Long-Term Safety of CRISPR Systems: A Comprehensive 2025 Review of Genomic Risks, Clinical Progress, and Safety Mitigation

This article provides a critical analysis of the long-term safety profiles of major CRISPR-Cas systems, including nucleases, base editors, and prime editors, for a professional audience of researchers and drug...

Long-Term Safety of CRISPR Systems: A Comprehensive 2025 Review of Genomic Risks, Clinical Progress, and Safety Mitigation

Abstract

This article provides a critical analysis of the long-term safety profiles of major CRISPR-Cas systems, including nucleases, base editors, and prime editors, for a professional audience of researchers and drug developers. It explores the foundational mechanisms behind genomic risks, such as structural variations and off-target effects, and details the methodologies for their detection and quantification. The content covers current strategies for safety optimization and troubleshooting, including the use of high-fidelity variants and improved delivery systems. A comparative framework is presented to guide the selection of appropriate editing tools based on specific therapeutic applications, integrating the latest pre-clinical and clinical evidence to inform robust safety assessments for the clinical translation of gene therapies.

Unpacking the Mechanisms: Foundational Safety Concerns Across CRISPR Platforms

The revolutionary potential of CRISPR-based genome editing in treating genetic diseases is tempered by a fundamental biological challenge: the unpredictable nature of cellular DNA repair machinery. When CRISPR nucleases create double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, the cellular response determines whether the edit will be therapeutic, ineffective, or potentially harmful [1]. This repair process is especially complex in non-dividing human cells like neurons and cardiomyocytes, which represent crucial targets for many genetic diseases but have historically been difficult to edit efficiently [1]. The competing DNA repair pathways—predominantly error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and more precise homology-directed repair (HDR)—respond differently across cell types, creating a central dilemma for therapeutic development.

While Cas9 has been the most extensively characterized CRISPR nuclease, the expanding toolkit now includes Cas12 variants with distinct mechanistic properties. Understanding how these different nucleases engage with DNA repair pathways is critical for advancing safe and effective therapies. Recent studies reveal that beyond well-documented concerns about off-target effects, CRISPR systems can induce large structural variations including chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions, raising substantial safety concerns for clinical translation [2]. This comparative analysis examines how Cas9 and Cas12 nucleases trigger complex DNA repair responses, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to inform therapeutic development.

Mechanistic Differences Between Cas9 and Cas12 Nucleases

Molecular Architecture and Cleavage Mechanisms

Cas9 and Cas12 nucleases employ fundamentally different mechanisms for DNA recognition and cleavage, which in turn influence how they trigger DNA repair pathways. Cas9 requires two separate RNA molecules—a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA)—which are often combined into a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) for experimental simplicity [3]. The Cas9-sgRNA complex recognizes a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence of NGG (where N is any nucleotide) and creates a blunt-ended DSB approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [3]. This blunt-end cut activates classical DNA repair pathways in a manner similar to endogenous DSBs.

In contrast, Cas12a (formerly Cpf1) utilizes a single crRNA without requiring a tracrRNA, simplifying RNA design for some applications [4]. It recognizes a T-rich PAM (TTTN) and creates a staggered cut with a 4-5 nucleotide overhang, leaving cohesive ends rather than blunt ends [4]. This structural difference in the cleavage product may influence how the DNA ends are processed by repair enzymes. Additionally, Cas12a possesses collateral cleavage activity against single-stranded DNA after target recognition, though this feature is primarily utilized in diagnostic applications rather than therapeutic editing.

DNA Repair Pathway Engagement

The structural differences in DSBs created by Cas9 and Cas12 nucleases lead to differential engagement with DNA repair pathways. Blunt-end breaks produced by Cas9 are typically channeled into classical NHEJ (cNHEJ) or microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathways, while staggered ends from Cas12a may more readily engage in alternative end-joining pathways that utilize the short overhangs for alignment [4]. Recent evidence suggests that these initial engagement differences can significantly impact editing outcomes, particularly in non-dividing cells where certain repair pathways are less active.

In dividing cells such as induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), Cas9-induced DSBs predominantly yield larger deletions characteristic of MMEJ, while in genetically identical post-mitotic neurons, the same breaks result primarily in smaller indels associated with NHEJ [1]. This cell-type-specific repair preference highlights how the same nuclease can produce dramatically different outcomes depending on the cellular context. For Cas12a, studies in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii demonstrate slightly higher precision in single-strand templated DNA repair compared to Cas9, though with fewer total target sites available within the genome [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Cas9 and Cas12 Nucleases

| Property | Cas9 | Cas12a (Cpf1) | Cas12f1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM Sequence | NGG (SpCas9) | TTTN | TTTN |

| Guide RNA | crRNA + tracrRNA (often fused as sgRNA) | crRNA only | crRNA only |

| Cleavage Type | Blunt ends | Staggered cuts (5' overhangs) | Staggered cuts |

| Size | ~1368 amino acids (SpCas9) | ~1300 amino acids (AsCas12a) | ~400-500 amino acids |

| Primary Repair Pathway | NHEJ-dominated | Mixed NHEJ/MMEJ | Mixed NHEJ/MMEJ |

| Multiplexing Capability | Requires multiple sgRNAs | Native processing of crRNA array | Native processing of crRNA array |

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes

Efficiency and Precision Across Systems

Direct comparative studies reveal meaningful differences in editing efficiency and precision between Cas9 and Cas12 nucleases. In algal models, Cas9 and Cas12a ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) co-delivered with single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) repair templates induced similar total editing levels (20-30% in all viably recovered cells), but Cas12a demonstrated slightly higher precision in templated editing [4]. However, Cas9 alone induced more edits at certain loci and provided access to significantly more target sites—8 times more in promoter regions and 32 times more in coding sequences [4]. This tradeoff between targetable space and precision must be considered when selecting a nuclease for specific applications.

In bacterial systems targeting antibiotic resistance genes, both Cas9 and Cas12f1 demonstrated 100% eradication efficacy against KPC-2 and IMP-4 carbapenemase genes when combined with appropriate guide RNAs [5]. Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that CRISPR-Cas3 showed higher eradication efficiency than both Cas9 and Cas12f1 systems, though each system has unique advantages and characteristics [5]. This highlights how nuclease selection depends on the specific application, with Cas3 potentially offering advantages for complete elimination of genetic elements.

Structural Variations and Genomic Integrity

Beyond simple indels, CRISPR nucleases can induce large structural variations that pose significant safety concerns for therapeutic applications. Recent studies utilizing genome-wide methods like CAST-Seq and LAM-HTGTS have revealed that Cas9 editing can cause kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions, chromosomal truncations, and translocations between heterologous chromosomes [2]. These structural variations are particularly exacerbated when using DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency, with one study reporting a thousand-fold increase in translocation frequency [2].

The risk profile differs between nuclease platforms. While high-fidelity Cas9 variants and paired nickase strategies reduce off-target activity, they still introduce substantial on-target structural variations [2]. Similarly, nick-based systems like base editors or prime editors lower but do not eliminate genetic alterations, including structural variants [2]. This suggests that all CRISPR systems carry some risk of genomic aberrations that must be carefully evaluated in therapeutic contexts.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes Across CRISPR Systems

| Outcome Metric | Cas9 | Cas12a | Cas12f1 | Cas3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Editing Efficiency | 20-30% (with ssODN) [4] | 20-30% (with ssODN) [4] | Similar to Cas9/Cas12a [5] | Higher than Cas9/Cas12f1 [5] |

| Precision Editing | Moderate [4] | Slightly higher than Cas9 [4] | Data limited | Data limited |

| Targetable Sites | 8-32x more than Cas12a [4] | Limited by T-rich PAM [4] | Limited by T-rich PAM [5] | Limited by GAA PAM [5] |

| Large Deletions | Kilobase- to megabase-scale reported [2] | Data limited | Data limited | Processive degradation [5] |

| Chromosomal Translocations | Reported, exacerbated by DNA-PKcs inhibitors [2] | Not thoroughly investigated | Not thoroughly investigated | Not thoroughly investigated |

Experimental Approaches for Assessing Repair Outcomes

Methodologies for Kinetic Analysis of DNA Repair

Understanding the kinetics of DNA repair following CRISPR editing is crucial for predicting therapeutic outcomes. In a landmark study comparing repair in dividing versus non-dividing cells, researchers used virus-like particles (VLPs) to deliver controlled amounts of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein to human iPSC-derived neurons and genetically identical iPSCs [1]. This approach enabled acute perturbation of DNA without the confounding factors of persistent nuclease expression. The experimental workflow involved:

Differentiation of iPSCs into cortical-like excitatory neurons using established protocols, with immunocytochemistry confirming >99% of cells were Ki67-negative (post-mitotic) by Day 7 and ~95% expressed neuronal marker NeuN [1].

VLP production containing Cas9 RNP, with pseudotyping variations (VSVG-pseudotyped HIV VLPs or VSVG/BRL-co-pseudotyped FMLV VLPs) to optimize delivery efficiency, achieving up to 97% transduction in human neurons [1].

Time-course analysis of indel accumulation using targeted sequencing, revealing that while DSB repair in iPSCs plateaued within days, indels in neurons continued to increase for up to 2 weeks post-transduction [1].

Pathway-specific analysis by examining the distribution of insertion-to-deletion ratios and microhomology usage, demonstrating that neurons predominantly utilized NHEJ-like repair with smaller indels compared to dividing cells [1].

This methodology revealed that post-mitotic cells resolve DSBs over extended timeframes, with important implications for therapeutic editing strategies in non-dividing tissues.

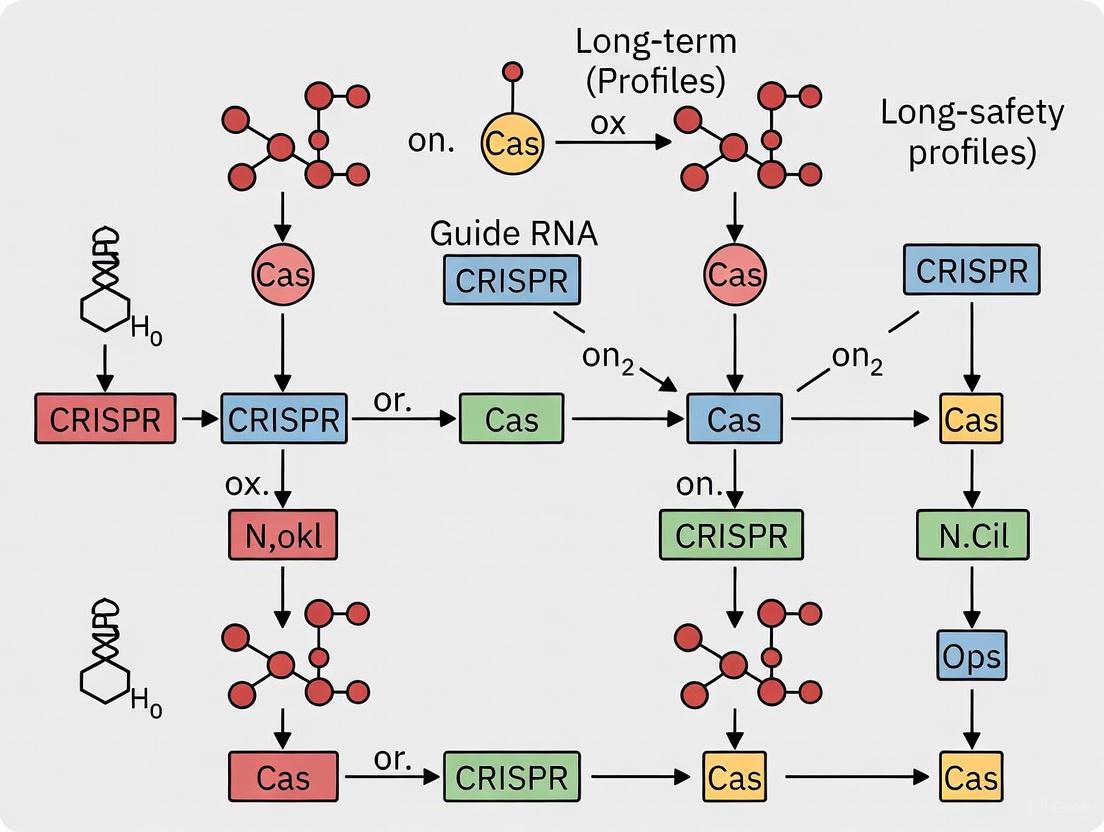

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for kinetic analysis of DNA repair following CRISPR editing, comparing dividing and non-dividing cell models.

Assessing Structural Variations and Genomic Integrity

Conventional short-read sequencing approaches often fail to detect large structural variations because they cannot span the rearranged regions and may lose primer binding sites. Advanced methodologies have been developed to address this limitation:

CAST-Seq and LAM-HTGTS: These genome-wide methods specifically detect chromosomal rearrangements and structural variations by capturing translocation events between on-target and off-target sites [2]. They have revealed that Cas9 editing can induce translocations between heterologous chromosomes, particularly when multiple sites are cleaved simultaneously.

Long-read sequencing: Platforms like PacBio and Oxford Nanopore can span large genomic rearrangements, enabling detection of kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions that are missed by short-read technologies [2]. This approach identified large deletions at the BCL11A locus in hematopoietic stem cells edited for sickle cell disease therapy [2].

Single-cell sequencing: By examining genomic integrity at the single-cell level, researchers can identify mosaic editing outcomes and rare structural variations that might be diluted in bulk analyses [2].

These methodologies have revealed that strategies to enhance HDR efficiency, such as DNA-PKcs inhibition, can dramatically increase the frequency of structural variations. One study found that the DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648 increased translocation frequencies by a thousand-fold while also promoting megabase-scale deletions [2]. This highlights the importance of comprehensive genomic integrity assessment beyond simple indel quantification.

Implications for Therapeutic Development

Safety Considerations Across Clinical Applications

The differential DNA repair responses triggered by Cas9 and Cas12 nucleases have profound implications for therapeutic development. Several key considerations emerge from recent clinical and preclinical studies:

Cell cycle dependence: HDR-based therapeutic approaches requiring precise gene correction are inherently limited to dividing cells, as HDR is cell cycle-dependent (primarily active in S/G2 phases) [1] [6]. This presents a significant challenge for editing non-dividing cells like neurons, cardiomyocytes, and resting immune cells, which predominantly utilize NHEJ pathways.

Prolonged repair in non-dividing cells: The extended timeframe for DSB resolution in post-mitotic cells (up to 2 weeks in neurons) suggests persistent genomic instability in these long-lived cells [1]. This extended vulnerability window could increase the risk of large structural variations or deleterious repair outcomes.

On-target genotoxicity: Beyond the well-characterized risks of off-target effects, recent evidence indicates that on-target structural variations represent a significant safety concern [2]. For the first approved CRISPR therapy (exa-cel for sickle cell disease), large kilobase-scale deletions at the BCL11A editing site in hematopoietic stem cells warrant careful monitoring [2].

Delivery method influences outcomes: The method of CRISPR delivery significantly impacts editing outcomes and safety. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) enable redosing—as demonstrated in trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR) where participants received multiple doses—while viral vectors typically permit only single administrations due to immune concerns [7].

Emerging Strategies for Safer Editing

Several innovative approaches are being developed to mitigate the risks associated with CRISPR-induced DNA repair:

Base and prime editing: These newer CRISPR technologies avoid DSBs altogether by using catalytically impaired Cas variants fused to other enzymes, significantly reducing structural variations while enabling precise nucleotide changes [8].

Epigenetic editing: CRISPR-dCas9 tools targeting chromatin modifications can modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence, offering a reversible approach to gene regulation that avoids DNA damage entirely [8].

Repair pathway modulation: Carefully balanced inhibition of specific repair pathway components (e.g., co-inhibition of DNA-PKcs and POLQ) may reduce certain structural variations while maintaining editing efficiency [2].

Compact Cas variants: Enhanced versions of smaller nucleases like Cas12f1Super and TnpBSuper combine the precision needed for therapeutic applications with improved delivery capabilities due to their smaller size [8].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Repair Studies

| Reagent/Cell Model | Function in DNA Repair Studies | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| iPSC-derived neurons | Model post-mitotic DNA repair | Studying repair kinetics in non-dividing cells [1] |

| Virus-like particles (VLPs) | Acute protein delivery | Controlled nuclease delivery without persistent expression [1] |

| DNA-PKcs inhibitors (AZD7648) | NHEJ pathway inhibition | HDR enhancement studies [2] |

| CAST-Seq/LAM-HTGTS | Structural variation detection | Genome-wide translocation analysis [2] |

| HiFi Cas9 variants | Enhanced specificity | Reduced off-target effects [2] |

| Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) | In vivo delivery | Therapeutic nuclease delivery with redosing capability [7] |

Diagram 2: DNA repair pathways activated by CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks and their associated safety considerations.

The dilemma of double-strand break repair continues to challenge the therapeutic application of CRISPR nucleases. While Cas9 and Cas12 systems have revolutionized genetic engineering, their engagement with DNA repair pathways reveals complex safety considerations that extend beyond simple off-target effects. The emerging understanding of large structural variations, cell-type-specific repair kinetics, and pathway-specific genotoxic risks necessitates more sophisticated safety assessment protocols in therapeutic development.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection between Cas9 and Cas12 systems involves careful consideration of the target cell type (dividing vs. non-dividing), desired edit type (disruption vs. correction), and delivery constraints. The experimental methodologies outlined here—including VLP-mediated delivery, long-read sequencing for structural variation detection, and kinetic analysis of repair outcomes—provide essential tools for comprehensive safety assessment. As the field advances, newer technologies like base editing and prime editing offer promising alternatives that avoid DSBs altogether, potentially mitigating many of the repair-related challenges described here. Nevertheless, understanding the fundamental DNA repair mechanisms triggered by different CRISPR nucleases remains essential for developing safe and effective genetic therapies.

The therapeutic potential of CRISPR-based gene editing is immense, with applications ranging from curative genetic diseases to innovative cancer therapies. While the risk of small, off-target insertions and deletions (indels) has long been recognized, a more complex and significant challenge is emerging: the potential for large structural variations (SVs) and chromosomal translocations. These unintended genomic alterations, which can span kilobases to megabases, present substantial safety concerns that extend beyond traditional off-target effects [2]. As more CRISPR-based therapies progress toward clinical application, understanding and mitigating these risks becomes paramount for ensuring patient safety and therapeutic efficacy.

The landscape of CRISPR-induced damage is remarkably broad. Recent studies have revealed that CRISPR-Cas9 editing can introduce kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions, chromosomal truncations, and complex rearrangements including chromothripsis [2]. Perhaps more concerningly, these structural variants are not confined to the intended target sites but can also occur at atypical non-homologous off-target locations without sequence similarity to the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) [9]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the propensity of different CRISPR systems to induce these large-scale genomic alterations, offering experimental approaches for their detection and analysis to inform therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Systems: Structural Variation Profiles

CRISPR-Cas9: The Most Extensively Studied System

CRISPR-Cas9 has become the workhorse of gene editing technologies due to its simplicity and efficiency. However, a growing body of evidence indicates it can induce significant structural variations:

On-target structural variants: Multiple studies have confirmed that CRISPR-Cas9 regularly generates large deletions (>50 bp) and complex rearrangements at on-target sites. One study in human iPSCs identified large heterozygous deletions of 91.2 kb and 136 kb at the target locus [9].

Off-target structural variants: Unexpected large chromosomal deletions have been observed at atypical non-homologous off-target sites without sequence similarity to the sgRNA [9]. These SVs occurred in approximately 6% of editing outcomes in zebrafish founder larvae and were found to be heritable [10].

Impact of DNA repair modulation: The use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance homology-directed repair (HDR), such as AZD7648, has been shown to exacerbate genomic aberrations, increasing the frequencies of kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions as well as chromosomal arm losses [2].

CRISPR-Cas12f1: A Compact Alternative with Moderate Efficiency

CRISPR-Cas12f1 (also known as Cas14) is characterized by its small size—approximately half the size of Cas9—making it advantageous for delivery challenges. However, its performance in terms of structural variations presents a mixed profile:

Eradication efficiency: In studies targeting carbapenem resistance genes (KPC-2 and IMP-4), CRISPR-Cas12f1 demonstrated the ability to eliminate these genes and restore antibiotic sensitivity [5].

Comparative performance: When compared directly with Cas9 and Cas3 systems for eliminating resistance genes, qPCR assays indicated that Cas12f1 showed lower eradication efficiency than the CRISPR-Cas3 system [5].

CRISPR-Cas3: A Powerful System with Enhanced Activity

CRISPR-Cas3 represents a distinct approach to gene editing, characterized by its processive DNA degradation activity:

Higher eradication efficiency: In comparative studies eliminating carbapenem resistance genes, the CRISPR-Cas3 system demonstrated the highest eradication efficiency among the three systems tested [5].

Unique mechanism: Unlike the precise cleavage of Cas9, Cas3 processively degrades target DNA, making it particularly effective for generating large deletions in bacterial genomes [5].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Structural Variation Risks Across CRISPR Systems

| CRISPR System | Typical SV Size Range | Frequency of SVs | Heritability | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | 50 bp to >1 Mb | ~6% of editing outcomes [10] | Confirmed in zebrafish models [10] | Risk increased with DNA-PKcs inhibitors [2] |

| CRISPR-Cas12f1 | Limited data | Lower than Cas3 [5] | Not assessed | Compact size advantageous for delivery |

| CRISPR-Cas3 | Large deletions | Highest eradication efficiency [5] | Not assessed | Processive degradation mechanism |

Table 2: Detection Methods for Structural Variations and Their Capabilities

| Detection Method | SV Size Detection Range | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linked-read sequencing (10x Genomics) | >50 bp | Phases variants, detects complex SVs | May miss very large SVs |

| Optical genome mapping (Bionano) | Up to 2.5 Mb | Detects very large SVs without sequencing | Lower resolution for small variants |

| Long-read sequencing (PacBio) | >50 bp | Identifies complex haplotypes | Higher cost, lower throughput |

| KROMASURE platform | >2 kb | Single-cell resolution, detects rare events | Specialized equipment required |

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathways for Structural Variation Formation

The formation of structural variations following CRISPR editing is primarily mediated through specific DNA repair pathways that are activated in response to double-strand breaks (DSBs). The diagram below illustrates the key pathways and their relationship to different types of structural variations.

Diagram 1: DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Induced Structural Variations

The formation of structural variations is intimately connected to the cellular DNA damage response system. When CRISPR nucleases create double-strand breaks, multiple competing repair pathways are activated, each with different propensities for generating structural variations:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The predominant repair pathway in human cells, NHEJ is error-prone and typically results in small insertions or deletions (indels). However, when multiple DSBs are introduced or when repair is compromised, NHEJ can mediate large deletions and chromosomal rearrangements [2].

Alternative End-Joining (Alt-EJ): This pathway, which includes microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ), is particularly susceptible to generating large structural variations. Alt-EJ becomes more prominent when key NHEJ factors are inhibited or overwhelmed, leading to kilobase- and megabase-scale deletions [2] [11].

Single-Strand Annealing (SSA): This mechanism is especially relevant when CRISPR editing occurs near inverted repeats (IRs), which are widespread in the human genome (approximately 178 IRs/Mb) [11]. SSA between IRs can lead to large deletions and chromosomal translocations through a "cut-and-paste" mechanism.

The use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency inadvertently shifts the balance toward these more error-prone pathways, particularly Alt-EJ, thereby increasing the frequency of structural variations [2]. Similarly, the presence of inverted repeats near editing sites significantly elevates the risk of translocations, with the rate inversely correlated with the distance between the Cas9 target and the IR [11].

Experimental Approaches for Comprehensive SV Detection

Methodologies for Detecting Structural Variations

Accurate assessment of CRISPR-induced structural variations requires specialized approaches that overcome the limitations of conventional sequencing methods:

Linked-read sequencing (10x Genomics): This approach utilizes barcoded short reads to reconstruct long-range genomic information. In one study, high molecular weight DNAs (90-95% >20 kb) were prepared and sequenced with an average mean depth of 52.8×, enabling detection of large heterozygous deletions [9].

Optical genome mapping (Bionano Genomics Saphyr System): This technology provides structural information about single long DNA molecules (up to 2.5 Mb), offering powerful capabilities for examining structural variants that would be missed by sequencing-based approaches [9].

Long-read sequencing (PacBio): For zebrafish studies, large amplicons (2.6-7.7 kb) spanning Cas9 cleavage sites were constructed and sequenced using the PacBio Sequel system to obtain long and highly accurate (>QV20) reads [10].

Single-cell visualization approaches (KROMASURE): This platform provides single-cell resolution through fluorescent hybridization, enabling direct visualization of chromosomal integrity and structural variants at an individual-cell level, detecting rare events down to 0.1% prevalence [12].

Research Reagent Solutions for SV Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for SV Detection

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Linked-Reads | Whole genome sequencing with haplotype resolution | Barcoded reads for long-range information, 95.4% mapping rate to GRCh38 [9] |

| Bionano Saphyr System | Optical genome mapping | Detects SVs up to 2.5 Mb, confirms large deletions [9] |

| PacBio Sequel System | Long-read sequencing of large amplicons | High accuracy (>QV20), identifies complex haplotypes [10] |

| KROMASURE Platform | Single-cell structural variant detection | Visualizes SVs in individual cells, detects events as rare as 0.1% [12] |

| Nano-OTS | Off-target site identification | Nanopore-based, works in repetitive and complex genomic regions [10] |

Implications for Therapeutic Development and Safety Assessment

The propensity of different CRISPR systems to induce structural variations has profound implications for their therapeutic application:

Risk-benefit assessment: The potential for large structural variations must be weighed against the severity of the target disease. For life-threatening conditions with no alternatives, a higher risk may be acceptable [13].

Regulatory considerations: Agencies including the FDA and EMA now require comprehensive assessment of both on-target and off-target effects, including evaluation of structural genomic integrity [2] [13].

Mitigation strategies: Incorporating homologous segments of inverted repeat loci into the CRISPR-Cas9 system has been shown to substantially mitigate nontargeted translocations without significantly compromising editing efficiency [11].

The detection methodology itself presents challenges, as traditional short-read sequencing and amplicon-based approaches frequently miss large structural variants. When primer binding sites are deleted by large SVs, the amplification necessary for detection fails, leading to underestimation of indel rates and overestimation of HDR efficiency [2]. This underscores the necessity of employing orthogonal detection methods that combine multiple technologies for comprehensive risk assessment.

The comprehensive comparison of CRISPR systems reveals a complex landscape of structural variation risks that extend far beyond small indels. While CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrates significant potential for generating large structural variations and chromosomal translocations, emerging data on alternative systems like Cas12f1 and Cas3 provide insights into their relative safety profiles. The substantial advancement in detection technologies, from long-read sequencing to single-cell visualization approaches, now enables researchers to more accurately quantify and characterize these previously underappreciated risks.

As CRISPR-based therapies continue to advance toward clinical application, a thorough understanding of structural variation risks becomes essential for both therapeutic development and regulatory evaluation. By implementing comprehensive detection strategies and considering the relative risks of different CRISPR systems, researchers can better navigate the safety landscape, ultimately leading to more effective and safer therapeutic applications of this transformative technology.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology revolutionized genome engineering by providing researchers with an easily programmable system for targeted genetic modifications. However, this groundbreaking approach relies on the creation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA, which activates complex cellular repair mechanisms and generates significant safety concerns [14]. Conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems induce DSBs at target sites, which are primarily repaired through either the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels), or the more precise homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, which is inefficient in most therapeutically relevant cell types [15] [16]. Beyond simple indels, DSB induction has been linked to more severe genotoxic consequences, including large structural variations such as chromosomal translocations and megabase-scale deletions, raising substantial safety concerns for clinical applications [2].

The limitations and risks associated with DSBs have driven the development of next-generation editing platforms that can achieve precise genetic modifications without creating these dangerous breaks. Among the most promising of these innovative approaches are base editing and prime editing technologies, which offer enhanced safety profiles while maintaining targeting precision [17] [16]. This review comprehensively examines the mechanisms, capabilities, and comparative safety profiles of these two DSB-free editing platforms, providing researchers with critical insights for selecting appropriate tools for specific experimental or therapeutic applications.

Base Editing: Precision Chemical Conversion Without DSBs

Molecular Mechanism of DNA Base Editing

Base editing represents a fundamental shift from cutting to direct chemical conversion of DNA bases. Developed initially in 2016, base editors are sophisticated fusion proteins that combine a catalytically impaired Cas9 variant (either dead Cas9/dCas9 or nickase Cas9/nCas9) with a single-stranded DNA-modifying enzyme [17] [15]. Unlike conventional Cas9 nucleases that cleave both DNA strands, these modified Cas9 variants serve solely as programmable DNA-binding modules that locally unwind double-stranded DNA, exposing a short stretch of single-stranded DNA for modification by the tethered deaminase enzyme [18].

The base editing process involves several coordinated molecular events. First, the guide RNA directs the base editor complex to the target genomic sequence, where it binds specifically without causing a DSB. The Cas9 component then unwinds the DNA, creating a single-stranded DNA bubble known as an R-loop structure [19]. Within this exposed single-stranded region, the deaminase enzyme performs a precise chemical conversion on a specific nucleotide base. Finally, the edited DNA strand is processed by cellular repair machinery to permanently incorporate the base change [19] [18].

Table 1: Major Classes of DNA Base Editors

| Editor Type | Key Components | Base Conversion | Year Developed | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosine Base Editor (CBE) | nCas9 + Cytidine deaminase (APOBEC1) + UGI | C•G to T•A | 2016 | Correcting C•G to T•A mutations; introducing stop codons |

| Adenine Base Editor (ABE) | nCas9 + Engineered tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA) | A•T to G•C | 2017 | Correcting A•T to G•C mutations; altering splice sites |

| Dual Base Editors | nCas9 + Cytidine & adenosine deaminases | C-to-G & A-to-C | Recent variants | Expanded correction range for transversion mutations |

Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs)

Cytosine base editors pioneer the conversion of cytosine to thymine, effectively achieving C•G to T•A base pair transitions. The core CBE architecture consists of three essential elements: a Cas9 nickase that cuts only the non-edited DNA strand, a cytidine deaminase (typically derived from the APOBEC1 family) that converts cytosine to uracil within the single-stranded DNA bubble, and a uracil glycosylase inhibitor (UGI) that prevents cellular repair enzymes from reversing the edit [18]. The process initiates when the guide RNA positions the CBE at the target site, exposing a window of approximately 5 nucleotides within the single-stranded DNA region. The cytidine deaminase then catalyzes the deamination of cytosine to uracil, creating a U•G mismatch. The Cas9 nickase subsequently cleaves the unedited DNA strand containing the guanine, prompting cellular repair mechanisms to replace the G with an A to resolve the mismatch. Meanwhile, the UGI component ensures that the uracil intermediate remains intact by blocking base excision repair pathways. During DNA replication, the uracil is read as thymine, completing the permanent C•G to T•A conversion without DSB formation [18].

Adenine Base Editors (ABEs)

Adenine base editors perform A•T to G•C base pair conversions through a similar but molecularly distinct mechanism. The creation of ABEs presented a significant engineering challenge, as no natural DNA adenosine deaminases were known to exist. Researchers addressed this limitation through extensive directed evolution of the Escherichia coli tRNA adenosine deaminase (TadA), engineering it to recognize and modify DNA instead of its natural RNA substrate [19] [18]. In the ABE system, the engineered TadA variant forms a heterodimer with wild-type TadA, fused to a Cas9 nickase. When the complex binds to target DNA, the deaminase catalyzes the deamination of adenine to inosine, which the cellular replication machinery interprets as guanine. The nicking of the unedited strand again prompts repair that replaces the thymine with cytosine, resulting in a permanent A•T to G•C change [19] [18]. Structural studies of ABE8e, one of the most efficient adenine base editors, reveal that mutations introduced during directed evolution optimize interactions with the DNA substrate, particularly through modifications to substrate-binding loops and the C-terminal α5-helix, enhancing DNA binding and catalytic efficiency [19].

Diagram 1: Base editing utilizes a fusion protein containing a deactivated Cas9 and a deaminase enzyme to chemically convert one base to another without double-strand breaks. The process involves programmable DNA binding, local unwinding, targeted base deamination, and cellular repair to permanently install the point mutation.

Prime Editing: Search-and-Replace Precision Without DSBs

The Prime Editing Mechanism

Prime editing, first described in 2019, represents an even more versatile DSB-free editing technology that functions as a "search-and-replace" genomic tool [17]. The system consists of two primary components: (1) a prime editor protein that fuses a Cas9 nickase (with inactivated HNH nuclease domain) to an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme, and (2) a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that simultaneously specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [17] [14]. The pegRNA contains both the standard spacer sequence for target recognition and a 3' extension that includes a primer binding site (PBS) and a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) containing the desired genetic modification.

The prime editing process occurs through a sophisticated multi-step mechanism. First, the pegRNA directs the prime editor to the target genomic locus, where the Cas9 nickase creates a single-strand nick in the DNA. The exposed 3' end of the nicked DNA strand then hybridizes with the PBS region of the pegRNA, serving as a primer for reverse transcription. The RT enzyme uses the RTT portion of the pegRNA as a template to synthesize a DNA flap containing the desired edit. This newly synthesized edited flap then competes with the original flap for incorporation into the genome. Successful incorporation and ligation result in a heteroduplex DNA structure containing one edited strand and one original strand. Finally, cellular repair mechanisms or subsequent DNA replication resolve this heteroduplex to permanently install the edit [17] [14] [16].

Versatility and Applications

Prime editing significantly expands the scope of precise genome editing beyond the capabilities of base editors. While base editors are limited to specific transition mutations (C-to-T, T-to-C, A-to-G, and G-to-A), prime editing can theoretically install all 12 possible base-to-base conversions (both transitions and transversions), in addition to targeted insertions (up to dozens of base pairs) and deletions [15] [16]. This remarkable flexibility makes prime editing particularly valuable for therapeutic applications, as it could potentially correct up to 89% of known genetic variants associated with human diseases [15].

The editing precision of prime editing stems from its requirement for three independent hybridization events for successful editing: (1) binding of the prime editor to the target site complementary to the pegRNA spacer, (2) hybridization of the pegRNA's PBS to the 3' end of the nicked target DNA, and (3) hybridization between the synthesized DNA flap containing the edit and the genomic DNA. This multi-step verification process contributes to exceptionally high editing specificity and minimal off-target effects [16]. However, this complexity also presents challenges, as prime editing efficiency varies widely depending on the specific edit, target sequence, and cell type, often requiring extensive optimization of pegRNA design and delivery conditions [16].

Diagram 2: Prime editing employs a nCas9-reverse transcriptase fusion and a specialized pegRNA to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site. The process involves nicking, primer binding, reverse transcription, and flap integration to install precise edits without double-strand breaks.

Comparative Performance and Safety Assessment

Efficiency and Product Purity

Direct comparison of base editing and prime editing reveals distinct performance characteristics that influence their suitability for specific applications. Base editors typically demonstrate higher editing efficiencies (often exceeding 50% in optimized systems) for their respective compatible mutations but are restricted to specific transition mutations [17] [18]. Prime editors offer substantially broader editing capabilities but generally show more variable and often lower editing efficiencies (typically ranging from 1-40% depending on the target and edit type), though continuous optimization is improving these rates [17] [16].

Regarding product purity, base editors can produce bystander edits—unintended modifications of additional bases within the editing window—particularly when multiple target bases of the same type are present in close proximity [19] [18]. Prime editing generally generates higher product purity with fewer unintended byproducts, as the edit is templated precisely by the pegRNA [14]. However, recent advancements in base editor design, including engineered deaminase variants with narrower activity windows, have significantly reduced bystander editing issues [19] [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DSB-Free Editing Technologies

| Parameter | Base Editing | Prime Editing | Traditional CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSB Formation | No | No | Yes |

| Editing Scope | 4 transition mutations | All 12 point mutations, insertions, deletions | Limited by repair pathways |

| Typical Efficiency | High (often >50%) | Variable (1-40%) | High for disruption, low for precise edits |

| Product Purity | Moderate (bystander edits possible) | High | Low for precise edits |

| Indel Formation | Very low | Very low | High |

| Therapeutic Coverage | ~25% of pathogenic SNPs | ~89% of pathogenic variants | Limited by HDR efficiency |

| Delivery Size | Moderate | Large | Moderate |

Safety Profiles and Genotoxic Risks

Both base editing and prime editing offer substantially improved safety profiles compared to DSB-dependent editing approaches. The most significant safety advantage is the dramatic reduction in indel formation, as neither technology relies on error-prone NHEJ for editing [17] [16]. This reduction in indels directly corresponds to decreased risks of on-target genotoxicity, including the large structural variations and chromosomal rearrangements associated with Cas9-induced DSBs [2].

Base editors demonstrate minimal rates of DSB formation and consequently low frequencies of translocations and large deletions. However, they can exhibit off-target deamination activity, particularly in single-stranded DNA regions, though protein engineering has substantially mitigated this risk in newer generations [19] [18]. Prime editing shows exceptionally low off-target activity due to the requirement for multiple independent recognition events, making it one of the most specific genome editing technologies available [14] [16].

Notably, while both technologies avoid intentional DSBs, they do not completely eliminate genomic instability risks. Base editors that incorporate nickase Cas9 still create single-strand breaks, which can potentially be converted to DSBs under certain conditions, though at markedly lower frequencies than dual-strand cleavage [18]. Prime editing primarily operates through single-strand nicking but can occasionally generate DSBs, particularly with imperfect pegRNA designs or in certain genomic contexts [20]. However, these events occur at substantially lower rates than with conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems.

Experimental Applications and Workflows

Key Research Applications

The distinct capabilities of base and prime editors have enabled diverse research applications across multiple biological systems. Base editors have proven particularly valuable for correcting point mutations associated with genetic diseases, with demonstrated success in disease models including sickle cell disease, where they efficiently converted the pathogenic mutation to a harmless variant [17]. Additionally, base editors serve as powerful tools for functional genomics, enabling high-throughput screening of point mutations and their phenotypic consequences through targeted mutagenesis [18].

Prime editing has expanded the range of possible precise genome modifications, enabling researchers to model complex genetic variants more accurately and potentially correct diverse mutation types beyond the scope of base editing. Notable applications include the correction of the sickle cell disease mutation in patient-derived stem cells with approximately 40% efficiency and restoration of the dystrophin reading frame in Duchenne muscular dystrophy models [17] [14]. Prime editing has also been successfully employed for multiplex editing and gene writing applications, where precise sequences are inserted into defined genomic locations [16].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Successful implementation of base editing and prime editing requires careful selection and optimization of molecular components. The table below outlines critical reagents and their functions for researchers designing experiments with these technologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for DSB-Free Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Editor Plasmids | BE4max, ABE8e, PE2, PEmax | Encodes the editor protein | Optimize promoter for target cell type; consider size constraints for delivery |

| Guide RNAs | Target-specific gRNA, pegRNA | Targets editor to specific genomic locus | pegRNA requires PBS and RTT design; gRNA requires optimization of editing window placement |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV, LNP, Electroporation | Introduces editing components into cells | AAV has limited packaging capacity; LNPs ideal for in vivo delivery |

| Validation Tools | Sanger sequencing, NGS, T7E1 assay | Confirms editing efficiency and specificity | Use amplicon sequencing for comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes |

| Optimization Additives | DNA-PK inhibitors, MMR inhibitors | Enhances editing efficiency | Can reduce byproducts but requires careful titration |

Experimental workflows for both technologies typically begin with comprehensive target site selection and guide RNA design, followed by delivery of editing components to target cells using appropriate methods (viral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, or electroporation). After editing, comprehensive analysis of outcomes is essential, including assessment of on-target efficiency, product purity (precise edits versus bystander or imprecise edits), and off-target effects through genome-wide methods such as CIRCLE-seq or GUIDE-seq [18] [16]. For therapeutic applications, additional safety assessments including karyotyping and translocation analysis are recommended to exclude genomic instability [2].

Base editing and prime editing represent transformative advances in genome engineering that effectively address the fundamental safety concern of DSB-induced genotoxicity associated with conventional CRISPR-Cas9 systems. While each technology possesses distinct characteristics—base editing offering higher efficiency for specific transition mutations, and prime editing providing remarkable versatility across all possible mutation types—both significantly expand the therapeutic potential of precise genome editing.

The ongoing optimization of these platforms continues to enhance their safety and efficacy profiles. For base editors, engineering efforts focus on reducing bystander editing, minimizing off-target deamination, and expanding targeting scope through PAM-relaxed Cas variants [19] [18]. Prime editor development concentrates on improving efficiency through protein engineering and pegRNA optimization, particularly for challenging edits and cell types [16]. As these technologies mature and approach broader clinical application, comprehensive assessment of their long-term safety profiles remains essential.

With the first CRISPR-based therapy (Casgevy) receiving regulatory approval in 2023 and numerous base editing and prime editing therapies advancing toward clinical trials, the transition from cutting to rewriting the genome represents the next frontier in genetic medicine [7] [16]. For researchers and therapeutic developers, the strategic selection between base editing and prime editing—or their complementary use—will be guided by the specific genetic modification required, the target cell type, and the therapeutic safety threshold, ultimately enabling precise genetic corrections with minimized risk of genotoxic consequences.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has unlocked unprecedented potential for treating genetic diseases, yet a significant challenge remains: directing cellular repair machinery toward precise homology-directed repair (HDR) instead of error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). While HDR enables accurate gene correction, its natural inefficiency compared to NHEJ has prompted extensive efforts to manipulate DNA repair pathways. These manipulations, however, present a concerning paradox: strategies designed to enhance precision may inadvertently introduce catastrophic genomic damage, including large structural variations (SVs) and chromosomal translocations that pose substantial safety risks for therapeutic applications [2] [21].

The clinical urgency of understanding these risks is amplified by the growing number of CRISPR-based therapies entering clinical trials and the first regulatory approvals of CRISPR medicines like Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia [7] [13]. This article comprehensively compares the genomic safety profiles of predominant HDR-enhancing strategies, synthesizing recent evidence on their associated risks and providing experimental frameworks for assessing genomic integrity in CRISPR-based therapeutic development.

DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Genome Editing

Pathway Competition at Cas9-Induced Double-Strand Breaks

Cellular responses to CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) involve a complex interplay between competing repair pathways, each with distinct fidelity outcomes and cell cycle dependencies:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The dominant DSB repair pathway in human cells operates throughout the cell cycle but is particularly active in G0/G1 phases. The Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer initiates canonical NHEJ by recognizing and binding broken DNA ends, recruiting DNA-PKcs, Artemis, and finally DNA ligase IV to rejoin ends [21]. This pathway frequently produces small insertions or deletions (indels) and is favored in postmitotic cells like neurons and cardiomyocytes [1].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This high-fidelity pathway utilizes homologous donor templates for precise repair but is restricted primarily to S/G2 cell cycle phases. HDR initiates with 5' end resection by the MRN complex and CtIP, creating 3' single-stranded overhangs that RAD51 loads onto to perform strand invasion using homologous sequences [21].

Alternative Pathways: Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), also called polymerase theta-mediated end-joining (TMEJ), utilizes short microhomologies (2-20 nucleotides) and typically generates larger deletions than NHEJ [21].

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and competition between these repair pathways:

Figure 1: DNA Repair Pathway Competition at CRISPR-Cas9-Induced Double-Strand Breaks. Following Cas9 cleavage, competing pathways determine editing outcomes. NHEJ dominates in most cells but produces indels, while HDR enables precise editing but is inefficient. MMEJ utilizes microhomologies and generates larger deletions.

HDR Enhancement Strategies and Their Genomic Risks

DNA-PKcs Inhibition: A Double-Edged Sword

Small molecule inhibition of key NHEJ factors, particularly DNA-PKcs, represents one of the most extensively investigated approaches for HDR enhancement. While effective at shifting the repair balance toward HDR, recent evidence reveals this strategy carries significant risks of severe genomic damage:

Table 1: Genomic Consequences of DNA-PKcs Inhibition During CRISPR Editing

| DNA-PKcs Inhibitor | Intended Effect | Unintended Consequences | Frequency Increase | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZD7648 | HDR enhancement | Kilobase-scale deletions | Significant | Multiple human cell types [2] |

| AZD7648 | HDR enhancement | Megabase-scale deletions | Significant | Multiple human cell types [2] |

| AZD7648 | HDR enhancement | Chromosomal arm losses | Significant | Multiple human cell types [2] |

| AZD7648 | HDR enhancement | Off-target translocations | ~1000-fold | Comprehensive translocation screening [2] |

| Alternative DNA-PKcs inhibitors | HDR enhancement | Chromosomal translocations | Marked rise | Multiple human cell types [2] |

The mechanistic basis for these observations lies in the dual role of DNA-PKcs: it not only promotes NHEJ but also protects DNA ends from excessive resection. When this protection is removed through inhibition, alternative error-prone pathways like MMEJ gain access to DNA ends, resulting in the observed spectrum of large-scale genomic aberrations [2].

Donor Template Engineering: Balancing Efficiency and Accuracy

Modifications to donor DNA templates represent another prominent HDR enhancement strategy with distinct risk-benefit considerations:

Table 2: Donor Template Engineering Strategies and Outcomes

| Strategy | Mechanism | HDR Efficiency | Genomic Risks | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5'-biotin modification | Enhanced Cas9-donor recruitment | Up to 4-fold increase | Reduced template multimerization | Mouse zygotes [22] |

| 5'-C3 spacer modification | Blocked illegitimate end joining | Up to 20-fold increase | Minimal risk when properly targeted | Mouse zygotes [22] |

| Template denaturation (ssDNA) | Single-stranded donor format | Nearly 4-fold increase | Reduced concatemer formation | Nup93 targeting in mice [22] |

| RAD52 supplementation | ssDNA integration factor | 3-fold over ssDNA alone | Increased template multiplication (30%) | Nup93 targeting in mice [22] |

Notably, the combination of RAD52 protein with single-stranded DNA templates, while boosting HDR efficiency, also increased unwanted template multiplication by nearly two-fold, highlighting how even factor-based strategies can compromise precision [22].

Cell-Type Specific Repair Variations

Different cell types exhibit dramatically different DNA repair behaviors, with significant implications for therapeutic editing. Recent research demonstrates that postmitotic human neurons repair Cas9-induced DNA damage over markedly extended timeframes compared to dividing cells—with indels continuing to accumulate for up to two weeks post-transduction versus plateauing within days in iPSCs [1]. Neurons also predominantly utilize NHEJ-like repair with smaller indels, while dividing cells favor MMEJ-like larger deletions [1]. These fundamental differences in repair pathway utilization across cell types necessitate customized HDR enhancement approaches tailored to specific therapeutic contexts.

Experimental Evidence: From Structural Variations to Chromosomal Translocations

Detection Methodologies for Complex Genomic Aberrations

Traditional short-read sequencing approaches frequently fail to detect large structural variations because they cannot span major rearrangements and lose amplification efficiency when primer binding sites are disrupted [2]. Advanced methodologies now enable comprehensive profiling of these hazardous outcomes:

- CAST-Seq and LAM-HTGTS: Specialized techniques for genome-wide profiling of structural variations, particularly chromosomal translocations between on-target and off-target sites [2]

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): The only comprehensive method for detecting all classes of off-target effects, including chromosomal aberrations, though expensive for routine use [23]

- CIRCLE-seq and GUIDE-seq: In vitro and in vivo methods, respectively, for identifying Cas9 cleavage sites across the genome [13] [23]

- ONE-seq and CHANGE-seq: Methods that account for human genetic diversity in off-target profiling, important for predicting population-wide safety [13]

The limitations of conventional analysis methods have led to systematic underestimation of HDR failure rates. As illustrated below, large deletions that remove primer binding sites create "invisible" mutations that misleadingly inflate apparent HDR efficiency:

Figure 2: Detection Blind Spots in Conventional HDR Analysis. Standard amplicon sequencing requires intact primer binding sites. Large deletions that remove these sites prevent amplification, making hazardous structural variations "invisible" and leading to overestimation of HDR efficiency and underestimation of genotoxicity.

Quantifying Structural Variation Landscapes

Recent studies utilizing these advanced detection methods have revealed alarming frequencies of structural variations following CRISPR editing, particularly with HDR enhancement strategies:

- Kilobase to megabase-scale deletions at on-target sites in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) edited at the BCL11A enhancer, a target relevant to sickle cell disease therapy [2]

- Chromosomal translocations between homologous chromosomes resulting in dicentric and acentric chromosomes [2]

- Translocations between heterologous chromosomes following simultaneous on-target and off-target cleavage [2]

- Chromothripsis (chromosomal shattering and reassembly) in a subset of edited cells [2]

The use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors exacerbated all these aberration types, with one study reporting a thousand-fold increase in translocation frequency [2]. Importantly, these structural variations occur not only with standard Cas9 but also with high-fidelity variants and paired nickase systems, though at reduced frequencies [2].

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive Genomic Risk Assessment

Integrated Workflow for Detecting Structural Variations

To adequately assess the genomic instability risks associated with HDR-enhancing strategies, researchers should implement a comprehensive detection workflow:

Table 3: Experimental Protocol for Structural Variation Detection

| Step | Methodology | Key Reagents | Detection Capability | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Initial screening | CAST-Seq or CIRCLE-seq | Cas9-gRNA complex, genomic DNA | Genome-wide off-target sites and translocations | In vitro method requiring validation [2] [23] |

| 2. In vivo confirmation | GUIDE-seq or DISCOVER-Seq | Modified oligonucleotides, cellular material | In vivo off-target activity with cell-type specificity | Lower sensitivity for rare events [13] [23] |

| 3. Structural variant detection | LAM-HTGTS or whole genome sequencing | High molecular weight DNA, sequencing libraries | Chromosomal rearrangements, large deletions | Cost-vs-comprehensiveness tradeoff [2] |

| 4. Clonal analysis | Single-cell sequencing | Individual edited clones | Complex rearrangements in specific lineages | Resource-intensive but highest resolution [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for HDR Safety Assessment

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Safety Assessment Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-PKcs inhibitors | AZD7648 | Suppress NHEJ to enhance HDR | Test propensity for large deletions and translocations [2] |

| HDR-enhancing proteins | RAD52 | Promote single-stranded template integration | Evaluate template multiplication risks [22] |

| Modified donor templates | 5'-biotin, 5'-C3 spacer | Improve HDR efficiency | Assess impact on precise integration vs. concatemer formation [22] |

| Detection reagents | CAST-Seq kit components | Identify chromosomal translocations | Quantify worst-case genotoxic outcomes [2] |

| High-fidelity nucleases | HiFi Cas9, Cas12f variants | Reduce off-target editing | Compare structural variation profiles to wild-type Cas9 [23] |

| p53 inhibitors | Pifithrin-α | Improve editing efficiency in stem cells | Assess oncogenic risk from transient p53 suppression [2] |

The compelling evidence demonstrates that current HDR-enhancing strategies, particularly small molecule inhibition of DNA-PKcs, carry substantial risks of inducing large structural variations and chromosomal translocations that could predispose to malignant transformation. While donor engineering approaches like 5' modifications show promising efficiency gains with potentially lower genotoxic risks, comprehensive safety assessment using advanced detection methods remains essential.

The field is rapidly evolving toward next-generation solutions that may circumvent these challenges entirely, including:

- Prime editing and base editing systems that avoid double-strand breaks altogether [23] [8]

- CRISPR-associated transposase (CAST) systems that enable precise DNA integration without DSBs [24]

- Epigenome editing approaches that modulate gene expression without permanent genomic changes [8]

For therapeutic development, a rigorous benefit-risk framework must guide strategy selection, considering disease severity, editing context (ex vivo vs. in vivo), and patient population. As the field advances toward increasingly sophisticated precision editing, acknowledging and addressing the hidden risks of DNA repair manipulation will be paramount for realizing the full therapeutic potential of CRISPR genome editing while ensuring patient safety.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies for Safety Assessment and Clinical Applications

The clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies hinges on comprehensively assessing their genome-wide specificity to ensure patient safety. Unintended "off-target" edits at sites similar to the intended target pose a potential risk of genotoxicity, including the activation of oncogenes or disruption of tumor suppressors. Consequently, highly sensitive and reliable detection methods are indispensable for profiling the off-target activity of gene-editing reagents. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three key genome-wide screening techniques—CIRCLE-seq, GUIDE-seq, and CAST-Seq—focusing on their methodologies, performance metrics, and applications in building the long-term safety profiles of CRISPR systems.

Method Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of the three off-target detection methods.

| Feature | CIRCLE-seq | GUIDE-seq | CAST-Seq |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method Type | Biochemical (in vitro) | Cell-based (in situ) | Cell-based (in situ) |

| Primary Application | Unbiased, genome-wide off-target nomination | Unbiased, genome-wide off-target identification in cells | Detection of structural variants and complex rearrangements |

| Key Principle | Circularized genomic DNA is cleaved by Cas9 in vitro; cleavage sites are sequenced [25] [26] | Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides are incorporated into DSBs in living cells, serving as tags for sequencing [27] | Identifies chromosomal translocations and structural variants resulting from nuclease cleavage [27] |

| Genomic Context | Lacks cellular context (no chromatin, repair machinery) [25] | Preserves native cellular environment (chromatin state, repair systems) [27] | Analyzes outcomes of DSB repair in a cellular context |

| Sensitivity | Very high (can detect very rare cleavage events) [26] | High (typically ~0.1% in a cell population) [27] | Targeted towards large structural changes |

| Throughput & Scalability | High reproducibility and scalability across different gRNAs [26] | Limited by cell culture and transfection efficiency [26] | Dependent on cell culture |

| Key Limitation | Higher false-positive rate due to lack of cellular context; nominated sites require cell-based validation [25] | May miss off-targets in non-dividing cells or those with low tag integration efficiency; cannot detect complex structural variants [27] | Specifically designed for structural variants, not a broad off-target screening tool |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CIRCLE-seq (Circularization forIn VitroReporting of Cleavage Effects by Sequencing)

CIRCLE-seq is a sensitive, biochemical method for nominating off-target sites in a controlled, cell-free environment [26]. The following protocol is adapted from Tsai et al. and a detailed Journal of Visualized Experiments article [25] [26].

Workflow Overview:

- Genomic DNA (gDNA) Isolation and Shearing: High-quality gDNA is extracted from the cell type of interest (e.g., induced pluripotent stem cells) and randomly sheared via focused ultrasonication into fragments of a desired length (e.g., 150-200 bp) [25].

- DNA Circularization: The sheared DNA fragments are treated with enzymes to create blunt ends and then circularized using DNA ligase. Any remaining linear DNA is degraded by exonucleases, enriching the pool for circular DNA molecules [26] [28].

- In Vitro Cleavage: The purified circular DNA library is incubated with the pre-complexed Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) of interest. The Cas9-gRNA complex cleaves the circular DNA at both on-target and off-target sites, linearizing the fragments [25].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The newly linearized, cleaved DNA fragments are purified. Their ends are repaired, and Illumina sequencing adapters are ligated. The resulting library is amplified by PCR and prepared for high-throughput sequencing [25] [26].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference genome. Cleavage sites are identified by the precise alignment of read start and end positions, which cluster at locations cut by Cas9, allowing for nucleotide-resolution mapping of off-target sites [26] [28].

CIRCLE-seq Workflow: From DNA circularization to off-target site identification.

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by Sequencing)

GUIDE-seq is a cell-based method that captures off-target cleavage events within the native cellular environment, including its chromatin architecture and DNA repair machinery [27].

Workflow Overview:

- Transfection and Tag Integration: Living cells are co-transfected with plasmids encoding Cas9 and the gRNA, along with a proprietary, short, double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (dsODN) tag. When Cas9 induces a DSB, this dsODN tag is integrated into the break site via the cell's endogenous repair pathways [27].

- Genomic DNA Extraction and Shearing: After a brief incubation, genomic DNA is harvested from the cells and sheared into fragments.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Sequencing libraries are prepared, often using a capture-based approach that enriches for genomic fragments containing the integrated dsODN tag. These fragments are then sequenced [27].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The sequenced reads are analyzed to identify the genomic sequences flanking the integrated dsODN tags. The sites where these tags are clustered reveal the locations of Cas9-induced DSBs across the genome [27].

GUIDE-seq Workflow: Tag integration into double-strand breaks for in-situ off-target detection.

CAST-Seq (Circularization for Amplification and Sequencing of Translocations)

CAST-Seq is designed to detect a specific class of off-target effects: large structural variants and chromosomal translocations resulting from the mis-repair of multiple DSBs, which are typically missed by other methods [27].

Workflow Overview:

- Nuclease Delivery and DSB Formation: Cells are transfected with the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery. If off-target cleavage occurs at two or more distant genomic loci, the resulting DSBs can be misrepaired, leading to translocations or other rearrangements.

- gDNA Extraction and Circularization: Genomic DNA is extracted and digested. The DNA is then diluted and circularized via ligation, a process that favors the joining of DNA ends that were in close spatial proximity after fragmentation, including translocation junctions.

- PCR Amplification and Sequencing: The circularized DNA is amplified using primers specific to the suspected on-target and candidate off-target regions. This targeted amplification enriches for fusion fragments containing translocation breakpoints, which are then sequenced [27].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The sequencing data is analyzed to identify chimeric reads that span the breakpoint junctions of chromosomal translocations, providing a direct readout of structural variations induced by the nuclease.

CAST-Seq Workflow: Detection of chromosomal translocations and structural variants.

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful off-target screening experiment requires carefully selected reagents. The table below lists key materials and their functions.

| Reagent / Kit | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | The engineered endonuclease that creates double-stranded breaks at DNA sites complementary to the gRNA [25]. |

| Synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) | The RNA component that programs Cas9 by binding to a complementary DNA target sequence [25]. |

| Gentra Puregene Cell Kit | Used for the isolation of high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from cultured cells, a critical first step for CIRCLE-seq and other methods [25]. |

| Covaris Focused Ultrasonicator | Instrument for performing reproducible and controlled shearing of genomic DNA into fragments of a defined size for library construction [25]. |

| Agencourt AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic beads used for the efficient purification and size selection of DNA fragments throughout various stages of library preparation [25]. |

| Kapa HTP Library Preparation Kit | A suite of reagents optimized for the rapid and efficient preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from input DNA [25]. |

| Blunt-End Ligase | Enzyme critical for the CIRCLE-seq protocol, used to catalyze the circularization of sheared and end-repaired genomic DNA fragments [26] [28]. |

| Plasmid-Safe DNase | An ATP-dependent nuclease that degrades linear double-stranded DNA, used in CIRCLE-seq to enrich for circularized DNA molecules by removing uncircularized linear DNA [25]. |

CIRCLE-seq, GUIDE-seq, and CAST-Seq are complementary tools, each with distinct strengths in the genome-editing safety toolkit. CIRCLE-seq offers unparalleled sensitivity for nominating potential off-target sites in vitro, making it ideal for initial gRNA screening. GUIDE-seq provides critical, cell-based validation of which nominated sites are actually cleaved in a relevant cellular context. Finally, CAST-Seq addresses the critical blind spot of structural variants, which are not detected by the other two methods. A robust safety assessment for therapeutic development, therefore, often requires a combination of these techniques. This multi-faceted approach is essential for building a comprehensive long-term safety profile, ensuring that the next generation of CRISPR therapies is both effective and safe for patients.

The advent of CRISPR-based therapies represents a monumental leap forward in precision medicine. However, accurately assessing their long-term safety profiles requires a comprehensive understanding of their potential genotoxic effects, including the generation of large, unintended structural variations. Short-read sequencing (SRS), the longstanding workhorse of genomic analysis, is frequently employed for these safety assessments. Yet, a growing body of evidence reveals a critical blind spot: SRS systematically fails to detect megabase-scale deletions and other large structural variations (SVs) induced by CRISPR systems. This limitation stems from fundamental technical constraints of SRS technology, which can lead to a dangerous underestimation of genotoxic risk and an overestimation of editing precision. This guide objectively compares the performance of short- and long-read sequencing in detecting these significant alterations, providing researchers with the data and methodologies needed for a more accurate safety comparison of different CRISPR systems.

Technical Limitations of Short-Read Sequencing

Short-read sequencing technologies, such as those offered by Illumina, generate data by fragmenting DNA into small pieces of 50 to 300 base pairs, which are then amplified and sequenced [29] [30]. The primary strength of SRS lies in its high per-base accuracy and cost-effectiveness for detecting small variants like single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short insertions or deletions (indels) [31]. However, this very design creates inherent weaknesses for identifying larger anomalies.

The process of reconstructing the original genome from these short fragments is akin to assembling a complex jigsaw puzzle from tiny, often identical-looking pieces. This becomes particularly problematic in regions of the genome that are repetitive or structurally complex [31] [32]. When a large deletion occurs, the short reads simply cannot span the breakpoints. Instead, they map to the flanking unique sequences, making the large deletion appear as a "normal" region and thus rendering it invisible to standard analysis pipelines [2]. Furthermore, in the context of CRISPR safety assessment, the standard method of targeted amplicon sequencing is especially prone to failure. If a large deletion removes one or both of the primer-binding sites used for amplification, the edited sequence will not be amplified and consequently will not be sequenced, leading to a complete failure of detection and an overestimation of precise editing outcomes [2].

Experimental Evidence of Missed Structural Variations

Key Studies and Quantitative Data

Recent studies leveraging long-read sequencing have starkly highlighted the limitations of SRS. The following table summarizes key experimental findings that directly compare the detection capabilities of short- and long-read technologies for large SVs.

Table 1: Comparative Studies of SV Detection by Sequencing Technology

| Study Context | Short-Read Sequencing Performance | Long-Read Sequencing Performance | Implications for CRISPR Safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characterization of large duplications (Bionano OGM) | Inconsistent resolution of structures, especially for duplications > ~550 kb [33]. | Required multiple single molecules >300 kb to span and unambiguously determine the structure of large interspersed duplications [33]. | Highlights the need for a technology that can physically span the entire altered segment on single molecules for correct structural determination. |

| Comprehensive SV detection evaluation | Recall of SV detection was "significantly lower in repetitive regions" for small- to intermediate-sized SVs [34]. | Superior recall of SV detection in repetitive regions, effectively identifying SVs missed by SRS [34]. | Confirms that SRS provides an incomplete picture of the genomic landscape, particularly in complex regions. |

| Assessment of CRISPR-induced on-target aberrations | Targeted amplicon sequencing fails to detect megabase-scale deletions that remove primer binding sites, leading to overestimation of HDR efficiency [2]. | Revealed kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions, chromosomal truncations, and complex rearrangements at CRISPR on-target sites [2]. | Directly demonstrates that SRS-based safety assessments can be profoundly misleading, missing catastrophic genomic damage. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SV Detection

To reliably identify large structural variations, particularly those induced by CRISPR editing, researchers must employ specialized workflows. The protocol below outlines a robust method utilizing long-read sequencing.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Comprehensive SV Detection

| Research Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate long, intact DNA strands, which are the essential substrate for long-read sequencing. |

| PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore Sequencing Kit | To generate long-read sequencing data. PacBio HiFi offers high accuracy, while Nanopore provides very long read lengths. |

| SV Detection Algorithms (e.g., cuteSV, Sniffles, pbsv) | Specialized bioinformatics tools designed to call structural variations from the alignment files of long-read sequencing data. |

| Bionano Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) | An orthogonal technology that does not rely on sequencing but on direct imaging of labeled DNA molecules to detect large SVs [33]. |

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Extract HMW DNA from CRISPR-edited cells and appropriate control cells (e.g., unedited or mock-edited). The integrity of the DNA is critical and should be verified by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or similar methods.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare libraries according to the manufacturer's instructions for the chosen long-read platform (e.g., PacBio HiFi or ONT). The goal is to achieve sufficient coverage (e.g., >20x) for confident SV calling.

- Data Processing and Alignment:

- Perform base calling and quality control on the raw sequencing data.

- Align the long reads to the reference genome using a suitable aligner like Minimap2 [34].

- Variant Calling and Integration:

- Call SVs using multiple specialized algorithms (e.g., cuteSV, Sniffles) on the aligned data [34].

- Generate a high-confidence set of SVs by integrating calls from multiple tools, for instance, by selecting SVs detected by at least two algorithms.

- Validation: Technically validate a subset of the identified large SVs using an orthogonal method such as Optical Genome Mapping [33] or long-range PCR followed by Sanger sequencing.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive detection of CRISPR-induced structural variations using long-read sequencing. This multi-step process ensures the identification of large, complex SVs that are missed by standard short-read approaches.

Implications for CRISPR Safety Profiles