Optimizing Molecular Descriptor Selection with RFE and 1D-CNN: A Guide for Enhanced QSAR and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) to optimize molecular descriptor selection.

Optimizing Molecular Descriptor Selection with RFE and 1D-CNN: A Guide for Enhanced QSAR and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on integrating Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) to optimize molecular descriptor selection. It covers the foundational principles of RFE as a wrapper-style feature selection algorithm and 1D-CNN for sequence-based molecular feature extraction. The content details a practical methodology for implementation using libraries like scikit-learn, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges such as computational cost and overfitting, and validates the approach through performance comparisons with other feature selection techniques. By presenting a robust framework for building more interpretable, efficient, and accurate Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models, this guide aims to accelerate the preclinical drug discovery pipeline.

The Essential Guide to RFE and 1D-CNN in Modern Cheminformatics

The Critical Challenge of High-Dimensional Molecular Data in Drug Discovery

The process of drug discovery is inherently hampered by the curse of dimensionality. Modern techniques generate molecular datasets characterized by a vast number of features (high-dimensional space) relative to the number of observations. This complexity arises from the need to encode intricate structural, electronic, and physicochemical properties of molecules into numerical descriptors for computational analysis. The presence of redundant, irrelevant, or noisy features within this high-dimensional data can significantly impede model performance, leading to overfitting, reduced generalizability, and increased computational cost. This application note addresses this critical challenge by detailing a robust methodology that integrates Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to identify an optimal subset of molecular descriptors, thereby enhancing the predictive accuracy and efficiency of models in drug discovery pipelines.

Quantitative Analysis of RFE and Alternative Feature Selection Methods

The performance of various feature selection techniques, including RFE, was quantitatively evaluated on a molecular dataset involving cathepsins B, S, D, and K [1]. The results, summarized in the tables below, demonstrate the effectiveness of these methods in reducing dimensionality while maintaining high model accuracy.

Table 1: Performance of Feature Selection Methods on Cathepsin B Classification

This table compares the test accuracy and feature reduction achieved by Correlation-based, Variance Threshold, and RFE methods.

| Method | File Index | Number of Features | Size Decrease | Test Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | 1 | 168 | 22% | 0.971 |

| Correlation | 2 | 81 | 62% | 0.964 |

| Correlation | 3 | 45 | 79% | 0.898 |

| Variance | 1 | 186 | 14.2% | 0.975 |

| Variance | 2 | 141 | 35.2% | 0.965 |

| Variance | 3 | 114 | 47.5% | 0.970 |

| RFE | 1 | 130 | 40.2% | 0.968 |

| RFE | 2 | 90 | 58.5% | 0.968 |

| RFE | 3 | 50 | 76.9% | 0.970 |

| RFE | 4 | 40 | 81.5% | 0.960 |

Table 2: Final 1D CNN Model Accuracy Across Different Cathepsins

This table shows the final classification accuracy achieved by the 1D CNN model after feature selection, demonstrating the high performance attainable with a refined feature set [1].

| Target | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| Cathepsin B | 97.692% |

| Cathepsin S | 87.951% |

| Cathepsin D | 96.524% |

| Cathepsin K | 93.006% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Data Preprocessing

This protocol details the initial steps for preparing molecular data for analysis.

2.1.1 Reagents and Materials

- Source Databases: BindingDB and/or ChEMBL databases containing molecular structures (SMILES format) and annotated bioactivity data (e.g., IC50 values) [1].

- Software Library: RDKit (Open-source cheminformatics software).

2.1.2 Procedure

- Data Retrieval: Download molecular structures in SMILES format and their corresponding experimental IC50 values for the target of interest (e.g., cathepsins) from BindingDB or ChEMBL.

- Data Curation:

- Filter data to retain only entries relevant to the study (e.g., human species).

- Remove any entries with missing critical values (e.g., NaN IC50 values) [1].

- Activity Labeling: Classify molecules based on IC50 values into categorical activity classes (e.g., Potent, Active, Intermediate, Inactive) [1].

- Descriptor Calculation: Use RDKit to compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (e.g., 217 descriptors) directly from the SMILES strings. This generates the initial high-dimensional feature matrix [1].

- Data Augmentation (if applicable): To address class imbalance, apply the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to the feature matrix to generate synthetic samples for the minority classes [1].

Protocol 2: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for Molecular Descriptors

This protocol describes the core feature selection process using RFE [2] [3].

2.2.1 Reagents and Materials

- Programming Environment: Python.

- Primary Library: scikit-learn (

sklearn.feature_selection.RFE).

2.2.2 Procedure

- Estimator Selection: Choose a supervised learning estimator that provides feature importance scores. For example,

DecisionTreeClassifier()or a linear model withcoef_attribute can be used [3]. - RFE Initialization: Initialize the RFE class, specifying the estimator and the desired number of features to select (

n_features_to_select). Thestepparameter can be set to control how many features are removed per iteration [2] [3]. - Model Fitting: Fit the RFE model on the preprocessed training dataset (the feature matrix from Protocol 1 and the activity labels).

- Feature Identification: After fitting, the

support_attribute provides a boolean mask indicating the selected features. Theranking_attribute shows the ranking of all features, with rank 1 assigned to the selected ones [2] [3]. - Data Transformation: Use the fitted RFE object to transform the training and test datasets, creating new datasets containing only the selected features.

Protocol 3: 1D CNN Model for Molecular Activity Classification

This protocol outlines the construction and training of a 1D CNN model on the selected molecular descriptors [1] [4].

2.3.1 Reagents and Materials

- Deep Learning Framework: TensorFlow/Keras or PyTorch.

2.3.2 Procedure

- Model Architecture:

- Input Layer: Accepts the 1D vector of selected molecular descriptors.

- 1D Convolutional Layers: Stack one or more 1D CNN layers to extract local patterns and hierarchical features from the descriptor vector. Use ReLU activation functions.

- Pooling Layers: Incorporate 1D max-pooling layers after convolutional layers to reduce dimensionality and enhance translational invariance.

- Flatten Layer: Flatten the output from the final convolutional/pooling layer.

- Fully Connected (Dense) Layers: Add one or more dense layers to combine features for final classification.

- Output Layer: A dense layer with a softmax activation function for multi-class classification.

- Model Compilation: Compile the model with an appropriate optimizer (e.g., Adam), a loss function (e.g., categorical cross-entropy), and metrics (e.g., accuracy).

- Model Training: Train the model on the training set (

X_train_selected) using the validation set for early stopping and hyperparameter tuning. - Model Evaluation: Finally, evaluate the trained model's performance on the held-out test set (

X_test_selected) to determine the final accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score [1].

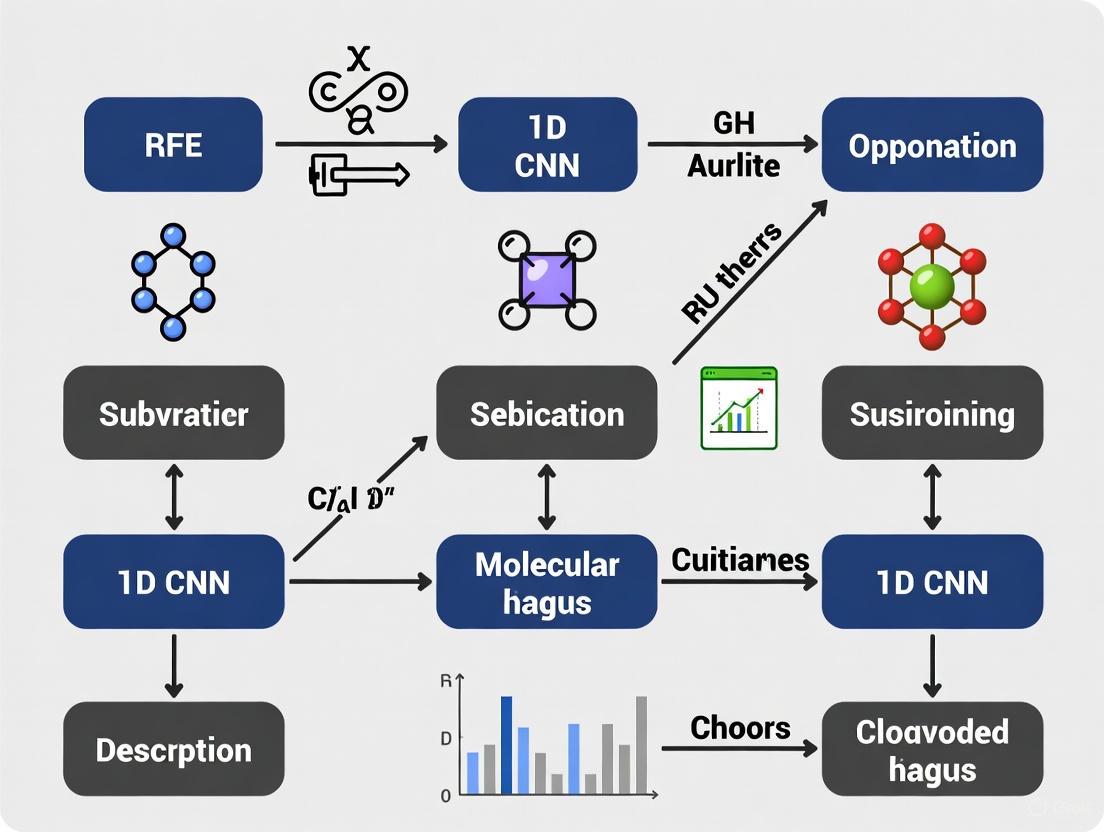

Workflow and Data Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow, from raw data to final model prediction, as described in the protocols.

Molecular Data Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

This table lists the essential materials, software, and data sources required to implement the described methodology.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| BindingDB | Public database of measured binding affinities, providing molecular structures and IC50 values. | https://www.bindingdb.org/ [1] |

| ChEMBL | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for data sourcing. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ [1] |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit used for calculating molecular descriptors from SMILES. | https://www.rdkit.org/ [1] |

| scikit-learn | Core Python library for machine learning, providing the RFE class and various estimators. | https://scikit-learn.org/ [2] [3] |

| 1D CNN Model | Deep learning architecture implemented in TensorFlow/PyTorch for classifying molecular data. | TensorFlow/Keras, PyTorch [1] [4] |

| SMOTE | Algorithm to address class imbalance by generating synthetic samples for minority classes. | imbalanced-learn Python library [1] |

What is Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)? A Deep Dive into the Algorithm

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection algorithm designed to identify the most relevant features in a dataset by recursively eliminating the least important ones [3]. Its core principle is both straightforward and effective: it starts with all available features, fits a model, ranks the features by their importance, prunes the least significant ones, and repeats this process on the reduced feature set until the desired number of features remains [5] [6]. This iterative refinement allows RFE to hone in on a subset of features that are highly predictive of the target variable.

In the context of modern computational drug discovery, particularly in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, the selection of relevant molecular descriptors is paramount [7]. The evolution from classical statistical methods to advanced machine learning and deep learning approaches has generated a need for robust feature selection techniques that can handle high-dimensional descriptor spaces. RFE meets this need by effectively reducing dimensionality, which can improve model performance, enhance generalizability, and accelerate training times [5] [8]. By eliminating noisy or redundant variables, RFE helps create models that are not only more accurate but also more interpretable for researchers [9].

How the RFE Algorithm Works

The Core Iterative Process

The RFE algorithm operates through a recursive sequence of steps, creating a finely-tuned subset of features. The workflow is as follows:

- Model Training: Begin by fitting a specified machine learning model (the

estimator) to the entire set ofnfeatures. - Feature Ranking: Calculate the importance of each feature. This is typically derived from model-specific attributes such as

coef_for linear models orfeature_importances_for tree-based models [3] [2]. - Feature Pruning: Remove the

kleast important feature(s), wherekis defined by thestepparameter [2]. - Recursion: Repeat steps 1 through 3 on the pruned feature set.

- Termination: The recursion halts when the number of features remaining equals the user-specified

n_features_to_select[3].

This process is visualized in the workflow diagram below.

Determining the Optimal Number of Features with RFECV

A critical challenge in using standard RFE is that the optimal number of features is often unknown a priori. Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) addresses this by automatically determining the best number of features [10].

RFECV performs RFE iteratively within a cross-validation loop for different feature subset sizes. It calculates a performance score for each subset size and selects the size that yields the highest cross-validated score [10]. This process robustly incorporates the variability of feature selection into performance evaluation, mitigating the risk of overfitting and providing a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data [11]. The following table summarizes a typical RFECV output, showing how performance metrics can vary with the number of features selected.

Table 1: Example RFECV Performance Profile Across Different Feature Subset Sizes (Simulated Data)

| Number of Features | Cross-Val Accuracy (Mean) | Cross-Val Accuracy (Std. Dev.) | Selected |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.379 | 0.215 | |

| 2 | 0.499 | 0.201 | |

| 3 | 0.611 | 0.158 | |

| 4 | 0.666 | 0.197 | Yes |

| 5 | 0.657 | 0.186 | |

| 10 | 0.597 | 0.178 | |

| 15 | 0.571 | 0.199 |

RFE in Practice: Protocols for Molecular Descriptor Selection

A Basic Protocol Using scikit-learn

This protocol outlines the steps for implementing RFE using Python's scikit-learn library, a common tool in computational chemistry pipelines [3] [7].

Advanced Protocol: Tuning with RFECV

For research-grade feature selection, integrating cross-validation is crucial. This protocol uses RFECV to find the optimal number of features automatically [10].

The visualization generated by this code typically shows a plot of cross-validated performance versus the number of features. The optimal number is indicated by the peak of the curve, allowing researchers to make an informed decision.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions in an RFE experiment for molecular descriptor selection.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RFE Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function & Purpose | Example Tools / Libraries |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | The core model used to compute feature importance; its choice critically influences selected features. | RandomForestClassifier, SVC(kernel='linear'), LogisticRegression [3] [5] [8] |

| Descriptor Standardizer | Pre-processes molecular descriptors to have zero mean and unit variance, ensuring stable model training. | StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler from scikit-learn [8] |

| Model Validation Framework | Robustly evaluates performance and guards against overfitting by incorporating feature selection variability. | RepeatedStratifiedKFold, cross_val_score from scikit-learn [3] [11] |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculator | Generates numerical representations (features) from molecular structures. | RDKit, PaDEL, DRAGON [7] |

| Pipeline Tool | Ensures data pre-processing and feature selection are correctly applied during model validation. | Pipeline from scikit-learn [3] |

| Hyperparameter Optimizer | Automates the search for the best model and RFE parameters (e.g., n_features_to_select, step). |

Optuna, GridSearchCV [12] |

Advantages, Limitations, and Best Practices

Advantages and Limitations

RFE offers several distinct advantages, along with some considerations that researchers must account for.

Table 3: Advantages and Limitations of Recursive Feature Elimination

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Model-Agnostic Flexibility: Can be used with any estimator that provides feature importance scores (e.g., linear models, SVMs, tree-based models) [5] [8]. | Computational Cost: Iteratively refitting models can be slow for very large datasets or complex models [5] [8]. |

| Interaction Awareness: As a wrapper method, it accounts for interactions between features, unlike simple filter methods [8]. | Model Dependency: The final feature subset is heavily dependent on the underlying estimator used for ranking [5]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction: Effectively handles high-dimensional data, improving model efficiency and interpretability [5] [9]. | Risk of Overfitting: Without proper cross-validation, the feature selection process itself can overfit the training data [11]. |

Best Practices for Robust Feature Selection

To mitigate limitations and ensure reliable results, adhere to the following best practices:

- Preprocess Data: Always standardize or normalize your data before applying RFE, especially when using models sensitive to feature scales (e.g., SVMs, linear models) [5] [8].

- Leverage Cross-Validation: Always use RFECV or encapsulate the RFE process within an outer resampling loop to obtain unbiased performance estimates and select the optimal number of features [11] [10]. This is critical for avoiding overfitting and "selection bias" [11].

- Choose a Simple Base Estimator: For faster and more transparent feature selection, start with a simple, interpretable model like a Linear SVM or Logistic Regression [5].

- Validate on Hold-Out Sets: After selecting features using a cross-validated process, perform a final evaluation on a completely held-out test set to validate the model's generalizability [8].

Recursive Feature Elimination stands as a powerful and versatile technique for feature selection, particularly well-suited for the high-dimensionality challenges inherent in molecular descriptor selection for QSAR modeling and drug discovery [7]. Its ability to iteratively refine feature subsets based on model-derived importance makes it a superior choice over simpler filter methods. When combined with rigorous cross-validation, as in RFECV, it provides a robust framework for building predictive, interpretable, and efficient models. Integrating RFE with advanced deep learning architectures like 1D CNNs presents a promising frontier for further enhancing the precision and power of computational pipelines in scientific research.

1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) for Molecular Sequence Feature Extraction

The application of 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNNs) has revolutionized feature extraction from molecular sequences in modern computational drug discovery. These architectures excel at processing sequential biological data including DNA sequences, protein sequences, and Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) representations of chemical compounds. Within the broader context of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with 1D-CNN for molecular descriptor selection, these networks serve as powerful tools for automated feature discovery, identifying the most informative patterns within molecular data while reducing reliance on manual descriptor engineering [13] [14].

The fundamental advantage of 1D-CNNs lies in their ability to automatically learn hierarchical representations from raw sequence data through convolutional filters that scan along the sequence dimension. This capability is particularly valuable for molecular sequences, where local patterns—such as binding motifs in DNA or functional groups in SMILES strings—often determine biological activity and chemical properties [13] [15]. Unlike traditional fingerprint-based methods that require pre-defined structural patterns, 1D-CNNs can discover novel features directly from data, making them exceptionally suited for molecular descriptor selection in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and drug response prediction [7] [14].

Theoretical Foundations of 1D-CNN for Molecular Sequences

Architecture Components and Their Molecular Applications

1D-CNNs process molecular sequences through a series of specialized layers, each serving a distinct purpose in feature extraction and descriptor selection:

Convolutional Layers: These layers apply multiple filters that slide along the input sequence to detect local patterns. For molecular sequences, these filters effectively function as motif detectors that identify conserved subpatterns indicative of biological function or chemical properties. Each filter specializes in recognizing specific sequence features, with filter width determining the receptive field size—narrower filters capture localized features (e.g., individual atom interactions), while wider filters recognize extended motifs (e.g., binding sites) [13] [15].

Activation Functions: The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is commonly applied after convolution operations to introduce non-linearity, enabling the network to learn complex, non-linear relationships in molecular data. This non-linearity is essential for modeling the intricate relationships between molecular structure and biological activity [14].

Pooling Layers: Max-pooling operations reduce spatial dimensionality while retaining the most salient features, providing translation invariance and controlling overfitting. This is particularly valuable for molecular sequences where the relative position of functional groups may vary, but their presence remains predictive of activity [14].

Fully Connected Layers: These layers integrate the extracted features for final prediction tasks. In RFE frameworks, the weights connecting the last convolutional/pooling layer to the first fully connected layer can indicate feature importance, guiding descriptor selection [14].

Molecular Sequence Representation

Effective representation of molecular structures as sequences is fundamental to 1D-CNN applications:

SMILES Representation: SMILES notation encodes molecular structures as linear strings using ASCII characters, providing a compact representation that preserves structural information including branching, cyclization, and chirality. For example, the SMILES string for Aspirin is "CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O" [13].

One-Hot Encoding: SMILES strings and biological sequences are typically converted into numerical representations via one-hot encoding. For DNA sequences, this creates a 4-dimensional binary vector (A=[1,0,0,0], T=[0,1,0,0], C=[0,0,1,0], G=[0,0,0,1]) at each position. Similarly, SMILES strings employ an extended encoding scheme that incorporates atomic properties and special characters [15].

Distributed Representations: Advanced approaches use learned embeddings for molecular substructures, creating dense vector representations that capture chemical similarity more effectively than one-hot encoding [13].

Table 1: 1D-CNN Configuration Guidelines for Different Molecular Sequence Types

| Sequence Type | Recommended Input Encoding | Typical Filter Sizes | Pooling Strategy | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequences | One-hot (4-dimensional) | 4-12 nucleotides | Max pooling (size 2-4) | Transcription factor binding prediction, SNP detection |

| Protein Sequences | One-hot (20-dimensional) | 3-10 amino acids | Max pooling (size 2-4) | Protein family classification, binding site prediction |

| SMILES Strings | Extended one-hot (42-dimensional) | 2-8 characters | Global average pooling | Chemical property prediction, toxicity classification |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Molecular Informatics

Compound Property Prediction and Virtual Screening

1D-CNNs applied to SMILES representations have demonstrated remarkable performance in predicting molecular properties essential for drug discovery. In benchmark studies using the TOX 21 dataset, SMILES-based 1D-CNNs outperformed conventional fingerprint methods like Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP) and achieved performance comparable to the winning model of the TOX 21 Challenge [13]. The network architecture successfully learned to identify toxicophores—structural features associated with compound toxicity—directly from SMILES strings without explicit structural specification.

These models transform SMILES strings into a distributed representation comprising 42 features—21 representing atomic properties (atom type, degree, charge, chirality) and 21 encoding SMILES-specific symbols. The convolutional filters then scan these representations to detect functional groups and substructures predictive of biological activity [13]. This approach enables representation learning, where the network automatically discovers effective molecular descriptors optimized for specific prediction tasks, surpassing the limitations of pre-defined fingerprint methods [13] [7].

DNA-Protein Binding Prediction

1D-CNNs have proven highly effective in predicting sequence-specific DNA-protein interactions, a fundamental challenge in genomics and gene regulation studies. In a representative implementation, DNA sequences of length 50 were one-hot encoded into a 4×50 matrix and processed through a 1D-CNN architecture containing:

- A convolutional layer with multiple filters scanning along the sequence dimension

- A max-pooling layer to reduce dimensionality

- Fully connected layers for binary classification (binding/non-binding) [15]

The trained model could accurately predict binding sites and, through filter visualization, identify conserved sequence motifs recognized by DNA-binding proteins. This demonstrates how 1D-CNNs serve as both predictive tools and discovery platforms for important biological patterns [15].

PCR Amplification Efficiency Prediction

In a sophisticated application published in Nature Communications (2025), 1D-CNNs were employed to predict sequence-specific amplification efficiency in multi-template polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments. The model achieved an AUROC of 0.88 and AUPRC of 0.44, successfully identifying sequences with poor amplification characteristics based solely on their nucleotide sequence [16].

Researchers combined the 1D-CNN with an interpretation framework called CluMo (Motif Discovery via Attribution and Clustering) to identify sequence motifs adjacent to adapter priming sites that correlated with inefficient amplification. This analysis revealed adapter-mediated self-priming as a major mechanism causing amplification bias, challenging established PCR design assumptions [16].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of 1D-CNN Models on Molecular Prediction Tasks

| Application Domain | Dataset | Model Architecture | Performance Metrics | Comparative Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Toxicity Prediction | TOX 21 | SMILES-based 1D-CNN | ROC-AUC: 0.856 (avg) | ECFP: 0.832 (avg), Graph Convolution: 0.841 |

| DNA-Protein Binding | Simulated DNA sequences | 1D-CNN with one-hot encoding | Accuracy: >85% | Not reported |

| PCR Amplification Efficiency | Synthetic DNA pools | 1D-CNN with CluMo interpretation | AUROC: 0.88, AUPRC: 0.44 | Traditional motif discovery methods |

| Drug Response Prediction | TCGA Low Grade Glioma | 1D-CNN with attention mechanism | Accuracy: 84.6%, AUC: Improved over RF | Random Forest: 80.1% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SMILES-Based Compound Classification Using 1D-CNN

This protocol details the implementation of a 1D-CNN for predicting compound properties from SMILES representations, adapted from the methodology described in [13].

Materials and Software Requirements

- RDKit (2016.09.4 or newer) for SMILES processing and feature calculation

- Deep learning framework (Chainer, TensorFlow, or PyTorch)

- Compound datasets with associated activity/toxicity labels (e.g., TOX 21)

Procedure

Data Preparation

- Obtain canonical SMILES representations for all compounds using RDKit

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- Apply appropriate stratification to maintain class distribution across splits

SMILES Feature Matrix Construction

- Convert each SMILES string to a feature matrix of dimensions (sequence_length × 42)

- For each character in the SMILES string, compute a 42-dimensional feature vector:

- 21 features encoding atomic properties (atom type, degree, charge, chirality)

- 21 features encoding SMILES-specific symbols as one-hot vectors

- Pad or truncate sequences to a fixed length (e.g., 150 characters)

Model Architecture Configuration

Model Training

- Compile model with Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss

- Train with batch size of 32-128 for 50-100 epochs

- Implement early stopping based on validation loss with patience of 10 epochs

- Monitor ROC-AUC on validation set for model selection

Model Interpretation

- Extract activations from first convolutional layer to identify important subsequences

- Apply motif detection algorithms to identify conserved chemical motifs

- Validate identified motifs against known toxicophores or functional groups

Protocol 2: DNA-Protein Binding Prediction with 1D-CNN

This protocol describes the procedure for predicting DNA-protein binding sites from sequence data using 1D-CNN, based on the approach outlined in [15].

Materials and Software Requirements

- DNA sequences with binding labels (positive and negative sets)

- One-hot encoding utilities

- Keras with TensorFlow backend or equivalent deep learning framework

Procedure

Data Preprocessing

- Obtain DNA sequences of fixed length (e.g., 50 base pairs)

- Balance positive (binding) and negative (non-binding) examples

- One-hot encode sequences: A=[1,0,0,0], T=[0,1,0,0], C=[0,0,1,0], G=[0,0,0,1]

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., 70/15/15%)

Model Construction

Model Training and Evaluation

- Compile with binary cross-entropy loss and Adam optimizer (learning rate=0.001)

- Train with batch size 32, monitoring validation accuracy

- Evaluate using AUC-ROC, precision-recall curves, and accuracy metrics

- Visualize first-layer filters as sequence motifs to interpret binding preferences

Protocol 3: Integrating 1D-CNN with RFE for Molecular Descriptor Selection

This protocol outlines the integration of 1D-CNN with Recursive Feature Elimination for optimal molecular descriptor selection in QSAR modeling.

Procedure

Initial Model Training

- Train a 1D-CNN model on the complete molecular dataset (sequences + properties)

- Use a global average pooling layer after the final convolutional layer

- Extract the pooled features as learned molecular descriptors

Feature Importance Ranking

- Compute gradient-based importance scores for input sequence positions

- Alternatively, use attention mechanisms to weight important subsequences

- Rank features (sequence regions) by their contribution to prediction

Recursive Feature Elimination

- Iteratively remove the least important features (sequence regions)

- Retrain the model on the reduced feature set

- Track performance metrics to identify the optimal feature subset

Validation and Model Selection

- Validate the selected descriptors on independent test sets

- Compare against traditional fingerprint methods

- Assess model interpretability by mapping important features to chemical structures

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for molecular feature extraction using 1D-CNN within an RFE framework:

Diagram 1: 1D-CNN with RFE Workflow for Molecular Descriptor Selection

The signaling pathway for 1D-CNN based molecular feature extraction can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: 1D-CNN Molecular Feature Extraction Signaling Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for 1D-CNN Molecular Sequence Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | SMILES processing, molecular feature calculation, descriptor generation | Compute atomic features for SMILES representation; generate molecular graphs [13] |

| TensorFlow/Keras | Deep Learning Framework | 1D-CNN model construction, training, and evaluation | Implement end-to-end deep learning pipelines for sequence classification [15] |

| PyTorch | Deep Learning Framework | Flexible neural network implementation, custom layer development | Build specialized 1D-CNN architectures with attention mechanisms [17] |

| Chainer | Deep Learning Framework | 1D-CNN implementation for SMILES strings (reference implementation) | Reproduce SMILES-CNN models from original research [13] |

| DNA Sequence Datasets | Biological Data | Model training and validation for genomics applications | Predict transcription factor binding sites; identify regulatory elements [15] |

| TOX21 Dataset | Compound Screening Data | Benchmarking compound toxicity prediction models | Evaluate SMILES-based 1D-CNN against traditional fingerprint methods [13] |

| GDSC/CCLE | Drug Response Database | Drug sensitivity data for predictive modeling | Train models predicting drug response from molecular features [18] |

1D Convolutional Neural Networks represent a powerful paradigm for molecular sequence feature extraction, consistently demonstrating superior performance across diverse applications in drug discovery and molecular informatics. Their capacity to automatically learn informative descriptors directly from raw sequences—whether DNA, protein, or SMILES representations—makes them particularly valuable for recursive feature elimination approaches seeking optimal molecular representations.

The integration of 1D-CNNs within RFE frameworks enables more efficient and interpretable molecular descriptor selection, moving beyond the limitations of pre-defined fingerprint methods. As these techniques continue to evolve, particularly with improvements in model interpretability and handling of 3D structural information, they promise to further accelerate computational drug discovery and enhance our understanding of molecular determinants of biological activity.

Why Combine RFE and 1D-CNN? Synergistic Advantages for Descriptor Selection

In modern computational drug discovery, the selection of optimal molecular descriptors is a critical step for building robust and interpretable Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. The integration of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN) represents an advanced methodological framework that leverages the complementary strengths of traditional feature selection and deep learning. This hybrid approach addresses a fundamental challenge in cheminformatics: identifying the most predictive subset of molecular descriptors from high-dimensional data while capturing complex, non-linear relationships between molecular structure and biological activity.

The RFE-1D-CNN framework operates on a synergistic principle where RFE performs an efficient, model-guided search through the descriptor space, while the 1D-CNN excels at automatically learning relevant patterns from the optimized feature set. This combination is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research, where model interpretability is as crucial as predictive accuracy for regulatory acceptance and hypothesis generation. By systematically eliminating the least important features, RFE reduces the risk of overfitting and creates a more manageable input dimension for the 1D-CNN, which in turn detects local patterns and interactions among the remaining descriptors that might be missed by conventional machine learning algorithms [7] [19].

Theoretical Foundations and Synergistic Mechanisms

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Fundamentals

Recursive Feature Elimination operates through an iterative process that ranks features based on a chosen model's feature importance metrics and sequentially removes the least important ones. The algorithm begins with the full set of descriptors and progressively eliminates features until an optimal subset is achieved. This process requires an external estimator that assigns weights to features, typically through feature importance scores or model coefficients [19]. The RFE procedure is particularly effective in domains with high-dimensional data, such as cheminformatics, where the number of molecular descriptors often exceeds the number of compounds in the training set.

The robustness of RFE stems from its ability to accommodate various estimator types, including Random Forests (RF) and Support Vector Machines (SVM), which provide different perspectives on feature importance. RF-based RFE captures feature relevance through Gini importance or mean decrease in accuracy, while SVM-based RFE utilizes the magnitude of coefficients in the hyperplane decision function. For molecular descriptor selection, this multi-faceted assessment of feature importance is crucial, as different descriptor types (e.g., topological, electronic, and geometric) may exhibit varying predictive powers across different biological endpoints [7] [19].

1D-CNN Architecture for Structured Descriptor Data

The one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network architecture is uniquely suited for processing molecular descriptor data due to its ability to capture local dependencies and hierarchical patterns in sequentially structured information. Unlike fully connected networks, 1D-CNNs employ convolutional filters that slide along the descriptor dimension, detecting local interactions between adjacent or nearby descriptors in the input vector. This local receptive field enables the network to identify substructure representations and non-linear descriptor interactions that collectively influence molecular properties [20] [21].

A typical 1D-CNN architecture for molecular property prediction consists of multiple convolutional layers followed by pooling layers, which progressively transform the input descriptors into increasingly abstract representations. The initial layers may detect simple combinations of descriptors, while deeper layers identify more complex, higher-order interactions. This hierarchical feature learning mirrors the conceptual organization of molecular descriptors, where simple atomic properties give rise to complex molecular behaviors. The parameter-sharing characteristic of CNNs significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters compared to fully connected networks, making them more suitable for datasets of limited size, which is common in drug discovery projects [4] [22].

Complementary Strengths and Synergistic Effects

The integration of RFE and 1D-CNN creates a powerful synergy that transcends the capabilities of either method alone. RFE contributes dimensionality reduction and feature relevance assessment, effectively pruning redundant, irrelevant, or noisy descriptors that could impede model performance. This pre-processing step enhances the signal-to-noise ratio in the input data, allowing the subsequent 1D-CNN to focus its computational resources on learning patterns from the most informative descriptors. Moreover, RFE improves model interpretability by identifying a minimal set of descriptors that collectively maximize predictive power, providing medicinal chemists with actionable insights for compound optimization [19].

The 1D-CNN component complements RFE by capturing complex non-linear relationships and higher-order descriptor interactions that may be missed by the linear or tree-based models typically used in RFE. While RFE identifies which descriptors are important, the 1D-CNN reveals how these descriptors interact to influence biological activity. This division of labor creates a more robust and predictive modeling pipeline. Additionally, the 1D-CNN's ability to perform automatic feature engineering from the preselected descriptors reduces the reliance on manual descriptor design and selection, which often requires extensive domain expertise and can introduce human bias [20] [22].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of RFE, 1D-CNN, and Their Hybrid Approach

| Aspect | RFE Alone | 1D-CNN Alone | RFE-1D-CNN Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Selection | Explicit, interpretable selection | Implicit, data-driven selection | Explicit pre-selection followed by implicit refinement |

| Handling High-Dimensional Data | Excellent through iterative elimination | Challenging without preprocessing | Optimal through staged dimensionality reduction |

| Non-Linear Relationship Capture | Limited (depends on base estimator) | Excellent through hierarchical learning | Excellent with focused computational resources |

| Model Interpretability | High (clear feature importance) | Moderate (requires interpretation techniques) | High (clear feature importance with interaction insights) |

| Computational Efficiency | Efficient for feature selection | Computationally intensive for raw high-dimensional data | Balanced approach with optimized resource allocation |

| Descriptor Interaction Analysis | Limited to pairwise correlations | Comprehensive multi-level interactions | Focused analysis on relevant descriptor interactions |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Molecular Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

The successful implementation of the RFE-1D-CNN framework begins with comprehensive data curation and strategic preprocessing. Molecular datasets should be carefully selected to represent diverse chemical spaces relevant to the therapeutic area of interest. For QSAR applications, compounds must be represented by a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors encompassing topological, electronic, geometric, and quantum chemical properties. These descriptors can be computed using tools like RDKit, PaDEL, or DRAGON, which generate numerical representations capturing different aspects of molecular structure [7].

Prior to feature selection, appropriate data scaling is essential, as molecular descriptors often exist on different scales, which can bias both the RFE process and CNN training. Z-score standardization or min-max scaling should be applied to ensure all descriptors contribute equally to the model. Additionally, the dataset should be partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using stratified sampling or time-based splitting to maintain similar distribution of activity classes across sets and prevent data leakage. For small datasets, cross-validation strategies should be employed to obtain reliable performance estimates [7] [23].

RFE Implementation for Molecular Descriptors

The RFE procedure for molecular descriptor selection follows a systematic protocol. First, an appropriate base estimator must be selected; Random Forest is often preferred for its robustness and ability to capture non-linear trends, though SVM with linear kernel can be effective for high-dimensional data. The implementation begins with training the initial model on all descriptors, followed by ranking descriptors based on their importance scores. A predetermined fraction of the least important descriptors (e.g., 10-20%) is then eliminated, and the process repeats with the reduced descriptor set [19].

The optimal number of descriptors can be determined through cross-validation performance monitoring, where the descriptor subset that maximizes the validation performance is selected. Alternatively, domain knowledge can inform the stopping criterion, ensuring the final descriptor set remains interpretable and chemically meaningful. For enhanced stability, the RFE process can be repeated with different data splits or base estimators, with only the consistently selected descriptors retained. This consensus approach reduces the variance in feature selection and yields more robust descriptor sets [19].

1D-CNN Architecture Design and Optimization

The 1D-CNN architecture for processing the RFE-selected descriptors requires careful design to balance model capacity and generalization. A typical architecture begins with an input layer sized to match the number of selected descriptors, followed by one or more 1D convolutional layers with increasing filter counts (e.g., 64, 128, 256) and small kernel sizes (3-5). Each convolutional layer should be followed by a rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation function and optionally a 1D max-pooling layer to reduce dimensionality and introduce translational invariance [20] [21].

Following the convolutional blocks, the architecture should include a global average pooling layer or flattening layer to convert the feature maps into a vector, followed by fully connected layers for final prediction. To prevent overfitting, which is common in QSAR modeling due to limited dataset sizes, regularization techniques such as Dropout, L2 weight regularization, and early stopping should be incorporated. Hyperparameter optimization should focus on the learning rate, number of filters, kernel size, and dropout rate, using Bayesian optimization or grid search approaches [4] [21].

Model Interpretation and Validation

The interpretation of RFE-1D-CNN models requires specialized techniques to extract insights about which molecular descriptors and interactions drive predictions. Saliency maps and activation maximization methods can identify which input descriptors most influence the model's output for specific compounds. Additionally, layer-wise relevance propagation can decompose the prediction into contributions from individual descriptors, providing compound-specific explanations [24] [22].

Robust validation is essential to ensure model reliability and prevent overfitting. Beyond standard train-test splits, external validation on completely independent datasets provides the most realistic assessment of predictive performance. Y-scrambling (label randomization) should be performed to verify that the model learns true structure-activity relationships rather than dataset artifacts. For regulatory applications, validation should adhere to OECD QSAR validation principles, including defined endpoints, unambiguous algorithms, appropriate measures of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity, and a mechanistic interpretation when possible [7].

Application Notes for Drug Discovery Workflows

Virtual Screening and Lead Optimization

The RFE-1D-CNN framework demonstrates particular utility in virtual screening campaigns where computational efficiency and predictive accuracy are both critical. After training on experimentally characterized compounds, the model can rapidly prioritize candidates from large virtual libraries for experimental testing. The RFE component ensures that predictions rely on a minimal set of interpretable descriptors, while the 1D-CNN captures complex patterns that improve screening enrichment. In lead optimization, the model can guide structural modifications by identifying which molecular features most strongly influence the target property, enabling medicinal chemists to focus on modifications with the highest probability of success [7] [23].

For virtual screening applications, the RFE-1D-CNN pipeline should be integrated with molecular docking or pharmacophore modeling to create a consensus scoring approach that leverages both structure-based and ligand-based methods. This multi-faceted strategy increases the probability of identifying truly active compounds by addressing the limitations of individual methods. The computational efficiency of the optimized 1D-CNN enables the screening of ultra-large libraries (millions to billions of compounds) when combined with appropriate infrastructure, significantly expanding the accessible chemical space for hit identification [7].

ADMET Property Prediction

The prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties represents an ideal application for the RFE-1D-CNN framework, as these endpoints are influenced by complex, often non-linear, relationships between molecular structure and biological activity. For example, models predicting blood-brain barrier permeability or hepatic metabolic stability benefit from the framework's ability to identify key molecular descriptors while capturing their complex interactions. The interpretability afforded by RFE helps identify structural features that influence ADMET properties, guiding the design of compounds with improved pharmacokinetic profiles [7].

When deploying RFE-1D-CNN for ADMET prediction, dataset quality is particularly important, as experimental data for these endpoints often contain higher noise levels than primary activity data. Ensemble modeling approaches, where multiple RFE-1D-CNN models are trained on different data splits or descriptor subsets, can improve robustness and provide uncertainty estimates. For regulatory submissions, detailed documentation of the selected descriptors and their hypothesized relationship to the endpoint strengthens the mechanistic basis of the predictions and facilitates review [7] [21].

Multi-Task Learning for Compound Profiling

In lead optimization, simultaneous optimization of multiple properties is often necessary, creating an ideal scenario for multi-task learning extensions of the RFE-1D-CNN framework. A shared 1D-CNN backbone can process the RFE-selected descriptors, with task-specific heads predicting different properties (e.g., potency, solubility, metabolic stability). This approach leverages correlations between related endpoints while reducing the total number of parameters compared to separate models, improving generalization, especially for endpoints with limited data [22].

For multi-task implementations, the RFE procedure can be adapted to identify descriptors relevant across multiple endpoints (shared branch) and those specific to individual endpoints (task-specific branches). This hierarchical feature selection provides insights into which molecular features influence multiple properties versus those with selective effects, informing the design of compounds with balanced profiles. The computational efficiency of the optimized 1D-CNN architecture makes such sophisticated multi-task approaches feasible even with moderate computational resources [24] [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Property Prediction Methods on Benchmark Datasets

| Method | Average Accuracy (%) | ROC-AUC | Interpretability Score (1-5) | Computational Efficiency (1-5) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical QSAR (MLR/PLS) | 72.5 | 0.79 | 5 | 5 | High interpretability, computational efficiency |

| Random Forest | 81.3 | 0.86 | 4 | 4 | Robust to noise, inherent feature importance |

| Standard 1D-CNN | 84.7 | 0.88 | 3 | 3 | Automatic feature learning, high accuracy |

| Graph Neural Networks | 86.2 | 0.90 | 2 | 2 | Direct structure processing, state-of-the-art accuracy |

| RFE-1D-CNN Hybrid | 85.8 | 0.89 | 4 | 3 | Balanced performance and interpretability |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for RFE-1D-CNN Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Packages | Key Functionality | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, DRAGON | Molecular descriptor calculation | RDKit offers open-source comprehensive descriptor calculation; DRAGON provides proprietary extensive descriptor library |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | RFE implementation and 1D-CNN development | Scikit-learn provides robust RFE implementation; TensorFlow/PyTorch offer flexible CNN design |

| Feature Selection Utilities | Scikit-learn RFE, MLxtend, Boruta | Recursive feature elimination | Scikit-learn's RFE offers basic functionality; Boruta provides all-relevant feature selection |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, Morgan Fingerprints, 3D Descriptors | Alternative molecular representations | SMILES strings require different architectures; 3D descriptors capture spatial molecular geometry |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP, LIME, Captum | Model interpretability and descriptor importance | SHAP provides consistent feature importance scores; LIME offers local interpretability |

Visual Workflow Representation

Diagram 1: RFE-1D-CNN Integrated Workflow for Molecular Descriptor Selection and Property Prediction

The integration of Recursive Feature Elimination with one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks represents a significant advancement in molecular descriptor selection and property prediction. This hybrid framework successfully balances the competing demands of predictive accuracy and model interpretability by leveraging the complementary strengths of traditional feature selection and deep learning. The RFE component provides a principled approach to dimensionality reduction, identifying a minimal set of chemically meaningful descriptors, while the 1D-CNN captures complex, non-linear relationships and higher-order descriptor interactions that would be difficult to detect with conventional methods.

For drug discovery researchers, this approach offers a practical solution to the challenge of building QSAR models that are both highly predictive and chemically interpretable. The ability to identify key molecular descriptors and understand how their interactions influence biological activity provides valuable insights for lead optimization and compound design. As deep learning continues to transform computational chemistry, hybrid approaches like RFE-1D-CNN will play an increasingly important role in bridging the gap between traditional cheminformatics and modern artificial intelligence, ultimately accelerating the discovery of new therapeutic agents.

In the fields of chemoinformatics and drug discovery, the quantitative representation of molecular structures is a foundational step for predicting compound properties and activities. Molecular descriptors and fingerprints convert chemical structures into numerical values, enabling the application of machine learning (ML) algorithms. These representations facilitate tasks such as Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, virtual screening, and molecular property prediction (MPP). The choice of representation is critical, as it directly influences the performance and interpretability of predictive models. This Application Note provides a detailed overview of common molecular descriptors and representations, framed within research on Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) combined with 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for descriptor selection. We include structured protocols and data to guide researchers in selecting and utilizing these representations effectively.

Molecular Descriptors: Categories and Applications

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that encapsulate chemical information about a molecule. They are typically categorized based on the dimensionality of the molecular representation they derive from [25].

Table 1: Categories of Theoretical Molecular Descriptors

| Descriptor Category | Description | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0D (Constitutional) | Based on molecular formula and atom counts, without connectivity or geometry. | Molecular weight, atom count, number of bonds. | Simple, fast to compute, high degeneracy. |

| 1D (Fragments/Listed) | Derived from lists of functional groups or substructures. | List of structural fragments, simple fingerprints. | Accounts for presence/absence of specific chemical groups. |

| 2D (Topological) | Based on molecular graph theory, considering atom connectivity. | Graph invariants, connectivity indices, Wiener index. | Invariant to roto-translation, captures structural patterns. |

| 3D (Geometric) | Derived from the three-dimensional conformation of a molecule. | 3D-MoRSE, WHIM, GETAWAY, quantum-chemical descriptors, surface/volume descriptors. | Low degeneracy, sensitive to conformation, computationally intensive. |

| 4D | Incorporate an ensemble of molecular conformations and/or interactions with probes. | Descriptors from GRID or CoMFA methods, Volsurf. | Captures dynamic molecular behavior. |

A robust molecular descriptor should be invariant to atom labeling and molecular roto-translation, defined by an unambiguous algorithm, and have a well-defined applicability domain [25]. For practical utility, descriptors should also possess a clear structural interpretation, correlate with experimental properties, and exhibit minimal degeneracy (i.e., different structures should yield different descriptor values) [25].

Molecular Fingerprints: Binary and Count-Based Representations

Molecular fingerprints are a specific class of descriptors that represent a molecule as a fixed-length vector, encoding the presence or absence (and sometimes the count) of specific structural patterns.

Table 2: Major Categories of Molecular Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Category | Basis of Generation | Key Examples | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path-Based | Enumerates paths through the molecular graph. | Atom Pair (AP), Depth First Search (DFS) [26]. | Captures linear atom sequences. |

| Pharmacophore-Based | Encodes spatial relationships between pharmacophoric points. | Pharmacophore Pairs (PH2), Triplets (PH3) [26]. | Represents potential for biological interaction. |

| Substructure-Based | Uses a predefined dictionary of structural fragments. | MACCS keys, PubChem fingerprints [26]. | Easily interpretable, but limited to predefined features. |

| Circular | Generates fragments dynamically by iteratively considering atom neighborhoods. | ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint), FCFP (Functional Class Fingerprint) [26]. | Most popular; captures increasing radial environments, excellent for SAR. |

| String-Based | Operates directly on the SMILES string representation. | LINGO, MinHashed (MHFP), MinHashed Atom Pairs (MAP4) [26]. | Avoids need for molecular graph perception. |

The Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP), a circular fingerprint, is considered a de facto standard for drug-like compounds due to its power in capturing structure-activity relationships [27] [26]. However, recent benchmarking on natural products suggests that other fingerprints may sometimes outperform ECFP, highlighting the need for evaluation in specific applications [26].

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Generation and Selection

This section provides detailed methodologies for generating molecular representations and applying feature selection techniques like RFE.

Protocol 1: Generation of Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints

Objective: To generate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors and fingerprints from molecular structures.

Structure Input and Standardization:

- Draw molecular structures using software like ChemDraw or import Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings.

- Standardize structures using toolkits like RDKit or the ChEMBL structure curation package. This includes steps like salt removal, charge neutralization, and tautomer standardization [26].

Geometry Optimization:

- For 3D descriptors, perform molecular mechanics optimization (e.g., using HyperChem with MM+ force fields) followed by more rigorous semi-empirical (e.g., AM1 method) or quantum mechanical (e.g., using MOPAC) optimization until the root mean square gradient is below a threshold (e.g., 0.001 kcal/mol) [28].

Descriptor Calculation:

- Use software such as alvaDesc, Dragon, CODESSA, or Mordred to calculate a wide pool of descriptors (constitutional, topological, geometric, electrostatic, quantum chemical) from the optimized structures [25] [28].

- The RDKit and PaDEL-descriptor packages also provide open-source alternatives for descriptor calculation [25].

Fingerprint Generation:

- Use cheminformatics packages like RDKit, OpenBabel, or specialized libraries to generate fingerprints.

- For ECFP generation using RDKit:

- Input a standardized molecule.

- Use the Morgan algorithm with a specified radius (typically 2 or 3, equivalent to ECFP4 or ECFP6) to generate identifier for each atom environment [27].

- Hash these identifiers into a fixed-length bit vector (e.g., 1024, 2048 bits).

Protocol 2: Feature Selection using SVM-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE)

Objective: To rank and select the most relevant molecular descriptors or fingerprint bits for a predictive task using SVM-RFE.

Background: RFE is a wrapper-style feature selection method that works by recursively removing the least important features and re-building the model [29] [2]. With a linear SVM, feature importance is typically derived from the absolute magnitude of the weight coefficients (coef_) [30].

Data Preparation:

- Split the dataset into training and testing sets.

- Standardize the feature matrix (e.g., scale to zero mean and unit variance).

Model and Selector Initialization:

- Initialize a linear SVM model (

SVR(kernel='linear')orSVC(kernel='linear')). - Initialize the RFE selector from

sklearn.feature_selection[2], specifying:estimator: The linear SVM model.n_features_to_select: The final number of features to select (can be an integer or fraction).step: Number (or fraction) of features to remove per iteration.

- Initialize a linear SVM model (

Feature Ranking:

- Fit the RFE selector on the training data (

selector.fit(X_train, y_train)). - After fitting, access the feature rankings:

selector.ranking_: Provides the ranking of all features, with 1 assigned to the best.selector.support_: A boolean mask indicating the selected features [2].

- Fit the RFE selector on the training data (

Model Retraining and Validation:

- Transform the training and test sets to include only the selected features (

X_train_selected = selector.transform(X_train)). - Retrain the final model on the selected feature set and evaluate its performance on the held-out test set.

- Transform the training and test sets to include only the selected features (

Proposed Protocol: Integrated RFE with 1D-CNN for Descriptor Selection

Objective: To leverage the feature learning capabilities of a 1D-CNN within an RFE framework for robust molecular descriptor selection in QSAR/MPP.

Rationale: While SVMs provide strong linear baselines, CNNs can capture complex, non-linear hierarchical patterns in data. A 1D-CNN is well-suited for the sequential-like structure of descriptor vectors. Integrating a 1D-CNN into RFE allows for feature selection based on learned, non-linear representations.

Data Preprocessing:

- Generate a large pool of molecular descriptors and/or use fingerprints as the initial feature set.

- Standardize the data and partition into training, validation, and test sets.

1D-CNN Model Design:

- Input Layer: Accepts the full feature vector (e.g., 1777 descriptors [31]).

- Convolutional Layers: Apply one or more 1D convolutional layers with ReLU activation to extract local patterns and create feature maps.

- Example Kernel Sizes: 3, 5, 7.

- Pooling Layers: Use global max-pooling after convolutional layers to reduce dimensionality and capture the most salient features [27].

- Fully Connected Layers: Follow with dense layers for final prediction (classification or regression).

Feature Importance Estimation:

- Gradient-based Method: Use the gradients of the model output with respect to the input features as a sensitivity measure. Average the absolute gradients over the training set to estimate feature importance.

- Attention Mechanism: Incorporate an attention layer into the 1D-CNN architecture. The attention weights directly indicate the importance of each input feature for the prediction.

- Perturbation-based Method (RFE-pseudo-samples): Inspired by SVM-RFE with pseudo-samples [29], systematically perturb each feature (setting it to a range of values while holding others constant) and measure the change in the model's prediction (e.g., using Median Absolute Deviation). Features causing larger prediction variability are deemed more important.

Recursive Feature Elimination Loop:

- Train the 1D-CNN model on the current set of features.

- Compute importance scores for all features using one of the methods above.

- Remove the features with the lowest importance (e.g., bottom 10%).

- Repeat the process on the pruned feature set until a predefined number of features remains.

Validation:

- At each RFE iteration, evaluate the model's performance on the validation set to track how feature reduction affects predictive power.

- The optimal feature subset can be chosen as the one with the best validation performance or the smallest number of features before a significant performance drop.

Performance Benchmarking and Data

The choice of molecular representation and machine learning model significantly impacts prediction accuracy. The following table summarizes performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 3: Benchmarking Machine Learning Models and Representations for Molecular Property Prediction

| Model | Representation | Task / Dataset | Performance Metric | Score | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | MS/MS Spectra | Molecular Fingerprint Prediction (F1 Score) | F1 Score | 71% | [32] |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | MS/MS Spectra | Molecular Fingerprint Prediction (F1 Score) | F1 Score | 67% | [32] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | MS/MS Spectra | Molecular Fingerprint Prediction (F1 Score) | F1 Score | 66% | [32] |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | MS/MS Spectra | Molecular Fingerprint Prediction (F1 Score) | F1 Score | 61% | [32] |

| CNN | MS/MS Spectra | Metabolite ID Ranking (Top 1) | Accuracy | 43-50%* | [32] |

| SVM-RFE + Taguchi | Clinical Features | Dermatology Dataset Classification | Accuracy | >95% | [30] |

| FP-BERT (BERT + CNN) | Molecular Fingerprints | Multiple ADME/T Properties | Prediction Performance | "High" / SOTA | [27] |

| Geometric D-MPNN | 2D & 3D Graph | Thermochemistry Prediction | Meets Chemical Accuracy (~1 kcal/mol) | Yes | [33] |

*Performance range depends on using mass-based (43%) or formula-based (50%) candidate retrieval [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Key Software and Databases for Molecular Representation and Modeling

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Source / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Open-source cheminformatics for descriptor/fingerprint calculation, molecule handling. | https://www.rdkit.org |

| Mordred | Software Descriptor Calculator | Calculates a comprehensive set of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors. | https://github.com/mordred-descriptor/mordred |

| alvaDesc | Software Descriptor Calculator | Commercial software for calculating >5,500 molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | https://www.alvascience.com/alvadesc/ |

| PaDEL-descriptor | Software Descriptor Calculator | Open-source software for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | http://www.yapcwsoft.com/dd/padeldescriptor/ |

| scikit-learn | ML Library | Provides implementation of RFE and various ML models (SVM, etc.). | https://scikit-learn.org |

| COCONUT Database | Chemical Database | A large, open collection of natural products for benchmarking. | [26] |

| CMNPD Database | Chemical Database | Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database for bioactivity datasets. | [26] |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | ML Framework | Libraries for building and training complex models like 1D-CNNs. | N/A |

Molecular descriptors and fingerprints are indispensable tools for modern computational chemistry and drug discovery. The journey from a SMILES string to a quantitative fingerprint or descriptor vector enables the application of powerful machine learning algorithms. This Application Note has detailed the major categories of representations and provided explicit protocols for their generation and subsequent refinement through feature selection. The integration of RFE with 1D-CNNs presents a promising advanced protocol, leveraging the feature learning power of deep learning to identify the most parsimonious and predictive subset of molecular features. As the field progresses, the development of novel, more informative representations and robust, interpretable feature selection methods will continue to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of molecular property prediction.

A Step-by-Step Pipeline for Implementing RFE with 1D-CNN

In modern computational drug discovery, the translation of molecular structures into a computer-readable format, known as molecular representation, serves as the foundational step for training machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models [34]. Effective molecular representation bridges the gap between chemical structures and their biological, chemical, or physical properties, enabling various drug discovery tasks including virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping [34]. The process of standardizing these molecular descriptors and preparing high-quality input data is particularly critical when building advanced ML pipelines such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for molecular descriptor selection. This protocol outlines standardized procedures for preprocessing molecular data, with a specific focus on preparing optimized input for RFE-1D CNN architectures that identify the most predictive molecular descriptors for target properties.

Molecular Descriptors: Types and Calculations

Molecular descriptors are numerical values that encode various chemical, structural, or physicochemical properties of compounds, forming the basis for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) modeling [7]. These descriptors are generally classified according to dimensions which correspond to different levels of structural information and computational complexity [7].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors by Dimension

| Descriptor Type | Description | Examples | Calculation Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D Descriptors | Global molecular properties requiring only molecular formula | Molecular weight, atom count, logP | RDKit, Mordred, DOPtools [7] [35] |

| 2D Descriptors | Topological indices derived from molecular graph structure | Connectivity indices, Wiener index, graph-theoretical descriptors | RDKit, PaDEL, DOPtools [7] [35] |

| 3D Descriptors | Geometric features requiring molecular conformation | Molecular surface area, volume, 3D-MoRSE descriptors | DRAGON, RDKit, molecular modeling software [7] |

| 4D Descriptors | Conformational ensembles accounting for molecular flexibility | Conformer-dependent properties | Specialized molecular dynamics packages [7] |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | Electronic properties derived from quantum calculations | HOMO-LUMO gap, dipole moment, electrostatic potential surfaces | Quantum chemistry software (Gaussian, ORCA) [7] |

For RFE-1D CNN pipelines, the initial feature set typically comprises a combination of 1D, 2D, and occasionally 3D descriptors. The selection should be guided by the specific predictive task, with 1D and 2D descriptors often providing sufficient information for many QSAR modeling applications while maintaining computational efficiency [36].

Data Standardization and Preprocessing Protocols

Molecular Structure Standardization

Before descriptor calculation, molecular structures must be standardized to ensure consistency and reproducibility:

- Structure Input: Accept molecular structures in Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) format, which provides a compact and efficient way to encode chemical structures as strings [34].

- Standardization: Use chemical standardization tools to normalize representations, including:

- Aromatization and kekulization

- Neutralization of charges where appropriate

- Removal of counterions

- Tautomer standardization

- Stereochemistry normalization

- Validation: Check for and remove invalid structures, ensuring all molecules follow chemical validity rules.

Tools such as RDKit, Chython, and DOPtools provide functions for reading chemical structures in SMILES format and performing standardization [35].

Descriptor Standardization and Normalization

Once calculated, molecular descriptors require standardization to make them comparable and suitable for ML algorithms:

- Missing Value Handling:

- Remove descriptors with >15% missing values

- For descriptors with <15% missing values, apply appropriate imputation (median for skewed distributions, mean for normal distributions)

- Outlier Treatment:

- Identify outliers using Interquartile Range (IQR) method

- Cap extreme values at 1.5×IQR above the third quartile and below the first quartile

- Feature Scaling:

- Apply Z-score standardization to features with approximately normal distributions: ( X_{\text{standardized}} = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma} )

- Apply Min-Max scaling to bounded descriptors: ( X{\text{scaled}} = \frac{X - X{\text{min}}}{X{\text{max}} - X{\text{min}}} )

- Multicollinearity Reduction:

- Calculate pairwise correlation matrix between all descriptors

- Identify highly correlated descriptor pairs (|r| > 0.95)

- Remove one descriptor from each highly correlated pair, prioritizing retention of chemically interpretable descriptors [36]

Table 2: Standardization Methods for Different Descriptor Types

| Descriptor Category | Recommended Scaling | Missing Value Strategy | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Physicochemical | Z-score standardization | Median imputation | Check distribution normality first |

| Spectral & Topological | Min-Max scaling | Mean imputation | Often bounded ranges |

| Binary Fingerprints | No scaling required | N/A (typically complete) | Use as-is for feature importance |

| Count-Based Features | Max scaling | Zero imputation | Preserve sparsity |

| Quantum Chemical | Robust scaling | KNN imputation | Often contain outliers |

Workflow Integration with RFE-1D CNN Architecture

The preprocessed molecular descriptors serve as input to the RFE-1D CNN pipeline for feature selection. The integration involves specific data formatting and sequencing:

Input Tensor Preparation for 1D CNN

- Descriptor Ordering: Arrange standardized descriptors in a consistent order across all samples

- Tensor Reshaping: Format the descriptor vector as a 1D tensor with dimensions (nsamples, ndescriptors, 1) for compatibility with 1D CNN layers

- Training/Test Split: Perform stratified splitting (80/20 ratio) before any feature selection to prevent data leakage

- Batch Preparation: Create batches of size 32-128 for efficient training

Integrated RFE-1D CNN Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Selection

Systematic Descriptor Selection Method

Based on established feature selection methodologies for molecular data [36], implement the following protocol:

Initial Feature Pool Generation:

- Calculate all available 1D and 2D descriptors using RDKit or DOPtools

- Include a diverse set: constitutional, topological, geometrical, and physicochemical descriptors

- Initial pool should contain 500-2000 descriptors depending on dataset size

Multicollinearity Reduction:

- Compute Pearson correlation matrix for all descriptor pairs

- Identify correlated clusters with |r| > 0.95

- From each cluster, retain the descriptor with highest chemical interpretability and remove others

- Target 50-70% reduction in initial descriptor count

RFE-1D CNN Implementation:

- Configure 1D CNN with 3 convolutional layers (filters: 64, 32, 16; kernel size: 3)

- Add global average pooling and dense layer (32 units) before output

- Train model and extract feature importance using gradient-based attribution

- Eliminate bottom 10% of features each iteration

- Monitor validation performance to determine stopping point

Performance Validation Protocol

Evaluation Metrics:

- Track mean absolute error (MAE) or accuracy across RFE iterations

- Monitor feature set size reduction

- Assess model complexity and training time

Benchmarking:

- Compare against standard feature selection methods (Random Forest importance, LASSO)

- Validate on external test set not used during feature selection

- Perform statistical significance testing (paired t-test) on performance metrics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Application in RFE-1D CNN |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPtools [35] | Python library | Unified descriptor calculation and model optimization | Automated descriptor computation and hyperparameter optimization |

| RDKit [7] [35] | Cheminformatics library | Molecular representation and descriptor calculation | Primary tool for 1D/2D descriptor calculation and structure standardization |

| Scikit-learn [7] [35] | ML library | Data preprocessing and ML algorithms | Implementation of standardization, normalization, and baseline models |

| Mordred [35] | Descriptor calculator | Comprehensive descriptor calculation | Calculation of 1D/2D descriptors complementing RDKit features |

| Chython [35] | Chemical data processor | Structure standardization and validation | Molecular standardization before descriptor calculation |

| Optuna [35] | Optimization framework | Hyperparameter optimization | Optimization of 1D CNN architecture and training parameters |

Implementation Workflow for Descriptor Preprocessing