Lipid Metabolite Signatures in Diabetic Complications: A Comparative Review of Pathophysiology, Biomarkers, and Clinical Applications

Diabetic microvascular complications, including kidney disease, retinopathy, and neuropathy, are major drivers of morbidity, yet their progression varies significantly among individuals.

Lipid Metabolite Signatures in Diabetic Complications: A Comparative Review of Pathophysiology, Biomarkers, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

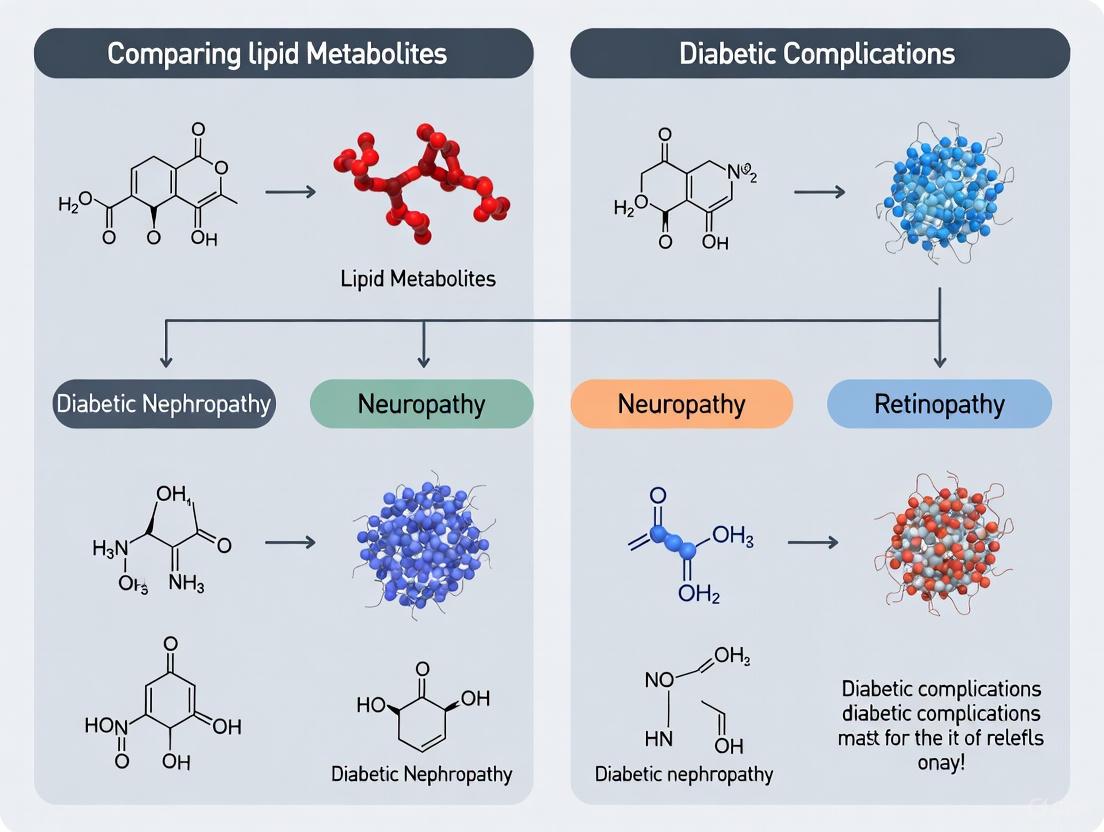

Diabetic microvascular complications, including kidney disease, retinopathy, and neuropathy, are major drivers of morbidity, yet their progression varies significantly among individuals. Emerging evidence underscores that distinct lipid metabolic reprogramming underpins each complication, offering a new layer of understanding beyond traditional risk factors. This article synthesizes recent findings from metabolomic and lipidomic studies to compare and contrast the specific lipid signatures associated with diabetic kidney disease, retinopathy, and neuropathy. We explore the pathophysiological roles of lipid droplet dynamics, lipotoxicity, and novel biomarkers like the Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) and Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP). Furthermore, we evaluate advanced mass spectrometry methodologies for biomarker discovery, discuss the integration of machine learning for data stratification, and assess the translational potential of lipid metabolites for early diagnosis, risk stratification, and targeted therapeutic interventions. This comprehensive analysis aims to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational resource for innovating in the prevention and management of diabetic complications.

The Landscape of Lipid Dysregulation in Diabetic Microvascular Complications

Lipid metabolic reprogramming, a fundamental adaptation of cellular metabolism under diabetic conditions, is increasingly recognized as a critical driver in the pathogenesis of diabetes and its complications. Under the persistent metabolic stress of diabetes, cells throughout the body—from pancreatic beta cells to renal cells—undergo significant alterations in their lipid handling, including increased lipid uptake, impaired fatty acid oxidation, and enhanced lipid synthesis [1] [2]. These changes result in the toxic accumulation of lipid species such as free fatty acids, diacylglycerol, and ceramides, a state known as lipotoxicity [1]. Lipotoxicity, in turn, triggers cascades of inflammation, fibrosis, and cellular dysfunction, accelerating damage in target organs like the kidneys, retina, and blood vessels [1] [3]. This article provides a comparative analysis of lipid metabolic alterations across major diabetic complications, synthesizing current molecular insights, profiling data, and experimental approaches that are shaping this frontier of metabolic research.

Comparative Data on Lipid Alterations in Diabetic Complications

The landscape of lipid dysregulation varies significantly across diabetic complications, both in the specific lipid species involved and their compartmentalization. The following tables synthesize key quantitative findings from recent clinical and omics studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Dysregulated Lipid Pathways in Diabetic Complications

| Diabetic Complication | Key Dysregulated Lipid Pathways | Accumulated Lipid Species | Major Cellular Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) | Increased lipid influx (CD36, FATP2), Impaired fatty acid oxidation, Enhanced lipid synthesis (FASN, ACC) [1] [2] | Free Fatty Acids (FFAs), Diacylglycerol (DAG), Ceramides [1] [2] | Inflammation, Renal fibrosis, Podocyte & tubular cell dysfunction [1] [2] |

| Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) | Sphingomyelin-Ceramide pathway, Phosphatidylcholine metabolism, De novo lipogenesis [4] | Ceramides, Sphingomyelins, Lysophosphatidylcholine [4] | Retinal ganglion cell death, Neuroinflammation, Breakdown of blood-retinal barrier [4] |

| Pancreatic Beta Cell Dysfunction | Imbalanced esterification/oxidation, Enhanced lipid synthesis, LD dynamics disruption [3] [5] | Triglycerides (in LDs), DAG, Ceramides [3] [5] | Impaired GSIS, ER stress, Apoptosis, Dedifferentiation [5] |

Table 2: Quantitative Lipid Biomarker Performance for Predicting Complications

| Biomarker / Index | Calculation | Association with DKD (Weighted Mean Difference, WMD) | Predictive Performance for DKD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP) | [WC (cm) - 65] × TG (mmol/L) (Men); [WC (cm) - 58] × TG (mmol/L) (Women) [6] | WMD: 12.67 (95% CI: 7.83–17.51); P < .01 [6] | OR per 1-unit increase: 1.005 (95% CI: 1.003–1.006); P < .01 [6] |

| Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) | log10(TG/HDL-C) [6] | WMD: 0.11 (95% CI: 0.03–0.19); P < .01 [6] | OR per 1-unit increase: 1.08 (95% CI: 1.04–1.12); P < .01 [6] |

| Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) | (WC/39.68 + BMI/1.88) × (TG/1.03) × (1.31/HDL) (Men); (WC/36.58 + BMI/1.89) × (TG/0.81) × (1.52/HDL) (Women) [6] | WMD: 0.63 (95% CI: 0.38–0.89); P < .01 [6] | OR per 1-unit increase: 1.05 (95% CI: 1.03–1.07); P < .01 [6] |

Table 3: Urinary Lipid Metabolites Associated with Rapid DKD Progression [7]

| Metabolite Class | Specific Metabolites (Elevated in Fast Decliners) | Experimental Measurement | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramides | Multiple species identified | Targeted UPLC/TQMS | Strongly associated with the highest quartile of eGFR decline. |

| Diacylglycerols (DAG) | Multiple species identified | Targeted UPLC/TQMS | Baseline levels were significantly elevated in patients with subsequent rapid kidney function loss. |

| Other Complex Lipids | 21 significantly upregulated lipid metabolites in DKD vs. uncomplicated T2D | Targeted UPLC/TQMS | A panel of 8-9 candidate lipids predicted future decline better than albuminuria or eGFR alone. |

Experimental Protocols for Lipid Metabolic Research

Targeted Lipidomics for Biomarker Discovery

Objective: To identify and quantify specific lipid metabolites in biofluids (e.g., urine, serum) that predict the development or progression of diabetic complications.

Protocol Summary (as used in DKD studies [7]):

- Sample Collection: Collect fasting spot urine or serum samples. Standardize collection protocols to minimize pre-analytical variability.

- Sample Preparation: Mix a 20 μL aliquot of urine with 120 μL of a standard solution containing 508 targeted lipid metabolites. After centrifugation, derivatize the supernatant with freshly prepared reagents at 60°C for 1 hour.

- Instrumental Analysis: Analyze samples using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Targeted Quantification Mass Spectrometry (UPLC/TQMS). A Waters ACQUITY UPLC system with a XEVO TQ-S mass spectrometer is typically used.

- Data Processing: Process raw data files with specialized software (e.g., Targeted Metabolome Batch Quantification - TMBQ). Normalize all metabolite concentrations to urinary creatinine to correct for urine concentration.

- Quality Control: Apply stringent QC filters: signal-to-noise ratio >10, coefficient of variation <15% in pooled QC samples, and a detection rate >80% across all samples.

Bioinformatics Interrogation of Metabolic Reprogramming

Objective: To identify key metabolic reprogramming-related genes (MRRGs) and pathways from transcriptomic data of tissues affected by diabetic complications.

Protocol Summary (as applied to Diabetic Nephropathy [8] [9]):

- Data Acquisition: Source relevant transcriptome datasets (e.g., GSE30528, GSE96804) from public repositories like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

- Data Preprocessing: Perform batch effect correction on combined datasets using the

svaR package and the ComBat method. Normalize the expression matrix. - Identification of MRRGs: Obtain a list of MRRGs from the GeneCards database (search: "Metabolic Reprogramming," relevance score >4). Cross-reference these with differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from the processed datasets to find metabolic reprogramming-related DEGs (MRRDEGs).

- Enrichment and Network Analysis: Conduct functional enrichment analyses (GO, KEGG) on MRRDEGs using

clusterProfiler. Construct Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks (e.g., via STRING database) and apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest) or network tools (e.g., CytoHubba) to identify hub genes. - Validation: Validate the diagnostic value of hub genes using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis and confirm their expression patterns with experimental methods like qRT-PCR.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The pathological remodeling of lipid metabolism in diabetes is driven by interconnected signaling pathways that respond to the diabetic milieu. The core pathway linking hypoxia and inflammation to lipid accumulation in complications like Diabetic Kidney Disease is summarized below.

The typical workflow for a multi-omics study investigating lipid metabolic reprogramming, from sample collection to biomarker identification, is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Resources for Investigating Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming

| Tool / Reagent | Primary Function | Example Application in Diabetes Research |

|---|---|---|

| UPLC/TQMS Systems | High-sensitivity identification and quantification of lipid species in complex biological samples. | Targeted lipidomic profiling of 508 lipid metabolites in urine/serum for biomarker discovery [7]. |

| GeneCards Database | Collates information on human genes from multiple genomic data repositories. | Sourcing Metabolic Reprogramming-Related Genes (MRRGs) with relevance scores for transcriptomic studies [8] [9]. |

| STRING Database | Resource for predicting and analyzing Protein-Protein Interactions (PPI). | Constructing PPI networks from metabolic reprogramming-related DEGs to identify hub genes [9]. |

| sva R Package | Correction of batch effects in high-throughput genomic data. | Removing technical variability when integrating multiple transcriptomic datasets (e.g., GSE30528, GSE96804) [8] [9]. |

| limma R Package | Differential expression analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. | Identifying genes significantly up- or down-regulated in diabetic nephropathy vs. control samples [8] [9]. |

| clusterProfiler R Package | Functional enrichment analysis of gene lists. | Performing GO and KEGG pathway analysis to interpret biological roles of MRRGs in diabetic complications [8] [9]. |

Lipid droplets (LDs) are dynamic, ubiquitous organelles central to cellular lipid and energy homeostasis. In metabolic health, they sequester and release lipids in response to nutrient fluctuations. However, in the context of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), dysregulated LD dynamics contribute significantly to ectopic lipid deposition and the development of lipotoxicity in non-adipose tissues [10] [11]. This pathophysiological process is a key driver of insulin resistance and the progression of diabetic complications across multiple organ systems [10] [12]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of LD dynamics and ectopic lipid deposition in target organs, framing the discussion within the broader context of lipid metabolites and diabetic complications research. It is designed to support researchers and drug development professionals by synthesizing current pathophysiological insights, experimental data, and methodologies.

Physiological and Pathological Roles of Lipid Droplets

Core Structure and Dynamics of Lipid Droplets

Lipid droplets possess a unique architecture, consisting of a neutral lipid core (composed of triglycerides and cholesteryl esters) enclosed by a phospholipid monolayer decorated with a specific set of proteins [11]. Their life cycle is governed by a coupled process of formation and degradation:

- Biogenesis: Occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, where neutral lipids synthesized by enzymes like DGAT1/2 accumulate to form an oil lens that subsequently buds off [10] [11].

- Degradation: Primarily occurs through two pathways: enzymatic hydrolysis (lipolysis) by lipases like ATGL and HSL, and selective autophagy (lipophagy) [10].

Lipid Droplet Dynamics in Metabolic Homeostasis and Disease

Under physiological conditions, LDs are protective. In pancreatic β-cells, they participate in lipid metabolism that regulates insulin secretion and isolate harmful lipids to protect against nutrient excess damage [10]. In adipose tissue, LDs respond to nutrient fluctuations, releasing free fatty acids (FFAs) and glycerol to influence systemic insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis [10].

Under the pathological conditions of T2DM, LD dynamics become dysregulated. Abnormal LD accumulation leads to ectopic lipid deposition in non-adipose tissues such as the liver, skeletal muscle, heart, kidneys, and pancreas [10] [12]. This exceeds the tissue's oxidative capacity, resulting in lipotoxicity—a process characterized by the accumulation of harmful lipid intermediates like diacylglycerol (DG) and ceramides, which induce cellular stress, inflammation, and impair insulin signaling [10] [12].

Comparative Analysis of Ectopic Lipid Deposition in Target Organs

The pathophysiology of ectopic lipid deposition exhibits distinct features across different target organs, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Organ-Specific Characteristics of Ectopic Lipid Deposition and LD Dynamics

| Target Organ | Key LD-Associated Proteins | Primary Pathophysiological Consequences | Major Diabetic Complication(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | PLIN2, PLIN5 [12] [13] | Disrupted LD-regulated lipolysis and β-oxidation; hepatic insulin resistance; progression to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [10] [12] | Hepatic Steatosis, MASLD [12] |

| Skeletal Muscle | PLIN2, PLIN5 [12] [13] | Intramyocellular lipid accumulation; impaired insulin-mediated glucose uptake; systemic insulin resistance [10] [12] | Insulin Resistance, Sarcopenia (indirectly) |

| Pancreas (β-cells) | PLINs (unspecified) [10] | Impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; β-cell apoptosis via ER stress and oxidative stress [10] | β-cell Failure, Worsening Hyperglycemia |

| Heart | PLIN5 [10] [12] | Cardiac lipotoxicity; mitochondrial dysfunction; impaired contractility [10] | Diabetic Cardiomyopathy [10] |

| Kidney | Information not specified in search results | Information not specified in search results | Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) [10] [6] |

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The regulation of LD dynamics and the progression to lipotoxicity involve complex inter-organellar communication and several key signaling pathways. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways and pathological consequences associated with dysregulated LD dynamics in a metabolically stressed cell, such as a hepatocyte or myocyte.

A critical component of the pathway above is the interaction between lipid droplets and other organelles. The Perilipin (PLIN) family of proteins, particularly PLIN2 and PLIN5, are central gatekeepers of LD functions. Their tissue-specific roles and regulatory mechanisms are detailed in the following table.

Table 2: Key Functions of Select Perilipin (PLIN) Family Proteins in Lipid Metabolism

| Protein | Primary Tissue Expression | Core Functions in LD Dynamics | Regulatory Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLIN1 | White & Brown Adipose Tissue [12] | Major regulator of lipolysis; coats LD surface to isolate lipases at rest; phosphorylated by PKA to activate lipolysis during fasting/exercise [12]. | PKA-mediated phosphorylation [12]. |

| PLIN2 | Ubiquitous (Liver, Muscle, etc.) [12] | Promotes lipid storage & LD stability; inhibits lipolysis; also regulates LD-mediated lipophagy [12]. | Degraded via chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) during nutrient restriction [12]. |

| PLIN5 | Tissues with high aerobic metabolism (Heart, Muscle, Liver) [10] [12] | Regulates LD-mitochondria contact; suppresses lipolysis at rest; facilitates FA channeling to mitochondria for oxidation during energy demand [10] [12]. | PKA-mediated phosphorylation releases co-repressors, promoting lipolysis [12]. |

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Investigation

In Vivo Modeling of Ectopic Lipid Deposition

A common and robust method for inducing ectopic lipid deposition and studying insulin resistance is the diet-induced obesity (DIO) mouse model.

- Animal Model: C57BL/6J mice [13].

- Dietary Regimen: Mice are fed a high-fat diet (HFD), typically for 12-16 weeks, to induce obesity and metabolic dysfunction [13]. This model allows for the stratification of mice into diet-induced obese (DIO) and diet-induced obesity-resistant (DIO-R) phenotypes based on weight gain and the Lee index, enabling comparative studies [13].

- Key Readouts:

- Tissue Analysis: Histological examination of organs (e.g., liver, skeletal muscle) via Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Oil Red O staining to visualize lipid accumulation and steatosis [13].

- Systemic Metrics: Monitoring of body weight, fasting blood glucose, and insulin levels to assess glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity [13].

In Vitro Modeling of Lipid Droplet Accumulation

Cultured cell lines exposed to free fatty acids (FFAs) are widely used to study the molecular mechanisms of LD dynamics and lipotoxicity.

- Cell Lines: HepG2 (liver) and C2C12 (skeletal muscle, requiring differentiation into myotubes) [13].

- Lipid Loading Protocol: Cells are treated with a mixture of fatty acids (e.g., 1 mM palmitic and oleic acid at a 1:2 ratio) complexed with fatty acid-free Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) for 24 hours to induce LD formation [13].

- Genetic Manipulation: Transfection with siRNA (e.g., targeting FGF-21) to investigate the functional role of specific genes in LD regulation [13].

- Downstream Analysis:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Key Reagents and Models for Studying LD Dynamics and Ectopic Deposition

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| C57BL/6J Mice | In Vivo Model | Gold-standard model for studying diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and organ-specific ectopic lipid deposition [13]. | Comparing DIO vs. DIO-R phenotypes to identify protective metabolic mechanisms [13]. |

| HepG2 & C2C12 Cells | In Vitro Model | Human liver and mouse skeletal muscle cell lines, respectively, for mechanistic studies of lipid metabolism and lipotoxicity [13]. | Investigating the impact of gene knockdown (e.g., FGF-21) on FFA-induced LD accumulation [13]. |

| Palmitic/Oleic Acid-BSA Conjugate | Metabolic Inducer | Mimics lipid overload in vitro; BSA conjugation facilitates FFA delivery to cells, inducing LD biogenesis and lipotoxicity [13]. | Standard protocol for creating cellular models of steatosis and insulin resistance [13]. |

| siRNA / shRNA | Genetic Tool | Silences specific gene expression to determine functional roles in LD dynamics (e.g., FGF-21, PLINs) [13]. | Elucidating gene function in regulated lipolysis, LD formation, and mitochondrial FA oxidation [13]. |

| Antibodies (PLIN2, PLIN5, FGF-21) | Analytical Reagent | Detects protein expression and localization via Western blot, immunofluorescence, and immunohistochemistry. | Quantifying tissue-specific PLIN expression changes under different metabolic states (e.g., fasting, exercise) [12]. |

| Oil Red O Stain | Histological/Cytological Dye | Stains neutral lipids (triglycerides, cholesteryl esters) in tissues and cells, allowing quantification of LD content [13]. | Visualizing and quantifying intramyocellular or intrahepatic lipid deposition in tissue sections or cultured cells [13]. |

Emerging Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Beyond cellular proteins, novel lipid-based biomarkers are emerging for risk assessment in clinical and research settings.

- Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP): Calculated as log10(TG/HDL-C). It is a significant predictor of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) risk, with higher values indicating greater atherogenic potential and association with microvascular complications [14] [6].

- Triglyceride-Glucose Index (TyG): Calculated as ln[TG (mg/dL) × FPG (mg/dL)/2]. It is a reliable surrogate marker for insulin resistance and demonstrates superior predictive performance for T2D risk, even in individuals with a history of dyslipidemia [14].

Therapeutic strategies are increasingly focusing on restoring LD dynamics. These include lifestyle interventions like exercise, which modulates PLIN expression and promotes healthy LD turnover [12], and pharmacological agents that target specific nodes in the pathways, such as the cAMP/PKA signaling axis or directly enhancing mitochondrial function and MQC to alleviate lipotoxicity [10] [15].

Distinct Lipid Biomarker Profiles for Kidney Disease, Retinopathy, and Neuropathy

Lipid metabolism is increasingly recognized as a central player in the pathogenesis of diabetic microvascular complications. While diabetic kidney disease (DKD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), and diabetic neuropathy (DN) share hyperglycemia as a common underlying risk factor, emerging evidence reveals that distinct lipid biomarker profiles are associated with each complication. This divergence offers critical insights for developing targeted diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Understanding these unique lipid signatures is essential for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to move beyond generic metabolic markers toward precision medicine approaches. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the specific lipid biomarkers, experimental methodologies, and pathophysiological mechanisms underlying these complications, synthesizing the most recent research findings to inform future investigation and therapeutic development.

Comparative Lipid Biomarker Profiles

The table below summarizes the distinct lipid biomarkers associated with each diabetic complication, highlighting their specific roles and research implications.

Table 1: Distinct Lipid Biomarker Profiles by Diabetic Complication

| Complication | Specific Lipid Biomarkers | Biological Sample | Associated Risk/Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney Disease (DKD) | • 21 specific lipids in urinary small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) [16]• Ceramides, Diacylglycerols [17]• Elevated LAP, AIP, VAI indices [6] | Urine, Blood [16] [6] [17] | Direct mediators of renal cell injury (lipotoxicity); predicts rapid eGFR decline [17]. |

| Retinopathy (DR) | • Specific lipidomes (e.g., Triacylglycerol) [18]• Glycolipids in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [19] | Blood, Retinal tissue [18] [19] | Causal relationship with DR onset/progression; altered metabolism drives RPE cell migration [18] [19]. |

| Neuropathy (DN) | • Lipid metabolism alterations in Schwann cells [20]• Perturbations in lipid rafts and signaling [20] | Peripheral nerve tissue [20] | Disruption of myelin integrity and axonal function; central to cellular dysfunction [20]. |

| General Complications | Lipid Droplet (LD) Dynamics [3] | Multiple organs (e.g., pancreas, kidney, retina) [3] | Ectopic lipid deposition and lipotoxicity exacerbate complications in target organs [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Lipid Biomarker Analysis

Urinary sEV Lipidomics for Kidney Disease

Application: This protocol is designed for the discovery of lipid biomarkers in chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) and diabetic kidney disease (DKD) [16] [17].

Workflow:

- Sample Collection: Collect 15-20 mL of urine. For longitudinal studies, collect fasting spot urine at baseline and follow up for multiple years to track kidney function decline [16] [17].

- sEV Purification:

- Centrifuge urine at 1,000× g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove particulates and cells [16].

- Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm PES filter [16].

- Perform ultracentrifugation of the filtered urine at 250,000× g for 2 hours at 4°C to pellet sEVs [16].

- Wash the pellet with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and repeat ultracentrifugation [16].

- Resuspend the final sEV pellet in 200 µL of PBS [16].

- sEV Characterization:

- Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA): Use an instrument (e.g., NanoSight NS300) to quantify the concentration and size distribution of sEVs by analyzing Brownian motion [16].

- Bead-Based Multiplex Flow Cytometry: Use a kit (e.g., MACSPlex Human EV Kit) to characterize surface protein profiles (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81) to confirm sEV origin and identify tissue-specific markers [16].

- Lipidomics Analysis:

- Data Analysis:

- Use univariate statistical analysis to identify differentially expressed lipids with a threshold of |log2 fold change| ≥1.5 and p < 0.05 [17].

- Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest, Boruta) for feature selection to identify the most promising biomarker candidates from the lipid data [17].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for urinary sEV lipidomics in kidney disease research.

Mendelian Randomization for Retinopathy Lipidomics

Application: This method is used to establish a causal relationship between specific lipidomes and diabetic retinopathy (DR), overcoming limitations of observational studies [18].

Workflow:

- Data Sourcing: Obtain summary-level data from large-scale genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for both the exposure (lipidomes) and the outcome (DR and its subtypes) from public repositories like the GWAS catalogue and biobanks (e.g., FinnGen) [18].

- Lipidome Profiling: Utilize high-resolution lipidomic techniques, such as shotgun lipidomics, to generate comprehensive lipidome data for the genetic analysis [18].

- Bidirectional MR Analysis:

- Select genetic variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) that are strongly associated with the specific lipidomes as instrumental variables [18].

- Perform a two-sample MR to estimate the causal effect of lipidomes on DR [18].

- Conduct a reverse-direction MR to test for causality from DR back to lipidomes, establishing the direction of the relationship [18].

- Mediation Analysis: Investigate whether circulating inflammatory proteins (e.g., interleukin-10) mediate the causal effect of protective lipids on DR. Calculate the mediation proportion to quantify this indirect effect [18].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a battery of sensitivity tests (e.g., MR-Egger, MR-PRESSO) to validate the reliability of the findings and ensure they are not biased by pleiotropy [18].

Investigating Lipid Dynamics in Neuropathy

Application: This approach focuses on understanding the role of lipid metabolism alterations in peripheral neurons and Schwann cells in diabetic neuropathy [20].

Workflow:

- Model Systems: Use both inherited (e.g., Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease models) and acquired peripheral neuropathy models to study lipid-centric mechanisms [20].

- Focus Areas:

- Lipid Rafts: Investigate the role of lipid rafts—specialized membrane microdomains—in Schwann cell signaling and myelin integrity [20].

- Lipid Storage and Signaling: Analyze changes in lipid storage and the function of lipids as signaling molecules in peripheral neurons [20].

- Genetic and Environmental Links: Explore how genetic mutations and environmental factors known to cause neuropathy converge on pathways affecting lipid metabolism in peripheral nerves [20].

- Techniques: A combination of omics technologies (lipidomics, transcriptomics), histological analysis, and functional nerve conduction studies are typically employed to correlate lipid changes with cellular dysfunction and clinical phenotypes [20].

Pathophysiological Pathways and Mechanisms

The pathophysiological pathways linking lipid metabolism to each complication are distinct, yet interconnected through the overarching theme of lipotoxicity.

Figure 2: Distinct pathological mechanisms of lipid dysregulation in microvascular complications.

Kidney Disease Pathogenesis: Lipids contribute to DKD primarily through lipotoxicity. Specific lipid species like ceramides and diacylglycerols act as direct mediators of renal cell injury [17]. Urinary sEVs serve as vehicles for lipid trafficking and signaling, and their lipid content is significantly altered in early CKD. These sEVs also express surface proteins indicative of early inflammation, suggesting a combined lipid and inflammatory insult in the kidneys [16]. Furthermore, calculated indices like LAP, AIP, and VAI, which reflect visceral adiposity and atherogenic dyslipidemia, are significantly elevated in patients with DKD, providing a link between systemic lipid metabolism and renal damage [6].

Retinopathy Pathogenesis: In AMD and DR, lipid dysregulation manifests prominently in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Research using imaging mass spectrometry has shown that migrating RPE cells undergo a change in lipid metabolism, particularly involving glycolipids [19]. This altered metabolism drives a process of transdifferentiation, where RPE cells change their identity, migrate, and form hyperreflective foci—a known biomarker for disease progression [19]. Furthermore, MR studies have established a causal relationship between specific lipidomes and DR, with inflammatory factors like interleukin-10 acting as key mediators in the protective mechanisms of certain lipids [18].

Neuropathy Pathogenesis: The integrity of the myelin sheath—a lipid-rich structure—is critical for axonal function in the peripheral nervous system. Alterations in lipid metabolism in Schwann cells and neurons disrupt this integrity [20]. The mechanisms involve perturbations in lipid rafts (signaling platforms), impaired lipid storage, and dysregulated lipid signaling. These changes, whether from genetic or acquired causes, are central to cellular dysfunction in peripheral neuropathies, making lipid balance a key therapeutic target [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and technologies used in the featured lipid biomarker research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Lipid Biomarker Studies

| Reagent / Technology | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ultracentrifugation | Isolation and purification of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) from biofluids. | Pelleting sEVs from urine for subsequent lipid profiling [16]. |

| MACSPlex Human EV Kit | Bead-based multiplex flow cytometry for characterizing sEV surface markers. | Detecting CD9, CD63, CD81 and kidney-specific markers on urinary sEVs [16]. |

| NanoSight NS300 (NTA) | Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis to quantify the size and concentration of vesicles. | Determining the concentration and size distribution of isolated sEVs [16]. |

| UPLC/TQMS | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry for targeted lipid quantification. | Precise identification and quantification of hundreds of lipid species in urine or tissue [17]. |

| Imaging Mass Spectrometry (IMS) | Spatial mapping of molecular distributions directly in tissue sections at near single-cell resolution. | Identifying the specific glycolipid composition of migrating RPE cells in the retina [19]. |

| Shotgun Lipidomics | A high-resolution, comprehensive approach to profile the entire lipidome of a sample. | Generating lipidome data for causal inference studies in retinopathy [18]. |

| GWAS Summary Data | Publicly available genetic data used for Mendelian Randomization analysis. | Sourcing instrumental variables for lipids and diabetic retinopathy from biobanks [18]. |

The landscape of lipid biomarkers in diabetic microvascular complications is characterized by both disease-specific profiles and shared pathophysiological themes like lipotoxicity. Kidney disease research is advancing with non-invasive urinary sEV lipidomics, retinopathy studies are leveraging causal genetic tools like Mendelian Randomization, and neuropathy investigations are focusing on lipid-centric mechanisms in Schwann cells and myelin. These distinct approaches underscore the necessity of precision medicine. For researchers and drug developers, this means that therapeutic strategies targeting lipids will likely need to be complication-specific. Future research should focus on integrating these multi-omics biomarkers with artificial intelligence to improve early detection, risk stratification, and the development of targeted lipid-modulating therapies.

In the evolving landscape of metabolic disease research, the identification of reliable biomarkers for predicting complication risk in diabetes mellitus remains a critical scientific challenge. Traditional lipid profiles and anthropometric measurements often fail to capture the complex interplay between visceral adiposity, dyslipidemia, and microvascular pathology. Within this context, novel composite indices—specifically the Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI), Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP), and Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP)—have emerged as integrated measures that may offer superior predictive capability for diabetic complications. These calculated indices synthesize routine clinical measurements into powerful risk assessment tools that reflect underlying pathophysiological processes, including visceral adipose tissue dysfunction, systemic insulin resistance, and atherogenic lipid patterning. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these three indices' predictive performance across multiple diabetic complications, supported by experimental data and mechanistic insights to guide researchers and drug development professionals in their translational applications.

Comparative Analysis of Predictive Performance

Diagnostic Accuracy for Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD)

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis comprising 23 studies demonstrated that all three indices significantly predict diabetic kidney disease risk in diabetic populations [6]. The analysis revealed markedly elevated biomarker levels in patients with DKD compared to those without nephropathy.

Table 1: Biomarker Levels in DKD vs. Non-DKD Patients

| Biomarker | Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAP | 12.67 | 7.83 to 17.51 | < 0.01 |

| AIP | 0.11 | 0.03 to 0.19 | < 0.01 |

| VAI | 0.63 | 0.38 to 0.89 | < 0.01 |

For each unit increase in these indices, the associated risk of developing DKD rose significantly, with AIP showing the strongest association per unit change [6].

Table 2: Odds Ratios for DKD Risk per 1-Unit Increase

| Biomarker | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAP | 1.005 | 1.003 to 1.006 | < 0.01 |

| AIP | 1.08 | 1.04 to 1.12 | < 0.01 |

| VAI | 1.05 | 1.03 to 1.07 | < 0.01 |

Predictive Value for Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

Research findings regarding diabetic retinopathy show conflicting results. While the comprehensive meta-analysis found no significant associations between these biomarkers and DR [6], a large cross-sectional study using NHANES 2005-2008 data (n=2,591) demonstrated positive associations after full covariate adjustment [21] [22].

Table 3: Association Between Indices and Diabetic Retinopathy

| Biomarker | Odds Ratio (OR) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAP | 1.004 | 1.002 to 1.006 | < 0.0001 |

| VAI | 1.090 | 1.037 to 1.146 | 0.0007 |

| AIP | 1.802 | 1.240 to 2.618 | 0.0020 |

This discrepancy highlights the need for further prospective studies but suggests these indices may have value in DR risk stratification, particularly in specific populations.

Cardiovascular Disease Prediction

Beyond microvascular complications, these indices demonstrate significant predictive capacity for cardiovascular diseases. A 6-year prospective study of 9,704 individuals found AIP, LAP, and VAI significantly associated with CVD incidence after adjusting for confounding factors [23]. The decision tree analysis identified AIP ≥ 0.94 as a critical threshold for CVD risk in men, while VAI remained significant in multivariate models for women [23].

Type 2 Diabetes Incidence Prediction

In a large Japanese cohort study (n=195,989), all three indices strongly predicted new-onset T2DM over a mean follow-up of 4.61 years [24]. The areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) for AIP, LAP, and VAI ranged between 0.821 and 0.844, indicating excellent predictive capability [24].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Calculation Formulas

The indices are calculated using standardized formulas incorporating routine clinical and laboratory measurements:

Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP)

- Males: LAP = [WC (cm) - 65] × TG (mmol/L)

- Females: LAP = [WC (cm) - 58] × TG (mmol/L)

Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI)

- Males: VAI = (WC/39.68 + BMI/1.88) × (TG/1.03) × (1.31/HDL-C)

- Females: VAI = (WC/36.58 + BMI/1.89) × (TG/0.81) × (1.52/HDL-C)

Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP)

Key Population Studies

The evidence base for these indices derives from several methodological approaches:

- Systematic Reviews/Meta-Analyses: The foundational evidence comes from a comprehensive analysis of 23 studies following PRISMA guidelines, synthesizing data across multiple research designs and populations [6] [25].

- Large Prospective Cohorts: Studies like the Fukushima Health Database (n=195,989) and MASHAD study (n=9,704) provide longitudinal data on disease incidence with multivariable adjustment for confounders [23] [24].

- Cross-Sectional Population Studies: NHANES analyses provide generalizable population-level estimates of association between indices and complications [21] [22].

- Multivariable Regression Models: Studies typically employ multiple adjusted models, progressively controlling for demographic, clinical, and metabolic confounders to isolate independent effects [21].

Research Methodology Workflow

Pathophysiological Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The predictive capacity of these indices stems from their reflection of underlying pathological processes linking dyslipidemia, visceral adiposity, and complication risk.

Lipid Droplet Dynamics and Visceral Adipose Tissue Dysfunction

Visceral adipose tissue exhibits distinct pathological behavior in diabetes, with enhanced lipolytic activity and increased inflammatory cell infiltration compared to subcutaneous fat [6]. VAI specifically captures this dysfunction by integrating measures of visceral fat distribution with lipid parameters. Under insulin-resistant conditions, lipid droplet dynamics become impaired, leading to ectopic lipid accumulation in tissues vulnerable to diabetic complications, including kidneys, retina, and vascular endothelium [3].

Excessive lipid accumulation beyond compensatory capacity initiates lipotoxicity through several mechanisms:

- Elevated free fatty acids induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial dysfunction [3]

- Altered perilipin protein expression disrupts lipid mobilization [3]

- Impaired lipophagy reduces lipid turnover and promotes cytotoxic lipid intermediate accumulation [3]

Pathophysiological Pathways to Complications

Atherogenic Dyslipidemia and Insulin Resistance

AIP captures the atherogenic lipid pattern characterized by elevated triglycerides and low HDL-C that frequently accompanies insulin resistance [6] [21]. This lipid profile promotes vascular dysfunction through multiple mechanisms:

- Increased triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants penetrate the vascular wall, initiating atherosclerotic plaque formation [23]

- HDL dysfunction impairs reverse cholesterol transport and reduces vasoprotective effects [23]

- Altered lipoprotein composition enhances oxidation and glycation, increasing immunogenicity and inflammatory responses [26]

LAP integrates both anthropometric and lipid parameters to reflect the interplay between abdominal obesity and dyslipidemia in driving complication risk [24] [21]. The strong correlation between LAP and diabetic kidney disease suggests this index captures pathways relevant to renal pathology, potentially through lipid-induced podocyte injury, tubular damage, and glomerular sclerosis [6] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Investigating VAI, LAP, and AIP

| Reagent/Instrument | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Colorimetric Assays | Quantitative measurement of TG and HDL-C | Core lipid parameter quantification for index calculation |

| Standardized Anthropometric Tools | Precise measurement of waist circumference | Critical for LAP and VAI computation with minimal measurement error |

| Automated Clinical Chemistry Analyzers | High-throughput lipid profiling | Large cohort studies requiring standardized measurements across participants |

| ELISA Kits for Adipokines | Quantification of leptin, adiponectin | Validation of visceral adipose dysfunction correlates |

| Lipoprotein Fractionation Systems | Separation and analysis of lipoprotein subclasses | Mechanistic studies linking AIP to atherogenic particle distribution |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry | Comprehensive lipidomic profiling | Advanced investigation of lipid species underlying index associations |

The comprehensive comparison of VAI, LAP, and AIP reveals distinct patterns of predictive capacity across diabetic complications. While all three indices demonstrate significant associations with diabetic kidney disease and cardiovascular outcomes, their performance varies by complication type and population. AIP shows particularly strong associations with both microvascular and macrovascular complications, potentially reflecting its capture of atherogenic lipid patterning. LAP excels in abdominal obesity-related risk stratification, while VAI specifically addresses visceral adipose tissue dysfunction. Despite promising diagnostic characteristics, current evidence indicates these indices offer complementary rather than redundant information, suggesting potential utility in multi-marker prediction panels. For drug development professionals, these indices provide valuable intermediate endpoints for clinical trials targeting metabolic pathways in diabetes complications. Future research should focus on standardizing cut-off values across populations, validating these indices in diverse ethnic groups, and exploring their utility in guiding targeted therapeutic interventions.

Lipotoxicity refers to the process by which excess lipids accumulate in non-adipose tissues, leading to cellular dysfunction and cell death. The term was first coined in 1994 when researchers observed that lipid overload in pancreatic β-cells led to loss of function and the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus in rats [27] [28]. Since this seminal discovery, research has revealed that lipotoxicity represents a fundamental pathological mechanism connecting obesity to metabolic disease, affecting multiple organs including the pancreas, liver, skeletal muscles, heart, and kidneys [27] [29]. While initial research focused on general lipid accumulation, recent advances have identified specific lipid metabolites—Free Fatty Acids (FFAs), Diacylglycerol (DAG), and ceramides—as the primary molecular mediators of lipotoxic damage [29] [30]. These bioactive lipids disrupt cellular signaling pathways, promote inflammation, induce oxidative stress, and ultimately contribute to insulin resistance and diabetic complications [31] [30]. This review systematically compares the distinct and overlapping mechanisms through which FFAs, DAG, and ceramides drive cellular dysfunction, providing a comprehensive analysis of their roles as key pathological agents in metabolic disease.

Comparative Pathophysiology of Key Lipotoxic Mediators

Free Fatty Acids (FFAs): Initiators of Lipotoxic Stress

Free Fatty Acids, particularly saturated fatty acids like palmitic acid, serve as fundamental precursors to lipotoxic damage. When FFA delivery exceeds the metabolic capacity of non-adipose tissues, they initiate a cascade of cellular stress responses [29]. The mechanisms of FFA-induced lipotoxicity include:

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation: Elevated FFA levels stimulate ROS production through protein kinase C-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase in vascular cells and through mitochondrial electron transport chain inefficiencies [28] [30]. This oxidative stress damages cellular components including lipids, proteins, and DNA.

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress: Chronic lipid overload disrupts ER function, engaging the unfolded protein response which, when prolonged, transitions from adaptive to pro-apoptotic signaling [28] [29].

Inflammatory Pathway Activation: FFAs activate toll-like receptors (particularly TLR4) and the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [29] [30].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Excessive FFAs overwhelm mitochondrial β-oxidation capacity, leading to incomplete fatty acid oxidation and accumulation of toxic lipid intermediates [29] [30]. This is particularly detrimental in pancreatic β-cells, where mitochondrial function is crucial for glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

Interestingly, not all FFAs exert equally detrimental effects. Saturated fatty acids (e.g., palmitate) are strongly lipotoxic, while monounsaturated fatty acids (e.g., oleate) can actually protect against lipotoxic stress by promoting triglyceride storage in lipid droplets and reducing ceramide synthesis [29].

Diacylglycerol (DAG): The Insulin Signaling Disruptor

Diacylglycerol accumulates as an intermediate in lipid metabolism and functions as a potent signaling molecule that directly impairs insulin action through:

Protein Kinase C (PKC) Activation: DAG activates several PKC isoforms, predominantly the novel (δ, ε, θ) and conventional (βII) forms. PKCθ activation in skeletal muscle and PKCε activation in the liver phosphorylate insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins on inhibitory serine residues, impairing insulin signal transduction [30].

Disruption of Insulin Receptor Signaling: By activating PKC, DAG interferes with the tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1, reducing its ability to activate downstream effectors in the PI3K/Akt pathway [31]. This ultimately impairs GLUT4 translocation to the cell membrane and reduces glucose uptake.

Tissue-Specific Effects: DAG accumulation in the liver promotes hepatic insulin resistance and increases gluconeogenesis, while in skeletal muscle it reduces glucose disposal capacity [30]. The subcellular localization of DAG pools is critical, with plasma membrane-associated DAG exhibiting the greatest impact on insulin signaling.

The table below summarizes the distinct mechanisms through which DAG species contribute to insulin resistance across different tissues:

Table 1: Tissue-Specific Mechanisms of DAG-Induced Insulin Resistance

| Tissue | Primary DAG Species | PKC Isoform Activated | Downstream Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal Muscle | C18:0, C18:1 | PKCθ | Reduced IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation; Impaired GLUT4 translocation |

| Liver | C16:0, C18:0 | PKCε | Increased gluconeogenic gene expression; Reduced glycogen synthesis |

| Heart | C16:0, C18:1 | PKCβII | Reduced glucose oxidation; Preferential fatty acid utilization |

Ceramides: The Apoptotic and Inflammatory Mediators

Ceramides, a class of sphingolipids, have emerged as particularly potent lipotoxic agents with dual roles in promoting insulin resistance and cellular apoptosis. Ceramide synthesis occurs through three major pathways: de novo synthesis, sphingomyelin hydrolysis, and the salvage pathway [27] [31]. Their mechanisms of action include:

Direct Inhibition of Insulin Signaling: Ceramides inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway through multiple mechanisms, including activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) which dephosphorylates Akt, and promotion of Akt ubiquitination and degradation [27] [31]. Specific ceramide species (particularly C16 and C18) exhibit the strongest associations with insulin resistance [32].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Ceramides accumulate in mitochondrial membranes where they inhibit electron transport chain complexes (particularly III and IV), increase reactive oxygen species production, and enhance mitochondrial membrane permeability, promoting cytochrome c release and apoptosis [27] [33].

Inflammatory Signaling: Ceramides activate NF-κB signaling and promote the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [27]. They also form lipid rafts that facilitate inflammatory receptor clustering and signaling.

β-Cell Apoptosis: In pancreatic β-cells, ceramides induce apoptosis through both extrinsic (death receptor) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) pathways, contributing to the progressive β-cell loss observed in type 2 diabetes [31].

The six ceramide synthase isoforms (CerS1-6) produce ceramide species with different fatty acyl chain lengths, each with distinct biological functions and tissue distributions [27]. For example, CerS1 generates C18-ceramide predominantly in muscle tissue, while CerS6 produces C16-ceramide in adipose tissue [27]. This specificity has important implications for tissue-specific lipotoxicity and presents potential therapeutic targets.

Table 2: Ceramide Synthase Isoforms and Their Roles in Metabolic Disease

| Ceramide Synthase | Primary Ceramide Species | Tissue Expression | Metabolic Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CerS1 | C18:0 | Skeletal muscle, brain | Regulates insulin sensitivity in muscle; Promotes neuronal survival |

| CerS2 | C22:0, C24:0 | Liver, kidney | Maintains normal hepatic and renal function; Elevated in NAFLD |

| CerS3 | Ultra-long chain | Skin, testis | Primarily structural role in skin barrier |

| CerS4 | C20:0, C22:0 | Skin, liver, leukocytes | Limited role in metabolic disease |

| CerS5 | C16:0 | Ubiquitous | Promotes hepatic insulin resistance; Associated with CVD risk |

| CerS6 | C16:0 | Adipose tissue, ubiquitous | Adipose tissue inflammation; Systemic insulin resistance |

Integrated Signaling Pathways in Lipotoxicity

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways through which FFAs, DAG, and ceramides induce cellular dysfunction and inflammation:

Lipotoxicity Signaling Network. This diagram illustrates the convergent and distinct pathways through which FFAs, DAG, and ceramides promote insulin resistance and cellular dysfunction. Yellow nodes represent FFA-mediated pathways, red indicates DAG-specific mechanisms, blue shows ceramide actions, and green denotes common downstream effects.

Experimental Models and Methodologies for Lipotoxicity Research

In Vitro Models and Treatment Protocols

Cell Culture Systems: Primary hepatocytes, skeletal myocytes (C2C12), pancreatic β-cell lines (MIN6, INS-1), and cardiomyocytes are commonly used. Treatment with pathophysiological concentrations of palmitate (0.25-0.75 mM) for 6-24 hours reliably induces lipotoxicity [31] [29]. BSA-conjugated palmitate preparations ensure proper solubility and delivery.

Lipotoxicity Assessment: Key endpoints include insulin signaling (IRS-1 tyrosine phosphorylation, Akt phosphorylation), glucose uptake assays, mitochondrial function (Seahorse analyzer), apoptosis markers (caspase-3 activation, TUNEL staining), and inflammatory cytokine secretion (ELISA) [31] [29].

In Vivo Models and Dietary Interventions

Genetic Models: db/db mice (leptin receptor deficiency), ob/ob mice (leptin deficiency), and Zucker diabetic fatty rats represent gold standard models that develop severe obesity and diabetes with characteristic tissue lipid accumulation [28] [34].

Dietary Models: High-fat diets (45-60% kcal from fat) administered for 8-24 weeks induce obesity, insulin resistance, and tissue lipid accumulation in C57BL/6J mice and other strains [33].

Intervention Studies: Alternate-day fasting protocols (24-hour fast followed by 24-hour ad libitum feeding) for extended durations (e.g., 6 months in db/db mice) effectively reduce hepatic ceramides and improve metabolic parameters without weight loss [34].

The table below summarizes key experimental approaches for studying lipotoxic metabolites:

Table 3: Experimental Models for Investigating Lipotoxic Metabolites

| Research Goal | Preferred Model | Key Readouts | Experimental Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFA-induced IR | Primary hepatocytes; H4IIEC3 hepatoma cells | PKCε translocation; Akt phosphorylation; Glucose output | 6-24 hours |

| DAG signaling | Skeletal muscle strips; L6 myotubes | Membrane DAG content; PKCθ activation; 2-deoxyglucose uptake | 2-6 hours |

| Ceramide effects | Pancreatic β-cell lines; C2C12 myotubes | Ceramide species (LC-MS/MS); PP2A activity; Apoptosis markers | 12-48 hours |

| Whole-body metabolism | HFD-fed C57BL/6J mice; db/db mice | Glucose tolerance; Tissue lipidomics; Insulin signaling | 8-24 weeks |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Lipotoxicity Studies

| Reagent/Method | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Palmitate-BSA conjugates | Induction of lipotoxicity in vitro | Physiological relevance; Controllable concentrations |

| Myriocin | Ceramide synthesis inhibition | Specific inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT) |

| Fumonisin B1 | Ceramide synthase inhibition | Broad-spectrum CerS inhibitor |

| LC-MS/MS lipidomics | Comprehensive lipid analysis | Quantitative measurement of lipid species; High sensitivity |

| Seahorse Analyzer | Mitochondrial function assessment | Real-time OCR and ECAR measurements |

| C16-ceramide antibodies | Ceramide detection | Immunohistochemistry and Western blot applications |

| AdipoRon | Adiponectin receptor agonist | Activates AdipoR1/2 ceramidase activity |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

The understanding of lipotoxicity mechanisms has opened several promising therapeutic avenues:

Ceramide-Lowering Approaches: Pharmacological inhibition of ceramide synthesis with myriocin or fumonisin B1 improves insulin sensitivity and reduces atherosclerosis in animal models [27] [33]. Adiponectin receptor agonists that activate receptor ceramidase activity represent another promising strategy [33].

Lifestyle Interventions: Alternate-day fasting and time-restricted feeding protocols significantly reduce ceramide levels and improve glucose homeostasis, even in the absence of weight loss [34]. These interventions enhance mitochondrial function and promote beneficial shifts in lipid metabolism.

Precision Targeting: Isoform-specific ceramide synthase inhibitors (e.g., targeting CerS6 for C16-ceramide production) may provide therapeutic benefits with reduced side effects [27] [32]. Similarly, tissue-specific approaches to modulate DAG-sensitive PKC isoforms offer potential for targeted intervention.

Future research should focus on delineating the specific roles of different ceramide species in disease pathogenesis, developing more precise pharmacological tools to modulate specific lipotoxic pathways, and conducting human trials to validate interventions that successfully target these mechanisms in clinical populations.

Advanced Analytical Techniques for Lipidomic Profiling and Biomarker Discovery

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) technologies have become foundational tools in modern life sciences research, particularly in the field of metabolomics and lipidomics for studying complex diseases such as diabetes and its complications [35]. Among these platforms, Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) and Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS) represent two sophisticated approaches with complementary strengths and applications [36] [37]. The selection between these platforms involves careful consideration of resolution, sensitivity, throughput, and analytical goals, especially when investigating subtle metabolic alterations in diabetic progression [38] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their performance characteristics and applications in lipid metabolite research for diabetic complications.

Technical Fundamentals and Comparison

Core Principles and Instrumentation

UHPLC-MS/MS typically employs triple quadrupole (QqQ) or similar tandem mass analyzers operating at unit mass resolution. This platform excels in targeted analyses using techniques like Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM), where specific precursor-to-product ion transitions are monitored for precise quantification [37]. The UHPLC component provides superior chromatographic separation with sub-2μm particles, resulting in higher peak capacity, improved resolution, and reduced analysis times compared to conventional HPLC [37].

LC-HRMS utilizes mass analyzers such as Time-of-Flight (TOF) or Orbitrap technologies capable of resolution ≥20,000 full width at half maximum (FWHM) [39]. This enables exact mass measurement with accuracy typically <5 ppm, allowing determination of elemental compositions and discrimination of isobaric compounds [40] [39]. Common configurations include Q-TOF and Q-Orbitrap hybrid systems that combine MS and MS/MS capabilities [35].

Performance Characteristics Comparison

Table 1: Direct Comparison of UHPLC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | UHPLC-MS/MS | LC-HRMS |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Resolution | Unit mass resolution (±1 Da) [39] | High resolution (≥20,000 FWHM) with mass accuracy <5 ppm [39] |

| Primary Strength | High sensitivity for targeted quantification [37] | Untargeted screening and retrospective analysis [37] |

| Selectivity | Relies on retention time and MRM transitions; may yield false positives for isobaric compounds [40] | High selectivity via exact mass measurement; can resolve isobaric interferences [40] [39] |

| Data Acquisition | Targeted (MRM) or limited multi-analyte methods [36] | Full-scan data with data-dependent or data-independent MS/MS [36] |

| Dynamic Range | Typically wider dynamic range [39] | Historically narrower, though improving with recent instruments [39] |

| Throughput | Excellent for routine targeted analysis [37] | Suitable for untargeted screening; data processing can be more time-intensive [37] |

| Ideal Application | Quantitative analysis of known metabolites [37] | Discovery research, unknown identification, retrospective analysis [37] |

Experimental Evidence for Selectivity Differences

A comprehensive comparison study demonstrated the superior selectivity of LC-HRMS (at 50,000 FWHM) over LC-MS/MS in analyzing complex biological samples [40]. Researchers monitored dummy exact masses and transitions in blank matrix extracts (fish, pork kidney, pork liver, honey) and found LC-HRMS provided higher selectivity at corresponding mass windows [40].

The practical implication was demonstrated in honey analysis, where LC-MS/MS produced a false positive for a banned nitroimidazole drug due to an interfering matrix compound with identical retention time and MRM transitions [40]. LC-HRMS clearly resolved the interference, unmasking the false finding [40]. This demonstrates the critical advantage of high-resolution platforms in regulatory and research contexts where result confidence is paramount.

Applications in Diabetic Complications Research

Lipidomics in Diabetes and Hyperuricemia

UHPLC-MS/MS has been effectively employed to investigate lipid metabolic disorders in diabetes mellitus combined with hyperuricemia (DH) [41]. An untargeted lipidomic analysis using UHPLC-MS/MS revealed significant alterations in 1,361 identified lipid molecules across 30 subclasses when comparing DH patients, diabetes mellitus (DM) patients, and healthy controls [41].

Table 2: Lipid Metabolites Identified in Diabetes with Hyperuricemia Using UHPLC-MS/MS

| Lipid Category | Specific Metabolites | Alteration Trend | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triglycerides (TGs) | TG(16:0/18:1/18:2) and 12 other TGs | Significantly upregulated | Indicates disrupted neutral lipid metabolism |

| Phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) | PE(18:0/20:4) and 9 other PEs | Significantly upregulated | Suggests membrane lipid remodeling |

| Phosphatidylcholines (PCs) | PC(36:1) and 6 other PCs | Significantly upregulated | Reflects alterations in major phospholipid species |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Not specified | Significantly downregulated | Indicates potential signaling pathway disruptions |

Multivariate analyses confirmed distinct lipidomic profiles among the groups, with pathway analysis identifying glycerophospholipid metabolism (impact value: 0.199) and glycerolipid metabolism (impact value: 0.014) as the most significantly perturbed pathways in DH patients [41].

Lipidomic Stratification of Diabetic Retinopathy Stages

LC-HRMS has demonstrated exceptional utility in stratifying stages of diabetic retinopathy (DR) through comprehensive serum lipidomic profiling [4]. Using liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS), researchers analyzed serum from 167 participants including non-diabetic retinopathy (NDR) controls, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) patients, and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) patients [4].

The MTBE/methanol extraction method was employed for its effectiveness in extracting both polar and nonpolar metabolites while providing excellent reproducibility [4]. Machine learning approaches applied to the LC-HRMS data enabled effective classification of DR stages based on lipidomic profiles, highlighting the potential of HRMS-derived data for developing predictive biomarkers in diabetic complications [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized UHPLC-MS/MS Protocol for Lipidomics

Sample Preparation (Based on [41]):

- Collect fasting blood samples and centrifuge at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature

- Aliquot 0.2 mL of upper plasma layer into 1.5 mL centrifuge tubes

- Store at -80°C until analysis

- Thaw samples on ice and vortex

- Extract lipids using methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE)/methanol method: Add 200 μL of 4°C water to 100 μL plasma, mix, then add 240 μL of pre-cooled methanol

- Add 800 μL MTBE, mix, and sonicate in low-temperature water bath for 20 minutes

- Let stand at room temperature for 30 minutes

- Centrifuge at 14,000 g for 15 minutes at 10°C

- Collect upper organic phase and dry under nitrogen

- Reconstitute in 100 μL isopropanol for analysis

Chromatographic Conditions (Based on [41]):

- Column: Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: A: 10 mM ammonium formate in water; B: 10 mM ammonium formate in acetonitrile-isopropanol

- Gradient: Optimized for comprehensive lipid separation

- Temperature: Maintained at constant temperature appropriate for lipid stability

Mass Spectrometry Parameters:

- Ionization: Electrospray ionization (ESI) in positive and negative modes

- Acquisition: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for targeted lipids or data-dependent acquisition for untargeted approaches

- Collision energies: Optimized for specific lipid classes

Representative LC-HRMS Protocol for Metabolic Profiling

Sample Preparation (Based on [42]):

- Collect fasting plasma using EDTA anticoagulation

- Precipitate proteins with methanol under vigorous shaking for 2 minutes

- Centrifuge and divide resulting extract into fractions for different analysis modes

- Implement rigorous quality control with pooled matrix samples

Chromatographic Conditions (Based on [42]):

- Utilize different chromatographic columns for hydrophilic and hydrophobic compounds

- Employ HILIC chromatography for polar metabolites under basic conditions

- Use reversed-phase C18 columns for hydrophobic compounds

- Mobile phases may include water and acetonitrile with 10 mmol/L ammonium formate

Mass Spectrometry Parameters (Based on [42] [4]):

- Instrumentation: Q-Exactive or similar high-resolution/accurate mass spectrometer

- Resolution: ≥20,000 FWHM for precise mass measurement

- Ionization: Heated electrospray ionization (HESI-II)

- Acquisition: Full-scan MS with data-dependent MS/MS for top N ions

- Mass accuracy: Maintain <5 ppm with regular calibration

Visualized Workflows and Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Lipidomics in Diabetic Complications

Perturbed Lipid Pathways in Diabetic Complications

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for LC-MS Based Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MTBE/Methanol Extraction System | Simultaneous extraction of polar and nonpolar metabolites with high reproducibility and recovery [4] | Serum lipidomics in diabetic retinopathy [4] |

| QuEChERS Kits | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged and Safe sample preparation for multi-analyte extraction [37] | Pesticide analysis in food; adaptable to biological samples [37] |

| UHPLC BEH C18 Columns (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm) | High-resolution chromatographic separation with sub-2μm particles for complex lipid separations [41] [42] | Lipid class separation in diabetes-hyperuricemia studies [41] |

| Ammonium Formate Buffers | Mobile phase additive providing improved ionization efficiency and chromatographic performance [41] [42] | Lipidomic profiling in various biological matrices [41] |

| Quality Control Pooled Matrix | Monitoring analytical performance and correcting instrumental drift across large sample sets [42] | Long-term metabolomic studies in diabetic complications [42] |

Platform Selection Guidelines

Decision Framework

The choice between UHPLC-MS/MS and LC-HRMS should be guided by specific research objectives:

Select UHPLC-MS/MS when:

- Analyzing predefined lipid targets with required high sensitivity

- Conducting high-throughput quantitative analyses in clinical cohorts

- Working within established regulatory frameworks requiring validated MRM methods

- Studying known metabolic pathways with well-characterized biomarkers [37]

Select LC-HRMS when:

- Conducting discovery-phase research without predefined targets

- Suspecting unknown or unexpected metabolites in diabetic complications

- Requiring retrospective data analysis without re-extracting samples

- Needing to differentiate isobaric compounds in complex matrices [40] [37]

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The distinction between these platforms is blurring with technological advancements. Modern HRMS instruments are addressing previous limitations in sensitivity and dynamic range [39]. There is growing interest in combined approaches using HRMS for discovery and MS/MS for validation [36]. Additionally, integrated ion mobility separation adds another dimension of resolution for complex lipid analyses [37].

Future applications in diabetic complications research will likely leverage the complementary strengths of both platforms through tiered analytical approaches, with LC-HRMS for comprehensive profiling and UHPLC-MS/MS for focused validation in large clinical cohorts.

The identification and verification of robust biomarkers are paramount for understanding the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. In the specific context of lipid metabolites and diabetic complications, this guide provides a comparative analysis of targeted and untargeted metabolomics strategies. It details how a cross-validated framework, which integrates the discovery power of untargeted methods with the precision of targeted assays, can enhance the rigor and translational potential of biomarker research for conditions such as diabetic kidney disease (DKD).

Metabolomics, the comprehensive study of small molecules, is crucial for elucidating the biochemical landscape of diabetic complications [43]. The two primary methodologies—untargeted and targeted metabolomics—offer complementary insights. Untargeted metabolomics is a global, hypothesis-generating approach that aims to capture all measurable metabolites in a sample, including unknown compounds [44] [45]. Conversely, targeted metabolomics is a hypothesis-driven approach focused on the precise identification and absolute quantification of a predefined set of metabolites [44] [45].

In the field of diabetic complications research, particularly concerning lipid metabolites, each approach has a distinct role. Untargeted methods can reveal novel lipid species and pathways associated with disease progression, while targeted methods are indispensable for validating these findings and establishing clinically applicable assays. A cross-validated approach that sequentially employs both strategies mitigates the limitations of each, creating a more robust pipeline for biomarker verification [44] [45].

Comparative Analysis: Targeted vs. Untargeted Metabolomics

The choice between targeted and untargeted metabolomics hinges on the research objective. The table below summarizes the core differences, providing a framework for selection.

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Targeted and Untargeted Metabolomics

| Feature | Untargeted Metabolomics | Targeted Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Comprehensive detection of known and unknown metabolites [44] [45] | Precise measurement of predefined metabolites [44] [45] |

| Scope | Broad (100s to 1000s of compounds) [46] | Narrow (dozens to ~100 compounds) [46] |

| Approach | Exploratory, hypothesis-generating [45] | Confirmatory, hypothesis-driven [45] |

| Quantification | Semi-quantitative (relative) [44] [45] | Absolute quantification [44] [45] |

| Standards | Not strictly required [45] | Isotopically labeled internal standards essential [44] [45] |

| Ideal Use Case | Biomarker discovery, pathway analysis [47] | Biomarker validation, clinical assay development [44] |

Advantages and Disadvantages

Untargeted Metabolomics

- Advantages: Its primary strength is its unbiased nature, allowing for the discovery of novel biomarkers and unexpected metabolic relationships without prior knowledge of the metabolome [44] [45]. It provides extensive coverage, enabling the systematic measurement of thousands of metabolites in a single analysis [44].

- Disadvantages: It generates complex data that requires extensive processing and sophisticated statistical analysis [44] [45]. The identification of unknown metabolites is challenging without reference standards, and the method suffers from decreased precision due to relative quantification and a bias toward detecting higher-abundance metabolites [44] [45].

Targeted Metabolomics

- Advantages: This approach offers high sensitivity, specificity, and precision by using isotopically labeled standards for absolute quantification, which minimizes false positives and analytical artifacts [44] [45]. It is optimized for quantifying specific metabolites of interest with high accuracy and reproducibility.

- Disadvantages: Its focused nature means it is limited to a predefined set of metabolites, creating a high risk of missing relevant biomarkers outside the target panel [44] [45]. It is dependent on prior knowledge and the commercial availability of validated standards [45].

Cross-Validated Workflow for Biomarker Verification

A synergistic, cross-validated workflow leverages the strengths of both untargeted and targeted methods to deliver verified, high-confidence biomarkers. The following diagram and protocol outline this integrated approach.

Diagram 1: Integrated cross-validation workflow for biomarker verification, combining untargeted discovery and targeted validation phases.

Experimental Protocols

Phase 1: Untargeted Discovery for Candidate Biomarker Identification

- Sample Preparation: Employ a global metabolite extraction protocol suitable for a wide range of lipid species. A biphasic liquid-liquid extraction using methanol and chloroform (e.g., Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods) is widely used to simultaneously extract polar and non-polar metabolites [43]. For lipid-focused studies, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) is also an effective non-polar solvent [43].

- Data Acquisition: Utilize high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) platforms, such as Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR-MS) or Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) mass analyzers [48]. FT-ICR-MS offers unmatched mass resolution and accuracy, enabling precise molecular formula assignment and differentiation of thousands of compounds in complex biological samples, which is critical for discovering unknown lipid metabolites [48]. Coupling with Liquid Chromatography (LC) or direct infusion can be used.

- Data Processing and Analysis: Process raw data using software tools (e.g., XCMS, MZmine) for peak picking, alignment, and normalization [47]. Subsequently, apply multivariate statistical analyses (e.g., PCA, PLS-DA) to identify metabolite features that significantly differentiate sample groups (e.g., diabetic patients with complications vs. those without) [47]. This yields a list of candidate biomarkers for validation.

Phase 2: Targeted Validation for Absolute Quantification

- Sample Preparation: Perform specific extraction procedures optimized for the candidate lipid metabolites. A key step is the addition of isotopically labeled internal standards for each target analyte prior to extraction. This controls for variability in extraction efficiency and ionization, enabling absolute quantification [44] [43].

- Data Acquisition: Use tandem mass spectrometry systems, typically triple quadrupole (QQQ) instruments operating in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode [44]. This setup provides high sensitivity, specificity, and a broad dynamic range for the precise quantification of the predefined metabolite panel.

- Cross-Validation and Statistical Assessment: According to ICH M10 guidelines for bioanalytical method validation, a cross-validation between the untargeted screening results and the targeted quantitative assay is essential when combining data for regulatory submission [49]. This involves analyzing a set of samples (n>30 recommended) with both methods and assessing the agreement. Statistical measures may include calculating the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the mean percent difference to evaluate bias and using Deming regression or Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) to quantify agreement [49]. This step confirms that the semi-quantitative data from the discovery phase reliably predicts the absolute concentrations obtained in validation.

Application in Diabetic Complications Research

Dysregulated lipid metabolism is a hallmark of type 2 diabetes and its microvascular complications [3]. Research has highlighted the role of ectopic lipid deposition and lipotoxicity in organs like the kidneys, retina, and nerves [3]. In this context, metabolomics is instrumental in identifying specific lipid species and pathways involved.

Key Lipid Biomarkers and Experimental Data

Novel lipid-related indices such as the Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI), Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP), and Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) have shown promise as biomarkers. A 2025 meta-analysis synthesized evidence on their association with diabetic microvascular complications [6].

Table 2: Association of Novel Lipid Biomarkers with Diabetic Kidney Disease (DKD) - Meta-Analysis Data [6]

| Biomarker | Calculation Formula | Weighted Mean Difference (WMD) in DKD vs. Control | Odds Ratio (OR) for DKD Risk per 1-unit increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Accumulation Product (LAP) | Men: [WC (cm)-65] × TG (mmol/L)Women: [WC (cm)-58] × TG (mmol/L) |

WMD: 12.67 (95% CI: 7.83, 17.51; P<.01) | OR: 1.005 (95% CI: 1.003, 1.006; P<.01) |

| Atherogenic Index of Plasma (AIP) | log10(TG/HDL-C) |

WMD: 0.11 (95% CI: 0.03, 0.19; P<.01) | OR: 1.08 (95% CI: 1.04, 1.12; P<.01) |

| Visceral Adiposity Index (VAI) | Men: (WC/39.68 + BMI/1.88) × (TG/1.03) × (1.31/HDL)Women: (WC/36.58 + BMI/1.89) × (TG/0.81) × (1.52/HDL) |

WMD: 0.63 (95% CI: 0.38, 0.89; P<.01) | OR: 1.05 (95% CI: 1.03, 1.07; P<.01) |

Abbreviations: WC, Waist Circumference; TG, Triglycerides; HDL-C, High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; BMI, Body Mass Index; CI, Confidence Interval.

The data in Table 2 demonstrates that patients with DKD have significantly higher levels of LAP, AIP, and VAI compared to those without DKD, and each unit increase in these biomarkers is associated with a elevated risk of DKD [6]. However, the same meta-analysis found no significant association between these biomarkers and Diabetic Retinopathy (DR), and the overall diagnostic accuracy for DKD was modest, underscoring the need for more specific lipid metabolite panels and the application of the cross-validated workflow to discover and verify superior biomarkers [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Metabolomics Workflows

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Methanol/Chloroform | A classic biphasic solvent system for global metabolite extraction, separating polar metabolites (methanol phase) from non-polar lipids (chloroform phase) [43]. |

| Methyl tert-Butyl Ether (MTBE) | A non-polar solvent effective for the specialized extraction of lipophilic metabolites, including triglycerides and cholesterol esters [43]. |