Optimizing Protein Purity for Crystallography: A Comprehensive Guide from Construct to Crystal

This article provides a detailed roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize protein purity for successful crystallization and high-resolution structure determination.

Optimizing Protein Purity for Crystallography: A Comprehensive Guide from Construct to Crystal

Abstract

This article provides a detailed roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to optimize protein purity for successful crystallization and high-resolution structure determination. Covering the full pipeline, it explores foundational principles of protein crystallography, methodological advances in construct design and purification, systematic troubleshooting for challenging proteins, and validation techniques to assess sample quality. By integrating current trends and data, the guide offers practical strategies to overcome the major bottleneck in structural biology, enabling reliable production of diffraction-quality crystals for biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Link Between Protein Purity and Successful Crystallization

Why Protein Crystallization Remains a Major Bottleneck in Structural Biology

For researchers in structural biology and drug development, determining the three-dimensional structure of proteins is fundamental. Despite being the source of nearly 85% of the structures in the Protein Data Bank, protein crystallization remains a significant and often formidable bottleneck [1]. This process is the critical gateway to powerful techniques like X-ray crystallography, but it is plagued by low success rates, long timeframes, and a high degree of irreproducibility. This technical support center is designed to help you troubleshoot common issues, with all guidance framed within the overarching thesis that optimizing protein purity and sample preparation is the most crucial factor for successful crystallization.

FAQs: Addressing Common Crystallization Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my protein sample not crystallizing, even with commercial screening kits?

Commercial screens are a great starting point, but their success is entirely dependent on the quality of the protein sample. The most common reason for failure is inadequate sample purity or homogeneity. Your protein should ideally be >95% pure, as impurities such as misfolded populations, proteolytic fragments, or chemical modifications (e.g., deamidation of Asn/Gln or cysteine oxidation) can disrupt the ordered crystal lattice [1]. Furthermore, your protein must be monodisperse—meaning it exists as a single, uniform species in solution. Assess this using dynamic light scattering (DLS) or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC). Finally, the protein must be stable for days or weeks, as crystal nucleation and growth are not instantaneous [1].

FAQ 2: What is the single most important factor to control before starting crystallization trials?

The consensus in the field is that protein purity and homogeneity are paramount [2] [3] [1]. A sample that is not biochemically consistent will have a very low probability of forming a regular crystal lattice. Impurities and conformational heterogeneity act as defects that prevent the long-range order required for diffraction-quality crystals.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the solubility and stability of my protein during concentration?

Concentration is a critical step where proteins often "oil out" or precipitate. To maintain solubility:

- Adjust pH: Move the buffer pH further away from the protein's theoretical pI to increase its surface charge and interaction with solvent [4].

- Use additives: Incorporate small, polar molecules like glycerol (keep below 5% v/v in crystallization drops), sucrose, or methylpentanediol [4] [1].

- Include ligands: If your protein binds a metal ion, substrate, or inhibitor, adding these can stabilize a particular conformation and improve solubility [4].

- Check salt concentration: Ensure your buffer contains at least 10-25 mM NaCl to prevent the protein from sticking to concentrator membranes [4].

FAQ 4: My protein crystallizes, but the crystals do not diffract well. What could be wrong?

Poor diffraction is often a sign of internal disorder within the crystal. This can be caused by:

- Flexible regions: Intrinsically disordered loops or domains on the protein's surface can prevent tight crystal packing [1].

- Micro-heterogeneity: Invisible impurities or a mixture of conformational states within the crystal lattice.

- Inadequate optimization: The initial crystallization condition might yield micro-crystals or crystals with high mosaicity. Fine-tuning the pH, precipitant concentration, temperature, and additives is necessary [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Problem to Solution

Table 1: Common Crystallization Problems and Evidence-Based Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Clear drop with no precipitate or crystals | Protein concentration too low; solution undersaturated. | Concentrate protein further; use a Crystool Pre-Screen kit to test suitability [4]. |

| Amorphous/precipitate | Supersaturation too high; protein denaturation at air-water interface; sample instability. | Reduce protein or precipitant concentration; include additives like MPD; use oils in batch methods to minimize interfaces [5] [3]. |

| Oily droplets or phase separation | Protein preferring protein-protein interactions over solvent interactions. | Change buffer pH; add solubilizing agents like glycerol or mild detergents [4]. |

| Micro-crystals | Excess nucleation sites; nucleation rate exceeds growth rate. | Use seeding strategies; slightly reduce supersaturation; employ heterogeneous nucleants like functionalized surfaces [5]. |

| Crystals form but are small, thin, or clustered | Stochastic and uncontrolled nucleation. | Introduce controlled nucleation methods using functionalized surfaces or nanoparticles to expand the nucleation zone to lower supersaturation levels [5]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Crystallization Experiments

| Item | Function in Crystallization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants (e.g., PEGs, Ammonium Sulfate) | Induce supersaturation by excluding water (PEGs) or salting-out (salts) [1]. | PEGs create macromolecular crowding; ammonium sulfate is a common first screen. |

| Buffers | Maintain pH stability, crucial as proteins often crystallize near their pI [1]. | Keep concentration low (<25 mM); avoid phosphates which can form insoluble salts. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME, TCEP) | Prevent cysteine oxidation, maintaining sample homogeneity [1]. | Consider half-life: TCEP is most stable, especially at high pH [1]. |

| Additives (e.g., MPD, Ligands, Metals) | Stabilize specific protein conformations, mediate crystal contacts, or improve order [3] [1]. | MPD affects the hydration shell; ligands and metals can lock flexible domains. |

| Heterogeneous Nucleants | Provide surfaces to lower the energy barrier for nucleation, improving control and reproducibility [5]. | Include functionalized surfaces or nanoparticles in screening. |

Experimental Protocols for Success

Protocol 1: Assessing Sample Quality for Crystallization

A rigorous pre-crystallization quality control check is non-negotiable.

- Purity Analysis: Run the final purified sample on an SDS-PAGE gel, followed by sensitive staining (e.g., Coomassie). The gel should show a single dominant band at the expected molecular weight [2].

- Homogeneity Analysis:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): The protein should elute as a single, symmetric peak.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): The sample should be monodisperse. A polydispersity value below 20-25% is a good indicator of a homogeneous solution suitable for crystallization trials [1].

- Stability Assessment: Use differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) to identify buffer conditions, pH, and ligands that maximize the protein's thermal stability.

Protocol 2: Hanging Drop Vapor Diffusion (The Most Popular Method)

This method is ideal for initial screening as it dynamically changes supersaturation [4].

- Prepare the Reservoir: Add 500-1000 µL of the crystallization cocktail (precipitant solution) to the well of a sealed plate.

- Mix the Drop: On a siliconized glass coverslip, mix 1 µL of your purified protein sample with 1 µL of the reservoir solution.

- Seal the Chamber: Invert the coverslip and carefully place it over the reservoir, sealing it to create a closed system.

- Incubate and Monitor: Place the tray in a vibration-free, temperature-controlled incubator. Monitor the drop regularly under a microscope for crystal growth.

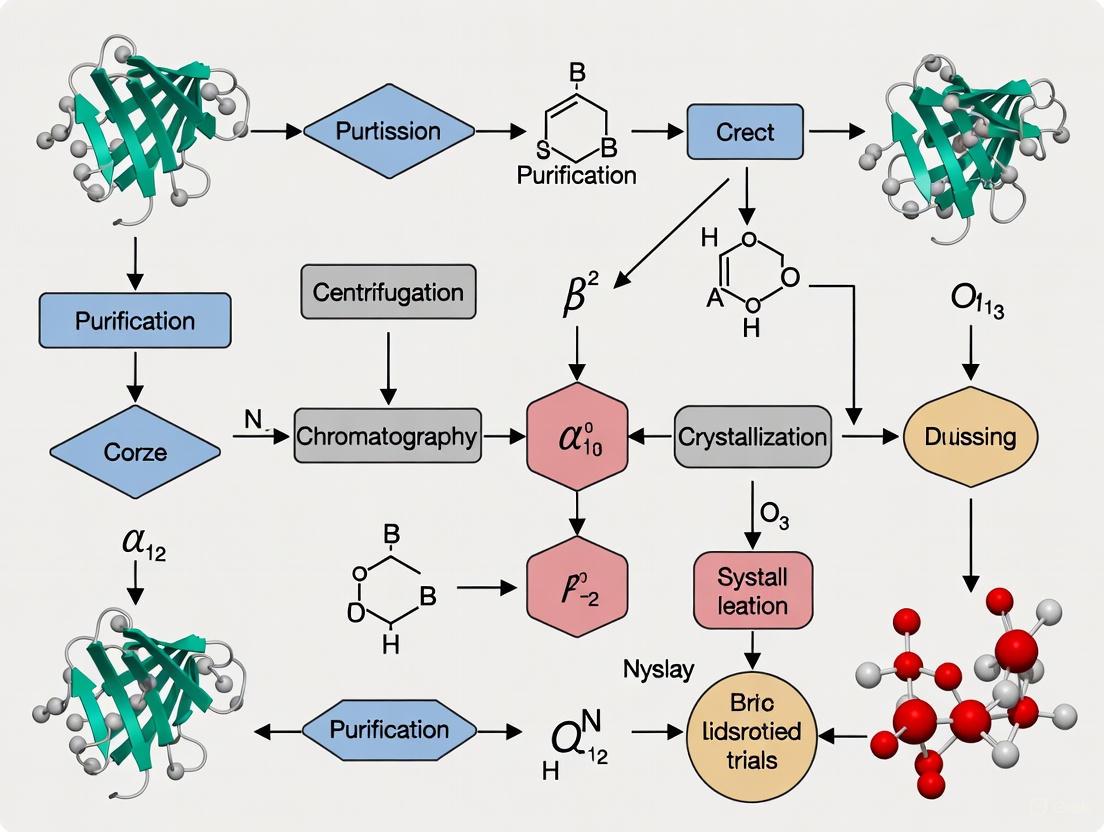

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the crystallization optimization process, from initial preparation to final structure determination.

Protocol 3: Using Solubility Additives

If your protein precipitates during concentration or in crystallization drops, follow this additive test.

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Make concentrated stocks of potential solubilizing agents (e.g., 50% glycerol, 1 M glycine betaine, 20% MPD, 10% beta-octyl glucoside).

- Test on a Small Scale: Take a small aliquot of your precipitated or "oiled" protein. On a microscope slide or coverslip, add a tiny amount of the precipitate and mix with a small drop of the additive.

- Observe: Watch under a microscope to see if the precipitate dissolves. If it does, that additive can be incorporated into your protein stock buffer or the crystallization drop to maintain solubility [4].

The following diagram outlines the decision-making process for addressing the most common crystallization problem: the absence of crystals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are my protein crystals so soft and easily damaged compared to small molecule crystals? Protein crystals are mechanically fragile because they are stabilized by a very small number of weak intermolecular contacts relative to their molecular mass. While a conventional small molecule forms many strong bonds with its neighbors in a crystal, protein crystals are primarily held together by sparse, weak interactions like salt bridges, hydrogen bonds, and hydrophobic interactions. Furthermore, the high solvent content (typically around 50%, but can range from 25% to 90%) creates a crystal that is, in many ways, more akin to an ordered gel, making it soft and prone to disintegration upon dehydration [3].

FAQ 2: How does high solvent content affect X-ray diffraction data collection? The high solvent content means that protein crystals have inherently weak lattice forces. This often results in weaker optical properties and poor X-ray diffraction intensity compared to crystals of small molecules. The extensive interstitial solvent channels allow for free diffusion of solvent and other small molecules, but the disorder associated with this solvent can contribute to higher B-factors (atomic displacement parameters) and limit the resolution obtainable in diffraction experiments [3] [6].

FAQ 3: What are the primary biochemical factors that influence crystal quality? The key factors are:

- Purity: A high level of purity (typically >95%) is essential. Impurities such as misfolded populations, oligomerization, or chemical modifications (e.g., cysteine oxidation, deamidation) can disrupt the ordered crystal lattice and lead to poor diffraction [1].

- Homogeneity & Solubility: The sample must be monodisperse and not prone to aggregation. Techniques like dynamic light scattering (DLS) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) are used to assess homogeneity. A highly soluble sample in a simple buffer is ideal for crystallization [1].

- Stability: The protein must remain stable for extended periods (days to months) as crystals nucleate and grow. Buffer components, salts, and stabilizing additives (e.g., ligands, reductants) are often necessary to maintain stability [1].

FAQ 4: My crystals form but do not diffract well. What could be the cause? Poor diffraction can be caused by several factors rooted in the unique nature of protein crystals:

- Internal Disorder or Flexibility: Flexible regions in the protein can cause conformational heterogeneity, leading to a disordered crystal lattice [1].

- Crystal Packing and "Rocking Motion": The protein molecules within the crystal lattice can undergo a slight overall "rocking" motion. The amplitude of this motion varies between crystal forms and is directly correlated with the resolution obtainable in X-ray experiments [6].

- Lattice Defects: Imperfections in the crystal lattice, which can arise from growth conditions or sample heterogeneity, can disrupt the periodic order needed for high-resolution diffraction [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Consistent Crystal Cracking or Disintegration

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Crystals crack when handled or cryo-cooled. | Mechanical stress from weak lattice forces and high solvent content. | Optimize cryoprotection by gradually transferring crystals to a mother liquor containing cryoprotectants like glycerol, MPD, or high-molecular-weight PEGs [1]. |

| Crystals disintegrate upon harvesting. | Dehydration due to exposure to air. | Ensure crystals remain in their mother liquor or a stabilizing solution during manipulation. Use loops or capillaries that keep the crystal bathed in liquid [3]. |

Problem 2: Crystals Form but Diffract Poorly (Low Resolution/Weak Intensity)

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Diffraction patterns are weak or streaky. | High mosaicity or static disorder within the crystal lattice. | Improve crystal quality by post-crystallization treatments, such as annealing, or use seeding techniques to promote more ordered growth [8]. |

| Diffraction spots are sparse. | Small crystal size or intrinsic molecular motion. | Increase protein concentration in crystallization trials or optimize conditions to grow larger crystals. Consider if the protein has flexible regions that could be truncated [1] [9]. |

| Poor scaling statistics between datasets. | Systematic errors from radiation damage, absorption, or sample heterogeneity. | Use modern scaling software that employs advanced algorithms, including those based on machine learning/variational inference, to better correct for systematic errors [7]. |

Problem 3: Failure in Auto-indexing During Data Processing

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| "Utter failure" or "misprediction" of the reflection lattice. | Incorrect experimental parameters or crystal-related issues. | Verify critical experimental parameters: X-ray beam position, crystal-to-detector distance, and detector rotation values. Ensure the oscillation range is appropriate (e.g., 1.0° for proteins) [10]. |

| "Kind-of-failed" indexing with high distortion. | Crystal twinning or multiple lattices. | Adjust auto-indexing parameters such as resolution limits to exclude reflections from ice rings or satellite crystals. For twinned crystals, expert intervention or growing new crystals may be necessary [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Assessing and Optimizing Protein Sample Quality for Crystallization

Objective: To ensure the protein sample is pure, stable, monodisperse, and at a high concentration suitable for crystallization trials [1] [9].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample

- Analytical SEC column, DLS instrument, or mass photometer

- Buffers and reagents for stability assays (e.g., differential scanning fluorimetry)

Methodology:

- Purity Analysis: Verify protein purity (>95%) using SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry to check for modifications [1].

- Stability Assessment: Use differential scanning fluorimetry or circular dichroism to identify buffer conditions, pH, and ligands that maximize protein thermal stability [1].

- Homogeneity and Solubility Check:

- Perform analytical size-exclusion chromatography. A symmetric, single peak indicates monodispersity.

- Use dynamic light scattering to check for aggregation. A monomodal size distribution with a low polydispersity index is ideal.

- Concentration: Concentrate the protein to the typical range of 5-20 mg/mL using an appropriate concentrator. Centrifuge the sample at high speed just before setting up crystallization trials to remove any aggregates.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Crystallization Screening Using Vapor Diffusion

Objective: To efficiently identify initial crystallization conditions using minimal protein [8] [11].

Materials:

- Purified, concentrated protein

- Commercial sparse-matrix crystallization screening kits

- Crystallization plates (sitting or hanging drop)

- Liquid handling robot (optional, for automation) [11]

Methodology:

- Plate Setup: For each condition in the screen, mix a small volume of protein solution (e.g., 100 nL) with an equal volume of reservoir (precipitant) solution on a sitting drop bridge or cover slip [8] [11].

- Sealing: Carefully seal the plate, ensuring the reservoir solution is in contact with the drop to allow for vapor diffusion equilibration.

- Incubation: Incubate the plates at a constant temperature (e.g., 20°C or 4°C). Avoid vibration.

- Imaging and Monitoring: Use an automated imaging system to regularly monitor the drops for crystal formation over days to weeks. Advanced imagers can use UV, SONICC, or multi-fluorescent imaging to distinguish protein crystals from salt [11].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Crystallization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A common precipitant that induces macromolecular crowding, reducing protein solubility and promoting crystal contacts [1]. | Available in a range of molecular weights. Higher molecular weight PEGs act primarily through volume exclusion. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | A salt that causes "salting-out," competing with the protein for water molecules and driving the protein out of solution [1]. | The optimal concentration is protein-dependent. A common component of dedicated screening kits. |

| 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) | A precipitant and additive that binds to hydrophobic protein regions and affects the overall hydration shell [1]. | Also commonly used as a cryoprotectant. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | A reducing agent that prevents cysteine oxidation and disulfide bond formation, maintaining protein stability [1]. | Preferred over DTT for long crystallization times due to its longer solution half-life across a wide pH range. |

| Lipid Cubic Phase (LCP) | A matrix for crystallizing membrane proteins, providing a membrane-like environment [11]. | Essential for obtaining high-quality crystals of integral membrane proteins. |

| Affinity Tags (e.g., His-tag) | Aids in purification and can sometimes improve solubility or act as a crystallization chaperone [1] [9]. | May need to be cleaved off if it interferes with crystal packing. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Protein Crystallization and Optimization Workflow

Relationship Between Crystal Properties and Diffraction Quality

The Direct Correlation Between Sample Homogeneity and Crystal Diffraction Quality

Technical FAQs: Unpacking the Homogeneity-Diffraction Relationship

FAQ 1: Why does my protein sample need to be highly pure and homogeneous to form high-quality crystals?

Protein crystallization is a process of forming a highly ordered, three-dimensional lattice. Sample homogeneity is critical because any impurities or heterogeneous populations of your protein (e.g., misfolded forms, aggregates, or contaminating proteins) can disrupt the regular molecular packing required for a perfect crystal. Even minor impurities can act as nucleation sites for disordered aggregation or incorporate into the growing crystal, creating defects that scatter X-rays and severely limit diffraction resolution [1] [12]. A purity level of at least 95% is typically recommended as a starting point for crystallization trials [13].

FAQ 2: What are the practical consequences of using a non-homogeneous sample?

Using a non-homogeneous sample significantly increases the risk of crystallization failure or can lead to misleading results.

- Crystallizing a Contaminant: There are documented cases where a contaminating protein, present in a partially purified sample, crystallizes instead of the target protein. One study reported crystallizing E. coli inorganic pyrophosphatase from a non-homogeneous sample intended for a shrimp thioredoxin. The contaminant protein was identified only after arduous structural analysis, wasting significant time and resources [12].

- Poor Diffraction Quality: Even if the target protein crystallizes, samples with conformational heterogeneity or aggregates often yield crystals with high disorder. This manifests as weak, diffuse diffraction patterns with limited resolution, often preventing complete structure determination [1] [14]. Techniques like diffraction rastering can sometimes salvage data from heterogeneous crystals by identifying the best-diffracting regions, but this is a corrective measure, not a substitute for a quality sample [14].

FAQ 3: Which biochemical parameters are most critical to monitor for ensuring sample homogeneity?

Several key parameters must be controlled and assessed prior to crystallization trials [13] [1]:

- Purity: Assessed by SDS-PAGE, aiming for >95% homogeneity.

- Conformational Homogeneity: The protein should exist in a single, uniform conformational state. This is distinct from purity and is assessed by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), which confirm a monodisperse population in solution [15] [1].

- Structural Integrity: Techniques like Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy can confirm the protein's secondary structure is intact and folded correctly [13].

- Oligomeric State: The protein should be in a consistent oligomeric state (monomer, dimer, etc.), which can be analyzed by SEC coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) [1].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the homogeneity of a challenging protein sample?

If your sample lacks homogeneity, consider these strategies:

- Construct Design: Use predictive tools like AlphaFold3 to identify and remove flexible regions that cause conformational heterogeneity. Affinity tags can sometimes improve solubility and act as crystallization chaperones [1].

- Optimize Purification: Incorporate an additional polishing step, such as ion-exchange chromatography, following initial affinity purification to remove impurities and misfolded species.

- Add Stabilizing Agents: Include ligands, substrates, or coenzymes in your buffer to stabilize a specific conformational state. The choice of reducing agent is also critical; TCEP is often preferred over DTT or BME for its longer half-life across a wide pH range, preventing cysteine oxidation that leads to heterogeneity [1].

- Advanced Crystallization Methods: Techniques like microseed matrix screening (MMS) can guide a heterogeneous sample toward a homogeneous nucleation pathway, improving crystal order [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Problem to Solution

Table 1: Common Homogeneity Issues and Corrective Actions

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Solution & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Microcrystals or Precipitate | Protein aggregation or heterogeneous oligomeric state. | Analyze by DLS and SEC. Increase purity; add stabilizing additives or ligands; optimize buffer conditions (pH, salt) [1] [16]. |

| Crystals Do Not Diffract | Internal crystal disorder due to conformational heterogeneity or impurities. | Improve sample homogeneity. Use diffraction rastering to find best-diffracting region [14]. Try additive screens or post-crystallization soaking [16]. |

| Crystallizing a Contaminant | Inadequate purity; contaminant is more crystallization-prone. | Repurify sample to >95% homogeneity. Ensure target protein is the dominant species (>80%) in the sample [12]. |

| Crystal Twinning or Poor Morphology | Sample heterogeneity or non-optimal crystallization conditions. | Improve sample homogeneity. Systematically optimize crystallization conditions (pH, precipitant concentration, temperature) around the initial hit [16]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Methods

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Homogeneity and Crystallization

| Reagent / Method | Function in Ensuring Homogeneity & Crystallization |

|---|---|

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Polishing step to separate monomers from aggregates and ensure a homogenous oligomeric state [13] [1]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Rapidly assesses sample monodispersity and identifies aggregation prior to crystallization trials [13] [15]. |

| Affinity Tags (e.g., His-tag) | Enables initial protein purification. The tag's position (N- or C-terminal) can influence solubility and should be optimized [17]. |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | A stable reducing agent that prevents disulfide bond formation and oxidation, maintaining structural homogeneity over long crystallization times [1]. |

| Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS) | An optimization technique that uses crushed microcrystals to provide uniform nucleation sites, promoting growth of larger, more ordered crystals [15]. |

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | A common precipitant that induces macromolecular crowding, reducing protein solubility and driving crystal formation through entropic effects [1] [16]. |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

The following diagram and protocol outline a robust strategy for progressing from a purified protein to a high-diffracting crystal, emphasizing steps that enhance sample homogeneity.

Detailed Protocol for Optimization via Microseed Matrix Screening (MMS)

MMS is a powerful method to improve crystal quality from an initial hit by controlling nucleation [15].

Objective: To reproduce and optimize crystal growth using microseeds from initial crystals, leading to larger and more diffraction-quality crystals.

Materials:

- Purified, homogeneous target protein (>95% purity, monodisperse by DLS).

- Initial crystallization condition that produced small crystals or microcrystals.

- Seed Beads (Hampton Research).

- Crystallization plates (e.g., 96-well sitting-drop plates).

Method:

- Seed Stock Preparation:

- Harvest the initial small crystals from the drop using a micro-tool or by crushing a crystal-containing capillary.

- Transfer them to a microtube containing a small volume (e.g., 50 µL) of a stabilizing solution (typically the crystallant solution from the initial condition).

- Add Seed Beads and vortex the mixture thoroughly to crush the crystals into micro-fragments. This creates your "seed stock."

- Prepare a dilution series (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) of the seed stock in the stabilizing solution.

Microseed Matrix Screening:

- Set up a new crystallization plate with drops that systematically vary the chemical parameters of your initial condition (e.g., precipitant concentration, pH).

- Using an automated liquid handler or manually, add a tiny volume (e.g., 0.1-0.5 µL) of a diluted seed stock to each new crystallization drop before setting up the experiment.

- Incubate the plate and monitor crystal growth. The presence of microseeds promotes nucleation in a controlled manner, often at lower levels of supersaturation than required for spontaneous nucleation, which favors orderly growth over precipitation.

Analysis:

- Identify the conditions that yield single, well-formed crystals.

- Use these optimized conditions to reproduce crystal growth for X-ray diffraction experiments.

Advanced Concepts: Pushing the Boundaries of Quality

For proteins that remain recalcitrant to forming high-quality crystals on Earth, microgravity environments offer a unique avenue for improvement. In microgravity, convection currents are minimized, and crystal growth is dominated by diffusion. This quiescent environment can lead to the formation of crystals with superior internal order, larger size, and fewer defects, directly resulting in enhanced diffraction quality [18]. Commercial efforts are now leveraging this principle for proteins of high therapeutic value, such as monoclonal antibodies, not only for structure determination but also to develop improved pharmaceutical formulations with better stability and delivery properties [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is protein purity so critical for crystallization, and what level is required? Achieving high purity is a prerequisite for successful crystallization because impurities disrupt the uniform molecular packing required to form a well-ordered crystal lattice. Sources of heterogeneity include protein isoforms, flexible regions, misfolded populations, and chemical modifications like cysteine oxidation or deamidation [1]. It is recommended that your sample has a purity level exceeding 95% before embarking on crystallization trials [1].

FAQ 2: Does a thermodynamically stable protein guarantee successful crystallization? Not necessarily. While extremely low stability (unfolded proteins) is detrimental, and very high stability may be slightly beneficial, overall thermodynamic stability is not a major determinant of crystallization propensity across the typical range for folded proteins [19]. The key factor appears to be the prevalence of well-ordered, low-entropy surface epitopes capable of forming specific crystal contacts, rather than global stability [19].

FAQ 3: My protein is pure but doesn't crystallize. What surface properties should I investigate? Proteins with surface regions of high conformational entropy (often from flexible loops or side-chains of residues like Lys, Glu, and Gln) can inhibit crystallization. A proven strategy is surface entropy reduction (SER), where such surface residues are mutated to smaller residues like alanine to reduce the entropic penalty of forming crystal contacts [19]. Tools like AlphaFold3 can guide construct design by identifying and helping to eliminate floppy regions [1].

FAQ 4: How do I choose a reducing agent for my crystallization buffer? The choice of reductant should consider the experimental timescale and buffer pH, as their stability in solution varies significantly. The table below compares common reducing agents.

Table: Solution Half-Lives of Common Biochemical Reducing Agents

| Chemical Reductant | Solution Half-Life (pH 6.5) | Solution Half-Life (pH 8.5) |

|---|---|---|

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | 40 hours | 1.5 hours |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | 100 hours | 4.0 hours |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | >500 hours (across pH 1.5–11.1 in non-phosphate buffers) | >500 hours (across pH 1.5–11.1 in non-phosphate buffers) |

Source: [1]

FAQ 5: How can solution additives like urea help in crystallization? Traditionally known as a denaturant, urea at sub-denaturing concentrations can modulate protein-protein interactions and promote crystallization. It increases protein solubility and, when combined with salts that decrease solubility (like NaCl), allows for independent fine-tuning of the crystallization environment. Urea can enable crystallization at lower supersaturation levels and may enhance both nucleation and growth rates at a fixed chemical potential difference [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistent Amorphous Precipitation Instead of Crystals

This is often a sign of sample heterogeneity or non-ideal solution conditions.

- Assessment 1: Check Oligomeric State and Monodispersity.

- Method: Use Size-Exclusion Chromatography coupled with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS) or Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS).

- Expected Outcome: A single, monodisperse peak. Proteins that form specific, homogeneous oligomers (e.g., dimers) crystallize more readily than monomers. Conversely, polydisperse samples or aggregates are a major bottleneck [1] [19].

- Assessment 2: Evaluate Surface Charge and Conformational Heterogeneity.

- Method: Use calibrated limited proteolysis followed by mass spectrometry or SDS-PAGE.

- Expected Outcome: A large, protected fragment indicates a well-folded core with limited disordered loops. The size of the dominant protected fragment has been shown to positively correlate with crystallization success [19].

Problem: Crystals Form but Diffract Poorly

Poor diffraction can result from internal disorder within the crystal, often caused by flexibility or impurities.

- Assessment 1: Analyze Surface Entropy.

- Method: Inspect your protein sequence for clusters of high-entropy residues (Lys, Glu, Gln). Use SER-predicting servers and design point mutations (e.g., to Ala) to create more ordered surface patches [19].

- Assessment 2: Investigate Crystal Packing.

- Method: If a low-resolution structure is available, analyze the crystal contacts. Alternatively, use construct design to remove flexible N/C-terminal or loops, guided by structure prediction tools like AlphaFold3 [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Pre-crystallization Assessment

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SEC-MALS System | Determines absolute molecular weight and quantifies oligomeric state homogeneity. | The gold standard for confirming sample monodispersity prior to crystallization trials. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) | Identifies optimal buffer conditions, pH, and ligands by measuring thermal stability. | A high-throughput method to find conditions that maximize protein stability. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Assesses sample purity and oligomeric state under native conditions. | A standard workhorse for quality control; look for a symmetric elution peak. |

| TCEP Reductant | Maintains cysteine residues in a reduced state. | Superior to DTT for long-term crystallization experiments due to its pH-independent stability [1]. |

| Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Kits | Provide primers and protocols for mutating high-entropy surface residues. | A rational mutagenesis approach to improve crystallization propensity. |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Pre-crystallization Assessment

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for systematically assessing a protein sample prior to crystallization trials.

Title: Pre-crystallization Assessment Workflow

Detailed Methodological Steps:

Purity Analysis:

- Protocol: Perform SDS-PAGE under both reducing and non-reducing conditions to check for homogeneity and disulfide-linked aggregates. For higher resolution, use Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) to verify the molecular weight and detect chemical modifications like deamidation [1].

Stability Profiling:

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Protocol:

- Prepare a master mix containing the protein and a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange).

- Dispense into a 96-well plate containing different buffers, salts, or ligands.

- Use a real-time PCR instrument to ramp the temperature from 25°C to 95°C while monitoring fluorescence.

- Plot the data to determine the melting temperature (Tm). The condition with the highest Tm indicates the greatest stability [1].

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy Protocol:

- Dialyze the protein into a volatile buffer or use a buffer with low UV absorbance.

- Collect far-UV spectra (e.g., 190-250 nm) to confirm proper secondary structure.

- For chemical denaturation, collect CD signals at a fixed wavelength (e.g., 222 nm) while titrating in a denaturant like guanidinium HCl to determine unfolding thermodynamics [19].

- Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Protocol:

Oligomeric State Analysis:

- SEC-MALS Protocol:

- Equilibrate the SEC column with your chosen crystallization buffer.

- Inject the protein sample and simultaneously monitor the UV, light scattering, and refractive index signals.

- The MALS detector allows for the direct calculation of the absolute molecular weight of the eluting species, independent of elution volume, providing a definitive assessment of monodispersity [1] [19].

- SEC-MALS Protocol:

Sequence and Surface Analysis:

Strategic Approaches to Protein Production and Purification for Crystallography

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Common Challenges in Construct Design

Q1: How do I decide between using a large fusion tag like MBP versus a small peptide tag like NEXT?

The choice depends on a balance between the solubility enhancement needed and the potential interference with your protein's function or crystallization. Large tags like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP, ~40 kDa) are powerful for preventing aggregation and enhancing soluble expression but can impose a significant metabolic burden and may need to be removed for functional studies or crystallization. Smaller tags like the NEXT tag (5.5 kDa) or SynIDPs (<20 kDa) are less likely to interfere with the native structure and activity of the passenger protein, often eliminating the need for tag removal [21] [22]. For proteins where maintaining activity without cleavage is a priority, smaller, intrinsically disordered tags are preferable.

Q2: My protein is still insoluble after adding a fusion tag. What are my next steps?

Insolubility despite fusion tags suggests the need for a combined strategy. Consider the following:

- Co-express Molecular Chaperones: Co-expression of chaperone systems like GroEL-GroES or DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE can assist in the proper folding of the target protein by providing a supportive environment [23].

- Screen Chemical Chaperones: Add low molecular weight compounds like glycerol, arginine, or cyclodextrins to the culture medium. These act as thermodynamic stabilizers, reducing aggregation of folding intermediates [23].

- Re-evaluate Your Construct: The problem may lie in intrinsic protein properties. Use bioinformatics tools to predict and truncate disordered regions or consider surface entropy reduction (SER) mutations to improve crystallizability [24] [25].

Q3: What are the best practices for removing affinity tags to avoid crystallization artifacts?

Improper tag removal is a common source of contamination. To minimize this:

- Use High-Specificity Proteases: Enzymes like TEV protease have high specificity, reducing the chance of cleaving within your target protein.

- Remove the Protease Post-Cleavage: After cleavage, use a second affinity step to capture the protease (if it is tagged) and any uncleaved fusion protein, leaving your target protein pure in the flow-through [26].

- Confirm Complete Removal: Always verify tag removal and check for residual protease contamination via SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry before proceeding to crystallization trials [26].

Q4: How can computational tools be integrated into the construct design process?

AI and bioinformatics are now central to rational design:

- Disorder Prediction: Tools like DISOPRED and IUPred can identify flexible regions at the termini or in internal loops that are prime targets for truncation to enhance protein stability and crystallization success [25].

- Surface Entropy Reduction Prediction: Algorithms can help identify surface-exposed loops with high-entropy residues (e.g., Lys, Glu) that can be mutated to smaller residues (e.g., Ala, Thr) to promote crystal contact formation [24].

- Structure Prediction: Tools like AlphaFold2 can generate reliable structural models for your target or homologs. These models are invaluable for guiding domain boundaries for truncation, identifying potential fusion tag attachment sites, and even serving as search models for molecular replacement in crystallography [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: From Insoluble Protein to Diffraction-Quality Crystals

Problem: Low Soluble Expression of Recombinant Protein

- Potential Cause 1: Aggregation-prone hydrophobic regions or unstructured termini.

- Solution: Design N- or C-terminal truncations. Use limited proteolysis combined with mass spectrometry to identify stable, structured domains [25].

- Potential Cause 2: Overwhelmed cellular folding machinery.

- Potential Cause 3: Insufficient chaperone support.

- Solution: Co-express molecular chaperones. The GroEL-GroES system is particularly effective for a wide range of proteins [23].

Problem: Protein Crystallizes but Diffracts Poorly

- Potential Cause 1: Conformational heterogeneity due to flexible regions.

- Solution: Implement Surface Entropy Reduction (SER). Mutate clusters of high-entropy residues (Lys, Glu, Gln) on the protein surface to alanine or other small residues to facilitate tighter crystal packing [24].

- Potential Cause 2: Lattice strain from impurities or micro-heterogeneity.

- Potential Cause 3: The crystals themselves are of poor morphological quality (e.g., needles, plates).

- Solution: Perform post-crystallization optimization. Use additive screens or fine-tune the concentration of precipitants and pH. Techniques like micro-seeding can also be used to improve crystal size and quality [27].

Problem: Solved Structure Reveals the Wrong Protein

- Potential Cause: Crystallization of a persistent contaminant.

- Solution: Identify common contaminants. Proteins from the expression host (e.g., E. coli YodA) or exogenous proteins like lysozyme or TEV protease are frequent culprits [26].

- Solution: If a structure cannot be solved, use computational tools like Fitmunk to identify the sequence from electron density or perform a molecular replacement search using a database of common contaminants [26].

Quantitative Data for Informed Decision-Making

Table 1: Comparison of Common and Novel Fusion Tags

| Tag Name | Size (kDa) | Key Mechanism | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBP [21] | 40.4 | Acts as a solubility enhancer; possible folding catalyst | Very high success rate for soluble expression | Large size can affect passenger protein activity; often needs removal |

| GST [21] | 25.7 | Dimerization can aid solubility | Easy purification via glutathione resin | Dimerization may be undesirable; can be insoluble itself |

| SUMO [22] | ~12 | Acts as a chaperone; highly soluble | Enhances expression and solubility; recognized by highly specific protease | Less effective than MBP for some difficult proteins |

| NEXT [21] | 5.5 | Intrinsically disordered "entropic bristle" | Small size; high efficacy; minimal effect on activity | Novel tag, less established track record |

| SynIDPs [22] | <20 | De novo designed disordered proteins; high solvation | No known biological function to interfere with host; promotes soluble folding | Designed tags, require specialized gene synthesis |

Table 2: Strategies for Solubility Enhancement and Their Applications

| Strategy | Typical Application | Key Parameters | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperone Co-expression [23] | Proteins that misfold due to lack of host folding machinery | Co-express systems like GroEL-GroES or DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE | Increased yield of natively folded, soluble protein |

| Chemical Chaperones [23] | Stabilizing folding intermediates during expression | Glycerol (0.2-1 M), L-Arg (0.2-0.5 M), Cyclodextrins | Reduced aggregation and increased soluble yield |

| Codon Optimization [23] [25] | Poor expression in heterologous hosts (e.g., E. coli) | Match codon usage to the expression host | Improved translation efficiency and higher protein yields |

| Promoter Engineering [23] | Fine-tuning expression levels to avoid aggregation | Use inducible promoters (e.g., T7, pBAD) to control rate of synthesis | Balanced expression to match host folding capacity |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) Mutagenesis

- Identify Target Residues: Using a crystal structure or a high-confidence AlphaFold2 model, identify clusters of two or three surface-exposed, high-entropy residues (Lys, Glu, Gln). These often form flexible "patches" [24] [25].

- Design Mutations: Design primers to mutate these residues to alanine, serine, or threonine. Single, double, or triple mutant combinations should be designed.

- Generate Mutants: Use site-directed mutagenesis to create the mutant constructs.

- Express and Test: Express the SER mutants in parallel with the wild-type construct. Assess for improved crystallization propensity (e.g., in sparse matrix screens) and monitor for any detrimental effects on protein stability or function using thermal shift assays or activity assays.

Protocol 2: Seeding to Improve Crystal Quality

This protocol is used when initial crystals are too small, numerous, or show poor morphology (e.g., needles, sea urchins) [27].

- Harvest Microcrystals: Transfer crystals from a nucleation-heavy drop to a microcentrifuge tube.

- Prepare Seed Stock: Add a small volume of reservoir solution and crush the crystals using a seed bead or a plastic rod to create a heterogeneous seed stock.

- Prepare Serial Dilutions: Dilute the seed stock in reservoir solution across several orders of magnitude (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000).

- Seed New Drops: In a new crystallization tray, set up drops with a slightly lower supersaturation than the initial condition. Introduce a small amount of the diluted seed stock to each drop.

- Monitor Growth: The seeds should provide nucleation sites, leading to fewer, larger, and better-ordered crystals.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: A rational workflow for protein construct design and troubleshooting, integrating computational and experimental steps.

Diagram 2: A troubleshooting pathway for identifying and solving protein crystallization contaminants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Protein Construct Design

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| TEV Protease [26] | Highly specific protease for removing fusion tags. | Cleaving His- or MBP-tags from the target protein after purification to prepare for crystallization. |

| pET Expression Vectors [23] | A family of high-expression plasmids for use in E. coli. | The most common system for recombinant protein production in prokaryotes, offering strong, inducible expression. |

| Chaperone Plasmids [23] | Plasmids for co-expressing molecular chaperones like GroEL/GroES. | Co-transformed with target protein plasmid to assist in the folding of complex or aggregation-prone proteins. |

| Ni-NTA Resin [25] | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography resin for purifying polyhistidine-tagged proteins. | The primary capture step for His-tagged recombinant proteins, offering rapid purification. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns [25] | For polishing purified protein based on hydrodynamic radius. | Final purification step to remove aggregates and ensure a monodisperse, homogeneous sample for crystallization. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) [24] [25] | Instrument to measure particle size distribution and polydispersity. | Assessing the monodispersity and aggregation state of a purified protein sample prior to crystallization trials. |

FAQs on Expression System Selection

What is the most important factor when choosing an expression system for a protein intended for crystallization?

For protein crystallization, the solubility and monodispersity of the purified protein are often the most critical factors. While yield is important for producing enough material, a highly soluble and monodisperse protein sample is essential for successful crystal formation and growth. The choice of system must balance the need for sufficient protein quantity with the paramount requirement for high-quality, homogenous protein. Eukaryotic proteins with complex folding or essential post-translational modifications (PTMs) often achieve better solubility in insect or mammalian systems, whereas many prokaryotic proteins can be successfully produced in E. coli [28].

My protein is insoluble in E. coli. What are my primary options to resolve this?

When facing insolubility in E. coli, you can pursue several strategies before switching to a more complex expression system:

- Modify Expression Conditions: Lower the induction temperature (e.g., to 18-25°C), reduce the inducer (IPTG) concentration, or use different growth media [29].

- Use Solubility-Enhancing Fusion Tags: Fuse your protein to a highly soluble tag, such as Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), Thioredoxin (Trx), SUMO, or NusA [30] [31]. These tags act as molecular chaperones to improve proper folding and solubility.

- Try a Different E. coli Strain: For toxic proteins, use strains with tighter regulatory control, such as BL21(DE3)pLysS or BL21-AI, to minimize basal expression before induction [29].

- Switch to a Eukaryotic System: If the protein is complex and requires specific PTMs, directly switching to an insect or mammalian cell system may provide the correct environment for native folding and solubility [28].

How do I choose between a peptide tag (like His-tag) and a protein tag (like MBP)?

The choice depends on your primary goal:

- Peptide Tags (e.g., His₆, Strep-tag II): These are small and primarily used for affinity purification. They are less likely to interfere with the structure and function of the target protein but offer limited solubility enhancement [30].

- Protein Tags (e.g., MBP, GST, SUMO): These are larger and are highly effective at enhancing solubility and sometimes yield. They can also be used for purification. However, their size may sometimes influence the activity or structure of the target protein and typically need to be removed for crystallization [30] [31].

For challenging proteins, a dual-tag system (e.g., His₆-MBP) is often employed, leveraging MBP for solubility and the His-tag for purification, followed by sequential tag removal [32].

Why is my protein yield low even after successful expression?

Low yields can result from several issues:

- Protein Degradation: Use protease inhibitor cocktails in lysis buffers and work quickly on ice or at 4°C [29].

- Codon Bias: The gene of interest may contain codons that are rare in E. coli, causing the ribosome to stall. Use codon-optimized gene synthesis or co-express genes for rare tRNAs [29] [9].

- Plasmid Instability: This is common with ampicillin resistance; using carbenicillin or a different antibiotic marker can help [29].

- Protein Toxicity: If the protein is toxic to the host cells, use a tightly regulated expression system and ensure cultures are not over-grown before induction [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low Solubility in Bacterial Expression

Problem: The target protein is primarily found in the insoluble fraction (inclusion bodies) after cell lysis.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid protein folding in bacterial cytoplasm | Check solubility in lysate vs. supernatant via SDS-PAGE. | Reduce induction temperature to 18-25°C [29]. Use solubility-enhancing tags (MBP, Trx, NusA) [30] [31]. |

| Lack of essential PTMs or co-factors | Perform bioinformatic analysis for known PTMs (e.g., disulfide bonds, glycosylation). | Switch to eukaryotic system (insect or mammalian cells) [28]. Use E. coli strains for disulfide bonds (e.g., Origami). |

| Aggregation due to hydrophobic surfaces | Analyze protein sequence for large hydrophobic regions. | Add compatible solubilizing agents (e.g., glycerol, low detergents) [33]. Test co-expression with molecular chaperones [30]. |

| Protein toxicity / basal expression | Check growth curve; toxic proteins cause slow growth. | Use tighter regulation (BL21-AI, pLysS strains) [29]. Add glucose to repress basal expression [29]. |

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Solubility Screening This protocol allows for rapid testing of multiple constructs and conditions in a 96-well format [9].

- Clone Generation: Obtain codon-optimized genes cloned into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pMCSG53 for His-tag fusions) from a commercial synthetic service.

- Transformation: Transform the cloning reaction into expression-grade E. coli cells directly in a 96-well plate.

- Expression Trial:

- Inoculate 200 µL of LB medium per well with antibiotics.

- Grow at 37°C until OD600 ~0.6.

- Induce with 200 µM IPTG.

- Express overnight at 25°C.

- Solubility Analysis:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation.

- Lyse cells chemically (e.g., with lysozyme) or by freeze-thaw.

- Centrifuge to separate soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions.

- Analyze fractions by SDS-PAGE to determine solubility of the target protein.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low Yield Across All Systems

Problem: The protein expresses but the final purified yield is unacceptably low.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Proteolytic degradation | Observe smearing or multiple lower bands on SDS-PAGE. | Add protease inhibitors (e.g., PMSF) to all buffers [29]. Shorten purification time and work at 4°C. Use a protease-deficient host strain. |

| Inefficient translation (codon bias) | Check gene sequence for rare codons for the host. | Use codon-optimized gene synthesis [9]. Use strains co-expressing rare tRNAs (e.g., Rosetta). |

| Instability of antibiotic selection | Observe loss of plasmid over culture time. | Replace ampicillin with carbenicillin [29]. Use a different antibiotic marker. |

| Poor purification efficiency | Measure protein concentration after each purification step. | Optimize binding/wash conditions for affinity tags. Switch or optimize the affinity tag (e.g., His vs GST). |

| Protein is toxic to host cells | Observe very low cell density at harvest. | Use a tightly regulated system (e.g., pBAD with arabinose) [29]. Induce at lower cell density and for a shorter duration. |

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Inefficient Tag Removal

Problem: The affinity or solubility tag is not completely cleaved by the protease, hindering subsequent purification and crystallization.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient protease activity or amount | Run a time-course cleavage assay and analyze by SDS-PAGE. | Increase protease-to-substrate ratio. Extend cleavage incubation time. Check protease activity with a control substrate. |

| Inaccessible protease site | The cleavage site may be sterically hidden. | Introduce a flexible linker between the tag and the target protein [30]. Test a different protease (e.g., switch from TEV to 3C protease or vice versa) [32]. |

| Suboptimal cleavage conditions | Proteases have specific buffer requirements (pH, salt, temperature). | Dialyze into the optimal buffer for the specific protease. Add reducing agents if required for protease stability. |

Experimental Protocol: Dual Protease Affinity Purification This protocol uses sequential cleavage to first identify soluble target protein and then achieve high-purity tag-free protein [32].

- Construct Design: Express the target protein as an N-terminal fusion with MBP, followed by a rhinovirus 3C protease site, a His₆ tag, and then the target protein.

- Cell Lysis and Cleavage 1:

- Lyse the cells and centrifuge to get a clear lysate.

- Incubate the lysate with 3C protease. This cleaves off the MBP tag.

- Centrifuge again. If the target protein is only soluble with the MBP tag, it will precipitate at this stage, saving time on non-viable constructs.

- First IMAC:

- If the His₆-tagged target protein remains soluble, load the supernatant onto an IMAC column.

- Wash and elute to purify the His₆-tagged protein.

- Cleavage 2:

- Incubate the eluted protein with His₆-tagged TEV protease. This cleaves off the N-terminal His₆ tag.

- Second IMAC:

- Pass the cleavage reaction over a second IMAC column.

- The His₆-tagged contaminants (the cleaved tag and the TEV protease) bind to the resin, while the pure, tag-free target protein flows through in the column effluent.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential reagents and materials for recombinant protein expression and purification workflows.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| pMCSG53 Vector | A destination vector for ligation-independent cloning (LIC), featuring an N-terminal, cleavable hexa-histidine tag for affinity purification [9]. |

| MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein) Tag | A large (~42.5 kDa) protein tag that acts as a potent solubility enhancer; can also be used for affinity purification on amylose resin [32] [30]. |

| His₆ Tag | A small peptide tag that allows for purification via Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC) using nickel or cobalt resins [32] [9]. |

| TEV (Tobacco Etch Virus) Protease | A highly specific protease used to remove affinity tags; it recognizes a seven-amino-acid sequence (Glu-Asn-Leu-Tyr-Phe-Gln-Gly) and cleaves between Gln and Gly [32]. |

| 3C Protease (Rhinovirus) | A protease used for tag removal that recognizes the sequence Leu-Glu-Val-Leu-Phe-Gln-Gly-Pro and cleaves between Gln and Gly [32]. |

| SUMO Tag | An 11 kDa tag that enhances solubility and folding. It allows for precise and efficient cleavage by the specific SUMO protease [30]. |

| BL21(DE3) E. coli Strain | A common bacterial host for protein expression from T7-promoter based vectors. Derivatives like pLysS and AI allow for tighter control of basal expression [29]. |

Experimental Workflows for Protein Production

The following diagram illustrates a high-throughput pipeline for screening soluble protein expression.

The following diagram outlines the dual-protease purification strategy for obtaining pure, tag-free protein.

Troubleshooting Guides

Affinity Chromatography Troubleshooting

Q1: My target protein is eluting as a very broad, low peak. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

This issue often relates to suboptimal elution conditions or non-specific binding.

- Potential Cause 1: Inefficient elution. The current elution buffer may not effectively displace the target protein from the ligand.

- Solution: Modify your elution conditions. If using competitive elution, increase the concentration of the competing molecule in the elution buffer. Alternatively, try a different elution buffer system altogether [34].

- Potential Cause 2: Denaturation or aggregation. The target protein may have denatured and aggregated on the column.

- Solution: Ensure that your binding and wash buffers contain appropriate stabilizing agents and are at a suitable pH. Incorporating a step to remove aggregates before loading onto the column is also recommended [34].

- Experimental Protocol: For difficult elution, try a stop-flow technique: stop the flow for several minutes during elution to allow time for the target protein to dissociate, then resume flow to collect the protein in pulses [34].

Q2: I notice my protein is leaking through and eluting while I am still applying the binding buffer. Why is this happening?

This indicates that binding to the affinity resin is insufficient.

- Potential Cause: The binding conditions are not optimal for the protein-ligand interaction.

- Solution: Find better binding conditions. This may involve adjusting the pH, ionic strength, or composition of the binding buffer. You can also apply the sample in multiple aliquots, stopping the flow for a few minutes between each application to increase contact time with the resin [34].

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Troubleshooting

Q3: How do I select the most appropriate SEC column for my protein?

The choice of column is critical for achieving an effective size-based separation and depends on the molecular weight of your target protein and its potential aggregates [35].

- Decision Factor 1: Pore Size. The average pore size of the particles determines the range of molecular sizes that can be separated.

- Experimental Protocol: Experimentally determine the calibration curve for your column by injecting a mixture of standard proteins of known molecular weight. This provides a practical understanding of the column's separation range [35].

- Decision Factor 2: Particle Size and Column Length. Modern SEC columns use smaller particles (<3 µm) packed in shorter columns (e.g., 150 mm). Smaller particles provide higher efficiency, which can be used to either improve resolution or decrease analysis time [35].

Q4: My protein recovery from SEC is low. What are the common reasons?

While not explicitly detailed in the search results, a fundamental principle of SEC is minimizing non-size-based interactions.

- Potential Cause: Non-specific interactions between your protein and the stationary phase chemistry.

- Solution: Carefully choose the mobile phase composition to suppress these interactions. The mobile phase should ensure high protein solubility and contain components that minimize attractive forces with the stationary phase [35]. Using the wrong pore size can also lead to co-elution of your target with other molecules, giving the appearance of low recovery [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why is high protein purity critical for crystallization research? A: High-quality, pure protein samples are essential for growing well-ordered crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography. Impurities can disrupt the uniform packing of protein molecules into a crystal lattice, preventing crystallization or leading to crystals that do not diffract well [36] [37].

Q: What are the latest technological trends impacting protein purification for structural biology? A: The field is increasingly adopting automation and miniaturization. Microfluidic screening platforms dramatically reduce sample volume needs and can screen thousands of crystallization conditions in minutes. Furthermore, the integration of AI and advanced software is accelerating sample screening and data analysis, improving the success rate of structural determinations [36].

Key Data Tables

Table 1: SEC Column Selection Guide Based on Protein Size

| Target Protein Type | Typical Molecular Weight Range | Recommended Average Pore Size |

|---|---|---|

| Small Therapeutic Proteins | 15 – 80 kDa | 150 – 200 Å |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | ~150 kDa | 200 – 300 Å |

| Very Large / PEGylated Proteins | > 200 kDa | 500 – 1000 Å |

Source: Adapted from [35]

Table 2: Impact of Key Drivers on the Protein Crystallization Market

| Market Driver | Example / Impact | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Rising investment in biopharma R&D | Drives demand for high-throughput crystallography; e.g., Thermo Fisher spent USD 1.3 billion on R&D in 2023. | Medium Term (2-4 years) |

| Growing adoption of protein therapeutics | Regulatory filings for biologics require atomic-level structural data. | Long Term (≥ 4 years) |

| Miniaturized microfluidic platforms | Reduces sample needs by an order of magnitude and speeds up screening. | Short Term (≤ 2 years) |

Source: Summarized from [36]

Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Multi-Step Protein Purification

| Item | Function in Purification |

|---|---|

| Affinity Resins (e.g., Ni-NTA, Protein A/G) | Selectively captures a target protein from a complex mixture based on a specific tag or biological interaction. |

| Ion Exchange Resins (e.g., Cation/Anion Exchangers) | Separates proteins based on their net surface charge, effective for polishing and removing impurities. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Separates proteins based on hydrodynamic size, ideal for final polishing, buffer exchange, and removing aggregates. |

| Microfluidic Crystallization Chips | Miniaturized platforms for high-throughput screening of crystallization conditions using nanoliter volumes of protein. |

| Crystallization Reagents & Kits | Pre-mixed solutions of precipitants, buffers, and salts used to establish conditions for protein crystal growth. |

| Neutralization Buffer (e.g., 1M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0) | Used to quickly neutralize low-pH elution fractions from affinity chromatography to preserve protein activity [34]. |

Obtaining high-quality crystals for structural biology is critically dependent on the purity and stability of the protein sample. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance for key biophysical techniques used in quality control: SDS-PAGE, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), and Thermal Shift Assays (TSAs). These methods collectively assess protein purity, monodispersity, and stability—essential prerequisites for successful crystallization trials. The following FAQs address specific experimental challenges researchers encounter when preparing proteins for crystallography.

SDS-PAGE Troubleshooting Guide

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a fundamental technique for assessing protein purity, molecular weight, and integrity prior to crystallization screens.

FAQ: Why are my protein bands smeared or poorly resolved on SDS-PAGE?

Smeared bands compromise the assessment of sample purity and can indicate issues that will hinder crystallization.

| Cause | Explanation | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Voltage | Excessive heat generation causes band distortion and smiling effects [38]. | Run gel at 10-15 V/cm; use lower voltage for longer time; employ cooling systems [38]. |

| Improper Sample Preparation | Incomplete protein denaturation leads to abnormal migration [39]. | Boil samples 5 minutes at 98°C with adequate SDS and reducing agents (DTT) [39]. |

| Incorrect Gel Percentage | Poor sieving of proteins due to inappropriate polyacrylamide matrix [39]. | Use lower % gels for high molecular weight proteins; higher % for low molecular weight proteins [39]. |

| Protein Overload | Well overloading causes aggregation and poor band resolution [40]. | Load recommended 10-20 µg protein per well; validate optimal amount for each protein [39] [40]. |

| Old or Improper Buffers | Incorrect ion concentration/pH disrupts current flow and protein migration [38] [39]. | Prepare fresh running buffer with correct salt concentration before each run [39]. |

FAQ: My samples are leaking out of wells or showing unusual migration patterns. What's wrong?

Unusual migration can prevent accurate purity assessment and molecular weight validation.

- Sample Leakage from Wells: Ensure loading buffer contains sufficient glycerol (for density) and avoid overloading wells beyond 3/4 capacity. Rinse wells with running buffer before loading to remove air bubbles [40].

- Vertical Streaking: Often caused by protein precipitation. Add solubilizing agents (urea for hydrophobic proteins), ensure adequate SDS concentration, and remove cell debris through centrifugation [40] [41].

- "Smiling" Bands (Curved Bands): Caused by excessive heat during electrophoresis. Run gel at lower voltage, in a cold room, or with ice packs in the apparatus [38].

- Edge Effect (Distorted Peripheral Lanes): Avoid empty wells at gel periphery. Load protein ladder or control samples in outside wells to ensure even current distribution [38].

FAQ: Why are no bands or faint bands visible after staining?

This prevents meaningful assessment of protein integrity and purity.

- Insufficient Protein Loaded: Concentrate protein samples or increase loading volume; confirm protein concentration before loading [41].

- Protein Degradation: Add fresh protease inhibitors during sample preparation and work quickly on ice to minimize proteolysis [41].

- Running Gel Too Long: Proteins may have run off the gel. Stop electrophoresis when dye front reaches bottom of gel; optimize run time for target protein size [38].

- Staining Issues: Use fresh staining solutions; ensure proper staining and destaining times; check for SDS interference with dye binding [41].

SDS-PAGE Experimental Protocol

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology

Sample Preparation

Gel Preparation

- Resolving Gel: Prepare appropriate acrylamide concentration (e.g., 8-15%) based on target protein size. Add ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED last to initiate polymerization. Pour between glass plates and overlay with water or isopropanol for a level surface [41].

- Stacking Gel: Once resolving gel polymerizes, prepare stacking gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide). Pour over resolving gel and immediately insert comb without introducing air bubbles [41].

Electrophoresis

Staining and Visualization

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Troubleshooting

DLS measures the hydrodynamic radius of proteins in solution and assesses monodispersity, a critical factor for crystallization.

FAQ: Why is my DLS data showing high polydispersity or multiple peaks?

This indicates sample heterogeneity or aggregation, which severely compromises crystallization.

- Protein Aggregation: Filter samples through 0.1-0.22 μm filters before analysis; centrifuge at high speed to remove aggregates; consider adding stabilizing additives to buffer [42].

- Dust or Contaminants: Use ultrapure, filtered buffers; ensure cuvettes are meticulously cleaned [42].

- Incorrect Protein Concentration: Overly concentrated samples cause intermolecular interference. Dilute sample to appropriate concentration (typically 0.5-1 mg/mL for most proteins) [42].

- Unstable Buffer Conditions: Ensure pH and ionic strength are optimal for protein stability; avoid buffer conditions near protein's isoelectric point [42].

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Troubleshooting

SEC separates proteins by their hydrodynamic volume and is a critical polishing step to remove aggregates and contaminants before crystallization.

FAQ: Why are my SEC peaks broad, asymmetric, or showing abnormal retention?

Abnormal SEC profiles indicate issues with protein conformation or column performance.

- Protein Aggregation or Interaction with Column: Use SEC columns with appropriate pore size (Superdex 75 for small proteins, Superdex 200 for larger complexes); add low concentration of arginine or mild detergents to mobile phase to reduce interactions [42].

- Column Overload: Reduce sample injection volume or protein concentration [42].

- Buffer Incompatibility: Ensure SEC buffer matches sample buffer composition to prevent precipitation; include necessary additives or salts [42].

- Poor Column Performance: Store columns properly in preservatives; clean and sanitize regularly according to manufacturer instructions [42].

SEC Experimental Protocol

Workflow Overview

Detailed Methodology

Column Preparation

Sample Preparation and Injection

- Concentrate protein sample to required concentration (typically 1-5 mg/mL depending on protein and column size) [42].

- Centrifuge sample at high speed (14,000 × g) or filter through 0.22 μm filter to remove aggregates [42].

- Inject appropriate volume (typically 0.5-2% of column volume) using sample loop or autoinjector [42].

Chromatography and Fraction Collection

Analysis

Thermal Shift Assay Troubleshooting

TSAs measure protein thermal stability and the effects of ligands or buffer conditions, helping identify stabilizing conditions for crystallization.

FAQ: Why are my thermal melt curves irregular or lacking clear transitions?

This prevents accurate determination of protein stability and optimal crystallization conditions.

- Poor Fluorescence Signal: Ensure dye concentration is optimal; check protein-dye compatibility; use high purity SYPRO Orange or similar dyes [43].

- Protein Aggregation During Heating: Include additives to prevent aggregation; optimize protein concentration; try different buffer conditions [43].

- Compound Interference: Some buffer components or test compounds may interfere with fluorescence. Include appropriate controls and test compound-only samples [43].

- Low Protein Stability: Protein may be inherently unstable. Consider buffer optimization, adding stabilizing ligands, or construct re-engineering [43] [42].

Integrated Quality Control Workflow for Protein Crystallization

Successful protein crystallization requires a multi-faceted quality control approach. The following workflow illustrates how these techniques integrate to assess sample quality:

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Quality Control

The following reagents are essential for implementing these quality control techniques in protein crystallization pipelines:

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms crosslinked gel matrix for protein separation | Use fresh solutions; concentration determines separation range (8-15% common) [41] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge | Critical for proper migration; ensure adequate concentration in sample buffer [39] |

| DTT/β-mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents break disulfide bonds | Prevents protein aggregation; essential for complete denaturation [39] [41] |

| TEMED/Ammonium Persulfate | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization | TEMED concentration affects polymerization rate; prepare fresh APS [41] |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Binds hydrophobic patches of denaturing proteins | Used in thermal shift assays; concentration affects signal intensity [43] |

| SEC Matrices | Size-based separation media (e.g., Sephadex, Superdex) | Choose appropriate pore size for target protein; maintain properly [42] |

| Coomassie Staining Solution | Visualizes proteins in polyacrylamide gels | Prepare fresh or use commercial formulations; destain adequately for clarity [41] |

Implementing these troubleshooting guidelines for SDS-PAGE, DLS, SEC, and Thermal Shift Assays will significantly improve protein sample quality assessment. Systematic quality control at each stage of protein preparation directly enhances crystallization success rates by ensuring samples have the requisite purity, monodispersity, and stability for forming well-ordered crystal lattices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does codon optimization directly impact my protein yield and quality for crystallization? Codon optimization directly enhances protein yield and quality by matching the codon usage of your gene to the preferences of your expression host. This increases the speed and accuracy of translation, leading to higher levels of properly folded protein, which is a prerequisite for crystallization. Poor codon usage can cause ribosomal stalling, translation errors, and protein misfolding, all of which introduce heterogeneity that prevents the formation of a well-ordered crystal lattice [44]. The effectiveness of optimization can be measured by the Codon Adaptation Index (CAI); a CAI closer to 1.0 indicates a higher probability of successful expression [44].

FAQ 2: My protein expresses well but remains insoluble. Can codon optimization help? While the primary cause of insolubility often lies with the protein itself, codon optimization can be an indirect solution. Very rapid translation caused by a mismatch in codon usage can lead to misfolding and aggregation. By optimizing codons, you facilitate a slower, more controlled translation rate that allows the protein to fold correctly, thereby improving solubility. Furthermore, optimization tools can reduce high GC content and repetitive sequences in the DNA, which also contribute to synthesis and expression problems [44].

FAQ 3: Why is my purified heme protein inactive and unsuitable for crystallization, even though it appears pure? This is a classic symptom of incomplete or incorrect co-factor incorporation. Without the proper heme co-factor, the protein is not in its native, stable conformation. This conformational heterogeneity prevents the uniform molecular packing required for crystallization. Simply expressing the apoprotein in a standard lab strain like E. coli BL21 does not guarantee proper heme incorporation, as these strains may not efficiently take up or process heme [45].

FAQ 4: What are the first steps to troubleshoot failed crystallization after seemingly successful purification? Your first steps should be to rigorously reassess sample quality. Key checks include:

- Purity: Verify >95% purity via SDS-PAGE [1].

- Homogeneity: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) or Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to confirm the sample is monodisperse (non-aggregated) [46] [1].

- Stability: Perform a thermal shift assay to ensure the protein is stable across a range of conditions [46].

- Identity: Confirm you have crystallized the target protein and not a common contaminant (e.g., E. coli YodA) by checking lattice parameters against known contaminants [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Protein Yield in Heterologous Expression

Potential Cause: Suboptimal codon usage in the gene sequence for the chosen expression host.

Solution: Perform Codon Optimization. Codon optimization is a computational process that substitutes rare codons in your gene sequence with the host organism's preferred codons for the same amino acid, without changing the resulting protein sequence [44] [47].