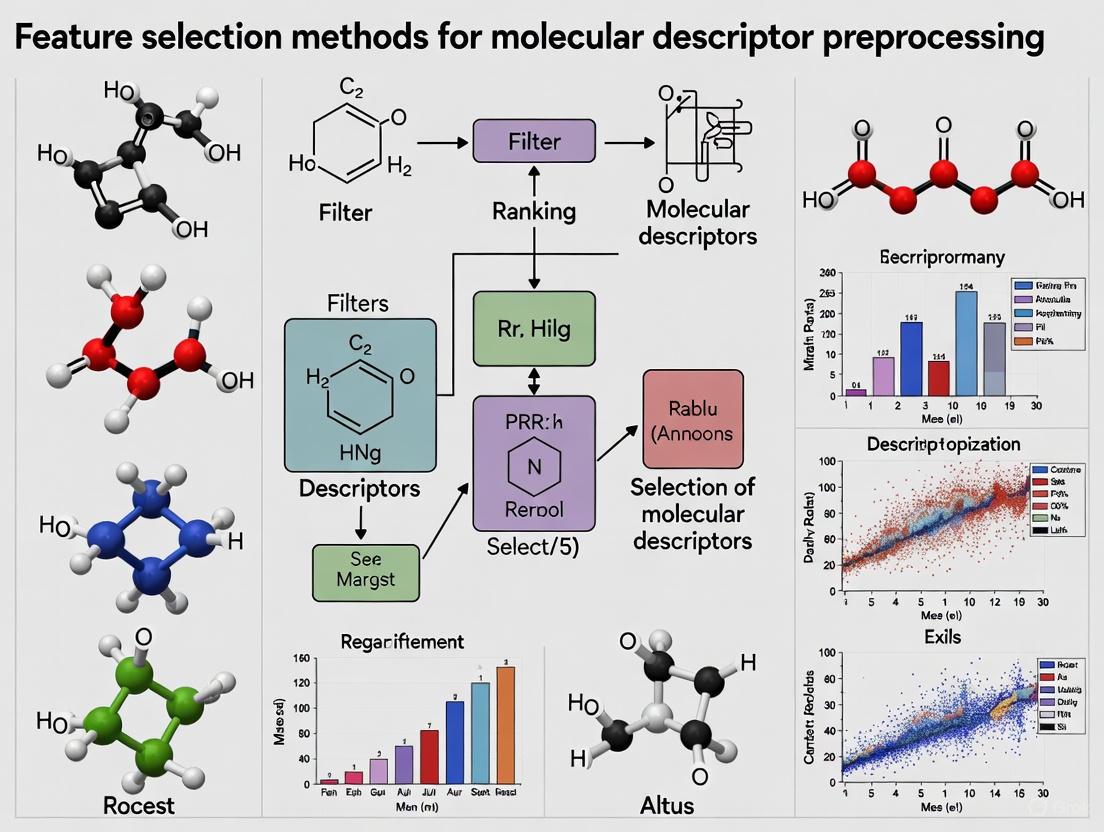

Optimizing Molecular Descriptors: A Comprehensive Guide to Feature Selection in Drug Discovery

This article provides a thorough analysis of feature selection methodologies for preprocessing molecular descriptors, a critical step in enhancing the efficiency and predictive accuracy of machine learning models in drug...

Optimizing Molecular Descriptors: A Comprehensive Guide to Feature Selection in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a thorough analysis of feature selection methodologies for preprocessing molecular descriptors, a critical step in enhancing the efficiency and predictive accuracy of machine learning models in drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of feature selection, details a wide array of techniques from traditional filters to advanced deep learning and differentiable methods, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing workflows. Furthermore, it presents a rigorous framework for the validation and benchmarking of feature selection performance, synthesizing recent benchmark studies to deliver actionable insights for building robust, interpretable, and high-performing predictive models in pharmaceutical research.

The Critical Role of Feature Selection in Molecular Data Analysis

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary challenge when using thousands of available molecular descriptors in QSAR modeling? Using all available molecular descriptors in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) modeling often leads to overfitting, reduced model interpretability, and consequently, diminished predictive performance. The high-dimensional and intensely correlated nature of these descriptors means a model might incorrectly identify a generic "bulk" property (like molecular weight) as highly predictive when it is merely a proxy for the true, specific pharmacophore feature causing the biological activity [1] [2].

Q2: How can feature selection methods address the high-dimensionality problem? Feature selection methods drastically reduce the number of molecular descriptors by selecting only those relevant to the property being predicted. This improves model performance and interpretability. A "two-stage" feature selection procedure, which uses a pre-processing filter method to select a subset of descriptors before building the final model (e.g., with C&RT), has been shown to yield higher accuracy compared to a "one-stage" approach that relies on the model's built-in selection alone [1].

Q3: My QSAR model is biased because my data set has many more highly absorbed compounds than poorly absorbed ones. How can I fix this? You can utilize misclassification costs during the model building process. Assigning a higher cost to misclassifying the minority class (e.g., poorly absorbed compounds) helps the model overcome the bias in the data set and leads to more accurate and reliable predictions [1].

Q4: How can I distinguish causally relevant molecular descriptors from merely correlated ones? Moving from correlational to causal QSAR requires a specialized statistical framework. One proposed method uses Double/Debiased Machine Learning (DML) to estimate the unconfounded causal effect of each descriptor on biological activity, treating all other descriptors as potential confounders. This is followed by high-dimensional hypothesis testing (e.g., the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure) to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR) and identify descriptors with statistically significant causal links [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Poor Model Generalization and Overfitting

- Symptoms: High accuracy on training data but poor performance on new, test data.

- Possible Cause: Overfitting due to the high-dimensional descriptor space and intense correlations between descriptors [2].

- Solution:

- Implement a rigorous "two-stage" feature selection process. First, use a pre-processing filter method (e.g., Random Forest predictor importance) to select a top subset of descriptors (e.g., top 20) [1].

- Then, use your primary modeling algorithm (e.g., C&RT) for the final selection and model building from this pre-filtered subset.

- Validate the model on a hold-out test set or via cross-validation.

Issue 2: Biased Model Due to Imbalanced Datasets

- Symptoms: The model predicts the majority class well but performs poorly on the minority class.

- Possible Cause: The dataset has a significant imbalance (e.g., more highly absorbed than poorly absorbed compounds) [1].

- Solution:

- During model training, incorporate misclassification costs.

- Assign a higher penalty for misclassifying examples from the underrepresented class. This forces the model to pay more attention to the minority class.

Issue 3: Models are Misled by Correlated "Proxy" Descriptors

- Symptoms: The model highlights "bulk" property descriptors (e.g., molecular weight) as important, misdirecting chemical synthesis efforts away from the true causal pharmacophore [2].

- Possible Cause: Standard machine learning models identify correlations but cannot disentangle causation from confounding.

- Solution:

- Apply a causal inference framework like Double Machine Learning (DML).

- Use DML to estimate the causal effect of each descriptor while adjusting for all other descriptors as confounders.

- Perform high-dimensional hypothesis testing on the causal estimates to control the False Discovery Rate and select only statistically significant causal descriptors.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Feature Selection for Improved C&RT Models

This protocol outlines a method to build more accurate and interpretable decision tree models for oral absorption prediction [1].

- Descriptor Calculation: Calculate a wide range of molecular descriptors for all compounds in the dataset.

- Pre-processing Feature Selection (Stage 1): Apply a filter-based feature selection method. The random forest predictor importance method has been shown to be effective. Select a top subset of descriptors (e.g., the top 20) from this stage.

- Model Building with Embedded Selection (Stage 2): Use the Classification and Regression Trees (C&RT) algorithm to build a decision tree. C&RT will perform a second, embedded feature selection, but now it chooses only from the pre-filtered, relevant subset of descriptors.

- Addressing Data Bias: If working with an imbalanced dataset, configure misclassification costs in the C&RT algorithm to penalize errors on the minority class more heavily.

- Validation: Evaluate the final model's accuracy on a separate validation set.

Protocol 2: Causal Descriptor Identification via Double Machine Learning

This protocol describes a framework to move from correlational to causal QSAR by deconfounding molecular descriptors [2].

- Data Preparation: Assemble a dataset of molecular descriptors (features) and biological activity (target).

- Causal Effect Estimation: For each molecular descriptor:

- Use Double Machine Learning (DML). This involves using machine learning models to predict both the target (biological activity) and the descriptor of interest from all other descriptors.

- The causal effect is estimated from the residuals of these predictions, effectively isolating the unconfounded effect of the descriptor.

- Hypothesis Testing: Apply the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to the p-values obtained from the causal estimates for all descriptors. This controls the False Discovery Rate (FDR) in this high-dimensional setting.

- Descriptor Selection: Identify the molecular descriptors with a statistically significant causal effect on the biological activity, as determined by the FDR threshold.

Table 1: WCAG Color Contrast Requirements for Data Visualization This table summarizes the minimum contrast ratios required for text accessibility, which should be applied to all diagrams and visualizations to ensure readability [3] [4].

| Text Type | Level AA (Minimum) | Level AAA (Enhanced) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Text | 4.5:1 | 7:1 |

| Large Scale Text (approx. 18pt+) | 3:1 | 4.5:1 |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments This table details essential computational tools and methodologies used in feature selection research.

| Item/Reagent | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| C&RT (Classification and Regression Trees) | A decision tree algorithm with embedded feature selection; used for building interpretable QSAR models [1]. |

| Random Forest Predictor Importance | A filter-based pre-processing method used to rank and select the most relevant molecular descriptors before final model building [1]. |

| Double Machine Learning (DML) | A causal inference method used to estimate the unconfounded effect of a molecular descriptor on biological activity, adjusting for all other descriptors as confounders [2]. |

| Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure | A statistical method for controlling the False Discovery Rate (FDR) during high-dimensional hypothesis testing on causal descriptor estimates [2]. |

| Misclassification Costs | A model parameter used to assign a higher penalty for misclassifying compounds from an underrepresented class, mitigating bias from imbalanced datasets [1]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Two-Stage Feature Selection Workflow

Causal QSAR Analysis with DML

Problem-Shooting Decision Tree

In molecular descriptor preprocessing for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling, feature selection is not merely a preliminary step but a fundamental component for building robust and interpretable predictive models. The process of selecting the most relevant molecular descriptors from thousands of calculated possibilities is crucial for combating overfitting, improving model performance, and enhancing scientific interpretability [1] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this translates to more reliable predictions of biological activity, toxicity, or other molecular properties, ultimately streamlining the drug discovery pipeline [5].

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and detailed methodologies to help you effectively implement feature selection in your QSAR research.

Troubleshooting Common Feature Selection Issues

Q1: My QSAR model performs excellently on training data but poorly on validation data. What is the cause and how can I resolve it?

This is a classic symptom of overfitting, where your model has learned noise and spurious correlations from the training set instead of the underlying structure-activity relationship [6] [7].

- Primary Cause: The model is too complex for the amount and quality of training data, often due to an excessive number of molecular descriptors, many of which may be irrelevant or redundant [6] [8].

- Solutions:

- Implement Pre-Processing Feature Selection: Before training your model, use a filter method to reduce the descriptor set. A study on oral absorption models found that a two-stage approach—using a filter method first, followed by a algorithm like C&RT—yielded higher accuracy than using the algorithm alone [1].

- Apply Regularization: Use embedded methods like Lasso (L1 regularization), which penalizes the absolute size of coefficients and can drive the coefficients of irrelevant descriptors to zero, effectively removing them [9] [7].

- Use Validation for Selection: Ensure you do not use your test set to guide feature selection. Instead, perform feature selection within each fold of cross-validation on the training data to prevent information leakage and over-optimistic results [7].

Q2: After feature selection, my model is less interpretable to non-data scientist stakeholders. How can I improve this?

Interpretability is key for gaining trust and actionable insights in drug development.

- Primary Cause: The selected features (molecular descriptors) may not have clear chemical or biological meanings, or the selection process itself is a "black box" [10].

- Solutions:

- Prioritize Filter Methods: Methods based on correlation or univariate statistical tests are often easier to explain than complex wrapper methods [11] [12]. You can directly report that descriptors were selected based on their strong statistical relationship with the target activity.

- Leverage Domain Knowledge: After an automated selection process, have a domain expert review the shortlisted descriptors. This hybrid approach ensures the selected features are not only statistically sound but also chemically plausible [5] [7].

- Use Tree-Based Models: Tree-based algorithms like C&RT provide a clear hierarchy of descriptor importance, which is inherently interpretable [1] [9].

Q3: How do I choose the right feature selection method for my specific QSAR problem?

The choice depends on your data size, computational resources, and model goals [11] [13].

- For Large Datasets (1000s of descriptors): Start with fast Filter Methods (e.g., Correlation, Variance Threshold) to quickly reduce dimensionality [11] [12].

- For High-Performance Models: If computational cost is less of a concern, Wrapper Methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) can often find a better-performing subset of descriptors by evaluating different combinations against a specific model [9] [11].

- For a Balanced Approach: Embedded Methods (e.g., Lasso, Tree-based feature importance) integrate selection with model training, offering a good compromise between performance and efficiency [9] [11] [13].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these method types.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Method Types

| Method Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Selects features based on statistical measures of correlation/variance with the target, independent of any model [11] [13]. | Fast, computationally efficient, model-agnostic, good for initial dimensionality reduction [11] [12]. | Ignores feature interactions, may select redundant features [11]. | Correlation coefficients, Chi-Square test, Variance Threshold [9] [12]. |

| Wrapper Methods | Uses the performance of a specific predictive model to evaluate and select the best feature subset [11] [13]. | Model-specific, can capture feature interactions, often results in high predictive accuracy [11]. | Computationally expensive, high risk of overfitting if not validated properly [11] [7]. | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), Forward/Backward Selection [9] [12]. |

| Embedded Methods | Performs feature selection as an integral part of the model training process [11] [13]. | Efficient, model-specific, less prone to overfitting than wrapper methods [11]. | Limited to specific algorithms, can be less interpretable [11]. | L1 (Lasso) regularization, Tree-based feature importance [9] [13]. |

Featured Experimental Protocol: Representative Feature Selection (RFS) for QSAR

The following protocol is adapted from a study on selecting molecular descriptors for predicting molecular odor labels, demonstrating a robust approach to managing high-dimensional chemical data [5].

Objective: To select a representative subset of molecular descriptors from a large pool (e.g., 5270 descriptors calculated by Dragon software) to build a interpretable and high-performance QSAR model [5].

Workflow Overview: The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the RFS protocol.

Materials & Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RFS Protocol

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dataset | A set of chemical compounds with known biological activity or property. | e.g., 907 odorous molecules from a database like PubChem [5]. |

| Descriptor Calculation Software | Computes numerical representations of molecular structures. | Dragon 7.0 is a standard tool for calculating >5000 molecular descriptors [5]. |

| Clustering Algorithm | Groups descriptors based on similarity to identify redundancy. | Affinity Propagation was used in the original RFS study [5]. K-Means is a viable alternative. |

| Statistical Software | Provides environment for data preprocessing, correlation analysis, and model building. | Python with libraries like scikit-learn, pandas, and numpy [9] [12]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Preprocessing:

- Data Cleaning: Handle missing values, for example, by removing molecular descriptors with a high percentage of missing values across the compound set.

- Normalization: Standardize the range of descriptor values to ensure they are on a comparable scale (e.g., StandardScaler in scikit-learn) [5].

Preliminary Screening:

- Apply a Variance Threshold to remove all molecular descriptors with zero or very low variance (e.g., features that are constant or almost constant across all molecules), as they contain little to no information for discrimination [9] [12]. In the RFS study, this step reduced the descriptor pool from 5270 to 1850 [5].

Descriptor Clustering:

- Cluster the remaining descriptors using an algorithm like Affinity Propagation or K-Means. The goal is to group descriptors that are highly correlated and thus convey similar information about the molecules [5].

Intra-Cluster Selection:

- From each cluster, select a single representative descriptor. The choice can be based on the highest mean correlation with other descriptors in the cluster or the highest variance [5].

Correlation Analysis (RFS Core):

- Perform a final filter by calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient between all pairs of the representative descriptors.

- Define a strong correlation threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.8). Between any two descriptors that are strongly correlated, remove the one that has a lower correlation with the target variable (the biological activity you are predicting) [5]. The original study found that 92.7% of descriptor pairs had a Pearson coefficient with an absolute value below 0.8, indicating high redundancy in the original space [5].

Expected Outcome: The protocol outputs a minimized set of molecular descriptors with low redundancy, which can be used to train a QSAR model with reduced overfitting risk and improved interpretability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Should I perform feature selection before or after feature scaling? A: Feature selection should be performed before feature scaling. This reduces the computational effort required for scaling, as you will only scale the features that have been selected as relevant [10].

Q: What is the difference between feature selection and feature extraction? A: Feature selection chooses a subset of the original features, preserving their intrinsic meaning (e.g., selecting 100 from 5000 molecular descriptors). Feature extraction creates new, transformed features from the original set (e.g., using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Autoencoders), which are often less interpretable [5] [10].

Q: How can I identify if overfitting has occurred during feature selection? A: A key indicator is a significant performance drop between your training and test/validation datasets [7]. To detect this, always use a held-out test set that is not used during the feature selection process. Techniques like cross-validation during model training can also help identify overfitting [7].

Q: Are there automated tools for feature selection in QSAR modeling?

A: Yes, many programming libraries offer robust feature selection modules. The Python scikit-learn library is a prime example, providing various feature selection classes like SelectKBest, RFE, and SelectFromModel [9] [12]. These can be integrated into a QSAR modeling pipeline for efficient workflow.

Feature selection is a critical preprocessing step in building machine learning models for drug discovery. It involves identifying the most relevant variables in a dataset to improve model accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency while reducing the risk of overfitting [14] [15]. In the context of molecular descriptor preprocessing, where thousands of descriptors can be calculated to represent chemical compounds, feature selection helps researchers focus on the molecular characteristics most predictive of a target biological property or activity [16] [17] [1].

This guide outlines the three core categories of feature selection methods—Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded approaches—providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols tailored for researchers and drug development professionals working with molecular data.

The Three Core Methodologies

Filter Methods

Concept: Filter methods rank features based on statistical relationships with the target variable, independently of any machine learning model [14] [15]. They are model-agnostic and operate by filtering out irrelevant or redundant features before the model training process begins.

When to Use: Filter methods are ideal for an initial, computationally cheap preprocessing step to quickly reduce a very high-dimensional feature space, such as when working with thousands of molecular descriptors [14] [18].

Common Techniques & Molecular Applications:

- Correlation Coefficient: Measures linear relationships; useful for initial descriptor screening [14] [18].

- Chi-Square Test: Assesses dependence between categorical features and the target [14].

- Mutual Information: Measures the amount of information a feature shares with the target, capable of detecting non-linear relationships [14] [15].

- Variance Threshold: Removes descriptors with near-zero variance, which offer little discriminative power [14] [18].

Experimental Protocol for Filter-Based Preprocessing:

- Compute Descriptors: Use software like Dragon [16] or PaDEL [18] to generate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors.

- Remove Low-Variance Features: Apply a variance threshold to eliminate constants and near-constant descriptors.

- Handle Redundancy: Calculate the correlation matrix between all remaining descriptors. Remove one of any pair of descriptors with a correlation coefficient exceeding a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.95) to mitigate multicollinearity [18].

- Rank by Relevance: Use a statistical measure (e.g., Correlation, Chi-Square, Mutual Information) to rank the filtered descriptors by their relationship to the target variable (e.g., biological activity) [14].

- Select Top-k Features: Choose the top k ranked descriptors for model training, or use the ranked list as input for a subsequent wrapper or embedded method [1].

Wrapper Methods

Concept: Wrapper methods evaluate different feature subsets by iteratively training and testing a specific machine learning model. They "wrap" the feature selection process around a predictive model, using its performance as the evaluation criterion for a feature subset [14] [15].

When to Use: Employ wrapper methods when predictive accuracy is the primary goal, computational resources are sufficient, and the dataset is not excessively large. They are suitable after an initial filter step has reduced the feature space dimensionality [14].

Common Techniques & Molecular Applications:

- Forward Selection: Starts with no features and adds one feature at a time that most improves model performance [14].

- Backward Elimination: Starts with all features and removes the least important feature at each iteration [14].

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Recursively removes the least important features (e.g., based on model coefficients) and re-trains the model until the desired number of features is reached [14] [19].

Experimental Protocol for Wrapper-Based Selection:

- Pre-filtering (Recommended): Use a filter method to reduce the number of descriptors to a manageable size (e.g., 100-200) to lower the computational cost of the wrapper search [1].

- Choose a Search Strategy: Select a search algorithm such as Forward Selection, Backward Elimination, or RFE.

- Select a Predictive Model: Choose a classifier/regressor (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) to evaluate subsets.

- Define an Evaluation Metric: Choose a performance metric (e.g., Accuracy, AUC-ROC for classification; R² for regression) to guide the search.

- Perform the Search: Use cross-validation on the training set to evaluate the performance of each candidate feature subset. The subset achieving the best average validation score is selected.

Embedded Methods

Concept: Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training algorithm. The model itself determines which features are most important during the training phase [14] [19] [15].

When to Use: These methods offer a good balance between the computational efficiency of filters and the performance focus of wrappers. They are ideal when you want to combine model training and feature selection in a single step [14] [19].

Common Techniques & Molecular Applications:

- LASSO (L1 Regularization): Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the magnitude of coefficients. This can force some coefficients to be exactly zero, effectively removing those features from the model [19] [15].

- Tree-Based Methods: Algorithms like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost) provide intrinsic feature importance scores based on metrics like Gini impurity reduction or mean decrease in accuracy [19] [15].

- Elastic Net: Combines L1 (Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) regularization, which can be more effective than Lasso when features are highly correlated [19] [15].

Experimental Protocol for Embedded Selection:

- Select an Embedded Algorithm: Choose a model with built-in feature selection capabilities, such as Lasso, Random Forest, or XGBoost.

- Train the Model: Fit the model to the training data. The algorithm will inherently perform feature selection.

- Extract Feature Importance:

- Select Features: Choose features based on the derived importance (e.g., non-zero coefficients from Lasso, or top-k features from importance scores).

Comparative Analysis & Decision Guide

Method Comparison Table

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three feature selection categories to guide your method selection.

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | Selects features based on statistical scores, independent of a model [14]. | Uses a model's performance to evaluate and select feature subsets [14]. | Feature selection is embedded into the model training process [19]. |

| Computational Cost | Low [14] [19]. | Very High [14] [19]. | Moderate (similar to model training) [19]. |

| Model Specificity | No, model-agnostic [14]. | Yes, specific to the chosen learner [14]. | Yes, specific to the algorithm [14]. |

| Considers Feature Interactions | No, typically evaluates features individually [14]. | Yes [14]. | Yes [19]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low. | High, if not properly cross-validated [14]. | Moderate. |

| Primary Advantage | Fast and scalable; good for initial analysis. | Often provides high-performing feature sets. | Balances performance and efficiency. |

| Key Limitation | Ignores feature dependencies and interaction with the model. | Computationally expensive; prone to overfitting [14]. | Tied to the specific learning algorithm. |

Hybrid and Advanced Strategies

For complex problems, combining methods can yield superior results:

- Filter + Wrapper: Use a filter method for an initial aggressive reduction of the feature space, then apply a wrapper method on the remaining features to refine the selection [16] [18]. This was shown to improve prediction accuracy for oral absorption models [1].

- Hybrid View-Based Selection: In one study on opioid receptor ligands, researchers used a hybrid approach that combined feature sets from different "views" (fingerprints, ligand descriptors, and molecular interaction features), leading to an improved ROC AUC [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

This table lists key computational tools and resources used in feature selection experiments for molecular descriptor analysis.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dragon | Software | Calculates thousands of molecular descriptors (0D-3D) from chemical structures. | [16] |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Open-source software to compute molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | [18] |

| WEKA | Software | A workbench containing a collection of machine learning algorithms and feature selection techniques. | [16] |

| Scikit-learn | Library | Python library providing implementations of Filter, Wrapper (e.g., RFE), and Embedded (e.g., Lasso) methods. | [14] [19] |

| CHEMBL | Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | [17] |

| DrugBank | Database | A comprehensive database containing drug and drug target information. | [17] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: I have a very large set of molecular descriptors. Which feature selection method should I start with? A: Begin with a Filter method. Its low computational cost makes it ideal for a first pass to quickly eliminate irrelevant and redundant features. You can then apply a more sophisticated Wrapper or Embedded method on the reduced subset for finer selection [14] [1].

Q2: My wrapper method is taking too long to run. What can I do? A: This is a common issue. Consider these steps:

- Pre-filtering: Drastically reduce the number of features using a fast filter method before applying the wrapper [1].

- Use a Faster Model: Use a less computationally intensive model (e.g., Logistic Regression instead of SVM) within the wrapper for the search process.

- Limit Search Space: Use a less exhaustive search strategy (e.g., Forward/Backward selection instead of an exhaustive search).

Q3: How can I prevent my feature selection process from overfitting? A:

- Strict Validation: Always perform the feature selection process within each fold of cross-validation on the training data only. Never use the test set to guide feature selection, as this will optimistically bias your results [21].

- Regularization: Use Embedded methods like Lasso that include built-in regularization to prevent overfitting [19] [15].

- Independent Test Set: Always hold out a final, independent test set to evaluate the generalizability of your model built with the selected features.

Q4: My model is complex and doesn't provide built-in feature importance. How can I select features? A: You can use Wrapper methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). RFE can use any model's predictions; it works by recursively removing the least important features (determined by model coefficients or other metrics) and re-training until the desired number of features is selected [14] [19].

Q5: Are there methods that combine the strengths of different feature selection approaches? A: Yes, hybrid methods are increasingly popular. A common and effective strategy is the "two-stage" selection: first using a Filter method to reduce dimensionality, followed by a Wrapper or Embedded method to make the final selection from the top-ranked features [16] [1] [18]. This balances speed and performance.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Error:ValueError: No feature in X meets the variance threshold

Q: I applied VarianceThreshold and received a ValueError stating no features meet the threshold. What went wrong and how can I resolve this?

A: This error occurs when your threshold is set too high, causing all features to be removed. To resolve this:

- Diagnose feature variances: Before applying the threshold, examine the variances of all features using the

variances_attribute after fitting the selector [22]. - Lower the threshold: Start with a conservative threshold, such as the default of

0.0(which removes only zero-variance features), and gradually increase it [22] [23]. - Check data scaling: If features are on different scales, variances are not directly comparable. Apply feature scaling (e.g.,

StandardScaler) after variance thresholding, as scaling can artificially alter variances [23].

Common Error: Handling Missing Data in Molecular Descriptor Sets

Q: After calculating thousands of molecular descriptors, many contain missing values (NaN). Should I use listwise deletion or imputation?

A: Listwise deletion (removing any compound with a missing value) is a common but often suboptimal approach. It can introduce significant bias, especially if the data is not Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) [24] [25]. A more robust protocol is:

- Identify and Remove: First, remove descriptors with a very high percentage (e.g., >80%) of missing values, as they provide little information [26].

- Impute Remaining Gaps: For descriptors with sporadic missing values, use model-based imputation (like

KNNImputer) to estimate the missing values based on other available descriptors [27]. This preserves your sample size and reduces bias.

Common Issue: Optimizing the Variance Threshold Parameter

Q: How do I select an optimal threshold value for VarianceThreshold? Is there a systematic way to choose it?

A: The optimal threshold is dataset-dependent and should be treated as a hyperparameter.

- Start with a Baseline: Use the default

threshold=0.0to remove only constant features [22]. - Use Cross-Validation: Incorporate

VarianceThresholdinto a machine learning pipeline and use cross-validation to evaluate different threshold values against your model's performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score) [23]. - Analyze the Impact: Plot the number of retained features and the corresponding model performance for a range of thresholds. The goal is to find the threshold that maximizes performance with the minimal number of features.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing and Feature Selection

The following workflow, adapted from a study on drug-induced liver toxicity prediction, details a robust pipeline for preprocessing molecular descriptors [26].

1. Compute Molecular Descriptors:

- Objective: Quantitatively represent molecular structures.

- Action: Calculate multiple descriptor sets (e.g., PaDEL, RDKit, Chemopy) from compound SMILES strings using an integrated platform like ChemDes [26]. The study in [26] generated 2,648 initial descriptors.

2. Data Cleaning:

- Objective: Remove non-informative features.

- Action: Apply

VarianceThreshold(threshold=0.0)to eliminate descriptors with zero variance (the same value across all samples) [22] [26].

3. Handle Missing Data:

- Objective: Address missing values without discarding entire compounds.

- Action: Remove descriptors with a high fraction of missing values. For the remaining, use imputation methods. The referenced study used a filter-based approach to drop features with missing values [26].

4. Remove Redundant Features:

- Objective: Reduce multicollinearity.

- Action: Calculate pairwise Pearson correlations between all descriptors. For any pair with a correlation coefficient > 0.9, remove one of the descriptors [26].

5. Feature Selection:

- Objective: Identify the most relevant feature subset.

- Action: Use a combination of filter and wrapper methods [26]:

6. Model Building & Validation:

- Objective: Construct a predictive model.

- Action: Train a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine) using the selected features and validate performance with 10-fold cross-validation and an external test set [26].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Descriptor Preprocessing

| Tool Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Application in Preprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor [26] [28] | Software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. | Generates quantitative numerical representations (features) from compound SMILES or SDF files. |

| RDKit [29] [26] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | An alternative for calculating molecular descriptors and standardizing chemical structures. |

| Scikit-learn VarianceThreshold [22] [9] | Feature selector that removes low-variance features. | Used in the initial cleaning phase to eliminate constant and near-constant descriptors. |

| Scikit-learn RFECV [26] [9] | Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation. | A wrapper method to identify the optimal subset of features by recursively pruning the least important ones. |

| ChemDes [26] | Online platform that integrates multiple descriptor calculation packages. | Streamlines the computation of descriptors from PaDEL, RDKit, CDK, and Chemopy from a single interface. |

| KNN Imputer | An imputation algorithm that estimates missing values using values from nearest neighbors. | Handles missing data in the descriptor matrix by leveraging patterns in the available data [27]. |

A Practical Guide to Feature Selection Techniques and Their Implementation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are filter methods, and why should I use them for selecting molecular descriptors in QSAR studies?

Filter methods are feature selection techniques that evaluate and select molecular descriptors based on their intrinsic statistical properties, independent of any machine learning model [30] [31]. They are a crucial preprocessing step in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling. You should use them because they are computationally efficient, scalable for high-dimensional data (like the thousands of descriptors calculated by software such as Dragon), and help in building simpler, more interpretable models by removing irrelevant or redundant features [5] [32] [31]. This can prevent overfitting and improve the generalizability of your QSAR model, which is essential for reliable virtual screening in drug discovery [30] [16].

2. How do I choose the right filter method for my dataset containing both continuous and categorical molecular descriptors?

The choice of filter method depends on the data types of your features (molecular descriptors) and your target variable (e.g., biological activity). The table below provides a clear guideline:

| Filter Method | Feature Type | Target Variable Type | Can Capture Non-Linear Relationships? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation [33] [31] | Continuous | Continuous | No |

| F-Score (ANOVA) [33] [31] | Continuous | Categorical | No |

| Mutual Information [34] [31] | Any | Any | Yes |

| Chi-Squared Test [32] [31] | Categorical | Categorical | No |

| Variance Threshold [34] [31] | Any | Any (Unsupervised) | No |

For example, use Mutual Information for a regression task with non-linear relationships, or the F-Test for a classification task with continuous descriptors [33] [31].

3. I've applied a correlation filter, but my model performance did not improve. What could be wrong?

A common pitfall is that basic correlation filters (like Pearson) are univariate, meaning they evaluate each feature in isolation [31]. They might remove features that are weakly correlated with the target on their own but become highly predictive when combined with others [30] [31]. Furthermore, you might be dealing with multicollinearity, where several descriptors are highly correlated with each other, providing redundant information [34] [32]. While you may have removed some, the remaining correlated features can still destabilize your model. Consider using a method that accounts for feature interactions or applying a multicollinearity check (e.g., Variance Inflation Factor) after the initial filter [30].

4. What is a reasonable threshold for the Variance Threshold method?

There is no universal value; it is data-dependent. A good start is to set a threshold of zero to remove only constants features [34] [33]. For quasi-constant features (e.g., where 99.9% of the values are the same), you can set a very low threshold like 0.001 [33]. You should experiment with different thresholds and evaluate the impact on your model's performance. Remember, an overly aggressive threshold might remove informative but low-variance descriptors that are specific to a certain molecular class [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling High Correlation and Multicollinearity Among Molecular Descriptors

Problem: Your dataset contains many highly correlated molecular descriptors, leading to redundant information and potential model instability.

Solution Steps:

Calculate the Correlation Matrix: Compute the Pearson or Spearman correlation matrix for all your molecular descriptors.

Identify Highly Correlated Pairs: Identify descriptor pairs with a correlation coefficient absolute value above a chosen threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.8 or 0.9) [5].

Remove Redundant Features: For each highly correlated pair, remove one of the descriptors. A good strategy is to keep the one with the higher correlation to your target variable [34].

Issue 2: Optimizing the Number of Features to Select (the 'k' in SelectKBest)

Problem: You are unsure how many top features (k) to select when using methods like SelectKBest.

Solution Steps:

Use a Score Plot: Calculate the scores for all features using your chosen filter method (e.g., F-test, Mutual Information) and plot them in descending order. Look for an "elbow" point where the score drop becomes less significant.

Performance-based Cross-Validation: Use cross-validation to evaluate your model's performance with different numbers of selected features. Choose the

kthat gives the best and most stable performance.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Benchmarking Filter Methods for Antimicrobial Peptide Classification

This protocol is adapted from research on the optimal selection of molecular descriptors for classifying Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) [35].

1. Objective: To compare the efficacy of different filter methods in selecting a subset of molecular descriptors that maximize the performance of an AMP classifier.

2. Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

| Item / Software | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Dragon Software [5] [16] | Calculates a wide array (e.g., 5000+) of molecular descriptors from peptide structures. |

| Benchmark AMP Datasets [35] | Provides standardized data for training and testing; e.g., datasets with known AMPs and non-AMPs. |

| Scikit-learn Library [33] [36] | Provides implementations for filter methods (VarianceThreshold, SelectKBest, fclassif, mutualinfo_classif) and model evaluation. |

| Random Forest Classifier [16] | A robust model used to evaluate the predictive performance of the selected descriptor subsets. |

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Compute molecular descriptors for all peptides in the benchmark dataset using Dragon. Perform standard preprocessing: remove constant descriptors, handle missing values, and normalize the data [5] [35].

- Step 2: Apply Filter Methods. Apply multiple filter methods independently to rank all molecular descriptors:

- Variance Threshold: Remove descriptors with near-zero variance.

- F-Test (ANOVA): Rank descriptors by their ability to separate AMP and non-AMP classes.

- Mutual Information: Rank descriptors by their non-linear dependency with the target class.

- Step 3: Subset Selection. For each filter method, select the top k descriptors, where k is varied (e.g., 10, 20, ..., 100) to analyze the impact of subset size.

- Step 4: Model Training & Evaluation. Train a Random Forest classifier on each subset of descriptors using 5-fold cross-validation. Record performance metrics like Accuracy and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC).

- Step 5: Analysis. Compare the performance metrics across different filter methods and subset sizes to identify the most effective technique.

4. Expected Results (Quantitative Data): The following table summarizes typical performance outcomes when different filter methods are applied to an AMP classification task [35]:

| Filter Method | Number of Descriptors Selected | Average Cross-Validation Accuracy (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Descriptors | 5270 | 85.2 | 0.92 |

| Variance Threshold | 1850 | 86.5 | 0.93 |

| F-Test (ANOVA) | 50 | 90.1 | 0.96 |

| Mutual Information | 50 | 91.5 | 0.97 |

Note: The data in this table is illustrative, based on findings from similar studies [5] [35]. Actual results will vary depending on the specific dataset and parameters.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Filter Method Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision workflow for selecting and applying an appropriate filter method to a QSAR dataset, incorporating troubleshooting checkpoints.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing wrapper methods for feature selection in molecular descriptor preprocessing.

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between RFE and Sequential Feature Selection, and when should I choose one over the other?

Answer: The core difference lies in their selection philosophy. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a backward elimination method. It starts with all features, trains a model, and recursively removes the least important feature(s) based on model-specific weights (like

coef_orfeature_importances_) [37] [9] [38]. In contrast, Sequential Feature Selection (SFS) is a greedy search algorithm that can work in either a forward (starting with no features) or backward (starting with all features) direction. It selects features based on a user-defined performance metric (e.g., accuracy, ROC AUC) rather than model-internal weights [39] [9] [40].The choice depends on your goal:

- Choose RFE when you want to leverage your model's inherent feature importance calculation and your dataset has a large number of features. It is computationally more efficient for high-dimensional spaces [38] [41].

- Choose SFS when your primary goal is to optimize a specific performance metric directly, or when using a model that doesn't provide reliable importance scores [40].

FAQ 2: Why does my RFE process select different features when I run it multiple times, and how can I stabilize it?

- Answer: Inconsistent feature selection with RFE is often caused by multicollinearity among molecular descriptors [38]. When multiple features are highly correlated and predictive, the model may arbitrarily choose one over another in different runs, as their importance scores become diluted [38]. To stabilize RFE:

- Apply a Correlation Filter: Before RFE, preprocess your data to remove highly correlated features. A common practice is to set a pairwise correlation threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.8) and keep only one feature from each correlated group [38].

- Use a Stable Estimator: Ensure the base estimator (like a linear model with L1 penalty or a well-tuned random forest) is appropriate for your data and has consistent output.

- Set a Random State: Always set the

random_stateparameter in your model and RFE function to ensure reproducible results [37].

FAQ 3: How do I determine the optimal number of features to select?

- Answer: Manually setting the number of features (

n_features_to_select) can be suboptimal. The best practice is to use the cross-validated versions of these algorithms to automatically find the optimal number.- For RFE, use

RFECVfrom scikit-learn. It performs RFE in a cross-validation loop and selects the number of features that maximize the cross-validation score [9]. - For Sequential Feature Selection, you can implement a custom cross-validation loop. You fit the selector for a range of feature subset sizes and plot the performance against the number of features, selecting the number where performance peaks [37]. The

tolparameter in scikit-learn'sSequentialFeatureSelectorcan also be used to stop when the score improvement falls below a threshold [42].

- For RFE, use

FAQ 4: My model's performance decreased after applying a wrapper method for feature selection. What went wrong?

- Answer: A performance drop can occur due to several reasons:

- Overfitting with Too Few Features: If the selection process is overly aggressive, it might remove features that are important for generalizing to new data. Always validate the final model on a held-out test set [37].

- Ignoring Model Assumptions: If you use a model like Logistic Regression or SVM without proper feature scaling, the importance rankings and selection process can be unreliable. Always preprocess your data according to the model's requirements (e.g., standardization) [37].

- Data Leakage: If you perform feature selection on the entire dataset before splitting into training and test sets, information from the test set leaks into the training process. Always perform feature selection within the cross-validation folds or as part of a

Pipeline[41].

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

The following table summarizes the core quantitative metrics and configurations you should track when comparing wrapper methods in your experiments. This is essential for reproducible research in QSAR modeling.

Table 1: Key Metrics and Configurations for Wrapper Method Experiments

| Aspect | RFE | Sequential Forward Selection (SFS) | Sequential Backward Selection (SBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Selection Criterion | Model-derived feature importance (e.g., coef_, feature_importances_) [9] [41] |

Performance metric (e.g., accuracy, AUC) [39] [40] | Performance metric (e.g., accuracy, AUC) [39] [40] |

| Starting Point | All features [37] [9] | No features [39] [40] | All features [39] [40] |

| Computational Load | Generally lower for high-dimensional data [38] | Higher for selecting a small subset from many features [9] | Higher for removing a small subset from many features [9] |

| Handling of Feature Interactions | Depends on the base estimator (e.g., tree-based models can capture interactions) | Explicitly evaluates feature combinations, can detect interactions [39] | Explicitly evaluates feature combinations, can detect interactions [39] |

Detailed Protocol: Implementing RFE with Cross-Validation

This protocol is tailored for a classification task, such as predicting a molecular property like blood-brain barrier penetration [16].

Data Preparation & Preprocessing:

- Load your dataset of compounds and their molecular descriptors [39] [16].

- Split the data into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20). The test set must be set aside and not used in any feature selection or model tuning.

- Perform necessary preprocessing (e.g., handling missing values, standardizing features) on the training set. Apply the fitted preprocessor to the test set.

Model and RFECV Setup:

Fitting and Evaluation:

- Fit the

RFECVselector on the training data. - After fitting, you can find the optimal number of features (

rfecv.n_features_) and the mask of selected features (rfecv.support_). - Transform your training and test sets to include only the selected features.

- Train your final model on the selected features from the training set and evaluate its performance on the preprocessed test set.

- Fit the

Detailed Protocol: Implementing Sequential Forward Selection

This protocol uses mlxtend for greater control over the selection process [39] [40].

Data Preparation: Follow the same data splitting and preprocessing steps as in the RFE protocol.

SequentialFeatureSelector Setup:

- Import the

SequentialFeatureSelector. - Define the estimator, the number of features to select, the direction (

forward=True), and the scoring metric. - To ensure robustness, use cross-validation within the selector (

cv=5).

- Import the

Fitting and Analysis:

- Fit the SFS on the training data.

- Analyze the results. You can inspect the

sfs.subsets_attribute to see the performance at each step and identify the best feature subset. - Use the

sfs.k_feature_idx_to get the indices of the selected features and then transform your datasets accordingly for final model training and testing.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for choosing and implementing a wrapper method, from data preparation to model evaluation.

Wrapper Method Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential software "reagents" required to implement the feature selection methods discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Feature Selection Research

| Tool / Library | Function / Purpose | Key Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn [42] [9] | A comprehensive machine learning library for Python. | Provides the RFE, RFECV, and SequentialFeatureSelector classes, along with models, preprocessing, and cross-validation utilities. |

| MLxtend [39] [40] | A library of additional helper functions and extensions for data science. | Provides an alternative implementation of SequentialFeatureSelector that includes floating selection methods (SFFS, SBFS). |

| Pandas [39] [37] | A fast, powerful, and flexible data analysis and manipulation library. | Used for loading, handling, and manipulating the dataset of molecular descriptors before and after feature selection. |

| NumPy [41] | The fundamental package for scientific computing in Python. | Provides support for large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, essential for the numerical operations in the models. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are embedded feature selection methods and how do they differ from other techniques? Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training phase. They "embed" the search for an optimal subset of features within the training of the classifier or regression algorithm [19]. This contrasts with:

- Filter Methods: Model-agnostic techniques that select features based on general data characteristics (e.g., correlation, chi-square test) independently of the machine learning model [19] [43].

- Wrapper Methods: Algorithms that "wrap" around a predictive model, evaluating multiple feature subsets through iterative training and performance checking (e.g., forward selection, backward elimination) [19]. Embedded methods often provide a good balance, offering a lower computational cost than wrapper methods while being more tailored to the model than filter methods [19].

2. Why are tree-based algorithms like Random Forest particularly well-suited for feature selection in molecular data? Tree-based algorithms are highly suitable for molecular data due to several inherent advantages:

- High-Dimensional Data Handling: They perform robustly with datasets where the number of features (e.g., genes, molecular descriptors) is much larger than the number of samples, a common scenario in biological and chemical data [43] [44] [45].

- Resistance to Overfitting: Ensemble methods like Random Forest are quite resistant to overfitting, a critical concern when working with complex molecular descriptors [45].

- No Pre-Selection Needed: They can handle a large number of irrelevant descriptors without requiring a complex pre-selection process [45].

- Multiple Mechanisms: They can effectively model systems with multiple mechanisms of action, which is often the case in molecular interactions [45].

3. My Random Forest model has high predictive accuracy, but the selected important features are biologically implausible or scattered across the network. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge when the topological information between features is not considered [44]. Standard Random Forest selects features based on impurity reduction, but in biological contexts, functionally related genes or molecules tend to be dependent and close on an interaction network. Scattered important features can conflict with the biological assumption of functional consistency [44].

- Solution: Consider using advanced methods like Graph Random Forest (GRF), which incorporates known biological network information (e.g., Protein-Protein Interaction networks) directly into the tree-building process. GRF guides the selection towards features that form highly connected sub-graphs, leading to more biologically interpretable and plausible results [44].

4. How can I implement tree-based feature selection in Python for my dataset of molecular descriptors?

You can use SelectFromModel from scikit-learn alongside a tree-based estimator. Below is a sample methodology, as demonstrated with the Breast Cancer dataset [19]:

5. What are the key parameters in Random Forest that influence feature importance, and how should I tune them? The behavior of a Random Forest model and the resulting feature importance can be influenced by several parameters [45]:

n_estimators: The number of trees in the forest. Using more trees generally leads to more stable feature importance scores, but with diminishing returns and increased computational cost.max_features: The number of features to consider when looking for the best split. This parameter controls the randomness of the trees and can influence which features are selected.min_samples_split,min_samples_leaf: Parameters that control the growth of the trees. Setting these too low might lead to overfitting, while setting them too high might prevent the model from capturing important patterns.

It is crucial to optimize these parameters for your specific dataset, typically using techniques like cross-validation, to ensure robust feature selection [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Feature Importance Rankings Across Different Runs

Issue: The list of top important features changes significantly each time you train the model, even with the same data.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Lack of Random Seed: The Random Forest algorithm has inherent randomness.

- Solution: Set the

random_stateparameter inRandomForestClassifierto a fixed integer value for reproducible results [19].

- Solution: Set the

- Too Few Trees: With a small number of trees (

n_estimators), the importance scores may not be stable.- Solution: Increase

n_estimators(e.g., 500 or 1000). The performance and stability tend to improve with more trees, though it will take longer to train [45].

- Solution: Increase

- High Feature Correlation: If many features are highly correlated, the model might arbitrarily choose one over another in different runs.

- Solution: Combine embedded methods with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). RFE recursively removes the least important features and re-trains the model. If one correlated feature is removed, the importance of the remaining ones increases, leading to a more robust final set [19].

Problem 2: Poor Model Performance After Feature Selection

Issue: After selecting features with a tree-based method, the model's performance (e.g., accuracy, AUC) drops significantly on the test set.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Overfitting during Selection: The feature importance was overfitted to the training set noise.

- Solution: Ensure the feature selection process is validated. Use cross-validation (e.g.,

RFECV) to determine the optimal number of features. Alternatively, perform feature selection within each fold of the cross-validation to get a unbiased performance estimate [43].

- Solution: Ensure the feature selection process is validated. Use cross-validation (e.g.,

- Overly Aggressive Threshold: The threshold for selecting features was too high, removing informative variables.

- Solution: When using

SelectFromModel, adjust thethresholdparameter. Instead of the default "mean", you can use a less aggressive heuristic like "0.1*mean" or use cross-validation to find a suitable threshold value [9].

- Solution: When using

- Loss of Interacting Features: The selection process might have removed features that are only predictive in combination with others.

- Solution: For data like genetic SNPs where epistasis (interactions) is common, ensure your method can capture these. While standard tree-based models can capture some interactions, more sophisticated models like Graph Random Forest (GRF) that explicitly use network information might be necessary [43] [44].

Problem 3: Feature Importance is Biased Towards High-Cardinality or Numerical Features

Issue: The feature importance scores seem to unfairly favor features with a large number of categories or continuous numerical features over binary or low-cardinality ones.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Impurity-Based Bias: The Gini importance (mean decrease in impurity) used in trees can be biased towards features with more categories or continuous features that have more potential split points.

- Solution:

- Use Permutation Importance as an alternative metric. It measures the drop in model performance when a feature's values are randomly shuffled, providing a more reliable measure of a feature's predictive power [46].

- For a more model-agnostic approach, you can also use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, which provide a unified measure of feature importance based on game theory and are consistent [46].

- Solution:

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Standard Tree-Based Feature Selection with Random Forest

This protocol details the standard workflow for using a Random Forest to select molecular descriptors for a predictive task, such as predicting PKCθ inhibitory activity [45].

1. Data Preparation:

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors from chemical structures. The Mold2 software can be used to calculate a large and diverse set of 2D molecular descriptors quickly and free of charge [45].

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into a training set (e.g., 75%) and an external test set (e.g., 25%). The test set must not be used in any model building or feature selection steps until the final evaluation.

2. Model Training and Feature Selection:

- Train Random Forest: On the training data, train a Random Forest model. The study on PKCθ inhibitors used 500 trees (

n_estimators=500) and amtry(ormax_features) value of one-third of the total number of descriptors by default [45]. - Extract Importance: Obtain the Gini importance for each feature from the trained model.

- Select Features: Use the

SelectFromModelmeta-transformer with a threshold (e.g., "mean" importance) to select the most relevant features. Alternatively, use the feature importance ranking to select the top k features.

3. Model Validation:

- Evaluate Performance: Train a new model (it can be Random Forest or another classifier) on the training data using only the selected features. Validate its performance on the held-out test set using metrics like R² for regression or Accuracy/AUC for classification [45].

Performance Table: PKCθ Inhibitor Prediction with Random Forest Table: Performance metrics for a Random Forest model built on Mold2 descriptors for predicting PKCθ inhibitory activity [45].

| Dataset | Number of Compounds | R² | Q² (OOB) | R²pred | Standard Error of Prediction (SEP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training Set | 157 | 0.96 | 0.54 | - | - |

| External Test Set | 51 | 0.76 | - | 0.72 | 0.45 |

Protocol 2: Network-Integrated Feature Selection with Graph Random Forest (GRF)

For biological data like gene expression, where features are connected in a network (e.g., protein-protein interactions), GRF can identify clustered, interpretable features [44].

1. Input Preparation:

- Feature Matrix: A gene expression matrix (samples x genes).

- Feature Network: A graph representing known relationships between features (e.g., a Protein-Protein Interaction network). The graph can be generated using models like the Barabási-Albert model for simulation studies [44].

2. GRF Model Training:

- Head Node Selection: Train a simple random forest with depth=1 to record how often each feature is used as the head-splitting node (

c_i) [44]. - Forest Construction: For each node

iwith non-zeroc_i, build a mini-forestF_iusingc_itrees. However, the features available for splitting in each tree are restricted to the neighborhood of the head nodeiwithin a certain hop distancekon the feature network [44]. - Importance Aggregation: The final importance of a feature is the sum of its Gini importance from all mini-forests

F_iwhere it was included [44].

3. Evaluation:

- Classification Accuracy: Compare the prediction accuracy of GRF against standard RF on an independent test set.

- Sub-Graph Connectivity: Evaluate the connectivity of the sub-graph formed by the top-selected important features, which should be higher for GRF than for RF [44].

Performance Table: Graph Random Forest vs. Standard Random Forest Table: Comparative performance of GRF and RF on a non-small cell lung cancer RNA-seq dataset [44].

| Method | Classification Accuracy | Connectivity of Selected Feature Sub-graph |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Random Forest | High | Low (Features are scattered) |

| Graph Random Forest (GRF) | Equivalent to RF | High (Features form connected clusters) |

Workflow Visualizations

Graph Random Forest (GRF) Workflow

Standard Random Forest Feature Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential computational tools and resources for tree-based feature selection in molecular research.

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Mold2 | Software for rapid calculation of a large and diverse set of 2D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [45]. | Generating input features for QSAR modeling of PKCθ inhibitors. Free and efficient. |

| scikit-learn | A popular Python library for machine learning. It contains implementations of Random Forest, SelectFromModel, and RFE [19] [9]. |

Implementing the entire feature selection and model validation pipeline. |

| PDBind+ & ESIBank | Curated datasets containing information on enzymes, substrates, and their interactions [47]. | Training AI models like EZSpecificity to predict enzyme-substrate binding. |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network | A graph database of known physical and functional interactions between proteins [44]. | Used as prior knowledge in Graph Random Forest (GRF) to guide feature selection for gene expression data. |

| SHAP/LIME | Model-agnostic libraries for explaining the output of any machine learning model, providing local and global feature importance scores [46]. | Debugging a model's prediction or understanding the contribution of specific molecular descriptors to a single prediction. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key advantages of using hierarchical graph representations over traditional molecular graphs for drug-target interaction prediction?

Traditional molecular graphs represent atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, learning drug features by aggregating atom-level representations. However, this approach often ignores the critical chemical properties and functions carried by motifs (molecular subgraphs). Hierarchical graph representations address this limitation by constructing a triple-level graph that incorporates atoms, motifs, and a global molecular node [48].

This hierarchical structure offers two key advantages:

- Richer Feature Extraction: It enables the model to exploit chemical information embedded at multiple scales—local (atoms), functional (motifs), and global (the entire molecule). This leads to more expressive and informative molecular representations [48].

- Ordered Information Aggregation: The use of unidirectional edges (from atoms to motifs, and from motifs to the global node) creates a more structured and reliable message-passing pathway compared to the unordered aggregation typical of simple readout functions in traditional Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [48].

FAQ 2: How can I automatically select and weight molecular features with different units to build an interpretable model?

The Differentiable Information Imbalance (DII) method is designed specifically for this challenge. DII is an automated feature selection and weighting filter algorithm that operates by using distances in a ground truth feature space [49] [50].

Its key capabilities include:

- Unit Alignment and Importance Scaling: DII optimizes a weight for each feature through gradient descent. This process simultaneously corrects for different units of measure and scales features according to their relative importance [50].

- Determining Optimal Feature Set Size: The method can produce sparse solutions, helping you identify the smallest subset of features that retains the essential information from the original space [49] [50].

- Versatility: It can be used in both supervised (using a separate ground truth) and unsupervised (using the full input feature set as ground truth) contexts [50].

FAQ 3: My graph-based model for virtual screening is overfitting. What techniques can improve its generalization?

Several advanced techniques demonstrated by recent frameworks can help mitigate overfitting:

- Utilize Large-Scale Pre-training: Models like MolAI are pre-trained on extremely large datasets (e.g., 221 million unique compounds). This allows the model to learn robust, general-purpose molecular descriptors that are less likely to overfit on smaller, task-specific datasets [51].

- Incorporate Domain-Aware Feature Selection: Employing rigorous feature selection methods like DII (mentioned above) reduces the dimensionality of your input data. By removing redundant or noisy features, you simplify the learning task, which helps prevent the model from overfitting to irrelevant information [49] [50].

- Leverage Hierarchical Structures: As implemented in HiGraphDTI, a hierarchical graph design can make the information aggregation process more orderly and structured, which can lead to more robust learning compared to flat graph architectures [48].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Performance in Predicting Drug-Target Interactions (DTIs)

- Symptoms: Low accuracy and AUPR on benchmark DTI datasets; model fails to identify known interactions.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Drug Representation. Using only atom-level information omits crucial functional data.

- Solution: Implement a hierarchical molecular graph. Use the BRICS algorithm (with added rules to avoid overly large fragments) to decompose the molecular graph into motifs. Construct a three-level graph (atom, motif, molecule) with unidirectional edges and use a Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) for message passing [48].

- Cause: Limited Receptive Field in Target (Protein) Features. CNN or RNN-based protein sequence models may not capture long-range dependencies effectively.

- Solution: Employ an attentional feature fusion module for target sequences. This extends the receptive field and combines information from different layers or contexts to create more expressive protein representations [48].

- Cause: Inadequate Drug Representation. Using only atom-level information omits crucial functional data.

Problem 2: Suboptimal or Redundant Feature Set in Molecular Descriptor Analysis

- Symptoms: Model performance does not improve with added features; model is difficult to interpret; features have different units and scales.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Automated Feature Weighting.

- Solution: Integrate the Differentiable Information Imbalance (DII) method. Use a ground truth feature space (e.g., all initial descriptors or a known informative set). The DII algorithm will optimize scaling weights for each feature via gradient descent to find the subset that best preserves the distance relationships in the ground truth. Applying L1 regularization during optimization can further promote a sparse, interpretable feature set [49] [50].

- Cause: Lack of Automated Feature Weighting.

Problem 3: Low Accuracy in Molecular Regeneration or Descriptor Learning

- Symptoms: An autoencoder model fails to accurately reconstruct input molecules from its latent space representation.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient Model Capacity or Training Data.

- Solution: Adopt a framework like MolAI, which uses an autoencoder neural machine translation (NMT) model trained on a massive dataset (hundreds of millions of compounds). This scale of data and model architecture has been shown to achieve extremely high accuracy (e.g., 99.99%) in molecular regeneration, leading to high-quality latent space descriptors [51].

- Cause: Insufficient Model Capacity or Training Data.

The table below summarizes quantitative results from key studies on the advanced techniques discussed.

Table 1: Performance of Advanced Feature Selection and Representation Learning Models

| Model / Method | Core Technique | Dataset / Application | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolAI [51] | Deep Learning Autoencoder (NMT) | 221M unique compounds; Molecular regeneration | Reconstruction Accuracy | 99.99% |

| HiGraphDTI [48] | Hierarchical Graph Representation Learning | Four benchmark DTI datasets | Prediction Performance (vs. 6 state-of-the-art methods) | Superior AUC and AUPR |

| DII [49] [50] | Differentiable Information Imbalance | Molecular system benchmarks; Feature selection for machine learning force fields | Optimal Feature Identification | Effective identification of informative, low-dimensional feature subsets |

| LGRDRP [52] | Learning Graph Representation & Laplacian Feature Selection | Drug response prediction (GDSC/CCLE) | Average AUC (5-fold CV) | Superior to state-of-the-art methods |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Hierarchical Molecular Graph Representation for DTI Prediction

This protocol outlines the methodology for constructing a hierarchical graph for drug molecules, as used in HiGraphDTI [48].

- Input: Drug molecule (SMILES string or 2D structure).

- Atom-Level Graph Construction: Convert the molecule into a graph ( G=(V,E) ), where ( V ) represents atoms (nodes) and ( E ) represents bonds (edges).

- Motif-Level Graph Construction:

- Molecular Decomposition: Use the Breaking of Retrosynthetically Interesting Chemical Substructures (BRICS) algorithm to partition the molecular graph into functional motifs.

- Supplement BRICS: Apply an additional rule to disconnect cycles and branches around minimum rings to prevent excessively large fragments.

- Create Motif Nodes: Define a set of motif nodes ( V_m ), where each node corresponds to one obtained fragment.

- Create Atom-Motif Edges: For each atom that is part of a motif, create a unidirectional edge pointing from the atom node (in ( V )) to the corresponding motif node (in ( Vm )). The collection of these edges is ( Em ).

- Graph-Level Construction:

- Create Global Node: Introduce a single global node ( V_g ) to represent the entire molecule.

- Create Motif-Global Edges: Connect every motif node to the global node with a unidirectional edge pointing from the motif to ( Vg ). The collection of these edges is ( Eg ).

- Message Passing and Embedding: The final hierarchical graph is ( \bar{G}=(\bar{V},\bar{E}) ), where ( \bar{V}=(V,Vm,Vg) ) and ( \bar{E}=(E,Em,Eg) ). Use a Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) to propagate messages and learn node embeddings at each level. The final drug representation is derived from the global node and the aggregated motif nodes.

Diagram: Workflow for Hierarchical Molecular Graph Construction

Protocol 2: Applying Differentiable Information Imbalance (DII) for Feature Selection

This protocol describes the steps for using DII to select and weight an optimal subset of molecular features [49] [50].

- Data Preparation: Consider a dataset with ( N ) data points (e.g., molecules). Each point ( i ) is described by two sets of features:

- Input Feature Space (A): ( Xi^A \in R^{DA} ), the large set of initial molecular descriptors from which you want to select.

- Ground Truth Feature Space (B): ( Xi^B \in R^{DB} ), assumed to be fully informative. This can be the full input feature set ( A ) (for unsupervised learning) or a separate, trusted set of features or labels (for supervised learning).

- Distance and Rank Calculation: For a chosen distance metric (e.g., Euclidean), compute:

- The pairwise distance matrix in the ground truth space ( B ).

- The distance ranks ( r{ij}^B ), where ( r{ij}^B = k ) if point ( j ) is the ( k )-th nearest neighbor of point ( i ) in space ( B ).

- Parameterize and Compute DII: Let the distance in the input space ( A ) depend on a set of weights ( w ). The Differentiable Information Imbalance ( \Delta(d^A(w) \to d^B) ) is a differentiable function that measures how well distances in the weighted input space predict distances in the ground truth space.

- Optimize Weights: Minimize ( \Delta(d^A(w) \to d^B) ) with respect to the weights ( w ) using gradient descent. To promote sparsity, an L1 regularization term can be added to the loss function.

- Feature Selection: After optimization, features with non-zero (or significantly large) weights form the optimal, informative subset. The magnitude of the weight indicates the feature's relative importance.