Molecular Replacement Phasing: From AlphaFold Revolution to Advanced Structure Solution

This comprehensive article explores molecular replacement (MR) phasing, a cornerstone technique in macromolecular crystallography.

Molecular Replacement Phasing: From AlphaFold Revolution to Advanced Structure Solution

Abstract

This comprehensive article explores molecular replacement (MR) phasing, a cornerstone technique in macromolecular crystallography. It covers foundational principles, from solving the crystallographic phase problem using Patterson maps and the rotation/translation search to modern methodologies revolutionized by accurate AlphaFold2 predictions. The guide details practical workflows within software suites like Phenix and CCP4, addresses troubleshooting for challenging cases with low sequence identity or conformational changes, and emphasizes critical validation to mitigate model bias. Aimed at structural biologists and drug discovery scientists, this resource synthesizes traditional knowledge with cutting-edge advances, demonstrating how MR continues to enable the determination of biologically and therapeutically relevant structures.

Solving the Phase Problem: The Foundational Principles of Molecular Replacement

X-ray crystallography is a pivotal method for determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of molecules, having directly contributed to numerous Nobel prizes [1]. The fundamental process involves a crystal scattering an incident X-ray beam in specific directions, creating a diffraction pattern. The intensity of each reflection, or Bragg spot, in this pattern is proportional to the square of the structure factor amplitude, |FH| [1]. The central challenge, known as the crystallographic phase problem, arises because the experimental measurements capture these intensities but lose the associated phase information for each structure factor (FH = |FH|exp(iφH)) [1].

The electron density ρ(r) within the crystal unit cell is calculated via a Fourier synthesis, which requires both the amplitude and phase for each structure factor: ρ(r) ∝ ΣH FH e−i2πH·r. Without the phases (φH), it is impossible to correctly reconstruct the electron density map and, consequently, determine the atomic positions [1]. This is analogous to trying to reconstruct a complex sound wave knowing only the volumes of its constituent frequencies but not their relative timing. The critical nature of phases is visually summarized in the diagram below.

Core Principles and Quantitative Impact of Phases

The phase of a structure factor determines the relative positioning of the corresponding wave in the Fourier synthesis. Even with perfectly measured amplitudes, an incorrect phase assignment can drastically alter the resulting electron density, leading to a misinterpretation of the atomic structure [1]. The following table quantifies the relationship between data quality, the success of phasing techniques, and the resulting model accuracy.

Table 1: Key Parameters and Success Metrics in Crystallographic Phasing

| Parameter / Method | Typical Value / Requirement | Impact on Structure Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model Accuracy for MR | < 1.5 Å Cα RMSD over large fraction [2] | Enables successful molecular replacement; lower accuracy often leads to failure. |

| Sulfur Content for S-SAD | > 0.25% at λ = 5.02 Å [3] | Higher native sulfur content increases the anomalous signal for phasing without labelling. |

| Reflections/Anomalous Scatterer Ratio | > 1000 for successful S-SAD [3] | A higher ratio improves the chances of successful ab initio phasing. |

| Data Resolution for Multipole Model | d ≤ 0.50 Å recommended [4] | Enables accurate experimental electron density determination and hydrogen atom positioning. |

| GDT-HA Improvement after Refinement | 0.22 to 0.64 (de novo example) [2] | Measures significant backbone improvement in predicted models, making them usable for MR. |

Methodologies for Solving the Phase Problem

Overcoming the phase problem is a prerequisite for structure determination. Several experimental and computational methods have been developed to recover this lost information.

Molecular Replacement (MR)

Molecular Replacement (MR) is a primary phasing technique used when a structurally similar model (a "search model") is available. The method involves positioning this known model within the unit cell of the unknown target crystal. The principle is to find the correct rotational and translational orientation of the search model that best explains the observed diffraction pattern [5] [1]. From this correctly positioned model, initial phases can be calculated to generate an electron density map for the target structure [5].

MR is inherently a six-dimensional search problem (three rotational and three translational parameters). To make it computationally tractable, the search is typically divided into two consecutive three-dimensional searches: a rotation search followed by a translation search [5] [1]. The correctness of an MR solution is ultimately validated by a significant decrease in crystallographic R-factors during subsequent model refinement [5]. The workflow below outlines the key steps in an MR experiment.

Experimental Phasing: Anomalous Dispersion

Experimental phasing methods rely on collecting diffraction data from crystals that contain specific atoms, known as anomalous scatterers. The most common technique is Single-wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD). In a SAD experiment, data is collected at a single X-ray wavelength near the absorption edge of the anomalous scatterer (e.g., selenium in selenomethionine, or native sulfur) [3] [1]. Atoms like sulfur have an anomalous scattering factor (f") that increases at longer wavelengths, enhancing the measurable signal. This technique is particularly powerful for "native-SAD," which uses atoms naturally present in the macromolecule (such as sulfur in methionine and cysteine), eliminating the need for chemical derivatization [3].

Using very long wavelengths (e.g., λ = 2.75 Å to 5.9 Å) is highly beneficial for native-SAD as it significantly boosts the anomalous signal from light atoms like sulfur, phosphorus, chlorine, potassium, and calcium [3]. Specialized beamlines, such as I23 at Diamond Light Source, operate in a vacuum to minimize air absorption and scattering at these long wavelengths, making such experiments routine [3].

Emerging Computational and AI-Based Methods

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) are providing powerful new avenues for solving the phase problem. The AI-based phase-seeding (AI-PhaSeed) method uses a neural network to generate initial phase estimates for a small subset of reflections from the experimental amplitudes [6]. These AI-derived "seed" phases are then extended and refined to the full set of reflections using iterative algorithms in software like SIR2024 [6].

Going a step further, end-to-end deep learning models like XDXD aim to bypass the traditional phasing and map interpretation steps entirely. This diffusion-based generative model is conditioned on the low-resolution diffraction data and directly generates a complete, chemically plausible atomic model, demonstrating a 70.4% match rate for structures with data limited to 2.0 Å resolution [7].

Advanced Refinement Protocols

Once initial phases are obtained, the resulting model must be refined against the experimental data. Moving beyond the standard Independent Atom Model (IAM) can dramatically improve accuracy, especially for hydrogen atoms and bonding information.

Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR) Protocol

Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR) is a quantum crystallographic technique that uses aspherical atomic form factors derived from quantum chemical calculations, leading to a more accurate description of electron density, particularly for hydrogen atoms [8] [4].

Protocol for HAR (e.g., using Tonto software):

- Initial IAM Refinement: Refine the structure against the diffraction data using the standard spherical independent atom model to obtain starting atomic coordinates and displacement parameters [8].

- Quantum Chemical Calculation: Use the IAM-refined structure to perform a quantum chemical calculation (e.g., DFT) to obtain the molecular wavefunction and electron density.

- Hirshfeld Partitioning: Partition the molecular electron density into aspherical atomic basins using the Hirshfeld formalism [4].

- Form Factor Calculation: Calculate aspherical atomic form factors for each atom via Fourier transform of their Hirshfeld electron density.

- Crystallographic Refinement: Refine the structure model (atomic coordinates and displacement parameters) against the diffraction data using the new aspherical form factors.

- Iteration: Iterate steps 2 through 5 until convergence is achieved, i.e., the structure and electron density no longer change significantly [4].

All-Atom Rebuilding-and-Refinement Protocol

For improving models derived from sources like NMR or computational prediction, an energy-based rebuilding-and-refinement protocol can be used to achieve the accuracy required for molecular replacement.

Protocol for All-Atom Rebuilding-and-Refinement:

- Identify Problem Regions: Analyze the initial model to identify regions with high conformational strain, poor rotamer statistics, or bad steric clashes [2].

- Stochastic Rebuilding: Rebuild the identified problematic segments (e.g., loops or side chains) by sampling alternative conformations in a stochastic manner.

- All-Atom Refinement: Refine the entire rebuilt structure in a physically realistic all-atom force field to relax the model and minimize its energy [2].

- Validation and Iteration: Validate the refined model using geometric and energetic criteria. Multiple independent rebuilding-and-refinement trials can be run, with the lowest-energy models selected for further analysis [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Crystallographic Phasing Experiments

| Item | Function in Phasing |

|---|---|

| Selenomethionine | Biosynthetically incorporated into proteins to provide strong anomalous scatterers (Se atoms) for SAD/MAD phasing [1]. |

| Heavy Atom Soaks | Compounds containing atoms like Hg, Au, or Pt used to derivatize crystals for isomorphous replacement phasing [1]. |

| Native Crystals | Crystals of the unmodified target used for molecular replacement or native-SAD phasing utilizing inherent S, P, or other atoms [3]. |

| Long-Wavelength Beamline | A synchrotron beamline (e.g., I23 at Diamond) capable of using X-rays >2 Å wavelength to enhance anomalous signal from light atoms [3]. |

| Cryoprotectant | A chemical (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) used to protect crystals from ice formation during cryo-cooling for data collection. |

| HAR/Quantum Software | Software packages like Tonto that implement Hirshfeld Atom Refinement or other quantum crystallographic methods for accurate refinement [8] [4]. |

| MR Search Model | A structurally homologous model from the PDB or an in silico predicted structure used as a starting point for molecular replacement [5] [2]. |

Molecular replacement (MR) is a fundamental phasing method in crystallography that uses the known three-dimensional structure of a related molecule to determine the crystal structure of an unknown target. This technique is the method of choice when a suitable search model is available, as it requires no additional experimental procedures beyond the diffraction data collection, thereby simplifying and accelerating the structure determination process [9]. The core principle hinges on placing a known molecular structure within the unit cell of an unknown crystal to derive initial phases, which are then used to calculate electron density maps for model building and refinement [5].

MR has become indispensable in structural biology, particularly for determining macromolecular structures such as proteins. Its utility has been further amplified in the modern era by the availability of predicted protein structures from AI tools like AlphaFold, which can serve as search models for experimentally determined crystal structures [3]. This application note details the theoretical underpinnings, practical protocols, and key applications of MR, providing researchers with a comprehensive guide to implementing this powerful technique.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

The Phase Problem in Crystallography

The fundamental challenge in X-ray crystallography, known as the "phase problem," arises because experimental diffraction measurements capture only the intensities (amplitudes) of scattered X-rays, while the phase information—crucial for reconstructing the electron density map—is lost [10]. Molecular replacement overcomes this by leveraging prior structural knowledge.

The Molecular Replacement Principle

MR solves the phase problem by using a previously solved, structurally similar model (the "search model") to approximate the unknown structure's phases. The procedure involves two core mathematical operations [9]:

- Rotation Function (RF): Determines the correct orientation of the search model within the unit cell of the unknown crystal by rotating the model to maximize the correlation between its calculated diffraction pattern and the experimental data.

- Translation Function (TF): Once correctly oriented, the model is translated to its correct position within the unit cell, again by maximizing the correlation with observed diffraction data.

Following successful rotation and translation, the positioned model provides initial phase estimates, enabling the calculation of an initial electron density map. This map is then used for subsequent model building and refinement to obtain the final atomic structure of the target [5].

Molecular Replacement Workflow

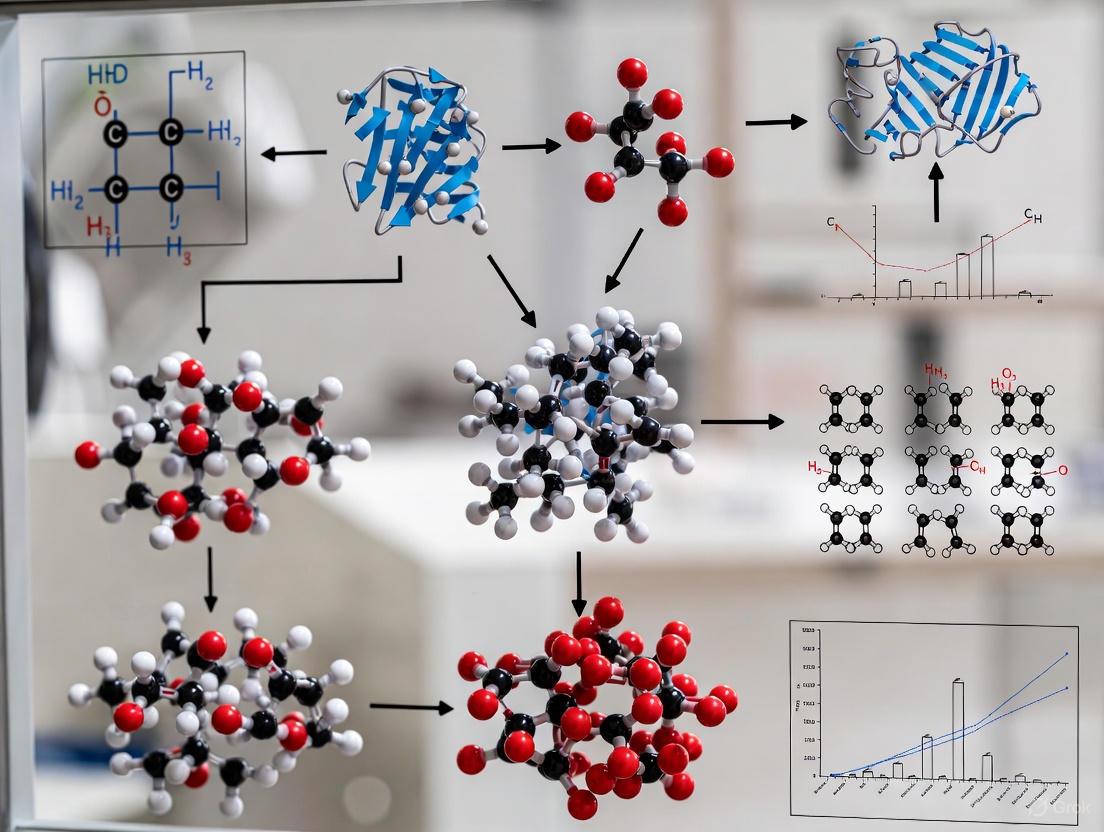

A successful MR experiment follows a logical sequence from data and model preparation to structure solution. The flowchart below visualizes this multi-step workflow and decision-making process.

Figure 1: Molecular Replacement Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps in a standard MR experiment, from data and model preparation to final structure solution. Critical decision points, such as evaluating the MR solution, are highlighted.

Workflow Breakdown and Protocols

1. Data Preparation Protocol

- Objective: Prepare a high-quality dataset of structure factor amplitudes (

Fobs) from the crystallographic experiment. - Procedure:

- Integrate diffraction images to obtain a merged, scaled dataset.

- The data file (e.g., MTZ format) must contain

Fobsand associated uncertainties (SIGFobs). R-free flags are not required for the MR search itself [9]. - Critical Note: Accurate low-resolution data (<4 Å) is crucial for MR success, as it dominates the rotation and translation functions [5].

2. Search Model Preparation Protocol

- Objective: Identify and prepare a suitable structural model for use in the MR search.

- Procedure:

- Model Sourcing: Search the Protein Data Bank (PDB) using the target sequence (e.g., via BLAST) or generate a structure using AlphaFold2 [3].

- Model Quality Assessment: The success of MR is highly dependent on the similarity between the search model and the target structure. Table 1 provides guidelines based on sequence identity [9].

- Model Editing:

- Remove non-conserved residues, especially long flexible loops or side chains.

- Delete heteroatoms (waters, ligands, ions) from the search model.

- For low-similarity cases, use tools like

Sculptorto trim non-conserved atoms and improve model performance [9]. - For structures with conformational flexibility, consider splitting into independent domains or creating an ensemble of models.

Table 1: MR Success Guidelines vs. Search Model Similarity

| Sequence Identity | Expected RMSD | MR Success Likelihood | Required Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 40% | < 1.5 Å | Usually easy | Minimal model preparation needed. |

| 30-40% | ~1.5-2.0 Å | Possible, can be difficult | Careful model preparation recommended. |

| 20-30% | ~2.0-2.5 Å | Difficult | Extensive model preparation (e.g., with Sculptor) is crucial. |

| < 20% | > 2.5 Å | Very unlikely in most cases | Consider alternative phasing methods. |

3. Running Molecular Replacement Protocol

- Objective: Correctly place the search model in the unit cell of the target structure.

- Software: This protocol uses

PHASERwithin thePHENIXsuite [9]. - Procedure:

- Inputs: Provide the reflection file (

Fobs) and the prepared search model (PDB file). Specify the composition of the crystal's asymmetric unit (e.g., via a sequence file or molecular weight). - Execution: The process is typically automated (

MR_AUTOmode):- Anisotropy Correction: PHASER scales reflections to correct for anisotropy.

- Rotation Function: Identifies the model's orientation.

- Translation Function: Determines the model's position within the unit cell.

- Packing Analysis: Filters solutions with severe steric clashes.

- Rigid-Body Refinement & Phasing: Performs a quick refinement of the placed model and calculates initial phases.

- Resolution: Using data to 2.5 Å resolution is standard. For difficult cases, limiting the resolution (e.g., to 3.5-4.0 Å) can sometimes improve results and speed up computation [9].

- Inputs: Provide the reflection file (

4. Evaluating MR Solution and Subsequent Steps Protocol

- Objective: Validate the MR solution and proceed with model building.

- Procedure:

- Validation Metrics: Check the Phaser log file for key statistics. A solution is considered successful if the Translation Function Z-score (TFZ) is above 8 and the Log-Likelihood Gain (LLG) is significantly positive [9].

- Initial Map Calculation: Use the output MTZ file from Phaser, which contains experimental amplitudes and initial model-based phases, to compute an initial electron density map.

- Model Building and Refinement:

- Load the MR solution and the initial map into a model-building program (e.g.,

Coot). - Adjust the model to fit the electron density: correct side chains, rebuild loops, and add/remove residues as needed.

- Identify and build missing parts, such as ligands or the dockerin module in a cohesin-dockerin complex [5].

- Add solvent molecules (water) based on positive peaks in the

mFobs - DFcalcdifference map. - Perform iterative cycles of refinement (e.g., with

phenix.refine) and manual model adjustment [5].

- Load the MR solution and the initial map into a model-building program (e.g.,

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Software and Resources for Molecular Replacement

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Reference/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHASER | Software | Primary MR engine for rotation/translation searches using maximum likelihood methods. | [9] |

| Phenix | Software Suite | Integrated platform providing GUI for PHASER, refinement (phenix.refine), and model building tools. | [9] |

| Sculptor | Software Utility | Prepares search models by pruning non-conserved residues to improve MR success with distant homologs. | [9] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures used to find homologous search models. | [5] |

| AlphaFold | Database/Model | Provides AI-predicted protein structures that can serve as search models when no experimental structure exists. | [3] |

| Coot | Software | For model building, inspection, and adjustment into electron density maps after MR. | [5] |

Applications and Synergies in Drug Discovery

Molecular replacement plays a critical role in modern drug discovery by enabling rapid structure determination of therapeutic targets and their complexes with drug candidates.

Facilitating Target Identification and Drug Repurposing

In silico target prediction methods are crucial for understanding polypharmacology—how drugs interact with multiple targets—which can explain side effects or reveal new therapeutic uses. A 2025 benchmark study evaluated seven target prediction methods (including MolTarPred and RF-QSAR) using a shared dataset of FDA-approved drugs [11]. These methods often rely on known 3D structures of targets. For example, MolTarPred successfully predicted new targets for existing drugs: it identified hMAPK14 as a target of mebendazole and Carbonic Anhydrase II (CAII) as a new target of Actarit, suggesting repurposing opportunities for cancer and other diseases [11]. Determining the structures of these novel drug-target complexes often relies on MR, using existing structures of the target proteins as search models.

Empowering AI-Driven Molecular Innovation

The field of AI-powered molecular innovation is growing rapidly, with the AI-native drug discovery market projected to reach $1.7 billion in 2025 [12]. AI tools like AlphaFold2 have revolutionized structural biology by providing highly accurate predicted protein structures. These predictions are exceptionally powerful when combined with MR. As noted in a 2023 study, AlphaFold predictions have been successfully used as search models for molecular replacement, solving structures that were previously intractable [3]. This synergy between AI prediction and experimental phasing significantly accelerates the validation of novel drug targets and the structure-based design of new molecules, compressing discovery timelines and reducing costs [12].

Molecular replacement (MR) is a primary method for solving the crystallographic phase problem when a structurally similar model is available. By leveraging a known molecular model, MR enables the determination of crystal structures without the need for additional experimental phasing. The method currently contributes to solving up to 70% of deposited macromolecular structures in macromolecular crystallography [13]. Patterson-based molecular replacement utilizes the Patterson function, a mathematical construct derived directly from measured diffraction intensities, to determine the correct orientation and position of a search model within a crystal's unit cell. This application note provides a detailed protocol for implementing Patterson-based MR, focusing on the critical rotation and translation functions, and is framed within broader research on molecular replacement phasing techniques.

Theoretical Foundation

The Molecular Replacement Problem

Molecular replacement is fundamentally a six-dimensional search problem. The goal is to find the correct orientation (defined by three rotation angles) and position (defined by three translation vectors) for a search model within the crystallographic unit cell of the target structure [14]. The transformation of model coordinates (x) to target coordinates (x') is described by:

x' = R x + T

where R is a 3x3 rotation matrix and T is a translation vector [14]. An exhaustive six-dimensional search is computationally prohibitive; for a typical unit cell sampled at coarse intervals, the search space can exceed 3×10⁹ points [14]. Therefore, MR implementations typically employ a "divide and conquer" strategy, separating the problem into two sequential three-dimensional searches: the rotation function (RFn) followed by the translation function (TFn) [13] [14].

The Patterson Function

The Patterson function, P(u), is central to traditional MR methods. It is calculated as the Fourier transform of the squared structure factor amplitudes (|F|²) with phases set to zero [13] [15]:

P(u) = ∫ ρ(x) ρ(x+u) dx

where ρ(x) is the electron density at position x and u is a vector in Patterson space [14]. The function represents a map of all interatomic vectors within the crystal structure, with the following key properties [14]:

- Contains N² peaks for N atoms in the unit cell (N at the origin, N(N-1) elsewhere)

- Inherently centrosymmetric

- Contains all the symmetry of the original unit cell

- Intramolecular vectors rotate with the molecule but are independent of its position

Table 1: Key Properties of the Patterson Function

| Property | Mathematical Description | Implication for MR |

|---|---|---|

| Origin Peak | P(0) = ∫ ρ²(x) dx | Large peak at origin from atoms mapping to themselves |

| Vector Density | N² total peaks | Becomes extremely dense for macromolecules |

| Symmetry | P(u) = P(-u) | Inherent centrosymmetry simplifies calculations |

| Self-Vectors | Vectors within a molecule | Rotation-informative; form a sphere around the origin |

Patterson-Based Rotation Function

Principles and Implementation

The rotation function (RFn) identifies the correct orientation of the search model by comparing the observed Patterson function (from experimental data) with a model Patterson function (calculated from the search model) [14]. The comparison is performed by rotating the model Patterson relative to the observed Patterson and computing their overlap within a spherical integration volume around the origin. This spherical region is crucial as it primarily contains self-vectors—interatomic vectors within the same molecule—which are independent of the molecule's position in the unit cell [13] [14].

The mathematical formulation of the Crowther rotation function is [14]:

RFn = ∫ Pₒᵦₛ(u) × Pₘₒ𝒹(R u) du

where the integration is over a spherical volume U around the origin.

Practical Protocol for Rotation Function

Model Preparation: Select a search model with high structural similarity to the target. Improve model quality by removing flexible loops, truncating divergent side chains to alanine, and adjusting B-factors to reflect expected mobility [13].

Data Preparation: Ensure experimental data is complete, merged, and properly scaled. Check for anisotropy and other pathologies that might affect the Patterson function.

Parameter Selection:

- Angular Sampling: Determine appropriate angular sampling intervals. A typical initial sampling interval is 2.5°, requiring evaluation of ~0.9-1.5×10⁶ orientations [13].

- Integration Radius: Set the spherical integration radius to encompass most intramolecular vectors while excluding intermolecular vectors. A radius of 20-40 Å is often appropriate.

Execution: Run the rotation search using standardized software. The output is a list of potential orientations ranked by a correlation coefficient or similar metric.

Analysis: Identify promising rotation solutions. Typically, the top 5-50 solutions are selected for subsequent translation searches [13].

Table 2: Rotation Function Search Parameters and Software

| Parameter | Typical Values | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Angular Sampling | 1.0° - 3.0° | Finer sampling increases computation time proportionally |

| Integration Radius | 20 - 40 Å | Should encompass most intramolecular vectors |

| Angle Convention | Eulerian, Polar | Varies by program; be consistent |

| Symmetry | Crystal symmetry | Proper space group definition is critical |

| Software Options | AMORE, Molrep, Phaser, CNS | Different programs may use different algorithms |

Diagram 1: Workflow for the rotation function in molecular replacement, showing the sequence from model preparation to selection of top solutions for translation search.

Patterson-Based Translation Function

Principles and Implementation

Once the correct orientation is identified, the translation function determines the molecular position within the crystallographic unit cell. While intramolecular vectors were used in the rotation function, the translation function utilizes both intramolecular and intermolecular vectors [14]. The correct translation is found by comparing the observed Patterson function with the Patterson function calculated for the correctly oriented model placed at different positions in the unit cell [14].

The translation function can be evaluated in both Patterson space and reciprocal space. In Patterson space, the search involves computing the correlation between the observed Patterson and the Patterson of the positioned model as it is translated through the unit cell [14].

Practical Protocol for Translation Function

Input Preparation: Use the top rotation solutions (typically 5-50) from the rotation function as input.

Search Space Definition: Determine the translation search space. For a typical unit cell of 100×100×100 Å, a 1 Å sampling interval requires testing 10⁶ positions per orientation [13]. The search can often be limited to the Cheshire cell, a region of the unit cell defined by crystallographic symmetry where unique solutions can be found [13].

Execution: For each candidate orientation, perform a three-dimensional translation search. The model is systematically moved through the search space, and at each position, the agreement between observed and calculated Patterson functions is evaluated.

Scoring and Selection: Solutions are ranked using a correlation coefficient or R-factor. The combination of orientation and position that gives the best agreement (lowest R-factor or highest correlation) is selected as the correct MR solution.

Table 3: Translation Function Search Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Values | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Translation Sampling | 0.5 - 2.0 Å | Finer sampling increases computation time cubically |

| Search Volume | Cheshire cell or full asymmetric unit | Cheshire cell reduces search space significantly |

| Symmetry | Proper space group definition | Critical for defining intermolecular vectors |

| Scoring Functions | Correlation coefficient, R-factor | Higher correlation or lower R-factor indicates better solution |

Diagram 2: Workflow for the translation function in molecular replacement, showing the process from input of rotation solutions to identification of the final molecular replacement solution.

Advanced Strategies and Troubleshooting

Model Improvement Strategies

The success of Patterson-based MR heavily depends on the quality of the search model. When sequence identity between model and target is low (<30%), consider these enhancement strategies [13]:

- Domain Splitting: For multi-domain proteins with potential hinge motions, split the model into rigid domains and search for each domain separately [13]

- Ensemble Modeling: Use multiple models simultaneously to create an ensemble that better represents the target structure [13]

- Normal Mode Refinement: Generate alternative conformations along low-frequency normal modes to account for conformational flexibility [13]

Patterson Correlation Refinement

A powerful advanced strategy involves "Patterson refinement" of a large number of the highest peaks from the rotation function [16]. This method uses the correlation coefficient between squared amplitudes of observed and calculated normalized structure factors as a target function. If the root-mean-square difference between the search model and crystal structure is within the radius of convergence, the correct orientation can be identified by having the lowest target function value after refinement [16]. This approach can solve structures that cannot be solved by conventional MR or even full six-dimensional searches [16].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- No Clear Solution: If neither rotation nor translation functions yield a clear solution, the model may be too dissimilar from the target. Consider alternative models or model-building approaches.

- Good Rotation but Poor Translation: This may indicate a correct orientation but issues with crystal packing. Check for steric clashes in predicted positions.

- Weak Signals: For marginal cases, try increasing the number of rotation solutions carried into translation search, or use finer sampling in both searches.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Patterson-Based Molecular Replacement

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Sources/Software |

|---|---|---|

| Search Model | Provides initial phase information | PDB database, predicted structures (AlphaFold, AWSEM-Suite) |

| MR Software | Performs rotation and translation searches | CCP4 suite (Molrep, Phaser, AMoRe), CNS, PHENIX |

| Crystallographic Data | Experimental diffraction intensities | X-ray diffraction, electron diffraction datasets |

| Sequence Alignment | Identifies potential search models | BLAST, Clustal Omega, structural alignment tools |

| Model Preparation | Optimizes search model | Chain truncation, side chain pruning, B-factor adjustment |

| Visualization | Analyzes results and models | Coot, PyMOL, ChimeraX |

Patterson-based molecular replacement remains a cornerstone of modern crystallography, providing an efficient path to structure solution when suitable search models are available. The separation of the six-dimensional search into sequential rotation and translation functions makes the problem computationally tractable while maintaining robustness. Success depends critically on both the quality of the search model and the proper implementation of the Patterson-based algorithms described in this protocol. As structural databases continue to expand and computational methods advance, Patterson-based MR will maintain its essential role in enabling structure-based drug discovery and mechanistic studies of macromolecular function.

Molecular replacement (MR) has become the predominant method for solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography, accounting for approximately 74% of all crystallographic protein structures in the Protein Data Bank [17]. The success of MR hinges critically on the availability and quality of search models—known structural templates used to derive initial phase estimates. The MR process exploits the fundamental principle that proteins with similar sequences or folds often share significant structural homology, enabling the use of previously solved structures or computationally predicted models to phase new crystal structures. The key challenge in MR lies in finding an appropriate search model that closely matches the unknown target structure, a process governed primarily by three critical parameters: sequence identity, structural homology, and Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD).

The revolutionary advancement in protein structure prediction, particularly through deep learning methods like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3, has dramatically expanded the universe of potential search models. Recent studies indicate that nearly 97% of structures deposited in the PDB since AlphaFold's introduction can be solved through molecular replacement using AlphaFold Database models or AlphaFold-derived predictions [18]. This transformation has made MR applicable to previously intractable targets, though the effective use of these models still requires careful consideration of their quality metrics and appropriate adaptation to specific crystallographic challenges.

Quantitative Metrics for Search Model Evaluation

Sequence Identity and Homology

Sequence identity represents the percentage of identical amino acids between the search model and target sequence when optimally aligned. This metric has traditionally served as the primary indicator for selecting appropriate MR templates. The relationship between sequence identity and MR success probability follows a well-established correlation, with generally higher success rates observed when sequence identity exceeds 30% [19]. However, the emergence of accurate structure prediction tools has somewhat altered this paradigm, as models with lower sequence identity but high predicted confidence can now successfully phase targets.

Structural homology extends beyond simple sequence identity to encompass evolutionary relationships and conserved structural features. Even with limited sequence similarity, proteins may share significant structural homology that enables successful MR. The integration of multiple member databases in resources like InterPro, which consolidates signatures from CATH-Gene3D, CDD, Pfam, and other databases, provides a powerful framework for identifying distant homologies and functional domains that can inform search model selection [20].

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

RMSD quantifies the average distance between equivalent atoms in superimposed structures, providing a direct measure of structural similarity between search model and target. Lower RMSD values indicate higher structural conservation and typically correlate with improved MR success. For search models, the backbone RMSD is particularly informative as it reflects conservation of the protein fold independent of side-chain variations. Modern MR workflows often employ automated pruning of mismatched side-chains to improve the search model, as implemented in tools like Molrep within the CCP4 Cloud simple-MR workflow [18].

Confidence Metrics from Predicted Models

For AI-predicted structures, additional confidence metrics have become crucial for evaluating MR suitability. The predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) from AlphaFold provides residue-level confidence scores that can guide model preparation. In practice, low-confidence regions (pLDDT < 70) are often pruned before MR, as they frequently correspond to flexible loops or disordered regions that may hinder solution [18]. The conversion of pLDDT values to B-factor estimates allows proper weighting of model information during phasing. Benchmark studies demonstrate that careful handling of these confidence metrics can significantly improve MR success rates even for challenging targets.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Search Model Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Optimal Range for MR | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity | Percentage of identical residues in alignment | >30% (traditional), lower with AF2 | Higher values indicate better conservation |

| Global RMSD | Backbone atom deviation after superposition | <2.0 Å for reliable MR | Lower values indicate structural conservation |

| pLDDT | AlphaFold confidence score | >70 for retained regions | Higher values indicate more reliable predictions |

| TM-score | Template modeling score measuring structural similarity | >0.5 indicates same fold | More robust to local variations than RMSD |

Performance Benchmarks of Search Model Types

Experimental Structures as Search Models

Experimentally determined structures from the PDB have traditionally served as the gold standard for MR search models. Their key advantage lies in the inclusion of experimentally validated structural features, including side-chain conformations, loop structures, and domain arrangements. The effectiveness of experimental structures as search models depends strongly on the evolutionary distance between the template and target proteins, with closer homologs generally providing better solutions. For cases with high sequence identity (>70%), nearly exact structural matches enable highly efficient MR pipelines like the Dimple molecular replacement workflow in CCP4 Cloud, which minimizes computational overhead by leveraging perfect homology [18].

The MoRDa database curates structural domains specifically optimized for molecular replacement, providing another valuable resource of experimental templates. In automated workflows like CCP4 Cloud's auto-MR, MoRDa serves as a fallback option when initial PDB searches fail, demonstrating the continued importance of carefully processed experimental structures even in the age of AI prediction [18].

Computationally Predicted Models

The revolution in protein structure prediction has dramatically expanded the MR toolkit, with AlphaFold models now enabling MR for previously unsolvable targets. Benchmark studies demonstrate that AlphaFold2 can generate MR models with a success rate of approximately 90% [17], making it a reliable option for most single-chain proteins. The recent development of DeepSCFold specifically addresses the challenge of protein complex prediction, showing 11.6% and 10.3% improvement in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively on CASP15 multimer targets [21]. For particularly challenging cases like antibody-antigen complexes, DeepSCFold enhances the prediction success rate for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively [21].

Other prediction tools including RoseTTAFold, trRosetta, and ESMFold have also demonstrated utility for MR, though with generally lower success rates than AlphaFold for most targets [17]. The performance comparison between different prediction methods highlights the importance of selecting the appropriate tool based on the specific target characteristics, with multimeric complexes benefiting from specialized approaches like DeepSCFold.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Search Model Sources

| Model Source | Success Rate | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental (PDB) | Varies with homology | Experimentally validated details | Limited by available homologs |

| AlphaFold2 | ~90% [17] | Broad coverage, high accuracy | Lower accuracy for complexes |

| AlphaFold3 | High for single chains | Improved interface prediction | Restricted access |

| DeepSCFold | Superior for complexes [21] | Specialized for protein interactions | Newer, less validated |

| RoseTTAFold | Good for single chains | Fast, open source | Lower accuracy than AlphaFold |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Replacement

Protocol 1: Automated MR with AlphaFold Models

The af-MR workflow in CCP4 Cloud provides a standardized protocol for leveraging AlphaFold predictions in molecular replacement [18]:

Input Preparation: Collect merged or unmerged reflection data, macromolecular sequence, and optional ligand description. For unmerged data, use Aimless for scaling and merging, then estimate asymmetric unit content.

Model Generation: Submit the target sequence to Colabfold for AlphaFold2 structure prediction. This generates multiple models with associated pLDDT confidence metrics.

Model Preparation: Process the predicted model using Slice to prune low-confidence regions (typically pLDDT < 70). Convert residue pLDDT values to B-factor estimates for proper weighting during phasing.

Molecular Replacement: Perform MR with Phaser using the processed model. The confidence-based B-factor weighting helps prioritize well-predicted regions.

Structure Completion: After successful phasing, proceed with automated model building using Modelcraft to correct sequence mismatches and refine the structure.

Ligand and Solvent Fitting: If ligand information was provided, generate ligand structures and fit into density using Coot. Add water molecules using FindWaters utility.

Iterative Refinement: Conduct multiple rounds of refinement using protocols from the auto-REL workflow until structure quality metrics are satisfactory.

This workflow successfully phases the majority of single-domain protein structures, with studies showing that appropriately edited AlphaFold models can solve 92% of structures originally determined using single-wavelength anomalous diffraction [17].

Protocol 2: Sequence-Independent MR for Unknown Targets

For cases where the target sequence is unknown, such as crystallized contaminants, a database-driven approach enables identification and phasing simultaneously [22]:

Data Collection: Collect and process diffraction data using standard pipelines (DIALS, CCP4). Determine space group and unit cell parameters.

Database Selection: Download relevant predicted structure databases, such as the AlphaFold proteome for E. coli (4363 structures) for bacterial expression contaminants [22]. Filter out models with fewer than 50 residues.

High-Throughput MR Screening: Set up automated molecular replacement using MOLREP with each database structure as a search model. Use high-resolution cut-off at 3.0 Å to speed up search. Disable pack and score functions initially.

Solution Identification: Monitor translation function Z-scores (TFZ) and correlation coefficients (CC) to identify correct solutions. Typically, TFZ > 8 and CC > 30% indicate successful phasing.

Model Validation: Examine the phased electron density map for quality and connectivity. Build initial model and check for consistency.

Target Identification: Use the successful search model to identify the unknown protein through sequence and structural similarity searches.

This approach was successfully used to identify and solve structures of E. coli contaminants YncE and YadF without prior sequence information, demonstrating the power of comprehensive structure databases for challenging crystallographic problems [22].

Protocol 3: Genetic Algorithm-Enhanced Direct Phasing

For cases where search model-based methods fail, genetic algorithm-enhanced direct methods provide an alternative approach that requires no structural templates [19]:

Initialization: Initialize MPI with 100 parallel ranks, each generating random electron density as initial population.

Dual-Space Iteration: Perform standard iterative projection algorithm cycles, applying constraints in both real and reciprocal space.

Genetic Operations: Every 100 iterations, perform population-level optimization:

- Selection: Choose parent densities based on fitness (phase agreement)

- Crossover: Exchange density regions between parents

- Mutation: Introduce random modifications to maintain diversity

Elite Preservation: Maintain best-performing solutions unchanged across generations.

Convergence Monitoring: Track overall phase error and continue until convergence below 40°.

This method has demonstrated significant improvements, increasing success rates from below 30% to nearly 100% for test cases with 1.35-2.5 Å resolution [19]. The approach is particularly valuable for novel folds lacking structural homologs or accurate predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Resources for Molecular Replacement

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCP4 Cloud | Software Suite | Integrated MR workflows with automation | https://cloud.ccp4.ac.uk [18] |

| AlphaFold DB | Structure Database | Predicted models for proteomes | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk [22] |

| MoRDa | MR-Optimized Database | Curated structural domains for MR | Integrated in CCP4 [18] |

| ColabFold | Prediction Server | Rapid AlphaFold predictions | https://colabfold.com [18] |

| BeStSel | Validation Tool | Secondary structure analysis from CD | https://bestsel.elu.te.hu [23] |

| InterPro | Classification Resource | Protein family and domain annotation | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro [20] |

Workflow Visualization

Molecular Replacement Decision Workflow: This diagram outlines the key decision points in selecting and preparing search models for molecular replacement, highlighting alternative pathways for different scenarios.

The critical role of search models in molecular replacement continues to evolve with advancements in both experimental structural biology and computational prediction methods. The metrics of sequence identity, structural homology, and RMSD remain fundamental for evaluating model suitability, though their interpretation has become more nuanced with the availability of AI-predicted structures. The development of specialized tools like DeepSCFold for protein complexes and genetic algorithm-enhanced direct methods for novel folds demonstrates the ongoing innovation in this field.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multiple information sources, combining evolutionary constraints from deep multiple sequence alignments with physical principles from molecular dynamics. The rapid growth of the AlphaFold Database and its integration with resources like InterPro provides an increasingly comprehensive foundation for addressing previously intractable crystallographic challenges. As these tools become more accessible through platforms like CCP4 Cloud, the success rate for molecular replacement will continue to improve, expanding the frontiers of structural biology and drug discovery.

For the practicing structural biologist, the current landscape offers an unprecedented array of tools for molecular replacement, but requires careful attention to model quality metrics and appropriate method selection based on the specific target characteristics. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a robust starting point for leveraging these advances in practical crystallographic workflows.

Historical Context and Evolution of MR as a Primary Phasing Method

Molecular replacement (MR) has revolutionized the field of structural biology by providing a computational method to solve the crystallographic phase problem. The technique utilizes the known three-dimensional structure of a related molecule to determine the initial phases for a new crystal structure, enabling the calculation of electron density maps. MR is now the predominant method for solving macromolecular structures, accounting for approximately 70% of deposited structures in the Protein Data Bank [13]. This application note traces the historical development of MR, outlines its fundamental principles, and provides detailed protocols for its successful implementation in modern structural biology research and drug development.

The core principle of MR relies on positioning a known search model within the unit cell of the unknown target structure through rotation and translation operations. Once correctly positioned, this model provides initial phase estimates, which are combined with the observed structure factor amplitudes to compute an initial electron density map. This map then serves as the foundation for iterative model building and refinement to arrive at the final atomic structure [13] [24].

Historical Development

Theoretical Foundations and Early Challenges

The conceptual framework for molecular replacement was established in the early 1960s, primarily through the work of Michael Rossmann and David Blow. Their seminal 1962 paper introduced the rotation function as a method to determine the relative orientation of identical molecules within a crystal lattice [25]. This development emerged from the significant challenges posed by traditional heavy-atom isomorphous replacement methods, which required the preparation of high-quality derivatives and often proved problematic for many proteins.

The early theoretical objections to MR were substantial. Frances Crick and Max Perutz raised serious concerns about both the translation problem and the phase problem. Crick pointed out that the translation required to superimpose two identical objects after rotation would depend on the position of the axis of rotation, questioning whether a unique solution existed at all. Regarding phase determination, Crick argued that even with knowledge of the molecular transform's magnitude at every point in space, the structure still could not be definitively determined due to the absence of discontinuities in the general non-centric case [25]. These objections were so compelling that Rossmann noted, "I found myself working alone for some time" on developing the method [25].

Key Theoretical Breakthroughs

The molecular replacement method evolved through several key theoretical advancements:

- Rotation and Translation Functions: The separation of the placement problem into sequential rotation and translation searches made the computational challenge tractable [25] [13]. The rotation function identifies the correct orientation by comparing Patterson maps from the model and target, focusing on intramolecular vectors near the origin that are translationally invariant.

- Non-Crystallographic Symmetry (NCS): The recognition that symmetry relationships between molecules within the same asymmetric unit (proper NCS) or between different crystal forms (improper NCS) could be leveraged for phase determination was fundamental to early MR applications [25].

- Patterson-Based Approaches: Patterson map interpretation provided the mathematical foundation for early MR implementations, using vector comparison methods to overcome the phase problem [13] [24].

Table 1: Historical Milestones in Molecular Replacement Development

| Time Period | Key Development | Primary Contributors |

|---|---|---|

| 1960-1962 | Formulation of rotation function concept | Rossmann & Blow |

| 1962-1970 | Application to insulin structure; translation function development | Rossmann, Blow, Crowther |

| 1972 | "Molecular Replacement" book published, coining the term | Rossmann |

| 1980s-1990s | Patterson-based automated search algorithms | Various researchers |

| 1990s-2000s | Maximum-likelihood scoring functions | Read, Bricogne, others |

| 2000s-Present | Integration with structure prediction and advanced model preparation | Various groups |

Theoretical Principles

Fundamental Crystallographic Equations

The mathematical foundation of MR rests on standard crystallographic principles. The structure-factor equation describes how each observed reflection contains information about the position and thermal motion of every atom in the structure:

Where F(hkl) and φ(hkl) represent the structure-factor amplitude and phase, respectively, for reflection hkl; xj denotes the position of atom j; and gj(S) = fj(S)Tj(S) accounts for both the atomic form factor and thermal motion correction [26].

The corresponding electron-density equation is used to compute the electron density at discrete points throughout the unit cell:

When phases are accurate, this equation produces peaks in the density corresponding to atomic positions [26].

The Patterson Function and Molecular Replacement

Patterson maps play a crucial role in traditional MR methods. A Patterson function is calculated by replacing F(hkl) with |F(hkl)|² and setting all phases to zero, producing a map with peaks at all interatomic vector positions (xi - xj) rather than at atomic positions themselves. This vector map contains a large peak at the origin where vectors relating atoms to themselves accumulate [26] [24].

In MR, the Patterson function enables the separation of rotation and translation searches. The rotation function compares the Patterson map from the observed data with Patterson maps calculated from the search model in different orientations. The region near the origin, dominated by intramolecular vectors, is used for this comparison as these vectors are largely independent of the molecular position in the unit cell [13].

Maximum Likelihood Formulation

Modern MR implementations have largely transitioned from Patterson-based to maximum-likelihood scoring functions. This statistical approach evaluates the probability of observing the measured structure factors given a proposed placement of the model. Maximum likelihood methods better account for errors in the search model and experimental data, and naturally handle the problem of unknown translations during rotation searches by statistically averaging over all possible positions [13].

Figure 1: The molecular replacement workflow, showing the sequential steps from initial data and model preparation through to final structure refinement.

Practical Implementation

Model Selection and Preparation

The success of MR is critically dependent on selecting and preparing an appropriate search model. Key considerations include:

- Sequence Identity: Generally, >25-30% sequence identity with the target structure is required for successful MR, with Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values preferably <2.0 Å [27].

- Completeness: The model should represent as much of the target structure as possible, though sometimes omitting variable regions can reduce noise and improve signal.

- Model Improvement: Before MR, models can be improved by:

Data Quality Assessment

Before attempting MR, the quality and properties of the diffraction data must be thoroughly assessed:

- Completeness and Resolution: Data should be as complete as possible, with higher resolution (<3Å) greatly facilitating subsequent model building [26].

- Anisotropy and Twinning: Anisotropic diffraction may require truncation, while twinning can complicate space group determination but doesn't necessarily prevent MR success [26].

- Space Group Determination: The correct space group must be determined from systematic absences and diffraction symmetry, though this can be complicated by non-crystallographic symmetry elements [26].

Molecular Replacement Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Molecular Replacement with Phaser

Objective: To determine the position and orientation of a search model in the target unit cell using maximum-likelihood methods.

Materials:

- Processed diffraction data (MTZ format)

- Search model(s) (PDB format)

- Sequence of target macromolecule

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Convert processed diffraction data to MTZ format if necessary

- Analyze data quality with Xtriage (Phenix) or similar tools

- Verify space group assignment

Model Preparation:

- Identify potential search models using sequence databases (HHpred, PHMMER)

- Improve models with Sculptor or similar tools by trimming flexible regions

- For multi-domain proteins with suspected conformational changes, split into domains

Content Estimation:

- Calculate Matthews coefficient to estimate molecules per asymmetric unit

- Use Matthews coefficient and sequence information to determine likely copy number

Rotation Search:

- Define search parameters (resolution range, angular sampling)

- Perform three-dimensional rotation search

- Retain top solutions (typically 10-50) based on rotation function Z-score

Translation Search:

- For each promising rotation solution, perform translation search

- Evaluate solutions using translation function Z-score and log-likelihood gain

Solution Validation:

- Check packing of placed molecules for clashes

- Verify physical plausibility of solution

- Calculate initial phases and examine electron density map quality

Troubleshooting:

- If no solution is found, try alternative search models or ensembles

- For multi-domain proteins, search for domains separately

- Verify space group assignment if solutions are physically implausible [13] [27]

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Molecular Replacement

| Software | Primary Function | Key Features | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phaser | MR with maximum-likelihood scoring | Robust rotation/translation search; ensemble handling | Phenix/CCP4 |

| Molrep | Automated molecular replacement | Patterson and maximum-likelihood options | CCP4 |

| Sculptor | Model preparation | Sequence-based pruning; B-factor optimization | CCP4 |

| MR-Rosetta | Model improvement after MR | Rosetta-based refinement of MR solutions | Phenix |

| Phenix.MRage | Automated MR pipeline | High-level automation for difficult cases | Phenix |

Advanced Applications

Protocol 2: Multi-Domain Molecular Replacement

Objective: To solve structures where conformational changes have occurred between domains.

Rationale: When domains have moved relative to each other, using the complete structure as a search model often fails. Searching for domains separately increases the probability of success.

Procedure:

- Identify domain boundaries in the search model through visual inspection or automated tools

- Separate the structure into individual domain models

- Perform MR with the most conserved domain first

- Fix the positioned domain and search for subsequent domains

- Alternatively, perform a six-dimensional search allowing all domains to move independently

Applications: Particularly useful for proteins with hinge motions or flexible arrangements of domains [13] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Molecular Replacement

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Search Tools | HHpred, PHMMER | Identify homologous structures for use as search models |

| Model Preparation | Sculptor, Molrep | Improve search models by trimming variable regions |

| MR Software | Phaser, Molrep | Perform rotation and translation searches |

| Model Building | Coot, Phenix.AutoBuild | Rebuild and refine structures after MR |

| Validation | MolProbity, PDB-REDO | Validate geometry and overall model quality |

| Structure Prediction | Rosetta, I-TASSER | Generate de novo models when no homologs exist |

| Databases | Protein Data Bank | Source of search models and validation comparisons |

Figure 2: Scoring functions in molecular replacement, showing the relationship between Patterson-based and maximum-likelihood approaches and their components.

Current Trends and Future Directions

The field of molecular replacement continues to evolve with several emerging trends:

- Integration with Structure Prediction: The improving accuracy of de novo protein structure prediction, particularly through deep learning methods like AlphaFold, is revolutionizing MR by providing high-quality search models even in the absence of close homologs [24].

- Advanced Search Algorithms: Six-dimensional searches that simultaneously optimize rotation and translation parameters are becoming more feasible with increased computational power [13].

- Automated Pipelines: Tools like Phenix.MRage are making MR increasingly accessible to non-specialists by automating the end-to-end process [27].

- Hybrid Methods: Combining MR with experimental phasing methods can help overcome model bias and resolve challenging cases.

The historical development of MR from a theoretically contested idea to the dominant phasing method in macromolecular crystallography demonstrates how computational advances can transform scientific practice. As structural biology continues to tackle increasingly complex biological systems, MR will undoubtedly remain an essential tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand structure-function relationships at the atomic level.

Modern MR Workflows: From Model Preparation to Automated Structure Solution

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for solving the phase problem in X-ray crystallography, accounting for approximately 80% of structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank [28]. Its success critically depends on the availability and quality of search models, which are often derived from structures homologous to the target protein. However, a significant challenge persists: for roughly 41% of protein families, no member with a known structure exists [28]. This application note details a robust protocol for selecting and preparing molecular replacement models using three integrated tools: HHpred for template identification, Sculptor for model improvement, and Ensembler for creating composite models. This structured approach is particularly valuable when sequence identity to available templates is low (typically 20-40%), a range where MR is often difficult but possible with careful model preparation [9] [29]. Properly executing this pipeline extends the lower bound of sequence similarity required for successful structure determination, enabling phasing for targets previously considered intractable.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table catalogues the key computational tools and resources required for effective model selection and preparation.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Replacement Model Preparation

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Protocol | Critical Features/Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| HHpred | Web Server / Software | Identifies remote homologs and generates alignments using hidden Markov models (HMMs) [28]. | Sensitive detection of distant relationships, provides multiple sequence alignments, and tertiary structure templates. |

| Sculptor | Command-Line / GUI Program | Improves MR model quality by pruning unreliable regions based on sequence alignment [30] [31]. | Main-chain deletion, side-chain pruning, B-factor modification using sequence similarity calculations. |

| Ensembler | Command-Line / GUI Program | Superposes multiple homologous structures and creates a single, improved ensemble model [29]. | Structural alignment of multiple PDB files, optional trimming of variable loops to a conserved core. |

| PHENIX/Phaser | Software Suite | Performs the molecular replacement search using maximum likelihood methods [9] [29]. | Automated MR (MR_AUTO), likelihood-enhanced rotation/translation functions, packing analysis. |

| PDB Format File | Data Resource | Provides the initial 3D atomic coordinates of the template structure(s). | Standardized format for representing macromolecular structures; requires removal of heteroatoms (ligands, water) before MR [9]. |

| Sequence File (FASTA) | Data Resource | Contains the amino acid sequence of the target structure to be solved. | Used for homology searches in HHpred and to guide model editing in Sculptor. |

The entire process of model selection and preparation, from initial sequence search to a refined model ready for molecular replacement, is summarized in the following workflow diagram.

Diagram 1: Overall workflow for model preparation and molecular replacement.

Protocol 1: Remote Homology Detection with HHpred

Purpose: To identify suitable template structures for molecular replacement by detecting remote homologs with significant structural similarity to the target, even in low sequence-identity regimes.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Provide the amino acid sequence of your target protein in FASTA format.

- Database Search: Execute an HHpred search against structural databases (e.g., PDB). HHpred uses hidden Markov models for highly sensitive profile-profile comparisons, which are superior to standard BLAST for detecting distant homology [28].

- Template Selection: Analyze the results. Suitable templates typically have HHpred probabilities above 20-30% and an expected RMSD of less than 2.5 Å from the target. Above 1.5 Å is preferable [29]. Prioritize templates with higher probability and coverage.

- Alignment Extraction: Download the resulting multiple sequence alignment, which will be used to guide subsequent model editing in Sculptor.

Protocol 2: Single-Model Improvement with Sculptor

Purpose: To enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of a single template structure by removing or modifying residues that are likely to differ from the target structure, thereby increasing the probability of a successful molecular replacement solution.

Methodology:

- Input Files:

- Structure: The template PDB file from HHpred.

- Alignment: The alignment file generated by HHpred, linking the template and target sequences.

- Preprocessing: Sculptor automatically selects a subset of the input structure and sanitizes occupancies and alternate conformations [30].

- Main-chain Deletion: Residues are deleted based on the sequence alignment. The

completeness_based_similarityalgorithm is recommended, as it deletes the same number of residues as a simple gap-based deletion but targets those with the lowest sequence similarity first, leading to better performance over a wide range of sequence identities [30]. - Side-chain Pruning: Sidechains are truncated based on sequence similarity. The

schwarzenbacheralgorithm is a robust default, which truncates a sidechain to Cγ (or other defined level) when aligned with a non-identical residue [30] [31]. - B-factor Modification: Atomic B-factors can be replaced with values predicted from sequence similarity or accessible surface area. This down-weights potentially flexible or error-prone regions during the MR search [30] [31].

- Output: A modified PDB file that is smaller and better matches the expected electron density of the target.

Table 2: Key Sculptor Algorithms and Recommended Application

| Processing Stage | Available Algorithms | Recommended Algorithm & Rationale | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main-chain Deletion | gap, threshold_based_similarity, completeness_based_similarity |

completeness_based_similarity: More robust than threshold-based methods; defaults are valid over a larger sequence similarity range [30]. |

Averaging window size, scoring matrix (e.g., BLOSUM62). |

| Side-chain Pruning | schwarzenbacher, similarity |

schwarzenbacher: A well-established, reliable method that truncates sidechains based on residue identity [30] [31]. |

pruning_level (e.g., 3 for Cγ). |

| B-factor Prediction | original, asa, similarity |

similarity or combination: Assigns higher B-factors (lower weight in MR) to low-similarity regions, which are expected to be more dissimilar [30]. |

factor, minimum. |

Protocol 3: Ensemble Creation with Ensembler

Purpose: To generate a single, superior search model by combining multiple, structurally aligned homologous models into an ensemble. This averages out errors in individual models and highlights the conserved core, which is most likely to be correct.

Methodology:

- Input: Multiple PDB files of homologous structures identified via HHpred. All models must be for the same protein or domain.

- Structural Alignment: Run Ensembler to automatically superpose all input models into a common frame of reference.

- Trimming (Optional but Recommended): Use the trimming option to remove loops and regions that deviate significantly among the ensemble members. This produces a model of the conserved core, which often has a higher effective accuracy than any single model [29] [32].

- Output: A single PDB file containing multiple

MODELrecords, which can be used directly in Phaser as an ensemble search model.

Data Presentation and Performance Benchmarking

The effectiveness of model preparation is quantified by its impact on molecular replacement success rates, particularly for difficult cases with low sequence identity. The following table synthesizes key performance insights from benchmarking studies.

Table 3: Impact of Model Preparation on Molecular Replacement Success

| Scenario | Sequence Identity to Target | Recommended Preparation | Expected Outcome & Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy MR | >40% | Often minimal preparation needed. | MR usually straightforward. High TFZ score (>8) and positive LLG expected [9] [29]. |

| Difficult MR | 20-40% | Essential. Use Sculptor and/or Ensembler. | Success rate significantly improved. TFZ scores of 6-8 are "possible" to "probable" [33]. |

| Remote Homology | <20-30% | Required. HHpred, Sculptor, and Ensembler combined. | MR unlikely without preparation. May enable solution; LLG > 120 provides high confidence [28] [33]. |

| Flexible Protein | Any | Split into domains; prepare each with Sculptor. | Searching individual domains gives a clearer signal than the whole protein [32]. |

Benchmarking against established techniques shows that models prepared with Sculptor compare favorably, especially when the alignment is unreliable [31]. Carrying out multiple trials using alternative models created from the same structure but using different Sculptor parameters can further improve the success rate [31]. For the most challenging cases below 20% sequence identity, integrating ab initio structure predictions from tools like AWSEM-Suite or AlphaFold2 has dramatically expanded the scope of molecular replacement, acting as de novo phasing methods [34] [35].

Integrated Procedure for a Challenging Case

The logical flow of data and decisions when integrating all three tools for a low-identity target is depicted below.

Diagram 2: Detailed protocol for integrating HHpred, Sculptor, and Ensembler on a target with low-sequence-identity templates.

For a target with sequence identity to available templates in the 20-30% range, the following integrated procedure is recommended:

- Identification: Use HHpred to find three or more template structures with the highest possible probability scores, even if sequence identity is low (e.g., 15-25%).

- Individual Preparation: Process each identified template PDB file individually using Sculptor. Use the

completeness_based_similarityalgorithm for main-chain deletion and theschwarzenbacheralgorithm for side-chain pruning, guided by the alignments from HHpred. - Ensemble Creation: Input all Sculptor-improved models into Ensembler. Superpose them and use the trimming option to produce a final ensemble model comprising only the conserved structural core.

- Molecular Replacement: Use the resulting ensemble in Phaser. When defining the ensemble in Phaser, do not claim 100% sequence identity. The sequence identity should reflect that of the original templates, as it is used to estimate the RMSD between the model and target [32].

This protocol systematically leverages the strengths of each tool—HHpred for sensitivity, Sculptor for precision editing, and Ensembler for signal averaging—to transform a set of weak templates into a powerful model for structure solution.

Molecular replacement (MR) is the predominant method for determining initial phases in macromolecular crystallography when a structurally related model is available. As a computational phasing technique, MR leverages prior structural knowledge to solve the crystallographic phase problem, thereby bypassing the need for additional experimental data collection. The Phaser software, integrated within the Phenix suite, implements maximum-likelihood molecular replacement methods that have significantly increased the success rate for difficult cases [36]. The procedure hinges on the correct placement of a search model within the crystallographic unit cell, a process divided into two fundamental steps: a rotation function (RF) to determine orientation, followed by a translation function (TF) to determine absolute position [29]. This application note details the core components of the Phaser-MR workflow, with a focused examination of the integrated procedures for anisotropy correction, translational non-crystallographic symmetry (tNCS) analysis, and packing analysis, which are critical for achieving successful structure solution.

The automated molecular replacement procedure in Phaser is a multi-stage process. The following diagram illustrates the sequential and integrated steps involved in solving a structure, from data input to a phased model.

The Molecular Replacement Problem

MR is fundamentally a six-dimensional search problem, where the coordinates of the target structure (x') are derived from the search model (x) via a transformation comprising a rotation matrix (R) and a translation vector (T): x' = Rx + T [14]. Due to the immense computational cost of a full six-dimensional search, the problem is divided into two separate three-dimensional searches: the rotation function and the translation function [14]. The success of MR is primarily governed by the quality of the search model, which can be roughly predicted by sequence identity to the target, as outlined in Table 1 [29].

Table 1: Relationship Between Search Model Quality and MR Success Likelihood

| Sequence Identity | RMSD (Å) | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| > 40% | < 1.5 | Usually straightforward |

| 30 - 40% | ~1.5 - 2.0 | Possible, but can be difficult |

| 20 - 30% | ~2.0 - 2.5 | Usually difficult, requires careful model preparation |

| < 20% | > 2.5 | Unlikely to work without advanced methods (e.g., MR-Rosetta) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

A successful molecular replacement experiment requires the preparation and integration of several key data components and software tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MR

| Item | Function/Description | Critical File Format(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Data | Reflection data (amplitudes or intensities) from the target crystal. A single file containing experimental data with sigmas is required. | MTZ, SCALEPACK, CNS |

| Search Model(s) | Known structure(s) related to the target, used for phasing. Can be a single PDB file or an ensemble of superposed models. | PDB (with MODEL records for ensembles) |

| Sequence File | Defines the sequence and molecular weight of the macromolecule in the crystal, used to estimate the asymmetric unit contents. | FASTA |

| Phenix Software Suite | A comprehensive system for automated macromolecular structure solution. | - |

| Phaser | The primary program within Phenix for performing maximum-likelihood molecular replacement. | - |

| Sculptor | Phenix utility for pruning and improving search models based on sequence alignment. | - |

| Ensembler | Phenix utility for superposing multiple homologous models to create a single search ensemble. | - |

| Coot | Molecular graphics tool for model building and validation, often used after MR. | - |

Detailed Protocols for Core MR Procedures

Anisotropy Correction

4.1.1 Purpose and Theory Diffraction data can exhibit anisotropy, where the fall-off of diffraction intensity is directionally dependent in reciprocal space. This means the effective resolution of the dataset is not uniform in all directions. If uncorrected, anisotropy can severely degrade the signal in molecular replacement searches. Phaser's integrated anisotropy correction scales reflections to overcome this directional weakness before proceeding with the rotation and translation functions [29].

4.1.2 Protocol and Implementation