Integrating WGCNA and Machine Learning for Sepsis-Induced ARDS Biomarker Discovery: From Computational Pipelines to Clinical Translation

Sepsis-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening complication with high mortality rates, necessitating early diagnosis and intervention.

Integrating WGCNA and Machine Learning for Sepsis-Induced ARDS Biomarker Discovery: From Computational Pipelines to Clinical Translation

Abstract

Sepsis-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening complication with high mortality rates, necessitating early diagnosis and intervention. This article explores the integrated application of Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) and machine learning algorithms for identifying robust diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. We systematically review foundational concepts, methodological frameworks, and optimization strategies for analyzing high-dimensional transcriptomic data from public repositories like GEO. The content covers experimental validation approaches, immune infiltration analysis, and comparative assessment of machine learning algorithms including SVM-RFE, Random Forest, and LASSO regression. By synthesizing recent research findings, we provide researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive insights into developing clinically applicable biomarkers and therapeutic targets for sepsis-induced ARDS, ultimately aiming to improve patient outcomes through precision medicine approaches.

Understanding Sepsis-Induced ARDS Pathobiology and Computational Discovery Frameworks

The Clinical Burden and Molecular Complexity of Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) represents a formidable challenge in critical care medicine, characterized by a high mortality rate of 30-40% and a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide [1] [2]. As a prevalent complication of sepsis, it affects approximately 25-50% of all sepsis patients, significantly prolonging intensive care unit stays and increasing ventilator dependence [1]. The molecular complexity of this condition stems from dysregulated host responses to infection that trigger diffuse alveolar damage, uncontrolled inflammatory cascades, and profound disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier [1] [2]. Despite advances in understanding its pathophysiology, the absence of targeted pharmacologic therapies has maintained sepsis-induced ARDS as a focus of intense research, particularly in the realm of biomarker discovery and personalized treatment approaches [3] [4].

In recent years, the integration of advanced computational biology techniques, especially weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) and machine learning algorithms, has revolutionized our approach to deciphering the molecular heterogeneity of sepsis-induced ARDS [5] [6]. These methods enable researchers to move beyond traditional single-biomarker approaches toward comprehensive molecular subphenotyping, offering new avenues for early diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and targeted therapeutic intervention [5] [7]. This review systematically examines the current landscape of sepsis-induced ARDS research, with particular emphasis on how WGCNA and machine learning methodologies are transforming our understanding of its complex molecular architecture and creating opportunities for precision medicine in critical care.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms: A Complex Molecular Cascade

The development of sepsis-induced ARDS involves intricate interactions between inflammatory injury, immune dysregulation, coagulation disturbances, and their respective signaling pathways [1]. When pathogens invade the lungs or trigger a systemic inflammatory response from extrapulmonary sites, they initiate antigen recognition, presentation, and immune activation, thereby activating inflammatory signaling cascades [1]. This process leads to the massive infiltration of inflammatory mediators including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, chemokines, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, which promote immune cell recruitment and uncontrolled inflammatory responses in the pulmonary environment [1].

Central Pathogenic Processes in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Alveolar-Capillary Barrier Disruption: Activated neutrophils and inflammatory factors contribute to the necrosis of alveolar epithelial and vascular endothelial cells, accompanied by disruptions in alveolar surfactants. These events increase permeability of pulmonary epithelium and vascular endothelium, causing protein leakage and alveolar and interstitial edema that amplify pro-inflammatory signals [1] [2]. The integrity of the alveolar-capillary barrier is further compromised by the dissociation of VE-cadherin and endothelial receptor kinase (TIE2), which is regulated by VE protein tyrosine phosphatase [2].

Coagulation Abnormalities: Damage to and activation of vascular endothelial cells expose coagulation factors on the endothelial surface. Simultaneously, leukocytes release microvesicles and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) that activate procoagulant substances including tissue factors and platelet-activating factors, initiating the exogenous coagulation cascade and promoting microvascular thrombosis [1]. This process increases pulmonary vascular dead space and is associated with poor prognosis in sepsis-induced ARDS [1].

Oxidative Stress and Cell Death Pathways: Activated alveolar macrophages and multinucleated leukocytes release abundant reactive oxygen species and oxidized molecules. Oxidative stress results in lipid peroxidation of cell membranes and accumulation of oxidized proteins, further exacerbating alveolar cell apoptosis [1] [2]. Multiple cell death pathways including apoptosis, necroptosis, and pyroptosis contribute to the pathogenesis through mechanisms involving caspase activation, Gasdermin D cleavage, and HMGB1 release [2].

The resulting clinical manifestations include interstitial and alveolar edema, reduced lung volume, increased lung elasticity, decreased compliance, and elevated respiratory work [1]. Diffuse alveolar filling leads to a severe imbalance in the ventilation/perfusion ratio, pulmonary diffusion dysfunction, bilateral diffuse shadowing on imaging, and refractory hypoxemia that characterizes the clinical presentation of sepsis-induced ARDS [1].

WGCNA and Machine Learning: Analytical Frameworks for Biomarker Discovery

Fundamental Methodological Approaches

The application of WGCNA and machine learning algorithms has emerged as a powerful integrative approach for identifying robust diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in sepsis-induced ARDS. WGCNA operates by constructing a scale-free co-expression network where genes are grouped into modules based on their expression patterns across samples [5] [6]. This method identifies clusters of highly correlated genes that may represent functional relationships or shared regulatory mechanisms, with these modules then tested for associations with clinical traits or phenotypes of interest [6] [8]. The key advantage of WGCNA lies in its ability to move beyond single-gene analyses to capture the complex network structure of biological systems, making it particularly suited for heterogeneous conditions like sepsis-induced ARDS.

Machine learning algorithms complement WGCNA by providing powerful feature selection and classification capabilities. Commonly employed techniques include support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE), random forest (RF), artificial neural networks (ANN), and logistic regression [5] [6]. These methods excel at identifying optimal gene subsets with the highest predictive power for distinguishing disease states or outcomes, while effectively handling high-dimensional data where the number of features far exceeds the number of observations [5]. The integration of these computational approaches has proven particularly valuable for parsing the molecular heterogeneity of sepsis-induced ARDS and identifying clinically relevant subphenotypes with distinct therapeutic implications [5] [7].

Experimental Workflows and Validation Pipelines

A standardized bioinformatics workflow for sepsis-induced ARDS biomarker discovery typically begins with data acquisition from public repositories such as the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), followed by quality control, normalization, and batch effect correction [5] [6] [8]. WGCNA is then employed to identify gene modules significantly associated with sepsis-induced ARDS, with modules of interest selected based on correlation coefficients with clinical traits or immune cell infiltration patterns [6] [8]. These module genes are intersected with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified using packages like Limma, applying thresholds such as |log2-fold change| > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 [5] [8].

Machine learning algorithms are subsequently applied for feature selection, with SVM-RFE and random forest being particularly effective for identifying minimal gene sets with maximal diagnostic accuracy [5] [6]. The resulting candidate biomarkers undergo rigorous validation using external datasets, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to assess diagnostic performance, and experimental validation through in vitro models such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells or A549 alveolar epithelial cells [5] [6] [9]. Functional enrichment analyses including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis provide biological context for the identified gene sets, while immune infiltration analysis using tools like CIBERSORT reveals relationships between biomarker expression and immune cell populations [5] [6].

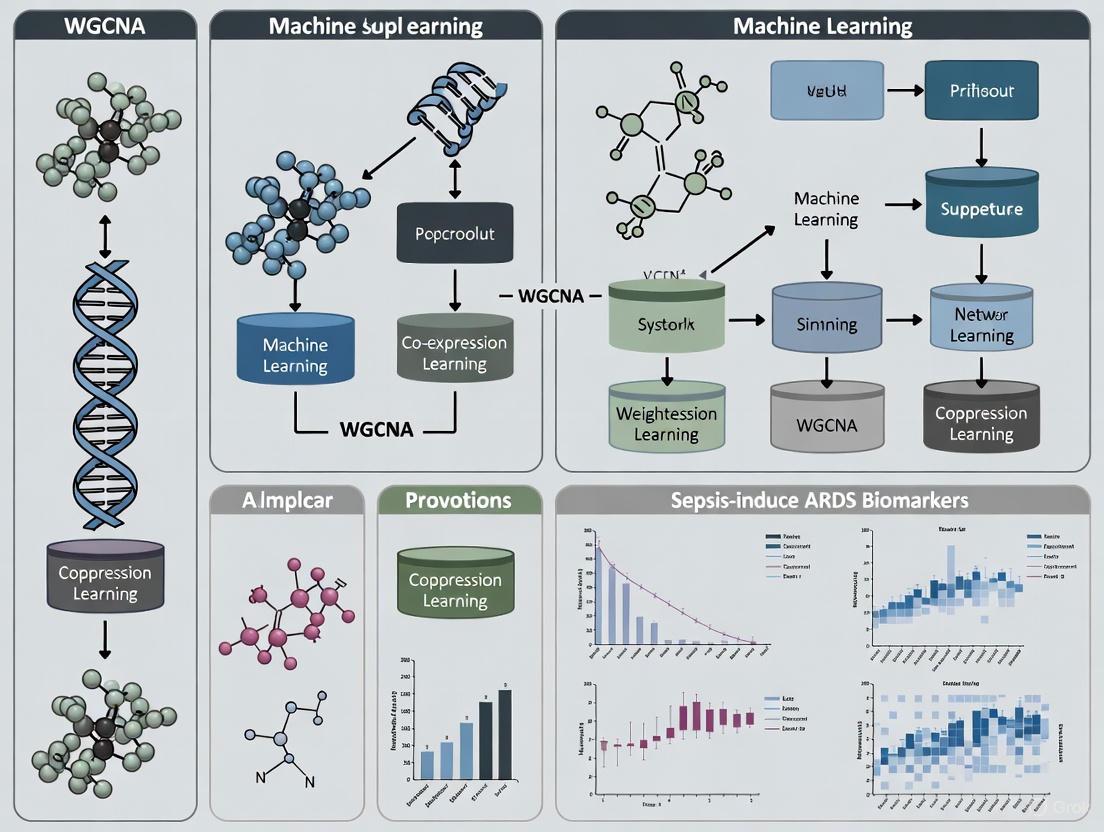

Figure 1: Integrated Bioinformatics Workflow for Sepsis-Induced ARDS Biomarker Discovery

Key Biomarker Discoveries: From Transcriptomics to Clinical Application

Promising Biomarker Panels from Recent Studies

Recent applications of WGCNA and machine learning have yielded several promising biomarker panels for sepsis-induced ARDS. A 2023 study employing WGCNA and machine learning identified three macrophage-related key genes (SGK1, DYSF, and MSRB1) with significant diagnostic potential, all demonstrating area under the curve (AUC) values >0.7 in ROC analysis [6]. Another investigation published in 2025 applied similar methodologies to identify five key genes (LCN2, AIF1L, STAT3, SOCS3, and SDHD) as shared diagnostic markers for both sepsis-induced ARDS and sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy, with SOCS3 emerging as a particularly promising hub gene and therapeutic target [5]. These findings highlight the potential of computational approaches to identify biomarkers with utility across multiple sepsis-related organ dysfunctions.

Research has also revealed autophagy-related genes as significant players in sepsis-induced ARDS pathogenesis. A 2025 study identified 18 autophagy-related differentially expressed genes with diagnostic potential, all demonstrating AUC > 0.6 in ROC curve analysis [8]. The top upregulated genes included EXT1, COL9A2, RNF10, MAOA, and TMCC2, while the most significantly downregulated genes were CCL5, CX3CR1, F13A1, M6PR, and CDK2AP1 [8]. These autophagy-related biomarkers were linked to critical pathways including apoptosis, complement activation, IL-2/STAT5 signaling, and KRAS signaling, providing insight into potential mechanistic roles in disease progression [8].

Comparative Analysis of Biomarker Performance

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Recently Identified Biomarker Panels for Sepsis-Induced ARDS

| Biomarker Category | Key Identified Genes | Diagnostic Performance (AUC) | Biological Functions | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrophage-Related | SGK1, DYSF, MSRB1 | >0.7 | Immune regulation, oxidative stress response, cell membrane repair | [6] |

| Multi-Organ Injury | LCN2, AIF1L, STAT3, SOCS3, SDHD | SOCS3 showed strong diagnostic potential | Iron homeostasis, immune response, JAK-STAT signaling, mitochondrial function | [5] |

| Autophagy-Related | EXT1, COL9A2, RNF10, CCL5, CX3CR1 | >0.6 for all 18 identified genes | Extracellular matrix organization, chemotaxis, immune cell recruitment | [8] |

| Immune-Related | GYPE, HSPB1, CD81, RPL22 | Varied performance across genes | Erythrocyte function, stress response, immune regulation, ribosomal function | [9] |

| Clinical Biomarker Panel | RAGE, CXCL16, Ang-2, PaO2/FiO2 | 0.88 | Epithelial injury (RAGE), endothelial injury (Ang-2), chemotaxis (CXCL16) | [10] |

The integration of clinical parameters with biomarker panels has demonstrated particularly strong diagnostic performance. A 2021 study combining the biomarkers RAGE, CXCL16, and Ang-2 with the PaO2/FiO2 ratio achieved an impressive AUC of 0.88 for predicting ARDS development in septic patients [10]. This finding underscores the value of combining molecular biomarkers with readily available clinical parameters to enhance predictive accuracy and clinical utility.

Molecular Subphenotypes: Toward Precision Medicine in ARDS

Heterogeneity in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

The considerable heterogeneity in clinical presentation and treatment response among sepsis-induced ARDS patients has driven research efforts to identify molecularly distinct subphenotypes [1] [7]. The hyperinflammatory subphenotype, characterized by significantly elevated serum levels of IL-8, tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 (TNFr1), and decreased bicarbonate levels, requires more vasopressor support and demonstrates differential response to fluid management strategies [1]. Notably, this subphenotype exhibited a lower 90-day mortality rate when assigned to a fluid-conservative strategy compared to a fluid-liberal approach (40% vs. 50%) in the FACTT study, highlighting the potential clinical impact of subphenotype identification [1] [7].

Beyond inflammatory markers, subphenotypes may also be distinguished by patterns of immune cell infiltration and activation. Analyses using CIBERSORT and ssGSEA have revealed significant alterations in immune landscapes, with hyperinflammatory subphenotypes typically showing increased infiltration of monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells [6] [8]. These immune patterns correlate with specific gene expression signatures and may have implications for both prognosis and treatment selection, particularly as immunomodulatory therapies continue to be investigated for sepsis and ARDS [7] [6].

Signaling Pathways in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Figure 2: Key Pathogenic Signaling Pathways in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Experimental Investigation

Critical Reagents and Their Applications

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Sepsis-Induced ARDS Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Models | HPMECs, A549, Beas-2B | In vitro injury modeling, mechanistic studies, drug screening | HPMECs for endothelial barrier function; A549 and Beas-2B for epithelial responses |

| Induction Agents | Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Experimental injury induction, inflammation modeling | TLR4 activation, cytokine release, barrier disruption |

| Analysis Kits | DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems) | Protein biomarker quantification | Measure RAGE, Ang-2, IL-1RA, SP-D, ICAM-1, others |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Limma, WGCNA, clusterProfiler | Differential expression, co-expression networks, pathway analysis | Statistical analysis, module identification, functional enrichment |

| Machine Learning Packages | e1071, kernlab, randomForest | Feature selection, classification, model building | SVM-RFE, random forest, neural network implementation |

| Immune Infiltration Tools | CIBERSORT, ssGSEA | Immune landscape characterization | Quantify immune cell subsets from transcriptomic data |

The selection of appropriate research reagents is critical for rigorous investigation of sepsis-induced ARDS mechanisms and biomarker validation. Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs) serve as invaluable tools for studying endothelial barrier function and its disruption during sepsis-induced lung injury [5]. Similarly, A549 and Beas-2B cell lines provide relevant models for alveolar epithelial responses, particularly when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to mimic infectious insults [9] [8]. LPS itself represents a cornerstone reagent for experimental modeling, reliably inducing inflammatory responses and cellular injury patterns that recapitulate key aspects of sepsis-induced ARDS pathophysiology [8] [2].

For biomarker quantification, commercially available DuoSet ELISA kits enable accurate measurement of protein biomarkers including RAGE, Ang-2, IL-1RA, SP-D, and ICAM-1 in patient serum or plasma samples [10]. These measurements facilitate correlation with clinical outcomes and validation of transcriptomic findings at the protein level. Bioinformatics packages including Limma for differential expression analysis, WGCNA for co-expression network construction, and clusterProfiler for functional enrichment analysis form the computational backbone of modern biomarker discovery pipelines [5] [6] [8]. These are complemented by machine learning packages such as e1071, kernlab, and randomForest that enable sophisticated feature selection and classification model development [5] [6].

The integration of WGCNA and machine learning approaches has fundamentally advanced our understanding of sepsis-induced ARDS, revealing complex molecular networks and promising biomarker candidates with genuine diagnostic and therapeutic potential. The identification of distinct molecular subphenotypes represents a particularly significant advancement, offering a path toward personalized treatment strategies for this notoriously heterogeneous condition [1] [5] [7]. As these computational methodologies continue to evolve, their integration with multi-omics data, electronic health records, and real-time clinical monitoring systems holds promise for developing dynamic, precision medicine approaches that can adapt to changing patient states throughout the clinical course of sepsis-induced ARDS.

Despite these promising developments, significant challenges remain in translating computational findings into clinically actionable tools. Future research directions should prioritize validation of identified biomarkers in large, prospective, multi-center cohorts, with careful attention to standardization of measurement techniques and establishment of clinically relevant cutoff values [5] [10]. Additionally, greater emphasis on functional characterization of candidate biomarkers will be essential for distinguishing mere associations from genuine pathogenic mechanisms that might serve as therapeutic targets [6] [9]. As these efforts progress, the ongoing refinement of WGCNA and machine learning methodologies promises to further unravel the clinical burden and molecular complexity of sepsis-induced ARDS, ultimately contributing to improved outcomes for this devastating condition.

In the field of bioinformatics, particularly for complex research areas like identifying biomarkers for sepsis-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), the selection of appropriate databases is crucial. This guide provides an objective comparison of three essential resources: the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the Immunology Database and Analysis Portal (ImmPort), and the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB). With the integration of Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) and machine learning becoming a standard approach in biomarker discovery, understanding the specific strengths, applications, and data structures of these databases is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This article frames the comparison within the context of a broader thesis on leveraging WGCNA and machine learning for sepsis-induced ARDS biomarkers research, providing experimental data and protocols to illustrate their practical utility.

Database Comparison and Specifications

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and typical applications of GEO, ImmPort, and MSigDB in the context of sepsis and ARDS research.

Table 1: Core Database Specifications and Research Applications

| Feature | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) | Immunology Database and Analysis Portal (ImmPort) | Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Public repository for high-throughput functional genomics data [11] [12] | Data sharing and analysis portal for immunology research [13] | Collection of annotated gene sets for gene set enrichment analysis [14] |

| Data Types | Gene expression, epigenomics, non-coding RNA profiles [11] | Cell counts, cytokine concentrations, immune response measures [13] | Gene sets representing pathways, targets, immunologic signatures [14] |

| Role in Sepsis/ARDS Research | Source for DEG identification; training data for machine learning models [11] [12] | Provides immune-specific gene lists; enables immune infiltration analysis via CIBERSORT [11] [12] [13] | Provides background for functional enrichment (GO, KEGG); pathway analysis [11] [12] |

| Key Application in ML/WGCNA Pipeline | Identifies co-expression modules and DEGs for model feature selection [11] | Correlates immune cell abundance with gene modules and clinical traits [12] [13] | Interprets biological meaning of WGCNA modules and model-predicted genes [11] |

| Representative Dataset Examples | GSE10474, GSE32707 (sepsis-induced ALI) [11] | ImmPort:SF00 (shared flow cytometry data) | M7: Immunologic Signatures (mouse) [14] |

Experimental Data and Performance in Sepsis-Induced ARDS Research

The utility of these databases is best demonstrated through real-world experimental workflows. The following table quantifies the output from a typical integrated analysis for sepsis biomarker discovery.

Table 2: Experimental Output from a Combined GEO, ImmPort, and MSigDB Workflow

| Analysis Stage | Input Data & Resources | Output Metrics | Reported Performance/Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEG Identification | GEO datasets (GSE10474, GSE32707, GSE66890) [11] | 213 candidate genes identified (intersection of DEGs and WGCNA modules) [11] | Threshold: |log2FC| > 0.6, FDR < 0.05 [11] |

| WGCNA & Immune Correlation | WGCNA modules; Immune cell abundances from ImmPort/CIBERSORT [11] [12] | Key module (e.g., MEblue) significantly correlated with clinical traits and immune cell fractions [11] | Identification of 213 genes associated with immune activation and bacterial infection [11] |

| Machine Learning Model Training | Candidate genes from GEO and WGCNA as features [11] [12] | Four key diagnostic genes (DDAH2, PNPLA2, STXBP2, TCN1) selected by multiple algorithms [11] | Model AUCs: Validated on external GEO datasets (GSE10361, GSE3037) [11] |

| Functional Enrichment Analysis | Hub genes analyzed against MSigDB gene sets (GO, KEGG) [11] [12] | Significant enrichment in immune and sepsis-relevant pathways (e.g., TGF-β signaling, NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity) [11] [13] | Provides biological plausibility for identified biomarker genes [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Data Acquisition and Preprocessing for Multi-Database Analysis

This protocol outlines the initial steps for gathering and standardizing data from GEO, a foundational step for any subsequent WGCNA or machine learning analysis.

- Dataset Identification: Query the GEO database using relevant keywords (e.g., "sepsis-induced acute lung injury," "sepsis," "Homo sapiens") [11] [12].

- Inclusion Criteria: Select datasets based on predefined criteria, such as organism, sample size (e.g., >12 per group), and tissue type (e.g., whole blood or relevant tissue) [12].

- Data Download: Retrieve raw data files (e.g., CEL files for microarray) and corresponding platform annotation files.

- Normalization and Batch Correction: Perform background correction and normalization (e.g., RMA for microarray data) using packages like

affy[15]. Use thesvaR package or theremoveBatchEffectfunction from thelimmapackage to merge multiple datasets and correct for batch effects [11] [12] [15]. - DEG Identification: Using the

limmapackage, identify DEGs between sepsis-induced ARDS and control samples. Standard thresholds are \|log2FC\| > 0.6 or 1.0 and an adjusted P-value or FDR < 0.05 [11] [12] [15].

Protocol 2: Integrated WGCNA and Immune Analysis

This protocol describes how to integrate co-expression analysis with immunology-focused data resources.

- WGCNA Network Construction: Using the normalized expression matrix from GEO, construct a weighted co-expression network using the

WGCNAR package. Choose a soft-thresholding power that ensures a scale-free topology [11] [12]. - Module Detection and Trait Association: Identify modules of highly correlated genes using dynamic tree cutting. Correlate module eigengenes (MEs) with external clinical traits (e.g., sepsis severity, ARDS status) [11] [12].

- Immune Infiltration Analysis: Use the CIBERSORT algorithm and reference gene sets (which can be sourced or complemented by ImmPort's immune-related gene lists) to deconvolute the immune cell composition from the bulk gene expression data of each sample [11] [12] [13].

- Integration: Correlate module eigengenes or hub gene expression with the estimated abundances of specific immune cell types (e.g., neutrophils, monocytes) to identify immune-related gene modules [11] [12].

Protocol 3: Machine Learning Feature Selection and Validation

This protocol leverages the outputs from previous steps to build a diagnostic model.

- Feature Preparation: Use the overlapping genes between DEGs and key WGCNA modules as the initial feature pool [11].

- Model Training and Feature Selection: Apply multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO)) to the training set. Use the

randomForest,glmnet, ande1071packages in R. Genes identified as important by at least three different algorithms are selected as hub genes [11] [12]. - Model Validation: Validate the diagnostic model's performance using independent external validation datasets from GEO (e.g., GSE10361, GSE3037). Evaluate using metrics like the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC), calibration curves, and Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) [11].

- Biological Interpretation: Perform functional enrichment analysis on the final hub genes using MSigDB collections (e.g., GO, KEGG, immunologic signatures) via the

clusterProfilerR package to interpret their biological roles in sepsis-induced ARDS [11] [14] [12].

The following table lists key computational tools and resources used in the featured experiments for sepsis biomarker discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function | Example in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

R limma package [11] [12] [15] |

Statistical Analysis | Differential expression analysis for microarray/RNA-seq data. | Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between sepsis patients and controls from GEO data. |

R WGCNA package [11] [12] |

Network Analysis | Constructs weighted co-expression networks to find modules of correlated genes. | Identify gene modules significantly associated with sepsis-induced ARDS or immune cell infiltration. |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm [11] [12] | Cell Deconvolution | Estimates immune cell abundances from bulk tissue gene expression data. | Analyze immune cell infiltration patterns in sepsis, correlating with WGCNA modules or clinical outcomes. |

R clusterProfiler package [11] [12] |

Functional Enrichment | Statistical analysis and visualization of functional profiles of genes/gene clusters. | Perform GO and KEGG enrichment analysis on hub genes using MSigDB as a knowledge base. |

| LASSO & Random Forest [11] [12] [13] | Machine Learning | Feature selection and classification/prediction modeling. | Screen robust diagnostic biomarkers from a large pool of candidate genes derived from DEGs and WGCNA. |

| Molecular Docking Tools (AutoDock Vina) [11] | Validation | Predicts binding affinity between small molecules (drugs) and target proteins. | Validate interactions between potential therapeutic compounds (e.g., Resveratrol) and identified protein targets. |

GEO, ImmPort, and MSigDB are complementary pillars in the bioinformatics infrastructure for sepsis-induced ARDS research. GEO serves as the primary data source, ImmPort provides the immunological context, and MSigDB enables functional interpretation. When integrated within a WGCNA and machine learning pipeline, they form a powerful framework for transforming high-dimensional genomic data into biologically and clinically actionable insights, such as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The experimental data and protocols detailed herein provide a reproducible roadmap for researchers aiming to leverage these essential resources.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) is a powerful systems biology method designed to analyze complex correlation patterns in high-dimensional omics data, with its primary application in gene expression analysis [16] [17]. Unlike approaches that examine genes in isolation, WGCNA adopts a guilt-by-association principle, where information about a gene is inferred from its closely connected neighbors within the network [16]. This method allows researchers to identify clusters of genes—known as modules—that exhibit highly correlated expression patterns across samples, suggesting potential functional relationships, shared regulatory mechanisms, or involvement in common molecular pathways [16] [17].

The "weighted" aspect of WGCNA is a key differentiator, referring to the use of a soft-thresholding power (β) to amplify the difference between strong and weak correlations in the network [16] [17]. This approach preserves the continuous nature of co-expression information, in contrast to unweighted networks that apply a hard threshold to define gene connections [17]. Originally developed for transcriptomic data, WGCNA's principles are now successfully applied to other omics disciplines, including proteomics, metabolomics, and multi-omics integration studies [16] [18].

Core Methodology and Analytical Workflow

The WGCNA pipeline comprises four main sequential analytical components that transform raw expression data into biologically insightful networks [16].

Step 1: Construction of Weighted Correlation Networks

WGCNA begins with a gene expression matrix where rows represent genes and columns represent samples [17]. The method measures pairwise correlations between genes across all samples, with the correlation score indicating the similarity of their expression patterns [16]. The resulting co-expression similarity matrix (sij) is transformed into an adjacency matrix (aij) using a power function: aij = |cor(xi, x_j)|^β [17]. The selection of the soft-thresholding power β is crucial, as it determines the degree to which the network emphasizes strong correlations over weaker ones, with the goal of achieving a scale-free topology network [17] [18]. This topology characteristic means the network's connectivity distribution follows a power law, a property commonly observed in biological networks [18].

Step 2: Identification of Co-expression Modules

Next, WGCNA uses the adjacency matrix to identify groups of genes with highly similar expression profiles, termed modules [16]. This is achieved through hierarchical clustering of the topological overlap matrix (TOM), a derived measure that reflects the relative interconnectedness of each gene pair within the network [5] [18]. A dendrogram is generated where each branch represents a module of co-expressed genes [16]. Methods like dynamic tree cutting are employed to determine discrete modules from the dendrogram, with each module assigned a distinct color label [16] [5]. Proper parameter selection during this step is critical, as it directly influences module size, number, and biological accuracy [16].

Step 3: Correlation of Modules with Phenotypic Traits

Once modules are defined, WGCNA simplifies each module's expression profile into a single representative value called the module eigengene [16]. The module eigengene is calculated as the first principal component of the module's expression matrix and represents the predominant expression pattern of all genes within that module [16] [17]. This data reduction enables correlation analysis between modules to identify those with similar expression behaviors, and more importantly, to determine how each module correlates with external sample traits or phenotypes [16]. These biological variables can include clinical features such as disease status, patient survival, age, or any other measurable trait [16] [17].

Step 4: Identification of Potential Driver Genes

The final analytical step focuses on identifying hub genes within significant modules [16]. Hub genes are the most highly connected genes within a module and are typically strongly correlated with phenotypes of interest [16] [18]. The module membership (also known as KME) measures how closely a gene's expression aligns with the module eigengene, providing a useful metric for prioritizing genes for further functional validation [16]. These hub genes often represent candidate biomarkers or therapeutic targets due to their central positions within biologically relevant co-expression networks [16] [17].

Table 1: Key Outputs of WGCNA Analysis and Their Biological Interpretations

| Output | Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Modules | Clusters of highly correlated genes | Potential functional units or pathways |

| Module Eigengene | First principal component of module expression | Representative expression pattern for the entire module |

| Module-Trait Correlation | Association between module eigengene and sample phenotype | Relationship between gene cluster and biological trait |

| Hub Genes | Highly connected genes within modules | Potential key regulators or drivers of phenotypic traits |

| Module Membership | Correlation between gene expression and module eigengene | How well a gene represents the module's expression pattern |

WGCNA in Sepsis-Induced ARDS Biomarker Discovery

Application in ARDS Research

WGCNA has emerged as a powerful approach for elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying complex syndromes like sepsis-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) [19] [5]. In this context, researchers apply WGCNA to gene expression datasets from patient blood samples or relevant tissues to identify co-expression modules associated with disease progression, severity, or specific clinical features [19] [20]. For instance, studies have successfully identified modules highly correlated with immune cell infiltration patterns, particularly involving macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, which play crucial roles in ARDS pathophysiology [19]. These modules provide insights into the coordinated immune responses and inflammatory processes driving lung injury in sepsis-induced ARDS [19] [20].

Integration with Machine Learning Approaches

In contemporary biomarker discovery, WGCNA is frequently integrated with various machine learning algorithms to enhance the robustness and predictive power of identified biomarkers [19] [5]. This integrated approach typically involves using WGCNA to reduce dimensionality by identifying gene modules, followed by machine learning techniques to refine biomarker selection from these modules [19]. Commonly employed algorithms include LASSO regression, which applies L1-penalization to select features; Random Forests, which assess variable importance through ensemble decision trees; and Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE), which iteratively removes the least important features [19] [5]. Additionally, artificial neural networks are increasingly used to develop diagnostic models based on WGCNA-identified genes [5].

Table 2: Biomarkers Identified via WGCNA and Machine Learning for Sepsis-Induced ARDS

| Biomarker | Identification Method | Biological Function | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOCS3 | WGCNA + SVM-RFE + RF | Immune response regulation, JAK-STAT signaling | RT-qPCR in LPS-induced cell model [5] |

| LCN2 | WGCNA + SVM-RFE + RF | Iron trafficking, apoptosis regulation | RT-qPCR in LPS-induced cell model [5] |

| STAT3 | WGCNA + SVM-RFE + RF | Transcription factor, immune cell differentiation | RT-qPCR in LPS-induced cell model [5] |

| SIGLEC9 | WGCNA + LASSO | Immunoreceptor, neutrophil activation | Expression correlation with disease stage [20] |

| TSPO | WGCNA + LASSO | Mitochondrial function, inflammation regulation | Expression correlation with disease stage [20] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

A typical integrated WGCNA and machine learning workflow for sepsis-induced ARDS biomarker discovery follows a structured protocol [19] [5]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Gene expression datasets (e.g., from GEO database) are acquired and preprocessed. This includes probe-to-gene symbol conversion, batch effect removal using algorithms like ComBat from the sva package, and merging of multiple datasets when applicable [19].

Differential Expression and Co-expression Analysis: Differential expression analysis is performed using the limma R package with thresholds (adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |log2FC| ≥ 1) [19]. Concurrently, WGCNA is applied to identify gene modules correlated with clinical traits or immune cell infiltration patterns [19] [5].

Machine Learning Feature Selection: Multiple machine learning algorithms are applied to identify robust biomarkers. For example, LASSO regression uses 10-fold cross-validation to select features, Random Forest ranks genes by MeanDecreaseGini, and SVM-RFE recursively eliminates features to optimize classification [19] [5].

Experimental Validation: Identified biomarkers are validated using independent datasets and experimental approaches such as RT-qPCR in relevant cellular models (e.g., LPS-treated human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells) [5]. Immune infiltration analysis using CIBERSORT or ssGSEA further characterizes the relationship between biomarkers and immune cells [19].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Network Analysis Methods

WGCNA Versus Other Co-expression Network Approaches

While WGCNA represents a widely adopted framework for co-expression network analysis, several alternative approaches exist with distinct methodological characteristics. Alternative network analysis methods may employ different correlation measures, clustering algorithms, or network reconstruction strategies [21]. For instance, some approaches utilize igraph for network construction and community detection, identifying "communities" analogous to WGCNA modules [21]. Other methods might implement unweighted networks based on hard thresholding or apply alternative clustering techniques to identify groups of correlated genes [17].

Methodological Comparisons and Complementary Uses

The key advantage of WGCNA over many alternative methods lies in its weighted network approach, which preserves the continuous nature of co-expression information rather than dichotomizing relationships into present/absent connections [17]. This characteristic enhances biological relevance and robustness to noise in expression data. Additionally, WGCNA provides a comprehensive framework that integrates network construction, module detection, trait correlation, and hub gene identification into a cohesive analytical pipeline [22] [17].

Rather than positioning WGCNA as strictly superior to alternatives, researchers often employ complementary approaches to validate findings. Using independent methods to verify module reproducibility strengthens confidence in the identified co-expression structures [21]. Furthermore, different network analysis methods may reveal distinct aspects of the data, providing complementary biological insights when applied to the same dataset.

Table 3: Comparison of WGCNA with Alternative Network Analysis Approaches

| Feature | WGCNA | Unweighted Networks | igraph-Based Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Type | Weighted correlation network | Unweighted (binary edges) | Various (weighted/unweighted) |

| Thresholding | Soft thresholding (power β) | Hard thresholding | Configurable thresholding |

| Module Detection | Hierarchical clustering + dynamic tree cutting | Various clustering methods | Community detection algorithms |

| Key Outputs | Modules, eigengenes, hub genes | Gene clusters, network properties | Communities, network metrics |

| Primary Advantage | Preserves continuous correlation information, comprehensive framework | Computational simplicity, clear edge definition | Flexibility, extensive graph algorithms |

| Limitations | Parameter selection complexity, computational intensity | Loss of correlation magnitude information | Less specialized for gene expression data |

Successful implementation of WGCNA analysis requires both computational tools and experimental resources, particularly when transitioning from bioinformatics discovery to experimental validation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for WGCNA Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application in WGCNA Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Tools | WGCNA R package [22] [17] | Network construction, module detection, hub gene identification |

| Data Sources | Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [19] [5] | Source of expression datasets for analysis |

| Enrichment Analysis | clusterProfiler R package [19] | Functional annotation of modules (GO, KEGG) |

| Immune Cell Analysis | CIBERSORT [19], ssGSEA [19] | Characterization of immune infiltration patterns |

| Experimental Validation | LPS-induced cell models [5] | In vitro validation of hub gene expression |

| Expression Validation | RT-qPCR reagents [5] | Confirmation of hub gene expression patterns |

| Online Platforms | Metware Cloud [18], Omics Playground [16] | Code-free WGCNA implementation |

Limitations and Technical Considerations

Despite its powerful applications, WGCNA presents several important limitations and technical challenges that researchers must acknowledge [16]. The method involves multiple parameter decisions that can significantly impact results, including network type selection (signed vs. unsigned), correlation method choice (Pearson, Spearman, biweight midcorrelation), soft-thresholding power determination, and module detection parameters [16] [17]. Inappropriate parameter selection may lead to biologically misleading conclusions [16]. Additionally, WGCNA implementation traditionally required programming expertise in R, creating barriers for experimental biologists, though this has been mitigated by the development of user-friendly online platforms [16] [18].

The computational intensity of WGCNA, particularly for large datasets with thousands of genes, represents another practical consideration [17]. The construction of the topological overlap matrix and subsequent analyses can be resource-intensive, requiring adequate computational resources. Furthermore, while WGCNA effectively identifies correlation patterns, establishing causal relationships requires integration with additional experimental approaches [16]. Researchers should view WGCNA as a powerful hypothesis-generating tool rather than a definitive method for establishing mechanistic relationships.

Sepsis-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) represents a life-threatening complication of severe infection, characterized by a dysregulated host response that leads to diffuse pulmonary inflammation and respiratory failure [5] [23]. Despite advances in critical care management, sepsis-associated ARDS continues to exhibit high mortality rates, necessitating a deeper understanding of its underlying molecular mechanisms [5] [24]. The pathogenesis of sepsis-induced ARDS involves a complex interplay of several key biological processes, including dysregulated autophagy, excessive neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, and profound immune dysregulation [23] [24]. These interconnected pathways contribute to the damage of the alveolar-capillary barrier, pulmonary edema, and impaired gas exchange that define the clinical presentation of ARDS [5] [23]. Contemporary research has increasingly leveraged sophisticated bioinformatics approaches, particularly weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) combined with machine learning algorithms, to systematically identify critical biomarkers and therapeutic targets within these pathogenic processes [5] [24] [25]. This review comprehensively compares the roles of autophagy, NETs, and immune dysregulation in sepsis-induced ARDS, providing structured experimental data and visualization of the interconnected signaling pathways that drive this devastating condition.

Autophagy in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Functional Role and Molecular Mechanisms

Autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved intracellular degradation process, plays a dual role in sepsis-induced ARDS, functioning as both a protective mechanism and a potential contributor to pathology depending on its regulation and cellular context [23] [24]. Under physiological conditions, autophagy maintains cellular homeostasis by removing damaged organelles and misfolded proteins, while during infection, it participates in pathogen clearance and inflammation regulation [24]. However, in sepsis-induced ARDS, this process becomes significantly dysregulated. Research demonstrates that autophagic flux is frequently impaired in alveolar epithelial cells during sepsis, characterized by blocked autophagosome-lysosome fusion and subsequent accumulation of autophagic vesicles [23]. This impairment is mechanistically linked to NETs, which activate METTL3-mediated N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation of Sirt1 mRNA, resulting in abnormal autophagy and exacerbated lung injury [23].

The regulatory network controlling autophagy involves several critical genes and pathways. Bioinformatics analyses of sepsis-induced ARDS datasets have identified 18 autophagy-related differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with significant diagnostic potential [24]. Key signaling pathways associated with autophagic dysregulation include apoptosis, complement activation, IL-2/STAT5 signaling, and KRAS signaling, all of which are significantly downregulated in sepsis-induced ARDS compared to sepsis alone [24]. Additionally, autophagic impairment correlates strongly with immune cell alterations, particularly CD8+ T-cell exhaustion, natural killer cell reduction, and type 1 helper T-cell responses, highlighting the intricate connection between autophagy and immune dysfunction in sepsis-induced lung injury [24].

Experimental Evidence and Therapeutic Implications

Experimental models of sepsis-induced acute lung injury (SI-ALI) have provided compelling evidence for autophagy's role in disease pathogenesis. Electron microscopy examinations of lung tissues from cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) models reveal increased autophagic vesicles with simultaneous elevation of both LC3B (an autophagy hallmark) and SQSTM1/p62 (an autophagy substrate protein), indicating impaired autophagic flux rather than simply enhanced autophagy [23]. This impairment is further confirmed by reduced colocalization of lysosome (LAMP-1) and autophagosome (LC3B) markers, demonstrating defective autophagosome-lysosome fusion [23].

Therapeutic targeting of autophagy has shown promising results in experimental settings. Rapamycin, an autophagy activator, significantly improves survival rates at 24 hours post-CLP, alleviates lung injury scores, reduces pulmonary wet/dry ratio, and decreases inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) in both plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [23]. Similarly, NETs inhibition through PAD4 inhibitor (GSK484), neutrophil depletion via anti-Ly6G antibody, or NETs degradation with DNase I all reduce SQSTM1/p62 expression, suggesting restored autophagic flux [23]. These findings position autophagic regulation as a promising therapeutic strategy for sepsis-induced ARDS.

Table 1: Key Autophagy-Related Genes in Sepsis-Induced ARDS Identified via Bioinformatics

| Gene Symbol | Expression Pattern | Functional Role | Diagnostic AUC | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC3B | Upregulated | Autophagosome formation | >0.7 | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot |

| SQSTM1/p62 | Upregulated | Autophagy substrate accumulation | >0.7 | Western blot, Immunofluorescence |

| SIRT1 | Downregulated | Autophagy regulation via deacetylation | >0.65 | qPCR, Western blot |

| METTL3 | Upregulated | m6A methylation of Sirt1 mRNA | >0.65 | Western blot, Methylation assays |

NETs Formation in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Pathogenic Mechanisms and Biomarker Identification

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) represent a crucial defense mechanism against pathogens, but their excessive formation or impaired clearance plays a central role in the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced ARDS [23] [25]. NETs are extracellular fibrous structures composed of nuclear DNA, histones, antimicrobial peptides, and various bactericidal factors that immobilize and eliminate pathogens [25]. In sepsis-induced ARDS, NETs formation is significantly enhanced, leading to exacerbated inflammatory responses, coagulation abnormalities, and direct tissue damage [23] [25]. Clinical studies demonstrate markedly elevated levels of MPO-DNA complexes and cell-free DNA (cf-DNA) in ARDS patients compared to healthy controls, with a strong negative correlation between cf-DNA levels and PaO2/FiO2 ratios [23]. Furthermore, neutrophils from ARDS patients exhibit an increased capacity for NETs formation even after stimulation with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) [23].

Bioinformatics approaches combining WGCNA with machine learning have identified several key NETs-related genes as diagnostic biomarkers for sepsis-induced ARDS. Through analysis of the GSE32707 dataset and integration with NETs gene sets, researchers have identified LTF and PRTN3 as hub genes with excellent diagnostic potential [25]. These findings are clinically validated through RT-qPCR analysis, which shows significant upregulation of PRTN3 and LTF expression in sepsis-associated ARDS patients compared to healthy controls [25]. Additional investigations have identified five key genes—LCN2, AIF1L, STAT3, SOCS3, and SDHD—as diagnostic biomarkers for both sepsis-induced ARDS and cardiomyopathy, with SOCS3 serving as a particularly promising hub gene and therapeutic target [5].

NETs-Driven Lung Injury and Therapeutic Interventions

NETs contribute to sepsis-induced ARDS through multiple interconnected mechanisms. They directly impair autophagic flux in alveolar epithelial cells via METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of Sirt1 mRNA, creating a vicious cycle of cellular dysfunction and inflammation [23]. NETs also induce various forms of cell death, including ferroptosis (evidenced by decreased GPX4 expression), apoptosis (increased cleaved caspase-3), and pyroptosis (elevated caspase-11) in a time-dependent manner [23]. Additionally, NETs trigger profound inflammatory responses by promoting the release of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in both plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [23].

Therapeutic targeting of NETs has shown significant promise in experimental models. Inhibition of NETosis through PAD4 inhibitor (GSK484), neutrophil depletion with anti-Ly6G antibody, or NETs degradation using DNase I all substantially alleviate lung injury in CLP models, as evidenced by reduced lung injury scores, decreased pulmonary wet/dry ratio, and lower inflammatory cytokine levels [23]. Molecular docking studies have identified potential therapeutic compounds targeting NETs-related genes, including nimesulide and minocycline for LTF and PRTN3, as well as dexamethasone, resveratrol, and curcumin as potential SOCS3-targeting drugs [5] [25]. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of NETs-focused interventions for sepsis-induced ARDS.

Table 2: NETs-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches in Experimental Models

| Therapeutic Approach | Specific Agent | Mechanism of Action | Observed Effects | Experimental Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NETosis Inhibition | GSK484 (PAD4 inhibitor) | Prevents histone citrullination and NETs release | Reduced lung injury scores, decreased cf-DNA, lower inflammatory cytokines | CLP mouse model |

| Neutrophil Depletion | Anti-Ly6G antibody | Depletes circulating neutrophils | Alleviated haemorrhage and alveolar oedema, thicker alveolar septa | CLP mouse model |

| NETs Degradation | DNase I | Degrades DNA backbone of existing NETs | Improved survival, reduced NETs accumulation in lung tissue | CLP mouse model |

| Small Molecule Targeting | Nimesulide, Minocycline | Potential binding to LTF and PRTN3 | Predicted by molecular docking | Computational analysis |

Immune Dysregulation in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

Cellular and Molecular Immune Alterations

Sepsis-induced ARDS is characterized by profound immune dysregulation involving both innate and adaptive immune responses. Bioinformatic analyses of sepsis-induced ARDS datasets reveal significant alterations in at least seven immune cell subsets, including CD8+ T-cell exhaustion, natural killer cell reduction, and altered type 1 helper T-cell responses [24]. These changes correlate strongly with disease severity and progression. Additionally, monocyte distribution width (MDW) has emerged as a valuable parameter for sepsis diagnosis, with monocytes enlarging upon activation during bacteremia or fungemia [26]. Studies demonstrate that MDW > 23.4 has 69.8% sensitivity and 67.5% specificity for predicting sepsis, while in ICU settings, MDW > 23 shows 75.3% sensitivity and 88.7% specificity for sepsis diagnosis [26].

The immune dysregulation in sepsis-induced ARDS extends beyond cellular populations to include cytokine networks and signaling pathways. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are recognized as key factors in triggering ARDS in sepsis patients [5]. interleukin-10 (IL-10) has shown diagnostic value when combined with clinical scores, with IL-10 ≥5.03 pg/mL and NEWS≥5 providing the best screening performance for early sepsis recognition (AUC 0.789) [26]. Other biomarkers including heparin-binding protein (HBP), presepsin, procalcitonin (PCT), and C-reactive protein (CRP) also contribute to the immune and inflammatory signature of sepsis-induced ARDS, offering complementary diagnostic and prognostic information [26] [27].

Bioinformatics Insights into Immune Networks

WGCNA and machine learning approaches have provided unprecedented insights into the immune networks underlying sepsis-induced ARDS. Studies applying these methodologies have identified key immune-related modules and hub genes strongly associated with disease pathogenesis [5] [24]. For instance, SOCS3 has been identified as a critical immune-related hub gene with strong diagnostic potential, and its expression correlates significantly with immune cell infiltration patterns [5]. Gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) have highlighted SOCS3's role in biological processes and immune responses, while correlation analyses have demonstrated strong relationships between feature genes, immune infiltration, and clinical characteristics [5].

Immune infiltration analyses using techniques such as CIBERSORT and single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) have provided quantitative assessments of immune cell alterations in sepsis-induced ARDS [24]. These analyses reveal not only changes in immune cell proportions but also functional alterations that contribute to the immunosuppressive phase often observed in later stages of sepsis. The characterization of immune landscapes has further enabled researchers to identify potential therapeutic targets within immune signaling pathways, opening new avenues for immunomodulatory interventions in sepsis-induced ARDS [5] [24].

Interplay Between Pathogenic Processes

The pathogenesis of sepsis-induced ARDS involves complex crosstalk between autophagy, NETs formation, and immune dysregulation, rather than these processes functioning in isolation. NETs have been shown to directly impair autophagic flux in alveolar epithelial cells through METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of Sirt1 mRNA, creating a vicious cycle where impaired autophagy further exacerbates inflammatory responses and cellular damage [23]. This interplay is further evidenced by the observation that NETs inhibition, depletion, or degradation can reduce SQSTM1/p62 expression, indicating restoration of autophagic flux [23]. Similarly, autophagy influences immune responses by modulating cytokine production and immune cell function, while immune cells such as neutrophils are the primary source of NETs [23] [24].

Bioinformatics analyses have visually captured these interconnections through protein-protein interaction networks and correlation heatmaps [5] [24] [25]. Studies combining WGCNA with machine learning have identified shared diagnostic markers for sepsis-induced ARDS and cardiomyopathy, suggesting common pathogenic pathways across different organ systems in sepsis [5]. The integration of multiple datasets and analytical approaches has enabled researchers to construct comprehensive networks depicting the molecular relationships between autophagy-related genes, NETs components, and immune regulators, providing a systems-level understanding of sepsis-induced ARDS pathogenesis [5] [24] [25].

Figure 1: Interplay Between Key Pathogenic Processes in Sepsis-Induced ARDS. This diagram illustrates the complex crosstalk between NETs formation, autophagy dysregulation, and immune dysregulation in driving lung damage during sepsis-induced ARDS.

Research Reagent Solutions

Contemporary research on autophagy, NETs, and immune dysregulation in sepsis-induced ARDS relies on a sophisticated toolkit of reagents, databases, and analytical resources. The following table summarizes essential materials and their applications in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Sepsis-Induced ARDS Investigation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Primary Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Databases | GEO Database (GSE32707, GSE79962, GSE10474) | Data source for transcriptomic analysis | Publicly available gene expression datasets [5] [24] [25] |

| Gene Reference Databases | HAMdb, HADb, MSigDB, TISIDB | Functional annotation and pathway analysis | Curated gene sets, autophagy databases, immune interaction data [24] |

| Analytical R Packages | WGCNA, limma, clusterProfiler, pROC, randomForest, e1071, glmnet | Bioinformatics analysis and machine learning | Network construction, differential expression, enrichment analysis, feature selection [5] [24] [25] |

| Experimental Models | Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), LPS-induced lung injury | In vivo disease modeling | Reproduces key features of human sepsis-induced ARDS [23] [24] |

| Cell Cultures | Human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMECs), Beas-2B cells | In vitro mechanistic studies | Investigate cellular responses to sepsis-related insults [5] [24] |

| Therapeutic Compounds | GSK484 (PAD4 inhibitor), DNase I, rapamycin, anti-Ly6G antibody | Pathway targeting and validation | Specific inhibitors/activators of NETosis, autophagy, and immune pathways [23] |

The integration of WGCNA and machine learning approaches has significantly advanced our understanding of the key pathogenic processes in sepsis-induced ARDS, particularly autophagy dysregulation, NETs formation, and immune dysregulation. These methodologies have enabled the identification of robust diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, including autophagy-related genes, NETs components such as LTF and PRTN3, and immune regulators like SOCS3. The experimental data summarized in this review clearly demonstrate the complex interplay between these pathways and their collective contribution to lung damage in sepsis. Quantitative comparisons of diagnostic performance, therapeutic efficacy, and mechanistic insights provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for prioritizing targets and designing intervention strategies. As these analytical approaches continue to evolve, they promise to further unravel the molecular complexity of sepsis-induced ARDS and accelerate the development of targeted therapies for this devastating condition.

Sepsis-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) represents a devastating clinical challenge in critical care medicine, characterized by dysregulated immune responses, diffuse alveolar damage, and profound inflammatory signaling. The search for robust diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets has increasingly turned to advanced computational approaches, particularly Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) and machine learning algorithms. These methods enable researchers to move beyond single-molecule biomarkers to identify complex, interconnected gene networks and modules that drive disease pathogenesis [5] [6]. Within this context, two critical biological processes—sialylation pathways and Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) formation—have emerged as promising candidates for further investigation due to their fundamental roles in immune regulation and inflammatory tissue injury.

Sialylation, the enzymatic addition of sialic acid to glycoproteins and glycolipids, serves as a crucial modulator of cell-surface interactions, immune recognition, and inflammatory signaling [28] [29]. Concurrently, NETosis represents a distinct form of cell death wherein neutrophils release decondensed chromatin structures decorated with antimicrobial proteins to ensnare pathogens [30] [31]. While both processes serve essential host defense functions, their dysregulation contributes significantly to the hyperinflammatory state and organ damage characteristic of sepsis-induced ARDS. This review integrates current understanding of these pathways, their molecular interplay, and their potential as therapeutic targets within the framework of modern bioinformatics-driven biomarker discovery.

Molecular Mechanisms of Sialylation in Inflammation and Immunity

Sialic Acid Biosynthesis and Structural Diversity

Sialic acids are nine-carbon backbone monosaccharides that typically occupy the terminal positions of glycoproteins and glycolipids, where they mediate diverse biological recognition processes. The most prevalent form in humans is N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), though over 50 structurally distinct sialic acid derivatives have been identified in nature [29]. The biosynthesis of sialic acids proceeds through a conserved four-step pathway beginning in the cytosol, where the bifunctional enzyme GNE catalyzes the initial two steps: the formation of N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) from UDP-GlcNAc, followed by phosphorylation to yield ManNAc-6-P [28]. Subsequent steps produce N-acetylneuraminic acid-9-phosphate (Neu5Ac-9-P), which is dephosphorylated to yield free Neu5Ac. The activated sugar nucleotide donor CMP-Neu5Ac is then synthesized in the nucleus by CMP-sialic acid synthetase (CMAS) before transport to the Golgi apparatus [28].

Within the Golgi, sialyltransferases catalyze the transfer of sialic acid from CMP-Neu5Ac to growing glycan chains on glycoproteins and glycolipids. These enzymes are categorized based on the linkage they form: ST3Gals (α2,3-linkages), ST6Gals (α2,6-linkages), and ST8Sias (α2,8-linkages) [29]. The sialylation process is dynamically regulated by the opposing actions of sialyltransferases and sialidases (neuraminidases), which remove sialic acid residues. This balance determines the sialylation status of cell surfaces and profoundly influences cellular interactions in health and disease [29].

Sialylation as a Regulator of Immune Cell Function

Sialylation modulates immune function through multiple mechanisms, primarily via interactions with sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectins (Siglecs) and selectins. Siglecs are transmembrane receptors predominantly expressed on immune cells that recognize sialylated glycans and transduce signals that typically inhibit immune activation [29]. For instance, Siglec-E and Siglec-G engagement has demonstrated significant anti-inflammatory potential in sepsis models, suggesting therapeutic targeting opportunities [29]. Selectins, including E-, P-, and L-selectin, recognize sialylated Lewis X antigens and mediate the initial tethering and rolling of leukocytes along vascular endothelium during inflammation [29].

Table 1: Key Sialyltransferases and Their Roles in Immune Regulation

| Sialyltransferase | Linkage Formed | Biological Functions | Role in Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ST6GAL1 | α2,6-linkage to galactose | Regulates antibody function, complement activation, leukocyte signaling | Upregulated in sepsis; negative systemic regulator of granulopoiesis [32] |

| ST3GAL | α2,3-linkage to galactose | Facilitates selectin ligand formation | Promotes leukocyte extravasation to sites of inflammation [29] |

| ST8SIA | α2,8-linkage to sialic acid | Forms polysialic acid chains | Modulates cell adhesion and migration in neural and immune contexts [29] |

Sialylation also critically regulates complement activation, particularly the alternative pathway. Factor H, a key complement regulatory protein, recognizes sialic acids on host cells as "self," leading to downregulation of complement activation and protection against inappropriate bystander damage [29]. Additionally, sialylation of the Fc portion of immunoglobulins influences their inflammatory activity and serum half-life [29].

Extrinsic Sialylation as a Novel Regulatory Mechanism

Beyond the canonical intracellular sialylation pathway, recent evidence has revealed the importance of extrinsic sialylation—the remodeling of cell-surface glycans by extracellular sialyltransferases. Circulating ST6Gal-1, primarily secreted by the liver, can modify cell surfaces remotely, with activated platelets serving as critical suppliers of the sugar donor substrate CMP-sialic acid [33]. This extrinsic sialylation is not constitutive but is triggered by inflammatory stimuli such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) or ionizing radiation [32]. Platelet activation during inflammation releases CMP-sialic acid contained within microparticles, providing localized substrate concentrations sufficient to drive extracellular sialylation reactions [33]. This mechanism represents a rapidly inducible system for modifying cell-surface recognition properties in response to systemic triggers.

NET Formation: Pathways, Regulation, and Pathological Consequences

Molecular Mechanisms of NETosis

Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) are web-like structures composed of decondensed chromatin decorated with antimicrobial proteins including neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase (MPO), cathepsin G, and histones [31]. NET formation occurs through several distinct molecular pathways, broadly categorized as suicidal NETosis, vital NETosis, and mitochondrial DNA-driven NETosis [34] [35].

NOX-Dependent NETosis (Suicidal NETosis): This classical pathway is triggered by stimuli such as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), microbes, or interleukin-8 (IL-8) [30] [31]. Engagement of these stimuli activates protein kinase C (PKC) and the Raf-MEK-ERK signaling cascade, leading to increased cytoplasmic calcium levels and assembly of the NADPH oxidase (NOX) complex [34]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by NOX activate neutrophil elastase, which translocates to the nucleus and degrades histones, facilitating chromatin decondensation [30] [34]. Concurrently, peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) citrullinates histones, further promoting chromatin relaxation [34]. Nuclear envelope rupture is mediated by cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6), which phosphorylate retinoblastoma protein (Rb) and lamin B [34]. The process culminates in plasma membrane rupture and NET release, a process dependent on gasdermin D (GSDMD) [34].

NOX-Independent NETosis (Vital NETosis): This pathway operates independently of NADPH oxidase and ROS generation, instead relying primarily on PAD4 activation [34]. Stimuli including granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), activated platelets, immune complexes, or the calcium ionophore A23187 can trigger this rapid form of NETosis [34] [35]. In vital NETosis, chromatin decondensation occurs without immediate neutrophil lysis; instead, nuclear material is encapsulated within vesicles that bud from the nucleus and are expelled extracellularly while preserving neutrophil viability and function [31].

Mitochondrial DNA-Driven NETosis: A third mechanism involves NETs composed primarily of mitochondrial DNA rather than nuclear DNA [34]. Stimuli such as complement component C5a and LPS trigger the release of mitochondrial DNA in a process dependent on mitochondrial ROS generation but independent of neutrophil lysis [34]. This pathway requires glycolytic ATP production and cytoskeletal reorganization via microtubule and F-actin remodeling [34].

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathways of NET Formation. NETosis occurs through distinct signaling mechanisms, including NOX-dependent suicidal NETosis and NOX-independent vital NETosis.

NETs in Sepsis and ARDS: Protective and Pathological Roles

NETs play a complex dual role in sepsis and ARDS, serving both protective antimicrobial functions and contributing to tissue injury and organ dysfunction. The protective role of NETs involves pathogen trapping and killing, with demonstrated efficacy against bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus), fungi (Candida albicans), and viruses [34]. NETs achieve this through high local concentrations of antimicrobial components and by creating physical barriers that prevent pathogen dissemination [31].

However, excessive or dysregulated NET formation contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced ARDS through multiple mechanisms. NETs can cause direct cytotoxic effects on endothelial and epithelial cells, promote immunothrombosis via interactions with platelets and coagulation factors, and act as autoantigens that drive autoimmune responses [34] [31]. In sepsis-induced ARDS, NETs have been implicated in increased vascular permeability, pulmonary edema, and amplification of inflammatory responses through the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [6]. Bioinformatics analyses of sepsis-induced ARDS datasets have revealed significant enrichment of NET formation pathways among differentially expressed genes, highlighting their importance in disease pathogenesis [6].

Table 2: NET Components and Their Pathological Effects in Sepsis-Induced ARDS

| NET Component | Biological Function | Pathological Role in Sepsis-Induced ARDS |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-free DNA | Structural backbone | Increases blood viscosity, endothelial damage, DAMP signaling [31] |

| Histones | Antimicrobial activity | Cytotoxic to endothelial cells, promote platelet aggregation [31] |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Microbial killing | Oxidative tissue damage, endothelial barrier disruption [30] |

| Neutrophil Elastase (NE) | Microbial killing, histone degradation | Proteolytic damage to endothelial and epithelial cells [30] [34] |

| Peptidylarginine Deiminase 4 (PAD4) | Histone citrullination | Autoantigen generation, amplifies NET formation [34] |

Integrating Sialylation and NETosis in Sepsis Pathogenesis

Molecular Interplay Between Sialylation and NET Formation

Emerging evidence suggests significant crosstalk between sialylation pathways and NET formation, with potential implications for sepsis-induced ARDS pathogenesis. Activated platelets, which serve as crucial suppliers of sugar donor substrates for extrinsic sialylation [33], are also potent inducers of vital NETosis [34]. This suggests a coordinated response wherein platelet activation simultaneously promotes both sialylation remodeling and NET release. Additionally, sialylated structures on neutrophil surfaces may modulate their susceptibility to NETosis induction or their capacity to form NETs, though the precise mechanisms require further elucidation.

The inflammatory milieu of sepsis, characterized by elevated cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-8) and bacterial products (LPS), drives both increased sialyltransferase expression [32] and NET formation [34]. This parallel induction suggests potential co-regulation of these pathways during systemic inflammation. Furthermore, sialic acid recognition by Siglecs on neutrophils may provide regulatory input that modulates NETosis thresholds, potentially serving as a checkpoint mechanism to prevent excessive NET formation [29].

Implications for Biomarker Discovery via WGCNA and Machine Learning

The integration of sialylation and NETosis pathways into WGCNA and machine learning frameworks offers promising avenues for biomarker discovery in sepsis-induced ARDS. WGCNA analysis of sepsis-induced ARDS datasets has identified gene modules significantly correlated with immune cell infiltration, including macrophages and neutrophils [6]. These modules are enriched for biological processes including leukocyte migration, reactive oxygen species metabolism, and myeloid leukocyte activation—processes intimately connected to both sialylation and NETosis [6].

Machine learning approaches including support vector machine-recursive feature elimination (SVM-RFE) and random forest algorithms have identified diagnostic gene signatures for sepsis-induced ARDS [5] [6]. These computational methods effectively prioritize genes with strong discriminatory power while naturally capturing nonlinear relationships between molecular features. The intersection of sialylation-related genes (e.g., ST6GAL1, NEU1) and NETosis-related genes (e.g., PAD4, ELANE, MPO) within these predictive models would strengthen their biological plausibility and potential therapeutic relevance.

Table 3: Machine Learning Applications in Sepsis-Induced ARDS Biomarker Discovery

| Study | Computational Methods | Key Identified Biomarkers | Association with Sialylation/NETosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2025 [5] | WGCNA, SVM-RFE, Random Forest, Artificial Neural Network | LCN2, AIF1L, STAT3, SOCS3, SDHD | SOCS3 implicated in immune cell signaling and inflammation regulation |

| Scientific Reports, 2023 [6] | WGCNA, SVM-RFE, Random Forest, Immune Infiltration Analysis | SGK1, DYSF, MSRB1 | SGK1 associated with oxidative stress responses and immune regulation |

| Common Pathways Identified | Enrichment Analysis, Protein-Protein Interaction Networks | Neutrophil Extracellular Trap Formation, ROS Metabolism, Leukocyte Migration | Direct involvement of NETosis pathways and related inflammatory processes |

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagents

Key Methodologies for Investigating Sialylation and NETosis

The study of sialylation and NETosis employs diverse experimental approaches ranging from molecular biology techniques to advanced imaging and computational analyses. For NETosis research, common methodologies include immunofluorescence microscopy for NET visualization using DNA dyes (Hoechst, SYTOX Green) combined with antibodies against NET components (neutrophil elastase, citrullinated histones), quantitative assays for NET release (DNA quantification, MPO-DNA ELISA), and specific inhibition of NETosis pathways (NADPH oxidase inhibitors, PAD4 inhibitors) [30] [34].

Sialylation research employs techniques including lectin staining (SNA, MAL-II) for detecting specific sialic acid linkages, mass spectrometry for comprehensive sialylation profiling, enzymatic desialylation approaches (neuraminidase treatment), and genetic manipulation of sialyltransferases or sialidases [28] [29]. The integration of these molecular approaches with computational analyses strengthens the identification of biologically meaningful biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Biomarker Discovery. Combining multi-omics profiling with computational analyses and experimental validation enables robust identification of diagnostic and therapeutic targets in sepsis-induced ARDS.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Sialylation and NETosis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NET Inducers | PMA, Calcium Ionophore A23187, LPS, Candida albicans, Bacterial pathogens | Activate specific NETosis pathways [30] | Different inducers engage distinct signaling mechanisms; PMA strong NOX-dependent activator [30] |

| NET Inhibitors | DNase I, NADPH oxidase inhibitors (DPI), PAD4 inhibitors (Cl-amidine), Neutrophil elastase inhibitors | Dissect NETosis mechanisms, therapeutic assessment [34] | DNase degrades existing NETs; pharmacological inhibitors prevent NET formation [31] |

| NET Detection Reagents | Anti-citrullinated histone H3 antibodies, SYTOX Green, Hoechst dyes, Anti-MPO/NE antibodies | Visualize and quantify NET formation [30] [34] | Combined DNA staining and component immunodetection provides specificity [30] |

| Sialylation Modulators | Neuraminidases (sialidases), Sialyltransferase inhibitors, Metabolic substrate analogs (P-3Fax-Neu5Ac) | Manipulate sialylation status, assess functional consequences [29] | Sialidases remove surface sialic acids; inhibitors block addition [29] |

| Sialylation Detection Reagents | SNA lectin (α2,6-linkages), MAL-II lectin (α2,3-linkages), Anti-polysialic acid antibodies, Fluorophore-labeled CMP-sialic acid | Detect specific sialic acid linkages and distribution [28] [33] | Lectins provide linkage-specific detection; metabolic labeling enables dynamic tracking [33] |