Microcrystals in Structural Biology: Powerful Techniques for X-ray Crystallography and Beyond

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging microcrystals in modern structural biology.

Microcrystals in Structural Biology: Powerful Techniques for X-ray Crystallography and Beyond

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging microcrystals in modern structural biology. It explores the foundational shift from macro to microcrystallography, detailing advanced methodologies like serial crystallography and MicroED. The content covers practical strategies for sample preparation, delivery, and optimization, while comparing technique strengths for various applications. By synthesizing current literature and emerging trends, this resource enables scientists to overcome traditional crystallization barriers and unlock new possibilities in structure determination and time-resolved studies.

The Microcrystal Revolution: Why Small Crystals Are Transforming Structural Biology

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Microcrystal Growth Challenges

Problem: Failure to nucleate microcrystals or obtaining only amorphous precipitate.

- Cause Analysis: This often results from reaching supersaturation levels too rapidly, leading to a "shower" of uncontrolled nucleation rather than ordered crystal growth [1].

- Solution Protocol:

- Employ batch crystallization methods under oil to precisely control the rate of vapor diffusion [2].

- Implement free interface diffusion (FID), where protein and precipitant solutions are initially separated and allowed to diffuse slowly into one another, promoting a gradual approach to supersaturation [2].

- For membrane proteins, utilize lipidic cubic phase (LCP) or bicelle methods to mimic the native membrane environment, which can stabilize proteins and promote ordered nucleation [1].

Problem: Obtaining microcrystals with a large, heterogeneous size distribution.

- Cause Analysis: Inconsistent nucleation and growth conditions lead to a population of crystals unsuitable for serial crystallography, which requires uniform microcrystals for efficient data collection [2] [3].

- Solution Protocol:

- Apply seeding techniques. Use previously obtained microcrystals as seeds to induce nucleation in a pre-equilibrated protein solution, ensuring a more uniform crystal size [4].

- FID Centrifugation: Following FID, gently centrifuge the crystallization droplet. This pellets the largest crystals, allowing you to harvest the more uniform, smaller crystals from the supernatant [2].

- Top-down approaches: For proteins that only form large crystals, consider controlled crushing or filtering of macro-crystals to generate a more homogeneous microcrystal slurry [4].

Problem: Microcrystals form but do not diffract well.

- Cause Analysis: Crystals may suffer from internal disorder, high mosaicity, or may be multiple crystals grown together (twinning) [1] [5].

- Solution Protocol:

- Post-crystallization treatments: Controlled dehydration of crystals can sometimes contract the crystal lattice, improving order and diffraction resolution [1].

- Additive screening: Introduce small molecules or additives into the crystallization condition or via soaking. These can fill lattice voids and stabilize crystal contacts [1].

- Assess crystal quality before data collection using techniques like second-order nonlinear imaging of chiral crystals (SONICC) to confirm crystallinity, and dynamic light scattering (DLS) to monitor solution homogeneity [2].

Guide 2: Mitigating Radiation Damage in Microcrystals

Problem: Rapid decay of diffraction intensity during X-ray exposure at synchrotrons.

- Cause Analysis: Global radiation damage accumulates as a function of the absorbed X-ray dose, leading to unit cell expansion, increased disorder, and ultimately loss of diffraction [1] [5].

- Solution Protocol:

- Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SSX): Collect a single diffraction image from each of thousands of microcrystals, ensuring that each crystal receives a minimal dose before being replaced [5] [4].

- Fixed-target chips: Use silicon nitride chips with micro-wells to organize crystals. This allows for rastering through a large number of crystals with minimal background and precise control over dose [5].

- Radiation Damage Monitoring: Track specific damage signatures, such as the decay of diffraction intensity or the breakage of disulfide bonds, to establish a safe dose per crystal [5].

Problem: Site-specific damage at metal centers or disulfide bonds, even at low doses.

- Cause Analysis: Redox-active sites (e.g., metals in metalloproteins) and disulfide bonds are particularly susceptible to radiation-induced reduction, which can alter the protein's functional structure [5].

- Solution Protocol:

- Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) at XFELs: Utilize the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle at X-ray free-electron lasers. The femtosecond-duration pulses are so short that they outrun most radiation damage processes [4] [2].

- Data collection at room temperature: While cryo-cooling mitigates global damage, it can trap proteins in non-physiological conformations. Room-temperature serial crystallography provides more functionally relevant structures, though it requires a multi-crystal approach to manage the faster damage rates [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental advantage of using microcrystals over larger, single crystals?

The primary advantage lies in overcoming radiation damage and accessing more physiologically relevant states. Microcrystals enable serial crystallography techniques, where a complete data set is assembled from diffraction patterns collected from thousands of microcrystals, with each crystal exposed to X-rays only once [4] [3]. This "diffract-and-destroy" approach, especially at XFELs, outruns global radiation damage [2]. Furthermore, because microcrystals can be studied at room temperature more easily, they allow researchers to capture protein dynamics and reactions that are often frozen out in traditional cryo-cooled crystals [5] [4].

FAQ 2: My protein only forms large crystals. How can I produce microcrystals for serial crystallography?

You can convert macro-crystals into microcrystals using both top-down and bottom-up strategies [4]:

- Top-Down: Gently crush or shear your existing large crystals using a homogenizer or by passing them through a small-gauge needle or mesh to create a slurry of smaller fragments.

- Bottom-Up: Re-optimize your crystallization conditions to favor nucleation over crystal growth. This can be achieved by:

- Increasing the protein concentration.

- Increasing the precipitant concentration.

- Using seeding techniques to introduce a large number of nucleation sites.

FAQ 3: How much protein is typically required for a serial crystallography experiment, and how can I minimize sample consumption?

Early serial crystallography experiments required massive amounts of protein (grams), but technological advances have drastically reduced this requirement [3]. Theoretical estimates suggest that, under ideal conditions, a full dataset could be obtained with as little as 450 nanograms of protein [3]. To minimize consumption, focus on:

- Low-flow-rate liquid injectors or viscous extrusion methods that reduce the waste of crystal slurry between X-ray pulses [3].

- Fixed-target approaches, where crystals are loaded onto a chip and directly rastered, eliminating the waste associated with continuous liquid streams [5] [3].

FAQ 4: How do I handle the "phase problem" when working with a novel protein that only forms microcrystals?

The phase problem is addressed using methods applicable to microcrystals:

- Molecular Replacement (MR): This is the easiest method if a homologous structure exists. Advanced computational models from AlphaFold or RoseTTAFold can now often serve as suitable search models for MR [1].

- De Novo Experimental Phasing:

- Anomalous Scattering: Incorporate atoms with strong anomalous scattering power (e.g., selenium via selenomethionine, or heavy metals like mercury or gold) into your microcrystals. Techniques like SAD (Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction) can then be used to solve the phase problem [1].

- Serial Crystallography: Both SAD and MAD (Multi-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction) phasing have been successfully implemented in SFX and SSX experiments, making de novo structure determination from microcrystals entirely feasible [1].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Theoretical Minimum Sample Consumption for a Serial Crystallography Dataset

This table estimates the minimum protein required to obtain a complete dataset, assuming ideal conditions: 10,000 indexed patterns, 4 µm cube-shaped crystals, and a protein concentration of 700 mg/mL within the crystal [3].

| Parameter | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Indexed Patterns Required | 10,000 | Depends on crystal symmetry and data completeness. |

| Crystal Volume | 64 µm³ | (4 x 4 x 4 µm) |

| Protein Concentration in Crystal | 700 mg/mL | Example based on a 31 kDa protein [3]. |

| Protein Mass per Crystal | 44.8 pg | Calculated from volume and concentration. |

| Theoretical Minimum Protein Mass | ~450 ng | (10,000 crystals * 44.8 pg/crystal). |

Table 2: Comparing Sample Delivery Methods for Serial Crystallography

| Delivery Method | Principle | Advantages | Challenges / Sample Consumption Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection (Gas Dynamic Nozzle) | Crystal slurry is jetted as a continuous liquid stream into the X-ray beam [2]. | High speed, suitable for time-resolved studies, works with standard crystal suspensions. | High sample consumption as the jet runs continuously between X-ray pulses [3]. |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion (e.g., LCP) | Crystal slurry is mixed with a viscous matrix (e.g., lipidic cubic phase) and extruded as a thin stream [2]. | Dramatically reduced flow rates (nL/min), leading to much lower sample consumption. | Higher technical complexity, potential for high background scattering, optimization required for each sample [3]. |

| Fixed-Target Chips | Microcrystals are deposited into an array of micro-wells on a solid chip, which is rastered through the beam [5]. | Minimal sample waste, allows for pre-characterization of crystal locations, very low background. | Throughput can be limited by chip-scanning speed, potential for crystals to dry out [5] [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Batch Microcrystallization for Serial Crystallography

Objective: To produce large quantities of homogeneous microcrystals using a batch method, as applied to the membrane protein complex Photosystem II (PSII) [2].

- Protein Preparation: Purify the target protein to high homogeneity (>95% purity). For PSII, a concentration of 20 mg/mL was used [2].

- Precipitant Solution Preparation: Prepare a crystallization solution. For PSII, this was 2.5 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 4.5 [2].

- Rapid Mixing: In a microtube, rapidly mix the protein solution and the precipitant solution in a predetermined ratio (e.g., 1:3 volume ratio for PSII) [2].

- Vortexing: Vortex the mixture vigorously for 60 seconds to ensure immediate and homogeneous mixing, which promotes widespread nucleation [2].

- Incubation: Let the mixture sit undisturbed at a controlled temperature (e.g., room temperature) for 4-6 days to allow crystal growth [2].

- Harvesting: Sediment the microcrystals by gentle centrifugation (e.g., 800 rpm for 30 seconds). Remove the supernatant and replace it with a storage or cryo-protection buffer compatible with downstream data collection [2].

Protocol 2: Fixed-Target Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SSX)

Objective: To collect a complete X-ray diffraction dataset from a population of microcrystals while mitigating radiation damage, as demonstrated with copper nitrite reductase [5].

- Crystal Preparation and Soaking: Prepare a slurry of microcrystals (5-15 µm). If studying a reaction, soak crystals with a substrate or ligand (e.g., 100 mM sodium nitrite for 20 minutes) [5].

- Chip Loading: Load the crystal slurry onto a silicon nitride fixed-target chip. The chip contains an array of micro-wells that trap and organize the crystals. Remove excess mother liquor to prevent background scattering [5].

- Mounting and Alignment: Mount the chip in the synchrotron beamline goniometer. Using a microscope, align the chip so that the X-ray beam will intersect with the crystal-containing wells [5].

- Data Collection via Rastering: Program the beamline to automatically raster the chip through the beam. At each well containing a crystal, collect a single, still-shot diffraction image with an exposure time short enough to limit per-crystal dose (e.g., milliseconds) [5].

- Data Processing: Index and integrate the thousands of still diffraction images using specialized software (e.g., CrystFEL, DIALS). Merge the data from all successful "hits" to form a complete dataset for structure solution and refinement [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | A lipid-based matrix used to crystallize membrane proteins; it mimics the native membrane environment and can also be used as a viscous medium for sample delivery [1] [2]. |

| Silicon Nitride Fixed-Target Chips | Microfabricated chips with arrays of micro-wells used to organize microcrystals for low-background, low-waste data collection in serial synchrotron crystallography [5]. |

| Selenomethionine (Se-Met) | Used for experimental phasing. Methionine residues in the protein are biosynthetically replaced with selenomethionine, providing anomalous scatterers for SAD/MAD phasing [1]. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutagenesis | A protein engineering strategy where surface residues with high conformational entropy (e.g., Lys, Glu) are mutated to smaller, ordered residues (e.g., Ala) to promote crystal contacts and improve crystallization odds [1]. |

| Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS) | A technique that uses a slurry of pre-formed microcrystals ("seeds") to nucleate growth in new crystallization drops, helping to expand crystallization conditions and improve crystal reproducibility [1]. |

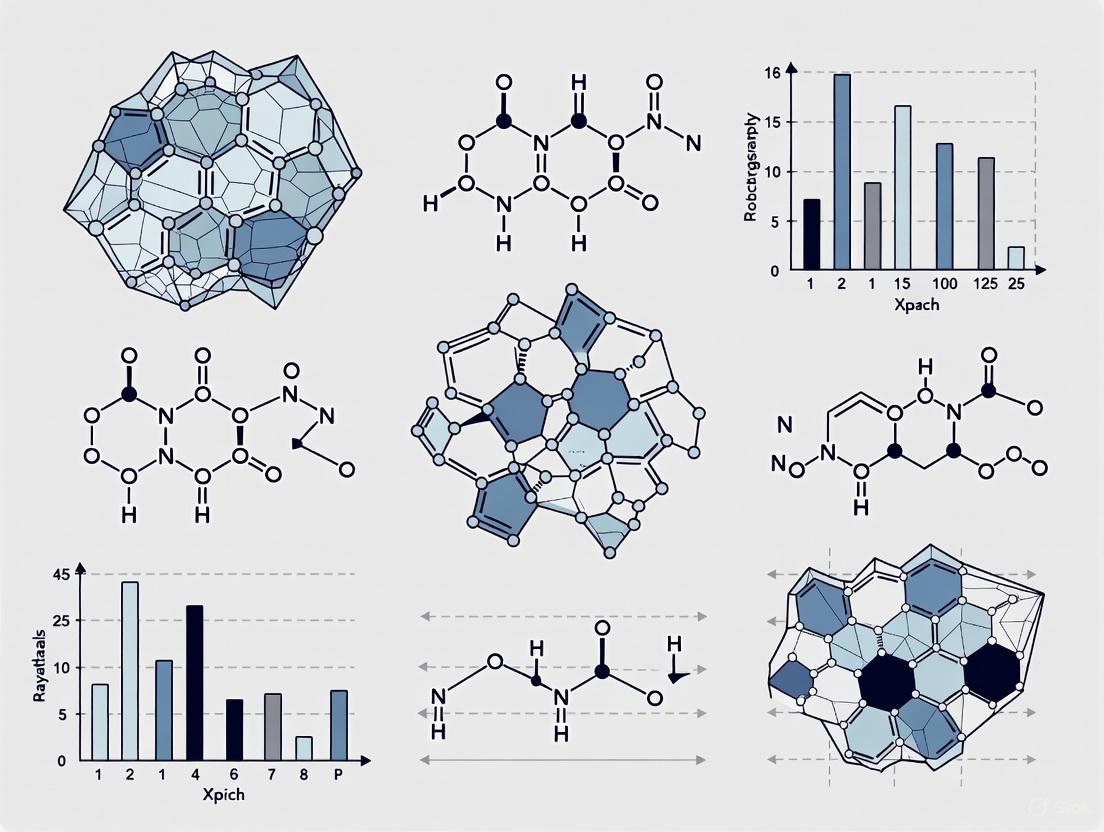

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Serial Crystallography Workflow

This diagram illustrates the core workflow for structure determination using microcrystals and serial crystallography at both synchrotrons and XFELs.

Diagram Title: Serial Crystallography Workflow

Diagram 2: Microcrystal Optimization Pathways

This decision tree outlines common problems encountered during microcrystal work and potential solutions to optimize crystal quality and data collection.

Diagram Title: Microcrystal Optimization Pathways

Microcrystal X-ray crystallography represents a paradigm shift in structural biology, enabling the study of proteins that are recalcitrant to forming large, single crystals. This approach leverages crystals that are one-billionth the size of those required for traditional crystallography, opening new frontiers for research [6]. The two key advantages—enhanced time-resolved studies and increased physiological relevance—make it an indispensable tool for modern researchers and drug development professionals. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and detailed protocols to help you overcome the unique challenges associated with microcrystal experiments.

Core Technical Advantages: A Detailed Look

Enhanced Time-Resolved Studies

Time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography (TR-SFX) at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) allows researchers to capture molecular movies of proteins in action, revealing transient intermediates and detailed reaction mechanisms [7]. The "diffraction before destruction" principle of XFELs enables the use of microcrystals at room temperature, providing unprecedented temporal resolution.

Quantitative Overview of Time-Resolved Techniques

| Technique | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Reaction Initiation Method | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR-SFX at XFELs [7] | Femtoseconds to picoseconds | Atomic | Laser pulses (photosensitive systems) | Light-activated proteins (e.g., heme proteins) |

| Mix-and-Inject (MISC) [3] | Milliseconds to seconds | Atomic | Rapid chemical mixing | Enzyme-substrate interactions |

| Laue Crystallography [8] | ~100 picoseconds | Atomic | Laser pulses | Heme protein dynamics (e.g., hemoglobin) |

| Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) [3] | Milliseconds | Atomic | Mixing or optical triggers | Room-temperature enzyme kinetics |

Increased Physiological Relevance

Microcrystallography offers a more physiologically accurate view of protein structure and function by facilitating data collection at room temperature and reducing crystal-packing artifacts.

- Room-Temperature Data Collection: Serial crystallography is an ideal method for collecting data at room temperature, which helps avoid the structural distortions sometimes caused by cryogenic freezing [9]. This is crucial for observing authentic protein dynamics and allosteric mechanisms [10].

- Reduced Crystal Packing Forces: Smaller crystals often have less pronounced constraints from the crystal lattice. This allows for greater conformational flexibility and can enable the observation of biologically relevant states that are suppressed in larger, more tightly packed crystals [8].

- Study of Dynamic Ensembles: Advanced methods like "multiple structures from one crystal" (MSOX) allow researchers to mine data for conformational heterogeneity, revealing the dynamic landscapes that are essential for protein function [11].

Essential Workflows and Methodologies

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for a TR-SFX experiment, which is foundational for dynamic structural biology.

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Generate a slurry of microcrystals (nanometers to micrometers in size) in their mother liquor. The protein concentration in the crystal is typically high, around 700 mg/mL [3].

- Sample Delivery: Continuously deliver fresh microcrystals into the X-ray beam path. The two primary methods are:

- Reaction Initiation (Time-Resolved): Synchronously trigger the protein's reaction cycle. This is achieved either by:

- Data Collection: An ultra-bright, femtosecond X-ray pulse from an XFEL intersects with a single microcrystal. The pulse is so short that it records a diffraction pattern before the crystal is destroyed by radiation damage [3]. This "diffraction before destruction" principle is key. This process is repeated tens of thousands of times (e.g., >10,000 indexed patterns) to collect a complete dataset [3].

- Data Processing: The individual, partial diffraction patterns from thousands of crystals are indexed, integrated, and merged using specialized software to generate a complete set of structure factors for determining the electron density map and atomic model [9].

Sample Delivery Methods and Consumption

Choosing the right sample delivery method is critical for minimizing sample consumption, a major concern in microcrystallography.

Comparison of Sample Delivery Systems

| Delivery Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Sample Consumption (for a full dataset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection [3] | Continuous jet of crystal slurry | Fast sample replenishment, suitable for high repetition-rate XFELs | High sample waste (most sample is not hit by the X-ray pulse) | Early experiments: grams of protein. Recent optimizations: microgram amounts. |

| Fixed-Target Chips [9] | Crystals loaded on a reusable chip with microwells | Highly efficient sample use, minimal waste, allows crystal pre-screening | Lower data collection speed compared to optimized liquid jets | Highly efficient; consumption approaches the theoretical minimum. |

| High-Viscosity Extruders [3] | Crystal slurry in a viscous matrix (e.g., LCP) | Reduced flow rate and sample consumption, ideal for membrane proteins | Can be more complex to operate | Significantly lower than early liquid jets. |

Theoretical Minimum: Under ideal conditions (4 µm crystal size, 700 mg/mL protein concentration, 10,000 indexed patterns), a full dataset could require as little as ~450 ng of protein [3].

Troubleshooting Guide and FAQ

FAQ 1: My microcrystals are not diffracting well. What could be the problem?

- Cause A: Insufficient Crystal Quality. Microcrystals can suffer from defects, disorder, or poor internal order.

- Solution:

- Optimize Purification: Ensure high sample purity (>95%) and monodispersity. Use multi-step chromatography and analyze monodispersity with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to prevent aggregation [10].

- Post-Crystallization Treatments: Improve crystal order by employing controlled dehydration to contract the crystal lattice, which can enhance resolution [10].

- Use Microseeding: Utilize Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS) to improve crystal size uniformity and quality by using pre-formed microcrystals as nucleation templates [10].

- Solution:

- Cause B: Radiation Damage. Even with femtosecond exposures, cumulative effects can degrade crystals.

FAQ 2: How can I solve the phase problem with microcrystals?

The "phase problem" refers to the loss of phase information in diffraction data, which is essential for structure determination [10].

- Solution A: Molecular Replacement (MR). This is the primary method if a homologous structure exists (>30% sequence identity). The rise of AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold has dramatically expanded the scope of MR, as predicted models can serve as search models [10].

- Solution B: Experimental Phasing. For de novo structure determination.

- Selenium-Methionine (Se-Met) Labeling: Incorporate selenium atoms into the protein via methionine residues. This allows phasing using Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD) and is responsible for over 70% of de novo structures in the PDB [10].

- Heavy Atom Soaking: Soak microcrystals in solutions containing heavy atoms (e.g., mercury or platinum compounds) to introduce anomalous scatterers [10].

FAQ 3: How can I study non-photosensitive proteins with time-resolved methods?

- Solution: Mix-and-Inject Serial Crystallography (MISC). This method is a breakthrough for studying enzymatic reactions.

- Rapid Mixing: A stream of microcrystals is mixed with a stream of substrate or ligand solution just before entering the X-ray interaction region.

- Variable Delay: The time between mixing and probing with the X-ray pulse is controlled by adjusting the length of the tubing between the mixer and the interaction point.

- Data Collection: Diffraction patterns are collected at various time delays, allowing you to reconstruct a molecular movie of the reaction, from substrate binding to product release, with millisecond to second resolution [3].

FAQ 4: My membrane protein microcrystals are unstable. What can I do?

- Solution:

- Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP): Use LCP or bicelles to crystallize and deliver membrane proteins. This mimics the native membrane environment, stabilizing the protein and often leading to higher diffraction quality [10].

- Fusion Protein Strategies: Introduce stable, soluble protein domains (e.g., T4 lysozyme, GST) to the membrane protein. This increases solubility and can provide additional crystal contacts [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) [10] | Membrane protein crystallization and delivery. | Mimics the native lipid bilayer environment, crucial for stabilizing membrane proteins during crystallization and data collection. |

| Selenium-Methionine [10] | De novo structure determination via experimental phasing. | Biosynthetically incorporated into recombinant proteins to provide a strong anomalous signal for SAD/MAD phasing. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutagenesis Kits [10] | Improve crystal contact formation. | Replaces high-entropy surface residues (e.g., Lys, Glu) with smaller residues (Ala, Thr) to promote ordered crystal lattice formation. |

| Microseeding Tools [10] | Improve crystal nucleation and size uniformity. | Uses crushed microcrystals as seeds to initiate growth in new crystallization drops, expanding the range of conditions that yield crystals. |

| Crystallization Chips (Fixed-Target) [9] | Low-volume, high-throughput sample delivery. | Silicon-based chips with thousands of microwells for precisely positioning microcrystals for efficient, low-consumption data collection. |

| High-Viscosity Extruders (e.g., for LCP) [3] | Deliver crystals in a viscous medium for reduced consumption. | Extrudes crystal-laden LCP or other viscous matrices in a thin stream, significantly reducing flow rate and sample waste compared to liquid jets. |

Core Technical Concepts: From Macro to Micro

The shift from traditional macro-crystallography to microcrystal applications is driven by significant advancements in X-ray sources and complementary electron diffraction techniques. These technologies overcome the fundamental limitation of radiation damage that historically required large, perfect crystals.

Advanced X-ray Sources: The development of X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) introduced the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle [12] [3]. By using ultra-bright, femtosecond-duration X-ray pulses, these sources can collect a single diffraction pattern from a microcrystal before the pulse destroys it [3]. This enables Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX), where a complete dataset is built by merging patterns from thousands of individual microcrystals shot across the X-ray beam [3]. Similarly, micro-focused beamlines at synchrotrons (3rd and 4th generation) allow for Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) by using beams smaller than 10 µm in diameter to probe microcrystals with reduced background scatter [3].

Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED): This cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) technique uses a transmission electron microscope (TEM) to obtain diffraction patterns from 3D microcrystals that are one-billionth the size of those required for conventional X-ray diffraction [6] [13]. The strong interaction of electrons with matter means high-resolution structural information can be extracted from crystals ranging from nanometers to a few hundred nanometers in size [6] [13].

Table: Comparison of Advanced Diffraction Techniques for Microcrystals

| Technique | Source | Crystal Size | Key Principle | Sample Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) | X-ray Free-Electron Laser (XFEL) | Micro-to-nano [3] | Diffraction-before-destruction [3] | Liquid injection, Fixed-target [3] |

| Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX) | Synchrotron (Micro-focused beam) | Micro [3] | Reduced background from small beam [3] | Liquid injection, Fixed-target [3] |

| Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) | Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Nano-to-sub-micron [6] [13] | Strong electron-matter interaction [13] | TEM grid [6] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My protein only forms microcrystals or "precipitates." Are my crystallization trials a failure?

No. The presence of microcrystals, even in what appears to be a cloudy precipitate, is no longer a failed experiment but an opportunity for modern techniques. Crystallization drops that appear cloudy should be carefully inspected using methods like UV fluorescence, second-order nonlinear imaging of chiral crystals (SONICC), or negative-stain electron microscopy to identify micro- and nano-crystals that are perfect for MicroED or SX [6].

FAQ 2: How much protein is required for a microcrystal structure determination?

The required amount has decreased dramatically. Early SX experiments required grams of protein, but modern, optimized sample delivery methods have reduced this to the microgram range [3]. The theoretical minimum sample consumption can be as low as 450 ng of protein to obtain a full dataset, assuming 10,000 indexed patterns from 4 µm crystals at a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL [3].

FAQ 3: What is the "phase problem" and how is it solved for a novel microcrystal structure?

The phase problem refers to the loss of phase information of the diffracted waves, which is essential for calculating an electron density map [12]. For novel structures without a known homologous model, the primary experimental method is anomalous scattering. This involves incorporating heavy atoms (e.g., selenium via Se-Met labeling) into the protein and using their wavelength-dependent scattering to infer phase information [12]. For MicroED, the strong interaction of electrons with the crystal also helps mitigate the phase problem, enabling ab initio structure determination [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Optimizing Microcrystal Generation and Handling

A common bottleneck is obtaining a sufficient suspension of high-quality microcrystals.

- Problem: Microcrystals are too small or poorly ordered.

Solution: Employ post-crystallization treatments.

- Procedure: Use techniques like microseed matrix screening (MMS), where pre-formed microcrystals are used as seeds to nucleate growth in new crystallization conditions, leading to more uniform and larger microcrystals [12].

- Monitoring: Use Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) to monitor the formation and quality of microcrystal suspensions directly in their crystallization drops, providing a non-destructive quality check [14].

Problem: Crystals are too large for SX/MicroED but too small for standard X-ray diffraction.

- Solution: Fragment larger crystals.

- Procedure: For crystals in the 1–5 µm range, which are challenging for both traditional and microcrystal methods, use physical fragmentation or a Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscope (FIB-SEM) to mill them down to a suitable size for MicroED [6].

Guide: Managing Radiation Damage in Microcrystal Experiments

All diffraction experiments are susceptible to radiation damage, which degrades crystal quality and data resolution.

- Problem: Rapid decay of diffraction intensity during data collection.

- Solution: Leverage the fundamental properties of advanced sources.

- For XFELs: The "diffraction-before-destruction" approach inherently avoids cumulative damage, as each crystal is used only once [12] [3].

- For MicroED: Use an ultra-low electron dose rate and continuous rotation of the crystal during data collection. A single 3D crystal can tolerate over 90 exposures if the beam exposure is reduced by orders of magnitude [6].

- Universal Practice: Always maintain samples at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., by plunge-freezing in liquid ethane) to mitigate radiation damage [6].

Guide: Solving Data Processing and Scaling Challenges

Systematic errors in diffraction intensities from factors like sample heterogeneity and radiation damage must be corrected through scaling.

- Problem: Inconsistent intensities between symmetry-related reflections.

- Solution: Apply modern scaling algorithms.

- Classical Method: Use least-squares optimization in programs like AIMLESS or XDS to fit a model of common error sources and place all intensities on a common scale [15].

- Modern Alternative: For challenging cases, such as time-resolved studies or fragment screening, use newer algorithms based on variational inference and machine learning (e.g., the

Carelessprogram). These methods can simultaneously infer merged data and correction factors with greater flexibility, improving the accuracy of the final electron density map [15].

Essential Workflows and Decision Pathways

Microcrystal Structure Determination Workflow

The following diagram outlines the critical steps and decision points for determining a structure from microcrystals, from sample preparation to final model validation.

Technical Drivers and Method Selection Logic

This diagram illustrates the technical rationale behind choosing an advanced source or technique based on the specific properties and research goals for a microcrystal sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Microcrystallography

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Mimics the native membrane environment, stabilizing membrane proteins for crystallization [12]. | Crystallization of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane proteins for SX or MicroED [12]. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutagenesis | Replaces high-entropy surface residues (e.g., Lys, Glu) with Ala or Thr to promote crystal contacts and improve lattice formation [12]. | Enhancing crystallization propensity of proteins with flexible regions that resist forming ordered crystals [12]. |

| Selenium-Methionine (Se-Met) | Anomalous scatterer used for experimental phasing via SAD/MAD, crucial for de novo structure determination [12]. | Solving the phase problem for a novel protein with no homologous structure available [12]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) Grid | Standard, electron-transparent support for mounting microcrystals for MicroED data collection [6] [13]. | Screening hundreds of microcrystals deposited on a grid to find suitable candidates for diffraction [6]. |

| Hybrid-Pixel Electron Detector | Fast, direct electron detector capable of single-electron counting and shutterless operation at high frame rates [13]. | Capturing high-quality, low-noise MicroED diffraction patterns with a minimal electron dose to prevent damage [13]. |

Defining Microcrystals: An FAQ for Structural Biologists

What is the general size range for a "microcrystal" in structural biology?

In structural biology, "microcrystal" generally refers to crystals that are just a few micrometres in size or smaller. The specific acceptable size, however, depends heavily on the experimental technique being used. Advanced methods have shifted the paradigm, making samples once deemed too small now viable for high-resolution structure determination [4].

The table below summarizes how the definition of a microcrystal changes across different experimental modalities.

Table 1: Microcrystal Size Definitions by Experimental Modality

| Experimental Modality | Typical Crystal Size Range | Key Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional X-ray Crystallography | Tenths of a millimetre (≥ 100 µm) [4] [3] | Required large, well-ordered single crystals for usable diffraction data. |

| Microfocus Synchrotron (e.g., VMXm) | Sub-micrometre to micrometre [16] | Utilizes a micro-focused X-ray beam (e.g., 0.3 × 2.3 µm) and an in vacuo environment to improve signal-to-noise [16]. |

| Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SMX) | Micrometre-sized (e.g., 1-10 µm) [4] [3] | Data is collected from thousands of microcrystals in a stream, rather than a single large crystal [4]. |

| Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) at XFELs | Micrometre-sized (e.g., 1-3 µm) [16] [3] | Uses ultra-short, bright X-ray pulses in a "diffraction-before-destruction" approach [4] [3]. |

| Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) | Nanometres to sub-micrometre (100 – 300 nm thick) [16] [17] | Crystal depth must be limited to reduce multiple scattering events; electrons interact more strongly with matter than X-rays [16]. |

Why is crystal size definition critical for MicroED experiments?

Crystal size is a more strict and critical parameter in MicroED than in X-ray methods due to the strong interaction of electrons with matter. To limit multiple elastic scattering events that complicate data processing, crystals must be thinner than twice the mean free path of the incident electrons. This typically restricts crystal depth to between 100 and 300 nm in all dimensions [16]. The strong interaction of electrons, however, also allows MicroED to provide atomic-level insights into charged states and hydrogen positions [16] [17].

How do I decide which microcrystallography technique to use?

Choosing the right technique depends on your crystal size, biological question, and available resources. The following workflow can help guide this decision.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Microcrystal Experimental Challenges

FAQ: How can I generate microcrystals from a sample that typically forms large crystals?

Reproducibly preparing small crystals from samples that yield large crystals requires tailored approaches, as no universal recipe exists [4] [16]. The following methods have proven effective:

- Mechanical Crushing (Top-Down): Existing larger crystals can be physically crushed or ground to create a slurry of microcrystals [4] [18].

- Seeding (Bottom-Up): Introducing pre-formed microseeds into fresh crystallization solutions can control and promote the growth of numerous small crystals instead of a few large ones [4] [16].

- Microfluidic Crystallization: Novel microfluidic devices offer precise control over crystallization conditions, enabling the reproducible production of microcrystals [4].

- Batch Crystallization Optimization: Scaling up crystallization from tiny vapour diffusion droplets to larger batch preparations, often guided by phase diagrams, can help fine-tune conditions for microcrystal formation [4].

FAQ: What are the primary methods for delivering microcrystals to the X-ray or electron beam?

Efficient sample delivery is crucial for the success of microcrystal experiments, especially in serial methods. The choice involves trade-offs between sample consumption, speed, and technical complexity [4] [3]. The three primary categories of delivery systems are:

Table 2: Microcrystal Sample Delivery Methods

| Delivery Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection | A stream or jet of crystal slurry is injected across the X-ray beam [3]. | Suitable for time-resolved studies (e.g., MISC). | High sample waste; crystals injected between pulses are lost [3]. |

| Fixed-Target | Crystals are deposited on a solid, low-background chip and raster-scanned through the beam [3]. | Dramatically reduces sample consumption; minimal waste. | Lower data collection speed compared to some liquid jets. |

| Hybrid Methods | Combines features of both liquid and fixed-target approaches [3]. | Aims to balance efficiency and low sample consumption. | Can be technically complex to implement. |

The decision-making process for selecting and preparing a sample for these delivery methods is outlined below.

FAQ: What are the key reagent solutions for microcrystal preparation and delivery?

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microcrystallography

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Mimics the native membrane environment to stabilize membrane proteins for crystallization [19]. | Particularly useful for generating microcrystals of challenging targets like GPCRs. |

| Porous Nucleants (e.g., SDB microspheres, Bioglass) | Provides a heterogeneous surface to reduce the nucleation energy barrier, promoting controlled crystal growth [19]. | Helps avoid excessive microcrystal formation by controlling nucleation. |

| Carbon-Coated EM Grids | Serves as a support for depositing and vitrifying microcrystals for MicroED and fixed-target serial crystallography [16]. | Grids are typically glow-discharged to make the surface hydrophilic for even sample spread [16]. |

| High-Viscosity Carriers (e.g., LCP, grease) | Acts as a medium for extruding crystal slurries in liquid injection systems, reducing flow rate and sample consumption [3]. | Key for high-viscosity extruder (HVE) injection. |

| Seeding Solution | Contains pre-formed microcrystals used to initiate growth in fresh crystallization drops (Microseed Matrix Screening) [19]. | A bottom-up method to generate microcrystals from established crystallization conditions. |

The definition of a microcrystal is inherently tied to the experimental technique, spanning from nanometers for MicroED to micrometers for synchrotron-based serial crystallography. Mastering the size spectrum—through appropriate definition, sample preparation, and delivery—is key to leveraging these powerful tools for tackling challenging structural biology questions, especially in dynamic time-resolved studies.

Advanced Techniques: Serial Crystallography and MicroED in Practice

Core Principles of SFX

What is the fundamental principle that enables damage-free data collection at XFELs? The core operating principle of SFX is "diffraction-before-destruction" [20] [21]. XFELs produce X-ray pulses that are so intense and short (typically tens of femtoseconds) that they can record a diffraction pattern from a microcrystal before the inevitable Coulomb explosion and radiation damage occur [21]. This allows for the collection of high-resolution, damage-free structural data at room temperature, providing a more physiologically accurate picture of the protein structure compared to traditional cryo-cooled methods [20] [4].

How does SFX differ from traditional synchrotron crystallography? SFX represents a paradigm shift from traditional crystallography. Instead of collecting a complete dataset by rotating a single, large crystal at cryogenic temperatures, SFX merges partial "still" diffraction patterns from thousands of microcrystals delivered in a serial fashion at room temperature [20] [22]. The following table summarizes the key differences:

Table: Key Differences Between SFX and Traditional Synchrotron Crystallography

| Feature | Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) | Traditional Synchrotron Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Source | X-ray Free Electron Laser (XFEL) | Synchrotron |

| Pulse Duration | Femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) | Picoseconds to seconds |

| Peak Brilliance | ~10⁹ times higher than synchrotrons [21] | Lower than XFELs |

| Crystal Size | Micro- and nano-crystals (µm to sub-µm) | Typically larger crystals (>10 µm) |

| Data Collection | "One crystal, one shot" | Rotate a single crystal |

| Temperature | Primarily room temperature | Primarily cryogenic (100 K) |

| Radiation Damage | Mitigated via "diffraction-before-destruction" | Mitigated via cryo-cooling |

SFX Experimental Setup and Workflow

An SFX experiment integrates several advanced components to function successfully. The overall workflow, from sample to model, is visualized below.

XFEL Facilities Worldwide

Several international facilities provide the XFEL beamtime required for SFX experiments.

Table: Operational Hard X-ray FEL Facilities for SFX (as of 2025)

| Facility Name | Location | Commissioning Year | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) | Menlo Park, USA | 2009 (Upgraded to LCLS-II) | First hard XFEL; high repetition rate [20] [22] |

| SPring-8 Angstrom Compact FEL (SACLA) | Harima, Japan | 2011 | Compact design; high photon energy [20] [23] |

| European XFEL (EuXFEL) | Hamburg, Germany | 2017 | MHz repetition rate [20] [22] |

| Pohang Accelerator Lab XFEL (PAL-XFEL) | Pohang, South Korea | 2017 | High stability; NCI beamline for SFX [20] [24] |

| SwissFEL | Villigen, Switzerland | 2018 (planned) | High repetition rate [20] |

| SHINE | Shanghai, China | 2025 (scheduled) | Future high-repetition-rate source [22] |

Sample Delivery Methods

A reliable method for replenishing microcrystals at the interaction point with the XFEL beam is critical. The two principal approaches are injector-based and fixed-target methods [20].

Table: Common Sample Delivery Methods in SFX

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) [20] | Liquid crystal slurry focused by a sheath of gas. | Soluble proteins; standard samples. | Well-established; continuous flow. | High sample consumption (µL/min). |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion (HVE) / LCP Injector [20] [22] | Extrudes crystal-laden viscous media (e.g., Lipid Cubic Phase). | Membrane proteins; low sample consumption. | Very low flow rate (nL/min); ideal for LCP. | Clogging; requires precise pressure control. |

| Fixed Target [24] [22] | Crystals are deposited on a solid support (e.g., silicon chip, nylon loop) and raster-scanned. | Precious samples; low background. | Minimal sample waste; allows pre-characterization. | Lower data collection speed; crystal harvesting. |

Troubleshooting Common SFX Experimental Issues

FAQ: Our hit rate is very low. What could be the cause and how can we improve it? A low hit rate indicates that too few XFEL pulses are intersecting with a crystal. Solutions include:

- Check Crystal Density and Size: Use a high-performance microscope to ensure a high density of microcrystals of the correct size (1-10 µm). The crystal stream should appear turbid [23]. You can measure density using a cell counting plate [23].

- Optimize Injector Alignment: Precisely align the injector nozzle to ensure the crystal stream intersects the XFEL beam at the correct point. At PAL-XFEL, this is done using a reference laser and a microscope camera [24].

- Adjust Flow Rate: For injector-based methods, increase the flow rate to deliver more crystals, but be mindful of sample consumption [20].

- Monitor in Real-Time: Use monitoring software like OnDA to get immediate feedback on the hit rate and diffraction quality during data collection, allowing for rapid parameter adjustment [24].

FAQ: Our microcrystals are too large, too small, or heterogeneous in size. How can we produce more uniform microcrystals? Reproducible microcrystallization is a common bottleneck. The following protocol for hen egg-white lysozyme is a good starting point for optimization [23]:

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare 1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 3.0.

- Prepare crystallization solution: 28% (w/v) sodium chloride, 8% (w/v) PEG 6000, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 3.0.

- Prepare a 50 mg/mL solution of lysozyme in ultrapure water.

- Crystallization Procedure:

- Mix the lysozyme solution and crystallization solution in a 1:1 ratio.

- Incubate the mixture at a constant temperature (e.g., 17°C). Lower temperatures generally yield smaller crystals.

- Crystal formation is often instantaneous. The size can be controlled by varying the temperature and incubation time.

- For Challenging Targets: Use seeding techniques. A "rotational seeding" approach for copper-containing nitrite reductase has been shown to produce highly homogeneous microcrystals suitable for high-resolution SFX [23].

FAQ: Our data processing is slow, and we are struggling with indexing. What are the key considerations? SFX data processing is computationally intensive and requires specialized software.

- Use the Standard Pipeline: The typical workflow involves Cheetah (for hit-finding and preliminary processing) followed by CrystFEL (for indexing, integration, and merging) [25].

- Ensure Accurate Geometry: The detector geometry must be perfectly calibrated. Using a standard sample like lysozyme microcrystals for the first experiment is highly recommended to refine the detector geometry and data collection parameters [23].

- Indexing Challenges: If indexing rates are low, it may be due to crystal quality, diffraction resolution, or inaccuracies in the beam/detector parameters. Tools like XGANDALF can help with indexing difficult patterns [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful SFX experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SFX

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | A gel-like matrix that mimics the native membrane environment, used for growing and delivering membrane protein crystals [20] [22]. | Monolein-based lipids. |

| High-Viscosity Carriers | Media to suspend and deliver crystals while reducing flow rate and sample consumption. | Agarose [22], Hydroxyethyl cellulose [22], high-MW Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) [22]. |

| Crystallization Precipitants | Standard chemicals used to precipitate and crystallize proteins. | PEG 6000 [23], Sodium Chloride [23], Ammonium Sulfate. |

| Caged Compounds | Photolabile, inactive precursor molecules that release active substrates (e.g., neurotransmitters) upon a UV laser pulse, enabling time-resolved studies [23]. | Caged ATP, Caged NO. |

| Microcrystal Standards | Well-characterized proteins for beamline calibration, detector alignment, and protocol optimization. | Hen Egg-White Lysozyme [23] [16]. |

Advanced Applications: Time-Resolved SFX (TR-SFX)

How can I capture molecular movies of proteins in action? Time-Resolved SFX (TR-SFX) is the primary method for visualizing protein dynamics at near-atomic resolution and under ambient conditions [23]. The process involves initiating a reaction in microcrystals and then probing the structure at precise time delays.

There are two main triggering methods:

- Optical Pump-Probe: A laser ("pump") photoactivates the protein (e.g., by breaking a caged compound or exciting a photosensitive protein), and the XFEL pulse ("probe") collects a diffraction snapshot after a defined delay [23] [24]. This is ideal for light-sensitive proteins and can capture events on femtosecond to millisecond timescales.

- Mix-and-Inject Serial Crystallography (MISC): Microcrystals are mixed with a substrate just before being probed by the XFEL beam. This allows for the study of enzymatic reactions and ligand-binding events [22].

The workflow for a TR-SFX experiment, such as one studying a fungal nitric-oxide reductase with a caged NO compound, involves synchronizing a UV laser pulse with the XFEL pulse and the crystal stream to capture intermediate states [23].

This technical support center is designed for researchers embarking on serial microsecond crystallography (SµX) experiments at 4th generation synchrotron sources. SµX is a transformative technique that leverages the extreme brilliance of new synchrotron sources, like the ESRF-EBS, to determine macromolecular structures at room temperature with microsecond time resolution [26] [27]. This guide addresses the specific challenges of working with microcrystals—from sample preparation to data collection—providing troubleshooting and methodological support to ensure successful experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental advantage of SµX over traditional cryo-crystallography or serial millisecond crystallography (SMX)?

SµX enables the determination of macromolecular structures at room temperature under physiological conditions, which can reveal functionally relevant conformations that may be trapped or altered in cryo-cooled samples [26]. Compared to SMX at 3rd generation synchrotrons, the microsecond exposure time and vastly higher photon flux density (over 1,000 times higher than 3rd generation microfocus beamlines) minimize radiation damage and allow for time-resolved studies on a previously inaccessible time scale [26] [28] [27].

Q2: What types of scientific questions is SµX particularly suited to address?

SµX is ideally suited for:

- Time-resolved studies: Capturing molecular movies of biochemical reactions on the microsecond to second timescale [29].

- Membrane protein structural biology: Determining structures of challenging targets like G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in physiologically relevant states [26] [27].

- Drug discovery: Visualizing the binding modes of pharmaceutical compounds to their targets at high resolution, as demonstrated with the antagonist Istradefylline bound to the A2A adenosine receptor [27].

- Radiation-sensitive samples: Studying systems that are particularly prone to X-ray radiation damage, even at cryogenic temperatures [26].

Q3: What is the typical sample consumption for an SµX experiment?

A key benefit of SµX is its efficient sample usage. High-quality, complete datasets can be obtained from an exceptionally small amount of crystalline material, sometimes as little as a few microliters of crystal slurry [26] [28]. This is a significant advantage over some early XFEL serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) experiments, which could require large volumes of sample [30].

Q4: What are the primary sample delivery methods available for SµX?

The SµX beamline ID29 at ESRF supports a versatile sample environment, allowing users to choose the best method for their sample [26] [29]:

- Fixed Target: Crystals are deposited on solid supports like silicon chips or polymer foils. This method is sample-conserving and allows for raster scanning.

- High Viscosity Extruders (HVEs): Crystals are embedded in a viscous matrix (e.g., lipidic cubic phase) and extruded slowly through a nozzle into the X-ray beam. This is well-suited for membrane protein microcrystals [26].

Q5: How does data collection at a 4th generation synchrotron SµX beamline differ from an XFEL?

While both facilities enable room-temperature serial crystallography, SµX at a synchrotron uses mechanically chopped, microsecond-long X-ray pulses at a high repetition rate (e.g., 231.25 Hz at ID29) [26]. In contrast, XFELs provide femtosecond pulses in a "diffract-before-destroy" regime [30]. SµX provides a more accessible and potentially higher-throughput route for many time-resolved studies where femtosecond resolution is not necessary [28].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common SµX Experimental Issues

Table 1: Common SµX Experimental Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Low diffraction resolution, high background. | Inhomogeneous or poorly sized microcrystals. | Implement micro-seeding techniques. Combine crushing of large crystals with batch crystallization for uniform 3-5 µm crystals [31]. |

| Clogging in HVE injectors. | Crystal aggregates or too large crystals. | Filter crystal slurry through a fine mesh (e.g., 30 µm nylon mesh) to remove aggregates [31]. | |

| Sample Delivery | Low hit rate in fixed target. | Inconsistent crystal distribution on chip. | Optimize sample deposition and washing protocols to ensure a uniform, single layer of crystals. |

| Unstable jet in HVE. | Incorrect viscosity or temperature of the carrier medium. | Adjust the composition of the viscous matrix and ensure temperature stability to maintain a steady flow. | |

| Data Collection | Weak diffraction signals. | Crystals too small, beam misalignment. | Confirm beam focus and size. Use the on-line hit-finding software (e.g., NanoPeakCell/PyFAI) to adjust data collection parameters in real-time [26]. |

| Signs of radiation damage in structure. | Dose per crystal is too high. | Leverage the low-dose capability of SµX. Ensure the pulse duration and flux are optimized to outrun damage [26]. | |

| Data Processing | Low indexing rate. | Sparse diffraction patterns, incorrect unit cell. | Use software (e.g., cctbx.small_cell) designed for indexing sparse patterns from small unit cells [32]. Generate a synthetic powder pattern from all collected frames to determine the unit cell [32]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Preparing High-Quality Microcrystals via Micro-Seeding

This protocol, adapted from successful SFX work, is a robust method for generating the uniform microcrystals required for SµX [31].

- Grow Macrocrystals: First, cultivate large crystals of your target macromolecule using standard vapor-diffusion or batch methods.

- Prepare Seed Stock:

- Harvest several large crystals (total volume 5-15 mm³) and wash them in a stabilizing precipitant solution.

- Transfer the crystals to a new microtube with a fresh precipitant solution (crystal-to-buffer volume ratio of ~1:3).

- Crush the crystals thoroughly using an electric cell homogenizer or a similar mechanical crusher for about one minute to create a slurry.

- Store this seed stock at 4°C until use.

- Generate Microcrystals:

- In a 1.5 ml microtube, carefully mix:

- 10 µl of seed stock.

- 100 µl of concentrated protein solution (e.g., 200 mg/ml).

- 800 µl of precipitant solution.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature (e.g., ~26°C) for approximately 1 hour. This short, standing time promotes the rapid growth of uniform microcrystals.

- In a 1.5 ml microtube, carefully mix:

- Size Selection (Optional):

- To ensure crystal size uniformity and prevent injector clogging, filter the suspension through a nylon mesh with an appropriate pore size (e.g., 30 µm) via unforced sedimentation.

Standard Operating Procedure for SµX Data Collection on ID29

This procedure outlines the general workflow for a fixed-target experiment on the ID29 beamline [26] [29].

- Beamline Setup and Synchronization:

- Confirm the beamline is delivering a mechanically pulsed, slightly polychromatic beam (1% bandwidth) with a pulse duration of ~90 µs at a repetition rate of 231.25 Hz.

- Ensure the MD3upSSX diffractometer, the beam chopper, and the JUNGFRAU 4M detector are fully synchronized via the LImA2 data acquisition system.

- Sample Loading:

- Load the fixed target (e.g., a silicon chip pre-loaded with your microcrystals) onto the diffractometer.

- For HVE experiments, load the crystal-filled syringe into the injector and initiate a slow, stable flow.

- Data Collection:

- Use the MXCuBE-Web interface to define the raster scan pattern for the fixed target or to start the injector flow.

- The data acquisition system will automatically trigger the detector to collect one frame for every X-ray pulse that hits the sample.

- The on-line analysis pipeline (using a GPU-accelerated Peakfinder8 algorithm) will assess each frame in real-time, classifying it as a "hit" (contains diffraction patterns) or a "non-hit."

- Data Curation:

- Monitor the data collection progress. The software can be configured to discard "non-hit" frames to save storage space, while retaining all "hit" frames for subsequent processing and merging.

The logical flow of an SµX experiment, from sample to structure, is summarized in the diagram below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for SµX

| Item | Function in SµX Experiment | Key Details & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystals | The biological sample under investigation. | Ideal size is 1-10 µm. Quality and uniformity are critical for high-resolution data [26] [31]. |

| High Viscosity Extruder (HVE) | Delays crystal settling and facilitates slow, stable injection of crystal-laden matrix into the X-ray beam. | Essential for membrane proteins often crystallized in Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP). ID29 supports ASU, MPI, and SACLA-type HVEs [26] [29]. |

| Fixed Target Supports | Provides a solid substrate to hold microcrystals stationary for raster scanning by the beam. | Includes Silicon (Si) chips and SOS foils [26] [29]. Sample-conserving and allows for data collection from specific, pre-located crystals. |

| Viscous Carrier Media | A matrix to suspend microcrystals for HVE delivery or for loading onto fixed targets. | e.g., LCP for membrane proteins; various greases or high-viscosity polymers for soluble proteins. |

| Synchronized Detector | A high-speed, charge-integrating pixel detector to record diffraction patterns from microsecond pulses. | e.g., JUNGFRAU 4M detector used at ID29 [26] [29]. |

| Data Processing Suite | Software for on-the-fly hit finding, followed by offline indexing, integration, and merging of thousands of still patterns. | e.g., LImA2 with PyFAI/Peakfinder8 for online analysis; cctbx.xfel or similar suites for final structure determination [26] [32]. |

Technical Specifications of a 4th Generation SµX Beamline

The following table summarizes the performance parameters of a state-of-the-art SµX beamline, as exemplified by ID29 at the ESRF-EBS.

Table 3: Quantitative Technical Specifications of a SµX Beamline (ex. ID29 at ESRF-EBS) [26] [29]

| Parameter | Typical Specification | Importance for SµX |

|---|---|---|

| Photon Energy Range | 10 - 20 keV (tunable) | Provides flexibility for various experimental needs, including anomalous scattering. |

| Photon Flux | ~2 × 10¹⁵ photons/sec | The high flux enables very short exposure times and high signal-to-noise. |

| Beam Size at Sample | 4 × 2 µm² (focusable to ~1 µm²) | Matches the size of microcrystals, maximizing the signal and minimizing background. |

| Bandwidth (ΔE/E) | 1% | A "slightly pink" beam that increases flux and produces more full reflections per pattern, improving data quality with fewer images [26]. |

| Pulse Duration | 10 - 100 µs | The key to microsecond time-resolution and outrunning radiation damage. |

| Pulse Repetition Rate | Up to 925 Hz | Enables rapid data collection, completing a dataset of thousands of images in minutes. |

| Detector Type | JUNGFRAU 4M (charge-integrating) | A fast, low-noise detector capable of synchronizing with the microsecond pulse rate [26]. |

For researchers grappling with the challenge of microcrystals in X-ray crystallography, Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) emerges as a transformative solution. This cryo-TEM technique enables high-resolution structure determination from nanocrystals too small for conventional X-ray methods [33]. Where traditional crystallography requires large, high-quality single crystals (typically >10 μm), MicroED readily analyzes crystals smaller than 200 nanometers, effectively turning what was previously considered "failed" crystallization experiments into viable structural biology targets [33] [6] [34]. This capability is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research where growing large crystals often presents a major bottleneck in structure-based drug discovery [33] [35].

Table 1: Comparison of MicroED and Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD)

| Parameter | MicroED | SCXRD |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Size | 100 nm - 200 nm [33] [36] | ≥0.3 mm [34] |

| Sample Quantity | As little as 10-12 grams [33] | Significantly larger amounts required [34] |

| Radiation Source | Electron beam [33] [34] | X-rays [34] |

| Instrumentation | Cryo-TEM [33] [34] | X-ray diffractometer/Synchrotron [34] |

| Data Collection Time | Minutes [33] | Hours to days |

| Key Limitation | Dynamical scattering effects [34] | Requires large, high-quality crystals [34] |

The MicroED Workflow: From Nanocrystals to Atomic Structures

The MicroED workflow integrates principles from both cryo-EM and X-ray crystallography, enabling researchers to extract atomic-resolution information from nanocrystals [6]. The process begins with sample preparation and proceeds through data collection and processing, each stage requiring specific optimizations to ensure success.

Figure 1: MicroED Workflow from Sample Preparation to Structure Determination

Sample Preparation Methodologies

Proteinaceous Samples: For protein crystals, which typically require hydration to maintain their native state, samples are applied to glow-discharged EM grids, blotted to remove excess solution, and flash-frozen in liquid ethane [37] [6]. This vitrification process prevents crystalline ice formation that could damage the sample [33]. When crystals are too thick (>200 nm), cryo-focused ion beam (cryo-FIB) milling is employed to create thin lamellae suitable for analysis [33] [37].

Small Molecules and Natural Products: Small molecule crystals are often dry and can frequently be analyzed at room temperature [33] [37]. Mechanical grinding can reduce larger crystals to the appropriate size, or molecules can be crystallized spontaneously from solution using evaporation [33] [37].

Advanced Preparation Techniques: Recent methodological advances address key challenges in MicroED sample preparation. The Preassis (pressure-assisted) method enables more efficient removal of excess liquid from EM grids, particularly beneficial for samples with high viscosity or low crystal concentration [38]. This technique preserves up to two orders of magnitude more crystals on TEM grids compared to conventional blotting methods, significantly improving success rates for challenging samples [38].

Troubleshooting Common MicroED Experimental Challenges

Sample Preparation Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Ice Thickness Across Grid

- Cause: Conventional blotting methods struggle with viscous crystallization buffers containing PEG or lipid cubic phases [38].

- Solution: Implement the Preassis method which uses pressure-assisted liquid removal through the EM grid [38]. Optimize pressure settings and carbon hole size to control ice thickness [38].

- Alternative: For extremely viscous samples (e.g., LCP), consider direct crystallization on EM grids or specialized back-side blotting techniques [38].

Problem: Low Crystal Density on Grid

- Cause: Traditional blotting removes too many crystals during excess liquid removal [38].

- Solution: Use Preassis method which preserves significantly more crystals by pulling liquid through the grid rather than blotting from the surface [38]. This is particularly valuable for samples with limited crystal material.

- Preventative Measure: Identify microcrystals in crystallization drops using UV fluorescence, SONICC, or negative-stain EM when light microscopy is insufficient [6].

Problem: Crystal Damage During Preparation

- Cause: Shear forces during blotting or dehydration after grid preparation [39].

- Solution: Optimize blotting conditions and ensure rapid vitrification. For sensitive samples, consider cryo-FIB milling of larger crystals instead of attempting to grow nanocrystals directly [33] [37].

Data Collection Problems

Problem: Weak or No Diffraction

- Cause: Crystals too thick, resulting in multiple scattering; incorrect crystal orientation; or radiation damage [33] [40].

- Solution: Ensure crystal thickness <200 nm [33]. Use continuous rotation data collection with ultralow dose rates (<0.01 e⁻/Ų/s) [40]. Screen multiple crystals on the grid to find optimal diffraction candidates.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify crystal identity using imaging mode before diffraction

- Confirm adequate crystal thickness using cryo-FIB if necessary

- Optimize beam tilt and crystal orientation

- Ensure adequate cryo-cooling to minimize radiation damage

Problem: Dynamical Scattering Effects

- Cause: Strong multiple scattering in thicker crystal regions convolutes diffraction intensities [34].

- Solution: Collect data from the thinnest possible crystals (<200 nm) [33]. Use specialized algorithms for dynamical scattering correction during data processing [34].

- Advanced Approach: For particularly challenging cases, implement precession electron diffraction to minimize dynamical effects [41].

Problem: Rapid Radiation Damage

- Cause: Excessive electron dose rate during data collection [40].

- Solution: Implement low-dose techniques with total accumulated dose <9 e⁻/Ų [40]. Use modern direct electron detectors for improved sensitivity at low doses.

Data Processing Challenges

Problem: Poor Data Integration Statistics

- Cause: Inaccurate indexing, crystal movement during rotation, or excessive background scattering [39] [40].

- Solution: Use established X-ray crystallographic software packages (DIALS, XDS, MOSFLM) with appropriate modifications for electron scattering [33] [40]. Ensure proper conversion of diffraction movies to compatible formats [41].

- Optimization: Implement movie processing with frame-based alignment to correct for crystal movement during continuous rotation [6].

Problem: Incomplete Data Sets

- Cause: Limited crystal rotation range due to technical constraints or crystal geometry [33].

- Solution: Merge data from multiple crystals to improve completeness [33]. Optimize crystal size and shape to minimize shadowing at high tilt angles.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What crystal size is ideal for MicroED? A: MicroED works best with crystals between 100-200 nm in thickness [33]. Crystals larger than 200 nm suffer from increased multiple scattering which complicates data interpretation [33]. Crystals can be reduced to appropriate sizes through mechanical grinding, sonication, or cryo-FIB milling [33] [37].

Q: Can MicroED handle crystals grown in viscous conditions? A: Yes, though this presents specific challenges. Crystals grown in viscous buffers (e.g., with high PEG concentrations or in lipid cubic phase) can be prepared using specialized methods like Preassis, which efficiently removes viscous liquids that conventional blotting struggles with [38].

Q: How does radiation damage compare between MicroED and X-ray crystallography? A: MicroED uses extremely low electron dose rates (<0.01 e⁻/Ų/s) that enable collection of up to 90° of rotation data from a single crystal with total dose <9 e⁻/Ų [40]. Proper cryo-cooling is essential to mitigate damage in both techniques.

Q: What resolution can I expect from MicroED? A: MicroED typically achieves resolutions between 1.0-3.2 Å, with most structures better than 2.5 Å resolution [40]. Numerous structures have been determined at atomic resolution (1.0-1.5 Å) [40] [6].

Q: Can I use MicroED for small molecule structure determination? A: Yes, MicroED is particularly powerful for small molecules and natural products where only nanogram quantities are available [33] [6]. Small molecules often can be analyzed at room temperature without cryo-cooling [33] [37].

Q: How long does data collection take for a complete MicroED dataset? A: Data collection is remarkably fast, typically taking only a few minutes per crystal [33]. Complete datasets can be collected in as little as 1-3 minutes using continuous rotation methods [38].

Q: What software is used for MicroED data processing? A: MicroED data can be processed using established X-ray crystallographic software including DIALS, XDS, MOSFLM, and HKL [33] [40]. Structure determination and refinement proceed using programs such as Phenix, Refmac, and SHELX with modifications for electron scattering factors [40].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MicroED

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MicroED Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-EM Grids | Support for nanocrystals during data collection [37] | Holey carbon grids; grid type affects ice thickness consistency [38] |

| Cryo-Protectants | Prevent crystalline ice formation during vitrification [33] | Particularly important for protein crystals with high solvent content [40] |

| Vitrification System | Rapid freezing of samples to preserve native structure [37] | Thermo Scientific Vitrobot or equivalent; critical for sample preservation [37] |

| Cryo-FIB System | Thinning of thicker crystals to optimal dimensions [33] [37] | Essential for crystals >200 nm; creates thin lamellae for analysis [33] |

| Polyethylene Glycol | Common crystallization agent producing volume exclusion [38] | High concentrations create viscosity challenges during sample preparation [38] |

| Liquid Ethane | Cryogen for rapid vitrification [37] [38] | Supercooled ethane used for flash-freezing hydrated samples [37] |

MicroED represents a significant advancement in structural biology, particularly for researchers struggling with microcrystals that defy conventional X-ray crystallography. By leveraging the strong interaction between electrons and matter, this technique extracts high-resolution structural information from crystals that are one-billionth the volume of those required for traditional X-ray diffraction [6]. As sample preparation methods continue to improve and accessibility to cryo-TEM facilities expands, MicroED is poised to become an indispensable tool in the structural biologist's arsenal, especially in pharmaceutical research where rapid structure determination of drug targets and complexes is essential. The technique's ability to work with nanocrystals, minimal sample requirements, and compatibility with standard crystallographic software make it particularly valuable for advancing research on challenging biological targets that have resisted traditional structural approaches.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a fixed-target sample delivery approach? The key advantage of fixed-target systems is their high sample efficiency. Since microcrystals are loaded directly onto a solid support which is then rastered through the X-ray beam, virtually every crystal loaded can be used for data collection. This approach also allows for precise control in time-resolved experiments and enables multi-shot experiments to characterize X-ray beam effects on the sample [42] [43].

FAQ 2: How does the 'diffraction-before-destruction' principle work at XFELs? At X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs), ultra-bright femtosecond X-ray pulses are used to obtain a diffraction pattern from a microcrystal before the destructive effects of radiation damage manifest. This approach requires a new crystal to be supplied for each pulse, as the exposed crystal is destroyed after the pulse passes through it [44] [3].

FAQ 3: My microcrystals are settling in the syringe, leading to inconsistent delivery. How can I prevent this? Crystal settling and clogging are common issues in liquid injection. Strategies to address this include:

- Using a high-viscosity carrier matrix, such as lipidic cubic phase (LCP), which is particularly beneficial for membrane proteins [44].

- Adding compounds like sucrose to adjust the density of the carrier solution to achieve neutral buoyancy for the crystals [44].

- Employing gentle, continuous agitation or mixing systems for the sample reservoir to maintain a homogeneous suspension.

FAQ 4: What is the typical sample consumption for a complete dataset in serial crystallography? Sample consumption varies significantly depending on the delivery method. Early serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) experiments required several grams of protein. However, with advanced methods like optimized fixed-targets and low-flow liquid injectors, consumption has been reduced to the microgram range. The theoretical minimum for a complete dataset (requiring ~10,000 indexed patterns from 4 µm microcrystals) is estimated to be around 450 ng of protein [3].

FAQ 5: When should I consider using a hybrid delivery method like acoustic droplet ejection? Hybrid methods are particularly useful for time-resolved studies that require precise, rapid mixing of substrates with protein crystals (Mix-and-Inject Serial Crystallography, or MISC). They combine the precise timing and low sample consumption of fixed-target methods with the rapid mixing capabilities of liquid injectors [3] [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Hit Rate in Liquid Injection Experiments

A low hit rate (percentage of X-ray pulses that result in a diffraction pattern) leads to excessive sample waste.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect crystal concentration | Check sample under microscope; analyze hit rate from initial data. | Adjust concentration to ~10⁹ crystals/mL. Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) to monitor monodispersity [46] [44]. |

| Jet instability or mismatch with beam | Visually inspect jet using microscope camera; correlate jet flow with pulse rate. | For GDVNs, optimize gas/liquid pressure. Consider viscosity modifiers (e.g., glycerol). For high-rep-rate sources, match flow rate to X-ray pulse frequency [44]. |

| Nozzle clogging | Check for sudden pressure increase or flow stoppage. | Pre-filter mother liquor and sample. Use nozzles with larger orifices or GDVNs that focus flow to avoid clogging [44]. |

Issue 2: High Background Scattering in Fixed-Target Experiments

Excessive background noise can obscure weak diffraction patterns from microcrystals.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete removal of excess mother liquor | Inspect chip under microscope for large, shimmering liquid pools. | Optimize blotting conditions (time, force). Use wicking tools or specialized blotting pads [43]. |

| Scattering from the support membrane itself | Collect a diffraction pattern from an empty area of the membrane. | Use thinner or low-scattering materials (e.g., silicon nitride, graphene) [43]. |

| Crystal dehydration on the chip | Monitor diffraction resolution degradation over time. | Perform data collection in a controlled humidity environment. Use sealed chips or covers to prevent evaporation [46] [43]. |

Issue 3: Inefficient Sample Usage in Fixed-Target Setup

You cannot collect enough diffraction patterns from a loaded chip.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-uniform crystal distribution | Take a low-magnification overview image of the chip after loading. | Improve sample application technique (e.g., use a spreader). Consider acoustic droplet ejection for precise, picoliter-volume dispensing [3] [45]. |