Prime Editing: A Guide to Precise Genetic Repair Without Double-Strand Breaks

This article provides a comprehensive overview of prime editing, a revolutionary genome-editing technology that enables precise correction of genetic mutations without introducing double-strand DNA breaks.

Prime Editing: A Guide to Precise Genetic Repair Without Double-Strand Breaks

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of prime editing, a revolutionary genome-editing technology that enables precise correction of genetic mutations without introducing double-strand DNA breaks. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational mechanisms of prime editing, its methodological applications across diverse genetic disorders, current challenges with optimization strategies, and a comparative analysis with other editing platforms. The content synthesizes the latest research and clinical advancements, offering insights into the therapeutic potential and future trajectory of this precise genetic tool.

The Foundation of Prime Editing: From Search-and-Replace to Clinical Potential

The landscape of genome editing has been fundamentally reshaped by the advent of CRISPR-Cas9, which offers unprecedented ability to manipulate DNA sequences. However, its therapeutic application is constrained by a fundamental limitation: the reliance on creating double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA. These breaks activate error-prone repair pathways, leading to unpredictable insertions, deletions, and chromosomal rearrangements that pose significant safety risks for clinical applications [1]. Furthermore, the requirement for donor DNA templates in homology-directed repair complicates the editing process and reduces efficiency.

Prime editing represents a paradigm shift in precision genome editing by enabling precise genetic modifications without inducing DSBs or requiring donor DNA templates [1]. This "search-and-replace" technology significantly expands the scope of editable sequences while minimizing unwanted byproducts, addressing critical limitations of both nuclease-dependent CRISPR systems and earlier base editing platforms. This Application Note details the operational principles, optimized protocols, and key applications of prime editing, providing researchers with the tools to implement this transformative technology for therapeutic development and functional genomics.

Core Architecture and Mechanism

The prime editing system consists of two principal components: (1) a prime editor protein and (2) a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The editor is a fusion of a Cas9 nickase (H840A) that cuts only a single DNA strand, and an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) from Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (MMLV) [1] [2]. The pegRNA serves a dual function, both directing the complex to the target genomic locus and encoding the desired edit [2].

The editing mechanism occurs through a coordinated multi-step process:

- Target Recognition and Strand Nicking: The PE:pegRNA complex binds to the target DNA sequence, where the Cas9 nickase introduces a single-strand cut in the non-target DNA strand [1] [2].

- Reverse Transcription and Flap Formation: The exposed 3' end of the nicked DNA hybridizes with the primer binding site (PBS) on the pegRNA, serving as a primer for reverse transcription. The RT synthesizes a new DNA flap containing the desired edit using the reverse transcription template (RTT) region of the pegRNA [1] [2].

- Flap Resolution and Strand Integration: Cellular repair machinery resolves the branched DNA structure, favoring the incorporation of the edited 3' flap over the original 5' flap, resulting in the installation of the new genetic information into the genome [1].

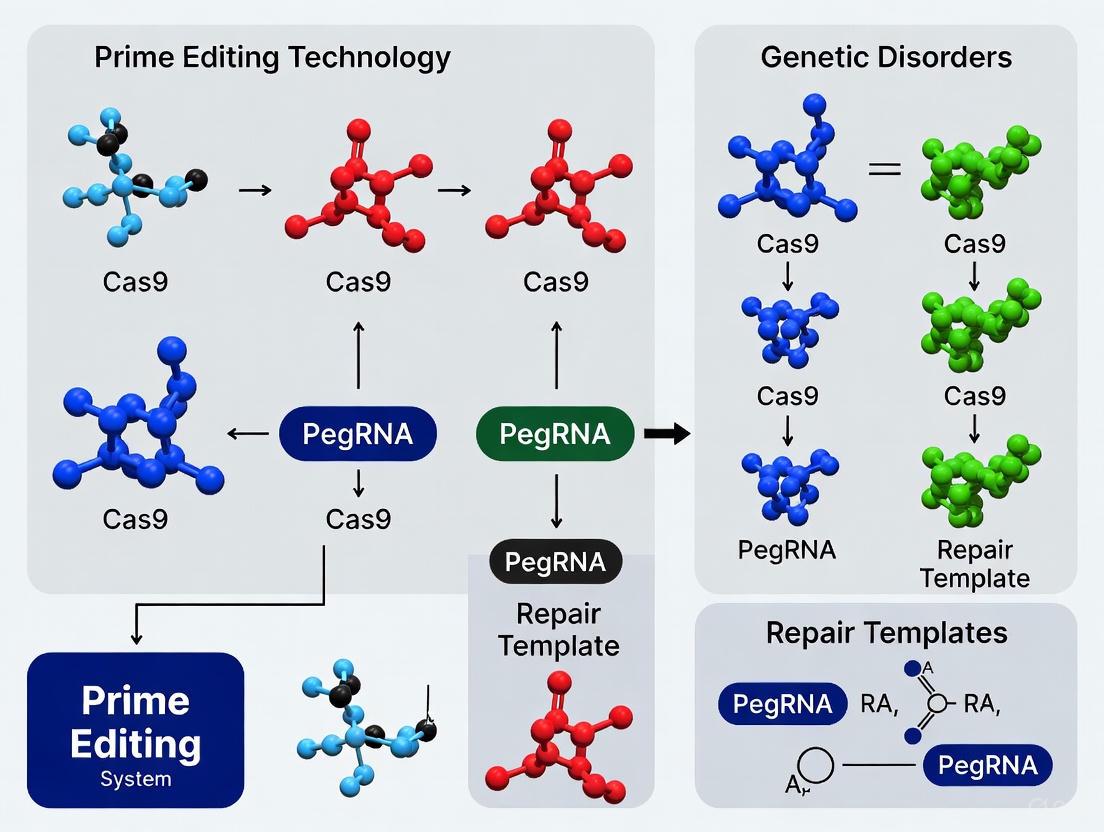

The following diagram illustrates this sophisticated mechanism:

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

Since its initial development, prime editing has undergone significant optimization through successive generations of improved editors:

Table 1: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

| Editor Version | Key Features | Improvements Over Previous Generation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Initial proof-of-concept: nCas9(H840A)-MMLV-RT fusion [1] | Foundation of prime editing technology | Demonstration of precise edits without DSBs [1] |

| PE2 | Engineered RT with enhanced thermostability and processivity [1] | 2-5x higher editing efficiency than PE1 [1] | Broad research applications requiring moderate efficiency [1] |

| PE3 | PE2 + additional sgRNA to nick non-edited strand [1] | Encourages cellular repair to use edited strand as template; increases editing efficiency [1] | Applications requiring highest possible editing rates [1] |

| PEmax | Codon-optimized editor with nuclear localization signals, R221K, N394K mutations [3] | Improved nuclear localization and expression; enhanced editing across diverse targets [3] | High-efficiency editing in therapeutic contexts [3] |

| vPE | Modified Cas9 with reduced error rate; stabilized RNA template [4] | Error rate reduced to 1/60th of original (from ~1/7 to ~1/543 edits) [4] | Therapeutic applications where safety is paramount [4] |

Quantitative Performance and Applications

Benchmarking Editing Efficiency

Recent advances in prime editing platform optimization have demonstrated remarkable improvements in editing efficiency. A benchmarked, high-efficiency platform developed for multiplexed dropout screening achieved unprecedented performance when combining stable expression of optimized components with DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency [3].

Table 2: High-Efficiency Prime Editing Performance Metrics

| Experimental Condition | Editing Target | Precise Editing Efficiency (Day 7) | Precise Editing Efficiency (Day 28) | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEmax + epegRNA | HEK3 +1 T>A | 2.3% | 7.8% | MMR-proficient background [3] |

| PEmax + epegRNA | DNMT1 +6 G>C | 55.9% | ~78% | MMR-proficient background [3] |

| PEmaxKO + epegRNA | HEK3 +1 T>A | 68.9% | 94.9% | MLH1 knockout (MMR-deficient) [3] |

| PEmaxKO + epegRNA | DNMT1 +6 G>C | 81.1% | ~95% | MLH1 knockout (MMR-deficient) [3] |

| Self-targeting library | 1,453 edits | - | >75% (75.5% of edits) | MMR-deficient cells; 2,000 epegRNA-target pairs [3] |

The data demonstrate that stable expression of editing components in MMR-deficient backgrounds enables continuous accumulation of precise edits over time, with many targets reaching near-saturation editing (>95%) after extended duration [3]. This represents a substantial improvement over transient delivery approaches, which typically achieve lower efficiencies.

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Potential

Prime editing's versatility enables diverse therapeutic applications, with several approaches demonstrating promise in preclinical models:

Disease-Agnostic Treatment Platforms The PERT (Prime Editing-mediated Readthrough of Premature Termination Codons) platform addresses nonsense mutations that account for approximately 30% of rare genetic diseases [5]. Rather than correcting individual mutations, PERT installs a engineered suppressor tRNA that enables readthrough of premature stop codons, potentially treating multiple diseases with a single editor [5]. In proof-of-concept studies:

- Restored protein function in cell models of Batten disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and Niemann-Pick disease type C1 (20-70% of normal enzyme activity) [5]

- Alleviated disease symptoms in a mouse model of Hurler syndrome with ~6% enzyme restoration [5]

- No detected off-target edits or disruption of normal protein synthesis [5]

High-Throughput Functional Genomics The precision and programmability of prime editing enables multiplexed functional screening. A platform utilizing 240,000 engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) targeting ~17,000 codons successfully identified negative selection phenotypes for 7,996 nonsense mutations in 1,149 essential genes, demonstrating the technology's scalability for functional variant characterization [3].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Efficiency Prime Editing in Mammalian Cells

This protocol describes a robust method for achieving high-efficiency prime editing in mammalian cell lines through stable expression of editing components and MMR manipulation, adapted from benchmarked approaches [3].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for High-Efficiency Prime Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Product/Component | Function in Protocol | Notes and Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Expression | PEmax plasmid [3] | Optimized editor fusion protein | Contains nuclear localization signals, codon optimization [3] |

| Guide RNA System | epegRNA with tevopreQ1 motif [3] | Target specification and edit template; enhanced stability | 3' structural motif protects against degradation [3] |

| Delivery Vector | Lentiviral transfer plasmid (e.g., pBYR2eFa-U6-sgRNA) [3] | Stable genomic integration of editing components | Enables long-term expression and edit accumulation [3] |

| Cell Line | K562 PEmaxKO (MLH1 knockout) [3] | MMR-deficient background | Critical for high efficiency editing; MLH1 disruption prevents edit rejection [3] |

| Selection Agent | Appropriate antibiotic (e.g., puromycin) | Selection of successfully transduced cells | Concentration determined by kill curve analysis |

| Analysis Reagents | Next-generation sequencing library preparation kit | Quantification of editing efficiency and purity | AmpSeq considered gold standard [6] |

Procedure

Day 1: Cell Culture Preparation

- Culture K562 PEmaxKO cells in appropriate medium (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS) at 37°C, 5% CO₂.

- Ensure cells are in log-phase growth (density 2-5×10⁵ cells/mL) at time of transduction.

Day 2: Lentiviral Transduction

- Design epegRNA with the following components:

- 20 nt spacer sequence complementary to target site

- Scaffold sequence for Cas9 binding

- 10-15 nt primer binding site (PBS)

- 25-40 nt reverse transcription template (RTT) encoding desired edit

- tevopreQ1 stability motif at 3' end [3]

- Package epegRNA into lentiviral particles using standard packaging systems (psPAX2, pMD2.G).

- Transduce K562 PEmaxKO cells at low multiplicity of infection (MOI=0.7) to ensure single copy integration [3].

- Include negative control (non-targeting epegRNA) and positive control (previously validated epegRNA).

Day 3: Selection and Expansion

- Begin antibiotic selection (e.g., 1-2 μg/mL puromycin) 24 hours post-transduction.

- Maintain selection for 5-7 days until >90% of control non-transduced cells are dead.

- Expand selected cell population in fresh medium without selection.

Days 4-30: Monitoring and Harvest

- Passage cells every 3-4 days to maintain log-phase growth.

- Harvest aliquots of 1×10⁶ cells at weekly intervals (days 7, 14, 21, 28) for editing efficiency analysis.

- Extract genomic DNA using standard methods (e.g., column-based extraction).

Editing Efficiency Analysis

- Amplify target region using PCR with barcoded primers.

- Prepare next-generation sequencing libraries and sequence with sufficient coverage (>1000x).

- Analyze sequencing data using computational pipelines to quantify:

- Precise editing rate (% reads with only intended edit)

- Error rate (% reads with unintended edits)

- Unedited rate (% reads with no edit) [3]

Protocol: Error-Reduced Prime Editing with vPE System

For applications requiring maximal precision, the vPE system significantly reduces unwanted edits through Cas9 protein engineering [4].

Specialized Materials

- vPE expression plasmid (available from MIT researchers) [4]

- Modified Cas9 variants with reduced error rate (specific mutations not detailed in source) [4]

- RNA binding protein for template stabilization [4]

Procedure Modifications

- Substitute PEmax with vPE construct in transduction protocol.

- Follow identical transduction and selection steps as in section 4.1.2.

- Compare error rates between standard PE and vPE systems:

The experimental workflow for implementing these protocols is summarized below:

Technical Considerations and Optimization

pegRNA Design and Engineering

The pegRNA is a critical determinant of prime editing efficiency. Optimal design parameters include:

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): 10-15 nucleotides in length with melting temperature of 30-40°C [2]

- Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): 25-40 nucleotides, encoding the desired edit with sufficient flanking homology [2]

- Stability Motifs: Incorporation of structured RNA elements (tevopreQ1, evopreQ, mpknot) at the 3' end to protect against exonucleolytic degradation, improving efficiency 3-4 fold [1]

Addressing Technical Challenges

Successful implementation of prime editing requires addressing several technical challenges:

Delivery Efficiency The large size of prime editing components (Cas9-RT fusion + pegRNA) complicates delivery, particularly for in vivo applications. Effective strategies include:

- Engine viral vectors (dual AAV systems for sPE) [1]

- Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) demonstrating success in clinical applications [7] [8]

- Non-viral delivery methods under development

Minimizing Unwanted Edits Cellular repair pathways can introduce unwanted mutations. Optimization approaches include:

- Engineered Cas9 variants (H840A + N863A) to reduce DSB formation and indel byproducts [1]

- MMR inhibition (MLH1 knockout) to prevent rejection of edited strands [3]

- vPE system with reduced error rates for high-fidelity applications [4]

Immune Considerations The bacterial origin of CRISPR components may trigger immune responses in therapeutic contexts. Mitigation strategies include:

Prime editing represents a significant advancement beyond CRISPR-Cas9, offering researchers and therapeutic developers a precise and versatile genome editing platform that operates without double-strand breaks. The optimized protocols and performance metrics detailed in this Application Note provide a foundation for implementing this technology in both basic research and translational applications. As delivery methods continue to improve and editing efficiencies reach therapeutic thresholds, prime editing holds exceptional promise for addressing the vast landscape of genetic disorders through precise genomic correction.

Prime editing represents a paradigm shift in genome engineering, enabling precise modifications without inducing double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [1] [9]. At its core, the prime editor is a complex molecular machine designed to "search and replace" genetic sequences with high fidelity. This technology significantly expands the scope of editable mutations, allowing for all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, targeted insertions, and deletions [1] [10]. The architecture of this system is fundamentally different from previous CRISPR-Cas9 tools because it divorces the target recognition process from the editing action, offering unprecedented versatility for basic research and therapeutic development [9]. Understanding this architecture is essential for leveraging its full potential in the treatment of genetic disorders.

Core Components of the Prime Editing Machinery

The prime editing system consists of two essential components that work in concert: the prime editor protein and a specialized guide RNA.

The Prime Editor Protein

The prime editor protein is a fusion of two key enzymes:

- A Cas9 Nickase (H840A): This engineered version of the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 protein contains a single active-site mutation (H840A) that enables it to nick only one DNA strand instead of creating a double-strand break [1] [9]. This nicking activity is crucial for initiating the editing process without the genomic instability associated with DSBs.

- A Reverse Transcriptase (RT): Typically derived from the Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV), this enzyme is fused to the Cas9 nickase and is responsible for synthesizing new DNA directly at the target site, using the guide RNA as a template [1] [9].

The Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA)

The pegRNA is a multi-functional RNA molecule that serves both as a targeting mechanism and a template for editing. It contains two distinct regions:

- A Standard sgRNA Spacer Sequence: This portion directs the Cas9 nickase to the specific genomic target site [9].

- A 3' Extension: This critical addition contains two functional elements:

Table 1: Core Components of the Prime Editing System

| Component | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nickase (H840A) | Binds and nicks target DNA strand | Creates single-strand break; prevents DSB formation |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes new DNA containing desired edit | Uses pegRNA template; polymerizes DNA at target site |

| pegRNA | Targets complex and provides edit template | Combines spacer, PBS, and RTT in single molecule |

The Prime Editing Mechanism: A Step-by-Step Workflow

The prime editing mechanism involves a coordinated series of molecular events that result in precise genome modification.

Target Binding and DNA Nicking

The process begins when the pegRNA directs the prime editor fusion protein to the specific target DNA locus through standard Cas9:RNA DNA recognition mechanics. Once bound, the Cas9 nickase (H840A) nicks the non-target strand of the DNA, exposing a 3'-hydroxyl group [1] [9]. This exposed end serves as a primer for the subsequent reverse transcription step.

Primer Binding and Reverse Transcription

The PBS region of the pegRNA hybridizes with the nicked DNA strand, forming a temporary RNA-DNA duplex. The reverse transcriptase then uses the RTT region of the pegRNA as a template to synthesize a new DNA flap containing the desired edit [1] [11]. This newly synthesized DNA is complementary to the RTT and therefore incorporates the programmed genetic change.

Flap Equilibrium and DNA Repair

The editing process creates a branched DNA intermediate with three flaps: the original unedited 5' flap, the newly synthesized edited 3' flap, and the complementary unedited strand [1] [9]. Cellular enzymes resolve this structure by:

- Excising the original unedited 5' flap

- Ligating the edited 3' flap to the complementary DNA strand This results in a heteroduplex DNA molecule with one edited strand and one original unedited strand [1].

Encouraging Permanent Edit Incorporation

To bias cellular repair machinery toward using the edited strand as a template, additional strategies can be employed. The PE3 system introduces a second nick on the non-edited strand using a standard sgRNA, which encourages the cell to use the edited strand as a repair template, thereby increasing editing efficiency [1] [11].

Evolution of Prime Editor Systems: From PE1 to PEmax

Since its initial development, the prime editing system has undergone significant optimization to improve its efficiency and precision.

Table 2: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

| System | Key Features | Editing Efficiency | Indel Formation | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Wild-type M-MLV RT fused to Cas9 nickase | Low (prototype) | Not characterized | Proof-of-concept |

| PE2 | Engineered RT with 5 mutations enhancing activity | 2.3- to 5.1-fold higher than PE1 [9] | Low (1-10%) [9] | Standard editing with optimized RT |

| PE3 | PE2 + additional nicking sgRNA | 2-3-fold higher than PE2 [9] | Moderate increase vs PE2 [9] | High-efficiency editing applications |

| PE4/PE5 | PE2/PE3 + MLH1dn to transiently inhibit MMR | 7.7-fold (PE4) and 2.0-fold (PE5) improvement [9] | Reduced | Editing in MMR-proficient contexts |

| PEmax | Codon-optimized RT, additional NLS, engineered Cas9 | Up to 94.9% in optimized systems [12] | Minimal in MMR-deficient contexts [12] | High-efficiency therapeutic applications |

Protein Engineering Advancements

The evolution from PE1 to PE2 involved engineering the reverse transcriptase domain with five mutations (D200N/L603W/T330P/T306K/W313F) that collectively increase thermostability, processivity, and affinity for RNA-DNA hybrid substrates [1] [9]. These modifications significantly enhanced editing efficiency without increasing off-target effects.

The PEmax architecture further optimized the system through codon optimization for human cells, addition of nuclear localization signals, and incorporation of mutations known to improve Cas9 activity [9]. When combined with engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) that include structured RNA motifs like evopreQ1 or mpknot at their 3' end to prevent degradation, these systems achieve remarkably high editing efficiencies of up to 94.9% in certain contexts [1] [12].

Manipulating Cellular DNA Repair

A critical insight in prime editing development was understanding how cellular DNA repair pathways, particularly mismatch repair (MMR), influence editing outcomes. The PE4 and PE5 systems address this by transiently expressing a dominant-negative version of the MLH1 protein (MLH1dn) to temporarily inhibit MMR, which biases repair toward the edited strand and can improve editing efficiency by up to 7.7-fold [11] [9].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Prime Editing in Mammalian Cells

The following protocol outlines key steps for implementing prime editing in mammalian cells, based on established methodologies [11] [12].

pegRNA and Template Design

- Target Selection: Identify the target genomic locus, ensuring the PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) is present. Prime editing can install edits at positions ranging from immediately adjacent to the PAM to over 30 base pairs away [9].

- pegRNA Design:

- Design the spacer sequence (approximately 20 nt) to target the desired locus.

- Define the RTT sequence to encode your desired edit(s). The RTT typically ranges from 10-16 nucleotides for optimal efficiency [11].

- Design the PBS sequence (typically 10-16 nt) complementary to the 3' flap created after nicking.

- Nicking sgRNA Design (for PE3/PE5): If using PE3 or PE5 systems, design an additional sgRNA to nick the non-edited strand. The optimal nicking site is typically 40-100 bp away from the pegRNA nicking site to avoid creating a double-strand break [11].

Delivery and Expression of Editing Components

- Editor Expression: Deliver the prime editor (PE2, PEmax, etc.) using appropriate expression systems. For therapeutic applications, the split prime editor (sPE) system enables delivery via dual AAV vectors [1].

- pegRNA Delivery: Express pegRNAs using RNA polymerase III promoters (U6 is commonly used). For enhanced stability, use engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) with 3' RNA motifs like tevopreQ1 [1] [12].

- MMR Inhibition (for PE4/PE5): For PE4/PE5 systems, co-express the MLH1dn protein to transiently inhibit mismatch repair [11] [9].

Optimization and Validation

- Efficiency Optimization: Test multiple pegRNAs with varying PBS and RTT lengths (typically 10-16 nt) to identify optimal designs [11].

- Editing Analysis: Assess editing efficiency 3-7 days post-transfection using next-generation sequencing of PCR-amplified target regions.

- Byproduct Analysis: Quantify indel formation and other unwanted editing outcomes through detailed sequence analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Prime Editing

| Reagent | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | Express the fusion protein | PE2, PEmax; mammalian codon optimization preferred |

| pegRNA Expression Vectors | Express pegRNA with structural motifs | U6 promoter-driven; epegRNA designs with evopreQ1/mpknot |

| MMR Inhibition System | Enhance editing efficiency | MLH1dn expression for PE4/PE5 systems |

| Nicking sgRNA Vectors | For PE3/PE5 systems | Standard sgRNA expression for non-edited strand nicking |

| Delivery Tools | Introduce editing components | Lentivirus, AAV (split systems), electroporation, lipofection |

| Validation Primers | Amplify target locus for sequencing | Should flank edit site by ≥50 bp on each side |

Advanced Architectures: Specialized Prime Editing Systems

Recent innovations have expanded the prime editing toolbox with specialized systems designed to address specific challenges.

Reverse Prime Editing (rPE)

A recently developed variant called reverse prime editing (rPE) utilizes Cas9-D10A instead of Cas9-H840A and is programmed with a reverse pegRNA (rpegRNA) that binds to the targeted DNA strand rather than the non-targeted strand [13]. This architecture creates a reverse editing window that enables modifications at the 3' direction of the HNH-mediated nick site, expanding the targeting scope of prime editing and potentially offering higher fidelity by reducing unwanted DSB formation [13].

PE6 Systems

The PE6 systems represent a collection of specialized editors derived from phage-assisted evolution. These include:

- PE6a/b: Compact editors using RT domains from bacterial retrons or retrotransposons

- PE6c/d: Evolved editors optimized for AAV delivery

- PE6e-g: Editors with mutations in the Cas9 domain that show unpredictable but sometimes dramatic efficiency improvements for specific edits [9]

Twin Prime Editing

For larger modifications, twinPE systems use two pegRNAs that target opposite DNA strands to install complementary edits, enabling precise deletions, insertions, or inversions of dozens to hundreds of base pairs [11]. When combined with recombinase systems, this approach can facilitate gene-sized insertions of over 5 kilobases [11].

The modular architecture of the prime editor complex—comprising a Cas9 nickase, reverse transcriptase, and multifunctional pegRNA—provides a versatile foundation for precise genome manipulation without double-strand breaks. Through systematic optimization of each component and thoughtful engagement with cellular repair pathways, prime editing systems have evolved from proof-of-concept tools to highly efficient platforms capable of installing a wide range of genetic modifications. As delivery methods continue to improve and our understanding of the cellular context deepens, this technology holds exceptional promise for developing one-time treatments for diverse genetic disorders, potentially benefiting large patient populations with a single therapeutic agent.

Prime editing represents a transformative advance in precision genome editing, enabling the installation of targeted insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible point mutations without requiring double-strand DNA breaks (DSBs) or donor DNA templates [2] [14]. This technology substantially expands the scope of therapeutic genome editing for genetic disorders. The prime editing system consists of two core components: a prime editor protein and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA). The prime editor is a fusion protein comprising a Cas9 nickase (H840A) that cleaves only a single DNA strand and an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) [2] [11]. The pegRNA serves as the blueprint that directs both the targeting and the editing functions of the system, making its design critical for successful experimental outcomes.

The pegRNA molecule is fundamentally a dual-function guide that uniquely integrates both targeting and editing instructions within a single RNA entity [2] [15]. Unlike traditional CRISPR single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that only specify the target genomic location, the pegRNA additionally encodes the desired genetic modification. This dual functionality enables the "search-and-replace" capability that distinguishes prime editing from previous genome editing technologies. The pegRNA directs the prime editor complex to a specific DNA site through its spacer sequence and simultaneously provides the template for reverse transcription to write new genetic information into the genome [14] [11]. This comprehensive guide explores the molecular architecture of pegRNAs, quantitative design parameters, optimized experimental protocols, and advanced applications to empower researchers leveraging prime editing for therapeutic development.

Molecular Architecture of the pegRNA

The pegRNA consists of four essential sequence components that collectively enable its dual targeting and editing functions. Each structural element plays a distinct and critical role in the prime editing mechanism [2] [16].

- Spacer Sequence: A 20-nucleotide sequence that directs the Cas9 nickase to the specific target DNA site through complementary base pairing, fulfilling the "search" function of the system [2] [11].

- Scaffold Sequence: Maintains the secondary structure necessary for proper binding to the Cas9 nickase protein, enabling the formation of the ribonucleoprotein complex [2].

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): Typically 10-15 nucleotides in length, the PBS anneals to the nicked DNA strand after target recognition, serving as an anchor point for the reverse transcriptase to initiate DNA synthesis [2] [16].

- Reverse Transcription Template (RTT): Contains the desired edit and additional homology sequence, typically ranging from 10-30 nucleotides. The RTT serves as the direct template for the reverse transcriptase to synthesize the edited DNA strand, fulfilling the "replace" function [2] [11].

The complete pegRNA molecule generally ranges from 120-145 nucleotides in length, though more complex edits may require longer constructs up to 170-190 nucleotides [2]. This extended length compared to traditional sgRNAs (approximately 100 nucleotides) presents unique challenges in synthesis, delivery, and cellular stability that must be addressed through thoughtful experimental design.

Diagram 1: Structural components of pegRNA showing the four essential sequence elements that enable its dual targeting and editing functions.

Quantitative Design Parameters for pegRNA Optimization

Systematic analysis of pegRNA editing outcomes has revealed critical parameters that significantly influence editing efficiency. The following tables summarize evidence-based design guidelines derived from large-scale pegRNA screens and optimization studies.

Table 1: Optimal design parameters for pegRNA components based on empirical efficiency data

| Component | Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Efficiency | Design Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | Length | 13 nt [17] | Medium | Start with 13 nt, test 10-15 nt range [16] |

| GC Content | 40-60% [16] | High | Avoid extremes (<30% or >70%) | |

| Melting Temp | ~38°C [17] | High | Match to cellular temperature | |

| RTT | Length | 10-16 nt [16] | Medium | Test multiple lengths |

| Overhang Length | Longer preferred [17] | High | Increase for better efficiency | |

| Edit Position | Include PAM modification [16] | High | Prevents re-cutting | |

| Spacer | Consecutive T's | Avoid >3 [17] | Critical | 4+ T's reduces efficiency to <10% |

Table 2: Editing efficiency by mutation type and sequence context

| Edit Type | Median Efficiency | Sequence Context Influence | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Mutations | 52% [17] | A-to-G most efficient [17] | Add silent mutations for 3+ base "bubbles" [16] |

| Insertions | 31% [17] | Inverse correlation with length [17] | Test multiple RTT overhangs |

| Deletions | 31% [17] | Inverse correlation with length [17] | Ensure sufficient homology |

| All Types | 46% overall median [17] | G/C flanking bases beneficial [17] | Avoid polyT stretches in spacer/RTT |

The editing efficiency varies substantially depending on the specific mutation type and sequence context. Point mutations generally install more efficiently than insertions or deletions, with A-to-G conversions showing particularly high efficiency, potentially due to strand-specific bias in repairing G:T mismatches [17]. For all edit types, the length of the insertion or deletion inversely correlates with efficiency, with longer edits typically showing reduced success rates [17].

A critical design consideration is the inclusion of PAM-modifying edits when possible. When the prime editing system successfully installs an edit that alters the PAM sequence, it prevents the Cas9 nickase from re-binding and re-nicking the newly synthesized strand, thereby reducing indel formation and increasing the purity of editing outcomes [16]. Additionally, introducing multiple silent mutations near the primary edit to create "bubbles" of three or more mismatched bases can help evade cellular mismatch repair (MMR) systems, which more efficiently target single-base mismatches [16].

Experimental Protocols for pegRNA Design and Testing

pegRNA Design Workflow

The following step-by-step protocol ensures systematic design and testing of pegRNAs for optimal editing efficiency:

Target Site Selection: Identify the target genomic locus and desired edit. Select a protospacer adjacent to the edit site with an NGG PAM sequence on the same strand. Verify that no polyT stretches (≥3 consecutive T's) exist in the spacer sequence [17].

pegRNA Component Design:

- Design the spacer sequence (20 nt) complementary to the target DNA.

- Design the PBS sequence (13 nt starting point) complementary to the 3' end of the nicked DNA strand.

- Design the RTT sequence encoding the desired edit with 10-16 nt of homology beyond the edit site.

- Ensure the first base of the 3' extension is not C to prevent non-canonical base pairing with G81 of the gRNA scaffold [16].

pegRNA Cloning: Clone the pegRNA sequence into an appropriate expression vector using standardized molecular biology techniques. For high-throughput applications, consider using the Prime Editing Guide Generator (PEGG) Python package for automated design [18].

Delivery and Expression: Co-deliver the pegRNA and prime editor (PE2) to cells using optimized methods such as lipid nanoparticles, electroporation, or viral vectors. Use strong RNA polymerase III promoters (e.g., U6) for pegRNA expression [2] [11].

Efficiency Validation: Harvest cells 3-7 days post-editing and extract genomic DNA. Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze editing efficiency using next-generation sequencing or targeted assays.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for pegRNA design and testing, showing the five critical steps from target selection to efficiency validation.

Advanced Prime Editing Systems

Later-generation prime editing systems incorporate additional components to enhance efficiency and specificity. The PE3 system introduces a second sgRNA that directs nicking of the non-edited strand to bias cellular repair toward the edited sequence [11] [15]. The PE3b variant designs this nicking sgRNA to bind only after successful editing, reducing concurrent nicks and minimizing indel formation [16]. The PE4 and PE5 systems incorporate dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) to transiently inhibit mismatch repair, increasing editing efficiency by preventing reversion of edits [11] [15]. When using these advanced systems, specific design considerations apply:

- For PE3/PE5: Test multiple nicking sgRNA sites, starting with positions approximately 50 bp upstream and downstream from the prime editing nick site [16].

- For PE3b/PE5b: Design the nicking sgRNA to target the edited DNA sequence, ensuring it only binds after successful edit installation [16].

- For PE4/PE5: Ensure the pegRNA scaffold sequence lacks homology to the target genomic sequence to prevent unintended incorporation when MMR is inhibited [16].

Table 3: Evolution of prime editing systems and their experimental applications

| System | Key Components | Editing Efficiency | Best For | Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE2 | Cas9 nickase + engineered RT | 20-40% [15] | Basic edits, minimal indels | No nicking sgRNA needed |

| PE3 | PE2 + nicking sgRNA | 30-50% [15] | Higher efficiency needs | Test multiple nick sites [16] |

| PE3b | PE2 + edit-specific nick | 30-50% [15] | Reducing indel byproducts | Nicking sgRNA targets edited sequence [16] |

| PE4 | PE2 + MLH1dn | 50-70% [15] | MMR-proficient cell types | Avoid scaffold homology [16] |

| PE5 | PE3 + MLH1dn | 60-80% [15] | Maximum efficiency | Combine nicking & MMR inhibition |

Research Reagent Solutions for Prime Editing Applications

Successful implementation of prime editing requires carefully selected reagents and tools. The following toolkit provides essential resources for researchers developing pegRNA-based experiments.

Table 4: Essential research reagents and tools for pegRNA experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Proteins | PE2, PEmax [11] | Catalyze targeted DNA modification | PEmax improves nuclear localization |

| pegRNA Design Tools | PRIDICT [17], PEGG [18] | Predict efficiency and design sequences | PRIDICT achieves Spearman's R=0.85 [17] |

| Stabilized pegRNAs | epegRNAs [16], PE7 system [15] | Protect against degradation | epegRNAs use structured RNA motifs |

| Delivery Systems | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [2], AAV [5] | Cellular delivery of editing components | LNPs effective for RNA delivery |

| Efficiency Sensors | Prime editing sensor libraries [18] | Quantify editing outcomes | Couples pegRNAs with target sites |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The versatility of pegRNA-guided prime editing has enabled sophisticated applications beyond single nucleotide changes. Twin prime editing (twinPE) systems use two pegRNAs to precisely insert or delete hundreds of base pairs, enabling gene-sized (>5 kb) insertions when combined with recombinase systems [11]. In therapeutic development, prime editing has been applied to correct primary genetic causes of sickle cell disease and Tay-Sachs disease in human cells [14], and more recently to install suppressor tRNAs that can read through premature termination codons in a disease-agnostic manner [5] [19].

The emerging PERT (prime editing-mediated readthrough of premature termination codons) approach demonstrates how pegRNA design can enable broadly applicable therapeutic strategies. Rather than correcting individual nonsense mutations, PERT uses prime editing to convert a redundant endogenous tRNA into an optimized suppressor tRNA, allowing readthrough of premature stop codons regardless of their specific genomic context [5] [19]. This approach restored 20-70% of normal enzyme activity in cell models of Batten disease, Tay-Sachs disease, and Niemann-Pick disease type C1 using the same prime editing composition [5].

High-throughput screening approaches using prime editing sensor libraries have further expanded pegRNA applications, enabling functional assessment of thousands of genetic variants in their endogenous genomic context [18]. These screens couple pegRNAs with synthetic versions of their cognate target sites to quantitatively assess editing efficiency and functional impact simultaneously, providing powerful resources for characterizing pathogenic variants in genes like TP53 [18].

As prime editing continues to evolve, pegRNA design remains foundational to its advancing applications. Ongoing optimization of pegRNA stability through engineered motifs (epegRNAs) [16] and protective binding proteins (PE7 system) [15] [16], coupled with improved computational prediction tools like PRIDICT [17], will further enhance the precision and efficiency of this transformative genome editing technology.

The Step-by-Step Mechanism of Precision DNA Repair

Prime editing represents a transformative advance in precision genome editing, offering a versatile "search-and-replace" capability for modifying DNA without introducing double-strand breaks (DSBs) [20] [9]. This technology addresses a critical limitation in the therapeutic correction of genetic disorders, as DSBs can lead to unintended insertions, deletions, and chromosomal rearrangements that compromise safety and efficacy [1] [21]. By enabling precise corrections at the single-base level and facilitating small insertions and deletions, prime editing provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful tool to address the root causes of genetic diseases.

The fundamental innovation of prime editing lies in its ability to mediate targeted DNA changes without relying on donor DNA templates or the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway that often dominates DSB repair [20] [9]. This breakthrough is particularly significant for therapeutic applications, where minimizing off-target effects and maximizing product purity are paramount concerns. Prime editing systems have demonstrated capability in correcting a wide spectrum of genetic mutations, including point mutations, insertions, and deletions, which collectively account for approximately 75,000 known pathogenic human genetic variants [9] [22].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies

| Editing Technology | Editing Capabilities | DSB Formation | Donor DNA Required | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Nuclease | Indels via NHEJ | Yes | No (for disruption) | High indel rates, chromosomal abnormalities |

| Base Editing | C•G to T•A, A•T to G•C | No | No | Restricted to 4 transition mutations, bystander editing |

| Prime Editing | All 12 base-to-base conversions, insertions, deletions | No | No | Variable efficiency across sites and cell types |

Molecular Mechanism of Prime Editing

Core Components of the Prime Editing System

The prime editing system consists of two essential molecular components that work in concert to enable precise genome modification. First, the prime editor protein is a fusion of a Cas9 nickase (H840A mutant) and a reverse transcriptase (RT) domain [20] [2]. The Cas9 nickase provides DNA targeting specificity through its guide RNA-binding capability but is engineered to cut only one DNA strand instead of creating double-strand breaks. The reverse transcriptase domain, typically derived from Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV), synthesizes DNA using an RNA template [2] [9].

Second, the prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) serves both targeting and templating functions [2]. Unlike conventional single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs), pegRNAs contain a 3' extension that includes a primer binding site (PBS) and a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) encoding the desired edit [2] [1]. The standard pegRNA architecture consists of: (1) a ~20-nucleotide spacer sequence that specifies the target genomic locus through complementary base pairing; (2) a scaffold sequence that binds the Cas9 nickase; (3) a primer binding site (typically 10-15 nucleotides) that anneals to the nicked DNA strand to initiate reverse transcription; and (4) a reverse transcription template (typically 25-40 nucleotides) containing the desired genetic alteration flanked by homologous sequences [2].

Step-by-Step Molecular Mechanism

The prime editing process follows an ordered sequence of molecular events that enables precise rewriting of genetic information:

Target Recognition and Binding: The prime editor-pegRNA complex scans the genome and binds to the target DNA sequence specified by the pegRNA spacer through complementary base pairing [2] [1]. This binding forms an R-loop structure where the DNA duplex is partially unwound, exposing the target strand for editing.

DNA Strand Nicking: The Cas9 nickase (H840A) component creates a single-strand break (nick) in the non-target DNA strand at a precise position determined by the pegRNA-spacer complex [20] [2]. This nick generates a 3'-hydroxyl group that serves as a primer for reverse transcription.

Primer Binding and Reverse Transcription: The primer binding site (PBS) within the pegRNA anneals to the complementary sequence on the nicked DNA strand. The reverse transcriptase domain then uses the 3'-hydroxyl group as a primer and the RTT region of the pegRNA as a template to synthesize a new DNA strand containing the desired edit [2] [9]. This process directly copies the edited sequence from the pegRNA into the DNA.

Flap Intermediation and Resolution: The newly synthesized edited DNA strand forms a 3' flap structure that displaces the original unedited 5' DNA flap [20] [1]. Cellular repair machinery then resolves this branched DNA intermediate through flap dynamics, where the 5' flap (typically containing the original sequence) is excised, and the edited 3' flap is ligated into the genome.

Heteroduplex Resolution: The editing process creates a heteroduplex DNA structure with one strand containing the edit and the complementary strand retaining the original sequence [9]. Cellular mismatch repair (MMR) pathways then resolve this heteroduplex, potentially copying the edit to the complementary strand to permanently incorporate the genetic change.

Diagram 1: Prime Editing Mechanism - This diagram illustrates the sequential molecular steps in prime editing, from target recognition to final edited DNA duplex formation.

DNA Repair Pathways in Prime Editing

Prime editing leverages and manipulates endogenous DNA repair pathways to achieve permanent genetic changes. The process primarily involves three key repair mechanisms:

Flap Excision and Ligation: The 5' flap containing the original sequence is recognized and removed by structure-specific endonucleases such as XPF-ERCC1 and FEN1 [20]. DNA ligases then seal the nick between the edited flap and the genomic DNA, incorporating the edit into one strand of the DNA duplex [23].

Mismatch Repair (MMR) Modulation: The heteroduplex formed after flap resolution activates cellular MMR machinery, which can either preserve the edit by using the edited strand as a template or revert the change by excising the edited strand [9] [21]. Recent prime editing enhancements (PE4/PE5 systems) temporarily inhibit the MLH1 component of the MMR pathway to bias resolution toward the edited strand, significantly improving efficiency [9] [21].

DNA Replication-Dependent Fixation: In dividing cells, DNA replication permanently fixes the edit by generating daughter DNA molecules that either contain or lack the modification. The edited strand serves as a template during replication, increasing the likelihood of permanent edit incorporation [20].

Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

Development of Prime Editor Generations

Since its initial development in 2019, prime editing technology has evolved through multiple generations with significant improvements in efficiency and fidelity:

PE1 was the original prime editor, consisting of a wild-type M-MLV reverse transcriptase fused to Cas9 nickase (H840A) [20] [1]. While it demonstrated proof-of-concept, editing efficiency was modest (typically <5% of targeted alleles) [20].

PE2 incorporated an engineered reverse transcriptase with five mutations (D200N/L603W/T330P/T306K/W313F) that enhanced thermostability, processivity, and binding to template-primer complexes [20] [9]. These modifications resulted in a 1.6- to 5.1-fold increase in editing efficiency compared to PE1 [20].

PE3 introduced a second sgRNA that directs nicking of the non-edited strand to bias cellular repair toward the edited strand [20] [1]. This system increases editing efficiency by 2-3-fold but slightly elevates indel formation [20]. PE3b is a refined version where the additional sgRNA is designed to bind only after the edit is incorporated, reducing indels by 13-fold [9].

Table 2: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

| Prime Editor Version | Key Features | Improvements | Efficiency Range | Indel Formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Wild-type M-MLV RT + nCas9 (H840A) | Foundation | 0.7-17% | Low |

| PE2 | Engineered RT (5 mutations) + nCas9 | 1.6-5.1× over PE1 | 1.8-53% | Low |

| PE3/PE3b | PE2 + additional sgRNA for non-edited strand nicking | 2-3× over PE2 | 5.5-63% | Moderate |

| PE4/PE5 | PE2/PE3 + MLH1dn MMR inhibition | 7.7× (PE4) and 2.0× (PE5) over predecessors | Up to 78% | Low with improved edit:indel ratio |

| PEmax | Codon-optimized RT, additional NLS, Cas9 mutations | Enhanced expression and activity | Varies by target | Low |

| PE6a-g | Evolved RT domains from various sources | Improved efficiency with specific edits | Target-dependent | Low |

Enhancing Prime Editing Efficiency

Recent advances have focused on addressing limitations in prime editing efficiency through multiple engineering approaches:

pegRNA Engineering: The development of engineered pegRNAs (epegRNAs) incorporated structured RNA motifs (evopreQ1, mpknot, xrRNA) at the 3' end to protect against exonuclease degradation [1]. These modifications improved editing efficiency by 3-4-fold across multiple human cell lines and primary fibroblasts without increasing off-target effects [1].

MMR Pathway Modulation: The PE4 and PE5 systems co-express a dominant-negative version of the MLH1 protein (MLH1dn) to temporarily suppress mismatch repair activity that often reverses prime edits [9] [21]. This approach improves editing efficiency by 7.7-fold for PE4 (compared to PE2) and 2.0-fold for PE5 (compared to PE3) [9].

Protein Engineering: The PEmax architecture incorporates codon optimization for human cells, additional nuclear localization signals, and beneficial mutations in the Cas9 domain to improve expression and activity [9]. The PE6 series further evolved the reverse transcriptase domain through phage-assisted continuous evolution, creating specialized editors optimized for different types of edits [9].

Dual Flap Systems: Advanced approaches like Twin Prime Editing use two pegRNAs to create complementary edits on both DNA strands, improving efficiency for larger modifications and reducing reliance on cellular repair pathways [22].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Prime Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Proteins | PE2, PEmax, PE6 variants | Catalyze the prime editing reaction | Size affects delivery efficiency; specificity varies |

| Guide RNAs | pegRNAs, epegRNAs | Target specificity and edit templating | Length (120-145 nt) affects synthesis yield and stability |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation | Introduce editing components into cells | Must accommodate large size of editor and pegRNA |

| MMR Modulators | MLH1dn | Enhance editing efficiency | Transient expression recommended to minimize risks |

| Validation Tools | Next-generation sequencing, T7E1 assay | Confirm editing outcomes and detect off-target effects | Amplicon sequencing provides quantitative assessment |

Detailed Protocol for Prime Editing in Zebrafish Models

Prime editing has been successfully implemented in zebrafish (Danio rerio), providing a valuable model for studying human disease variants in a vertebrate system [24]. The following protocol has been optimized for precise nucleotide substitutions and small insertions:

Component Preparation:

- Synthesize PE2 mRNA using in vitro transcription with codon-optimized sequences for zebrafish expression [24].

- Chemically synthesize pegRNAs with a 13-nucleotide primer binding site (PBS) and appropriate reverse transcription template (RTT) encoding the desired edit [24].

- For 3-bp insertions (e.g., stop codon introduction), include a 13-nucleotide homology arm extension in the RTT template [24].

Microinjection Setup:

- Prepare an injection mixture containing 300 ng/μL PE2 mRNA and 100 ng/μL pegRNA in nuclease-free water [24].

- Load the mixture into glass capillary needles calibrated for zebrafish embryo injection.

- Collect one-cell stage zebrafish embryos and align them on an injection mold.

Embryo Injection and Incubation:

- Microinject 1-2 nL of the ribonucleoprotein mixture into the cytoplasm of one-cell stage zebrafish embryos [24].

- Incubate injected embryos at 32°C in E3 embryo medium, refreshing daily [24].

- Monitor embryonic development daily until 96 hours post-fertilization (hpf) for phenotypic analysis.

Editing Efficiency Assessment:

- At 96 hpf, extract genomic DNA from pooled (n=10) or individual embryos using standard protocols [24].

- Amplify the target region by PCR using gene-specific primers flanking the edit site.

- Quantify editing efficiency using amplicon sequencing or for rapid assessment, use T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay to detect sequence modifications [24].

- Calculate precision scores as the ratio of precise prime edits to total edits (including imprecise edits and indels) [24].

Germline Transmission:

- Raise injected embryos (F0) to adulthood and outcross with wild-type fish.

- Screen F1 offspring for the desired edit using PCR and sequencing.

- Establish stable transgenic lines from edit-positive F1 fish.

This protocol has demonstrated 8.4% efficiency for nucleotide substitutions using PE2 compared to 4.4% with nuclease-based PEn editors in zebrafish, with significantly higher precision scores (40.8% vs. 11.4%) [24].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 4: Prime Editing Efficiency Across Experimental Systems

| Application | Editor System | Edit Type | Efficiency | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293T Cells [9] | PE2 | Point mutations | 20-50% | 1-10% indels |

| Zebrafish crbn Gene [24] | PE2 | 2-nt substitution | 8.4% | Precision score: 40.8% |

| Zebrafish crbn Gene [24] | PEn | 2-nt substitution | 4.4% | Precision score: 11.4% |

| Human Cell Lines [1] | PE2 + epegRNA | Multiple edits | 3-4× improvement | Across 10 targets |

| Therapeutic Correction [25] | PE | Sickle cell mutation | ~40% | Patient-derived stem cells |

Diagram 2: Prime Editing Workflow - This diagram outlines the complete experimental workflow for prime editing applications, from component design to final validation.

Prime editing represents a significant advancement in precision genome editing technology, offering researchers and therapeutic developers an unprecedented ability to correct genetic mutations without inducing double-strand breaks. The step-by-step mechanism—from target recognition and DNA nicking to reverse transcription and flap resolution—provides a foundation for understanding how this technology achieves its remarkable precision [20] [2]. The evolution of prime editing systems from PE1 through PE6, coupled with enhancements in pegRNA design and MMR modulation, has substantially improved editing efficiencies while maintaining high specificity [1] [9] [21].

For the research community, prime editing opens new possibilities for modeling genetic diseases, studying gene function, and developing transformative therapies. The successful application in zebrafish models demonstrates the technology's versatility across biological systems [24]. As delivery methods continue to improve and our understanding of DNA repair mechanisms deepens, prime editing is poised to become an increasingly powerful tool for addressing genetic disorders with unprecedented precision and safety profiles.

The future of prime editing will likely focus on enhancing delivery efficiency, expanding targeting scope through engineered Cas variants with altered PAM requirements, and developing more sophisticated control over DNA repair pathways to further improve editing outcomes [26] [22]. With these advancements, prime editing holds exceptional promise for realizing the full potential of therapeutic genome editing for a broad spectrum of human genetic diseases.

Prime editing represents a transformative advancement in precision genome engineering, offering a versatile "search-and-replace" methodology that enables precise genetic modifications without inducing double-strand breaks (DSBs) or requiring donor DNA templates [1] [27]. This technology significantly expands the capabilities of genetic disorder research and therapeutic development by supporting a wide range of genetic modifications, including all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, targeted insertions, and deletions [1] [2]. By avoiding DSBs, prime editing addresses critical safety concerns associated with earlier CRISPR-Cas9 systems, which often led to unintended mutations, chromosomal rearrangements, and activation of cellular stress responses [1] [28].

The fundamental prime editing system consists of two core components: a prime editor protein and a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [1] [2]. The prime editor is a fusion protein comprising a Cas9 nickase (H840A) capable of cutting only a single DNA strand, coupled with an engineered reverse transcriptase (RT) from the Moloney-Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) [1] [15]. The pegRNA serves both as a targeting mechanism and a template for new genetic information, containing a spacer sequence that identifies the target DNA site, a reverse transcriptase template (RTT) encoding the desired edit, and a primer binding site (PBS) that facilitates the initiation of reverse transcription [2].

Table 1: Core Components of Prime Editing Systems

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nickase (H840A) | Modified Cas9 protein that nicks rather than cleaves DNA | Creates single-strand break to initiate editing process |

| Reverse Transcriptase (RT) | Engineered M-MLV reverse transcriptase | Synthesizes DNA using pegRNA template |

| pegRNA | Specialized guide RNA with 3' extension | Targets specific locus and encodes desired edit |

| Reverse Transcriptase Template (RTT) | Sequence within pegRNA 3' extension | Contains the desired genetic modification |

| Primer Binding Site (PBS) | Region within pegRNA 3' extension | Anneals to nicked DNA to initiate reverse transcription |

The prime editing mechanism operates through a sophisticated multi-step process [2]. First, the prime editor-pegRNA complex binds to the target DNA sequence through standard Cas9 targeting mechanisms. The Cas9 nickase then creates a single-strand break in the DNA, exposing a 3'-hydroxyl group that serves as a primer for reverse transcription. The PBS region of the pegRNA anneals to the complementary DNA region adjacent to the nick, positioning the RT template for reverse transcription. The reverse transcriptase then synthesizes a new DNA strand using the RTT as a template, incorporating the desired edit. Finally, cellular repair mechanisms resolve the resulting DNA heteroduplex, incorporating the edited strand into the genome [1] [2].

The Evolution of Prime Editor Systems: From PE1 to PE7

The development of prime editing has followed a rapid iterative path, with each generation introducing significant improvements in efficiency, precision, and versatility. This evolution has addressed key challenges including editing efficiency, product purity, and delivery constraints.

Early Generations: PE1 to PE3

The initial prime editor, PE1, demonstrated the proof-of-concept for search-and-replace genome editing but exhibited modest efficiency of approximately 10-20% in HEK293T cells [15]. PE2 incorporated engineered mutations in the M-MLV reverse transcriptase to enhance thermostability, processivity, and affinity for RNA-DNA hybrid substrates, resulting in improved editing outcomes with efficiencies of 20-40% [1] [15]. PE3 further augmented this system by incorporating an additional sgRNA that nicks the non-edited DNA strand, encouraging cellular repair machinery to use the newly synthesized edited strand as a template and increasing editing efficiency to 30-50% [1] [15].

Advanced Systems: PE4 to PE7

Later generations of prime editors implemented increasingly sophisticated approaches to overcome cellular barriers to efficient editing, particularly mismatch repair (MMR) pathways that often reverse prime edits [15] [2]. PE4 and PE5 systems addressed this limitation by incorporating a dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) protein to inhibit the MMR pathway, increasing editing efficiency to 50-70% for PE4 and 60-80% for PE5 [15]. The PE6 system introduced multiple variants with compact reverse transcriptase domains (PE6a, PE6b, PE6c) and enhanced Cas9 variants (PE6e, PE6f, PE6g) to improve delivery efficiency, achieving 70-90% editing efficiency in HEK293T cells [15]. Most recently, PE7 demonstrated further refinements by fusing the La(1-194) protein to the prime editor complex to enhance pegRNA stability and editing outcomes, reaching remarkable efficiencies of 80-95% in human cells [15].

Table 2: Evolution of Prime Editing Systems

| Editor Version | Key Components | Editing Efficiency | Major Innovations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | nCas9(H840A) + M-MLV RT | ~10-20% | Proof-of-concept system |

| PE2 | nCas9(H840A) + engineered RT | ~20-40% | Optimized reverse transcriptase |

| PE3 | PE2 + additional sgRNA | ~30-50% | Dual-nicking strategy |

| PE4 | PE2 + MLH1dn | ~50-70% | MMR inhibition |

| PE5 | PE3 + MLH1dn | ~60-80% | Combined nicking + MMR inhibition |

| PE6 | Compact RT variants + epegRNAs | ~70-90% | Improved delivery and stability |

| PE7 | La protein fusion + epegRNAs | ~80-95% | Enhanced pegRNA stability |

Diagram 1: The evolutionary pathway of prime editing systems from PE1 to PE7, highlighting major innovations at each stage.

Cas12a Prime Editing Systems

While most prime editors utilize Cas9-derived nickases, recent research has explored alternative CRISPR effectors to expand targeting scope and overcome limitations. Cas12a-based prime editing systems represent a significant advancement in this direction, offering distinct advantages including different protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) requirements and simpler guide RNA architectures [29] [15].

Cas12a prime editors employ a nickase variant of Cas12a (R1226A) fused with reverse transcriptase and utilize a circular RNA for reverse transcription [15]. This system demonstrates particular strength in targeting T-rich PAM sequences, complementing the G-rich PAM preference of Cas9-based systems and thereby expanding the total targetable genomic space [29]. In benchmarking studies, improved LbCas12a (impLbCas12a) has been identified as the most efficient and PAM-relaxed Cas12a variant in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, showing high editing purity and a well-defined editing window centering on the double-strand break [29].

The Cas12a prime editing system has demonstrated robust efficiency, achieving editing rates of up to 40.75% in HEK293T cells while maintaining a smaller size compared to Cas9-based systems, which offers advantages for viral packaging and delivery [15]. This compact architecture, combined with its preferential targeting of T-rich PAM regions, makes Cas12a prime editing particularly valuable for applications requiring access to genomic regions inaccessible to Cas9-based editors.

Experimental Protocols for Prime Editing

Prime Editing Workflow for Genetic Disorder Research

The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for implementing prime editing in mammalian cell lines for genetic disorder research, incorporating best practices from recent advancements.

Day 1: Cell Seeding

- Plate HEK293T cells (or relevant cell model for the genetic disorder being studied) in a 24-well plate at a density of 1.0 × 10^5 cells per well in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

- Incubate cells at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 24 hours to achieve 70-80% confluency at time of transfection.

Day 2: Plasmid Transfection

- For each sample, prepare a transfection mixture containing:

- 500 ng prime editor expression plasmid (PE2, PE3, or later variant)

- 250 ng pegRNA expression plasmid

- For PE3 systems: 250 ng additional nicking sgRNA plasmid

- 1.5 μL Lipofectamine 3000 in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium

- Incubate the transfection mixture for 15 minutes at room temperature

- Add mixture dropwise to cells with complete medium exchange

- Incubate cells for 72 hours at 37°C with 5% CO₂

Day 5: Harvest and Analysis

- Extract genomic DNA using commercial extraction kits

- Amplify target region by PCR using specific primers flanking the edit site

- Analyze editing efficiency via next-generation sequencing or restriction fragment length polymorphism

- For therapeutic applications, assess cell viability and potential off-target effects

EXPERT System Protocol for Extended Editing Range

The recently developed EXPERT (extended prime editor system) protocol enables editing on both sides of the pegRNA nick, significantly expanding the editable genomic region [30].

Design Phase:

- Design extended pegRNA (ext-pegRNA) with elongated 3' extension containing:

- Primer binding site (PBS: 10-15 nt)

- Edit sequence (ES: variable length)

- Homologous sequence (HS: 25-40 nt)

- Design upstream sgRNA (ups-sgRNA) targeting genomic region 5' of the pegRNA nick site

- Verify that both nicks created by the system are in cis configuration (same DNA strand)

Experimental Setup:

- Co-transfect cells with:

- 500 ng prime editor plasmid (PE2 architecture)

- 300 ng ext-pegRNA expression plasmid

- 300 ng ups-sgRNA expression plasmid

- Include controls with single guide systems (EXPERT-a and EXPERT-b) to validate performance

Validation and Optimization:

- Assess editing efficiency via sequencing across target region

- Quantify indel formation using TIDE decomposition or similar methods

- For large fragment edits (>50 bp), optimize HS length to enhance efficiency

- EXPERT has demonstrated 3.12-fold average improvement in editing efficiency for large fragments, with up to 122.1-fold enhancement in specific cases [30]

Diagram 2: Prime editing experimental workflow outlining key phases from design to validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of prime editing requires carefully selected reagents and optimization strategies. The following toolkit summarizes critical components and their functions based on current best practices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Prime Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editor Plasmids | PE2, PE3, PE5, PE7 | Express the core editor fusion protein | PE5 recommended for high-efficiency editing with minimal indels |

| pegRNA Expression Systems | epegRNA with evopreQ1 or mpknot motifs | Encode target specificity and edit template | Structured RNA motifs improve stability and efficiency 3-4 fold |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), AAV vectors | Facilitate cellular entry of editing components | Dual AAV systems required for larger editors; SORT LNPs enable organ-specific targeting |

| MMR Inhibitors | MLH1dn | Suppress mismatch repair to enhance edit retention | Critical for achieving high editing efficiency (>60%) |

| Cell Culture Reagents | HEK293T, HCT116, iPSCs | Provide cellular context for editing | iPSCs recommended for disease modeling |

| Analysis Tools | Next-generation sequencing, TIDE | Quantify editing efficiency and specificity | Amplicon sequencing provides most accurate efficiency measurement |

pegRNA Design and Optimization

The pegRNA represents the most critical component for successful prime editing, requiring careful design and stabilization:

- Target Sequence: Standard 20 nt spacer sequence with minimal off-target potential

- Scaffold: Standard sgRNA scaffold compatible with Cas9 nickase

- Reverse Transcriptase Template (RTT): 25-40 nt sequence encoding desired edit with appropriate homologous flanking sequences

- Primer Binding Site (PBS): 10-15 nt complementary to DNA target immediately 3' of nick site

- Stabilization Motifs: Incorporate evopreQ1, mpknot, or G-quadruplex motifs at 3' end to prevent degradation and improve efficiency [1] [2]

For challenging edits, utilize dual-pegRNA systems such as twinPE or EXPERT, which can expand the editable range and enhance efficiency through coordinated editing strategies [30].

DNA Repair Pathways in Prime Editing

Understanding and modulating DNA repair pathways is essential for optimizing prime editing outcomes. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9 systems that rely on double-strand break repair pathways, prime editing primarily engages distinct DNA repair mechanisms.

The prime editing process initiates when the Cas9 nickase creates a single-strand break in the target DNA, exposing a 3'-hydroxyl group that serves as a primer for reverse transcription [28]. The reverse transcriptase then synthesizes a new DNA strand containing the desired edit using the pegRNA template. This creates a DNA heteroduplex with one edited strand and one original unedited strand. Cellular repair machinery then resolves this intermediate structure through flap equilibrium, where the edited 3' flap and unedited 5' flap compete for integration into the genome [28].

The mismatch repair (MMR) pathway represents a significant barrier to efficient prime editing, as it frequently recognizes and reverses the incorporated edits [28]. Advanced prime editors (PE4, PE5) address this limitation by incorporating dominant-negative MLH1 (MLH1dn) to temporarily suppress MMR activity, dramatically improving editing efficiency [15] [2]. Additionally, the use of a second nicking sgRNA in PE3 and PE5 systems encourages the cellular repair machinery to use the edited strand as a template for repairing the complementary strand, further enhancing edit incorporation [1] [15].

Diagram 3: Prime editing mechanism with key pathways including the inhibitory effect of MMR and its modulation by MLH1dn.

Applications in Genetic Disorder Research

Prime editing technologies have demonstrated remarkable potential for correcting diverse genetic mutations associated with human diseases. The technology's ability to install precise edits without double-strand breaks makes it particularly valuable for therapeutic applications where minimizing genomic instability is critical.

In proof-of-concept studies, prime editing has successfully corrected mutations associated with Ducheme muscular dystrophy (DMD) by restoring the reading frame of the dystrophin gene in human cardiomyocytes, achieving up to 50% correction efficiency and corresponding functional improvement [27]. Similarly, prime editing approaches have shown promise for treating chronic granulomatous disease, with the first FDA-approved clinical trial announced in April 2024 [31]. This rapid translation from technology development to clinical application in under five years represents an unprecedented pace in gene therapy development.

The expansion of prime editing tools, including Cas12a-based systems and specialized approaches like EXPERT, has further broadened the therapeutic scope. These systems enable targeting of previously inaccessible genomic regions, including T-rich sequences and areas requiring large fragment modifications up to 100 bp [29] [30]. As delivery technologies continue to advance, particularly lipid nanoparticle formulations and engineered viral vectors, the therapeutic potential of prime editing for addressing the vast landscape of genetic disorders appears increasingly attainable.

The evolution from PE1 to PE7 and the development of Cas12a-based systems represents a remarkable trajectory of innovation in prime editing technology. Each generation has addressed specific limitations, resulting in editors with dramatically improved efficiency, precision, and versatility. The integration of MMR inhibition, pegRNA stabilization strategies, and expanded editing architectures has transformed prime editing from a proof-of-concept technology to a robust platform for genetic engineering.

For researchers and drug development professionals focused on genetic disorders, these advancements offer unprecedented opportunities to develop precise therapeutic interventions without the safety concerns associated with double-strand breaks. As prime editing systems continue to evolve, with ongoing improvements in delivery, efficiency, and targeting range, their impact on genetic medicine is expected to grow substantially. The recent clinical progression of prime editing therapies underscores the translational potential of these technologies and their capacity to address previously untreatable genetic conditions.

Methodology and Therapeutic Applications: From Cell Models to Clinical Trials

The liver is a vital organ responsible for numerous metabolic functions, including the synthesis of most serum proteins. Consequently, it is also the origin of a wide array of inherited genetic disorders, such as hemophilia, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD), phenylketonuria (PKU), and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency [32] [33]. For many of these conditions, orthotopic liver transplantation is the only curative option, a procedure hampered by the limited availability of donor organs, high costs, and the necessity for lifelong immunosuppression [32] [34]. Gene therapy presents a promising alternative, aiming to address the root cause of disease by correcting genetic mutations.

The development of prime editing (PE), a versatile "search-and-replace" genome editing technology, marks a significant advancement for treating genetic disorders. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9, which relies on creating double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs), prime editing uses a fusion of a Cas9 nickase and a reverse transcriptase to directly write new genetic information into a target DNA site directed by a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) [10] [35]. This mechanism avoids the pitfalls of DSBs—such as unintended insertions, deletions, and chromosomal rearrangements—and enables a wider range of precise edits, including all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring donor DNA templates [10] [34] [35].

The success of in vivo prime editing, however, is critically dependent on the delivery vehicle. The liver's unique physiology, particularly its fenestrated endothelium with pores ranging from 100–175 nm, makes it naturally accessible to nanoparticle-based delivery systems [36]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have emerged as the leading non-viral platform for in vivo delivery of nucleic acids, proven by their clinical success in siRNA therapeutics and mRNA vaccines [32] [37]. This combination of a susceptible target organ and a clinically validated delivery system positions LNP-mediated prime editing as a transformative approach for treating inherited liver diseases.

Therapeutic Approaches and Quantitative Outcomes

Lipid nanoparticles can be engineered to deliver various nucleic acid payloads for different therapeutic strategies, from gene silencing to precise gene correction. The table below summarizes key therapeutic approaches and their demonstrated efficacy in preclinical models.

Table 1: Therapeutic Outcomes of LNP-Mediated Nucleic Acid Delivery for Liver Disorders

| Therapeutic Approach | Nucleic Acid Payload | Disease Model | Target Gene / Locus | Editing / Silencing Efficiency | Physiological Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Editing | PE7 mRNA + pegRNA (AAV vector) | PKU (Pahenu2 mice) | Pahenu2 | 20.7% | Blood L-phenylalanine reduced from >1,500 µmol/L to <360 µmol/L (therapeutic threshold) | [38] |

| Prime Editing | PE7 mRNA + synthetic pegRNA (co-delivered in LNP) | PKU (Pahenu2 mice) | Pahenu2 | 8.0% | Blood L-phenylalanine reduced to <360 µmol/L | [38] |

| Gene Knockout (CRISPR-Cas9) | iGeoCas9 RNP | Reporter Mice (Ai9) | tdTomato | 37% (average liver editing) | N/A (Reporter activation) | [39] |

| Gene Knockout (CRISPR-Cas9) | iGeoCas9 RNP | Wild-Type Mice | PCSK9 | 31% | N/A | [39] |

| Gene Silencing (siRNA) | siRNA Cocktail | Mouse HSCs & Hepatocytes | Reln (HSCs) / Ttr (Hepatocytes) | 0-80% (Reln) / >90% (Ttr) | N/A | [36] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: LNP Formulation for Prime Editor mRNA and pegRNA Delivery

This protocol details the co-encapsulation of prime editor mRNA and chemically modified pegRNA into LNPs for in vivo delivery, based on the methodology that successfully treated phenylketonuria in a mouse model [38].

Key Reagents:

- Ionizable lipid (e.g., ALC-0315, SM-102, MC3)

- Helper phospholipid (e.g., DSPC)

- Cholesterol

- PEG-lipid (e.g., DMG-PEG2000)

- Prime editor mRNA (e.g., PE7, modified with 5' cap and poly-A tail)

- Chemically modified pegRNA (tevopreQ1 structure with 3' pseudo-knots for stability)

Procedure:

- Lipid Mixture Preparation: Prepare an ethanol solution containing the ionizable lipid, DSPC, cholesterol, and PEG-lipid at a molar ratio of 50:10:38.5:1.5 [40] [37].

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Dilute the PE7 mRNA and synthetic pegRNA in an acidic aqueous buffer (e.g., sodium acetate, pH 4.0). A weight ratio of approximately 10:1 (lipids:RNA) is typical [40].

- Nanoparticle Formation: Use a microfluidics device to rapidly mix the ethanolic lipid solution with the aqueous RNA solution at a controlled flow rate and volume ratio (typically 3:1, aqueous:ethanol). This instantiates the formation of RNA-encapsulated LNPs [40] [37].

- Buffer Exchange and Purification: Dialyze the raw LNP formulation against a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution at pH 7.4 to remove residual ethanol and adjust the pH to physiological conditions. This step is critical for stability.

- Quality Control: Characterize the final LNP product by measuring:

- Particle Size and Dispersity (PDI): Using dynamic light scattering. Target diameter should be <100 nm with a PDI <0.1 for optimal liver transit [40] [36].

- RNA Encapsulation Efficiency: Using a dye exclusion assay (e.g., RiboGreen). Target >90% encapsulation.

- Zeta Potential: As an indicator of colloidal stability.