Optimizing m6A-Related lncRNA Prognostic Models: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing ROC Curve Performance

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and bioinformaticians aiming to develop and optimize prognostic models based on m6A-related long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs).

Optimizing m6A-Related lncRNA Prognostic Models: A Comprehensive Guide to Enhancing ROC Curve Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and bioinformaticians aiming to develop and optimize prognostic models based on m6A-related long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). It covers the entire pipeline from foundational biology and data acquisition to advanced model construction, performance troubleshooting, and rigorous validation. Focusing specifically on enhancing the predictive accuracy as measured by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, the guide synthesizes current methodologies, including LASSO Cox regression and deep learning approaches, and emphasizes the critical link between model performance and clinical applicability in cancer prognosis and therapeutic response prediction.

Laying the Groundwork: Understanding m6A-lncRNA Biology and Data Acquisition for Robust Model Development

The Critical Role of m6A Modifications in Regulating lncRNA Function in Cancer

FAQ: m6A-lncRNA Model Troubleshooting

Q1: My prognostic risk model based on m6A-related lncRNAs shows poor performance in ROC curve analysis. What could be wrong?

- Insufficient lncRNA Selection Rigor: The initial identification of m6A-related lncRNAs may have used weak correlation thresholds. Ensure you use |Pearson R| > 0.4 and p < 0.01 as a minimum standard, with some studies recommending |R| > 0.5 for stronger associations [1] [2] [3].

- Inadequate Validation Cohort: The model may be overfitted. Always split your dataset into training and testing cohorts (typically 70:30 ratio) and validate findings in both sets [1] [3].

- Suboptimal Cut-off Selection: For dichotomizing continuous risk scores, use the Maximum Absolute Youden Index (MAYI) method rather than maximally selected chi-square statistics, as it provides more meaningful p-values and better performance with RNA-seq data distributions [4].

Q2: How can I experimentally validate that an lncRNA is genuinely regulated by m6A modification?

- Knockdown Approach: Genetically inhibit key m6A writers (e.g., METTL3, RBM15) or erasers (e.g., FTO, ALKBH5) in your cancer cell lines. A true m6A-regulated lncRNA should show significant expression changes upon perturbation of these regulators [5] [2].

- m6A-Specific RIP-qPCR: Perform RNA immunoprecipitation using anti-m6A antibodies followed by quantitative PCR targeting your specific lncRNA. This directly confirms m6A modification presence [6].

- Stability Assays: Compare lncRNA half-life after transcriptional inhibition (using Actinomycin D) in control versus m6A regulator-knockdown cells. m6A modification often affects RNA stability [6].

Q3: My m6A-lncRNA risk model performs well in training data but fails in clinical specimen validation. What might explain this discrepancy?

- Sample Preservation Issues: Improper RNA preservation can degrade lncRNAs and affect m6A modification patterns. Ensure immediate freezing of clinical samples at -80°C and use appropriate RNA stabilization reagents [7].

- Tumor Heterogeneity: Bulk tissue analysis may mask important subpopulations. Consider laser-capture microdissection or single-cell approaches to ensure you're analyzing pure tumor cell populations [7] [8].

- Normalization Problems: Use multiple reference genes (not just 18S RNA) for qRT-PCR normalization, and validate their stability in your specific sample types [7].

Q4: How can I improve the clinical relevance of my m6A-lncRNA signature?

- Incorporate Clinical Parameters: Integrate your molecular signature with established clinical factors (TNM stage, grade) using nomograms to enhance predictive power [1] [2].

- Validate in Multiple Cancer Types: Test your signature across different cancer types to determine if it has pan-cancer utility or is tissue-specific [7] [1] [5].

- Assess Immune Microenvironment Correlations: Evaluate whether your m6A-lncRNA signature correlates with immune cell infiltration patterns, as this significantly impacts clinical outcomes and therapy response [7] [8] [3].

Experimental Protocols for m6A-lncRNA Research

Protocol: Constructing an m6A-lncRNA Prognostic Model

Table 1: Key Steps in m6A-lncRNA Prognostic Model Development

| Step | Procedure | Tools/Packages | Key Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Acquisition | Download RNA-seq data and clinical information | TCGAbiolinks R package | HTSeq-FPKM or TPM values [7] [1] | ||

| 2. Identify m6A-related lncRNAs | Calculate correlation between lncRNAs and m6A regulators | Pearson correlation | R | > 0.4, p < 0.01 [1] [2] | |

| 3. Initial Screening | Univariate Cox regression | survival R package | p < 0.05 for significance [7] [2] | ||

| 4. Model Construction | LASSO Cox regression | glmnet R package | 10-fold cross-validation [1] [3] | ||

| 5. Risk Score Calculation | Apply formula: Σ(Coefi × Expressioni) | Custom R script | Median risk score as cutoff [1] [2] [3] | ||

| 6. Model Validation | ROC analysis, survival curves | timeROC, survminer R packages | AUC > 0.7 acceptable [7] [1] |

Protocol: Experimental Validation of m6A-modified lncRNAs

Cell Culture and Transfection

- Culture relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., Caki-1/OS-RC-2 for renal cancer [1], bladder cancer lines [5])

- Transfect with siRNAs targeting m6A regulators (METTL3, RBM15, FTO, etc.) using appropriate transfection reagents

- Include appropriate negative controls (scrambled siRNA)

Functional Assays

- CCK-8/EdU Assays: Seed 2-3×10^3 cells/well in 96-well plates after transfection. Measure proliferation at 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours [1]

- Transwell Migration/Invasion: Seed 5×10^4 cells in serum-free medium in upper chamber. Count migrated cells after 24-48 hours [1] [5]

- Colony Formation: Seed 500-1000 cells/well in 6-well plates, culture for 10-14 days, stain with crystal violet, and count colonies [5] [6]

Molecular Validation

- RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR: Use Trizol method for RNA extraction, reverse transcribe with PrimeScript kit, perform qPCR with SYBR Green [7]

- m6A Immunoprecipitation: Fragment RNA to 100-500 nt, incubate with anti-m6A antibody, pull down with protein A/G beads, and detect target lncRNA by qRT-PCR [6]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for m6A-lncRNA Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Validation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| m6A Writers | METTL3, METTL14, RBM15 | Catalyze m6A modification; knockdown validates m6A dependence | siRNA/shRNA knockdown; assess lncRNA expression changes [5] [2] |

| m6A Erasers | FTO, ALKBH5 | Remove m6A modifications; inhibition stabilizes m6A-modified lncRNAs | Pharmacological inhibitors or genetic knockout [9] [2] |

| m6A Readers | HNRNPC, YTHDF1-3, IGF2BP1-3 | Recognize/bind m6A-modified RNAs; affect stability and function | RIP-qPCR to confirm binding to specific lncRNAs [9] [6] |

| Detection Reagents | Anti-m6A antibodies | Identify m6A modification sites via MeRIP/CLIP | Use positive control RNAs with known m6A sites [6] |

| Cell Function Assays | CCK-8, EdU, Transwell | Assess proliferation, migration after lncRNA manipulation | Include appropriate controls and multiple time points [1] [2] |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

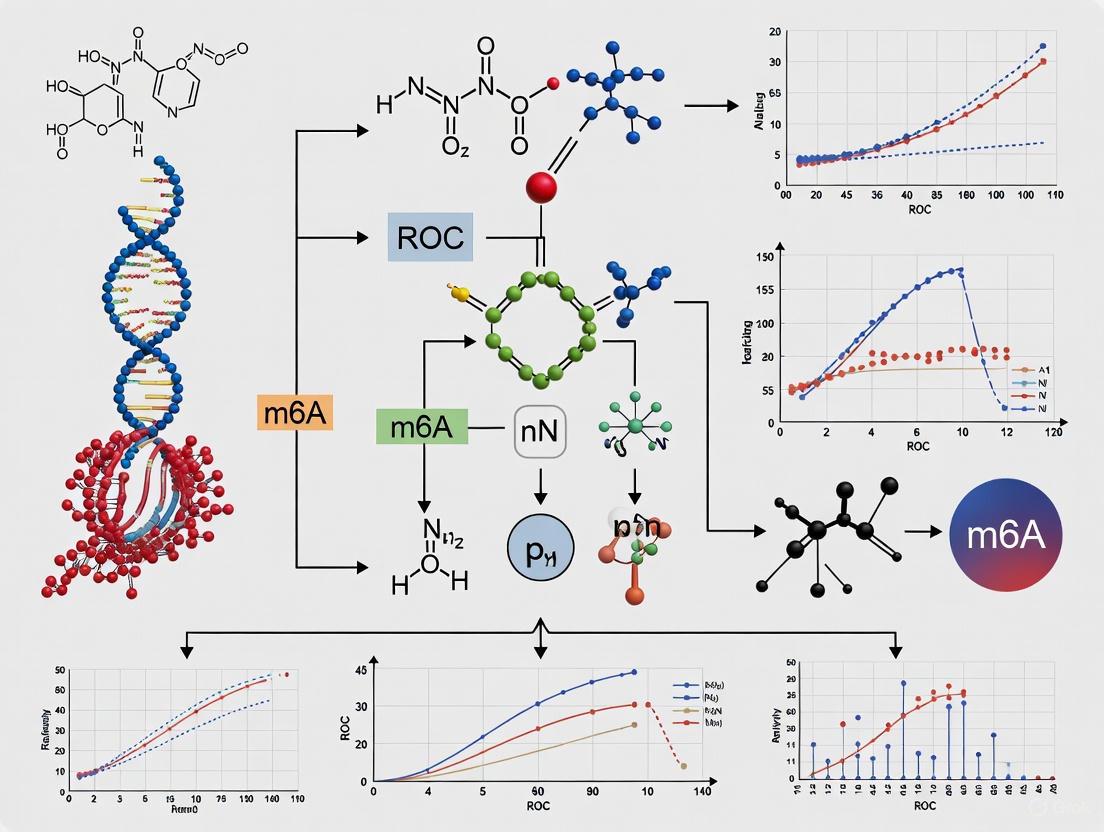

Visual Guide 1: m6A Regulation of lncRNA in Cancer. This diagram illustrates how m6A machinery components (writers, erasers, readers) collectively influence lncRNA stability and function, ultimately driving cancer phenotypes through multiple cellular pathways.

Visual Guide 2: m6A-lncRNA Research Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps in developing and validating m6A-lncRNA models, from bioinformatics analysis to experimental validation, with associated computational tools for each step.

For researchers investigating the complex relationships between m6A modifications and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in cancer biology, access to high-quality transcriptomic data is paramount. The ability to construct robust prognostic models and generate reliable ROC curve analyses depends fundamentally on properly sourced and processed data. This guide provides essential technical support for navigating major data repositories, with a specific focus on applications in m6A-lncRNA research, to enhance model performance and analytical rigor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What types of data in TCGA are most relevant for building m6A-lncRNA prognostic models? TCGA provides comprehensive multi-omics data ideally suited for m6A-lncRNA research. For prognostic model development, you will primarily need:

- Transcriptomic data: RNA-Seq data for identifying lncRNA expression profiles [10] [11]

- Clinical data: Overall survival, disease stage, and treatment response information for survival analysis [10] [12]

- Molecular characterization data: Including mutation and methylation data for integrative analysis [13] Recent studies have successfully utilized these TCGA data types to construct m6A-related lncRNA signatures for various cancers including colorectal, bladder, and esophageal cancer [10] [5] [11].

Q2: What is the difference between TCGA harmonized data and legacy data? TCGA data exists in two main forms with important distinctions:

- Harmonized data: Processed using standardized pipelines, aligned to GRCh38, and available through the GDC portal [13] [14]

- Legacy data: The original data generated by TCGA sequencing centers, available through Broad's Firehose or cBioPortal [13] For new analyses, the harmonized data is recommended as it ensures consistency across different cancer types through uniform processing protocols [13].

Q3: How can I handle the computational challenges of processing large TCGA datasets? Working with TCGA data requires substantial computational resources. Consider these approaches:

- NIH Biowulf HPC cluster: Recommended for large-scale analyses, memory-intensive tasks, and when working with millions of sequences [13]

- GDC Data Transfer Tool: Essential for efficiently downloading large numbers of files or datasets exceeding 5GB [13]

- Pre-processed datasets: Resources like MLOmics provide TCGA data that is already processed for machine learning applications, which can significantly reduce preprocessing burdens [14].

Q4: What are common pitfalls in lncRNA identification from TCGA data and how can I avoid them? Accurate lncRNA identification requires careful computational handling:

- Use updated annotations: Cross-reference gene IDs with Ensembl Genome Browser (GRCh38.p13) from GENCODE to properly distinguish lncRNAs from mRNAs [10]

- Apply correlation filters: Identify m6A-related lncRNAs using Pearson correlation thresholds (e.g., |R| > 0.3, p < 0.001) with known m6A regulators [10] [12]

- Account for dynamic nature: Remember that lncRNA localization and function can be cell-type specific and influenced by experimental conditions [15]

Q5: Are there alternative resources if I need TCGA data pre-processed for machine learning? Yes, several resources offer pre-processed TCGA data:

- MLOmics: Provides 8,314 patient samples across 32 cancer types with four omics types, featuring multiple processed versions (Original, Aligned, Top) suitable for machine learning [14]

- cBioPortal: Offers user-friendly access to TCGA data with visualization tools [13]

- LinkedOmics: Contains multi-omics data with additional analysis capabilities [14]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Difficulty Accessing Controlled Data

Problem: Some TCGA data requires dbGaP authorization, creating access barriers.

Solution:

- Determine access level: Identify whether your required data is open-access or controlled [13]

- Obtain authorization: For controlled data (e.g., germline variants, primary sequence BAM files), complete the dbGaP authorization process through eRA Commons [13]

- Use alternative resources: For preliminary analysis, consider using MLOmics or cBioPortal which may provide derived datasets without access restrictions [14]

Issue: Inconsistent Gene Nomenclature and Annotation

Problem: Discrepancies in gene naming conventions across platforms affect lncRNA identification.

Solution:

- Standardize identifiers: Use unified gene IDs to resolve naming variations caused by different sequencing methods or reference standards [14]

- Leverage annotation resources: Cross-reference with Ensembl Genome Browser 99 (GRCh38.p13) from GENCODE [10]

- Apply consistent filters: Implement a standardized pipeline for all samples, as demonstrated in recent m6A-lncRNA studies [10] [12]

Issue: Technical Variation Affecting Model Performance

Problem: Batch effects and technical artifacts compromise model robustness and ROC analysis.

Solution:

- Utilize harmonized data: Access data through GDC which has been processed using standardized pipelines [13]

- Implement normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods (e.g., z-score, log transformation) as used in MLOmics processing pipelines [14]

- Select significant features: Use ANOVA-based feature selection to filter out noisy genes, retaining only those with significant variance across samples [14]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for m6A-lncRNA Research

| Resource/Tool | Function | Application in m6A-lncRNA Research |

|---|---|---|

| GDC Data Portal | Primary access point for TCGA data | Download harmonized transcriptomic and clinical data [13] |

| Ensembl Genome Browser | Gene annotation reference | Properly identify and classify lncRNAs vs. mRNAs [10] |

| MLOmics | Pre-processed TCGA for ML | Access cancer multi-omics data ready for prognostic modeling [14] |

| GDC Data Transfer Tool | Bulk data download | Efficiently transfer large genomic datasets [13] |

| R/Bioconductor Packages | Data analysis and visualization | Perform differential expression, survival analysis, and ROC curve generation [10] [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Downloading TCGA Data via GDC Portal

This protocol outlines the systematic process for acquiring TCGA data appropriate for m6A-lncRNA prognostic model development.

Materials:

- GDC Data Portal access (portal.gdc.cancer.gov)

- GDC Data Transfer Tool (for large datasets)

- Computational resources (local or HPC cluster)

Procedure:

- Navigate to GDC: Access the GDC Data Portal at https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ [13]

- Select cohort: Use "Cohort Builder" or "Projects" tab to select your cancer type of interest (e.g., TCGA-BRCA for breast cancer) [13]

- Apply filters: Refine your cohort using clinical or molecular filters (e.g., gender, tumor stage) as needed for your research question [13]

- Access repository: Navigate to "Repository" to filter files by data type (e.g., RNA-Seq, gene quantification files) [13]

- Review file metadata: Examine file properties, associated cases, and processing methods for each file of interest [13]

- Download data: For datasets <5GB and <10,000 files, use direct download; for larger datasets, use the GDC Data Transfer Tool with the manifest file [13]

- Download associated data: Ensure you obtain clinical data (TSV/JSON), biospecimen information, and sample sheets for complete analysis [13]

Protocol: Identifying m6A-Related lncRNAs from Transcriptomic Data

This methodology is adapted from multiple recent studies that successfully constructed m6A-lncRNA prognostic models [10] [11] [12].

Materials:

- TCGA transcriptome data (RNA-Seq)

- List of m6A regulators (writers, readers, erasers)

- Computational environment (R statistical software)

- R packages: limma, glmnet, survival

Procedure:

- Data preparation:

lncRNA identification:

- Cross-reference gene IDs with Ensembl Genome Browser to distinguish lncRNAs from mRNAs [10]

- Apply quality control filters to remove low-expression transcripts

Co-expression analysis:

Prognostic model construction:

- Conduct univariate Cox regression to identify m6A-related lncRNAs with prognostic significance [10] [12]

- Apply LASSO-Cox regression to refine the lncRNA signature and prevent overfitting [10] [11]

- Calculate risk scores using the formula:

riskScore = Σ(Coefficient(gene_i) * mRNA Expression(gene_i))[12]

Model validation:

Key Considerations for Enhancing Model Performance

When working with TCGA data for m6A-lncRNA prognostic models, several factors significantly impact ROC curve analysis and overall model performance:

- Data Quality: Prioritize harmonized data over legacy data to minimize technical artifacts [13] [14]

- Feature Selection: Implement rigorous feature selection methods (e.g., ANOVA-based) to reduce dimensionality and focus on biologically relevant lncRNAs [14]

- Validation Strategy: Always validate findings in independent datasets when possible, and perform comprehensive survival and ROC analyses [10] [12]

- Multi-omics Integration: Consider incorporating additional data types (methylation, mutation) to enhance model predictive power [14]

By following these guidelines and leveraging the resources outlined, researchers can effectively source high-quality transcriptomic data to build robust m6A-lncRNA prognostic models with improved performance metrics.

Core m6A Regulators: A Reference Table

The machinery governing N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification is categorized into three functional classes: writers (methyltransferases), erasers (demethylases), and readers (binding proteins). The table below summarizes the key components and their primary functions.

Table 1: Core m6A Regulatory Proteins and Their Functions

| Regulator Class | Component Name | Primary Function | Key Characteristics | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | METTL3 | Catalytic subunit of methyltransferase complex [16] [17] | Installs m6A modification; essential for embryonic development [16] | Nucleus [17] |

| METTL14 | RNA-binding scaffold in methyltransferase complex [16] [17] | Enhances METTL3 catalytic activity; lacks independent catalytic function [16] | Nucleus [17] | |

| WTAP | Regulatory subunit [16] [18] | Directs complex to nuclear speckles and mRNA targets [17] [18] | Nucleus [17] | |

| KIAA1429 (VIRMA) | Scaffold protein for methyltransferase complex [16] [19] | Guides region-selective m6A methylation, particularly in 3'UTR [16] [19] | Nucleus | |

| Erasers | FTO | Demethylase [19] [18] | Removes m6A; preferentially demethylates m6Am [18] | Nucleus [18] |

| ALKBH5 | Demethylase [19] [18] | Major m6A demethylase; influences tumor immune microenvironment [19] | Nucleus [18] | |

| Readers | YTHDF1 | Binds m6A-modified RNA [17] [18] | Promotes translation efficiency [17] [18] | Cytoplasm [18] |

| YTHDF2 | Binds m6A-modified RNA [17] [18] | Promotes mRNA decay and regulates stability [17] [18] | Cytoplasm [18] | |

| YTHDC1 | Binds m6A-modified RNA [17] [18] | Regulates alternative splicing [17] [18] | Nucleus [18] | |

| IGF2BP1/2/3 | Binds m6A-modified RNA [19] [18] | Enhances mRNA stability and storage [19] [18] | Cytoplasm [18] |

The m6A Regulatory Network

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationships between the core m6A regulators and their impact on RNA metabolism.

Diagram Title: m6A Regulator Network and Functional Outcomes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My m6A-related lncRNA risk model has a low Area Under the Curve (AUC) value in ROC analysis. What could be the cause? A low AUC value suggests limited diagnostic ability of your model [20]. An AUC of 0.5 indicates performance equivalent to random chance, while values below 0.8 are considered to have limited clinical utility [20]. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Insufficient Feature Selection: The initial set of m6A-related lncRNAs may not be prognostic enough. Re-evaluate your univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses with stricter significance thresholds (e.g., P < 0.01) to identify the most robust lncRNA signatures [10] [21].

- Overfitting: Using too many lncRNAs in your signature relative to your sample size can lead to a model that performs poorly on new data. Employ regularization techniques like LASSO Cox regression, which helps penalize model complexity and select the most relevant features [10].

- Lack of Validation: Always validate your model's performance in an independent patient cohort. This confirms that the model generalizes and is not tailored to the specific quirks of your initial dataset [10].

Q2: How do I interpret the AUC value from my model's ROC curve? The AUC value is a key metric for evaluating the diagnostic performance of your model [20] [22]. It represents the probability that your model will rank a randomly chosen positive instance (e.g., a patient with poor outcome) higher than a randomly chosen negative instance (e.g., a patient with good outcome) [22]. The following table provides a standard interpretation guide:

Table 2: Interpreting Area Under the Curve (AUC) Values

| AUC Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0.9 ≤ AUC | Excellent discrimination |

| 0.8 ≤ AUC < 0.9 | Considerable/good discrimination |

| 0.7 ≤ AUC < 0.8 | Fair discrimination |

| 0.6 ≤ AUC < 0.7 | Poor discrimination |

| 0.5 ≤ AUC < 0.6 | Fail (no better than chance) |

Adapted from [20]

Q3: I've identified a candidate m6A-related lncRNA. How can I experimentally validate its functional role and effect on the tumor immune microenvironment?

- Functional Validation (In Vitro): Perform knockdown or overexpression of the lncRNA in relevant cancer cell lines (e.g., A549 for lung adenocarcinoma) [21]. Assess subsequent changes in:

- Proliferation, invasion, and migration: Using assays like CCK-8, transwell, and wound healing.

- Apoptosis and drug resistance: Using flow cytometry and IC50 measurements for chemotherapeutics like cisplatin [21].

- Immune Microenvironment Analysis (In Silico/Bioinformatics): Leverage transcriptomic data to analyze correlations between your lncRNA signature and:

- Immune Cell Infiltration: Use tools like CIBERSORT to estimate abundances of member cell populations (e.g., T cells, macrophages) [10] [21].

- Immune Checkpoint Expression: Evaluate the expression levels of key immune checkpoints like PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 between high-risk and low-risk patient groups defined by your model [10]. Studies have shown that high-risk groups can exhibit significantly higher checkpoint expression, suggesting potential for immunotherapy response prediction [10].

Q4: How can I improve the stability and reliability of my siRNA for knocking down lncRNAs in functional experiments?

- Use Chemically Modified siRNA: Chemically modified siRNA duplexes (e.g., Stealth RNAi) offer increased stability in serum, which is crucial for both in vitro and in vivo experiments [23].

- Optimize Transfection Conditions: Run a transfection reagent-only control to assess cellular sensitivity. Systematically test different cell densities and siRNA concentrations (e.g., between 5 nM and 100 nM) to find optimal conditions that minimize toxicity and maximize knockdown efficiency [23].

- Include Proper Controls: Always use a validated positive control siRNA (e.g., targeting GAPDH) to confirm transfection efficiency and a negative control siRNA to account for non-specific effects [23].

Experimental Protocols for m6A-Related lncRNA Model Development

Protocol 1: Constructing an m6A-Related lncRNA Prognostic Signature

This protocol is adapted from established methodologies used in cancer research [10] [21].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain transcriptomic RNA-seq data (e.g., FPKM values) and corresponding clinical information (especially overall survival data) from a public database such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA).

- Identify m6A Regulators and lncRNAs: Extract a known set of m6A regulator genes (writers, erasers, readers; approximately 19-23 genes) from literature [10] [21]. Use an annotation file (e.g., from GENCODE) to distinguish and extract lncRNAs from the transcriptomic data.

- Define m6A-Related lncRNAs (mRLs): Perform co-expression analysis between the expression of m6A regulators and all lncRNAs. Identify mRLs using a correlation threshold (e.g., |Pearson R| > 0.3) and a significance threshold (e.g., P < 0.001) [10].

- Screen Prognostic mRLs: Conduct univariate Cox regression analysis on the mRLs to identify those significantly associated with patient overall survival (OS). A common threshold is P < 0.01 [10].

- Model Construction with LASSO Cox Regression: To prevent overfitting, subject the significant prognostic mRLs from step 4 to Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression. This will further refine the lncRNA list and calculate a coefficient for each. The final risk score for each patient is calculated using the formula:

Risk Score = Σ (Expression of mRLn * Coefficient of mRLn) - Patient Stratification: Divide patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score or an optimal cut-off value determined from the data.

- Model Validation:

- Kaplan-Meier Analysis: Plot survival curves for the high and low-risk groups and assess significance with a log-rank test.

- ROC Analysis: Evaluate the model's predictive accuracy by plotting time-dependent Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival [10].

Protocol 2: Assessing Association with Tumor Immune Microenvironment

- Immune Cell Infiltration Estimation: For each tumor sample in your cohort, use a computational tool like CIBERSORT in conjunction with the LM22 signature matrix to estimate the relative fractions of 22 human immune cell types [21].

- Immune Checkpoint Analysis: Extract the expression data for key immune checkpoint genes (e.g., PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4) from your transcriptomic dataset.

- Correlation with Risk Score: Compare the immune cell infiltration scores and immune checkpoint expression levels between the high-risk and low-risk groups defined by your m6A-lncRNA signature. Use statistical tests like the Wilcoxon test to determine significance [10]. This can reveal whether your model is associated with an immunosuppressive or immunoreactive microenvironment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for m6A and lncRNA Research

| Reagent / Tool Type | Specific Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Antibodies | Anti-METTL3, Anti-FTO, Anti-YTHDF2 [18] | Protein detection via Western Blot (WB), Immunohistochemistry (IHP), or Immunoprecipitation (IP) to validate regulator expression. |

| siRNA / RNAi Tools | Stealth RNAi, In Vivo siRNA [23] | Chemically modified duplexes for potent and stable knockdown of target lncRNAs or m6A regulators in vitro and in vivo. |

| In Vivo Transfection Reagent | Invivofectamine 3.0 [23] | Lipid-based reagent for systemic delivery of siRNA molecules in animal models. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CIBERSORT [10] [21] | Deconvolutes transcriptomic data to infer immune cell infiltration levels in tumor samples. |

| Sequencing Kits | MeRIP-seq / miCLIP Kits [18] | High-resolution mapping of m6A modifications across the transcriptome. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How do I initially identify m6A-related lncRNAs from transcriptomic data?

Q: What is the standard methodological workflow for the initial identification of m6A-related long non-coding RNAs?

A: The initial identification involves a multi-step bioinformatic screening process using transcriptomic data, typically from sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). The core of this method is a correlation analysis between the expression levels of known m6A regulators and all detected lncRNAs [24] [25].

- Step 1: Data Acquisition and Preparation. Obtain RNA sequencing data that includes both normal and diseased tissues (e.g., tumor samples). Annotate the transcripts to distinguish lncRNAs from mRNAs [26] [25].

- Step 2: Define m6A Regulator Gene Set. Compile a list of known writers, erasers, and readers. Studies often use a set of 23-29 well-established m6A genes, such as METTL3, METTL14, FTO, ALKBH5, YTHDF1/2/3, and IGF2BP1/2/3 [24] [25].

- Step 3: Perform Correlation Analysis. Calculate the correlation coefficient (e.g., Pearson or Spearman) between the expression of each m6A regulator and each lncRNA across all samples [24] [25].

- Step 4: Set a Significance Threshold. Apply thresholds to identify statistically significant and biologically relevant associations. A common threshold is an absolute correlation coefficient > 0.4 with a p-value < 0.001 [25]. LncRNAs passing this filter are considered "m6A-related."

Troubleshooting Tip: Low Number of Significant lncRNAs

- Problem: The analysis yields very few m6A-related lncRNAs.

- Solution: Consider using a less stringent correlation coefficient threshold (e.g., >0.3) or adjusting the p-value cutoff. Ensure your dataset has a sufficient sample size, as statistical power is highly dependent on the number of observations [27].

FAQ: How can I improve the performance of a prognostic model based on m6A-related lncRNAs?

Q: What strategies can be employed to enhance the predictive accuracy and robustness of an m6A-lncRNA risk model, as reflected in the ROC curve analysis?

A: Improving model performance involves careful feature selection, validation, and integration of clinical variables.

- Strategy 1: Employ Advanced Feature Selection. Use the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) Cox regression analysis on your initial list of m6A-related lncRNAs. This technique penalizes the model for having too many features, helping to select the most prognostic lncRNAs and prevent overfitting [28] [24] [25]. This step is crucial for building a robust model with a high Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC).

- Strategy 2: Construct a Multi-lncRNA Signature. A model combining multiple m6A-related lncRNAs (a "risk signature") consistently shows better predictive performance than single lncRNA markers [24] [25]. The risk score is calculated using the formula:

Risk score = Σ(Coef_i * Exp_i), whereCoef_iis the regression coefficient from the LASSO analysis, andExp_iis the expression level of each lncRNA [25]. - Strategy 3: Build a Integrated Nomogram. Combine the m6A-lncRNA risk score with established clinical factors like pathologic stage to create a nomogram. This integrated approach has been shown to enhance prognostic prediction accuracy for 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival, as confirmed by calibration plots [25].

Troubleshooting Tip: Poor Validation in an Independent Cohort

- Problem: Your model performs well in the training dataset but poorly in the testing dataset.

- Solution: This indicates overfitting. Revisit the LASSO regression parameters and ensure 10-fold cross-validation was used during the model building phase. Also, verify that the training and testing datasets are from the same source and processed identically [25].

FAQ: How do I move from a list of lncRNAs to understanding their functional role?

Q: After identifying key m6A-related lncRNAs, what experimental and bioinformatic methods are used to decipher their biological function and regulatory mechanisms?

A: Functional characterization typically involves constructing regulatory networks and validating specific molecular interactions.

- Method 1: Construct a Competing Endogenous RNA (ceRNA) Network. This is a common mechanism of action for lncRNAs. The workflow is:

- Predict microRNAs (miRNAs) that bind to your key m6A-related lncRNAs using tools like TargetScan and miRanda [28] [29].

- Identify the target mRNAs of these miRNAs.

- Construct a visual network (e.g., using Cytoscape) comprising the lncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs [28]. This network hypothesizes a functional pathway where the lncRNA "sponges" miRNA to regulate mRNA expression.

- Method 2: Functional Enrichment Analysis. Use the list of genes (mRNAs) from your ceRNA network or genes co-expressed with your m6A-related lncRNA to perform Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. This reveals enriched biological processes and signaling pathways (e.g., MAPK signaling, PPAR signaling), providing insight into the lncRNA's potential role in disease [29] [26] [25].

- Method 3: Experimental Validation of the m6A Modification.

- methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-Seq/qPCR): This is the gold standard for confirming m6A modification on a specific lncRNA. It uses an anti-m6A antibody to immunoprecipitate methylated RNA fragments, which are then sequenced or quantified via qPCR [29] [30] [31].

- Functional Assays: Perform in vitro or in vivo experiments (e.g., cell proliferation, migration, colony formation assays) after knocking down or overexpressing the lncRNA to observe phenotypic changes [6].

Troubleshooting Tip: ceRNA Network is Too Large and Unwieldy

- Problem: The predicted ceRNA network contains hundreds of molecules, making it difficult to interpret.

- Solution: Increase the stringency of your prediction parameters (e.g., context++ score in TargetScan, energy threshold in miRanda). Focus the subsequent analysis on the top-ranked interactions or only include molecules that are differentially expressed in your dataset [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential reagents and tools used in the featured methodologies.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-m6A Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of m6A-modified RNA fragments in MeRIP-Seq/qPCR experiments. | Rabbit polyclonal antibody (Synaptic Systems, 202003) used to pull down methylated LncRNAs [29]. |

| m6A Regulator Gene Set | A pre-defined list of writer, eraser, and reader genes for correlation analysis. | A set of 23 genes (e.g., METTL3/14, FTO, ALKBH5, YTHDF1-3, IGF2BPs) used to find correlated lncRNAs [25]. |

| TCGA/CEO Datasets | Publicly available transcriptomic and clinical data for bioinformatic discovery and validation. | SKCM and COAD data from TCGA used to identify prognostic m6A-related lncRNA signatures [28] [24] [25]. |

| LASSO Cox Regression | A statistical method for selecting the most relevant prognostic genes and building a predictive model. | Used to narrow down dozens of m6A-related lncRNAs to a final prognostic signature of 12 lncRNAs [25]. |

| Cytoscape Software | An open-source platform for visualizing complex molecular interaction networks. | Used to construct and visualize the lncRNA-m6A regulator-mRNA co-expression network [26]. |

Experimental Workflow & Network Diagrams

Diagram 1: m6A-lncRNA Identification Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core bioinformatic pipeline for identifying and modeling m6A-related lncRNAs.

Diagram 2: m6A-lncRNA Regulatory Network

This diagram visualizes the core regulatory network involving m6A-modified lncRNAs, showing how different players interact.

Integrating Clinical Phenotype Data for Meaningful Outcome Association

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my disulfidptosis-related LncRNA risk model have high AUC but fails to stratify patient survival in Kaplan-Meier analysis?

This discrepancy often arises from incorrect risk score cut-off selection or violation of the proportional hazards assumption. Use the survminer R package to determine the optimal risk score cut-point using the "maxstat" method. If survival curves cross, restrict your analysis to time periods before the crossover and re-run the log-rank test [8].

Q2: How can I improve ROC curve analysis when my sample size is limited?

With smaller sample sizes, nonparametric ROC curves may appear jagged and yield biased AUC estimates. Consider using the parametric method if your data meets normality assumptions, or apply 10-fold cross-validation to obtain more reliable performance metrics. The pROC R package can smooth curves and calculate confidence intervals for AUC [32].

Q3: What is the minimum correlation coefficient threshold for identifying disulfidptosis-related LncRNAs?

Research indicates that setting a Pearson correlation coefficient threshold of |R| > 0.4 with a significance of p < 0.001 effectively filters for biologically relevant LncRNAs while reducing false positives. Validate co-expression patterns using RT-qPCR on at least 7 patient-matched tissue samples [33] [34].

Q4: How do I handle missing clinical phenotype data when building integrated models?

Implement multiple phenotype capture methods: collect structured data via HPO terms, unstructured clinical notes, and automated NLP extraction from EHRs. The PhenoTips platform facilitates structured phenotype entry, while manual curation of clinic notes remains the most reliable method for WGS analysis [35].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting m6A LncRNA Model Performance Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor model generalizability | Overfitting on training data | Apply LASSO-Cox regression with 10-fold cross-validation; use λ_1se for higher penalty [33] [8] |

| Low AUC in validation cohort | Batch effects between datasets | Normalize RNA-seq data using TPM transformation; apply ComBat batch correction [8] |

| Inconsistent immune infiltration results | Different deconvolution algorithms | Compare CIBERSORT, ESTIMATE, and ssGSEA results; use consistent method across analyses [33] |

| Weak clinical correlation | Inadequate phenotype annotation | Implement multi-source phenotyping: HPO terms, EHR extraction, and specialist notes [35] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Disulfidptosis-Related LncRNA Prognostic Signature

Purpose: Develop and validate a multi-LncRNA signature for outcome prediction in cancer patients [33] [34].

Materials:

- RNA-seq data from TCGA (cancer samples) and GTEx (normal controls)

- Clinical follow-up data (overall survival, disease-free survival)

- R packages:

limma,survival,glmnet,timeROC

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Download transcriptomic data and clinical information from TCGA (e.g., TCGA-AML, TCGA-SKCM)

- Normalize count data to TPM or FPKM and apply log2 transformation

- Merge with clinical variables: age, stage, treatment history, survival status

Identify Disulfidptosis-Related LncRNAs

- Compile established disulfidptosis-related genes (DRGs: FLNA, FLNB, MYH9, MYH10, NDUFA11, NDUFS1, NUBPL, SLC7A11, TLN1)

- Calculate Pearson correlation between all LncRNAs and DRGs

- Filter for |R| > 0.4 and p < 0.001

- Visualize relationships using Sankey diagrams (

ggalluvialpackage)

Prognostic Model Construction

- Perform univariate Cox regression to identify survival-associated DRLs (p < 0.05)

- Apply LASSO-Cox regression with 10-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting

Calculate risk score using the formula:

Risk Score = Σ(coefficientlncRNA × expressionlncRNA)Stratify patients into high/low-risk groups using median risk score

Model Validation

- Assess predictive performance with time-dependent ROC curves (1-, 3-, 5-year)

- Validate in independent datasets using the same risk score calculation

- Perform multivariate Cox regression adjusting for clinical covariates

Protocol 2: Integrated Single-Cell Analysis of Disulfidptosis Microenvironment

Purpose: Characterize disulfidptosis-related gene expression at single-cell resolution and intercellular communication [34].

Materials:

- Single-cell RNA-seq data (e.g., GSE135337 for BLCA)

- R packages:

Seurat,CellChat,singleR - Computational resources: 16GB+ RAM, multi-core processor

Procedure:

- Quality Control and Cell Filtering

- Filter cells with >500 and <2500 expressed genes

- Exclude cells with >5% mitochondrial content

- Normalize data using

NormalizeDatafunction - Identify 3000 highly variable genes for downstream analysis

Cell Clustering and Annotation

- Perform PCA and select top 20 principal components

- Cluster cells using

FindClustersfunction (resolution = 0.5) - Annotate cell types using

singleRwith manual refinement via known markers - Visualize with UMAP/t-SNE plotting

Disulfidptosis Module Scoring

- Calculate disulfidptosis scores using

AddModuleScorefunction - Compare scores across cell types and conditions

- Identify cell populations with elevated disulfidptosis activity

- Calculate disulfidptosis scores using

Cell-Cell Communication Analysis

- Input annotated single-cell data to

CellChatpackage - Identify significantly enriched ligand-receptor pairs

- Visualize communication networks and key signaling pathways

- Input annotated single-cell data to

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Prognostic Model Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Clinical Phenotype Integration Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for m6A LncRNA Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA Datasets | Data Resource | Provides RNA-seq and clinical data for model training | TCGA-AML, TCGA-SKCM [33] [8] |

| GTEx Normal Controls | Data Resource | Normal tissue expression baseline for differential analysis | GTEx Portal [33] |

| GEO Series | Data Resource | Validation datasets and single-cell RNA-seq data | GSE135337, GSE8401, GSE15605 [8] [34] |

| Disulfidptosis-Related Genes | Gene Set | Core genes for LncRNA correlation analysis | FLNA, SLC7A11, MYH9, etc. [33] [34] |

| Human Phenotype Ontology | Annotation System | Standardized phenotype capture and analysis | HPO Database [35] |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | Computational Tool | Immune cell infiltration quantification | CIBERSORT Web Portal [33] |

| CellChat Package | Computational Tool | Cell-cell communication analysis from scRNA-seq | R/Bioconductor [34] |

| glmnet Package | Computational Tool | LASSO-Cox regression implementation | R CRAN [33] [8] |

Building the Signature: From Feature Selection to Model Construction and ROC Evaluation

In the field of cancer research, particularly in studies focusing on m6A-related lncRNAs, building robust prognostic models is crucial for advancing personalized medicine. The performance of these models heavily depends on effective feature selection techniques that identify the most biologically relevant biomarkers from high-dimensional genomic data. Univariate Cox regression and LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression represent two powerful approaches for this purpose, serving as critical steps in the pipeline to improve model performance and ROC curve analysis. This technical support guide addresses common challenges researchers encounter when implementing these techniques in their experiments.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is feature selection necessary before building an m6A-lncRNA prognostic model?

Answer: Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step in high-dimensional genomic studies where the number of features (genes, lncRNAs) far exceeds the number of observations (patients). This "n << p" problem makes standard regression models prone to overfitting, where models perform well on training data but generalize poorly to new datasets [36]. Proper feature selection:

- Reduces model complexity and enhances generalizability

- Identifies truly informative m6A-related lncRNAs from thousands of candidates

- Improves computational efficiency

- Enhances biological interpretability of the final model

In m6A-lncRNA research, studies typically begin with thousands of lncRNA candidates, which must be refined to a manageable signature (often 6-11 key markers) using rigorous statistical methods [10] [37] [38].

FAQ 2: When should I choose Univariate Cox versus LASSO Cox regression for feature selection?

Answer: These methods serve complementary purposes in the feature selection pipeline:

Univariate Cox Regression:

- Purpose: Initial filtering of features based on individual prognostic strength

- When to use: First-step screening to reduce feature space

- Advantages: Computationally efficient, easy to interpret

- Limitations: Ignores interactions between features

LASSO Cox Regression:

- Purpose: Multivariate feature selection that accounts for correlations between features

- When to use: After univariate analysis to build the final prognostic signature

- Advantages: Handles multicollinearity, produces sparse models

- Limitations: More computationally intensive

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods in Survival Analysis

| Method | Implementation | Key Characteristics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Cox | Separate Cox model for each feature | Uses Wald test statistic; filters features by p-value (typically <0.05) | Initial screening of thousands of lncRNAs |

| LASSO Cox | Penalized multivariate Cox regression | Applies L1 penalty; shrinks coefficients of irrelevant features to zero | Building final prognostic signature from pre-filtered features |

| Multivariate Cox | Standard Cox regression with multiple features | No built-in feature selection; requires pre-selected features | Validating final feature set |

FAQ 3: How do I implement Univariate Cox regression for initial lncRNA screening?

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Format data as (Ti, δi, xi) where Ti is observed time, δi is censoring indicator, and xi is the lncRNA expression vector [36]

- Normalize lncRNA expression values (e.g., log transformation, standardization)

- Ensure sufficient events (deaths) per variable (EPV ≥ 10-15)

Statistical Implementation:

- Extract hazard ratios, confidence intervals, and p-values for each lncRNA

- Apply multiple testing correction (Bonferroni or FDR) to account for false discoveries

- Select lncRNAs with p-value < 0.05 (or more stringent threshold) for further analysis

Validation:

- Check proportional hazards assumption for selected lncRNAs

- Ensure clinical relevance of selected features

FAQ 4: What are the key parameters and implementation steps for LASSO Cox regression?

Experimental Protocol:

Data Preparation:

- Use lncRNAs pre-filtered by univariate analysis (p < 0.05)

- Ensure no missing data in the selected feature set

- Create training (70-80%) and validation (20-30%) sets

LASSO Implementation:

Parameter Optimization:

- Use k-fold cross-validation (typically 5- or 10-fold) to select optimal λ (lambda)

- Choose λ that minimizes partial likelihood deviance (λ.min) or most regularized model within 1 standard error (λ.1se)

- Ensure stability of selected features through bootstrap validation

FAQ 5: How can I troubleshoot poor ROC performance after feature selection?

Troubleshooting Guide:

Table 2: Common ROC Performance Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low AUC (<0.7) | Weak prognostic features; over-aggressive feature selection; small sample size | Check univariate HRs; verify sample size adequacy; examine validation performance | Increase sample size; relax univariate p-value threshold; incorporate clinical variables |

| Overfitting (training AUC >> test AUC) | Too many features relative to samples; inadequate regularization | Compare training vs. validation performance; use nested cross-validation | Strengthen LASSO penalty (use λ.1se); implement repeated cross-validation; reduce feature set |

| Unstable feature selection | High correlation between lncRNAs; small sample effects | Check correlation matrix; bootstrap feature selection stability | Use elastic net (alpha = 0.5-0.9); pre-filter highly correlated features; increase sample size |

Additional Solutions:

- Implement nested cross-validation for unbiased performance estimation [36]

- Combine multiple feature selection methods (e.g., random forest + LASSO)

- Validate findings in independent external datasets when possible

- Consider alternative metrics like precision-recall curves for imbalanced data [39] [40]

FAQ 6: What validation steps are essential after feature selection?

Answer: Comprehensive validation is crucial for ensuring model reliability:

Internal Validation:

- Bootstrap validation (200-500 replicates)

- Calculate optimism-corrected performance metrics

- Time-dependent ROC analysis at clinically relevant timepoints [36]

Clinical Validation:

Biological Validation:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for m6A-lncRNA Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA Database | Source of lncRNA expression and clinical data | Obtain RNA-seq data and survival information for various cancers [10] [37] |

| CIBERSORT/xCell/ESTIMATE | Immune cell infiltration analysis | Characterize tumor immune microenvironment in risk groups [10] [38] |

| qRT-PCR Reagents | Experimental validation of lncRNA expression | Verify expression of signature lncRNAs in clinical samples [37] [38] |

| R Survival Package | Implementation of Cox regression models | Perform univariate and multivariate survival analysis [36] |

| glmnet Package | LASSO and elastic net regularization | Implement penalized Cox regression for feature selection [36] |

Workflow Visualization

Feature Selection Workflow for m6A-lncRNA Signature Development

ROC Curve Analysis and AUC Interpretation

This guide provides technical support for constructing and validating a risk score formula, specifically within the context of building prognostic models for m6A-related lncRNA research. A well-constructed risk score is a numerical value that reflects the severity or likelihood of a specific outcome, such as disease progression or patient survival [41]. In cancer research, these models help stratify patients into risk groups, enabling personalized treatment strategies [10] [21].

The following sections offer a detailed, step-by-step methodology and troubleshooting guide to help you build a robust model and correctly perform the essential ROC curve analysis to evaluate its performance.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Acquisition and Definition of m6A-Related lncRNAs

The first step involves gathering the necessary genomic and clinical data.

- Data Source: Obtain RNA-sequencing data and corresponding clinical information (e.g., overall survival time and status) from public repositories like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). For a typical analysis, you might work with a dataset comprising hundreds of patient samples (e.g., 611 CRC and 51 normal specimens, or 526 LUAD patients) [10] [21].

- Data Processing: Use an annotation database, such as the Ensembl Genome Browser, to distinguish lncRNAs from mRNAs in your dataset [10].

- Identify m6A-Related lncRNAs (mRLs):

- Compile a list of known m6A regulatory genes ("writers" like METTL3/14, "readers" like YTHDF1/2/3, and "erasers" like FTO and ALKBH5) [10] [21].

- Perform a co-expression analysis between the expression profiles of these m6A regulators and all lncRNAs in your dataset.

- Identify m6A-related lncRNAs (mRLs) by applying a correlation threshold (e.g., |Pearson R| > 0.3 and a statistical significance of p < 0.001) [10].

Step 2: Construction of the Risk Score Formula

The core of the model is a formula that combines the expression levels of key prognostic mRLs.

- Identify Prognostic mRLs: Perform univariate Cox regression analysis on the mRLs to identify those significantly associated with patient overall survival (OS) [10] [21].

- Build the Multivariate Model: Input the significant mRLs from the univariate analysis into a multivariate Cox regression analysis. This determines the independent contribution of each lncRNA to survival.

- Develop the Risk Formula: The risk score for each patient is calculated using the following formula [21]:

Risk Score = Σ(Coefficient<sub>lncRNA1</sub> × Expression<sub>lncRNA1</sub>) + (Coefficient<sub>lncRNA2</sub> × Expression<sub>lncRNA2</sub>) + ... + (Coefficient<sub>lncRNAn</sub> × Expression<sub>lncRNAn</sub>)- Coefficient: Derived from the multivariate Cox regression, it represents the weight or contribution of each lncRNA to the risk.

- Expression: The normalized expression level of each lncRNA in a patient's sample.

The workflow below summarizes the key stages of model development and validation.

Step 3: Model Validation via ROC Curve Analysis

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) are fundamental for assessing your model's discriminative ability [42].

- The ROC Curve is a plot of the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate (1 - Specificity) across all possible risk score cut-off points [42].

- The AUC quantifies the overall ability of the risk score to distinguish between two outcome groups (e.g., short-term vs. long-term survivors). An AUC of 0.5 indicates no discriminative power (like random chance), while an AUC of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination [43] [42].

Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: My ROC curve is in the lower right half, and the AUC is less than 0.5. What went wrong?

- Problem: A realistic diagnostic test should have an AUC of at least 0.5. An AUC significantly below 0.5 indicates the test's accuracy is worse than random guessing [44].

- Solution: This error almost always results from an incorrect "test direction" setting in your statistical software. When setting up the ROC analysis, you must correctly specify whether a larger or a smaller risk score indicates a higher likelihood of the event (e.g., patient death). If you get an AUC < 0.5, reverse this setting [44].

FAQ 2: The ROC curves for my two models intersect. Can I just compare the full AUCs?

- Problem: Simply comparing the full Area Under the Curve (AUC) is only valid when one ROC curve is consistently above the other. If the curves cross, the full AUC can be misleading because one test might be better in a specific region (e.g., high-sensitivity range) while the other is better elsewhere [44].

- Solution:

- Use the partial AUC (pAUC) to compare the areas under specific, clinically relevant regions of the curves (e.g., where False Positive Rates are between 0 and 0.1, if high specificity is crucial for your context) [43] [44].

- Supplement your analysis with other metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall (sensitivity) to provide a comprehensive assessment of model performance [44].

FAQ 3: I have two models with similar AUCs. How do I determine if one is statistically better?

- Problem: A visual inspection or simple comparison of AUC values is not sufficient to claim a statistically significant difference between two models.

- Solution: You must perform a formal statistical test for comparing ROC curves.

FAQ 4: My ROC curve has only one cut-off point and two straight lines. Is this normal?

- Problem: This "single cut-off" ROC shape typically appears when the input variable for the ROC analysis is binary, not continuous [44].

- Solution: Ensure you are using the continuous risk score to generate the ROC curve, not a previously dichotomized version (e.g., a binary high/low risk label). The ROC curve is designed to evaluate a continuous or multi-class variable across all its potential thresholds [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents, tools, and datasets for constructing an m6A-lncRNA risk model.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| TCGA Database | Primary source for RNA-seq data and clinical information (e.g., survival, stage) for various cancers [10] [21]. |

| Ensembl Genome Browser | Used to annotate and differentiate lncRNAs from mRNAs in the transcriptomic data [10]. |

| m6A Regulator List | A curated list of known "writer," "reader," and "eraser" genes (e.g., METTL3, FTO, YTHDF1) to identify m6A-related lncRNAs [10]. |

| Cox Regression Model | A statistical method to identify factors (lncRNAs) associated with survival time and to calculate their coefficients for the risk formula [10]. |

| CIBERSORT Tool | An algorithm used to estimate the abundance of specific immune cell types in a tissue sample based on gene expression data, allowing for analysis of immune infiltration [10] [21]. |

| R packages: 'survival', 'pROC', 'rms' | Essential software tools for performing survival analyses, ROC curve analysis, and constructing nomograms [10] [21]. |

Data Presentation and Interpretation

Table 2: Key metrics for evaluating the performance of a prognostic risk model.

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in m6A-lncRNA Model Context |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Score | A numerical value calculated from the risk formula. | Used to rank patients; a higher score indicates a poorer predicted prognosis [10]. |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | The ratio of the hazard rates between two groups (e.g., High vs. Low Risk). | An HR > 1 for the high-risk group indicates a higher risk of death over time [21]. |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | The probability that the model ranks a random positive case higher than a random negative case. | Measures the model's ability to discriminate between patients with good and poor outcomes. An AUC of 0.75 means a 75% chance of correct ranking [42]. |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | True Positive Rate: Proportion of actual positives correctly identified. | In a prognostic model, it is the ability to correctly identify patients who will have a poor outcome [42] [44]. |

| Specificity | True Negative Rate: Proportion of actual negatives correctly identified. | The model's ability to correctly identify patients who will have a good outcome [42] [44]. |

| p-value (Cox Model) | The statistical significance of a variable's association with survival. | A p < 0.05 for a lncRNA suggests it is a significant prognostic factor [10]. |

The Role of Nomograms in Integrating Risk Scores with Clinical Variables

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a nomogram over a simple risk score? A nomogram integrates multiple types of information—including risk scores from molecular signatures (like m6A-lncRNA models) and traditional clinical variables—into a single, easy-to-use visual tool. This allows for individualized risk prediction and superior clinical utility compared to using any single predictor alone [45] [46] [47]. For example, a nomogram for predicting intracranial infection combined a risk score based on six predictors (including pneumonia and procalcitonin levels) into a model with an AUC of 0.91 [45].

Q2: My m6A-lncRNA risk model has a good AUC. Why should I build a nomogram? While a high AUC indicates strong discriminative ability, it does not necessarily translate into clinical utility. A nomogram quantifies the individual patient's risk, helping clinicians answer the critical question: "What is the specific probability of an event for this patient?" Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) often demonstrates that a nomogram provides a greater net clinical benefit across a wide range of risk thresholds than the risk score or clinical variables alone [45] [46].

Q3: What are the essential components I need to build a nomogram for my m6A-lncRNA model? You will need three key components:

- A validated m6A-lncRNA risk signature with a calculated risk score for each patient [10] [21].

- Clinically relevant variables that are independently prognostic, such as age, disease stage, or other laboratory findings [46] [47].

- A multivariate regression model (typically Cox or logistic) that identifies the independent predictors and their coefficients, which form the foundation of the nomogram [45] [21].

Q4: How do I validate that my nomogram is robust? A robust validation process includes:

- Internal Validation: Using bootstrapping (e.g., 1000 resamples) to calculate a bias-corrected C-index and generate calibration plots [46].

- External Validation: Testing the nomogram's performance (discrimination and calibration) on a separate, independent patient cohort from a different institution [45] [47].

- Clinical Validation: Employing Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) to evaluate whether using the nomogram for clinical decisions provides a net benefit over alternative strategies [45] [46].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Calibration of the Nomogram

Problem: The calibration curve shows that the predicted probabilities from your nomogram systematically deviate from the observed outcomes (e.g., predictions are consistently too high or too low).

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting | Check if the number of events is too low relative to the number of predictors included. | Use regularization techniques (like LASSO regression) during variable selection to prevent overfitting. Perform internal validation with bootstrapping to assess optimism [10]. |

| Spectrum Bias | Verify if the validation cohort has a different case-mix (e.g., different disease stages) than the training cohort. | Recalibrate the nomogram for the new population or ensure the model is validated in a cohort that reflects the target population [45]. |

| Incorrect Model Assumptions | Test the linearity assumption for continuous variables. | Transform non-linear variables (e.g., using splines) before including them in the model [45]. |

Issue 2: Suboptimal Discriminatory Performance (Low C-index/AUC)

Problem: The nomogram's ability to distinguish between patients with and without the event is weak.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Predictors | Check the effect sizes (Hazard Ratios/Odds Ratios) of the included variables. | Re-evaluate the variable selection process. Consider incorporating more powerful molecular markers or novel clinical biomarkers [48] [5]. |

| Redundant Variables | Check for high correlation (multicollinearity) between the m6A-lncRNA risk score and other clinical variables. | Remove one of the highly correlated variables or combine them into a composite score to improve model stability [10]. |

| Data Quality | Audit the source data for the m6A-lncRNA signature and clinical variables. | Ensure accurate quantification of lncRNA expression and consistent measurement of clinical variables across patients [48]. |

Issue 3: ROC Curve Analysis Errors

Problem: Common pitfalls when evaluating the nomogram or its components using ROC analysis.

| Error Type | How to Identify | Prevention & Correction |

|---|---|---|

| AUC < 0.5 | The ROC curve descends below the diagonal. | This usually indicates an incorrect "test direction" in the statistical software. Specify whether a larger or smaller test result indicates a more positive test [44]. |

| Intersecting ROC Curves | The ROC curves of two models cross. | Do not rely solely on the full AUC. Compare partial AUC (pAUC) in a clinically relevant FPR range (e.g., high-sensitivity region for screening). Use DeLong's test for statistical comparison [44]. |

| Single Cut-off ROC Curve | The ROC curve is V-shaped with only one inflection point. | This occurs if a continuous variable (like a risk score) was incorrectly treated as a binary variable. Ensure the original continuous values are used for ROC analysis [44]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Developing and Validating an m6A-lncRNA Risk Signature

This protocol outlines the foundational step for obtaining the molecular risk score to be integrated into a nomogram [10] [21] [5].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain RNA-seq data and corresponding clinical information (especially overall survival or other relevant endpoints) from a public database like TCGA.

- Identify m6A-related lncRNAs (mRLs):

- Compile a list of known m6A regulators (Writers: METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, etc.; Erasers: FTO, ALKBH5; Readers: YTHDF1-3, etc.).

- Construct a co-expression network between the expression of these regulators and all lncRNAs.

- Define mRLs using a correlation threshold (e.g., |Pearson R| > 0.3 and p < 0.001).

- Build a Prognostic Signature:

- Perform univariate Cox regression analysis to identify mRLs significantly associated with survival.

- Use LASSO-Cox regression to penalize coefficients and select the most robust lncRNAs for the final signature to avoid overfitting.

- Calculate the risk score for each patient using the formula:

Risk Score = Σ (Coefficient<sub>lncRNAi</sub> × Expression<sub>lncRNAi</sub>)

- Validate the Signature: Stratify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score. Validate the prognostic power using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and time-dependent ROC curves in both training and validation cohorts.

Protocol 2: Constructing and Validating the Integrated Nomogram

This protocol details the process of combining the m6A-lncRNA risk score with clinical variables [45] [46] [47].

- Data Preparation: Merge the m6A-lncRNA risk scores with curated clinical data for each patient.

- Univariate and Multivariate Analysis:

- Perform univariate logistic (for binary outcomes) or Cox (for time-to-event outcomes) regression analysis on all candidate variables, including the risk score and clinical factors.

- Enter significant variables from the univariate analysis into a multivariate regression model to identify independent predictors.

- Nomogram Construction: Using the

rmspackage in R (or similar), construct the nomogram based on the final multivariate model. Each predictor is assigned a points scale, and the total points correspond to a predicted probability of the clinical event. - Performance Assessment:

- Discrimination: Calculate the Harrell's C-index and plot the ROC curve to assess the model's ability to distinguish between outcomes.

- Calibration: Plot calibration curves (predicted probability vs. observed frequency); a 45-degree line indicates perfect calibration.

- Clinical Utility: Perform Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) to evaluate the net benefit of using the nomogram for clinical decision-making across different probability thresholds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application in m6A-lncRNA Research |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA Database | A public repository of cancer genomics data, providing RNA-seq and clinical data. | Sourcing transcriptomic data and clinical information to identify and validate m6A-related lncRNA signatures [10] [21]. |

| LASSO-Cox Regression | A statistical method that performs variable selection and regularization to enhance prediction accuracy. | Shrinking coefficients of non-essential lncRNAs to build a parsimonious and prognostic risk signature [10] [5]. |

| CIBERSORT Algorithm | A computational tool for estimating immune cell infiltration from bulk tissue gene expression data. | Characterizing the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) in high-risk vs. low-risk groups defined by the m6A-lncRNA signature [10] [21]. |

| SHAPE/DMS Probing | Experimental techniques for determining RNA secondary structure at nucleotide resolution. | Investigating the structure-function relationship of prognostic lncRNAs, as their function is often dictated by structure [48] [49]. |

| METTL3/RBM15 siRNA | Small interfering RNA to knock down the expression of specific m6A "writer" genes. | Functionally validating the role of m6A regulators in controlling the expression and modification of prognostic lncRNAs [5]. |

Workflow Diagram: From Data to Clinical Nomogram

The diagram below visualizes the logical workflow for developing a nomogram that integrates an m6A-lncRNA risk score with clinical variables.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on ROC Curve Analysis

FAQ 1: What does the Area Under the Curve (AUC) value actually tell me about my model's performance?

The AUC, or Area Under the ROC Curve, is a single scalar value that summarizes the overall ability of your diagnostic test or binary classification model to discriminate between two classes (e.g., high-risk vs. low-risk patients) [50]. It is equivalent to the probability that a randomly chosen positive instance will be ranked higher than a randomly chosen negative instance [22]. The following table interprets the range of AUC values:

Table 1: Interpretation of AUC Values for Model Performance

| AUC Value Range | Interpretation of Discriminatory Power |

|---|---|

| 0.9 - 1.0 | Outstanding |

| 0.8 - 0.9 | Excellent |

| 0.7 - 0.8 | Acceptable |

| 0.5 - 0.7 | Poor |

| 0.5 | No discrimination (equivalent to random guessing) |

FAQ 2: How do I interpret an ROC curve for a time-to-event outcome, like overall survival at 1, 3, and 5 years?

For survival analysis, a separate ROC curve can be constructed for each pre-specified time point (e.g., 1, 3, and 5 years) [51] [52]. This is known as time-dependent ROC analysis. The resulting AUC at each time point (AUC(t)) tells you how well your model's risk score (e.g., from an m6A-lncRNA signature) can distinguish between patients who experienced an event (like death) by time t and those who did not. Comparing the AUCs across time points helps you understand if your model's predictive performance is consistent over the entire follow-up period or if it diminishes for long-term predictions.

FAQ 3: My model's AUC is less than 0.5. What does this mean and how can I fix it?

An AUC significantly less than 0.5 is incorrect for a realistic diagnostic test and indicates that your model's predictions are worse than random guessing [44]. This error most commonly arises from an incorrect "test direction" selected in the statistical software. For example, if a higher risk score is associated with a higher likelihood of being in the positive group (e.g., poor survival), you must select 'larger test result indicates more positive test'. Conversely, if a lower score indicates a positive outcome, you should select 'smaller test result indicates more positive test' [44]. Correcting this setting will typically resolve the issue.

FAQ 4: Two of my compared models have similar AUCs, but their ROC curves cross. Which one is better?

Simply comparing the total AUC values can be misleading when ROC curves intersect [44]. In such cases, the models may perform differently in specific regions of the curve that are critical for your application. Instead of relying on the total AUC, you should:

- Calculate the partial AUC (pAUC) for the range of False Positive Rates (FPRs) that are clinically relevant for your study [44].

- Compare other metrics like accuracy, precision, and recall at the operational threshold you plan to use [44].

- Use statistical tests like the DeLong test (for correlated ROC curves from the same subjects) to determine if the difference in AUCs is statistically significant [44].

FAQ 5: How do I choose the optimal cut-off value from my ROC curve for clinical stratification?

The point on the ROC curve that is farthest from the diagonal line of no-discrimination (the top-left corner) often represents the best balance between sensitivity and specificity [22] [50]. A common method to find this point is to maximize Youden's J statistic (J = Sensitivity + Specificity - 1) [22]. However, the "optimal" threshold ultimately depends on the clinical context. If missing a positive case (e.g., a high-risk patient) is very costly, you might choose a threshold that favors higher sensitivity, even if it means a lower specificity.

Troubleshooting Common ROC Analysis Errors

Table 2: Common ROC Curve Errors and Solutions

| Error | Description | Prevention & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Error 1: AUC < 0.5 [44] | The ROC curve falls significantly below the diagonal, indicating performance worse than random guessing. | Check and correctly set the "test direction" in your statistical software (e.g., SPSS, R) to define what constitutes a "positive" test result [44]. |

| Error 2: Intersecting ROC Curves [44] | Two ROC curves from different models cross each other, making a simple AUC comparison insufficient. | Do not rely solely on total AUC. Use partial AUC (pAUC) for clinically relevant FPR regions and compare secondary metrics like precision and recall [44]. |

| Error 3: Ignoring Statistical Comparison [44] | Concluding one model is better than another based on a trivial difference in AUC values without statistical testing. | For models tested on the same subjects, use the DeLong test. For independent sample sets, use methods like the Dorfman and Alf method [44]. |

| Error 4: Single Cut-off ROC Curve [44] | The ROC curve is not smooth but appears as a single inflection point with two straight lines, providing no information on other thresholds. | This happens when the test variable is incorrectly treated as binary. Ensure you use the original continuous variable (e.g., the raw risk score) to plot the ROC curve, not a pre-determined binary classification [44]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating an m6A-Related lncRNA Prognostic Signature with Time-Dependent ROC Analysis

The following workflow outlines the key steps for developing and validating a prognostic model, as used in studies on colorectal and pancreatic cancer [10] [51] [52].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Obtain RNA-Sequencing (RNA-seq) data and corresponding clinical survival data (overall survival or progression-free survival) from public databases like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Use data in FPKM or count formats [51] [52].

- Annotate the transcriptome using a reference like GENCODE to differentiate between mRNAs and lncRNAs [51] [52].

Identification of m6A-Related lncRNAs:

- Compile a list of known m6A regulators (writers, readers, erasers) from literature [10] [51].

- Perform co-expression analysis between the expression of these m6A regulators and all lncRNAs in the dataset. Identify m6A-related lncRNAs (mRLs) using a Pearson correlation threshold (e.g., |R| > 0.4) and a significance level (e.g., p < 0.001) [51] [52].

Construction of the Prognostic Signature:

- Univariate Cox Regression: Identify mRLs significantly associated with patient survival (p < 0.05) [10] [52].

- LASSO Cox Regression: Apply the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) method with tenfold cross-validation to the significant mRLs from the previous step. This penalizes the coefficients of less important variables, reducing overfitting and selecting the most parsimonious set of lncRNAs for the model [10] [52].

- Multivariate Cox Regression: Perform a multivariate Cox regression on the lncRNAs selected by LASSO to establish the final model and calculate the regression coefficients (β) for each lncRNA [52].

- Calculate Risk Score: For each patient, compute a risk score using the formula:

Risk Score = (β1 * Exp1) + (β2 * Exp2) + ... + (βn * Expn)where β is the coefficient from the multivariate Cox model and Exp is the expression value of the corresponding lncRNA [52].

Model Validation using ROC Analysis:

- Stratify patients into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median risk score from the training cohort (e.g., TCGA) [51] [52].

- Use Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test to visualize and assess the survival difference between the two groups.

- Perform time-dependent ROC curve analysis to evaluate the model's predictive accuracy at 1, 3, and 5 years. Calculate the AUC for each time point [51] [52]. The model's performance is considered robust if the AUC values are consistently above 0.7 across these time points.

- Validate the model's performance in an independent external cohort (e.g., from ICGC or a GEO dataset) using the same risk score formula and cut-off value [52].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for m6A-lncRNA Model Development

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| TCGA & ICGC Databases | Public repositories providing standardized cancer genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data. | Source for training (TCGA) and independent validation (ICGC) of the prognostic signature [51] [52]. |

| GENCODE Annotation | A high-quality reference gene annotation. | Used to differentiate mRNA from lncRNA in the transcriptome data [51] [52]. |

| R Statistical Software | A programming language and environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Platform for performing all statistical analyses, including Cox regression, LASSO, and ROC curve generation [10] [51]. |

R package: glmnet |

Implements LASSO regression models. | Used for performing LASSO Cox regression to select the most relevant lncRNAs [10] [51]. |

R package: survivalROC |