Implementing RFE with Random Forest for Cathepsin Activity Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest for predicting cathepsin inhibitory activity.

Implementing RFE with Random Forest for Cathepsin Activity Prediction: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest for predicting cathepsin inhibitory activity. Cathepsins, such as S, L, and V, are promising therapeutic targets for conditions ranging from cancer to chronic pain and metabolic disorders. The scope covers the foundational biology of cathepsins and the rationale for machine learning, a step-by-step methodological pipeline from data preparation to model building, advanced strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing performance, and rigorous validation against established methods. By synthesizing recent computational advancements, this guide aims to equip scientists with a robust framework for accelerating the discovery of novel cathepsin inhibitors.

Cathepsins as Therapeutic Targets and the Machine Learning Opportunity

The Biological Roles of Cathepsins S, L, and V in Disease

Cathepsins S, L, and V represent a crucial subgroup of lysosomal cysteine proteases with specialized functions that extend far beyond intracellular protein degradation. These enzymes play pivotal roles in immune regulation, tissue remodeling, and neurological health, with their dysregulation implicated in a spectrum of diseases ranging from autoimmune disorders to neurodegenerative conditions and cancer. The unique properties of each cathepsin—particularly their stability at neutral pH and distinct substrate specificities—enable their participation in both intracellular and extracellular pathological processes. Recent advances in computational drug screening and experimental methodologies have accelerated our understanding of these enzymes, positioning them as promising therapeutic targets for numerous conditions. This article explores the distinct biological roles of cathepsins S, L, and V, provides detailed experimental protocols for their study, and contextualizes their investigation within modern drug discovery paradigms, including feature selection techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with random forest for predictive modeling of cathepsin activity.

Biological Functions and Disease Associations

Distinct and Overlapping Roles of Cathepsins S, L, and V

Cathepsin S demonstrates remarkable stability at neutral pH, enabling both intracellular and extracellular functions. It is primarily expressed in professional antigen-presenting cells and plays a non-redundant role in MHC class II-mediated antigen presentation by processing the invariant chain (Ii) [1] [2]. Beyond its immunological functions, cathepsin S exhibits pH-dependent specificity switching—at lysosomal pH (≤6.0), it displays broad proteolytic activity, while at extracellular pH (≥7.0), its specificity narrows significantly due to conformational changes in its active site [3]. This unique property allows cathepsin S to perform specific regulatory functions in the extracellular environment, including activation of protease-activated receptors (PAR-1, PAR-2), processing of IL-36γ, and cleavage of fractalkine, contributing to its role in neuroinflammatory and autoimmune pathologies [1] [2].

Cathepsin L exhibits broader tissue distribution and participates in diverse physiological processes, including MHC class II antigen presentation in thymic epithelial cells, epidermal homeostasis, and neurodegenerative protein clearance [4] [5]. In neuronal populations, cathepsin L contributes to the generation of neuropeptides such as enkephalin and NPY [6]. Its role in neurodegenerative diseases is particularly noteworthy, as it demonstrates efficacy in cleaving pathological aggregates of α-synuclein, suggesting therapeutic potential for Parkinson's disease and related synucleinopathies [7]. Recent research also highlights the significance of cathepsin L in viral entry mechanisms, as it facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry by cleaving the viral spike protein, making it a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19 [8].

Cathepsin V (also known as cathepsin L2) displays the most restricted expression pattern, predominantly found in corneal epithelium, thymus, testis, and skin [6]. This cathepsin exhibits potent elastolytic activity, surpassing even that of other known mammalian elastases. In the immune system, cathepsin V contributes to MHC class II antigen presentation within thymic epithelial cells, playing a role in T-cell selection [6] [5]. Its dysregulation has been associated with various pathological conditions, including corneal disorders (keratoconus), autoimmune conditions (myasthenia gravis), and multiple cancer types [6]. In the context of cancer, cathepsin V overexpression has been documented in squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer, where it likely facilitates tumor progression through extracellular matrix degradation [6].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Cathepsins S, L, and V

| Characteristic | Cathepsin S | Cathepsin L | Cathepsin V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cellular Expression | Antigen-presenting cells (dendritic cells, macrophages, B cells) | Widely expressed, including thymic epithelial cells, skin, brain | Cornea, thymus, testis, skin |

| pH Stability | Stable and active at neutral pH (4.0-8.5) | Primarily active at acidic pH | Active at acidic pH |

| Key Biological Functions | MHC class II invariant chain processing; extracellular signaling; PAR-2 activation | MHC class II processing (thymus); α-synuclein clearance; neuropeptide generation | MHC class II processing (thymus); potent elastolysis; melanosome degradation |

| Primary Disease Associations | Autoimmune diseases (RA, SLE, MS); chronic inflammation; atherosclerosis; neuropathic pain | Parkinson's disease; cancer; SARS-CoV-2 entry; skin disorders | Keratoconus; myasthenia gravis; cancers; atherosclerosis |

| Unique Properties | pH-dependent specificity switching; resistant to oxidative inactivation | Broad substrate specificity; generates neuropeptides | Most potent elastase among human cathepsins; restricted expression pattern |

Disease Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications

The involvement of cathepsins S, L, and V in disease pathogenesis occurs through multiple interconnected mechanisms. In autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, cathepsin S promotes pathology through several pathways: (1) generating autoreactive T-cell responses by limiting the antigenic peptide repertoire during MHC class II presentation; (2) activating PAR-2 to induce neuroinflammatory signaling and pain sensation; (3) degrading extracellular matrix components in atherosclerotic plaques; and (4) inactivating anti-inflammatory mediators such as secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) [1] [2]. The clinical relevance of these mechanisms is underscored by the association of cathepsin S with several top global causes of mortality, including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and Alzheimer's disease [3].

In neurodegenerative contexts, cathepsin L demonstrates significant potential for therapeutic intervention. Recent studies have shown that recombinant human procathepsin L (rHsCTSL) efficiently reduces pathological α-synuclein aggregates in multiple model systems, including iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from Parkinson's disease patients, primary neuronal cultures, and mouse models [7]. Treatment with rHsCTSL not only decreased α-synuclein burden but also restored lysosomal function, as evidenced by recovered β-glucocerebrosidase activity and normalized SQSTM1 (p62) levels, breaking the vicious cycle of impaired protein clearance and neuronal dysfunction [7].

The role of cathepsin V in cancer progression highlights its value as both a biomarker and therapeutic target. In squamous cell carcinoma, cathepsin V expression is significantly upregulated compared to benign hyperproliferative conditions, suggesting its involvement in malignant transformation [6]. Its potent elastolytic activity enables degradation of structural components of the extracellular matrix, facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis. Additionally, in the thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis, abnormal cathepsin V overexpression may disrupt normal T-cell selection processes, potentially contributing to the generation of autoreactive T-cells that drive this autoimmune condition [5].

Table 2: Therapeutic Targeting Approaches for Cathepsins S, L, and V

| Therapeutic Approach | Cathepsin S | Cathepsin L | Cathepsin V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Multiple in clinical trials (e.g., RO5459072); challenges with side effects (itchiness, reduced B cells) | QSAR models for inhibitor design; SARS-CoV-2 entry blockade | Limited development due to structural similarity with cathepsin L |

| Recombinant Enzyme Therapy | Not reported | rHsCTSL for α-synuclein clearance in Parkinson's models | Not reported |

| Allosteric/ pH-Selective Inhibition | Compartment-specific inhibitors under investigation to target extracellular vs. lysosomal forms | Not extensively explored | Not extensively explored |

| Drug Repurposing | Existing drugs targeting downstream effectors (PAR-2 antagonists, IL-36 inhibitors) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Feature Selection in Drug Discovery | RFE with random forest for inhibitor screening and activity prediction | Deep learning models (CathepsinDL) for inhibitor classification | Potential application of similar computational approaches |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Cathepsin-Mediated α-Synuclein Clearance in Cellular Models

Background: This protocol outlines methodology for evaluating the therapeutic potential of recombinant cathepsins L and B in promoting the clearance of pathological α-synuclein (SNCA) aggregates, relevant to Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies. The approach is based on recently published research demonstrating that exogenous application of recombinant procathepsins can be efficiently internalized by neuronal cells and delivered to lysosomes, where they mature into active enzymes and enhance the degradation of SNCA aggregates [7].

Materials:

- Recombinant human procathepsin L (rHsCTSL) and/or procathepsin B (rHsCTSB)

- Cellular models: SNCA-overexpressing cell lines, iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons from PD patients (e.g., SNCA A53T mutation), primary neuronal cultures from Thy1-SNCA transgenic mice

- Culture media appropriate for each cell type

- Fixation solution: 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS

- Permeabilization solution: 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS

- Blocking solution: 5% normal goat serum in PBS

- Primary antibodies: anti-SNCA (various conformation-specific antibodies), anti-LAMP1 (lysosomal marker), anti-CTSL

- Secondary antibodies: fluorophore-conjugated appropriate species

- Mounting medium with DAPI

- Western blot equipment and reagents

- ELISA kits for SNCA quantification

Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Treatment:

- Maintain relevant cellular models in appropriate culture conditions.

- Treat cells with 10-100 nM rHsCTSL or rHsCTSB for 24-72 hours. Include vehicle-only controls.

- For concentration-response studies, test a range of concentrations (1-200 nM).

Cell Processing for Analysis:

- For immunofluorescence: Fix cells with 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilize with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and block with 5% normal goat serum for 1 hour.

- For Western blot: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors.

- For ELISA: Process cells according to kit manufacturer's instructions.

Internalization and Lysosomal Localization Assessment:

- Perform double immunofluorescence staining for CTSL and LAMP1.

- Image using confocal microscopy and analyze colocalization using appropriate software.

SNCA Clearance Evaluation:

- Quantify SNCA levels using Western blot with conformation-specific antibodies.

- Perform ELISA for quantitative assessment of SNCA reduction.

- Conduct immunofluorescence to visualize SNCA aggregate morphology and distribution.

Lysosomal Function Assessment:

- Measure β-glucocerebrosidase activity using fluorescent substrate-based assays.

- Analyze SQSTM1 (p62) levels by Western blot as an indicator of autophagic flux.

Data Analysis:

- Quantify protein levels by densitometry (Western blot) or fluorescence intensity (immunofluorescence).

- Perform statistical analyses (ANOVA with post-hoc tests) to compare treatment groups.

Applications: This protocol enables researchers to evaluate the potential of cathepsin-based therapies for neurodegenerative disorders characterized by protein aggregation, particularly Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies.

Protocol 2: Investigating pH-Dependent Specificity of Cathepsin S

Background: Cathepsin S exhibits a unique pH-dependent specificity switch that regulates its function in different cellular compartments. At lysosomal pH (≤6.0), it displays broad proteolytic activity, while at extracellular pH (≥7.0), its specificity narrows due to conformational changes involving a lysine residue descending into the S3 pocket of the active site [3]. This protocol enables detailed characterization of this phenomenon, which is crucial for developing compartment-specific inhibitors.

Materials:

- Recombinant active human cathepsin S

- Assay buffers: 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.0-5.5), 100 mM MES (pH 5.5-6.5), 100 mM HEPES (pH 6.5-8.0)

- Fluorogenic peptide substrates (e.g., based on sequences from invariant chain, PAR-2, elastin)

- Black 96-well plates

- Fluorescence plate reader

- Crystallization reagents for structural studies

- X-ray crystallography equipment

Procedure:

- Enzyme Activity Assays:

- Prepare cathepsin S (1-10 nM) in appropriate buffers across pH range (4.0-8.0).

- Add fluorogenic substrates at varying concentrations.

- Monitor fluorescence continuously for 10-30 minutes.

- Calculate kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) at each pH.

Peptide Library Screening:

- Design 10-amino acid long peptides covering P4-P6' positions.

- Incubate peptide library with cathepsin S at pH 5.5 and 7.5.

- Analyze cleavage patterns using mass spectrometry.

- Identify preferred cleavage sequences at each pH.

Structural Studies:

- Crystallize cathepsin S at different pH values.

- Collect X-ray diffraction data.

- Solve structures and analyze active site conformations.

- Specifically examine S3 pocket and lysine residue positioning.

Data Analysis:

- Compare cleavage preferences between pH conditions.

- Correlate structural changes with activity differences.

- Identify substrates specifically cleaved at extracellular pH.

Applications: This protocol facilitates the understanding of cathepsin S regulation in different biological compartments and supports the development of pH-selective inhibitors that target pathological without disrupting physiological functions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Cathepsin Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Enzymes | Recombinant human procathepsin L (rHsCTSL); Recombinant human procathepsin B (rHsCTSB) | Therapeutic protein studies; Enzyme replacement approaches; Cellular uptake experiments | Can be produced in HEK293-EBNA cells; Efficiently endocytosed by neuronal cells; Matures in lysosomes [7] |

| Chemical Inhibitors | RO5459072 (cathepsin S inhibitor); Cysteine cathepsin inhibitors with electrophilic warheads | Target validation; Functional studies; Therapeutic candidate screening | Cathepsin S inhibitors show adverse effects (itchiness, reduced B cells); pH-selective inhibitors in development [1] [3] |

| Activity Assay Systems | Fluorogenic substrates; Quenched FRET peptides; Activity-based probes | High-throughput screening; Kinetic characterization; Cellular localization | Design substrates with P2 hydrophobic residues; Consider pH-dependent specificity [3] |

| Computational Tools | CathepsinDL (1D-CNN model); QSAR with SVR and multiple kernel functions; RFE with random forest | Virtual screening; Activity prediction; Compound prioritization | CathepsinDL achieves 90.69%-97.67% classification accuracy for different cathepsins [9] |

| Antibodies | Conformation-specific anti-SNCA; Anti-cathepsin antibodies; Lysosomal markers (LAMP1) | Immunofluorescence; Western blot; ELISA; Immunoprecipitation | Essential for evaluating colocalization and clearance in disease models [7] |

| Cellular Models | iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons (SNCA A53T); Primary neuronal cultures; Organotypic brain slices | Disease modeling; Therapeutic testing; Mechanism elucidation | Preserve pathological features; Allow assessment of endogenous pathology [7] |

Integration with Computational Approaches: RFE with Random Forest for Cathepsin Research

The implementation of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with random forest represents a powerful computational framework for advancing cathepsin research, particularly in drug discovery applications. RFE with random forest enables researchers to identify the most relevant molecular descriptors from large, high-dimensional datasets for predicting cathepsin-inhibitor interactions and activity. This approach iteratively constructs random forest models, ranks features by their importance, and eliminates the least important features, resulting in an optimized subset of descriptors that maximize predictive accuracy while minimizing overfitting [9].

In practice, this methodology has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in screening cathepsin inhibitors. Recent research has achieved classification accuracies of 97.67% ± 0.54% for cathepsin B, 90.69% ± 0.57% for cathepsin S, 97.27% ± 0.23% for cathepsin L, and 92.03% ± 1.07% for cathepsin K inhibitors using a 1D Convolutional Neural Network model built upon selected features [9]. The RFE-random forest pipeline typically involves dataset compilation from sources like BindingDB and ChEMBL, calculation of molecular descriptors from compound structures, recursive feature elimination to identify optimal descriptor subsets, and model training with cross-validation.

This computational approach directly complements the experimental protocols described in this article by enabling virtual screening of compound libraries prior to experimental validation, rational inhibitor design based on key molecular features, and mechanistic interpretation of cathepsin-inhibitor interactions. Furthermore, the integration of these computational methods with structural insights—such as the pH-dependent conformational changes in cathepsin S—promises to accelerate the development of next-generation inhibitors with enhanced specificity and reduced off-target effects.

Challenges in Experimental Inhibitor Screening and the Case for In-Silico Methods

The discovery and development of enzyme inhibitors represent a cornerstone of modern therapeutic intervention, particularly for diseases involving dysregulated enzymatic activity. For decades, the primary path to identifying these inhibitors has been through experimental screening methods, which are now facing significant challenges in efficiency, cost, and scalability. This application note examines the critical limitations of conventional inhibitor screening technologies—including capillary electrophoresis (CE) and high-throughput screening (HTS)—and makes the case for integrating in-silico methods, with a specific focus on recursive feature elimination (RFE) with random forest for predictive modeling of cathepsin inhibition. Within drug discovery pipelines, the implementation of computational approaches is transitioning from a supplementary tool to an essential component for initial candidate selection, thereby streamlining the entire discovery workflow from target identification to lead optimization [10] [11].

Challenges in Conventional Experimental Screening Methods

Traditional methods for inhibitor screening, while foundational, are hampered by several technical and operational constraints that can slow down the discovery process and increase associated costs.

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) and Its Limitations

CE is a powerful separation technique widely used in enzyme inhibitor screening due to its high separation efficiency, minimal sample and solvent consumption, and short analysis time [12] [13]. CE-based assays can be categorized into homogeneous (all reaction components are in a uniform solution) and heterogeneous (enzymes are immobilized on a carrier) systems, each with offline and online analysis modes [13].

Despite its advantages, CE faces notable challenges:

- Pre-capillary (offline) assays, where the enzymatic reaction occurs offline before analysis, often require large reagent volumes despite CE's nanoliter-scale injection volume, leading to waste, especially with expensive enzymes. The need to terminate fast reactions before analysis adds operational complexity and is time-consuming [12].

- In-capillary (online) assays, which integrate reaction, separation, and detection within a single capillary, offer automation and reduced reagent use. However, they can be technically challenging to establish and optimize [12].

- Detection limitations are apparent when substrates and products lack distinct spectrometric properties, and fluorescence detection can suffer from background interference in complex biological samples, increasing the risk of false positives [12] [13].

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Its Drawbacks

HTS employs automated, miniaturized assays to rapidly test thousands to hundreds of thousands of compounds, playing a pivotal role in early drug discovery [14] [15]. It leverages robotics, sensitive detection technologies, and sophisticated data management.

However, HTS carries significant disadvantages:

- High costs and technical complexity associated with sophisticated instrumentation, robotics, and assay development [14] [15].

- Substantial false positive and negative rates due to assay interference from compound autofluorescence, chemical reactivity, metal impurities, and colloidal aggregation [15].

- Physicochemical drawbacks in identified hits, such as high lipophilicity and molecular weight, can lead to poor aqueous solubility and high attrition rates in later development stages [15].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Primary Experimental Screening Platforms

| Screening Method | Throughput | Key Technical Challenges | Primary Sources of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | Low to Medium | Offline mode requires large reagent volumes; Need to quench fast reactions; Detection interference [12] [13]. | Incomplete separation; Background fluorescence; Unoptimized reaction conditions. |

| High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | High (10,000-100,000/day) [15] | High cost and technical complexity; Assay miniaturization challenges [14] [15]. | Compound autofluorescence; Chemical reactivity; Colloidal aggregation [15]. |

The Case for In-Silico Methods

Computational, or in-silico, methods have emerged as powerful tools to overcome the limitations of experimental screening. They simulate various aspects of drug discovery, leveraging databases, computational models, and machine learning to identify and refine potential compounds with desired properties before experimental validation [10].

The Role of In-Silico Screening in Modern Drug Discovery

In-silico techniques are particularly valuable for:

- Virtual ligand screening and profiling: Rapidly evaluating vast virtual compound libraries against a target, significantly reducing the number of compounds requiring physical testing [10] [11].

- Target and lead identification: Using structure-based and ligand-based design to prioritize the most promising targets and compounds [10].

- Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) prediction: Providing early insight into the pharmacokinetic properties of hits, which is often a late-stage bottleneck in purely experimental workflows [10].

The integration of HTS with in-silico analysis has been proven effective in identifying novel inhibitors, as demonstrated in the discovery of new 3CLpro inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2, where computational analysis elucidated binding modes and mechanisms of action [11]. Similarly, high-throughput in-silico screening of 6,000 phytochemicals successfully identified potential TNFα inhibitors, with molecular dynamics simulations refining the selection to two stable triterpenoids [16].

RFE with Random Forest for Cathepsin Inhibitor Prediction

In the context of cathepsin activity prediction, the combination of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and the Random Forest algorithm offers a robust machine-learning framework for building predictive models and identifying critical molecular features.

Mathematical and Operational Principles

- Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training. Its built-in feature importance metric, often based on the mean decrease in impurity (Gini importance) or mean decrease in accuracy, provides a foundation for feature selection [17] [18].

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-style feature selection technique that uses the model's feature importance to recursively prune the least important features. The core RFE process is as follows [17] [18]:

- Train a random forest model using all available features.

- Calculate the importance score for each feature.

- Discard the feature(s) with the lowest importance.

- Repeat steps 1-3 with the reduced feature set until the desired number of features is reached.

A more advanced variant, RFECV (Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation), incorporates an outer layer of cross-validation at each step to evaluate model performance with different feature subsets, thereby providing a more reliable estimate of the optimal feature set and mitigating overfitting [18].

Application to Cathepsin Research For cathepsin inhibitor prediction, RFE-Random Forest can process a high-dimensional feature space comprising:

- Molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological surface area)

- Fingerprint bits indicating specific chemical substructures

- Docking scores from interactions with key cathepsin active site residues

The algorithm identifies a minimal, informative feature subset that maximizes predictive accuracy for inhibitory activity, providing insights into the structural and chemical determinants critical for binding and inhibition.

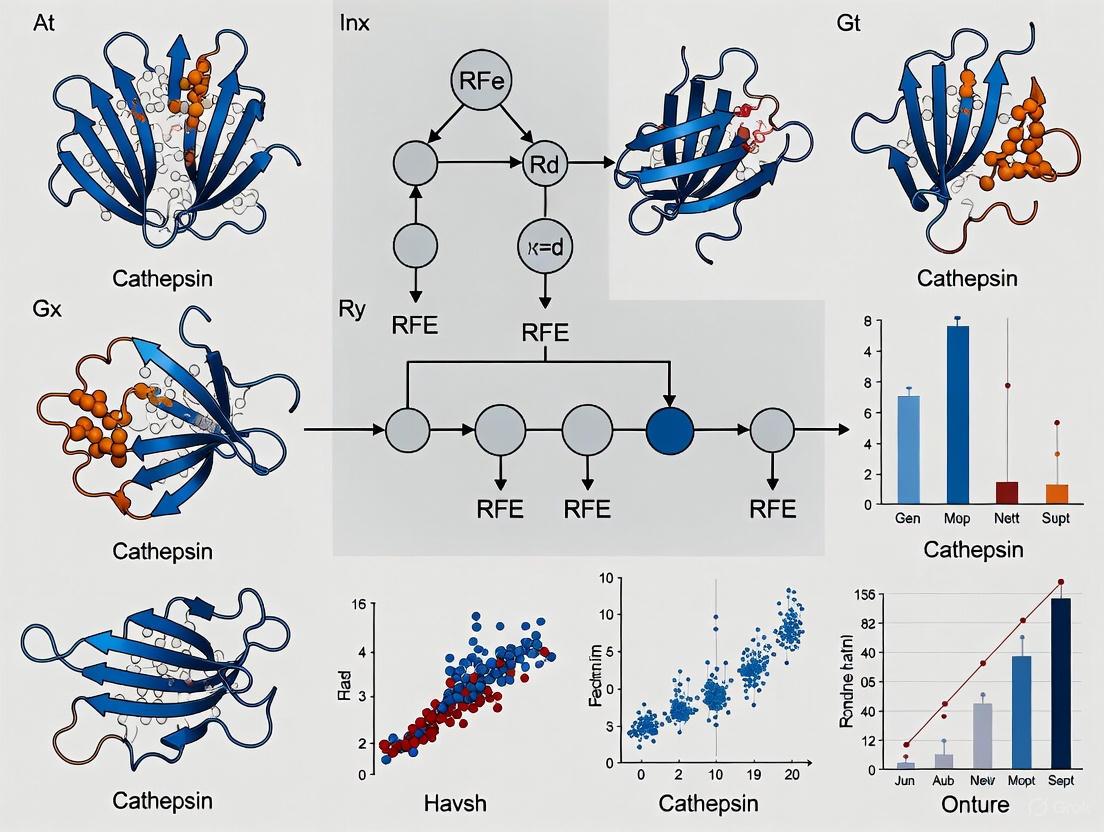

The diagram below illustrates the integrated in-silico and experimental workflow for cathepsin inhibitor identification.

Diagram 1: Integrated In-Silico and Experimental Workflow for Cathepsin Inhibitor Identification. The RFE-Random Forest model prioritizes a subset of virtual hits for downstream experimental validation, streamlining the discovery pipeline.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section outlines standard operating procedures for a key experimental method and the proposed computational approach.

Protocol: Inhibitor Screening via Capillary Electrophoresis (Offline Mode)

This protocol is adapted for screening potential cathepsin inhibitors identified in-silico [12] [13].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CE-Based Inhibitor Screening

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Target Enzyme | The protein of interest (e.g., Cathepsin). Catalyzes the reaction; its activity is monitored. | Recombinant, purified enzyme. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrate | Enzyme substrate. Conversion to product generates a detectable signal (e.g., fluorescence). | Specific to cathepsin isoform (e.g., Z-FR-AMC for cathepsin L). |

| Candidate Inhibitors | Compounds to be tested for inhibitory activity. | Compounds pre-selected by RFE-Random Forest model. |

| Capillary Electrophoresis System | Instrument for separation. | System equipped with UV/VIS or LIF detector. |

| Fused-Silica Capillary | The separation channel. | Internal diameter: 50-75 µm; Length: 30-60 cm. |

| Running Buffer | The electrolyte solution in which separation occurs. | Optimized for enzyme stability and separation (e.g., phosphate/borate buffer, pH 7.4). |

| Positive Control Inhibitor | A known inhibitor to validate the assay. | E-64 for cathepsins. |

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Reaction Mixture Incubation:

- Prepare the master reaction mixture containing cathepsin enzyme and reaction buffer.

- In separate vials, mix the candidate inhibitor (at desired concentration) with the substrate. Include control vials without inhibitor (negative control) and with a known inhibitor (positive control).

- Initiate the enzymatic reaction by adding the master reaction mixture to each vial.

- Incubate at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) for a defined period (e.g., 10-30 minutes).

Reaction Termination:

- Stop the reaction by immediately transferring the vial to an ice bath or by adding a quenching agent (e.g., a strong acid or specific inhibitor like E-64).

CE Analysis:

- Flush the capillary with running buffer.

- Pressure-inject a small aliquot (e.g., 50 nL) of the quenched reaction mixture into the capillary.

- Apply a high voltage (e.g., 15-30 kV) to separate the substrate from the product.

- Detect the peaks using a UV or Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) detector.

Data Analysis:

- Measure the peak area or height corresponding to the product.

- Calculate the enzyme activity in the presence of the inhibitor relative to the negative control (100% activity).

- Compounds showing significant reduction in product formation are confirmed hits.

Protocol: Virtual Screening with RFE-Random Forest

This protocol details the computational screening workflow to prioritize compounds for the subsequent CE assay.

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions (Computational)

Table 3: Essential Tools for RFE-Random Forest Modeling

| Tool/Category | Function/Description | Example/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Database | A digital library of compounds for screening. | ZINC, ChEMBL, in-house collections. |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Software to compute numerical features representing molecular structure. | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor. |

| Machine Learning Library | Programming library implementing RFE and Random Forest. | Scikit-learn (Python). |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | Toolkit for handling chemical data and file formats. | RDKit, Open Babel. |

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Set Curation:

- Compile a data set of known cathepsin inhibitors (active) and non-inhibitors (inactive) from public databases (e.g., ChEMBL) or proprietary sources.

- Standardize molecular structures (e.g., neutralize charges, remove duplicates).

Feature Calculation:

- For each compound, calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors and fingerprints (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices, Morgan fingerprints) using a tool like RDKit.

Model Training and Feature Selection with RFE-CV:

- Initialize a

RandomForestClassifier(fromsklearn.ensemble) with parameters liken_estimators=100. - Initialize

RFECV(fromsklearn.feature_selection) with the random forest model, specifying thestep(number of features to remove per iteration) andcvstrategy (e.g., 5-fold). - Fit the

RFECVobject on the training data. The object will automatically perform the recursive elimination with cross-validation. - After fitting,

RFECVwill identify the optimal number of features and the mask of the selected features.

- Initialize a

Virtual Screening and Prediction:

- Apply the trained and feature-selected model to score and classify compounds in a large virtual library.

- Rank the compounds based on their predicted probability of being active.

Hit Prioritization:

- Select the top-ranked compounds for purchase or synthesis and subsequent experimental validation using the CE protocol above. The selection can also consider drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility.

The limitations of traditional experimental screening methods—including cost, time, high false-positive rates, and reagent consumption—present significant bottlenecks in enzyme inhibitor discovery. In-silico methods, particularly machine learning approaches like RFE with Random Forest, offer a powerful strategy to overcome these hurdles. By enabling the intelligent prioritization of compounds before they enter the wet-lab workflow, this computational approach de-risks the discovery process and accelerates the identification of viable lead compounds. The future of efficient inhibitor screening lies in the tight integration of robust in-silico prediction with targeted, confirmatory experimental studies, as exemplified by the workflow for cathepsin inhibitors outlined in this document.

Core Concepts and Relevance to Cathepsin Research

Random Forest (RF) is a powerful ensemble machine learning method widely used in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling due to its robustness, ability to handle high-dimensional data, and inherent feature ranking capabilities. In drug discovery, RF operates by constructing multiple decision trees during training and outputting the mean prediction (for regression) or mode classification (for classification) of the individual trees. This approach effectively reduces overfitting, a common challenge with single decision trees, and provides reliable predictions for complex biological endpoints like enzyme inhibition.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a feature selection technique that works synergistically with RF. It recursively removes the least important features (as determined by the RF model) and rebuilds the model with the remaining features. This process identifies an optimal subset of molecular descriptors that maximally contribute to predictive accuracy while minimizing noise and redundancy. For cathepsin inhibitor research, this is particularly valuable as it helps pinpoint the specific structural and physicochemical properties essential for inhibitory activity.

The integration of RF and RFE has become a cornerstone in modern computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently screen chemical libraries and prioritize the most promising candidate compounds for synthesis and experimental validation.

Workflow: Implementing RFE with Random Forest for Cathepsin Inhibitor Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for implementing an RFE-RF model in a QSAR study, such as predicting cathepsin inhibitory activity.

Experimental Protocol: A Case Study on Cathepsin L Inhibitors

This protocol details the methodology adapted from a recent study that developed QSAR models to predict the inhibitory activity (IC₅₀) of compounds against Cathepsin L (CatL), a potential therapeutic target for preventing SARS-CoV-2 cell entry [19].

Data Curation and Preparation

- Compound Collection: A dataset of compounds with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values against CatL was compiled. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) quantifies the potency of inhibition, with lower values indicating higher potency [19].

- Descriptor Calculation: A total of 604 molecular descriptors were calculated for each compound using software such as CODESSA. These descriptors encode various 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular properties [19].

- Data Splitting: The dataset was divided into a training set (typically 70-80%) for model development and a test set (20-30%) for external validation of the model's predictive power [19].

Model Training and Feature Selection with RF-RFE

- Random Forest Initialization: A Random Forest regression model was initialized. Key hyperparameters to optimize via cross-validation include the number of trees in the forest (

n_estimators) and the maximum depth of each tree (max_depth) [20]. - Recursive Feature Elimination: The RFE process was employed. The feature importance scores from the RF model were used to recursively prune descriptors. The optimal number of features was determined as the point where model performance (e.g., R² or RMSE) on a validation set is maximized [20].

- Final Model Training: The final RF model was trained using the optimal subset of molecular descriptors identified by RFE.

Model Validation and Analysis

- Performance Metrics: The model's performance was evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for both training and test sets [19].

- Validation Techniques: Five-fold cross-validation (R²₍₅‑ꜰₒₗᵈ₎ = 0.9043) and leave-one-out cross-validation (R²₍ₗₒₒ₎ = 0.9525) were performed to ensure the model's robustness and generalizability [19].

- Descriptor Interpretation: The selected molecular descriptors were analyzed for their physicochemical meaning to glean insights into the structural features critical for CatL inhibition [19].

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors Identified by RF/HM for Cathepsin L Inhibition [19]

| Descriptor Symbol | Physicochemical Meaning | Implication for Inhibitor Design |

|---|---|---|

| RNR | Relative number of rings | Relates to molecular complexity and rigidity. |

| HDH2(QCP) | HA-dependent HDCA-2 (quantum-chemical PC) | Indicates influence of hydrogen bonding and quantum-chemical properties. |

| YS/YR | YZ shadow/YZ rectangle | A topological descriptor related to molecular shape and surface area. |

| MPPBO | Max PI-PI bond order | Suggests importance of pi-pi stacking interactions with the target. |

| MEERCOB | Max e-e repulsion for a C-O bond | Reflects electronic and bond properties within the molecule. |

Performance Benchmarking and Recent Applications

The RF-RFE approach has demonstrated strong performance in various bioactivity prediction tasks. In a study on Cathepsin B, S, D, and K inhibitor classification, a deep learning model that utilized feature selection from molecular descriptors achieved high accuracy, underscoring the value of robust descriptor selection [9]. Furthermore, a random forest model developed to predict depression risk from environmental chemical mixtures showcased the algorithm's power in handling complex, high-dimensional datasets, achieving an exceptional Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.967 [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models in Recent QSAR Studies

| Study / Target | Best Model | Key Performance Metric | Role of Feature Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin L Inhibitors (SARS-CoV-2) [19] | LMIX3-SVR | R² (test) = 0.9632, RMSE = 0.0322 | Heuristic Method (HM) selected 5 critical descriptors from 604. |

| DENV NS3 & NS5 Proteins [21] | SVM / ANN | Pearson CC (test): 0.857 / 0.862 (NS3); 0.982 / 0.964 (NS5) | Molecular descriptors and fingerprints were used to train multiple ML models. |

| Depression Risk (Environmental Chemicals) [20] | Random Forest | AUC: 0.967, F1 Score: 0.91 | RFE was used to identify the most influential chemical exposures from 52 candidates. |

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for RFE-RF QSAR Modeling

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Function in RFE-RF QSAR Pipeline | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Software | Software Suite | Calculates molecular descriptors from compound structures. | CODESSA [19], PaDEL [22], RDKit [23] [9], DRAGON [23] |

| Programming Environment | Computational Framework | Provides libraries for implementing ML algorithms and data analysis. | R (caret package) [22], Python (scikit-learn) [23] |

| Chemical Databases | Data Repository | Sources of chemical structures and associated bioactivity data for training. | ChEMBL [21] [9], BindingDB [9], PubChem [22] |

| Cloud/Workflow Platforms | Platform | Offers reproducible, web-enabled environments for analysis. | Galaxy (GCAC tool) [22], KNIME [23] |

Key Molecular Descriptors and Features for Cathepsin Inhibition

Cathepsins, a family of lysosomal proteases, have emerged as critical therapeutic targets for conditions ranging from viral infections to cancer and metabolic disorders. Cathepsin L (CatL) facilitates SARS-CoV-2 viral entry into host cells by cleaving the spike protein, making its inhibition a promising antiviral strategy [19] [24]. Simultaneously, Cathepsin S (CatS) plays established roles in cancer progression, chronic pain, and various inflammatory diseases [25] [26]. The development of effective cathepsin inhibitors requires a deep understanding of the key molecular features that govern inhibitor-enzyme interactions. This application note explores these critical molecular descriptors and integrates them with a feature selection methodology centered on Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest to advance cathepsin inhibition research.

Key Molecular Descriptors for Cathepsin Inhibition

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies have identified several molecular descriptors critically associated with cathepsin inhibitory activity. The table below summarizes key descriptors identified for Cathepsin L inhibition through advanced QSAR modeling.

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors for Cathepsin L Inhibitory Activity

| Descriptor Symbol | Physicochemical Interpretation | Relationship with Activity |

|---|---|---|

| RNR | Relative number of rings | Negative correlation (-37.67 coefficient) [19] |

| HDH2(QCP) | HA-dependent HDCA-2 (quantum-chemical PC) | Positive correlation (0.204 coefficient) [19] |

| YS/YR | YZ shadow/YZ rectangle | Negative correlation (-4.902 coefficient) [19] |

| MPPBO | Max PI-PI bond order | Positive correlation (25.354 coefficient) [19] |

| MEERCOB | Max e-e repulsion for a C-O bond | Positive correlation (0.242 coefficient) [19] |

For cathepsin S, achieving inhibitor specificity presents a distinct challenge due to significant structural similarities with CatL and Cathepsin K (CatK). The S2 and S3 substrate binding pockets contain the critical amino acid variations that enable selective inhibition [26]. Key residues include Gly62, Asn63, Lys64, Gly68, Gly69, and Phe70 in the S3 pocket and Phe70, Gly137, Val162, Gly165, and Phe211 in the S2 pocket [26]. Successful design of selective CatS inhibitors must prioritize interactions with these specificity-determining residues.

Implementing RFE with Random Forest for Descriptor Selection

Rationale for RFE in QSAR Modeling

The high-dimensional nature of QSAR modeling, where datasets often contain hundreds of calculated molecular descriptors, introduces complexity and risks of overfitting. Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step that improves model accuracy and interpretability by identifying the most relevant descriptors [27]. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper method that recursively constructs models, ranks features by their importance, and eliminates the least important ones until an optimal subset is identified.

Integrated RFE-Random Forest Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process of applying RFE with a Random Forest classifier to identify optimal molecular descriptors for predicting cathepsin inhibition.

Diagram 1: RFE-Random Forest Feature Selection Workflow

This workflow systematically refines the feature set to enhance model performance. Studies have confirmed that wrapper methods like RFE, combined with nonlinear models, demonstrate promising performance in QSAR modeling for anti-cathepsin activity prediction [27].

Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods

Research comparing preprocessing methods for molecular descriptors in predicting anti-cathepsin activity has demonstrated that RFE is highly effective, along with other wrapper methods such as Forward Selection (FS), Backward Elimination (BE), and Stepwise Selection (SS) [27]. These methods, particularly when coupled with nonlinear regression models, exhibit strong performance metrics as measured by R-squared scores [27].

Experimental Validation Protocols

In Vitro Cathepsin Activity Assay

The experimental validation of computational predictions is essential for confirming inhibitor efficacy. The following protocol outlines a standardized method for testing cathepsin inhibition.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Cathepsin Activity Assay

| Reagent / Equipment | Function / Specification | Example Source / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Human Cathepsin | Enzyme source for inhibition assay | e.g., CatL, CatB, or CatS [28] [29] |

| Fluorogenic Substrate | Protease activity measurement | AMC-labeled peptide substrate [30] |

| Assay Buffer | Maintain optimal enzymatic pH | e.g., MES buffer (pH 5.0) for CatB [29] |

| Activating Agent | For cysteine protease activation | e.g., DTT (5 mM) [29] |

| Multi-mode Microplate Reader | Fluorescence detection | e.g., GloMax-Multi+ [28] |

Procedure:

- Enzyme Activation: Pre-activate cathepsin in assay buffer containing 5 mM DTT for 30 minutes at room temperature [29].

- Inhibitor Incubation: Incate the activated enzyme with candidate inhibitors at varying concentrations (e.g., 0.1-100 µM) for 15-30 minutes.

- Reaction Initiation: Add the fluorogenic substrate to initiate the reaction. For example, a cell-free CTSL inhibition assay can be performed using a commercial kit (Abcam, Cat. No. ab65306) [28].

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor the increase in fluorescence (Ex/Em ~355/460 nm for AMC) continuously for 30-60 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage inhibition relative to a DMSO control and determine IC₅₀ values using nonlinear regression of dose-response data.

Experimental Workflow Integration

The following diagram illustrates how computational predictions and experimental validation integrate in the drug discovery pipeline for cathepsin inhibitors.

Diagram 2: Integrated Cathepsin Inhibitor Discovery Pipeline

This integrated approach has successfully identified novel CatL inhibitors from natural products, with deep learning models and molecular docking screening 150 molecules leading to experimental validation of 36 compounds showing >50% inhibition at 100 µM concentration [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Cathepsin Inhibition Studies

| Category / Item | Specific Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Computational Tools | ||

| CODESSA | Calculation of 604+ molecular descriptors | Heuristic QSAR model development [19] [24] |

| Random Forest with RFE | Feature selection for model optimization | Descriptor selection for anti-cathepsin QSAR [27] |

| Schrödinger Suite | Molecular docking and dynamics | Protein-ligand interaction studies [28] [25] |

| Experimental Assays | ||

| Commercial Cathepsin Assay Kits | In vitro inhibitor screening | Abcam Cat. No. ab65306 for CTSL [28] |

| Fluorogenic Peptide Substrates | Enzyme kinetic measurements | AMC-labeled substrates for cathepsin B [30] [29] |

| Chemical Tools | ||

| Peptidomimetic Analogues (PDAs) | CatL inhibitor scaffold | Effective CatL inhibition demonstrated [19] [24] |

| Natural Product Libraries | Source of novel inhibitor scaffolds | Identification of Plumbagin and Beta-Lapachone as CTSL inhibitors [28] |

The integration of computational feature selection methods like RFE with Random Forest and experimental validation provides a powerful framework for advancing cathepsin inhibition research. The key molecular descriptors identified for Cathepsin L (RNR, HDH2(QCP), YS/YR, MPPBO, MEERCOB) and the critical S2/S3 pocket residues for Cathepsin S specificity offer valuable guidance for rational inhibitor design. The standardized protocols and research tools outlined in this application note provide a foundation for systematic investigation of cathepsin inhibitors, potentially accelerating the development of therapeutics for COVID-19, cancer, chronic pain, and other cathepsin-mediated diseases.

Review of Previous ML Applications to Cathepsins and Related Proteases

The application of machine learning (ML) in protease research has become a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, enabling the rapid prediction of compound activity and the efficient identification of novel therapeutic candidates. Cathepsins, a family of lysosomal proteases, have emerged as significant therapeutic targets due to their involvement in various pathological conditions including cancer, metabolic disorders, and viral infections such as COVID-19 [28] [8] [31]. The complexity of biological data associated with cathepsin inhibition necessitates sophisticated computational approaches that can handle high-dimensional descriptor spaces and uncover intricate structure-activity relationships. This review synthesizes recent advancements in ML applications for cathepsin research, with particular emphasis on feature selection methodologies, model architectures, and experimental validation frameworks that support the implementation of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest for cathepsin activity prediction.

Machine Learning Approaches for Cathepsin Activity Prediction

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a fundamental application of machine learning in cathepsin research, employing mathematical and statistical techniques to establish correlations between molecular descriptors and biological activity [27]. Molecular descriptors encompass integer, decimal, and binary numerical values derived from molecular structure, containing comprehensive information about a molecule's physical, chemical, structural, and geometric properties [27]. The substantial number of descriptors involved in QSAR modeling introduces complexities in data calculation and analysis, making data preprocessing through feature selection and dimensionality reduction crucial for directing statistical model inputs [27].

Recent comparative analyses have demonstrated that preprocessing methods significantly impact model performance in predicting anti-cathepsin activity. Filtering approaches such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and wrapping methods including Forward Selection (FS), Backward Elimination (BE), and Stepwise Selection (SS) have shown particular utility when coupled with both linear and nonlinear regression models [27]. Notably, FS, BE, and SS methods exhibit promising performance metrics, especially when integrated with nonlinear regression models, as evidenced by R-squared scores in anti-cathepsin activity prediction [27].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of QSAR Models for Cathepsin L Inhibition Prediction

| Model Type | R² Training | R² Test | RMSE Training | RMSE Test | Cross-Validation (R²) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMIX3-SVR | 0.9676 | 0.9632 | 0.0834 | 0.0322 | 0.9043 (5-fold) | Linear-RBF-polynomial hybrid kernel |

| HM Model | 0.8000 | 0.8159 | 0.0658 | 0.0764 | N/A | Five selected descriptors |

| Random Forest | >0.90 (Accuracy) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.91 (AUC) | Morgan fingerprints |

Advanced Algorithm Implementations

Innovative ML architectures have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in cathepsin inhibition prediction. For Cathepsin L (CTSL) inhibitors as SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics, enhanced Support Vector Regression (SVR) with multiple kernel functions and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has shown exceptional performance [8] [24]. The LMIX3-SVR model, incorporating a hybrid kernel combining linear, radial basis function (RBF), and polynomial elements, achieved outstanding predictive capability with R² values of 0.9676 and 0.9632 for training and test sets respectively, along with minimal RMSE values of 0.0834 and 0.0322 [8] [24]. The PSO algorithm ensured low complexity and fast convergence during parameter optimization [8].

Random Forest classification models have also demonstrated significant utility in cathepsin research. One study trained on IC₅₀ values from the CHEMBL database achieved over 90% accuracy in distinguishing active from inactive CTSL inhibitors, with AUC mean values of 0.91 derived from 10-fold cross-validation [32]. The model utilized Morgan fingerprints (1024 dimensions) as molecular descriptors and successfully identified 149 natural compounds with prediction scores exceeding 0.6 from Biopurify and Targetmol libraries [32].

Deep learning approaches have expanded the capabilities of cathepsin inhibitor discovery. Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) have been employed for binary classification to predict the probability of molecular inhibition against CTSL [28]. This approach facilitated screening of 6439 natural products characterized by diverse structures and functions, ultimately identifying 36 molecules exhibiting more than 50% inhibition of CTSL at 100 µM concentration, with 13 molecules demonstrating over 90% inhibition [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

The foundation of robust QSAR models relies on comprehensive descriptor calculation and rigorous preprocessing. The CODESSA software platform enables computation of numerous molecular descriptors, with studies typically generating 600+ descriptors for each compound [24]. Heuristic Method (HM) linear modeling facilitates descriptor selection by constructing progressive models with increasing descriptor numbers, identifying the optimal descriptor set when additional descriptors cease to significantly improve R² and Rcv² values [24]. For CTSL inhibition prediction, five descriptors were determined optimal: RNR (relative negative charge), HDH2QCP (hydrogen donor hybridization component), YSYR (surface area symmetry), MPPBO (molecular polarizability), and MEERCOB (molecular electrostatic potential) [24].

Nonlinear methods like XGBoost provide complementary descriptor validation through split gain importance calculation. This approach ranks descriptors by importance scores but may retain highly correlated descriptors (correlation coefficients >0.6) [24]. The integration of HM and XGBoost methodologies ensures selection of nonredundant, physiochemically relevant descriptor sets, justifying HM selection for obtaining optimal descriptor subsets [24].

Model Training and Validation Framework

A systematic model training and validation framework ensures predictive reliability and prevents overfitting. For CTSL inhibitor classification, datasets should be curated from reliable sources like CHEMBL, with compounds categorized as active (IC₅₀ < 1000 nM) or inactive (IC₅₀ > 1000 nM) [32]. After removing duplicates, appropriate class distributions (e.g., 2000 active and 1278 inactive molecules) provide balanced training data [32].

Morgan fingerprint calculation (1024 dimensions) using RDKit facilitates structural representation, followed by vectorization for model input [32]. Random Forest classification models should undergo 10-fold cross-validation with ROC curve analysis to evaluate performance, achieving AUC values approximating 0.91 [32]. For regression tasks predicting IC₅₀ values, dataset splitting into training and test sets (typically 80:20 ratio) with five-fold cross-validation (R²₅-fold = 0.9043) and leave-one-out cross-validation (R²loo = 0.9525) demonstrates model robustness [8] [24].

Trained models can screen natural compound libraries (Biopurify, Targetmol), selecting hits with prediction scores >0.6 for subsequent structure-based virtual screening [32]. This integrated approach identified 13 compounds with higher binding affinity than positive control AZ12878478, with the top two candidates (ZINC4097985 and ZINC4098355) demonstrating stable binding interactions in molecular dynamics simulations [32].

Integrated AI and Experimental Validation

The most effective ML applications combine computational predictions with experimental validation. A robust protocol employing deep learning, molecular docking, and experimental assays identified novel CTSL inhibitors from natural products [28]. A binary classification MPNN model predicted CTSL inhibition probability, followed by molecular docking screening of 150 molecules from natural product libraries [28].

Receptor protein preparation utilized human CTSL X-ray structures (PDB ID: 5MQY, resolution 1.13 Å) co-crystallized with a covalent inhibitor [28]. Protein preparation involved deleting water molecules and artifacts, adding hydrogen atoms, generating potential metal binding states, hydrogen bond sampling with active site adjustment at pH 7.4 using PROPKA, and geometry refinement with OPLS3 force field in restrained minimizations [28]. Ligand preparation employed Open Babel for format conversion and LigPrep for ionization state generation at pH 7.4, followed by minimization with OPLSe-3 force field [28].

Molecular docking used glide SP flexible ligand mode with receptor grids generated around the co-crystallized inhibitor centroid [28]. Pose outputs were visualized and analyzed using PyMOL and Discovery Studio Visualizer [28]. Experimental validation confirmed 36 of 150 molecules exhibited >50% CTSL inhibition at 100 µM concentration, with 13 molecules showing >90% inhibition and concentration-dependent effects [28]. Enzyme kinetics studies revealed uncompetitive inhibition patterns for the most potent inhibitors (Plumbagin and Beta-Lapachone) [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cathepsin ML Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Application/Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software & Platforms | CODESSA | Molecular descriptor calculation | Computes 600+ molecular descriptors for QSAR |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics and fingerprint generation | Morgan fingerprints, molecular similarity via Tanimoto coefficient | |

| Schrödinger Suite | Protein preparation, molecular docking | Protein Preparation Wizard, LigPrep, Glide SP docking | |

| Open Babel | Chemical format conversion | Converts SMILES to mol2 format for docking | |

| Experimental Assays | CTSL Activity Test Kit (Abcam, Cat. No. ab65306) | In vitro inhibition validation | Cell-free system for inhibition assessment |

| Expi293 Mammalian Expression System | Recombinant cathepsin production | Human glycosylation patterns, high yield secretion | |

| Data Resources | CHEMBL Database | Compound activity data | IC₅₀ values for active/inactive classification |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank | 3D protein structures | CTSL structure (PDB ID: 5MQY, 1.13 Å resolution) | |

| Natural Product Libraries (Biopurify, Targetmol) | Candidate compound sources | Structurally diverse natural compounds for screening |

Signaling Pathways and Biological Context

Cathepsins function within complex biological pathways that influence their therapeutic targeting. CTSL plays a critical role in SARS-CoV-2 viral entry through cleavage of the viral spike protein, facilitating host cell entry and making it a promising therapeutic target for COVID-19 [8] [33]. In cancer biology, CTSL expression increases in various malignancies including glioma, melanoma, pancreatic, breast, and prostate carcinoma, where it promotes invasion and metastasis through degradation of E-cadherin and extracellular matrix components [32].

Cathepsin S (CathS) contributes to cancer progression and chronic pain pathophysiology, creating immunosuppressive environments in solid tumors and participating in nociceptive signaling [25]. CathS causes immunosuppression in tumors through CXCL12 cleavage and inactivation, reducing effector T cell infiltration while generating fragments that attract regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [25]. In chronic pain, peripheral nerve injury induces microglial activation and CathS release, cleaving protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) on nociceptive neurons to increase excitability and central sensitization [25].

Neutrophil cathepsins regulate immune functions including neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, which contributes to pathogen clearance but can drive pathology when dysregulated in autoimmune diseases, cancer metastasis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury [31]. Cathepsin C activates neutrophil elastase, establishing cathepsins as upstream regulators of NET-associated proteases [31].

Implications for RFE with Random Forest Implementation

The reviewed ML applications provide critical insights for implementing RFE with Random Forest in cathepsin activity prediction. Successful QSAR modeling necessitates appropriate descriptor selection to manage the high dimensionality of molecular feature spaces [27]. RFE offers a robust approach for feature selection, iteratively constructing models and eliminating the least important features to identify optimal descriptor subsets that enhance model performance while reducing complexity [27].

The documented performance of Random Forest classifiers in cathepsin research, achieving >90% accuracy in distinguishing active from inactive CTSL inhibitors, supports its implementation with RFE for feature optimization [32]. The integration of Morgan fingerprints as molecular descriptors aligns with RFE-Random Forest workflows, providing comprehensive structural representations while enabling feature importance evaluation [32].

Cross-validation strategies employed in cathepsin ML studies, including 10-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out approaches, establish rigorous frameworks for evaluating RFE-Random Forest model performance [8] [24] [32]. The consistent reporting of R² values, RMSE, and AUC metrics across studies provides benchmark comparisons for assessing implementation success [8] [24] [32].

The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a closed-loop framework for model refinement, where experimental results inform feature selection and model parameter adjustments in successive iterations [28] [32]. This approach ensures that RFE-Random Forest implementations maintain biological relevance while optimizing predictive performance for cathepsin activity prediction.

A Step-by-Step Pipeline for Building Your RFE-Random Forest Model

Cathepsins are proteases with critical roles in cellular processes, and their dysregulation is implicated in diseases ranging from cancer and metabolic disorders to SARS-CoV-2 infection [19] [32] [34]. Cathepsin L (CatL) is a particularly prominent therapeutic target; it facilitates viral entry into host cells by cleaving the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [19] [8]. Inhibition of CatL is therefore a promising strategy for antiviral drug development [19]. Research into cathepsins relies heavily on high-quality bioactivity data, often expressed as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀), which quantifies the potency of an inhibitor [19] [32].

The process of data curation—sourcing, standardizing, and preparing this bioactivity data—is a foundational step in building reliable predictive models for drug discovery. Public bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL and PubChem BioAssay provide a wealth of data, but this data is not without its challenges [35] [36]. Issues such as transcription errors, inconsistencies in unit reporting, and insufficient assay descriptions can compromise data integrity [35]. Therefore, a rigorous and systematic curation protocol is indispensable for subsequent computational analysis, especially when implementing machine learning techniques like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest.

Sourcing Data from Public Repositories

The first step in the curation pipeline is to gather raw bioactivity data from large-scale public repositories. These databases aggregate experimental data from diverse sources, including scientific literature and high-throughput screening experiments.

- ChEMBL: A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. It contains over 13 million bioactivity data points, including IC₅₀, Kᵢ, and K({}_{\text{D}}) values, which are standardized to consistent units where possible [35].

- PubChem BioAssay: A public repository containing results from high-throughput screening experiments, providing a vast source of bioactivity data [36].

- Biopurify & Targetmol: Commercial libraries specializing in natural products and bioactive compounds, often used for virtual screening campaigns [32].

Large-scale integrated datasets like Papyrus have been constructed to combine and standardize data from multiple sources, including ChEMBL and ExCAPE-DB, facilitating "out-of-the-box" use for machine learning [36]. For cathepsin-specific research, these databases can be queried using target identifiers (e.g., UniProt accession codes) and standard activity types (e.g., 'IC50').

Common Data Integrity Challenges

Data sourced directly from public repositories often contains ambiguities and errors that must be addressed during curation. Key challenges include:

- Unit Transcription and Conversion Errors: The same activity type may be reported in numerous different units (e.g., IC₅₀ values published in molar units, μg/mL, etc.), leading to potential conversion mistakes [35].

- Inconsistent Target Assignment: Ambiguous or incorrect protein target identification can misassociate compounds with specific cathepsins [35].

- Data Redundancy and Citation: The same experimental value may be cited across multiple publications, creating statistical artefacts if not properly identified [35].

- Unrealistic Activity Values: Outliers and transcription errors can result in implausibly high or low activity measurements [35].

Table 1: Common Data Issues and Curation Strategies

| Error Source | Example | Curation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Data Extraction | Missing stereochemistry, incorrect target assignment. | Automated and manual verification against original publication. |

| Author/Publication | Insufficient assay description, wrong activity units. | Standardize activity types and units to a controlled vocabulary. |

| Experimental | Compound purity, cell-line identity issues. | Flag data from assays with known reliability issues. |

| Database User | Merging activities from different assay types. | Apply robust filter strategies based on assay metadata. |

Data Curation and Standardization Protocol

A systematic protocol is essential for transforming raw data into a curated, machine-learning-ready dataset. The following workflow outlines the key steps for curating cathepsin bioactivity data.

Experimental Workflow for Data Curation

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for sourcing and preparing cathepsin bioactivity data.

Step-by-Step Curation Methodology

Step 1: Initial Filtering by Activity Type and Target

- Action: Extract records for the specific cathepsin target of interest (e.g., Cathepsin L) using standardized target identifiers. Retain only relevant activity types, such as IC₅₀, Kᵢ, or K({}_{\text{D}}).

- Protocol: Query databases using REST APIs or direct SQL queries on curated datasets like Papyrus. Filter for

STANDARD_TYPEin ['IC50', 'Ki'] andTARGET_CHEMBL_IDcorresponding to the specific cathepsin [36]. - Rationale: Focuses the dataset on the relevant biological context and measurement type for the research question.

Step 2: Standardization of Activity Values and Units

- Action: Convert all activity values to a consistent unit (typically nanomolar, nM) and transform them to a uniform scale suitable for modeling (e.g., pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀)).

- Protocol: Apply predefined unit conversion rules. For example, convert all IC₅₀ values to nM and then calculate pIC₅₀ [35]. This standardizes the response variable for QSAR modeling.

- Rationale: Enables direct comparison of activity values across different publications and experimental setups, which is critical for building a unified model.

Step 3: Removal of Duplicate Entries

- Action: Identify and consolidate multiple entries for the same compound-target pair.

- Protocol: When multiple measurements exist for a single compound-target pair, apply a consensus strategy. For instance, retain the median pIC₅₀ value if multiple high-quality measurements are available, or flag the data point if measurements are highly discordant (e.g., a difference >0.5 log units) [35] [36].

- Rationale: Prevents statistical bias from over-represented data points and improves model generalizability.

Step 4: Identification and Flagging of Outliers

- Action: Systematically identify potentially erroneous activity values.

- Protocol: Implement automated checks for unrealistic values (e.g., IC₅₀ < 1 pM or > 1 M). Additionally, flag data points associated with known assay artefacts or from publications with insufficient experimental detail [35].

- Rationale: Isolates potentially unreliable data, allowing the researcher to decide on its inclusion or exclusion based on the modeling objective.

Step 5: Standardization of Compound Structures

- Action: Process the chemical structures of compounds to a consistent representation.

- Protocol: Use a standardized chemical structure pipeline (e.g., the ChEMBL pipeline or RDKit) to handle tautomerism, aromaticity, functional group standardization, and removal of salts [36]. Generate canonical SMILES or InChI identifiers for each unique compound.

- Rationale: Ensures that the same chemical entity is not represented by multiple structural identifiers, which is crucial for accurate descriptor calculation.

Step 6: Data Quality Annotation

- Action: Assign a quality score to each data point based on the reliability and reproducibility of the source assay.

- Protocol: In datasets like Papyrus++, data points are labelled as "high quality" if they are associated with reproducible assays (e.g., where measurements for a compound-target pair across different assays are concordant) [36].

- Rationale: Allows for the creation of tiered datasets, enabling model training on the most reliable data and benchmarking performance against noisier data.

Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing for RFE

Once a curated bioactivity dataset is obtained, the next critical step is to calculate and preprocess molecular descriptors for the compounds. These descriptors, which numerically represent molecular structures and properties, form the feature set for predictive modeling.

Calculation and Selection of Molecular Descriptors

Molecular descriptors can be calculated using software such as CODESSA or the RDKit library in Python, generating hundreds to thousands of descriptors characterizing topological, electronic, and geometric properties [19] [36]. For example, a QSAR study on CatL inhibitors initially computed 604 molecular descriptors [19].

Table 2: Key Molecular Descriptors for Cathepsin Inhibitor QSAR

| Descriptor Symbol | Physicochemical Interpretation | Role in Cathepsin Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| RNR | Relative number of rings [19]. | Related to molecular rigidity and scaffold structure; negative coefficient in HM model suggests fewer rings may correlate with higher activity [19]. |

| HDH2(QCP) | HA-dependent HDCA-2 (quantum-chemical PC) [19]. | Encodes electronic properties; positive coefficient indicates a potential role in target interaction [19]. |

| MPPBO | Max PI-PI bond order [19]. | Reflects electron delocalization and aromaticity; positive coefficient suggests potential for π-π stacking in binding pocket [19]. |

| MEERCOB | Max e-e repulsion for a C-O bond [19]. | Indicates steric and electronic environment around specific bonds [19]. |

| ABOCA | Avg bond order of a C atom [19]. | Describes overall bonding pattern; identified as highly important by XGBoost [19]. |

Preprocessing Methods for Feature Selection

The high dimensionality of molecular descriptor data necessitates robust feature selection to avoid overfitting and improve model interpretability. Several preprocessing methods can be employed to reduce the number of descriptors before applying RFE.

- Filter Methods (Recursive Feature Elimination - RFE): RFE is a wrapping method that recursively removes the least important features based on a model's coefficients or feature importance. It has been successfully applied in conjunction with Support Vector Machine (SVM-RFE) to identify core targets in toxicological studies [37].

- Wrapper Methods: These include:

- Forward Selection (FS): Iteratively adds features that most improve model performance.

- Backward Elimination (BE): Iteratively removes the least significant features.

- Stepwise Selection (SS): A combination of FS and BE.

- Studies have shown that FS, BE, and SS, particularly when coupled with nonlinear regression models, exhibit promising performance in QSAR modeling for anti-cathepsin activity [27].

- Nonlinear Filtering (XGBoost): Tree-based models like XGBoost can be used as a nonlinear method to rank descriptor importance by calculating the split gain for each feature. This validates the relevance of descriptors selected by other methods and helps capture complex, nonlinear relationships in the data [19].

Implementing RFE with Random Forest

Within the context of a curated cathepsin dataset, RFE with Random Forest is a powerful technique for identifying the most parsimonious and predictive set of molecular descriptors.

Workflow for RFE and Random Forest Modeling

The following diagram outlines the integrated process of descriptor preprocessing, RFE, and model building for cathepsin activity prediction.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Objective: To identify a minimal, optimal set of molecular descriptors for predicting cathepsin inhibitory activity using Recursive Feature Elimination with a Random Forest model.

Materials and Reagents

- Software: Python (with scikit-learn, RDKit, Pandas) or R.

- Input Data: A curated dataset of chemical structures and corresponding bioactivity values (e.g., pIC₅₀ against Cathepsin L).

- Computational Resources: A standard desktop computer is sufficient for most datasets; larger datasets may require higher memory capacity.

Procedure:

- Feature Calculation and Initialization:

- Calculate an initial, comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (e.g., 500-1000+) for all compounds in the curated dataset using a toolkit like RDKit.

- Split the data into training and test sets (e.g., 80/20 split).

- Initialize a Random Forest regressor (or classifier, for active/inactive classification) and set the criteria for model evaluation (e.g., R² or Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on the test set).

Recursive Feature Elimination Loop:

- Step 1 - Train Model: Train the Random Forest model on the current set of features.

- Step 2 - Rank Features: Rank all features based on their importance scores (e.g., Gini importance or permutation importance) generated by the Random Forest model.

- Step 3 - Eliminate Feature: Remove the least important feature (or a predefined subset of features) from the current set.

- Step 4 - Evaluate Performance: Retrain the model on the reduced feature set and evaluate its performance on the test set.

- Step 5 - Iterate: Repeat steps 1-4 until a predefined number of features remains.

Model Selection and Validation:

- Plot the model performance (e.g., R²) against the number of features used. The optimal feature set is typically located at the point where performance is maximized or before it begins to degrade significantly.

- Validate the final model using the selected features with an external test set or through robust cross-validation (e.g., five-fold cross-validation), as demonstrated in successful CatL QSAR models [19] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Data Curation and Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Public Bioactivity Database | Manually curated source of bioactive molecules and assay data; primary source for ligand-target interactions [35]. |

| Papyrus Dataset | Integrated Curated Dataset | Large-scale, standardized dataset combining ChEMBL and other sources; designed for machine learning applications [36]. |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprinting, and structure standardization [36]. |

| CODESSA | Commercial Software | Comprehensive software for calculating a wide range of molecular descriptors and building QSAR models [19]. |

| scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Python library providing implementations of Random Forest, RFE, and other model evaluation tools. |

| SwissTargetPrediction | Online Tool | Predicts potential protein targets of small molecules based on structural similarity [37]. |

A rigorous data curation pipeline is the cornerstone of robust cathepsin bioactivity prediction. By meticulously sourcing data from public repositories, standardizing values, and addressing common integrity issues, researchers can construct highly reliable datasets. Preprocessing molecular descriptors through methods like Forward Selection or XGBoost, followed by the application of RFE with Random Forest, efficiently identifies a minimal yet highly predictive feature subset. This integrated protocol, from raw data to a validated model, provides a reliable framework for accelerating the discovery of novel cathepsin inhibitors in drug development.