol describes how to implement a CRISPRa system to upregulate endogenous genes by targeting their promoters with multiple sgRNAs, based on established methodologies [41] [42].

Reagents Required:

- dCas9-VP160 or dCas9-VPR expression vector

- sgRNA expression backbone (e.g., piggyFlex transposon vector)

- Cell line amenable to genetic manipulation (e.g., HEK293T, K562)

- Transfection reagents

- RT-qPCR reagents for validation

- Optional: Single-cell RNA sequencing platform for multiplexed screens

Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design 3-4 sgRNAs per target gene, focusing on the proximal promoter region.

- Avoid regions downstream of the transcription start site.

- Clone sgRNAs into appropriate expression vectors.

Cell Line Preparation:

- Generate stable cell lines expressing dCas9-activator fusion (e.g., dCas9-VP160 or dCas9-VPR).

- Validate dCas9 expression and functionality using a reporter assay.

Delivery of CRISPRa Components:

- Transfect sgRNA vectors into dCas9-expressing cells.

- For multiplexed activation, transfert with a pool of sgRNAs targeting multiple genes or genomic regions.

Validation of Gene Activation:

- Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Isolve RNA and perform RT-qPCR to measure target gene expression.

- Compare to negative controls (non-targeting sgRNAs).

Advanced Applications (Optional):

- For single-cell resolution, use a multiplexed approach with random barcoding.

- Perform single-cell RNA sequencing to assess activation effects across many cells and perturbations simultaneously.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If activation is low, try a stronger activation domain (VPR instead of VP64).

- If specificity is problematic, redesign sgRNAs with better on-target scores.

- For persistent issues, verify dCas9 expression and nuclear localization.

Protocol 2: Single-Cell Multiplexed CRISPRa Screening for Regulatory Elements

Principle: This advanced protocol enables high-throughput identification of functional enhancers and promoters that drive gene expression in a cell-type-specific manner, combining CRISPRa with single-cell RNA sequencing [42].

Reagents Required:

- Library of 493+ gRNAs targeting candidate cis-regulatory elements

- piggyFlex or similar transposon-based gRNA expression vector

- dCas9-VP64 or dCas9-VPR expressing cell lines

- piggyBac transposase

- Puromycin for selection

- Single-cell RNA sequencing platform (10x Genomics)

Procedure:

Library Design and Cloning:

- Design gRNAs targeting TSS positive controls, candidate promoters, candidate enhancers, and non-targeting controls.

- Clone gRNA library into piggyFlex vector.

Cell Line Engineering:

- Use monoclonal, stably expressing dCas9-activator cell lines for consistency.

- Validate CRISPRa capacity with a minimal promoter-reporter assay.

Library Delivery and Selection:

- Transfect gRNA library and piggyBac transposase at 20:1 ratio to achieve high multiplicity of infection.

- Select transfected cells with puromycin for 7-9 days.

Single-Cell Profiling:

- Harvest cells and perform single-cell RNA sequencing.

- Capture both transcriptomes and gRNA information from each cell.

Computational Analysis:

- Assign gRNAs to individual cells based on sequencing data.

- Partition cells into test and control groups for each gRNA.

- Perform differential expression testing for all genes within 1 Mb of each gRNA target site.

- Identify "hit gRNAs" that significantly upregulate target genes using empirical FDR thresholds.

Expected Results: This approach typically identifies both promoter and enhancer-targeting gRNAs that mediate specific upregulation of intended target genes. In a proof-of-concept study, 59 activating gRNA hits were identified from 493 gRNAs, with successful gRNAs strongly enriched for targeting regions proximal to the genes they upregulated [42].

Table 1: CRISPRa Performance Metrics Across Experimental Systems

| Parameter | Performance Range | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Upregulation Fold-Change | 4-7 fold for endogenous genes [41] | IL1RN, SOX2 activation with dCas9-VP160 |

| Optimal Targeting Window | -50 to +300 bp from TSS [43] | Maximal CRISPRa activity |

| Number of sgRNAs for Reliable Targeting | 3-4 per gene [38] | Mitigates individual sgRNA variability |

| Multiplexed Screening Scale | 493 gRNAs simultaneously tested [42] | Single-cell CRISPRa screen in K562 cells and neurons |

| Specificity of Activation | 45/47 promoter-targeting gRNAs exclusively upregulated predicted target [42] | No off-target effects within 1 Mb |

| Dynamic Range | ~1000-fold (combined CRISPRa + CRISPRi) [43] | Tunable gene expression modulation |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common CRISPRa Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Poor sgRNA design, inefficient delivery, low Cas9/sgRNA expression [21] | Verify delivery method, optimize sgRNA design, check promoter suitability [21] |

| High off-target effects | Non-specific sgRNA binding [8] [21] | Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants, bioinformatics sgRNA selection, avoid homopolymers [43] [21] |

| Cell toxicity | High CRISPR component concentration [21] | Titrate component doses, use nuclear localization signals [21] |

| No significant enrichment | Insufficient selection pressure [38] | Increase selection pressure, extend screening duration [38] |

| Variable sgRNA performance | Intrinsic sgRNA sequence properties [38] | Design multiple sgRNAs per gene (3-4) [38] |

| Inconsistent results across replicates | Technical variability, low reproducibility [38] | Ensure Pearson correlation >0.8 between replicates, increase cell numbers [38] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPRa Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9-Activator Fusions | dCas9-VP64, dCas9-VP160, dCas9-VPR [41] [42] | Programmable DNA binding plus transcriptional activation |

| sgRNA Expression Systems | piggyFlex transposon vector, lentiviral vectors [42] | Stable gRNA expression with selection markers |

| Cell Lines | K562, HEK293T, iPSC-derived excitatory neurons [41] [42] | Validation and screening in relevant cellular contexts |

| Delivery Tools | piggyBac transposase, lentiviral packaging, electroporation [21] [42] | Efficient introduction of CRISPR components |

| Selection Markers | Puromycin resistance, GFP [42] | Enrichment for successfully transfected cells |

| Analysis Tools | MAGeCK, Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) algorithm [38] | Bioinformatics analysis of screening data |

CRISPRa Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

FAQs: Addressing Common dCas9 Screening Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of using dCas9 over CRISPR nuclease (Cas9) in a functional genomics screen?

dCas9 enables reversible gene perturbation without permanently altering the DNA sequence. While CRISPR nuclease (Cas9) creates double-strand breaks to knock out genes, dCas9, when fused to effector domains (CRISPRi or CRISPRa), modulates gene expression—either repressing (interference) or activating it [24] [44]. This is ideal for studying essential genes where knockout would be lethal, for performing time-sensitive studies on gene function, and for investigating phenotypes that require precise, tunable control over transcription levels [45] [46].

FAQ 2: My dCas9 screen shows high variability or weak phenotypic effects. How can I improve the dynamic range of gene modulation?

Weak effects often stem from insufficient dCas9-effactor delivery or expression. To improve dynamic range:

- Titrate dCas9 Expression: Use a tunable promoter system (e.g., arabinose-inducible

P_BAD) to precisely control dCas9 protein levels, which can lead to over 30-fold repression [45]. - Optimize Effector Strength: For activation (CRISPRa), use synergistic effector systems like VPR, SAM, or SunTag, which recruit multiple transcriptional activators for a more robust response [24] [47].

- Validate gRNA Design: Ensure gRNAs target effective genomic regions. For repression, target the template strand near the transcription start site. For activation, target promoter or enhancer regions [48] [44].

FAQ 3: How can I mitigate off-target binding in a dCas9-based screen?

dCas9 binding can occur at sites with imperfect complementarity to the gRNA. To enhance specificity:

- Computational gRNA Design: Use design tools that select gRNAs with minimal off-target potential, requiring maximal mismatches, especially in the PAM-proximal "seed" region [49].

- Use High-Fidelity dCas9 Variants: Consider engineered dCas9 proteins with mutated non-specific DNA-binding domains to reduce off-target interactions [50].

- Titrate Components: Use the lowest effective concentration of dCas9 and gRNA to minimize off-target occupancy while maintaining on-target efficacy [49].

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations for delivering dCas9 systems in high-throughput screens?

Delivery is a major challenge due to the large size of dCas9-effector constructs.

- Lentiviral Vectors: These are the most common method for pooled screens due to their ability to transduce a wide variety of cell types and integrate stably into the genome [44] [51].

- Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV): AAV has a limited packaging capacity (~4.7 kb), which is often too small for standard dCas9-effector fusions. This can be addressed by using smaller Cas orthologs (e.g., from Staphylococcus aureus) or split-intein systems [50].

- Arrayed Format Delivery: For arrayed screens, consider plasmid transfection or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) electroporation for transient, controlled expression [50] [49].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Knockdown or Activation Efficiency

This occurs when the dCas9-effector complex fails to sufficiently repress or activate the target gene.

| Troubleshooting Step | Protocol Detail | Key Reagents/Components |

|---|---|---|

| Verify gRNA Design | Design 3-4 gRNAs per gene target. Use algorithms to select gRNAs targeting near the transcription start site (for CRISPRi) or promoter/enhancer regions (for CRISPRa). | U6 promoter-driven gRNA expression cassette [44]. |

| Optimize dCas9 Expression | Use a tunable, inducible promoter (e.g., P_BAD, tetracycline-responsive) to control dCas9 levels. Titrate the inducer (e.g., arabinose) for optimal efficiency and minimal toxicity. |

Arabinose, Doxycycline [45]. |

| Enhance Effector Potency | For CRISPRa, switch from a single activator (e.g., dCas9-VP64) to a multi-activator system (e.g., dCas9-VPR, SunTag, or SAM). | dCas9-VPR, scFv-antibody fusions for SunTag [24] [47]. |

| Validate gRNA Efficacy | Test individual gRNAs in a small-scale pilot experiment using RT-qPCR to measure mRNA changes. | RT-qPCR reagents, primers for target gene. |

Problem: High Off-Target Effects

Unspecific binding leads to false-positive or false-negative hits in the screen.

| Troubleshooting Step | Protocol Detail | Key Reagents/Components |

|---|---|---|

| Improve gRNA Specificity | Design gRNAs with a >2 base pair mismatch to any other genomic site, particularly in the PAM-proximal seed sequence (first 12 nucleotides). | Bioinformatics tools for off-target prediction [49]. |

| Utilize High-Fidelity dCas9 | Replace standard dCas9 with a high-fidelity variant (e.g., dCas9-HF1) that has mutations reducing non-specific DNA binding. | High-fidelity dCas9 plasmid [50]. |

| Employ a "Two-Step" Nickase | Use a Cas9 nickase (mutated in one nuclease domain) that requires two adjacent gRNAs to bind for functional activity, dramatically increasing specificity. | D10A or H840A Cas9 nickase [49] [46]. |

| Reduce Component Concentration | Titrate down the amount of dCas9 and gRNA delivered (e.g., lower viral titer for transduction) to find a level that minimizes off-targets while retaining on-target activity. | Lentiviral particles, transfection reagents. |

Problem: Poor Delivery or Cell Toxicity

Cells show low viability post-transduction/transfection, reducing screen coverage and quality.

| Troubleshooting Step | Protocol Detail | Key Reagents/Components |

|---|---|---|

| Optimize Viral Titer | Perform a kill curve to determine the minimum viral titer needed for high infection efficiency without causing cell death. | Lentiviral gRNA library, selection antibiotic (e.g., Puromycin) [51]. |

| Switch Delivery Method | For sensitive cells (e.g., primary cells, stem cells), use electroporation to deliver pre-assembled dCas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for fast, transient activity. | dCas9 protein, synthetic gRNA, electroporation system [50] [49]. |

| Use Inducible Systems | Express dCas9 from an inducible promoter to limit prolonged dCas9 expression, which can be toxic to cells. | Doxycycline-inducible dCas9 cell line [45]. |

| Employ Compact Systems | If using AAV, utilize smaller Cas proteins (e.g., dCas12a) or split dCas9 systems to fit within the viral packaging limit. | AAV vector, dCas12a ortholog [50]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key metrics for dCas9 systems from published studies, providing benchmarks for expected performance in high-throughput screens.

Table: Performance Metrics of dCas9 Systems in Functional Genomics

| System Type | Reported Dynamic Range | Key Applications in Screening | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPRi (dCas9 repressor) | Up to 30-fold repression for essential genes [45]. | Identification of essential genes, synthetic lethal interactions, and validation of drug targets [44]. | Highly specific, reversible, minimal off-target effects compared to RNAi [44]. |