Optimizing Homology-Directed Repair Template Design for Precise Gene Correction: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing effective homology-directed repair (HDR) templates for precise gene editing.

Optimizing Homology-Directed Repair Template Design for Precise Gene Correction: A Strategic Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on designing effective homology-directed repair (HDR) templates for precise gene editing. Covering foundational principles to advanced optimization strategies, it explores the mechanistic basis of HDR, compares single-stranded and double-stranded DNA donors, and details cutting-edge approaches to enhance efficiency—including novel HDR-boosting modules and small molecule inhibitors. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting for common pitfalls like low efficiency and imprecise integration, alongside rigorous validation methods to ensure editing accuracy and assess genomic integrity, ultimately supporting the advancement of therapeutic gene correction applications.

Understanding Homology-Directed Repair: Core Principles and Cellular Mechanisms

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized genetic research by providing scientists with unprecedented precision in genome editing. However, the CRISPR-Cas9 system itself does not perform the genetic modification; it merely creates a precise double-strand break (DSB) at a specific genomic location [1]. The actual genetic editing occurs through the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, which are activated in response to this damage [2]. Understanding these repair pathways is fundamental to harnessing the full potential of genome editing for research and therapeutic applications.

Cells possess multiple DNA repair pathways to maintain genomic integrity, with the two primary mechanisms for repairing DSBs being Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [1] [2]. These pathways operate concurrently and competitively within the cell, with their relative activities determining the outcome of any genome editing experiment. The choice between these pathways is not merely random but is influenced by factors including cell cycle stage, cell type, and the specific nuclease platform employed [3]. For researchers aiming to achieve precise gene corrections, understanding this intricate balance at the cellular repair crossroads is essential for designing effective experimental strategies.

DNA Repair Pathways: Mechanisms and Applications

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

Mechanism: NHEJ is an error-prone DNA repair pathway that functions by directly ligating broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template [1]. This pathway initiates when the Ku heterodimer (Ku70/Ku80) recognizes and binds to the DSB ends, forming a complex that recruits additional core NHEJ factors including DNA-PKcs, Artemis, XLF, XRCC4, and DNA Ligase IV [4] [5]. The process can proceed through distinct sub-pathways depending on the end structures: blunt-end ligation, nuclease-dependent processing, or polymerase-dependent repair that may incorporate RNA or DNA nucleotides [4] [6].

Applications: NHEJ is particularly suited for gene knockout studies where the goal is to disrupt gene function [1] [2]. The inherent error-prone nature of NHEJ often results in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site, which can lead to frameshift mutations, premature stop codons, and ultimately, loss of gene function [2]. Although considered less precise, NHEJ can also be leveraged for gene knock-in strategies with appropriate experimental designs [1].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

Mechanism: HDR is a precise repair mechanism that utilizes homologous DNA sequences as templates for accurate DSB repair [1]. The process begins with 5' end resection of the break, creating 3' single-stranded overhangs that serve as substrates for strand invasion into a homologous donor template [7]. This leads to the formation of a displacement loop (D-loop) structure, followed by DNA repair synthesis using the donor as a template [7]. Key HDR subpathways include Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA), which exclusively yields non-crossover products, and the more complex Double-Strand Break Repair (DSBR) pathway that can result in crossover events [7].

Applications: HDR is the preferred pathway for precise genetic modifications, including introduction of specific point mutations, gene knock-ins, and creation of tagged protein versions [1] [2]. To harness HDR, researchers design donor templates containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms complementary to the sequences surrounding the DSB [1] [7]. This approach enables sophisticated genome engineering applications such as disease modeling, functional protein studies with fluorescent tags, and therapeutic gene correction [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major DNA DSB Repair Pathways

| Feature | NHEJ | HDR | MMEJ | SSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template Required | No | Yes (homologous donor) | No (uses microhomology) | Yes (uses homologous repeats) |

| Fidelity | Error-prone (generates INDELs) | High-fidelity | Error-prone (deletions) | Error-prone (deletions) |

| Primary Factors | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XLF, XRCC4-LigIV | RAD51, BRCA2, RAD52, RPA | PARP1, Polθ (POLQ), LigI/III | RAD52, ERCC1 |

| Cell Cycle Preference | Active throughout, preferred in G1 | Active in S and G2 phases | Active throughout | Active throughout |

| Primary Applications in Gene Editing | Gene knockouts, gene disruption | Precise edits, knock-ins, point mutations | - | - |

| Key Inhibitors/Enhancers | Inhibitors: DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer) | Enhancers: HDRobust combination | Inhibitors: ART558 (POLQ inhibitor) | Inhibitors: D-I03 (RAD52 inhibitor) |

Alternative Repair Pathways: MMEJ and SSA

Beyond the classical NHEJ and HDR pathways, cells possess additional repair mechanisms that significantly impact genome editing outcomes. Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) utilizes short homologous sequences (2-20 bp) flanking the DSB to guide repair, often resulting in deletions [8] [9]. This pathway depends on polymerase theta (Polθ, encoded by POLQ) and represents a backup pathway when NHEJ is compromised [5]. Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) requires longer homologous repeats and is mediated by RAD52, which anneals complementary single-stranded DNA regions [8]. Both pathways contribute to imprecise editing outcomes and compete with HDR for DSB repair, presenting challenges for precise genome editing that must be addressed experimentally [8].

Quantitative Analysis of Editing Outcomes

Understanding the quantitative relationships between different repair pathways enables researchers to predict and optimize editing outcomes. Systematic studies using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) assays have revealed that the HDR/NHEJ ratio is highly dependent on multiple factors including gene locus, nuclease platform, and cell type [3]. Contrary to the common assumption that NHEJ generally dominates over HDR, research has demonstrated that certain conditions can yield more HDR than NHEJ events [3].

The competition between repair pathways is further illustrated by recent studies showing that even with NHEJ inhibition, perfect HDR efficiency remains limited due to interference from alternative pathways like MMEJ and SSA [8]. Quantitative analysis reveals that imprecise integration can account for nearly half of all integration events despite NHEJ inhibition, highlighting the significant challenge these alternative pathways present for precise genome editing [8].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Outcomes Across Experimental Conditions

| Experimental Condition | HDR Efficiency (%) | NHEJ Efficiency (%) | HDR/NHEJ Ratio | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Editing (HEK293T cells) | Varies by locus: 5-30% | Varies by locus: 3-25% | 0.5-3.0 | Highly variable across loci [3] |

| With NHEJ Inhibition Only | 16.8-63% | Significantly reduced | Increased ~3-fold | Locus-dependent effect [8] [3] |

| With MMEJ Inhibition Only | 21-41% | Moderate reduction | ~1.5-2x increase | Strongly locus-dependent [8] |

| With Combined NHEJ+MMEJ Inhibition (HDRobust) | 37-93% (median 60%) | Drastically reduced to ~1.7% | >35x increase | Highest purity of HDR outcomes [9] |

| With SSA Inhibition Only | No substantial change | No substantial change | Minimal change | Effect depends on DNA end structure [8] |

Experimental Protocols

ddPCR for Simultaneous HDR and NHEJ Quantification

Principle: This protocol utilizes droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) technology to simultaneously quantify HDR and NHEJ events at endogenous genomic loci with high sensitivity [10] [3]. The method partitions PCR reactions into approximately 20,000 nanoliter-sized droplets, enabling absolute quantification of discrete alleles through allele-specific hydrolysis probes [10].

Procedure:

- Design Hydrolysis Probes and Primers:

- Design a reference FAM probe that binds distant from the cut site to quantify total genome copies [10].

- Design a HEX-labeled NHEJ probe that binds at the nuclease cut site; loss of HEX signal indicates NHEJ events [10].

- Design a second FAM-labeled HDR probe that binds only to the precisely edited sequence [10].

- In some cases, include a dark, non-extendible oligonucleotide blocker to prevent cross-reactivity of HDR probes with wild-type sequences [10] [3].

- Position primers to flank the target region with 75-125 bp on each side, ensuring at least one primer binds outside the donor sequence [10].

Prepare Reaction Mix:

- Combine 100-150 ng of genomic DNA, ddPCR Supermix for Probes, allele-specific probe/primer assay mixtures, and 2-4 units of a restriction enzyme that doesn't cut within the amplicon [10].

- Include appropriate controls: wild-type genomic DNA, synthetic HDR controls (with point mutation), and NHEJ controls (with small deletions) [10].

Generate Droplets and Amplify:

- Generate droplets using the QX200 Droplet Generator [10].

- Perform PCR amplification with optimized annealing temperature determined empirically [10] [3].

- Seal the plate and run the thermal cycling protocol: 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and the optimized annealing temperature for 60 s, with a final 98°C for 10 min [10].

Analyze Results:

HDRobust for High-Precision Editing

Principle: The HDRobust protocol combines transient inhibition of both NHEJ and MMEJ pathways to dramatically enhance HDR efficiency and purity by minimizing competing repair pathways [9].

Procedure:

- Inhibit Repair Pathways:

- To inhibit NHEJ: Use small molecule inhibitors targeting DNA-PKcs (such as those in the Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) [8] [9].

- To inhibit MMEJ: Apply POLQ inhibitors such as ART558 [8] [9].

- Treatment duration is typically 24 hours post-electroporation, coinciding with the timeframe when HDR primarily occurs [8].

Perform Genome Editing:

Validate Editing Outcomes:

- Extract genomic DNA 3-4 days post-editing for most cell lines, or up to 6 days for loci with lower editing efficiency [3].

- Analyze editing outcomes through long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio) or the ddPCR protocol above [8] [3].

- Classify sequences using computational frameworks like knock-knock to categorize perfect HDR, imprecise integration, and indel outcomes [8].

Pathway Interplay and Strategic Manipulation

The complex interplay between DNA repair pathways significantly influences genome editing outcomes. Several strategic approaches have been developed to manipulate this balance in favor of desired editing outcomes.

Strategies to Enhance HDR Efficiency

Cell Cycle Synchronization: Since HDR is most active in S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, synchronizing cells to these phases can enhance HDR efficiency [2]. This can be achieved through chemical treatments such as nocodazole or through serum starvation and stimulation protocols.

Modification of Donor Templates: Optimizing donor design significantly impacts HDR efficiency. Key considerations include:

- Using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for small edits (<50 bp) with 30-50 bp homology arms [7].

- Employing double-stranded DNA templates with 500-1000 bp homology arms for larger insertions [7].

- Incorporating blocking mutations in the donor template to disrupt the gRNA binding site or PAM sequence and prevent recurrent cleavage [7].

- Positioning the desired edit as close as possible to the DSB site, ideally within 10 bp [7].

Small Molecule Inhibition: The HDRobust approach demonstrates that combined inhibition of NHEJ and MMEJ using small molecules can increase HDR efficiency to as high as 93% in some contexts [9]. This combined inhibition approach substantially reduces indels at the target site and minimizes unintended genomic changes [9].

Experimental Planning Considerations

When designing genome editing experiments, researchers should consider several key factors that influence repair pathway balance:

Cell Type Selection: Different cell types exhibit varying inherent preferences for DNA repair pathways. For example, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) often show different HDR/NHEJ ratios compared to transformed cell lines like HEK293T or HeLa cells [3].

Nuclease Platform Choice: Different nuclease platforms influence repair outcomes. Cas9 nickases (Cas9-D10A and Cas9-H840A) and FokI-dCas9 systems produce different DSB structures that can affect the balance between HDR and NHEJ [3]. The specific nuclease used should be selected based on the desired editing outcome.

Timing Considerations: The timing of donor template delivery relative to nuclease activity affects HDR efficiency. Donor templates should be present during peak nuclease activity and throughout the critical repair window, typically the first 24 hours post-transfection [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for DNA Repair and Genome Editing Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Wildtype Cas9, Cas9-D10A nickase, Cas9-H840A nickase, FokI-dCas9, Cas9-HiFi, Cpf1-Ultra | Induce controlled DNA breaks at specific genomic loci [3] [9] |

| Donor Templates | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), double-stranded DNA plasmids, PCR-generated linear dsDNA, long ssDNA from Easi-CRISPR | Provide homologous templates for HDR-mediated precise editing [7] |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi), ART558 (POLQ/MMEJi), D-I03 (RAD52/SSAi), NU7441 (DNA-PKcsi) | Modulate repair pathway balance to favor HDR over competing pathways [8] [9] |

| Detection Assays | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) with custom probe sets, long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio), knock-knock computational framework | Precisely quantify and characterize editing outcomes including HDR, NHEJ, and imprecise integration events [10] [8] [3] |

| Delivery Tools | Lipofectamine 2000, Nucleofector systems with specific kits (e.g., Human Stem Cell Nucleofector Kit-1) | Efficiently deliver editing components to relevant cell types [3] |

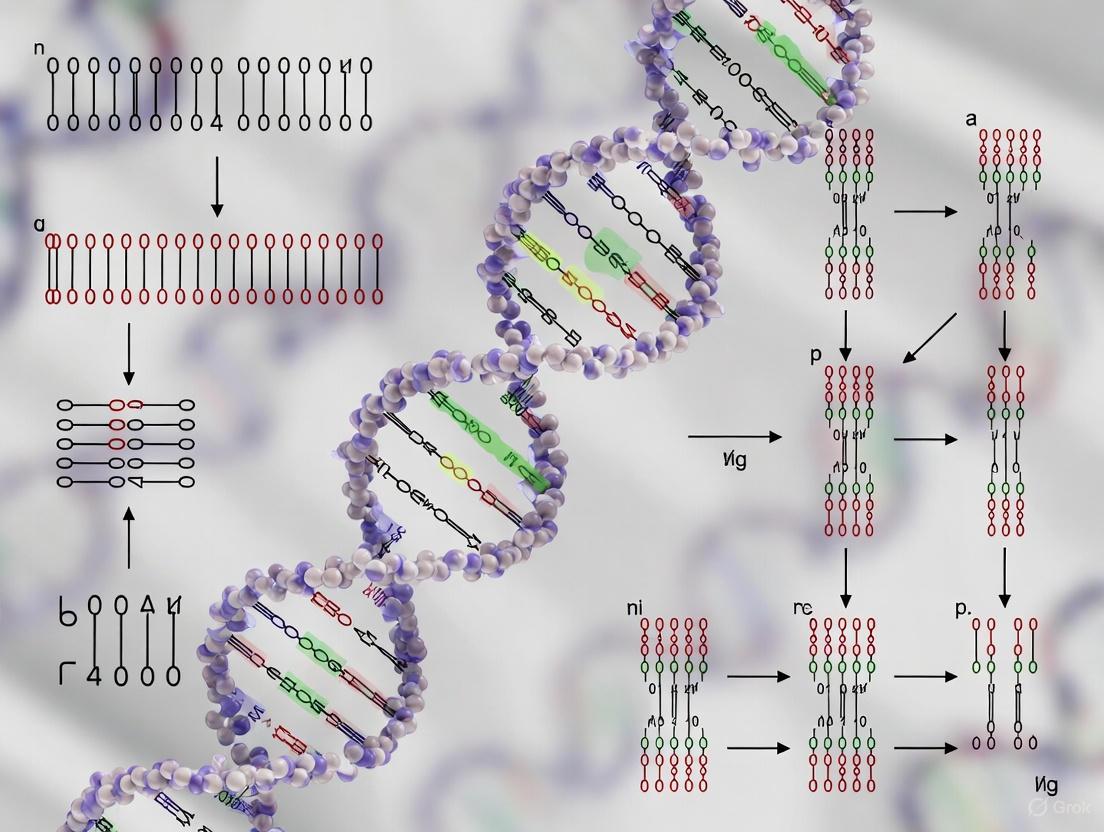

Visualizing DNA Repair Pathway Relationships and Experimental Workflow

The intricate interplay between DNA repair pathways presents both challenges and opportunities for precision genome editing. By understanding the mechanistic basis of these pathways and implementing strategic approaches to modulate their activities, researchers can significantly enhance the efficiency and fidelity of homology-directed repair. The protocols and reagents outlined here provide a roadmap for navigating the cellular repair crossroads toward successful implementation of precise genetic modifications for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Homology-directed repair (HDR) is a precise DNA repair mechanism that utilizes homologous sequences to accurately repair double-strand breaks (DSBs). In genome editing, this process is co-opted by providing exogenous donor repair templates (DRTs) to introduce specific genetic modifications. While HDR holds tremendous promise for precise gene correction, its efficiency remains challenging due to competition with error-prone repair pathways and cell cycle dependency. This application note details the molecular mechanics of HDR, from initial end resection to final strand invasion, and provides optimized protocols and reagent solutions to enhance HDR efficiency for research and therapeutic development.

Homology-directed repair represents one of the two primary mechanisms for repairing DNA double-strand breaks in eukaryotic cells, distinguished from the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway by its requirement for a homologous template and its ability to achieve error-free repair [7]. The HDR process is generally restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, unlike NHEJ which operates throughout the entire cycle, contributing to its inherently lower efficiency in somatic plant and mammalian cells [11]. Several distinct HDR pathways exist, all sharing common initial steps but diverging in their resolution mechanisms.

The critical HDR pathways include:

- Synthesis-Dependent Strand Annealing (SDSA): A conservative mechanism exclusively yielding non-crossover events where newly synthesized sequences are retained by the original damaged DNA molecule [7].

- Classical Double-Strand Break Repair (DSBR): Involves formation of double Holliday junctions that can resolve via crossover or non-crossover events [7].

- Break-Induced Repair (BIR): Characterized by repair from a single-ended DSB, involving extensive DNA synthesis and potentially leading to loss of heterozygosity [7].

Understanding these pathways provides the foundation for optimizing HDR template design and editing strategies for precise gene correction research.

The Molecular Mechanics of HDR

Initial End Resection and Pathway Commitment

The HDR cascade initiates with the recognition of a double-strand break by cellular sensor proteins. The 5' ends on both sides of the break are then resected by nucleases to create 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs, a critical step that commits the repair process to the HDR pathway rather than NHEJ [7]. This ssDNA serves as both a substrate for proteins required for strand invasion and a primer for DNA repair synthesis. The length and quality of this resection directly influence subsequent HDR efficiency, with more extensive resection generally favoring homologous recombination over competing repair pathways.

Strand Invasion and D-Loop Formation

The central step in HDR involves the 3' ssDNA overhang invading a homologous donor sequence, displacing one strand of the homologous DNA to form a structure known as the displacement loop (D-loop) [7]. This process is mediated by recombinase enzymes such as Rad51 in mammalian cells, which form nucleoprotein filaments on the ssDNA and facilitate the search for homology. The invading 3' end then serves as a primer for DNA repair synthesis using the donor template. The stability and efficiency of this strand invasion step are crucial determinants of overall HDR success and are influenced by factors including homology arm length, strandedness of the donor template, and local chromatin environment.

The following diagram illustrates the core HDR pathway from end resection through strand invasion:

Pathway Resolution and Template Dissociation

Following successful strand invasion and DNA synthesis, the recombination intermediates resolve through distinct mechanisms depending on the specific HDR pathway engaged. In SDSA, the newly synthesized DNA is displaced from the template and anneals to the complementary single-stranded region on the other side of the original break, exclusively producing non-crossover products [7]. In the DSBR pathway, the second end of the break is captured, leading to the formation of double Holliday junctions that can be resolved through cleavage in either a crossover or non-crossover configuration. The resolution pathway employed has significant implications for genetic stability, with non-crossover outcomes generally preferred for precise genome editing applications to maintain chromosomal integrity.

Donor Template Design and Optimization

The structure and composition of donor repair templates significantly impact HDR efficiency. Recent systematic studies have quantified the effects of various DRT parameters, providing data-driven guidance for experimental design.

Table 1: Impact of Donor Template Structure on HDR Efficiency

| Template Parameter | Experimental Findings | Optimal Design Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Strandedness | ssDNA donors in target orientation outperformed dsDNA configurations, achieving 1.12% HDR efficiency in potato protoplasts [11]. | Single-stranded DNA for short edits (<200 nt); dsDNA for larger inserts. |

| Homology Arm Length | HDR efficiency appeared independent of HA length (30-97 nt tested); ssDNA with 30 nt HAs achieved targeted insertions in 24.89% of reads [11]. | 30-50 nt for ssDNA donors; 500-1000 bp for dsDNA plasmid donors [7]. |

| Sequence Modifications | Donors with proprietary Alt-R HDR modifications showed increased HDR rates compared to unmodified or PS-modified templates [12]. | Chemically modified donors for enhanced nuclease stability and cellular persistence. |

| Orientation (ssDNA) | ssDNA in "target" orientation (coinciding with sgRNA-recognized strand) outperformed "non-target" orientation [11]. | Target orientation for ssDNA donors relative to sgRNA binding strand. |

Strategic Considerations for Template Design

Beyond the parameters quantified in Table 1, several additional factors critically influence HDR success. The insertion site should be positioned as close as possible to the DSB site, ideally within 10 base pairs, to maximize recombination efficiency [7]. Furthermore, the donor template should be designed to disrupt the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) site or guide RNA recognition sequence to prevent recurrent Cas9 cleavage after successful HDR events [7]. For larger insertions (>200 bp), double-stranded DNA templates such as linearized plasmids or PCR fragments are generally preferred, though novel methods like Easi-CRISPR can produce long single-stranded DNA donors that have demonstrated 25-50% editing efficiency in mouse models compared to 1-10% with dsDNA [7].

Experimental Protocols for HDR Efficiency Analysis

Protoplast Transfection and NGS Quantification

This protocol enables rapid assessment of HDR efficiency and DRT optimization in plant systems, adapted from potato protoplast studies [11].

Materials:

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes (e.g., Alt-R S.p. HiFi Cas9 V3)

- Donor repair templates (ssDNA or dsDNA)

- Plant protoplasts (e.g., potato cultivar Kuras)

- Electroporation system (e.g., Lonza Nucleofector)

- Next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina MiSeq)

Procedure:

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex 2 µM Cas9 nuclease with crRNA and tracrRNA at equimolar ratios in appropriate buffer. Incubate 15-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Protoplast Transfection: Electroporate 2×10^5 protoplasts with 2 µM RNP complexes and 0.5 µM donor template using optimized settings.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells 48-72 hours post-transfection. Isolate genomic DNA using standard silica-column or magnetic bead-based methods.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Amplify target regions with barcoded primers. Sequence on Illumina platform (v2 chemistry, 150 bp paired-end recommended).

- Data Analysis: Align sequences to reference genome. Quantify HDR efficiency as percentage of reads containing precise edits.

Expected Results: Using this approach with ssDNA donors and 30 nt homology arms, researchers observed HDR efficiency of 1.12% of sequencing reads, with targeted insertions in up to 24.89% of reads via precise and imprecise repair pathways [11].

CLEAR-time dPCR for Absolute HDR Quantification

CLEAR-time dPCR (Cleavage and Lesion Evaluation via Absolute Real-time dPCR) provides absolute quantification of editing outcomes in human stem and primary cells, offering advantages for clinical applications [13].

Materials:

- Digital PCR system (e.g., Bio-Rad QX200)

- Multiplexed probe assays (FAM/HEX labeled)

- Edited cell populations (e.g., HSPCs, iPSCs, T-cells)

- Genomic DNA isolation kit

Procedure:

- Assay Design:

- Design "Edge" assay with primers flanking target site and two probes (cleavage probe over DSB site, distal probe 25 bp away).

- Design "Flanking" assay with two amplicons flanking cleavage site, each with internal probe.

- Include reference assays on non-targeted chromosomes for normalization.

Genomic DNA Preparation: Extract high-quality genomic DNA from edited cells 72 hours post-transfection. Digest with restriction enzymes if assessing donor concatemers.

dPCR Setup: Partition 20 ng genomic DNA with assay mix into 20,000 droplets. Amplify with optimized thermal cycling conditions.

Data Analysis: Quantify absolute copy numbers of wildtype, indels, large deletions, and HDR events using Poisson correction.

Expected Results: CLEAR-time dPCR can quantify up to 90% of loci with unresolved DSBs and precisely measure DNA repair precision, revealing prevalent scarless repair after DSBs in clinically relevant cells [13].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Experiments

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Donor Templates | Alt-R HDR Donor Oligos (IDT); GenExact ssDNA (GenScript); GenWand dsDNA (GenScript) | High-quality, sequence-verified templates with chemical modifications to enhance stability and HDR efficiency [12] [14]. |

| HDR Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2; Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein | Small molecule or protein-based reagents that inhibit NHEJ pathway or promote HDR by blocking 53BP1, increasing precise knock-in efficiency by up to 2X [12]. |

| Editing Efficiency Controls | Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 HPRT Positive Controls; Non-targeting controls | Validated systems to determine baseline HDR efficiency and experimental performance across species [12]. |

| Analysis Tools | CLEAR-time dPCR [13]; Repair-seq [15] | Advanced methods for absolute quantification of editing outcomes and systematic mapping of DNA repair pathways. |

HDR Enhancement Strategies

Multiple strategies exist to enhance HDR efficiency beyond optimal template design. Pathway modulation through inhibition of competing NHEJ using small molecules (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2) or proteins (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein) can increase HDR efficiency by up to 2-fold across established and hard-to-edit primary cells [12]. Cell cycle synchronization to enrich for S/G2 phase cells can significantly boost HDR rates, as HDR is naturally restricted to these phases. Additionally, modification of donor templates with phosphorothioate linkages or proprietary stabilization chemistries can enhance cellular persistence and nuclear availability, further improving recombination frequency [12].

The following workflow illustrates an integrated experimental approach for HDR enhancement:

The molecular machinery of HDR, from initial end resection through strand invasion, represents a sophisticated cellular process that can be harnessed for precise genome editing. Strategic donor template design—prioritizing single-stranded DNA, appropriate homology arm length, and chemical modifications—combined with pathway modulation and sensitive quantification methods can significantly enhance HDR efficiency. While challenges remain in achieving high-frequency HDR across all cell types, the protocols and reagents detailed herein provide a robust foundation for advancing gene correction research and therapeutic development. Future directions will likely focus on overcoming cell cycle limitations and developing novel enhancers that further bias repair toward HDR pathways without compromising genomic integrity.

Homology-directed repair (HDR) has emerged as a powerful method for achieving precise genome editing, enabling researchers to insert, replace, or correct genetic sequences with unprecedented accuracy. The selection of an appropriate donor template is a critical determinant of HDR success, with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) representing the two primary formulations currently employed in research applications. While both donor types serve as templates for the cellular repair machinery following CRISPR/Cas9-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs), their structural differences impart distinct advantages and limitations across various experimental contexts. This comparative analysis examines the fundamental characteristics, performance metrics, and optimal application scenarios for ssDNA and dsDNA donors, providing evidence-based guidance for researchers designing HDR-mediated gene correction experiments.

The mechanistic differences between these donor types begin with their interaction with the DNA repair machinery. SSDNA donors typically engage in synthesis-dependent strand annealing (SDSA) pathways, while dsDNA donors may participate in more complex double-stronked break repair mechanisms. These divergent repair routes ultimately influence editing efficiency, precision, and cellular toxicity profiles. Furthermore, recent advances in donor engineering, including chemical modifications and strategic designs, have substantially enhanced the capabilities of both donor classes, expanding their utility across diverse biological systems from mammalian cells to plants.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Efficiency, Precision, and Cytotoxicity Profile

Direct comparative studies reveal significant differences in performance between ssDNA and dsDNA donors across multiple critical parameters. The table below summarizes quantitative findings from controlled experiments evaluating both donor types in mammalian cell systems.

Table 1: Performance comparison of ssDNA versus dsDNA HDR donors

| Performance Parameter | Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Donors | Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) Donors |

|---|---|---|

| Knock-in Efficiency | Similar or higher efficiency at optimal concentrations (65.4% with modified donors) [16] | High efficiency, particularly with 5' end modifications (65.4% with C6-PEG10 modification) [16] |

| Off-target Integration | Significantly reduced (near detection limit) [17] | Substantially higher off-target integration rates [17] |

| Cellular Toxicity | Lower cytotoxicity across a range of concentrations [17] | Higher cytotoxicity, especially at intermediate concentrations [17] |

| Optimal Insert Size | < 50 nucleotides (standard ssODNs) [18] / Up to 2kb with long ssDNA [19] | > 120 nucleotides [19] |

| Optimal Homology Arm Length | 30-40 nucleotides [18] | 200-300 nucleotides [19] |

| Editing Precision | Higher ratio of precise HDR [20] | Increased indel formation at junctions [16] |

Beyond these quantitative metrics, ssDNA donors demonstrate a particular advantage in sensitive applications where minimizing cellular stress is paramount. Research shows that with 0.5μg to 3μg HDR templates, ssDNA groups showed higher viable cell numbers compared to dsDNA groups, though this difference diminished at 4μg [17]. This reduced cytotoxicity profile makes ssDNA donors particularly valuable for working with sensitive primary cells, including T-cells and stem cells.

Structural and Mechanistic Considerations

The structural differences between donor types dictate their cellular processing and ultimately their performance characteristics. Single-stranded DNA donors are typically classified as oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) for shorter inserts (<100nt) or long single-stranded DNA (lssDNA) for larger genetic payloads. These linear single-stranded molecules are thought to engage directly with the resected DNA ends at the break site, serving as templates for the synthesis-dependent strand annealing pathway [18].

In contrast, double-stranded DNA donors, including PCR fragments and plasmid-derived sequences, require additional processing steps before serving as repair templates. The ends of these molecules are vulnerable to nonspecific degradation, and their double-stranded nature can activate cellular defense mechanisms, potentially contributing to the observed cytotoxicity [17]. However, strategic modifications to dsDNA donors can substantially mitigate these limitations. For instance, incorporating 5' C6-PEG10 modifications with short 50bp homology arms has enabled unprecedented KI rates of 65% for 0.7kb inserts and 40% for 2.5kb inserts in HEK293T cells [16].

Table 2: Structural properties and design considerations

| Structural Property | Single-Stranded DNA Donors | Double-Stranded DNA Donors |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Configuration | Linear or circular single-stranded [21] | Linear double-stranded [16] |

| Strand Orientation | Target strand (complementary to sgRNA) generally more effective [20] | Not applicable |

| Chemical Modifications | Phosphorothioate linkages improve stability [18] | 5' end modifications (e.g., C6-PEG10) enhance efficiency [16] |

| Advanced Formats | Circular ssDNA (cssDNA) demonstrates superior HDR frequency [21] | Biotinylated donors for Cas9-avidin tethering systems [22] |

| Homology Arm Design | Symmetric or asymmetric arms (30-90nt) [18] | Longer homology arms (200-500bp) typically required [19] |

Experimental Protocols

Workflow for HDR Using Single-Stranded DNA Donors

The following diagram illustrates the optimized experimental workflow for achieving high-efficiency homology-directed repair using single-stranded DNA donors:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ssDNA-mediated HDR

Protocol Details for ssDNA HDR

Step 1: Donor Design and Preparation

- Design ssDNA donor with 30-40 nucleotide homology arms flanking the desired modification [18]

- Incorporate phosphorothioate linkages at terminal bases to enhance nuclease resistance [18]

- Select the target strand (complementary to sgRNA) unless locus-specific data suggests otherwise [20]

- For inserts >100nt, consider long ssDNA donors with 60-90nt homology arms [23]

Step 2: Cell Preparation and Transfection

- For HEK293T and K562 cells: electroporate with 2μM Cas9 RNP complex and 50nM ssDNA donor [19]

- For primary T-cells: use optimized electroporation conditions with reduced donor concentrations to minimize toxicity [17]

- Include Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (1μM) or similar NHEJ inhibitors to favor HDR pathways [19]

Step 3: Post-transfection Processing and Analysis

- Culture cells for 48-72 hours to allow for protein expression and maturation (critical for fluorescent reporter assays) [24]

- Analyze editing efficiency via flow cytometry (for fluorescent reporters) or next-generation sequencing (for precise sequence modifications) [17]

- Screen for potential off-target integrations using targeted sequencing approaches [17]

Workflow for HDR Using Double-Stranded DNA Donors

The following diagram outlines the optimized protocol for implementing double-stranded DNA donor-mediated HDR:

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for dsDNA-mediated HDR

Protocol Details for dsDNA HDR

Step 1: Donor Design and Engineering

- Design dsDNA donors with 200-300bp homology arms for optimal efficiency [19]

- Incorporate 5' end modifications such as C6-PEG10 to enhance KI rates (5-fold increase reported) [16]

- Disrupt the PAM site or protospacer sequence in the donor template to prevent re-cleavage of edited loci [18]

- For large inserts (>2kb), verify donor integrity and concentration carefully [19]

Step 2: Transfection and Enhanced HDR

- Complex Cas9 with biotinylated donors when using Cas9-monoavidin fusions (up to 90% HDR efficiency reported) [22]

- Co-deliver with Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein or small molecule inhibitors of NHEJ (e.g., M3814) [25] [19]

- Titrate donor concentration (25-50nM) to balance efficiency against cytotoxicity [16]

Step 3: Validation and Quality Control

- Perform long-read amplicon sequencing (Oxford Nanopore) to assess HDR efficiency and precision [19]

- Evaluate integration copy number in individual clones to identify concatemerization events [16]

- Screen for random integration events at potential off-target sites [23]

Advanced Strategies and Technical Considerations

Innovative Approaches to Enhance HDR Efficiency

Recent methodological advances have substantially improved the efficiency of both ssDNA and dsDNA donor approaches. For ssDNA donors, the incorporation of HDR-boosting modules containing RAD51-preferred binding sequences has demonstrated remarkable improvements in HDR efficiency. When combined with NHEJ inhibitors or the HDRobust strategy, these modular ssDNA donors achieve up to 90.03% (median 74.81%) HDR efficiency across various genomic loci and cell types [25].

For dsDNA donors, Cas9 tethering systems represent a powerful strategy for enhancing knock-in efficiency. By fusing Cas9 with ssDNA-binding protein domains (RecA, Rad51) or short peptide motifs (FECO, WECO), researchers have created enhanced genome editors (enGagers) that demonstrate 1.5- to 6-fold higher knock-in efficiency compared to standard Cas9. This "tripartite editor with ssDNA optimized genome engineering" (TESOGENASE) system has achieved 33% CAR transgene integration in primary human T cells [24].

The circular single-stranded DNA (cssDNA) format represents another innovation, combining advantages of both conventional donor types. CSSDNA donors serve as efficient HDR templates with integration frequencies superior to linear ssDNA donors when used with Cas9 or Cas12a [21]. These circular molecules also reduce cGAS-mediated cell toxicities imparted by dsDNAs and avoid concatemerization prior to genomic insertion [24].

Application-Specific Recommendations

Cell Type-Specific Considerations

Different cell types exhibit distinct preferences for donor template configurations. In primary T cells, ssDNA donors demonstrate significantly reduced cytotoxicity while maintaining high knock-in efficiency, making them ideal for CAR-T cell engineering applications [17]. In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), modified dsDNA donors with 5' C6-PEG10 modifications have achieved KI rates of 6.6% and 19.8% respectively, substantially higher than unmodified donors [16].

Plant systems present unique challenges for HDR, with recent research in potato revealing that ssDNA donors in the target orientation outperformed other configurations, achieving HDR efficiency of 1.12% of sequencing reads in protoplasts [20]. Interestingly, HDR efficiency appeared independent of homology arm length in this system, contrasting with findings in mammalian cells.

Locus-Specific Considerations

The chromatin environment of target loci significantly influences HDR efficiency. Heterochromatin regions typically show reduced editing efficiency, but with 5' C6-PEG10 end-modification, researchers have achieved a 0.5 to 1.6-fold increase in gene KI rates at predicted heterochromatin loci, with a remarkable 19.7% KI rate at one region [16]. Safe harbor sites (AAVS1, CCR5) show more predictable integration patterns, with 5' C6-PEG10 modifications improving KI rates from 3.3% to 5.0% at AAVS1 and from 2.0% to 2.9% at CCR5 in hiPSCs [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below summarizes key commercially available reagents and their applications in HDR experiments:

Table 3: Essential research reagents for HDR experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Approach | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Templates | GenCRISPR ssDNA [17] | Long single-stranded DNA donors with high purity (>98%) and sequence verification |

| Donor Templates | Alt-R HDR Donor Blocks [19] | Chemically modified dsDNA templates with enhanced HDR efficiency and reduced off-target integration |

| Efficiency Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 [19] | Small molecule compound that inhibits NHEJ to favor HDR pathways |

| Efficiency Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein [19] | Protein-based reagent that inhibits 53BP1 to promote HDR in primary cells |

| Advanced Systems | enGager/TESOGENASE [24] | Cas9 fused with ssDNA-binding peptides to tether cssDNA donors for enhanced integration |

| Advanced Systems | HDR-boosting modules [25] | RAD51-preferred sequences incorporated into ssDNA donors to enhance HDR efficiency |

| Controls & Design | gRNA + HDR Template Design Tools [17] | Bioinformatics tools for optimizing guide RNA and donor template design |

The strategic selection between single-stranded and double-stranded DNA donors represents a critical decision point in experimental design for precise genome editing. SSDNA donors offer significant advantages in applications requiring minimal cytotoxicity, reduced off-target integration, and editing of short sequences, particularly in sensitive primary cells. In contrast, dsDNA donors, especially when chemically modified, enable efficient insertion of larger genetic payloads and can achieve remarkable knock-in efficiencies in more robust cell lines.

The emerging innovations in donor engineering—including HDR-boosting modules, Cas9 tethering systems, and circular ssDNA formats—are progressively blurring the historical limitations of both donor classes. These advances, coupled with a growing understanding of cell type-specific and locus-specific considerations, empower researchers to make increasingly informed decisions about donor selection and optimization. As the field continues to evolve, the integration of these enhanced donor systems with small molecule and protein-based HDR enhancers promises to further expand the frontiers of precise genome editing for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

The Critical Role of the Cell Cycle in HDR Efficiency

Homology-directed repair is a precise genome editing mechanism that uses a template DNA to repair double-strand breaks. However, its application in research and therapy is hampered by its low efficiency compared to error-prone repair pathways like non-homologous end joining. The cell cycle imposes a fundamental constraint on HDR, as the process occurs predominantly during the late S and G2/M phases when sister chromatids are available as natural templates [26]. This application note explores the critical influence of cell cycle regulation on HDR efficiency and provides detailed protocols for leveraging this relationship to enhance precise genome editing outcomes.

Cell Cycle Regulation of DNA Repair Pathways

The choice between DNA double-strand break repair pathways is tightly regulated across the cell cycle. While NHEJ operates throughout all phases, HDR is restricted to periods when homologous templates are accessible.

Figure 1: DNA Repair Pathway Activity Across the Cell Cycle. HDR is confined to S and G2/M phases when homologous templates are available.

This cell cycle dependence occurs because HDR requires homologous templates—normally provided by sister chromatids after DNA replication—and specific cyclin-dependent kinase activity that peaks in S and G2/M phases [26]. CDK1 and CDK2 phosphorylate key HDR factors such as CtIP and BRCA1 to initiate end resection, the critical first step that commits to HDR rather than NHEJ [27].

Cell Cycle Synchronization Strategies to Enhance HDR

Small Molecule Inhibitors for Cell Cycle Arrest

Researchers can enrich cell populations in HDR-permissive phases using small molecules that reversibly arrest the cell cycle. The table below summarizes validated compounds and their effects on HDR efficiency.

Table 1: Cell Cycle Synchronizing Compounds for HDR Enhancement

| Compound | Target/Mechanism | Cell Cycle Arrest | HDR Enhancement | Example Concentrations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nocodazole | Microtubule polymerization inhibitor | G2/M | 1.7 to 6-fold [26] | 100-200 ng/mL (HEK293T), 1 μg/mL (hPSCs) |

| ABT-751 | Sulfonamide binding β-tubulin | G2/M | 3.1-fold (hPSCs) [26] | 0.37 μg/mL |

| Docetaxel | Microtubule stabilizer | G2/M | Significant increase (multiple cell types) [28] | 0.5-5 μM |

| Irinotecan | Topoisomerase I inhibitor | G2/M | 1.2-1.5-fold (ssODN-mediated KI) [28] | 1-10 μM |

| Mitomycin C | DNA alkylating agent | G2/M | Significant increase (multiple cell types) [28] | 1-5 μM |

Cell type-specific responses significantly influence compound effectiveness. For instance, nocodazole produces a 6-fold HDR increase in HEK293T cells but only 1.7-fold enhancement in induced pluripotent stem cells [26]. Similarly, irinotecan and mitomycin C show greater efficacy in 293T cells, while docetaxel and nocodazole perform better in BHK-21 and primary pig fetal fibroblasts [28].

Combinatorial Approaches

Combining multiple cell cycle inhibitors can produce synergistic effects. Treatment with three or four small molecule combinations generally enhances KI frequency beyond individual compound applications [28]. However, researchers must carefully evaluate cell type-specific toxicity, particularly in primary cells and embryos where docetaxel and mitomycin C demonstrate pronounced toxicity despite their HDR-enhancing effects [28].

Experimental Protocols for HDR Enhancement

Cell Cycle Synchronization Protocol for HDR Enhancement

This protocol describes the use of small molecule inhibitors to synchronize the cell cycle in S and G2/M phases for improving CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR efficiency in mammalian cells.

Materials

- Cell lines: HEK293T, BHK-21, pig fetal fibroblasts, or other target cells

- Small molecule inhibitors:

- Nocodazole (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# M1404)

- Docetaxel (e.g., Selleckchem, Cat# S1148)

- Irinotecan (e.g., Selleckchem, Cat# S1198)

- Mitomycin C (e.g., Selleckchem, Cat# S8146)

- Cell culture medium: DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin

- CRISPR-Cas9 components: Cas9 protein/gRNA RNP complexes or expression plasmids

- HDR templates: dsDNA donors (circular or linear) or ssODN with appropriate homology arms

- Transfection reagents: Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX or electroporation equipment

- Flow cytometry equipment for cell cycle analysis and HDR efficiency assessment

Procedure

Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Seed cells at appropriate density (e.g., 1-2×10⁵ cells/well in 12-well plates) 24 hours before transfection.

- Transfert cells with CRISPR-Cas9 components and HDR donor templates using preferred method (lipofection or electroporation).

- For lipofection, use 1-2 μg Cas9 plasmid, 0.5-1 μg gRNA plasmid, and 1-2 μg donor DNA per well of a 12-well plate.

- For RNP electroporation, use 20-40 pmol Cas9 protein, 20-40 pmol gRNA, and 20-40 pmol donor DNA per reaction.

Small Molecule Treatment

- Prepare fresh stock solutions of small molecule inhibitors in appropriate solvents (DMSO for most compounds).

- 4-6 hours post-transfection, add small molecule inhibitors at optimized concentrations:

- Nocodazole: 0.5-2.5 μM

- Docetaxel: 1-5 μM

- Irinotecan: 1-10 μM

- Mitomycin C: 1-5 μM

- For primary cells, use lower concentration ranges to minimize toxicity.

- Incubate cells with inhibitors for 12-24 hours depending on cell type and compound.

Compound Removal and Recovery

- After treatment, carefully remove medium containing small molecules.

- Wash cells twice with PBS and add fresh complete medium.

- Culture cells for additional 48-96 hours to allow expression of edited genes.

Analysis of HDR Efficiency

- For fluorescent reporter systems, analyze cells by flow cytometry 72-96 hours post-transfection.

- For endogenous gene editing, harvest genomic DNA 72-96 hours post-transfection.

- Perform PCR amplification of target locus and assess HDR efficiency by:

- Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) if editing introduces/modifies a restriction site

- T7 endonuclease I assay for total editing efficiency

- Sanger or next-generation sequencing for precise quantification

Timing

- Day 1: Cell seeding

- Day 2: Transfection and small molecule treatment

- Day 3: Compound removal and recovery

- Day 4-5: Analysis of HDR efficiency

Optimization Notes

- Perform dose-response curves for each small molecule in new cell types to balance efficacy and toxicity.

- Consider combinatorial treatments (2-3 compounds) for enhanced effect, but carefully assess toxicity.

- Adapt treatment duration based on cell proliferation rates—shorter for fast-dividing cells, longer for slow-dividing cells.

Alternative HDR Enhancement Methods

Beyond cell cycle synchronization, several molecular approaches can further improve HDR efficiency:

- DNA template engineering: 5′-biotin or 5′-C3 spacer modifications on donor DNA can increase single-copy integration by up to 20-fold [29].

- Repair pathway modulation: RAD52 supplementation enhances ssDNA integration nearly 4-fold, though it may increase template multimerization [29].

- SSA pathway inhibition: Rad52 inhibitor D-I03 reduces asymmetric HDR and improves precise integration [8].

Molecular Mechanisms Connecting Cell Cycle and HDR

Cell cycle synchronization in S and G2/M phases induces CDK1/CCNB1 protein accumulation, which activates HDR factors to facilitate effective end resection of CRISPR-cleaved double-strand breaks [28]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that cell cycle inhibitors activate common signaling pathways that mediate crosstalk between cell cycle progression and DNA repair [28].

Figure 2: Molecular Mechanism of HDR Enhancement by Cell Cycle Synchronization. CDK activation leads to phosphorylation of HDR factors that initiate end resection.

The synchronization of cells in HDR-permissive phases creates a cellular environment favorable for precise genome editing by both increasing the proportion of cells competent for HDR and activating the necessary molecular machinery through CDK-mediated phosphorylation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Research

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Enhancement

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Inhibitors | Nocodazole, ABT-751, Docetaxel, Irinotecan | Synchronize cells in HDR-permissive phases | Concentration and toxicity are cell type-dependent |

| HDR Templates | ssODN, dsDNA with 300-1000 bp homology arms [30], TRAC-eGFP HDR template [31] | Provide repair template for precise editing | Longer homology arms generally increase HDR efficiency |

| DNA Repair Modulators | RAD52 protein, Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2, ART558 (POLQ inhibitor), D-I03 (Rad52 inhibitor) | Shift repair balance toward HDR or suppress alternative pathways | RAD52 enhances ssDNA integration but may increase multimerization [29] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | High-fidelity Cas9, Cas9 nickase, Cas12a (Cpf1) | Induce targeted DNA breaks with reduced off-target effects | Nickase systems reduce but don't eliminate structural variations [32] |

| Detection Tools | Long-read amplicon sequencing (PacBio), knock-knock computational framework [8] | Comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes | Essential for detecting large structural variations missed by short-read sequencing |

Safety Considerations and Limitations

While cell cycle synchronization significantly enhances HDR efficiency, researchers must consider potential risks:

- Genomic instability: Cells during cell cycle arrest can accumulate mutations, potentially leading to malignant transformation [26].

- Structural variations: CRISPR editing, particularly with HDR-enhancing strategies, can induce large structural variations including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [32].

- Detection limitations: Traditional short-read sequencing often misses large deletions that eliminate primer binding sites, leading to overestimation of HDR efficiency [32] [8].

Comprehensive genotoxicity assessment using long-read sequencing and structural variation detection methods (CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) is recommended, particularly for therapeutic applications [32].

Strategic manipulation of the cell cycle through small molecule inhibitors provides a powerful approach to enhance HDR efficiency in genome editing applications. The protocols and reagents detailed in this application note offer researchers practical methods to significantly improve precise genetic modifications across various cell types. However, comprehensive safety assessments and optimization for specific experimental systems remain essential for successful implementation. As CRISPR-based therapies advance toward clinical application, understanding and leveraging the connection between cell cycle regulation and DNA repair will be crucial for developing safer, more efficient genome editing strategies.

Strategic HDR Template Design: From Basic Components to Advanced Formats

Homology-directed repair (HDR) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for achieving precise genome modifications in CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing. The efficiency and precision of HDR are critically dependent on the design of the repair template, with homology arm length representing a fundamental parameter influencing editing outcomes. This application note examines current optimization strategies for homology arm design, providing structured experimental protocols and quantitative guidelines for researchers engaged in therapeutic development and precise gene correction studies. Within the competitive landscape of DNA repair pathways, where non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) predominates, optimal homology arm design becomes paramount for shifting the balance toward high-fidelity HDR outcomes [33].

Homology Arm Length: Quantitative Design Parameters

The length of homology arms flanking the desired modification significantly impacts HDR efficiency. The optimal length varies based on the type of repair template and the specific genomic context of the experiment.

Table 1: Optimal Homology Arm Lengths for Different Donor Templates

| Donor Template Type | Recommended Arm Length | Key Considerations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid Donor | 500 - 1000 base pairs (bp) [34] | Longer arms facilitate homologous recombination; requires disruption of the CRISPR target site post-integration. | Knock-in of large sequences (e.g., fluorescent reporters, entire genes) [34] |

| ssODN Donor | ~50 nucleotides (nt) per arm (symmetric) [35] | Shorter, single-stranded templates; suitable for introducing point mutations and small insertions. | Point mutation knock-ins [35] |

Recent research has revealed that the impact of other cellular factors on HDR efficiency is modulated by homology arm length. A 2025 study demonstrated that the mismatch repair protein Msh2 suppresses HDR only when homology arms are short (e.g., 1.7 kb), but does not affect HDR when longer arms are used [36] [37]. This finding highlights the critical importance of arm length selection in overcoming inherent cellular barriers to precise gene editing.

Critical Secondary Parameters in HDR Template Design

Distance Between Cut and Insertion Sites

The proximity of the Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB) to the intended modification site is a paramount factor in HDR efficiency. In mammalian cells, HDR efficiency is highest when the insertion site and the DSB are within ten nucleotides of each other, with efficiency dropping rapidly as this distance increases [34]. This limitation severely constrains the selection of effective guide RNAs (gRNAs), particularly for tagging proteins at their N- or C-termini.

To overcome this constraint, the SMART (Silently Mutate And Repair Template) design strategy has been developed. This innovative approach involves introducing silent mutations into the "gap" sequence of the repair template—the region between the Cas9 cut site and the insertion site. These mutations prevent the gap sequence from base-pairing with the target genomic DNA during repair, while maintaining the original amino acid coding [38].

Table 2: Impact of Cut-to-Insert Distance on HDR Efficiency

| Distance from Cut Site | HDR Efficiency with Traditional Template | HDR Efficiency with SMART Template | Experimental Confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 bp (Optimal) | High (Baseline) | High (Baseline) | In vitro assays with Lmnb1 and CXCR4 genes [38] |

| 10-40 bp | Exponential decrease | Substantially attenuated decrease | In vitro assays with Lmnb1 and CXCR4 genes [38] |

| 40-101 bp | Very low | ~50% of optimal efficiency | In vitro assays with Lmnb1 and CXCR4 genes [38] |

The SMART strategy effectively expands the useful range of gRNAs, allowing researchers to utilize gRNAs located farther from the desired modification site while maintaining respectable HDR efficiency [38].

Strategic Disruption of CRISPR Target Sites

A critical consideration in donor template design is preventing re-cleavage of successfully edited alleles. When the donor template contains an intact CRISPR target sequence, Cas9 can repeatedly cut the locus after HDR has occurred, undermining editing efficiency. To prevent this, the donor template should be designed to disrupt the target site through one or more of the following strategies:

- Split target sequence: Designing the insertion to split the 20-nucleotide CRISPR target sequence or the PAM site [34].

- Introduce silent mutations: Incorporating nucleotide changes in the PAM or CRISPR target region within the homology arm, preserving the amino acid sequence but preventing Cas9 recognition [34].

- PAM disruption: Specifically targeting the PAM sequence for mutation, as demonstrated in the SELECT strategy where CGG was mutated to CCG to prevent re-cleavage [39].

DNA Repair Pathway Interplay and HDR Optimization

The success of HDR-mediated editing is significantly influenced by the complex interplay between competing DNA repair pathways. Beyond the well-characterized NHEJ pathway, alternative pathways such as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) contribute to diverse repair outcomes that often compromise HDR efficiency [8] [33].

Recent studies demonstrate that inhibiting NHEJ alone is insufficient to eliminate imprecise repair outcomes. Long-read amplicon sequencing reveals that even with NHEJ inhibition, imprecise integration can account for nearly half of all editing events, with MMEJ and SSA pathways contributing significantly to these outcomes [8]. Specifically:

- MMEJ inhibition (via POLQ inhibitors like ART558) reduces large deletions (≥50 nt) and complex indels [8].

- SSA inhibition (via Rad52 inhibitors like D-I03) reduces asymmetric HDR and other imprecise integration patterns [8].

- Combined pathway suppression represents a promising strategy to further enhance precise HDR efficiency beyond NHEJ inhibition alone.

Experimental Protocol for HDR Template Design and Validation

Protocol: Optimized HDR in Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs)

This protocol outlines steps for achieving high-efficiency HDR in hPSCs using an inducible Cas9 system, based on methodology demonstrating INDEL efficiencies of 82-93% for single-gene knockouts [35].

Materials and Reagents

- Cell Line: Doxycycline-inducible spCas9-expressing hPSCs (hPSCs-iCas9) [35]

- Nucleofection System: 4D-Nucleofector with P3 Primary Cell Kit (Lonza) [35]

- sgRNA: Chemically synthesized and modified (CSM-sgRNA) with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both ends to enhance stability [35]

- Donor Template: Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs, ~100 nt) for point mutations [35]

- Cell Culture: PGM1 Medium with Matrigel-coated plates [35]

Procedure

- sgRNA Design and Preparation

Cell Preparation and Nucleofection

- Culture hPSCs-iCas9 in Pluripotency Growth Medium on Matrigel-coated plates.

- Induce Cas9 expression with doxycycline 24 hours before nucleofection.

- Dissociate cells with EDTA and pellet by centrifugation at 250 × g for 5 minutes.

- Combine sgRNA or sgRNA/ssODN mix with nucleofection buffer.

- Electroporate using 4D-Nucleofector (Program: CA137) [35].

- For multiple gene knockouts, co-electroporate with two or three sgRNAs at equal weight ratios [35].

Repeated Nucleofection

- Conduct a second nucleofection 3 days after the first nucleofection using identical parameters to enhance editing efficiency [35].

Validation and Analysis

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening for HDR Enhancers

This protocol describes a screening approach to identify chemical compounds that enhance HDR efficiency, combining LacZ colorimetric and viability assays for quantifiable readouts [40].

Materials and Reagents

- Cell Model: Human cultured cells compatible with HDR assays [40]

- Screening Platform: 96-well plate format for high-throughput capability [40]

- Detection Method: Plate reader-compatible assays [40]

- Chemical Libraries: Small molecule collections for screening [40]

Procedure

- Assay Design and Plate Preparation

- Design 96-well plates with appropriate controls for normalization.

- Implement LacZ-based HDR reporter system that produces colorimetric readout upon successful HDR.

Compound Screening

- Treat cells with chemical library compounds alongside CRISPR-Cas9 editing components.

- Incubate for appropriate duration to allow for editing and reporter expression.

Dual-Mode Detection

- Perform LacZ colorimetric assay to quantify HDR efficiency.

- Conduct viability assay in parallel to control for compound toxicity.

- Read both assays using a standard plate reader [40].

Data Analysis

- Normalize HDR efficiency values against viability controls.

- Identify hit compounds that significantly enhance HDR efficiency without excessive toxicity.

- Validate hits in secondary assays using physiological relevant models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Experiments

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for HDR Optimization

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inducible Cas9 Cell Lines | Enables controlled nuclease expression | hPSCs-iCas9 line allows tunable expression; improves efficiency and reduces toxicity [35] |

| Chemically Modified sgRNAs | Enhances RNA stability and editing efficiency | 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at 5' and 3' ends reduce degradation [35] |

| Pathway-Specific Inhibitors | Modulates DNA repair pathway competition | NHEJi (Alt-R), MMEJi (ART558), SSAi (D-I03) enhance precise editing [8] |

| RNP Complexes | Direct delivery of preassembled Cas9-gRNA | Improves editing efficiency and reduces off-target effects; enables fast editing [38] |

| Long-Read Sequencing | Comprehensive analysis of editing outcomes | PacBio amplicon sequencing with knock-knock framework reveals diverse repair patterns [8] |

| SELECT System | Counter-selection against unedited cells | Uses DNA damage-induced promoters to eliminate WT cells; achieves up to 100% editing efficiency [39] |

Optimizing homology arm length represents a fundamental aspect of HDR template design that interacts critically with other parameters including cut-to-insert distance, template design strategy, and cellular repair pathway activity. The integration of innovative approaches—such as SMART templates for flexible gRNA selection, strategic pathway inhibition, and counter-selection systems like SELECT—enables researchers to achieve unprecedented levels of precision and efficiency in genome editing. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate both basic research and therapeutic development for genetic disorders, with optimized HDR serving as a cornerstone technology for precise genetic manipulation.

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) using the CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized precise genome editing, enabling researchers to correct mutations, insert tags, and introduce specific genetic variants. A critical determinant of HDR success is the choice of donor repair template (DRT), with single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) serving as the primary workhorses. The decision between these templates is not merely one of convenience; it fundamentally influences editing efficiency, precision, and the spectrum of achievable edits. Framed within the broader context of optimizing HDR for gene correction research, this application note provides a structured comparison and detailed protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the optimal template for their specific experimental goals.

Template Comparison: ssODNs vs. dsDNA

The choice between ssODN and dsDNA donors is primarily dictated by the size of the intended genetic modification. Each template type possesses distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal use cases, which are quantitatively summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ssODN and dsDNA Donor Templates for HDR

| Feature | ssODN (ssDNA) | dsDNA |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Insert Size | Short edits (1-50 bp) [7] | Large inserts (>200 bp, up to several kb) [7] [41] |

| Typical Homology Arm Length | 30-60 nucleotides (nt) [11] [7]; can be as short as 30 nt [11] | 500-1000 bp for plasmids; can be effective with 60-200 bp for linear dsDNA [29] [7] |

| HDR Efficiency | Generally higher for point mutations and small insertions [42] [41] | Typically lower than ssODNs for precise edits; can be improved with template modifications [29] [7] |

| Cytotoxicity & Cell Viability | Lower cytotoxicity, higher cell viability post-transfection [17] | Higher cytotoxicity, particularly with linearized dsDNA [17] [41] |

| Off-Target Integration | Significantly reduced off-target integration [17] | Higher risk of random, off-target integration [17] [7] |

| Primary Drawbacks | Prone to synthesis errors; limited carrying capacity [42] [41] | High concatemer formation (multi-copy integration); lower HDR efficiency; more toxic [29] [7] |

| Ideal Application | Introducing point mutations, small indels, and short epitope tags [42] [7] | Inserting large genetic elements like fluorescent protein genes, selection cassettes, or conditional alleles [7] |

Decision Framework and Experimental Design

The following decision pathway provides a logical framework for selecting the appropriate donor template based on the experimental goal. Adhering to this workflow helps in aligning the design strategy with the desired genomic outcome.

Key Design Parameters for ssODNs

While the decision pathway provides the strategic choice, optimizing the template's design is crucial for success. For ssODNs, several parameters require careful consideration:

- Homology Arm Length: While arms as short as 30 nucleotides can facilitate HDR, optimal efficiency is often achieved with longer arms. A systematic study in zebrafish demonstrated that increasing homology arm length from 60 nt to 120 nt could lead to a tenfold improvement in HDR rates, though further extension to 180 nt provided minimal gains or even decreased efficiency [42]. A length of approximately 120 nucleotides is often most effective [41].

- Strand Orientation: The ssODN can be designed as "target" (complementary to the sgRNA-bound strand) or "non-target" (complementary to the PAM-containing strand). The optimal orientation can be locus-dependent [11] [42]. However, some studies indicate a slight preference for the "non-target" strand [42], while others found that the "target" orientation outperformed other configurations in potato protoplasts [11]. Testing both orientations is recommended for critical applications.

- 5' End Modifications: Chemical modifications of the donor DNA 5' end can substantially boost HDR efficiency. Recent research shows that modifying the 5' end with a C3 spacer (5′-propyl) can produce up to a 20-fold rise in correctly edited mice, while 5′-biotinylation increased single-copy integration up to 8 fold. These modifications are thought to enhance HDR by protecting the donor from exonuclease activity and potentially improving its recruitment to the break site [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: HDR using ssODN Donors for Point Mutations

This protocol is adapted from methods used in zebrafish and mammalian cell studies [42] [41].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex: Comprising recombinant Cas9 protein and target-specific sgRNA.

- ssODN Donor Template: HPLC-purified, with 40-120 nt homology arms and the desired mutation centrally located. Disrupt the PAM or seed sequence in the donor to prevent re-cleavage.

- Electroporation Reagent/Device: For delivery into cells (e.g., Neon, Amaxa).

- HDR Enhancers (Optional): Small molecules such as RS-1 (a RAD51 stimulator) or inhibitors of the NHEJ pathway (e.g., SCR7).

Procedure:

- Complex Formation: Co-complex 5 µg of Cas9 protein with a 1.5x molar ratio of sgRNA to form the RNP complex. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes.

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash the target cells (e.g., primary T cells, stem cells). Resuspend the cell pellet in the appropriate electroporation buffer at a concentration of 1-5 x 10^7 cells/mL.

- Electroporation Mix: Combine the following in an electroporation cuvette:

- RNP complex (from step 1)

- 1-4 µg of ssODN donor template [17]

- Cell suspension

- Electroporation: Electroporate cells using a pre-optimized program specific to your cell type.

- Recovery and Analysis: Transfer cells to pre-warmed culture medium. Optionally, add HDR-enhancing small molecules at this stage. Analyze editing efficiency after 48-72 hours via flow cytometry (for fluorescent reporters) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) for precise quantification of HDR and error-prone events [42].

Protocol 2: HDR using dsDNA Donors for Large Knock-Ins

This protocol is based on mouse zygote injection and cell culture studies, highlighting strategies to overcome the inherent challenges of dsDNA templates [29] [7].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- CRISPR-Cas9 Component: Cas9 mRNA or protein and sgRNA.

- dsDNA Donor Template: Linear dsDNA fragment (PCR-generated or synthesized) with homology arms of 200 bp or longer. For one-step cKO model generation, the donor may contain LoxP sites and selection markers.

- Modification Reagents: Enzymes for 5'-monophosphorylation or chemical reagents for 5'-biotin or C3-spacer modification.

- RAD52 Protein: For enhancing ssDNA integration when using denatured templates.

Procedure:

- Template Preparation: Generate a linear dsDNA donor fragment via PCR or synthesis. For enhanced HDR, consider the following modifications:

- Denaturation: Heat-denature the long 5′-monophosphorylated dsDNA template and rapidly cool it to create a predominantly single-stranded template. This has been shown to boost precise editing and reduce unwanted template concatemerization [29].

- 5' Modification: Incorporate a 5′-biotin or 5′-C3 spacer modification during synthesis. This significantly improves single-copy HDR integration [29].

- Microinjection/Transfection Mix Preparation: Prepare the injection mix. For a mouse zygote injection study, a typical mix included:

- Cas9 protein (50 ng/µL)

- crRNAs (25 ng/µL each)

- Denatured or modified dsDNA donor (10 ng/µL)

- Optional: RAD52 protein (1.5 µM) to increase HDR efficiency, though this may also increase template multiplication [29].

- Delivery: Inject the mixture into the pronucleus or cytoplasm of mouse zygotes. For cell culture, use transfection or electroporation to deliver the CRISPR components and the donor template.

- Embryo Transfer or Cell Culture: Transfer injected zygotes into pseudo-pregnant females. For cells, culture them for several days to allow for genome editing and expression.

- Genotyping: Screen born pups or cell clones for correct integration using a combination of PCR, Southern blotting (to distinguish single-copy from multi-copy integration), and sequencing.

Advanced Strategies and Troubleshooting

Enhancing HDR Efficiency

Even with optimal template design, HDR competes with dominant error-prone repair pathways. The following table summarizes advanced strategies to tilt this balance in favor of HDR.

Table 2: Advanced Strategies to Enhance HDR Efficiency

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Example Application & Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Template Denaturation | Converts dsDNA to ssDNA, reducing concatemer formation and improving precision. | Denaturation of a 5′-monophosphorylated dsDNA template resulted in a 4-fold increase in correctly targeted animals and a 2-fold reduction in template multiplication [29]. |

| RAD52 Supplementation | RAD52 promotes annealing and strand exchange, crucial for ssDNA integration. | Adding RAD52 to a denatured DNA template increased precise HDR from 8% to 26% in mouse embryos, though it also increased template multiplication [29]. |

| 5' End Modifications | Protects the template from exonucleases and may enhance recruitment to the DSB. | 5′-C3 spacer modification produced up to a 20-fold rise in correctly edited mice. 5′-biotin increased single-copy integration up to 8 fold [29]. |

| Small Molecule Inhibitors | Modulate DNA repair pathways (inhibit NHEJ or stimulate HDR factors). | SCR7 (Ligase IV inhibitor) and RS-1 (RAD51 stimulator) have been used to improve HDR rates in various cell types [42] [41]. |

| TFO-tailed ssODN | Uses a Triplex-forming oligonucleotide to tether the donor template to the genomic target site, improving spatial availability. | A TFO-tailed ssODN doubled the knock-in efficiency (from 18.2% to 38.3%) compared to a standard ssODN in a cellular system [43]. |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low HDR Efficiency: Ensure the DSB is highly efficient. Optimize homology arm length and try 5' end modifications. Consider synchronizing cells to S/G2 phase or using HDR-enhancing small molecules.

- High Off-Target Integration or Random Insertion: Switch from dsDNA to ssODN donors, which demonstrate significantly reduced off-target integration [17].

- Template Multimerization (Concatemer Formation): A common issue with linear dsDNA donors. Mitigate this by using denatured dsDNA templates or 5'-modified donors, which are shown to reduce head-to-tail template multiplications [29].

- Error-Prone Repair with ssODNs: ssODN-mediated repair can be error-prone, resulting in complex, partial integration of the donor template. Use high-quality, purified ssODNs and employ NGS-based analysis to thoroughly characterize edited clones and confirm the presence of error-free HDR events [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HDR Experiments

| Reagent / Solution | Function in HDR Workflow |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | The core nuclease component for generating a site-specific double-strand break. Essential for Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery. |

| Target-Specific sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the intended genomic locus. Can be synthesized individually or as a single-guide RNA (sgRNA). |

| Purified ssODN Donors | Single-stranded DNA templates for introducing point mutations and short inserts with high precision and low toxicity. |

| Linear dsDNA Donors (e.g., from IDT) | Double-stranded DNA fragments for inserting large genetic cargo, such as fluorescent markers or conditional exons. |

| RAD52 Protein | A recombination mediator protein that can be added to the injection/transfection mix to enhance the integration efficiency of ssDNA templates [29]. |

| HDR Boosting Small Molecules (e.g., RS-1) | Chemical additives that stimulate the cellular HDR machinery (e.g., by activating RAD51) to improve knock-in rates. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., SCR7) | Chemical additives that transiently inhibit the competing Non-Homologous End-Joining pathway, thereby favoring HDR. |

| 5'-Modification Kits (Biotin, C3 Spacer) | Chemical reagents used to modify the 5' ends of donor DNA templates, protecting them from exonucleases and improving HDR efficiency [29]. |

Precise gene editing, central to both biological research and clinical gene therapy, relies on the cell's innate DNA repair mechanisms. When a CRISPR-Cas system induces a site-specific double-strand break (DSB), the cell primarily engages one of two major pathways for repair: the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or the high-fidelity homology-directed repair (HDR) [7] [44]. The HDR pathway can utilize an exogenously provided donor DNA template to incorporate precise genetic modifications, ranging from single-nucleotide changes to large insertions. However, a significant bottleneck persists because NHEJ is the dominant and more efficient repair pathway in most contexts, often resulting in a low frequency of desired precise edits amidst a high background of random insertions and deletions (indels) [41] [44]. Consequently, innovative strategies to enhance HDR efficiency are critical for advancing the field.