PICADAR in Focus: A Critical Analysis of Sensitivity and Specificity for PCD Diagnosis

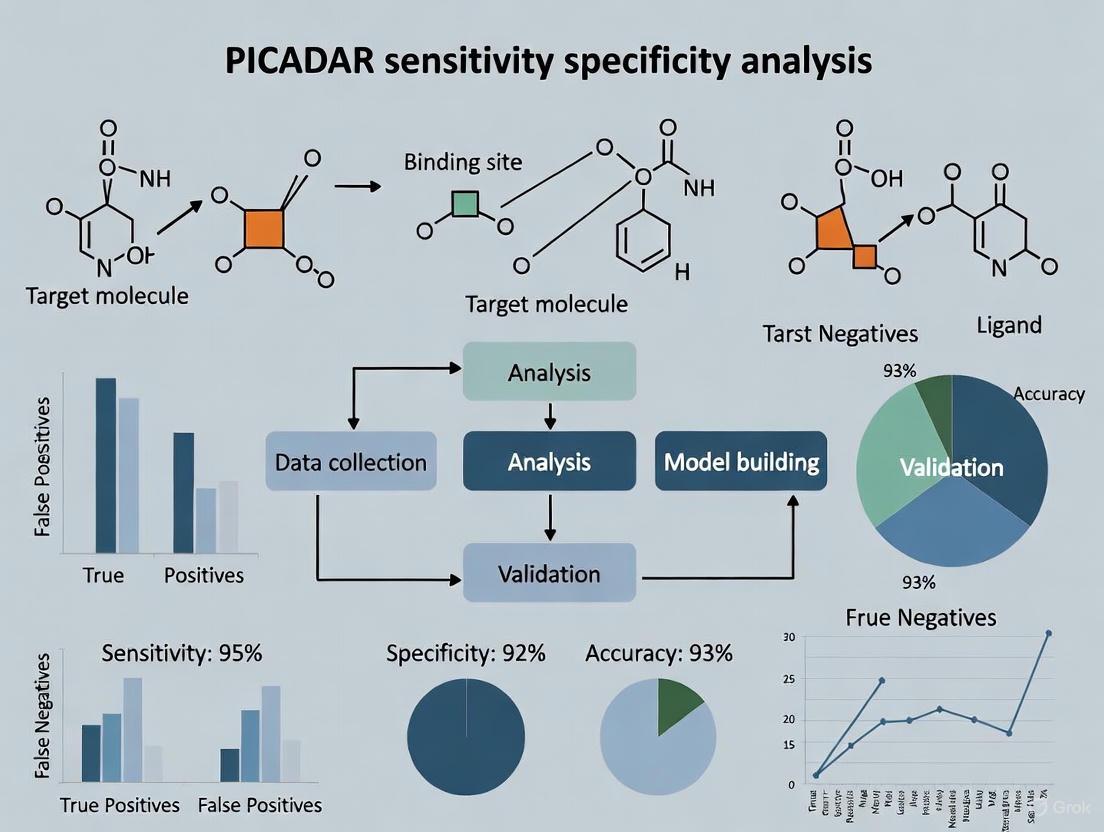

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the PICADAR score, a clinical prediction tool for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD).

PICADAR in Focus: A Critical Analysis of Sensitivity and Specificity for PCD Diagnosis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the PICADAR score, a clinical prediction tool for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD). It explores the foundational concepts of diagnostic test accuracy, details PICADAR's methodology, and presents recent evidence on its performance limitations, particularly its variable sensitivity across patient subgroups. Aimed at researchers and clinicians, the content evaluates PICADAR against emerging alternatives and discusses its implications for optimizing diagnostic pathways and patient selection in clinical practice and drug development.

Understanding Diagnostic Accuracy and the PICADAR Tool

This guide provides an objective analysis of the performance metrics of diagnostic tools, focusing on the PrImary Ciliary DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) within the context of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) diagnosis. We examine the foundational principles of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, and apply these to compare PICADAR's established benchmarks against recent validation studies. Quantitative data are synthesized to reveal critical limitations in test sensitivity across patient subgroups, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for diagnostic protocol selection and evaluation.

Diagnostic test accuracy is fundamental to clinical decision-making and therapeutic development. The performance of any diagnostic tool is quantified by its sensitivity—the ability to correctly identify individuals with the disease—and specificity—the ability to correctly identify those without the disease [1]. These metrics, along with positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), provide a framework for evaluating a test's real-world utility and limitations [2]. Sensitivity represents the proportion of true positives detected by the test among all individuals with the condition, calculated as True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) [1]. Conversely, specificity represents the proportion of true negatives among all disease-free individuals, calculated as True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) [1]. In screening contexts, these metrics must be interpreted with an understanding of their inherent trade-offs and their relationship to disease prevalence in the target population [2].

The diagnostic landscape for rare diseases presents particular challenges, where imperfect reference standards and phenotypic heterogeneity can significantly impact measured test performance [3]. This analysis uses PICADAR, a predictive tool for primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), to illustrate these core diagnostic principles with empirical data, highlighting how test performance varies across patient populations and clinical settings.

Core Diagnostic Metrics: Definitions and Calculations

Foundational Formulas and Relationships

The validity of a diagnostic test is determined through direct comparison with a reference standard, which represents the best available assessment of the true disease status [2]. The interrelationships between diagnostic metrics are visualized through a standard 2x2 contingency table, from which all accuracy calculations derive.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Test Calculation Framework. PPV: Positive Predictive Value; NPV: Negative Predictive Value.

Critical Distinctions in Metric Interpretation

Healthcare providers must recognize crucial distinctions between these metrics. Sensitivity and specificity are considered stable test attributes that describe its performance relative to a reference standard, while predictive values determine the probability that a test result correctly classifies a patient's condition and are influenced by disease prevalence [1] [2]. This prevalence dependence means that even tests with high sensitivity and specificity can yield misleading predictive values when applied to populations with drastically different disease prevalence than the original validation cohort.

A critical and often misunderstood relationship exists between sensitivity and PPV. Sensitivity describes a test's performance among people known to have the disease (reference standard positive), whereas PPV describes the test's performance among people who test positive on the screening test [2]. This distinction fundamentally impacts how test results should be interpreted in both clinical practice and research settings, particularly for disorders like PCD where prevalence varies across populations and healthcare settings.

PICADAR: Original Development and Validation

Tool Development and Methodology

The Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule (PICADAR) was developed as a practical clinical tool to identify patients requiring specialized PCD testing [4]. Developed through analysis of 641 consecutive referrals to a PCD diagnostic center, the tool aims to streamline referral pathways by utilizing readily obtainable clinical history rather than specialized equipment. The original study employed logistic regression to identify predictive parameters from 27 potential variables, ultimately selecting seven key clinical features for inclusion in the final model [4].

Table 1: Original PICADAR Predictive Parameters and Scoring System

| Predictive Parameter | Points |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation | 1 |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | 1 |

| Neonatal intensive care admission | 2 |

| Chronic rhinitis | 1 |

| Ear symptoms | 1 |

| Situs inversus | 2 |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 4 |

| Total Possible Score | 12 |

PICADAR incorporates an initial gatekeeping question about persistent wet cough. Patients without this symptom are excluded from further scoring, while those with persistent wet cough proceed through the seven-item evaluation [5] [6]. The total score determines the probability of PCD, with the originally recommended referral threshold set at ≥5 points [4].

Original Performance Claims

In its original validation, PICADAR demonstrated strong diagnostic performance in both derivation and external validation cohorts, supporting its adoption into clinical guidelines.

Table 2: Originally Reported PICADAR Performance Metrics

| Metric | Derivation Cohort | External Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Specificity | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0.91 | 0.87 |

| Population | 641 referrals (75 PCD+) | 187 patients (93 PCD+) |

The original research reported excellent discrimination with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.91 in the derivation group and 0.87 in external validation [4]. Based on these findings, the European Respiratory Society incorporated PICADAR into diagnostic guidelines as a recommended tool for estimating PCD likelihood prior to specialized testing.

Contemporary Analysis of PICADAR Performance

Recent Validation Study Methodology

A 2025 study led by Schramm et al. conducted a rigorous re-evaluation of PICADAR's sensitivity in a genetically confirmed PCD cohort [5] [6]. The investigation analyzed 269 individuals with definitive genetic diagnoses of PCD, applying the standard PICADAR scoring protocol to calculate sensitivity based on the recommended ≥5 point threshold. Subgroup analyses examined how test performance varied by the presence of laterality defects (situs inversus or heterotaxy) and hallmark ultrastructural ciliary defects [5].

The experimental protocol followed these key steps:

- Patient Selection: 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD provided the reference standard

- Data Collection: Clinical history necessary for PICADAR scoring obtained from medical records

- Scoring Application: PICADAR scores calculated according to published algorithms

- Sensitivity Calculation: Proportion of patients with scores ≥5 points determined

- Stratified Analysis: Performance calculated across subgroups based on laterality and ultrastructural status

This methodology provided a robust framework for assessing real-world PICADAR performance against a genetic gold standard, particularly in patient subgroups that may not exhibit classic PCD phenotypes.

Revealed Limitations in Test Sensitivity

The 2025 validation revealed significant limitations in PICADAR's sensitivity, particularly in key patient subgroups. The overall sensitivity of 75% (202/269) fell substantially below originally reported values [5] [6]. Most notably, 7% (18/269) of genetically confirmed PCD patients were excluded by PICADAR's initial gatekeeping question due to absence of daily wet cough [5].

Table 3: Stratified Sensitivity Analysis of PICADAR in Genetically Confirmed PCD

| Patient Subgroup | Sensitivity | Median Score (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Cohort | 75% (202/269) | 7 (5-9) |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 (8-11) |

| Situs Solitus (Normal Laterality) | 61% | 6 (4-8) |

| Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | Not reported |

| Normal Ultrastructure | 59% | Not reported |

The stratified analysis demonstrated dramatically different performance across phenotypic presentations. While sensitivity reached 95% in patients with laterality defects, it dropped to just 61% in those with normal organ arrangement (situs solitus) [5] [6]. Similarly, patients without hallmark ultrastructural defects on transmission electron microscopy showed significantly lower sensitivity (59%) compared to those with definitive ultrastructural abnormalities (83%) [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

PICADAR Versus Alternative Diagnostic Approaches

PCD diagnosis typically employs a multi-test algorithm rather than reliance on a single modality. The comparative performance characteristics of available diagnostic methods reveal complementary strengths and limitations.

Table 4: Comparative Diagnostic Modalities in PCD Evaluation

| Diagnostic Method | Typical Sensitivity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| PICADAR Score | 75% (61-95% by subgroup) | Low sensitivity in situs solitus and normal ultrastructure cases |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | High (variable by genotype) | Requires expensive equipment and patient cooperation |

| Genetic Testing | >90% for known genes | Limited by unidentified genes; expensive; complex interpretation |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | ~70% | Misses ultrastructurally normal PCD; requires expertise |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy | High for motile cilia | Limited availability; secondary dyskinesia confounds |

The tabular comparison illustrates that PICADAR serves as an accessible initial screening tool but requires supplementation with more specialized testing for definitive diagnosis, particularly given its variable sensitivity across genotypic and phenotypic presentations [7]. This comprehensive diagnostic approach acknowledges the absence of a single gold standard test for PCD, instead relying on congruent findings across multiple modalities to establish diagnosis [7].

Impact of Phenotypic and Genotypic Diversity

The performance variations observed in PICADAR highlight a fundamental challenge in rare disease diagnostics: the influence of population heterogeneity on test accuracy. The tool demonstrates substantially different performance across ethnic populations, as illustrated by a Japanese study where only 25% of PCD patients exhibited situs inversus compared to approximately 50% in Western cohorts [8]. This discrepancy reflects differences in the distribution of causative genetic mutations across populations, with corresponding impacts on phenotypic presentation and, consequently, on PICADAR scores [8].

The dependency on laterality features creates particular challenges for diagnosing PCD in patients with normal organ arrangement, who represent a growing proportion of identified cases as genetic testing expands. These findings underscore the necessity of considering local genotype-phenotype correlations when implementing diagnostic prediction rules across diverse populations and healthcare settings.

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Diagnostic Research

Table 5: Essential Research Materials for PCD Diagnostic Development

| Reagent/Technology | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Sequencing Panels | Detection of mutations in >50 PCD-associated genes | Definitive diagnosis; genotype-phenotype correlation |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | Visualization of ciliary ultrastructure | Identification of hallmark defects (ODA, IDA, MTD) |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy | Analysis of ciliary beat pattern and frequency | Functional assessment of ciliary motility |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide Systems | Measurement of nNO production | Screening; typically low nNO in PCD |

| Immunofluorescence Assays | Protein localization in ciliary apparatus | Detection of missing axonemal proteins |

| Air-Liquid Interface Cell Culture | Ciliary differentiation and regeneration | Exclusion of secondary dyskinesia |

The research reagents and technologies outlined in Table 5 represent essential components for comprehensive PCD diagnostic development and validation [7]. These tools enable multimodal assessment that accounts for the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity characteristic of PCD, providing orthogonal verification methods necessary for robust test validation.

Diagnostic Workflow Integration

The following diagram illustrates how diagnostic modalities integrate within a comprehensive PCD evaluation pathway, highlighting decision points and complementary test relationships:

Diagram 2: Comprehensive PCD Diagnostic Pathway. NO: nitric oxide.

The analysis of PICADAR within the framework of diagnostic test principles reveals both utility and significant limitations. While offering an accessible initial screening method with good specificity, its variable sensitivity—particularly in patients with situs solitus (61%) or normal ciliary ultrastructure (59%)—limits its reliability as a standalone tool [5] [6]. These findings underscore the necessity of context-specific test interpretation and the importance of understanding how phenotypic and genotypic variations impact diagnostic performance.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights highlight several critical considerations: the imperative of population-specific validation, the limitations of clinical prediction rules in genetically heterogeneous disorders, and the necessity of multimodal diagnostic approaches when no single gold standard test exists. Future diagnostic development should focus on creating complementary tools that address PICADAR's sensitivity gaps, particularly for patients without classic laterality defects, to ensure equitable diagnostic access across all PCD phenotypes and genotypes.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disease characterized by abnormal ciliary function, leading to impaired mucociliary clearance and subsequent chronic infections of the upper and lower airways [9]. With an estimated prevalence of 1:10,000-1:20,000 and over 50 identified causative genes, PCD presents substantial diagnostic challenges [9] [7]. The disease manifests with heterogeneous clinical presentations, often combining persistent wet cough, chronic rhinosinusitis, recurrent otitis media, bronchiectasis, and laterality defects such as situs inversus (present in approximately 50% of patients) [9] [7]. A critical challenge is that the vast majority of PCD patients remain undiagnosed, creating a major obstacle to delivering appropriate care [9]. This diagnostic gap persists despite advances in understanding the genetic basis and pathophysiology of PCD, highlighting the urgent need for effective screening strategies and standardized diagnostic protocols.

Diagnostic delays remain significant, with patients often experiencing over 40 medical visits for PCD-related symptoms before referral for specialized testing [9]. The median age at diagnosis is 13 years, with a four-year gap between initial suspicion and confirmatory testing [10]. This delay is particularly problematic as late diagnosis associates with decreased lung function and poorer prognosis due to irreversible structural lung damage [10]. Early identification and treatment are therefore essential to prevent bronchiectasis and preserve lung function, underscoring the clinical imperative for effective screening methodologies in at-risk populations.

The Complex Diagnostic Landscape: Available Tools and Their Limitations

PCD diagnosis lacks a single gold standard test, requiring instead a combination of technically demanding investigations [11] [7]. The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines recommend a multi-test algorithm incorporating clinical features, nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing [11]. This combinatorial approach is necessary because each test has distinct limitations in sensitivity, specificity, and technical requirements. The diagnostic landscape is further complicated by variations in test availability across different healthcare systems, with limited access to specialized PCD diagnostic centers in many regions [9] [10]. Centralized care facilities managing over 20 PCD patients have demonstrated diagnosis at earlier ages, emphasizing the importance of specialized expertise and high patient throughput [9].

Table 1: Diagnostic Tests for PCD and Their Performance Characteristics

| Diagnostic Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | 91% [12] | 96% [12] | Less reliable in children <5-6 years; requires patient cooperation; not disease-specific [11] [12] |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) | 100% [12] | 93% [12] | Requires significant expertise; secondary ciliary dyskinesia can mimic PCD [9] [12] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | ~79% [13] | 100% [12] | Misses 15-30% of PCD cases with normal ultrastructure; technical complexity [9] [13] |

| Genetic Testing | 60-70% (for known genes) [9] | High (varies) | Incomplete knowledge of all PCD genes; variants of uncertain significance [9] [10] |

Technical Challenges and Standardization Issues

Each diagnostic modality faces significant technical challenges that impact its reliability and implementation. For nNO measurement, cut-off values vary considerably between centers due to differences in equipment, techniques, and patient age [9]. Although a cut-off of 77 nL·min⁻¹ has shown disease-specific discriminatory value in multiple sites when using standardized protocols, consensus on appropriate thresholds for children under 6 years remains lacking [9]. For HSVA, ciliary beat pattern analysis is observer-dependent, and standardizing terminology for different beat patterns presents ongoing challenges [9]. Subtle ciliary abnormalities are difficult to differentiate from secondary defects caused by infection or inflammation, often requiring repeat testing or air-liquid interface (ALI) culture to confirm primary defects [11] [12].

TEM faces quantitative challenges in determining the minimal number of cilia that must be scored and standardized terminology for ultrastructural defects [9]. Furthermore, 15-20% of confirmed PCD cases have normal ciliary ultrastructure despite causative genetic mutations, limiting TEM's sensitivity as a standalone test [9] [13]. Genetic testing continues to evolve as new PCD-related genes are discovered, but current panels identify mutations in only 60-70% of clinically confirmed cases [9]. The absence of a gold standard creates circularity in validating new genetic discoveries, as case definition typically requires abnormal HSVA or TEM findings [9].

PICADAR: A Validated Clinical Tool for Targeted Screening

Development and Implementation

The PCD Rule (PICADAR) is a clinical predictive tool developed to identify patients at high risk for PCD who should be referred for specialized diagnostic testing [9] [11]. This validated scoring system uses seven clinical features to calculate a probability score for PCD: neonatal chest symptoms, neonatal respiratory support, situs inversus, congenital cardiac defect, persistent perennial rhinitis, chronic ear symptoms, and chronic nasal symptoms [14]. PICADAR was developed through systematic analysis of clinical features in genetically confirmed PCD cases and validated in consecutive referrals for PCD testing [9]. The tool provides a simple, evidence-based method for general practitioners and pediatricians to identify appropriate candidates for specialist referral, potentially reducing diagnostic delays and unnecessary testing in low-probability cases.

The European Respiratory Society guidelines suggest using predictive tools like PICADAR in combination with distinct PCD symptoms to identify patients for diagnostic testing [11]. This recommendation acknowledges that no single clinical feature is pathognomonic for PCD, but specific combinations can strongly suggest the diagnosis. For neonates, the combination of lobar collapse, situs inversus, and/or persistent oxygen therapy for over 2 days in term newborns with respiratory distress can accurately predict PCD [9]. The diagnosis should also be considered in term neonates with normal situs but unexplained respiratory distress, as over 70% of PCD patients suffer from neonatal respiratory symptoms [9].

Performance and Comparative Analysis

PICADAR demonstrates robust performance characteristics as a screening tool. In validation studies, it effectively stratifies patients by disease probability, helping to prioritize specialist referrals in resource-constrained settings [9]. The tool's structured approach standardizes the clinical assessment for PCD suspicion, reducing reliance on individual clinician experience and awareness. When compared to other screening methods, PICADAR offers the advantage of being rapidly applicable during routine clinical encounters without requiring specialized equipment or technical expertise, making it particularly valuable in primary and secondary care settings where access to nNO, HSVA, TEM, and genetic testing may be limited.

Table 2: Comparison of Screening and Diagnostic Approaches for PCD

| Method | Primary Use | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR | Clinical screening | No specialized equipment needed; rapid application; validated predictive value | Relies on accurate history; less effective without classic symptoms |

| Nasal NO | Screening/Diagnostic | High specificity in children >6 years; non-invasive | Limited in young children; requires specialized equipment; false negatives in some genotypes |

| HSVA | Diagnostic | Direct functional assessment; high sensitivity | Requires expertise; secondary changes affect interpretation |

| TEM | Diagnostic | High specificity; identifies structural defects | Misses normal ultrastructure cases; invasive sampling |

| Genetic Testing | Diagnostic/Confirmatory | Definitive when pathogenic mutations identified; enables family screening | 30-40% of cases have no identified mutation; cost and accessibility |

Analytical Frameworks: Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Diagnostic Protocols

Comprehensive PCD diagnostic testing follows standardized protocols to ensure accurate and reproducible results. For nNO measurement, the ERS guidelines recommend using a chemiluminescence analyzer with a velum closure technique during breath-hold in children over 6 years and adults, while suggesting tidal breathing measurements for children under 6 years [11]. Measurements should be performed when patients are free of acute respiratory infections, typically waiting at least 4 weeks after infection resolution [12]. For HSVA, ciliated epithelial samples obtained via nasal brush biopsy are analyzed using high-speed cameras recording at 500 frames per second, with qualitative assessment of ciliary beat pattern and quantitative measurement of ciliary beat frequency [12]. Expert microscopists analyze at least six healthy strips of ciliated epithelium, with abnormal patterns including static, uncoordinated, rotational, or reduced amplitude beating [12].

TEM analysis requires examination of at least 100 cilia in transverse section at 60,000x magnification, with quantitative assessment of axonemal structure using center-specific normative data [12]. Hallmark ultrastructural defects include outer dynein arm (ODA) absence, combined ODA and inner dynein arm (IDA) absence, and microtubular disorganization with IDA defects [10]. When initial results are inconclusive or show secondary dyskinesia, repeat testing following air-liquid interface (ALI) culture is recommended to exclude acquired defects and confirm primary ciliary abnormalities [11] [12]. Genetic testing approaches have evolved from candidate gene analysis to next-generation sequencing panels covering all known PCD-related genes, with classification of identified variants according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PCD Diagnostic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence NO Analyzer | nNO measurement | Quantifies nasal nitric oxide concentration | Use velum closure technique; establish center-specific reference values |

| High-Speed Camera System | HSVA | Records ciliary beating for pattern and frequency analysis | Minimum 500 fps; requires specialized analysis software |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | TEM | Visualizes ciliary ultrastructure at high resolution | Analyze ≥100 cilia cross-sections; quantitative assessment |

| Air-Liquid Interface Culture System | Ciliary culture | Differentiates primary from secondary ciliary defects | 3-4 week culture period; allows ciliary regeneration |

| Genetic Sequencing Panels | Genetic testing | Identifies mutations in PCD-associated genes | NGS panels should cover >50 known genes; confirm bi-allelic mutations |

| Glutaraldehyde Fixative | TEM sample preparation | Preserves ciliary ultrastructure for electron microscopy | 3% concentration; immediate fixation after sampling |

Visualizing Diagnostic Pathways and Genetic Relationships

PCD Diagnostic Decision Algorithm

PCD Diagnostic Decision Algorithm

Genetic Landscape of PCD Ultrastructural Defects

Genetic Associations with Ultrastructural Defects

The diagnostic landscape for PCD remains complex, requiring integration of multiple complementary approaches to achieve accurate diagnosis. PICADAR provides a valuable evidence-based screening tool to identify high-risk patients who warrant specialized testing, potentially reducing diagnostic delays and improving resource allocation. However, even with optimal screening, definitive diagnosis requires sophisticated testing available only at specialized centers. The limitations of individual diagnostic modalities—including the inability of TEM to detect 15-30% of PCD cases with normal ultrastructure, the technical challenges of HSVA interpretation, and the incomplete coverage of current genetic panels—necessitate a combinatorial diagnostic approach.

Future directions in PCD diagnostics include the standardization of testing protocols across centers, validation of novel screening biomarkers, expansion of genetic panels as new disease genes are discovered, and development of targeted genetic testing for populations with founder mutations. Immunofluorescence staining of ciliary proteins shows promise as an emerging diagnostic adjunct that may help identify cases with normal ultrastructure [11] [7]. For researchers and clinicians, understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and appropriate applications of each diagnostic tool is essential for accurate PCD diagnosis and for advancing the development of more effective screening strategies. As genetic knowledge expands and technologies evolve, the diagnostic paradigm for PCD will continue to refine, hopefully leading to earlier diagnosis and improved clinical outcomes for patients with this heterogeneous genetic disorder.

The PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) is a clinical prediction tool developed to identify patients at high probability of having Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) before proceeding with complex, costly, and invasive diagnostic testing. This objective comparison guide details PICADAR's original development, stated objectives, and current performance metrics against other diagnostic approaches, providing researchers and clinicians with synthesized experimental data and methodological protocols essential for evaluating its utility in both clinical and research settings.

Original Development and Objectives

PICADAR was developed to serve as an accessible, evidence-based screening instrument for PCD, a rare genetic disease affecting approximately 1 in 7,500 to 1 in 20,000 live births [7]. The tool was created to address the significant diagnostic challenges posed by PCD, which requires specialized testing methods—such as nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing—that are not universally available and can be technically demanding [7].

The primary stated objective of PICADAR is to provide a systematic method for general practitioners and pediatricians to quantify the pre-test probability of PCD, thereby guiding appropriate referral to specialized centers. By identifying high-risk individuals efficiently, PICADAR aims to reduce diagnostic delays, which are common in PCD due to its nonspecific clinical presentation overlapping with more common respiratory conditions like asthma and recurrent bronchitis [7].

Performance Comparison with Alternative Diagnostic Approaches

The following tables synthesize quantitative performance data for PICADAR and alternative PCD diagnostic methods, compiled from recent validation studies.

| Diagnostic Tool | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Target Population | Study Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR (Score ≥5) | 75% (202/269) [6] | Not fully evaluated in recent studies | Genetically confirmed PCD patients | 269 [6] |

| PICADAR (Situs Solitus subgroup) | 61% [6] | N/A | PCD patients without laterality defects | Subgroup of 269 [6] |

| PICADAR (No hallmark ultrastructural defects) | 59% [6] | N/A | PCD patients with normal ultrastructure | Subgroup of 269 [6] |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | High (varies by method) [7] | High (varies by method) [7] | Patients with clinical suspicion of PCD | Variable across studies [7] |

| Genetic Testing | Evolving (>40-50 known genes) [7] | ~100% (for confirmed pathogenic variants) [7] | Patients with clinical suspicion of PCD | Variable across studies [7] |

Table 2: Subgroup Performance Analysis of PICADAR

| Patient Subgroup | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) | Sensitivity | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Genetically Confirmed PCD | 7 (IQR: 5-9) [6] | 75% (202/269) [6] | Reference |

| With Laterality Defects | 10 (IQR: 8-11) [6] | 95% [6] | p < 0.0001 [6] |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 6 (IQR: 4-8) [6] | 61% [6] | p < 0.0001 (vs. with laterality defects) [6] |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | Not specified | 83% [6] | p < 0.0001 [6] |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | Not specified | 59% [6] | p < 0.0001 (vs. with hallmark defects) [6] |

| Japanese PCD Cohort | Mean: 7.3 (range: 3-14) [8] | Not specified | Different patient demographics [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Recent Validation Study Protocol

A 2025 multi-center study conducted by Schramm et al. provides the most recent robust evaluation of PICADAR's performance, using the following methodological approach [6]:

- Study Population: 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD, ensuring an objective diagnostic standard.

- PICADAR Application: Researchers calculated PICADAR scores retrospectively based on clinical data. The tool consists of an initial gatekeeping question about the presence of daily wet cough, followed by seven additional questions for those who screen positive [6].

- Scoring Interpretation: A score of ≥5 points was used as the positive cutoff threshold as recommended in the original PICADAR development study.

- Statistical Analysis: Sensitivity was calculated as the proportion of genetically confirmed PCD patients who scored ≥5 on PICADAR. Subgroup analyses examined the impact of laterality defects (situs inversus versus situs solitus) and predicted hallmark ultrastructural defects on test performance [6].

PICADAR's Original Scoring Criteria

The PICADAR tool assesses the following clinical features, which reflect the typical presentation of PCD [7]:

- Initial Screening Question: Presence of daily wet cough (if negative, rules out PCD according to the tool's logic)

- Additional Scored Features:

- Neonatal respiratory symptoms at term birth

- Chest symptoms in the neonatal period

- Chronic rhinitis

- Persistent perennial rhinitis

- Hearing impairment or serous otitis media

- Situs inversus

- Congenital cardiac defect

PICADAR in the PCD Diagnostic Pathway

The diagnostic pathway for PCD illustrates how PICADAR serves as an initial clinical screening tool before advanced testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in PCD Research | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Ultrastructural analysis of ciliary defects [7] | Identifying ODA, IDA, microtubular disorganization, and central pair defects [7] |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVA) | Functional analysis of ciliary beat pattern and frequency [7] | Detecting dyskinetic, immotile, or uncoordinated ciliary motion [7] |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement | Non-invasive screening with high negative predictive value [7] | Differentiating PCD from other respiratory conditions (consistently low nNO in PCD) [7] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Panels | Genetic confirmation of PCD diagnosis [7] | Identifying mutations in >50 known PCD-associated genes (e.g., DNAH5, DNAH11, CCDC39, CCDC40) [7] |

| Immunofluorescence Assays | Protein localization and analysis [7] | Detecting absence or mislocalization of specific ciliary proteins resulting from genetic mutations [7] |

Genetic Signaling Pathways in PCD

The genetic complexity of PCD underpins the challenges faced by clinical prediction tools like PICADAR, as different genetic subtypes present with varying clinical features.

Critical Analysis and Research Implications

While PICADAR provides a valuable structured approach to PCD suspicion, recent evidence reveals significant limitations that researchers must consider when incorporating it into study designs or clinical protocols [6]:

Critical Sensitivity Gap: The finding that 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients were ruled out by the initial "daily wet cough" question alone highlights a fundamental limitation in the tool's design, potentially missing atypical presentations [6].

Demographic and Genetic Variability: The Japanese cohort study revealed a much lower rate of situs inversus (25% versus approximately 50% in Western populations), indicating that PICADAR's performance may vary significantly across different ethnic and genetic backgrounds [8]. This is particularly important for international clinical trials and genetic studies.

Ultrastructural Dependency: The significantly lower sensitivity (59%) in patients without hallmark ultrastructural defects indicates PICADAR may preferentially identify certain PCD genotypes over others, potentially introducing selection bias in research studies [6].

These limitations underscore the need for continued refinement of PCD prediction tools and the importance of using PICADAR as one component in a comprehensive diagnostic approach rather than as a definitive screening mechanism, particularly in research settings seeking to understand the full spectrum of PCD presentation.

The PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) is a clinical predictive tool designed to identify patients at high probability of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) who should be referred for specialized diagnostic testing [15]. This review deconstructs the PICADAR scorecard by examining its seven predictive parameters, analyzes its performance against subsequent validation studies, and details the experimental methodologies used in its development and evaluation. Evidence synthesized from foundational and recent critical studies demonstrates that while PICADAR provides a valuable structured screening approach, its sensitivity varies significantly across patient subgroups, particularly those without laterality defects or hallmark ultrastructural defects [5] [6]. This objective comparison provides researchers and clinicians with a comprehensive evidence-based framework for implementing PCD predictive tools in both research and clinical settings.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous, autosomal recessive disorder caused by mutations in over 50 genes encoding proteins essential for ciliary structure and function [7]. The disease impairs mucociliary clearance, leading to recurrent respiratory tract infections, chronic rhinosinusitis, otitis media, and bronchiectasis; approximately half of patients exhibit laterality defects including situs inversus or heterotaxy [15] [7]. With an estimated prevalence of 1:7,500–1:20,000 live births, PCD remains challenging to diagnose due to its nonspecific clinical presentation and the requirement for complex, expensive diagnostic tests available only at specialized centers [7]. These tests include nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing, none of which alone serves as a standalone gold standard [7]. The PICADAR tool was developed to address this diagnostic challenge by providing a evidence-based method to triage patients for specialized testing using readily available clinical information [15].

The PICADAR Scorecard: Parameters and Scoring System

The PICADAR scorecard was derived from a prospective study of 641 consecutive patients referred for PCD testing, of whom 75 (12%) received a positive diagnosis [15]. Through logistic regression analysis of 27 potential clinical variables, seven predictive parameters were identified that can be readily obtained through patient history [15] [16]. The scoring system applies specifically to patients with persistent wet cough and assigns points as follows:

Table 1: The Seven Predictive Parameters of the PICADAR Scorecard

| Predictive Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation (≥37 weeks) | 2 points |

| Neonatal chest symptoms (within first month of life) | 2 points |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 point |

| Chronic rhinitis (>3 months) | 1 point |

| Chronic ear symptoms | 1 point |

| Situs inversus | 2 points |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 points |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for calculating a patient's PICADAR score and interpreting the result:

Performance Analysis: Validation and Limitations

Since its original development, multiple studies have evaluated PICADAR's performance in different populations, revealing both its utility and significant limitations.

Table 2: PICADAR Performance Across Validation Studies

| Study Population | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original derivation (n=641) [15] | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.91 | Cut-off score of 5 points optimized performance |

| External validation (n=187) [15] | N/A | N/A | 0.87 | Good discriminative ability in independent cohort |

| Genetically confirmed PCD (n=269) [5] | 0.75 | N/A | N/A | 7% with no daily wet cough automatically excluded |

| PCD with laterality defects [5] | 0.95 | N/A | N/A | High sensitivity in this subgroup |

| PCD with situs solitus (normal arrangement) [5] [6] | 0.61 | N/A | N/A | Significantly reduced sensitivity |

| PCD with hallmark ultrastructural defects [5] [6] | 0.83 | N/A | N/A | Moderate sensitivity |

| PCD without hallmark ultrastructural defects [5] [6] | 0.59 | N/A | N/A | Substantially limited sensitivity |

| Japanese cohort (n=67) [8] | N/A | N/A | N/A | Mean score: 7.3; only 25% with situs inversus |

A critical 2025 study by Schramm et al. evaluating 269 genetically confirmed PCD patients revealed important limitations [5] [6]. The study found that 18 individuals (7%) reported no daily wet cough, automatically ruling out PCD according to PICADAR's initial screening question [5]. The overall sensitivity was 75%, significantly lower than the original derivation study [5] [6]. Subgroup analysis demonstrated dramatically different performance: sensitivity reached 95% in patients with laterality defects but dropped to 61% in those with situs solitus (normal organ arrangement) [5] [6]. Similarly, sensitivity was substantially higher in patients with hallmark ultrastructural defects (83%) compared to those without (59%) [5] [6]. These findings highlight significant limitations in detecting PCD patients without classic laterality defects or ultrastructural abnormalities.

Ethnic variations further complicate PICADAR's performance. A Japanese study of 67 PCD patients found only 25% had situs inversus, substantially lower than the approximately 50% typically reported in other populations [8]. This difference was attributed to variations in prevalent causative genes across ethnic groups [8]. With a mean PICADAR score of 7.3 points, the tool remained useful in this population, but the dramatically lower rate of situs inversus—a high-scoring parameter—could impact its performance in non-European populations [8].

Experimental Methodologies

Original Derivation Study Protocol

The original PICADAR derivation study employed a rigorous methodological approach [15]. The research analyzed data from 641 consecutive patients with definitive diagnostic outcomes from the University Hospital Southampton PCD diagnostic center between 2007-2013 [15]. A standardized proforma was used to collect patient data through clinical interviews prior to diagnostic testing [15]. Diagnostic criteria required a typical clinical history with at least two abnormal specialized tests: "hallmark" transmission electron microscopy (TEM) findings, "hallmark" ciliary beat pattern (CBP) on high-speed video microscopy analysis, or nasal nitric oxide (nNO) ≤30 nL·min⁻¹ [15]. Statistical analysis involved comparing characteristics of positive and negative referrals using parametric (t-test) and nonparametric (Mann-Whitney) tests, chi-squared tests, or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate [15]. Logistic regression analysis identified significant predictors, with model performance assessed through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and area under the curve (AUC) calculations [15]. The model was simplified into a practical scoring tool by rounding regression coefficients to the nearest integer [15].

External Validation Methodology

External validation followed a similar protocol using a sample of 187 patients (93 PCD-positive, 94 PCD-negative) referred to the Royal Brompton Hospital between 1983-2013 [15]. An equal number of positive and negative referrals were randomly selected from the overall population [15]. Using a similar protocol to the derivation group, clinical history proformas were completed before diagnostic testing [15]. The discriminative ability of the PICADAR scores in this validation population was assessed using ROC curve analysis [15]. This external validation cohort was younger and more likely to be non-white and from consanguineous backgrounds compared to the derivation group, reflecting different population characteristics and testing the tool's generalizability [15].

Genetic Validation Study Design

The 2025 validation study by Schramm et al. employed a distinct methodology focused on genetically confirmed PCD cases [5] [6]. The research evaluated 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD, using the initial PICADAR question about daily wet cough as a gatekeeper [5]. The study calculated test sensitivity based on the proportion of individuals scoring ≥5 points as recommended in the original tool [5] [6]. Subgroup analyses specifically examined the impact of laterality defects and predicted hallmark ultrastructural defects on test performance [5] [6]. This genetic confirmation approach provided an independent assessment of PICADAR's performance against a molecular gold standard, revealing important limitations not apparent in the original validation against composite diagnostic standards [5] [6].

Essential Research Toolkit for PCD Diagnostic Prediction Research

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for PCD Diagnostic Prediction Research

| Research Tool | Application in PCD Research | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-speed video microscopy (HSVA) | Ciliary beat pattern analysis | Visualizes and quantifies ciliary motion abnormalities [7] |

| Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) | Ciliary ultrastructural assessment | Identifies defects in dynein arms, microtubule organization [7] |

| Nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement | Screening and diagnostic testing | Low nNO levels support PCD diagnosis [15] [7] |

| Genetic testing panels | Mutation identification in >50 PCD-associated genes | Confirms diagnosis, establishes genotype-phenotype correlations [5] [7] |

| Clinical data collection proformas | Standardized symptom documentation | Ensures consistent data collection for predictive tool application [15] |

| Immunofluorescence microscopy | Protein localization in cilia | Detects absence or mislocalization of ciliary proteins [7] |

The following diagram illustrates how these research tools integrate into a comprehensive PCD diagnostic workflow:

The PICADAR scorecard represents an important advancement in systematizing the clinical assessment of patients with suspected PCD, providing a structured approach to prioritizing specialized testing. Its seven predictive parameters effectively identify classic PCD presentations, particularly in patients with laterality defects and characteristic ultrastructural abnormalities [15] [5]. However, evidence from recent studies indicates significant limitations in sensitivity, especially for patients without situs inversus (61%) or those lacking hallmark ultrastructural defects (59%) [5] [6]. The tool's dependency on daily wet cough as an initial screening question automatically excludes approximately 7% of genetically confirmed PCD cases [5]. Furthermore, ethnic variations in clinical presentation, such as the lower prevalence of situs inversus in Japanese populations (25%), may impact its performance across different genetic backgrounds [8]. These limitations underscore the need for complementary predictive tools and careful clinical judgment when implementing PICADAR in research protocols or clinical practice. Future development of PCD predictive tools should focus on capturing the full phenotypic spectrum of this genetically heterogeneous disorder, particularly patients with normal body laterality and ultrastructure.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by abnormal ciliary function, leading to impaired mucociliary clearance of the airways. The diagnosis of PCD is challenging due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms and the requirement for highly specialized, expensive diagnostic testing available only at specialized centers [15]. To address this challenge, the PrImary CiliARy DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) was developed as a clinical predictive tool to identify patients who should be referred for definitive PCD testing [15] [16]. This diagnostic predictive tool aggregates easily obtainable clinical features into a single numerical score, with a critical cut-off point that stratifies patients based on their probability of having PCD. The selection of an appropriate score threshold balances the competing needs of identifying true positive cases while avoiding unnecessary specialist referrals. This guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the score of 5 within the PICADAR framework, examining its original validation, comparative performance against other tools, and important limitations that researchers and clinicians must consider when implementing this tool in practice.

The PICADAR Tool: Composition and Calculation

The PICADAR tool is designed for patients with persistent wet cough and incorporates seven key clinical parameters obtained from patient history [15]. Each parameter is assigned a specific point value based on regression coefficients from the original derivation study. When summed, these points generate a total score that corresponds to the probability of a PCD diagnosis.

PICADAR Scoring Parameters

| Predictive Parameter | Points Assigned |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation | 2 |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | 2 |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 |

| Chronic rhinitis | 1 |

| Ear symptoms | 1 |

| Situs inversus | 2 |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 |

Table 1: The seven predictive parameters of the PICADAR tool and their assigned point values [15].

The PICADAR evaluation process follows a specific clinical workflow. It is crucial to note that the tool is only applied to patients who present with a persistent wet cough, which serves as an initial screening question [6]. Patients without this symptom are not considered for further PICADAR evaluation, representing an inherent limitation in its design.

Figure 1: The clinical workflow for applying the PICADAR tool, beginning with the assessment for persistent wet cough [15] [6].

Performance Data for the PICADAR Score of 5

Original Validation Studies

In the original 2016 derivation and validation study by Behan et al., which analyzed 641 consecutive referrals to a PCD diagnostic center, a PICADAR score of 5 emerged as the optimal cut-off value [15]. At this threshold, the tool demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.90 and a specificity of 0.75 for predicting a positive PCD diagnosis, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.91 upon internal validation [15]. External validation at a second diagnostic center showed maintained performance with an AUC of 0.87 [15]. This balance between sensitivity and specificity meant that the tool correctly identified 90% of true PCD cases while correctly excluding 75% of non-PCD cases.

Comparative Performance Against Other Predictive Tools

Subsequent studies have compared PICADAR's performance against other predictive tools, notably the Clinical Index (CI) and the North American Criteria Defined Clinical Features (NA-CDCF). A 2021 study by Tabs et al. evaluated all three tools in 1,401 patients with suspected PCD [17].

| Predictive Tool | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR (Score ≥5) | 0.91 (original) [15] | High sensitivity in classic phenotype | Not applicable without chronic wet cough [17] |

| Clinical Index (CI) | Larger than NA-CDCF (p=0.005) [17] | Does not require assessment of laterality [17] | Less validated in diverse populations |

| NA-CDCF | No significant difference from PICADAR [17] | Simple, four-item criteria | May miss atypical presentations |

| nNO Measurement | N/A | Further improves all predictive tools when combined [17] | Requires expensive equipment [15] |

Table 2: Comparative performance of PCD predictive tools based on validation studies.

The study found that while all three scores were significantly higher in the PCD group (p < 0.001), the CI demonstrated potential advantages in certain clinical scenarios [17]. Importantly, the researchers noted that PICADAR could not be assessed in 6.1% of patients because they did not have chronic wet cough, a mandatory prerequisite for using the tool [17].

Critical Limitations and Population-Specific Performance

Sensitivity Concerns in Genetically Confirmed PCD

A critical 2025 pre-print study by Omran et al. evaluated PICADAR's performance in 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD, revealing significant limitations in test sensitivity [6] [18]. The study reported an overall sensitivity of only 75% at the recommended cut-off score of ≥5, meaning the tool would miss approximately one in four confirmed PCD cases [6]. Even more concerning were the subgroup analyses, which demonstrated markedly variable performance:

- 95% sensitivity in patients with laterality defects (median score: 10) [6]

- 61% sensitivity in patients with situs solitus (normal organ arrangement; median score: 6) [6]

- 83% sensitivity in patients with hallmark ultrastructural defects [6]

- 59% sensitivity in patients without hallmark ultrastructural defects [6]

These findings indicate that PICADAR performs excellently for classic PCD presentations with laterality defects but misses nearly 40% of cases with normal organ arrangement or normal ciliary ultrastructure.

Geographical and Genetic Variability

The performance of PICADAR also appears to vary across different ethnic and geographical populations. A study of Japanese PCD patients found that only 25% exhibited situs inversus [8], compared to the approximately 50% typically reported in other populations [15]. This difference reflects variations in prevalent genetic mutations across populations and directly impacts PICADAR scores, as situs inversus contributes 2 points toward the total score. Consequently, PICADAR may systematically underscore patients from populations with lower prevalence of laterality defects.

Experimental Protocols for PICADAR Validation

Original Derivation Study Methodology

The original PICADAR derivation and validation followed a rigorous methodological protocol [15]:

- Study Population: 641 consecutive patients with definitive diagnostic outcomes from the University Hospital Southampton PCD diagnostic center (2007-2013).

- Data Collection: A proforma was used to collect patient data through clinical interview prior to diagnostic testing, including gestational age, neonatal symptoms, admittance to special care units, respiratory support needs, chronic cough, rhinitis, sinusitis, ear problems, situs abnormalities, and congenital cardiac defects.

- Statistical Analysis: Logistic regression analysis identified significant predictors from 27 potential variables. The model's discrimination was assessed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and Area Under the Curve (AUC) calculations. A Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test assessed calibration.

- Validation: External validation was performed using data from 187 patients (93 PCD-positive, 94 PCD-negative) from Royal Brompton Hospital.

Comparative Validation Protocol

The 2021 comparative study by Tabs et al. employed the following methodology [17]:

- Population: 1,401 patients with suspected PCD referred for high-speed video microscopy testing.

- Assessment: CI, PICADAR, and NA-CDCF scores were calculated retrospectively from medical records.

- Diagnostic Confirmation: PCD diagnosis followed ERS guidelines, incorporating nNO measurement, HSVM, transmission electron microscopy, and genetic testing.

- Statistical Comparison: Predictive characteristics were analyzed using ROC curves and AUC comparisons between tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in PCD Research |

|---|---|

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVM) | Analyzes ciliary beat frequency and pattern from nasal brushings [19] [17] |

| Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) | Visualizes ultrastructural defects in ciliary architecture [19] |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Measures nNO levels (low nNO is a PCD screening marker) [15] [17] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Identifies mutations in >50 known PCD genes [19] [17] |

| Immunofluorescence Assays | Detects specific protein localization in ciliary apparatus [19] |

| Cell Culture Systems | Allows ciliary re-differentiation for repeated functional testing [15] |

Table 3: Key reagents and equipment essential for PCD diagnostic research and predictive tool validation.

The PICADAR score of 5 represents a carefully validated cut-off that demonstrates good overall accuracy in the initial derivation studies. However, emerging evidence reveals significant limitations, particularly its substantially reduced sensitivity (61%) in PCD patients with normal organ arrangement [6] and its inapplicability to patients without persistent wet cough [17]. These limitations necessitate cautious implementation in clinical practice and research settings. For drug development professionals and researchers, these findings underscore that PICADAR should not be used as a standalone eligibility criterion for clinical trials or as the sole basis for estimating PCD prevalence in population studies. The tool works excellently for classic PCD presentations but systematically underestimates the likelihood of disease in patients with normal situs or non-classic genetic variants. Future research should focus on developing more inclusive predictive tools that incorporate genetic and ultrastructural data to better capture the full phenotypic spectrum of PCD, particularly as targeted therapies emerge that may benefit patients across all PCD subtypes.

Implementing PICADAR: Protocol, Calculation, and Clinical Workflow

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by impaired ciliary function, leading to chronic respiratory symptoms. Diagnosis is challenging due to nonspecific symptoms and the absence of a single gold-standard test. The PICADAR tool (Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule) was developed as a clinical predictive tool to identify patients who should be referred for specialized PCD diagnostic testing [4]. This guide provides comprehensive instructions for administering the PICADAR questionnaire within research settings, alongside comparative performance data against other predictive tools.

Understanding the PICADAR Tool

Clinical Rationale and Development

PICADAR was developed to address the critical need for efficient patient triage in PCD diagnosis. Specialized diagnostic tests for PCD—including nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, high-speed video microscopy (HSVM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and genetic testing—are technically complex, expensive, and limited to specialized centers [4] [7]. PICADAR utilizes easily obtainable clinical data to estimate the probability of PCD, enabling researchers and clinicians to identify high-risk patients efficiently.

The tool was derived from a study of 641 consecutive patients referred for PCD testing, with external validation in an independent cohort [4]. It applies specifically to patients with persistent wet cough and incorporates seven clinically significant parameters.

PICADAR Parameters and Scoring

The PICADAR questionnaire assesses seven predictive parameters, each assigned a specific point value [4] [20]. The total score determines the probability of PCD and corresponding referral recommendations.

Table 1: PICADAR Scoring Parameters

| Parameter | Description | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Situs inversus | Complete reversal of thoracic and abdominal organs | 2 |

| Congenital cardiac defect | Structural heart abnormality present at birth | 2 |

| Full-term gestation | Birth at ≥37 weeks gestation | 1 |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | Respiratory distress or requiring respiratory support in term newborn | 1 |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | Required NICU care after birth | 1 |

| Chronic rhinitis | Persistent nasal congestion/discharge beginning in infancy and lasting >3 months | 1 |

| Ear symptoms | Chronic otitis media or hearing impairment | 1 |

Scoring Interpretation

- Score ≥5 points: High probability of PCD (Sensitivity: 0.90, Specificity: 0.75) - Strongly recommend referral for specialized PCD testing [4]

- Score <5 points: Lower probability of PCD - Consider alternative diagnoses or continue monitoring

PICADAR Administration Protocol

Pre-Assessment Preparation

- Target Population: Patients with persistent wet cough of unknown etiology [4]

- Data Sources: Clinical interview, medical record review, or direct patient assessment

- Qualifications: Administered by healthcare professionals or trained research staff

- Timing: Typically administered during initial evaluation for chronic respiratory symptoms

Step-by-Step Administration Procedure

Figure 1: PICADAR Questionnaire Administration Workflow

- Confirm Gestational Age: Verify the patient was born at full-term (≥37 weeks gestation) [4]

- Assess Neonatal Respiratory History: Document whether the newborn experienced respiratory distress or required respiratory support at term gestation

- Establish NICU Admission: Confirm if the patient was admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit after birth

- Evaluate Chronic Rhinitis: Determine presence of persistent, year-round nasal congestion or discharge beginning in infancy and lasting >3 months

- Screen for Otologic Symptoms: Identify history of recurrent otitis media or hearing impairment

- Document Situs Status: Confirm presence of situs inversus through physical examination or review of prior imaging studies

- Identify Cardiac Abnormalities: Document any congenital heart defects through medical history or echocardiography reports

Data Collection Methodology

The original validation study utilized a structured proforma completed by clinicians through direct patient interview prior to diagnostic testing [4]. Data collection should be systematic and standardized:

- Clinical Interview: Conduct face-to-face structured interviews for comprehensive data collection [21]

- Medical Record Review: Supplement interview data with thorough chart review for objective parameters (e.g., gestational age, NICU admission)

- Standardized Coding: Record all parameters as binary outcomes (yes=1, no=0) [4]

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Validation Data

PICADAR has been extensively validated against other predictive tools in multiple clinical studies. A 2021 study compared PICADAR with Clinical Index (CI) and North American Criteria Defined Clinical Features (NA-CDCF) in 1,401 patients with suspected PCD [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of PCD Predictive Tools

| Tool | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR | 0.87 (external validation) [4] | 0.90 (at cut-off ≥5) [4] | 0.75 (at cut-off ≥5) [4] | Validated externally; good accuracy | Requires chronic wet cough; cannot assess in 6.1% without this symptom [17] |

| Clinical Index (CI) | Larger than NA-CDCF (p=0.005) [17] | Not specified | Not specified | No need to assess laterality or cardiac defects; feasible for all patients [17] | Less widely validated than PICADAR |

| NA-CDCF | No significant difference from PICADAR (p=0.093) [17] | Not specified | Not specified | Simple criteria; easy to remember | Limited predictive parameters |

| nNO Combined with PICADAR | Not specified | Improved when combined with PICADAR [17] | Improved when combined with PICADAR [17] | Enhanced predictive power | Requires specialized equipment |

Key Comparative Findings

- Diagnostic Accuracy: PICADAR demonstrated excellent discriminative ability with Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.91 in derivation and 0.87 in external validation [4]

- Clinical Utility: PICADAR significantly outperformed NA-CDCF in direct comparison (p=0.005), while showing equivalent performance to CI in some studies [17]

- Complementary Testing: Combining PICADAR with nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement further improved predictive power for all tools [17]

Research Implementation Framework

Integration with Diagnostic Pathways

For research applications, PICADAR should be integrated within a comprehensive diagnostic algorithm:

Figure 2: PICADAR in PCD Diagnostic Pathway

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Diagnostic Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Data Collection Form | Standardized PICADAR parameter assessment | Customized proforma based on original validation study [4] |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide Analyzer | Complementary screening measurement | Niox Mino/Vero (Aerocrine AB) or CLD 88sp (ECO MEDICS) [17] [22] |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy | Ciliary beat pattern analysis | Keyence Motion Analyzer, Basler acA1300-200um camera [17] [22] |

| TEM Equipment | Ultrastructural ciliary analysis | Standard electron microscopy protocols [17] |

| Genetic Testing Platform | PCD gene mutation identification | Next-generation sequencing panels (e.g., 22-39 PCD genes) [17] [22] |

| Immunofluorescence Antibodies | Ciliary protein localization | Anti-DNAH5, Anti-GAS8 antibodies [22] |

Methodological Considerations for Research

- Population Selection: PICADAR validation specifically included patients with chronic wet cough; application to populations without this symptom is limited [17]

- Data Quality Control: Implement standardized training for interviewers to minimize assessment variability [4]

- Statistical Analysis: Utilize ROC curve analysis to assess tool performance; calculate sensitivity, specificity, and AUC values [17] [4]

- Multicenter Validation: Consider study design that enables external validation across different patient populations and clinical settings

The PICADAR questionnaire represents a validated, practical tool for identifying high-risk PCD patients in research settings. Its standardized administration and scoring system enables efficient triage for specialized diagnostic testing. While PICADAR demonstrates strong predictive performance, researchers should consider its limitations regarding patient selection and complement it with objective measures like nNO for enhanced accuracy. The continued validation of PICADAR across diverse populations will further establish its utility in advancing PCD research and clinical diagnostics.

In the diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD), a rare genetic disorder affecting respiratory cilia function, the journey from initial patient assessment to definitive diagnosis presents significant challenges. Specialized diagnostic tests require expensive equipment and expert interpretation, creating barriers to accessibility [4]. In this context, the PICADAR (PrImary CiliARy DyskinesiA Rule) prediction tool emerges as a clinically valuable screening instrument that enables efficient patient prioritization for confirmatory testing through systematic data collection and score calculation [4].

This guide objectively evaluates PICADAR's performance against alternative diagnostic approaches, examining its sensitivity, specificity, and practical implementation within the research and clinical workflow for PCD diagnosis.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of PCD Diagnostic Methods

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of PICADAR compared to other established diagnostic methods for PCD, based on validation studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of PCD Diagnostic Tools

| Diagnostic Method | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PICADAR Score | 0.90 (at cut-off ≥5) [4] | 0.75 (at cut-off ≥5) [4] | Relies on accurate patient history; performance may vary in non-validation populations. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) | Efficient for screening [4] | Efficient for screening [4] | Requires expensive equipment and trained technicians [4]. |

| Genetic Testing | Limited sensitivity as a standalone test [7] | High, but complex genetic etiology [7] | >50 associated genes; no single test has high sensitivity and specificity [7]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) | Used in composite diagnosis [4] | Used in composite diagnosis [4] | Requires specialist center and experienced scientists [4]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | Identifies ~70% of ultrastructural defects [4] | Used in composite diagnosis [4] | Invasive; requires specialized infrastructure and expertise [4]. |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

PICADAR Derivation and Validation Methodology

The PICADAR prediction tool was developed and validated through a multi-stage process:

- Study Population: The derivative group consisted of 641 consecutive patients with a definitive diagnostic outcome referred to the University Hospital Southampton (UHS) PCD diagnostic center between 2007 and 2013. A proforma was used to collect patient data through clinical interview prior to diagnostic testing [4].

- Validation Cohort: External validation was performed using a sample of 187 patients (93 PCD-positive, 94 PCD-negative) referred to the Royal Brompton Hospital (RBH). An equal number of positive and negative referrals were randomly selected from patients referred between 1983 and 2013 [4].

- Diagnostic Standard: A positive PCD diagnosis was typically based on a classic clinical history with at least two abnormal diagnostic tests, including hallmark TEM findings, hallmark ciliary beat pattern (CBP), or nasal nitric oxide (nNO) ≤30 nL·min⁻¹. In some cases, patients with a strong history were diagnosed based on a single definitive test [4].

- Statistical Analysis: Logistic regression analysis identified significant predictors from 27 potential variables. Model performance was assessed using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, calculating the Area Under the Curve (AUC). The model was simplified into a practical scoring tool (PICADAR) where the score for each predictor corresponds to their regression coefficient rounded to the nearest integer [4].

PICADAR Score Calculation and Interpretation

The PICADAR tool is applied to patients with persistent wet cough and calculates a score based on seven clinical parameters obtained from patient history [4]. The following workflow illustrates the diagnostic pathway incorporating PICADAR:

Diagram 1: PICADAR Clinical Decision Workflow

Performance Metrics and Validation Outcomes

The PICADAR tool demonstrated strong predictive performance in both derivation and validation populations:

- Derivation Group (n=641): The AUC was 0.91, indicating excellent discriminatory power. At the recommended cut-off score of 5 points, sensitivity was 0.90 and specificity was 0.75 [4].

- Validation Group (n=187): The tool maintained strong performance with an AUC of 0.87, confirming its validity in an external population [4].

- Diagnostic Yield: In the derivation cohort, 75 patients (12%) were diagnosed with PCD, while 566 (88%) had a negative diagnosis [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting comprehensive PCD diagnostic research, including the evaluation of clinical prediction tools like PICADAR.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PCD Diagnostic Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application in PCD Research |

|---|---|

| Clinical History Proforma | Standardized data collection tool for PICADAR parameters and other clinical features prior to diagnostic testing [4]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Measures nNO levels for screening; values ≤30 nL·min⁻¹ support PCD diagnosis [4]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy System | Analyzes ciliary beat pattern and frequency from nasal epithelial brush biopsies [4] [7]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Evaluates ultrastructural defects in cilia (e.g., dynein arm defects, microtubule disorganization) [4] [7]. |

| Genetic Testing Panels | Identifies mutations in over 50 known PCD-associated genes (e.g., DNAH5, DNAI1, CCDC39, CCDC40) [7]. |

| Cell Culture Materials for ALI Culture | Re-differentiates ciliated epithelium for confirmatory ciliary functional analysis when initial results are inconclusive [4]. |

PICADAR represents a validated, cost-effective first-line tool for identifying patients at high probability of PCD who warrant further specialized testing. Its standardized approach to data collection from patient history and simple scoring calculation facilitates early diagnosis, particularly in settings with limited immediate access to complex diagnostic modalities. While PICADAR cannot replace definitive diagnostic tests, its integration into a structured diagnostic pathway enables more efficient resource allocation and accelerates the time to diagnosis for this rare genetic disorder.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by abnormal ciliary function, leading to impaired mucociliary clearance with an estimated prevalence ranging from 1:10,000 to 1:40,000 [15] [9]. The diagnostic pathway for PCD presents significant challenges due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms, which overlap with more common respiratory conditions like asthma, recurrent bronchitis, and cystic fibrosis [9]. This diagnostic complexity is compounded by the absence of a single "gold standard" test and the highly specialized nature of definitive PCD diagnostic testing, which requires expensive equipment and experienced scientists [15] [23]. Consequently, many patients experience diagnostic delays, with some reports indicating over 40 visits to medical professionals before receiving appropriate referral for PCD testing [9].

Within this challenging diagnostic landscape, clinical prediction tools have emerged as valuable assets for identifying patients who require specialist referral. The European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines acknowledge the utility of such tools, specifically recommending the PCD Rule (PICADAR) for assessing referral likelihood [6] [23]. This review critically examines the integration of PICADAR into referral pathways, evaluating its performance characteristics against alternative approaches, and exploring its role in facilitating appropriate patient flow from general practice to specialist PCD centers.

PICADAR: Structure, Application, and Performance

Tool Development and Predictive Parameters

PICADAR was developed through a prospective study of 641 consecutive patients referred for PCD testing to create a practical diagnostic predictive tool using readily available clinical information [15]. The tool applies specifically to patients with persistent wet cough and incorporates seven predictive parameters easily obtained through patient history and clinical interview [15].

Table 1: PICADAR Predictive Parameters and Scoring System

| Predictive Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation | 2 points |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | 2 points |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 points |

| Chronic rhinitis | 1 point |

| Ear symptoms | 1 point |

| Situs inversus | 2 points |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 4 points |

The PICADAR score is calculated by summing the points for each present parameter, with total scores ranging from 0 to 14 [15]. The developers established a cut-off score of 5 points, at which the tool demonstrates optimal performance characteristics for identifying patients requiring specialist testing [15].

Performance Characteristics and Validation

The original validation study for PICADAR reported strong diagnostic performance metrics. At the recommended cut-off score of 5 points, the tool demonstrated a sensitivity of 0.90 and specificity of 0.75 [15]. The area under the curve (AUC) for the internally validated tool was 0.91, indicating excellent discriminative ability, while external validation in a second diagnostic center showed an AUC of 0.87, confirming good validity across different populations [15].

However, a 2025 study evaluating PICADAR in 269 genetically confirmed PCD patients revealed important limitations in sensitivity [6]. The overall sensitivity was 75%, significantly lower than originally reported, with particularly reduced sensitivity in specific patient subgroups: 61% in patients without laterality defects (situs solitus) and 59% in those without hallmark ultrastructural defects [6]. Notably, 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients were ruled out by PICADAR's initial requirement for daily wet cough [6].

Table 2: PICADAR Performance Across Studies

| Study | Population | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Limitations Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behan et al. (2016) [15] | 641 referrals (75 PCD+) | 0.90 | 0.75 | 0.91 (internal) 0.87 (external) | - |

| Omran et al. (2025) [6] | 269 genetically confirmed PCD | 0.75 (overall) 0.61 (situs solitus) 0.59 (no hallmark defects) | - | - | Low sensitivity in specific subgroups; excludes patients without daily wet cough |

Comparative Analysis of PCD Diagnostic Prediction Tools

North American CDCF Criteria