Lipid Metabolism and Small Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis in Cancer: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targeting

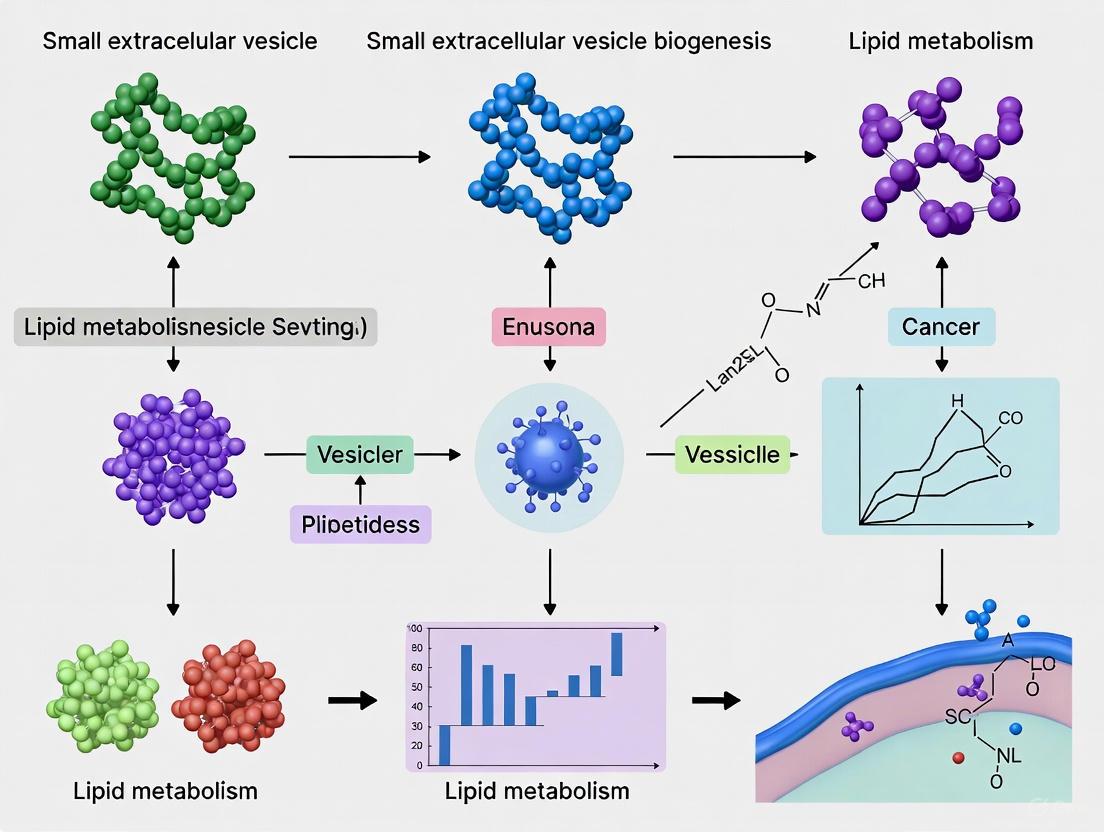

This article synthesizes current research on the critical interface between lipid metabolism and small extracellular vesicle (sEV) biogenesis in cancer.

Lipid Metabolism and Small Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis in Cancer: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the critical interface between lipid metabolism and small extracellular vesicle (sEV) biogenesis in cancer. It explores the fundamental mechanisms by which lipid signaling and metabolic reprogramming drive sEV formation, release, and function within the tumor microenvironment. For a research-focused audience, the content details advanced methodologies for sEV isolation and lipidomic analysis, evaluates sEVs as non-invasive biomarkers and drug delivery vehicles, and discusses the therapeutic potential of targeting lipid-sEV pathways. The review also addresses key challenges in the field and provides a comparative analysis of validation strategies, aiming to bridge basic science with clinical translation in oncology.

The Lipid and sEV Nexus: Core Mechanisms in Cancer Progression

Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are membrane-bound nanoparticles, typically less than 200 nm in diameter, that are secreted by virtually all cell types into the extracellular space [1]. These vesicles play pivotal roles in intercellular communication by transferring functional proteins, nucleic acids (including miRNAs and mRNAs), lipids, and other bioactive substances between cells, thereby influencing the physiological state and functions of recipient cells [2] [3]. This transfer of information is particularly critical within the tumor microenvironment (TME), where tumor-derived sEVs (TDsEVs) contribute significantly to cancer progression, immune evasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance [3] [4]. The biogenesis of sEVs—the process by which they are formed and released—is a complex and regulated cellular process. It occurs primarily through two overarching mechanisms: the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT)-dependent pathway and several ESCRT-independent pathways [2] [5]. Understanding these mechanisms is fundamental to comprehending sEV function in health and disease and for harnessing their potential in diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

The ESCRT-Dependent Biogenesis Pathway

The canonical pathway for sEV biogenesis is dependent on the ESCRT machinery, a highly conserved multi-protein complex essential for membrane remodeling and scission events within the cell [5]. This pathway gives rise to sEVs of endosomal origin, often specifically referred to as exosomes.

The Sequential ESCRT Machinery

The ESCRT apparatus consists of five core complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, -III, and VPS4) that function sequentially in the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) inside multivesicular bodies (MVBs) [2] [5]. The process begins with the recognition and clustering of ubiquitinated cargo proteins by the ESCRT-0 complex (involving proteins like HRS and STAM1) on the endosomal membrane [2] [4]. ESCRT-0 then recruits ESCRT-I and ESCRT-II, which work together to initiate the inward budding of the endosomal membrane. ESCRT-II subsequently engages the ESCRT-III complex, which polymerizes into filaments that constrict the neck of the budding vesicle. Finally, the ATPase VPS4 catalyzes the disassembly of the ESCRT-III complex, completing the membrane scission and releasing the ILV into the lumen of the MVB [2] [5]. Once formed, these MVBs are transported along the cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane in a process regulated by Rab GTPases (e.g., Rab27a, Rab27b, Rab11) [3] [4]. The MVB then fuses with the plasma membrane, releasing the ILVs into the extracellular space as sEVs [1] [5].

Key Regulatory Proteins and Alternative ESCRT Recruitment

The accessory protein ALIX plays a critical role in an alternative ESCRT-dependent pathway. ALIX can be recruited to the endosomal membrane by the syndecan-syntenin complex, where it interacts directly with both ESCRT-I (via TSG101) and ESCRT-III (via CHMP4), serving as an alternative platform to orchestrate ILV formation and cargo sorting independently of ESCRT-0 [2] [5]. This syndecan-syntenin-ALIX axis is exploited in tumor environments to enhance the production of sEVs with promigratory activity [5].

Table 1: Key Molecular Components of the ESCRT-Dependent Pathway

| Component | Key Function | Specific Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| ESCRT-0 | Initiates pathway; recognizes & clusters ubiquitinated cargo | HRS, STAM1 |

| ESCRT-I & II | Mediates membrane budding and deformation | TSG101 |

| ESCRT-III | Executes membrane scission and vesicle release | CHMP4, CHMP3 |

| VPS4 | Recycles ESCRT machinery; finalizes scission | VPS4A, VPS4B |

| Accessory Proteins | Provides alternative ESCRT recruitment pathways | ALIX, Syntenin |

| Regulatory GTPases | Controls MVB trafficking and fusion with plasma membrane | Rab27a, Rab27b, Rab11 |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential action of the ESCRT complexes in the biogenesis of sEVs:

ESCRT-Independent Biogenesis Pathways

While the ESCRT machinery is central, cells possess several alternative mechanisms for sEV biogenesis that operate independently of ESCRT components. These pathways often rely on specific lipids and membrane microdomains.

The Ceramide-Based Pathway

A major ESCRT-independent mechanism involves the lipid ceramide [4] [5]. The enzyme neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) converts sphingomyelin in the endosomal membrane into ceramide. Due to its cone-shaped molecular structure, ceramide can spontaneously induce negative membrane curvature, driving the inward budding of the endosomal membrane to form ILVs [2] [5]. This pathway is crucial for the sorting of certain cargoes, such as the proteolipid protein (PLP), and can be enhanced by proteins like FAN, which is recruited to MVBs via the autophagy-related protein LC3 [4]. Inhibition of nSMase2 has been shown to impair sEV biogenesis and cargo sorting, underscoring its functional importance [2] [4].

Tetraspanin- and Raft-Based Pathways

Tetraspanins, a family of membrane proteins that are highly enriched in sEVs (e.g., CD63, CD9, CD81), also contribute to ESCRT-independent biogenesis [2] [4]. These proteins can form specialized transmembrane platforms known as tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs). Tetraspanins like CD63 can promote ILV formation and cargo sorting (e.g., of PMEL) through interactions with partners like Apolipoprotein E, leveraging both ESCRT-dependent and ceramide-dependent mechanisms [4]. Other membrane scaffolding proteins, such as flotillins and caveolin-1, are involved in organizing lipid rafts and can facilitate the sorting of specific cargo into ILVs in an ESCRT-independent manner, although caveolin-1's role may be constrained by the nSMase2-ceramide pathway [4].

Other Mechanisms and Cellular Context

It is important to note that these pathways are not mutually exclusive. They can operate simultaneously within a single cell, potentially generating distinct subpopulations of sEVs with different cargo compositions and functions [2]. For instance, in polarized epithelial cells, sEVs released from the basolateral side originate from a ceramide-dependent mechanism, while those from the apical side are formed via an ALIX-dependent pathway [2]. Furthermore, certain cellular conditions, such as glutamine deprivation or mTOR inhibition, can trigger the formation of a unique class of sEVs from Rab11-positive recycling endosomes, a process involving ESCRT-III accessory proteins CHMP1, CHMP5, and IST1 [2].

Table 2: Key Components of ESCRT-Independent sEV Biogenesis Pathways

| Pathway | Key Molecules | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Ceramide-Dependent | nSMase2, Ceramide, FAN | Cone-shaped ceramide induces negative membrane curvature for inward budding. |

| Tetraspanin-Mediated | CD63, CD9, CD81, Flotillins | Formation of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains (TEMs) that facilitate cargo clustering and membrane budding. |

| Other Lipid Raft-Associated | Caveolin-1, Cholesterol | Organizes specific membrane microdomains to promote vesicle formation and cargo sorting. |

The relationship between different ESCRT-independent pathways is summarized below:

Lipids in sEV Biogenesis and Function

Lipids are not merely structural components of sEVs; they are active players in their biogenesis, composition, and function. The lipid composition of sEVs is distinct from that of the parent cell membrane, being enriched in sphingomyelin, cholesterol, glycosphingolipids, and phosphatidylserine [6] [7]. This specific lipid profile contributes to the rigidity and stability of sEVs, protecting their cargo during transit in the extracellular environment [7].

Lipid Involvement in Biogenesis

As detailed in the ceramide pathway, lipids are direct mediators of ESCRT-independent biogenesis. Beyond ceramide, other lipids like phosphatidic acid can also induce membrane curvature [2]. Moreover, the ESCRT machinery itself may rely on a specific lipid environment, such as cholesterol-rich liquid-ordered membrane domains, to function efficiently [2]. The lipid bilayer of sEVs also features an asymmetric distribution of lipids; for instance, phosphatidylserine is primarily located on the inner leaflet of the cell membrane but is found abundantly in the membranes of sEVs, where it may play a role in signaling and uptake by recipient cells [6].

Lipid Metabolism in Cancer and sEVs

Cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming, including dysregulation of lipid metabolism, which is reflected in the lipid cargo of TDsEVs [8] [7]. Tumor cells exhibit increased de novo lipogenesis and uptake of exogenous lipids to support rapid growth and membrane biogenesis. Consequently, TDsEVs are often enriched with specific lipids such as phosphatidylserine, prostaglandins, and lysophosphatidic acid [8] [6]. These lipids can function as signaling molecules in the tumor microenvironment, promoting processes such as angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and the formation of pre-metastatic niches [8] [7]. For example, lipids like lysophosphatidic acid and prostaglandins can enhance the release of angiogenic factors like VEGF, facilitating tumor vascularization [8].

Experimental Protocols for Studying sEV Biogenesis

Elucidating the mechanisms of sEV biogenesis requires a combination of genetic, biochemical, and pharmacological approaches. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the literature.

Genetic Knockdown of Biogenesis Regulators

A common strategy to define the role of a specific protein in sEV biogenesis is to deplete it using RNA interference (RNAi) and analyze the resulting effects on sEV production and cargo.

- Protocol Example: Knockdown of ESCRT Components and ALIX [9]

- Cell Culture: Maintain human cells (e.g., HeLa cells or Mesenchymal Stromal Cells) in appropriate media under standard conditions.

- Transfection: Transfect cells with small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting genes of interest (e.g., TSG101, HRS, ALIX) using a suitable transfection reagent. Include a non-targeting siRNA as a negative control.

- Incubation: Allow 48-72 hours for effective protein knockdown.

- sEV Isolation: Replace media with exosome-depleted serum. After 24-48 hours, collect the conditioned media.

- Differential Ultracentrifugation: Isolate sEVs via a series of centrifugation steps.

- Centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 min to remove cells.

- Centrifuge supernatant at 2,000 × g for 20 min to remove dead cells.

- Centrifuge supernatant at 10,000 × g for 30 min to remove cell debris and larger vesicles.

- Ultracentrifuge the resulting supernatant at 100,000 × g for 70 min to pellet sEVs.

- Wash the pellet in PBS and ultracentrifuge again at 100,000 × g for 70 min.

- Analysis:

- Quantification: Measure sEV protein yield using a Bradford or BCA assay.

- Characterization: Analyze sEV size and concentration using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA).

- Cargo Profiling: Validate knockdown efficiency and analyze changes in sEV markers (e.g., CD63, CD81) via Western blotting.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Key Pathways

Small molecule inhibitors can be used to rapidly and reversibly dissect the contribution of specific enzymatic activities to sEV biogenesis.

- Protocol Example: Inhibition of nSMase2 with GW4869 [4]

- Cell Treatment: Culture cancer cells to ~70% confluence.

- Inhibitor Application: Treat cells with a specific inhibitor. For the ceramide pathway, use GW4869 (e.g., at 10-20 µM) or an alternative nSMase2 inhibitor. Use DMSO as a vehicle control.

- sEV Collection and Isolation: Incubate for 24-48 hours, then collect conditioned media and isolate sEVs using differential ultracentrifugation as described in section 5.1.

- Functional Analysis:

- Quantify sEV yield (protein or particle number) to assess the effect of inhibition on sEV secretion.

- Extract lipids from isolated sEVs and analyze ceramide levels via mass spectrometry to confirm pathway inhibition.

- Investigate the functional consequence of reduced sEV release using in vitro assays (e.g., cell migration or invasion co-culture assays).

Modulation of sEVs by Natural Compounds

Several natural compounds have been identified that modulate sEV biogenesis and secretion, providing both experimental tools and potential therapeutic leads.

- Protocol Example: Treatment with Cannabidiol (CBD) or Resveratrol [6]

- Cell Seeding: Seed cancer cells (e.g., prostate cancer PC3, glioblastoma, or hepatocellular carcinoma Huh7 cells) in standard culture plates.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with a natural compound.

- For Cannabidiol: Treat cells with CBD (e.g., at 1-10 µM) for 24 hours.

- For Resveratrol: Treat cells with Resveratrol (e.g., at 50-100 µM) for 24-48 hours.

- sEV Isolation and Analysis: Collect conditioned media and isolate sEVs via ultracentrifugation or polymer-based precipitation kits.

- Use NTA and protein quantification to measure changes in sEV release.

- Use Western blotting to analyze alterations in biogenesis-related proteins (e.g., Rab27a for Resveratrol).

- Use RNA sequencing or qPCR to profile changes in sEV miRNA cargo (e.g., miR-126 and miR-21 in glioblastoma cells after CBD treatment).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This table provides a curated list of essential reagents and tools used in the experimental study of sEV biogenesis, as featured in the cited research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Studying sEV Biogenesis

| Reagent / Tool | Specific Example(s) | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| siRNAs / shRNAs | siRNA targeting TSG101, HRS, ALIX, Rab27a [3] [9] | Genetic knockdown to interrogate the functional role of specific proteins in sEV biogenesis and secretion. |

| Pharmacological Inhibitors | GW4869 (nSMase2 inhibitor) [4]; Manumycin A [6] | Chemical inhibition of key enzymes to block specific biogenesis pathways (e.g., ceramide-dependent) and study the outcome. |

| Natural Compounds | Cannabidiol (CBD), Resveratrol, Honokiol [6] | Modulation of sEV synthesis, secretion, and cargo composition; studied for their antitumorigenic properties. |

| Antibodies for Characterization | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Alix, Anti-Calnexin [1] [10] [9] | Identification and validation of sEV isolates via Western blotting, flow cytometry, or immuno-EM. Calnexin is a negative marker for organelle contamination. |

| Isolation Kits | Polymer-based precipitation kits (e.g., ExoQuick, Total Exosome Isolation kit) [1] | Rapid and user-friendly isolation of sEVs from cell culture media or biological fluids, though purity must be validated. |

| Characterization Instruments | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] [9] | Physical characterization of sEVs: NTA for particle size and concentration; TEM for morphological analysis. |

The biogenesis of small extracellular vesicles is a sophisticated cellular process governed by multiple, interconnected pathways. The ESCRT-dependent machinery provides a structured, protein-driven mechanism for cargo sorting and vesicle formation, while ESCRT-independent pathways, particularly those reliant on ceramide and tetraspanins, offer complementary and essential routes for sEV generation. Lipids serve as both structural elements and active mediators in this process, with their metabolism in cancer cells directly influencing the composition and function of TDsEVs. A thorough understanding of these mechanisms is not only fundamental to cell biology but also critical for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic applications. The experimental tools and protocols outlined provide a roadmap for researchers to dissect these complex processes further, paving the way for novel strategies to modulate sEV biogenesis in disease contexts, particularly in cancer.

In the realm of cancer research, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) have emerged as critical mediators of intercellular communication, facilitating the remodeling of the tumor microenvironment and metastatic dissemination [6] [11]. The biological functions of these nanoscale vesicles are profoundly influenced by their lipid composition, which governs their biogenesis, release, and functional capacities [12] [13]. Among the diverse lipid species identified in sEVs, ceramide, cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and phosphatidylserine play particularly pivotal roles in the sEV lifecycle. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these four key lipids, detailing their mechanisms of action, altered metabolism in cancer, and implications for diagnostic and therapeutic development. Understanding these lipidic components is essential for advancing our knowledge of sEV biology in oncogenesis and exploring their potential as therapeutic targets.

Lipid Functions in sEV Biogenesis and Cargo Sorting

Ceramide: Master Regulator of ESCRT-Independent Budding

Ceramide plays a fundamental role in sEV biogenesis through its unique physicochemical properties. This conical-shaped lipid drives the inward budding of endosomal membranes to form intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs), a core mechanism of the ESCRT-independent pathway [13] [14]. The enzymatic generation of ceramide via neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2) from sphingomyelin provides the necessary molecular architecture for membrane curvature and vesicle formation [12]. Research demonstrates that inhibition of nSMase2 effectively reduces sEV production, highlighting ceramide's central role in this process [7]. In cancer cells, ceramide-enriched microdomains also facilitate the sorting of oncogenic miRNAs into sEVs, enhancing their tumor-promoting capabilities upon delivery to recipient cells [7].

Cholesterol: Modulator of Membrane Rigidity and Trafficking

Cholesterol serves as a critical structural component of sEV membranes, significantly influencing their rigidity, stability, and intracellular trafficking [12] [14]. This sterol lipid is typically enriched in sEVs compared to their parent cells and facilitates the formation of lipid raft microdomains that serve as platforms for sEV biogenesis and protein sorting [13]. Cholesterol regulates MVB migration along microtubules and subsequent fusion with the plasma membrane, directly impacting sEV release [12]. Cancer cells often exhibit altered cholesterol metabolism, leading to modified cholesterol content in sEVs that influences their signaling functions and contributes to pathological progression [7]. Studies have shown that cholesterol-lowering drugs like simvastatin can inhibit sEV biogenesis and secretion in vitro and in vivo, demonstrating the therapeutic potential of targeting cholesterol metabolism in sEV-mediated cancer progression [7].

Sphingomyelin: Structural Scaffold and Ceramide Precursor

Sphingomyelin represents a major sphingolipid in sEV membranes, serving both structural and signaling functions. It contributes to membrane integrity and forms ordered lipid domains that facilitate the selective incorporation of proteins and nucleic acids into developing vesicles [14]. As the direct metabolic precursor to ceramide, sphingomyelin occupies a crucial position in the sEV biogenesis pathway [7]. The conversion of sphingomyelin to ceramide via sphingomyelinases represents a key regulatory step in both exosome and microvesicle formation, with acid sphingomyelinase particularly involved in plasma membrane shedding [12]. Cancer-derived sEVs frequently exhibit altered sphingomyelin-to-ceramide ratios, which influence their biological activity and potential as diagnostic biomarkers [7].

Phosphatidylserine: Mediator of Cellular Uptake and Signaling

Phosphatidylserine (PS) is normally confined to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane but becomes externalized in sEVs, serving as a key recognition signal for recipient cells [13]. This exposed PS facilitates the cellular uptake of sEVs through interactions with various receptors, including TIM and TAM family receptors on recipient cells [13]. In the context of cancer, PS externalization on sEVs influences immune responses and promotes tumor progression [6]. Tumor-derived sEVs abundant in phosphatidylserine have been observed in ex vivo tumoroid cells that mimic mammalian tumors and their environment [6]. The exposure of PS on sEV surfaces also enables their detection using PS-binding agents like annexin V, providing a methodological approach for sEV quantification and isolation [12].

Table 1: Key Lipids in sEV Biogenesis and Their Functions

| Lipid | Primary Function in sEV | Biogenesis Pathway | Enzymatic Regulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramide | Drives membrane curvature and inward budding | ESCRT-independent | nSMase2, aSMase |

| Cholesterol | Modulates membrane rigidity and MVB trafficking | Both ESCRT-dependent and independent | ACAT, CYP51A1 |

| Sphingomyelin | Structural scaffold, ceramide precursor | Microvesicle formation | SM synthetase, aSMase |

| Phosphatidylserine | Facilitates cellular uptake, signaling | Plasma membrane shedding | Scramblase, flippase |

Altered Lipid Metabolism in Cancer sEVs

Cancer cells undergo significant metabolic reprogramming that profoundly influences the lipid composition of their secreted sEVs. Dysregulated lipid metabolism is now recognized as a hallmark of cancer, with key lipogenesis regulators including acetyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, and sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) frequently upregulated in malignant cells [7]. These alterations directly impact the lipid cargo of sEVs, enhancing their pro-tumorigenic functions.

Oncogenic sEVs exhibit distinct lipid profiles characterized by enrichment of specific lipid species that facilitate tumor progression. For instance, studies comparing prostate cancer cell-derived sEVs (PC-3 cells) with their parental cells demonstrated significant enrichment of glycosphingolipids, phosphatidylserine species, and long-chain sphingolipids in sEV membranes [14] [7]. These modifications enhance the stability of sEVs and increase their efficiency in delivering oncogenic signals to recipient cells within the tumor microenvironment.

The phospholipid composition of cancer sEVs also shows disease-specific alterations. Mass spectrometry analyses reveal that phosphatidylcholine typically constitutes 46%–89% of total lipid components in sEVs from various cancer cell lines, while sphingomyelin content varies significantly (2%–30%) depending on the cancer type [14]. Pancreatic cancer-derived sEVs (AsPC-1 cells), for example, exhibit unusually high sphingomyelin content (28%) compared to other cancer types [14]. These modifications influence sEV size, rigidity, and function, ultimately contributing to cancer pathogenesis.

Table 2: Lipid Alterations in Cancer-Derived sEVs

| Cancer Type | Observed Lipid Alterations in sEVs | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer | Enriched glycosphingolipids, PS 18:0/18:0 | Enhanced cellular uptake, signaling |

| Breast Cancer | High phosphatidylcholine (80-90%) | Increased membrane stability |

| Pancreatic Cancer | Elevated sphingomyelin (28%), diglycerides | Altered membrane rigidity, drug resistance |

| Glioblastoma | Increased cholesterol, ceramides | Promoted survival pathways |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Lyso-derivatives of phosphoglycerides | Enhanced inflammatory responses |

Methodologies for sEV Lipid Analysis

Isolation Techniques for Lipidomic Studies

The accurate analysis of sEV lipid composition requires rigorous isolation methods to obtain high-purity vesicle preparations. Ultracentrifugation remains the gold standard for sEV separation, effectively pelleting vesicles based on their size and density [11]. For enhanced purity, density gradient centrifugation can further separate sEVs from contaminating lipid particles and protein aggregates [11]. Alternative approaches include size-exclusion chromatography, which preserves vesicle integrity and biological activity, and immunoaffinity capture methods that target specific surface markers [11]. The choice of isolation technique significantly impacts subsequent lipidomic analyses, as different methods yield varying degrees of purity and recovery rates.

Lipidomic Analysis Workflow

Comprehensive lipid profiling of sEVs typically employs liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) platforms, which offer high sensitivity and resolution for detecting diverse lipid species [15]. The analytical workflow begins with lipid extraction from purified sEV preparations using organic solvents such as chloroform-methanol mixtures. The extracted lipids are then separated by reverse-phase or normal-phase chromatography before MS analysis [15].

High-resolution mass spectrometers enable the identification and quantification of thousands of lipid species based on their accurate mass and fragmentation patterns [15]. Specialized software tools process the raw LC-MS data through feature detection, lipid identification, and quantitative analysis. For modified lipid species (epilipids), specialized computational approaches are required due to their low abundance, structural diversity, and lack of reference standards in spectral libraries [15].

Functional Assays for Lipid Activity

Beyond compositional analysis, functional assays are essential for characterizing lipid activity in sEVs. Inhibition studies using pharmacological agents such as neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitors (GW4869) or statins provide insights into specific lipid pathways in sEV biogenesis and function [7]. Cellular uptake assays employing fluorescently labeled sEVs track lipid-dependent vesicle internalization and trafficking [13]. Lipid transfer studies monitor the intercellular movement of lipid cargo between donor and recipient cells, elucidating the signaling functions of sEV lipids in the tumor microenvironment [13].

Figure 1: sEV Lipidomics Workflow from Isolation to Data Analysis

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Lipid Functions

Inhibiting Ceramide-Mediated sEV Biogenesis

Purpose: To evaluate the role of ceramide in sEV formation and secretion using pharmacological inhibition. Reagents: GW4869 (nSMase2 inhibitor), cell culture medium, sEV isolation reagents, Western blot equipment. Procedure:

- Culture cancer cells (e.g., PC-3 prostate cancer cells) to 70% confluence.

- Treat cells with GW4869 (10-20 μM) or vehicle control for 24-48 hours.

- Collect conditioned medium and isolate sEVs using ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 70 minutes).

- Quantify sEV yield using nanoparticle tracking analysis or protein assay.

- Analyze ceramide content in sEVs by LC-MS and examine sEV markers (CD63, CD81) by Western blot.

- Assess functional consequences of reduced sEV secretion on recipient cell behaviors (migration, invasion).

Modifying Cholesterol Content in sEV Membranes

Purpose: To investigate how cholesterol depletion affects sEV biogenesis and function. Reagents: Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), simvastatin, cholesterol quantification kit, fluorescent cell dyes. Procedure:

- Culture cells in standard conditions until 80% confluence.

- Treat cells with MβCD (5-10 mM) or simvastatin (1-10 μM) for 24 hours to deplete cholesterol.

- Iserve sEVs from conditioned media via density gradient centrifugation.

- Quantify cholesterol content in sEVs using fluorometric or colorimetric assays.

- Label sEVs with fluorescent dyes (e.g., PKH67) and track their uptake by recipient cells using flow cytometry.

- Evaluate changes in sEV membrane rigidity using laurdan generalized polarization spectroscopy.

Analyzing Phosphatidylserine Externalization on sEVs

Purpose: To detect and quantify PS exposure on sEV surfaces and its functional significance. Reagents: Annexin V binding buffer, fluorescently conjugated Annexin V, flow cytometry or microscopy equipment. Procedure:

- Isolate sEVs using size-exclusion chromatography to preserve membrane integrity.

- Incubate sEVs with Annexin V-FITC in binding buffer containing calcium for 15 minutes in the dark.

- For flow cytometry analysis, use appropriately sized beads to capture sEVs before Annexin V staining.

- Quantify PS-positive sEV population using flow cytometry or single-particle analysis.

- Block PS with recombinant Annexin V to confirm PS-dependent uptake in functional assays.

- Correlate PS exposure levels with functional properties such as immune cell modulation or tumor cell uptake.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Lipids in sEVs

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | GW4869, Manumycin A, Simvastatin | Block specific lipid pathways in sEV biogenesis | Validate specificity with rescue experiments |

| Detection Reagents | Annexin V, Filipin, Bodipy-cholesterol | Visualize and quantify lipids in sEVs | Optimize concentration to avoid background |

| Isolation Kits | Ultracentrifugation kits, Size-exclusion columns, Immunobeads | Obtain high-purity sEVs for lipid analysis | Compare multiple methods for validation |

| Analytical Standards | Deuterated lipids, Sphingolipid mixtures, Cholesterol standards | Quantify lipid species via mass spectrometry | Use internal standards for accurate quantification |

| Cell Lines | PC-3, MDA-MB-231, B16-F10 | Study cancer-specific lipid alterations in sEVs | Characterize baseline lipid profiles first |

The intricate roles of ceramide, cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and phosphatidylserine in the sEV lifecycle represent a critical frontier in cancer biology. These lipids not only govern the biogenesis and function of sEVs but also undergo cancer-specific alterations that enhance tumor progression. Advanced lipidomic methodologies now enable comprehensive profiling of sEV lipid compositions, revealing their potential as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. As research in this field advances, targeting lipid pathways in sEV biogenesis offers promising strategies for interrupting tumor-promoting communication. Future studies focusing on the mechanistic relationships between specific lipid species and sEV functions will undoubtedly yield novel insights into cancer pathophysiology and therapeutic innovation.

Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) are membrane-bound nanoparticles ranging from 30-200 nm in diameter that serve as crucial mediators of intercellular communication within the tumor microenvironment [1] [16]. Often referred to as oncosomes when derived from cancer cells, these vesicles are loaded with a diverse molecular cargo—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—that mirrors the aggressive nature of their parental cells [17]. The biogenesis of sEVs occurs through a complex process involving the endosomal pathway, where early sorting endosomes mature into late sorting endosomes that invaginate to form multivesicular bodies (MVBs) containing intraluminal vesicles [1]. These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing their vesicular contents as sEVs into the extracellular space [16]. This process is regulated by both ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complexes Required for Transport)-dependent and ESCRT-independent mechanisms, with the latter involving ceramide-dependent pathways and tetraspanin proteins such as CD63, CD81, and CD9 [1] [18]. The lipid composition of sEVs plays a fundamental role in their formation, structure, and function, with cancer-derived sEVs exhibiting distinct lipidomic profiles that contribute to their tumorigenic potential [7]. This review comprehensively examines how tumor-derived sEVs function as oncosomes to modulate key aspects of cancer progression—angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune evasion—within the context of sEV biogenesis and lipid metabolism.

Biological Foundations of sEVs

Biogenesis and Cargo Sorting Mechanisms

The formation of sEVs is a meticulously orchestrated cellular process that governs both the quantity and quality of vesicles released. The classical ESCRT pathway employs four protein complexes (ESCRT-0, -I, -II, and -III) that work sequentially to recognize ubiquitinated membrane proteins, induce membrane budding, and facilitate vesicle scission [18]. Parallel ESCRT-independent pathways utilize lipid metabolites like ceramide, which induces negative membrane curvature through its cone-shaped structure, promoting vesicle budding [18]. Tetraspanin proteins (CD9, CD63, CD81) also contribute significantly to sEV biogenesis and cargo selection, forming specialized membrane microdomains that recruit specific protein and RNA cargo [18].

Cargo sorting into sEVs is highly selective and determines their functional impact on recipient cells. RNA-binding proteins such as hnRNPA2B1 recognize specific nucleotide motifs (e.g., GGAG) in miRNAs to facilitate their loading into sEVs [18]. Post-translational modifications, including sumoylation of hnRNPA2B1, further regulate this selective packaging process [18]. The lipid composition of the budding membrane also influences cargo incorporation, with certain lipid domains preferentially recruiting proteins and nucleic acids destined for export [7].

Lipidomic Architecture of Oncogenic sEVs

The lipid profile of sEVs is not merely structural but functionally significant in cancer progression. Cancer-derived sEVs exhibit a modified lipidomic composition that distinguishes them from sEVs produced by normal cells [7]. These alterations include enriched levels of specific lipid species that facilitate tumorigenic behaviors:

Table 1: Modified Lipid Profiles in Cancer-Derived sEVs and Their Functional Implications

| Lipid Category | Specific Lipid Species | Functional Role in Cancer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol | Cholesterol | Enhances membrane rigidity and stability; promotes signaling platform formation | [7] |

| Sphingolipids | Ceramide, Sphingomyelin | Critical for sEV biogenesis; mediates apoptosis resistance | [7] [18] |

| Phospholipids | Phosphatidylserine, Phosphatidylcholine | Externalized phosphatidylserine mediates immune cell inhibition | [7] |

| Bioactive Lipids | Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) | Acts as signaling molecules to promote migration, invasion, and angiogenesis | [7] |

| Fatty Acids | Saturated and unsaturated fatty acids | Saturated fatty acids increase membrane rigidity; unsaturated fatty acids enhance fluidity | [7] |

This modified lipid composition contributes to disease progression by enhancing sEV stability, facilitating cargo sorting, promoting recipient cell uptake, and directly activating oncogenic signaling pathways [7]. For instance, the elevated cholesterol content in cancer sEVs increases membrane rigidity and promotes the formation of signaling platforms that enhance oncogenic signaling upon delivery to recipient cells [7].

Multifunctional Roles of sEVs in Cancer Progression

Angiogenesis Induction

sEVs orchestrate tumor angiogenesis through the delivery of pro-angiogenic factors that activate endothelial cells. These vesicles transfer specific molecular cargo that reprogram vascular cells to support blood vessel formation:

Table 2: Pro-angiogenic Cargo in Tumor-Derived sEVs

| sEV Cargo Type | Specific Molecule | Mechanism of Action | Cancer Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Annexin II | Promotes endothelial cell migration and organization | Breast Cancer | [16] |

| Proteins | Tetraspanin 8 | Facilitates angiogenesis and metastasis | Pancreatic & Colon Cancer | [16] |

| miRNAs | miR-96-5p | Targets AMOTL2 to promote angiogenesis | Pancreatic Cancer | [19] |

| lncRNAs | linc-ROR | Mediates cancer cell-adipocyte crosstalk to promote tumor growth | Pancreatic Cancer | [19] |

| Cytokines | IL-6, VEGF | Directly stimulates endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation | Glioblastoma | [16] |

The pro-angiogenic effects of sEVs are further enhanced by hypoxic conditions within the tumor microenvironment. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) stimulate the expression and packaging of angiogenic mediators into sEVs, creating a feed-forward loop that sustains vascular development even under adverse conditions [19].

Metastatic Niche Formation

sEVs play a pivotal role in establishing the pre-metastatic niche—a supportive microenvironment in distant organs that facilitates the colonization of circulating tumor cells. These vesicles execute organotropic homing through specific integrins on their surfaces that determine their tissue distribution [20]. For instance, sEVs expressing integrin α6β4 preferentially home to lungs, while those with integrin αvβ5 target liver tissue [20].

The mechanism by which sEVs prepare pre-metastatic niches involves multiple coordinated processes. Breast cancer-derived sEVs transport miRNA-200b-3p that activates the AKT/NF-κB/CCL2 signaling cascade, recruiting myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) to lung tissue and creating an immunosuppressive environment conducive to metastasis [20]. Similarly, pancreatic cancer sEVs establish a pre-metastatic niche in the liver by suppressing Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) expression on dendritic cells and promoting fibrotic changes through the recruitment of macrophages and hepatic stellate cells [19]. sEVs also remodel the extracellular matrix by transferring matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and stimulating stromal cells to produce additional remodeling enzymes, thereby facilitating cancer cell invasion and colonization [16].

Immune Evasion Strategies

sEVs employ sophisticated mechanisms to suppress antitumor immunity, primarily through the surface expression of immune checkpoint proteins. Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) presented on sEVs directly interacts with PD-1 receptors on T cells, inhibiting their activation and effector functions [20] [21]. This sEV-mediated immune suppression occurs both locally within the tumor microenvironment and systemically, as sEVs can travel to lymphoid organs and inhibit T cell activation at a distance [20].

Beyond checkpoint protein presentation, sEVs facilitate immune evasion through additional mechanisms. They inhibit dendritic cell maturation, impairing antigen presentation and subsequent T cell priming [20]. sEVs also promote the expansion and recruitment of immunosuppressive cell populations, including MDSCs and M2 macrophages, through transferred cytokines and miRNAs [20]. Furthermore, sEV-associated cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-17 contribute to creating a pro-tumorigenic inflammatory milieu that supports immune evasion [20].

Experimental Methodologies for sEV Research

Isolation and Characterization Techniques

The study of sEVs requires specialized isolation techniques that separate these nanoscale vesicles from other extracellular components. The most commonly employed methods include:

Differential Ultracentrifugation: Considered the gold standard for sEV isolation, this technique employs sequential centrifugation steps at increasing speeds to pellet sEVs based on their size and density [1]. While it allows for processing large sample volumes, the high centrifugal forces can damage sEV structure and function [1].

Density Gradient Centrifugation: This approach separates sEVs based on their buoyant density, typically resulting in higher purity preparations compared to differential ultracentrifugation [1]. However, it is time-consuming and may not be suitable for processing large sample volumes [1].

Polymer-Based Precipitation: This method uses hydrophilic polymers to decrease sEV solubility, facilitating their precipitation from solution [1]. While technically simple and yielding high sEV recovery, it often co-precipitates non-sEV contaminants such as proteins and lipoproteins [1].

Following isolation, comprehensive characterization of sEVs is essential and typically involves multiple complementary techniques. Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) determines sEV size distribution and concentration, while transmission electron microscopy (TEM) provides visual confirmation of sEV morphology and structural integrity [1]. Western blot analysis for tetraspanin markers (CD9, CD63, CD81) and ESCRT-associated proteins (TSG101, ALIX) verifies the presence of sEV-specific proteins [1] [18].

Functional Assays

Understanding the functional role of sEVs in cancer progression requires sophisticated experimental approaches:

Uptake and Tracking Experiments utilize fluorescently labeled sEVs to visualize their internalization by recipient cells. These assays often employ lipophilic dyes (e.g., PKH67, DiD) or membrane-permeant dyes (e.g., CFSE) to label sEV membranes or internal contents, respectively [20]. Confocal microscopy and flow cytometry then track sEV uptake and distribution over time.

Angiogenesis Assays evaluate the pro-angiogenic potential of sEVs using in vitro models such as tube formation assays, where endothelial cells are cultured with sEVs on Matrigel or other basement membrane extracts [16]. The extent and complexity of tubular structures formed serve as indicators of angiogenic induction [16].

Immune Cell Function Assays examine the immunomodulatory effects of sEVs through T cell proliferation assays, cytokine production measurements, and immune cell cytotoxicity assessments [20]. These experiments typically involve co-culture systems where immune cells are exposed to sEVs followed by functional readouts [20].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for sEV Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolation Kits | Polymer-based precipitation kits, Membrane affinity columns | Rapid sEV isolation from biological fluids | Balance between yield, purity, and processing time |

| Characterization Antibodies | Anti-CD63, Anti-CD81, Anti-CD9, Anti-TSG101, Anti-Calnexin (negative marker) | sEV identification and quantification by Western blot, flow cytometry | Validate specificity for sEV proteins; use appropriate negative controls |

| Tracking Dyes | PKH67, DiD, CFSE, GFP-labeled tetraspanins | sEV uptake and trafficking studies | Optimize labeling concentration to avoid dye aggregation; include proper controls |

| Inhibition Reagents | GW4869 (neutral sphingomyelinase inhibitor), Dimethyl amiloride (inhibits MVB formation) | Investigating sEV biogenesis and secretion pathways | Assess potential off-target effects on cellular physiology |

| Lipidomics Tools | Mass spectrometry-based lipid profiling, Fluorescent lipid analogs | Analyzing sEV lipid composition and dynamics | Consider lipid extraction efficiency and coverage of lipid classes |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate key signaling pathways through which sEVs modulate angiogenesis, metastasis, and immune evasion.

sEV-Mediated Angiogenesis Signaling

sEV-Mediated Immune Evasion via PD-L1

sEV Biogenesis and Lipid Metabolism Interplay

sEVs function as sophisticated oncosomes that coordinate multiple aspects of cancer progression through their diverse molecular cargo and targeted delivery mechanisms. Their modified lipid composition not only facilitates biogenesis and stability but also actively contributes to their tumorigenic functions. The interconnected roles of sEVs in promoting angiogenesis, establishing pre-metastatic niches, and suppressing antitumor immunity highlight their central position in cancer biology.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms governing sEV lipidomics and cargo sorting, developing more refined isolation techniques to address sEV heterogeneity, and exploring the therapeutic potential of engineered sEVs as drug delivery vehicles. As our understanding of sEV biology deepens, these vesicles may serve as valuable biomarkers for early cancer detection and monitoring, as well as novel targets for therapeutic intervention aimed at disrupting their tumor-promoting functions.

Lipid metabolic reprogramming is a established hallmark of cancer, enabling tumors to meet the increased energetic and biosynthetic demands of rapid proliferation [22] [23]. This reprogramming encompasses two primary mechanisms: de novo lipogenesis, where cancer cells synthesize lipids internally, and enhanced lipid uptake, where they scavenge lipids from the external environment [24]. These processes provide essential components for membrane biosynthesis, energy production through fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and generation of signaling molecules that drive oncogenic pathways [22] [24]. In the context of small extracellular vesicle (sEV) biogenesis, lipids serve as both structural components and bioactive mediators, influencing vesicle formation, cargo sorting, and release [13] [7]. This review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying de novo lipogenesis and lipid uptake in cancer, their relationship to sEV biology, and the experimental approaches driving discovery in this field.

De Novo Lipogenesis in Cancer Cells

De novo lipogenesis is a metabolic pathway where cancer cells synthesize fatty acids and other lipids from precursor molecules, even when extracellular lipids are abundant. This process supports the high demand for membrane phospholipids, lipid signaling molecules, and energy storage compounds in rapidly proliferating tumors [24].

Key Enzymes and Regulatory Nodes

The lipogenic pathway is orchestrated by several rate-limiting enzymes that are frequently overexpressed in cancers:

- ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY): Catalyzes the conversion of mitochondrial-derived citrate into cytosolic acetyl-CoA, the fundamental building block for fatty acid synthesis. Its expression is often upregulated in cancer, increasing flux through the lipogenic pathway [24].

- Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC): Carboxylates acetyl-CoA to form malonyl-CoA in the committed step of fatty acid synthesis. This enzyme exists as two isoforms (ACC1 and ACC2) with ACC1 being primarily responsible for lipogenesis [22].

- Fatty acid synthase (FASN): A multi-enzyme complex that catalyzes the synthesis of palmitate from acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. FASN is significantly overexpressed in numerous cancers, including colorectal (CRC) and breast cancer (BC), and its expression often correlates with poor prognosis [22] [23].

- Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1): Introduces double bonds into saturated fatty acids to generate monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), which are essential for membrane fluidity and the formation of specific lipid species. SCD1 upregulation is a common feature in tumor cells [7].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in De Novo Lipogenesis and Their Roles in Cancer

| Enzyme | Reaction Catalyzed | Cancer Association | Therapeutic Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACLY | Citrate → Acetyl-CoA + Oxaloacetate | Upregulated in CRC and BC; supports acetyl-CoA pool | BMS-303141, Hydroxycitrate |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA → Malonyl-CoA | Overexpressed; regulates fatty acid synthesis and oxidation | ND-654, TOFA |

| FASN | Acetyl-CoA/Malonyl-CoA → Palmitate | Highly upregulated; poor prognostic marker | TVB-2640, Orlistat, C75 |

| SCD1 | Saturated FA → Monounsaturated FA | Increased MUFA production for membrane fluidity | A939572, MF-438 |

Transcriptional control of lipogenesis is predominantly mediated by Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Proteins (SREBPs), particularly SREBP-1c, which activate the expression of lipogenic genes like ACLY, ACC, and FASN [7]. Oncogenic signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt/mTOR, enhance SREBP activity and processing, creating a direct link between oncogenic transformation and lipid anabolism [7].

Connection to sEV Biogenesis

Lipids generated via de novo synthesis are integral to sEV biogenesis. Ceramide, synthesized de novo in the endoplasmic reticulum, plays a critical role in the ESCRT-independent pathway of intraluminal vesicle (ILV) formation within multivesicular bodies (MVBs). Its conical molecular structure promotes membrane curvature and inward budding [13] [7]. Furthermore, phosphoinositides such as PI(3)P and PI(4,5)P2, which are lipid signaling molecules, recruit and regulate the ESCRT machinery in the ESCRT-dependent pathway of sEV formation [13]. The lipid composition of the parental cell's membrane, heavily influenced by its lipogenic output, directly determines the lipid profile of the resulting sEVs [7].

Diagram 1: De Novo Lipogenesis Pathway and Connection to sEVs. Key lipogenic enzymes (ACLY, ACC, FASN, SCD1) convert nutrients into lipids that support sEV formation.

Lipid Uptake from the Tumor Microenvironment

In parallel to de novo synthesis, cancer cells exhibit a voracious appetite for extracellular lipids. This is particularly evident in tumors situated in lipid-rich environments, such as breast cancer in adipose tissue [23]. Lipid uptake provides a readily available source of building blocks and energy, bypassing the ATP-intensive process of de novo synthesis.

Key Transporters and Uptake Mechanisms

The internalization of exogenous lipids is mediated by specific membrane transporters and receptors:

- CD36 (Fatty Acid Translocase): A scavenger receptor that facilitates the uptake of long-chain fatty acids and oxidized low-density lipoproteins (OxLDLs) [22] [24]. CD36 is overexpressed in CRC, BC, and other cancers, where it promotes cancer cell proliferation, metastasis, and immune evasion by inducing lipid peroxidation in T cells [22] [23]. It is a marker of metastatic potential and a mediator of therapy resistance in HER2+ breast cancer [23].

- Fatty Acid Transport Proteins (FATPs): A family of six proteins (FATP1-6) that facilitate the uptake of long-chain and very-long-chain fatty acids. FATP5, for instance, is overexpressed in CRC and regulates the cell cycle [24].

- Fatty Acid Binding Proteins (FABPs): Intracellular chaperones that facilitate the trafficking and storage of fatty acids after their entry into the cell. FABP4 and FABP5 are highly implicated in cancer; they enhance lipid droplet formation, interact with oncogenic signaling pathways like EGFR, and mediate crosstalk between cancer cells, adipocytes, and tumor-associated macrophages in the TME [24] [23].

- Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR): Mediates the endocytic uptake of cholesterol-rich LDL particles. LDLR is overexpressed in many cancers, including BC, to satisfy the high demand for cholesterol to maintain membrane integrity and fluidity [23]. Elevated LDL levels have been correlated with increased liver metastasis in CRC [22].

Table 2: Key Lipid Transporters and Their Roles in Cancer

| Transporter | Lipid Substrate | Cancer Association | Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD36 | Long-chain FAs, OxLDL | Overexpressed; poor prognosis; pro-metastatic | Promotes FA uptake, metastasis, immune suppression |

| FATPs | Long/very-long-chain FAs | Upregulated in CRC, BC | Supports cell cycle progression, tumor growth |

| FABP4 | Intracellular FA chaperone | Elevated in obesity-associated BC | Links adipocytes, TAMs, and cancer cells |

| FABP5 | Intracellular FA chaperone | Overexpressed in CRC and TNBC | Modulates EGFR signaling, cell proliferation |

| LDLR | LDL-cholesterol | Upregulated in BC | Provides cholesterol for membrane synthesis |

The Role of the High-Fat Diet and Tumor Microenvironment

Epidemiological and experimental evidence links high-fat diets (HFD) and obesity to increased cancer risk and progression [22]. An HFD can alter the gut microbiota, increasing pathogenic bacteria that activate oncogenic pathways like CPT1A-ERK, thereby fueling CRC progression [22]. Furthermore, HFD-induced obesity disrupts CD4+ T-cell function in the TME, creating an immunosuppressive milieu that accelerates cancer progression and metastasis [22]. Adipocytes in the TME release fatty acids that are taken up by cancer cells via transporters like CD36 and FABP4, creating a parasitic relationship where the tumor feeds on the host's energy reserves [23].

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Lipid Metabolism

The study of lipid metabolism in cancer relies on a suite of advanced analytical and molecular techniques.

Lipidomics and Metabolomics

Untargeted Lipidomics provides a comprehensive profile of the lipid species present in a biological sample. This is typically performed using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Quadrupole Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF-MS) [25]. The workflow involves:

- Sample Preparation: Serum or plasma is typically extracted using a methanol-chloroform mixture for protein precipitation and lipid extraction.

- Chromatographic Separation: Lipids are separated on a reverse-phase C18 column.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Lipids are ionized (e.g., by electrospray ionization) and detected in both positive and negative modes to capture a wide range of lipid classes.

- Data Analysis: Software like MetaboAnalyst is used for peak alignment, normalization, and multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., OPLS-DA) to identify lipids that are differentially abundant between groups (e.g., early vs. late recurrence) [25].

Targeted Metabolomics focuses on quantifying a predefined set of lipid biomarkers. For example, a study on cholangiocarcinoma identified lysophosphatidylcholines (LysoPCs) and lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LysoPEs) as significantly altered in patients with recurrence, and used a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model to build a predictive diagnostic panel [25].

Functional Assays and Molecular Biology

- Lipid Uptake Assays: Fluorescently labeled fatty acids (e.g., BODIPY-labeled FAs) are used to track and quantify fatty acid uptake in vitro. Inhibition of transporters like CD36 with neutralizing antibodies or sulfo-N-succinimidyl oleate (SSO) can demonstrate their specific role.

- Genetic Manipulation: siRNA- or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockdown/knockout of key enzymes (e.g., FASN, ACLY) or transporters (e.g., CD36, FABP5) is used to elucidate their functional necessity for cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and tumor growth in vivo.

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Using isotopic tracers (e.g., ^13^C-glucose or ^13^C-acetate) allows researchers to track the incorporation of carbon atoms into newly synthesized fatty acids, providing a direct measure of de novo lipogenesis flux.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Lipid Metabolism in Cancer

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| TVB-2640 | Small Molecule Inhibitor | FASN inhibition | Suppresses de novo lipogenesis in preclinical models; in clinical trials. |

| SSO | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Irreversible CD36 inhibitor | Blocks exogenous fatty acid uptake in functional assays. |

| BODIPY FL C16 | Fluorescent Probe | Fluorescent fatty acid analog | Visualizing and quantifying fatty acid uptake in live cells. |

| ^13^C-Acetate | Stable Isotope Tracer | Metabolic flux analysis | Tracing carbon flux through the de novo lipogenesis pathway. |

| Anti-CD36 Antibody | Neutralizing Antibody | Blocks CD36 receptor function | Inhibits ligand binding; used in vitro and in vivo. |

| siRNA pools (e.g., against SREBP1) | Genetic Tool | Gene knockdown | Silencing expression of key transcriptional regulators of lipogenesis. |

| Simvastatin | Small Molecule Inhibitor | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor | Reduces cholesterol synthesis and has been shown to inhibit sEV biogenesis. |

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Translation

The strategic inhibition of lipid metabolic pathways presents a promising avenue for cancer therapy.

- Targeting De Novo Lipogenesis: The FASN inhibitor TVB-2640 has shown efficacy in preclinical models and is undergoing clinical evaluation. It is particularly investigated in combination regimens to overcome therapy resistance [24].

- Targeting Lipid Uptake: Anti-CD36 antibodies are being explored to block the procancerous functions of this transporter, potentially inhibiting metastasis and reversing immunosuppression [22] [23].

- Repurposed Drugs: Statins, which inhibit cholesterol synthesis, have demonstrated anti-tumor effects and can modulate sEV biogenesis and secretion, as shown with simvastatin in macrophages and dendritic cells [7].

The analysis of lipid species in patient serum or in sEVs isolated from biofluids is a burgeoning area for biomarker discovery. Specific phospholipid signatures, such as alterations in LysoPCs, show diagnostic and prognostic potential for cancers like pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and cholangiocarcinoma [25] [26]. Machine learning models applied to these lipidomic datasets are enhancing the accuracy of cancer detection and recurrence prediction [25].

Diagram 2: Lipid Uptake from the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer cells upregulate transporters (CD36, FATPs, FABPs, LDLR) to scavenge lipids from adipocytes and circulation, fueling various protumorigenic processes.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem where dynamic communication between cancer cells and various stromal components dictates tumor progression and therapy response. This technical guide elucidates the intricate, bidirectional crosstalk mediated by small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) and reprogrammed lipid metabolism within the TME. We detail how lipids influence sEV biogenesis, composition, and function, and conversely, how sEVs transmit lipid-related signals that reprogram recipient cells, fostering an immunosuppressive, pro-metastatic niche. Supported by contemporary single-cell analyses and mechanistic studies, this review provides a framework for understanding these pathways and exploiting them for diagnostic and therapeutic innovation in oncology.

The concept of the TME as a passive bystander in tumorigenesis has been fundamentally overturned. It is now recognized as an active participant, composed of malignant cells, immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), endothelial cells, and a myriad of signaling molecules. Two key processes underpinning communication within this milieu are lipid metabolic reprogramming and sEV-mediated signaling. Lipid metabolism reprogramming is a hallmark of cancer, providing energy, building blocks for membranes, and signaling molecules to support rapid proliferation [27]. Concurrently, sEVs—nanoscale vesicles (50-200 nm) secreted by all cells—emerge as critical messengers, shuttling functional proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids to remodel the TME [2]. The interplay between these two systems creates a feed-forward loop of pro-tumorigenic signaling. This guide dissects the molecular mechanisms of this crosstalk, presents key experimental data, and outlines translational applications for cancer research and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms: How Lipids and sEVs Co-define the Tumor Microenvironment

Biogenesis of sEVs and the Critical Role of Lipids

sEVs originate through two primary pathways, both heavily influenced by lipids. The formation of exosomes, a major subtype of sEVs, begins with the endosomal system. The inward budding of the limiting membrane of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) forms intraluminal vesicles (ILVs), which are released as exosomes upon MVB fusion with the plasma membrane [2] [28]. This process is regulated by the Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport (ESCRT) machinery, which is itself recruited and activated by phosphoinositides like PI(3)P and PI(4,5)P2 [6] [28]. An ESCRT-independent pathway is triggered by ceramide, whose cone-shaped structure facilitates membrane curvature and inward budding [6] [2]. Other lipids, including cholesterol and sphingomyelin, contribute to the stability and formation of membrane microdomains essential for this process [6] [28].

In contrast, microvesicles (another class of sEVs) are formed via the direct outward budding and fission of the plasma membrane. This process is initiated by the loss of membrane asymmetry, particularly the externalization of phosphatidylserine (PS), and the local enrichment of cholesterol and sphingomyelin in lipid rafts. Ceramide again plays a role in membrane scission, often in concert with the ESCRT machinery [28]. The lipid composition not only governs vesicle formation but also determines the sorting of specific cargo into sEVs.

sEV-Mediated Lipid Signaling in the TME

Once released, sEVs serve as vehicles for intercellular communication, transmitting oncogenic signals that reshape the TME.

- Immunosuppression: Tumor-derived sEVs can suppress anti-tumor immunity. In metastatic Estrogen Receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, scRNA-seq revealed enriched populations of CCL2+ macrophages and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), which collectively contribute to an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Analysis of cell-cell communication showed a marked decrease in tumor-immune cell interactions in metastatic tissues, indicating immune evasion [29].

- Metastasis and Metabolic Reprogramming: sEVs facilitate the establishment of the pre-metastatic niche. They carry and transfer multifunctional proteins like Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs), which promote extracellular matrix remodeling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [6]. Furthermore, a lipid metabolism-related gene signature derived from ER+ breast cancer patients reflects TME heterogeneity and is associated with worse prognosis after tamoxifen treatment, underscoring the link between lipid signaling and disease progression [30].

- Cross-Tissue Communication: Emerging evidence highlights sEVs in mediating pathological communication between tumors and distant organs. For instance, sEVs derived from doxorubicin-treated breast cancer cells are enriched with miR-338-3p. When taken up by cardiomyocytes, these sEVs exacerbate doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by targeting anti-ferroptotic genes, illustrating a novel mechanism of heart-tumor crosstalk [31].

Lipid Metabolism Reprogramming in Cancer and Immune Cells

Cancer cells undergo significant lipid metabolic rewiring to support their growth demands. Key alterations include:

- Increased Fatty Acid Synthesis: Upregulation of enzymes like ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC), and Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) drives the de novo synthesis of fatty acids from acetyl-CoA [27].

- Cholesterol Synthesis: The mevalonate pathway, controlled by the rate-limiting enzyme HMGCR, is hyperactive in many cancers, providing cholesterol for membrane integrity and signaling [27].

- Lipid Uptake and Storage: Overexpression of transporters like CD36 facilitates the uptake of exogenous fatty acids, which are stored as triglycerides in lipid droplets [27].

This metabolic reprogramming extends to immune cells within the TME, but with functional consequences for anti-tumor immunity. For example, lipid accumulation in dendritic cells (DCs) and T cells can impair their antigen-presentation and effector functions, contributing to an immunosuppressive landscape [27].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Evidence

Natural Compounds Modulating sEVs and Lipid Metabolism

Natural compounds (NCs) serve as potent experimental tools to dissect the sEV-lipid axis and hold therapeutic potential. The following table summarizes the effects of key NCs.

Table 1: Natural Compounds as Modulators of sEV Biology and Lipid Metabolism

| Natural Compound | Source | Direct Effect on sEVs | Impact on Lipid Metabolism/Pathways | Overall Regulatory Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manumycin A | Streptomyces species | Reduces exosome secretion by ~10-fold in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) cells [6]. | Inhibits Ras/Raf/ERK1/2 signaling [6]. | Sensitizes CRPC to enzalutamide; antitumor effects [6]. |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | Cannabis sativa | Reduces exosome and microvesicle release in prostate, liver, and breast cancer cells [6]. | Alters microRNA cargo (e.g., increases miR-126, decreases miR-21) [6]. | Overcomes chemoresistance; exhibits antitumor activity [6]. |

| Resveratrol | Grapes, berries | Blocks exosome secretion by downregulating Rab27a in liver cancer cells (Huh7) [6]. | Increases CD63 and Ago2 levels in colorectal adenocarcinoma cells [6]. | Antiproliferative and anti-migratory effects [6]. |

| Honokiol | Magnolia genus | Increases drug bioavailability when loaded into exosomes; identified as a P-glycoprotein inhibitor [6]. | Specific lipid effects not yet fully explored [6]. | Enhances targeted delivery and antitumor efficacy [6]. |

Lipid Metabolism-Related Gene Signatures in Cancer Prognosis

Transcriptomic analyses have established a firm link between lipid metabolism and clinical outcomes. A prognostic model based on lipid metabolism-related genes was developed for ER+ breast cancer patients treated with tamoxifen. This signature stratified patients into high- and low-risk groups, with the high-risk group exhibiting worse survival outcomes (5-year overall survival AUC of 0.858). The high-risk group was characterized by enrichment of M0 macrophages and amplified SPP1 interactions, linking lipid reprogramming to immunosuppression and poor prognosis [30].

Single-Cell Resolution of the TME

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) of primary and metastatic ER+ breast cancer has revealed the cellular states underpinning TME heterogeneity. Key findings include:

- Genomic Instability: Malignant cells from metastatic samples showed higher Copy Number Variation (CNV) scores than primary tumors, indicating greater genomic instability [29].

- Immune Cell Shifts: Primary tumors were enriched with FOLR2+ and CXCR3+ pro-inflammatory macrophages. In contrast, metastatic lesions harbored more CCL2+ and SPP1+ pro-tumorigenic macrophages and exhausted T cells [29].

- Pathway Alterations: Primary breast cancer samples displayed increased activation of the TNF-α signaling pathway via NF-κB, suggesting a potential therapeutic target distinct from metastatic disease [29].

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for sEV and Lipid Research

Isolation and Drug Loading into Cancer Cell-Derived sEVs

The use of sEVs as drug delivery vehicles requires robust and reproducible isolation and loading protocols. The following workflow, adapted from a study using MCF-7 breast cancer cell-derived sEVs for doxorubicin (Dox) delivery, provides a detailed methodology [32].

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for sEV-based Drug Delivery System

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Reagents/Equipment | Function/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Culture & EV Collection | Culture MCF-7 cells in RPMI-1640 medium without FBS for 48h. Collect conditioned medium [32]. | RPMI-1640 medium, FBS, centrifuge, filters (0.22 µm) [32]. | Serum-free conditions prevent FBS-EV contamination. |

| 2. sEV Isolation & Purification | Sequential centrifugation (300 ×g, 2000 ×g) to remove cells/debris. Ultrafiltration to concentrate. Purify via Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) on a Sepharose CL-2B column [32]. | Ultracentrifuge, Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters, Sepharose CL-2B resin [32]. | SEC provides high-purity sEVs with intact biological activity. |

| 3. sEV Characterization | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) for size/concentration. Western Blot for markers (CD63, CD81). Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphology [32]. | NTA instrument, antibodies (anti-CD63, anti-CD81), TEM [32]. | Confirms isolation of sEVs and assesses quality. |

| 4. Drug Loading | Extrusion Method: Mix purified sEVs with Dox solution. Freeze-thaw, then extrude through porous membranes (e.g., 200 nm). Compare with passive incubation [32]. | Extrusion device, porous membranes, Doxorubicin hydrochloride [32]. | Extrusion provides superior loading efficiency over passive incubation. |

| 5. Functionalization & Targeting | Immobilize targeting peptides (e.g., APRPG peptide for VEGFR-1) on sEV surface via chemical conjugation or genetic engineering [32]. | APRPG peptide, crosslinkers (e.g., Sulfo-SMCC) [32]. | Enhances specific homing to target cancer cells. |

| 6. In vitro/In vivo Validation | Assess cytotoxicity (CCK-8 assay) in cancer vs. normal cell lines. Evaluate tumor homing and inhibition in xenograft mouse models (e.g., MCF-7-bearing mice) [32]. | CCK-8 assay kit, immunofluorescence imaging, mouse xenograft model [32]. | Validates targeting and therapeutic efficacy of the sEV-Dox system. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for sEV and Lipid Metabolism Research

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sepharose CL-2B | Isolation Tool | Matrix for SEC, enabling high-purity isolation of sEVs from biofluids or conditioned media [32]. |

| APRPG Peptide | Targeting Ligand | Binds VEGFR-1 on cancer cells; used to functionalize sEVs for targeted drug delivery [32]. |

| Anti-CD63 / CD81 Antibodies | Characterization | Canonical exosome markers used in Western Blot, flow cytometry, or immuno-EM to identify and validate sEV isolates [32]. |

| InferCNV / CaSpER | Bioinformatics Tool | Algorithms used with scRNA-seq data to infer copy number variations in malignant cells, revealing genomic instability [29]. |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | Small Molecule Inhibitor | Natural compound used experimentally to inhibit sEV release and alter their miRNA cargo, probing sEV function [6]. |

| RBMX siRNA | Genetic Tool | Knocking down this RNA-binding protein disrupts the packaging of specific miRNAs (e.g., miR-338-3p) into sEVs [31]. |

Visualization of Key Pathways and Workflows

Bidirectional Lipid-sEV Crosstalk in the TME

Diagram Title: Bidirectional sEV-Lipid Crosstalk in Tumor Microenvironment

Experimental Workflow for sEV-Based Drug Delivery

Diagram Title: sEV-Based Drug Delivery Development Workflow

The TME functions as a central hub where lipid metabolism and sEV communication are inextricably linked. Lipids are not merely structural components but active players in sEV biogenesis and signaling. In return, sEVs act as systemic couriers of lipid-related oncogenic signals, reprogramming immune responses, fueling metastasis, and mediating cross-organ damage. Decoding this complex dialogue is paramount.

Future research must leverage advanced single-cell and spatial 'omics' technologies to map lipid-sEV interactions with cellular resolution in human tumors. Therapeutically, targeting key nodes in this axis—such as using natural compounds to modulate sEV secretion or engineering sEVs for targeted drug delivery—holds immense promise. Furthermore, the lipid and miRNA profiles of circulating sEVs offer a fertile ground for developing novel, non-invasive biomarkers for early cancer detection, prognosis, and monitoring therapeutic resistance. By integrating the fields of lipidomics and sEV biology, researchers and drug developers can unlock new frontiers in precision oncology.

From Bench to Bedside: sEV and Lipid Analysis for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

Advanced Isolation and Characterization Techniques for sEVs

Small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), commonly defined as membrane-bound particles ranging from 30 to 200 nanometers in diameter, have emerged as crucial mediators of intercellular communication and promising biomarkers in cancer research [33] [1]. These nanoparticles carry a diverse cargo of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids that reflect their cell of origin, providing a window into pathological states [34] [35]. Their involvement in modulating the tumor microenvironment, facilitating epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and promoting metastasis underscores their significance in oncology [6]. However, the translational potential of sEVs is critically dependent on the isolation of highly pure vesicles and their comprehensive characterization, areas where methodology remains largely unstandardized [33] [36]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of current advanced techniques for sEV isolation and characterization, with particular emphasis on their applications in studying sEV biogenesis and lipid metabolism in cancer.

sEV Biogenesis and Lipid Metabolism in Cancer

Molecular Mechanisms of sEV Biogenesis

The formation of sEVs occurs through two primary pathways: the endosomal pathway resulting in exosomes, and plasma membrane budding yielding microvesicles [34] [35]. The endosomal pathway begins with the inward budding of the endosomal membrane, forming intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) within multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These MVBs subsequently fuse with the plasma membrane, releasing ILVs as exosomes into the extracellular space [1]. This process is regulated by the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, though ESCRT-independent pathways also exist [6]. The second pathway involves direct budding and fission of the plasma membrane, producing microvesicles ranging from 100-1000 nm [34].

Lipids play a fundamental role in sEV biogenesis beyond their structural function. Ceramide, an essential lipid involved in cellular signaling, has been shown to trigger budding of exosomes without the ESCRT system [6]. Other lipids including cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and phosphatidylserine participate in the formation, secretion, signaling, and uptake of exosomes [6]. The phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) is abundantly present in the inner leaflet of the cell membrane and is also found primarily in sEVs released from tumoroid cells that mimic mammalian tumors [6].

Lipid-Driven sEV Modulation in Cancer Progression

Cancer cells exhibit distinct alterations in their lipid metabolism that are reflected in the lipid composition of their secreted sEVs. These modifications influence both the biogenesis and function of sEVs in cancer progression. The lipid composition of sEV membranes affects their rigidity, fluidity, and targeting specificity, ultimately determining their capacity to interact with recipient cells [37].

In the context of cancer, sEVs serve as vehicles for transferring oncogenic lipids and lipid-modified signaling proteins that promote tumor growth and metastasis. For instance, cancer-derived sEVs have been shown to transport phosphatidylserine, which can influence immune recognition and tumor microenvironment remodeling [6]. Additionally, alterations in the lipid profile of sEVs have been identified in various chronic diseases, including cancers, making them suitable biomarkers and therapeutic targets [6]. Recent lipidomic analyses of sEVs have revealed distinct differences in lipid chain lengths and saturation levels that affect key pathways such as sphingolipid and neurotrophin signaling [38].

Table 1: Key Lipids in sEV Biogenesis and Function

| Lipid Class | Role in sEV Biology | Significance in Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| Ceramide | Triggers ESCRT-independent budding; regulates ILV formation | Modulates sEV release from cancer cells; potential therapeutic target |

| Phosphatidylserine | Externalized in apoptosis; sEV membrane component | Immunomodulatory effects; promotes tumor immune evasion |

| Cholesterol | Regulates membrane fluidity and rigidity | Affects sEV stability and recipient cell uptake; often elevated in cancer sEVs |

| Sphingomyelin | Contributes to membrane microdomain organization | Influences sEV signaling capabilities; altered in cancer sEVs |

| Sphingolipids | Signaling molecules in sEV pathways | Key role in neurotrophin signaling affected in cancer |

Advanced sEV Isolation Techniques

The selection of an appropriate isolation method is critical for obtaining sEVs of sufficient purity and yield for downstream applications. Method choice depends on multiple factors including sample type, volume, required purity, and intended downstream analysis [34].

Comparative Analysis of Isolation Methodologies

Ultracentrifugation (UC) remains the most widely used technique for sEV isolation, often considered the "gold standard" [1]. This method employs sequential centrifugation steps at increasing speeds, typically culminating at 100,000-160,000×g to pellet sEVs [39]. While UC allows for processing of large sample volumes and doesn't require specialized chemicals, it is time-consuming, requires expensive equipment, and may cause vesicle damage or aggregation [33] [1]. Additionally, UC pellets often contain non-vesicular contaminants, including protein aggregates and lipoproteins [36].

Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) separates sEVs based on their hydrodynamic radius using porous beads. Smaller molecules enter the pores and are delayed, while sEVs elute in earlier fractions [33]. SEC preserves vesicle integrity and function, provides good purity, and is compatible with various biological fluids [39]. However, it offers limited sample processing capacity and may not effectively separate sEVs from similarly sized particles [33].