Multi-Center Validation of Lipidomic Biomarkers: From Discovery to Clinical Application

The integration of lipidomics with machine learning is revolutionizing non-invasive diagnostic biomarker discovery for a wide range of diseases, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and congenital conditions.

Multi-Center Validation of Lipidomic Biomarkers: From Discovery to Clinical Application

Abstract

The integration of lipidomics with machine learning is revolutionizing non-invasive diagnostic biomarker discovery for a wide range of diseases, including cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and congenital conditions. This article provides a comprehensive framework for the development and rigorous multi-center validation of lipidomic biomarkers, a critical step for clinical translation. We explore foundational concepts in lipid metabolism and its dysregulation in disease, detail methodological workflows combining untargeted and targeted lipidomics with advanced data analytics, address key challenges in model optimization and reproducibility, and finally, present robust validation strategies across diverse, independent cohorts. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends, highlighting how validated lipidomic signatures are paving the way for more accurate, early-stage disease detection and personalized medicine approaches.

The Basis of Lipidomic Biomarkers: Linking Lipid Metabolism to Disease Pathogenesis

Lipids represent a vast and diverse group of hydrophobic or amphiphilic small molecules that are fundamental to life, serving as critical structural components of cellular membranes, energy storage molecules, and potent signaling mediators [1] [2]. The study of lipids, known as lipidomics, has evolved into a major research field that complements genomics and proteomics, providing a systems-level understanding of cellular physiology and pathology [2]. The structural diversity of lipids arises from complex biosynthetic pathways, leading to hundreds of thousands of distinct lipid species [3]. This complexity is organized by the Lipid Metabolites and Pathways Strategy (LIPID MAPS) consortium, which classifies lipids into eight core categories based on their biochemical subunits: fatty acyls (FA), glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP), sterol lipids (ST), prenol lipids (PR), saccharolipids (SL), and polyketides (PK) [1] [4] [2].

In the context of multi-center validation lipidomic biomarkers research, understanding this lipid diversity is paramount. Lipidomics has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying novel biomarkers in various diseases, from cardiovascular conditions to cancer [4] [5] [6]. The technological advances in mass spectrometry and chromatography have enabled researchers to detect and quantify subtle alterations in lipid profiles that correspond to specific pathological states [4] [3]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of key lipid classes, their biological functions in cellular structure and signaling, and the experimental frameworks essential for advancing lipid biomarker discovery and validation.

Key Lipid Classes: Structures and Core Biological Functions

Table 1: Major Lipid Classes: Composition, Structure, and Primary Biological Functions

| Lipid Category | Core Components / Structure | Primary Biological Functions | Cellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls (FA) [1] | Fatty acids, Eicosanoids, Fatty alcohols | Energy sources, precursors for signaling molecules (e.g., prostaglandins), inflammation [1] [7] | Cytosol, associated with carrier proteins |

| Glycerolipids (GL) [1] | Mono-, Di-, and Triacylglycerols (Triglycerides) | Energy storage, metabolic intermediates [1] [7] | Lipid droplets, adipose tissue |

| Glycerophospholipids (GP) [1] [8] | Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), Phosphatidylserine (PS), Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | Primary structural components of the plasma membrane, formation of permeability barrier, cell signaling, precursors for second messengers [1] [8] [7] | Plasma membrane (both leaflets), organelle membranes |

| Sphingolipids (SP) [1] [8] | Sphingomyelin, Ceramide, Glycosphingolipids, Sphingosine-1-phosphate | Membrane structural integrity and microdomains, cell recognition, potent signaling molecules in apoptosis, senescence, and proliferation [1] [8] [9] | Plasma membrane (primarily outer leaflet), intracellular membranes |

| Sterol Lipids (ST) [1] [8] | Cholesterol, Bile acids, Steroid hormones | Modulates membrane fluidity and rigidity, precursor for signaling molecules (hormones, bile acids) [1] [8] [7] | Plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticulum |

| Prenol Lipids (PR) [1] | Terpenes, Quinones, Carotenoids | Antioxidants (e.g., Vitamin E), electron carriers (ubiquinone), pigmentation [1] | Various intracellular membranes |

The plasma membrane exemplifies the functional collaboration between different lipid classes. Its bilayer is primarily composed of glycerophospholipids, which form the fundamental permeability barrier [8]. Sphingolipids, particularly sphingomyelin, and sterols (like cholesterol) are integrated within this bilayer, where cholesterol interacts with both phospholipids and sphingolipids to fine-tune membrane properties [8]. It can have a rigidifying effect among phospholipids but increases fluidity among sphingolipids, preventing them from forming a gel-like phase [8]. Furthermore, the membrane is asymmetrical: the inner and outer leaflets have distinct lipid compositions. For instance, charged phospholipids like phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) are predominantly maintained in the inner leaflet, while glycosphingolipids are exclusively in the outer leaflet [8]. This organization is crucial for cellular functions, including signaling and the maintenance of membrane potential.

Lipid Signaling Pathways: From Membrane to Second Messenger

Lipids are not merely passive structural components; they are dynamic signaling molecules. Lipid signaling involves lipid messengers that bind protein targets like receptors and kinases to mediate specific cellular responses, including apoptosis, proliferation, and inflammation [9] [7]. A key feature of many lipid messengers is that they are not stored but are biosynthesized "on demand" at their site of action [9].

The Ceramide/Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Rheostat

The sphingolipid pathway is a critically important signaling axis where the balance between ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) determines cell fate, often described as a "rheostat" where ceramide promotes apoptosis and S1P promotes survival and proliferation [9].

Figure 1: Sphingolipid Signaling Pathway and Cell Fate Determination

Ceramide is a central molecule in sphingolipid metabolism. It can be generated by the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by enzymes called sphingomyelinases (SMases) or synthesized de novo from serine and a fatty acyl-CoA [9]. Ceramide mediates numerous cell-stress responses, including apoptosis and senescence [9]. It can activate specific protein phosphatases (PP1, PP2A) and protein kinases (PKCζ), leading to the dephosphorylation/inactivation of pro-survival proteins like AKT [9]. This is particularly relevant in metabolic diseases; palmitate-induced ceramide accumulation can desensitize cells to insulin, linking lipid signaling to insulin resistance and diabetes [9].

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is the product of sphingosine phosphorylation by sphingosine kinase (SK) [9]. In contrast to ceramide, S1P is a potent promoter of cell survival, migration, and inflammation [9]. Its primary mode of action is through a family of G protein-coupled receptors (S1PRs) on the cell surface [9]. The enzymes that produce S1P (sphingosine kinases) are often upregulated by growth factors and cytokines, driving a pro-survival and inflammatory program [9]. The dynamic balance between ceramide and S1P levels is thus a critical determinant of cellular fate.

Glycerophospholipid-Derived Second Messengers

Glycerophospholipids in the plasma membrane are a major source of rapid second messenger generation. When cleaved by phospholipases, they produce a variety of signaling lipids [7].

- Phosphatidylinositol (PI) and its phosphorylated derivatives (PIPs): These lipids are involved in signal transduction from the cell surface to the interior. The hydrolysis of Phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) by phospholipase C produces inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). DAG remains in the membrane and activates protein kinase C (PKC), while IP3 triggers calcium release from intracellular stores [1] [7].

- Arachidonic acid (AA): This fatty acid, often esterified in membrane phospholipids, is released by phospholipase A2. It serves as the precursor for a vast family of signaling molecules collectively known as eicosanoids, which include prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes [1] [7]. These molecules are potent mediators of pain, fever, inflammation, and blood clotting [7].

Experimental Lipidomics: Methodologies for Biomarker Discovery

The translational potential of lipid biology into clinical biomarkers relies on robust and precise lipidomic methodologies. The workflow is a complex, multi-step process that requires careful planning and execution [4] [3].

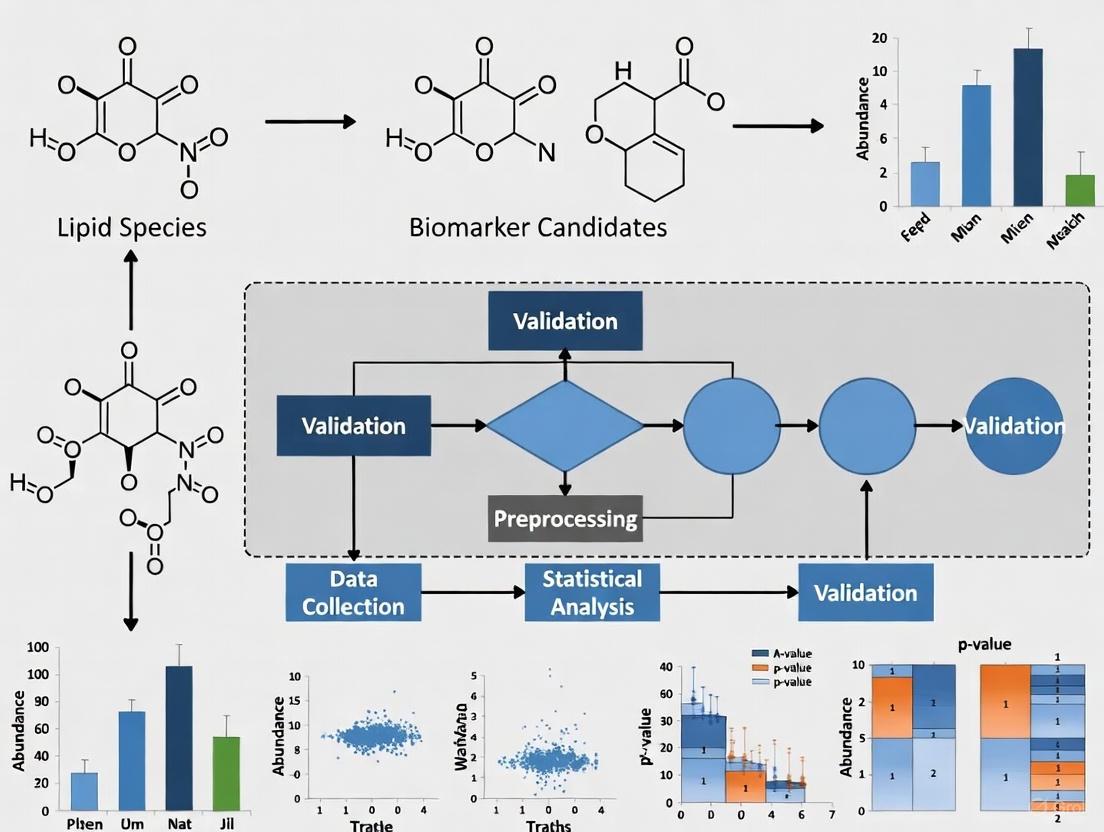

Figure 2: Lipidomics Biomarker Discovery Workflow

Core Analytical Strategies in Lipidomics

Lipidomics strategies can be broadly classified into three main approaches, each with distinct applications in biomarker research [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Lipidomics Analytical Approaches

| Approach | Objective | Key Technology | Applications in Biomarker Research | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Lipidomics [4] [3] | Comprehensive, unbiased analysis of all detectable lipids | High-Resolution MS (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) | Discovery phase: Screening for novel lipid biomarkers and pathways [4] [3] | Broad coverage, hypothesis-generating | Semi-quantitative, requires complex data analysis |

| Targeted Lipidomics [4] [3] | Precise identification and absolute quantification of a predefined set of lipids | Tandem MS (e.g., UPLC-QQQ MS) with MRM | Validation phase: Quantifying candidate biomarkers in large cohorts [4] [5] | High sensitivity, accuracy, and reproducibility | Limited to known lipids |

| Pseudo-Targeted Lipidomics [4] [3] | Combines broad coverage with improved quantification | LC-MS/MS | Bridging discovery and validation; increasing coverage of quantified lipids [4] | Improved coverage and quantitative accuracy | Method development is more complex |

A Case Study in Pancreatic Cancer Biomarker Discovery

A 2025 study on Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC) exemplifies the application of these methodologies. The researchers used a non-targeted lipidomics approach on plasma from patients and mouse models to screen for common fatty acid alterations [5]. This discovery phase identified several lipid platforms of interest. They then moved to a targeted analysis, validating 20 specific lipids (including 18 phospholipids) that could distinguish healthy individuals from PDAC patients with high accuracy (AUC of 0.9207) [5]. This study highlights how a multi-step, cross-species lipidomics workflow can identify a panel of lipid biomarkers with performance superior to the current clinical standard, CA19-9 [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroform-Methanol Mixtures [3] | Standard solvent system for lipid extraction from biological samples (e.g., Folch or Bligh & Dyer methods). | Allows phase separation; chloroform enriches lipids, methanol enriches polar metabolites. |

| Internal Standards (IS) [4] [5] | Stable isotope-labeled lipid analogs for mass spectrometry. | Critical for accurate quantification; corrects for sample loss and ion suppression; added at the beginning of extraction. |

| C18 and Silica Chromatography Columns [4] [3] | Solid-phase for lipid separation by liquid chromatography (LC) prior to MS analysis. | C18 for reverse-phase separation by fatty acyl chain; silica for normal-phase separation by lipid class polarity. |

| Mass Spectrometry Quality Control (QC) Pools [5] | A pooled sample created from all individual samples in a study. | Injected repeatedly throughout the analytical sequence to monitor instrument stability and data reproducibility. |

| Lipid Standards (Unlabeled) | Pure chemical standards for lipid identification and calibration curves. | Essential for defining retention time and generating fragmentation spectra for library matching. |

| Lipid Extraction Kits | Commercial kits for standardized, high-throughput lipid extraction. | Improve reproducibility across labs, a key challenge in multi-center studies [4]. |

The diversity of lipid classes, from the structural glycerophospholipids to the signaling-active sphingolipids and sterols, underpins their wide-ranging biological functions. Lipidomics provides the technological framework to decode this complexity and discover novel biomarkers for diseases like cancer, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis [4] [6] [3]. The path from discovery to clinical application requires a rigorous, multi-stage process. It begins with untargeted discovery, progresses to targeted validation in larger cohorts, and must culminate in multi-center validation studies to ensure reproducibility and clinical reliability [4] [5]. Despite the challenges, such as biological variability and a lack of standardized protocols, the strategic integration of lipidomics into multi-omics research holds immense promise for advancing personalized medicine, enabling earlier disease diagnosis, and informing the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Lipid metabolic reprogramming is an established hallmark of cancer, enabling tumor cells to sustain uncontrolled proliferation, survive in harsh microenvironments, and resist therapeutic interventions. This review synthesizes evidence from pancreatic, liver, and gynecological cancers to elucidate the shared and unique alterations in lipid uptake, synthesis, storage, and oxidation that drive oncogenesis. We present a comprehensive analysis of lipidomic biomarkers with diagnostic and therapeutic potential, detailing experimental protocols for their identification and validation. The integrated multi-omics approach reveals distinct lipid signatures across cancer types, while highlighting emerging targets for therapeutic intervention. Within the framework of multi-center validation lipidomic biomarkers research, we compare quantitative data from recent studies and provide standardized methodologies for reproducing key findings, offering researchers a validated toolkit for advancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies targeting cancer lipid metabolism.

Metabolic reprogramming constitutes a core hallmark of cancer, with lipid metabolism emerging as a critical facilitator of tumor progression, metastasis, and treatment resistance across diverse malignancies [10] [11]. Cancer cells extensively rewire their lipid metabolic pathways to fulfill bioenergetic demands, generate membrane components, and produce signaling molecules that sustain proliferative programs [10]. This reprogramming encompasses enhanced lipid uptake, de novo lipogenesis, lipid storage, and fatty acid oxidation (FAO), creating metabolic dependencies that can be therapeutically exploited [10].

The tumor microenvironment (TME) further shapes lipid metabolic adaptations through hypoxia, nutrient scarcity, and metabolic crosstalk between cancer cells and stromal components [10]. Understanding the commonalities and distinctions in lipid metabolic rewiring across different cancers provides crucial insights for developing targeted interventions. This review systematically examines lipid metabolic reprogramming in three cancer types with significant metabolic dependencies: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and gynecological cancers, with specific emphasis on endometrial cancer (EC).

Recent advances in lipidomics technologies have enabled comprehensive profiling of lipid species alterations in tumors, revealing potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [4] [12]. The integration of lipidomics with other omics approaches (transcriptomics, proteomics) provides unprecedented insights into the regulatory networks governing lipid metabolic reprogramming [12]. This review synthesizes findings from such integrated studies and presents standardized experimental workflows to guide future research into lipid-based biomarkers and therapies.

Lipid Metabolic Pathways in Cancer: A Comparative Analysis

Key Alterations in Lipid Metabolism Across Cancers

Table 1: Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming Across Cancer Types

| Metabolic Process | Pancreatic Cancer | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Gynecological Cancers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Uptake | CD36 overexpression; FABP-mediated uptake [10] | CD36 upregulation; LDLR enhancement [13] | CD36 overexpression; FABP involvement [10] |

| De novo Lipogenesis | FASN, ACC, ACLY overexpression [14] [11] | FASN, ACC, ACLY upregulation [13] | FASN, ACC, ACLY overexpression [11] |

| Fatty Acid Oxidation | CPT1A/C upregulation [11] | CPT1A/C enhancement [13] | CPT1C upregulation via PPARα [15] |

| Desaturation | SCD1 overexpression [10] | SCD1 upregulation [13] | SCD1 enhancement [10] |

| Cholesterol Metabolism | LDLR upregulation; enhanced synthesis [11] | HMGCR upregulation; LDLR enhancement [13] | HMGCR overexpression; LDLR upregulation [11] |

| Key Enzymes/Transporters | ACSL1, ACSL4 [12] | ACSL1, ACSL4, GPD1 [12] | ACSL4 [15] |

| Signaling Pathways | KRAS, HIF-1α, PI3K/Akt/mTOR [14] | Wnt/β-catenin, PI3K/Akt/mTOR [13] | PPARα, E2F2 [15] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The rewiring of lipid metabolism in cancer cells is orchestrated by oncogenic signaling pathways and environmental cues. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway emerges as a central regulator across cancer types, enhancing lipid synthesis through activation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) that transcriptionally upregulate lipogenic enzymes like FASN, ACC, and ACLY [14] [13]. In pancreatic cancer, KRAS mutations drive metabolic reprogramming by enhancing lipid uptake and synthesis, while HIF-1α stabilizes under hypoxia to promote lipid storage and utilization [14].

In hepatocellular carcinoma, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway directly influences lipid metabolism by regulating glutamine synthetase expression, thereby connecting amino acid and lipid metabolic networks [13]. c-MYC amplification, common in HCC, transcriptionally upregulates enzymes involved in fatty acid synthesis and glutamine metabolism, providing precursors for lipid synthesis [13].

For gynecological cancers, particularly endometrial cancer, PPARα serves as a master regulator of lipid metabolic genes, including ACSL4 and CPT1C, creating a feedforward loop that sustains FAO [15]. Concurrently, E2F2 drives cell cycle progression while intersecting with metabolic circuits, forming a positive feedback loop with ACSL4 that coordinately enhances both proliferation and metabolic adaptation [15].

Figure 1: Regulatory Networks in Cancer Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming. This diagram illustrates how extracellular factors (hypoxia, oncogenes, obesity) activate key signaling pathways that coordinately regulate lipid metabolic processes, ultimately driving tumor progression, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Dashed lines indicate feedback mechanisms.

Cancer-Specific Lipid Metabolic Reprogramming

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

Pancreatic cancer demonstrates extensive lipid metabolic reprogramming to support its aggressive growth in a nutrient-poor, hypoxic microenvironment [14]. PDAC cells upregulate both de novo lipogenesis and exogenous lipid uptake to satisfy their substantial membrane biosynthesis and energy requirements [5]. FASN overexpression is nearly universal in PDAC and correlates with poor prognosis, while SCD1 upregulation enhances the production of monounsaturated fatty acids that maintain membrane fluidity and support signaling pathways [10] [11].

The lipid-rich, fibrotic TME of pancreatic cancer further shapes metabolic adaptations. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) provide lipids to cancer cells through metabolic coupling, creating a feedforward loop that sustains tumor growth [10]. PDAC cells also demonstrate enhanced fatty acid oxidation (FAO) under nutrient deprivation, with CPT1A upregulation enabling mitochondrial import and oxidation of fatty acids for ATP production [11]. This metabolic flexibility contributes to chemotherapy resistance, as FAO inhibition sensitizes PDAC cells to gemcitabine [14].

Notably, lipid droplet accumulation serves as a marker of PDAC aggressiveness and chemoresistance. Cancer stem cells within PDAC tumors exhibit higher lipid content than their differentiated counterparts, and LD-rich cells demonstrate increased resistance to cytotoxic therapies [11]. The dependence of PDAC on lipid metabolic pathways offers promising therapeutic targets, with inhibitors of FASN, SCD1, and CPT1 showing efficacy in preclinical models [14] [11].

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

As the metabolic hub of the body, the liver normally maintains lipid homeostasis, but HCC development involves profound dysregulation of lipid metabolic pathways [13]. The connection between HCC and underlying conditions such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and obesity highlights the importance of lipid metabolism in hepatocarcinogenesis [16]. HCC cells exhibit enhanced lipid uptake via CD36 and LDLR, increased de novo lipogenesis through FASN and ACLY, and upregulated cholesterol synthesis via HMGCR [13].

Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal distinctive lipid signatures in HCC tissues compared to adjacent non-tumor tissues [12]. Transcriptomic and proteomic profiling identifies key deregulated genes including ACSL1, ACSL4, GPD1, LCAT, PEMT, and LPCAT1, which coordinately enhance fatty acid activation, phospholipid remodeling, and lipid storage [12]. Metabolomic studies further demonstrate alterations in phosphatidylcholines, sphingolipids, and carnitine esters that distinguish HCC from normal liver tissue [12].

The PPARα pathway plays a central role in regulating lipid catabolism in HCC, driving the expression of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation [13]. This pathway enables HCC cells to utilize fatty acids as an energy source, particularly under conditions of metabolic stress. Additionally, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway influences lipid metabolism by regulating glutamine synthetase expression, thereby connecting amino acid and lipid metabolic networks [13]. Targeting lipid metabolic enzymes such as ACSL4 has shown promise in preclinical HCC models, impairing tumor growth and enhancing sensitivity to therapy [15].

Gynecological Cancers (Endometrial Cancer)

Endometrial cancer exhibits strong associations with obesity and metabolic syndrome, highlighting the importance of lipid metabolic reprogramming in its pathogenesis [15]. EC cells demonstrate enhanced lipogenesis mediated by FASN and ACLY upregulation, providing lipids for membrane synthesis and signaling molecules that drive proliferation [15]. The ACSL4 enzyme emerges as a critical node in EC lipid metabolism, activating polyunsaturated fatty acids for incorporation into complex lipids or oxidation [15].

Recent research has identified a novel ACSL4-E2F2 positive feedback loop that coordinately regulates lipid metabolism and cell cycle progression in endometrial cancer [15]. ACSL4 upregulates E2F2 through activation of the PPARα-CPT1C-FAO axis, while E2F2 transcriptionally enhances ACSL4 expression, creating an amplification circuit that drives both metabolic reprogramming and proliferation [15]. This mechanism links the obesity-driven lipid-rich environment directly to tumor growth, explaining the epidemiological connection between obesity and endometrial cancer incidence.

Therapeutic targeting of this axis through ACSL4 inhibition suppresses EC progression in preclinical models, validating the clinical potential of targeting lipid metabolic pathways [15]. Additionally, the dependence of EC cells on CPT1C-mediated FAO provides an alternative targeting strategy, particularly for tumors with ACSL4 overexpression [15].

Diagnostic Biomarker Discovery through Lipidomics

Lipidomic Signatures as Diagnostic Tools

Lipidomics has emerged as a powerful approach for identifying cancer biomarkers, with specific lipid signatures demonstrating diagnostic potential across multiple cancer types [4] [12] [5]. Advances in mass spectrometry-based lipid profiling enable comprehensive characterization of lipid alterations in tumors, revealing distinct patterns that can distinguish malignant from normal tissues with high accuracy [4].

Table 2: Lipidomic Biomarkers in Cancer Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Lipid Classes Altered | Specific Lipid Biomarkers | Diagnostic Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic Cancer | Phospholipids, Acylcarnitines, Sphingolipids, Fatty Acid Amides | 18 phospholipids, 1 acylcarnitine, 1 sphingolipid | AUC 0.9207 (0.9427 with CA19-9) | [5] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Glycerophospholipids, Sphingolipids, Fatty Acids | LCAT, PEMT, ACSL1, GPD1, ACSL4, LPCAT1 | 6 metabolites with AUC >0.8 | [12] |

| Cervical Cancer | Ceramides, Sphingosine, Phospholipids | 2 ceramides, 1 sphingosine metabolite | Discriminate HSIL from normal | [17] |

In pancreatic cancer, a recent multi-platform lipidomics study identified 20 lipid species that consistently differentiated PDAC patients from healthy controls across multiple validation sets [5]. A model incorporating 11 phospholipids achieved an AUC of 0.9207, significantly outperforming the conventional biomarker CA19-9 (AUC 0.7354) [5]. When combined with CA19-9, the diagnostic performance further improved to AUC 0.9427, demonstrating the complementary value of lipid biomarkers [5].

Hepatocellular carcinoma exhibits distinct lipidomic alterations identifiable through integrated multi-omics approaches [12]. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of HCC tissues reveal significant enrichment of lipid metabolism-related pathways, including fatty acid degradation and steroid hormone biosynthesis [12]. Six key genes (LCAT, PEMT, ACSL1, GPD1, ACSL4, and LPCAT1) show consistent changes at both mRNA and protein levels, correlating strongly with lipid metabolite alterations and offering diagnostic potential [12].

Cervical cancer lipidomics has identified specific ceramides and sphingosine metabolites that distinguish high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) from normal tissue, independent of HPV status [17]. Plasma metabolomic profiling further reveals alterations in prostaglandins, phospholipids, and sphingolipids that differentiate cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and invasive cancer from healthy controls [17].

Experimental Protocols for Lipidomic Biomarker Discovery

Protocol 1: Untargeted Lipidomics for Biomarker Discovery

Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect plasma/serum samples after overnight fasting or tissue samples snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For plasma, add antioxidant preservatives and store at -80°C until analysis [5].

Lipid Extraction: Use modified Folch or Bligh-Dyer methods with chloroform:methanol (2:1 v/v). Add internal standards for quantification [4] [5].

LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Platform: Ultimate 3000-LTQ-Orbitrap XL or similar high-resolution mass spectrometer

- Chromatography: Reversed-phase C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: (A) acetonitrile:water (60:40) with 10mM ammonium formate; (B) isopropanol:acetonitrile (90:10) with 10mM ammonium formate

- Gradient: 0-2 min 30% B, 2-25 min 30-100% B, 25-30 min 100% B

- MS Parameters: ESI positive/negative mode, mass range 150-2000 m/z, data-dependent MS/MS [5]

Data Processing: Use software (Compound Discoverer, MS-DIAL, Lipostar) for peak picking, alignment, and identification against lipid databases (LIPID MAPS, HMDB) [4].

Statistical Analysis: Apply multivariate statistics (PCA, PLS-DA) and machine learning algorithms to identify discriminatory lipid features. Validate with univariate tests and ROC analysis [5].

Protocol 2: Multi-omics Integration for Lipid Pathway Analysis

Transcriptomic Profiling: Extract total RNA, prepare cDNA libraries, and sequence on Illumina platform. Map reads to reference genome, quantify gene expression, identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with DESeq2 [12].

Proteomic Analysis: Homogenize tissues in lysis buffer, digest proteins with trypsin, fractionate peptides by high-pH reverse phase chromatography. Analyze on Orbitrap Fusion Lumos with LC-MS/MS. Identify differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) [12].

Integration Analysis: Map DEGs and DEPs to KEGG lipid metabolic pathways. Correlate expression changes with lipid metabolite alterations. Identify key regulatory nodes through pathway enrichment and network analysis [12].

Figure 2: Integrated Multi-omics Workflow for Lipid Biomarker Discovery. This diagram outlines the comprehensive approach for identifying and validating lipid metabolic biomarkers, encompassing sample collection, multi-omics profiling, data integration, and clinical application.

Therapeutic Targeting of Lipid Metabolism

Preclinical and Clinical Development

Therapeutic targeting of lipid metabolic pathways represents a promising strategy for cancer treatment, with several approaches in various stages of development:

FASN Inhibitors: TVB-2640 (denifanstat) has shown efficacy in preclinical models of multiple cancers, including breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer [11]. Phase I/II trials demonstrate acceptable safety and preliminary activity, particularly in KRAS-mutant cancers [11].

ACSL4 Inhibitors: PRGL493 and other small-molecule inhibitors suppress endometrial cancer progression in vivo by disrupting the ACSL4-PPARα-CPT1C axis and reducing cancer stemness [15]. ACSL4 inhibition also shows promise in hepatocellular carcinoma models [15].

CPT1 Inhibitors: Etomoxir, perhexiline, and other CPT1 inhibitors block fatty acid oxidation, sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapy and targeted therapies [14] [11]. These are particularly effective in tumors reliant on FAO for energy production.

SCD1 Inhibitors: MF-438 and other desaturase inhibitors disrupt membrane fluidity and lipid signaling, demonstrating antitumor effects in pancreatic and liver cancer models [10] [11].

CD36 Antibodies: Blocking this fatty acid transporter impairs lipid uptake and suppresses metastasis in multiple cancer models, including ovarian, breast, and oral cancers [10].

Combination Therapies

Targeting lipid metabolism enhances the efficacy of conventional and targeted therapies:

Chemotherapy Sensitization: FAO inhibition reverses chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by reducing ATP production and increasing oxidative stress [14]. FASN inhibition enhances gemcitabine efficacy in PDAC models through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress [14].

Immunotherapy Combinations: Modulating lipid metabolism in the TME enhances antitumor immunity. CD36 blockade improves CD8+ T cell function by reducing lipid accumulation-induced dysfunction [10]. COX-2 inhibitors, which target prostaglandin synthesis, enhance checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in preclinical models [10].

Targeted Therapy Synergy: SCD1 inhibition enhances the efficacy of EGFR inhibitors in lung cancer and HER2-targeted therapies in breast cancer by disrupting membrane lipid composition and signaling [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Lipid Metabolism Research

| Category | Reagent/Solution | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid Extraction | Modified Folch Reagent (CHCl₃:MeOH 2:1) | Lipid extraction from tissues/body fluids | Preserves lipid integrity; compatible with MS |

| Bligh & Dyer Solution | Alternative extraction method | Effective for polar lipids | |

| Internal Standards | SPLASH LIPIDOMIX Mass Spec Standard | Lipid quantification | Covers multiple lipid classes; stable isotope-labeled |

| Avanti Polar Lipids Internal Standards | Targeted lipid analysis | Individual lipid class standards | |

| LC-MS Reagents | Ammonium Formate/Ammonium Acetate | Mobile phase additives | Enhances ionization; reduces adduct formation |

| HPLC-grade Solvents (ACN, MeOH, IPA) | LC-MS mobile phases | Low UV absorbance; high purity | |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | TVB-2640 (FASN inhibitor) | Target validation; therapeutic studies | Clinical-stage inhibitor; good bioavailability |

| Etomoxir (CPT1 inhibitor) | FAO inhibition studies | Well-characterized; widely used | |

| PRGL493 (ACSL4 inhibitor) | ACSL4 pathway studies | Specific ACSL4 inhibition [15] | |

| Antibodies | Anti-ACSL4 (for WB/IHC) | Protein expression analysis | Validated for multiple applications [15] |

| Anti-CD36 (for flow/IF) | Lipid uptake studies | Cell surface staining | |

| Anti-FASN (for WB/IHC) | Lipogenesis assessment | Widely used in cancer research | |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Fatty acid-free BSA | Fatty acid delivery to cells | Controls fatty acid concentrations |

| Lipid-rich media (e.g., with oleate) | Lipid loading studies | Mimics obese/tumor microenvironment |

Lipid metabolic reprogramming represents a convergent hallmark across pancreatic, liver, and gynecological cancers, driven by both oncogenic signaling and microenvironmental pressures. The consistent alterations in lipid uptake, synthesis, storage, and oxidation pathways across these malignancies highlight the fundamental role of lipid metabolism in supporting tumor progression and therapy resistance.

Integrated multi-omics approaches have unveiled distinct lipid signatures with diagnostic potential, offering improved sensitivity and specificity over conventional biomarkers. The identification of specific lipid species and enzymes as therapeutic targets, including ACSL4, FASN, and CPT1, provides promising avenues for intervention. However, translating these findings into clinical practice requires standardized methodologies, robust validation across diverse patient populations, and careful consideration of the metabolic complexities within the tumor microenvironment.

Future research should focus on expanding multi-center validation studies for lipidomic biomarkers, developing more specific inhibitors targeting key lipid metabolic enzymes, and exploring combination strategies that exploit metabolic dependencies while minimizing systemic toxicity. The Scientist's Toolkit provided herein offers a foundation for standardizing methodologies across research laboratories, facilitating reproducibility and comparison of findings. As our understanding of cancer lipid metabolism deepens, targeting these pathways holds significant promise for improving early detection, monitoring treatment response, and developing more effective therapeutic strategies for these challenging malignancies.

Nonsyndromic cleft lip with palate (nsCLP) is among the most common congenital craniofacial anomalies, affecting approximately 1 in 700 live births globally [18]. Current diagnostic methods primarily rely on fetal ultrasound imaging, which remains limited by factors such as fetal position and technician skill [19]. The emergence of lipidomics—the comprehensive study of lipid molecules and their biological functions—offers promising avenues for identifying molecular biomarkers that could enable earlier and more reliable detection [4]. Lipids constitute thousands of chemically distinct molecules that play vital roles in cellular processes including signaling, energy storage, and structural membrane integrity [4]. Their molecular structures largely determine their functions, and disruptions in lipid homeostasis can provide crucial information about disease mechanisms [4]. This case study examines how integrated lipidomics and machine learning approaches have identified specific altered lipid pathways in nsCLP, potentially paving the way for novel diagnostic strategies.

Experimental Design and Methodological Framework

Study Cohorts and Sampling Strategy

The investigation employed a multi-stage cohort design to ensure robust biomarker discovery and validation [19]. In the initial discovery phase, researchers conducted untargeted lipidomics profiling on maternal serum samples from a cohort of nsCLP-affected pregnancies and matched controls. This approach aimed to capture a comprehensive view of the lipid landscape without pre-selecting specific lipid classes. Promising candidate biomarkers identified in this phase were subsequently evaluated using targeted lipidomics in a separate validation cohort, ensuring that findings were reproducible across different sample sets [19]. To further strengthen the validity of results, an additional validation cohort incorporating early serum samples from the nsCLP group was also analyzed, providing temporal insights into lipid alterations [19].

Analytical Platform: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

Table 1: Core Lipidomics Analytical Platform Specifications

| Component | Specification | Application in nsCLP Study |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Technique | Liquid Chromatography | Separation of complex lipid mixtures from serum samples |

| Detection Instrument | Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Accurate mass measurement and structural characterization |

| Analytical Approach | Untargeted & Targeted | Comprehensive discovery followed by quantitative validation |

| Data Processing | Compound Discoverer software | Feature extraction, alignment, and identification |

Lipidomic profiling was performed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), a powerful analytical platform that combines separation capabilities with sensitive detection [19]. The untargeted approach provided a comprehensive assessment of lipid species present in the samples, regardless of whether they were previously known or unknown, thereby offering a complete picture of the lipid profile [4]. For the targeted validation phase, the methodology shifted to precise quantification of specific candidate lipids, enhancing reproducibility and reliability of the measurements [4]. This dual approach balanced discovery power with analytical rigor, addressing a common challenge in biomarker research.

Data Analysis and Machine Learning Integration

Table 2: Machine Learning and Statistical Approaches for Biomarker Discovery

| Analytical Method | Implementation Purpose | Outcome in nsCLP Study |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection Methods | Eight different algorithms to assess dysregulated lipids | Identified most consistently altered lipid species |

| Robust Rank Aggregation | Integrated results from multiple feature selection methods | Prioritized candidate biomarkers with consensus importance |

| Classification Models | Seven different models to retrieve biomarker panels | Identified optimal combination of diagnostic lipids |

| Multivariate Analyses | Constructed diagnostic models with selected lipids | Finalized minimal biomarker panel with high diagnostic performance |

The data analysis framework employed multiple computational techniques to ensure reliable biomarker identification [19]. Eight distinct feature selection methods were initially applied to assess dysregulated lipids from the untargeted lipidomics data. The robust rank aggregation algorithm then integrated these selections to prioritize the most consistently significant lipid species [19]. Subsequently, seven classification models were applied to retrieve a panel of candidate lipid biomarkers. This multi-algorithm approach mitigated biases inherent in any single method and increased confidence in the final biomarker selection [19].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Lipid Biomarker Discovery in nsCLP

Key Findings: Altered Lipid Pathways and Diagnostic Biomarkers

Identified Lipid Biomarkers and Their Diagnostic Performance

The integrated analysis revealed a panel of three lipid biomarkers with strong diagnostic potential for nsCLP [19]. The specific lipids identified included FA (20:4), likely arachidonic acid, and LPC (18:0), a lysophosphatidylcholine species [19]. Both were significantly downregulated in early serum samples from the nsCLP group in the additional validation cohort, suggesting their potential role in early detection [19]. The diagnostic model incorporating these three lipids achieved high performance in determining nsCLP status, demonstrating the power of minimal biomarker panels when properly selected and validated [19].

Table 3: Validated Lipid Biomarkers in nsCLP

| Lipid Biomarker | Class | Regulation in nsCLP | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA (20:4) | Fatty Acyl (Arachidonic Acid) | Downregulated | Precursor for signaling molecules; membrane fluidity |

| LPC (18:0) | Glycerophospholipid (Lysophosphatidylcholine) | Downregulated | Signaling lipid; involved in cell membrane structure |

| Third Lipid | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Biological Implications of Lipid Alterations

The observed alterations in specific lipid species provide insights into potential mechanistic pathways involved in nsCLP pathogenesis. Arachidonic acid (FA 20:4) serves as a precursor for eicosanoids, signaling molecules that play crucial roles in inflammation and embryonic development [4]. Similarly, lysophosphatidylcholines like LPC (18:0) are involved in cell signaling and membrane structure [4]. The significant downregulation of these lipids in nsCLP maternal serum suggests potential disruptions in lipid-mediated signaling pathways during critical stages of craniofacial development. These findings align with emerging understanding that lipids are not merely structural components but active participants in developmental processes, with dysregulation potentially contributing to congenital anomalies [4].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Lipidomics Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Platform Category | Specific Examples | Function in nsCLP Study |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Systems | Liquid Chromatography (LC) | Separation of complex lipid mixtures prior to detection |

| Mass Spectrometry Instruments | LTQ-Orbitrap XL MS | Accurate mass measurement and structural characterization |

| Data Processing Software | Compound Discoverer; MS DIAL; Lipostar | Lipid feature extraction, alignment, and identification |

| Bioinformatics Algorithms | Robust Rank Aggregation; Multiple Classifiers | Prioritization of biomarker candidates from large datasets |

| Lipid Reference Databases | LIPID MAPS Classification | Structural annotation of identified lipid species |

The implementation of lipidomics biomarker discovery requires specialized reagents and platforms [19] [4]. Liquid chromatography systems enable separation of complex lipid mixtures, while mass spectrometry instruments provide sensitive detection and structural information [5]. Bioinformatics tools are equally crucial, as they transform raw instrumental data into biologically meaningful information [19] [4]. The nsCLP study utilized specialized software for lipid feature extraction and alignment, followed by multiple statistical and machine learning algorithms for biomarker selection [19]. Reference databases such as LIPID MAPS provide standardized classification and nomenclature systems essential for consistent lipid identification across studies [4].

Multi-Center Validation Challenges and Solutions

Reproducibility and Technical Variability

A significant challenge in lipidomic biomarker research involves reproducibility across different analytical platforms and laboratories [4]. Recent studies indicate that prominent software platforms like MS DIAL and Lipostar demonstrate only approximately 14-36% agreement in lipid identifications when using default settings, even when analyzing identical LC-MS data [4]. This technical variability complicates cross-study comparisons and multi-center validation efforts. To address these challenges, researchers have emphasized standardized protocols for sample collection, processing, and data analysis [4]. Additionally, the use of targeted validation following untargeted discovery, as implemented in the nsCLP study, improves the reliability of findings [19].

Integration with Multi-Omics Data

The complexity of nsCLP pathogenesis suggests that lipid biomarkers alone may not capture the full pathological picture. Integration with other data types, including genomic, proteomic, and clinical information, provides a more comprehensive understanding [4]. Family-based trio studies examining genetic polymorphisms in genes such as ABCA4, which is involved in lipid transport, have revealed potential genetic contributors to NSCL/P that may interact with the lipid alterations observed in the lipidomics study [18]. Such integrated approaches align with systems biology perspectives that recognize complex traits like nsCLP as emerging from interactions across multiple biological layers [4].

Figure 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration for Biomarker Validation

Comparative Performance: Lipid Biomarkers Versus Conventional Methods

Table 5: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Approaches for nsCLP

| Diagnostic Method | Strengths | Limitations | Target Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Ultrasound (Current Standard) | Non-invasive; visualizes anatomy | Limited by fetal position, technician skill | General obstetric population |

| Genetic Risk Markers | Potential for early risk assessment | Incomplete penetrance; population-specific variants | High-risk families |

| Lipid Biomarker Panel | Objective biochemical measure; early detection | Requires validation in diverse populations | Maternal serum screening |

When compared to conventional diagnostic methods for nsCLP, lipid biomarkers offer distinct advantages and limitations. Current ultrasound-based diagnosis, while non-invasive and providing direct structural information, faces limitations including dependence on fetal position and technician expertise [19]. Genetic markers have shown promise but often exhibit population-specific variations and inconsistent replicability across ethnic groups [18]. In contrast, lipid biomarkers present an objective biochemical measure that could potentially enable earlier detection, though they require extensive validation across diverse populations before clinical implementation [19] [4]. The diagnostic model developed in the nsCLP study demonstrated high performance with just three lipids, suggesting potential clinical utility if validated in broader cohorts [19].

Future Directions and Translational Potential

The translational pathway for lipid biomarkers in nsCLP requires addressing several key challenges. While the FDA has approved very few lipid-based biomarkers to date, examples such as the Tina-quant Lipoprotein(a) assay demonstrate the feasibility of clinical implementation [4]. Future directions include leveraging artificial intelligence to enhance lipid annotation accuracy, with models like MS2Lipid demonstrating up to 97.4% accuracy in predicting lipid subclasses [4]. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration among lipid biologists, physicians, bioinformaticians, and regulatory scientists is essential to fully realize the potential of lipidomics in personalized medicine approaches to congenital anomaly detection and prevention [4]. The established workflow from this nsCLP case study—combining untargeted discovery, machine-learning-driven feature selection, and targeted validation—provides a template that can be adapted to other congenital disorders potentially linked to lipid metabolic disruptions.

In the evolving landscape of precision medicine, the quest for reliable, non-invasive biomarkers has become a paramount objective across therapeutic areas. Among various candidates, lipids have emerged as particularly promising targets for blood-based biomarker development. Lipids represent a fundamental component of human metabolism, constituting approximately 70% of the metabolites in plasma and playing crucial roles in cellular structure, energy storage, and signaling pathways [3]. The field of lipidomics, which enables comprehensive analysis of lipid species and their dynamic alterations, has opened new avenues for understanding disease mechanisms and identifying clinically useful biomarkers [4] [3].

The translational potential of lipid biomarkers stems from their direct reflection of pathophysiological processes occurring at the cellular level. Unlike genetic or proteomic biomarkers, which indicate potential or expressed activity, lipid profiles represent functional metabolic endpoints that capture real-time biochemical alterations in disease states [3]. This review examines the strategic advantages of lipids as non-invasive blood-based biomarkers, supported by experimental data and methodological considerations, within the critical context of multi-center validation research required for clinical adoption.

Strategic Advantages of Lipids as Blood-Based Biomarkers

Biological and Technical Rationale

Lipids offer distinctive advantages as biomarker candidates due to their structural diversity, metabolic responsiveness, and detectability in accessible biofluids. The biological system contains thousands of chemically distinct lipids classified into eight major categories: fatty acyls (FA), glycerolipids (GL), glycerophospholipids (GP), sphingolipids (SP), sterol lipids (ST), prenol lipids (PR), saccharolipids (SL), and polyketides (PK) [4]. This molecular diversity enables precise mapping of disease-specific signatures, as different pathological processes affect distinct lipid pathways.

From a technical perspective, lipids demonstrate remarkable stability in blood samples compared to more labile molecules such as proteins or RNA. This characteristic reduces pre-analytical variability and facilitates standardized clinical sampling protocols. Additionally, advances in analytical platforms, particularly high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) coupled with liquid chromatography (LC), have dramatically improved the sensitivity, resolution, and throughput of lipid detection [20] [3]. The technological progress in lipidomics has greatly advanced our comprehension of lipid metabolism and biochemical mechanisms in diseases, while also offering new technical pathways for identifying potential biomarkers [3].

Physiological Reflection in Accessible Compartments

Blood-based lipid biomarkers provide a window into systemic physiology while simultaneously reflecting tissue-specific alterations. For instance, red blood cell membrane (RCM) lipids have been shown to accumulate over time and reflect chronic physiological alterations rather than fleeting changes, providing profound insight into long-term disease trajectories such as Alzheimer's disease [21]. This temporal stability enhances their diagnostic utility for chronic conditions where single timepoint plasma measurements might miss relevant pathophysiology.

The non-invasive nature of blood sampling facilitates repeated measurements, enabling dynamic monitoring of disease progression and treatment response. This addresses a critical limitation of tissue-based biomarkers that require invasive procedures such as biopsies, which carry risks of bleeding, pain, and infection [22]. The practical advantage of blood-based lipid biomarkers is particularly valuable for longitudinal studies and chronic disease management where frequent sampling is necessary.

Table 1: Comparative Advantages of Lipid Biomarkers Over Other Molecular Classes

| Feature | Lipid Biomarkers | Genetic Biomarkers | Protein Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability in blood | High stability in plasma and RBC membranes | High stability | Moderate to low stability |

| Reflects current physiology | Real-time metabolic status | Predisposition only | Expressed activity |

| Technical detection | Advanced LC-HRMS methods | PCR, sequencing | Immunoassays, MS |

| Dynamic range | Extensive molecular diversity | Limited to gene variants | Moderate diversity |

| Pathway coverage | Broad metabolic pathway representation | Limited pathway insight | Signaling pathways |

Lipidomics Methodologies: Experimental Workflows for Biomarker Discovery

Analytical Platforms and Strategies

Lipidomics employs three primary analytical strategies, each with distinct advantages for biomarker discovery. Untargeted lipidomics provides comprehensive, unbiased analysis of all detectable lipid species in a sample, making it ideal for discovery-phase research [3]. This approach typically utilizes high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) with data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) modes to achieve extensive lipid coverage [3]. The exceptional mass resolution and accuracy of HRMS platforms, including Quadrupole Time-of-Flight (Q-TOF) and Orbitrap instruments, enable precise structural elucidation of lipid molecules [3].

Targeted lipidomics focuses on precise identification and quantification of predefined lipid panels with enhanced accuracy and sensitivity [3]. This approach typically employs triple quadrupole mass spectrometers operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode, offering superior quantification capabilities for validation studies [3]. The pseudo-targeted approach represents a hybrid strategy that combines the comprehensive coverage of untargeted methods with the quantitative rigor of targeted analysis, making it suitable for complex disease characterization [3].

Standardized Workflow for Lipid Biomarker Discovery

A robust lipidomics workflow encompasses multiple critical stages from sample collection to data interpretation. The process begins with standardized sample collection using appropriate anticoagulants and strict fasting conditions to minimize pre-analytical variability [20]. For plasma preparation, samples are typically centrifuged within 2-6 hours of collection and stored at -80°C until analysis [20]. The lipid extraction step often employs modified Folch or Bligh-Dyer methods using chloroform-methanol or isopropanol-based solvents to achieve efficient recovery of diverse lipid classes [20] [21].

For LC-MS analysis, reverse-phase chromatography with C18 columns provides excellent separation of most lipid classes using binary mobile phase gradients [20] [21]. Mobile phase A typically consists of acetonitrile-water (60:40) with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid, while mobile phase B contains isopropanol-acetonitrile (90:10) with the same additives [21]. Mass spectrometry detection in both positive and negative ionization modes ensures comprehensive coverage of ionizable lipid species, with capillary voltages typically set at +3.0 kV for positive mode and -2.5 kV for negative mode [21].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Lipidomics

| Category | Specific Items | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | EDTA or heparin tubes, PBS, Tris-HCl buffer | Blood collection, RBC washing, hemolysis |

| Lipid Extraction | Isopropanol, methanol, acetonitrile, chloroform | Protein precipitation, lipid solubilization |

| Chromatography | UPLC systems, C18 columns (e.g., Waters ACQUITY) | Lipid separation prior to MS detection |

| Mass Spectrometry | Q-TOF, Orbitrap, Triple Quadrupole instruments | Lipid detection, identification, quantification |

| Internal Standards | PC 14:0, PC 18:0-18:1, LPC 17:0 | Quantification normalization, quality control |

| Data Processing | Progenesis QI, MS-DIAL, Lipostar | Peak alignment, identification, statistical analysis |

Diagram 1: Comprehensive lipidomics workflow for biomarker discovery and validation.

Experimental Evidence: Lipid Biomarkers in Clinical Applications

Oncology Applications

Substantial evidence demonstrates the clinical potential of lipid biomarkers in cancer detection and stratification. A 2025 study on non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) employed LC-HRMS to analyze plasma samples from 106 patients and 108 healthy controls [20]. The research identified a three-lipid panel comprising PE(14:1/20:0), PE(18:2/16:0), and 19-methyl-heneicosanoic acid that achieved exceptional diagnostic performance with an AUC of 0.88 in the training cohort and 0.82 in the validation cohort [20]. Notably, for distinguishing between low-grade and high-grade NMIBC, a four-lipid panel demonstrated an AUC of 0.815, with consistent performance in 10-fold cross-validation (AUC: 0.77) and leave-one-out validation (AUC: 0.77) [20].

In gynecological cancers, lipidomics has revealed disease-specific signatures with diagnostic potential. Altered lipid metabolism supports the energy demands of rapidly proliferating cancer cells, and specific lipid classes including glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, and fatty acyls show consistent alterations in ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers [3]. These findings highlight the fundamental role of lipid metabolic reprogramming in cancer pathogenesis and the opportunity to leverage these changes for early detection.

Neurodegenerative Disorders

Lipid biomarkers show particular promise for neurodegenerative conditions where early diagnosis remains challenging. A 2025 study on Alzheimer's disease (AD) incorporated both plasma and red blood cell membrane (RCM) lipids to identify diagnostic signatures [21]. The investigation revealed that RCM lipids provided superior separation between normal subjects, those with amnestic mild cognitive impairment, and AD patients compared to plasma lipids alone [21]. This advantage stems from the ability of RCM lipids to reflect chronic physiological alterations rather than acute fluctuations, providing a more stable biomarker platform for progressive conditions [21].

The study identified 138 differentially expressed lipids enriched in AD-related pathways, with six lipids selected as a potential biomarker panel based on multi-dimensional criteria [21]. The incorporation of RCM lipids enhanced diagnostic performance and highlighted the value of exploring alternative blood compartments beyond plasma for biomarker discovery. This approach addresses the critical need for non-invasive alternatives to cerebrospinal fluid analysis and PET imaging, which are invasive, costly, and limited in clinical utility, especially in early disease stages [21].

Metabolic and Cardiovascular Diseases

Lipidomics has naturally found extensive application in metabolic and cardiovascular disorders where lipid metabolism plays a central pathophysiological role. Specific ceramides and phosphatidylcholines have been associated with cardiovascular risk, enabling improved risk stratification beyond conventional lipid panels [4]. Similarly, in metabolic syndrome and diabetes, distinct lipid signatures reflect underlying insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation, offering potential for early detection and monitoring of intervention responses [23].

The FDA-approved Tina-quant immunoassay for apolipoprotein A-I and B represents a successful example of lipid-related biomarker translation, demonstrating the clinical acceptance of lipid-based assessments when supported by robust validation [4]. This precedent establishes a pathway for more comprehensive lipid panels to eventually enter clinical practice as evidence accumulates.

Table 3: Performance of Lipid Biomarkers in Various Disease Applications

| Disease Area | Biomarker Panel | Performance (AUC) | Sample Type | Study Cohort |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) | PE(14:1/20:0), PE(18:2/16:0), 19-methyl-heneicosanoic acid | 0.88 (training), 0.82 (validation) | Plasma | 106 patients, 108 controls [20] |

| Bladder Cancer (Grading) | Four-lipid panel | 0.815 (10-fold CV: 0.77) | Plasma | 106 NMIBC patients [20] |

| Alzheimer's Disease | Six-lipid panel (from 138 differential lipids) | Superior separation with RCM vs plasma | RBC Membrane & Plasma | 156 individuals [21] |

| Cardiovascular Risk | Ceramides, phosphatidylcholines | Improved risk stratification | Plasma | Multiple cohorts [4] |

Multi-Center Validation: Critical Considerations and Challenges

Standardization and Reproducibility

The transition of lipid biomarkers from research discoveries to clinically useful tools faces several substantial challenges. Reproducibility across platforms and laboratories remains a significant hurdle, with studies reporting alarmingly low agreement rates (14-36%) between different lipidomics platforms when analyzing identical samples [4]. This variability stems from differences in sample preparation protocols, chromatographic separation conditions, mass spectrometry instrumentation, and data processing algorithms [4].

Addressing these challenges requires rigorous standardization of pre-analytical factors including fasting status, time of collection, processing delays, and storage conditions [20] [21]. The implementation of standard reference materials and internal standardization strategies using stable isotope-labeled lipids is essential for quantitative accuracy and cross-laboratory comparability [4]. Additionally, the field would benefit from harmonized data reporting standards that encompass lipid nomenclature, quantification units, and quality control metrics.

Biological and Analytical Complexities

The extraordinary structural diversity of lipids presents both an opportunity and a challenge for biomarker development. While this diversity enables precise disease mapping, it complicates comprehensive analysis and interpretation. The dynamic range of lipid concentrations in biological samples exceeds the detection capabilities of any single analytical platform, necessitating strategic trade-offs between coverage and sensitivity [4].

Biological variability introduced by factors such as diet, circadian rhythms, medications, and gut microbiota further complicates biomarker validation [4]. These confounding influences must be carefully controlled through study design and statistical adjustment to distinguish disease-specific signatures from background noise. The implementation of fasting blood collection in the morning hours, as practiced in multiple cited studies, helps mitigate some sources of variability [20] [21].

Diagram 2: Key challenges in the validation pathway for lipid biomarkers.

Emerging Technologies and Approaches

The future of lipid biomarker development is intrinsically linked to technological advancements and integrated analytical frameworks. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are playing an increasingly important role in deciphering complex lipidomic data, with models such as MS2Lipid demonstrating up to 97.4% accuracy in predicting lipid subclasses [4]. These computational approaches enable more efficient pattern recognition and feature selection from high-dimensional datasets.

The integration of lipidomics with other omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) provides a systems biology perspective that enhances biomarker specificity and mechanistic understanding [3] [6]. This multi-omics approach is particularly valuable for addressing the context-dependent nature of lipid alterations and establishing causal relationships between lipid changes and disease processes [4]. Additionally, the exploration of alternative blood compartments such as red blood cell membranes extends the diagnostic potential beyond conventional plasma analysis [21].

Pathway to Clinical Translation

The successful translation of lipid biomarkers into clinical practice requires a coordinated multidisciplinary effort addressing technical, clinical, and regulatory considerations. Large-scale multi-center studies with standardized protocols are essential to establish robust reference ranges and validate performance across diverse populations [4] [24]. The prioritization of biomarkers with clear pathophysiological relevance over those with merely statistical associations will enhance clinical adoption and utility [22].

The evolving regulatory framework for biomarker qualification necessitates early engagement with regulatory agencies to align validation strategies with clinical requirements [22]. The demonstrated success of selected lipid-based tests, such as the FDA-approved apolipoprotein assays, provides a template for this translation process [4]. As evidence accumulates, lipid biomarkers are anticipated to emerge as central elements in personalized medicine, enabling early detection, risk stratification, and targeted therapeutic interventions across a spectrum of human diseases [23].

In conclusion, lipids represent ideal candidates for non-invasive blood-based biomarkers due to their physiological relevance, metabolic responsiveness, and detectable alterations in accessible biofluids. While significant challenges remain in standardization and validation, the strategic integration of advanced analytical platforms, computational methods, and multi-center collaborative research provides a clear pathway for clinical translation. As the field matures, lipid biomarkers are poised to make substantial contributions to precision medicine, fundamentally enhancing our approach to disease detection, monitoring, and management.

Methodological Workflow: Integrating Lipidomics and Machine Learning for Biomarker Discovery

Strategic Application of Untargeted vs. Targeted Lipidomics in Discovery and Validation Phases

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of pathways and networks of cellular lipids, has emerged as a crucial discipline for understanding cellular processes, disease mechanisms, and identifying potential therapeutic targets [25] [26]. In the context of multi-center validation studies for lipidomic biomarkers, the strategic selection of analytical approaches is paramount to generating reliable, reproducible, and clinically relevant data. The lipidome comprises thousands of molecular species with diverse chemical structures and functions, broadly classified by the LIPID MAPS consortium into eight categories: fatty acyls, glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, sterol lipids, prenol lipids, saccharolipids, and polyketides [25] [27]. These molecules regulate critical biological processes including cellular structure, energy storage, signaling, inflammation, and metabolic homeostasis [23] [27].

Two principal methodologies—untargeted and targeted lipidomics—have evolved with complementary strengths and applications in biomarker research. Untargeted lipidomics provides a comprehensive, unbiased analysis of the entire lipid profile, while targeted lipidomics focuses on precise quantification of predefined lipid species [26] [27]. This guide objectively compares these approaches within the framework of discovery and validation research phases, providing experimental data, methodological protocols, and practical considerations for their strategic application in multi-center studies aimed at clinical translation.

Fundamental Methodological Comparisons

Core Analytical Philosophies and Workflows

The fundamental distinction between untargeted and targeted lipidomics lies in their analytical philosophies. Untargeted lipidomics is a discovery-oriented approach that aims to detect and relatively quantify as many lipid species as possible without prior selection, enabling hypothesis generation and novel biomarker discovery [26]. In contrast, targeted lipidomics is a hypothesis-driven approach that focuses on precise identification and absolute quantification of specific, predefined lipids, typically employing internal standards for accurate measurement [26] [28]. This methodological divergence creates complementary applications: untargeted methods excel in comprehensive profiling and novel discoveries, while targeted approaches provide rigorous validation and precise quantification essential for clinical application [27].

The workflow for both approaches begins with careful sample preparation but diverges significantly in data acquisition and analysis. Untargeted workflows typically involve liquid chromatography (LC) separation followed by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) detection, generating complex datasets requiring sophisticated bioinformatics processing [29]. Targeted methods often employ differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) or LC separation coupled with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on triple quadrupole instruments, producing more focused datasets with streamlined analysis [30] [27].

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Untargeted and Targeted Lipidomics Approaches

| Parameter | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Philosophy | Discovery-oriented, unbiased | Hypothesis-driven, focused |

| Primary Instrumentation | LC-HRMS (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) | LC-MS/MS (QQQ), Lipidyzer platform |

| Quantification Approach | Relative quantification (peak areas) | Absolute quantification with internal standards |

| Lipid Identification | Based on m/z, retention time, fragmentation spectra | Predefined transitions with authentic standards |

| Typical Coverage | Hundreds to thousands of features | Dozens to hundreds of predefined lipids |

| Data Complexity | High, requiring advanced bioinformatics | Moderate, with more straightforward processing |

| Ideal Application Phase | Discovery, hypothesis generation | Validation, clinical application |

| Throughput | Moderate (longer chromatographic separations) | High (streamlined methods) |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics from Comparative Studies

| Performance Metric | Untargeted LC-MS | Targeted Lipidyzer Platform |

|---|---|---|

| Median Intra-day Precision (CV%) | 3.1% | 4.7% |

| Median Inter-day Precision (CV%) | 10.6% | 5.0% |

| Technical Repeatability (Median CV%) | 6.9% | 4.7% |

| Median Accuracy | 6.9% | 13.0% |

| Correlation Between Platforms (Median r) | 0.71 (for commonly detected lipids) | 0.71 (for commonly detected lipids) |

| Lipid Coverage in Mouse Plasma | 337 lipids across 11 classes | 342 lipids across 11 classes |

| Overlap Between Platforms | 196 lipid species (35% of untargeted detections) | 196 lipid species (57% of targeted detections) |

Data derived from a cross-platform comparison study analyzing aging mouse plasma [30]. The correlation was calculated for lipids detected by both platforms using endogenous plasma lipids in the context of aging.

Experimental Designs and Protocol Specifications

Untargeted Lipidomics Workflow

Untargeted lipidomics employs a comprehensive analytical workflow designed to capture the broadest possible lipid profile:

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Extraction: Lipids are extracted from biological matrices (plasma, tissue, cells) using organic solvents such as chloroform-methanol or methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) mixtures [26] [29]. The classic Folch or Bligh-Dyer methods are commonly employed.

- Internal Standards: Addition of isotope-labeled internal standards early in the process enables quality control and normalization. Standards should cover multiple lipid classes to account for extraction efficiency variations [29].

- Quality Controls: Preparation of pooled quality control (QC) samples from all study samples is essential for monitoring instrument performance and data quality throughout the analysis [29].

Chromatographic Separation:

- Reversed-Phase LC: Most commonly used for separating lipid species by hydrophobicity, effectively resolving molecular species within the same lipid class [30] [29].

- HILIC Chromatography: Useful for separating lipids by class based on polar head groups.

- Optimized Conditions: Typical UHPLC methods use C8 or C18 columns with acetonitrile-water mobile phases containing ammonium formate/acetate modifiers, with run times of 15-30 minutes per sample [29].

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- High-Resolution MS: Quadrupole time-of-flight (Q-TOF) or Orbitrap mass analyzers provide accurate mass measurements (<5 ppm mass error) for confident lipid identification [27] [29].

- Data Acquisition: Both data-dependent acquisition (DDA) and data-independent acquisition (DIA) modes are employed, with DDA providing MS/MS spectra for structural elucidation of the most abundant ions, while DIA fragments all ions simultaneously [27].

- Ionization Modes: Both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes are typically required to cover the diverse lipidome [29].

Data Processing and Lipid Identification:

- Peak Detection and Alignment: Software tools (e.g., XCMS, MS-DIAL) detect chromatographic peaks and align them across samples [29].

- Lipid Identification: Matching of accurate mass, isotopic patterns, retention time, and MS/MS fragmentation spectra against lipid databases (LIPID MAPS, HMDB) [26].

- Statistical Analysis: Multivariate statistics (PCA, PLS-DA) and univariate analyses identify lipids differentially abundant between experimental groups [29].

Targeted Lipidomics Workflow

Targeted lipidomics employs a focused approach designed for precise quantification:

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Extraction: Similar extraction protocols as untargeted approaches, but with emphasis on reproducibility and recovery of specific lipid classes of interest [30].

- Comprehensive Internal Standardization: Addition of multiple stable isotope-labeled internal standards (typically 50+ IS covering all targeted lipid classes) to correct for extraction efficiency, matrix effects, and instrument variability [30] [28].

- Calibration Curves: For absolute quantification, calibration curves with authentic standards are prepared in matching matrix [28].

Lipid Separation and Detection:

- DMS and LC Separation: Some targeted platforms (e.g., Lipidyzer) incorporate differential mobility spectrometry (DMS) for lipid class separation, while others use conventional LC separation [30].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Triple quadrupole instruments operating in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode provide high sensitivity and specificity for predefined lipid transitions [30] [27].

- Optimized Transitions: Pre-optimized precursor-product ion transitions for each targeted lipid ensure selective detection and accurate quantification [30].

Data Processing and Quantification:

- Peak Integration: Automated integration of chromatographic peaks for each targeted transition.

- Concentration Calculation: Lipid concentrations calculated based on internal standard response and calibration curves, reported in absolute quantities (nmol/g or μM) [30] [28].

- Quality Assessment: Monitoring of internal standard response and QC sample performance throughout the analysis.

Comparative Performance in Biomarker Research

Lipid Coverage and Complementarity

Direct comparative studies reveal both overlapping and complementary coverage between untargeted and targeted approaches. In a cross-platform comparison using aging mouse plasma, untargeted LC-MS detected 337 lipids across 11 classes, while the targeted Lipidyzer platform detected 342 lipids across similar classes [30]. However, the overlap was only 196 lipid species, representing just 35% of untargeted detections and 57% of targeted detections, highlighting their complementary nature [30].

Each approach offers distinct advantages for specific lipid classes. Untargeted methods better capture ether-linked phospholipids (plasmalogens) and phosphatidylinositols, while targeted approaches excel at detecting free fatty acids and cholesterol esters [30]. For triacylglycerol (TAG) speciation, untargeted LC-MS provides identification of all three fatty acyl chains (e.g., TAG(16:0/18:1/18:2)), while targeted platforms typically report total carbon number and unsaturation (e.g., TAG52:3-FA16:0) [30].

The combined application of both approaches significantly expands lipid coverage, with one study demonstrating 700 unique lipid molecular species detected in mouse plasma when integrating data from both platforms [30]. This complementarity is particularly valuable in discovery phases where comprehensive lipidome assessment is critical.

Quantitative Performance and Reproducibility

Quantitative performance metrics demonstrate specific strengths for each approach. Targeted lipidomics generally shows superior precision, with median inter-day CV of 5.0% compared to 10.6% for untargeted methods, and technical repeatability of 4.7% versus 6.9% [30]. This enhanced precision makes targeted approaches particularly valuable for longitudinal studies and clinical applications where detecting subtle changes is essential.

Untargeted methods demonstrated slightly better accuracy (6.9% vs 13.0%) in spiked recovery experiments, though targeted accuracy improved to comparable levels when excluding the highest concentration samples where signal plateau was observed [30]. This highlights the importance of maintaining calibration within linear dynamic ranges for targeted quantification.

Correlation between platforms is strong for quantitative measurements, with a median correlation coefficient of 0.71 for endogenous plasma lipids in aging studies [30]. This supports the practice of using untargeted discovery followed by targeted validation, as quantitative patterns are generally conserved between platforms.

Strategic Implementation in Multi-Center Studies

Integrated Workflow for Biomarker Discovery and Validation