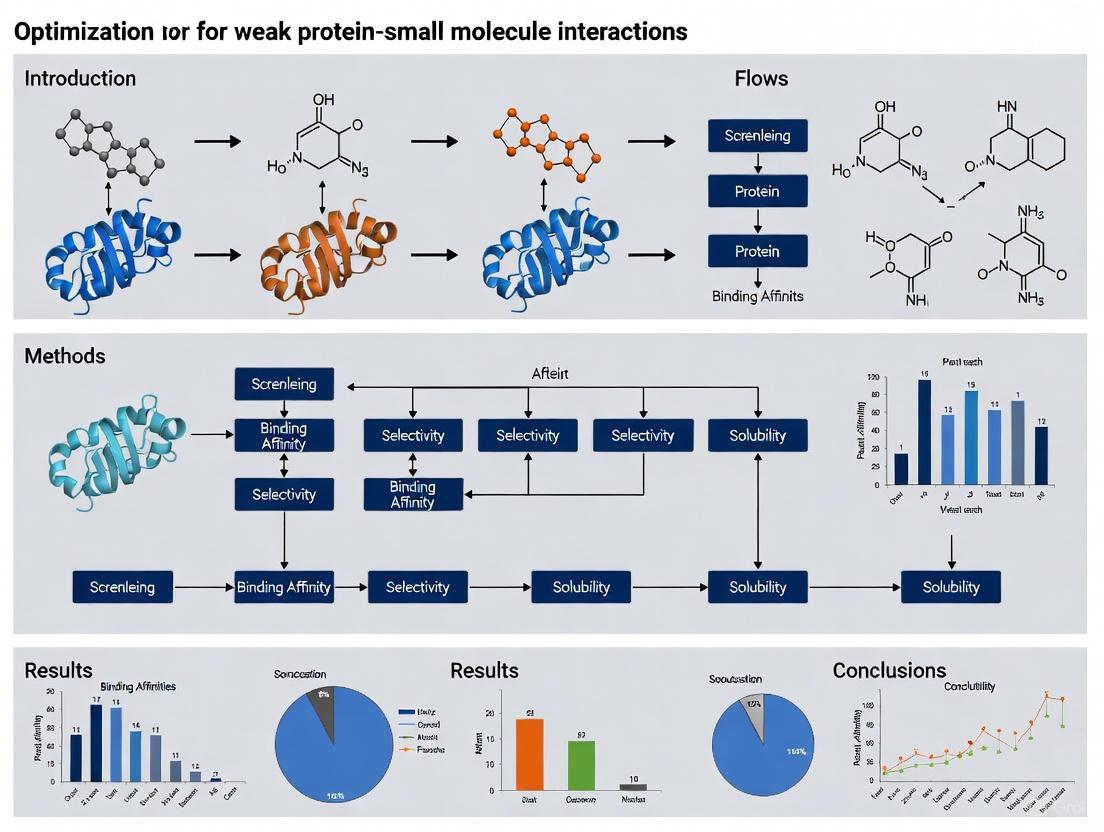

Optimizing Weak Protein-Small Molecule Interactions: Strategies for Challenges, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Weak protein-small molecule interactions (KD > 10⁻⁴ M) are increasingly recognized as crucial regulators of biochemical pathways, allosteric regulation, and signaling cascades, yet they present significant challenges for characterization and...

Optimizing Weak Protein-Small Molecule Interactions: Strategies for Challenges, Methods, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

Weak protein-small molecule interactions (KD > 10⁻⁴ M) are increasingly recognized as crucial regulators of biochemical pathways, allosteric regulation, and signaling cascades, yet they present significant challenges for characterization and optimization in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of this domain, covering the foundational principles of weak interactions and their biological significance. It delves into advanced methodological approaches, including explicit solvent alchemical free-energy calculations, affinity selection mass spectrometry (AS-MS), and integrative computational frameworks for predicting binding affinity. The content further addresses troubleshooting and optimization strategies, such as charge optimization and entropy-enthalpy compensation, and concludes with a comparative analysis of validation techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge and emerging trends to equip scientists with the strategies needed to transform these challenging interactions into therapeutic opportunities.

Understanding Weak Protein-Ligand Interactions: Biological Significance and Fundamental Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What defines a weak or transient protein-protein interaction (PPI)?

Weak and transient PPIs are characterized by their low binding affinity and short lifespan. They typically have dissociation constants (KD) in the micromolar (μM) range (e.g., >1 μM) and lifetimes of seconds or less [1]. Despite their fleeting nature, they are evolutionarily conserved and crucial for processes like signal transduction, protein trafficking, and pathogen-host interactions [2] [1].

2. Why are these interactions so challenging to study with conventional methods?

Traditional methods like co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) or tandem affinity purification-mass spectrometry (TAP-MS) involve washing steps that dissociate weak complexes [3] [1]. This leads to a significant loss of transient interactors, creating a bias towards stable, high-affinity complexes in the data [1].

3. What are the key methodological strategies for capturing weak/transient interactions?

The main strategies involve stabilizing the interaction to prevent dissociation during analysis. This can be achieved through:

- Proximity Labeling (PL): Using enzymes like PafA to covalently tag neighboring proteins, allowing for subsequent stringent purification [3].

- Crosslinking: Chemically "freezing" the interaction, though this can disrupt the native protein state and prevents kinetic studies [1].

- Single-Molecule Analysis: Using tools like Depixus MAGNA One to observe individual interactions in real-time without purification, thus capturing their dynamic nature [1].

4. Can you provide a quantitative overview of affinity ranges?

The table below summarizes the binding affinities from a model system used to benchmark the APPLE-MS method, illustrating what constitutes a weak interaction [3].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Affinity Ranges for a Model Protein-Peptide Interaction [3]

| Peptide | Equilibrium Dissociation Constant (KD) | Interaction Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide 1 | 3.7 μM | Medium-to-Weak |

| Peptide 2 | 76 μM | Weak |

| Peptide 3 | >1,000 μM | Very Weak / Non-detectable by some methods |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Failure to detect known weak interactors in an AP-MS experiment.

This is a common issue where labile complexes fall apart during the experimental workflow.

- Potential Cause 1: Overly Stringent Washes. Stringent washing, while reducing non-specific binding, can also remove genuine weak interactors [3].

- Solution: Optimize wash buffer stringency (e.g., salt concentration, detergent). Consider switching to a method that covalently captures interactions, like proximity labeling (e.g., APPLE-MS) [3].

- Potential Cause 2: Detergent-Induced Dissociation. Using harsh detergents for membrane protein extraction can dissociate a large percentage of interacting partners [3].

- Solution: Screen for milder detergents or alternative solubilizing agents to better preserve native complexes [3].

Problem: Inconsistent results between operators in AP-MS.

Small variations in protocol execution can significantly impact outcomes, especially for dynamic interactions [3].

- Solution: Implement a highly standardized and, if possible, automated protocol to minimize operator-dependent variables [4] [3].

Problem: Method only provides a static snapshot and lacks kinetic data.

Techniques like crosslinking or standard PL-MS confirm an interaction occurred but not its dynamics [1].

- Solution: Employ real-time, single-molecule analysis platforms (e.g., Depixus MAGNA One) to measure binding kinetics (on/off rates) and interaction durations directly [1].

Experimental Protocols

This section details a modern protocol designed to overcome the limitations of traditional AP-MS for weak and transient complexes.

Protocol: APPLE-MS (Affinity Purification Coupled Proximity Labeling-Mass Spectrometry)

APPLE-MS combines the specificity of affinity purification with the covalent capture capability of proximity labeling to map weak and transient PPIs in native contexts [3].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for the APPLE-MS Protocol [3]

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Twin-Strep Tag | A high-affinity epitope tag fused to the bait protein, enabling efficient capture by streptavidin. |

| PafA Enzyme | A bacterial enzyme that catalyzes the ATP-dependent covalent attachment of PupE to lysine residues on proximal proteins. |

| SA-PupE (Streptavidin-PupE) | A fusion protein that serves as the substrate for PafA. The PupE moiety is ligated to nearby proteins, and the streptavidin moiety allows for purification. |

| Streptavidin Beads | Used to purify the bait protein (via Twin-Strep tag) and any prey proteins covalently labeled with SA-PupE. |

2. Detailed Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated APPLE-MS workflow for capturing stable and transient interactions.

Step-by-Step Explanation:

- Express the Bait Protein: Genetically fuse a Twin-Strep tag to your protein of interest (bait) and express it in the relevant cellular system (e.g., HEK293T cells) [3].

- Form Native Complexes: Allow the bait protein to interact with its native binding partners (prey proteins) within the cell. This includes both stable and transient complexes [3].

- Initiate Proximity Labeling: Add the PafA enzyme and the SA-PupE substrate to the cells. PafA uses ATP to covalently attach the PupE part of SA-PupE to lysine side chains on proteins that are in close proximity to the bait. This step "marks" the interactors, however transient [3].

- Cell Lysis and Purification: Lyse the cells and perform affinity purification using streptavidin beads. The beads capture: a) the bait protein directly via its Twin-Strep tag, and b) any prey proteins that were covalently labeled with SA-PupE. Stringent washing can now be applied to remove non-specific binders without losing the covalently tagged interactors [3].

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Elute and process the purified proteins for analysis by mass spectrometry to identify the high-confidence interactors of the bait protein [3].

Method Comparison & Selection Guide

Choosing the right method depends on the biological question and the nature of the interaction. The diagram below outlines the logical decision process for method selection.

Key Takeaways:

- Know Your Method's Limits: Standard AP-MS is effective for stable complexes but fails for many biologically critical transient interactions [1].

- Embrace Integrated Methods: Techniques like APPLE-MS demonstrate that combining purification with covalent capture (proximity labeling) significantly improves sensitivity for weak interactors [3].

- Aim for Dynamics: For a complete understanding, especially in drug discovery, moving beyond simple identification to measuring interaction kinetics is essential [1].

FAQs: Understanding Weak Protein Interactions

FAQ 1: What exactly constitutes a "weak" protein interaction, and why are they important?

Weak protein interactions are generally defined as complexes with dissociation constants (KD) in the micromolar range ( >1μM) or those with fast kinetic off-rates (half-lives <0.1 s) [5]. Despite being transient, they are biologically essential. Their sensitivity to environmental changes allows them to fine-tune critical processes such as receptor signal transduction, immune discrimination, enzyme turnover, and stress adaptation mechanisms [5]. Their transient nature is a feature, not a bug, enabling rapid response to cellular cues.

FAQ 2: What are the major technical challenges in studying these weak complexes?

The primary challenge is reconstituting and maintaining stable complexes for structural analysis [5]. Specific difficulties vary by technique:

- X-ray Crystallography: Harsh crystallization conditions (e.g., high salt, acidic pH) can further diminish already weak affinity. One binding partner may dissociate and crystallize alone [5].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Samples are diluted to low concentrations for grid preparation, which can cause low-affinity complexes to dissociate before they are frozen [5].

- General Pitfalls: Weak interactions are highly susceptible to being masked by non-specific, spurious interactions that can be stronger than the physiologically relevant one. Furthermore, they can be dependent on molecular crowding effects that are difficult to reproduce in vitro [6].

FAQ 3: A crystal structure shows a weak interaction between two protein domains. How can I be sure it's biologically relevant and not a crystallization artifact?

This is a critical consideration. A few key steps for validation are:

- Mutational Analysis: Introduce point mutations at the putative interface and test whether they disrupt the interaction in vitro and the biological function in vivo.

- Biophysical Corroboration: Use solution-based techniques like NMR or FRET to confirm the interaction occurs independently of crystal packing forces.

- Conservation Analysis: Check if the interacting residues are evolutionarily conserved, which suggests functional importance [6]. Always interpret crystal structures of weak complexes with caution, as the crystal lattice can sometimes stabilize irrelevant protein-protein contacts [6].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Challenges

Problem: Complex Dissociates During Structural Biology Sample Preparation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Low local concentration and fast off-rate.

- Solution: Employ single-chain fusion constructs. Genetically fuse your two protein partners with a flexible linker (e.g., a (GGGGS)3 sequence). This drastically increases the local concentration of the binding partners, favoring complex formation [5].

- Protocol:

- Genetically fuse the genes for Protein A and Protein B into a single open reading frame, connected by a flexible linker.

- Optimize linker length and attachment points (N- or C-terminus) based on any available structural information.

- Express the single-chain protein and purify the complex.

- Considerations: Without prior knowledge of the binding mode, optimizing linker length and position may require trial and error. The linker could potentially sterically block functionally important sites [5].

Cause 2: Lack of a covalent tether to trap the transient complex.

- Solution: Implement site-specific crosslinking, such as disulfide trapping [5].

- Protocol:

- Analyze the binding interface to identify pairs of residues that are spatially close (often using computational modeling).

- Mutate these residues to cysteines, one on each binding partner.

- Co-incubate the cysteine mutants under oxidizing conditions to promote the formation of a stabilizing intermolecular disulfide bond.

- Purify the covalently stabilized complex for structural studies.

- Considerations: This method works best for extracellular proteins or engineered systems without free cysteines that could form non-specific crosslinks. Screening multiple cysteine pairs is often necessary to find one that efficiently forms the crosslink without distorting the native binding geometry [5].

Problem: Inconsistent or No Binding Detected in Solution-Based Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: The weak interaction is masked by a stronger, non-specific interaction.

- Solution: Be vigilant for promiscuous binding regions. A common example is polybasic sequences that can bind non-specifically to other proteins in the absence of their native targets, such as membranes [6].

- Protocol:

- Identify and characterize potential promiscuous domains (e.g., by sequence analysis).

- Perform binding experiments in the presence of the native binding partner (e.g., including lipids or membrane mimics if the protein normally interacts with a membrane).

- Use control proteins or peptides to account for non-specific electrostatic or hydrophobic interactions.

Cause 2: The assay conditions do not reflect the native environment.

- Solution: Include crucial co-factors or membranes. Weak binding between soluble protein domains can be significantly strengthened by cooperativity with protein-lipid interactions or by the confined space between two membranes [6].

- Protocol: Reconstitute the experiment in a more physiologically relevant context. This could involve using lipid nanodiscs, supported lipid bilayers, or full vesicle fusion assays to provide the native environment that stabilizes the metastable intermediate state.

Cause 3: General experimental error or improper storage.

- Solution: Meticulously check your experiment setup [7].

- Protocol:

- Analyze all elements: Check reagents and supplies for expiration or degradation. Confirm equipment is properly calibrated.

- Re-run with new supplies: If budget allows, repeat the experiment with fresh, quality-controlled reagents.

- Consult colleagues: Review your experimental design and data with peers to identify potential oversights [7].

Experimental Strategy & Methodology Table

The table below summarizes the core molecular engineering strategies for stabilizing weak protein complexes, detailing their applications and key methodological points.

| Strategy | Core Principle | Ideal Application | Key Methodological Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Chain Fusions [5] | Genetically link partners to enforce proximity and high local concentration. | Stabilizing complexes for crystallography, cryo-EM, or NMR [5]. | Linker length and attachment point (N-/C-terminus) are critical and may require optimization. |

| Disulfide Trapping [5] | Introduce covalent disulfide bonds at the binding interface via engineered cysteines. | Studying extracellular protein complexes, receptor-ligand interactions (e.g., GPCRs) [5]. | Requires screening of multiple cysteine pairs; works best in environments without interfering free cysteines. |

| Evolution-Guided Stabilization [8] | Use natural sequence diversity to guide mutations that improve stability without compromising function. | Optimizing protein stability for higher expression yields or therapeutic development [8]. | Relies on the availability of multiple sequence alignments for the protein family of interest. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Flexible (GGGGS)n Linker | The canonical linker for constructing single-chain fusion proteins. Provides flexibility and solubility to connected domains, allowing them to adopt native binding modes [5]. |

| Oxidizing Buffers (e.g., CuSO4, Glutathione) | Used in disulfide trapping experiments to promote the formation of covalent disulfide bonds between engineered cysteine residues [5]. |

| Membrane Mimetics (Nanodiscs, Liposomes) | Crucial for reconstituting weak protein interactions that depend on a lipid bilayer for stability, providing a more native environment than solution-based assays [6]. |

| Stability-Design Software (e.g., Rosetta) | Computational tools that can suggest mutations to increase protein stability, which is often a prerequisite for studying weak interactions, as it prevents misfolding and increases functional protein yield [8]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate stabilization strategy based on your experimental system and goals.

Troubleshooting Data Interpretation

The final diagram maps common experimental symptoms to their potential root causes and direct solutions, providing a quick-reference guide for troubleshooting.

Core Concepts: Understanding the Systems

1.1 What is the fundamental definition of allosteric regulation? Allosteric regulation is a widespread mechanism of control where an effector binds to a site on an enzyme or receptor distinct from the active site (the orthosteric site), resulting in a conformational change that alters the protein's activity [9] [10]. Effectors that enhance activity are allosteric activators, while those that decrease it are allosteric inhibitors [9].

1.2 How does allosteric regulation differ from competitive inhibition? The key difference lies in the binding site and mechanism [9].

- Orthosteric (Competitive) Inhibitors: Bind directly to the enzyme's active site, physically blocking the substrate. Their effect can be overcome by increasing substrate concentration [9].

- Allosteric Inhibitors: Bind to a separate allosteric site, inducing a conformational change that reduces the enzyme's affinity for its substrate or its catalytic efficiency. This is often non-competitive inhibition, meaning their effect is not reversed by high substrate concentration [9].

1.3 What are the primary models describing allosteric regulation? Three key models are:

- Concerted (MWC) Model: Postulates that protein subunits are connected and must all exist in the same conformation, either tensed (T) or relaxed (R). Effectors shift the equilibrium between these states [9].

- Sequential (KNF) Model: Suggests that subunit conformation changes are sequential and not necessarily identical. Substrate binding induces a conformational change in one subunit that makes adjacent subunits more receptive to substrate [9].

- Morpheein Model: A dissociative model where functionally different, alternate homo-oligomeric structures can interconvert via oligomer dissociation, conformational change, and reassembly [9].

1.4 How are signaling cascades and multi-enzyme complexes related to allostery? Long-range allostery is especially important in cell signaling [9]. Multi-enzyme complexes, such as those in metabolic pathways, often use allosteric regulation for efficient feedback control, where the end-product of a pathway acts as an allosteric inhibitor of an enzyme at the pathway's beginning [9] [10].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

2.1 My Co-IP/pulldown experiment shows no interaction. What could be wrong?

- Cause: The tagged bait protein may have been degraded.

- Solution: Ensure protease inhibitors are included in the lysis buffer [11].

- Cause: The fusion protein was improperly cloned.

- Solution: Confirm the proper cloning of the fusion protein into the expression vector [11].

- Cause: The interaction is transient or weak.

- Solution: Use more lysate for the pulldown or employ a more sensitive detection system [11]. Consider adding crosslinkers to "freeze" transient interactions [11].

2.2 I am getting a high background or false positives in my Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) screen.

- Cause: The bait protein self-activates the reporter gene.

- Solution: Subclone segments of the bait to identify a construct that does not self-activate and retest. Titrate the system using 3-AT (3-amino-1,2,4-triazole) to suppress background growth [11].

- Cause: Inadequate replica cleaning during the screening process.

- Solution: Replica clean immediately after replica plating and again after 24 hours of incubation. Ensure the plate contains no remaining visible cells after cleaning [11].

2.3 My allosteric effector does not produce the expected effect in a kinetic assay.

- Cause: The system may not follow a simple two-state model.

- Solution: Consider characterizing the system as a K-type (changes in ligand affinity) or V-type (changes in catalytic rate) allosteric system. Perform titrations of the effector over a range of substrate concentrations to quantify the allosteric coupling constant [12].

- Cause: The protein ensemble or dynamics are not favorable for the allosteric mechanism under your experimental conditions.

- Solution: Investigate the impact of solution conditions like pH, temperature, or buffer composition on the allosteric response [12].

2.4 How can I confirm a protein-small molecule interaction is direct and allosteric?

- Solution: Use a combination of techniques. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) can label-freely measure the heat of binding, providing thermodynamic parameters [13]. Structural techniques like Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) can detect large conformational changes upon binding at nanometer resolution [13]. A confirmed allosteric interaction will show binding at a site distinct from the active site and induce a functional or conformational change [9] [12].

Essential Methodologies & Protocols

Probing Allosteric Binding and Conformational Change

Protocol: Detecting Allosteric Modulation via Fluorescence Polarization (FP)

- Principle: FP measures the change in rotational speed of a small fluorescently-labeled molecule when bound to a larger protein. An allosteric effector that alters the protein's affinity for the labeled ligand will cause a change in polarization.

- Workflow:

- Labeling: Tag a substrate or orthosteric ligand with a fluorophore.

- Equilibration: Incubate the labeled ligand with your target protein.

- Effector Titration: Titrate in the unlabeled allosteric effector.

- Measurement: Read polarization (in mP units) after each addition. A change indicates the effector is modulating ligand binding.

- Applications: Ideal for high-throughput screening of allosteric modulators and studying binding affinity (K-type allostery) [13].

- Limitations: Requires a fluorescent label, which might alter ligand properties [13].

Protocol: Characterizing Allosteric Thermodynamics via Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

- Principle: ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event, providing a label-free measurement of binding affinity (K~d~), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS).

- Workflow:

- Preparation: Load the protein solution into the sample cell and the ligand/effector solution into the syringe.

- Titration: Inject the ligand/effector into the protein solution in a series of injections.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the heat from each injection and fit the data to a binding model. To study allostery, perform experiments in the absence and presence of a saturating concentration of a second ligand [12].

- Applications: Definitive method for quantifying the thermodynamic driving forces of allosteric coupling [13].

- Limitations: Requires a significant heat change upon binding and consumes relatively large amounts of protein [13].

Quantitative Data on Allosteric Systems

Table 1: Key Allosteric Proteins and Their Regulatory Characteristics

| Protein | Allosteric Regulator | Type of Regulation | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | O~2~, CO~2~, 2,3-BPG | K-type (Homotropic & Heterotropic) | Oxygen Transport [9] [12] |

| Phosphofructokinase (PFK) | ATP (Inhibitor), ADP/AMP (Activators) | K-type (Heterotropic) | Glycolysis [9] [12] |

| Pyruvate Kinase | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (Activator) | V-type & K-type | Glycolysis [12] |

| c-Myc/Max | Small-molecule inhibitors (e.g., 10074-G5) | Protein-Protein Interaction Inhibitor | Transcription & Cancer [13] |

| Calmodulin | Ca^2+^ | K-type (Activator) | Calcium Signaling [12] |

Table 2: Techniques for Probing Weak Protein-Small Molecule Interactions

| Technique | Applicability | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Polarization (FP) | Modulators of protein-protein/ligand interactions | High | Requires fluorescent labels [13] |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Label-free measurement of binding thermodynamics | Medium-Low | High protein consumption; requires significant heat change [13] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Real-time detection of binding kinetics and affinity | Medium | Surface immobilization can cause non-specific binding [13] |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | Detection of large conformational changes | Variable | Low resolution [13] |

| Yeast Two-Hybrid (Y2H) | Detection of modulators of protein-protein interactions | High | Indirectly quantitative; potential for false positives [11] [13] |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Allosteric Regulation Models

Allosteric Inhibitor Screening Workflow

Signaling Cascade with Allosteric Node

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Allosteric Regulation

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Crosslinkers (e.g., DSS, BS3) | "Freeze" transient protein-protein interactions inside (DSS) or outside (BS3) the cell for Co-IP or pulldown assays [11]. | Capturing weak or transient complexes in allosteric multi-enzyme complexes [11]. |

| 3-Amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) | Competitive inhibitor of the HIS3 gene product used to suppress bait autoactivation in Yeast Two-Hybrid screens [11]. | Titrating the stringency of a Y2H screen to identify true allosteric protein-protein interaction disruptors [11]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent degradation of the target protein and its interaction partners during cell lysis and purification [11]. | Essential for maintaining protein integrity in Co-IP, pulldown, and enzyme activity assays [11]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes & Substrates | Enable detection and quantification in assays like Fluorescence Polarization (FP) and FRET [13]. | Labeling substrates or ligands to monitor allosteric modulation of binding affinity [13]. |

| Tag-Specific Affinity Resins | Immobilize bait proteins for pulldown assays (e.g., GST-, His-, or antibody-conjugated beads) [11]. | Isolating multi-enzyme complexes or protein-ligand complexes for downstream analysis [11]. |

FAQs: Understanding the Core Concepts

Q1: What is the "Local Concentration Effect" and why is it critical for cellular function?

The Local Concentration Effect describes how the confinement of proteins and other molecules within specific subcellular compartments drastically increases their effective local concentration. This compartmentalization is essential because it creates unique microenvironments with distinct molecular compositions, chemical properties, and physical attributes. These niches drive discrete biological processes by ensuring that the right proteins and ligands are in the right place at the right time to interact. For instance, signaling, growth, proliferation, motility, and programmed cell death all require dynamic protein movements between cell compartments. This organization is not static; proteins can localize to multiple locations, reflecting "moonlighting" activities, and their distribution can change in response to cellular conditions [14]. Aberrant protein localization is linked to a wide range of diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders, underscoring the functional importance of this effect [14].

Q2: How can improper protein localization disrupt weak protein-small molecule interactions?

Improper protein localization can severely disrupt weak interactions by physically separating the protein from its intended small molecule partner. A study on engineered mutant ribose-binding proteins (RbsB) in E. coli provides a clear example. These mutants, designed to bind a new ligand (1,3-cyclohexanediol), exhibited defects in their translocation to the periplasm. Instead of localizing correctly, they showed mislocalization, autoaggregation, and high cell-to-cell variability. This incorrect positioning meant the proteins were not in the proper cellular context to interact effectively with membrane receptors, leading to poor sensing performance. This demonstrates that computational design of a ligand-binding pocket is insufficient; the protein must also be correctly localized to function [15].

Q3: What are the major technical challenges in studying weak protein-small molecule interactions within subcellular compartments?

Studying these weak interactions (often with dissociation constants, Kd > 10 μM) presents several specific challenges [6]:

- Membrane-Dependent Complexes: The release machinery is often assembled between two membranes, making it difficult to reconstitute and study in vitro.

- Technical Promiscuity: Highly charged protein sequences (e.g., polybasic regions) can mediate strong but biologically irrelevant interactions with other proteins in solution if their native membrane targets are absent.

- Crystallography Limitations: Weak interactions that help form a crystal lattice can be mistaken for biologically relevant complexes.

- Characterization Difficulties: Techniques like isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) can be confounded by heat contributions from non-specific interactions, leading to misinterpretation of data.

- Dynamic Nature: These interactions are highly dynamic and may depend on molecular crowding effects within the cell, which are difficult to reproduce in a test tube.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q4: My experiment shows a weak or absent signal for a protein-small molecule interaction. What should I check?

Use the following flowchart to systematically diagnose the issue.

Q5: How can I validate that an observed weak interaction is biologically relevant and not an experimental artifact?

To ensure biological relevance, consider these strategies [6]:

- Include Membranes: Since many weak interactions are stabilized by co-localization on membranes, perform assays in the presence of relevant lipid bilayers rather than solely in solution.

- Mutational Analysis: Introduce point mutations into the suspected binding pocket. If the interaction is specific, these mutations should diminish or abolish binding.

- Competition Experiments: Use unlabeled ligands or known inhibitors to compete for binding, which should reduce the signal.

- Correlate with Function: Link the interaction to a functional output. If perturbing the interaction disrupts the expected cellular function, it is more likely to be relevant.

- Orthogonal Methods: Confirm the interaction using a different, unrelated technical approach (e.g., combine ITC with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)).

Key Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Subcellular Fractionation for Organellar Proteomics

This protocol outlines a method to isolate subcellular compartments, allowing for the study of protein localization and organelle-specific interactions [14].

Principle: Cellular fractionation exploits differences in the physical properties of organelles (size, mass, density) to separate them from a crude cell lysate, typically using centrifugation techniques.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Cell Lysis and Homogenization: Gently disrupt cells using a method appropriate for your sample. For cultured mammalian cells, a Dounce homogenizer is often suitable. This step aims to release intact organelles while minimizing their breakage [14].

- Differential Centrifugation: Subject the homogenate to a series of centrifugations at increasing speeds. This will pellet out different organelle fractions based on their size and density (e.g., nuclei at low speed, mitochondria at intermediate speed) [14].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: For higher purity, resuspend the crude pellet and layer it onto a density gradient medium (e.g., Sucrose, Percoll, or Iodixanol). During ultracentrifugation, organelles will migrate to the point in the gradient that matches their own buoyant density [14].

- Fraction Collection: Carefully collect the distinct bands from the gradient, which correspond to enriched organelle fractions.

- Validation and Analysis: Validate the purity of your fractions using Western blotting with antibodies against known organelle markers (e.g., LAMP1 for lysosomes, COX IV for mitochondria). The proteins in each fraction can then be identified and quantified using mass spectrometry (MS) to generate a subcellular proteome map [14].

Protocol: Determining Subcellular Localization of Protein Interactions

This protocol uses fluorescent protein fusions and pulse-chase labeling to visualize protein localization and measure turnover in live cells [16].

Principle: A protein of interest is fused to a self-labeling tag (e.g., SNAP-tag). A fluorescent substrate is then used in a "pulse" to label the protein pool synthesized within a specific time window. Its localization and disappearance ("chase") are tracked over time to determine both location and stability.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Cell Transfection: Transfect cells (e.g., HeLa) with a plasmid encoding your protein of interest fused to the SNAP-tag. A GFP plasmid can be co-transfected to identify successfully transfected cells [16].

- Blocking: To synchronize the protein population, incubate cells with SNAP-Cell Block. This blocks all SNAP-tag molecules produced before this step, ensuring a clean baseline [16].

- Pulse-labeling: Replace the block with a medium containing a fluorescent SNAP-substrate (e.g., SNAP-Cell TMR-Star). This will label all SNAP-tag molecules synthesized during this pulse period [16].

- Chase and Imaging: Remove the pulse medium and "chase" the cells in a medium containing SNAP-Cell Block to prevent new labeling. Image the cells at multiple time points after the pulse (e.g., 0 h, 4 h, 8 h, 24 h) to track the loss of fluorescence as the labeled proteins are degraded [16].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity at each time point. The protein's half-life can be calculated by fitting the fluorescence decay curve to an exponential function. Simultaneously, the subcellular localization is directly visualized throughout the experiment [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 1: Key Reagents for Studying Compartmentalized Interactions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| SNAP-tag [16] | A self-labeling protein tag that covalently binds to fluorescent O6-benzylguanine (BG) derivatives. | Pulse-chase imaging to measure protein turnover and visualize subcellular localization in live cells. |

| Density Gradient Media (Sucrose, Iodixanol, Percoll) [14] | Inert materials used to create density gradients for separating organelles based on their buoyant density during centrifugation. | Purification of specific organelles (e.g., mitochondria, lysosomes) for subsequent proteomic or interaction studies. |

| Proximity Labeling Enzymes (e.g., BioID, APEX) [14] | Enzymes that, upon activation, biotinylate proteins in their immediate vicinity. | Identifying the proteome of a specific organelle or protein neighborhood, even for weak or transient interactions. |

| Chemically Induced Dimerization (CID) Systems (e.g., FKBP/FRB with Rapamycin) [17] | A tool that uses a small molecule (e.g., Rapamycin) to rapidly and reversibly bring two engineered proteins together. | Acute manipulation of protein localization to test the effect of local concentration on activity, as shown for PKA-R. |

| Computational Prediction Tools (e.g., LABind) [18] | A structure-based method using machine learning to predict protein binding sites for small molecules and ions in a ligand-aware manner. | Predicting binding sites for novel ligands and prioritizing residues for mutational analysis to test interaction hypotheses. |

Advanced Techniques: Computational & Functional Analysis

Using Computational Tools to Predict Binding Sites

The LABind method represents a recent advancement in predicting protein-ligand binding sites. It is particularly useful because it can generalize to "unseen" ligands not present in its training data. LABind works by [18]:

- Input: Taking the protein's structure and the ligand's SMILES string (a text-based representation of a molecule's structure).

- Processing: Using a graph transformer to capture the protein's structural context and a cross-attention mechanism to learn the specific binding characteristics between the protein and the ligand.

- Output: Predicting which protein residues are part of the binding site for that specific ligand. This tool can be used to guide experimental work, such as designing mutants or optimizing molecular docking tasks [18].

Case Study: How Localization Modulates Protein Kinase A (PKA) Activity

Research using the FKBP/FRB translocation system revealed a paradoxical role for the PKA Regulatory subunit (PKA-R). Artificially recruiting PKA-R to the plasma membrane did not simply inhibit the kinase, as its traditional role would suggest. Instead, it had a dual effect: at lower translocation levels, it enhanced membrane kinase activity, while at higher levels, it was inhibitory. This demonstrates that the localization of a regulatory subunit can act as a concentration-dependent linker, capable of both coupling and decoupling signaling processes. This complex effect can explain seemingly contradictory roles of PKA in processes like cell migration [17].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What makes weak, transient protein-protein interactions (PPIs) so difficult to study compared to stable complexes? Weak, transient PPIs are characterized by low binding affinities (often with micromolar dissociation constants) and short lifetimes (seconds or less). Their dynamic and context-dependent nature means they are easily disrupted during standard laboratory techniques like washing steps in co-immunoprecipitation, making them elusive targets for detection and characterization [1].

FAQ 2: My high-throughput screening (HTS) for a PPI modulator failed to identify good leads. What alternative approaches should I consider? Traditional HTS can struggle with the flat, featureless binding interfaces common in PPIs [19]. Consider shifting to:

- Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): Uses smaller, low molecular weight fragments that are better at binding to the discontinuous "hot spots" on a PPI interface [19].

- Virtual Screening: Leverages computational models to screen large compound libraries in silico before laboratory testing. This can be structure-based (using protein structure) or ligand-based (using known inhibitor data) [19].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the predictive accuracy of my computational models for protein-ligand interactions? Integrate multiple data types into your model. A recent study on METTL3 inhibitors showed that combining conventional chemical features with Docking-based Protein-Ligand Interaction Features (DPLIFE) significantly improved bioactivity prediction. This method encodes interaction profiles (e.g., hydrophobic contacts, hydrogen bonds) for key protein residues, seamlessly marrying machine learning prediction with structural biology insights [20].

FAQ 4: What are the main limitations of current experimental methods for detecting transient PPIs? The table below summarizes the core limitations of common techniques [1]:

| Method | Can Detect Transient PPIs? | Provides Dynamic Info? | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-immunoprecipitation | Partially | No | Biased toward stable interactions; false positives/negatives [1]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (e.g., TAP-MS) | Sometimes | No | Requires stabilization; can miss weak/short-lived complexes [1]. |

| X-ray Crystallography / Cryo-EM | Rarely | No | High resolution but unsuitable for weak, dynamic complexes; limited throughput [1]. |

| Cross-linking MS | Yes | No | Captures interaction snapshots but disrupts the native state [1]. |

FAQ 5: Are there emerging technologies that can overcome the challenge of studying interaction dynamics? Yes. New technologies like Magnetic Force Spectroscopy (MFS) platforms (e.g., Depixus MAGNA One) are designed for this purpose. They enable real-time, single-molecule analysis, allowing researchers to monitor thousands of individual protein interactions simultaneously. This provides direct measurements of binding kinetics and interaction durations for even short-lived events, moving beyond the static snapshots provided by other methods [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Lead Discovery for PPI Targets

Problem: Inability to identify viable chemical starting points for modulating a difficult PPI.

| Issue | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Flat binding interface | Lack of deep pockets for small molecules to bind [19]. | Shift from HTS to FBDD. Screen low molecular weight fragments that can bind to discrete hot spots, then chemically link or expand them [19]. |

| Low hit rate in virtual screening | Over-reliance on a single computational approach [19]. | Combine structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening. Use ensemble docking or integrate pharmacophore models to improve hit enrichment [19]. |

| Difficulty optimizing stabilizers | Complex thermodynamics and lack of obvious binding sites for enhancers [19]. | Employ allosteric targeting strategies. Use HDX-MS or NMR to identify dynamic allosteric sites that, when bound, stabilize the protein complex [19]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Limitations in Characterizing Weak Interactions

Problem: Inability to reliably detect or measure the kinetics of weak protein-small molecule or transient protein-protein interactions.

Solution: Integrate complementary methods to create a more complete picture.

- Computational Prediction: Use homology-based or template-free machine learning methods (e.g., Support Vector Machines) to predict potential interaction interfaces and key residues [19].

- Targeted Experimental Validation: Employ a technique capable of capturing dynamic interactions. While Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is an option, emerging tools like Magnetic Force Spectroscopy (MFS) offer advantages by providing single-molecule resolution and the ability to detect rare events and heterogeneous binding behaviors that ensemble methods average out [1].

- Data Integration: Combine the kinetic parameters (e.g., binding constants from MFS) with structural data from X-ray crystallography or Cryo-EM to rationally design improved modulators.

The workflow below illustrates a robust strategy that combines computational and experimental biology to overcome characterization hurdles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for studying weak interactions, as featured in recent research [20].

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | An open-source tool for molecular docking, used to predict how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a protein target and to calculate binding affinities [20]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to handle chemical data, generate 3D ligand structures, and compute molecular descriptors for machine learning [20]. |

| Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) | A tool to automatically detect and characterize non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) in a 3D protein-ligand complex [20]. |

| DPLIFE Feature | A custom feature encoding method that translates PLIP interaction results into numerical data, enabling machine learning models to learn from structural interaction patterns [20]. |

| AutoGluon | An automated machine learning (AutoML) library used to build and stack multiple ML models for robust predictive tasks like bioactivity (pIC50) prediction [20]. |

Advanced Application: A Machine Learning-Enhanced Workflow for METTL3 Inhibitor Discovery

A novel study on METTL3 inhibitors provides a successful blueprint for integrating machine learning with structural biology. The following diagram details the experimental and computational workflow designed to overcome dataset limitations and build an accurate predictive model [20].

This integrated workflow successfully identified 8 key residues critical for ligand binding to METTL3, providing a structural rationale for the model's predictions and a clear path for the rational design of next-generation inhibitors [20].

Advanced Techniques for Detecting and Characterizing Weak Interactions

The study of weak, transient interactions between proteins and small molecules is fundamental to understanding biological signaling and for successful drug discovery. Such interactions, particularly those involving intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), present unique challenges due to their low binding affinity and rapid kinetics [21]. This technical resource center provides optimized strategies and troubleshooting guides for four key biophysical techniques—Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), and Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC)—to help researchers obtain reliable data for these challenging systems. A multi-method approach, combining the strengths of these complementary techniques, is often the most robust path to validating interactions and deriving accurate thermodynamic and kinetic parameters [22].

Technique Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key capabilities and requirements of each technique to help guide experimental design.

| Technique | Key Measured Parameters | Affinity Range (K_D) | Sample Consumption | Throughput | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR | Binding affinity, binding site mapping, residual structure | µM - mM [23] | Low to moderate (mg) | Low | Atomic-level resolution; ideal for disordered proteins [24] |

| ITC | Binding affinity (K_D), enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), stoichiometry (N) | nM - µM [25] | High (mg) | Low | Direct measurement of full thermodynamics; no labeling required [25] |

| SPR | Association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), affinity (K_D) | pM - mM [22] [25] | Low (µg) | High | Real-time, label-free kinetics; low sample requirement [26] [25] |

| AUC | Stoichiometry, binding affinity, hydrodynamic properties, complex shape | pM - mM [22] | Moderate (mg) | Low | First-principles method; analyzes samples in solution under native conditions [22] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

Q: What should I do if I observe no significant signal change upon analyte injection?

- Verify analyte concentration: Ensure the concentration is appropriate for the expected affinity. For weak binders, high concentrations may be needed [27].

- Check ligand immobilization: The immobilization level might be too low. Optimize coupling chemistry and density [27].

- Confirm ligand functionality: Ensure the immobilized ligand is stable and functionally active. A loss of activity post-immobilization can cause weak or no binding [27].

- Assess solvent compatibility: Running buffer must be compatible with both interaction partners. For small molecules with poor aqueous solubility, including 1-5% DMSO in the running buffer can help maintain solubility without disrupting the interaction [28].

Q: How can I address high non-specific binding (NSB) on the sensor surface?

- Implement blocking: After ligand immobilization, block the sensor surface with an inert protein like BSA or ethanolamine [27].

- Optimize regeneration: Develop a robust regeneration step to completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand. This may involve testing different pH, ionic strength, or additives [27].

- Use a different immobilization strategy: Switch to site-directed immobilization (e.g., via His-tag/Ni-NTA) to better orient the ligand and reduce exposed surface area for NSB [26] [28].

- Modify running buffer: Increase ionic strength or add a mild detergent to the running buffer to reduce electrostatic or hydrophobic non-specific interactions [27].

Q: My baseline is unstable or drifting. How can I fix it?

- Degas buffers: Always degas the running buffer thoroughly before use to eliminate micro-bubbles [27].

- Check for leaks: Inspect the fluidic system for leaks that could introduce air or cause flow instability [27].

- Ensure thermal equilibrium: Allow the instrument and samples sufficient time to equilibrate to the set temperature before starting the experiment [27].

- Use fresh buffer: Prepare fresh, filtered running buffer to avoid chemical degradation or microbial contamination [27].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Q: I am not observing a significant heat change upon titration. What could be wrong?

- Check concentration and stoichiometry: The concentration in the cell must be high enough to generate a measurable heat signal upon binding. The concentration in the syringe should typically be 10-20 times higher than the expected K_D to ensure sufficient saturation during the titration [25].

- Verify sample integrity: Ensure both the protein and small molecule are stable and active under the experimental conditions (pH, temperature, buffer).

- Consider heat of dilution: Always perform a control experiment by titrating the ligand into the buffer alone and subtract this background signal from your binding data.

Q: The data fitting is poor or the measured affinity seems inaccurate.

- Optimize the "c-value": For reliable fitting, the unitless c-value, where c = N * [M]cell * KA, should ideally be between 10 and 100. Adjust the concentrations in the cell and syringe to achieve this [25].

- Use an appropriate binding model: Do not automatically default to a single-site model. If the stoichiometry appears fractional, a two-site or other complex model may be more appropriate.

- Global fitting: For complex systems, perform global analysis by fitting multiple ITC experiments conducted at different temperatures or concentrations simultaneously using software like SEDPHAT to improve parameter precision [22].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

Q: How can I optimize the production of an Intrinsically Disordered Protein (IDP) for NMR studies?

- Choose the right expression host: Select an expression system that minimizes proteolytic degradation, a common issue with IDPs [24].

- Utilize denaturing purification: IDPs can often be purified under denaturing conditions (e.g., with urea) without the need for refolding, which can simplify handling and improve yield [24].

- Select appropriate chromatography: Use reverse-phase or ion-exchange chromatography, which can be better suited for IDPs than size-exclusion chromatography due to their extended conformations [24].

- Employ optimal NMR experiments: For IDPs, the CON experiment series (e.g., CON-IPAP) is often superior to the standard ^15^N-HSQC experiment because it avoids problems associated with poor amide proton chemical shift dispersion [24].

Q: What NMR experiments are best for detecting weak binding to a protein?

- Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP): Monitor changes in the ^1^H and ^15^N chemical shifts of the protein in a ^15^N-HSQC spectrum upon addition of the small molecule. This can identify binding sites and provide affinity estimates [21].

- Line Broadening: Weak, transient binding can cause measurable line broadening of NMR signals due to intermediate exchange on the NMR timescale [23].

- Saturation Transfer Difference (STD): This ligand-observed technique is highly effective for detecting the binding of small molecules, even with weak affinity, by selectively saturating the protein and observing the transfer of magnetization to the bound ligand [23].

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC)

Q: When studying a protein-small molecule interaction, which method—Sedimentation Velocity (SV) or Sedimentation Equilibrium (SE)—should I use?

- Use Sedimentation Velocity (SV): SV is generally preferred for interaction studies. It provides high hydrodynamic resolution to detect the number and size of coexisting complexes and can determine binding constants across a wide affinity range (pM to mM) [22]. It is also highly sensitive to changes in shape and size upon binding.

Q: How can I improve the resolution of my SV experiment for a multi-component system?

- Employ multi-signal sedimentation velocity (MSSV): By globally analyzing data from multiple detection systems (e.g., absorbance and interference), MSSV can determine the number of sedimenting species and their precise composition, which is invaluable for deconvoluting complex mixtures [22].

- Use fluorescence detection (FDS): The fluorescence detection system greatly expands the dynamic range and sensitivity of AUC, allowing studies at low nanomolar concentrations and in complex buffers, which is ideal for detecting weak interactions [22].

Experimental Protocol for a Multi-Method Analysis

Objective: To comprehensively characterize a weak interaction between a small molecule and an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP).

Rationale: No single technique can provide a complete picture of a weak, dynamic interaction. This protocol uses SPR for kinetics and low-consumption screening, ITC for thermodynamics, NMR for residue-level information, and AUC to confirm stoichiometry and complex size in solution [22] [21].

Step 1: Initial Screening and Kinetics with SPR

- Immobilize: Capture the His-tagged IDP onto a Ni-NTA sensor chip [28].

- Inject Analytes: Perform a single-cycle kinetics experiment, injecting a series of increasing concentrations of the small molecule over the captured protein surface [28].

- Control: Include a reference flow cell with no immobilized protein to correct for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding.

- Analyze: Fit the resulting sensorgrams to a 1:1 binding model to obtain the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants, and calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = koff / k_on).

Step 2: Thermodynamic Profiling with ITC

- Prepare Samples: Dialyze the IDP and the small molecule into an identical, degassed buffer.

- Load the Instrument: Place the IDP solution in the sample cell and the small molecule solution in the syringe.

- Titrate: Program a series of injections (typically 15-20) of the small molecule into the protein solution while continuously measuring the heat change.

- Analyze: Integrate the heat peaks, subtract the heat of dilution, and fit the data to an appropriate binding model to obtain K_D, stoichiometry (N), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS).

Step 3: Binding Site Mapping with NMR

- Prepare Sample: Produce ^15^N-isotopically labeled IDP. Concentrate the protein in a suitable NMR buffer [24].

- Collect Reference Spectrum: Acquire a ^15^N-HSQC or CON spectrum of the free IDP [24].

- Titrate Ligand: Add small aliquots of the small molecule to the protein sample and collect a new ^15^N-HSQC/CON spectrum after each addition.

- Analyze: Track chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) or line broadening for each residue. Residues with significant changes are likely involved in the binding interface [21].

Step 4: Solution State Validation with AUC (SV)

- Prepare Samples: Create a solution containing the IDP and small molecule at a concentration near the expected K_D.

- Run Experiment: Load the sample into a centrifuge and run at high speed (e.g., 50,000 rpm). Use absorbance or fluorescence optics to monitor the sedimentation of the species.

- Analyze: Model the sedimentation data with software like SEDPHAT. The c(s) distribution will reveal the sedimentation coefficients of the free IDP and the protein-small molecule complex, confirming complex formation and providing information about its hydrodynamic properties [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for the experiments described in this guide.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| NTA Sensor Chip | For immobilizing His-tagged proteins on SPR instruments without covalent chemistry [26] [28]. |

| Dextran Sensor Chip | A hydrogel surface for covalent immobilization (e.g., amine coupling) of proteins for SPR [28]. |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | An environmentally sensitive dye used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to monitor protein thermal unfolding [23]. |

| ^15^N-labeled NH₄Cl | Nitrogen source for bacterial growth media to produce ^15^N-isotopically labeled proteins for NMR spectroscopy [24]. |

| DMSO-d₆ | Deuterated solvent for preparing NMR samples and for locking/fielding in NMR spectroscopy. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Decision Workflow for Technique Selection

Global Multi-Method Analysis (GMMA) Concept

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in overcoming common experimental challenges in mass spectrometry-based studies of weak protein-small molecule interactions. The guides and FAQs below are framed within the broader thesis that robust method optimization is crucial for obtaining reliable data in this analytically demanding field.

Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Our HDX-MS data shows high deuterium back-exchange, compromising data quality. How can we minimize this?

A: High back-exchange is often related to suboptimal quenching or sample handling. Implement these solutions:

- Optimized Quenching: Ensure your quenching buffer is at pH 2.5 and temperature is as low as possible (<0°C). The use of a chilled aqueous solution of 0.1% formic acid is common [29].

- Reduce Processing Time: Minimize the time between quenching and MS analysis. Automated systems like the TRAJAN CHRONECT can standardize and accelerate this process [30].

- Sub-zero Chromatography: Employ LC systems with temperature zones at 0°C and -30 °C to dramatically decelerate back-exchange [29].

Q2: We are getting poor peptide sequence coverage for our protein. What steps can we take to improve it?

A: Inadequate coverage prevents regional structural analysis. Troubleshoot using the following:

- Digestion Optimization: Use immobilized pepsin columns instead of in-solution digestion for more consistent and efficient cleavage [30]. Consider testing other acidic proteases.

- Peptide Identification: Prior to HDX experiments, perform a thorough protein identification run using multiple fragmentation techniques (CID, HCD, ETD) to maximize the number of overlapping peptides [30].

- LC Performance: Ensure your nano-LC system (e.g., Vanquish Neo UHPLC) and columns (e.g., Hypersil GOLD) are delivering optimal peak separation and shape [30].

Q3: How can we distinguish between EX1 and EX2 exchange kinetics from our HDX-MS data?

A: The kinetic regime is identified by analyzing the isotopic envelopes in your mass spectra:

- EX2 Kinetics: Observed as a gradual, single shift of the isotopic distribution to higher mass. This is the most common regime for native proteins and reports on the local stability and solvent accessibility [29].

- EX1 Kinetics: Manifests as a bimodal isotopic pattern, where the population of un-exchanged molecules decreases while the fully exchanged population increases over time. This indicates cooperative unfolding events [29].

HDX-MS Experimental Protocol

Below is a detailed workflow for a standard bottom-up HDX-MS experiment.

Diagram: HDX-MS Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Buffer exchange the protein into the desired labeling buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.0). Ensure the protein is pure and stable.

- Deuterium Labeling:

- Dilute the protein sample into D₂O-based buffer (e.g., 10- to 15-fold dilution) [29].

- Incubate for multiple time points (e.g., 10 s, 1 min, 10 min, 1 h, 4 h) at a constant temperature (e.g., 25 °C) to measure exchange kinetics.

- Include a zero-time point by adding the protein to a pre-mixed buffer containing quench solution.

- Quenching:

- Proteolytic Digestion:

- Immediately pass the quenched sample over an immobilized pepsin column (e.g., at 20 °C) to digest the protein into peptides [30].

- LC-MS Analysis:

- Desalt and separate the peptides on a trap column followed by a reverse-phase UHPLC column (e.g., Hypersil GOLD) held at 0°C [30].

- Inject onto a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid). For peptide-level resolution, acquire data in full-scan MS mode. For single-residue resolution, use data-dependent ETD fragmentation to minimize deuterium scrambling [30].

- Data Analysis:

- Process data using specialized software (e.g., BioPharma Finder). Identify peptides from the undeuterated control. Measure the centroid mass of each peptide's isotopic envelope at each time point.

- Calculate deuterium uptake and plot versus time to generate uptake curves for analysis.

HDX-MS Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for HDX-MS experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Product / Composition |

|---|---|---|

| D₂O Buffer | Creates the deuterium labeling environment; backbone amide hydrogens exchange with deuterons. | 90-98% D₂O, 20 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pD 7.0 (pHread 6.6) [29] |

| Quench Buffer | Lowers pH and temperature to drastically slow exchange (minimizes back-exchange). | 100 mM Phosphate, 2 M Gu-HCl, pH 2.5, held at <0°C [29] [30] |

| Immobilized Pepsin | Acidic protease for consistent digestion under quenching conditions (pH 2.5). | TRAJAN CHRONECT system with pepsin column [30] |

| C18 LC Column | Desalting and separation of peptides prior to MS analysis. | Thermo Scientific Hypersil GOLD column [30] |

| High-Res Mass Spectrometer | Provides the high mass accuracy and resolution needed to detect small mass shifts from deuteration. | Orbitrap Exploris 480 or Orbitrap Eclipse Tribrid [30] |

Affinity Selection Mass Spectrometry (AS-MS) / Native MS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Our native MS spectra show high charge states and dissociation of weak protein-ligand complexes. How can we stabilize them?

A: High charge states can destabilize non-covalent complexes in the gas phase.

- Use Charge-Reducing Agents: Add chemical additives to your spray solution that reduce the charge of protein-ligand complexes, thereby increasing their kinetic stability in the gas phase. Recent research explores agents for both positive and negative mode MS [31].

- Optimize MS Parameters: Use softer desolvation and ionization conditions (lower source fragmentation, lower collision energies in the interface). "Native mode" instrument settings are designed for this purpose.

- Employ Buffer Exchange: Use buffer exchange into volatile ammonium acetate solutions (e.g., 100-200 mM) to remove non-volatile salts while maintaining near-physiological conditions.

Q2: Can we use Native MS to screen complex mixtures, like natural extracts, for binders?

A: Yes, this is a key application. Native MS can resolve multiple protein-ligand complexes in a single spectrum, allowing direct identification of binders from complex mixtures [31].

- Protocol: Incubate the target protein with the natural extract. Then, use buffer exchange or size-exclusion chromatography to remove unbound small molecules.

- Analysis: Introduce the purified protein-ligand mixture via nano-electrospray ionization. Observe mass shifts in the protein spectrum corresponding to the bound ligands. This approach has been used to identify novel ligands from extracts containing >5,000 compounds [31].

Q3: How does Native MS compare to other techniques for measuring weak interactions?

A: Native MS has unique advantages and limitations, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Comparison of Techniques for Studying Weak Protein-Ligand Interactions.

| Technique | Key Principle | Affinity Range (Typical) | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native AS-MS | Direct measurement of mass shift upon non-covalent binding. | Medium to Weak (µM-mM) | Can resolve multiple ligands and stoichiometries simultaneously [31]. | Requires careful gas-phase stabilization; complex data analysis for heterogeneous mixtures. |

| HDX-MS | Measures deuterium uptake into backbone amides as a proxy for solvent accessibility. | All affinities (if binding alters dynamics) | Probes binding interface and allosteric effects; no size limit [29] [30]. | Does not directly measure affinity; requires significant method optimization. |

| Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | Measures interference pattern shift on a biosensor tip upon binding. | High to Weak (pM-µM) | Label-free; provides direct kinetics (kon, koff); handles crude samples [26]. | Requires immobilization; high sample volume (~400 µL) [26]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures refractive index change on a sensor chip upon binding. | High to Weak (pM-µM) | Label-free; high-throughput capabilities; provides direct kinetics [26]. | Requires immobilization; microfluidic systems can limit association phase measurement [26]. |

Native MS Experimental Protocol for Ligand Binding

This protocol outlines the steps for detecting small molecule binding to a protein using native mass spectrometry.

Diagram: Native MS Binding Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Protein: Purify the target protein and buffer exchange it into a volatile ammonium acetate solution (e.g., 100-200 mM, pH 6-8) suitable for native MS.

- Ligand: Prepare a stock solution of the small molecule in a compatible solvent (e.g., DMSO, ensuring final concentration is <5%).

- Complex Formation:

- Mix the protein and ligand at desired molar ratios. Typical protein concentration is 5-20 µM. Use ligand in excess (e.g., 10-50x) to drive binding, especially for weak interactions.

- Incubate the mixture at a relevant temperature (e.g., room temperature or 4°C) for 15-30 minutes to reach equilibrium.

- Native MS Analysis:

- Load the sample into a gold-coated nano-ESI capillary.

- Introduce the sample into a mass spectrometer capable of high mass range and resolution (e.g., Orbitrap-based instrument or Q-TOF).

- Critical: Use instrument parameters optimized for "native MS": low declustering/cone voltage, low collision energy in the source region, and elevated pressure in the first vacuum stages to preserve non-covalent interactions.

- Data Processing and Interpretation:

- Acquire mass spectra in the appropriate m/z range to observe the charge state distribution of the protein.

- Deconvolute the raw spectrum to a zero-charge mass spectrum using the instrument's software.

- Identify the peak for the apo-protein and look for new peaks at higher masses corresponding to the protein with one or more ligands bound (Protein + n*Ligand). The mass difference reveals the ligand's mass and the peak intensity can be used for semi-quantitative analysis.

Native AS-MS Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for Native AS-MS experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Product / Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate | A volatile salt for buffer exchange; maintains protein structure without interfering with MS analysis. | 100-200 mM Ammonium Acetate, pH adjusted with NH₄OH or acetic acid |

| Charge-Reducing Agents | Chemical additives that reduce protein charge states, stabilizing weak complexes in the gas phase. | Triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) or other novel agents for negative/positive mode [31] |

| Nano-ESI Capillaries | For introducing the sample into the mass spectrometer with high efficiency and low flow rates. | Gold-coated silica capillaries |

| High-Mass Range MS | Mass spectrometer capable of detecting high m/z ions with high resolution and mass accuracy. | Q-TOF or Orbitrap-based mass spectrometer |

Structural Insights from Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) and Cryo-EM

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My cryo-EM reconstruction is at a high resolution, but I am concerned that the blotting and vitrification process may have altered the protein's conformation. How can I validate that my structure represents the solution state? A1: You can validate your cryo-EM map using solution-based Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS). This method compares the cryo-EM map directly to SAXS data collected from proteins in a near-physiological solution. A novel, automated software package called AUSAXS is designed for this purpose. It generates a series of dummy-atom models from your EM map and calculates the expected SAXS curve for each, identifying the model that best fits the experimental SAXS data. This provides an independent check for potential conformational changes induced during cryo-EM sample preparation [32].

Q2: I am studying a flexible multi-specific antibody, and its flexibility is preventing high-resolution structure determination by cryo-EM. What strategies can I use to overcome this? A2: Intrinsic flexibility is a common challenge. A successful strategy is to use a partner protein or antibody fragment that binds to a different epitope on your target antigen. This binding can stabilize the flexible complex, reduce conformational heterogeneity, and facilitate particle alignment during image processing. This approach was used to determine the structure of a flexible CODV antibody in complex with IL13 by binding a second, reference antibody (RefAbFab) to a distinct IL13 epitope, which provided the necessary rigidity for a 4.2 Å resolution reconstruction [33].

Q3: My protein is relatively small (<100 kDa) and exhibits preferred orientation on cryo-EM grids. What are my options for achieving a high-resolution structure? A3: For small proteins or those with preferred orientation, consider these approaches:

- Increase Alignable Mass: Fuse your target protein to a stable, larger scaffold protein like aldolase, or bind fiducial markers such as Fabs (antibody fragments). This increases the particle's molecular weight and provides a more distinct shape for alignment [34].

- Optimize Ice Thickness: Very thin ice is required to visualize small particles with sufficient contrast. Extensive optimization of freezing conditions is often necessary [34].

- Use a Fiducial Marker: Technologies like Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) can be used to analyze binding kinetics and confirm interactions, which is helpful for validating constructs before moving to cryo-EM [26].

Q4: My protein contains large, intrinsically disordered regions that are missing from my high-resolution models. How can I obtain structural information about these flexible regions? A4: SAXS is exceptionally well-suited for studying flexible systems. It can provide low-resolution information about the overall shape and dimensions of the entire particle, including disordered regions. The data can be used to model the protein as an ensemble of multiple conformations in solution, providing insights into the dynamic behavior of the flexible domains that are often inaccessible to high-resolution methods like cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography [35] [36].

Q5: How can SAXS data complement and improve modern protein structure predictions from tools like AlphaFold? A5: SAXS data is a powerful tool for validating and refining computational protein structure predictions. You can:

- Validate Predictions: Calculate the theoretical SAXS curve from an AlphaFold2 or AlphaFold3 predicted model and compare it to your experimental SAXS data. A good match supports the model's accuracy [36] [37].

- Identify Discrepancies: Differences between the predicted and experimental curves can indicate that the solution structure differs from the prediction, potentially due to oligomerization, conformational flexibility, or the influence of the crystalline environment on training data [36].

- Guide Model Improvement: Computational servers can alter the predicted model (e.g., by changing the oligomerization state or sampling flexible regions) to generate an ensemble of models that collectively provide a better fit to the SAXS data, yielding a more biologically relevant solution structure [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Cryo-EM Sample Preparation and Grid Screening

Table 1: Common Cryo-EM Sample Preparation Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Empty grids or uneven ice | Inconsistent blotting; inappropriate sample concentration | Optimize blotting time and force; screen a range of sample concentrations (e.g., 0.5-3 mg/mL) [34]. |

| Preferred orientation | Strong interaction between particles and air-water interface | Alter grid surface chemistry (e.g., use graphene oxide or functionalized grids); add detergents or use detergents below CMC [34]. |

| Sample aggregation or denaturation | Buffer incompatibility; purification impurities | Use SEC-MALS to ensure monodispersity; optimize buffer conditions (pH, salt); include stabilizing additives [34] [36]. |

| Particle heterogeneity | Conformational flexibility; complex dissociation | Employ classification strategies; use a binding partner to stabilize a specific conformation [34] [33]. |

Troubleshooting SAXS Data Collection and Analysis

Table 2: Common SAXS Experimental Challenges and Remedies

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation at high concentration | Sample instability; non-physiological conditions | Use SEC-SAXS to separate aggregates and analyze only the monodisperse peak [36] [33]. |

| Concentration dependence in scattering data | Interparticle interactions or oligomerization | Collect data at multiple concentrations and extrapolate to infinite dilution [36]. |

| Poor fit between atomic model and SAXS data | Incorrect oligomeric state; solution flexibility | Test different oligomerization states in fitting algorithms; use ensemble methods to model flexibility [36]. |

| Radiation damage | High X-ray flux on sensitive samples | Use a flow-cell or capillary setup; reduce exposure time [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Integrated SEC-MALS-SAXS Data Collection

Purpose: To obtain high-quality SAXS data from a monodisperse protein sample while simultaneously determining its absolute molecular weight and oligomeric state.

- Sample Preparation: Purify the protein to >90% homogeneity using standard biochemical methods, with a final polishing step of size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) [34] [36].

- Sample Concentration: Concentrate the protein to 5-20 mg/mL [36].

- Equipment Setup: Connect an HPLC system to a size-exclusion column, which is connected in-line to a multi-angle light scattering (MALS) detector, a differential refractometer, and finally a SAXS flow cell [36].

- Data Collection:

- Inject 50-100 µL of the concentrated protein sample onto the SEC column.

- As the protein elutes from the column, the MALS detector measures the absolute molecular weight, the refractometer measures concentration, and the SAXS instrument continuously collects scattering data.

- The scattering from the buffer (before the protein peak) is used for background subtraction [36].

- Data Analysis:

Protocol: Using SAXS to Validate a Cryo-EM Map with AUSAXS

Purpose: To ensure that a cryo-EM map represents the native solution conformation of the biomolecule.

- Prerequisites: Obtain a cryo-EM map (in .mrc or similar format) and a corresponding experimental SAXS profile from the same protein in solution [32].

- Software Input: Provide the EM map and SAXS data to the AUSAXS software package [32].

- Model Generation: The software automatically generates a series of dummy-atom models from the EM map by scanning through different density threshold cutoff values. A hydration shell is simulated around each model [32].

- Scattering Calculation: The theoretical SAXS curve is calculated for each dummy-atom model using the Debye equation [32].

- Model Selection: The software compares each theoretical curve to the experimental SAXS data using the χ² statistic. The model with the best fit (lowest χ²) is selected as the one that best represents the solution structure [32].

- Interpretation: A good fit validates the cryo-EM map. A poor fit suggests that the vitrification process may have induced conformational changes in the protein [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for SAXS and Cryo-EM Studies

| Item | Function/Benefit | Application Context |

|---|---|---|