Optimizing Protein Folding: A Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Guide for Structural Biologists

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and its application to the complex challenge of protein conformation prediction.

Optimizing Protein Folding: A Mixed-Integer Linear Programming Guide for Structural Biologists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and its application to the complex challenge of protein conformation prediction. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it begins by establishing the foundational principles of MILP and its relevance to structural biology. The content then progresses to detailed methodological formulations, including the side-chain conformation problem and the use of machine learning surrogates to enhance scalability. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization techniques for managing computational complexity and offers a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of predicted protein models using established metrics. By synthesizing optimization theory with practical biological applications, this guide serves as a valuable resource for advancing computational methods in protein science and therapeutic discovery.

The Foundation of MILP in Protein Structure Prediction

Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) provides a powerful mathematical framework for solving complex optimization problems with discrete decisions, making it particularly valuable in computational biology research. In protein conformation studies, MILP enables researchers to model intricate biological systems where certain variables must take integer values—such as the presence or absence of specific molecular interactions, the counting of atomic contacts, or the selection of discrete conformational states. Unlike continuous optimization methods, MILP can handle the inherently discrete nature of many biological decisions, from selecting optimal protein fragments for structure prediction to determining the presence of specific residue-residue contacts in folding models.

The fundamental strength of MILP lies in its ability to mathematically formalize biological problems without requiring researchers to develop custom algorithms from scratch. Instead, scientists can describe their problem using linear inequalities and objective functions, then leverage sophisticated MILP solver libraries to find optimal solutions. This approach has proven effective across numerous biological domains, including nurse rostering, kidney exchange programs, production scheduling, and energy optimization in robotic cells [1]. In the context of protein conformation research, MILP offers a structured methodology for tackling the combinatorial complexity inherent in predicting and analyzing protein structural states.

Core MILP Concepts for Computational Biologists

Mathematical Foundations

A Mixed Integer Linear Programming problem can be mathematically represented as finding a vector x that:

Minimizes: fᵀx Subject to: A·x ≤ b Aeq·x = beq lb ≤ x ≤ ub xᵢ is integer for all i ∈ intcon [2]

Here, f represents the objective function coefficients, A and b define linear inequality constraints, Aeq and beq define linear equality constraints, lb and ub set lower and upper bounds on variables, and intcon identifies which variables must take integer values. The power of this formulation for biological problems stems from the ability to represent complex relationships through linear constraints while maintaining discrete decision variables.

In protein conformation studies, these mathematical components map directly to biological concepts. The objective function might represent energy minimization or probability maximization; constraints can represent physical limitations like bond lengths or angle restrictions; binary variables can indicate whether particular structural features are present; and integer variables might count occurrences of specific motifs or interactions. This mapping from biological reality to mathematical abstraction enables researchers to leverage decades of algorithmic advancements in optimization theory.

Essential MILP Tools and Reagents

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools for MILP in Biological Research

| Tool Name | Language/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python-MIP (with CBC solver) | Python | MILP modeling and solving | Bundled with open-source CBC solver; intuitive Python API [1] |

| intlinprog | MATLAB | MILP solver | Integrated with MATLAB ecosystem; supports various integer types [2] |

| scipy.optimize.milp | Python | MILP solver | Part of SciPy ecosystem; handles basic MILP problems [3] |

MILP Applications in Protein Conformation Research

Current Challenges in Conformational Studies

Proteins exist as dynamic ensembles of conformations rather than single static structures, and understanding these multiple structural states is crucial for deciphering biological function and advancing drug discovery. Traditional physics-based simulation methods like molecular dynamics often struggle with sampling equilibrium conformations and are computationally expensive [4]. While deep learning approaches such as AlphaFold2 have revolutionized static structure prediction, they tend to represent single conformational states, with multiple-conformation prediction remaining a significant challenge [5].

Recent research demonstrates that proteins adopt multiple structural conformations to perform their diverse biological functions, and capturing this diversity computationally requires methods that can efficiently explore conformational landscapes [4]. Experimental techniques like fluorescence spectroscopy provide valuable insights into conformational changes by detecting alterations in fluorophore behavior resulting from changes in nano-environment, but translating these experimental observations into predictive models requires sophisticated computational frameworks [6].

MILP-Enhanced Conformational Sampling

MultiSFold represents an innovative approach that combines MILP principles with evolutionary algorithms to predict multiple protein conformations. This method uses a distance-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm where multiple energy landscapes are constructed using different competing constraints generated by deep learning. An iterative modal exploration and exploitation strategy samples conformations by incorporating multi-objective optimization, geometric optimization, and structural similarity clustering [5].

In benchmark evaluations against state-of-the-art methods using a set of 80 protein targets each characterized by two representative conformational states, MultiSFold achieved a remarkable success ratio of 56.25% in predicting multiple conformations, compared to only 10.00% for AlphaFold2 [5]. This demonstrates how optimization-based approaches can enhance conformational sampling beyond what single-structure predictors can achieve.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Protein Conformation Prediction Methods

| Method | Approach Type | Multiple Conformation Success Rate | Typical Application Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| MultiSFold | Multi-objective evolutionary with MILP principles | 56.25% | Multiple conformation sampling [5] |

| AlphaFold2 | Deep learning | 10.00% | Static structure prediction [5] |

| Structure Language Models (SLM) | Deep generative | 20-100x speedup over physics-based | Efficient conformation generation [4] |

| Traditional MD | Physics-based simulation | Limited by timescale | Atomic-level dynamics [4] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common MILP Implementation Issues

Solver Status and Solution Validation

Problem: Solver reports optimal solution but constraints are violated.

This issue occurs when the MILP solver returns a solution marked as "optimal" that nevertheless violates specified constraints, such as variable bounds. As reported in a SciPy issue, users have encountered situations where scipy.optimize.milp provides solutions that violate bounds without raising errors [3].

Solution:

- Always validate solution feasibility by checking all constraints explicitly in your code

- Implement post-solution verification to ensure variable values respect all bounds and constraints

- Consider tightening solver tolerance settings if available

- For the specific SciPy issue, monitor the GitHub repository for bug fixes and updates [3]

Reproducible Code Example Demonstrating the Problem:

Excessive Solution Times for Biological Problems

Problem: MILP model for protein conformation analysis takes too long to solve.

The exponential complexity of MILP problems means that solution time can grow dramatically with problem size. A model with "just" 1000 binary variables has 2¹⁰⁰⁰ possible solutions—far too many to evaluate exhaustively, as this would require more energy than the world's annual consumption and more time than the age of the universe to solve at typical LP rates [7].

Solution:

- Reformulate problems to reduce the number of binary variables

- Implement problem-specific heuristics to provide good initial solutions

- Use valid inequalities to tighten the formulation

- Exploit problem structure through decomposition techniques

- Set appropriate optimality gap tolerances to obtain good solutions faster

- Leverage symmetry-breaking constraints where applicable

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What types of biological decisions are best suited for MILP formulation?

MILP is particularly well-suited for biological problems involving discrete choices or counting, such as selecting optimal protein fragments in structure prediction, determining the presence or absence of specific molecular interactions, identifying activation pathways in signaling networks, or optimizing experimental design with limited resources. The key requirement is that the problem can be expressed with linear constraints and an objective function, with some variables restricted to integer values.

Q2: How can I determine if my protein conformation problem is too large for MILP?

As a rough guideline, problems with hundreds of binary variables may be solvable to optimality, while problems with thousands of binary variables might require heuristic approaches or significant simplification. The exponential complexity of MILP means that problem size dramatically impacts solvability. For context, a problem with just 72 binary variables already has more possible solutions (2⁷² ≈ 4.7×10²¹) than the number of LP relaxations a solver could evaluate in a year at 315 billion per year [7].

Q3: What are the most common causes of infeasible MILP models in biological applications?

The most frequent causes include overly restrictive constraints that conflict with each other, incorrect variable bounds that eliminate all feasible solutions, improperly implemented logical conditions, and numerical issues in constraint formulation. To diagnose infeasibility, systematically relax constraints to identify conflicts, and use solver features like irreducible inconsistent subset (IIS) analysis when available.

Q4: Can MILP be combined with machine learning for protein conformation prediction?

Yes, hybrid approaches are increasingly common. For example, deep learning can generate potential constraints or objective function parameters, which are then processed using MILP optimization. Structure Language Models (SLM) represent one such hybrid approach, where protein structures are first encoded into a compact latent space using a discrete variational auto-encoder, followed by conditional language modeling that captures sequence-specific conformation distributions [4].

Q5: What computational resources are typically required for MILP problems in structural biology?

Resource requirements vary dramatically with problem size and complexity. Small problems (under 100 binary variables) may solve in seconds on a laptop, while larger problems may require high-performance computing resources with substantial memory (64+ GB RAM) and multiple CPU cores. The worst-case computational resource requirement grows exponentially with problem size, making careful problem formulation essential.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MILP Protocol for Conformational Analysis

Objective: Formulate and solve a MILP problem to identify optimal conformational states based on energetic and spatial constraints.

Materials:

- MILP solver (Python-MIP, MATLAB intlinprog, or similar)

- Structural constraints derived from experimental data or predictive models

- Computational environment with adequate RAM and processing power

Procedure:

- Problem Definition: Identify the discrete decisions (binary variables) and continuous parameters in your conformational analysis problem

- Objective Function Formulation: Define the optimization goal (e.g., energy minimization, probability maximization) as a linear function of decision variables

- Constraint Specification: Translate physical, chemical, and biological limitations into linear constraints:

- Spatial constraints (distance bounds, steric exclusion)

- Energetic constraints (favorable interactions, penalty avoidance)

- Biological constraints (known contacts, functional requirements)

- Variable Declaration: Specify integer and continuous variables with appropriate bounds

- Model Solving: Implement the model in your chosen solver environment

- Solution Validation: Verify that the solution satisfies all constraints and makes biological sense

Expected Results: A set of variable values representing an optimal conformational state or ensemble of states that satisfies all specified constraints while optimizing the objective function.

Advanced Protocol: Multi-Objective Conformational Sampling

Objective: Identify multiple Pareto-optimal conformational states using multi-objective optimization principles.

Procedure:

- Multiple Objective Definition: Identify competing objectives (e.g., energy minimization vs. conformational diversity)

- Constraint Generation: Use deep learning methods, such as those in MultiSFold, to generate competing constraints for multiple energy landscapes [5]

- Iterative Exploration: Implement modal exploration and exploitation strategies combining:

- Multi-objective optimization algorithms

- Geometric optimization procedures

- Structural similarity clustering

- Pareto Front Identification: Solve the multi-objective problem to identify non-dominated solutions

- Loop Refinement: Apply loop-specific sampling strategies to adjust spatial orientations in final populations

Validation: Compare predicted conformational diversity with experimental data from techniques like fluorescence spectroscopy, which can detect conformational changes through alterations in fluorophore behavior and nano-environment [6].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The integration of MILP with other computational approaches represents the cutting edge of protein conformation research. Structure Language Models (SLM) exemplify this trend, offering a novel framework that provides 20-100x speedup over existing methods in generating diverse conformations [4]. These approaches combine the representational power of deep learning with the precise constraint satisfaction of mathematical optimization.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are also emerging as complementary technologies to MILP in bioinformatics. GNNs perform well on graph structure data, making them suitable for representing molecular interactions and biological networks [8]. While GNNs excel at learning patterns from complex biological data, MILP provides a framework for incorporating explicit constraints and optimization objectives, suggesting potential for powerful hybrid approaches.

Future developments will likely focus on improving the scalability of MILP approaches for larger biological systems, enhancing integration with experimental data from techniques like fluorescence spectroscopy, and developing more sophisticated multi-objective formulations that better capture the trade-offs inherent in biological systems. As these methodologies mature, MILP is poised to become an increasingly essential tool in the computational biologist's toolkit for unraveling the complexities of protein conformation and function.

Defining the Protein Conformation and Side-Chain Prediction (SCP) Problem

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core computational challenge of the Side-Chain Prediction (SCP) problem? The SCP problem is NP-hard, meaning there is no known algorithm that can solve all its instances efficiently and optimally [9]. The challenge is to find the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) for side-chain rotamers given a fixed protein backbone. This involves searching a combinatorial space of possible rotamer combinations, which grows exponentially with the number of residues [9] [10].

FAQ 2: How does Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) apply to SCP? MILP provides a framework for finding provably optimal solutions to the SCP problem. The problem can be formulated as a quadratic assignment problem, which is then linearized into an MILP model [9]. The formulation uses binary variables to represent the selection of specific rotamers for each residue and linear constraints to ensure exactly one rotamer is chosen per residue. The energetic interactions between the backbone and a rotamer, and between pairs of rotamers, are captured in the objective function [9].

FAQ 3: My global optimization is too slow. What are proven acceleration strategies? A primary strategy is to use the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem as a pre-processing step [9]. DEE prunes rotamers and rotamer pairs that are provably not part of the global minimum energy conformation, dramatically reducing the problem's search space before applying MILP or other combinatorial optimization algorithms [9].

FAQ 4: What are the limitations of the rotamer approximation? The rotamer library approach discretizes the continuous dihedral angle space into a finite set of statistically likely conformations [9]. While this simplification makes the problem computationally tractable, it is an approximation. The true energetically minimal protein conformation may involve dihedral angles that do not exactly match any rotamer in the library [9].

FAQ 5: How does protein conformation relate to biomolecular function? A protein's specific three-dimensional shape, or conformation, is directly responsible for its function [11]. The characteristic 3D shape is defined by its secondary, supersecondary (motifs), tertiary (domains), and quaternary structure [12]. Changes in conformation, such as those mediated by intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), can drive processes like liquid-liquid phase separation, which is crucial for cellular compartmentalization and regulating biochemical reactions [13].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Computational Issues

Problem 1: Inaccurate Energy Evaluation in Computational Models

- Symptoms: Predicted side-chain conformations are energetically unfavorable or clash when validated with molecular dynamics. The model fails to recapitulate native sequences in design tasks [14].

- Solution:

- Employ a Combined Energy Function: Utilize a force field that integrates multiple terms. A proven function includes [14]:

- An explicitly orientation-dependent hydrogen-bonding potential.

- A pairwise-decomposable Generalized Born model for electrostatic interactions in buried areas.

- A pairwise surface-area-based term for hydrophobic contribution.

- Protocol: Parameterize your energy function using all-atom empirical potentials like CHARMM or AMBER [14]. Validate the function by testing its ability to discriminate native enzyme sequences from non-native alternatives at ligand-binding sites [14].

- Employ a Combined Energy Function: Utilize a force field that integrates multiple terms. A proven function includes [14]:

Problem 2: Handling Exponentially Large Search Spaces

- Symptoms: MILP solver fails to find a solution in a reasonable time or runs out of memory for proteins with more than 100 residues.

- Solution:

- Apply Dead-End Elimination (DEE): Before invoking the MILP solver, use DEE to reduce the rotamer library. DEE eliminates rotamers that are provably not part of the global energy minimum [9].

- Use a Heuristic Algorithm: For very large proteins, consider switching to a fast heuristic algorithm like BetaSCP2, which uses Voronoi diagrams and quasi-triangulation to find excellent (though not always provably optimal) solutions efficiently [10].

Problem 3: Integrating Side-Chain Prediction with Backbone Flexibility

- Symptoms: Predictions are inaccurate because the rigid backbone assumption is invalid for your target protein.

- Solution:

- Implement a Backbone Relaxation Protocol: After an initial round of side-chain positioning, allow the backbone to move slightly to relieve atomic clashes and find a lower energy state.

- Detailed Protocol [10]:

- Step 1: Predict side-chain conformations onto the fixed backbone using your chosen method (e.g., MILP).

- Step 2: Identify all severe atomic clashes in the resulting model.

- Step 3: Apply a constrained energy minimization algorithm that allows for small adjustments in both side-chain and backbone atom positions to resolve clashes.

- Step 4: Iterate steps 1-3 until the total system energy converges.

Research Reagent & Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Resources for SCP and Conformational Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Rotamer Library | A discrete set of statistically significant side-chain conformations derived from structural databases [9]. | Provides the finite set of possible states for each residue in the SCP problem, turning a continuous search into a combinatorial one [9]. |

| Dead-End Elimination (DEE) | A domain filtering algorithm that prunes rotamers provably not part of the global minimum energy conformation [9]. | Used as a pre-processing step to dramatically reduce the size of the SCP problem before optimization [9]. |

| MILP Solver | Software (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) that finds solutions to optimization problems with discrete and continuous variables [9]. | Solves the linearized formulation of the SCP problem to find the global optimum (GMEC) for a fixed backbone [9]. |

| BetaSCP2 | A heuristic program that uses Voronoi diagrams and quasi-triangulation for rapid side-chain positioning [10]. | Provides a fast, near-optimal solution for the SCP problem, useful for high-throughput applications or very large proteins [10]. |

| CHARMM/AMBER Force Fields | All-atom empirical potentials for molecular dynamics and energy calculation [14]. | Provides the energy parameters (e.g., for van der Waals, electrostatics) used in the objective function of the SCP model [14]. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of SCP Methodologies

| Method Type | Key Feature | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact (MILP) | Finds provably global energy minima. | Accuracy is 100% by definition if converged; computing time can be prohibitive for large systems [9]. | [9] |

| Heuristic (BetaSCP2) | Uses Voronoi diagrams for clash detection and rapid optimization. | Finds an excellent solution quickly; benchmark tests show high efficiency [10]. | [10] |

| Energy Function for Design | Combined H-bond, Generalized Born, and hydrophobic potential. | Recapitulated 78% of native amino acids at ligand-binding sites in minimum-energy sequences [14]. | [14] |

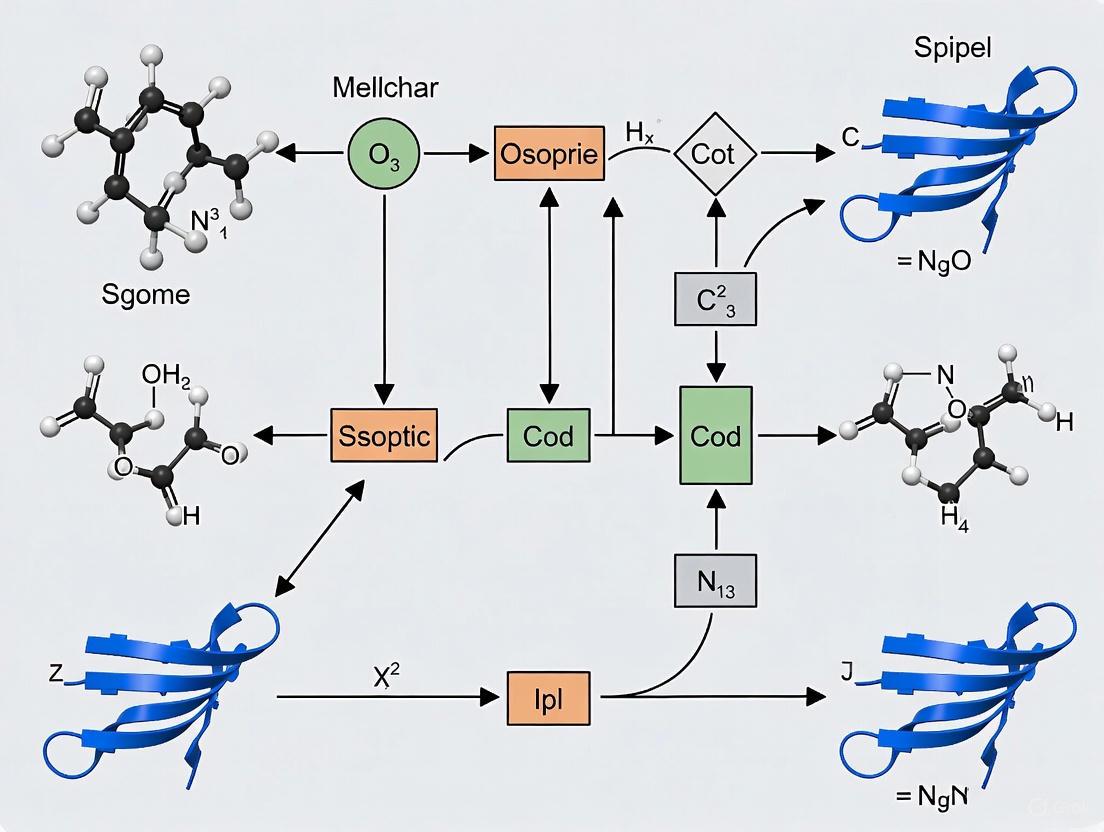

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for tackling the Side-Chain Prediction problem using an optimization-based approach.

SCP Problem Solving Workflow

What is the Rotamer Approximation? The rotamer (rotational isomer) approximation is a foundational technique in computational structural biology used to solve the protein side-chain conformation problem. This problem involves predicting the optimal three-dimensional arrangement of amino acid side-chains when given a fixed protein backbone. Instead of treating side-chain dihedral angles as continuous variables, the rotamer approximation discretizes the problem by restricting potential side-chain conformations to a finite set of low-energy, frequently observed orientations known as rotamers, which are compiled in rotamer libraries [15] [16].

Why is the Rotamer Approximation Necessary? The side-chain conformation problem is computationally NP-hard [15] [16]. Attempting to find a global minimum energy conformation by searching all possible continuous dihedral angles is computationally infeasible for even moderate-sized proteins. The rotamer approximation simplifies this intractable continuous search into a discrete optimization problem that can be effectively addressed with powerful mathematical programming approaches, including Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) [17] [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of error when using the rotamer approximation? The main sources of error are:

- Discretization Error: The approximation inherently assumes that the true lowest-energy conformation exists within the predefined rotamer library. If the native state adopts a conformation not listed in the library, the model cannot recover it.

- Backbone Rigidity: The problem formulation typically assumes a completely fixed, rigid protein backbone [15] [16]. In reality, side-chain packing and backbone conformation exhibit some mutual flexibility and influence.

- Energy Function Accuracy: The quality of the solution is heavily dependent on the accuracy of the force field or scoring function used to evaluate the energy of rotamer assignments and their interactions [15].

Q2: My MILP model for a large protein is computationally intractable. What simplification strategies can I employ? Several algorithmic strategies can dramatically reduce the problem's complexity:

- Residue and Rotamer Reduction: Advanced algorithms integrate techniques to eliminate residues and rotamers that are provably not part of the global energy minimum solution. The Residue-Rotamer-Reduction algorithm, for instance, can simplify the problem topology, solving problems in only 1-10% of the time required by a standard MILP approach [17].

- Dead-End Elimination (DEE): This is a classic and powerful technique that systematically removes rotamers that cannot be part of the optimal solution before the main optimization begins, significantly reducing the search space [15] [16].

- Graph-Theory Algorithms: Methods like SCWRL and others use graph theory to rapidly identify a near-optimal solution, though sometimes at the cost of guaranteed global optimality [17] [15].

Q3: How do I choose the most appropriate rotamer library for my study? Your choice should be guided by your research goal and the required accuracy.

- Backbone-Dependent Libraries: Libraries such as the one from the Dunbrack Lab are the standard for most applications. They provide rotamer probabilities and dihedral angles conditioned on the local backbone conformation (φ and ψ angles), offering higher accuracy [15] [16].

- Backbone-Independent Libraries: These are less common today but list rotamer statistics averaged across all backbone types. They may be sufficient for very low-resolution initial screening.

- Consider Library Resolution: Modern libraries often include sub-rotameric corrections (small deviations from the central rotameric angle) to improve accuracy beyond the standard discrete states.

Q4: Can the rotamer approximation be integrated with modern AI-based protein structure prediction tools? Yes, the field is moving toward hybrid approaches. While deep learning models like AlphaFold2 and ESMFold have revolutionized structure prediction, the rotamer approximation and side-chain packing remain highly relevant. AI models can provide accurate backbone structures, which are then fed as input to highly optimized side-chain packing algorithms like AttnPacker and DiffPack to build the final full-atom model [18]. The rotamer-based MILP framework provides a rigorous, energy-based optimization that complements data-driven AI predictions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unrealistic Side-Chain Clashes in Final Model

Potential Causes:

- Inadequate Van der Waals Radii: The atomic radii parameters in your energy function's steric clash term may be too small or poorly calibrated.

- Insufficient Rotamer Sampling: The rotamer library may be missing critical high-energy or rare conformations necessary to avoid clashes in tightly packed regions.

- Over-simplified Energy Function: The scoring function may lack a sufficiently repulsive term for steric overlaps or may be improperly weighted.

Solution Steps:

- Verify Parameters: Check the Van der Waals parameters in your force field (e.g., CHARMM [15] [16]). Ensure you are using standard bonded radii and scaling factors for non-bonded interactions.

- Expand the Library: Increase the rotamer library resolution. Many libraries offer "expanded" or "complete" sets that include rotamers with higher energy and sub-populations, which can provide more options for avoiding clashes.

- Refine with Continuous Minimization: Use the discrete solution from the MILP as a starting point for a subsequent, limited continuous energy minimization. This allows side-chains to relax slightly from their ideal rotameric angles to relieve minor steric strains [15].

Problem: MILP Solver Fails to Converge for a Large Protein

Potential Causes:

- Combinatorial Explosion: The number of binary variables (one per rotamer per residue) has grown too large for the solver to handle within available memory or time.

- Inefficient Formulation: The MILP formulation itself may have a weak linear programming (LP) relaxation, leading to a slow branch-and-bound process.

Solution Steps:

- Apply Pre-processing: Ruthlessly apply the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem before formulating the MILP. DEE can often eliminate a large majority of rotamers, drastically reducing the problem size [15] [16].

- Implement the R³ Algorithm: Adopt the Residue-Rotamer-Reduction algorithm, which has been demonstrated to solve hard problems 2 to 78 times faster than other widely used methods like SCWRL 3.0 [17].

- Explore Geometric Methods: Consider switching to a highly efficient geometric algorithm like BetaSCP, which uses beta-complexes derived from Voronoi diagrams to prioritize solution quality and has been shown to produce near-optimal solutions quickly for benchmarking tasks [15].

Problem: Computed Protein Energy Does Not Match Expected Value

Potential Causes:

- Incorrect Energy Term Weighting: The relative weights of the different energy terms in your objective function (e.g., Van der Waals, electrostatics, solvation, torsion) may be unbalanced.

- Parameter Inconsistency: There may be a mismatch between the force field parameters used to generate the rotamer library and those used in your MILP's scoring function.

Solution Steps:

- Re-calibrate Weights: Systematically test the weights of your energy terms on a set of proteins with known high-resolution structures. Adjust the weights to minimize the difference between the computed energy of the native structure and the predicted minimum-energy structure.

- Audit Force Field Versions: Ensure that all parameters for rotamer internal energy and pairwise interaction energies are sourced from a single, self-consistent version of a recognized force field (e.g., CHARMM [15] [16] or AMBER).

Experimental Protocol: Side-Chain Positioning via MILP

This protocol details the steps for solving a protein side-chain conformation problem using a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming approach.

Objective: To find the global minimum energy conformation of protein side-chains for a fixed backbone using the rotamer approximation and MILP.

Inputs:

- A protein backbone structure (e.g., from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or homology modeling).

- A backbone-dependent rotamer library (e.g., Dunbrack Lab library [15] [16]).

- An energy function for scoring rotamer-rotamer and rotamer-backbone interactions.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Procedure in Detail:

Pre-processing and Problem Setup

- Input Backbone: Obtain and fix the protein backbone coordinates from your source.

- Rotamer Assignment: For each residue position i, extract all possible rotamers r from the rotamer library that are compatible with the local backbone geometry.

- Dead-End Elimination (DEE): Apply the DEE theorem to identify and remove rotamers that are provably not part of the global energy minimum. This critical step drastically reduces the number of binary variables in the subsequent MILP [15].

MILP Formulation

- Binary Variables: Define a binary variable ( x{ir} ) for every rotamer *r* at residue position *i*. ( x{ir} = 1 ) indicates that rotamer r is assigned to residue i.

- Constraints: For each residue i, add a constraint: ( \sumr x{ir} = 1 ). This ensures one and only one rotamer is selected per residue.

- Objective Function: Formulate the total energy as a linear function of the binary variables.

- Singleton Energy (( E{ir} )): The energy of rotamer r at position i with the backbone. Coefficient: ( E{ir} ).

- Pairwise Energy (( E{irjs} )): The interaction energy between rotamer r at position i and rotamer s at position j. This requires introducing auxiliary binary variables ( y{irjs} ) and linear constraints to ensure ( y{irjs} = x{ir} \cdot x{js} ). Coefficient: ( E{irjs} ).

- The full objective is to minimize: ( \sumi \sumr E{ir} x{ir} + \sumi \sum{j>i} \sumr \sums E{irjs} y{irjs} ).

Solution and Validation

- MILP Solution: Use a standard MILP solver (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) to find the variable assignment that minimizes the objective function while satisfying all constraints.

- Model Reconstruction: Build the full-atom protein model by combining the fixed backbone with the optimally assigned side-chain rotamers.

- Validation: Validate the resulting structure using tools like MolProbity to check for steric clashes, reasonable bond lengths/angles, and agreement with expected Ramachandran plots.

Performance Benchmarking Data

The following table summarizes the performance of various algorithms applied to the side-chain positioning problem, as reported in the literature. This data is crucial for selecting the appropriate method for your research.

Table 1: Algorithm Performance Benchmark on Side-Chain Positioning

| Algorithm/Method | Core Approach | Computational Speed | Solution Quality | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MILP (Standard) [17] [15] | Exact Global Optimization | Slow (Baseline) | Global Optimum | Mathematical guarantee of optimality |

| Residue-Rotamer-Reduction (R³) [17] | Residue & Rotamer Reduction | 1-10% of MILP time; 2-78x faster than SCWRL 3.0 | Global Optimum | Extreme speedup while maintaining optimality |

| BetaSCP [15] | Geometric (Beta-Complex) | Fast (Reasonable time) | Very Close to Optima | High priority on solution quality |

| SCWRL 3.0 [17] | Graph Theory | Fast (Baseline for heuristics) | Lower than R³/BetaSCP | Widely used, heuristic speed |

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Rotamer-Based Studies

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Rotamer/MILP Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dunbrack Lab Rotamer Library [15] [16] | Database | Provides backbone-dependent rotamer statistics and dihedral angles. | The standard source for defining the discrete set of rotamers (( x_{ir} )) in the MILP formulation. |

| CHARMM Force Field [15] [16] | Force Field / Parameter Set | Provides energy parameters for proteins (bonded, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded). | Used to calculate the singleton (( E{ir} )) and pairwise (( E{irjs} )) energy terms in the MILP objective function. |

| SCWRL4 Software | Software Algorithm | Graph-based heuristic for rapid side-chain prediction. | A widely used benchmark and alternative when guaranteed global optimum is not required [17]. |

| BetaSCP Algorithm [15] | Software Algorithm | Side-chain positioning based on computational geometry (beta-complex). | An efficient alternative to MILP that prioritizes high-quality solutions for homology modeling and docking. |

| CPLEX / Gurobi Solvers | Optimization Software | Commercial solvers for MILP and other mathematical programming problems. | The computational engine used to find the optimal solution to the formulated MILP model. |

| R³ Algorithm Server [17] | Web Server / Algorithm | Residue-rotamer-reduction for side-chain conformation. | A dedicated tool that dramatically speeds up the solution process for large or complex proteins. |

Why MILP? Addressing NP-Hard Problems in Protein Folding

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is protein structure prediction considered an NP-hard problem, and how does MILP help? Protein structure prediction involves searching an astronomically large conformational space to find the native state. This search space grows exponentially with the number of amino acids, making an exhaustive search computationally intractable, a characteristic of NP-hard problems. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) helps by providing a powerful mathematical framework to formulate this search as an optimization problem. It allows researchers to incorporate physical constraints (like contact maps and steric hindrance) and biological data into a single model, efficiently narrowing the search to the most probable conformations and finding high-quality, feasible solutions [19] [20].

Q2: What are the typical input requirements for running a MILP-based protein contact prediction like COMTOP? The primary input is the amino acid sequence of the target protein. For optimal performance, you should generate a Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) of the target against homologous sequences using tools like PSI-BLAST, HHblits, or Jackhmmer. This MSA is used to derive co-evolutionary information. The COMTOP method, for instance, uses this data as input for its seven constituent prediction methods (CCMpred, EVfold, etc.) before the MILP consensus optimization [20].

Q3: Our MILP model fails to solve within a reasonable time for large proteins. What troubleshooting steps can we take? This is a common challenge. You can consider the following strategies:

- Adjust Solver Parameters: Relax the optimality gap tolerance. Finding a solution that is guaranteed to be within 5-10% of the optimal can be significantly faster than finding the exact optimum.

- Problem Decomposition: Break the large protein into smaller, overlapping domains, solve the MILP for each domain independently, and then reconcile the solutions.

- Strengthen Formulation: Review your constraint set to eliminate redundancies and add valid inequalities that tighten the linear programming relaxation, helping the solver prune the search tree more effectively.

- Leverage Hardware: MILP solvers can often utilize multiple CPU cores. Ensure you are running the solver on a machine with sufficient parallel processing capabilities.

Q4: How do we validate the accuracy of a predicted contact map generated by a MILP model? The standard method is to compare the predicted contacts against the native structure obtained from experimental data (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB). A residue pair is typically defined to be in contact if the distance between their Cβ atoms (Cα for glycine) is below a threshold (e.g., 8Å). Accuracy is then measured by calculating the proportion of correctly predicted contacts (True Positives) among the top L, L/2, or L/5 predicted contacts, where L is the protein's length [20].

Q5: What is the key advantage of using a consensus method like COMTOP over a single prediction method? Individual prediction methods (e.g., CCMpred, DeepCov, plmDCA) can have non-systematic errors and may perform inconsistently across different protein families. A consensus method like COMTOP integrates the strengths of multiple individual methods. By using MILP to optimize the combination of their predictions, it can cancel out individual errors and produce a more robust and accurate final contact map, as demonstrated by its higher accuracy on independent test sets [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common MILP Experiment Pitfalls

Issue: Infeasible Model Solution

- Symptoms: The MILP solver returns an "infeasible" status, meaning no solution satisfies all constraints.

- Possible Causes:

- Over-constrained Model: The distance restraints or steric clash constraints may be too strict.

- Incorrect Data: Errors in the input contact predictions or sequence alignment.

- Conflicting Constraints: Logical errors in the model formulation cause constraints to contradict each other.

- Resolution Steps:

- Relax Constraints: Loosen distance bounds or slightly reduce the clash penalty weights.

- Debug with a Subset: Run the model on a small protein fragment to isolate the problematic constraint.

- Perform a Feasibility Check: Systematically remove groups of constraints to identify which one is causing the infeasibility.

Issue: Low Prediction Accuracy on Transmembrane Proteins

- Symptoms: The model's accuracy drops significantly when applied to α-helical transmembrane proteins.

- Possible Causes:

- Lack of Homologous Sequences: Transmembrane proteins often have fewer homologs, leading to weaker co-evolutionary signals.

- Biophysical Differences: Standard contact thresholds and energy functions may not be optimal for the lipid membrane environment.

- Resolution Steps:

- Use Specialized Methods: Incorporate contact prediction methods specifically trained or tuned for transmembrane proteins.

- Adjust Parameters: Modify the contact distance threshold or the MILP objective function weights to account for the unique architecture of transmembrane domains. COMTOP, for example, showed robust performance on 57 non-redundant TM proteins by leveraging its consensus approach [20].

Issue: Excessive Memory Usage During Solver Execution

- Symptoms: The solver run is terminated due to insufficient memory, especially for large proteins.

- Possible Causes:

- Large Branch-and-Bound Tree: The problem is highly symmetric or has a weak linear programming relaxation.

- Dense Contact Map: The model is considering an excessively large number of potential residue-residue contacts.

- Resolution Steps:

- Pre-filter Contacts: Only feed the top K (e.g., top 5L) predictions from each individual method into the MILP consensus model, rather than all possible pairs.

- Set a Node Limit: Impose a limit on the number of nodes in the branch-and-bound tree to control memory usage, accepting a potentially suboptimal solution.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology for MILP-Based Consensus Contact Prediction (COMTOP)

This protocol outlines the steps for the COMTOP method, which uses MILP to combine multiple contact prediction tools [20].

Input Data Preparation:

- Sequence: Obtain the amino acid sequence of the target protein.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Generate an MSA using a tool like HHblits or PSI-BLAST against a non-redundant sequence database.

- Individual Method Predictions: Run the following seven methods using the generated MSA:

- CCMpred

- EVfold

- DeepCov

- NNcon

- PconsC4

- plmDCA

- PSICOV

- Each method will output a ranked list of residue pairs with a confidence score.

MILP Model Formulation:

- Objective: Maximize the sum of the consensus confidence scores for the selected contact pairs.

- Decision Variables: Use binary variables ( X{ij} ) for each residue pair (*i*, *j*), where ( X{ij} = 1 ) if the pair is predicted to be in contact, and 0 otherwise.

- Key Constraints:

- Number of Contacts: The total number of selected contacts ( \sum X{ij} ) should be equal to a predefined value (e.g., top L, L/2, where L is the protein length).

- Sequence Separation: ( |i - j| > L{min} ) to ensure only non-local contacts are considered.

- Physical Realism: Constraints to prevent impossible geometries (e.g., two residues cannot be in contact if they are too close in sequence).

Model Solving:

- Use a commercial or open-source MILP solver (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX, SCIP).

- Set a time limit or optimality gap tolerance for practical termination.

- Input the confidence scores from all seven methods and the formulated constraints.

Output and Validation:

- The solver outputs the set of residue pairs ( X_{ij} = 1 ), which forms the final consensus contact map.

- Validate by comparing the predicted contacts to the true structure from the PDB, calculating the precision for the top L/5, L/2, etc., predictions.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes the performance of the COMTOP consensus method compared to its individual components on a test set of 239 proteins [20].

Table 1: Protein Contact Prediction Accuracy (%) of COMTOP vs. Individual Methods

| Prediction Method | top-5L | top-3L | top-2L | top-L | top-L/2 | top-L/5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMTOP (Consensus) | 59.68 | 70.79 | 78.86 | 89.04 | 94.51 | 97.35 |

| CCMpred | 33.15 | 41.25 | 48.12 | 63.89 | 80.54 | 91.23 |

| EVfold | 31.87 | 40.11 | 46.89 | 62.14 | 79.12 | 90.56 |

| DeepCov | 35.22 | 43.89 | 51.01 | 66.78 | 83.01 | 92.98 |

| NNcon | 34.56 | 42.98 | 50.12 | 65.45 | 81.89 | 92.11 |

| PconsC4 | 36.11 | 44.75 | 52.33 | 68.02 | 84.15 | 93.67 |

| plmDCA | 32.89 | 41.02 | 48.25 | 63.45 | 80.11 | 91.34 |

| PSICOV | 31.45 | 39.78 | 46.55 | 61.89 | 78.98 | 90.45 |

The table below shows COMTOP's robust performance on different protein test sets, including those from the critical CASP assessments.

Table 2: COMTOP Performance on Independent Test Sets (top-L/5 accuracy)

| Test Set | Number of Proteins / Domains | COMTOP Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CASP13 | 32 | 75.91 |

| CASP14 | 30 | 77.49 |

| α-helical Transmembrane Proteins | 57 | 73.91 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for MILP-Based Protein Structure Research

| Item | Function in the Research Context |

|---|---|

| MILP Solver (Gurobi/CPLEX) | Software engine that finds the optimal solution to the formulated mathematical model, selecting the most likely residue-residue contacts. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Generator (HHblits/PSI-BLAST) | Tool to find homologous sequences; the resulting MSA is used to detect evolutionary couplings which are strong predictors of spatial proximity. |

| Individual Contact Prediction Tools (e.g., CCMpred, DeepCov) | A suite of independent methods that provide raw, scored contact predictions from which the MILP consensus model builds. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures; serves as the ground truth for training data and for validating prediction accuracy. |

| Graphviz | Visualization tool used to generate clear diagrams of predicted contact maps or protein folding pathways, aiding in interpretation and presentation. |

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for the MILP-based consensus contact prediction method.

MILP Consensus Prediction Workflow

This diagram outlines the core logical relationship in representing protein conformation problems as a graph to be solved by clique finding, a foundation for some MILP approaches.

Graph Theory Model for Structure

Building and Solving MILP Models for Protein Conformation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core computational challenge of the side-chain positioning problem, and why is MILP a suitable approach? The side-chain positioning problem is NP-hard [15] [16]. It involves a discrete combinatorial search to find the lowest-energy combination of side-chain conformations (rotamers) for a fixed protein backbone. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) is a suitable approach as it allows for the formulation of this complex optimization problem with discrete variables (representing rotamer choices) and linear constraints (representing steric and energetic interactions), enabling the application of powerful solvers to find provably optimal solutions.

Q2: What are rotamer libraries, and what role do they play in the MILP model? Rotamer libraries are collections of energetically favored, discrete side-chain conformations [21]. In the context of MILP, these libraries discretize the continuous conformational space, typically providing 5-6 distinct rotameric states per residue [22]. This discretization is fundamental, as each rotamer from the library becomes a potential assignment for an integer variable in the MILP model, making the vast optimization problem computationally tractable.

Q3: How are steric clashes prevented within the MILP formulation? The MILP model incorporates constraints to enforce that no two atoms in the protein come closer than a specified van der Waals distance [15]. These constraints are formulated to be active only when two specific rotamers, which cause a clash, are simultaneously selected. This ensures the final solution represents a physically realistic, sterically feasible protein structure.

Q4: Can the MILP model incorporate experimental data? Yes, the MILP framework can integrate sparse or unassigned experimental data, such as from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [21]. A likelihood function derived from the experimental data (e.g., NOESY peaks) can be incorporated into the objective function. The model then seeks the side-chain configuration that minimizes the total energy while maximizing the agreement with the experimental observations.

Q5: What is the Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem and how can it be used with MILP? The Dead-End Elimination (DEE) theorem is a method to prune rotamers that are provably not part of the global optimal solution before the main optimization [15]. By using DEE as a pre-processing step, the size of the MILP problem is significantly reduced, as many variables and constraints associated with eliminated rotamers can be removed, leading to faster solution times.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Computational Issues

Problem: The MILP model fails to find a feasible solution that satisfies all steric constraints.

- Potential Cause 1: The rotamer library is too coarse or does not contain a conformation suitable for a tight packing environment.

- Solution: Consider using a larger, more detailed backbone-dependent rotamer library [15]. For specific problematic residues, manually inspecting the local environment and adding custom rotamers may be necessary.

- Potential Cause 2: The backbone template itself may have regions of high strain or inaccuracy.

- Solution: Perform a mild energy minimization on the backbone coordinates before side-chain placement. In homology modeling, ensure the backbone template is of high quality and sequence identity.

Problem: The computation time for the MILP model becomes prohibitively long for larger proteins.

- Potential Cause: The side-chain positioning problem is NP-hard, and problem size grows combinatorially with the number of residues and rotamers per residue.

- Solution:

- Apply DEE: Rigorously use the Dead-End Elimination algorithm as a pre-processing step to reduce the problem's search space [15].

- Use a Decomposition Strategy: Instead of solving the entire protein at once, decompose it into smaller, overlapping local sites (clusters of adjacent residues), solve them independently, and then combine the results [22].

- Heuristic MILP: Configure the MILP solver to find a high-quality, near-optimal solution within a reasonable time limit, rather than insisting on proven global optimality.

Problem: The predicted side-chain conformations have high energy or disagree with experimental data.

- Potential Cause 1: Inaccuracies in the empirical energy function used in the objective function.

- Solution: Review and potentially re-parameterize the force field. Consider using a combined energy function that includes explicit orientation-dependent hydrogen-bonding potentials and solvation terms, which have shown success in recapitulating native sequences [14].

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect weighting between the different energy terms or between the energy and experimental data terms in the objective function.

- Solution: Systematically calibrate the weighting factors. For experimental data integration, employ a rigorous statistical approach, such as a Bayesian framework, to objectively estimate the noise in the data and the corresponding weight parameter [21].

Problem: How to handle side-chain conformational flexibility, given that the MILP model outputs a single conformation?

- Explanation: Protein side-chains are not always rigid but can exhibit polymorphism, adopting discrete, cloud, or flexible conformations [23]. A single-conformation MILP model may not capture this reality.

- Solution: The MILP framework can be extended. Instead of solving once, execute the model multiple times with an integer cut constraint added each time to exclude the previously found best solution. This generates an ensemble of low-energy conformations, providing a more realistic view of the side-chain conformational landscape that can be critical for understanding protein function [23].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and data resources for the side-chain conformation problem.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rotamer Libraries | Pre-compiled databases of discrete, statistically derived side-chain conformations (e.g., Dunbrack Lab library [15]) that serve as the discrete variable set for the MILP model. |

| Molecular Force Fields | Empirical energy functions (e.g., CHARMM [15]) used to calculate the potential energy of a side-chain configuration. This energy forms the core of the MILP model's objective function. |

| MILP Solver Software | Commercial or open-source optimization engines (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) that perform the algorithmic work of solving the formulated MILP problem to find the optimal rotamer assignment. |

| DEE/A* Algorithms | Deterministic algorithms used for pre-processing (DEE) to reduce problem size or as an alternative to MILP (A*) to find the global optimum solution with provable guarantees [21]. |

| Beta-Complex Geometry | A geometric construct derived from the Voronoi diagram used in advanced algorithms (e.g., BetaSCP) to efficiently compute atomic interactions and volumes, aiding in the calculation of the objective function and constraints [15] [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Unassigned NMR Data with MILP using a Bayesian Framework

This protocol details the methodology for determining high-resolution side-chain conformations by integrating unassigned Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY) data into a side-chain positioning MILP model, based on the Bayesian approach described in [21].

1. Define the Rotamer Search Space:

- For a protein with a known backbone structure, assign a set of possible rotamers from a backbone-dependent rotamer library to each side-chain residue.

2. Construct the Prior Energy Term:

- Formulate the molecular mechanics energy (e.g., van der Waals, electrostatic, solvation) for every possible rotamer and for every pair of rotamers on adjacent residues. This empirical energy function acts as the prior distribution in the Bayesian model.

3. Derive the Likelihood from Unassigned NOESY Data:

- Data Input: Use unassigned NOESY peak lists.

- Hausdorff-based Measure: Calculate the likelihood of a rotamer assignment by comparing the expected pattern of proton-proton distances for a given rotameric state against the unassigned NOESY data. This measure robustly handles the ambiguity in the data without requiring peak assignment.

4. Formulate the Posterior Probability and MILP Model:

- Bayesian Integration: Combine the prior energy and the data likelihood into a posterior probability using a Markov Random Field (MRF) model.

- Log-Transform: Convert the problem of maximizing the posterior probability into an equivalent problem of minimizing a scoring function, which is a linear combination of the energy prior and the data likelihood terms.

- MILP Formulation: Map the minimized scoring function onto an MILP objective function. Integer variables represent rotamer choices, and linear constraints enforce the selection of exactly one rotamer per residue and prevent steric clashes.

5. Estimate Noise and Solve:

- Systematic Noise Estimation: Use a grid search over possible noise parameters. For each candidate value, solve the MILP model to find the optimal side-chain conformation.

- Global Solution: Select the final structure corresponding to the noise parameter that yields the best overall agreement between the computed structure and the experimental data.

6. Validation:

- Validate the final side-chain conformations by checking their agreement with any available assigned data, their energetic reasonableness, and their rotameric states against statistical preferences.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between SCIP and the solvers in Google OR-Tools, and how do I choose for protein structure prediction?

SCIP (Solving Constraint Integer Programs) and the solvers available in Google OR-Tools (like the default MIP solver or CP-SAT) have distinct architectural philosophies. SCIP is a constraint-based framework that treats problems as a set of constraints, each handled by a specific "constraint handler," making it exceptionally good for problems that go beyond pure linearity, such as those with nonlinear components [24]. It functions as a branch-cut-and-price framework and can use external LP solvers (like CPLEX or SOPLEX) to solve the linear relaxation subproblems [25]. Google OR-Tools, on the other hand, provides a unified interface to various solver backends. For pure integer problems (ILP), it recommends the CP-SAT solver, which is a powerful constraint programming solver. For mixed-integer problems (MIP) that include continuous variables, it recommends the SCIP solver itself through its interface [26]. Your choice should be guided by your problem's nature:

- Choose SCIP directly if: Your model may incorporate non-linear elements, you need total control over the solving process (e.g., custom branching rules, heuristics), or you are working in a domain where SCIP has a proven track record [24].

- Choose Google OR-Tools if: You value a high-level, easy-to-use API in popular programming languages (C++, Python, Java, C#), want a quick way to benchmark different solvers (including CP-SAT), or are building a prototype application [26].

Q2: My MILP model for conformational ensemble generation is solving too slowly. What are the first parameters I should adjust to improve performance?

Performance tuning is critical for complex problems like generating conformational ensembles, where the search space can be vast. The first parameters to adjust are typically those that control the core branch-and-bound process and the generation of cutting planes.

Table: Key SCIP Parameters for Performance Tuning

| Parameter Category | Specific Parameter | Function | Suggested Value for Initial Trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limits | limits/time |

Sets the maximum solution time in seconds. | 3600 (1 hour) |

| Branching | branching/rule |

Selects the rule for choosing branching variables. | relpscost (Reliability Pseudocost) |

| Separating | separating/maxrounds |

Limits the number of cutting plane rounds at the root node. | 20 |

separating/maxroundsroot |

Limits the number of cutting plane rounds at the root node. | 50 | |

| Heuristics | heuristics/emphasis |

Controls the aggressiveness of primal heuristics. | aggressive |

| Numerics | numerics/feastol |

The feasibility tolerance for constraints. | 1e-6 (Default) |

The GAMS interface to SCIP also supports standard GAMS parameters like reslim (for time limit), optcr (relative optimality gap), and nodlim (node limit) to control the solving process [25]. For Google OR-Tools, you can set a time limit (Solver.SetTimeLimit) and a relative gap tolerance directly in the API [26].

Q3: How can I model "if-then" constraints, which are essential for representing specific folding rules in my protein model?

"If-then" constraints are fundamental in MILP for encoding logical relationships. The standard technique uses a binary variable and a "big-M" value. Suppose you have a condition: If condition A is true, then constraint B must hold. This can be modeled as follows:

Let y be a binary variable that is 1 if condition A is true.

Let the constraint B be: sum(c_i * x_i) <= d.

The "if-then" logic is enforced by:

sum(c_i * x_i) <= d + M * (1 - y)

Here, M is a sufficiently large constant that makes the constraint non-binding when y = 0 (condition A is false). When y = 1, the constraint becomes sum(c_i * x_i) <= d. Choosing the smallest possible valid M is crucial for numerical stability and solver performance [27].

Q4: I am getting "infeasible" results for my model. What is a systematic way to debug this?

Model infeasibility is a common issue. Follow this systematic protocol to isolate the problem:

- Check the Logs: Solver logs often provide a conflict analysis. In SCIP, look for output from the

conflictanalyzer, which can identify a subset of conflicting constraints [25]. - Relax Integer Constraints: Solve the model as a Linear Program (LP) by relaxing all integrality constraints. If the LP is feasible, the infeasibility is introduced by the integer restrictions. If the LP is infeasible, the core linear constraints conflict with each other.

- Relax and Penalize Constraints: For the infeasible LP, introduce non-negative slack variables to all constraints and add a penalty term for these slacks to your objective function. Solving this new model will show which constraints are being violated to achieve feasibility, guiding you to the source of the conflict.

- The Feasibility Pump: Use the Feasibility Pump heuristic (

heuristics/feaspumpin SCIP) to find a solution that satisfies all constraints, ignoring the objective. Its success or failure can provide insights [25].

Q5: What is the recommended way to interface with SCIP and OR-Tools in Python for high-throughput computational experiments?

For high-throughput experiments in Python, you should use dedicated, well-supported libraries.

- SCIP: The PySCIPOpt package is the official Python interface for SCIP. It is not just a wrapper but provides full access to SCIP's C API, allowing you to define custom plugins (like constraint handlers and branching rules) directly in Python, which is ideal for research [24].

- Google OR-Tools: The OR-Tools Python package (

pywraplpfor the MIP solver) is the standard and recommended way to interface with its solvers. It is designed for ease of use and rapid prototyping [26]. - SciPy: For simpler, self-contained MILP problems, the

scipy.optimize.milpfunction provides a modern and familiar interface for SciPy users, though it may not offer the same level of advanced control as the others [28].

Diagram: MILP Solver Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details the essential software "reagents" for setting up a computational environment for MILP-based protein research.

Table: Essential Software Tools for MILP-Driven Research

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Usage Context |

|---|---|---|

| SCIP Optimization Suite | A state-of-the-art MILP, MINLP, and constraint programming framework. Solves the core optimization problem [25]. | Primary solver engine, especially for non-standard or highly complex problems requiring custom algorithms [24]. |

| Google OR-Tools | An open-source software suite for combinatorial optimization. Provides a unified API to access various solvers, including its own CP-SAT and an interface to SCIP [26]. | Rapid prototyping, benchmarking, and deployment of optimization models in C++, Python, Java, or C#. |

| PySCIPOpt | A Python interface to the SCIP optimization suite. Allows researchers to leverage SCIP's power directly within the Python ecosystem [24]. | The primary interface for integrating SCIP into Python-based scientific workflows and high-throughput experiments. |

SciPy (milp) |

A function in the SciPy library for solving Mixed-Integer Linear Programs. A lightweight option for simpler problems within a familiar scientific computing environment [28]. | Solving well-defined, standard-form MILPs without the need for external solver installation. |

| GAMS | A high-level modeling system for mathematical optimization. Provides a natural way to model problems and interfaces with solvers like SCIP [25]. | Modeling complex problems in a solver-independent language, often used in traditional operations research. |

Diagram: Modular Plugin Architecture of SCIP

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why would I replace my physics-based simulation model with an ML surrogate in a protein conformation MILP? ML surrogates can approximate complex, nonlinear relationships from simulation or experimental data and be embedded directly into optimization models. This transforms intractable Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programs (MINLPs) into more solvable Mixed-Integer Linear Programs (MILPs), saving significant computational time. For instance, in process family design for carbon capture systems, replacing nonlinear GDP/MINLP models with ML-surrogate-based MILPs made finding optimal solutions in reasonable time feasible [29].

Q2: My embedded ML model is making my MILP too slow to solve. What can I do? This is a common challenge. Consider the following steps:

- Simplify the Surrogate: Use a simpler ML model architecture (e.g., linear models or shallow decision trees before large neural networks) to reduce the number of constraints and variables in the MIP formulation [30].

- Leverage Specialized Formulations: Use tools like PySCIPOpt-ML or OMLT that automatically apply efficient MIP formulations for specific predictors (e.g., using SOS1 constraints for decision trees) which can improve solver performance [30].

- Check Model Scale: Be aware that the scale of the ML model you can embed is limited. Computational results with PySCIPOpt-ML suggest that while models like gradient-boosted trees with hundreds of trees are feasible, extremely large deep learning models may be prohibitive [30].

Q3: What is the difference between a "decision-focused" and a "standard" surrogate model? A standard surrogate model is trained to minimize a prediction error (like mean squared error) against a ground-truth value. In contrast, a decision-focused surrogate is trained specifically to produce decisions (solutions) that are as close as possible to the decisions that would be made by the original, complex model. This approach, which can lead to higher quality solutions in the final optimization task, has been shown to be highly data-efficient in constructing surrogate LPs for MILPs [31].

Q4: Which ML models are best suited for creating surrogates in protein conformation studies? The best model depends on the specific task and available data. Successful applications in computational biology include:

- Neural Networks with ReLU activation: Commonly used and have well-studied MIP formulations [29] [30].

- Gradient-Boosted Trees and Decision Trees: Efficiently handled by tools like OMLT and PySCIPOpt-ML and are good for capturing non-linear relationships [29] [30].

- Structure Language Models (SLMs): A newer approach for protein conformation generation that can offer a 20-100x speedup in generating diverse conformations compared to some existing methods [4].

Q5: How do I technically embed a trained Keras model into my Pyomo optimization model? The most straightforward way is to use a dedicated library like the Optimization and Machine Learning Toolkit (OMLT). OMLT provides an interface that automatically transforms trained models from ML frameworks (including Keras, PyTorch, and Scikit-Learn) into Pyomo constraints, seamlessly integrating them into your optimization problem [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Infeasible Solutions After ML Surrogate Embedding

Problem: After embedding an ML surrogate constraint, the MILP solver returns an "infeasible" result, even though you believe a solution should exist.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Verify Surrogate Input Bounds: Ensure the input variables to the embedded ML model stay within the range of the data it was trained on. If the solver assigns values outside this range during the optimization, the ML model's output might be creating contradictions. Manually provide reasonable bounds for all input variables to the predictor [30].

- Check for Model Accuracy Drift: The surrogate might be making inaccurate predictions for certain areas of the decision space, leading to infeasibility. Validate the surrogate's accuracy on a held-out test dataset that covers the expected input domain of the optimization.

- Audit the Full MIP Formulation: The infeasibility might stem from an interaction between the new ML constraints and other existing constraints in your model. Try relaxing other constraints temporarily to isolate the problem.

- Use a Feasibility Relaxation: As a diagnostic step, you can implement a feasibility relaxation that penalizes violations of the ML surrogate constraints. If the model then solves, it indicates the surrogate constraints are the primary source of infeasibility.

Issue 2: High Computational Cost of Surrogate-Embedded MILP

Problem: The MILP with the embedded ML model takes too long to solve or runs out of memory.

Diagnosis and Resolution Steps:

- Profile the ML Model Complexity: The size and type of the ML model are the primary drivers of complexity. Refer to the table below for guidance on the impact of different model types [30].

- Choose a Simpler Surrogate: If possible, retrain and embed a simpler model (e.g., a linear model or a decision tree with less depth). The table below compares the MIP formulation complexity of common ML models.

- Exploit Solver Capabilities: Use a solver that is aware of the structure of ML constraints. The SCIP solver, integrated with PySCIPOpt-ML, can perform dynamic bound tightening, which may improve performance [30].

- Formulation Choice: Some tools allow for different MIP formulations for the same ML model (e.g., big-M vs. SOS1 constraints for neural networks). Experimenting with these can lead to performance gains [30].

Table 1: MIP Formulation Complexity of Common ML Surrogates

| ML Model Type | Key MIP Formulation Elements | Primary Drivers of Model Size | Suitability for Embedding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear/Logistic Regression | Linear constraints | Number of input features | Excellent - adds minimal complexity |

| Decision Tree | Binary variables, linear constraints | Tree depth, number of leaves | Good for small to medium-sized trees |

| Random Forest / GBDT | Multiple sets of tree constraints | Number of trees, tree depth | Can become large quickly; limit ensemble size |

| Neural Network (ReLU) | Binary variables for each neuron, linear constraints | Number of layers and neurons per layer | Challenging for large networks; use shallow architectures |

Issue 3: Selecting the Right Software Tools

Problem: The variety of available libraries for integrating ML and MIP is confusing.

Resolution: The choice often depends on your preferred modeling and ML frameworks. Below is a comparison of prominent tools to help you decide.

Table 2: Comparison of ML-in-Optimization Embedding Tools

| Tool Name | Supported ML Frameworks | Underlying Solver | Key Features / Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| PySCIPOpt-ML | Scikit-Learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, Keras, PyTorch, ONNX | SCIP (open-source) | Seamless, all-in-one open-source workflow; wide model support [30] |

| OMLT | Keras, PyTorch, ONNX (via Pyomo) | Any supported by Pyomo (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) | Integration with the flexible Pyomo modeling environment [29] [30] |

| Gurobi Machine Learning | Scikit-Learn, Keras, PyTorch (via ONNX) | Gurobi (commercial) | Tight integration and support from the Gurobi solver [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

Table 3: Essential Resources for ML-Surrogate MILP Experiments in Protein Research

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMLT (Optimization and Machine Learning Toolkit) | Software Library | Bridges ML models (from Keras, PyTorch) to optimization models (in Pyomo), enabling automatic ML constraint generation [29]. | Used to design process families for carbon capture & water desalination [29] |

| PySCIPOpt-ML | Software Library | Python package for automatically formulating & embedding trained ML predictors from many frameworks into MIPs solved by SCIP [30]. | Embedded predictors for optimizing cancer treatment, energy systems, etc. [30] |

| Structure Language Model (SLM) | ML Model / Method | Generative model for efficient exploration of diverse protein conformational ensembles; frames structure generation as a language modeling task [4]. | ESMDiff model for BPTI dynamics & conformational change pairs [4] |

| SurrogateLIB | Benchmark Dataset | A library of MIP instances with embedded ML constraints based on real-world data, useful for testing and benchmarking [30]. | Provides intuition on the scale of ML predictors that can be practically embedded [30] |

| Equivariant Graph Neural Networks | ML Model / Method | Geometric deep learning for 3D protein structure data; inherently respects rotational and translational symmetries [18]. | Used in protein structure representation learning & pre-training [18] |

Experimental Protocol: Embedding an ML Surrogate for Protein Conformation Screening

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating and embedding an ML surrogate model to efficiently screen protein conformations within a larger MILP-based design or analysis pipeline.

Objective: To approximate a computationally expensive protein energy or property function using an ML model and embed it as a constraint in a MILP to optimize a design objective.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Generate Training Data:

- Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enhanced sampling techniques, or experimental data to collect a dataset of protein conformations.

- For each conformation, record structural features (e.g., dihedral angles, distances) as input variables (X) and the target property (e.g., free energy, stability score) as the output variable (y).

- Ensure the dataset is representative of the conformational space the optimization will explore.

Train and Validate the ML Surrogate Model:

- Model Selection: Choose an ML model suitable for your data and the optimization task (e.g., Gradient-Boosted Trees for non-linearity and efficiency, or a small Neural Network for complex patterns).

- Training: Split your data into training and testing sets. Train the model to predict the target property from the input features.

- Validation: Critically assess the model's accuracy on the test set. The surrogate's predictive performance is key to the validity of the final optimization result.

Build the Base MILP Model:

- Formulate the core optimization problem relevant to your protein design goal (e.g., maximizing binding affinity, minimizing instability) using integer and continuous variables.

- Include all other relevant constraints that are not related to the surrogate model (e.g., resource limits, sequence composition rules).

Embed the ML Surrogate into the MILP:

- Use a library like OMLT or PySCIPOpt-ML to automatically formulate the trained ML model as a set of MIP constraints.

- This step technically involves:

- Creating MIP variables corresponding to the model's inputs and outputs.

- Adding constraints that replicate the model's calculations (e.g., splitting conditions for decision trees, activation functions for neural networks).

Solve the ML-Embedded MILP:

- Use a compatible MIP solver (e.g., SCIP, Gurobi) to find the optimal solution to the combined problem.

- Be prepared for potentially longer solve times compared to the original MILP without the surrogate; monitor solver progress and logs.

Experimental Validation:

- The solutions generated by the model (e.g., proposed protein sequences or conformations) should be validated experimentally where possible, using techniques such as Cryo-EM, NMR, or functional assays to confirm predicted properties [32]. This closes the loop and builds trust in the integrated computational pipeline.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a Residue-Rotamer Graph combined with Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) for protein side-chain conformation?