Navigating Normal Ultrastructure: A Comprehensive Guide to PCD Diagnosis and Genetic Resolution

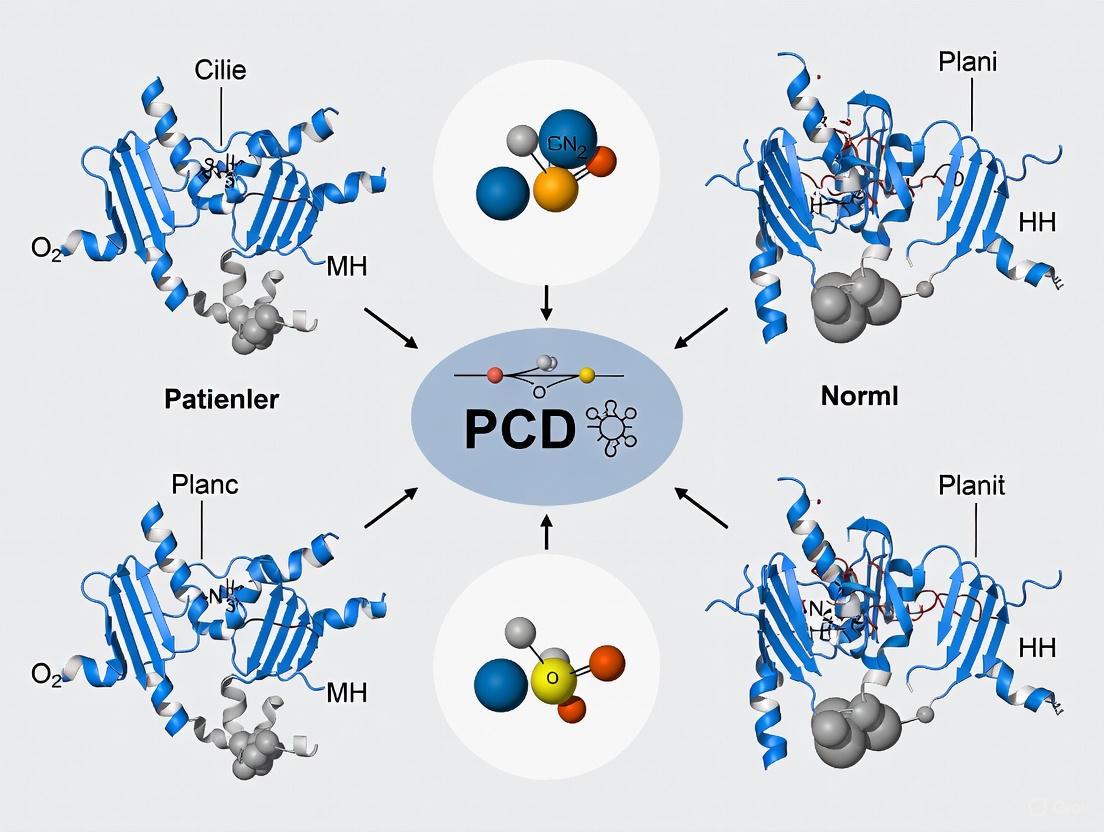

Diagnosing Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) in patients with normal ciliary ultrastructure presents a significant challenge, requiring a shift from traditional diagnostic paradigms.

Navigating Normal Ultrastructure: A Comprehensive Guide to PCD Diagnosis and Genetic Resolution

Abstract

Diagnosing Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) in patients with normal ciliary ultrastructure presents a significant challenge, requiring a shift from traditional diagnostic paradigms. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing the foundational genetics, advanced multi-modal diagnostic methodologies, strategies for optimizing diagnostic yield, and the validation of patient-reported outcomes. It synthesizes current knowledge on genes like DNAH11 that cause PCD without ultrastructural defects, explores the integration of genetic testing with high-speed video microscopy and nasal nitric oxide measurement, and discusses the implications for clinical trial design and the development of targeted therapies, including gene-based treatments.

Decoding the Genetic Basis of PCD with Normal Ultrastructure

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What percentage of genetically-confirmed PCD cases present with normal ciliary ultrastructure under TEM, and what are the primary genetic culprits?

A1: Current research indicates that up to 30% of patients with clinically and genetically confirmed PCD display normal ciliary ultrastructure when analyzed by standard Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [1] [2]. This significant subset of cases presents a major diagnostic challenge. The primary genetic associations for this phenotype include mutations in genes such as Dynein Axonemal Heavy Chain 11 (DNAH11) and HYDIN [2]. In these cases, the cilia possess all the normal structural components (e.g., dynein arms, microtubules) but are functionally impaired due to defects in the molecular mechanisms that govern ciliary beat, which are not visible with conventional ultrastructural analysis.

Q2: Our lab has identified a patient with a strong clinical phenotype of PCD, but TEM results are normal. What is the recommended diagnostic pathway?

A2: When faced with a classic PCD phenotype and normal TEM findings, the diagnostic pathway should pivot to alternative and complementary modalities. The recommended workflow is:

- Genetic Testing: Pursue a comprehensive PCD genetic panel to identify mutations in genes known to cause PCD with normal ultrastructure (e.g., DNAH11, HYDIN) [2] [3]. This is now considered a primary diagnostic method.

- Functional Ciliary Assessment: Employ High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) to evaluate ciliary beat pattern and frequency. Cilia in these cases often exhibit abnormal, dyskinetic, or stiff beating patterns despite normal appearance [4] [3].

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement: Use nNO as a screening tool. Patients with PCD, including those with normal ultrastructure, typically have very low levels of nasal nitric oxide. This serves as a strong supportive indicator [4] [5]. A combination of these approaches is essential for a definitive diagnosis when TEM is inconclusive [1] [4].

Q3: In a resource-limited setting where only TEM is available, how should we interpret "suggestive" ultrastructural defects like isolated inner dynein arm (IDA) absence or microtubular disorganization?

A3: In settings with limited access to genetic or functional tests, interpreting TEM findings requires caution. Defects such as isolated IDA absence or microtubular disorganization are categorized as Class 2 defects and are not considered confirmatory for PCD on their own [1]. These findings can be secondary to epithelial damage from infections, pollutants, or inflammation [1] [2]. The consensus guideline is to:

- Repeat the nasal brushing after a period of clinical stability and aggressive medical management of infection and inflammation.

- If the Class 2 defects persist upon repeat testing, they are considered highly suggestive of PCD, but a definitive diagnosis ideally requires confirmation with another modality [1]. In these constrained environments, a "probable" diagnosis may be used to initiate early treatment while acknowledging the diagnostic uncertainty [1].

Q4: What are the key methodological pitfalls in TEM sample processing that can mimic primary ciliary defects, and how can we avoid them?

A4: Several technical artifacts can be misinterpreted as pathological defects. Key pitfalls and solutions include:

- Poor Sample Preservation: Inadequate or delayed fixation can cause microtubular disorganization and dynein arm loss that mimics true PCD. Solution: Immediately place the nasal brushing sample in buffered glutaraldehyde and refrigerate [1].

- Inadequate Ciliary Cross-Sections: Analyzing sections from the tip or base of the cilium, where the architecture naturally differs from the standard "9+2" pattern, leads to misdiagnosis. Solution: Ensure that quantitative analysis is performed on a sufficient number (e.g., >50) of high-quality, transverse sections from the mid-portion of the cilia [2].

- Insufficient Sample Size: A sample with too few ciliated cells or cilia can prevent a statistically valid assessment. Solution: Aim for samples with an adequate number of ciliated cells and report the proportion of cilia exhibiting the defect [1].

Diagnostic Test Performance & Quantitative Data

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance and characteristics of key diagnostic tests for PCD, particularly in the context of normal ultrastructure.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Primary PCD Diagnostic Tests

| Test Method | Reported Sensitivity in PCD Diagnosis | Key Strengths | Key Limitations in Normal Ultrastructure Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | ~70% [1] | Identifies hallmark structural defects (e.g., ODA/IDA loss); considered a traditional standard. | Fails to detect ~30% of PCD cases where ultrastructure appears normal [1] [2]. |

| Genetic Testing | >90% with advanced panels [5] | Provides a definitive molecular diagnosis; identifies pathogenic mutations regardless of ultrastructure. | Not all causative genes are known; variants of uncertain significance (VUS) can complicate interpretation [3]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | >95% as a screening tool [4] | Non-invasive, rapid, and highly sensitive for screening; low in most PCD patients. | Cannot differentiate between PCD genetic subtypes; requires patient cooperation [4] [3]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVA) | High for functional defects [4] | Assesses ciliary function directly; can detect beat pattern abnormalities even with normal structure. | Requires significant expertise; not widely standardized or available [4] [3]. |

Table 2: Distribution of Ultrastructural Findings in Suspected PCD Cohorts

| TEM Finding Category | Definition | Prevalence in a Study of 67 Patients [2] | Diagnostic Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallmark Defects (Class 1) | Confirmed ODA/IDA defects in >50% of cilia | 17.9% (12/67) | Confirmatory for PCD |

| Probable Criteria (Class 2) | Defects (e.g., IDA loss) in 25-50% of cilia or central pair defects | 16.4% (11/67) | Highly suggestive, requires confirmation |

| Normal Ultrastructure | No significant defects observed | 26.9% (18/67) | Does not rule out PCD |

| Secondary Defects | Compound cilia, extra tubules (often from infection) | 41.4% - 44.3% | Not diagnostic of PCD |

Experimental Protocols for Defining PCD with Normal Ultrastructure

Integrated Diagnostic Protocol

Objective: To provide a robust methodological framework for confirming a PCD diagnosis in patients with a strong clinical phenotype but normal ciliary ultrastructure upon initial TEM screening.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology Details:

Patient Population & Clinical Phenotyping:

- Enrollment Criteria: Enroll patients with a strong clinical history indicative of PCD. Key features include: neonatal respiratory distress in term infants, daily perennial wet cough beginning in infancy, chronic sinusitis and otitis media, and any history of organ laterality defects (situs inversus or heterotaxy) [3] [5]. Tools like the PICADAR score can be used to quantify clinical likelihood [1].

Initial TEM Analysis:

- Sample Collection: A pulmonologist or ENT specialist should obtain nasal epithelial cells via brushing of the inferior surface of the nasal turbinates. The sample must be immediately placed in buffered glutaraldehyde (2.5%) and refrigerated to prevent artifactual degradation [1].

- Processing & Imaging: Process samples through standard dehydration, resin embedding, and ultra-thin sectioning (70 nm). Sections are double-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed under a TEM at 120kV [1].

- Quantitative Assessment: Analyze a minimum of 50 transverse ciliary sections. A diagnosis based on ultrastructure requires hallmark defects (e.g., absence of ODA/IDA) in >50% of the examined cilia [1] [2]. If results are normal or show only suggestive Class 2 defects, proceed to the next steps.

Genetic Testing:

- Sample & Method: Obtain a blood sample. Analysis should be performed using a next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel that encompasses all known PCD-associated genes (currently >40 genes) [6] [5].

- Interpretation: A definitive genetic diagnosis is made by identifying bi-allelic or X-linked hemizygous pathogenic mutations in a known PCD-causing gene [3]. The identification of mutations in genes like DNAH11 or HYDIN provides a clear explanation for normal ultrastructure.

Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement:

- Protocol: During a period of clinical stability, measure nNO using a chemiluminescence analyzer according to standardized guidelines. The patient should perform a breath-hold maneuver while gas is sampled from the nasal cavity.

- Interpretation: nNO levels in PCD patients, including those with normal ultrastructure, are typically very low compared to healthy controls. This serves as a powerful, non-invasive screening tool [4] [5].

High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA):

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a fresh nasal epithelial brushing and suspend it in cell culture medium.

- Imaging & Analysis: Record ciliary movement at high frame rates (≥500 frames per second). Analyze the videos for abnormal beat patterns, such as stiff, flickering, or circular motions, and reduced beat frequency, which are characteristic of functional ciliary defects despite normal structure [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Item | Specific Example / Model | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal Brush | Flexible nylon laparoscopy brush (e.g., WS-1812XA3) [1] | Minimally invasive collection of ciliated epithelial cells from the nasal turbinates. |

| Primary Fixative | 2.5% EM-grade glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer [1] | Rapidly cross-links and preserves protein structure to prevent ultrastructural artifacts in TEM samples. |

| Resin for Embedding | Agar Scientific low viscosity resin [1] | Infiltrates and embeds fixed tissue for ultra-thin sectioning for TEM. |

| TEM Stains | Aqueous 4% uranyl acetate, Reynold's lead citrate [1] | Heavy metal stains that provide contrast to cellular structures (e.g., microtubules, dynein arms) under the electron beam. |

| nNO Analyzer | Chemiluminescence nitric oxide analyzer [4] [5] | Precisely measures the concentration of nitric oxide gas in a sampled airstream for diagnostic screening. |

| High-Speed Camera | Olympus Quemesa CCD camera [1] | Captures video at very high frame rates required for detailed analysis of rapid ciliary beat patterns. |

Beyond the Microscope: Key Genes Implicated in Normo-Ultrastructural PCD (e.g., DNAH11)

FAQs: Diagnosing Normo-Ultrastructural PCD

1. A patient has a strong clinical phenotype of PCD, including low nasal nitric oxide and situs inversus, but Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) is reported as normal. What is the most likely genetic cause, and how can I confirm it?

The most common genetic cause of PCD with normal ciliary ultrastructure is biallelic mutations in the DNAH11 gene [7]. One large cohort study found that 22% (13/58) of unrelated patients with a clinical PCD phenotype and normal ultrastructure had biallelic DNAH11 mutations [7].

Confirmation requires genetic testing. Sanger sequencing of the 82 exons of DNAH11 or its inclusion in a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel for PCD-related genes can identify pathogenic variants [7]. The majority of disease-causing DNAH11 mutations are nonsense, insertion/deletion, or loss-of-function splice-site mutations [7].

2. What is the functional consequence of DNAH11 mutations on ciliary function if the ultrastructure appears normal?

Despite normal appearance under conventional TEM, DNAH11 mutations cause a functional defect in ciliary beat. Instead of being immotile, cilia typically exhibit a hyperkinetic and dyskinetic beating pattern with a reduced waveform amplitude [7]. This abnormal motion is insufficient for effective mucociliary clearance, leading to the classic PCD symptoms. This is why high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVMA) is a critical functional assay in these cases [7] [8].

3. We have identified a candidate variant in DNAH11. What in-silico and functional analyses are critical for determining its pathogenicity?

A multi-step approach is recommended to establish pathogenicity:

- In-Silico Prediction: Use programs like SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and MutationTaster to predict the impact of missense variants on protein function [9].

- Population Frequency: Filter against population databases (e.g., gnomAD, 1000 Genomes) to exclude common polymorphisms. Focus on rare variants (Minor Allele Frequency < 0.01%) [9].

- ACMG/AMP Guidelines: Classify variants according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines. A definitive genetic diagnosis typically requires two pathogenic variants in trans (either homozygous or compound heterozygous) [10].

- cDNA Analysis: If a variant affects a splice site, perform RT-PCR on RNA from patient-derived cells (e.g., nasal epithelial cells or lymphoblastoid cell lines) to confirm aberrant splicing [7].

4. Are there any advanced imaging techniques that can reveal ultrastructural defects in DNAH11-related PCD that are invisible to standard TEM?

Yes, electron tomography can detect subtle defects. While standard TEM provides 2D images, electron tomography produces 3D ultrastructural models with superior resolution. Studies show that DNAH11 mutations lead to a deficiency of >25% of the proximal outer dynein arm volume, a defect consistently visible only via this method [11]. This technique can be applied to existing araldite-embedded nasal cilia samples [11].

Troubleshooting Guide for Experimental Diagnosis

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconclusive Genetic Results | A patient with only one detected heterozygous pathogenic variant in a recessive PCD gene. | 1. Perform copy number variation (CNV) analysis to search for a second, large deletion/duplication that may be missed by NGS [10].2. Expand genetic analysis to a full whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing approach to identify variants in non-panel genes or deep intronic regions [8]. |

| Normal TEM & No Genetic Hits | Mutations in a PCD gene not included in your targeted panel; or a non-genetic mimic of PCD (e.g., secondary ciliary dyskinesia). | 1. Re-evaluate the clinical phenotype and history to exclude secondary causes [10].2. Utilize high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVMA) to document the characteristic hyperkinetic, dyskinetic beat pattern [7] [8].3. Re-classify the case as "moderate suspicion" and consider re-screening as new PCD genes are discovered [10]. |

| Difficulty Interpreting TEM | Ciliary abnormalities are present but do not meet the quantitative threshold for a "Class I" hallmark defect. | Analyze samples according to the BEAT-PCD TEM criteria [10]. Look for "Class II" alterations (e.g., central complex defects, microtubular disorganization with inner dynein arms present) which, when combined with other supportive evidence like genetic findings, can confirm the diagnosis [10]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function in PCD Research |

|---|---|

| Araldite-Embedded Ciliary Biopsies | Preserved nasal or bronchial epithelial samples for ultrastructural analysis via TEM and advanced 3D electron tomography [11]. |

| TruSeq Custom Amplicon Panel (Illumina) | A targeted NGS panel for sequencing the exonic regions of a defined set of PCD-related genes, including DNAH11, HYDIN, and CCDC65 [10]. |

| Anti-DNAH11 Antibody | For immunofluorescence staining to confirm the localization and absence of the DNAH11 protein in the proximal ciliary region (though its use in clinical diagnostics is not yet standard) [11]. |

| FlexiGene DNA Kit (Qiagen) | For reliable extraction of high-quality DNA from patient blood or buccal swabs for subsequent genetic analysis [10]. |

| Lymphoblastoid or iPSC Cell Lines | Creating stable cell lines from patient peripheral blood allows for a renewable source of DNA and RNA for genetic and transcriptomic studies, and iPSCs enable future functional correction experiments [12]. |

Experimental Workflow & Diagnostic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the multi-modal diagnostic and research pathway for a suspected case of normo-ultrastructural PCD.

Quantitative Data on DNAH11 in PCD

Table 1: Frequency of DNAH11 Mutations in a Selected PCD Cohort [7]

| Patient Cohort | Number of Unrelated Patients | Patients with Biallelic DNAH11 Mutations | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCD with normal ultrastructure | 58 | 13 | 22% |

| PCD with outer dynein arm defects | 76 | 0 | 0% |

| PCD with radial spoke/central pair defects | 6 | 0 | 0% |

| Isolated situs abnormalities (no PCD) | 13 | 0 | 0% |

Table 2: Spectrum and Predicted Impact of DNAH11 Mutations [7] [9]

| Mutation Type | Proportion of Mutant Alleles (in one study) | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Nonsense / Frameshift / Splice-site | 24/35 (69%) | Loss-of-function, premature termination |

| Missense | 11/35 (31%) | Amino acid substitution; requires pathogenicity prediction |

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous, typically autosomal recessive disorder caused by impaired motile ciliary function [13]. Establishing a definitive PCD diagnosis is contingent upon a multi-faceted approach that integrates clinical symptoms with specialized testing [14]. A significant diagnostic challenge arises in patients with strong clinical evidence of PCD but normal ciliary ultrastructure on transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In these cases, the ciliary axoneme appears structurally intact despite clear functional deficiencies, a scenario now explained by mutations in specific PCD-related genes that do not disrupt the core 9+2 microtubule architecture [15]. This technical support guide provides methodologies for correlating genotypes with clinical presentations in these complex cases, focusing on the integration of advanced genetic and functional assays to resolve diagnostic uncertainties.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: A patient has a classic PCD clinical phenotype, including neonatal respiratory distress and laterality defects, but TEM shows normal ultrastructure. What is the most efficient diagnostic path?

A1: Proceed directly to genetic testing using a comprehensive PCD gene panel. Several genetic defects, particularly those in DNAH11, HYDIN, CCDC164, and CCDC65, are known to cause PCD with normal TEM findings [15] [16]. In one study, genetic testing confirmed PCD in 50.7% of clinically suspected cases, whereas TEM alone would have identified defects in only 40.5% of those confirmed cases, highlighting the limited sensitivity of TEM for all PCD genotypes [15].

Q2: Genetic testing identified a single heterozygous pathogenic variant in a recessive PCD gene. What are the next steps to confirm or rule out PCD?

A2: This is a common diagnostic dilemma. Current research indicates that noncoding DNA variants may account for a significant number of these incomplete genetic diagnoses.

- Recommended Action: If available, pursue end-to-end gene sequencing of the relevant PCD gene, focusing on intronic regions, to identify potential splice-altering variants [16]. One study found that this approach successfully identified a second pathogenic (intronic) variant in 38% of patients with a single previously identified heterozygous mutation, thereby confirming the diagnosis [16].

- Alternative Approach: Perform cDNA analysis from nasal epithelial cells to validate the impact of the variant on splicing and gene expression [16].

Q3: How reliable is nasal nitric oxide (nNO) as a screening tool for PCD genotypes with normal ultrastructure?

A3: nNO measurement remains a valuable screening tool, as levels are typically very low in most PCD patients [17] [13] [18]. However, be aware that some genetic variants may show discrepancies with nNO measurements [18]. It should not be used as a standalone test but as part of a multi-modal diagnostic strategy to target patients for advanced genetic testing [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Diagnostic Scenarios

| Challenge | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconclusive Genetic Test (Single heterozygous variant) | Variant in non-coding region (intron); Poorly characterized VUS [16] | Perform end-to-end gene sequencing; conduct cDNA analysis to confirm splicing defects; share variant data via ClinGen/CiliaVar databases [16]. |

| Strong Clinical Phenotype, Normal TEM, Negative Genetics | Mutations in novel PCD genes not on standard panels; non-ciliopathy genetic disorder mimicking PCD (e.g., WFDC2 deficiency) [16] | Utilize whole-exome/genome sequencing; consider functional ciliary studies like high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA) [15] [16]. |

| Poor Quality Nasal Biopsy for TEM/IF | Acute infection, improper sample handling/processing [1] | Repeat biopsy 4-8 weeks after resolution of acute illness; ensure immediate fixation in buffered glutaraldehyde; use standardized processing protocols [1]. |

| Discrepancy between nNO and Clinical Picture | Specific genotype affecting NO synthesis; technical issues with measurement [18] | Use nNO as a screening tool only; rely on genetic testing and other functional assays (e.g., HSVA) for diagnostic confirmation [15] [18]. |

Quantitative Data: Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in PCD

Understanding the distribution of genetic defects and their associated clinical outcomes is crucial for prognosis and management. The tables below synthesize key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Distribution of Ultrastructural and Genetic Defects in Confirmed PCD Cases

| Defect Category | Subtype | Percentage of Cases | Common Associated Gene(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrastructural Defects (via TEM) [15] | Outer Dynein Arm (ODA) | 32% | DNAH5, DNAI1 [17] [13] |

| Central Apparatus | 19% | RSPH4A, RSPH9 [15] | |

| Radial Spokes | 16% | RSPH1 [15] | |

| Ciliogenesis Defects | 14% | CCDC40, CCDC39 [15] | |

| Nexin-Dynein Regulatory Complex | 11% | CCDC65, GAS8 [15] | |

| Normal Ultrastructure [15] | (Normal on TEM) | ~30% | DNAH11, HYDIN, CCDC164 [15] [16] |

Table 2: Clinical Presentation Frequencies in Genetically Confirmed PCD Cohorts

| Clinical Feature | Frequency in PCD Patients | Notes / Genotype Correlations |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Wet Cough [15] [19] | 100% | Universal finding, typically beginning in first year of life [15]. |

| Neonatal Respiratory Distress [13] | "Most patients" [13] | A history in term infants is a major clinical criterion [15]. |

| Bronchiectasis [15] [19] | 70.3% | Demonstrated on CT scan; prevalence increases with age [15]. |

| Situs Inversus Totalis [15] | ~50% | Hallmark of Kartagener's syndrome [13]. |

| Situs Abnormalities (total) [15] | 24.3% | Includes situs inversus and heterotaxy [15]. |

| Chronic Rhinitis/Nasal Congestion [15] | 97.3% | Daily and year-round from early life [15]. |

| Chronic Otitis Media [15] | 75.7% | Leads to hearing impairment in some cases [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Advanced PCD Diagnostics

Protocol 1: Transmission Electron Microscopy for Ciliary Ultrastructure

Principle: This protocol details the standardized processing and analysis of nasal brush biopsies to visualize the ciliary axonemal structure via TEM, which is critical for identifying hallmark defects [1].

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: Obtain nasal brushings from the inner turbinates using a flexible nylon laparoscopy brush. Immediately place the sample in fresh, cold buffered glutaraldehyde (2.5%) [1].

- Sample Cleaning: Under a dissecting microscope, gently clean the brush of adherent mucus and debris while immersed in fixative [1].

- Processing:

- Rinse in buffer (3 x 30 min).

- Post-fix in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide for 1 hour.

- Rinse again in buffer and then pure water.

- Dehydrate in a graded ethanol series (10% to 100%).

- Infiltrate with low-viscosity resin (e.g., Agar Scientific) using resin:ethanol mixtures, culminating in pure resin overnight.

- Embed in capsules and polymerize at 70°C [1].

- Sectioning and Staining: Section the polymerized blocks at 70 nm thickness. Double-stain grids with aqueous uranyl acetate (4%, 15 min) and Reynold's lead citrate (10 min) [1].

- Imaging and Analysis: View grids at 120 kV. Capture micrographs of ciliary cross-sections. Analyze a minimum of 50 cilia from different cells, following international consensus guidelines [1]. Defects in >50% of cilia are considered diagnostic for PCD for specific ultrastructural abnormalities (Class 1 defects) [1].

Protocol 2: Next-Generation Sequencing and Variant Interpretation

Principle: To identify pathogenic sequence variants in known PCD-associated genes from patient-derived DNA.

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes or other suitable tissues using standard protocols [15] [19].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare sequencing libraries from the DNA. Use a targeted multigene panel for PCD or whole-exome sequencing. Perform sequencing on an NGS platform [15].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map sequence reads to a reference genome. Call and annotate variants (SNPs, indels). Filter against population frequency databases (e.g., gnomAD) to remove common polymorphisms [15] [19].

- Variant Assessment: Interpret the pathogenicity of remaining variants according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG/AMP) guidelines. Use in silico prediction tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen2, MutationTaster) and databases (e.g., ClinVar) [15] [19]. For cases with a single identified variant, consider end-to-end sequencing to find noncoding (e.g., intronic) variants [16].

- Segregation Analysis: Confirm compound heterozygosity or homozygosity by Sanger sequencing of the variant(s) in available family members [15].

Protocol 3: Immunofluorescence Analysis of Ciliary Proteins

Principle: To confirm the pathogenicity of genetic variants by visualizing the presence, absence, or mislocalization of specific ciliary proteins.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain nasal brushings and place the cells in appropriate culture medium or process immediately [15].

- Slide Preparation and Fixation: Spread cells onto glass slides and allow to adhere. Fix cells, typically with methanol or paraformaldehyde, depending on antibody requirements [15].

- Antibody Staining:

- Permeabilize and block cells to reduce non-specific binding.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., mouse anti-DNAH5, rabbit anti-GAS8) diluted in blocking buffer.

- Wash thoroughly.

- Incubate with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (e.g., anti-mouse IgG-Alexa Fluor 488, anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 594) [15].

- Microscopy and Analysis: Mount slides with an anti-fade medium containing DAPI to stain nuclei. Image using a fluorescence or confocal microscope. Compare the staining pattern and intensity in patient cells to healthy controls to identify protein deficiencies [15].

Diagnostic Pathways & Genetic Analysis

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow for diagnosing PCD, particularly in complex cases with normal ultrastructure, and the process for resolving variants of uncertain significance.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic workflow for PCD, integrating multiple testing modalities to resolve cases with normal ultrastructure or inconclusive genetics. nNO: nasal nitric oxide; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; NGS: next-generation sequencing; VUS: variant of uncertain significance.

Diagram 2: A stepwise pipeline for resolving the clinical significance of a genetic variant of uncertain significance (VUS).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for PCD Diagnostic and Research Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Nylon Brushes | Collection of ciliated nasal epithelial cells for TEM, IF, or cell culture. | WS-1812XA3 laparoscopy brush; cervix brush with trimmed fibres [1]. |

| Buffered Glutaraldehyde | Primary fixative for TEM; preserves ultrastructural details of cilia. | 2.5% EM grade glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, osmotically adjusted [1]. |

| Low-Viscosity Resin | Embedding medium for TEM samples; allows for precise thin-sectioning. | Agar Scientific low viscosity resin [1]. |

| Primary Antibodies for IF | Visualize specific ciliary proteins to confirm genetic findings (e.g., absence of protein). | Mouse anti-DNAH5; Rabbit anti-GAS8; used at 1:500 dilution [15]. |

| PCD Multigene NGS Panel | Targeted sequencing of all known PCD-related genes for efficient molecular diagnosis. | Panels should include >50 genes, e.g., DNAH5, DNAH11, RSPH4A, CCDC genes [15] [19] [16]. |

| Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing | Hypothesis-free genetic testing to identify novel variants or genes, especially in unsolved cases. | Used when targeted NGS panels are negative [16]. |

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder affecting motile cilia, with significant implications for patient morbidity and mortality. Understanding the epidemiology and disease trajectory is crucial for researchers and clinicians developing targeted therapies. The estimated prevalence of PCD ranges from 1:7,500 to 1:20,000 live births, though the true prevalence is likely higher due to diagnostic challenges and underrecognition [20]. Prognosis varies considerably based on genotypic and phenotypic factors, with certain genetic subtypes experiencing more severe disease progression and poorer outcomes [21]. This technical guide provides researchers with essential troubleshooting and methodological frameworks for investigating PCD prevalence and prognostic determinants, with particular emphasis on diagnostically challenging cases with normal ultrastructure.

Prevalence and Diagnostic Statistics

Table 1: Epidemiological and Diagnostic Characteristics of PCD

| Parameter | Statistical Range | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 1:7,500 - 1:20,000 live births | True prevalence likely higher due to underdiagnosis [20] |

| Genetic Heterogeneity | >50 associated genes | Number continues to grow with ongoing research [20] [22] |

| Cases with Normal Ultrastructure | ~30% | Normal TEM findings despite clinical PCD (e.g., DNAH11 mutations) [11] [23] |

| Diagnostic Sensitivity of TEM Alone | ≤70% | Limited by normal ultrastructure cases; requires complementary tests [23] |

| Neonatal Respiratory Distress | >80% of neonates | Requiring respiratory support within first day of life [20] |

| Laterality Defects | ~50% of patients | Situs inversus or heterotaxy [20] |

Prognostic Indicators and Clinical Outcomes

Table 2: Prognostic Factors and Disease Outcomes in PCD

| Factor | Impact on Prognosis | Evidence & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Variable severity | CCDC39/CCDC40 mutations associated with poorer outcomes and rapid lung function decline [21] |

| Lung Function (FEV1) | Progressive decline | Similar decline course to cystic fibrosis; stabilizes in middle age possibly due to survivor bias [21] |

| Early Diagnosis | Morbidity reduction | Some benefit from diagnosis <1 year; no significant difference in annual lung function decline post-diagnosis [21] |

| PCD vs. CF Outcomes | Worse in PCD pre-modulators | Children with PCD had worse health outcomes than those with CF before CFTR modulator therapies [21] |

| Bronchiectasis | Common complication | Children with MTD/IDA defects (CCDC39, CCDC40) have greater tendency to bronchiectasis [20] |

Troubleshooting Guide: PCD Research Challenges & Solutions

Diagnostic Challenges in Normal Ultrastructure PCD

Problem: How to confirm PCD diagnosis in patients with normal ciliary ultrastructure on transmission electron microscopy (TEM)?

- Background: Approximately 30% of PCD cases, particularly those with DNAH11 mutations, display normal ciliary ultrastructure with standard TEM, creating diagnostic challenges [11] [23].

- Solution Protocol: Implement electron tomography for enhanced ultrastructural analysis.

- Sample Preparation: Collect nasal cilia biopsies and embed in araldite resin per standard TEM protocols [11].

- Data Collection: Acquire dual-axis tomograms from embedded cilia samples.

- Image Processing: Reconstruct 3D ultrastructural models using IMOD and Chimera software [11].

- Quantitative Analysis: Measure proximal outer dynein arm volume; deficiency of >25% is indicative of DNAH11-related PCD [11].

- Validation: This method successfully identified proximal outer dynein arm deficiencies in all studied patients with DNAH11 mutations (n=7) despite normal standard TEM [11].

Problem: How to identify appropriate candidates for PCD testing amid nonspecific respiratory symptoms?

- Solution Protocol: Apply the PICADAR (PCD Rule) clinical prediction tool.

- Inclusion Criteria: Patients with persistent wet cough [24].

- Parameter Scoring: Assign points for seven clinical features:

- Full-term gestation

- Neonatal chest symptoms

- Neonatal intensive care admission

- Chronic rhinitis

- Ear symptoms

- Situs inversus

- Congenital cardiac defect [24]

- Interpretation: Score ≥5 points indicates high probability of PCD (sensitivity 0.90, specificity 0.75) [24].

Technical and Methodological Challenges

Problem: How to diagnose PCD in resource-limited settings with restricted access to advanced testing?

- Background: Many settings lack access to genetic testing, nNO measurement, or high-speed video microscopy [23].

- Solution Protocol: Optimize TEM as a primary diagnostic tool with standardized reporting.

- Sample Collection: Obtain nasal brushings from inner turbinates using flexible nylon laparoscopy brushes [23].

- Processing: Immediate fixation in buffered glutaraldehyde, followed by standard TEM processing [23].

- Analysis: Evaluate transverse sections of ≥50 cilia for hallmark ultrastructural defects [23].

- Classification:

- Limitations: TEM alone cannot detect 30% of PCD cases with normal ultrastructure [23].

Problem: How to correlate genotype with disease prognosis for drug development targeting?

- Solution Protocol: Establish genotype-phenotype correlations through natural history studies.

- Patient Stratification: Group patients by confirmed genetic mutations [20] [21].

- Longitudinal Monitoring: Track lung function decline (FEV1), bronchiectasis progression via CT imaging, and microbiology patterns [20] [21].

- Outcome Analysis: Compare disease severity trajectories across genotypic groups.

- Key Findings: CCDC39 and CCDC40 mutations are associated with more severe lung disease and earlier bronchiectasis development compared to ODA defects (e.g., DNAH5, DNAI1) [20] [21].

Research Workflow: Diagnostic Pathway for Normal Ultrastructure PCD

The following diagram illustrates the integrated diagnostic and research pathway for investigating PCD cases with normal ultrastructure:

Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Investigations

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for PCD Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Application | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal Brush Biopsy Kits | Ciliary sample acquisition | Obtain ciliated epithelial cells for TEM, genetic analysis, and culture [23] |

| Glutaraldehyde Fixative (2.5%) | TEM sample preservation | Maintain ciliary ultrastructure for electron microscopy studies [23] |

| PCD Genetic Panels | Mutation detection | Identify pathogenic variants across >50 known PCD-associated genes [20] [3] |

| IMOD & Chimera Software | 3D electron tomography | Reconstruct and analyze ciliary ultrastructure from tomographic data [11] |

| Antibodies for Ciliary Proteins | Immunofluorescence staining | Visualize specific protein localization and defects (e.g., DNAH11) [20] [3] |

| PICADAR Scoring Tool | Patient screening | Identify high-probability PCD cases for research enrollment [24] |

FAQs on PCD Prevalence and Prognosis Research

Q1: Why is PCD considered underdiagnosed, and how does this affect prevalence studies? A: PCD is underdiagnosed due to several factors: nonspecific clinical presentation overlapping with more common respiratory conditions, limited access to specialized diagnostic centers, and the absence of a single standalone diagnostic test with 100% sensitivity. Current prevalence estimates of 1:7,500-1:20,000 likely represent underestimates, and true prevalence may be higher. Research accounting for diagnostic limitations suggests genomic screening of bronchiectasis populations reveals significant underdiagnosis [20] [22].

Q2: What are the key prognostic differences between major genetic subtypes of PCD? A: Genotype significantly influences disease progression:

- CCDC39/CCDC40 mutations: Associated with more severe lung disease, earlier bronchiectasis development, and poorer lung function outcomes [20] [21].

- DNAH5/DNAI1 mutations (ODA defects): Typically follow a milder disease course with slower progression [20].

- DNAH11 mutations: Often show preserved lung function despite typical PCD symptoms, with normal ultrastructure on standard TEM [20]. Natural history studies for different genetic subtypes remain a research priority [21].

Q3: What methodological approaches are essential for investigating PCD with normal ultrastructure? A: Research on normal ultrastructure PCD requires:

- Advanced imaging: Electron tomography to detect subtle defects missed by standard TEM [11].

- Genetic sequencing: Comprehensive panels or whole exome sequencing to identify mutations in genes like DNAH11 [11].

- Functional assays: High-speed video microscopy analysis to characterize ciliary beat patterns [20].

- Protein localization: Immunofluorescence staining to visualize protein distribution abnormalities [3].

Q4: How do outcomes for PCD compare to cystic fibrosis, and why does this matter for drug development? A: Evidence shows children with PCD had worse health outcomes than those with CF before the advent of CFTR modulators. With the development of highly effective CF modulators like Trikafta, this outcome gap is widening significantly. This disparity highlights the urgent need for targeted PCD therapies and justifies increased research investment in disease-modifying treatments for PCD [21].

Q5: What are the limitations of current PCD diagnostic tests in research settings? A: Major limitations include:

- TEM: Cannot detect approximately 30% of PCD cases with normal ultrastructure [23].

- Genetic testing: May not identify definitive causal variants in all patients, as not all PCD genes are known [11].

- nNO measurement: Requires patient cooperation and specialized equipment, with limited availability [20].

- HSVA: Needs specialized expertise for interpretation and may be normal in some PCD cases [20]. The diagnostic golden standard requires a combination of these modalities [20] [22].

Advanced Diagnostic Toolkit: A Multi-Modal Approach for Complex Cases

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the diagnostic yield of extended genetic panels compared to Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) for PCD?

Genetic testing strategies vary in their diagnostic sensitivity. The table below summarizes the reported diagnostic yields from key studies.

Table 1: Diagnostic Yield of Genetic Testing Strategies for PCD

| Testing Method | Reported Diagnostic Yield | Key Study Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Extended Gene Panel (26 genes) | 80% sensitivity in definite PCD cases [25] | 20% false-negative rate in a multicenter study of 534 children with high clinical suspicion [25]. |

| Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | 76% overall molecular genetic yield [26] | WES followed by targeted CNV analysis identified diagnoses in 34 of 45 families (76%) [26]. |

| Combined WES & CNV Analysis | 55% increased diagnosis in unsolved cases [26] | Applied to 20 previously unsolved families, this approach identified clinically significant findings in 11 (55%) [26]. |

Q2: Which PCD genes are associated with normal ciliary ultrastructure, and why is their identification important?

A significant number of PCD-causing genes do not produce the hallmark ultrastructural defects visible under transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Identifying these genotypes is critical to avoid misdiagnosis.

Table 2: PCD Genes Associated with Normal Ciliary Ultrastructure [26] [20]

| Gene | Primary Ciliary Defect |

|---|---|

| DNAH11 | Outer dynein arm (ODA) defects that do not alter ultrastructure but impair motility [26] [20]. |

| HYDIN | Absence of central pair projection proteins; TEM appears normal due to technical limitations in visualizing the defect [26] [20]. |

| CCDC164/DRC1 | Defects in the nexin-dynein regulatory complex (N-DRC) [26]. |

| CCDC65/DRC2 | Defects in the nexin-dynein regulatory complex (N-DRC) [26]. |

Q3: What are the common pitfalls in interpreting genetic test results for PCD?

Researchers should be vigilant about several common issues:

- Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS): Sequence changes whose clinical impact is unknown. A VUS is not a diagnostic result and should not be used to confirm or rule out PCD [27].

- False Negatives: These can occur due to variants in non-coding regions, copy number variations (CNVs) not detected by sequencing, or novel genes not yet associated with PCD [25] [26].

- Complex Genetic Results: Misinterpretation of benign variants as pathogenic can lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate management, as seen in other genetic disorders [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconclusive Genetic Results in a Patient with Strong Clinical Phenotype and Low nNO

Scenario: A patient has classic PCD symptoms and repeatedly low nasal nitric oxide (nNO), but initial genetic testing (panel or WES) does not identify biallelic pathogenic mutations.

Solution: Implement a systematic re-analysis protocol.

- Interim Diagnosis: Classify the case as "probable PCD" based on clinical phenotype and low nNO [25].

- Data Re-analysis: Re-analyze the raw sequencing data (e.g., VCF files) from the initial test. Focus on:

- Novel Genes: The list of known PCD-associated genes has grown to over 50 [20]. Regular re-analysis can uncover mutations in genes discovered after the initial test was run.

- Copy Number Variations (CNVs): Perform targeted CNV analysis on suspected genes. CNVs account for a significant number of cases and are not always detected by standard sequencing [26].

- Research Pathways: If clinically available testing remains inconclusive, consider enrolling the patient in a research study focused on gene discovery.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this troubleshooting process:

Problem: Differentiating PCD from Other Hereditary Bronchiectasis Causes

Scenario: A patient presents with diffuse bronchiectasis and chronic respiratory symptoms. Genetic testing is needed to distinguish between PCD, Cystic Fibrosis (CF), and other genetic causes.

Solution: Deploy a multi-test diagnostic algorithm that integrates WES with functional assays.

- Initial Simultaneous Testing:

- Integrated Interpretation: Correlate the genetic findings with functional test results.

- A low nNO with biallelic mutations in a PCD gene confirms PCD.

- An elevated sweat chloride level with biallelic CFTR mutations confirms CF.

- WES may identify mutations in genes such as those causing Immunodeficiency-21 [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Whole-Exome Sequencing and Analysis for PCD

This protocol outlines the key steps for using WES in a PCD research or diagnostic pipeline.

1. Sample Preparation & Sequencing

- DNA Source: Extract genomic DNA from peripheral blood leukocytes [26] [28].

- Exome Capture: Use a clinical-grade exome capture kit (e.g., Agilent SureSelectXT) to enrich for protein-coding regions [26].

- Sequencing Platform: Sequence the library on an Illumina platform (e.g., HiSeq 2500) to achieve a mean depth of coverage >100x, with >95% of target bases covered [26].

2. Bioinformatic Analysis

- Alignment: Align sequence reads to the reference human genome (hg19) using a tool like Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [26].

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) using a pipeline like GATK [26].

- Variant Filtering & Prioritization:

- Filter for variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) <0.01 in population databases (e.g., gnomAD, 1000 Genomes).

- Prioritize loss-of-function variants (nonsense, frameshift, splice-site) and missense variants predicted to be damaging by in silico tools (e.g., SIFT, PolyPhen-2).

- Focus on genes known to be associated with PCD and other motile ciliopathies [26] [28].

3. Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis

- Perform targeted CNV analysis on the WES data or using complementary methods like array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) to detect exon-level deletions or duplications [26].

4. Validation & Reporting

- Confirm pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants by an independent method (e.g., Sanger sequencing).

- Report findings according to ACMG guidelines, stating clearly if biallelic mutations in a PCD gene were identified [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for PCD Genetic Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Agilent SureSelectXT Human All Exon V4+ Capture Kit | A commercial kit used to enrich for the exonic regions of the genome prior to sequencing [26]. |

| Illumina HiSeq 2500/4000 Systems | Next-generation sequencing platforms used for high-throughput WES [26]. |

| Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) | Open-source software for aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome [26]. |

| Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) | A structured software package for variant discovery in high-throughput sequencing data [26]. |

| Franklin by Genoox | A commercial genomic analysis platform used for the interpretation and clinical reporting of genetic variants [28]. |

| TaqMan Copy Number Assays | Used for targeted validation of specific CNVs (e.g., exon 7 deletions in DYX1C1) identified in WES data [26]. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common challenges encountered during HSVA experiments for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) research.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common HSVA Experimental Issues

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Abnormal ciliary beat pattern/frequency in samples | Secondary damage (infection, smoking, drugs) [29] | Repeat brush biopsy at a different time; confirm identical aberration across at least two tests [29] |

| Low specificity; inconsistent results | Investigator inexperience; low sample throughput [30] | Limit HSVA to expert centres with high sample volume; utilize post-cell culture analysis [30] |

| Poor sample viability or yield | Sample processing delays; suboptimal brush biopsy [29] | Use nasal brush biopsy; suspend cells in medium; perform analysis immediately after sampling [29] |

| Difficulty identifying circular ciliary movements | Limited analysis perspective [29] | Analyze cilia from both side and top views during video evaluation [29] |

| Inability to exclude PCD despite normal HSVM | PCD variants with near-normal ciliary beating [29] [20] | Use HSVA as an adjunct test only; confirm diagnosis with TEM, genetic testing, or nNO [30] [31] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary diagnostic value of HSVA in PCD research, especially for patients with normal ultrastructure?

HSVA is a cornerstone for detecting functional PCD variants with normal ultrastructure, which methods like transmission electron microscopy (TEM) might miss [29]. Whereas TEM detects only 60-70% of PCD cases, HSVA can identify abnormalities in ciliary beating even when the ciliary structure appears normal under TEM, such as in cases caused by mutations in the DNAH11 gene [29] [20]. This makes it a crucial functional assay to complement structural and genetic analyses.

Why is my HSVA yielding inconsistent or non-specific results, and how can I improve accuracy?

Inconsistencies often arise from secondary ciliary damage or investigator inexperience [29] [30]. Cilia are highly sensitive to damage from infections, smoking, or other insults, which can alter the beat pattern and impair specificity [29]. To improve accuracy:

- Perform post-cell culture analysis whenever possible, as it has higher specificity compared to pre-culture testing [30].

- Ensure the analysis is conducted at a specialist centre with a high throughput of samples to maintain expertise [30].

- Repeat the test at least twice at different times to confirm persistent abnormalities [29].

What are the critical technical specifications for a valid HSVA?

A valid HSVA requires adherence to specific technical standards:

- Recording Speed: Use a high-speed video camera recording at >100 frames per second [29].

- Analysis Mode: Evaluation must be performed in real time and slow motion to qualitatively and quantitatively characterize the beat pattern, including frequency, amplitude, and waveform [29].

- Sample Type: Nasal brush biopsies are recommended for the best yield [29].

- Analysis Perspective: It is critical to observe cilia from both the side and top views to correctly identify circular movements [29].

My patient has a strong clinical phenotype, but HSVA shows normal ciliary beating. Does this rule out PCD?

No, a normal HSVM result does not exclude PCD [30]. Several PCD variants are known to have increased ciliary beat frequency or an almost normal beat pattern [29]. Therefore, HSVA should not be used as a stand-alone diagnostic test. The diagnosis must be confirmed through a combination of other methods, such as genetic testing, TEM, immunofluorescence (IF), or demonstrating reduced nasal nitric oxide (nNO) [29] [30] [31].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core HSVA Protocol for Ciliary Beat Analysis

Below is a standardized workflow for measuring ciliary beat frequency (CBF) and mucociliary transport (MCT) in human airway epithelial cells, integrating key steps from current methodologies [29] [32] [33].

Protocol Details:

- Sample Collection: Obtain respiratory ciliated cells via brush biopsy from the inferior nasal turbinate. Nasal samples provide the best yield and can be easily obtained [29] [34].

- Sample Preparation: Suspend the brushed cells in culture medium and place them on a slide. The analysis should be performed as soon as possible after sampling to preserve ciliary function [29].

- High-Speed Video Recording: Record ciliary motion using a high-speed video camera connected to a microscope, capturing sequences at a frame rate of >100 frames per second [29].

- Post-Acquisition Analysis: Analyze the recorded videos in real time and slow motion. Characterize the ciliary beat pattern both quantitatively (frequency) and qualitatively (amplitude, waveform). It is crucial to observe cilia from both side and top views to identify abnormal, circular movements [29]. Utilize image processing and particle imaging velocimetry for precise quantification of CBF and MCT [32] [33].

- Data Interpretation: Compare the observed beat pattern and frequency against known pathological patterns. A diagnosis of PCD should be supported by other tests (genetics, TEM, nNO) or by demonstrating identical aberrations in repeated HSVA tests [29] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for HSVA Experiments

| Item | Function/Application in HSVA |

|---|---|

| Brush Biopsy Kit | Minimally invasive collection of ciliated epithelial cells from the nasal turbinate [29]. |

| Cell Culture Medium | Suspension medium for sampled cells to maintain viability prior to and during analysis [29]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscope | Core system for capturing ciliary motion at frame rates >100 fps for detailed beat pattern analysis [29]. |

| Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Optics | Enhances contrast in unstained, transparent ciliated samples for clearer visualization [34]. |

| Image Processing & PIV Software | For post-acquisition analysis, enabling precise quantification of ciliary beat frequency (CBF) and mucociliary transport (MCT) velocity [32] [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary diagnostic role of nNO measurement in PCD? nNO measurement serves as a highly sensitive and specific screening tool for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD). In cooperative patients (generally over 5 years old) with a high clinical suspicion for PCD, meta-analyses have shown that nNO testing using velum closure maneuvers has a summary sensitivity of 97.6% and specificity of 96.0% compared to the reference standards of electron microscopy (EM) and/or genetic testing. This makes it a powerful initial test in the diagnostic pathway [35].

Q2: Which respiratory manoeuvres are used for nNO sampling, and how do I choose? There are three main respiratory manoeuvres, selected based on patient age and cooperation level [36]:

- Exhalation Against Resistance (ER-nNO): The gold-standard method. It provides feedback on sustained exhalation and velum closure. Suitable for cooperative patients, generally over 5-6 years old.

- Breath-Hold (BH-nNO): An alternative method for patients who can voluntarily close their velum. It shows similar repeatability to the ER method if velum closure is achieved.

- Tidal Breathing (TB-nNO): A non-velum closure method used when patients cannot perform the other manoeuvres, such as in infants, young children (under 5-6 years), or adults with poor lung function. Note that results from this method are typically lower due to dilution from lower airway air [36].

Q3: What factors can lead to falsely low or high nNO measurements? Several patient and environmental factors can influence nNO levels and must be considered before testing [36]:

| Factor Type | Specific Factor | Impact on nNO Level |

|---|---|---|

| Patient Factors | Acute viral infection or upper/lower airway exacerbation | Falsely Low |

| Recent nasal or sinus surgery | Falsely Low | |

| Nose bleeds or recent nasal biopsy/brushing | Falsely Low | |

| Nasal obstruction (e.g., polyps, severe congestion) | Falsely Low | |

| Environmental Factors | High ambient NO levels | Falsely High |

| Technical Factors | Sampling line obstruction | Falsely Low |

| Poor seal with the nasal olive | Variable |

Q4: My patient has a strong clinical phenotype for PCD but a normal nNO level. What should I do? A normal nNO level does not completely rule out PCD. Some genetic variants, particularly those affecting ciliary central apparatus components, can present with a PCD phenotype but have nNO levels within the normal or borderline range [37] [18]. In such cases, and in all cases where clinical suspicion remains high, you should proceed with confirmatory diagnostic tests. The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend a multi-step diagnostic process, which includes high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing [20].

Q5: What are the key differences between chemiluminescence and electrochemical nNO analyzers? The choice of analyzer is fundamental. The table below summarizes the pros and cons of each technology [36]:

| Feature | Chemiluminescence Analyzers | Electrochemical Analyzers |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | High accuracy and reliability [36] | Good performance [36] |

| Data Output | Real-time display of NO curve; allows for manual plateau selection and validation [36] | Results are displayed after a fixed sampling time; some models may display a non-real-time curve [36] |

| Validation | Rigorously tested with published, validated cut-off values [36] | Less published validation data available [36] |

| Ease of Use | Requires rigorous operator training and expertise [36] | Simple to use; consistent training provided [36] |

| Portability & Cost | Less portable; more expensive to purchase and maintain [36] | Smaller, portable, and more cost-effective [36] |

| Maintenance | Requires regular calibration [36] | Requires no calibration or preventative maintenance [36] |

Troubleshooting Common nNO Measurement Issues

Problem 1: Inability to Achieve a Stable Plateau during Exhalation Against Resistance

- Potential Causes: The patient may not be exhaling steadily, the resistance may be incorrect, or there could be a velum closure issue.

- Solutions:

- Ensure the patient is exhaling against the resistor (e.g., a party blower) at a pressure of 5-10 cm H₂O.

- Provide the patient with thorough coaching and a demonstration.

- Verify that the equipment (mouth resistor, sampling tube) is not blocked.

- If a stable plateau still cannot be achieved, consider switching to the breath-hold manoeuvre if the patient is able [36].

Problem 2: Consistently Low nNO Readings in a Patient Without a Typical PCD Phenotype

- Potential Causes: Refer to the table in FAQ #3. Common causes include recent respiratory infection, undetected nasal bleeding, or cystic fibrosis (CF).

- Solutions:

- Clinical History: Carefully re-evaluate the patient's recent history for signs of infection and delay testing for 2-4 weeks post-illness.

- Exclude CF: Ensure cystic fibrosis has been ruled out before interpreting low nNO as indicative of PCD [35].

- Nasal Inspection: Examine the nasal passages for obstruction, polyps, or signs of recent bleeding. Refer to an ENT specialist if obstruction is suspected [36].

- Repeat Testing: Schedule a repeat measurement on a separate day when confounding factors are minimized.

Problem 3: High Variability Between Measurements on the Same Patient

- Potential Causes: Inconsistent technique, nasal cycle variations, or equipment issues.

- Solutions:

- Standardize Technique: Ensure the same operator performs the test using a consistent protocol. The manoeuvre should be repeated twice in each nostril to assess repeatability [36].

- Patient Preparation: Instruct the patient to blow their nose thoroughly before testing. Gentle saline lavage may be used if needed, taking care not to injure the mucosa [36].

- Check Equipment: Inspect the nasal olive and sampling lines for blockages or leaks. Ensure a good seal is formed in the nostril.

nNO Diagnostic Accuracy Data

The following table summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of nNO measurement from a large meta-analysis, comparing different reference standards [35].

Table 1: Summary of nNO Diagnostic Accuracy for PCD Diagnosis [35]

| Reference Standard | Number of Studies | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) | Negative Likelihood Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM alone or EM/Genetic | 12 | 97.6% (92.7–99.2) | 96.0% (87.9–98.7) | 24.3 (7.6–76.9) | 0.03 (0.01–0.08) |

| EM and/or Genetic | 7 | 96.3% (88.7–98.9) | 96.4% (85.1–99.2) | 26.5 (5.9–119.1) | 0.04 (0.01–0.12) |

Experimental Protocol: nNO Measurement via Exhalation Against Resistance

This protocol is based on ERS technical standards and manufacturer guidelines for devices like the NIOX VERO [38] [36].

Principle: To aspirate air from the nasal cavity while the velum is closed, preventing contamination from low-NO air from the lower airways and providing a representative sample of nasal NO.

Equipment and Reagents:

- Chemiluminescence or approved electrochemical nNO analyzer (e.g., NIOX VERO)

- Nasal sampling kit (including nasal olives in adult and pediatric sizes)

- Disposable patient filters and mouth resistors/party blowers

- Computer with associated software for data analysis (if applicable)

Procedure:

- Patient Preparation:

- Contraindications: Do not perform if there is evidence of active nasal bleeding.

- Have the patient blow their nose thoroughly to clear nasal passages.

- Delay testing for 2-4 weeks after a respiratory infection or nasal surgery.

- The patient should avoid nitrogen-rich foods and strenuous exercise for 2 hours prior to testing [39].

Equipment Setup:

- Connect the nasal olive to the analyzer's sampling port.

- For the exhalation against resistance method, attach a new patient filter to the breathing handle. Insert a nasal restrictor into the filter.

Measurement:

- Seat the patient comfortably.

- Select the appropriate sized nasal olive and ensure an airtight seal in the nostril. Align the sampling hole with the nasal passage.

- Pass the breathing handle with the attached resistor to the patient.

- Instruct the patient to: a. Inhale deeply to total lung capacity. b. Seal their lips tightly around the patient filter. c. Exhale steadily and continuously for the duration required by the device (e.g., 30 seconds).

- Initiate the measurement on the analyzer.

- The device will aspirate nasal air for a set period (e.g., 30 seconds) and then analyze the sample.

Data Analysis:

- For chemiluminescence analyzers: Observe the real-time tracing. A valid plateau is defined as a stable exhalation for ≥3 seconds with ≤10% variation. Manually select this plateau for the final value [36].

- For electrochemical analyzers: The device may provide a result automatically. If the software allows, visualize the curve to check for a stable exhalation profile.

Reporting:

- Report the nNO value in parts per billion (ppb) or nanoliters per minute (nL/min).

- Note the measurement method (e.g., ER-nNO), the nostril tested, and the ambient NO level if recorded.

nNO Testing Workflow

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for utilizing nNO measurement in the PCD diagnostic pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for nNO Measurement in Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence Analyzer (e.g., CLD 88 sp, Sievers NOA) | High-accuracy device considered the gold-standard for nNO measurement in research settings; allows real-time curve visualization [36]. |

| Electrochemical Analyzer (e.g., NIOX VERO) | Portable, cost-effective device suitable for clinical settings; simpler to operate but with limitations in real-time data inspection [38] [36]. |

| Nasal Sampling Kit | Includes tubing and disposable nasal olives of various sizes to create an airtight seal in the nostril during aspiration [38]. |

| Mouth Resistor / Party Blower | Used during the exhalation against resistance manoeuvre to generate back pressure, ensuring velum closure [36]. |

| Disposable Patient Filters | Hygienic barrier placed between the breathing handle/mouthpiece and the patient to prevent cross-contamination [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is an integrated diagnostic approach for PCD, and why is it necessary? An integrated diagnostic approach for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) uses a combination of tests rather than relying on a single method. This is necessary because no single test is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis in all cases. Genetic testing can identify known mutations, but up to 30% of patients with a clinical PCD picture have no identifiable mutations in known genes. Conversely, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) has a diagnostic sensitivity of only about 70-75%, as a significant proportion of genetically confirmed PCD cases show normal ciliary ultrastructure [1] [40]. Integrating multiple methods maximizes sensitivity and diagnostic confidence.

2. How can we diagnose PCD when TEM results are normal? A normal TEM result does not rule out PCD. In cases of strong clinical suspicion but normal ultrastructure, the diagnostic process should proceed with other modalities. Key steps include:

- Genetic Testing: This is crucial for identifying mutations in genes known to cause PCD with normal ultrastructure, such as DNAH11 and DRC1 [40].

- Immunofluorescence (IF) Microscopy: This technique can detect the absence or mislocalization of specific ciliary proteins, which can confirm a diagnosis even when the structure appears normal under TEM [40].

- Functional Tests: High-speed video microscopy (HSVM) to analyze ciliary beat pattern and frequency, alongside nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, provides functional data to support the diagnosis [40].

3. What are the common pitfalls in interpreting TEM results, and how can we avoid them? Common pitfalls include misinterpreting secondary ciliary defects (caused by infection or inflammation) as primary defects and a lack of standardized evaluation. To avoid these:

- Follow International Guidelines: Adhere to the international consensus guidelines for TEM diagnosis, which classify defects as Class 1 (confirmatory, e.g., outer dynein arm defects) or Class 2 (suggestive but requiring confirmation) [1] [40].

- Quantitative Analysis: Evaluate a sufficient number of ciliary cross-sections (e.g., >50) and report defects as a percentage. Defects in <10% of cilia are often within the normal range, while Class 1 defects are typically present in >50% of cilia [1].

- Repeat Testing: In cases of acute infection, consider repeating the nasal brushing after the infection has resolved to distinguish primary from secondary defects [1].

4. How do you validate a new integrated diagnostic algorithm in a research setting? Validation involves a prospective comparison of the algorithm's performance against a robust clinical gold standard. The process, as demonstrated in other medical fields, includes [41] [42]:

- Defining a Gold Standard: The final diagnosis is made by a panel of specialists based on a comprehensive review of all available data, including history, all test results, and imaging.

- Calculating Performance Metrics: The algorithm's diagnoses are compared to the gold standard to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV).

- Identifying Limitations: The validation study should identify specific conditions that lead to false positives or false negatives, allowing for further refinement of the algorithm.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconclusive Results from a Multi-Test Diagnostic Workflow

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Conflicting results between tests (e.g., genetic variant of uncertain significance (VUS) and normal TEM). | A rare or novel genetic mutation not previously associated with PCD; secondary ciliary damage masking a primary defect. | 1. Functional Corroboration: Prioritize functional tests like HSVM and nNO. An abnormal ciliary beat pattern strongly supports a PCD diagnosis.2. Immunofluorescence: Perform IF staining targeted by the genetic result to see if the protein product is affected.3. Segregation Analysis: Test parents/siblings for the genetic variant to help determine its pathogenicity. |

| All test results are borderline or normal, but clinical phenotype is highly suggestive. | The patient may have a PCD-causing gene not covered by the genetic panel or a non-genetic mimic of PCD. | 1. Expand Genetic Analysis: Consider whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing.2. Expert Review: Have TEM images and HSVM videos re-evaluated by a central reference laboratory.3. Clinical Follow-up: Monitor disease progression and re-evaluate after a period of time or after an infection has cleared. |

Issue 2: Poor-Quality Nasal Brush Biopsy for TEM

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no ciliated cells in the sample. | Insufficient brushing technique; sample taken from a non-ciliated area; sample processing artifacts. | 1. Standardize Collection: Ensure the brush scrapes the inferior surface of the inferior turbinate firmly.2. Immediate Fixation: Place the brush immediately in buffered glutaraldehyde to preserve ultrastructure [1].3. Proper Handling: Gently clean the brush of adherent mucus under a dissecting microscope before processing to avoid loss of cells. |

| Poor preservation of ciliary ultrastructure (e.g., disrupted microtubules). | Delay in fixation; use of incorrect fixative or buffer; osmotic imbalance during processing. | 1. Optimize Fixative: Use 2.5% EM-grade glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, osmotically adjusted with sucrose [1].2. Minimize Delay: Process the sample from collection to resin embedding as quickly as possible.3. Expert Processing: Ensure the TEM processing protocol, including dehydration and resin embedding, is performed by an experienced technician. |

Performance of Diagnostic Modalities in PCD

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major PCD diagnostic tests, highlighting the need for an integrated approach.

| Diagnostic Method | Primary Function | Key Strengths | Inherent Limitations | Reported Sensitivity/Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Visualizes ciliary ultrastructure | Identifies specific structural defects (e.g., ODA/IDA loss); considered a definitive test when Class 1 defects are found [40]. | Cannot detect functional defects; ~30% of PCD cases have normal ultrastructure; requires expertise and expensive infrastructure [1] [40]. | ~70-75% [1] [40] |

| Genetic Testing | Identifies mutations in PCD-associated genes | High specificity; can provide a definitive diagnosis and inform genotype-phenotype correlations. | ~20-30% of patients have no identified mutations; variants of uncertain significance (VUS) can be difficult to interpret [40]. | ~70-80% [40] |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVM) | Analyzes ciliary beat pattern and frequency | Directly assesses ciliary function; can diagnose PCD in cases with normal ultrastructure. | Requires specialized equipment and expert analysis; results can be affected by secondary inflammation. | Varies by center and expertise |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | Measures nasal NO levels | Excellent screening tool; very low nNO is highly suggestive of PCD. | Not diagnostic on its own; requires patient cooperation; can be falsely normal in some PCD cases. | High sensitivity for screening |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized TEM Analysis for PCD Diagnosis

Principle: This protocol outlines the standardized processing and evaluation of nasal brush biopsies for the ultrastructural diagnosis of PCD, based on international consensus guidelines [1] [40].

Materials:

- Nasal cytology brush (e.g., flexible nylon laparoscopy brush)

- 2.5% EM-grade glutaraldehyde in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer (with osmotic adjustment)

- 1% buffered osmium tetroxide

- Graded ethanol series (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, 100%)

- Agar Scientific low viscosity resin

- Ultramicrotome

- Transmission Electron Microscope

Methodology:

- Sample Collection: After obtaining informed consent, perform a nasal brush biopsy from the inferior surface of the inferior turbinate.

- Immediate Fixation: Immediately place the brush into cold 2.5% glutaraldehyde fixative for a minimum of 2 hours.

- Sample Cleaning: Under a dissecting microscope, gently clean the brush fibers in fresh fixative to remove mucus and collect cell fragments.

- Post-fixation and Processing:

- Rinse samples 3 times in buffer (30 min each).

- Post-fix in 1% buffered osmium tetroxide for 1 hour.

- Rinse in buffer (3 x 30 min) and then in pure water for 5 min.

- Dehydrate in a graded ethanol series (10% to 100%), 30 minutes per step.

- Resin Infiltration and Embedding:

- Infiltrate with low viscosity resin using a resin:ethanol series (1:3, 1:1, 3:1) and then pure resin (overnight).

- Embed samples in fresh resin in BEEM capsules and polymerize at 70°C.

- Sectioning and Staining: Cut 70 nm ultrathin sections using an ultramicrotome. Double-stain sections with aqueous uranyl acetate (15 min) and Reynold's lead citrate (10 min).

- Imaging and Analysis:

- Examine grids under the TEM at 120kV.

- Systematically capture images of multiple ciliary cross-sections.

- Evaluate a minimum of 50-100 ciliary cross-sections per patient.

- Classify defects according to international guidelines [40]:

- Class 1 Defects (Confirmatory): Hallmark defects (e.g., ODA, ODA+IDA loss) in >50% of cilia.

- Class 2 Defects (Suggestive): Defects requiring confirmation by another method (e.g., defects in 25-50% of cilia, central complex defects).

Diagnostic Workflow and Research Reagents

Integrated PCD Diagnostic Algorithm

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing PCD, emphasizing how methods are combined to achieve maximum sensitivity, especially for patients with normal ultrastructure.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and reagents used in the TEM and genetic diagnostic protocols.

| Item | Function/Application in PCD Research | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde (EM-grade) | Primary fixative for TEM; cross-links proteins to preserve ultrastructure. | Use at 2.5% in 0.1M sodium cacodylate buffer, osmotically adjusted [1]. |

| Osmium Tetroxide | Post-fixative for TEM; stabilizes lipids and provides electron density. | Typically used at 1% concentration after aldehyde fixation [1]. |

| Low Viscosity Resin | Embedding medium for TEM; allows for cutting of ultra-thin sections. | Agar Scientific low viscosity resin is a common choice [1]. |

| Nasal Cytology Brush | For obtaining ciliated epithelial cell samples from the nasal mucosa. | A flexible nylon brush with a twisted wire shaft (e.g., WS-1812XA3) [1]. |

| PCD Genetic Panel | Targeted next-generation sequencing to identify mutations in known PCD genes. | Panels should include common genes (e.g., DNAH5, CCDC39/40) and genes associated with normal ultrastructure (e.g., DNAH11, DRC1) [40]. |

| Antibodies for IF | For immunofluorescence microscopy to localize specific ciliary proteins. | Antibodies against proteins like DNAH5 (ODA) or GAS8 (nexin link) can confirm absent/mislocalized proteins [40]. |

Overcoming Diagnostic Hurdles and refining the Diagnostic Pathway

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) diagnosis presents significant challenges, particularly in cases with normal ultrastructure where false negatives frequently occur. International guidelines recommend a multi-faceted diagnostic approach since no single test provides 100% certainty [3]. The limitations of individual modalities become particularly problematic in research settings where accurate phenotyping is essential for valid results. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for researchers encountering false negatives in PCD diagnostic assays, with special emphasis on patients with normal ultrastructure who may be misclassified as disease-negative.

Understanding False Negatives in PCD Diagnostics

The Scope of the Problem

False negatives in PCD research occur when patients with the disease receive negative test results, potentially excluding them from studies or leading to incorrect conclusions. Several factors contribute to this problem:

- Normal Ultrastructure Cases: Approximately 15-30% of genetically-confirmed PCD cases exhibit normal ciliary ultrastructure on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) [8] [43] [23]. One study of 200 confirmed PCD subjects found 67 (33.5%) had normal ultrastructure (NU) but abnormal ciliary motility [43].

- Genetic Heterogeneity: Over 40 PCD-associated genes have been identified, but current genetic panels account for only 60-70% of cases [8]. Furthermore, clinical testing is available for only about 6,000 of an estimated 20,000 human genes [44].