Improving Specificity for Protein Interaction Hotspots: Computational and Experimental Strategies for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to improve the specificity of protein-protein interaction (PPI) hotspot prediction.

Improving Specificity for Protein Interaction Hotspots: Computational and Experimental Strategies for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to improve the specificity of protein-protein interaction (PPI) hotspot prediction. It covers the foundational principles defining PPI hotspots and their critical role in drug targeting. The content explores a spectrum of methodological approaches, from machine learning and graph theory to structural analysis, detailing their practical applications. It further addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges in both computational and experimental validation. Finally, a comparative analysis of current tools and validation frameworks is presented to guide the selection and implementation of high-specificity prediction strategies for advancing PPI-targeted therapeutics.

Defining the Target: The Critical Role of PPI Hotspots in Cellular Function and Disease

Operational Definitions & Core Concepts FAQ

Q1: What is the foundational, energy-based definition of a protein "hot spot"? A hot spot is traditionally defined through alanine scanning mutagenesis as a residue where mutation to alanine causes a significant drop in binding free energy (typically ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) [1] [2]. This energetic penalty demonstrates the residue's critical role in stabilizing a protein-protein interaction (PPI) [2].

Q2: How has the definition of a hot spot expanded in modern research? The definition has broadened beyond purely energetic criteria. Many resources now also classify a residue as a hot spot if its mutation (not necessarily to alanine) significantly impairs or disrupts the PPI, as confirmed by experimental methods like co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) or yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) screening [1] [3]. This functional expansion allows for the inclusion of residues that are critical for interaction integrity but may not meet the strict energetic threshold.

Q3: What is the relationship between a structural "consensus site" and a functional "hot spot"? A consensus site is a region on a protein's surface identified by experimental or computational methods as having a high propensity to bind various small molecule probes [2]. These sites are often, but not always, coincident with energetic hot spots [2]. The key relationship is that residues protruding into these consensus sites are almost always themselves hot spot residues as defined by alanine scanning [2].

Q4: In a protein-protein interface, how is the binding energy typically distributed? The binding energy is not evenly distributed across the large interface. Instead, it is often focused into a small number of complementary "hotspots." For example, in the CaVα1-CaVβ complex, a 24-sidechain interface has its binding energy concentrated in just four deeply-conserved residues that form two key hotspots [4].

Troubleshooting Experimental Hot-Spot Analysis

Q1: My Co-IP/ Pulldown experiment shows no interaction. What are the primary causes?

- Lysis Buffer Stringency: The use of a strongly denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA, which contains ionic detergents like sodium deoxycholate) can disrupt native protein-protein interactions. For Co-IP, use a milder cell lysis buffer [5].

- Epitope Masking: The antibody's binding site on your target protein (the epitope) might be obscured by the protein's conformation or by other bound proteins. Solution: Try an antibody that recognizes a different epitope on the target protein [5].

- Low Protein Expression: The bait or prey protein may be expressed at levels below the detection limit. Solution: Check expression levels in your cell line or tissue using an input lysate control and consult expression databases or literature [5].

- Interaction is Not Direct: The interaction you are studying might be indirect and mediated by a third protein. More sophisticated methods, such as mass spectrometry, may be needed to identify all components of the complex [6].

Q2: I am getting a high background or non-specific bands in my Co-IP. How can I resolve this?

- Inadequate Controls: Always include a bead-only control (beads + lysate) and an isotype control (an irrelevant antibody from the same host species) to identify non-specific binding to the beads or the antibody itself [6] [5].

- Antibody Cross-Reactivity: The antibody may be binding off-target proteins. Solution: Use independently derived antibodies against different epitopes on your target for verification [6].

Q3: My Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) screen yields no positives. What could be wrong?

- Protein Toxicity or Instability: The bait or prey protein may be toxic to yeast or unstable, requiring subcloning of alternative protein segments [6].

- Improper Post-Translational Modifications: Some interactions require specific modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) that the yeast system cannot perform [6].

- Library Quality: The cDNA library may have a low percentage of full-length inserts or may not express proteins that interact with your bait. Solution: Use a high-quality library from a relevant tissue or organism [6].

Q4: How can I capture a transient protein-protein interaction for analysis? Transient interactions can be stabilized using chemical crosslinkers. For intracellular interactions, use membrane-permeable crosslinkers like DSS. For cell surface interactions, use membrane-impermeable crosslinkers like BS3. Ensure your buffer does not contain primary amines (e.g., Tris, glycine) that would out-compete the crosslinking reaction [6].

Quantitative Data & Method Performance

Table 1: Energetic Contributions of Hot Spot Residues in the CaVα1 AID - CaVβ ABP Complex [4]

| Residue Role | Number of Residues at Interface | Binding Energy Concentration | Functional Outcome of Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Interface | 24 sidechains | Distributed across the interface | Reduced affinity |

| Identified Hotspots | 4 residues (2 complementary pairs) | Energy is focused here | Prevents channel trafficking and functional modulation |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PPI-Hot Spot Prediction Methods on a Benchmark Dataset [3]

| Prediction Method | Sensitivity (Recall) | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-hotspotID | 0.67 | N/A | 0.71 |

| FTMap | 0.07 | N/A | 0.13 |

| SPOTONE | 0.10 | N/A | 0.17 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis and Analysis via Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) This protocol is adapted from studies on voltage-gated calcium channels [4].

- Design and Cloning: Identify the protein-protein interaction domain (e.g., the AID peptide). Design primers to mutate target residues to alanine via site-directed mutagenesis.

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and mutant peptides (e.g., AID peptides) and the binding partner (e.g., the CaVβ subunit ABP) using an appropriate system (e.g., E. coli). Use tags (e.g., His-tag) for affinity purification.

- ITC Measurement:

- Dialyze both proteins (or peptide and protein) into an identical, degassed buffer.

- Load the cell with one binding partner (e.g., CaVβ) and the syringe with the other (e.g., AID peptide).

- Perform titrations at constant temperature, injecting the syringe component into the cell.

- A control experiment (injecting peptide into buffer) should be run to account for dilution heats.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting thermogram (plot of heat vs. molar ratio) to an appropriate binding model to derive the binding affinity (Ka, Kd), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS).

Protocol 2: Validating Hot Spots with a Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) Assay

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells expressing your wild-type or mutant protein in a mild, non-denaturing lysis buffer (e.g., Cell Lysis Buffer #9803) [5]. Include protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Avoid strong ionic detergents.

- Preclearing (Optional): Incubate the lysate with bare Protein A/G beads for 30-60 minutes at 4°C to remove proteins that bind non-specifically to the beads.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the precleared lysate with the antibody against your bait protein. Then add Protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-protein complex. Incubate for several hours or overnight at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing and Elution: Wash the beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the bound proteins by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Analysis: Analyze the eluates by Western blotting, probing for both the bait protein and the putative interacting partner (prey).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Hot-Spot Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Cell Lysis Buffer | Extracting native protein complexes without disrupting weak PPIs. | Avoid RIPA buffer for Co-IP; use milder buffers without strong ionic detergents [5]. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Preserving protein integrity and post-translational modifications during extraction. | Essential for studying modified proteins (e.g., phosphorylated targets) [5]. |

| Protein A, G, or A/G Beads | Immobilizing antibodies for immunoprecipitation. | Protein A has higher affinity for rabbit IgG; Protein G for mouse IgG. Optimize bead choice for your antibody host species [5]. |

| Chemical Crosslinkers (e.g., DSS, BS3) | Stabilizing transient or weak protein interactions for detection. | DSS is membrane-permeable for intracellular crosslinking; BS3 is impermeable for cell surface crosslinking [6]. |

| Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Kits | Site-directed mutagenesis to create point mutants for functional testing. | Allows for systematic probing of residue contribution to binding energy [4] [7]. |

| PPI-HotspotID Web Server | Computational prediction of hot spots using free protein structures. | Employs machine learning on features like conservation, SASA, and aa type [1] [3]. |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

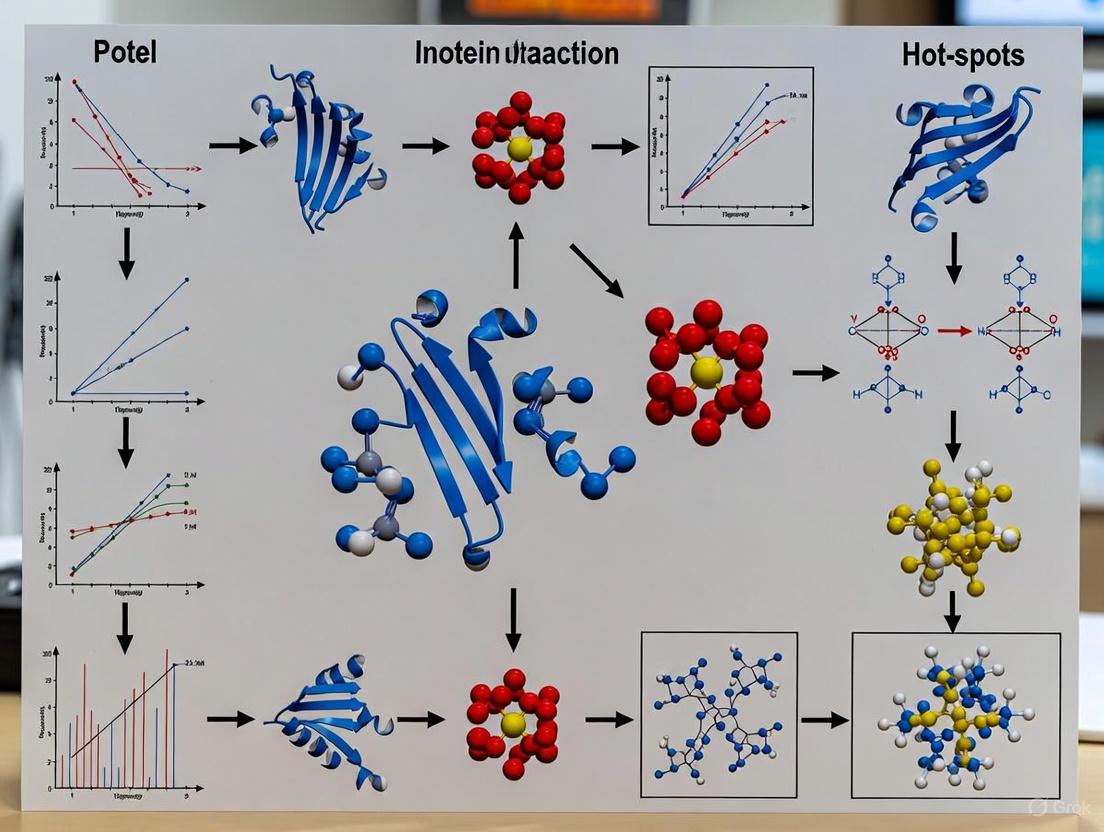

Hot Spot Identification Workflow

Hot Spot Definition Relationships

The Structural and Energetic Landscape of Protein-Protein Interfaces

Foundational Concepts & FAQs

What defines a protein-protein interaction (PPI) hot spot?

A PPI hot spot is typically defined as a residue where mutation to alanine causes a significant drop (≥ 2.0 kcal/mol) in binding free energy [3] [1]. These residues are critical for the interaction's stability and specificity. Beyond this strict energetic definition, the term is also broadly used for residues whose mutation significantly impairs or disrupts the interaction, as determined by methods like co-immunoprecipitation or yeast two-hybrid screening [3] [1].

What are the key biophysical factors controlling affinity at a protein-protein interface?

Affinity maturation pathways at protein-protein interfaces are largely controlled by two key biophysical factors [8] [9]:

- Shape Complementarity: The geometric fit between the two interacting protein surfaces. This dominates the early stages of affinity maturation.

- Buried Hydrophobic Surface: The non-polar surface area removed from solvent upon binding. This becomes responsible for improved binding in the later stages of affinity maturation [8] [9].

The interplay of these forces creates a landscape where binding affinity and specificity are optimized through a combination of structural fit and energetic contributions.

What is the difference between stable and transient protein-protein interactions?

- Stable Interactions: These are long-lasting and are associated with proteins that purify as multi-subunit complexes, such as hemoglobin or core RNA polymerase [10].

- Transient Interactions: These are temporary and often require specific conditions like phosphorylation, conformational changes, or localization to discrete cellular areas [10]. They can be strong or weak, and fast or slow, and are involved in processes like signaling, protein modification, and transport [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Pulldown Assays

Issue: How can I eliminate false positives in my co-IP or pulldown experiments? [11]

| Problem Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Antibody specificity | Use monoclonal antibodies; pre-adsorb polyclonal antibodies against sample devoid of primary target [11]. |

| Non-specific binding to support | Include negative control with non-treated affinity support (minus bait protein) [11]. |

| Non-specific binding to tag | Use immobilized bait control (plus bait protein, minus prey protein) [11]. |

| Interaction mediated by third party | Use immunological methods or mass spectrometry to identify all complex members [11]. |

| Interaction occurs only after lysis | Validate with co-localization studies or site-specific mutagenesis [11]. |

Issue: Why is my bait protein not detected in pulldown assays? [11]

- Protein Degradation: Ensure protease inhibitors are included in your lysis buffer [11].

- Cloning Issues: Confirm the fusion protein was properly cloned into the expression vector [11].

- Detection Sensitivity: Use more lysate or employ a more sensitive detection system like chemiluminescent substrates [11].

Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) Screening

Issue: Why am I getting no transformations in my Y2H screen? [11]

| Problem Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Incorrect antibiotic | Use correct selection: 10 μg/mL gentamicin for bait plasmids, 100 μg/mL ampicillin for prey plasmids [11]. |

| LR Clonase II enzyme issues | Ensure proper storage at -20°C or -80°C; avoid >10 freeze/thaw cycles; use recommended amount [11]. |

| Insufficient transformation mixture | Increase the amount of E. coli plated [11]. |

Issue: Why is there excessive background growth on my Y2H selection plates? [11]

- Technical Issues: Replica clean immediately after plating and again after 24 hours; ensure minimal cell transfer during replica plating [11].

- Preparation Errors: Confirm 3AT plates were prepared correctly with fresh stock solutions and proper calculations [11].

- Incubation Time: Do not incubate plates longer than 60 hours (40-44 hours is optimal) [11].

Issue: Why are my bait and prey proteins not interacting in Y2H? [11]

- Plasmid Issues: Ensure both bait and prey plasmids were co-transformed; plate on correct selection media (SC-Leu-Trp) [11].

- False Positives: Candidate clones might be self-activating mutants of bait; retransform with fresh colonies [11].

- Framing Issues: Sequence the DBD/test DNA junction to ensure gene of interest is in frame with GAL4 DNA Binding Domain [11].

Crosslinking Protein Interaction Analysis

Issue: Why is my crosslinking experiment not capturing transient interactions? [11]

- Reagent Competition: Avoid primary amine-containing buffers (Tris, glycine) that out-compete amine-reactive crosslinkers like DSS or BS3 [11].

- Permeability Issues: For intracellular crosslinking, ensure you're using a membrane-permeable crosslinker [11].

- pH and Freshness: Ensure proper pH for crosslinking and use fresh crosslinkers [11].

- Photo-reactive Crosslinkers: For these, confirm proper UV wavelength (300-370 nm), distance, and exposure time [11].

Advanced Methodologies & Computational Tools

How can I identify PPI hot spots using computational methods?

PPI-HotspotID is a novel machine-learning method that identifies hot spots using only the free protein structure [3] [1]. It employs an ensemble of classifiers and uses only four residue features:

- Evolutionary conservation

- Amino acid type

- Solvent-accessible surface area (SASA)

- Gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) [3] [1]

Performance Comparison of PPI-Hot Spot Detection Methods [3]

| Method | Input | Sensitivity/Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-HotspotID | Free protein structure | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| FTMap (PPI mode) | Free protein structure | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| SPOTONE | Protein sequence | 0.10 | 0.17 |

When combined with interface residues predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer, PPI-HotspotID achieves even better performance than either method alone [3] [1]. The method is available as a freely accessible web server and open-source code [3].

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive PPI Hot Spot Analysis

How do I integrate structural, energetic, and functional analysis?

A comprehensive approach combining crystal structures, binding-free energies, and functional assays reveals how affinity maturation pathways correspond to biological function [8] [9]. This integrated methodology involves:

- Structural Analysis: Determining crystal structures of protein complexes at different affinity stages [8].

- Energetic Profiling: Measuring binding-free energies of variant complexes [8] [9].

- Functional Correlation: Linking biophysical changes to functional outcomes, such as T-cell activation by superantigens [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Target-specific recognition in co-IP; reduces false positives compared to polyclonals [11]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent degradation of bait protein in pulldown assays; essential in lysis buffers [11]. |

| Crosslinkers (DSS, BS3) | Stabilize transient interactions; "freeze" complexes for analysis [11]. |

| Photo-reactive Crosslinkers | Enable temporal control; react only upon UV exposure for capturing dynamic interactions [11]. |

| 3-AT (3-Aminotriazole) | Competitive inhibitor of HIS3 reporter gene in Y2H; controls background growth [11]. |

| SuperSignal West Femto | Maximum sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate for detecting low-abundance proteins [11]. |

| Glutathione Agarose | Affinity support for GST-tagged bait proteins in pull-down assays [10]. |

| Metal Chelate Resins | Capture polyHis-tagged proteins using cobalt or nickel coatings [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental difference between an interface residue and a hotspot? An interface residue is any amino acid located in the physical contact area between two interacting proteins. In contrast, a true hotspot is a very small subset of these interface residues that contributes the majority of the binding free energy. Mutating a hotspot (e.g., to alanine) significantly disrupts the interaction (typically with a ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol), whereas mutating most other interface residues has little to no effect [12] [13].

Why do my computational predictions identify so many interface residues, but experimental validation shows few functional hotspots? This is a classic issue of sensitivity versus specificity. Many prediction methods are trained to identify all interface residues, which form a large, heterogeneous group. However, true hotspots have distinct evolutionary, structural, and physicochemical features. Your model might have high sensitivity (finding many true interface residues) but low precision for the specific, energetically crucial hotspots. The machine learning algorithm may be learning to disregard the non-hotspot residues as noise and identifying only the hotspot residues as the signal [12].

Which machine learning models are best for improving the specificity of hotspot prediction? Recent studies show that advanced ensemble and boosting methods significantly enhance specificity. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) has been demonstrated to outperform other models like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forests by effectively integrating diverse features and handling class imbalance [13]. Furthermore, transformer-based models like Prot-BERT combined with Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) show high generalizability for predicting protein-protein interaction sites from sequence alone [14].

What are the most informative features for distinguishing hotspots from other interface residues? While many features exist, a curated set proves most effective. The PredHS2 method, for instance, identified an optimal set of 26 features. Key discriminators include [13]:

- Evolutionary conservation: Hotspots are often more conserved.

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Related to the "O-ring" theory of solvent exclusion.

- Amino acid type: Tryptophan, arginine, and tyrosine are disproportionately represented.

- Secondary structure propensities: Including novel junction propensities between structures [14].

- Energy terms: Such as gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Precision in Hotspot Predictions

Symptoms: Your computational model successfully predicts a large number of putative interface residues, but subsequent alanine scanning or functional assays confirm only a small fraction of them as true hotspots. Your false positive rate is high.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Action 1: Implement Advanced Feature Selection.

- Procedure: Do not use all available features. Employ a two-step feature selection process to eliminate redundancy.

- Use the minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) method to rank all candidate features.

- Apply a sequential forward selection (SFS) wrapper method, adding features one by one until prediction performance (e.g., F1-score or MCC) no longer improves [13].

- Expected Outcome: This will yield a compact set of highly discriminative features (e.g., ~26 features as in PredHS2), reducing noise and improving model specificity.

- Procedure: Do not use all available features. Employ a two-step feature selection process to eliminate redundancy.

Action 2: Address Class Imbalance.

- Procedure: Hotspots are rare, leading to a skewed dataset. Use techniques like minority class oversampling or adjust the model's class weights during training. For datasets with unlabeled data, consider Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning frameworks [14].

- Expected Outcome: The model will be less biased toward the majority class (non-hotspots) and better at recognizing the critical minority class.

Action 3: Utilize Structural Neighborhoods.

- Procedure: Incorporate information from a residue's structural environment. Extract Euclidean neighborhood properties (residues within a specific radius in 3D space) and Voronoi neighborhood properties (topological neighbors) [13].

- Expected Outcome: This captures the context that shapes a hotspot, such as the "O-ring" of surrounding residues that occlude solvent, a key characteristic of true hotspots [13].

Problem: Handling Proteins Without Solved Complex Structures

Symptoms: You need to predict hotspots for a protein of interest, but no 3D structure of its complex with a partner is available. Structure-based prediction methods are not applicable.

Diagnosis and Solution:

- Action 1: Leverage Sequence-Based Deep Learning.

- Procedure: Use protein language models like Prot-BERT [14]. These models, pre-trained on millions of protein sequences, generate rich, context-aware feature representations from a single protein sequence, capturing evolutionary and functional patterns predictive of interaction sites.

- Expected Outcome: Ability to make robust predictions directly from sequence, bypassing the need for structural data.

- Action 2: Combine Predictors.

- Procedure: Use a method like PPI-hotspotID, which can work with free protein structures (unbound) and can be combined with interface residues predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer. This integrated approach has been shown to outperform either method alone [3].

- Expected Outcome: Improved reliability of hotspot predictions when only the unbound structure or a high-quality predicted complex is available.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis for Experimental Hotspot Validation

Purpose: To experimentally identify hotspot residues by systematically mutating interface residues to alanine and measuring the change in binding affinity.

Procedure:

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Design and generate mutant constructs where each candidate interface residue is replaced with alanine. This side-chain truncation removes interactions without altering the protein backbone.

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the wild-type and all mutant proteins.

- Binding Affinity Measurement: Determine the binding constant (Kd) between each mutant protein and its interaction partner using a technique like Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR).

- Calculate ΔΔG: Compute the change in binding free energy using the formula: ΔΔG = -RT ln( Kd(mutant) / Kd(wild-type) ).

- Classification: A residue is typically defined as a hotspot if ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol [13].

Quantitative Performance of Select Prediction Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various methods, highlighting the challenge of achieving high specificity (precision) while maintaining good sensitivity (recall).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Hotspot Prediction Methods

| Method | Input Data | Sensitivity (Recall) | Precision | F1-Score | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PredHS2 (XGBoost) [13] | Protein Complex Structure | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.689 | 26 optimal features (e.g., SASA, conservation, energy) |

| Prot-BERT-ANN [14] | Protein Sequence Only | 0.53 (avg. for IAV proteins) | N/A | N/A | Contextual sequence embeddings from a transformer model |

| PPI-hotspotID [3] | Free Protein Structure | 0.67 | 0.75 | 0.71 | Conservation, amino acid type, SASA, ΔGgas |

| D-SCRIPT [14] | Protein Sequence Only | 0.18 (avg. for IAV proteins) | N/A | N/A | Neural language model predicting interaction interfaces |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| ASEdb / BID / SKEMPI | Databases of experimental hotspot data from alanine scanning mutagenesis; used for training and benchmarking computational models. [14] [13] | Alanine Scanning Energetics Database (ASEdb), Binding Interface Database (BID) |

| PPI-HotspotDB | A comprehensive database of experimentally determined hotspots, including those from expanded definitions beyond alanine scanning. [3] | PPI-HotspotDB |

| XGBoost | An advanced, scalable machine learning algorithm based on gradient boosting, highly effective for building classification models with high specificity. [13] | Chen & Guestrin, 2016 |

| Prot-BERT | A deep learning model that generates feature representations from protein sequences, enabling state-of-the-art sequence-based prediction. [14] | Hugging Face Model Repository |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Predicts the 3D structure of a protein complex from sequence; output can be used to identify interface residues for subsequent hotspot analysis. [3] | AlphaFold Server |

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Experimental Hotspot Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for identifying hotspots, integrating both computational prediction and experimental validation.

The O-Ring Theory of Hotspots

This diagram visualizes the "O-ring" theory, a key conceptual model for why only specific residues are hotspots.

Hotspots as Attractive Therapeutic Targets in Cancer, Neurodegenerative, and Infectious Diseases

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Q1: What exactly is a "hot spot" in the context of protein-protein interactions (PPIs)? A PPI hot spot is defined as a residue or a cluster of residues within a protein-protein interface that makes a substantial contribution to the binding free energy. Conventionally, these are residues whose mutation to alanine causes a significant drop (≥2 kcal/mol) in the binding free energy. These residues are often part of tightly packed "hot regions" that provide flexibility and the capacity to bind to multiple different partners [15].

Q2: Why are PPI hot spots considered attractive therapeutic targets? Hot spots are attractive targets because they are central to the interaction networks that drive cellular processes. Dysregulation of these PPIs is associated with cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and infectious diseases. Targeting these specific, critical residues allows for the precise modulation of pathological interactions—either inhibiting detrimental ones or stabilizing beneficial ones—with high potential for therapeutic effect and reduced off-target consequences [15] [1] [16].

Q3: What are the key differences between PPI hot spots and mutation hot spots in cancer genomics? These are distinct concepts. PPI hot spots are functional sites on a protein's surface critical for binding energy. In contrast, cancer mutation hot spots are specific genomic positions recurrently mutated across patients, presumably because they confer a selective growth advantage to cancer cells (e.g., in genes like BRAF, KRAS). While both are "hot spots," one refers to protein function and interaction, and the other to mutation frequency in a population [17].

Q4: Can hot spots be found in disordered protein regions, or only in structured domains? Yes, hot spots can exist within both structured and disordered protein interfaces. This complexity necessitates innovative targeting strategies. For instance, chimeric peptide inhibitors have been developed that contain both a structured, cyclic part and a disordered part to simultaneously target structured and disordered hot spots on the same protein, such as iASPP in cancer [18].

FAQs: Computational and Experimental Identification

Q5: What are the main computational methods for predicting PPI hot spots, and how do they differ? Computational methods fall into two primary categories, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Computational Methods for PPI Hot Spot Prediction

| Method Category | Description | Key Tools/Examples | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy-Based Methods | Calculate the binding free energy difference between wild-type and mutant proteins using force fields or empirical scoring functions [1]. | FoldX, Roberta [1]. | Protein complex structure. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Classifiers | Employ classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) trained on features like evolutionary conservation, solvent accessibility, and amino acid properties [14] [1]. | PPI-hotspotID [1] [3], KFC2 [1], SPOTONE [1]. | Varies; can use complex structure, free structure, or sequence only. |

Q6: My hot spot prediction results have low precision. How can I improve specificity? Low precision (many false positives) is a common challenge. To improve specificity:

- Combine Complementary Methods: Integrate different computational approaches. For example, using interface residues predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer as a filter for other hot spot prediction methods has been shown to enhance performance [1] [3].

- Leverage Larger, Curated Datasets: Train or validate your models on larger, broad-definition databases like PPI-HotspotDB, which contains over 4,000 experimentally determined hot spots, to reduce overfitting and improve generalizability [1] [3].

- Incorporate Biological Context: Use features like evolutionary conservation and structural context (e.g., solvent-accessible surface area) that are hallmarks of true functional residues [1].

Q7: What is a typical experimental workflow to validate a predicted hot spot? A standard validation workflow involves structure-based mutagenesis followed by binding or functional assays, as outlined in the diagram below.

Detailed Protocol: Experimental Validation of a Predicted PPI Hot Spot

- Principle: Disrupting a critical hot spot residue via mutation should significantly impair the protein-protein interaction and its downstream biological function.

- Materials:

- Plasmid containing the wild-type gene of interest.

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit.

- Cell line for protein expression (e.g., HEK293T).

- Antibodies for immunoprecipitation (Co-IP).

- Equipment for binding assays (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance - SPR).

- Procedure:

- Mutagenesis: Design primers to mutate the predicted hot spot residue to alanine. Perform site-directed mutagenesis on the wild-type plasmid to generate the mutant construct [1].

- Protein Expression: Transfect an appropriate cell line with both wild-type and mutant plasmids. Express and purify the proteins using standard protocols (e.g., affinity chromatography) [1].

- Binding Assay:

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Lyse transfected cells and perform Co-IP using an antibody against your protein of interest. Probe the immunoprecipitate via Western blotting for its known interaction partner. A significant reduction in binding for the mutant compared to wild-type supports the prediction [1] [3].

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Immobilize one interaction partner on a sensor chip and flow the wild-type or mutant protein over it. A substantial decrease in binding affinity (increase in K~D~) for the mutant confirms its importance [1].

- Functional Assay: In a relevant cellular model, assay a pathway or phenotype dependent on the PPI. For example, if the interaction promotes cell survival, test if the mutant protein fails to rescue cell death upon knockdown of the endogenous protein [18].

FAQs: Therapeutic Targeting and Troubleshooting

Q8: What strategies exist for targeting PPI hot spots with small molecules or peptides? The table below outlines key therapeutic strategies for targeting PPI hot spots.

Table 2: Strategies for Therapeutic Targeting of PPI Hot Spots

| Strategy | Mechanism | Example/Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Bind to hot spot regions, disrupting the PPI. Often identified via HTS or FBDD [15]. | Venetoclax (BCL-2 inhibitor), Sotorasib (KRAS inhibitor) [15]. |

| Stapled/Peptidomimetic Inhibitors | Stabilize secondary structures (e.g., α-helices) to mimic key interaction motifs, improving stability and binding [15] [18]. | Stapled helical peptides targeting iASPP in cancer cells [18]. |

| Chimeric Peptide Inhibitors | Combine structured (e.g., cyclic) and disordered peptide parts to target both structured and disordered hot spots on a single protein [18]. | Chimeric peptides targeting iASPP, showing enhanced cytotoxicity [18]. |

| PPI Stabilizers | Enhance the formation or stability of a protein complex, a emerging therapeutic modality [15] [16]. | Potential application in diseases caused by loss-of-function interactions [15]. |

Q9: I've identified a potential hot spot, but it's a flat, featureless surface. How can I target it? Flat PPI interfaces are notoriously difficult to target with traditional small molecules.

- Use Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): FBDD uses low molecular weight fragments that can bind to small, discontinuous sub-pockets within the flat interface. These fragments can then be linked or optimized into larger, high-affinity inhibitors [15].

- Explore Peptidomimetics: Design molecules that mimic the key secondary structure (e.g., α-helix, β-sheet) of one protein partner that engages the hot spot. Stapled peptides are a prominent example that confer proteolytic resistance and cell permeability [15] [18].

- Leverage AI and Computational Tools: AI-driven algorithms can now model complex PPI structures and identify cryptic pockets or design binders that target flat surfaces with remarkable accuracy [16].

Q10: The therapeutic agent targeting a hot spot shows efficacy in cells but not in animal models. What could be wrong? This discrepancy can arise from several factors:

- Pharmacokinetics (PK): The agent may have poor absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion (ADME) properties in vivo. Check its bioavailability, half-life, and tissue penetration.

- Off-Target Effects: The agent might be hitting other targets in vitro, where concentration is precisely controlled, but its effect is diluted in vivo by a more complex proteome.

- Redundant Pathways: The disease pathway in vivo may have redundancy that is not present in your cellular model, bypassing the inhibition of your single target.

- Compound Stability: The compound may be degraded or inactivated in the serum or specific tissues of the animal model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PPI Hot Spot Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PPI-HotspotDB | A comprehensive database of over 4,000 experimentally determined PPI hot spots. Used for training ML models and benchmarking predictions [1] [3]. | Calibrating new computational hot spot prediction methods. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | An AI system that predicts the 3D structure of protein complexes from sequence. Can predict interface residues to guide hot spot identification [1] [3]. | Providing structural context for proteins with unknown complex structures. |

| FTMap Server | A computational mapping server that identifies hot spots on protein surfaces by finding consensus binding sites for small molecular probes [1]. | Identifying potential binding hot spots on a free protein structure. |

| PPI-Focused Compound Libraries | Chemically diverse libraries enriched with compounds (small molecules, fragments) likely to target PPI interfaces [16]. | High-throughput screening to discover initial hits for PPI modulation. |

| Stapled Peptide Synthesis Kits | Facilitate the creation of stabilized α-helical peptides through site-specific hydrocarbon stapling. | Generating metabolically stable peptide inhibitors for cellular and in vivo studies [18]. |

The following diagram illustrates the integrated research and development pipeline for discovering and targeting PPI hot spots, connecting the tools and strategies discussed.

A Methodological Toolkit: From Machine Learning to Network Analysis for High-Specificity Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My model for predicting protein-protein interaction (PPI) hot spots has high recall but poor precision, leading to too many false positives. What feature-related issues should I investigate? A high false positive rate often stems from two key issues: class imbalance and uninformative features. PPI hot spots are rare, making it easy for models to overfit to noise. Furthermore, features that do not directly distinguish hot spot from non-hot spot residues add dimensionality without benefit. To address this:

- Action: Implement rigorous feature selection. The method PPI-hotspotID demonstrated that using just four key features—conservation, amino acid type, SASA, and ΔGgas—can achieve high precision (0.76) and an F1-score of 0.71, significantly outperforming methods that use broader, less curated feature sets [19]. This focuses the model on the most discriminative information.

Q2: Why are the features Conservation, SASA, and ΔGgas particularly powerful for achieving high specificity in PPI hot spot prediction? These three features provide a multi-faceted physicochemical and evolutionary profile that is highly characteristic of functionally critical residues.

- Conservation: Hot spots are often found in structurally conserved regions [20]. Evolution preserves residues that are critical for function and binding.

- Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA): This feature describes the residue's exposure to the solvent. Hot spots, while often buried in the interface, have specific accessibility characteristics that can be a strong predictive signal [19].

- Gas-Phase Energy (ΔGgas): This energetic feature, often derived from force fields, estimates the contribution of a residue to the stability of the interaction, directly relating to the binding free energy change upon mutation [19].

Q3: My model performs well on the training data but generalizes poorly to new protein complexes. How can feature selection improve this? This is a classic sign of overfitting, frequently caused by a high number of features relative to the number of training samples. Irrelevant or redundant features allow the model to learn patterns specific to the training set that are not generally applicable [21].

- Action: Employ feature selection methods like Random Forests to identify and retain only the most informative features [20] [22]. This reduces model complexity, minimizes learning from noise, and enhances generalizability by ensuring the model focuses on robust, transferable signals.

Q4: Are ensemble methods useful for combining these features, and how do they compare to single-model approaches? Yes, ensemble methods are highly effective. They combine the predictions of multiple base classifiers (e.g., SVM, KNN) to create a more robust and accurate final model. This approach mitigates the weaknesses of any single classifier.

- Evidence: One study using an ensemble of SVM and KNN with sequence-based features achieved an F1 score of 0.92 on the ASEdb dataset, a significant improvement over many single-model methods [23]. Similarly, PPI-hotspotID itself uses an ensemble of classifiers [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Specificity and Precision in Predictions

Problem: Your model identifies many residues as hot spots, but experimental validation shows most are not. The specificity and precision metrics are unacceptably low.

Diagnosis and Solution Steps:

Audit Your Feature Set:

Implement Advanced Feature Selection:

- Action: Use a method like Random Forest to rank feature importance. Train your final model using only the top-ranked features.

- Protocol: Using scikit-learn in Python, you can train a

RandomForestClassifier, access thefeature_importances_attribute, and select features with importance above a chosen threshold. This ensures only the most discriminative features are used.

Incorporate Spatial Neighbor Information:

- Problem: Features are calculated only for the target residue, ignoring its microenvironment.

- Solution: Extract hybrid features that include information from the target residue's spatial neighbors, such as the nearest contact residue on the binding partner and the nearest residue on the same chain [20].

- Rationale: Hot spots often exist in tightly packed clusters, and their identity is influenced by their spatial context [20].

Issue: Handling Small and Class-Imbalanced Datasets

Problem: The number of known hot spot residues is very small compared to non-hot spots, leading to a model biased toward the majority class.

Diagnosis and Solution Steps:

Apply Data Resampling Techniques:

- Action: Use the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to generate synthetic examples of the minority class (hot spots) [22].

- Protocol: Employ the

imbalanced-learnlibrary in Python. After partitioning your data, apply SMOTE only to the training set to avoid data leakage. - Rationale: This creates a balanced dataset for training, preventing the model from being biased toward predicting the more common non-hot spots.

Utilize the Largest Available Benchmark:

- Action: Train and validate your model on the most comprehensive, non-redundant benchmark available, such as PPI-Hotspot+PDBBM [19].

- Rationale: This dataset contains over 4,000 experimentally determined hot spots, providing a much larger and more robust foundation for training models and reducing the risk of overfitting from small sample sizes [19].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Method for PPI-hotspotID Feature Extraction and Validation

The following workflow outlines the key steps for building a high-precision prediction model, as demonstrated by PPI-hotspotID [19].

1. Data Curation:

- Source: Use a non-redundant benchmark dataset like PPI-Hotspot+PDBBM [19]. Ensure proteins share < 60% sequence identity to avoid homology bias.

- Definition: PPI-hot spots are defined as residues whose mutation causes a ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol drop in binding free energy or is manually curated in UniProt as significantly impairing the interaction [19].

2. Feature Extraction:

- Conservation: Calculate evolutionary conservation scores for each residue using tools like ConSurf, which analyzes homologous sequences.

- SASA (Solvent-Accessible Surface Area): Compute the SASA for each residue from the free protein structure using a tool like DSSP or from the free protein structure directly within the PPI-hotspotID method [19]. Units are typically in Ų.

- ΔGgas (Gas-Phase Energy): Calculate this energy term using a molecular mechanics force field. It represents the intramolecular energy of the residue in the protein environment.

- Amino Acid Type: Encode the amino acid as a categorical or one-hot feature.

3. Model Training & Validation:

- Classifier: Use an ensemble machine learning classifier, such as the one implemented in PPI-hotspotID [19].

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold) on the training set.

- Performance Metrics: Calculate Sensitivity (Recall), Precision, Specificity, and F1-score on an independent test set. The following table summarizes the performance achievable with a focused feature set:

Table: Performance Comparison of PPI Hot Spot Prediction Methods

| Method | Input Data | Key Features | Precision | Recall (Sensitivity) | F1-Score | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-hotspotID | Free Structure | Conservation, SASA, ΔGgas, AA Type | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.71 | Not Reported [19] |

| FTMap (PPI Mode) | Free Structure | Probe cluster consensus sites | Very Low | 0.07 | 0.13 | Not Reported [19] |

| SPOTONE | Sequence | Sequence-derived features | Very Low | 0.10 | 0.17 | Not Reported [19] |

| Ensemble (SVM+KNN) | Sequence | Auto-correlation, relASA | Not Reported | Not Reported | 0.92 | Not Reported [23] |

Protocol for Integrating AlphaFold-Multimer with Feature-Based Prediction

Objective: Enhance prediction by combining interface residue information from AlphaFold-Multimer with the energetic and evolutionary features from PPI-hotspotID.

Procedure:

- Predict Interface: Run AlphaFold-Multimer on the free protein structure and its binding partner to predict the complex structure and identify interface residues [19].

- Filter Residues: Restrict your subsequent analysis to the set of predicted interface residues. This drastically reduces the search space and the class imbalance problem.

- Run PPI-hotspotID: Apply the PPI-hotspotID method (or your own model based on Conservation, SASA, and ΔGgas) only to these predicted interface residues.

- Combine Results: The final hot spot predictions are the high-probability outputs from the feature-based model within the AlphaFold-predicted interface. This combined approach has been shown to yield better performance than either method alone [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for PPI Hot Spot Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-HotspotDB | Database | Repository of experimentally determined PPI hot spots. | Provides a large, curated benchmark for training and testing prediction models [19]. |

| ASEdb / BID | Database | Legacy databases of binding energetics from alanine scanning mutagenesis. | Source of standardized hot spot data for building and comparing models [23] [20]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software Tool | Predicts the 3D structure of protein complexes from sequence. | Identifies potential protein-protein interfaces from free structures to narrow down the residue search space [19]. |

| Robetta | Web Server | Provides binding free energy estimates upon alanine mutation. | Used as an energy-based computational method for hot spot prediction and validation [20]. |

| Random Forest (scikit-learn) | Algorithm | A powerful ensemble ML algorithm for classification and regression. | Used for both feature selection and as a classifier to build the final prediction model [20] [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main difference between PPI-hotspotID, FTMap, and SPOTONE? PPI-hotspotID is a machine-learning method that uses the free protein structure to predict residues critical for protein-protein interactions (PPIs), employing features like conservation, amino acid type, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) [24] [1]. FTMap identifies binding hot spots for protein-protein interactions by finding consensus sites on the free protein structure that bind clusters of small molecular probes [24] [25]. SPOTONE predicts PPI-hot spots directly from the protein sequence using an ensemble of extremely randomized trees [1] [26].

Q2: When should I use the PPI mode in FTMap? You should use the PPI mode in FTMap when your goal is to detect binding hot spots specifically for protein-protein interactions rather than for small molecule binding [25]. This mode uses an alternative set of parameters tailored for PPIs.

Q3: My dataset of protein structures is non-redundant. How does PPI-hotspotID ensure reliable performance? PPI-hotspotID was validated on the largest collection of experimentally confirmed PPI-hot spots to date, using a benchmark dataset of 158 non-redundant proteins (sharing <60% sequence identity) with free structures [27] [1] [26]. The use of cross-validation during model development helps provide a reliable estimate of performance and reduces variability [24].

Q4: Can these tools predict hot spots that are not in direct contact with a binding partner? Yes, this is a noted capability of PPI-hotspotID. While many methods predict residues that make multiple contacts across a protein-protein interface, PPI-hotspotID can also detect PPI-hot spots that lack direct contact with the partner protein or are in indirect contact [24] [26].

Q5: What file format should my protein structure be in for the FTMap server? FTMap requires a structure file in PDB format. You can either enter a four-digit PDB ID from the Protein Data Bank or upload your own PDB file. The server will remove all ligands, non-standard amino acid residues, and small molecules before mapping [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Recall (Sensitivity) with FTMap or SPOTONE

- Description: The tool fails to identify a large fraction of known true PPI-hot spots.

- Solution: Consider using PPI-hotspotID, which demonstrated a significantly higher recall (0.67) compared to FTMap (0.07) and SPOTONE (0.10) on a benchmark dataset [27]. For a further performance boost, you can combine PPI-hotspotID predictions with interface residues predicted by AlphaFold-Multimer [1] [26].

Problem: Interpreting FTMap Results for PPI Hot Spots

- Description: Uncertainty in how to translate FTMap's output into a set of predicted PPI-hot spot residues.

- Solution: When FTMap is run in PPI mode, the hot spots are identified as consensus sites—regions that bind multiple probe clusters. The residues considered as PPI-hot spots are those in van der Waals (vdW) contact with probe molecules within the largest consensus site (the one containing the most probe clusters) [24] [1].

Problem: "Incomplete" or "Misinterpreted" Validation in Methodology

- Description: Peer reviewers or readers raise concerns about the strength of evidence or validation of the hot spot prediction method, specifically regarding comparisons with other tools like FTMap.

- Solution: Ensure you understand and clearly communicate the fundamental differences between the tools. FTMap identifies regions that bind small molecular probes, which are often correlated with, but not identical to, the classic definition of PPI-hot spots based on binding free energy changes from alanine scanning [24]. When comparing methods, use a large, experimentally validated benchmark dataset and appropriate performance metrics like precision, recall, and F1-score [24] [27].

Performance Data for Key Prediction Tools

The following table summarizes the performance of PPI-hotspotID, FTMap, and SPOTONE on a benchmark dataset containing 414 true PPI-hot spots and 504 non-hot spots [27].

| Method | Input Required | Sensitivity (Recall) | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI-hotspotID | Free Protein Structure | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| FTMap | Free Protein Structure | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| SPOTONE | Protein Sequence | 0.10 | 0.17 |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Predicted PPI-Hot Spots

Title: Experimental Verification of Predicted PPI-Hot Spots Using Co-immunoprecipitation.

Background: This protocol describes a method to validate computationally predicted PPI-hot spots, as exemplified by the experimental verification of predictions for eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2) made by PPI-hotspotID [27] [1] [26].

Materials:

- Plasmids: Vectors (e.g., pcDNA3.1) encoding the wild-type protein and mutant versions (e.g., alanine substitutions) of the predicted hot spot residues.

- Cell Line: A relevant mammalian cell line (e.g., HEK293T) for protein expression.

- Antibodies: Antibody against the protein of interest for immunoprecipitation and antibody against its known binding partner for immunoblotting.

- Lysis Buffer: Non-denaturing cell lysis buffer (e.g., containing Tris-HCl pH 7.5, NaCl, NP-40, and protease inhibitors).

- Protein A/G Beads: For antibody immobilization during co-immunoprecipitation.

Procedure:

- Mutagenesis: Generate mutant constructs of the protein of interest where the predicted hot spot residues are substituted (e.g., with alanine).

- Transfection: Transfect the mammalian cell line with plasmids encoding the wild-type and mutant proteins.

- Cell Lysis: Harvest cells and lyse them in a non-denaturing lysis buffer to preserve protein-protein interactions.

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

- Incubate the cell lysates with an antibody specific to the protein of interest.

- Add Protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-protein complex.

- Wash the beads extensively with lysis buffer to remove non-specifically bound proteins.

- Immunoblotting (Western Blot)

- Elute the proteins from the beads by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer.

- Separate the proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer them to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- Probe the membrane with an antibody against the known binding partner.

- Analysis: A significant reduction or loss of the binding partner signal in the mutant samples compared to the wild-type sample confirms that the mutated residue is critical for the interaction, thus validating the prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| UniProtKB | Provides manually curated data on mutations that significantly impair/disrupt PPIs, used for building comprehensive training and benchmark datasets [27] [1]. |

| PPI-HotspotDB | A database containing thousands of experimentally determined PPI-hot spots, serving as a key resource for method development and validation [27] [26]. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Predicts the structure of protein-protein complexes and the residues located at the interface, which can be combined with other tools to improve hot spot prediction [1] [26]. |

| ASEdb / SKEMPI 2.0 | Energetic databases of mutations used for training and testing many PPI-hot spot prediction methods [27] [1]. |

Workflow Diagram: Integrating PPI-hotspotID and FTMap

Frequently Asked Questions

What is partner-independent hotspot identification and why is it important? Partner-independent hotspot identification refers to computational methods that can pinpoint key residues critical for protein-protein interactions using only the sequence or structure of a single protein, without requiring information about its binding partner. This capability is crucial for drug discovery as it allows researchers to identify potential therapeutic targets even when interaction partners are unknown or poorly characterized, significantly improving research specificity by focusing experimental efforts on the most promising regions [3].

My sequence-based predictor yields high accuracy on training data but performs poorly on my experimental validation. What could be wrong? This common issue often stems from data leakage due to sequence redundancy. If homologous proteins exist between your training and test sets, performance metrics become artificially inflated [28]. To resolve this:

- Apply sequence identity filtering (typically ≤25-35%) between training and test datasets [20] [28]

- Ensure any external tools used for feature generation (e.g., PSI-BLAST for PSSMs) were not trained on data homologous to your test set [28]

- Use clustering methods (e.g., 30% sequence identity clusters from RCSB) to ensure non-redundant dataset construction [29]

Which machine learning algorithm is best for sequence-based hotspot prediction? No single algorithm universally outperforms others, as the optimal choice depends on your specific dataset and features. Research shows various methods achieving success [20] [13]:

| Algorithm | Reported Performance | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 79% accuracy, 75% precision [30] | Sequence-frequency features [30] |

| Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) | 82.1% accuracy, MCC: 0.459 [20] | Hybrid spatial features [20] |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Superior performance in independent tests [13] | Large feature sets (26+ features) [13] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Competitive performance [20] | Various sequence and structure features [20] |

What are the most informative features for discriminating hotspot residues? While optimal features vary by method, these consistently rank as highly discriminative [3] [13]:

- Evolutionary conservation: Hotspots are significantly more conserved than non-hotspot residues [13]

- Amino acid type: Tryptophan (21%), arginine (13.1%), and tyrosine (12.3%) are disproportionately represented [13]

- Solvent accessibility: Hotspots often reside in structurally conserved, occluded regions [13]

- Structural neighborhood properties: Spatial arrangement of neighboring residues [20]

How reliable are current sequence-based methods compared to structure-based approaches? Sequence-based methods provide valuable insights when structures are unavailable, but have limitations [28]:

- Performance gap: Structure-based methods generally outperform sequence-based approaches when high-quality structures are available [28]

- Accuracy range: Modern sequence-based predictors achieve approximately 73-82% accuracy depending on methodology and dataset [30] [29] [20]

- Practical utility: For proteome-scale screening where structures are unknown, sequence methods offer the only feasible approach [31]

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Prediction Accuracy

Problem: Your model shows low precision or recall on independent validation sets.

Solution:

- Verify dataset quality and balance

- Implement rigorous feature selection

- Use minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) followed by sequential forward selection [13]

- Prioritize features with proven discriminative power (see Table 1)

- Avoid overfitting with cross-validation during feature selection

Validation Protocol:

Handling Class Imbalance

Problem: Hotspots are rare, leading to models biased toward non-hotspot prediction.

Solution Strategies:

- Ensemble methods with up-sampling: Methods like SpotOn successfully employ this approach [13]

- Cost-sensitive learning: Adjust algorithm weights to penalize misclassification of minority class [28]

- Synthetic data generation: Carefully apply techniques like SMOTE for limited augmentation

Performance Metrics Focus:

- Prioritize F1-score and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) over raw accuracy [13]

- Analyze precision-recall curves in addition to ROC curves [3]

- Report sensitivity specifically, as identifying true positives is often the primary goal [3]

Interpreting Evolutionary Conservation Signals

Problem: Conservation patterns are ambiguous or conflict with other features.

Analysis Framework:

- Calculate conservation using multiple methods (PSI-BLAST, hidden Markov models)

- Contextualize with structural data when available (hotspots often cluster in tightly packed regions) [20]

- Consider the "O-ring" theory: Hotspots may be surrounded by less important residues that occlude water [13]

Decision Matrix:

- High conservation + Buried residue → Strong hotspot candidate

- High conservation + Exposed residue → Likely functionally important but not necessarily interaction hotspot

- Low conservation + Structural centrality → Requires additional evidence from other features

Performance Comparison of Major Methodologies

The table below summarizes quantitative performance metrics for various hotspot prediction approaches:

| Method | Input Data | Accuracy | Precision | Sensitivity/Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-frequency features + Random Forest [30] | Sequence | 79% | 75% | N/A | N/A |

| Digital signal processing features [30] | Sequence | 79% | 75% | N/A | N/A |

| Combined with structural features [30] | Sequence + Structure | 82% | 80% | N/A | N/A |

| Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) [20] | Hybrid features | 82.1% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| ELM (Independent test) [20] | Hybrid features | 76.8% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HotspotPred [29] | Structure | 73% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| PPI-HotspotID [3] | Free protein structure | N/A | N/A | 0.67 | 0.71 |

Experimental Protocols

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis Validation

Purpose: Experimental validation of predicted hotspots by measuring binding energy changes.

Procedure:

- Site-directed mutagenesis: Substitute predicted hotspot residues with alanine

- Protein expression and purification: Express wild-type and mutant proteins

- Binding affinity measurement: Use surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

- Energy change calculation: Compute ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol indicates a true hotspot [13]

Interpretation:

- Strong confirmation: ΔΔG ≥ 2.0 kcal/mol upon alanine mutation

- Consider broader definition: Some resources (UniProtKB) include mutations that significantly impair/disrupt PPIs beyond just alanine [3]

Sequence-Based Prediction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a standardized workflow for sequence-based hotspot prediction:

Feature Selection Methodology

Two-Step Feature Selection Protocol [13]:

Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR):

- Rank all features by their discriminative power

- Select top candidates while minimizing inter-feature correlation

Sequential Forward Selection (SFS):

- Start with three top-ranked features from mRMR

- Iteratively add features that maximize prediction performance

- Stop when performance plateaus (typically at 20-30 features) [13]

Evaluation Metric:

- Use cross-validated performance with ranking criterion Rc [13]

- Focus on F1-score and MCC for class-imbalanced data [13]

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASEdb | Database | Experimental alanine scanning energetics data | Alanine Scanning Energetics Database [20] [13] |

| SKEMPI 2.0 | Database | Structural, kinetic and energetic mutation data | SKEMPI database [29] [13] |

| PPI-HotspotDB | Database | Comprehensive experimentally determined hotspots | PPI-HotspotDB [3] |

| BID | Database | Binding interface database for independent testing | Binding Interface Database [20] [13] |

| Robetta | Software | Energy-based hotspot prediction | Robetta server [20] [13] |

| FOLDEF | Software | Empirical free energy function calculation | FoldX suite [20] [13] |

| SPOTONE | Web server | Sequence-based prediction with extremely randomized trees | SPOTONE web server [3] |

| Hotpoint | Web server | Conservation and solvent accessibility-based prediction | Hotpoint server [20] |

| KFC2 | Web server | Knowledge-based FADE and Contacts method | KFC2 server [20] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software | Protein complex structure prediction for interface identification | AlphaFold-Multimer [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using the Min-SDS densest subgraph method over previous graph-based approaches for hot spot prediction?

Answer: The primary advantage of Min-SDS is its significantly higher recall while maintaining robust performance. Traditional graph theory-based methods often struggle to identify a comprehensive set of potential hot spots, typically achieving a recall of less than 0.400. In contrast, Min-SDS achieves an average recall of over 0.665, allowing researchers to capture a much larger fraction of true positive hot spot residues, which is crucial for understanding complete interaction mechanisms [32].

- Troubleshooting Note: If your results show a high rate of false positives, consider integrating the Min-SDS output with other residue features like evolutionary conservation or energy terms to refine the predictions, as done in other methods like PPI-hotspotID [3].

FAQ 2: Our residue interaction network (RIN) is built from a computational model (e.g., AlphaFold-Multimer). Is Min-SDS still applicable?

Answer: Yes. The Min-SDS method is designed to work with a single residue interaction network, irrespective of whether it is derived from experimental structures or computational models. This is a key strength, as it mitigates the shortage of wet-lab experimental complex structures [32]. For optimal results, ensure your computational model is of high quality.

- Troubleshooting Note: If predictions from a computational model seem unreliable, validate the underlying RIN. Compare the network's topology (e.g., average degree, connected components) against RINs built from high-resolution crystal structures to identify potential anomalies in the model.

FAQ 3: What are the most common reasons for a densest subgraph analysis failing to identify known hot spots?

Answer: Failure typically stems from issues in the initial RIN construction:

- Incomplete Network: The RIN may lack critical residues or interactions. Solution: Re-check the parameters used to define an atomic contact or interaction when building the network.

- Low Graph Connectivity: If the interface is not well-represented as a connected subgraph, the algorithm may not find a meaningful cluster. Solution: Experiment with different distance cutoffs for defining residue interactions to improve connectivity without introducing excessive noise [32].

- Data Quality: The underlying protein structure (experimental or predicted) may have inaccuracies in the region of the interface.

FAQ 4: How can we handle the trade-off between recall (sensitivity) and precision in a practical drug discovery setting?

Answer: In early-stage discovery, high recall is often preferred to ensure no potential hot spot is missed for further experimental validation. Min-SDS excels here. For later-stage, cost-intensive experiments like alanine scanning, you may need higher precision. To improve precision:

- Post-filtering: Filter the Min-SDS output residues by high conservation scores or computed binding energy contributions [33] [3].

- Integration: Use Min-SDS as a primary screen and integrate its results with methods like PPI-hotspotID or FTMap, which may have higher precision but lower recall on their own [3].

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and methodological comparisons for hot spot prediction.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Graph-Based Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Average Recall | Average F-Score | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min-SDS | Finds subgraphs with high average degrees (density) [32] | > 0.665 | > 0.364 (f2-score) | Data Not Specified |

| Previous Graph Methods | Varied network analysis techniques [32] | < 0.400 | < 0.224 (f2-score) | Data Not Specified |

| PPI-hotspotID | Machine learning on conservation, SASA, aa type, and energy [3] | 0.67 (Sensitivity) | 0.71 (F1-score) | Data Not Specified |

| FTMap (PPI mode) | Identifies consensus binding sites with probe molecules [3] | 0.07 (Sensitivity) | 0.13 (F1-score) | Data Not Specified |

| SPOTONE | Ensemble of extremely randomized trees using sequence features [3] | 0.10 (Sensitivity) | 0.17 (F1-score) | Data Not Specified |

Table 2: Key Databases for Hot Spot Research

| Database Name | Description | Key Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SKEMPI 2.0 | A database containing binding free energy changes for mutations at protein-protein interfaces [32] | Primary benchmark dataset for training and validating prediction methods. |

| ASEdb (Alanine Scanning Energetics db) | Database of free energy changes upon alanine mutations [33] [3] | Foundational dataset for defining and studying hot spots. |

| PPI-HotspotDB | An expanded database incorporating data from UniProtKB for impaired/disrupting mutations [3] | Provides a larger, more diverse set of experimentally determined hot spots for robust method calibration. |

Experimental Protocol: Min-SDS Workflow for Hot Spot Prediction

This section provides a detailed step-by-step protocol for implementing the Min-SDS method.

Objective: To identify key residue clusters (hot spots) in a protein-protein interface from a 3D structure using the Min-SDS densest subgraph algorithm.

Input: The atomic coordinate file (e.g., PDB format) of a protein-protein complex.

Methodology:

Residue Interaction Network (RIN) Construction

- Software Requirement: A RIN builder (e.g., NAPS, RING, or a custom script).

- Procedure:

- Parse the input PDB file.

- Represent each amino acid residue as a node in the graph.

- Define an edge between two nodes if any of their heavy atoms are within a specified distance cutoff (typically 4.5 - 5.0 Å).

- The output is an undirected graph, G = (V, E), where V is the set of residues and E is the set of interactions.

Application of the Min-SDS Algorithm

- Algorithm Core: The goal is to find a subgraph S that maximizes the average degree, density = |E(S)| / |S|, where E(S) are the edges within S.

- Implementation: The Min-SDS method uses linear programming to solve this problem efficiently [32].

- Software: Implement the algorithm using a programming language like Python with graph libraries (e.g., NetworkX) and a linear programming solver.

Extraction and Interpretation of Results

- The output of the Min-SDS algorithm is a set of nodes (residues) forming the densest subgraph.

- This cluster of residues is predicted to be the hot spot region critical for the protein-protein interaction.

- Validation: Compare the predicted residues against experimental alanine scanning data from databases like SKEMPI or ASEdb, if available.

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Datasets

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Use in Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of atomic coordinate files for building the initial Residue Interaction Network (RIN). |

| Residue Interaction Network (RIN) Builder | Software (e.g., NAPS) that converts a 3D structure into a graph of interacting residues. | Creates the foundational network graph required for all subsequent densest subgraph analysis. |

| Linear Programming Solver | A computational library (e.g., PuLP in Python, Gurobi) that solves optimization problems. | Core computational engine for executing the Min-SDS algorithm to find the densest subgraph. |

| SKEMPI / ASEdb / PPI-HotspotDB | Curated databases of experimental hot spot and binding energy data. | Used as benchmark datasets to validate and calibrate the predictions made by the Min-SDS method. |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | AI system that predicts the 3D structure of multi-protein complexes. | Provides computational structural models for RIN construction when experimental complex structures are unavailable. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common pitfalls when using AlphaFold-Multimer's ipTM score to identify potential interfaces, and how can I avoid them?

A primary pitfall is the misinterpretation of the ipTM score when using full-length protein sequences. The ipTM score is calculated over entire chains, and the presence of large disordered regions or accessory domains that do not participate in the core interaction can artificially lower the score, even if the domain-domain interaction is predicted accurately [34]. To avoid this:

- Use Domain-Informed Constructs: Whenever possible, define and use sequence constructs that contain only the putative interacting domains, rather than full-length sequences [34] [35].

- Employ Alternative Metrics: For full-length predictions, use the ipSAE score or interface pDockQ, which focus analysis on the interfacial residue pairs and are less sensitive to non-interacting regions [34].

- Cross-Reference Biological Data: Never rely on ipTM alone. Always check predicted interfaces against known biological data from interaction databases like BioGRID and literature to assess plausibility [35].

FAQ 2: My AlphaFold-Multimer model shows a high-quality interface, but subsequent alanine scanning does not confirm hot spots. What could be wrong?

AlphaFold models can exhibit major inconsistencies in key interfacial details, even when the overall global accuracy metrics (like DockQ) appear high. Common inaccuracies include incorrect intermolecular polar interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds) and flawed apolar-apolar packing [36]. These compact but inaccurate interfaces lack the specific stabilizing interactions that define true energetic hot spots.

- Always Refine and Validate: Use molecular mechanics energy minimization or short molecular dynamics simulations to relax the predicted complex. This can relieve atomic clashes and improve side-chain packing [36].

- Conformational Sampling: Be aware that a single AlphaFold prediction is a static snapshot. For proteins with flexible interfaces, consider methods that sample conformational ensembles to better understand the interaction landscape [37].

- Prioritize with Complementary Tools: Use the AlphaFold-predicted interface as a scaffold for dedicated hot spot prediction tools like PPI-hotspotID or energy-based methods like FoldX, which are specifically designed to evaluate energetic contributions [27] [35].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the specificity of my hot spot predictions when I only have a free protein structure?

Many powerful hot spot prediction methods require the structure of the bound complex. When only the free (unbound) protein structure is available, you can use a combination of interface prediction and dedicated free-structure classifiers.

- Predict the Interface First: Run AlphaFold-Multimer to generate a model of the complex and identify the interface residues [27].

- Apply a Free-Structure Classifier: Use a tool like PPI-hotspotID, which is specifically trained on free protein structures. It uses an ensemble of classifiers with features including conservation, amino acid type, solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), and gas-phase energy (ΔGgas) to identify hot spots [27].

- Combine the Outputs: The combination of AlphaFold-Multimer-predicted interface residues and PPI-hotspotID analysis has been shown to yield better performance than either method alone [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Confidence in Predicted Protein-Protein Interface

Problem: AlphaFold-Multimer returns a model with a low ipTM score, creating uncertainty about whether the proteins interact.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify your sequence constructs are optimal by removing long disordered regions and non-interacting accessory domains. Check with predictors like IUPred2. | This is the most critical step. Shorter constructs containing only interacting domains often yield significantly higher and more reliable ipTM scores [34] [35]. |

| 2 | Re-run AlphaFold-Multimer with the optimized constructs. | This directly addresses the primary cause of artificially low ipTM scores. |

| 3 | Calculate alternative interface confidence metrics from the original model, such as ipSAE or pDockQ. | These metrics focus on the interface itself and are less biased by chain length and disordered regions, providing a more accurate assessment of interface quality [34]. |

| 4 | Perform a literature and database search (e.g., BioGRID, String) for experimental evidence of the interaction. | Independent biological evidence is crucial for validating a computationally predicted interface. A low-confidence prediction without biological support should be treated with skepticism [35]. |

Issue 2: High-Ranking AlphaFold Model Fails to Identify Known Hot Spots

Problem: The predicted complex structure appears plausible, but computational alanine scanning of the model does not recover experimentally validated hot spot residues.