Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Inhibitors: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of orthosteric and allosteric inhibitor mechanisms for researchers and drug development professionals.

Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Inhibitors: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Applications, and Future Directions in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of orthosteric and allosteric inhibitor mechanisms for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both inhibition strategies, detailing how orthosteric drugs compete with endogenous ligands at the active site, while allosteric modulators bind at distal sites to induce conformational changes. The content covers advanced computational and experimental methodologies for inhibitor discovery, addresses key challenges including drug resistance and selectivity, and presents validation strategies through case studies across target classes like GPCRs and kinases. By synthesizing recent advances and comparative analyses, this review aims to guide the rational selection and design of next-generation therapeutic inhibitors.

Fundamental Principles: How Orthosteric and Allosteric Inhibitors Mechanistically Differ

In the realm of biochemistry and pharmacology, controlling protein function is a fundamental goal for both basic research and therapeutic intervention. Two primary strategies have emerged for modulating the activity of enzymes and receptors: orthosteric inhibition, which involves direct competition with the native substrate at the active site, and allosteric modulation, which entails binding at a topographically distinct site to remotely control protein function [1]. The choice between these strategies profoundly influences the selectivity, efficacy, and safety profile of potential therapeutics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these distinct mechanisms, underpinned by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their experimental design and therapeutic targeting.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Key Differences

Orthosteric inhibitors operate on a straightforward principle of spatial competition. They bind directly to the enzyme's active site or receptor's endogenous ligand-binding site, physically blocking substrate access [1] [2]. This mechanism is typically competitive, meaning its effectiveness can be overcome by sufficiently high substrate concentrations.

Allosteric inhibitors, in contrast, bind to a separate, regulatory site on the protein—the allosteric site. This binding induces a conformational change or alters protein dynamics that is transmitted through the protein structure to the active site, thereby modulating its activity [3] [1]. This mechanism is often non-competitive or uncompetitive, meaning the inhibitor's effect is not solely dependent on substrate concentration [2].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each mechanism.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Orthosteric and Allosteric Inhibitors

| Feature | Orthosteric Inhibitors | Allosteric Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | Active site (orthosteric site) [1] | Distinct, regulatory (allosteric) site [1] |

| Mechanism of Action | Direct steric blockade of substrate binding [1] | Indirect induction of conformational change [3] [1] |

| Relationship to Substrate | Typically competitive [1] | Typically non-competitive or uncompetitive [2] |

| Effect on Substrate Affinity | Reduces apparent affinity by competition | Can decrease or increase affinity of the active site for its substrate [1] |

| Saturability of Effect | Effect is not saturable; depends on [substrate]/[inhibitor] | Effect has a "ceiling"; saturable once allosteric sites are occupied [2] [4] |

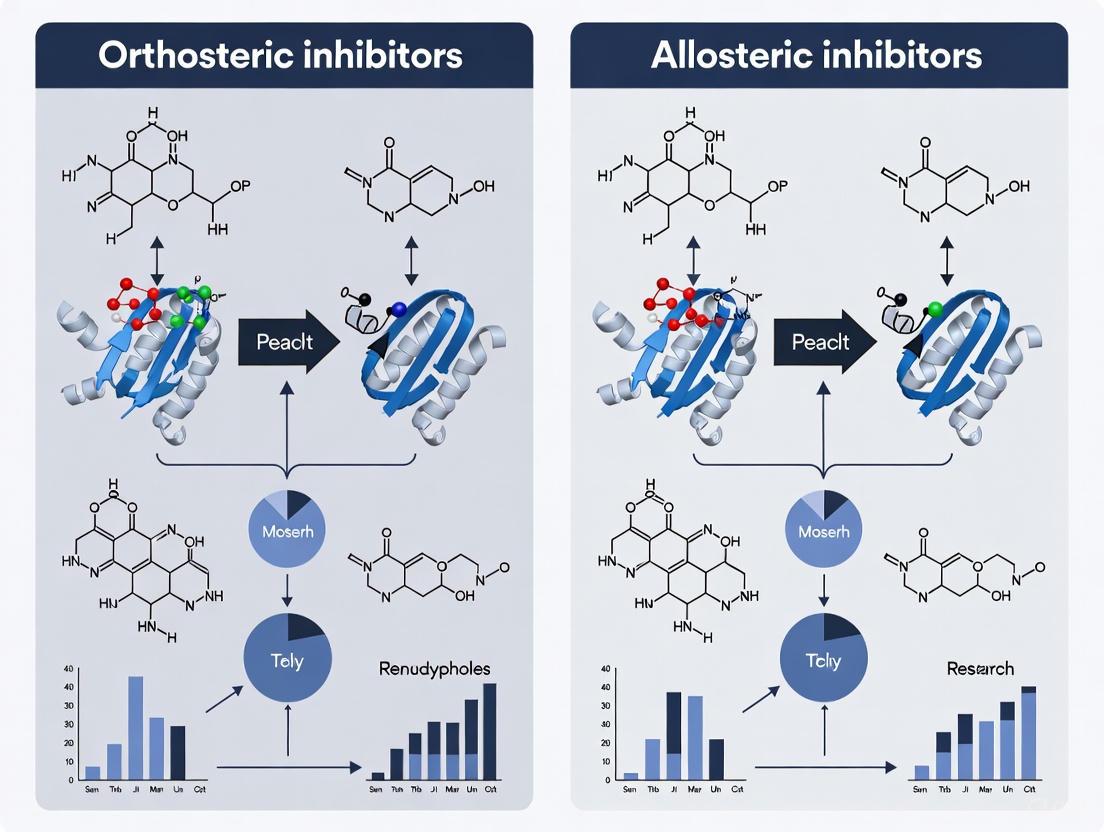

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences between orthosteric and allosteric inhibition.

Comparative Analysis: Therapeutic and Experimental Implications

The mechanistic differences between orthosteric and allosteric modulators translate into distinct advantages and challenges in a therapeutic context.

Table 2: Therapeutic and Experimental Implications of Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Modulation

| Aspect | Orthosteric Modulators | Allosteric Modulators |

|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Challenging due to high conservation of active sites across protein families [2] | Higher potential; allosteric sites are less evolutionarily conserved [5] [2] [4] |

| Safety & Toxicity | Higher risk of off-target effects due to conserved sites; can completely shut down protein function [6] [4] | Lower risk; ceiling effect prevents total inhibition; preserves temporal/spatial signaling of endogenous ligand [2] [6] |

| Physiological Effect | "Blunt" intervention; overrides natural rhythm of endogenous signaling [6] | "Tuning knob"; fine-tunes tissue response to the endogenous agonist [5] [6] |

| Resistance | More prone to resistance (e.g., via elevated substrate/substrate mutations) [4] | Less prone; can be used in combination with orthosterics to minimize resistance [4] |

| Chemical Tractability | Can be limited by highly polar/charged active sites [2] | Often improved physicochemical properties [2] |

A key advantage of allosteric modulators is their ability to achieve unprecedented selectivity. For example, in kinase targeting, orthosteric inhibitors often target the highly conserved ATP-binding site, leading to off-target effects and toxicity. In contrast, allosteric kinase inhibitors bind to less conserved sites, affording greater kinome selectivity and improved safety [3] [2]. Furthermore, allosteric modulators can impart functional selectivity or biased signaling, whereby they stabilize receptor conformations that preferentially activate a subset of downstream signaling pathways [2] [7]. This allows for more precise pharmacological control.

Experimental Approaches and Data Interpretation

Distinguishing between orthosteric and allosteric mechanisms requires specific experimental designs and careful interpretation of the resulting data.

Key Methodologies and Protocols

- Radioligand Binding Assays: Used to identify ligand-receptor interactions.

- Protocol for Competition Binding: Incubate the receptor with a fixed concentration of a radiolabeled orthosteric ligand and varying concentrations of the unlabeled test compound. A competitive (orthosteric) inhibitor will produce a concentration-response curve where the radioligand binding is fully inhibited. A compound that fails to fully displace the radioligand may be binding to an allosteric site [2].

- Functional Assays (e.g., TRUPATH BRET, TGFα Shedding): Measure downstream signaling outputs (e.g., cAMP, calcium mobilization, β-arrestin recruitment) [7].

- Protocol for Schild Regression Analysis: Perform concentration-response curves for the endogenous agonist in the absence and presence of increasing concentrations of the test inhibitor. A parallel rightward shift of the curve with no suppression of the maximal response is characteristic of competitive (orthosteric) antagonism. A depression of the maximal response is indicative of a non-competitive (often allosteric) mechanism [6].

- Kinetic and Saturation Binding Studies:

- Protocol: Assess the association and dissociation rates of a radiolabeled orthosteric ligand in the presence of the test compound. An allosteric modulator will typically alter the dissociation rate of the orthosteric ligand, a phenomenon known as a "probe-dependence" effect, whereas an orthosteric competitor will not [2].

Interpretation of Functional Data

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for interpreting functional assay data to characterize an inhibitor's mechanism of action, based on the modulation of an agonist's concentration-response curve (CRC).

Case Studies and Supporting Experimental Data

Case Study 1: Targeting the A2B Adenosine Receptor (GPCR)

Research on the A2B adenosine receptor (A2B AR) highlights the therapeutic rationale for pursuing allosteric modulators. The orthosteric site of ARs is highly conserved across its four subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, A3), making the development of selective orthosteric agonists challenging [5]. Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs) of the A2B AR have been developed to fine-tune the receptor's response to endogenous adenosine, offering potential for treating conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic injury, and osteoporosis with greater spatial and temporal selectivity than orthosteric ligands [5].

Table 3: Experimental Data on A2B AR Ligands in Pre-Clinical Models

| Ligand Name | Type | Key Experimental Findings | In Vivo Model / Assay |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAY-60-6583 | Orthosteric Agonist | Attenuates pulmonary edema, diminishes lung inflammation [5]. | Murine model of acute lung injury [5] |

| Unnamed PAMs/NAMs | Allosteric Modulators (PAMs & NAMs) | Proposed to fine-tune tissue responses to endogenous adenosine, potentially offering superior management of pathological conditions [5]. | In vitro signaling studies; pre-clinical models of COPD, fibrosis [5] |

Case Study 2: Targeting CCR2 for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF)

A 2025 study employed structure-based design to develop both orthosteric and allosteric inhibitors for the CCR2 receptor as a potential IPF therapy [8]. Using integrated computational and experimental approaches, researchers identified:

- Compound 17: An orthosteric inhibitor with a binding free energy of -30.91 kcal/mol.

- Compound 67: An allosteric inhibitor with a binding free energy of -26.11 kcal/mol.

Experimental Validation: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) confirmed compound 17's direct binding to murine CCR2 (KD = 3.46 μM). Crucially, co-administration of the allosteric compound 67 synergistically enhanced the binding affinity of the orthosteric compound, demonstrating the potential of dual-pocket targeting strategies [8]. In a TGF-β-induced pulmonary fibrosis cell model, both compounds significantly reduced hydroxyproline and COL1A1 levels (fibrosis markers), with the orthosteric compound 17 showing comparable efficacy to the positive control nintedanib [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Investigating Orthosteric and Allosteric Mechanisms

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| TRUPATH BRET Sensors | Measures ligand-induced activation of specific Gα protein subtypes in live cells [7]. | GPCR signaling bias and selectivity profiling. |

| Recombinant Proteins (e.g., ACE, α-glucosidase) | Purified enzyme targets for in vitro inhibition assays and binding studies [9] [10]. | Enzyme inhibition kinetics and mechanism studies. |

| SBI-553 | Intracellularly-binding allosteric modulator of Neurotensin Receptor 1 (NTSR1) [7]. | Prototypical compound for studying allosteric switching of G protein selectivity. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free technique for real-time analysis of binding kinetics (KD, kon, koff) [8]. | Direct measurement of ligand-target binding and cooperative effects. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computational method to simulate and analyze protein-ligand interactions and conformational changes over time [8] [4]. | Predicting binding stability and elucidating allosteric communication pathways. |

The choice between orthosteric and allosteric strategies defines a critical battlefield in modern drug discovery. Orthosteric inhibitors, with their direct mechanism, remain a powerful tool but often lack selectivity. Allosteric modulators offer a sophisticated means of "remote control" with inherent advantages in selectivity, safety, and the ability to fine-tune physiological responses. The future of the field lies in leveraging advanced experimental and computational tools to identify and characterize allosteric sites, and in developing intelligent combination therapies that exploit the synergistic potential of both mechanisms, as demonstrated in the CCR2 case study. This comparative guide provides a framework for researchers to navigate this complex landscape and design more effective and targeted therapeutic interventions.

In the realm of molecular pharmacology and drug discovery, two distinct mechanisms dominate the strategic inhibition of protein function: orthosteric inhibition, which involves direct physical blockade of the active site, and allosteric inhibition, which modulates function through conformational changes induced at sites distant from the active region [11] [1]. This distinction represents more than merely different binding locations; it encompasses fundamentally divergent approaches to controlling biological activity with profound implications for drug specificity, efficacy, and therapeutic application.

The evolutionary conservation of active sites across protein families presents significant challenges for orthosteric drug development, whereas the typically lower evolutionary pressure on allosteric sites offers enhanced opportunities for selective targeting [12] [11]. This comparative analysis examines the molecular mechanisms, experimental characterization, and therapeutic applications of these two inhibitory strategies, providing researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate intervention strategies in drug development campaigns.

Orthosteric Inhibition: Direct Active Site Competition

Fundamental Mechanism

Orthosteric inhibitors function through a direct competitive mechanism by binding reversibly or irreversibly to the enzyme's active site, physically preventing substrate access and thereby blocking catalytic activity [11] [1]. This approach represents the most straightforward inhibitory strategy, characterized by its occupancy-driven mechanism where inhibition efficacy primarily depends on the inhibitor's concentration and binding affinity relative to the natural substrate.

The binding site for orthosteric inhibitors is identical to the substrate binding site, typically characterized by deep, well-defined pockets with conserved structural features across protein families [11]. This evolutionary conservation, while functionally necessary, presents the primary challenge for orthosteric drug development: achieving selectivity among related proteins with similar active site architectures.

Experimental Characterization and Validation

Table 1: Key Experimental Approaches for Characterizing Orthosteric Inhibition

| Method | Experimental Readout | Information Obtained | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Binding Assays | IC50 shift with increasing substrate concentration | Binding competition with native ligand | Classic diagnostic for orthosteric mechanism |

| X-ray Crystallography | Electron density at active site | Atomic-level binding mode confirmation | Requires high-resolution crystals |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Direct binding affinity (KD) | Binding kinetics without competition | Measures binding independent of function |

| Enzyme Activity Assays | Dose-response curves (IC50) | Functional inhibition potency | Does not directly prove binding site |

Case Study: CCR2 Orthosteric Inhibition - In recent work on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, researchers identified compound 17 as a potent orthosteric inhibitor of CCR2. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable binding at the orthosteric site with a free energy of -30.91 kcal/mol, while surface plasmon resonance directly demonstrated binding to murine CCR2 with KD = 3.46 μM [13]. This comprehensive approach exemplifies the multi-faceted methodology required to unequivocally establish orthosteric inhibition.

Allosteric Inhibition: Indirect Modulation Through Conformational Control

Fundamental Mechanism

Allosteric inhibitors operate through a more sophisticated mechanism, binding to regulatory sites distinct from the active site and inducing conformational or dynamic changes that propagate through the protein structure to alter active site functionality [1] [4]. This paradigm represents a fundamental shift from occupancy-driven to ensemble-based pharmacology, where the inhibitor's effect emerges from its ability to perturb the protein's conformational landscape and shift the equilibrium toward inactive states [12] [11].

The theoretical framework for understanding allosteric regulation has evolved significantly beyond early models like Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) and Koshland-Nemethy-Filmer (KNF) [12] [1]. The contemporary Ensemble Allosteric Model (EAM) interprets allostery through the lens of thermodynamic ensembles of microstates, where populations of each microstate are governed by Boltzmann distributions dictated by free energies of conformational change and inter-domain interactions [12]. This framework successfully explains phenomena such as allosteric partial agonism and pluripotency, which challenge classical models.

Emerging Mechanistic Insights

Recent studies on signaling enzymes including PKA, PKG, and EPAC reveal a common theme in allosteric inhibition: the stabilization of distinct "mixed" conformational states that exhibit characteristics of both active and inactive states in different protein regions [12] [14]. For example, in human cGMP-dependent protein kinase (hPKG), cAMP acts as a partial agonist by sampling a three-state equilibrium where the orientation of N-terminal helices and phosphate-binding cassette resembles the active state, while C-terminal helices remain disengaged and dynamic similar to the inactive state [12].

Case Study: USP7 Allosteric Inhibition - Research on ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) demonstrates how allosteric inhibitor binding increases flexibility in the fingers and palm domains, simultaneously restraining dynamics at the C-terminal ubiquitin binding site and disrupting proper alignment of the catalytic triad (Cys223-His464-Asp481) [15]. This dynamic perturbation effectively disrupts catalytic activity without direct competition with ubiquitin binding.

Comparative Analysis: Orthosteric versus Allosteric Mechanisms

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of Orthosteric and Allosteric Inhibition Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Orthosteric Inhibition | Allosteric Inhibition |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | Active site (highly conserved) | Allosteric site (less conserved) |

| Mechanism | Direct physical blockade | Conformational/dynamic change |

| Specificity Challenges | High (due to active site conservation) | Lower (targets less conserved regions) |

| Theoretical Model | Occupancy-driven | Ensemble-based (EAM) |

| Pharmacological Effect | Complete activity blockade | Tunable modulation (partial to complete) |

| Native Ligand Interference | Competitive | Non-competitive or uncompetitive |

| Resistance Development | Higher susceptibility | Lower susceptibility |

| Therapeutic Finesse | Binary on/off effect | Fine-tuned modulation |

Selectivity and Specificity Considerations

The specificity mechanisms differ fundamentally between these approaches. For orthosteric drugs, specificity depends critically on achieving high binding affinity to allow low dosage administration that selectively targets only proteins with the highest complementary binding sites [11]. In contrast, allosteric drug specificity derives from targeting less-conserved surface regions and optimizing interaction networks that propagate effects specifically to the intended active site [11] [4].

This distinction has profound implications for drug discovery. Orthosteric inhibitors require exquisite optimization for selective affinity, while allosteric inhibitors demand consideration of the protein conformational ensemble and preferred propagation states to elicit specific functional outcomes [11].

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Validation

The clinical success of allosteric inhibitors is particularly evident in targeting previously "undruggable" proteins. KRAS G12C inhibitors represent a landmark achievement, where compounds like sotorasib and adagrasib target a specific allosteric pocket near the mutant cysteine residue, covalently trapping KRAS in its inactive GDP-bound conformation [16] [4]. These inhibitors demonstrate remarkable selectivity, exhibiting 215-fold greater potency against mutant KRAS compared to the wild-type protein [4].

In direct comparative clinical studies, allosteric modulators have demonstrated significant efficacy advantages. In chronic myeloid leukemia treatment, the allosteric modulator asciminib achieved a 25.5% major molecular response rate compared to 13.2% for the orthosteric inhibitor bosutinib [4]. Similarly, the allosteric MEK inhibitor trametinib achieved superior target inhibition with substantially lower concentration requirements compared to orthosteric alternatives [4].

Experimental Methodologies for Mechanism Elucidation

Core Technical Approaches

Table 3: Essential Methodologies for Inhibitor Mechanism Characterization

| Technique | Orthosteric Application | Allosteric Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | Limited | Mapping free energy landscapes and dynamics | Sensitivity and protein size constraints |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Binding pose validation | Capturing allosteric propagation and ensemble shifts | Computational cost and timescale limitations |

| X-ray Crystallography | Atomic-resolution active site binding | Identification of cryptic allosteric pockets | Static picture of dynamic processes |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy | Limited for small molecules | Visualizing large-scale conformational changes | Resolution limitations for small ligands |

| Mutational Analysis | Active site residue mapping | Pathway residue identification | May disrupt overall folding |

Integrated Workflow for Allosteric Inhibitor Characterization

A comprehensive approach to allosteric mechanism elucidation combines NMR, MD simulations, and Ensemble Allosteric Modeling (EAM) [12] [14]. NMR provides experimental observation of conformational equilibria and dynamics, MD simulations offer atomic-level details of allosteric propagation and ensemble sampling, while EAM integrates these data into a quantitative thermodynamic framework that predicts functional response [12].

For example, in studying USP7 allosteric inhibition, researchers employed multi-replica MD simulations of apo, ubiquitin-bound, and inhibitor-bound states, followed by dynamic cross-correlation matrix analysis and community network analysis to reveal state-specific dynamic signatures and communication pathways [15].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Inhibitor Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15N-labeled Proteins | NMR spectroscopy dynamics studies | Mapping allosteric conformational changes | Requires specialized expression systems |

| Covalent Fragment Libraries | Tethering to identify allosteric sites | KRAS G12C inhibitor discovery | Requires cysteine-tethering compatible libraries |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Models | Virtual screening for site-selective inhibitors | CCR2 orthosteric/allosteric inhibitor identification | Dependent on quality of structural data |

| Engineered Cell Lines | Pathway-specific reporter assays | Monitoring intracellular signaling modulation | Requires careful validation of specificity |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance Chips | Direct binding kinetics measurement | Orthosteric vs allosteric binding characterization | Immobilization must not affect binding sites |

Visualizing Mechanistic Pathways

Orthosteric Competitive Inhibition

Allosteric Conformational Modulation

The comparative analysis of orthosteric and allosteric inhibition mechanisms reveals complementary strengths that can be strategically leveraged in drug development. Orthosteric inhibitors provide potent, complete blockade ideal for scenarios requiring absolute pathway interruption, while allosteric modulators offer finer pharmacological control with enhanced selectivity, particularly valuable for previously intractable targets.

The emerging paradigm emphasizes not exclusive selection of one approach over the other, but rather strategic integration. This is exemplified by the development of dual-pocket targeting strategies as demonstrated in CCR2 inhibition, where orthosteric and allosteric compounds can be co-administered for synergistic effects [13]. Furthermore, combination therapies pairing allosteric modulators with orthosteric drugs present promising avenues to overcome drug resistance—a significant limitation of single-mechanism approaches [4].

As structural biology and computational methodologies continue to advance, enabling more precise mapping of allosteric landscapes and communication networks, the rational design of both orthosteric and allosteric inhibitors will become increasingly sophisticated. The future of therapeutic inhibition lies in harnessing the unique advantages of both mechanisms, often in combination, to achieve unprecedented specificity and efficacy in targeting challenging disease mechanisms.

In the landscape of modern drug discovery, the strategic inhibition of pathological proteins is paramount. Two fundamental mechanisms—orthosteric and allosteric inhibition—offer distinct approaches with complementary advantages and limitations. Orthosteric inhibitors bind directly to a protein's active site, competing with and typically blocking the natural substrate. In contrast, allosteric inhibitors bind to a topographically distinct site, inducing conformational or dynamic changes that indirectly modulate activity at the active site [4] [11]. This review provides a comparative analysis of these mechanisms, focusing on their specificity, tunability, and therapeutic applications, to inform strategic decisions in preclinical research and development.

Mechanistic and Pharmacological Comparison

The fundamental difference in binding location between orthosteric and allosteric inhibitors leads to divergent pharmacological profiles. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Inhibitors

| Feature | Orthosteric Inhibitors | Allosteric Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | Active site (orthosteric site) [11] | Distal, regulatory site [4] [17] |

| Mechanism of Action | Direct competition with endogenous substrate [11] | Indirect modulation via conformational/dynamic change [4] [17] |

| Effect on Activity | Typically complete blockade | Fine-tuning; can be inhibitory or enhancing [18] |

| Evolutionary Conservation | High (across protein families) [11] | Low (more unique to specific proteins) [17] [11] |

| Saturation Effect | Not applicable | "Ceiling effect" common [4] |

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual mechanistic differences and the experimental workflow for evaluating these inhibitors.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Pharmacological Parameters

The theoretical advantages of allosteric modulators are borne out in experimental data. The following table compiles key quantitative findings from recent studies, demonstrating differences in affinity, selectivity, and efficacy.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Preclinical and Clinical Studies

| Inhibitor Type / Example | Key Quantitative Finding | Experimental Model | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allosteric: Trametinib (MEK inhibitor) | >14x more potent (lower nM concentration) and 7.2x higher pMEK/uMEK ratio vs. orthosteric selumetinib [4] | Targeted cancer therapy | [4] |

| Allosteric: Asciminib (CML treatment) | Higher major molecular response rate (25.5% vs. 13.2%) vs. orthosteric bosutunib [4] | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) clinical trial | [4] |

| Allosteric: KRAS G12C inhibitors | 215-fold more potent against mutant KRAS than wild-type [4] | Cancer model | [4] |

| Orthosteric: Compound 17 (CCR2) | Binding free energy: -30.91 kcal mol⁻¹; KD (SPR): 3.46 μM [8] | Murine CCR2, pulmonary fibrosis model | [8] |

| Allosteric: Compound 67 (CCR2) | Binding free energy: -26.11 kcal mol⁻¹; synergistically enhanced orthosteric binding [8] | Murine CCR2, pulmonary fibrosis model | [8] |

| Dual Therapy (Ortho + Allo) | Synergistic reduction of hydroxyproline & COL1A1; upregulation of ELN [8] | TGF-β-induced pulmonary fibrosis cell model | [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

To facilitate replication and further research, this section outlines core methodologies used to generate the comparative data.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations and Free Energy Calculations

Purpose: To characterize the stability of inhibitor binding and calculate binding free energies, which are critical for understanding allosteric mechanisms [8] [17].

- Procedure:

- System Preparation: Obtain a 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., CCR2). Dock the candidate inhibitor into the putative orthosteric or allosteric site. Embed the protein-ligand complex in a solvated lipid bilayer for membrane proteins or in a water box for soluble proteins. Add ions to neutralize the system.

- Energy Minimization: Use steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to relieve steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Run short simulations with positional restraints on the protein and ligand, gradually releasing the restraints to allow the system to relax.

- Production MD Simulation: Run an unrestrained simulation for hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds, integrating Newton's equations of motion to track atomic movements [17].

- Free Energy Calculation: Apply the Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) method to snapshots from the MD trajectory to compute binding free energy (ΔG_bind) [8].

- Enhanced Sampling (Optional): For probing rare events, use techniques like umbrella sampling to compute the potential of mean force along a defined reaction coordinate, or metadynamics to explore conformational space and identify cryptic allosteric sites [17].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Binding Kinetics

Purpose: To experimentally measure the binding affinity (KD) and kinetic parameters (kon, koff) of an inhibitor for its target protein in real-time, without labels [8].

- Procedure:

- Immobilization: Covalently immobilize the purified target protein on a dextran-coated gold sensor chip.

- Ligand Injection: Inject a series of concentrations of the inhibitor analyte over the chip surface in a continuous flow of buffer.

- Data Collection: Monitor the change in the SPR signal (Response Units, RU) as a function of time during the association (injection) and dissociation (buffer flow) phases.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting sensorgrams to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to determine the association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), and calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD = koff/kon) [8].

Functional Cell-Based Assay (CCK-8 for Fibrosis)

Purpose: To evaluate the functional, phenotypic efficacy of inhibitors in a disease-relevant cellular model.

- Procedure:

- Cell Culture and Model Induction: Culture relevant cells (e.g., pulmonary fibroblasts). Induce a fibrotic phenotype by treatment with TGF-β [8].

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with a concentration gradient of the test inhibitor (e.g., orthosteric Compound 17, allosteric Compound 67) and a positive control (e.g., nintedanib).

- Viability/Inhibition Assessment: Add CCK-8 reagent. Metabolically active cells reduce WST-8 in CCK-8 to an orange-colored formazan product. Measure the absorbance at 450 nm to quantify cell viability and the inhibitory effect of the compounds [8].

- Biomarker Analysis: Quantify fibrosis biomarkers like hydroxyproline content (colorimetric assay) and COL1A1/ELN expression levels (e.g., by RT-qPCR or Western Blot) to confirm anti-fibrotic activity [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Orthosteric and Allosteric Inhibitor Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Protein | Essential for structural studies, in vitro binding assays (SPR), and biochemical activity assays. | Immobilizing CCR2 for SPR kinetics [8]. |

| Crystallography or Cryo-EM Kits | To determine high-resolution 3D structures of protein-inhibitor complexes, revealing binding modes. | Identifying novel allosteric pockets and confirming ligand placement [4] [17]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates dynamic behavior of proteins, identifies transient pockets, and calculates binding energies. | Characterizing allosteric communication pathways and cryptic sites [17] [19]. |

| Cell-Based Disease Models | Provides a physiologically relevant context for testing inhibitor efficacy and toxicity. | TGF-β-induced pulmonary fibrosis model for anti-fibrotic drug screening [8]. |

| Allosteric Site Prediction Tools | Computational identification of potential allosteric sites from protein sequence/structure. | Tools like PASSer and AlloReverse for rational drug design [17] [20]. |

The choice between orthosteric and allosteric strategies is not a simple binary but a strategic decision based on therapeutic goals. Orthosteric inhibitors remain a powerful tool when complete, potent inhibition of a target is required. However, their application can be limited by toxicity from off-target effects due to conserved active sites. Allosteric inhibitors offer a sophisticated means to achieve fine-tuning, high selectivity, and the targeting of previously "undruggable" proteins like mutant KRAS [4] [18].

The future lies in leveraging the strengths of both modalities. As demonstrated with CCR2, combination therapy or the development of bitopic inhibitors (single molecules engaging both orthosteric and allosteric sites) presents a promising path to enhance efficacy, overcome resistance, and deliver more precise and durable therapeutics [8] [21]. The continued advancement of computational methods, particularly MD simulations and machine learning for allosteric site prediction, will be the engine for the next generation of allosteric drug discovery [17] [19] [22].

In the realm of drug discovery and therapeutic intervention, two fundamental mechanisms—orthosteric inhibition and allosteric modulation—dictate cellular outcomes with profound implications for efficacy and safety. Orthosteric drugs bind directly to the active site of a protein, competing with the native substrate to completely halt protein activity [11]. In contrast, allosteric drugs bind at topographically distinct sites, inducing conformational changes that fine-tune protein function rather than abolishing it entirely [11] [23]. This distinction represents more than just binding location; it fundamentally alters the cellular consequences, selectivity profiles, and therapeutic potential of pharmacological interventions. Understanding these differential outcomes is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to design targeted therapies with optimal benefit-risk profiles.

Mechanistic Foundations and Key Concepts

Orthosteric Inhibition: Complete Functional Blockade

Orthosteric inhibitors operate through direct competition with endogenous ligands or substrates for the evolutionarily conserved active site of target proteins [11]. This mechanism results in complete inhibition of protein function when sufficient drug concentration is achieved. The active sites of proteins within the same family are often highly conserved, creating significant challenges for achieving selectivity and increasing the potential for off-target effects [11]. As one research group noted, "If the concentration of the drug is high, it will bind to the target protein as well as to other similar binding sites in homologous members of the protein family" [11]. This fundamental limitation underscores the importance of achieving high affinity in orthosteric drug design to enable target-selective binding at low dosages.

Allosteric Modulation: Fine-Tuned Functional Adjustment

Allosteric modulators bind to regions distinct from the orthosteric site, inducing conformational changes that propagate through the protein structure to indirectly influence activity at the active site [11] [23]. This mechanism enables fine-tuned modulation of protein function, allowing for either enhancement (positive allosteric modulation) or reduction (negative allosteric modulation) of activity without completely abolishing it [23]. Allosteric sites are typically less conserved than orthosteric sites across protein families, offering inherent advantages for achieving selectivity [11] [5]. The binding of allosteric modulators "perturbs the protein surface atoms, and the perturbation propagates like waves, finally reaching the binding site" [11], shifting the free energy landscape of the protein and altering the population distribution of its conformational states.

Allosteric Modulator Classification

- Positive Allosteric Modulators (PAMs): Enhance protein activity; include full agonists and partial agonists [23]

- Negative Allosteric Modulators (NAMs): Reduce protein activity; include inverse agonists, neutral antagonists, and partial antagonists [23]

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Orthosteric versus Allosteric Targeting

| Characteristic | Orthosteric Inhibitors | Allosteric Modulators |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | Active/catalytic site | Topographically distinct site |

| Mechanism | Direct competition with native ligand | Conformational change propagation |

| Effect on Activity | Complete inhibition | Fine-tuned modulation (up or down) |

| Selectivity Potential | Lower (active sites conserved) | Higher (allosteric sites less conserved) |

| Functional Outcome | Binary (on/off) | Gradual (rheostatic) |

| Therapeutic Disruption | High | Context-dependent |

Comparative Experimental Data and Signaling Outcomes

Quantitative Binding and Functional Data

Recent research on C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) inhibitors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis provides direct comparative data between orthosteric and allosteric approaches [8]. Through integrated computational and experimental methods, researchers demonstrated that compound 17 (orthosteric) and compound 67 (allosteric) achieved high site selectivity with distinct binding characteristics and functional outcomes.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Orthosteric and Allosteric CCR2 Inhibitors

| Parameter | Orthosteric Inhibitor (Compound 17) | Allosteric Inhibitor (Compound 67) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site | CCR2 orthosteric site | CCR2 allosteric site |

| Binding Free Energy | -30.91 kcal/mol | -26.11 kcal/mol |

| Binding Affinity (K_D) | 3.46 μM | Not reported |

| Synergistic Effect | None observed | Enhanced orthosteric binding when co-administered |

| Antifibrotic Efficacy | Comparable to positive control nintedanib | Significant reduction in hydroxyproline and COL1A1 |

| Experimental Validation | Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) | Molecular dynamics simulations |

Cellular Signaling Consequences

The functional outcomes of orthosteric versus allosteric targeting extend to fundamental differences in cellular signaling pathways. Allosteric modulators can achieve unprecedented selectivity in G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling, as demonstrated by recent work with the neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1) [7]. The intracellular allosteric modulator SBI-553 was shown to "switch the G protein preference of NTSR1 through direct intermolecular interactions," effectively biasing signaling toward specific G protein subtypes while antagonizing others [7]. This biased signaling enables selective pathway modulation that is impossible to achieve with orthosteric inhibitors.

In contrast, orthosteric targeting typically affects all downstream signaling pathways equally. For example, the orthosteric antagonist SR142948A "produced a uniform, concentration-dependent blockade of NT-induced β-arrestin recruitment and G protein activation, regardless of the Gα subtype" [7]. This blanket inhibition can lead to both therapeutic effects and on-target side effects, as beneficial and deleterious signaling pathways are simultaneously disrupted.

Diagram 1: Signaling consequences of orthosteric versus allosteric targeting

Methodologies for Experimental Characterization

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow

The characterization of orthosteric and allosteric mechanisms requires sophisticated multidisciplinary approaches. A recent study on CCR2 inhibitors exemplifies this integrated methodology [8]:

- Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Identification of critical chemical features for target binding

- 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR): Correlation of molecular structure with biological activity

- Large-Scale Virtual Screening: Evaluation of 152,406 molecules for potential binding

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Assessment of binding stability and conformational changes

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Potential Energy Surface Analysis: Characterization of molecular motions and energy landscapes

- Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) Calculations: Quantification of binding free energies

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Experimental validation of binding affinity and kinetics

- Functional Cellular Assays: Assessment of antifibrotic effects in TGF-β-induced models

Specialized Techniques for Allosteric Mechanism Elucidation

Allosteric modulation requires additional specialized methodologies to characterize its distinct mechanisms:

- Free Energy Landscape Analysis: "Drug binding shifts the free energy landscape: conformations that were sparsely populated before can become more populated, and vice versa" [11]

- Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) Assays: Enable real-time monitoring of specific transducer activation pathways (e.g., TRUPATH BRET2 sensors for G protein subtype selectivity) [7]

- Transforming Growth Factor-α (TGFα) Shedding Assay: Assesses G protein activation through engineered sensors with swapped C-terminal amino acids to confer subtype specificity [7]

- Umbrella Sampling: Provides potential energy surface analysis for binding confirmation [8]

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for inhibitor characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Orthosteric and Allosteric Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| TRUPATH BRET2 Sensors | Profiling G protein subtype activation selectivity | Simultaneous assessment of 14 Gα proteins [7] |

| SPR Chips & Buffers | Label-free binding kinetics analysis | Direct binding affinity measurement (e.g., KD determination) [8] |

| TGFα Shedding Assay System | G protein activation profiling | Chimeric G proteins with swapped C-termini [7] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulating protein-ligand interactions & conformational changes | Binding stability assessment and energy calculations [8] |

| 3D-QSAR Modeling Tools | Structure-activity relationship analysis | Correlation of molecular features with biological activity [8] |

| Virtual Screening Libraries | High-throughput identification of candidate compounds | Screening of >150,000 molecules for hit identification [8] |

| MM/PBSA Computational Methods | Binding free energy calculations | Quantitative comparison of inhibitor affinities [8] |

Biological Implications and Therapeutic Applications

Functional Fine-Tuning in Physiological Systems

The cellular consequences of allosteric modulation extend to precise functional fine-tuning that maintains physiological homeostasis. This is particularly evident in modular proteins and signaling systems where "allosteric modulators can fine-tune the tissue responses to the endogenous agonist" [5]. For example, in G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), allosteric modulators "can exert their influence even if an endogenous ligand is bound to another site on the same target at the same time" [11], enabling context-dependent modulation rather than blanket inhibition.

The multi-lock autoinhibition mechanisms in HECT family E3 ubiquitin ligases exemplify how natural systems employ allosteric principles for functional fine-tuning [24]. WWP1 maintains autoinhibition through a "headset architecture" where "WW2 and WW4 domains act as the 'right ear' and 'left ear,' respectively, when binding to bilateral sites of the N-lobe, whereas L functions as the 'headband' of the headset" [24]. Cancer-associated mutations disrupting this allosteric regulation result in constitutive activation, demonstrating the pathological consequences of failed fine-tuning mechanisms.

Therapeutic Advantages and Clinical Translation

The cellular consequences of complete inhibition versus fine-tuned modulation directly impact therapeutic outcomes:

- Side Effect Profiles: Allosteric modulators generally demonstrate "fewer side effects" due to their saturable effect (ceiling effect) and greater selectivity [11]

- Physiological Compatibility: Allosteric modulators "can fine-tune the tissue responses to the endogenous agonist" [5], working with rather than against physiological systems

- Therapeutic Context: Orthosteric inhibitors may be preferable when complete pathway blockade is required, while allosteric modulators excel when "less disruptive" influence of pathway functioning is desired [11]

- Combination Potential: Allosteric and orthosteric approaches can be synergistic, as demonstrated by the finding that "co-administration with compound 67 synergistically enhanced binding affinity" of an orthosteric inhibitor [8]

The cellular consequences of complete inhibition through orthosteric targeting versus fine-tuned modulation via allosteric mechanisms represent a fundamental dichotomy in therapeutic intervention. Orthosteric inhibitors provide powerful tools for complete pathway blockade when necessary, but suffer from selectivity challenges and binary functional outcomes. Allosteric modulators offer sophisticated control over protein function, enabling pathway-selective effects and maintenance of physiological signaling context. The choice between these approaches must be guided by therapeutic goals, pathological context, and the desired balance between efficacy and selectivity. As drug discovery advances, the integration of both strategies, supported by the sophisticated methodological toolkit outlined here, promises more targeted and effective therapeutic interventions with optimized cellular outcomes.

In the field of drug discovery, understanding the fundamental distinctions between orthosteric and allosteric regulatory mechanisms is paramount. Orthosteric sites are the traditional binding pockets where endogenous substrates or competitive inhibitors bind, typically representing the active site in enzymes or the primary ligand-binding site in receptors. In contrast, allosteric sites are regulatory binding locations distinct from the orthosteric site, where effector molecules bind to modulate protein activity through induced conformational changes or dynamic adjustments [4] [6]. This comparison guide examines the evolutionary conservation patterns between these site types, providing researchers with objective data and methodological approaches to inform target selection and therapeutic design.

The distinction between these mechanisms carries profound implications for pharmacological intervention. Orthosteric drugs typically compete with natural ligands for binding, often requiring high affinity to achieve efficacy and potentially disrupting normal physiological signaling. Allosteric modulators, however, offer a more nuanced approach by fine-tuning protein activity without completely activating or inhibiting function, potentially preserving physiological rhythms and reducing side effects [6] [25]. This guide systematically compares the evolutionary conservation, experimental characterization, and therapeutic implications of these distinct binding regions to assist researchers in making evidence-based decisions for inhibitor development.

Comparative Analysis of Evolutionary Conservation Patterns

Quantitative Conservation Metrics

Table 1: Evolutionary Conservation Metrics for Protein Functional Sites

| Feature | Active/Orthosteric Sites | Allosteric Sites |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Conservation | Highly conserved across species [26] [27] | Poorly conserved; show evolutionary diversity [28] [25] |

| Structural Conservation | High structural conservation within protein families [29] | Moderate structural conservation despite sequence divergence [29] |

| Evolutionary Pressure | Strong purifying selection [26] | Relaxed constraints; more tolerant to variation [28] |

| Conservation Gradient | Steep conservation gradient with distance (up to 27.5Å) [26] | Weak or no consistent distance-based conservation pattern |

| Functional Role | Direct involvement in catalytic activity or primary function [30] [27] | Regulatory modulation of protein activity [30] [17] |

Structural and Functional Constraints

The differential evolutionary pressures on orthosteric versus allosteric sites reflect their distinct functional roles within protein architectures. Research demonstrates that catalytic residues induce long-range evolutionary constraints encompassing approximately 80% of enzyme structures, with conservation decreasing approximately linearly with increasing distance from the active site [26]. This conservation gradient extends up to 27.5Å from catalytic residues, highlighting the pervasive influence of functional sites on protein evolution.

In contrast, allosteric sites display remarkable evolutionary plasticity. Systematic mutagenesis studies of the tetracycline repressor (TetR) revealed that residues critical for allosteric signaling are surprisingly poorly conserved, while those required for structural integrity remain highly conserved [28]. This suggests evolution selects for protein fold preservation over maintenance of specific allosteric pathways, with multiple mutational solutions capable of satisfying the thermodynamic conditions required for cooperativity [28].

Experimental Methodologies for Site Characterization

Deep Mutational Scanning for Allosteric Plasticity Assessment

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Functional Site Analysis

| Method | Application | Key Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning | High-throughput mapping of allosteric functional landscapes [28] | Fold induction, allosteric switchability, rescue efficiency |

| Function-Centric "Disrupt-and-Restore" | Elucidating allosteric compensation mechanisms [28] | Identification of compensatory mutations, functional plasticity indices |

| Machine Learning Classification | Distinguishing stability vs. function-related variants [27] | SBI (stable but inactive) variant classification, functional residue prediction |

| Conservation Gradient Analysis | Quantifying long-range evolutionary constraints [26] | Distance-based conservation slopes, shell-specific evolutionary rates |

| Structural Conservation Mapping | Identifying putative allosteric pockets across protein families [29] | Pocket coverage metrics, structural conservation scores |

Protocol 1: Deep Mutational Scanning of Allosteric Signaling

The function-centric "disrupt-and-restore" strategy provides a powerful approach for mapping allosteric functional landscapes [28]. This methodology involves:

Library Construction: Using chip oligonucleotides to encode a comprehensive library of point mutants through single-site saturation mutagenesis (approximately 3,900 variants for a 207-residue protein).

Disruption Phase: Screening for "dead" variants that have lost allosteric switchability but retain structural integrity and DNA-binding capability, confirmed through clonal validation.

Restoration Phase: Constructing secondary protein-wide single-site saturation mutant libraries on dead variant backgrounds and sorting for functionally "rescued" variants that restore allosteric inducibility.

Functional Quantification: Calculating fold induction (ratio of expression with/without inducer) for individual clones, with wild-type TetR typically showing 47-fold induction and dead variants approximately 1.0-fold induction.

This approach demonstrated that allosteric signaling exhibits high functional plasticity and redundancy, with compensatory mutations occurring both locally (10-20Å) and distally (40-50Å) from inactivation sites [28].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning Identification of Functional Residues

A robust computational methodology combines evolutionary information with biophysical models to distinguish functional residues from those important for stability [27]:

Feature Selection:

- Predicted change in thermodynamic stability (ΔΔG) using Rosetta

- Evolutionary sequence information scores (ΔΔE) using GEMME

- Residue hydrophobicity

- Weighted contact number

Model Training: Utilizing gradient boosting classifiers trained on multiplexed assay of variant effects (MAVEs) data that simultaneously probe cellular abundance and functional effects.

Variant Classification: Categorizing variants into wild-type-like, total loss, stable but inactive (SBI), and low abundance with high activity classes.

Residue-Level Analysis: Assigning functional residue status when ≥50% of substitutions at a position are SBI variants, indicating direct functional roles independent of stability effects.

This approach successfully identifies catalytic sites, substrate interaction regions, and potential allosteric interfaces while differentiating from stability-constrained residues [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Functional Site Characterization

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Chip Oligonucleotides (Twist Biosciences) | Saturation mutagenesis library generation [28] | Pre-specified single mutations; comprehensive coverage |

| AR-Pred Software | Prediction of active and allosteric site residues [30] | Integrates dynamics, evolutionary, and physicochemical features |

| PASSer Platform | Allosteric site prediction [17] | Combines deep learning and molecular dynamics |

| AlloReverse Tool | Allosteric communication analysis [17] | Identifies allosteric pathways and residues |

| GEMME Algorithm | Evolutionary analysis and conservation scoring [27] | Provides evolutionary information scores (ΔΔE) |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Evolutionary Conservation Gradient

Evolutionary Conservation Gradient Diagram

Disrupt-and-Restore Experimental Workflow

Disrupt-and-Restore Experimental Workflow

Therapeutic Implications and Drug Discovery Applications

The evolutionary divergence between orthosteric and allosteric sites carries profound implications for therapeutic development. The high conservation of orthosteric sites across protein families presents challenges for achieving selectivity, particularly when targeting closely related proteins with similar active sites. In contrast, the evolutionary diversity of allosteric sites enables the development of highly specific modulators that can distinguish between even closely related protein subtypes [4] [25].

This selectivity advantage is demonstrated by several clinical successes. In chronic myeloid leukemia treatment, the allosteric modulator asciminib demonstrated a major molecular response rate of 25.5% compared to 13.2% for the orthosteric inhibitor bosutinib [4]. Similarly, the allosteric MEK inhibitor trametinib achieved superior potency with 7.2 times the pMEK/uMEK ratio at more than 14 times lower concentration compared to the orthosteric inhibitor selumetinib [4]. These examples underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting evolutionarily diverse allosteric sites.

The functional plasticity of allosteric networks also provides strategic advantages for combating drug resistance. While orthosteric site mutations frequently confer resistance through direct interference with drug binding, allosteric networks offer multiple compensatory pathways. Research demonstrates that allosteric dysfunction can be rescued through myriad mutational combinations, suggesting that resistance development against allosteric drugs may be less probable or require more complex mutational patterns [28] [25].

The comparative analysis of evolutionary conservation between active orthosteric sites and diverse allosteric sites reveals fundamental principles governing protein evolution and function. Orthosteric sites display strong evolutionary conservation driven by direct functional requirements, while allosteric sites exhibit remarkable evolutionary plasticity with compensatory mutational networks. These distinctions directly inform drug discovery strategies, with orthosteric targeting offering broad inhibition and allosteric modulation providing enhanced specificity and potential resistance management.

The experimental methodologies outlined—including deep mutational scanning, function-centric disrupt-and-restore approaches, and integrated machine learning models—provide researchers with robust tools for characterizing functional sites and their evolutionary constraints. As structural biology and computational prediction methods continue advancing, systematic exploitation of allosteric site diversity represents a promising frontier for developing next-generation therapeutics with optimized selectivity and safety profiles.

Discovery Tools and Therapeutic Implementation: From Computational Design to Clinical Applications

Allosteric regulation is a fundamental mechanism in biology where ligand binding at a site distal from the active site (the orthosteric site) modulates protein function through conformational changes or dynamic adjustments [17]. The therapeutic interest in allosteric drugs has surged due to their distinct advantages over traditional orthosteric drugs, including enhanced specificity, reduced off-target effects, and the ability to fine-tune protein activity rather than completely inhibit it [11] [31] [5]. From a drug discovery perspective, allosteric sites are often less conserved across protein families than highly conserved orthosteric sites, offering a path to develop highly selective modulators for specific protein subtypes [31] [5]. This is particularly valuable for challenging drug targets like GPCRs and kinases, where achieving subtype selectivity with orthosteric compounds has proven difficult [31].

The core challenge, however, lies in identifying these often "cryptic" allosteric sites, which may only become apparent in specific conformational states of the protein [32] [33]. Unlike orthosteric sites, which can frequently be identified from static structures, allosteric sites require an understanding of protein dynamics and conformational landscapes [11] [34]. This has driven the development and application of sophisticated computational methodologies—notably Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, enhanced sampling techniques, and Machine Learning (ML)—to detect and characterize allosteric sites, thereby accelerating allosteric drug discovery [32] [31] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Methodologies

The identification of allosteric sites relies on computational approaches that can capture protein dynamics and decode complex allosteric communication networks. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary methodological families.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Approaches for Allosteric Site Detection

| Methodology | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Tools/Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Solves Newton's equations of motion to simulate atomic-level protein movements over time [32]. | Provides high-resolution, time-resolved dynamics; Captures transient states and cryptic pockets; No prior knowledge of allosteric sites required [32] [17]. | Computationally expensive; Sampling limited by timescale barriers (nanoseconds to microseconds); Analysis of massive datasets can be complex [31] [33]. | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, GA-MD [34] [33] |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Applies bias potentials to accelerate exploration of conformational space and overcome energy barriers [32] [17]. | Enables observation of rare events and barrier crossings; Reveals hidden allosteric sites; More efficient than conventional MD [32] [35]. | Performance depends on choice of Collective Variables (CVs); Identifying optimal CVs is challenging; Can be technically complex to set up [35]. | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling, aMD, REMD [32] [17] |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Uses algorithms to learn patterns from large datasets of protein structures, sequences, and dynamics [31] [34]. | Can integrate diverse data types (sequence, structure, dynamics); High prediction speed once trained; Identifies non-obvious, complex patterns [31] [33]. | Dependent on quality and quantity of training data; Model interpretability can be low; Risk of poor generalizability if training data is biased [31]. | PASSer, AlloReverse, RHML framework, Graph Neural Networks [31] [34] [33] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

A significant trend in modern allosteric research is the integration of the above methodologies into cohesive pipelines that leverage their complementary strengths.

An Integrated ML-MD Workflow for GPCR Allostery

A pioneering study on the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) demonstrated a robust pipeline combining enhanced sampling MD and an interpretable Machine Learning model to discover a novel allosteric site [33]. The following diagram outlines this integrative workflow:

Figure 1: Integrative ML-MD workflow for allosteric site discovery in β2AR [33].

Detailed Protocol:

- System Setup and Enhanced Sampling: The protocol begins with an atomic model of the target protein (e.g., from crystallography or AlphaFold). Extensive Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) simulations are performed (e.g., multiple replicates totaling microseconds) to enhance conformational sampling and construct a broad conformational landscape [33].

- Conformational Clustering with ML: The massive MD trajectory is analyzed using a Residue-intuitive Hybrid Machine Learning (RHML) framework. This involves:

- Unsupervised Clustering (k-means): Automatically groups structurally similar conformations from the trajectory without predefined labels.

- Interpretable Supervised Learning (CNN): A Convolutional Neural Network is trained on the clusters to create a multi-classifier. Model interpretation techniques, like LIME, identify which specific residues contribute most to classifying the distinct conformational states [33].

- Allosteric Site Identification: The conformational state predicted to have an open allosteric pocket is selected. Computational solvent mapping (FTMap) and the residue importance list from the ML model are used to pinpoint the precise location and residues constituting the cryptic allosteric site [33].

- Virtual Screening and Mechanistic Analysis: The predicted site is used to screen compound libraries for potential allosteric modulators. The binding mode and allosteric mechanism of hit compounds are then probed using conventional MD (cMD), binding free energy calculations (MM/GBSA), and protein structure network (PSN) analysis to understand the communication pathway between the allosteric and orthosteric sites [33].

- Experimental Validation: Finally, the predicted allosteric site and modulators are validated through cell-based functional assays (e.g., cAMP accumulation) and site-directed mutagenesis of the identified allosteric residues, closing the loop between computation and experiment [33].

Advanced Sampling with True Reaction Coordinates

Another protocol focuses on the critical challenge of sampling rare conformational transitions. A novel method uses True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs) to guide enhanced sampling [35].

Detailed Protocol:

- Identification of True Reaction Coordinates (tRCs): Instead of relying on intuition, tRCs are computed from energy relaxation simulations starting from a single protein structure. The Generalized Work Functional (GWF) method is used to generate an orthonormal coordinate system that disentangles the few essential tRCs—which control both conformational change and energy relaxation—from other non-essential coordinates [35].

- Biased Sampling along tRCs: A bias potential (e.g., in metadynamics) is applied specifically to the identified tRCs. This focuses energy input into the degrees of freedom that actually drive the functional conformational change, leading to highly efficient and physiologically relevant barrier crossing [35].

- Generation of Natural Reactive Trajectories (NRTs): Biasing the tRCs generates trajectories that follow natural transition pathways. These can be used to harvest unbiased NRTs via Transition Path Sampling (TPS), providing atomic-level insight into the transition mechanism, such as allosteric communication during ligand dissociation [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful application of these computational protocols relies on a suite of software tools and databases. The following table details key resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Allosteric Research

| Reagent/Solution | Type | Primary Function in Allostery Research | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS/AMBER | MD Simulation Software | Provides the force fields and engines to run high-performance MD simulations, generating the primary trajectory data for analysis. | [32] |

| Plumed | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | Integrated with MD codes to implement advanced sampling algorithms like metadynamics and umbrella sampling by defining collective variables. | [17] |

| AlloSteric Database (ASD) | Knowledgebase | A curated repository of known allosteric proteins, modulators, and sites, used for training machine learning models and benchmarking predictions. | [31] |

| PASSer | Machine Learning Tool | A predictive platform for de novo prediction of allosteric sites using sequence and structural information. | [31] [17] |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | Provides highly accurate protein structure predictions, which can serve as starting points for MD simulations when experimental structures are unavailable. | [31] |

| FTMap | Mapping Software | Identifies hot spots for ligand binding on protein surfaces by computationally mapping small molecular probes, helping to validate predicted allosteric pockets. | [33] |

| GPCRmd | Database & Toolbox | A specialized database for GPCR MD simulations and analysis tools, crucial for studying allostery in this pharmaceutically important target family. | [31] |

Signaling Pathways and Allosteric Mechanisms

Allosteric modulators exert their effects by altering the conformational energy landscape of a protein. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of allosteric regulation from a dynamic and thermodynamic perspective.

Figure 2: The thermodynamic and dynamic mechanism of allosteric regulation. An allosteric modulator binds to and stabilizes a specific, low-population conformation within the protein's native ensemble. This binding event creates strain energy that propagates through the protein structure, ultimately shifting the conformational landscape at the orthosteric site and modulating its activity [11] [34] [17].

Mechanistic Insight: This model moves beyond rigid structural changes. The propagation of dynamic changes can occur through networks of correlated motions, often analyzed using methods like Dynamic Cross-Correlation (DCC) or Mutual Information (MI) from MD trajectories [36]. Allosteric drugs work not necessarily by inducing a single new structure, but by shifting the population of pre-existing conformational states, making techniques that capture these ensembles, like MD, essential for their discovery [11] [34].

The field of structural biology has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the simultaneous advancement of two powerful technologies: artificial intelligence-driven protein structure prediction, exemplified by AlphaFold, and high-resolution experimental determination through cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). These complementary approaches have dramatically expanded the structural universe available to drug discovery scientists, enabling structure-based drug design (SBDD) against targets previously considered intractable. For both orthosteric inhibitors that compete with native substrates at active sites and allosteric inhibitors that modulate protein function through distal sites, the availability of accurate protein structures has become a critical enabler. Where orthosteric drugs physically block active sites to completely inhibit protein function, allosteric drugs exploit natural regulatory mechanisms by binding to topographically distinct sites, offering advantages in specificity and the ability to fine-tune protein activity [37] [38]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates how AlphaFold-predicted and cryo-EM-determined structures perform across key metrics relevant to modern drug discovery, providing scientists with practical insights for selecting the appropriate structural platform for their specific research needs.

Technical Comparison: AlphaFold vs. Cryo-EM in Drug Discovery

Performance Characteristics and Limitations

Table 1: Technical comparison of AlphaFold and cryo-EM for structure-based drug design

| Parameter | AlphaFold | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Not applicable (computational model) | 1.2 Å - 4.0 Å (experimental resolution) [39] |

| Throughput | High (minutes to hours per structure) | Low (days to weeks per structure) [39] |

| Sample Requirements | None (requires only amino acid sequence) | 0.1-1.0 mg/mL protein concentration [39] |

| Hardware Requirements | High-performance computing clusters | $2-5 million microscope + supporting infrastructure |

| Structure Flexibility | Single, rigid conformational snapshot [37] [40] | Can capture multiple conformational states [39] |

| Ligand Binding Information | No inherent ligand information; pockets may be inaccurate [37] [40] | Can resolve bound ligands, substrates, and drugs natively |

| Best Applications | Target assessment, homology analysis, initial model generation | Ligand-bound complexes, membrane proteins, large complexes [41] [39] |

| Key Limitations | Poor performance on flexible regions and binding pockets [37] | Resolution limitations for small proteins (<100 kDa) [39] |

The comparative analysis reveals complementary strengths and limitations. AlphaFold provides unprecedented access to protein structures with minimal investment, generating models for the entire human proteome and numerous pathogen proteomes [42]. However, these models represent single conformational states without the inherent flexibility crucial for understanding drug binding. As noted by researchers, "AlphaFold is intrinsically unable to scan the vast landscape" of protein conformational ensembles [37]. This limitation particularly impacts binding site accuracy, as drug pockets often involve flexible loops and side-chain rearrangements upon ligand binding.

Cryo-EM delivers experimental structures closer to physiological conditions, with recent technical advances achieving resolutions as high as 1.2 Å [39]. The technique excels particularly for membrane proteins like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and large complexes that challenge crystallization approaches [41] [39]. However, cryo-EM requires substantial resources, specialized expertise, and remains challenging for proteins smaller than 100 kDa, though emerging techniques are gradually pushing this boundary downward [39].

Performance in Orthosteric vs. Allosteric Drug Discovery

Table 2: Application-specific performance metrics for orthosteric and allosteric inhibitor design

| Performance Metric | AlphaFold (Orthosteric) | AlphaFold (Allosteric) | Cryo-EM (Orthosteric) | Cryo-EM (Allosteric) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Accuracy | Moderate (requires refinement) [40] | Low (cryptic sites often missed) [38] | High (experimentally determined) | High (can identify cryptic sites) |

| Virtual Screening Utility | Limited without refinement [40] | Limited without refinement | Excellent for rigid docking | Excellent with conformational diversity |

| Structure Refinement Requirements | Mandatory (MD simulations, induced-fit docking) [40] | Extensive (ensemble generation, pathway analysis) | Minimal for high-resolution structures | Moderate (may require multiple states) |

| Success in Prospective Design | Demonstrated with refinement [40] | Limited reported success | Well-established [39] | Emerging (e.g., GPCR biased signaling) |

| Throughput for Large-scale Screening | High after initial refinement | Moderate after extensive processing | Low due to experimental burden | Low due to experimental burden |

The application-specific comparison reveals critical differences for orthosteric versus allosteric drug discovery. For orthosteric targeting, both platforms can provide valuable starting points, but cryo-EM structures generally offer more reliable binding sites without requiring extensive refinement. Industry assessments indicate that AlphaFold models used "out of the box" for virtual screening misclassify many active hits as decoys, though this can be improved through molecular dynamics-based induced fit docking [40].

For allosteric drug discovery, both platforms face inherent challenges. Allosteric sites are often cryptic—not visible in static structures—and emerge only during conformational transitions [38]. AlphaFold's single-conformation prediction frequently misses these transient pockets, while cryo-EM can potentially capture multiple states but requires substantial resources to do so systematically. Successful allosteric design typically requires ensemble representations of protein dynamics, which neither technique provides directly [37] [38].

Experimental Applications and Validation

Case Study: Integrated Approach for CCR2 Inhibitor Design

A recent study demonstrates how computational and experimental approaches can be integrated for allosteric and orthosteric drug discovery. Researchers targeting CCR2 for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis employed a hybrid methodology combining structure-based pharmacophore modeling, 3D-QSAR, and large-scale virtual screening of over 150,000 molecules [8]. The workflow identified two selective small-molecule inhibitors: compound 17 targeting the orthosteric site with binding free energy of -30.91 kcal mol⁻¹, and compound 67 binding an allosteric site with -26.11 kcal mol⁻¹ free energy [8].

Validation experiments confirmed the computational predictions through multiple orthogonal methods. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measured compound 17's direct binding to murine CCR2 (K_D = 3.46 μM), while molecular dynamics simulations, principal component analysis, and umbrella sampling confirmed stable binding conformations [8]. In cellular models, both compounds significantly reduced hydroxyproline and COL1A1 levels while upregulating ELN expression, with compound 17 showing comparable antifibrotic efficacy to the positive control nintedanib [8]. This case study exemplifies a robust experimental framework for validating computationally-predicted protein-ligand interactions.

Emerging Hybrid Methodologies

The distinction between computational and experimental structural biology is increasingly blurring with emerging hybrid approaches. The MICA (Multimodal Integration of Cryo-EM and AlphaFold) platform demonstrates how deep learning can integrate both data types, using cryo-EM density maps and AlphaFold3-predicted structures as input to build more accurate protein models than either method alone [43]. This integration compensates for limitations in each individual modality—low-resolution or missing regions in cryo-EM maps and incorrectly predicted regions in AlphaFold structures [43].

In performance evaluations, MICA achieved an average TM-score of 0.93 on high-resolution cryo-EM maps, significantly outperforming single-modality approaches [43]. Such integrated methodologies represent the future of structural biology, leveraging the complementary strengths of both experimental and computational approaches.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for structure-based drug design

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Functionality | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | AlphaFold Database [42] [38] | >200 million predicted structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [39] | Experimental structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ | |

| Allosteric Resources | Allosteric Database (ASD) [38] | Allosteric modulators, sites, pathways | http://allostery.net/ASD/ |

| AlloMAPS [38] | Allosteric communication energetics | https://allomaps.bii.a-star.edu.sg/ | |

| Site Prediction | AlloSite [38] | Machine learning-based allosteric site prediction | https://mdl.shsmu.edu.cn/AST/ |

| P2Rank/PrankWeb [38] | General binding site identification | https://prankweb.cz/ | |

| Simulation & Docking | Molecular Dynamics (MD) [8] [38] | Binding stability and conformational sampling | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD |

| Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [42] [40] | Binding affinity predictions | Schrödinger, OpenMM | |