Multi-Omics Profiling for Biomarker Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Integrating Data, Overcoming Challenges, and Driving Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of multi-omics profiling for biomarker discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Multi-Omics Profiling for Biomarker Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Integrating Data, Overcoming Challenges, and Driving Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of multi-omics profiling for biomarker discovery, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles and unique value proposition of moving beyond single-omics approaches to gain a holistic view of disease biology. The piece delves into advanced methodological strategies, including single-cell resolution, various data integration techniques, and their specific applications in target identification and patient stratification. A dedicated section addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization needs, focusing on managing data heterogeneity, computational demands, and analytical standardization. Finally, the article guides readers through the essential processes of biomarker validation, clinical translation, and comparative analysis against traditional methods, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for the field.

Beyond Single-Omics: Foundational Principles for a Holistic View of Disease Biology

Multi-omics represents a transformative approach in biological research that integrates data from multiple "omes" – such as the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome – to create a comprehensive understanding of biological systems. This paradigm moves beyond traditional single-omics approaches that studied biological layers in isolation, instead recognizing that life functions through dynamic, interconnected molecular networks. Historically, researchers focused on individual biological components, similar to trying to understand a symphony by listening to just one instrument [1]. While these studies provided valuable insights, they offered limited perspective on the complex interactions governing cellular processes. Multi-omics integration addresses this limitation by combining diverse molecular datasets to reveal the complete flow of information from genes to observable traits, thereby enabling a more holistic investigation of biological phenomena, particularly in biomarker discovery for precision medicine [1] [2].

The technological landscape has evolved significantly to support this integrated approach. Advanced technologies including next-generation sequencing (NGS), mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and non-invasive imaging modalities have made it possible to generate massive, high-dimensional molecular datasets from single experiments [3] [4]. Concurrently, breakthroughs in computational biology and machine learning have provided the necessary tools to integrate and analyze these complex datasets. This convergence of technological capabilities has positioned multi-omics as a powerful framework for unraveling complex biological mechanisms, with particular relevance for identifying robust biomarkers, understanding disease pathogenesis, and developing targeted therapeutic interventions [3] [2].

The Multi-Omics Toolkit: Core Components and Technologies

Fundamental Omes and Their Relationships

A multi-omics approach incorporates several core molecular layers, each providing unique insights into biological systems. The foundational layer, genomics, involves studying the complete set of DNA in an organism, including structural variations and mutations that may predispose individuals to diseases. It provides the fundamental blueprint of life but offers a largely static picture of biological potential [1]. Epigenomics examines heritable changes in gene expression that do not alter the underlying DNA sequence, primarily through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and chromatin accessibility. This regulatory layer serves as a critical interface between environmental influences and genomic responses [1].

The dynamic expression of genetic information is captured through transcriptomics, which analyzes the complete set of RNA transcripts in a cell at a specific point in time. This layer reveals which genes are actively being expressed and at what levels, providing a snapshot of cellular activity [1]. Proteomics extends this understanding by investigating the complete set of proteins, including their abundances, modifications, and interactions. As the functional effectors within cells, proteins represent the actual machinery executing biological processes [1]. Finally, metabolomics focuses on the comprehensive analysis of small-molecule metabolites, which represent the ultimate downstream product of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic activity. The metabolome provides the closest link to phenotype and offers real-time insights into cellular physiology [1].

Experimental Platforms and Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Technology Category | Specific Platforms/Reagents | Primary Function | Key Applications in Multi-Omics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Isolation | Various commercial kits | High-quality nucleic acid extraction | Foundation for genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic analyses |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep, Single Cell 3' RNA Prep, Stranded mRNA Prep | Library construction for NGS | Preparing samples for sequencing across different molecular layers |

| Sequencing Platforms | NovaSeq X Series, NextSeq 1000/2000, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing | Generating genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data |

| Proteomics Technologies | Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), CITE-seq | Protein identification and quantification | Integrating protein expression data with transcriptomic information |

| Spatial Technologies | Spatial transcriptomics platforms | Tissue context preservation | Mapping molecular data to tissue architecture |

| Single-Cell Technologies | 10x Genomics, scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq | Single-cell resolution profiling | Resolving cellular heterogeneity in multi-omics datasets |

Next-generation sequencing platforms form the backbone of modern multi-omics research, enabling comprehensive profiling of DNA, RNA, and epigenetic modifications. Illumina's sequencing systems, including the production-scale NovaSeq X Series and benchtop NextSeq models, provide flexible solutions for various throughput needs [4]. For proteomic integration, mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) remains the primary technology for large-scale protein identification and quantification, while emerging sequencing-based proteomic methods like CITE-seq (Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing) enable simultaneous measurement of protein abundance and gene expression in single cells [1] [4].

The field has increasingly moved toward higher-resolution technologies, particularly single-cell and spatial multi-omics platforms. Single-cell technologies such as scRNA-seq (single-cell RNA sequencing) and scATAC-seq (single-cell Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin by sequencing) resolve cellular heterogeneity by profiling individual cells rather than bulk tissue samples [1]. Spatial multi-omics technologies, including various spatial transcriptomics platforms, preserve the architectural context of cells within tissues, enabling researchers to study how cellular neighborhoods influence function and disease progression [1] [4]. These technological advances have been recognized as transformative, with spatial multi-omics named among "seven technologies to watch" by Nature in 2022 [1].

Multi-Omics Data Integration: Methodologies and Computational Frameworks

Data Integration Approaches and Challenges

Multi-omics data integration faces several computational challenges due to the high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, and technical variability inherent in different molecular datasets. The "curse of dimensionality" presents a particular obstacle, where datasets may contain hundreds of samples but thousands or even millions of features across different molecular layers [5]. Additional complications include batch effects, platform-specific technical artifacts, missing data, and the complex statistical distributions characterizing different data types [6] [5].

Integration methods can be broadly categorized into multi-staged and meta-dimensional approaches. Multi-staged integration employs sequential steps to combine two data types at a time, such as integrating gene expression data with protein abundance measurements before associating these with clinical phenotypes [5]. In contrast, meta-dimensional approaches attempt to incorporate all data types simultaneously, often using multivariate statistical models or machine learning algorithms to identify patterns across multiple molecular layers [5]. The choice between these strategies depends on the specific biological question, sample characteristics, and data quality considerations.

Computational Tools and Workflow Protocols

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods and Applications

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Key Features | Suitable Data Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical Integration | Seurat WNN, Multigrate, Matilda | Integrates multiple modalities from the same cells | Paired RNA+ADT, RNA+ATAC, RNA+ADT+ATAC |

| Matrix Factorization | MOFA+ | Identifies latent factors across omics layers | All major omics data types |

| Deep Learning | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Handles non-linear relationships, missing data | Heterogeneous multi-omics datasets |

| Network-Based | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) | Combines similarity networks from different data types | mRNA-seq, miRNA-seq, methylation data |

| Diagonal Integration | INTEGRATE (Python) | Aligns datasets with only partially overlapping features | Mixed omics datasets with sample mismatch |

| Statistical Framework | mixOmics (R) | Provides diverse multivariate analysis methods | Cross-omics correlation studies |

A representative protocol for multi-omics integration begins with comprehensive data preprocessing and quality control. This critical first step includes normalizing data to account for technical variations, converting data to comparable scales or units, removing technical artifacts, and filtering low-quality data points [7] [8]. For sequencing-based data, primary analysis converts raw signal data into base sequences, while secondary analysis involves alignment, quantification, and quality assessment [4]. Tools such as Illumina's DRAGEN platform provide optimized workflows for these processing steps. Quality metrics must be assessed for each data type individually before integration – for transcriptomic data, this includes examining read depth, mapping rates, and sample-level clustering; for proteomic data, intensity distributions and missing value patterns require evaluation [5].

Following quality control, data harmonization and standardization ensure cross-platform and cross-study comparability. This process involves mapping data to common ontologies, correcting for batch effects, and transforming data into compatible formats [7] [8]. Specific techniques include quantile normalization, cross-platform normalization, and combat batch correction. For particularly heterogeneous datasets, transformation to rank-based measures can help mitigate technical variations [8]. The preprocessed and harmonized data then undergoes integrative analysis using methods appropriate to the research question. For biomarker discovery, network-based approaches such as Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) have proven effective, creating patient similarity networks for each data type and then fusing them to identify robust molecular patterns [9]. For disease subtyping, matrix factorization methods like MOFA+ can identify latent factors that capture coordinated variation across different molecular layers [6].

Validation represents the final critical step in multi-omics integration protocols. A key method for assessing integration quality involves evaluating whether the integrated data provides improved predictive power or cleaner biological clustering compared to single-omics datasets alone [5]. This may include benchmarking against known biological truths, using cross-validation approaches, or testing associations with external clinical variables. The entire workflow benefits from careful documentation and version control to ensure reproducibility, with both raw and processed data deposited in public repositories where possible [7].

Application in Biomarker Discovery: A Neuroblastoma Case Study

Experimental Design and Workflow

A recent investigation into neuroblastoma (NB), a pediatric cancer characterized by clinical heterogeneity, exemplifies the power of multi-omics approaches in biomarker discovery. This study addressed the need for better prognostic markers beyond the established MYCN amplification marker, which alone provides insufficient predictive power for clinical stratification [9]. Researchers implemented an integrated computational framework incorporating three levels of high-throughput NB data: mRNA-seq, miRNA-seq, and methylation arrays from 99 patients [9].

The analytical workflow began with processing each data type individually, including normalization of expression data and preprocessing of methylation arrays. The team then constructed patient similarity matrices for each molecular layer, capturing patterns of relatedness based on mRNA expression, miRNA expression, and DNA methylation profiles [9]. These distinct similarity networks were integrated using Similarity Network Fusion (SNF), which iteratively combines networks to create a comprehensive fused similarity matrix representing multi-omics relationships [9]. Parameter optimization for the SNF algorithm determined optimal values of T=15 (iteration number), k=20 (nearest neighbors), and α=0.5 (hyperparameter) based on convergence behavior [9].

Following integration, the ranked Similarity Network Fusion (rSNF) method prioritized features from each data type, selecting the top 10% of high-ranking features for further investigation [9]. This process identified 4,679 high-rank genes from mRNA-seq data, 160 high-rank miRNAs from miRNA-seq data, and 37,953 high-rank CpG sites from methylation data (of which 67.8% mapped to 9,099 genes) [9]. Comparative analysis revealed 803 genes that appeared as high-rank in both methylation and mRNA-seq data, designating them as "essential genes" with consistent dysregulation across molecular layers [9].

Network Analysis and Biomarker Validation

The essential genes and high-rank miRNAs were used to construct a regulatory network integrating transcription factor (TF)-miRNA and miRNA-target interactions. Database queries retrieved 255 unique TF-miRNA interactions from TransmiR 2.0 and 161 unique miRNA-target interactions from Tarbase v8.0 [9]. Integration of these interactions produced a comprehensive regulatory network comprising 90 miRNAs, 23 transcription factors, and 199 target genes [9].

Maximal clique centrality (MCC) analysis identified the top 10 hub nodes within this network, representing potential biomarker candidates. These included three transcription factors (MYCN, POU2F2, and SPI1) and seven miRNAs [9]. Survival analysis validated the prognostic value of these candidates, with MYCN, POU2F2, and SPI1 demonstrating significant associations with patient survival (p<0.05) [9]. Further validation using an independent cohort of 498 neuroblastoma patients (GSE62564) confirmed these associations and revealed three additional miRNAs (hsa-mir-137, hsa-mir-421, and hsa-mir-760) with significant prognostic value [9].

This case study illustrates how multi-omics integration can uncover biomarker signatures with stronger predictive power than single-omics approaches. The regulatory network perspective provided mechanistic insights into neuroblastoma pathogenesis while identifying multiple candidate biomarkers for further development and clinical validation.

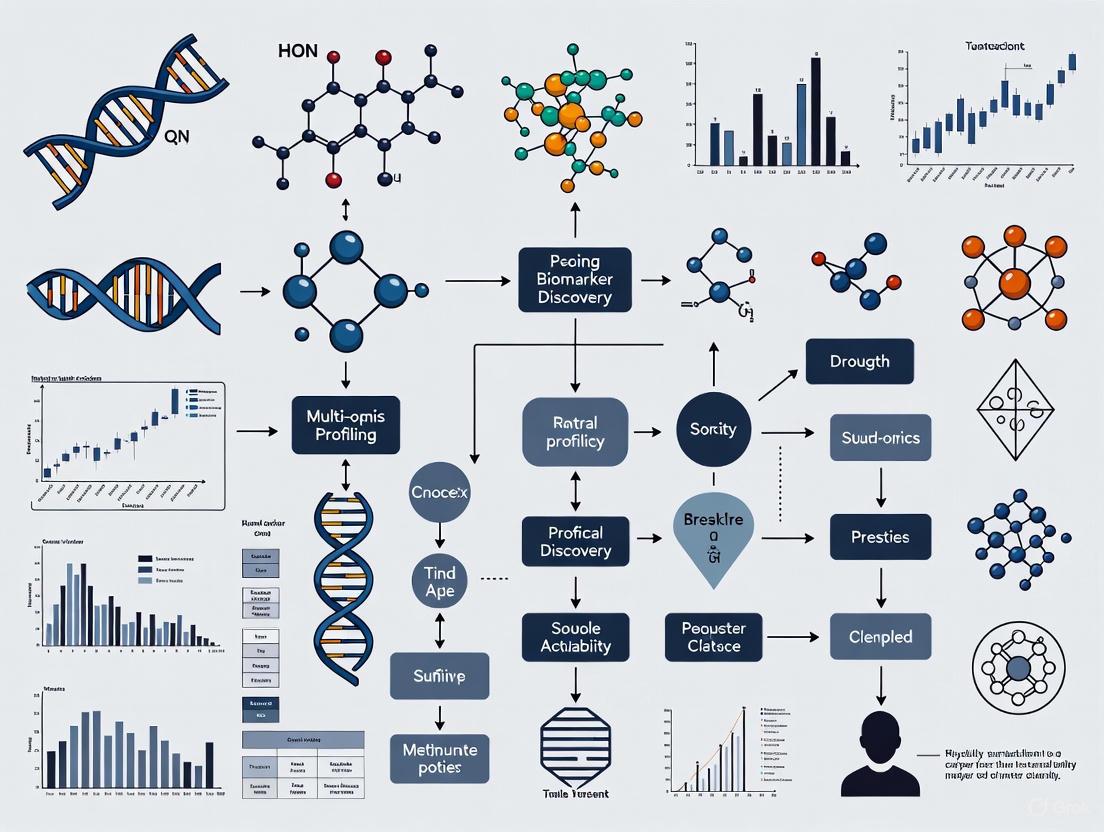

Visualization of Multi-Omics Integration Concepts

From Silos to Integration: A Conceptual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental shift from traditional single-omics approaches to integrated multi-omics analysis, highlighting the workflow from data generation through integration to biological insight:

Multi-Omics Integration Methods Taxonomy

The computational methods for multi-omics integration can be categorized based on their data structure requirements and analytical approaches:

Multi-omics integration represents a fundamental shift in biological research, moving from reductionist approaches to holistic systems-level understanding. This paradigm has demonstrated particular power in biomarker discovery, where it enables identification of robust molecular signatures that account for the complex interplay between different regulatory layers [3] [9] [2]. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data has revealed novel disease mechanisms, enabled more precise patient stratification, and identified potential therapeutic targets across diverse conditions including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and infectious diseases [1] [2].

Future developments in multi-omics research will likely focus on several key areas. Single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies will continue to advance, providing unprecedented resolution for studying cellular heterogeneity and tissue microenvironment effects [1] [10]. Computational methods will evolve to better handle the scale and complexity of multi-omics data, with deep learning approaches such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) playing an increasingly important role in data integration, imputation, and analysis [6]. There will also be growing emphasis on translating multi-omics discoveries into clinical applications, requiring rigorous validation, standardization of analytical protocols, and development of regulatory frameworks for clinical implementation [2].

The ultimate goal of multi-omics research is to enable truly personalized medicine, where therapeutic decisions are guided by comprehensive molecular profiling rather than population-level averages [1] [2]. As technologies mature and analytical methods become more sophisticated, multi-omics approaches will continue to transform our understanding of biological systems and accelerate the development of targeted interventions for complex diseases.

The pursuit of biomarkers for precise disease diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring has long been a cornerstone of biomedical research. Traditional single-omics approaches, focusing on isolated molecular layers such as genomics or proteomics, have provided valuable but limited insights. They often fail to capture the complex, interconnected nature of biological systems, where diseases arise from dynamic interactions across multiple molecular levels [11]. Multi-omics—the integrated analysis of data from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and other domains—represents a paradigm shift. By providing a holistic, systems-level view, multi-omics enables the discovery of complex biomarker signatures that more accurately reflect disease mechanisms and patient-specific variations [12] [13]. This Application Note details the experimental protocols, data integration strategies, and analytical tools required to effectively leverage multi-omics for uncovering these sophisticated biomarker patterns, framed within the broader context of advancing biomarker discovery research.

Key Multi-Omics Technologies and Their Applications in Biomarker Discovery

The integration of diverse omics technologies is fundamental to constructing comprehensive biomarker profiles. Each technology layer contributes unique insights into biological systems, and their convergence is critical for a complete picture.

Core Omics Layers

- Genomics: Interrogates the static DNA blueprint, identifying genetic variations, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and mutations associated with disease predisposition and progression. Advancements in sequencing technologies have revealed approximately 6,000 genes linked to around 7,000 disorders, providing a critical foundation for biomarker discovery [11].

- Transcriptomics: Analyzes the dynamic expression of RNA transcripts, revealing how genes are regulated in different states, tissues, and in response to treatments. It helps identify differentially expressed genes and splicing variants that serve as potential biomarkers.

- Proteomics: Identifies and quantifies the entire complement of proteins, the primary functional executors in the cell. Proteomics biomarkers, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and various matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), have proven valuable in understanding processes like tissue repair and regeneration [13].

- Metabolomics: Focuses on small-molecule metabolites, the end products of cellular processes, providing a direct readout of cellular activity and physiological status. Metabolomics techniques like NMR and mass spectrometry have shown potential in tracking energy metabolism and oxidative stress in real-time [13].

Advanced Profiling Technologies

The transition from bulk analysis to single-cell multi-omics is a pivotal trend. This approach allows researchers to correlate specific genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic changes within individual cells, uncovering cellular heterogeneity that is masked in bulk analyses [11]. This is particularly crucial for understanding complex microenvironments, such as those found in tumors.

Furthermore, liquid biopsies have emerged as a powerful, non-invasive tool for biomarker discovery and monitoring. By analyzing biomarkers like cell-free DNA (cfDNA), RNA, proteins, and metabolites from biofluids, liquid biopsies facilitate real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment responses. While initially prominent in oncology, their application is expanding into infectious and autoimmune diseases [12] [11].

Table 1: Core Omics Technologies for Biomarker Discovery

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Key Technologies | Contribution to Biomarker Signatures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence and variation | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Targeted Panels | Identifies hereditary risk factors and somatic mutations driving disease. |

| Transcriptomics | RNA expression and regulation | RNA-seq, Single-Cell RNA-seq | Reveals active pathways and regulatory responses to disease and treatment. |

| Proteomics | Protein identity, quantity, and modification | Mass Spectrometry, Immunoassays | Discovers functional effectors and therapeutic targets; often has high clinical translatability. |

| Metabolomics | Small-molecule metabolites | NMR Spectroscopy, Mass Spectrometry | Provides a snapshot of functional phenotype and metabolic dysregulation. |

Integrated Experimental Protocol for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

The following protocol outlines a standardized workflow for a multi-omics study designed to identify biomarker signatures for patient stratification.

Sample Collection and Preparation

- Cohort Selection: Define clear patient cohorts (e.g., disease vs. healthy, treatment responders vs. non-responders). Engage diverse populations to ensure biomarker applicability across demographics [11]. Secure ethical approval and informed consent, emphasizing data usage [12].

- Sample Acquisition:

- Collect tissue biopsies (snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen) and/or biofluids (blood, plasma, serum, CSF) as appropriate.

- For blood-based liquid biopsies, collect blood in EDTA or Streck tubes, process plasma within 2 hours of collection by double-centrifugation, and store all aliquots at -80°C.

- Parallel Nucleic Acid and Protein Extraction:

- Use a portion of the sample (tissue homogenate or plasma) for simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction using a commercial kit (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Kit) to ensure co-analysis from the same source.

- Use a separate aliquot for protein extraction using RIPA buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

Multi-Omics Data Generation

Perform the following assays in parallel on the same sample set:

Genomics:

- Perform Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) on extracted DNA. Use a platform such as Illumina NovaSeq X Plus to achieve a minimum 30x coverage.

- Process: Fragment DNA → library preparation → sequencing.

Transcriptomics:

- Perform total RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on extracted RNA. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 8). Use Illumina NovaSeq 6000 for a minimum of 40 million paired-end reads per sample.

- Process: Deplete ribosomal RNA → library preparation → sequencing.

Proteomics:

- Perform data-independent acquisition (DIA) mass spectrometry on extracted proteins.

- Process: Digest proteins with trypsin → desalt peptides → analyze by LC-MS/MS (e.g., Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer).

Metabolomics:

- Perform untargeted metabolomics via liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Process: Deproteinize plasma with cold methanol → analyze by LC-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes.

Data Integration and Computational Analysis

Preprocessing and Quality Control:

- Process each omics dataset through standardized pipelines (e.g., GATK for WGS, STAR for RNA-seq, DIA-NN for proteomics, XCMS for metabolomics).

- Perform rigorous QC and normalize data within each platform.

Network Integration and Multi-Omics Analysis:

- Step 1: Map multiple omics datasets onto shared biochemical networks based on known interactions (e.g., transcription factor to transcript, enzyme to metabolite) [11].

- Step 2: Use multi-omics factorization models (e.g., MOFA+) to identify latent factors that capture shared variation across all data types and differentiate sample groups.

- Step 3: Apply machine learning (e.g., random forest, penalized regression) on the integrated dataset to build a predictive model of disease state or treatment response. The model will identify a panel of features (e.g., a mutation, a gene expression level, a protein abundance) that constitute the biomarker signature.

Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful multi-omics biomarker discovery relies on a suite of reliable reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category / Item | Function in Workflow | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | ||

| AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit | Simultaneous purification of genomic DNA, total RNA, and miRNA from a single sample. | Ensures all nucleic acid data originates from the same sample aliquot, reducing technical variability for integrated genomics/transcriptomics. |

| Proteomics & Metabolomics | ||

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | Efficient extraction of total protein from cells and tissues. | Prepares protein lysates for subsequent digestion and mass spectrometry analysis. |

| Trypsin, Proteomics Grade | Specific enzymatic digestion of proteins into peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis. | Standardized protein digestion is critical for reproducible peptide identification and quantification. |

| Sequencing & Library Prep | ||

| Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep | Library preparation for Whole Genome Sequencing, minimizing amplification bias. | Generates high-quality sequencing libraries for accurate variant calling in biomarker discovery. |

| Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep | Library preparation for RNA-seq that retains strand information. | Allows for accurate transcriptome mapping and identification of differentially expressed genes. |

| Computational Tools | ||

| MOFA+ (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) | Integrates multiple omics data types to identify the principal sources of variation. | Discovers latent factors that drive differences between patient groups (e.g., responders vs. non-responders) [11]. |

| Artificial Intelligence (AI) Platforms | Analyzes complex, high-dimensional datasets to detect patterns and predict outcomes. | Identifies intricate patterns and interdependencies within integrated omics data for predictive biomarker modeling [11] [14]. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The transition from raw multi-omics data to biological insight requires sophisticated computational approaches.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and machine learning are indispensable for analyzing the large, complex datasets generated by multi-omics studies. These technologies excel at detecting intricate patterns and interdependencies that would be impossible to derive from single-analyte studies [11] [14].

- Predictive Modeling: Machine learning models, such as random forests and support vector machines, can be trained on integrated multi-omics data to predict disease progression, drug efficacy, and patient outcomes [11]. For example, neural networks and transformers can integrate diverse data types like genomics, proteomics, and clinical records to identify diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers across oncology, neurological disorders, and other fields [14].

- Feature Selection: A key outcome of these models is the identification of the most informative features from the vast omics dataset. This results in a shortlist of molecules—a multi-omics biomarker signature—that drives the predictive power of the model.

Overcoming Data Heterogeneity

A significant challenge in multi-omics is harmonizing data from different laboratories and cohorts. An optimal integrated approach interweaves omics profiles into a single dataset prior to high-level analysis, improving statistical power when comparing sample groups [11]. Techniques like data harmonization are critical for unifying disparate datasets to generate a cohesive understanding of biological processes [11].

Table 3: Key Biomarker Validation Metrics and Target Values

| Validation Metric | Description | Target Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected. | < 1% false-negative rate |

| Analytical Specificity | The ability to correctly identify the analyte without cross-reactivity. | < 1% false-positive rate |

| AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) | Overall measure of the biomarker's ability to discriminate between groups. | > 0.85 |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Probability that subjects with a positive test truly have the disease. | > 90% |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Probability that subjects with a negative test truly do not have the disease. | > 90% |

Visualization of Multi-Omics Data Integration Logic

The conceptual framework for integrating disparate omics data into a coherent biomarker signature is outlined below. This process transforms raw data into clinically actionable insights through sequential layers of analysis.

Multi-Omics Data Integration Logic

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics represents a paradigm shift in biomarker discovery research. This multi-omics approach provides a systematic framework for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of the complex molecular and cellular processes in diseases and physiological responses [13]. By combining data from these complementary biological layers, researchers can move beyond isolated measurements to uncover comprehensive biological signatures that capture the true complexity of disease mechanisms, particularly in areas like cancer research and tissue repair [15]. The fundamental premise is that while each omics layer provides valuable insights, their integration reveals interconnected networks and pathways that would remain hidden when these disciplines are studied in isolation [16].

The central dogma of molecular biology provides the logical framework for multi-omics integration, with information flowing from DNA (genomics) to RNA (transcriptomics) to proteins (proteomics) and ultimately to metabolites (metabolomics) [17]. However, multi-omics research acknowledges that this flow is not linear but rather a complex network of regulatory feedback loops and interactions. This holistic perspective is particularly valuable for biomarker discovery, as it allows researchers to identify robust biomarker panels that reflect the underlying biology rather than isolated correlations [3]. The translational potential of this integrated approach is significant, enabling advances in personalized medicine through improved diagnostic accuracy, novel therapeutic targets, and personalized treatment strategies [13].

Omics Layer Specifications and Applications

Table 1: Core Omics Layers in Biomarker Discovery Research

| Omics Layer | Analytical Focus | Key Technologies | Primary Applications in Biomarker Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Study of complete sets of DNA and genes [18] | Next-generation sequencing, Sanger sequencing, long-read sequencing (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) [16] | Identification of inherited health risks, genetic mutations in cancer, diagnosis of hard-to-diagnose conditions [18] |

| Transcriptomics | Complete collection of RNA molecules in a cell [18] | RNA sequencing, single-cell RNA-seq, microarrays | Gene expression profiling, measurement of gene expression in live cells, identification of expression changes in early disease states [18] |

| Proteomics | Comprehensive study of expressed proteins and their functions [18] | Mass spectrometry, NMR, protein microarrays [13] | Diagnosis of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, kidney diseases; understanding protein functions and interactions [18] |

| Metabolomics | Complete set of low molecular weight metabolites [18] | NMR, mass spectrometry, spectroscopy [13] | Tracking energy metabolism, oxidative stress; identifying metabolic changes in obesity, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases [13] [18] |

Table 2: Biomarker Classes and Multi-Omics Applications

| Biomarker Class | Definition | Multi-Omics Application | Example Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Biomarkers | Identify the presence and type of cancer [15] | Multi-omics profiling provides specific molecular signatures for accurate diagnosis | TGF-β, VEGF, IL-6 identified via proteomics/transcriptomics [3] |

| Predictive Biomarkers | Forecast patient response to therapeutics [15] | Integration of genomic variants with protein expression data | Spatial distribution patterns of biomarkers in tumor microenvironment [15] |

| Prognostic Biomarkers | Provide insights into cancer progression and recurrence risk [15] | Combined metabolomic and proteomic profiles track disease trajectory | Metabolic switches in tissue repair tracked via metabolomics [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Workflows

Genomics Processing Protocol

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality genomic DNA from tissue or blood samples using standardized extraction kits. Quantify DNA using fluorometric methods and assess quality via agarose gel electrophoresis or Bioanalyzer.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA to appropriate size (300-800 bp) using enzymatic or mechanical shearing. Repair ends, add A-overhangs, and ligate with platform-specific adapters. For Illumina platforms, use sequencing by synthesis technology; for long-read sequencing (PacBio), circularize DNA fragments with hairpin adapters [16].

- Quality Control: Assess library quality and quantity using qPCR and fragment analyzers before sequencing.

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Quality Control: Process raw FASTQ files through FastQC and Trimmomatic to remove adapters and trim low-quality sequences [16].

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome (GRCh38 or T2T-CHM13v2.0) using BWA or Bowtie2 aligners [16].

- Variant Calling: Identify genetic variants using Bcftools mpileup or GATK HaplotypeCaller, following GATK best practices for optimal accuracy [16].

- Annotation and Interpretation: Annotate variants using ANNOVAR or similar tools, focusing on functional consequences and population frequency.

Transcriptomics Processing Protocol

Sample Preparation and Sequencing:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial kits. Preserve RNA integrity (RIN > 8.0) for accurate representation.

- Library Preparation: Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich poly-A mRNA. Reverse transcribe to cDNA, fragment, and add platform-specific adapters. For single-cell applications, utilize barcoding strategies (10X Genomics, Drop-seq).

- Quality Control: Validate library size distribution and quantity using Bioanalyzer and qPCR.

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Preprocessing: Quality check raw reads with FastQC, remove adapters and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt.

- Alignment and Quantification: Align reads to reference transcriptome using STAR or HISAT2, then quantify gene-level counts with featureCounts or similar tools.

- Differential Expression: Identify significantly differentially expressed genes using DESeq2 or edgeR, applying multiple testing correction.

- Pathway Analysis: Conduct functional enrichment analysis using GO, KEGG, or GSEA to identify affected biological pathways.

Proteomics Processing Protocol

Sample Preparation and Mass Spectrometry:

- Protein Extraction: Lyse tissues or cells in appropriate buffer (e.g., RIPA with protease inhibitors). Quantify protein concentration using BCA or Bradford assay.

- Digestion and Cleanup: Reduce disulfide bonds with DTT, alkylate with iodoacetamide, and digest with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio, 16h, 37°C). Desalt peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Separate peptides using nano-flow liquid chromatography (C18 column, 90-minute gradient) and analyze with tandem mass spectrometry (Orbitrap or Q-TOF instruments).

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Peptide Identification: Search MS/MS spectra against protein databases using MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer, or similar platforms.

- Quantification: Apply label-free (MaxLFQ) or isobaric labeling (TMT, iTRAQ) quantification methods. Normalize across samples.

- Statistical Analysis: Identify significantly altered proteins using linear models (limma) with false discovery rate correction.

- Functional Analysis: Conduct pathway enrichment and protein-protein interaction network analysis using STRING or similar resources.

Metabolomics Processing Protocol

Sample Preparation and Analysis:

- Metabolite Extraction: Use methanol:acetonitrile:water (40:40:20) extraction for comprehensive metabolite coverage. For lipidomics, methyl-tert-butyl ether extraction is preferred.

- Quality Control: Include pooled quality control samples and internal standards throughout the analytical run.

- Instrumental Analysis: Utilize either NMR spectroscopy (Bruker, 800 MHz) with NOESY presat pulse sequence or LC-MS (reverse-phase and HILIC chromatography coupled to Q-TOF mass spectrometer).

Data Analysis Workflow:

- Preprocessing: Process raw data using XCMS (LC-MS) or Chenomx (NMR) for peak picking, alignment, and integration.

- Metabolite Identification: Match accurate mass and fragmentation patterns to databases (HMDB, METLIN) with < 5 ppm mass error.

- Statistical Analysis: Apply multivariate statistics (PCA, PLS-DA) and univariate analysis (t-tests with FDR correction) to identify significant metabolites.

- Pathway Analysis: Use MetaboAnalyst for pathway enrichment analysis and visualization of altered metabolic pathways.

Visualization of Multi-Omics Workflows

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

Molecular Biology Workflow in Multi-Omics

Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Kits | Application Function |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA/RNA Kits, TRIzol Reagent | High-quality DNA/RNA isolation preserving molecular integrity for sequencing applications [16] |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA/RNA Prep Kits, Nextera Flex | Preparation of sequencing libraries with minimal bias for genomic and transcriptomic applications [16] |

| Protein Digestion | Trypsin/Lys-C Mix, RapiGest SF Surfactant | Efficient protein digestion for mass spectrometry-based proteomics with minimal losses [13] |

| Metabolite Extraction | Methanol:Acetonitrile:Water (40:40:20), MTBE | Comprehensive metabolite extraction covering polar and non-polar compounds for metabolomics [3] |

| Spatial Biology | 10X Genomics Visium, CODEX/IMC Platforms | Preservation of spatial context in transcriptomics and proteomics within tissue architecture [15] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | 10X Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody | Isolation and barcoding of individual cells for single-cell multi-omics approaches [16] |

| Quality Control | Bioanalyzer/RNA ScreenTapes, Qubit Assays | Assessment of sample quality and quantity throughout multi-omics workflows [16] |

The integration of genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics represents a powerful framework for advancing biomarker discovery research. By systematically combining these complementary omics layers, researchers can move beyond isolated molecular measurements to develop comprehensive biological signatures that truly capture disease complexity [15]. The experimental protocols outlined provide a standardized approach for generating high-quality multi-omics data, while the visualization workflows illustrate the interconnected nature of these biological systems.

Future developments in multi-omics research will likely focus on several key areas. Spatial omics technologies are emerging as crucial tools for understanding tissue architecture and cellular interactions within intact tissues [15]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are becoming essential for analyzing the complex, high-dimensional datasets generated by multi-omics studies [15] [19]. Additionally, the integration of advanced model systems such as organoids and humanized mouse models will enhance the translational relevance of multi-omics biomarker discovery [15]. As these technologies mature, multi-omics approaches will increasingly enable personalized medicine through improved diagnostic accuracy, novel therapeutic targets, and tailored treatment strategies for complex diseases [13] [3].

The transition from a one-size-fits-all medical model to precision healthcare is fundamentally reliant on the comprehensive molecular profiling of individuals. Multi-omics profiling—the integrated analysis of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and other molecular datasets—serves as the cornerstone for this transformation by enabling the discovery of robust biomarkers [20]. These biomarkers are critical for early disease detection, accurate prognosis, and tailoring therapies to individual patient molecular signatures [2]. The clinical imperative is clear: to move beyond traditional, often reactive, diagnostic methods and towards a proactive, personalized paradigm where treatments are informed by a deep, multi-layered understanding of disease biology [21] [22]. This Application Note provides a structured framework for designing and executing multi-omics studies aimed at translating molecular discoveries into clinically actionable insights and targeted therapeutic strategies.

Current Landscape and Clinical Need

Traditional biomarker discovery, often focused on single-omics approaches, has provided valuable but limited insights. For example, genomic studies identified BRCA1 and BRCA2 as critical biomarkers for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk, while proteomics gave us Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer screening, and metabolomics identified Glycated Hemoglobin (HbA1c) for diabetes management [20]. However, complex diseases often arise from dynamic interactions across multiple molecular layers, which single-omics analyses cannot fully capture [20].

Multi-omics integration addresses this limitation by providing a holistic view of biological systems and disease mechanisms. This approach is particularly powerful for:

- Identifying Complex Biomarker Signatures: Diseases often result from intricate interactions among genes, proteins, and metabolites. Multi-omics can uncover composite signatures that are more accurate and reliable than single-molecule biomarkers [20].

- Improving Sensitivity and Specificity: Combining different types of omics data enhances the predictive power of biomarker detection [20].

- Enabling Personalized Medicine: By considering the unique molecular profiles of individual patients, multi-omics facilitates the development of tailored and effective treatment strategies [21] [20].

Major initiatives, such as the Multi-Omics for Health and Disease (MOHD) consortium funded by the NIH, underscore the importance of this approach. The MOHD aims to advance the application of multi-omic technologies in ancestrally diverse populations to define molecular profiles associated with health and disease [23].

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Diagnostics vs. Advantages of Multi-Omics

| Aspect | Traditional Diagnostics | Multi-Omics Profiling |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Focuses on single biomarkers or limited panels (e.g., HbA1c, PSA) [20] | Integrates data from multiple molecular layers (genome, proteome, metabolome, etc.) [21] [20] |

| Early Detection | Often identifies disease after clinical manifestation | Can identify molecular shifts years before clinical symptoms appear (e.g., prediabetes) [21] |

| Personalization | Limited ability to guide targeted therapies | Identifies patient-specific dysregulated pathways for tailored interventions [2] [20] |

| Underlying Biology | Provides a narrow view of disease mechanisms | Reveals interconnected networks and regulatory mechanisms for a holistic understanding [22] [20] |

Multi-Omics Layers and Their Biomarker Potential

A successful multi-omics study leverages complementary data types to build a complete molecular story. The key omics layers and their contributions to biomarker discovery are summarized below.

Table 2: Key Omics Layers in Biomarker Discovery

| Omics Layer | Biomarker Type | Clinical/Research Utility | Common Analysis Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA mutations, Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), Copy Number Variations (CNVs) [24] | Risk assessment, hereditary disease identification, pharmacogenomics [20] | Whole-genome sequencing, SNP microarrays [23] |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression levels, RNA splicing variants, non-coding RNAs [2] | Understanding active disease pathways, patient subtyping, drug response [22] | RNA-Seq, microarrays |

| Proteomics | Protein abundance, post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation) [21] | Direct insight into functional biological states and signaling activity; therapeutic target identification [21] [22] | LC-MS/MS, iTRAQ, antibody arrays [21] |

| Metabolomics | Small-molecule metabolites (sugars, lipids, amino acids) [20] | Real-time snapshot of physiological status, metabolic health, and treatment efficacy [22] | Mass spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications [21] [24] | Assessing environmental influence on gene regulation, early detection of cellular dysregulation [23] | Bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq |

| Microbiomics | Gut microbiota composition and functional capacity [21] | Evaluating impact of microbiome on drug metabolism, immunity, and disease [21] | 16S rRNA sequencing, metagenomic sequencing |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery

Integrated Multi-Omics Workflow for Prediabetes Profiling

This protocol outlines a longitudinal study design to identify biomarkers predicting the transition from normoglycemia to prediabetes, a high-risk state where early intervention can prevent progression to type 2 diabetes [21].

Objective: To discover a composite biomarker signature for early detection of prediabetes and stratification of progression risk by integrating genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data.

Sample Cohort:

- Cohort: 500 participants, aged 30-60, with normoglycemia at baseline.

- Longitudinal Sampling: Blood samples collected at baseline, 12, 24, and 36 months.

- Phenotypic Data: Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), HbA1c, BMI, lifestyle factors [21].

Protocol Steps:

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Collect peripheral blood samples in EDTA tubes.

- Plasma: Isolate via centrifugation (2,000 x g, 10 min, 4°C) for proteomics and metabolomics.

- Buffy Coat: Isolate for genomic DNA extraction.

- Aliquot and store all samples at -80°C.

Genomic Analysis (Baseline):

- DNA Extraction: Use a commercial kit for genomic DNA extraction from leukocytes.

- Genotyping: Perform genome-wide genotyping using a high-density SNP microarray.

- Focus: Identify known and novel genetic variants associated with insulin resistance and beta-cell function [21].

Proteomic Analysis (All Time Points):

- Protein Extraction: Digest plasma proteins with trypsin.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Use liquid chromatography (LC) coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

- Employ isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) for multiplexed protein quantification across patient samples and time points [21].

- Data Output: Relative and absolute quantification of ~1,000 plasma proteins.

Metabolomic Analysis (All Time Points):

- Metabolite Extraction: Precipitate proteins from plasma with cold methanol.

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Perform untargeted metabolomic profiling using high-resolution LC-MS.

- Use both C18 (reverse-phase) and HILIC (hydrophilic interaction) chromatography for comprehensive metabolite separation [22].

- Data Output: Semi-quantitative levels of ~500 named metabolites.

Data Integration and Biomarker Validation:

- Bioinformatics: Use machine learning models (e.g., random forest, neural networks) to integrate genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets [2].

- Objective: Identify a multi-omics signature that predicts progression to prediabetes (defined by ADA criteria: FPG ≥5.6 mmol/L, HbA1c 5.7%-6.4%) [21].

- Validation: Validate the top candidate biomarkers in an independent, ancestrally diverse validation cohort of 200 participants [23].

Protocol for Proteomic Biomarker Discovery Using iTRAQ-LC-MS/MS

This detailed protocol focuses on the proteomic component, a critical layer for understanding functional biology [21].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Protein Digestion:

- Deplete high-abundance plasma proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) using an immunoaffinity column.

- Reduce disulfide bonds with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 60°C for 30 min.

- Alkylate cysteine residues with 15 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) in the dark for 30 min.

- Digest proteins with sequencing-grade trypsin (1:20 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C.

- Desalt the resulting peptides using a C18 solid-phase extraction cartridge and dry in a vacuum concentrator.

iTRAQ Labeling:

- Reconstitute each peptide digest in 20 µL of iTRAQ dissolution buffer.

- Label each sample with a different iTRAQ 8-plex reagent (e.g., patient samples at different time points) by incubating at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Combine all labeled samples into a single tube.

Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry:

- Fractionation: Separate the pooled, labeled peptides using high-pH reverse-phase LC into 20 fractions to reduce complexity.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze each fraction on a Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer coupled to a nanoflow UHPLC system.

- Load peptides onto a trapping column and separate on an analytical C18 column with a 90-min acetonitrile gradient.

- Acquire data in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode: a full MS1 scan (resolution 120,000) followed by MS2 scans (resolution 30,000) of the top 20 most intense precursors.

Data Processing:

- Search MS/MS data against the human Swiss-Prot database using search engines (e.g., MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer).

- Enable iTRAQ 8-plex as a quantification method and carbamidomethylation of cysteine as a fixed modification.

- Apply a false discovery rate (FDR) of <1% at the protein and peptide level.

- Normalize protein reporter ion intensities across all channels and calculate relative protein abundances.

Data Integration and Computational Analysis

The integration of heterogeneous multi-omics datasets is a critical and challenging step [24] [20]. The primary objectives for integration in translational medicine include detecting disease-associated molecular patterns, identifying patient subtypes, and understanding regulatory processes [24].

Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are indispensable for this task. They can analyze large, complex datasets to identify non-linear relationships and patterns that are not apparent through traditional statistical methods [2]. Key techniques include:

- Neural Networks and Deep Learning: For identifying complex, hierarchical patterns across omics layers [2].

- Feature Selection Methods: To prioritize the most informative biomarkers from thousands of molecular features, reducing dimensionality and enhancing model interpretability [2] [20].

- Clustering and Subtype Identification: Unsupervised learning algorithms (e.g., consensus clustering) can discover novel disease subtypes based on integrated molecular profiles, which may have distinct clinical outcomes or drug responses [24].

A significant challenge is data heterogeneity and standardization. Different omics platforms generate diverse data types (e.g., sequences, expression levels, abundances), and a lack of standardized protocols can lead to inconsistencies [20]. Solutions involve using platforms like Polly, which performs numerous quality checks during data harmonization and provides analysis-ready datasets to ensure reproducibility [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| iTRAQ 8-plex Reagents | Multiplexed protein quantification; allows simultaneous analysis of up to 8 samples in a single MS run, reducing technical variability [21]. | Comparative plasma proteomics across patient time points or treatment groups [21]. |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Specific proteolytic enzyme for digesting proteins into peptides for bottom-up proteomics MS analysis [21]. | Sample preparation for LC-MS/MS-based proteomic profiling. |

| High-Abundancy Protein Depletion Column | Removal of highly abundant proteins (e.g., albumin, IgG) from plasma/serum to enhance detection of lower-abundance potential biomarkers [21]. | Pre-fractionation of clinical plasma samples to deepen proteome coverage. |

| DNA/RNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilize nucleic acids in collected blood samples to preserve integrity from sample collection to nucleic acid extraction. | Preserving sample quality for genomic and transcriptomic analyses in longitudinal clinical studies. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Ultra-pure solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) for LC-MS to minimize background noise and ion suppression. | Preparing mobile phases and sample solutions for high-sensitivity metabolomic and proteomic MS. |

| Reference Mass Calibration Kits | Calibration of mass spectrometers to ensure mass accuracy and reproducibility of MS and MS/MS measurements over time. | Routine instrument calibration for large-scale proteomic or metabolomic profiling campaigns. |

The integration of multi-omics data is no longer a niche research activity but a clinical imperative for advancing personalized medicine. Through carefully designed experimental protocols, robust computational integration, and rigorous validation, researchers can translate complex molecular measurements into actionable biomarker signatures. These signatures hold the power to redefine disease classification, predict therapeutic response, and ultimately deliver on the promise of targeted therapies tailored to an individual's unique molecular profile. As technologies mature and AI-driven integration becomes more sophisticated, multi-omics will undoubtedly become a standard pillar in the diagnosis and treatment of disease, shifting the healthcare paradigm from reactive to proactive and precise.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications: From Single-Cell Resolution to Drug Discovery

Single-cell multi-omics and spatial profiling technologies represent a paradigm shift in biomedical research, moving beyond bulk tissue analysis to reveal cellular heterogeneity, spatial organization, and molecular interactions at unprecedented resolution. These advances are revolutionizing biomarker discovery by enabling the identification of novel cellular subtypes, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic targets within complex tissues [25] [26]. The integration of multimodal data—including transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and spatial information—provides a comprehensive view of cellular states and functions, capturing the complex molecular interplay underlying health and disease [26]. This technological progress is particularly valuable for drug discovery and development, offering powerful tools to understand disease heterogeneity, drug resistance mechanisms, and treatment responses [27] [28]. As these technologies continue to evolve, they are poised to transform precision medicine by facilitating earlier disease detection, more precise patient stratification, and the development of targeted therapeutic interventions.

Core Technological Platforms

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Methodologies

Single-cell multi-omics technologies enable the simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular layers within individual cells, providing unprecedented insights into cellular heterogeneity and function. These approaches have evolved from conventional single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to sophisticated multimodal assays that capture complementary biological information.

Table 1: Single-Cell Multi-Omics Technologies and Applications

| Technology | Measured Modalities | Key Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CITE-seq | RNA + Surface Proteins | Immune cell profiling, cell type annotation | [25] |

| SHARE-seq | RNA + Chromatin Accessibility | Gene regulatory networks, epigenetic regulation | [10] |

| TEA-seq | RNA + Protein + Chromatin | Multimodal cell typing, signaling pathways | [10] |

| scTCR-seq/scBCR-seq | RNA + Immune Repertoire | Adaptive immune responses, clonal expansion | [25] |

| scPairing | Data Integration & Generation | Multimodal data imputation, cross-modality relationships | [29] |

Conventional scRNA-seq technologies, utilizing microfluidic chips, microdroplets, or microwell-based approaches, have fundamentally transformed our understanding of cellular diversity [25]. The standard workflow involves preparing single-cell suspensions, isolating individual cells, capturing mRNA, performing reverse transcription and amplification, and constructing sequencing libraries. Bioinformatic analysis through tools like Seurat and Scanpy enables quality control, dimension reduction, cell clustering, and differential expression analysis, revealing distinct cell populations and their functional states [25].

The emergence of single-cell multi-omics technologies addresses the limitation of measuring only one molecular modality by simultaneously capturing various data types from the same cell. For instance, the combination of scRNA-seq with single-cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (scATAC-seq) provides insights into chromatin accessibility and identifies active regulatory sequences and potential transcription factors [25]. Similarly, cellular indexing of transcriptomes and epitopes by sequencing (CITE-seq) enables the integrated profiling of transcriptome and proteome, revealing both concordant and discordant relationships between RNA and protein expression [25]. These advanced methodologies effectively capture the multidimensional aspects of single-cell biology, including transcriptomes, immune repertoires, epitopes, and other omics data in diverse spatiotemporal contexts.

Spatial Profiling Technologies

Spatial transcriptomics (ST) has emerged as a revolutionary approach that preserves the architectural context of cells within tissues, combining traditional histology with high-throughput RNA sequencing to visualize and quantitatively analyze the transcriptome with spatial distribution in tissue sections [27]. This technology overcomes a critical limitation of conventional single-cell sequencing, where cell dissociation leads to the complete loss of positional information essential for understanding tissue microenvironment and cell-cell interactions.

Table 2: Spatial Transcriptomics Technologies Comparison

| Method | Year | Resolution | Probes/Approach | Sample Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visium | 2018 | 55 µm | Oligo probes | FFPE, Frozen tissue | Commercial platform, high throughput |

| Slide-seqV2 | 2021 | 10-20 µm | Barcoded beads | Fresh-frozen tissue | High resolution, detects low-abundance transcripts |

| MERFISH | 2015 | Single-cell | Error-robust barcodes | Fixed cells | High multiplexing, error correction |

| Xenium | 2022 | Subcellular (<10 µm) | Padlock probes | Fresh-frozen tissue | High sensitivity, customized gene panels |

| Stereo-seq | 2022 | Subcellular (<10 µm) | Expansion microscopy | Fresh-frozen tissue | 3D imaging capability |

Spatial transcriptomics technologies can be broadly categorized into two main approaches: in situ capture (ISC) and imaging-based methods. ISC techniques, such as the original ST method and Slide-seq, involve in situ labeling of RNA molecules within tissue sections using spatial barcodes before library preparation, followed by sequencing and spatial mapping [27]. Imaging-based approaches, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) methods like MERFISH and seqFISH, utilize multiplexed imaging to directly visualize and quantify RNA molecules within their native tissue context [27]. Each platform offers distinct advantages in resolution, throughput, and multiplexing capability, enabling researchers to select the most appropriate technology for their specific research questions and sample types.

The rapid evolution of spatial technologies is evidenced by steady improvements in spatial resolution, from the initial 100 µm spot diameter to current subcellular resolution (<10 µm) achieved by platforms like Xenium and Stereo-seq [27]. This enhanced resolution enables the identification of distinct cell types and states within complex tissues and reveals subtle spatial patterns and gradients of gene expression that underlie tissue organization and function.

Experimental Protocols

Standardized Workflow for Spatial Transcriptomics

Implementing a robust, reproducible workflow is essential for successful spatial biology studies, particularly in biomarker discovery and drug development applications. The following protocol outlines key steps for spatial transcriptomic analysis using current platforms:

Tissue Preparation and Preservation

- Collect fresh tissue samples and immediately embed in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound or freeze in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane

- For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, fix tissues in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours before processing

- Section tissues at 5-10 µm thickness using a cryostat (frozen) or microtome (FFPE)

- Mount sections onto specific spatial gene expression slides compatible with the chosen platform

- Store slides at -80°C (frozen) or room temperature (FFPE) until use

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- For Visium platform: Perform hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and imaging

- Permeabilize tissue to release RNA while maintaining spatial information

- Perform reverse transcription using spatial barcoded primers

- Synthesize second strand cDNA and amplify libraries

- Quality control using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

- Sequence libraries on Illumina platforms (typically NovaSeq 6000)

Data Processing and Analysis

- Demultiplex raw sequencing data using spaceranger (10X Genomics) or platform-specific tools

- Align sequences to reference genome and generate feature-spot matrices

- Perform quality control filtering based on unique molecular identifiers, genes per spot, and mitochondrial percentage

- Utilize Seurat or Scanpy for normalization, dimension reduction, and clustering

- Annotate cell types using reference datasets and marker genes

- Analyze spatial patterns using specialized packages (e.g., SPATA2, Giotto)

This standardized approach enables reproducible spatial transcriptomic profiling while maintaining tissue context, essential for identifying spatially restricted biomarkers and understanding tissue microenvironment in disease pathogenesis [27] [30].

Multimodal Data Integration Framework

The integration of multiple omics modalities requires specialized computational approaches to extract biologically meaningful insights. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive framework for single-cell multimodal data integration:

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- For each modality (RNA, ATAC, ADT, etc.), perform modality-specific quality control

- Filter cells based on quality metrics: for RNA (number of features, counts, mitochondrial percentage); for ATAC (nucleosome signal, TSS enrichment); for ADT (total counts, isotype controls)

- Normalize each modality using appropriate methods: SCTransform for RNA, term frequency-inverse document frequency for ATAC, centered log-ratio for ADT

- Identify highly variable features for each modality

Multimodal Integration and Joint Embedding

- Select integration method based on data structure and analysis goals:

- Vertical integration: For paired multimodal measurements from the same cells (e.g., CITE-seq)

- Diagonal integration: For overlapping but not identical features across batches

- Mosaic integration: For datasets with non-overlapping features

- Cross integration: Transferring information across modalities and batches

- Apply benchmarked methods such as Seurat WNN, Multigrate, or Matilda for vertical integration

- Generate joint embeddings that capture shared biological variation across modalities

- Visualize integrated data using UMAP or t-SNE plots

Downstream Analysis and Interpretation

- Perform clustering on the integrated embedding to identify cell states

- Annotate cell types using marker genes from all available modalities

- Identify multimodal markers that consistently define cell types across modalities

- Construct gene regulatory networks by combining RNA and ATAC data

- Infer cell-cell communication networks incorporating spatial information

This integration framework enables researchers to leverage complementary information from multiple omics layers, providing a more comprehensive understanding of cellular identity and function than any single modality alone [10].

Computational Tools and Data Integration

Foundation Models for Single-Cell Omics

The emergence of foundation models represents a transformative advancement in single-cell omics analysis, enabling the interpretation of complex biological data at unprecedented scale and resolution. These models, pretrained on massive datasets, learn universal cellular representations that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks through transfer learning.

Table 3: Foundation Models for Single-Cell Multi-Omics Analysis

| Model | Architecture | Training Data | Key Capabilities | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | Transformer | 33+ million cells | Zero-shot annotation, perturbation prediction | Multi-omic integration, gene network inference |

| Nicheformer | Transformer | 110 million cells | Spatial context prediction, microenvironment modeling | Spatial composition prediction, label transfer |

| scPlantFormer | Transformer | 1 million plant cells | Cross-species annotation, phylogenetic constraints | Plant biology, evolutionary studies |

| CellPLM | Transformer | 11 million cells | Limited spatial transcriptomics integration | Gene imputation, basic spatial tasks |

scGPT, pretrained on over 33 million cells, demonstrates exceptional performance in zero-shot cell type annotation, multi-omic integration, and perturbation response prediction [31]. Its generative pretrained transformer architecture enables capturing hierarchical biological patterns through self-supervised learning objectives, including masked gene modeling and contrastive learning. Similarly, Nicheformer represents a significant advancement by incorporating both dissociated single-cell and spatial transcriptomics data during pretraining, enabling the model to learn spatially aware cellular representations [32]. Trained on SpatialCorpus-110M—a curated collection of over 57 million dissociated and 53 million spatially resolved cells—Nicheformer excels at predicting spatial context and composition, effectively transferring rich spatial information to conventional scRNA-seq datasets [32].

These foundation models address critical limitations of traditional analytical pipelines, which struggle with the high dimensionality, technical noise, and multimodal nature of contemporary single-cell datasets. By learning robust biological representations from massive, diverse datasets, these models facilitate cross-species cell annotation, in silico perturbation modeling, gene regulatory network inference, and spatial context prediction, significantly accelerating biomarker discovery and therapeutic development [31].

Multimodal Data Integration Strategies

The integration of multiple data modalities presents both opportunities and challenges for computational biology. Effective integration strategies must harmonize heterogeneous data types—from sparse scATAC-seq matrices to high-resolution microscopy images—while preserving biological relevance and minimizing technical artifacts.

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated 40 integration methods across four prototypical data integration categories: vertical, diagonal, mosaic, and cross integration [10]. These methods were assessed on seven common tasks: dimension reduction, batch correction, clustering, classification, feature selection, imputation, and spatial registration. For vertical integration of paired multimodal measurements, methods including Seurat WNN, sciPENN, and Multigrate demonstrated strong performance in preserving biological variation across cell types while effectively integrating multiple modalities [10].

Innovative approaches such as StabMap's mosaic integration enable the alignment of datasets with non-overlapping features by leveraging shared cell neighborhoods rather than strict feature overlaps [31]. Similarly, tensor-based fusion methods harmonize transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and spatial imaging data to delineate multilayered regulatory networks across biological scales. These computational advances are complemented by the development of federated platforms such as DISCO and CZ CELLxGENE Discover, which aggregate over 100 million cells for decentralized analysis, facilitating collaborative research while addressing data privacy concerns [31].

The scPairing framework addresses the challenge of limited multiomics data availability by artificially generating realistic multiomics datasets through pairing separate unimodal datasets [29]. Inspired by contrastive language-image pre-training, scPairing embeds different modalities from the same single cells onto a common embedding space, enabling the generation of novel multiomics data that can facilitate the discovery of cross-modality relationships and validation of biological hypotheses.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Single-Cell Multi-Omics Studies

Successful implementation of single-cell multi-omics and spatial profiling experiments requires careful selection of reagents and materials to ensure data quality and reproducibility. The following toolkit outlines essential solutions for researchers in this field:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell Multi-Omics

| Category | Specific Reagents | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability & Preparation | Acutase, Trypan blue, DNasel, RBC lysis buffer | Single-cell suspension preparation, viability assessment | Minimize stress responses, maintain cell integrity |

| Surface Protein Labeling | TotalSeq antibodies (BioLegend), CITE-seq antibodies | Multiplexed protein detection alongside transcriptomics | Titration required, isotype controls essential |

| Nucleic Acid Library Prep | Smart-seq2 reagents, 10X Chromium kits, Template switching oligos | cDNA amplification, library construction | Maintain molecular fidelity, minimize biases |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Visium tissue optimization slides, permeabilization enzymes | Spatial barcoding, tissue optimization | Optimization required for different tissue types |

| Single-Cell Indexing | Cell hashing antibodies (TotalSeq), MULTI-seq barcodes | Sample multiplexing, doublet detection | Enables pooling of samples, reduces batch effects |

Commercial Platforms and Associated Reagents

- 10X Genomics Visium: Spatial gene expression slides, tissue optimization kit, library preparation kit

- 10X Genomics Xenium: Fixed tissue panels, slide preparation reagents, decoding probes

- Nanostring GeoMx DSP: Protein and RNA slides, UV-cleavable oligonucleotides, imaging reagents

- Resolve Biosciences Spatial Molecular Imaging: Gene chemistry panel, imaging buffers

The selection of appropriate reagents depends on the specific research question, sample type, and technological platform. For instance, the ClickTags method enables sample multiplexing via DNA oligonucleotides in live-cell samples through click chemistry, eliminating the requirement for methanol fixation and expanding applications to diverse single-cell specimens including murine cells and human bladder cancer samples that have undergone freeze-thaw cycles [25]. Similarly, tissue-specific optimization of permeabilization conditions is critical for spatial transcriptomics experiments to balance RNA release efficiency with preservation of spatial information.

Visualization Schematics

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

Spatial Transcriptomics Data Integration

Single-cell multi-omics and spatial profiling technologies have fundamentally transformed our approach to biomarker discovery and therapeutic development. By enabling comprehensive molecular profiling at unprecedented resolution while preserving spatial context, these advances provide powerful tools to decipher cellular heterogeneity, tissue organization, and disease mechanisms. The integration of multimodal data through sophisticated computational methods and foundation models further enhances our ability to extract biologically meaningful insights from these complex datasets.

As these technologies continue to evolve, addressing challenges related to standardization, data integration, and clinical translation will be essential for realizing their full potential in precision medicine. The development of robust experimental protocols, benchmarking of computational methods, and creation of collaborative frameworks will accelerate the translation of these technological advances into improved diagnostic capabilities and therapeutic interventions. Ultimately, single-cell multi-omics and spatial profiling represent cornerstone methodologies that will drive the next generation of biomedical research and clinical applications.

The complexity of biological systems necessitates moving beyond single-omics studies to multi-omics approaches that integrate data from different biomolecular levels such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics [33]. This integration provides a comprehensive and systematic view of biological systems, enabling researchers to obtain a holistic understanding of how living systems work and interact [33]. Multi-omics integration has become a cornerstone of modern biological research, driven by the development of advanced tools and strategies that offer unprecedented possibilities to unravel biological functions, interpret diseases, and identify robust biomarkers [34].

The primary challenge in multi-omics integration lies in effectively combining complex, heterogeneous, and high-dimensional data from different omics levels, which requires advanced computational methods and tools for analysis and interpretation [33]. The high-throughput nature of omics platforms introduces issues such as variable data quality, missing values, collinearity, and dimensionality, with these challenges further increasing when combining multiple omics datasets [34].

Classification of Data Integration Approaches

Multi-omics data integration strategies can be categorized based on their methodology and timing within the analytical workflow. The methodological approaches include conceptual, statistical, and model-based frameworks, while temporal strategies encompass early, intermediate, and late integration [35].

Table 1: Methodological Approaches for Multi-Omics Integration