PROLSQ in Structural Biology: Foundations, Evolution, and Modern Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive examination of PROLSQ, a foundational method for protein structure refinement using stereochemical restraint libraries.

PROLSQ in Structural Biology: Foundations, Evolution, and Modern Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of PROLSQ, a foundational method for protein structure refinement using stereochemical restraint libraries. It explores the historical context and core principles that established PROLSQ's role in macromolecular crystallography, detailing its algorithmic approach for minimizing crystallographic R-factors while preserving ideal geometry. The content addresses common challenges and limitations, contrasting PROLSQ's methods with modern refinement protocols like Rosetta, CNS, and molecular dynamics simulations. Furthermore, it covers validation techniques rooted in PROLSQ's stereochemical libraries and discusses the method's enduring influence on contemporary tools in structural biology and structure-based drug design, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a thorough understanding of its legacy and practical relevance.

The Bedrock of Biomolecular Refinement: Unpacking PROLSQ's Historical Significance and Core Principles

PROLSQ stands as a foundational computer program in the history of structural biology, representing a pivotal methodological advance for the refinement of crystallographic structures. Developed in the context of macromolecular crystallography, PROLSQ implemented the paradigm of restrained refinement, which elegantly balanced experimental X-ray diffraction data with prior knowledge of molecular geometry. Before its development, crystallographic refinement struggled with the challenge of insufficient data in relation to the number of parameters to be determined, particularly for biological macromolecules. This limitation often resulted in chemically unreasonable models despite acceptable agreement with diffraction data. PROLSQ addressed this fundamental problem by incorporating geometric restraints—mathematical functions that preserved reasonable bond lengths, angles, and other stereochemical parameters during the refinement process. The program's parameters were derived from the Cambridge Structural Database, a comprehensive repository of small-molecule crystal structures, which provided accurate target values for ideal molecular geometry [1].

The significance of PROLSQ's approach extended beyond its immediate computational methodology. By establishing a framework that integrated experimental data with chemical knowledge, it created a more robust and reliable refinement process. This was particularly crucial for the emerging field of protein crystallography, where the complexity of macromolecules often pushed against the limits of available experimental data. The restrained refinement philosophy pioneered by PROLSQ established a standard that would influence subsequent generations of refinement software. The program's underlying force field parameters, particularly those related to non-bonded interactions, were derived from the CSDX force field and calculated using the PROLSQ program itself [1]. These parameters eventually became reference standards for structure validation programs such as WHATIF and PROCHECK, demonstrating the enduring legacy of PROLSQ's foundational work in defining molecular geometry expectations for structural biology [1].

Technical Foundations of the PROLSQ Method

Core Algorithmic Approach

The PROLSQ program operated on the principle of minimizing a combined target function that incorporated both experimental diffraction data and ideal molecular geometry. This objective function can be conceptually represented as Φ = wX-rayΦX-ray + wgeomΦgeom, where ΦX-ray measured the agreement between calculated and observed structure factors, while Φgeom quantified the deviation from ideal stereochemical parameters. The weights wX-ray and wgeom balanced the contributions of these potentially competing terms, a critical aspect of the refinement process. The geometric term Φgeom itself comprised multiple components: Φgeom = Φbonds + Φangles + Φplanarity + Φnon-bonded, each representing different aspects of molecular geometry that were restrained to ideal values based on high-quality small-molecule structures [1].

The mathematical implementation in PROLSQ utilized least-squares minimization techniques to iteratively adjust atomic parameters until the objective function reached a minimum. This approach represented a significant computational challenge at the time of its development, requiring efficient algorithms to handle the thousands of parameters defining atomic positions and thermal motions. The program maintained separate dictionaries of ideal values for different chemical contexts, allowing it to apply appropriate restraints for protein, DNA, and ligand components. This attention to chemical specificity was particularly important in the refinement of protein-nucleic acid complexes and drug-DNA structures, where proper geometric restraints were essential for producing accurate models [2].

Comparison with Contemporary Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Refinement Programs Including PROLSQ

| Program | Refinement Method | Key Features | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROLSQ | Restrained least-squares | Stereochemical restraints based on small-molecule geometry | Macromolecular refinement |

| NUCLSQ | Least-squares | Nucleic acid specific restraints | DNA & RNA structures |

| X-PLOR | Simulated annealing | Molecular dynamics approach | Protein & complex structures |

| SHELXL93 | Least-squares | Full-matrix least-squares refinement | Small molecules & macromolecules |

When compared with contemporary refinement methods, PROLSQ occupied an important niche in the computational ecosystem of structural biology. In a comprehensive comparative study of DNA-drug refinement using the d(TGATCA)-nogalamycin complex, PROLSQ demonstrated its capabilities alongside other available programs [2]. The investigation revealed that although final R values differed somewhat between refinement methods—with PROLSQ achieving 22.8% compared to 21.2% for NUCLSQ and 24.4% for X-PLOR—the root-mean-square deviations between the final models were remarkably small [2]. This finding suggested that the specific refinement program used had minimal impact on the final model geometry, provided that proper restraint dictionaries and protocols were employed.

The comparative analysis further demonstrated that PROLSQ could successfully handle the challenges of nucleic acid refinement, a particularly demanding task due to the conformational flexibility of DNA and RNA backbones. Importantly, the study concluded that "neither the dictionary nor the refinement program leave an imprint on the final fully refined complex," affirming the robustness of the restrained refinement approach that PROLSQ exemplified [2]. The helical parameters and backbone conformation, including sugar-puckering modes, were not significantly influenced by the choice of refinement procedure, highlighting how the field had converged on effective protocols for maintaining reasonable molecular geometry during refinement [2].

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standard Refinement Protocol Using PROLSQ

The typical PROLSQ refinement workflow followed a series of methodical steps designed to progressively improve the atomic model while maintaining stereochemical soundness. A representative protocol for refining a DNA-drug complex structure is outlined below, based on published methodologies [2]:

Initial Model Preparation: Begin with a preliminary structural model derived from molecular replacement or other phasing methods. Ensure proper assignment of atom types and connectivity.

Dictionary Generation: Prepare restraint dictionaries for all unique chemical components, including standard nucleic acid or amino acid residues and any non-standard ligands or modifications.

Initial Refinement Cycle: Perform an initial round of refinement with higher weights on geometric restraints to regularize the model before stronger integration of experimental data.

Cyclical Refinement: Iterate through multiple cycles of:

- Coordinate refinement with PROLSQ's least-squares algorithm

- Manual inspection of electron density maps (2Fo-Fc and Fo-Fc)

- Manual model rebuilding in poorly fitting regions

- Adjustment of restraint weights based on model behavior

Solvent Modeling: Introduce ordered water molecules into peaks of positive difference density that exhibit appropriate geometry and hydrogen-bonding potential.

Validation: Assess final model quality using geometric validation tools and agreement with experimental data.

This protocol emphasized the iterative nature of crystallographic refinement, where computational optimization alternated with manual model inspection and adjustment. The PROLSQ program excelled within this framework by providing stable refinement that maintained reasonable geometry even when experimental data was limited or ambiguous.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents in PROLSQ-Based Crystallographic Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function in Crystallography | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Reagents | Promote crystal formation | Precipitants (PEG, salts), buffers, additives |

| Heavy Atom Derivatives | Experimental phasing | Mercury, platinum, samarium compounds |

| Cryoprotectants | Preserve crystals during data collection | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, various oils |

| Restraint Databases | Define ideal geometry for refinement | Cambridge Structural Database, CSDX parameters |

The application of PROLSQ and related refinement methods depended critically on the quality of the underlying experimental system. In the seminal DNA-drug refinement study [2], the d(TGATCA) oligonucleotide was complexed with the anticancer agent nogalamycin, creating a well-defined crystalline system that enabled rigorous comparison of refinement methods. The DNA sequence was selected to provide specific binding sites for the drug molecule, while the crystal growth conditions were optimized to produce high-diffraction-quality crystals. The transition from room-temperature to low-temperature (120 K) data collection improved the resolution from 1.8 Å to 1.4 Å, providing an excellent dataset for method comparison [2].

The study also highlighted the importance of solvent modeling in crystallographic refinement. Although the number of water molecules identified varied from 62 in X-PLOR refinements to 86 in NUCLSQ refinements, the first hydration sphere around the DNA-drug complex was "well conserved in all four models" [2]. This consistency in locating structurally significant water molecules demonstrated that despite differences in implementation, all refinement programs captured the essential features of hydration when provided with high-quality experimental data.

Impact and Evolution Beyond PROLSQ

Influence on Modern Refinement Software

The conceptual framework established by PROLSQ has profoundly influenced subsequent generations of crystallographic refinement software. The fundamental principle of restrained refinement remains central to modern programs, though implementation details have evolved significantly. The transition from PROLSQ to more advanced refinement packages can be traced through several key developments:

The PHENIX software platform represents one of the most direct evolutionary descendants of the PROLSQ philosophy, incorporating enhanced restraint models, more sophisticated optimization algorithms, and a broader range of experimental constraints [3]. Phenix.refine includes advanced features such as TLS parameterization for atomic displacement parameters, automatic solvent building, and comprehensive validation metrics—all extending the basic restrained refinement concept that PROLSQ pioneered [3]. The recent integration of the Amber molecular dynamics force field into Phenix demonstrates how modern refinement has expanded beyond geometric restraints to include more physically realistic energy potentials [4]. This "Amber refinement target" shows "substantially improved model quality" particularly for "Ramachandran and rotamer scores," "clashscores," and "MolProbity scores," representing a significant advance over traditional geometry restraints [4].

Similarly, the CNS (Crystallography and NMR System) software incorporated explicit water refinement (CNSw), which substantially improved the quality of both crystallographic and NMR-derived structures [1]. The RECOORD database project, which re-refined NMR structures using a consistent CNS water refinement protocol, exemplifies the ongoing effort to standardize refinement methods across the structural biology community [1].

Applications in Structure-Based Drug Discovery

The legacy of PROLSQ extends directly into modern drug discovery pipelines, where accurate structural models are critical for rational drug design. The transition from early restrained refinement methods to contemporary approaches has enhanced the reliability of protein-ligand complex structures, which form the basis for structure-based drug design (SBDD) [5]. As noted in recent evaluations, "crystal structures of target macromolecules and macromolecule–ligand complexes is critical at all stages" of drug discovery [5].

However, this application also highlights the limitations of early refinement methods and the need for continuous improvement. Recent validation studies have revealed that "a considerable number of functional ligands reported in the PDB were not supported by electron density maps," indicating instances where refinement may have been misled by model bias or insufficient data [5]. This observation underscores the importance of proper refinement practices and critical validation—principles that were central to the PROLSQ methodology from its inception.

The development of projects such as PDB-REDO, which systematically re-refines structures using modern methods, addresses the need for consistent quality in the structural data used for drug design [5]. Although automatic re-refinement has limitations, it represents an important step toward maintaining the utility of the structural archive for drug discovery applications.

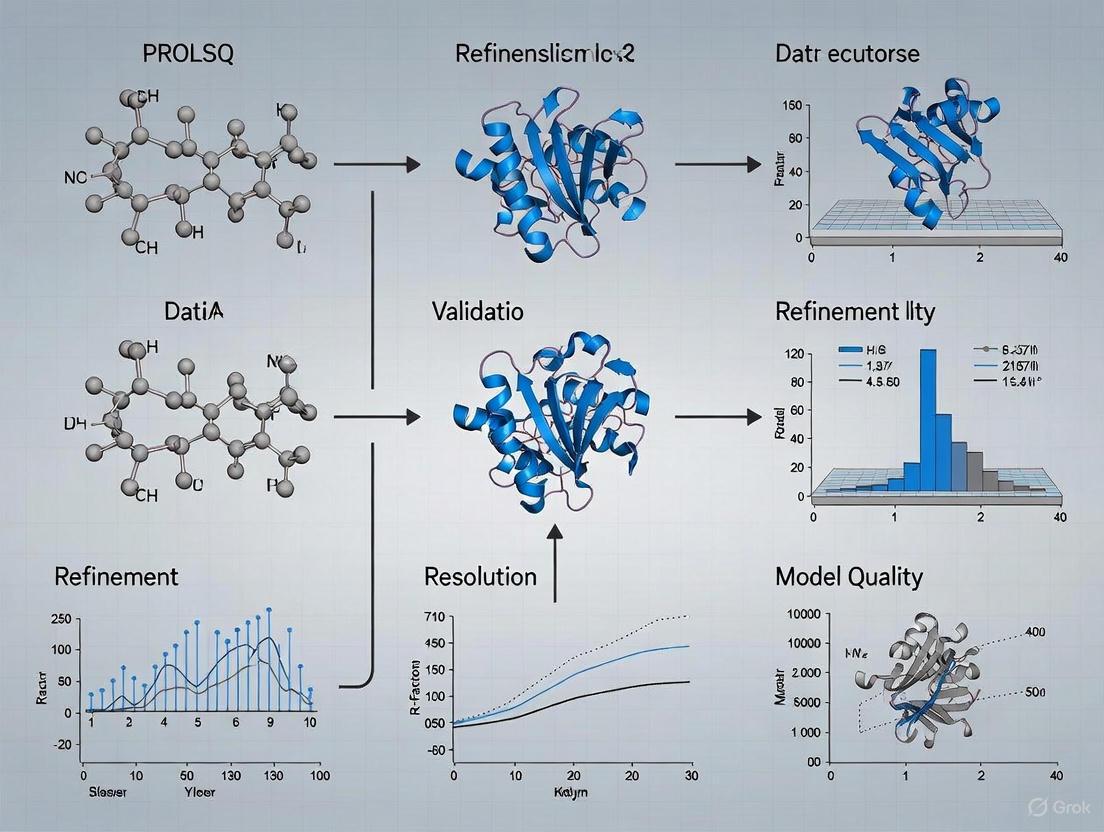

Conceptual Workflow and Modern Legacy

The transition from early refinement tools like PROLSQ to modern methodologies represents both conceptual continuity and technical evolution. The following diagram illustrates this progression and the expanding scope of crystallographic refinement:

This conceptual workflow illustrates how PROLSQ established the paradigm of restrained refinement that continues to underpin modern methods. The fundamental innovation of balancing experimental data with prior chemical knowledge has proven enduring, even as computational approaches have grown increasingly sophisticated. Contemporary methods like those implemented in Phenix and other packages have expanded on this foundation through molecular dynamics approaches, maximum-likelihood targets, and more sophisticated parameterization of disorder and motion [3] [4].

The legacy of PROLSQ is particularly evident in the ongoing emphasis on hydrogen-bonding networks as critical determinants of model quality. Recent investigations have demonstrated that "correct identification of hydrogen bonds should be a critical goal of NMR structure refinement," with improved hydrogen-bonding leading directly to better molecular replacement performance [1]. This focus on chemically realistic interactions represents a direct extension of PROLSQ's original mission to maintain stereochemical rationality during refinement.

PROLSQ represents a landmark development in structural biology that established the restrained refinement paradigm now fundamental to macromolecular crystallography. By integrating stereochemical restraints from small-molecule structures with experimental diffraction data, PROLSQ addressed the critical challenge of parameter insufficiency that had limited earlier refinement methods. The program's influence extends far beyond its immediate utility, having established conceptual frameworks and technical approaches that continue to guide modern refinement software. The evolution from PROLSQ to contemporary methods demonstrates how core principles of stereochemical soundness, proper weighting of experimental and geometric terms, and iterative model improvement remain essential to producing accurate structural models.

The enduring impact of PROLSQ's innovations is particularly evident in modern structural genomics initiatives and drug discovery applications, where high-quality models are essential for functional interpretation and inhibitor design. As structural biology continues to expand into new areas such as cryo-electron microscopy and integrative modeling, the fundamental principles established by PROLSQ continue to provide guidance for balancing experimental data with prior chemical knowledge. The program's legacy serves as a reminder that advances in structural biology depend not only on improved experimental data but also on the development of computational methods that properly interpret that data within the constraints of chemical rationality.

In structural biology, the accuracy of molecular models derived from experimental data like X-ray crystallography is paramount. Structure refinement is the process of adjusting an atomic model to best fit the experimental data, a core component of which involves minimizing the discrepancy between the model's predicted data and the actual observed data. The PROLSQ (PROtein Least Squares Refinement) algorithm represents a foundational approach in this field, utilizing a weighted least-squares method to optimize the agreement with X-ray diffraction data while maintaining ideal stereochemical geometry [1]. The core challenge is to balance the fit to the experimental data with the need for the model to adhere to known physical and chemical constraints. This document details the modern interpretation and application of these principles, providing application notes and protocols for researchers engaged in high-precision structure determination for drug development.

Core Algorithm and Computational Framework

The PROLSQ Algorithm and Its Evolution

The PROLSQ algorithm refines a protein structure by minimizing a target function, E, that consists of two key components [1]:

- Experimental Discrepancy Term (X-ray Residual): This term, often a least-squares function, quantifies the difference between the structure factor amplitudes calculated from the atomic model (Fc) and those observed experimentally (Fo).

- Geometric Restraint Term: This term ensures the model remains chemically plausible by penalizing deviations from ideal bond lengths, bond angles, and other stereochemical parameters.

The minimization function can be represented as: E = Σ w(|Fo| - |Fc|)² + Σ λr(di - dideal)² Where:

- w is a weight for the experimental term.

- Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

- λr is a weight for a specific geometric restraint r.

- di and dideal are the current and ideal values for a geometric parameter (e.g., a bond length).

The parameters for these ideal values and force constants were derived from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSFD), establishing a probabilistic foundation for the refinement that was both rigorous and physically meaningful [1]. This integration of high-quality reference data was a key advancement over its predecessors. PROLSQ's parameters later became the reference for structure validation programs like PROCHECK and WHATIF, underlining its lasting impact on the field [1].

Modern Extensions: Integrating Bayesian Inference and Active Learning

While PROLSQ provides a deterministic framework, modern computational methods have expanded its principles. Bayesian Experimental Design (BED) offers a probabilistic framework for actively learning and correcting for model discrepancy [6]. In this context, "model discrepancy" refers to systematic errors arising from an incomplete or inaccurate physical model.

A hybrid framework can be employed that integrates sequential BED with machine learning:

- Formulate the Problem: The true system dynamics are unknown but approximated by a physics-based model,

𝒢(𝐮; 𝜽𝒢). - Characterize Discrepancy: The discrepancy between the true system and the model is represented by an additive term, often parameterized by a neural network,

NN(𝐮; 𝜽NN), leading to a corrected model [6]:∂𝐮/∂t = 𝒢(𝐮; 𝜽𝒢) + NN(𝐮; 𝜽NN) - Active Learning Loop: A sequential BED process iteratively selects the most informative new experiments to perform. The data from these experiments are then used to update the parameters of the neural network discrepancy term, gradually improving the model's accuracy [6].

This approach avoids the computational intractability of performing full Bayesian inference on the high-dimensional parameters of a neural network, instead using optimization to update the discrepancy term based on optimally selected data.

Workflow for Discrepancy-Aware Structure Refinement

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for structure refinement that incorporates active learning of model discrepancies, connecting the classical PROLSQ approach with modern machine learning techniques.

Application Notes: A Case Study on HSPC034 Protein

Protocol: Structure Refinement with Discrepancy Mitigation

The following protocol is adapted from studies on the human protein HSPC034, whose structure was determined by both NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography, providing a robust benchmark for refinement methods [1].

Objective: To refine an initial atomic model of a protein against X-ray diffraction data, minimizing the discrepancy between Fo and Fc while maintaining stereochemical quality.

Materials and Reagents: Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Structure Refinement

| Reagent / Software | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Diffraction Dataset | Raw experimental data containing structure factor amplitudes (Fo) and phases (for molecular replacement). | The resolution should be sufficient for the intended research question (e.g., 1.5-2.5 Å for drug binding site analysis). |

| Initial Atomic Model | A starting model, often from molecular replacement or homology modeling. | For HSPC034, the model was derived from a combination of SeMet and Sm derivative data [1]. |

| PROLSQ or CNS/CNX | Refinement software implementing least-squares minimization and geometric restraints. | Modern successors like CNS (Crystallography and NMR System) with explicit water refinement (CNSw) are widely used [1]. |

| Rosetta | A modeling suite using a fragment-based approach and all-atom energy function for refinement. | Can be used for post-refinement to improve model quality, particularly hydrogen bonding networks [1]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Restraints | Additional distance and angle restraints based on identified hydrogen bonds. | Derived from programs like ProQ or analysis of Rosetta-refined models to guide the refinement force field [1]. |

Procedure:

- Initial Refinement Cycle:

- Input the initial model and processed diffraction data into the refinement program (e.g., CNS).

- Perform a cycle of least-squares refinement (following the PROLSQ paradigm) to minimize the residual

Σ w(|F*o*| - |F*c*|)². - The geometric restraint term (

Σ λ*r*(d*i* - d*ideal*)²) is applied concurrently to maintain bond lengths and angles within ideal ranges.

Model Discrepancy Assessment and Correction:

- Examine the difference Fourier map (

F*o* - F*c*) to identify regions of high residual discrepancy, indicating potential model errors. - For regions with persistent discrepancy, consider applying a correction term. In a modern framework, this could be informed by a pre-trained neural network that suggests local atomic shifts.

- Examine the difference Fourier map (

Iterative Model Building and Refinement:

- Manually or automatically adjust the atomic model in visualization software (e.g., Coot) to fit the electron density and address major discrepancies.

- Repeat the refinement cycles (steps 1-2) until the R-factor and R-free values converge and no significant positive density remains in the difference map.

Advanced Refinement with Rosetta (Optional):

- To further improve model quality, particularly the hydrogen-bonding network, subject the refined model to Rosetta refinement [1].

- Rosetta uses a different force field and sampling algorithm, which can find alternative low-energy conformations that are equally consistent with the experimental data but have superior geometry.

Validation:

- Validate the final model using tools like PROCHECK and MolProbity to ensure stereochemical quality.

- Use a neural-network-based predictor like ProQ to evaluate the global quality of the model. A LGscore > 1.5 and MaxSub > 0.1 typically indicate a "correct" model, while scores above 3 and 0.5 indicate a "good" model [7].

Quantitative Metrics and Validation

The success of refinement is quantitatively assessed using several key metrics, as demonstrated in the HSPC034 study [1]. The table below summarizes these metrics and their implications for model quality.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Structure Refinement Quality Assessment

| Metric | Description | Target Value / Implication | HSPC034 (X-ray) Example [1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-factor / R-work | Measures the agreement between Fo and Fc for the data used in refinement. | Lower is better. A decrease of 5-10% from initial model is typical. | Not explicitly stated, but the model was of high quality. |

| R-free | Measures agreement for a subset of data (5-10%) excluded from refinement. Prevents overfitting. | Should be close to R-factor (within ~0.05). A large gap suggests overfitting. | Difference to R-factor was 2.9%, indicating well-refined model. |

| RMSD (Bond Lengths) | Root Mean Square Deviation from ideal bond lengths. | Should be < 0.02 Å. | The model was in good agreement with geometric parameters. |

| RMSD (Bond Angles) | Root Mean Square Deviation from ideal bond angles. | Should be < 2.0°. | The model was in good agreement with geometric parameters. |

| LGscore | A neural-network predicted quality score (-log of a P-value) [7]. | > 1.5 (Correct), > 3 (Good), > 5 (Very Good). | Used for evaluating NMR models; applicable for final model validation. |

| MaxSub | A neural-network predicted quality score (0-1) for model significance [7]. | > 0.1 (Correct), > 0.5 (Good), > 0.8 (Very Good). | Used for evaluating NMR models; applicable for final model validation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Refinement

A successful structure refinement project relies on a combination of software tools and data resources. The following table details the essential components of a modern refinement pipeline.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Structural Biologists

| Category | Item | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Software | CNS / PHENIX / Refmac | Modern refinement packages that implement the PROLSQ-like least-squares minimization with robust restraint handling. |

| Software | Rosetta | Provides an alternative force field and sampling protocol for high-resolution refinement and improving hydrogen-bond networks [1]. |

| Software | ProQ | A neural-network-based predictor used to evaluate the quality of a protein model, providing LGscore and MaxSub metrics [7]. |

| Data | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | The source of high-quality reference data for ideal bond lengths and angles, forming the foundation of the PROLSQ force field [1]. |

| Data | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for depositing and retrieving final refined structures and experimental data. |

| Hardware | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Necessary for computationally intensive tasks like Rosetta refinement, molecular dynamics simulations, and processing large datasets. |

Visualization of the Refinement Feedback Loop

The core of discrepancy minimization is an iterative feedback loop. The following diagram details this process, showing how quality metrics directly inform the decision to perform further refinement or to utilize active learning for acquiring new data.

The Critical Role of Stereochemical Restraint Libraries from the Cambridge Structural Database

Stereochemical restraint libraries are foundational to the determination of accurate and reliable three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules. These libraries provide the target values for bond lengths, bond angles, and other geometric parameters that are used as restraints during the refinement of structures determined by X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. The vast majority of macromolecular refinement procedures utilize standard stereochemical information because the experimental data alone are typically insufficient to define all atomic parameters without introducing unrealistic geometry [8]. The Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), a repository of over 800,000 accurate small-molecule crystal structures, serves as the primary source for deriving these critical parameters [8]. The rules of chemical bonding established from the CSD must apply equally to macromolecular structures, ensuring that refined models are both chemically sensible and structurally accurate. This application note details the use of these libraries, with a specific focus on their implementation within the context of the PROLSQ refinement program and its legacy.

CSD-Derived Libraries: The Gold Standard for Refinement

The derivation of stereochemical restraint libraries from the CSD represents a significant advancement over earlier, less precise libraries. The most widely adopted set of parameters was compiled by Engh and Huber, creating the CSD-X library [9]. This library was developed through careful analysis of the CSD and provided a carefully selected restraint set that quickly became the gold standard for macromolecular refinement [8] [9].

Table 1: Key Features of the CSD-X Restraint Library

| Feature | Description | Impact on Refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Data | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [8] | Parameters derived from experimental data on small organic and organometallic molecules, ensuring chemical accuracy. |

| Bond Length Precision | Root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) target of ~0.02 Å [8] | Prevents over-idealization while maintaining geometric reasonableness. Values significantly higher may indicate model problems. |

| Bond Angle Precision | Root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) target between 0.5° and 2.0° [8] | Ensures proper hybridization and bonding geometry across the macromolecule. |

| Replacement of Older Libraries | Superseded the param19x restraints used in X-PLOR [9] | Yielded a ~10% improvement in agreement with restraints without degrading the fit to experimental data [9]. |

The CSD-X library is utilized by nearly all major refinement programs, such as CNS, SHELXL, REFMAC5, and PHENIX [8]. Its parameters also form the reference standard for structure validation programs like WHATIF and PROCHECK, establishing uniformity in how structures are refined and evaluated across the structural biology community [1]. The library has been subsequently updated to account for effects such as secondary structure influences and protonation-state variations [8].

PROLSQ and the Implementation of Restraints

The refinement program PROLSQ was a pioneering reciprocal-space least-squares refinement program that explicitly relied on stereochemical restraints derived from small-molecule structures [8] [1]. Its functioning is based on minimizing a function that combines the fit to the X-ray diffraction data (the crystallographic residual) and the deviation of the model from ideal stereochemistry [8].

The PROLSQ refinement process requires a pre-defined dictionary of ideal groups. The program PROTIN prepares the necessary input file for PROLSQ, which includes these stereochemical restraints [10]. For novel ligands or cofactors not present in the standard dictionary, a procedure involving the program MOLBLD can be used. MOLBLD generates the required Cartesian coordinates using specified bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles, which can then be incorporated into the PROLSQ dictionary via the CONEXN procedure [10].

Table 2: Core Components of the PROLSQ Refinement System

| Component | Function | Role in Stereochemical Restraint |

|---|---|---|

| PROLSQ | Performs reciprocal-space least-squares refinement of the atomic model [1]. | Minimizes a combined function of the crystallographic residual and deviations from ideal geometry. |

| PROTIN | Prepares the input file for PROLSQ [10]. | Incorporates the dictionary of ideal groups and their associated stereochemical restraints. |

| CSD-Derived Library | Provides the "ideal" bond lengths, angles, and other parameters. | Serves as the target for geometric restraints during refinement, ensuring chemical accuracy. |

| MOLBLD/CONEXN | Generates coordinates and adds new groups to the ideal group dictionary [10]. | Extends the restraint system to novel chemical entities outside the standard amino acids/nucleic acids. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the flow of information and the role of the CSD-derived library in a typical structure refinement process.

Advanced Applications and Protocols

Protocol: Structure Refinement with PROLSQ and CSD-Derived Restraints

This protocol outlines the key steps for refining a macromolecular structure using the PROLSQ system with a CSD-derived restraint library.

- Initial Model Preparation: Obtain an initial atomic model from molecular replacement, experimental phasing (SAD/MAD), or other methods.

- Restraint Library Selection: The CSD-X library [8] [9] is typically selected as the source of ideal bond lengths and angles. Its parameters are embedded within the PROLSQ ideal group dictionary.

- Restraint File Generation: Use the program PROTIN to process the atomic coordinates and generate the input file for PROLSQ. This step matches atoms in the model to their corresponding ideal parameters in the dictionary [10].

- Refinement Cycle Execution: Run PROLSQ refinement. The program performs least-squares minimization of the function:

Total Cost = Σ|Fobs - Fcalc|² + λ * Σ(Geometry - Geometry_ideal)², where the second term represents the stereochemical restraints derived from the CSD [8]. - Model Rebuilding and Validation: Between cycles of refinement, manually inspect and rebuild the model based on electron density maps. Use validation tools to check:

- Ramachandran plot: Ensure >98% of φ/ψ angles are in favored regions [8].

- Bond length and angle rmsd: Verify bond rmsd is ~0.02 Å and angle rmsd is between 0.5° and 2.0° [8].

- Peptide planarity: Check that ω angles are close to 180° (trans) or 0° (cis), with deviations >20° being highly suspicious unless supported by ultrahigh-resolution data [8].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3-5 until the model converges, showing a good fit to both the experimental data and ideal stereochemistry.

Conformation-Dependent Libraries (CDL): An Evolution of the Paradigm

A significant evolution beyond the single-value restraints of the CSD-X library is the development of conformation-dependent libraries (CDL). These libraries recognize that ideal bond lengths and angles are not fixed but vary systematically as a function of the protein backbone conformation (φ/ψ angles) [9].

Tests refining protein structures using a CDL demonstrated a much better agreement with library values for bond angles compared to the CSD-X library, with little to no change in the R values [9]. For example, the N—Cα—C bond angle was found to vary over a range of 6.5° depending on conformation [9]. This advancement suggests that future refinement software that incorporates CDLs can produce models with even better ideal geometry.

The Role in NMR Structure Refinement

Stereochemical restraints from the CSD are equally critical in NMR structure determination. Due to the sparseness of NMR-derived experimental restraints, the force field used for refinement has a large impact on final model quality [1]. The PARALLHDG force field used in programs like CNS and XPLOR-NIH incorporates covalent parameters based on the CSD-X force field [1]. Furthermore, the RECOORD database project re-refined numerous PDB NMR structures using a uniform protocol (CNS with explicit water) and the CSD-X parameters, highlighting the ongoing importance of these standardized restraints for ensuring the quality and comparability of NMR models [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Item Name | Type/Brief Description | Critical Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Database of small-molecule crystal structures. | The ultimate source of experimental data for deriving accurate bond length and angle parameters for restraint libraries [8] [9]. |

| CSD-X Restraint Library | Stereochemical library derived from the CSD. | Provides the target values and standard deviations for bond lengths and angles used during refinement in programs like PROLSQ, CNS, and PHENIX [8] [1]. |

| PROLSQ | Reciprocal-space least-squares refinement program. | A foundational refinement program that utilizes stereochemical restraints to optimize a model against X-ray data [8] [10]. |

| PROTIN | Input preparation program for PROLSQ. | Generates the restraint file for PROLSQ by applying the ideal group dictionary to the atomic model [10]. |

| CNS (Crystallography & NMR System) | Multipurpose structure determination software. | A successor to PROLSQ/X-PLOR that uses the CSD-derived Engh & Huber parameters for refinement and NMR structure calculation [8] [11]. |

| Conformation-Dependent Library (CDL) | Advanced restraint library. | Provides backbone conformation-dependent target values for bond lengths and angles, enabling more accurate and realistic refinement [9]. |

| MOLBLD | Coordinate generation program. | Builds 3D coordinates for novel chemical groups from bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals, facilitating their addition to the PROLSQ dictionary [10]. |

The PROLSQ (PROtein Least SQuares) refinement program, introduced by Konnert and Hendrickson in 1980, established a foundational framework for macromolecular structure refinement that continues to influence structural biology. By incorporating prior chemical knowledge as restrained conditions into crystallographic refinement, PROLSQ addressed the critical challenge of preserving geometric integrity when experimental data alone were insufficient to define atomic parameters completely. This application note examines PROLSQ's methodological underpinnings, its establishment of key quality metrics, and its enduring legacy in modern structural biology and drug discovery. We detail specific protocols for implementing PROLSQ-style refinement and demonstrate how its quality assessment parameters remain relevant for contemporary structure-based drug development.

Macromolecular model quality is paramount in structural biology, particularly in drug discovery applications where small variations in atomic coordinates can significantly impact downstream analyses such as virtual screening and binding site characterization [12]. Before PROLSQ, macromolecular refinement struggled with balancing the fit to experimental data against the maintenance of chemically reasonable geometries. The program's innovative approach applied restrained least-squares refinement, incorporating known chemical properties as subsidiary conditions to guide the refinement process toward physically realistic models [13].

The theoretical foundation of PROLSQ aligns with Bayesian statistical principles, where prior knowledge is formally incorporated into data analysis. In structural biology, this prior knowledge encompasses the relative invariance of fundamental chemical properties including bond lengths, bond angles, chiral volumes, and planar groups [13]. PROLSQ operationalized this approach by establishing specific target values and tolerance limits for these geometric parameters, creating a systematic framework for evaluating and maintaining model quality during refinement.

PROLSQ's development represented a significant advancement over earlier unrestrained methods, enabling more reliable structure determination even at medium to low resolutions where the experimental data alone were insufficient to define all atomic parameters. The quality metrics it established provided researchers with standardized benchmarks for assessing model validity, creating a common language for structural biologists to evaluate and communicate the reliability of their macromolecular models.

PROLSQ's Quality Metric Framework

Core Geometric Restraints

PROLSQ introduced a comprehensive set of geometric restraints derived from small molecule crystallographic data, establishing reference values for ideal bond lengths and angles that reflected chemical expectations. These parameters provided the prior chemical knowledge necessary to guide macromolecular refinement while maintaining reasonable geometry [13]. The program implemented a sophisticated weighting scheme that balanced the relative influence of experimental data versus geometric restraints, allowing for adaptive refinement based on data quality and resolution.

The key quality metrics established by PROLSQ included:

- Bond length deviations: Root-mean-square (RMS) differences between model bond lengths and ideal values

- Bond angle deviations: RMS differences between model bond angles and ideal values

- Chiral volume restraints: Maintenance of proper tetrahedral geometry at chiral centers

- Planar group restraints: Enforcement of planarity in aromatic rings and peptide bonds

- Van der Waals contacts: Prevention of steric clashes through repulsive potential terms

Quantitative Quality Assessment

The implementation of these metrics in PROLSQ enabled quantitative assessment of model quality, as demonstrated in its application to the refinement of crambin at 0.83 Å resolution [14]. This high-resolution refinement allowed detailed comparison between PROLSQ's restrained least-squares approach and full-matrix least-squares refinement, validating PROLSQ's effectiveness in maintaining geometry while fitting experimental data.

Table 1: PROLSQ Quality Metrics as Validated in Crambin Refinement

| Quality Parameter | PROLSQ Implementation | Impact on Model Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Bond length RMSD | Reference to small molecule standards | Ensured chemically accurate covalent geometry |

| Bond angle RMSD | Angular restraints based on chemical environment | Maintained proper hybridization and stereochemistry |

| Chiral volume restraints | Enforcement of tetrahedral geometry | Preserved correct stereochemistry at chiral centers |

| Planarity restraints | Enforcement of group coplanarity | Maintained conjugation in aromatic systems and peptide bonds |

| Van der Waals contacts | Repulsive potential with energy minima at optimal contact distances | Prevented steric clashes and overcrowded atoms |

PROLSQ Refinement Protocol

Workflow Implementation

The PROLSQ refinement protocol follows a systematic workflow that iteratively improves model coordinates while monitoring quality metrics. The diagram below illustrates this refinement process:

Step-by-Step Protocol

Based on the original PROLSQ implementation and its subsequent adaptations [14], the following protocol details the key steps for macromolecular refinement:

Step 1: Initial Setup and Parameterization

- Prepare initial atomic coordinates from model building or molecular replacement

- Acquire geometric restraint parameters (bond lengths, angles, etc.) from the PROLSQ force field

- Prepare experimental structure factor amplitudes (Fobs)

Step 2: Structure Factor Calculation

- Compute structure factors (Fcalc) from the current atomic model

- Derive phases from the current model for use in subsequent electron density calculation

Step 3: Residual Map Calculation

- Compute difference Fourier maps (Fobs - Fcalc) to identify areas requiring model adjustment

- Analyze map quality and identify regions of poor fit to experimental data

Step 4: Coordinate Refinement Cycle

- Adjust atomic coordinates to minimize the residual (Fobs - Fcalc) while satisfying geometric restraints

- Apply damping factors to prevent excessive coordinate shifts in each cycle

- Monitor the R-factor as an indicator of agreement with experimental data

Step 5: Geometric Quality Monitoring

- Calculate RMS deviations from ideal bond lengths and angles

- Check for steric clashes and chiral center violations

- Verify planarity of aromatic groups and peptide bonds

Step 6: Convergence Assessment

- Evaluate improvement in R-factor and geometric quality metrics

- Repeat cycles until convergence criteria are met (typically <0.1% change in R-factor)

Step 7: Validation and Analysis

- Perform comprehensive validation of the final model against all geometric restraints

- Generate final quality reports including Ramachandran analysis and rotamer distributions

PROLSQ's Influence on Modern Refinement Methods

Evolution to Contemporary Refinement Systems

PROLSQ's fundamental approach of incorporating prior chemical knowledge as restraints has been adopted and expanded in modern refinement programs. The REFMAC5 dictionary, for example, organizes prior chemical knowledge using a monomer-based approach that echoes PROLSQ's philosophy [13]. Similarly, the CNS (Crystallography & NMR System) solver incorporates explicit water refinement protocols that extend PROLSQ's basic framework with more sophisticated energy minimization and solvation models [11].

The transition from PROLSQ to modern refinement has seen several key developments:

- Integration of more sophisticated force fields such as PARALLHDG and OPLS, which provide more accurate treatment of non-bonded interactions [1]

- Implementation of maximum-likelihood refinement targets that better account for experimental uncertainty

- Explicit incorporation of solvent molecules in refinement protocols, improving model accuracy, particularly for surface residues [11]

- Advanced parameterization for novel ligands and cofactors through extensible dictionary systems [13]

PROLSQ's Enduring Legacy in Quality Validation

PROLSQ's quality metrics established a paradigm for structural validation that persists in contemporary structural biology. The CSDX force field parameters derived from the Cambridge Structural Database, which were integral to PROLSQ, continue to serve as reference values for structure validation programs such as WHATIF and PROCHECK [1]. This continuity ensures that modern structures can be evaluated against consistent geometric standards, maintaining comparability across the structural database.

Table 2: PROLSQ's Legacy in Modern Refinement and Validation Tools

| Modern Tool | PROLSQ Influence | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| REFMAC5 Dictionary | Monomer-based restraint organization | Crystallographic refinement with prior chemical knowledge [13] |

| CNS Solver | Explicit water refinement protocols | NMR and crystallographic refinement with solvation [11] |

| Rosetta Refinement | Hydrogen bonding and geometry optimization | NMR structure quality improvement [1] |

| WHATIF/PROCHECK | CSDX force field parameters as validation standard | Structure quality assessment and validation |

Application in Drug Discovery and Development

Impact on Structure-Based Drug Design

The quality metrics established by PROLSQ have profound implications for drug discovery, where accurate macromolecular models are essential for reliable virtual screening and lead optimization [12]. The integration of PROLSQ-influenced validation metrics ensures that structural models used in drug design exhibit chemically reasonable geometry, reducing the risk of artifacts influencing computational screening results.

In the context of targeted protein degradation technologies such as PROTACs, accurate structural models are crucial for understanding the ternary complex formation necessary for degradation efficacy. The geometric quality control pioneered by PROLSQ provides the foundation for reliable modeling of these large, flexible complexes [15].

Relevance to Pharmaceutical Development

The quality standards established by PROLSQ extend beyond basic research to impact pharmaceutical development:

- Ensuring reliability of structural models used in rational drug design

- Facilitating fragment-based drug discovery by providing accurate electron density interpretation

- Supporting modeling of drug-receptor interactions through geometrically valid complexes

- Enabling accurate prediction of molecular properties such as solubility through reliable 3D structures [15]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PROLSQ-Influenced Structure Refinement

| Research Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| REFMAC5 Dictionary | Storage of prior chemical knowledge for monomers | Dynamic restraint generation during refinement [13] |

| CNS Solver with Explicit Water | Energy minimization with explicit solvation | Final structure refinement before PDB deposition [11] |

| Rosetta Refinement Protocol | Hydrogen bond network optimization | Improving NMR structure quality for molecular replacement [1] |

| CSDX Force Field Parameters | Reference values for bond lengths and angles | Structure validation using PROCHECK/WHATIF [1] |

| RECOORD Database | Uniformly refined NMR structures | Reference dataset for method development and validation |

Advanced Refinement Techniques

Hydrogen Bond Network Optimization

Recent advances building upon PROLSQ's foundation have demonstrated the critical importance of hydrogen bonding in structure refinement. Research on Rosetta-refined structures has shown that correct identification of hydrogen bonds should be a critical goal of refinement protocols, with a demonstrated correlation between improved hydrogen bonding and better molecular replacement performance [1]. This represents an extension of PROLSQ's original geometric restraint philosophy to more complex electrostatic interactions.

Multi-Method Integration

Modern refinement workflows often integrate multiple approaches to leverage their complementary strengths. The following diagram illustrates how PROLSQ's principles are integrated with contemporary methods:

PROLSQ established the fundamental paradigm of using prior chemical knowledge as restraints in macromolecular refinement, creating a quality standard that continues to influence structural biology decades after its introduction. The geometric metrics it established—for bond lengths, angles, chirality, and planarity—remain essential validation criteria in contemporary structure determination. As structural biology continues to advance into increasingly challenging targets, including membrane proteins and large complexes, the principles established by PROLSQ provide the foundation for maintaining geometric realism while extracting maximal information from experimental data. For drug discovery professionals, understanding these quality metrics is essential for critically evaluating structural models used in structure-based design approaches.

The Transition from Small-Molecule to Macromolecular Refinement Paradigms

The refinement of molecular structures is a critical process in computational drug discovery, bridging the gap between theoretical models and biologically accurate representations. Structure refinement protocols have traditionally evolved along two distinct yet parallel paths: one focused on small molecules and the other on macromolecular systems. While small-molecule refinement often prioritizes the optimization of physicochemical properties and synthetic accessibility, macromolecular refinement confronts the challenge of modeling complex biological assemblies at near-atomic resolution. This divergence stems from fundamental differences in molecular complexity, the energy landscapes being navigated, and the ultimate biological applications.

The emergence of sophisticated computational approaches, particularly artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, is now accelerating both fields. The integration of these technologies with traditional physics-based methods like PROLSQ is creating new paradigms that transcend the historical boundaries between small and large molecule refinement. This protocol examines these evolving methodologies, providing a structured comparison and practical guidance for researchers navigating this transitional landscape.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Refinement Paradigms

| Characteristic | Small-Molecule Paradigm | Macromolecular Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight | < 1,000 Da [16] | > 5,000 Da, often > 1,000,000 Da [16] |

| Representation | Graph-based, 3D coordinates, SMILES strings [17] | 3D atomic coordinates, torsion angles, residue-level representations [17] [18] |

| Primary Challenges | Synthetic accessibility, ADMET optimization [19] [17] | Conformational sampling, force field inaccuracies, model selection [20] [18] |

| Dominant Techniques | Generative AI (Diffusion models), GA, QSAR [19] [17] [21] | Molecular Dynamics, Monte Carlo, knowledge-based restraints [20] [18] |

| Key Applications | Oral bioavailability, intracellular target engagement [16] | Protein-protein interactions, extracellular target modulation [17] [16] |

Comparative Analysis of Refinement Approaches

Small-Molecule Refinement: A Shift Toward De Novo Design

The refinement of small molecules has undergone a fundamental transformation with the adoption of generative AI and evolutionary algorithms. Traditional refinement focused on optimizing existing compound scaffolds through quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and medicinal chemistry. Contemporary approaches now emphasize de novo molecular design, generating novel chemical entities with predefined properties.

Diffusion models have emerged as a particularly powerful framework, operating through an iterative denoising process that generates new molecular structures from random noise [17]. These models excel at structure-based design, creating novel ligands that fit specific binding pockets while satisfying predefined physicochemical constraints. The primary challenge remains ensuring the chemical synthesizability of these AI-generated molecules [17]. Concurrently, evolutionary algorithms using coarse-grained representations provide an alternative approach, as demonstrated by the Evo-MD framework which optimizes molecular properties without relying on extensive pre-existing datasets [21].

Macromolecular Refinement: The Sampling and Scoring Challenge

Macromolecular refinement, particularly for proteins, confronts the dual challenges of adequate conformational sampling and accurate model selection. The core objective is to improve initial template-based models, which often deviate from experimental structures by 2–6 Å root mean square deviation (RMSD) [20]. Unlike small molecules, proteins exhibit complex energy landscapes with numerous local minima, making refinement a particularly challenging multi-dimensional problem.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become a cornerstone of macromolecular refinement, with successful protocols incorporating explicit solvent models, improved force fields, and smart restraints to guide sampling toward native-like conformations [20] [18]. A critical insight has been that refined structures often appear as intermediates during MD trajectories rather than as end-points, necessitating sophisticated analysis of structural ensembles [20]. The application of ensemble averaging over selected subsets of structures has proven more effective than relying on single snapshots [20].

Application Notes: Integrated Refinement Protocol

Protocol 1: AI-Guided Small Molecule Refinement

This protocol details the implementation of a diffusion model-based framework for small molecule refinement and design, with emphasis on integration points with traditional PROLSQ methodologies.

Workflow Overview:

- Target Identification: Define the binding pocket and key interaction features

- Representation Selection: Choose appropriate molecular representation (graph-based, 3D coordinates)

- Conditional Generation: Employ diffusion models with property-based guidance

- Synthetic Accessibility Assessment: Filter generated molecules using retrosynthesis algorithms

- PROLSQ Integration: Refine promising candidates using energy minimization and conformational analysis

Key Parameters for Diffusion Models:

- Noise schedule: Linear variance schedule from β₁=10⁻⁴ to β𝚃=0.02

- Sampling steps: 1000 denoising iterations

- Guidance scale: Classifier-free guidance with weight of 2.5

- Property constraints: Molecular weight (<500 Da), logP range, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors

Protocol 2: Ensemble-Based Macromolecular Refinement

This protocol describes an MD-based refinement approach incorporating PROLSQ for final energy minimization, specifically designed for protein structure improvement.

Workflow Overview:

- Initial Model Assessment: Identify reliable and unreliable regions using quality assessment metrics

- Restraint Strategy Application: Apply strong restraints to reliable regions (force constant of 1 kcal/mol/Ų) and weak restraints to flexible regions (force constant of 0.05 kcal/mol/Ų) [20]

- Ensemble Generation: Conduct multiple independent MD simulations (e.g., 20×20 ns) with explicit solvent

- Cluster Analysis and Selection: Identify dominant conformational clusters using RMSD-based clustering

- Ensemble Averaging: Generate refined structures through averaging of selected cluster members

- PROLSQ Finalization: Apply energy minimization to correct bond geometries and eliminate steric clashes

Critical Implementation Details:

- Solvation: Explicit water model with ≥9 Å padding from protein surface

- Electrostatics: Particle Mesh Ewald with 1 Å grid spacing

- Temperature control: Langevin dynamics at 298K

- Pressure control: Langevin piston at 1 bar

- Integration: 2 fs time step with SHAKE constraint on hydrogen bonds

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Refinement Methodologies

| Methodology | Typical Improvement | Computational Cost | Success Rate | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecule Diffusion Models [17] | N/A (de novo design) | High (GPU-intensive) | 55-69% of FDA approvals (2023-2024) [17] | Chemical synthesizability, accurate scoring [17] |

| Evolutionary Molecular Design [21] | Converges to specific properties | Medium (parallelizable) | Feasibility demonstrated [21] | Limited to coarse-grained representation [21] |

| MD-Based Protein Refinement [20] [18] | ~1% GDT-TS improvement [20] | Very High (CPU/GPU-intensive) | Inconsistent across targets [18] | Force field inaccuracies, model selection [18] |

| Knowledge-Based Protein Refinement [18] | Modest GDT-TS improvement | Low to Medium | More consistent than MD-only [18] | Limited by template availability [18] |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Refinement

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PROLSQ Refinement Suite | Energy minimization and geometry optimization | Core framework for final structure optimization; compatible with both small molecules and macromolecules |

| Martini 3 Coarse-Grained Force Field [21] | Small molecule representation for evolutionary optimization | Enables high-throughput screening; maps 2-4 heavy atoms to single interaction sites |

| CHARMM36 All-Atom Force Field [20] | Physics-based potential for MD simulations | Used with explicit solvent (TIP3P) for protein refinement; provides accurate physical chemistry |

| Generative AI Platforms (e.g., Chemistry42) [19] | De novo small molecule design | Combines generative AI with physics-based methods for molecule generation |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (Evo-MD) [21] | Optimization of molecular properties | Uses genetic algorithms with coarse-grained MD for directed molecular evolution |

| Classifier-Free Guidance [17] | Conditional control of diffusion models | Enables property-constrained generation without separate classifier training |

The transition from small-molecule to macromolecular refinement paradigms reveals a converging trajectory driven by AI and automation. While these domains have historically employed distinct methodologies, they now face shared challenges in predictive accuracy, experimental validation, and integration into automated discovery pipelines. The emergence of diffusion models for small molecules and ensemble-based MD approaches for macromolecules represents significant advancement, yet both fields struggle with accurately scoring and selecting optimal structures from generated ensembles.

The future of structure refinement lies in hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both paradigms. For drug discovery professionals, this translates to a workflow where AI-generated small molecules are refined against structurally optimized macromolecular targets, creating a virtuous cycle of design and validation. As these methodologies mature, they will increasingly be incorporated into closed-loop Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) platforms, fundamentally shifting the paradigm from exploratory screening to targeted molecular creation.

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to the PROLSQ Refinement Protocol

Application Notes

This document details a structured workflow for biomolecular structure refinement, framing the established PROLSQ method within a modern project management and iterative optimization context. The provided protocols are designed to enhance the accuracy and reliability of structures determined by X-ray crystallography, with direct applications in rational drug design. The core principle involves a cyclic process of model adjustment against experimental data, guided by geometric restraints and validated by rigorous quality metrics [1] [14].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Structure Refinement

| Metric | Description | Target Value/Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic R-factor | Measure of agreement between observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes [14]. | Lower values indicate better fit; typically < 25% for well-refined structures [14]. |

| R-free | Cross-validation metric calculated using a subset of reflections not used in refinement [1]. | Should track closely with R-factor; a small difference (~2-3%) indicates a well-refined model [1]. |

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) | Measure of the average distance between atoms in superimposed models. | Used to assess model accuracy against a reference (e.g., ~1.5 Å for MR performance) [1]. |

| Ramachandran Outliers | Percentage of amino acid residues in disallowed regions of torsional angle space. | < 0.5% for high-quality structures. |

The transition from a preliminary atomic model to a high-quality, publication-ready structure requires meticulous execution. The workflow is decomposed into three hierarchical phases, adhering to the 100% Rule from project management, which ensures the entire scope of work is captured without duplication [22] [23]. The Iterative Refinement principle, fundamental to both numerical computing and machine learning, is applied through repeated cycles of model adjustment and validation [24] [25]. This process is significantly enhanced by ensuring all visualization and analysis tools meet minimum color contrast ratios (at least 4.5:1 for standard text) to reduce interpretive errors during critical visual inspection of electron density maps [26] [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Data Preparation and Initial Model Building

This protocol covers the preparation of experimental data and generation of an initial atomic model, which serves as the starting point for iterative refinement.

Objective: To produce a complete and validated set of crystallographic data and a preliminary structural model for refinement.

Step 1: Data Collection and Reduction

- Collect X-ray diffraction data from a single crystal at the optimal resolution (e.g., 0.83 Å to 2.5 Å, depending on the system) [14].

- Process diffraction images to obtain a merged set of structure factor amplitudes (

F_obs) and associated uncertainties (σ(F_obs)). Key outputs include data completeness, multiplicity, and signal-to-noise (I/σ(I)). - Randomly set aside 5-10% of reflections as a "test set" for R-free calculation to monitor overfitting [1].

Step 2: Initial Model Generation

- For Molecular Replacement (MR): Use a known homologous structure as a search model. If an NMR model is used, ensure the Cα backbone RMSD to the crystal structure is within ~1.5 Å for successful MR [1].

- For other methods: Follow established procedures for experimental phasing (e.g., SAD, MAD).

- Perform initial rigid-body refinement to correctly position the model in the unit cell.

Step 3: Preliminary Refinement and Validation

- Run a few cycles of restrained refinement (e.g., using PROLSQ) against the working set of reflections.

- Validate the initial model using geometry validation tools (e.g., MolProbity) to identify Ramachandran outliers, close van der Waals contacts, and incorrect side-chain rotamers.

- Deliverable: A preliminary PDB file, a processed data file (e.g.,

.mtz), and an initial validation report.

Protocol 2: Parameterization for PROLSQ Refinement

PROLSQ (PROtein Least SQuares) is a restrained least-squares refinement method that minimizes a global target function, balancing agreement with experimental data and adherence to ideal stereochemistry [14].

Objective: To define the parameters and weights for the PROLSQ target function to ensure stable and chemically reasonable refinement.

The PROLSQ target function is defined as:

Φ = w_A * Σ |F_obs - F_calc|² + w_B * Σ (r_ideal - r_current)²

Where w_A and w_B are weights for the experimental and geometric terms, respectively.

Table 2: PROLSQ Refinement Parameters and Weighting

| Parameter Class | Description | Function in Refinement |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Coordinates | x, y, z positional parameters for each atom. | Adjusted to maximize the fit to the electron density map (F_obs - F_calc difference map). |

| Atomic Displacement Parameters (B-factors) | Model for atomic vibration and disorder. | Can be refined isotropically or anisotropically; higher resolution data allows more complex modeling [14]. |

| Occupancy | Fraction of time a atom is present at a given position. | Used to model disordered sidechains or alternate conformations. |

| Geometric Restraints | Target values for bond lengths, angles, planes, and chiral volumes based on the Engh & Huber library [14]. | Prevents the model from moving into chemically impossible geometries while fitting the data. |

| Weighting (wA, wB) | Empirical factors balancing the experimental and geometric terms in the target function. | Critical for convergence; initially biased toward geometry, then shifted toward experimental data as the model improves. |

- Procedure:

- Define Stereochemical Dictionary: Use a high-quality parameter library (e.g., based on the CSDX force field) for ideal bond lengths and angles [1] [14].

- Set Initial Weights: Begin refinement with a higher weight on the geometric restraints (

w_B) to maintain reasonable chemistry. - Iterative Weight Adjustment: Over successive cycles, gradually increase the weight on the experimental term (

w_A) to improve the fit to the electron density, monitoring R-free to prevent overfitting. - TLS Refinement: For higher-resolution data, introduce TLS (Translation-Libration-Screw-rotation) parameters to model concerted motion of groups of atoms, which improves the fit and provides dynamical insight [14].

Protocol 3: Iterative Refinement Cycle

This protocol describes the core iterative loop for improving the structural model, which integrates manual model building with computational refinement.

Objective: To progressively improve the atomic model through repeated cycles of computational refinement, manual adjustment, and validation.

- Cycle Initiation: Begin with the initial model and experimental data from Protocol 1.

- Step 1: Computational Refinement

- Execute a cycle of PROLSQ refinement, updating atomic coordinates and B-factors based on the current parameters (Protocol 2).

- Key Action: Monitor the reduction in both R-factor and R-free.

- Step 2: Map Calculation

- Compute a

2mF_o - DF_ccoefficient map for model visualization and anmF_o - DF_ccoefficient map (difference map) to identify errors such as missing atoms or incorrect side chains.

- Compute a

- Step 3: Manual Model Building & Adjustment

- In a graphical program like Coot, examine the difference map. Fit the model to the

2mF_o - DF_cmap and use themF_o - DF_cmap to:- Add/Remove Atoms: Place missing solvent molecules or ligands; remove incorrectly placed atoms.

- Adjust Side Chains: Rotate side chains to fit positive density; model alternate conformations where density supports it.

- Correct Backbone: Rebuild loops in areas of poor density.

- In a graphical program like Coot, examine the difference map. Fit the model to the

- Step 4: Validation and Decision

- Run a validation report to check for steric clashes, Ramachandran outliers, and rotamer issues.

- Analyze the trend in R-free. The cycle is repeated until R-free plateaus and no significant errors are found in the validation report or difference maps.

- Cycle Output: A refined, validated structural model ready for deposition in the Protein Data Bank.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for Structure Refinement

| Item | Category | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| PROLSQ / REFMAC / phenix.refine | Refinement Software | Performs the computational refinement of the model against experimental data using restrained least-squares or maximum-likelihood algorithms [14]. |

| Coot | Model Building Software | A graphical tool for manual model building, fitting, and correction based on electron density maps [1]. |

| CCP4 / PHENIX | Software Suite | Provides an integrated environment for the entire crystallographic workflow, from data processing to refinement and validation. |

| MolProbity / PROCHECK | Validation Software | Analyzes the refined model for stereochemical quality, identifying outliers in bond angles, Ramachandran plots, and clashes [1]. |

| Processed Data File (.mtz) | Data | Contains the observed structure factor amplitudes and is the primary experimental input for refinement. |

| Engh & Huber Parameters | Restraint Library | A library of ideal bond lengths and angles derived from high-resolution small-molecule structures, used as geometric restraints during refinement [14]. |

| TLS Parameters | Refinement Parameter | Used to model the anisotropic displacement of groups of atoms as rigid bodies, improving the model at higher resolutions [14]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the hierarchical decomposition of the entire structure refinement project, from major phases down to specific work packages, ensuring complete project scope management.

In the field of macromolecular structure determination, the refinement process is governed by a target function that balances the agreement with experimental data against the adherence to ideal stereochemical parameters. The PROLSQ program, a foundational refinement method, operationalizes this balance by employing a least-squares minimization function that incorporates both experimental diffraction data and prior knowledge of molecular geometry [1]. This application note details modern protocols for structure refinement, framed within the core principles of PROLSQ-based research, which emphasizes that a high-quality model must simultaneously satisfy experimental observations and conform to physically realistic covalent parameters and non-bonded interactions [1] [28]. The careful construction of the target function is critical not only for the accuracy of the final model but also for its utility in downstream applications, such as molecular replacement in crystallography and drug discovery efforts that rely on precise structural information [1] [29]. This document provides actionable methodologies and analytical tools for researchers to achieve this essential balance, ensuring that refined structures are both experimentally faithful and stereochemically sound.

Quantitative Metrics for Target Function Evaluation

A critical step in refinement is the quantitative assessment of the model's quality. The metrics in Table 1 provide a framework for evaluating the performance of a refinement protocol, balancing experimental fit with model ideality.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Refinement Assessment

| Metric Category | Metric Name | Optimal Range/Target | Description and Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Fit | Crystallographic R-factor | < 0.20 (High-Res.) | Measures the agreement between observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes. [28] |

| Free R-factor (R-free) | Within 2-5% of R-factor | A cross-validation metric calculated with a subset of reflections not used in refinement, guarding against overfitting. [28] | |

| RPF Scores (NMR) | Higher scores indicate better fit | NMR equivalent of R-factors; assesses "goodness of fit" between calculated structures and raw NMR data. [1] | |

| Stereochemical Ideality | RMSD from Ideal Bond Lengths | ~0.02 Å | Root Mean Square Deviation of model bonds from established ideal values (e.g., CSDX database). [1] |

| RMSD from Ideal Bond Angles | ~2.0° | Root Mean Square Deviation of model angles from established ideal values. [1] | |

| Ramachandran Outliers | < 0.5% | Percentage of residues in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. | |

| Global Model Quality | LGscore / MaxSub | Higher scores are better | Scores for identifying native-like models and detecting correct fragments in a protein model. [30] |

| GDT_TS | Higher scores are better (0-100 scale) | Global Distance Test Total Score; measures the global topological similarity of a model to the native structure. [31] | |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Buried Unsatisfied Donors | Minimize | A decrease in the number of buried unsatisfied hydrogen-bond donors correlates with improved model quality and MR performance. [1] |

Experimental Protocols for Structure Refinement

This section provides detailed, actionable protocols for refining protein structures, with an emphasis on integrating modern tools with the foundational principles of the PROLSQ force field.

Protocol: Rosetta-Assisted Refinement for Improved Model Quality

This protocol leverages the Rosetta force field to improve hydrogen-bonding networks and side-chain packing, addressing a key limitation of NMR structures and structures refined with sparse data [1].

- Initial Model Generation: Calculate an initial structural ensemble using a standard package such as CNS (with explicit water refinement) or CYANA, incorporating all available experimental NMR restraints, or generate an initial model from crystallographic data [1].

- Rosetta Refinement Setup:

- Use the Rosetta software suite with its all-atom potential, which includes an orientation-dependent hydrogen bonding term, van der Waals interactions, and an implicit solvent model [1].

- Input: The initial model (e.g., from CNSw refinement). Note that Rosetta refinement is performed in the absence of experimental restraints to allow the force field to drive the model toward a lower energy conformation [1].

- Conformational Sampling: Execute the Rosetta refinement protocol, which is designed to optimize the jigsaw puzzle-like packing of side chains. This step performs thorough conformational sampling to locate low-energy states [1].

- Model Selection and Analysis:

- Evaluate refined models using the Rosetta free energy function.

- Select the top-scoring models for validation.

- Critically, assess the improvement in the hydrogen-bonding network by quantifying the reduction in buried unsatisfied donors [1].

- Optional Restraint Incorporation: Identify consistent, non-bivalent hydrogen bonds from the Rosetta-refined structures and incorporate them as additional restraints in a final round of refinement with a conventional package (e.g., CNS) to ensure the model remains consistent with experimental data [1].

Protocol: Real-Space Refinement for Poor Electron Density Maps

This protocol is particularly useful for improving models derived from poor-quality experimental maps, such as those from molecular replacement with low-identity models [28].

- Initial Model and Map Generation:

- Build an initial model into an experimental electron density map (e.g., from MIR).

- Calculate an initial

2Fo - Fcmap.

- Cyclic Refinement:

- Perform real-space refinement of the model against the current electron density map. This adjusts atomic coordinates to better fit the local density.