High-Throughput Protein Crystallization Screens: A Modern Guide for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

This article provides a comprehensive guide to high-throughput protein crystallization, a critical technology for determining 3D protein structures in structural biology and rational drug design.

High-Throughput Protein Crystallization Screens: A Modern Guide for Accelerated Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to high-throughput protein crystallization, a critical technology for determining 3D protein structures in structural biology and rational drug design. It covers the foundational principles of crystallization and explores the automated platforms, reagents, and robotic systems that enable the rapid screening of thousands of conditions. The content details advanced optimization strategies for challenging targets like membrane proteins and synthesizes the latest trends, including the integration of AI for condition prediction and automated image analysis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a strategic resource for implementing and optimizing efficient crystallization pipelines to accelerate biomedical research.

The Foundation of High-Throughput Crystallography: From Basic Principles to Market Drivers

Defining High-Throughput Protein Crystallization and Its Role in Structural Biology

High-Throughput Protein Crystallization (HTPC) is an automated, industrialized approach to crystallizing biological macromolecules. It leverages robotics, miniaturization, and parallel processing to rapidly set up and analyze thousands of crystallization trials simultaneously [1] [2]. This methodology was largely driven by the demands of structural genomics initiatives, such as the Protein Structure Initiative (PSI), which aimed to determine protein structures on a large scale [2] [3]. The primary goal of HTPC is to overcome the major bottleneck in macromolecular X-ray crystallography—obtaining diffraction-quality crystals—thereby accelerating structure-based drug design and fundamental biological research [1] [4].

Key Principles and Workflow

The underlying principle of HTPC is the statistical sampling of a multidimensional parameter space to identify initial "hit" conditions conducive to crystallization [2] [5]. Key parameters include the protein sample itself, precipitant type and concentration, pH, buffer species, temperature, and additives [6] [7]. Given the impracticality of exhaustive screening, HTPC employs strategically designed screens to efficiently probe this vast chemical landscape [5].

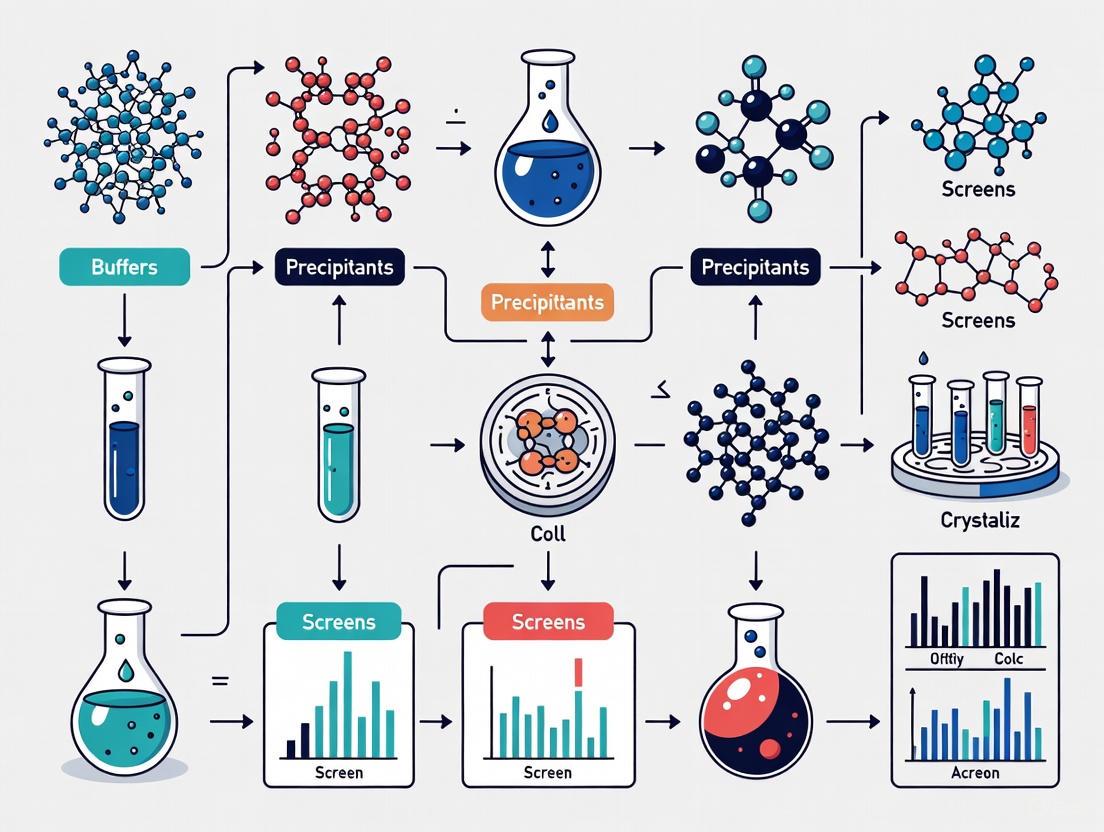

The following workflow diagram outlines the core stages of a high-throughput crystallization pipeline, from initial sample preparation to final structure determination.

- Sample Quality Control: The process begins with a purified protein sample. A critical prerequisite is ensuring the protein is homogeneous, monodisperse, and structurally intact, as sample purity is a major determinant of success [1] [2].

- Automated Screen Building: Liquid handling robots, such as the Formulator, are used to rapidly and precisely prepare crystallization screening solutions (cocktails) from a library of chemical stocks [8].

- Automated Trial Setup: Robotic systems like the NT8 Drop Setter dispense nanoliter-volume droplets of protein and screening solution, typically in sitting-drop, hanging-drop, or microbatch-under-oil formats [1] [8] [3]. This miniaturization allows thousands of trials to be performed with minimal protein consumption.

- Incubation & Automated Imaging: Plates are incubated under controlled temperature conditions and monitored by automated imaging systems (e.g., Rock Imagers) over days or weeks [8] [3].

- Image Analysis & AI Scoring: Advanced software and machine learning models (e.g., Sherlock) analyze the millions of images generated to classify outcomes and identify promising crystalline hits [8].

- Hit Identification & Optimization: Initial hits are used as starting points for optimization screens to produce larger, well-ordered crystals suitable for diffraction studies [6].

- X-ray Diffraction & Structure Determination: Optimized crystals are used for X-ray diffraction data collection, typically at synchrotron facilities, leading to three-dimensional structure determination [1] [3].

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Common Crystallization Techniques in HTPC

HTPC pipelines adapt common crystallization methods for automation and miniaturization. The table below compares the primary techniques used.

Table 1: Comparison of High-Throughput Crystallization Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Throughput & Automation | Protein Consumption | Key Applications in HTPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor Diffusion (Sitting/Hanging Drop) | Droplet containing protein and precipitant equilibrates via vapor phase against a larger reservoir solution [7]. | High; easily automated [6] [8]. | Small (nL-μL volumes) [1]. | Most widely used method for initial screening of soluble proteins [6] [7]. |

| Microbatch-under-Oil | A small batch droplet of protein and precipitant mixture is dispensed under an inert oil to prevent evaporation [6] [3]. | High; amenable to automation in 1536-well formats [3]. | Very small (nL volumes) [3]. | Used in large-scale screening centers (e.g., Hauptman-Woodward HTX Center); conditions are well-defined at setup [3]. |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Protein is embedded in a lipidic mesophase, particularly suitable for membrane proteins [6]. | Possible with specialized robots [8]. | Small to Large [8]. | Crystallization of membrane proteins and GPCRs [6] [8]. |

| Free-Interface Diffusion | Protein and precipitant solutions diffuse into one another at a narrow interface within a capillary or microchannel [7]. | Difficult to automate [8]. | Very Small [8]. | Occasionally used for generating initial leads for difficult targets [7]. |

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening via Microbatch-under-Oil

This protocol is based on the established pipeline at the National High-Throughput Crystallization Center (HTX Center) [3].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Protein Sample: Purified, concentrated, and in a low-salt buffer. Goal: >150 μL at ≥ 5 mg/mL.

- Screening Solutions: Pre-configured 1536-condition screens for soluble or membrane proteins [3].

- Platform: 1536-well microassay plate.

- Sealing Agent: High-viscosity paraffin oil.

- Equipment: Automated liquid handling robots, automated imager.

II. Procedure

- Plate Preparation: Using a liquid-handling robot, dispense ~200 nL of each crystallization screening condition into the wells of a 1536-well microassay plate [3].

- Protein Dispensing: Dispense ~200 nL of the protein sample into each well, creating a microbatch droplet with the screening solution [3].

- Sealing: Immediately cover the entire plate with a layer of high-viscosity paraffin oil to prevent droplet evaporation [3].

- Incubation and Imaging:

- Seal the plate and incubate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 23°C or 14°C).

- Place the plate in an automated imaging system.

- Acquire images of all wells according to a predefined schedule (e.g., days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42) [3].

- Analysis: Use integrated software and AI-based autoscoring models to analyze the image dataset for the presence of crystals, precipitate, or other phase changes [8].

Protocol: Optimization from Initial Hits

Once a hit is identified, systematic optimization is crucial.

- Fine-Screening: Set up a fine-grid screen around the initial hit condition. Variations typically include:

- Precipitant Concentration: A gradient above and below the hit concentration.

- pH: A narrow pH range (e.g., ± 0.5 pH units) from the hit condition.

- Temperature: Replicate trials at multiple temperatures (e.g., 4°C, 20°C).

- Additives: Include small molecules, ions, or ligands that may enhance crystal order [6].

- Seeding: If crystals are numerous but small, use seeding techniques to transfer microscopic crystal fragments into new, slightly less saturated pre-equilibrated drops to promote larger crystal growth [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for HTPC

| Item | Function in HTPC | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse-Matrix Screens | Pre-mixed solutions that randomly sample crystallization chemical space based on historical success [6] [5]. | Hampton Research Crystal Screens, Molecular Dimensions JCSG+ screens. |

| Grid Screen Reagents | Individual stock solutions of precipitants (e.g., PEGs, salts), buffers, and additives for designing customized screens [5]. | Used with automated screen builders like the Formulator [8]. |

| Crystallization Plates | Microplates with wells designed for nanoliter-volume sitting or hanging drops, or microbatch experiments. | 96-well, 384-well, and 1536-well formats [1] [3]. |

| Paraffin Oil | An inert, high-viscosity oil used in microbatch-under-oil experiments to prevent evaporation of nanoliter droplets [3]. | Critical for the microbatch protocol at the HTX Center [3]. |

| Detergents | Essential for solubilizing and crystallizing membrane proteins by mimicking the lipid bilayer environment. | Included in specialized membrane protein screens (e.g., MembFac) [6] [3]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) added to crystals prior to flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen to prevent ice formation during X-ray data collection. | A standard consumable in downstream processing [9]. |

Quantitative Outcomes and Success Rates

The efficiency of HTPC is demonstrated by its scale and success metrics from operational centers.

Table 3: Quantitative Outcomes from High-Throughput Crystallization Screening

| Metric | Value | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Screening Throughput | 40,000 experiments per day | Early automated system reported by [1]. |

| Drop Volume | 20 - 100 nL | Standard for nanodroplet HTPC robots [1]. |

| Standard Screen Size | 1,536 conditions | Standard screen size at the HTX Center [3]. |

| Crystal Hit Rate | 27% - 52% | Range of success rates for different PSI consortia at the HTX Center [3]. |

| Structure Determination Rate | 21% - 23.1% | Percentage of samples leading to a deposited PDB structure after optimization at the HTX Center [3]. |

| Total Samples Screened | >18,000 | Cumulative samples processed by the HTX Center over 20+ years [3]. |

HTPC has become a cornerstone of modern structure-based drug design [2] [4]. Its ability to rapidly determine the structures of protein-target complexes enables:

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): Screening small, low-molecular-weight fragments that bind to a target, with HTPC providing structural information to guide their optimization into lead compounds [4].

- Lead Optimization: Providing atomic-level details of drug-target interactions, allowing medicinal chemists to rationally improve the potency and selectivity of drug candidates [2] [4].

In conclusion, High-Throughput Protein Crystallization has transformed crystallography from a specialized art into an industrialized, data-rich science. By integrating automation, miniaturization, and informatics, HTPC has significantly accelerated the pace of structural biology, providing indispensable insights for understanding biological mechanisms and developing new therapeutics.

The global protein crystallization market is demonstrating robust growth, propelled by its critical role in structural biology and drug discovery. The market is poised to expand from $1.62 billion in 2024 to $2.8 billion by 2029, reflecting a strong Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 11.5% [9] [10]. This trajectory is supported by rising R&D investments and an increasing focus on protein-based therapeutics.

Table 1: Global Protein Crystallization Market Financial Projection

| Metric | 2024 Value | 2029 Projection | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size | $1.62 Billion [9] [10] | $2.8 Billion [9] [10] | 11.5% [9] |

Market Segmentation Analysis

Growth is pervasive across all market segments, with specific areas showing accelerated adoption driven by technological advancements.

Table 2: Protein Crystallization Market Size and Growth by Segment

| Segmentation | Dominant Segment (2024) | Fastest-Growing Segment | Key Growth Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Consumables [11] [12] [13] | Software & Services (12.19% CAGR) [14] | High-throughput screening demands and AI-driven data analysis [14]. |

| Technology | X-ray Crystallography [14] [13] | Microfluidic Chip-Based Screening (11.73% CAGR) [14] | Miniaturization, reduced sample volume, and faster results [14]. |

| End User | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies [14] | Contract Research Organizations (CROs) (10.24% CAGR) [14] | Outsourcing of specialized crystallization workflows [14]. |

| Region | North America (36.13% share) [14] | Asia-Pacific (10.05% CAGR) [14] | Strong R&D infrastructure and major biopharma presence [11]; rising investments and pharmaceutical expansion [13]. |

Key Growth Factors: An Analytical Framework for High-Throughput Research

The market's expansion is underpinned by several interconnected factors that directly influence high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies.

Primary Market Drivers

- Escalating Demand for Biopharmaceuticals: The shift towards targeted protein therapeutics, including monoclonal antibodies and engineered enzymes, requires atomic-level structural information for rational drug design. Protein crystallization is indispensable for providing this structural insight, refining targeted therapies for better efficacy and stability [10] [14].

- Increased R&D Investment: Significant funding from both public and private sectors is accelerating structural biology research. For instance, the Australian government invested $4.34 billion in R&D in 2022-23, a substantial increase from previous years [9] [10]. Such investments legitimize capital expenditures on advanced crystallization platforms [14].

- Technological Convergence and Automation: The integration of automation, robotics, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming traditional workflows. AI algorithms predict optimal crystallization conditions, while robotic liquid handling systems enable high-throughput screening of thousands of conditions, drastically improving efficiency and success rates [9] [14] [15].

Pivotal Market Trends

- Miniaturization via Microfluidics: Microfluidic devices and lab-on-a-chip technologies are revolutionizing HTS by allowing experiments with nanoliter-volume samples. This reduces reagent consumption and protein sample requirements, which is particularly valuable for studying difficult-to-express proteins [14] [16].

- Adoption of Hybrid Structural Biology Techniques: Cryo-electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) is increasingly used alongside traditional X-ray crystallography. Cryo-EM provides high-resolution structural information for proteins that are challenging to crystallize, creating complementary workflows in drug discovery pipelines [11] [14].

- Innovative Crystallization Methods: Novel techniques like cell-free protein crystallization, developed by the Tokyo Institute of Technology, enable the study of unstable proteins that are intractable with conventional methods, opening new frontiers in structural biology [9] [10].

Application Notes: High-Throughput Screening Protocol for Membrane Proteins

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for high-throughput crystallization screening of challenging targets like membrane proteins, incorporating contemporary technologies and reagents.

Experimental Workflow: High-Throughput Crystallization Screening

The diagram below outlines the key stages of a modern, high-throughput crystallization screening workflow.

Protocol Steps

Protein Sample Preparation

- Aim: Obtain a pure, monodisperse, and concentrated protein sample.

- Procedure:

- Purify the target membrane protein using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography in a suitable detergent.

- Use analytical size-exclusion chromatography to confirm monodispersity.

- Concentrate the protein to ≥ 40 mg/mL in a compatible buffer using centrifugal concentrators.

- Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove any aggregates immediately before setting up crystallization trials.

Primary High-Throughput Screening

- Aim: Identify initial crystallization "hits" from a broad spectrum of conditions.

- Procedure:

- Use an automated liquid handling robot (e.g., Mosquito LCP or Dragonfly).

- Dispense 150-200 nL of protein solution per well in a 96-well sitting-drop crystallization plate.

- For membrane proteins, consider using the Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) method with the same robot.

- Dispense 100 nL of a commercial sparse matrix screen (e.g., MemGold1/2, MemMeso) as the precipitant solution.

- Seal the plate with a transparent tape and incubate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 20°C).

Automated Imaging and Crystal Detection

- Aim: Monitor plates and identify crystal formation without manual intervention.

- Procedure:

- Load plates into an automated imaging system (e.g., Formulatrix Rock Imager series).

- Program the imager to scan each well every 6-8 hours for the first 7 days, then daily for up to 90 days.

- Use integrated AI-based image analysis software to automatically score wells and flag potential crystalline hits based on predefined morphological features.

Hit Optimization

- Aim: Refine initial hits to produce large, diffraction-quality crystals.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a fine-screen around the chemical space of the initial hit condition (e.g., varying pH ± 0.5, precipitant concentration ± 20%).

- Employ microseed screening (MSS) to improve crystal size and uniformity.

- Prepare a seed stock by crushing initial microcrystals.

- Add a diluted seed stock to each new crystallization drop to nucleate growth.

Crystal Harvesting and Data Collection

- Aim: Harvest and freeze crystals for high-resolution X-ray diffraction.

- Procedure:

- Harvest optimized crystals using micromount loops (e.g., MiTeGen MicroLoops).

- Cryo-cool crystals by plunging into liquid nitrogen after a brief soak in a cryoprotectant solution.

- Ship crystals to a synchrotron facility under liquid nitrogen for high-brilliance X-ray exposure.

- Collect a complete dataset, typically 180-360 degrees of rotation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful high-throughput crystallization screens rely on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Crystallization

| Item Category | Specific Product Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Plates | Corning Next Generation CrystalEX Microplates [13], Greiner Bio-One 96-well sitting-drop plates | Provide a miniaturized platform for setting up thousands of vapor-diffusion trials with nanoliter volumes. |

| Sparse Matrix Screens | Hampton Research Index, Jena Bioscience JBScreen, Molecular Dimensions MemGold/MemMeso | Pre-formulated suites of conditions that sample a diverse chemical space (precipitants, salts, buffers, additives) to identify initial crystallization hits. |

| Liquid Handling Instruments | SPT Labtech mosquito, TTP Labtech dragonfly | Automated robots capable of precisely dispensing nanoliter volumes of protein and precipitant, enabling high-throughput, reproducible plate setup. |

| Automated Imaging Systems | Formulatrix Rock Imager 8S [12] | High-throughput microscopes that automatically image crystallization drops at scheduled intervals, allowing for kinetic monitoring of crystal growth. |

| AI-Powered Analysis Software | ROCK MAKER (Formulatrix) [13], AI-based crystal detection algorithms [9] | Software that uses machine learning to analyze images from imaging systems, automatically identifying and scoring potential crystals based on morphology. |

The protein crystallization market's trajectory toward $2.8 billion by 2029 is intrinsically linked to technological advancements that address the core challenges of high-throughput screening. The integration of automation, miniaturization, and artificial intelligence is creating a new paradigm where obtaining structural information is faster, more efficient, and more accessible. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging the protocols, tools, and insights outlined in these application notes is crucial for staying at the forefront of structural biology and accelerating the development of next-generation therapeutics.

Building a Modern HT Crystallization Pipeline: Automation, Reagents, and Techniques

Within structural biology and rational drug design, determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins is paramount for understanding function and guiding the development of therapeutic molecules. X-ray crystallography, the predominant method for structure determination, requires high-quality, well-ordered single crystals [17]. The production of these crystals often represents the most significant bottleneck in the entire pipeline [6] [17]. Protein crystallization is a complex multiparametric process, and finding initial "hit" conditions has been compared to searching for a "needle in a haystack" [6].

The advent of high-throughput methodologies has dramatically accelerated the process of crystallization screening, cutting the setup and analysis time from weeks to minutes and enabling the testing of thousands of conditions [6]. Among the plethora of techniques developed, vapor diffusion, microbatch, and lipid cubic phase (LCP) crystallization have emerged as critical methods. Vapor diffusion remains the most widely used technique, while LCP has revolutionized the crystallization of membrane proteins, a class of targets constituting over 60% of modern drugs [18]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these three pivotal methods, offering structured data and actionable protocols to support researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal crystallization strategy for their specific projects.

Theoretical Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Crystallization Thermodynamics

All protein crystallization methods share a common goal: to gently drive a purified protein solution into a state of supersaturation, which is the thermodynamic driving force for nucleation and subsequent crystal growth [19] [17] [20]. A typical protein phase diagram can be divided into regions of undersaturation, metastability, and labile (supersaturated) zones [19]. The optimal path navigates through a narrow window of supersaturation that is high enough to promote nucleation but low enough to avoid amorphous precipitation [19]. The different methods achieve this supersaturation through distinct physical mechanisms, which directly influence their success rates, crystal quality, and applicability.

Method Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of vapor diffusion, microbatch, and LCP crystallization.

| Feature | Vapor Diffusion | Microbatch | Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Equilibration of a droplet against a reservoir via vapor phase, concentrating the sample [17] [21]. | Direct mixing of protein and precipitant under oil, preventing evaporation [17]. | Crystallization within a lipidic mesophase that mimics the native membrane environment [18]. |

| Typely Protein Consumption | Small to Large (e.g., 2-4 μL drops) [8] | Small (e.g., 0.5-1 μL drops) [22] | Small to Large [8] |

| Throughput & Automation | High; easily automated with liquid handlers [8] [6]. | High; suitable for robotics (e.g., IMPAX machine) [22]. | Possible; specialized robots required [8]. |

| Speed of Nucleation | Relatively fast; conditions change dynamically [22]. | Variable; can be immediate or slow, depending on formulation [22]. | Typically slower; occurs within the mesophase matrix [18]. |

| Control Over Supersaturation | High, through reservoir composition and drop ratio [21]. | Fixed at setup; can be modified with oil mixtures for evaporation [22] [23]. | High, but complex; depends on lipid composition and precipitant diffusion [18]. |

| Crystal Quality & Size | Can produce large crystals; quality can be excellent [17]. | Crystals may be smaller than in VD under the same condition [22]. | Often produces high-quality, well-ordered crystals for membrane proteins [18]. |

| Seeding & Handling | Possible and relatively straightforward [8]. | Not possible in traditional setup [8]. | Possible, though harvesting can be difficult [8]. |

| Ideal Application | Broad-purpose, initial screening, and optimization [8] [21]. | Rapid screening, low protein availability, and specific optimization [22] [23]. | Membrane proteins, integral membrane proteins [8] [18]. |

| Key Challenges | Sensitive to environmental fluctuations, longer equilibration times [20]. | Wide crystal size distribution possible, less dynamic control [20]. | Technically challenging, harvesting can be difficult, limited to specific protein types [8] [18]. |

Quantitative Performance Insights

A comparative study screening six proteins with sparse matrix conditions found that a combination of three microbatch variants identified 43 out of 58 total conditions (74%), while a single vapor diffusion screen identified 41 conditions (71%) [22]. Critically, each method discovered unique hits: approximately 29% of conditions would have been missed if microbatch had not been employed alongside vapor diffusion [22]. Furthermore, vapor diffusion typically produces crystals more quickly in the initial weeks, whereas microbatch (particularly an evaporation variant) continues to produce new conditions over longer durations, eventually matching vapor diffusion's total yield [22].

Experimental Protocols

Vapor Diffusion Protocol (Sitting Drop)

Principle: A droplet containing a mixture of protein and precipitant is sealed in a chamber with a pure precipitant reservoir. Water vapor diffuses from the drop to the reservoir, slowly concentrating the protein and precipitant until equilibrium is achieved, ideally crossing the supersaturation threshold for nucleation [17] [21].

Materials:

- Purified, concentrated protein (>99% pure, typically 5-50 mg/mL) [17] [21]

- 24-well sitting drop tray (e.g., from Hampton Research)

- Reservoir solutions (e.g., commercial sparse matrix screens)

- Optically clear sealing tape

- Low-retention pipette tips (0.1-2 μL)

- Siliconized glass cover slides (for hanging drop variant)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Filter all stock solutions using a 0.22 μm filter. Centrifuge the protein sample (e.g., 15 min at 18,000 x g, 4°C) to remove any aggregates [17].

- Reservoir Setup: Pipette 500 μL of precipitant reservoir solution into each well of the crystallization tray [17].

- Drop Dispensing: On the raised shelf of the sitting drop well, combine 1 μL of protein solution with 1 μL of reservoir solution. Mix carefully by pipetting, avoiding bubble formation [17].

- Sealing: Use optically clear sealing tape to securely cover the entire tray, ensuring a complete vapor-tight seal for each well.

- Incubation: Place the tray gently on a stable, vibration-damped surface in a temperature-controlled incubator (commonly 4°C or 20°C). Avoid disturbances [17].

- Monitoring: Check the drops for crystal formation the following day, and then regularly every few days using a microscope. Document all outcomes [17].

Microbatch Crystallization Protocol

Principle: Protein and precipitant solutions are directly mixed in a single step and dispensed under an oil layer, which prevents evaporation and fixes the crystallization condition from the outset [17]. A modified version uses a specific oil mixture to allow slow water evaporation, mimicking vapor diffusion [22] [23].

Materials:

- Purified, concentrated protein

- 96-well microbatch tray (e.g., Nunc HLA plates)

- Paraffin oil (e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich)

- Silicone oil (for evaporation method)

- Liquid handling robot (e.g., Douglas Instruments IMPAX) or manual pipettes with fine tips

Procedure:

- Tray Preparation: Clean the microbatch tray with compressed air to remove dust. Fill the wells with paraffin oil to a depth of approximately 3 mm [17].

- Droplet Formation (Under Oil):

- For standard microbatch: Pipette 1 μL of protein solution directly to the bottom of an oil-filled well. Add 1 μL of precipitant solution to the same well, ensuring the droplets sink and fuse at the bottom [17].

- For evaporation-controlled microbatch: Use a 50:50 mixture of paraffin and silicone oil. The silicone oil permeability allows slow water evaporation, gradually increasing concentration over time [22].

- Incubation and Monitoring: Seal the plate (if necessary) and incubate as described for vapor diffusion. Monitor regularly for crystal growth [22].

Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) Crystallization Protocol

Principle: The membrane protein is reconstituted into a lipidic cubic mesophase, a semi-solid matrix of continuous lipid bilayers. Precipitant solution is then introduced, often in the form of an LCP "bolus" covered by a precipitant solution, and crystals grow within the lipid bilayer environment [18].

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein in a suitable detergent

- Lipids for mesophase formation (e.g., Monoolein)

- Precipitant solutions

- Syringe mixing setup (two gastight syringes connected by a coupler)

- LCP crystallization plates (e.g., 96-well glass sandwich plates)

Procedure:

- Mesophase Preparation: Mix Monoolein and the membrane protein solution (typically at a 60:40, w:w ratio) using two syringes connected by a coupler. Push the plungers back and forth repeatedly until the mixture forms a clear, viscous mesophase [18].

- Bolus Dispensing: Using a syringe, dispense 50-100 nL boluses of the protein-laden mesophase onto the well of an LCP crystallization plate.

- Precipitant Overlay: Carefully overlay each mesophase bolus with 1 μL of precipitant solution.

- Sealing and Incubation: Seal the plate with a glass cover slide and incubate. Crystals typically grow within the mesophase and can be detected as birefringent objects under a microscope [18].

- Harvesting: Harvesting crystals from LCP is complex and often involves using special MicroMounts (e.g., MiTeGen MicroLoops) to scoop out the entire bolus.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Suppliers/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Reduce protein solubility to induce supersaturation. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and ammonium sulfate are the most common, accounting for ~60% of successful conditions [17] [20]. | Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions |

| Sparse Matrix Screens | Pre-formulated screening solutions based on historical crystallization data, allowing efficient exploration of chemical space [6] [17]. | Crystal Screen (Hampton Research), JCSG Core (Molecular Dimensions) |

| Crystallization Plates | Specialized plates with wells for reservoir solutions and platforms for drop deposition. | 24-well Vapor Diffusion Plates, 96-well Sitting Drop Plates, LCP Glass Sandwich Plates |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automate the dispensing of nanoliter-volume drops, ensuring precision, reproducibility, and high throughput [8] [6]. | NT8 Drop Setter (Formulatrix), IMPAX (Douglas Instruments) |

| Lipids for LCP | Form the bicontinuous cubic phase matrix that hosts membrane proteins. Monoolein is a standard lipid used [18]. | Nu-Chek Prep |

| Automated Imaging Systems | Capture high-quality images of crystallization drops over time for remote monitoring and analysis [8]. | Rock Imager series (Formulatrix) |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software to manage the entire crystallization workflow, from plate setup and tracking to image analysis and data management [8]. | Rock Maker (Formulatrix) |

Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate crystallization method based on key project parameters.

The strategic selection of a crystallization method is a critical determinant of success in high-throughput structural biology pipelines. As demonstrated, vapor diffusion, microbatch, and LCP are not mutually exclusive but are complementary tools, each with distinct strengths. Vapor diffusion offers dynamic control and is the workhorse for soluble proteins. Microbatch conserves precious sample and can uncover unique conditions. LCP is indispensable for tackling the challenging landscape of membrane protein structural biology. The integration of these methods, guided by rational decision-making and supported by automation and sophisticated data management, provides a powerful framework for advancing research in structural biology and drug development. Future directions will likely involve greater integration of machine learning for predictive modeling and condition optimization, further enhancing the efficiency and success of protein crystallization endeavors [8].

In the field of structural biology and rational drug discovery, high-throughput protein crystallography has become an indispensable technology for determining the three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules [2]. The process of obtaining diffraction-quality crystals remains a significant bottleneck, compounded by the fact that crystallization conditions for novel samples cannot be predicted [24]. Automated workflows address this challenge by enabling the rapid, reproducible, and systematic screening of thousands of crystallization conditions while conserving precious protein samples [25] [26]. This application note details integrated protocols for automating the key stages of protein crystallization: screen building, drop setting, and automated imaging, providing a framework for laboratories aiming to implement or enhance high-throughput structural biology pipelines.

The Integrated Automated Workflow

The transition from manual to automated crystallization involves the seamless integration of specialized instrumentation, software, and standardized protocols. The entire process, from designing the experiment to analyzing the results, can be managed within a unified system. The workflow below illustrates the core pathway and the technologies involved at each stage.

Equipment and Reagent Solutions

A robust automated crystallization platform relies on integrated hardware and software components. The table below summarizes key solutions for establishing this workflow.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Instrumentation for Automated Protein Crystallization

| Category | Product/System Name | Key Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Rock Maker [25] [8] | Manages the entire experimentation process, from experimental design and dispense to image viewing and analysis. | Integrates with screen builders, drop setters, and imagers; provides tools for AI-based autoscoring. |

| Screen Builder | Formulator Screen Builder [25] [8] | Prepares crystallization screening solutions by dispensing up to 34 different ingredients. | Uses a 96-nozzle dispensing chip; volumes from 200 nL; no consumables required. |

| Drop Setter / Crystallization Robot | NT8 Drop Setter [25] [8] | Sets up crystallization experiments (hanging/sitting drop, LCP, etc.) by combining protein and screen solutions. | 8-tip head; dispenses drops from 10 nL to 1.5 μL; features active humidification and reusable tips. |

| Automated Imager | Rock Imager Series [25] [8] | Automated imaging system for crystallization plates with various capacities and advanced imaging modalities. | Models available with capacities from 1 to 1000 plates; imaging options include Visible, UV, MFI, and SONICC. |

| Alternative Liquid Handler | Opentrons-2 [27] | An economical and versatile liquid handling robot for automating crystallization plate setup, controlled via Python. | Accessible platform for mixing and setting up 24-well sitting drop vapor diffusion trials. |

Detailed Protocols

Protocol 1: Fully Automated Preparation of Crystallization Screening Plates

This protocol describes the creation of a large stock of pre-dispensed screening plates (e.g., "LMB plates") for use in initial crystallization trials [24]. This system integrates a liquid handler, an automated carousel, an inkjet printer, and an adhesive plate sealer.

Materials:

- Formulatrix Formulator Screen Builder or equivalent [25]

- Commercially available screening kit solutions

- SBS-standard 96-well crystallization plates

- Adhesive sealing films

- Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS)

Procedure:

- System Initialization: Ensure the liquid handler and plate sealer are initialized and software is running. Activate the tube-cooling carrier chiller 30 minutes prior to start [24].

- Plate Sealer Test: Place a test plate on the sealer carrier and run the sealing process three times to verify the film is applied correctly [24].

- Liquid Handler Priming: Fill the main container of the liquid handler with deionized water and connect the fluidic coupling. Enter the screen name on the inkjet printer and initiate carousel rotation [24].

- Plate and Reagent Loading:

- Liquid Handler Flushing: Run a maintenance flush program to prime the system and wash the dispensing tips [24].

- Plate Dispensing, Labeling, and Sealing:

- Execute the "MRC kit dispensing" program. The system will automatically [24]:

- Transfer 80 µL of each screening condition from the source tubes to the reservoir wells of the crystallization plates.

- Inkjet-print a unique identifier on each plate.

- Apply an adhesive seal to each finished plate.

- Execute the "MRC kit dispensing" program. The system will automatically [24]:

- System Shutdown and Plate Storage: After all plates are processed, switch the liquid handler to an ethanol rinsing solution and run a flush program. Turn off the chiller. Store the successfully prepared plates at a constant temperature (e.g., 10°C) [24].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Crystallization Setup Using a Drop Setter

This protocol utilizes a dedicated crystallization robot to set up 1,920 initial screening conditions for a single protein sample across twenty 96-well plates via sitting drop vapor diffusion [24].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample (> 2 mg/mL concentration) [24] [2]

- Pre-dispensed screening plates (from Protocol 1)

- NT8 Drop Setter or equivalent nanoliter dispenser [25] [8]

- SBS-standard sitting drop crystallization plates (if not using pre-dispensed ones)

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Power on and initialize the nanoliter dispenser and liquid handler. Activate the microtube-cooling carrier 15 minutes beforehand. Test the plate sealer and the nanoliter dispenser's droplet formation using a test solution [24].

- Plate Loading: Insert the first pre-dispensed screening plate into the custom plate holder on the deck and remove its adhesive seal. Place the plate on the deck's sliding carrier [24].

- Sample Loading: Centrifuge the purified protein sample briefly and place it in the cooling carrier on the deck.

- Automated Drop Setting:

- The liquid handler and nanoliter dispenser work in concert to [24] [8]:

- Combine 100 nL of the protein sample with 100 nL of the crystallization condition from the reservoir.

- Dispense this 200 nL mixed droplet onto the sitting drop post or shelf.

- This process is repeated for all 96 wells of the plate.

- The liquid handler and nanoliter dispenser work in concert to [24] [8]:

- Plate Sealing and Storage: Once all droplets are set, the robotic system automatically applies a transparent adhesive seal to the plate. The plate is then transferred to a temperature-controlled incubator or storage hotel [24].

- Process Repetition: The system proceeds to set up the remaining 19 plates automatically, creating a total of 1,920 individual crystallization trials for the sample [24].

Protocol 3: Automated Imaging and Hit Detection

This protocol covers the automated monitoring of crystallization trials and identification of crystal hits using advanced imaging technologies.

Materials:

Procedure:

- Plate Scheduling: Within the LIMS (e.g., Rock Maker), define an imaging schedule for the batch of crystallization plates. Specify the frequency of imaging (e.g., daily for the first week, weekly thereafter) and the imaging modalities to be used [26].

- Automated Plate Retrieval and Imaging: The automated imager, potentially integrated with a plate hotel, will [25] [28]:

- Retrieve plates from storage according to the schedule.

- Position each well under the optics automatically.

- Capture images using pre-defined modalities (see Table 2).

- Return the plate to its storage location.

- Image Analysis:

- Manual Review: Acquired images are stored in a central database. Users can remotely view and score the experiments for crystal growth, precipitation, or phase separation [26].

- AI-Assisted Scoring: Utilize integrated AI autoscoring models (e.g., MARCO or Sherlock) to pre-analyze the images. These models can highlight potential hits, significantly reducing the time required for manual inspection [8].

Table 2: Imaging Modalities for Crystal Hit Identification

| Imaging Modality | Principle | Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible Light [8] | Bright-field, dark-field, or phase-contrast microscopy using visible spectrum light. | General monitoring of crystal growth and drop morphology. | Suitable for analyzing large, well-formed crystals. |

| Ultraviolet (UV) [8] [28] | Excitation of intrinsic fluorescence from aromatic amino acids (e.g., Tryptophan). | Distinguishing protein crystals from salt crystals. | Label-free method for confirming the proteinaceous nature of a crystal. |

| Second Order Nonlinear Imaging of Chiral Crystals (SONICC) [25] [8] | Combines Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) and UV-TPEF. | Detecting microcrystals (<1 μm) and crystals obscured in precipitate or LCP. | High sensitivity and ability to definitively identify protein crystals. |

| Multi-Fluorescence Imaging (MFI) [8] [28] | Detection of fluorescence from covalently attached fluorophores (Trace Fluorescent Labeling). | Identifying protein crystals in complex mixtures and distinguishing them from salt. | High sensitivity, especially when intrinsic protein fluorescence is weak. |

The implementation of a fully automated workflow from screen building to automated imaging represents a paradigm shift in macromolecular crystallography. It directly addresses the critical bottlenecks of precision, reproducibility, and throughput that challenge crystallography laboratories [29] [26]. By standardizing liquid dispensing with nanoliter accuracy, these systems drastically reduce consumption of valuable protein samples, allowing for more extensive screening of chemical space [2] [26]. Furthermore, integration with a LIMS ensures rigorous tracking of experimental parameters, enabling data-driven optimization and enhancing the overall reliability of the structural pipeline.

While high-throughput approaches are powerful, they do not replace the need for expert analysis. The success of these automated systems ultimately relies on skilled researchers to interpret results, particularly complex crystallization outcomes, and to design intelligent optimization strategies based on the initial screening data [2]. The protocols outlined herein provide a foundation for laboratories to achieve a high level of automation, accelerating the path from protein sample to diffraction-quality crystal and, ultimately, to a three-dimensional structure that can inform biological understanding and drug discovery efforts.

Protein crystallization is a critical process in structural biology, forming a regular array of individual protein molecules stabilized by crystal contacts. Understanding protein structure is of great importance for predicting function, studying protein-protein or ligand-protein interactions for drug discovery, and uncovering stages in enzyme catalysis [8]. The process involves gradually reducing the solubility of the protein using precipitants in a controlled environment, but predicting optimal conditions remains challenging due to the complex interplay of interactions between protein molecules [8]. Automation has become the definitive response to overcoming the crystallization bottleneck in biological crystallography, transforming a traditionally slow, resource-intensive, and error-prone process into a streamlined, reproducible, and high-throughput workflow [8] [30]. This application note details the essential tools and methodologies for implementing automated protein crystallization within the context of high-throughput research, providing structured protocols for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The transition to automated platforms addresses several critical limitations of manual methods. Conventional protein crystallization workflows involve working with sub-microliter volumes, where even slight inaccuracies in dispensing or mixing reagents lead to significant errors or suboptimal results [8]. Automation eliminates human error, ensures reproducibility, and dramatically increases throughput by integrating and standardizing all crystallization steps [8]. High-throughput facilities are now capable of setting up thousands of crystallization trials per day, testing multiple constructs of each target on a production-line basis, which has significantly improved success rates and made crystallization much more convenient [30].

Essential Equipment for High-Throughput Crystallization

A complete automated protein crystallization workflow integrates several specialized instruments: liquid handlers for preparing crystallization screens and setting up drops, crystallization robots capable of handling various techniques and sample types, and automated storage imagers for temperature-controlled incubation and visual inspection. The synergy between these components creates a seamless pipeline from experimental design to crystal detection.

Crystallization Robots and Liquid Handlers

Crystallization robots and liquid handlers form the core of automated setup, enabling precise, nanoliter-volume dispensing that conserves precious protein samples. These systems provide the accuracy and reproducibility essential for high-throughput screening.

Table 1: Comparison of Automated Crystallization Robots and Liquid Handlers

| Device Name | Type | Volume Range | Key Features | Supported Methods | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT8 Drop Setter [8] | Liquid Handler (Tip-based) | 10 nL - 1.5 μL | Proportionally-controlled active humidification; reusable tips; 8-tip head | Sitting drop, hanging drop, LCP, microbatch, additives, seeding | Fast nanoliter-volume dispensing |

| Mosquito Crystal [31] | Liquid Handler (Tip-based) | 25 nL - 1.2 μL | "Walk up and use" technology; active humidity chamber; true positive displacement pipetting | Sitting drop, hanging drop, microbatch, seeding, additive screening | 2 minutes per 96-well plate |

| Formulator [8] | Screen Builder (Tipless) | 200 nL - no upper limit | Microfluidic dispenser; 96-nozzle chip; dispenses 34 different ingredients | Creation of crystallization screens | 2.7 minutes for a 96-well grid screen |

| Dragonfly Crystal [32] | Liquid Handler (Non-contact) | 0.5 μL - 4 mL | 10 independent dispensing heads; non-contact; contamination-free | Protein crystallization setup, assay plate preparation | 4-8 minutes per 96-well plate |

Automated Storage and Imaging Systems

After automated setup, crystallization plates require temperature-controlled incubation and regular monitoring. Automated storage imagers combine precise environmental control with advanced imaging capabilities to track crystal growth over time, identifying critical hits among thousands of experiments.

Table 2: Comparison of Automated Storage and Imaging Systems

| System Name/Type | Plate Capacity | Temperature Control | Imaging Modalities | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rock Imager 1000 [8] [33] | 1000 plates | Yes (4°C - 30°C) | Visible, UV, MFI, SONICC | Highest capacity; floor-standing; full imaging options |

| Rock Imager 360 [8] [33] | 364 plates | Yes (4°C - 30°C) | Visible, UV, MFI | Benchtop; browser-based software; compact storage |

| Rock Imager 2 [8] | 2 plates | No | Visible, UV, MFI | Benchtop; Windows-based software |

| Rock Imager 1 [8] | 1 plate | No | Visible, UV | Basic benchtop model |

| SpectroQ UV [34] | Up to 690 SBS plates | Yes (4°C - 20°C) | Ultraviolet, Visible | Patented LED light source; high-resolution imaging |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful high-throughput crystallization screening requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential solutions and their specific functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Automated Crystallization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitant Solutions [8] | Reduce protein solubility to promote crystallization | Hundreds of inorganic and organic compounds are used; systematically combined in screens |

| Crystallization Screens [8] [30] | Pre-formulated condition matrices for initial screening | Commercial screens available; can be custom-built using instruments like the Formulator |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Materials [8] | Matrix for crystallizing membrane proteins | Specialized protocol; requires compatible equipment (e.g., NT8 or Xantus robot) |

| Amine-Reactive Dyes [8] | Fluorescent labeling for Multi-Fluorescence Imaging (MFI) | Used to distinguish protein-protein complexes; choice of dye concentration is critical for stability |

| Buffers and Salts [8] [30] | Control pH and ionic strength of crystallization environment | Critical parameters systematically varied in screening; stock solutions prepared as concentrates |

| Crystallization Plates [33] [31] | Physical platform for experiments | Various formats: SBS, Linbro, Nextal, LCP; must match instrument specifications |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Comprehensive Workflow for High-Throughput Crystallization

The automated protein crystallization process follows a defined multi-step workflow that integrates instrumentation, software, and reagents. The diagram below illustrates this comprehensive pipeline from sample preparation to final analysis.

Protocol 1: Automated Initial Screening Setup

Purpose: To efficiently screen a purified protein sample against a broad matrix of crystallization conditions using automated liquid handling.

Materials:

- Purified protein sample (>95% purity, concentrated)

- Commercial crystallization screen solutions

- Suitable crystallization plates (SBS format)

- NT8 Drop Setter or Mosquito Crystal liquid handler

- Rock Maker software

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: In Rock Maker software, design the screening experiment by selecting the desired commercial screen and plate type. Define the drop ratio (typically 1:1, 2:1, or 3:1 protein:precipitant) and volume (50-200 nL total) [8] [35].

- Plate Preparation: Using the Formulator screen builder or equivalent, dispense crystallization screen solutions into the plate reservoirs according to the selected screen [8].

- Protein Dispensing: Program the liquid handler (NT8 or Mosquito Crystal) to dispense nanoliter volumes of protein and precipitant solutions according to the designed experiment. For sitting drop vapor diffusion, typical drop sizes range from 50 nL to 400 nL [8] [31].

- Sealing and Transfer: Automatically seal the plate and transfer it to the automated storage imager. The entire process from experimental design to plate setup is coordinated through Rock Maker software [35].

Critical Notes: Maintain active humidification during drop setup to prevent evaporation, especially with nanoliter volumes [8] [31]. Include control drops when possible. Protein concentration should be optimized prior to screening (typically 5-20 mg/mL).

Protocol 2: Automated Imaging and Crystal Detection

Purpose: To automatically monitor, image, and identify crystal formation in high-throughput crystallization trials over time.

Materials:

- Rock Imager or SpectroQ UV system with temperature control

- Crystallization plates from Protocol 1

- Rock Maker software with AI-based autoscoring

Procedure:

- Plate Registration: Register the crystallizations plates in the Rock Imager system using barcode identification, which links physical plates to the experimental design in Rock Maker [36].

- Imaging Schedule: Define an automated imaging schedule in Rock Maker software. Typical schedules image plates immediately after setup (day 0), then daily for the first week, and progressively less frequently over weeks to months [8] [33].

- Multi-Modal Imaging: Configure the imager to capture images using multiple modalities as required:

- Automated Analysis: Enable AI-based autoscoring models (MARCO or Sherlock) integrated with Rock Maker to analyze image datasets and identify potential hits [8].

Critical Notes: UV imaging requires protein crystals containing tryptophan residues. For membrane proteins in LCP, FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) can pre-screen conditions without waiting for crystal growth [8]. Regular calibration of imaging systems is essential for consistent results.

Advanced Applications and Techniques

Imaging Modalities for Crystal Detection

Advanced imaging technologies are critical for accurate crystal identification, especially in high-throughput environments where thousands of images must be analyzed. Each modality offers specific advantages for different crystallization scenarios.

Visible Light Imaging: The standard technique captures images using the visible light spectrum (400-700 nm wavelength). While suitable for analyzing large protein crystals, it cannot distinguish between protein and salt crystals, presenting a significant limitation for automated analysis [8].

Ultraviolet (UV) Imaging: This label-free imaging modality illuminates protein drops with UV light, detecting fluorescence from aromatic amino acids like tryptophan to distinguish protein crystals from salt. However, it may yield false-positive results with phase separation and protein aggregation [8] [33].

Multi-Fluorescence Imaging (MFI): A powerful technique for imaging crystals of fluorescently labeled proteins using the trace fluorescent labeling (TFL) approach. MFI efficiently distinguishes protein crystals from salts, as well as crystals of single proteins from complexes, providing exceptional specificity in complex mixtures [8].

Second Order Nonlinear Imaging of Chiral Crystals (SONICC): This technology combines Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) with Ultraviolet Two-Photon Excited Fluorescence (UV-TPEF) to image protein crystals. It easily detects microcrystals (<1 μm) and crystals obscured in birefringent LCP or buried under aggregates, offering the highest sensitivity for challenging detection scenarios [8] [33].

Specialized Crystallization Methods

Automated systems support various protein crystallization techniques, each with distinct advantages for different protein types and experimental goals. The choice of method depends on multiple factors, including protein type, available volume, and desired outcomes [8].

Table 4: Comparison of Protein Crystallization Techniques

| Method | Amount of Protein | Automation | Seeding | Harvesting | Best Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sitting Drop [8] | Small | Possible | Possible | Easy | Initial screening |

| Hanging Drop [8] | Small to Large | Possible | Possible | Easy | Crystallization optimization using high surface tension reagents |

| Micro-Batch [8] | Small | Not Possible | Not Possible | Difficult | For proteins and reagents having minimal interactions with oil |

| Micro-Dialysis [8] | Large | Not Possible | Not Possible | Easy | For developing large crystals |

| Free-Interface Diffusion [8] | Very Small | Difficult | Possible | Difficult | For diffraction-quality crystals |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase [8] | Small to Large | Possible | Possible | Difficult | For high-quality crystals of membrane proteins |

Automation has fundamentally transformed protein crystallization from a manual, artisanal process to a systematic, high-throughput science. The integrated ecosystem of liquid handlers, crystallization robots, and automated storage imagers has dramatically improved the efficiency, reproducibility, and success rates of crystallization experiments while conserving precious protein samples [8] [30]. This technological evolution enables researchers to comprehensively explore crystallization parameter space by testing multiple protein constructs against hundreds of conditions, significantly accelerating structural biology research and drug discovery pipelines.

Future developments in automation continue to address remaining bottlenecks. The integration of AI-based autoscoring models like Sherlock with crystallization management software represents a significant advancement in handling the extensive image datasets generated by high-throughput systems [8]. As these algorithms continually improve through user feedback and machine learning, their accuracy in distinguishing true crystals from precipitate and salt will further reduce researcher workload and decrease analysis time. The ongoing refinement of nanoliter dispensing technologies, advanced imaging modalities, and integrated software solutions promises to make structural biology increasingly accessible, pushing the boundaries of our understanding of biological macromolecules and facilitating the development of novel therapeutics.

In high-throughput protein crystallization pipelines, accurately distinguishing protein crystals from salt crystals remains a significant challenge, with manual inspection leading to false negative rates as high as 20% [37]. Advanced imaging modalities have emerged as critical tools to overcome this bottleneck, enabling researchers to confidently identify hits and accelerate structural biology and drug discovery efforts. This application note details the operational principles, protocols, and practical implementation of three key technologies: Ultraviolet (UV) imaging, Multi-Fluorescence Imaging (MFI), and Second Order Nonlinear Imaging of Chiral Crystals (SONICC). By integrating these techniques into high-throughput workflows, researchers can significantly improve the efficiency and success of crystallization screening, ultimately advancing structure-based drug design.

Technical Comparison of Imaging Modalities

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of UV, MFI, and SONICC imaging technologies to guide appropriate selection and application.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of advanced imaging modalities for protein crystallization

| Feature | UV Imaging | Multi-Fluorescence Imaging (MFI) | SONICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Tryptophan fluorescence under ~295 nm excitation [37] | Fluorescence from dye-labeled proteins [38] | Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) from chiral crystals [39] |

| Detection Capability | Protein crystals containing tryptophan | Protein crystals (even tryptophan-free via labeling) [38] | Protein microcrystals (<1 μm) [39] |

| Key Strength | Label-free detection | Distinguishes protein-protein complexes [38] | Detects crystals in turbid media (e.g., LCP) [40] |

| Primary Limitation | Weak signal for tryptophan-free proteins; some salt interference [37] | Requires protein labeling with dyes [8] | Cannot distinguish between different chiral protein crystals [39] |

| Typical Imaging Time | ~10 minutes per 96-well plate [38] | ~5 minutes per 96-well plate (visible fluorescence) [38] | Varies by system and plate density |

| Sample Impact | Potential photo-damage with prolonged exposure [40] | Minimal known sample damage [38] | Non-destructive [39] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for UV Imaging

UV imaging leverages the intrinsic fluorescence of tryptophan residues in proteins when excited with UV light at approximately 295 nm [37]. The following protocol ensures optimal results:

- Sample Preparation: Crystallization trials should be set up in UV-transparent plates and sealed with low-UV-absorbing seals to allow maximum transmission of excitation and emission light [37].

- Image Acquisition: Program an automated UV imager (e.g., Rock Imager series) to illuminate drops with UV light at 295 ± 5 nm. A typical exposure time is 1200 milliseconds [37].

- Image Analysis: In the resulting images, protein crystals will typically fluoresce due to their tryptophan content, while salt crystals remain dark. Be aware that certain salts (e.g., primuline yellow) can be fluorescently active and create false positives, while proteins with very low tryptophan content may yield false negatives [37].

Protocol for Multi-Fluorescence Imaging

MFI requires pre-labeling proteins with fluorescent dyes but provides high-contrast images and can differentiate protein complexes [38]. The labeling and imaging protocol is as follows:

- Protein Labeling:

- Prepare a 5 mM stock solution of a succinimidyl ester dye (e.g., Fluorescein or Texas Red) in DMSO.

- Add the appropriate amount of dye to the protein solution to achieve a 0.1% labeling ratio of lysine residues, assuming 1:1 stoichiometric labeling efficiency.

- Incubate for 5 minutes; at this point, approximately 90% of the dye is bound. Purification is typically not required, and the labeled sample remains stable for over 120 days [38].

- Crystallization Setup: Set up crystallization trials using the labeled protein via standard methods (e.g., sitting or hanging drop vapor diffusion).

- Image Acquisition: Image the drops using an MFI-capable imager (e.g., Rock Imager 2 or 360) at the excitation/emission wavelengths specific to the chosen dyes. For studying complexes, label individual proteins or subunits with different dyes [38].

- Analysis: Protein crystals will fluoresce at the specific wavelength of the bound dye. For protein-protein complexes where two different dyes were used, crystals fluorescing at both wavelengths indicate a complex, while fluorescence at only one wavelength indicates a crystal of a single protein [38].

Protocol for SONICC Imaging

SONICC combines Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) and Ultraviolet Two-Photon Excited Fluorescence (UV-TPEF) to detect submicron crystals and crystals obscured in precipitate or lipidic cubic phase (LCP) [40] [39].

- Sample Preparation: Crystallization trials can be set up using standard methods, including LCP and microbatch. No labeling is required.

- Image Acquisition:

- SHG Mode: Use to identify chiral crystalline structures (a property of protein crystals). This produces high-contrast images where protein crystals appear bright white against a black background, even in turbid conditions [39].

- UV-TPEF Mode: Use in conjunction with SHG to confirm the protein nature of the crystals by detecting intrinsic fluorescence, helping distinguish protein crystals from other chiral crystals like sugar [40] [39].

- Analysis: Identify hits by locating bright signals in the SHG channel. Co-localization with UV-TPEF signal strongly confirms a protein crystal.

Workflow Integration and Data Analysis

The integration of UV, MFI, and SONICC into a high-throughput protein crystallization workflow significantly enhances hit identification and validation. The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between these modalities and the critical decision points in the experimental process.

Automated image analysis is crucial for managing the large datasets generated by high-throughput workflows. The integration of AI-based autoscoring models, such as the Sherlock model integrated with Rock Maker software, can streamline the initial analysis of crystallization images [8]. These tools help researchers prioritize conditions for further inspection using the advanced modalities outlined in this document.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of these imaging technologies requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table details the key components for establishing these workflows.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and solutions for advanced imaging workflows

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Transparent Plates/Seals | Allows transmission of UV light for excitation and emission detection in UV imaging [37]. | Plates and seals made from low-UV-absorbing materials (e.g., Cyclo-olefin polymer). |

| Amine-Reactive Dyes | Fluorescent labels for proteins in MFI; bind to lysine residues [38]. | Succinimidyl ester dyes (e.g., Fluorescein, Texas Red). Prepare as 5 mM stock in DMSO. |

| Automated Imaging Systems | Integrated platforms for high-throughput, automated image acquisition. | Rock Imager series (configurable with UV, MFI, SONICC) [38] [8] [39]. |

| Crystallization Screen Reagents | Sparse-matrix and statistical screening cocktails to sample crystallization chemical space [2]. | JCSG+ screen, various commercial and in-house screens. |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automated setup of crystallization trials for precision and reproducibility with sub-microliter volumes. | NT8 Drop Setter, Formulator Screen Builder [8]. |

| Laboratory Information Management System (LIMS) | Software to manage the entire crystallization workflow, from experimental setup to data analysis. | Rock Maker software [8]. |

The integration of UV, MFI, and SONICC imaging technologies provides a powerful, multi-faceted approach to overcoming one of the most persistent challenges in high-throughput protein crystallization. By understanding the specific strengths and applications of each modality—UV for label-free detection, MFI for complex analysis and low-tryptophan proteins, and SONICC for microcrystals and turbid matrices—researchers can design more robust and successful workflows. As the protein crystallization market continues to grow, driven by demand in biopharmaceuticals and personalized medicine [9], the adoption of these advanced imaging techniques will be instrumental in accelerating drug discovery and structural biology research.

Specialized Approaches for Membrane Proteins and Large Complexes

Membrane proteins and large macromolecular complexes represent a significant frontier in structural biology, with profound implications for understanding cellular function and enabling structure-based drug discovery. Despite comprising approximately 30% of all proteins in living organisms and representing over 50% of current drug targets, membrane proteins constitute only about 1.5% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank [41]. This disparity highlights the unique challenges associated with their structural characterization. Unlike their soluble counterparts, membrane proteins require extraction from their native lipid environments using detergents and stabilization in solution for crystallization trials [42]. The entity being crystallized is not merely the protein itself, but rather the protein-detergent complex, introducing additional variables that complicate the crystallization process [42].

Large macromolecular complexes present their own distinct challenges, including structural heterogeneity, conformational flexibility, and difficulties in producing sufficient quantities of homogeneous sample. For both membrane proteins and large complexes, traditional crystallization approaches developed for soluble proteins often prove inadequate, necessitating specialized methodologies tailored to their unique properties. This application note details advanced strategies and protocols developed to address these challenges, enabling researchers to overcome traditional bottlenecks in structural determination of these biologically significant targets.

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Membrane Protein Crystallization

The following table summarizes essential reagents and materials specifically valuable for membrane protein crystallization workflows:

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Membrane Protein Crystallization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Solubilize and stabilize membrane proteins in aqueous solution | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), n-Decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM), n-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) [42] |

| Specialized Crystallization Screens | Rationally designed initial condition screening | MemGold, MemGold2 (for alpha-helical membrane proteins) [42] |

| Additive Screens | Optimization of initial crystal hits | MemAdvantage (contains additives specifically beneficial for membrane proteins) [42] |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Materials | Creating membrane-mimetic environment for crystallization | Monoolein lipid matrices [43] [41] |

| Selenium-labeled Lipids | Experimental phasing for in meso structures | Se-MAG (enables SAD/MAD phasing for LCP-grown crystals) [41] |

| Protein Engineering Tags | Enhancing protein stability and crystallization | T4 lysozyme, BRIL fusions (introduce crystallization scaffolds) [42] |

Quantitative Analysis of Successful Membrane Protein Crystallization Conditions

Analysis of successful membrane protein crystallization experiments reveals distinct trends in detergent selection and precipitant usage that differ markedly from conditions optimal for soluble proteins. The table below summarizes key statistical findings from empirical data:

Table 2: Statistical Analysis of Successful Membrane Protein Crystallization Conditions from Empirical Data

| Parameter | Trend/Optimal Condition | Statistical Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Most Successful Detergent Class | Alkyl Maltopyranosides | Account for 50% of all reported structures [42] |

| Highest Resolution Detergent | Alkyl Glucopyranosides (particularly OG) | Mean resolution of 2.5 Å; highest resolution structure at 0.88 Å [42] |

| Second Highest Resolution Detergent Class | Amine Oxides (e.g., LDAO) | Mean resolution of 2.66 Å [42] |

| Most Successful Alkyl Maltopyranoside | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) | Most frequently used successful detergent in class [42] |

| Primary Precipitants | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) variants | More successful than high-salt conditions commonly used for soluble proteins [42] |

| Functional Family Success Rate | Channels and Transporters | Highest number of determined structures (149 and 157 respectively) [42] |

Specialized Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Crystallization Screening for Membrane Proteins Using Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Method

Principle: The LCP method (also called in meso) creates a membrane-mimetic environment that maintains membrane proteins in a more native lipid bilayer context, often leading to better-ordered crystals [43] [41]. This protocol adapts the method for high-throughput implementation.

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein in appropriate detergent (≥ 5 mg/mL)

- Monoolein or similar lipid

- LCP-capable crystallization plates (e.g., 96-well glass sandwich plates)

- Oryx 4 crystallization robot or similar system with LCP module [43]

- Pre-formulated crystallization screens (MemGold2, MemStart)

- Syringe mixer or similar device for LCP formation

Procedure:

- LCP Formation: Mix purified membrane protein with molten monoolein (typically 60:40, lipid:protein ratio by volume) using a syringe mixer until a clear, viscous cubic phase is obtained. This is evidenced by uniform consistency and optical clarity.

- Plate Setup: Using the LCP module of the crystallization robot, dispense 50-100 nL LCP boluses onto the plate substrate followed by 800-1000 nL of precipitant solution from crystallization screens.

- Sealing: Immediately seal the plate with a transparent cover seal to prevent evaporation.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at controlled temperatures (typically 20°C and 4°C) for crystallization trials.

- Monitoring: Image plates regularly using automated imaging systems (e.g., Rock Imager series) with capabilities for UV imaging or SONICC to detect microcrystals [8].

Technical Notes: Protein concentration and lipid-to-protein ratio are critical parameters that may require optimization. LCP crystallization often produces very small crystals, requiring advanced imaging techniques for detection. The protocol can be modified to include selenium-labeled lipids (Se-MAG) for direct experimental phasing by replacing half of the monoolein with Se-MAG [41].

Protocol: Detergent Optimization for Membrane Protein Crystallization

Principle: Identifying the optimal detergent and detergent combination is often the most critical step in membrane protein crystallization. This systematic approach screens for detergents that enhance stability and promote crystal formation.

Materials:

- Purified membrane protein in initial extraction detergent (e.g., DDM)

- Detergent exchange columns (e.g., size exclusion)

- Range of detergents including alkyl maltopyranosides, glucopyranosides, and amine oxides

- Thermofluor stability assay components or similar stability assessment kit

- Crystallization robots (e.g., NT8 Drop Setter) for high-throughput setup [8]

Procedure:

- Detergent Screening: Set up small-scale (50-100 μL) detergent exchanges into 8-12 different detergents spanning various classes (DDM, DM, OG, LDAO, etc.).

- Stability Assessment: Evaluate protein stability in each detergent using thermal shift assays, monitoring both melting temperature (Tm) and aggregation onset.

- Crystallization Trials: Set up initial crystallization screens (MemGold1 & 2) with the 3-4 most stable detergent conditions using vapor diffusion in sitting drop format with 100 nL drop size.

- Additive Screening: For conditions showing promising hits (microcrystals, phase separation), set up additive screens using MemAdvantage or similar, incorporating 2-5% additive concentrations.

- Detergent Mixing: For proteins that remain unstable in single detergents, systematically test mixed detergent systems, beginning with combinations of maltosides and glucosides.

Technical Notes: Shorter-chain detergents (e.g., OG vs DDM) often produce higher-resolution crystals but may compromise stability [42]. Always assess protein monodispersity after detergent exchange using analytical size exclusion chromatography. The use of detergent cocktails (mixed detergents) has increasingly been successful for challenging targets [42].

Workflow Visualization and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for membrane protein crystallization, incorporating both traditional and specialized approaches:

Diagram 1: Membrane Protein Crystallization Workflow

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

Computational Protein Design for Soluble Membrane Protein Analogues

Recent breakthroughs in deep learning-based protein design have enabled the creation of soluble analogues of integral membrane protein folds, potentially revolutionizing drug discovery approaches. By inverting AlphaFold2 networks combined with ProteinMPNN sequence optimization, researchers have successfully designed stable soluble versions of previously inaccessible membrane protein topologies including GPCRs, claudins, and rhomboid proteases [44]. This approach effectively expands the soluble fold space to include previously membrane-restricted topologies, enabling structural and functional studies without detergent requirements. The method has demonstrated remarkable experimental success rates, with designed proteins showing high thermal stability and accurate structural formation [44].

Advanced Imaging and Automation Technologies

Modern membrane protein crystallography increasingly relies on advanced imaging technologies to detect and characterize often microscopic crystals. Second Order Non-linear Imaging of Chiral Crystals (SONICC) provides exceptional sensitivity for detecting microcrystals (<1 μm) that would be invisible with traditional brightfield microscopy, particularly those obscured in birefringent LCP matrices or buried under aggregates [8]. When combined with Ultraviolet Two-Photon Excited Fluorescence (UV-TPEF), this approach can reliably distinguish protein crystals from salt crystals. Furthermore, fully integrated robotic systems such as the Formulatrix platform (including Rock Maker software, Formulator screen builder, NT8 drop setter, and Rock Imagers) enable complete automation of the crystallization workflow from screen preparation to image analysis, dramatically increasing throughput and reproducibility while minimizing human error and sample consumption [8].