Protein Comparison in Biomedical Research: When to Use Structural Alignment vs. Sequence Alignment

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the complementary roles of structural and sequence alignment in protein analysis.

Protein Comparison in Biomedical Research: When to Use Structural Alignment vs. Sequence Alignment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the complementary roles of structural and sequence alignment in protein analysis. We explore the fundamental principles, comparing how sequence alignment identifies evolutionary relationships through amino acid sequences, while structural alignment reveals functional similarities through three-dimensional shape, even when sequences diverge. The content details key methodologies, from established tools like DALI and CE for structure to PSI-BLAST and HHsearch for sequence profiles, and addresses critical challenges like the 'twilight zone' of low sequence identity and computational complexity. Through a comparative analysis of performance metrics and real-world applications in function annotation and drug design, we offer evidence-based guidance for selecting the optimal approach and leveraging emerging hybrid methods that integrate both techniques for superior results in biomedical research.

Core Principles of Protein Alignment: From Linear Sequences to 3D Structures

In the field of protein science, comparing proteins to uncover functional, evolutionary, and structural relationships is a fundamental task. This relies primarily on two methodological pillars: sequence alignment and structural alignment. While often used in tandem, they are based on different principles and are suited to answering distinct biological questions. This guide provides a objective comparison of these two approaches, framing them within the broader thesis of protein comparison research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

At their core, both methods aim to identify equivalent positions between two or more proteins, but they operate on fundamentally different types of data.

Sequence Alignment identifies similarities by arranging protein sequences (the linear chains of amino acids) to maximize residue matches, considering evolutionary substitutions and insertions/deletions (indels) [1]. It can be performed pairwise or with multiple sequences simultaneously (Multiple Sequence Alignment or MSA) [2]. The alignment is typically optimized using a substitution matrix (e.g., BLOSUM, PAM) that encodes the likelihood of one amino acid replacing another over evolutionary time, and algorithms like dynamic programming (e.g., Needleman-Wunsch for global, Smith-Waterman for local alignment) to find the optimal solution [1].

Structural Alignment, in contrast, is based on comparing the three-dimensional shapes of proteins [3]. It is invaluable when sequence similarity is low or undetectable, as structure is often more conserved than sequence over evolution [2] [3]. These methods use the 3D atomic coordinates, typically focusing on the backbone Cα atoms. Unlike sequence alignment, there is no single dominant algorithm. Well-known methods include DALI, which aligns distance matrices, and Mustang, Matt, and FATCAT, which can handle structural flexibility [2] [4] [5].

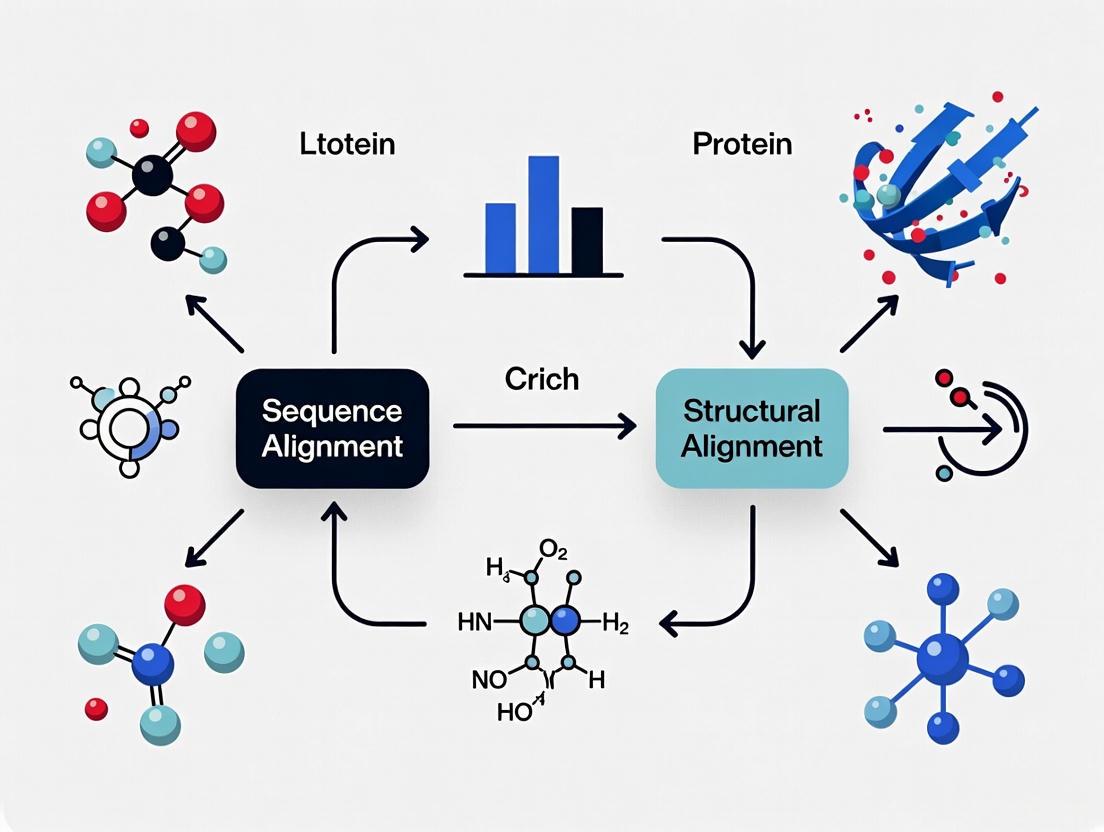

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow for choosing and applying these alignment methods in a research context.

Performance and Accuracy Comparison

The choice between sequence and structural alignment has profound implications for accuracy, especially in detecting distant evolutionary relationships and in template-based protein structure prediction.

A comprehensive benchmark study of 20 alignment methods on 538 non-redundant proteins provides clear quantitative data. The study evaluated the quality of protein structural models built from alignments using the TM-score, a metric where a score >0.5 indicates the same fold and a score <0.17 indicates random similarity [6]. The results demonstrate a dominant advantage for methods leveraging more complex information.

Table 1: Performance of Alignment Methods in Protein Fold Recognition [6]

| Alignment Approach | Representative Methods | Average TM-score* | Relative Advantage over Sequence-Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profile-Profile | HHsearch, HHsearch-II | 0.395 | +49.8% |

| Sequence-Profile | PSI-BLAST, MUSTER | 0.312 | +26.5% |

| Sequence-Sequence | BLAST, NW-align | 0.263 | Baseline |

Note: TM-scores are for models built from the highest-ranked template.

Furthermore, integrating predicted or native structural features (e.g., secondary structure) can improve the TM-score of profile-profile methods by 9.6% or 21.4%, respectively [6]. However, it is critical to note that even the best sequence-based alignments incorporating structural features had TM-scores 37.1% lower than those generated by a pure structural alignment method (TM-align), highlighting the inherent limitation of using sequence-based information alone for precise structural matching [6].

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation

To ensure reproducibility and rigorous assessment, researchers rely on standardized protocols and benchmarks.

Key Experimental Benchmarks Performance validation is conducted against databases of known, curated alignments.

- BAliBASE & HOMSTRAD: Provide reference alignments for protein families and are widely used for benchmarking MSA and structural alignment algorithms [2] [7].

- SABmark: Designed for testing alignment methods on distantly related proteins [7].

Common Evaluation Metrics The quality of an alignment is measured with several key metrics:

- TM-score (Template Modeling Score): Measures structural similarity; topology-dependent and more reliable than RMSD for global fold comparison [6].

- SP score (Sum-of-Pairs score): Used to compare a computed alignment to a reference alignment, ranging from 0 (non-identical) to 1 (identical) [5].

- TC (True Core): Measures the fraction of core alignment columns accurately reproduced in the reference alignment [2].

Detailed Protocol: Structural Alignment with Flexibility Methods like FATCAT and MATT explicitly account for protein flexibility, which is crucial for accurate alignment. A typical workflow involves [5]:

- Input Structures: Provide protein structures in PDB format.

- Initial Rigid Alignment: Generate an initial superposition of the two structures.

- Flexibility Introduction: Identify "pivot points" where the structures can be twisted to improve the alignment of subsequent domains or regions.

- Optimal Alignment Search: Iteratively refine the alignment by evaluating different combinations of rigid blocks and pivot points to maximize a similarity score (e.g., combining structural overlap and penalty for flexibility).

- Statistical Evaluation: Calculate a P-value or Z-score to assess the statistical significance of the alignment against a random background.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful protein comparison research requires a suite of computational tools and resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Protein Alignment

| Category | Tool / Resource | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Alignment | BLAST/PSI-BLAST | Fast sequence database search & profile creation [6]. |

| MUSCLE, MAFFT | Efficient and accurate Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [7]. | |

| Structural Alignment | DALI | Pairwise structure alignment via distance matrix comparison [4] [5]. |

| Mustang, MATT | Multiple Structure Alignment (MStA) of several proteins [2]. | |

| FATCAT | Flexible structural alignment, accounts for hinges and twists [5]. | |

| Benchmarking | BAliBASE, HOMSTRAD | Gold-standard databases for validating alignment accuracy [2] [7]. |

| Unified Models | OneProt | A multi-modal foundation model that integrates sequence, structure, and binding site data in a shared latent space [8]. |

The dichotomy between sequence and structural alignment is a central theme in protein science. Sequence alignment is unparalleled for its speed, scalability, and direct inference of evolutionary relationships. However, structural alignment provides the ultimate validation of homology, especially when sequences have diverged beyond detection. It directly reveals conserved functional cores and active sites that sequence-based methods might miss [5].

The frontier of the field lies in the integration of these modalities. Unified frameworks that treat sequence and structure simultaneously show promise for more reliable alignments, particularly when pure structural methods might be misled by repetitive elements or symmetries [9]. Furthermore, the advent of multi-modal AI systems like OneProt, which align the latent spaces of sequence, structure, and other protein modalities, paves the way for a new generation of powerful, general-purpose protein analysis tools for applications in drug discovery and protein engineering [8].

In conclusion, sequence and structural alignments are complementary tools. The informed researcher must understand their strengths, limitations, and the contexts in which each excels to robustly answer the complex questions of modern molecular biology.

In protein science, sequence identity and structural similarity provide two complementary yet fundamentally different views of the relationship between proteins. Sequence identity, measured by the percentage of identical amino acids at aligned positions, has long served as the foundational metric for inferring homology and transferring functional annotations [10]. Structural similarity, which quantifies the three-dimensional shape resemblance between protein folds, often reveals conserved functional relationships even when sequence signals become undetectable [11] [12].

This divergence stems from the fundamental principle that while sequence dictates structure, and structure determines function, the mapping between sequence and structure is complex and degenerate. Proteins with sequences that have diverged beyond recognition can maintain remarkably similar folds and functions, while minimal sequence changes can sometimes lead to dramatic structural alterations [11] [12]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two approaches, empowering researchers to select appropriate methodologies for protein comparison in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Metrics

Rigorous benchmarking studies demonstrate that the relative performance of sequence- and structure-based methods depends heavily on the evolutionary distance between compared proteins and the specific biological question. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sequence vs. Structure-Based Methods

| Comparison Metric | Sequence-Based Methods | Structure-Based Methods | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fold Recognition Accuracy | 49.8% lower TM-score than profile-profile methods [6] | 26.5% higher TM-score than sequence-profile methods [6] | Benchmark on 538 non-redundant proteins [6] |

| Paralog Function Prediction | Predictive of shared functionality [13] | Outperforms sequence identity for some tasks [13] | Evaluation on human and yeast paralogs [14] |

| Low-Sequence Identity Detection | Limited below 25-30% sequence identity [10] | Detects similarities below 25% sequence identity [12] | Function annotation of novel structures [10] |

| Antibody Clustering | Groups by CDRH3 identity and V/J gene usage [15] | Groups more antibodies despite low sequence identity [15] | Simulated repertoire sequencing data [15] |

When Structural Similarity Outperforms

Structural comparison methods demonstrate particular advantage in the "twilight zone" of sequence similarity (below 25% identity), where sequence-based methods often fail to detect homologous relationships [10] [12]. A comprehensive assessment of 20 alignment methods revealed that profile-profile based methods, which incorporate evolutionary information, generate models with an average TM-score 26.5% higher than sequence-profile methods and 49.8% higher than simple sequence-sequence alignment methods [6].

For predicting shared paralog functions, a 2025 study found that while sequence identity remains predictive, structural similarity metrics or protein language model embeddings outperform sequence identity for specific tasks [13] [14]. Importantly, these alternative similarity metrics are not redundant with sequence identity; combining them leads to improved predictions of shared functionality [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sequence-Based Identification Pipeline

Standard sequence-based identification follows established bioinformatics protocols utilizing tools like BLAST and MMseqs2:

Table 2: Core Components of Sequence Similarity Search

| Component | Description | Typical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Search Algorithm | BLAST, MMseqs2, or similar tools [16] | E-value cutoff (e.g., 0.1-0.001) [16] |

| Identity Cutoff | Percentage of identical residues in alignment [16] | 0-100% (often 30-90% based on purpose) [16] |

| Query Sequence | Protein sequence in FASTA format [16] | Minimum 25 residues for reliable search [16] |

| Database | Non-redundant protein sequences, PDB, UniProt [11] | Target database must be specified |

Workflow Protocol:

- Query Submission: Input a protein sequence in FASTA format or a PDB identifier with specific chain [16].

- Parameter Setting: Define sequence identity cutoff (0-100%) and E-value threshold (typically 0.1-0.001) [16].

- Database Search: Execute search against selected database using algorithms like MMseqs2.

- Result Filtering: Exclude matches with E-values above threshold and identity below cutoff.

- Alignment Analysis: Examine sequence identities, mismatches, insertions, and deletions [16].

Structural Comparison Pipeline

Structural comparison methodologies have evolved significantly with advances in structure prediction and alignment algorithms:

Table 3: Core Components of Structural Similarity Analysis

| Component | Description | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | Generating 3D models from sequence | AlphaFold2, ESMFold, ColabFold [11] [17] |

| Structural Alignment | Comparing 3D coordinates | Foldseek, TM-align, MulPBA [11] [18] |

| Similarity Metrics | Quantifying structural resemblance | TM-score, RMSD, GDT-TS [12] |

| Clustering | Grouping related structures | Leiden algorithm, hierarchical clustering [11] |

Workflow Protocol (based on ProteinCartography pipeline [11]):

- Input Structure: Provide a protein of interest as a PDB file or FASTA sequence.

- Structure-based Search: Perform Foldseek search against structure databases (AlphaFold/UniProt50, AlphaFold/Swiss-Prot) to identify structurally similar proteins [11].

- All-v-All Comparison: Compare structure of every protein to every other protein using

foldseek search[11]. - Similarity Scoring: Calculate TM-scores using

foldseek aln2tmscore(values range 0-1, where 1 indicates identical structures) [11]. - Clustering Analysis: Cluster proteins using algorithms like Leiden clustering based on the all-v-all similarity matrix [11].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Create navigable 2D/3D maps of protein space using techniques like UMAP or t-SNE for visualization [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Resources for Protein Comparison Studies

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database [13] | Database | Repository of predicted protein structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| Foldseek [11] | Software | Fast structural similarity search & alignment | https://foldseek.com/ |

| RCSB PDB [16] | Database | Experimental protein structures & search tools | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| MMseqs2 [16] | Software | Sensitive sequence similarity searching | https://github.com/soedinglab/MMseqs2 |

| UniProt [11] | Database | Comprehensive protein sequence & functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ |

| ProteinCartography [11] | Pipeline | Creates interactive maps of protein families | https://github.com/arcadia-science/ |

| PDB Protein Blocks [18] | Method Library | Library of local backbone conformations for structural alignment | Research tools |

Integrated Decision Framework

For comprehensive protein analysis, researchers should adopt a integrated approach that leverages both sequence and structural information:

The most powerful contemporary approaches combine both methodologies. As demonstrated in recent protein function prediction studies, integrating sequence identity with structural similarity and protein language model embeddings provides complementary information that significantly enhances predictions of shared paralog functionality beyond what either method can achieve alone [13] [14]. Tools like ProteinCartography exemplify this integration by beginning with sequence-based searches (BLAST), incorporating structure-based searches (Foldseek), and creating unified navigable maps that cluster proteins based on comprehensive similarity metrics [11].

This combined approach is particularly valuable for drug discovery applications, where understanding functional convergence despite sequence divergence can reveal new therapeutic targets and antibody candidates that might be missed by sequence-only methods [15].

Why Protein Structure is More Conserved Than Sequence in Evolution

Evolutionary Foundation and Core Principles

The observation that protein three-dimensional structure is more conserved than the primary amino acid sequence is a fundamental principle in molecular evolution. While sequences mutate and diverge over evolutionary time, the structural scaffolds and functional motifs of proteins demonstrate remarkable persistence. This conservation occurs because natural selection acts primarily on the function of proteins, which is dictated by their three-dimensional architecture rather than their linear sequence composition. Proteins with vastly different sequences can fold into remarkably similar structures and perform equivalent biological functions, illustrating that evolutionary constraints have limited the ability of proteins to become vastly different in their structural organization [19].

The underlying mechanism for this phenomenon stems from the degeneracy of the genetic code and the robustness of protein folds to amino acid substitutions. A protein's structure is determined by the physical and chemical properties of its amino acids and their interactions, not merely by their specific identity. Hydrophobic interactions, which drive the burial of non-polar residues in the protein core, and tertiary interactions, which stabilize the overall fold, can be maintained by a variety of amino acids with similar biochemical properties [20] [21]. Consequently, a protein fold can remain stable even as its sequence undergoes substantial change, provided that the key residues responsible for stabilizing the fold and function are preserved, or conservatively substituted [21] [19]. Research has shown that protein structures can be three to ten times more conserved than the amino acid sequence that encodes them [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Sequence and Structure Conservation

Performance Metrics for Alignment Methods

The divergence between sequence and structure conservation becomes particularly evident when comparing the performance of different alignment methodologies. The accuracy of protein structure prediction and homology detection is highly dependent on the type of alignment method used, with structure-based methods consistently outperforming sequence-based ones, especially for distantly related proteins.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Alignment Methods in Fold Recognition

| Alignment Method Category | Average TM-score on Benchmark | Key Characteristics | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Sequence | Lowest (Baseline) | Fast but limited sensitivity for distant homology. | BLAST, FASTA, Smith-Waterman [6] |

| Sequence-Profile | 26.5% higher than Sequence-Sequence | Uses evolutionary information from MSAs; moderate sensitivity. | PSI-BLAST [6] |

| Profile-Profile | 49.8% higher than Sequence-Sequence | Compares evolutionary profiles; high sensitivity for remote homology. | HHsearch [6] |

| Structure-Based | 37.1% higher than Profile-Profile | Directly uses 3D structural coordinates; highest accuracy. | TM-align, FATCAT, SARST2 [22] [23] [6] |

TM-score (Template Modeling Score) is a key metric for measuring structural similarity, ranging from 0 to 1, where a score >0.5 indicates generally the same fold, and a score <0.2 suggests unrelated structures [22]. The data clearly demonstrates a hierarchy of accuracy, with methods leveraging more complex evolutionary and structural information yielding superior results.

Empirical Evidence from Benchmarking Studies

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide concrete evidence for the superiority of structure-based comparisons. An assessment of 20 representative sequence alignment methods on 538 non-redundant proteins revealed that even the most advanced profile-profile methods produce models with TM-scores significantly lower than those from structural alignment programs like TM-align [6]. This performance gap is most pronounced for "Hard" targets with very distant evolutionary relationships, where sequence signals are often too weak to detect.

Furthermore, modern structural alignment tools have achieved remarkable speed and accuracy. For instance, SARST2, a high-throughput algorithm, recently demonstrated an information retrieval accuracy of 96.3% when identifying family-level homologs in the SCOP database, outperforming other state-of-the-art methods like FAST (95.3%), TM-align (94.1%), and Foldseek (95.9%) [23]. This highlights that structural alignment is not only more accurate but can also be implemented efficiently enough to search massive databases containing hundreds of millions of predicted structures.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Protocols for Studying Conservation

Investigating the relationship between sequence and structure conservation relies on specific experimental and computational workflows. The following protocols outline key methodologies cited in the literature.

Protocol 1: Multiple Structure Alignment and Sequence Profile Analysis This procedure, used to identify conserved residues critical for fold stability, involves [20]:

- Protein Set Selection: A non-redundant set of protein structures sharing a common fold is assembled. The structural similarity is quantitatively defined using a metric like the Protein Structural Distance (PSD).

- Multiple Structure Alignment: A structure alignment algorithm (e.g., FATCAT, CE) is used to superimpose the 3D coordinates of the selected proteins optimally.

- Structure-Based Sequence Profile Generation: The multiple structure alignment is used to create a structure-guided sequence alignment. From this, a sequence profile is built, highlighting positions where amino acids are conserved.

- Analysis of Conserved Residues: The locations and chemical properties of the conserved residues are analyzed. Studies show the most conserved residues are typically involved in core tertiary interactions and are located in structurally conserved regions, rather than being distributed randomly [20].

Protocol 2: Assessing Structural Conservation in Non-Homologous Proteins This protocol is designed to identify and analyze structural motifs shared by proteins with no detectable sequence homology [19]:

- Structure Database Search: A tool like the Vector Alignment Search Tool (VAST), which uses geometric criteria, is employed to search the PDB for proteins with similar 3D structures to a query.

- Structure Alignment and Metric Calculation: The identified structures are superposed using software like PyMOL. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the atomic positions is calculated to quantify structural similarity. The amino acid sequence identity is also calculated from the structural alignment.

- Identification of Dissimilar Sequences/Similar Structures: Protein pairs are identified that have a low sequence identity (e.g., <25%) but also a low RMSD (e.g., <3.5 Å), indicating high structural conservation despite sequence divergence. Examples include the globin fold found in oxygen-transport proteins and light-absorbing pigments [19].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process and key metrics used in Protocol 2 for identifying structural conservation in the absence of sequence homology.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Protein Structure and Sequence Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Central repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids [22]. |

| AlphaFold Database | Database | Resource of protein structure predictions for a vast range of organisms, expanding the structural universe [24] [23]. |

| DALI | Software | Algorithm for pairwise structure comparison; a pioneering tool for structural alignment [25] [23]. |

| TM-align | Software | Algorithm for fast protein structure comparison based on TM-score, sensitive to global topology [22] [23]. |

| FATCAT (jFATCAT) | Software | Flexible structure alignment algorithm that accounts for conformational changes and circular permutations [22]. |

| SARST2 | Software | High-throughput structural alignment search algorithm for massive databases, combining speed and accuracy [23]. |

| PSI-BLAST | Software | Sequence-profile search tool used to create position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) from MSAs [6]. |

| HHsearch | Software | Profile-profile alignment method using hidden Markov models (HMMs) for sensitive homology detection [6]. |

| PyMOL | Software | Molecular visualization system for rendering and analyzing 3D molecular structures [19]. |

| CLUSTAL Omega | Software | Tool for performing multiple sequence alignments, used to visualize sequence conservation [26] [21]. |

Implications for Biological Research and Drug Development

The greater conservation of structure over sequence has profound implications for fundamental research and applied biotechnology. In evolutionary biology and phylogenetics, it allows researchers to uncover deep evolutionary relationships between proteins that are obscured at the sequence level, enabling the construction of more accurate phylogenetic trees [21] [19]. For functional annotation, identifying a conserved structural fold in a protein of unknown function can provide the first, and often most reliable, clue about its biological role, as structure is a direct reflection of function [21].

In the field of drug development, this principle is critically important. Many successful drugs target conserved functional sites on proteins, such as active sites of enzymes or binding pockets of receptors. These sites are often structurally conserved even across different protein families. Understanding the conserved structural architecture of a target protein family, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) or kinases, allows for the rational design of broad-spectrum inhibitors or drugs with higher specificity, reducing off-target effects [23]. Furthermore, the rise of efficient structure alignment tools like SARST2 enables high-throughput virtual screening against massive structural databases, dramatically accelerating the early stages of drug discovery by identifying novel drug targets and potential lead compounds [23].

In the field of comparative protein analysis, sequence alignment and structural alignment offer complementary perspectives for uncovering evolutionary relationships and functional annotations. While sequence-based methods compare the linear order of amino acids, structural alignment focuses on the three-dimensional spatial arrangement of atoms, capturing conserved architectural features that often persist long after sequence similarity has faded into the "twilight zone" of detection [27] [28]. This divergence in fundamental approach leads to significant differences in what each method can reveal about protein function and evolutionary history. Proteins with low sequence identity can share remarkable structural similarity, reflecting distant evolutionary relationships undetectable by sequence alone [27] [29]. Conversely, sequence alignment remains indispensable for identifying conserved functional residues and analyzing evolutionary rates across protein families [30] [31]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, their performance characteristics, and their respective capacities for biological insight, with particular relevance for researchers in molecular biology and drug development.

Core Methodology Comparison

Fundamental Principles and Technical Approaches

Sequence alignment operates on the primary principle of comparing linear amino acid sequences using substitution matrices and gap penalties to maximize identity or similarity. Advanced methods employ position-specific scoring matrices (PSSM) from tools like PSI-BLAST or hidden Markov models (HMMs) to detect distant homologs by leveraging evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments [31]. The alignment process can be global (Needleman-Wunsch) or local (Smith-Waterman), with modern implementations focusing on progressive alignment strategies that build multiple alignments following phylogenetic guide trees [32].

Structural alignment compares the three-dimensional coordinates of protein structures, typically focusing on Cα atoms. The core algorithms include rigid-body superposition (Kabsch algorithm), distance matrix approaches (DALI), combinatorial extension (CE), and flexible alignment methods (FATCAT) that account for conformational changes through introduced twists [27] [28]. These methods fundamentally seek to maximize the number of equivalent residues while minimizing the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between superimposed atomic positions.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The quality of structural alignments is typically assessed using three principal metrics: Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), which measures the average distance between superimposed atoms; Template Modeling Score (TM-score), a length-independent measure that ranges from 0 to 1 (with values >0.5 indicating the same fold); and Global Distance Test Total Score (GDT_TS), which calculates the average percentage of residues superimposed under multiple distance thresholds [27]. For sequence alignments, accuracy is typically measured against reference alignments from databases like BAliBASE using the sum-of-pairs score (SPS) or developer score, which quantify the agreement with curated reference alignments [32].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Structural and Sequence Alignment Methods

| Method Category | Primary Metric | Typical Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Alignment | RMSD | 0Å → ∞ | Lower values indicate better structural similarity |

| TM-score | 0-1 | >0.5: same fold; <0.2: random similarity | |

| GDT_TS | 0-100% | Higher percentages indicate better global similarity | |

| Sequence Alignment | Sum-of-Pairs Score | 0-1 | Higher values indicate better agreement with reference |

| Sequence Identity | 0-100% | >25%: typically homologous; <20%: twilight zone | |

| E-value | 0 → ∞ | Lower values indicate more significant matches |

Biological Insights: Functional and Evolutionary Revelations

Detection of Evolutionary Relationships

Structural alignment excels at identifying deep evolutionary relationships that persist when sequence similarity falls below 20-25% identity—the so-called "twilight zone" where sequence-based methods struggle [27] [28]. Structural comparisons can reveal common ancestral folds even when proteins have undergone circular permutations, domain shuffling, or extensive insertions and deletions [28]. The conservation of structural cores, particularly hydrophobic residues essential for folding stability, often provides the only detectable evidence of common ancestry in extremely divergent proteins [28].

Sequence alignment provides superior resolution for recent evolutionary events and detailed phylogenetic analysis. Through methods like Mean Protein Evolutionary Distance (MeaPED), researchers can quantify differential evolutionary pressures across viral proteomes, identifying "hot-spot" proteins with high evolutionary rates (e.g., influenza hemagglutinin) and "cold-spot" proteins with strong purifying selection (e.g., RNA-directed RNA polymerase) [30]. Sequence-based phylogenetic reconstruction enables precise tracing of evolutionary pathways and divergence times, particularly for closely related proteins where structural comparisons would lack discriminatory power.

Functional Annotation and Prediction

Structural alignment enables function prediction through structural motifs and active site identification, even without sequence similarity. The spatial arrangement of residues in three dimensions often reveals conserved functional mechanisms that are undetectable at the sequence level [27]. Structural comparisons can identify catalytic triads, binding pockets, and allosteric sites through spatial conservation patterns, making them particularly valuable for annotating proteins of unknown function [27] [28]. This approach has proven especially powerful for identifying distant relationships in enzyme families where the structural scaffold supporting the active site remains conserved despite extensive sequence divergence.

Sequence alignment enables domain architecture analysis and conserved motif identification through multiple sequence alignments of protein families. The identification of specificity-determining positions (SDPs) through sequence analysis helps elucidate functional specificities within protein subfamilies [32]. Sequence methods also excel at identifying linear binding motifs, signal peptides, and post-translational modification sites that may not manifest obvious structural signatures [32]. For drug development, sequence-based approaches can identify functionally important residues through conservation patterns across entire protein families.

Table 2: Functional and Evolutionary Insights Revealed by Each Method

| Biological Insight | Structural Alignment Strength | Sequence Alignment Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Distant Homology Detection | Excellent for folds conserved despite low sequence identity | Limited to "twilight zone" (>20% identity) |

| Active Site Identification | Through 3D spatial conservation patterns | Through linear conserved motifs |

| Evolutionary Rate Analysis | Limited to major structural changes | Precise quantification using methods like MeaPED |

| Domain Architecture | Through 3D spatial arrangement | Through linear sequence analysis |

| Functional Specificity | Limited to structural determinants | Excellent for specificity-determining positions |

| Binding Site Prediction | Excellent through pocket geometry | Limited to sequence motifs |

Experimental Data and Benchmarking

Performance on Standardized Datasets

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal distinct performance characteristics for structural and sequence alignment methods. In assessments using the ASTRAL40 dataset (remote homologs with <40% sequence identity from SCOP), structural alignment methods like CE and DALI show high correlation in identifying equivalent residues, with alignments agreeing on more than half of aligned positions on average [28]. The number of equivalent residues identified by CE and DALI is highly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97), though RMSD values show more variation [28].

For sequence-based methods, large-scale benchmarking on 538 non-redundant proteins demonstrates that profile-profile alignment methods generate models with average TM-scores 26.5% higher than sequence-profile methods and 49.8% higher than sequence-sequence alignment methods [31]. The advantage of profile-based methods becomes increasingly pronounced as sequence identity decreases, with no obvious performance difference between PSSM-based and HMM-based profiles [31].

Performance in Challenging Cases

The performance gap between methodologies widens significantly for particularly challenging alignment scenarios. In the RIPC dataset (protein pairs requiring large indels, containing circular permutations, repetitions, or conformational variability), structural alignment methods produce considerably different alignments that match reference alignments less successfully compared to easier cases [28]. This highlights the ongoing challenges in aligning proteins with substantial structural flexibility or unusual evolutionary relationships.

For RNA alignment, benchmark studies using BRAliBase reveal that sequence identity directly impacts performance, with most sequence alignment programs producing high-quality alignments down to approximately 55% average pairwise sequence identity (APSI), below which structural alignment methods become necessary [33]. Performance drops dramatically in the "twilight zone" for RNA (starting at 60% APSI, compared to 20% for proteins), reflecting the additional constraints of structural conservation in functional RNAs [33].

Table 3: Benchmark Performance Across Method Types and Difficulty Levels

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Easy Targets (High Identity) | Hard Targets (Low Identity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Sequence | BLAST, FASTA | Excellent performance | Poor performance (<20% identity) |

| Sequence-Profile | PSI-BLAST | Very good performance | Moderate performance |

| Profile-Profile | HHsearch, PRC | Excellent performance | Good performance |

| Rigid Structural | DALI, CE | Excellent performance | Good performance |

| Flexible Structural | FATCAT | Excellent performance | Very good performance |

Key Databases and Software Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Comparison

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures |

| SCOP/CATH | Database | Hierarchical classification of protein domains |

| FSSP | Database | Families of Structurally Similar Proteins based on DALI |

| BAliBASE | Database | Benchmark alignment database for method evaluation |

| DALI | Software | Distance matrix alignment for structural comparison |

| FATCAT | Software | Flexible structural alignment allowing twists |

| TM-align | Software | Sequence-order independent structural alignment |

| CE | Software | Combinatorial Extension algorithm for structural alignment |

| PSI-BLAST | Software | Position-Specific Iterated BLAST for profile creation |

| HHsearch | Software | HMM-HMM comparison for remote homology detection |

| RCSB Comparison Tool | Web Service | Integrated platform for sequence and structure alignment |

Standard Experimental Workflows

The standard workflow for sequence-based evolutionary analysis typically begins with database search using BLAST or similar tools, followed by multiple sequence alignment construction, phylogenetic tree building, and evolutionary rate calculation using methods like MeaPED or dN/dS ratios [30] [32]. For structure-based function annotation, the process involves structural alignment to known folds, identification of conserved structural motifs, analysis of binding site geometry, and inference of molecular function through structural similarity [27] [28].

Diagram 1: Structural Analysis Workflow for Function Prediction

Diagram 2: Sequence Analysis Workflow for Evolutionary Studies

Integrated Approaches and Future Perspectives

The most powerful contemporary approaches integrate both sequence and structural alignment methodologies to leverage their complementary strengths. Structure-guided sequence alignment improves accuracy for distantly related proteins by using structurally conserved regions to anchor sequence alignments [27]. Similarly, the combination of sequence profiles with predicted structural features (secondary structure, solvent accessibility) significantly enhances remote homology detection [31].

Emerging methods like GRAFENE represent the next generation of integrated approaches, using graphlet-based alignment-free networks to combine 3D structural data with sequence residue order information [29]. Similarly, energy profile comparison approaches leverage knowledge-based potentials to assign energetic feature vectors to proteins, enabling rapid comparison based on structural stability patterns derived from either sequence or structure [34]. These methods demonstrate that the integration of complementary information types substantially improves both the accuracy and efficiency of protein comparison.

For drug development professionals, these integrated approaches are particularly valuable for identifying functional sites and assessing binding pocket conservation across protein families. Structural alignment reveals conserved geometry of potential drug binding sites, while sequence analysis identifies functionally critical residues and assesses conservation across orthologs and paralogs—critical information for evaluating potential side effects and species specificity in preclinical development.

Both structural and sequence alignment methods provide unique yet complementary biological insights. Structural alignment reveals deep evolutionary relationships through conserved architectural principles and enables function prediction through spatial conservation patterns. Sequence alignment provides superior resolution for recent evolutionary events, functional specificities, and phylogenetic analysis. The integration of both approaches, augmented by emerging methodologies like energy profile comparison and graphlet-based network analysis, represents the most promising path forward for comprehensive protein function and evolution analysis. For researchers in drug development, understanding the strengths and limitations of each method is crucial for effective target assessment, binding site identification, and evaluation of conservation across species.

In the fields of structural biology and bioinformatics, comparing proteins is fundamental to understanding their function, evolution, and potential as drug targets. Two primary philosophical approaches underpin this analysis: sequence alignment and structural alignment. Sequence alignment identifies similarities in the linear arrangement of amino acids, operating on the principle that sequence defines structure. Structural alignment compares the three-dimensional shapes of proteins, based on the paradigm that structure defines function. Each approach relies on distinct metrics for quantification: E-value and Sequence Identity for sequence analysis, and RMSD and TM-score for structural comparison. This guide provides an objective comparison of these four key terminologies, detailing their methodologies, interpretations, and applications in protein research.

Metric Definitions and Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, interpretation, and primary applications of RMSD, TM-score, E-value, and Sequence Identity.

| Metric | Full Name | Type of Alignment | Core Principle | Value Range & Interpretation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD [12] | Root-Mean-Square Deviation | Structural | Average distance between equivalent atoms after superposition. | 0 Å: Perfect match.<2 Å: High similarity.>3-4 Å: Notable differences. [12] | Quantifying local, atom-level accuracy in structural superimposition. Sensitive to local errors. |

| TM-score [35] [12] | Template Modeling Score | Structural | Normalized, length-independent score measuring global fold similarity. | (0, 1]~1: Perfect match.>0.5: Same fold.<0.17: Random, unrelated proteins. [35] [36] [12] | Assessing global, topological similarity. Robust to local structural variations. |

| E-value [1] [37] | Expectation Value | Sequence | Number of matches with a similar score expected by chance in a database search. | ~0: Highly significant.<0.001: Significant.> 0.001: Potentially non-significant. | Assessing statistical significance in database searches (e.g., BLAST). |

| Sequence Identity [1] | Sequence Identity | Sequence | Percentage of identical residues in the aligned sequence regions. | 0-100%>25%: Often indicates homology.<25%: "Twilight zone" of remote homology. [12] | Inferring evolutionary relationships and homology at the sequence level. |

A critical insight from comparative analyses is that Sequence Identity and structural similarity can be decoupled. Proteins with sequence identity below 25% can still share highly similar three-dimensional folds, a phenomenon often observed in remote homologs [12]. This underscores the necessity of structural comparison metrics for a complete understanding of protein relationships, especially in the "twilight zone" of sequence similarity.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively evaluate the performance of alignment methods and their associated metrics, the scientific community relies on standardized benchmark studies. The following workflow outlines a typical protocol for comparing sequence and structural alignment methods.

Detailed Protocol Steps

Select Benchmark Datasets: Curated datasets with known "ground truth" alignments or classifications are essential.

- For Sequence Alignment: The BAliBASE dataset is widely used, providing reference alignments based on 3D structural superpositions and manual refinement [37].

- For Structural Alignment: Datasets derived from structural classifications like SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins) or CATH are common. For instance, a benchmark might use a set of protein pairs from the same SCOP superfamily but different families to test remote homology detection [28] [12].

Generate Alignments: The selected dataset is analyzed using various alignment tools.

Calculate Metrics: For each alignment produced, the relevant metrics are computed.

- For structural alignments, both RMSD and TM-score are calculated from the same superposition to compare their utility [28].

- For sequence alignments from a database search, E-value and Sequence Identity are recorded for each hit.

Validate Against Ground Truth: The accuracy of the alignments is assessed by comparing them to the reference data.

- One method is to calculate the extent of agreement with a manually curated reference alignment, often reporting the fraction of correctly aligned residues [28].

- Another approach, used in clustering studies, is to use cluster validity criteria to measure how well the alignment-based groupings match the known biological classifications (e.g., SCOP families) [37].

Analyze Performance: The final step involves synthesizing the results. A key finding from such benchmarks is that while sequence-based methods are extremely fast, structure-based methods can identify homologous relationships that sequence-based methods miss in the "twilight zone" of low sequence identity [12]. Furthermore, among structural metrics, TM-score is often favored over RMSD for assessing global fold similarity because it is less sensitive to local variations and is normalized for protein length [35] [28].

Interplay of Alignment Metrics

In practice, these metrics are not used in isolation. The following diagram illustrates how RMSD, TM-score, E-value, and Sequence Identity can be integrated into a research workflow to provide a multi-faceted assessment of protein similarity.

To implement the experimental protocols and utilize these metrics, researchers rely on a suite of software tools and databases. The following table lists key resources.

| Tool / Database | Type | Primary Function | Key Metric(s) Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST [1] [37] | Software Suite | Fast sequence similarity search and alignment. | E-value, Sequence Identity |

| TM-align [38] | Software Algorithm | Rapid protein structure alignment. | TM-score, RMSD |

| US-align [39] | Software Algorithm | Universal structure alignment of proteins, RNAs, and DNAs. | TM-score |

| DALI [28] | Software Algorithm & Database | Pairwise structure comparison and database search. | Z-score (structural similarity) |

| CE (Combinatorial Extension) [28] | Software Algorithm | Pairwise protein structure alignment. | RMSD, Alignment Length |

| BAliBASE [37] | Benchmark Dataset | Reference dataset for evaluating sequence alignment methods. | N/A (Reference Standard) |

| SCOP [28] [12] | Database | Manual classification of protein structural relationships. | N/A (Classification System) |

The choice between sequence-based and structure-based alignment, and their associated metrics, is dictated by the biological question. For rapid database screening and analyzing close homologs, E-value and Sequence Identity are indispensable. However, for confirming fold similarity, analyzing remote evolutionary relationships, or assessing protein models where global topology is key, TM-score provides a robust, length-independent measure that surpasses RMSD's sensitivity to local deviations. A comprehensive protein comparison strategy often leverages the speed of sequence-based metrics to triage results, followed by the deep, topological insights provided by structural alignment and metrics like TM-score to draw biologically meaningful conclusions.

A Practical Guide to Alignment Tools and Their Real-World Applications

In the field of structural biology, comparing protein three-dimensional structures is fundamental for establishing evolutionary relationships, annotating function, and understanding functional mechanisms. While sequence-based alignment methods are invaluable, they suffer from a critical limitation: protein sequence evolves and diverges much faster than protein structure. Consequently, structural alignment methods become essential tools for detecting similarities between proteins when their sequences have diverged beyond recognition by standard sequence alignment techniques [28] [40]. These methods establish residue-residue correspondences based on the optimal superposition of three-dimensional shapes and conformations, requiring no prior knowledge of equivalent residues and largely ignoring amino acid type [22]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of four leading structural alignment algorithms—DALI, CE, FATCAT, and TM-align—focusing on their algorithmic approaches, performance characteristics, and optimal applications within biomedical research and drug development.

Algorithmic Approaches and Methodologies

Core Principles and Alignment Strategies

Each major structural alignment algorithm employs a distinct strategy for identifying structurally equivalent regions between proteins.

DALI (Distance Matrix Alignment) uses an exhaustive all-against-all comparison of protein structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Its method involves breaking protein structures into short peptide fragments and building a distance matrix for each structure based on the intramolecular distances between Cα atoms. DALI then searches for similar contact patterns between pairs of fragments from the two proteins being compared, combining these matches into a final alignment [28] [41].

CE (Combinatorial Extension) operates by identifying segments of two structures with similar local structures, then combinatorially combining these regions to align the maximum number of residues while minimizing the root mean square deviation (RMSD). The algorithm uses a rigid-body approach, keeping relative orientations of atoms fixed during superposition and assuming aligned residues occur in the same order in both proteins [22].

FATCAT (Flexible structure AlignmenT by Chaining Aligned fragment pairs allowing Twists) introduces a groundbreaking approach by accommodating protein flexibility during alignment. It builds alignments by chaining aligned fragment pairs (AFPs) together, allowing for twists between rigid domains. This innovative strategy permits independent alignment of different protein regions, making it particularly valuable for comparing structures that undergo conformational changes [42] [22].

TM-align utilizes a heuristic dynamic programming iteration approach optimized through a TM-score rotation matrix. This algorithm is specifically designed for sensitivity to global topology rather than local geometry. It performs sequence-independent residue-to-residue alignments, making it exceptionally fast compared to other methods—approximately four times faster than CE and 20 times faster than DALI according to published benchmarks [38] [43].

Visualization of Algorithmic Relationships and Workflows

The following diagram summarizes the core methodological relationships and workflows among the four structural alignment algorithms:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Assessment

Quantitative Benchmarking Across Protein Classes

Rigorous benchmarking of structural alignment algorithms typically employs datasets categorized by difficulty, often derived from curated resources like SCOP, ASTRAL, SISYPHUS, and HOMSTRAD [28] [40]. Performance is evaluated using multiple metrics, including RMSD, number of equivalent residues, alignment coverage, and TM-score, which normalizes for protein size and provides a more reliable measure of global similarity [43] [22].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Different Difficulty Categories

| Algorithm | Easy Targets (High Seq Identity) | Medium Targets (Remote Homology) | Hard Targets (Circular Permutations/Repetitions) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DALI | High agreement with reference alignments | Correlated with CE (Spearman: 0.96 EQR) | Lower agreement with reference alignments | [28] |

| CE | High agreement with reference alignments | Correlated with DALI (Spearman: 0.96 EQR) | Agreement decreases for challenging pairs | [28] |

| FATCAT | Comparable to CE performance | Effective for beta-rich proteins | Handles flexibility; better with TOPS++ extension | [42] [22] |

| TM-align | Higher accuracy and coverage | Fast, topology-sensitive | Detects global fold similarity despite local variations | [38] |

EQR: Equivalent Residues

Key Performance Metrics and Statistical Correlations

Analysis of 355 pairs of remote homologous proteins from the ASTRAL40 set revealed that CE and DALI show strong correlation in identifying structurally similar regions. The number of equivalent residues (EQR) between these methods demonstrated a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.97 and Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.96, indicating remarkable consistency in detecting the extent of structural similarity. However, RMSD values normalized for 100 residues (RMSD100) showed lower correlation (Pearson: 0.72, Spearman: 0.86), suggesting greater variability in assessing the geometric quality of alignments [28].

Table 2: Statistical Correlation Between CE and DALI on ASTRAL40 Set

| Structural Similarity Metric | Pearson Correlation Coefficient | Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equivalent Residues (EQR) | 0.97 | 0.96 | Very high agreement on alignment length |

| RMSD100 | 0.72 | 0.86 | Moderate agreement on structural quality |

When applied to more challenging datasets containing proteins with repetitions, indels, permutations, and conformational variability (RIPC set), all methods showed decreased performance, though structure-based methods consistently outperformed sequence-based approaches, particularly at low sequence identity levels [28] [40].

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Workflow

To ensure reproducible evaluation of structural alignment algorithms, researchers should follow a standardized experimental protocol:

Dataset Preparation: Curate benchmark sets from reliable databases such as:

Structure Preprocessing:

- Extract protein chains and remove ligands, ions, and water molecules

- Ensure all structures contain complete Cα atom coordinates

- For flexibility analysis, identify conformational variants of the same protein

Alignment Execution:

- Run each algorithm with default parameters for fair comparison

- For flexible methods like FATCAT, compare both rigid and flexible modes

- For TM-align, utilize both global and local alignment options

Result Analysis:

- Compute standard metrics: RMSD, TM-score, sequence identity, number of equivalent residues

- Compare to reference structural alignments where available

- Statistically analyze correlation between different methods

Assessment of Alignment Accuracy

The accuracy of structure-based alignments is typically assessed by comparison to manually curated reference alignments from databases like SISYPHUS and HOMSTRAD [28] [40]. Performance is measured by the extent to which computational alignments match the reference in identifying equivalent residues. Studies have demonstrated that structure-based methods consistently produce more reliable alignments than sequence-based methods, with the advantage becoming particularly pronounced at sequence identities below 20-30% [40]. For residues in regular secondary structures or buried in the protein core, structure-based methods show even greater superiority, as these regions maintain structural integrity even when sequences have diverged significantly.

Key Databases and Software Tools

Table 3: Essential Resources for Structural Alignment Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for experimental protein structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| Dali Server | Web Server | Pairwise and multiple structure comparisons using DALI | http://ekhidna2.biocenter.helsinki.fi/dali/ |

| FATCAT Server | Web Server | Flexible structure alignment with rigid and twist-enabled modes | http://fatcat.burnham.org/ |

| TM-align | Standalone Tool | Fast topology-based structure alignment | https://zhanggroup.org/TM-align/ |

| CE-MC Server | Web Server | Multiple structure alignment using CE algorithm | http://cemc.sdsc.edu |

| RCSB Pairwise Alignment | Web Tool | Multiple algorithm comparison interface | https://www.rcsb.org/docs/tools/pairwise-structure-alignment |

| HOMSTRAD | Database | Curated structure-based alignments for homologous families | http://www.homstrad.org/ |

| SISYPHUS | Database | Manually curated alignments with complex relationships | [28] |

Implementation and Accessibility

Most leading structural alignment algorithms are accessible through multiple interfaces. DALI offers a web server for database searches and pairwise comparisons, with the entire PDB pre-computed for similarity searches [41]. The FATCAT algorithm is implemented in the RCSB PDB's pairwise structure alignment tool as both jFATCAT-rigid and jFATCAT-flexible, providing user-friendly access to both modes [22]. TM-align is available as downloadable standalone software in both C++ and Fortran implementations, facilitating integration into high-throughput structural bioinformatics pipelines [43]. CE is accessible through web servers including the CE-MC multiple structure alignment server and the RCSB PDB interface [44] [22].

Application Guidelines for Research and Development

Algorithm Selection Based on Research Objectives

Choosing the appropriate structural alignment algorithm depends heavily on the specific research question and protein systems under investigation:

For Detecting Remote Homology and Evolutionary Relationships: DALI and CE provide robust performance for identifying evolutionarily related proteins through their focus on structural conservation patterns [28].

For Analyzing Proteins with Conformational Flexibility: FATCAT is uniquely suited for comparing structures that undergo domain movements, hinge bending, or other structural rearrangements, as it explicitly accommodates flexibility through introduced twists [42] [22].

For Fold Recognition and Structural Classification: TM-align excels at detecting global topological similarity, making it ideal for categorizing proteins into fold classes and for rapid database searches [38] [43].

For Handling Topological Variations: CE-CP (Combinatorial Extension with Circular Permutations) specifically addresses proteins related by circular permutations or different connectivity patterns [22].

Interpretation of Key Metrics and Scores

Proper interpretation of alignment metrics is crucial for drawing biologically meaningful conclusions:

TM-score: Values range between 0 and 1, where scores <0.2 indicate randomly unrelated proteins, and scores >0.5 generally assume the same fold in SCOP/CATH classification systems [43] [22].

RMSD: Lower values indicate better geometric superposition, but RMSD is highly sensitive to alignment length and should always be interpreted in conjunction with the number of aligned residues.

Equivalent Residues: Represents the size of the structurally conserved core, with larger values indicating more extensive structural similarity.

Sequence Identity: Provides context for the evolutionary distance between proteins, with structural alignment often revealing relationships even when sequence identity falls below 10%.

Structural alignment algorithms have revolutionized our ability to detect deep evolutionary relationships and functional similarities that remain invisible to sequence-based methods. As structural biology continues to generate experimental data at an accelerating pace, these computational tools will play an increasingly vital role in unlocking the functional secrets encoded in protein three-dimensional structures.

The fundamental challenge in protein bioinformatics is detecting evolutionary and functional relationships when sequence similarity becomes minimal. Traditional sequence-based methods like BLAST, while revolutionary, quickly lose sensitivity as evolutionary distance increases. The field has progressively addressed this limitation through an evolutionary trajectory of methodologies: from sequence-sequence comparisons (BLAST), to profile-sequence methods (PSI-BLAST), to profile-profile alignment tools (COMPASS), and ultimately to HMM-HMM comparisons (HHsearch). This guide objectively compares these advanced sequence-based methods, framing their development and performance within the broader context of structural versus sequence alignment for protein comparison research. Understanding this hierarchy is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal tool for detecting remote homologies, which is often a critical step in functional annotation and target identification.

The transition between these methodological classes represents a continuous effort to extract more signal from diminishing sequence similarity. Profile-based methods leverage the evolutionary information contained in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) of protein families, which describe the conservation of amino acids across homologs [45]. The core innovation lies in moving beyond comparing single sequences to comparing the consensus and variation patterns of entire protein families. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methods, detailing their experimental protocols, performance metrics, and practical applications in modern bioinformatics pipelines.

Methodological Foundations and Evolutionary Trajectory

From Sequence-Search to Profile-Based Comparisons

The earliest methods for protein comparison performed simple sequence-sequence alignment using tools like BLAST or FASTA [45]. These methods are effective for detecting clear homologs but fail when sequences diverge beyond a certain threshold. A significant advance came with profile-sequence methods like PSI-BLAST (Position-Specific Iterated BLAST), which iteratively builds a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) from a multiple sequence alignment of significant hits and uses this profile to search the database again, detecting more distant relatives [45] [46].

A more sensitive approach involves profile-profile comparison, which directly measures the similarity between two MSAs. Early tools in this category included COMPASS and PROF-SIM [45] [47]. COMPASS, for instance, derives numerical profiles from alignments, constructs optimal local profile-profile alignments, and analytically estimates E-values for the detected similarities [47] [48]. Its scoring system and E-value calculation are based on a generalization of the PSI-BLAST approach adapted for the profile-profile case [47].

The HMM-HMM Revolution: HHsearch

The most sophisticated evolution in this trajectory is HMM-HMM alignment, exemplified by HHsearch [45]. Instead of using simple profiles, HHsearch represents each protein family as a Hidden Markov Model (HMM), a probabilistic model that captures not only amino acid emission probabilities at each position but also the transition probabilities between match, insert, and delete states [45]. This provides a more nuanced model of the protein family's evolutionary constraints.

HHsearch operates by aligning two HMMs using a modified Viterbi algorithm to find the optimal path through the pair-HMM state space [45]. The scoring function for aligning two columns from query and template HMMs incorporates both the log-sum-odds score and additional terms for secondary structure similarity and long-range correlations. The algorithm uses five dynamic programming matrices corresponding to different pair states to handle the complexity of the alignment [45]. The incorporation of predicted secondary structure elements, scored using statistical scores derived by the authors, further enhances its sensitivity for detecting remote homologs [45].

Table 1: Key Methodological Transitions in Protein Comparison

| Method Type | Representative Tools | Core Innovation | Data Input | Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Sequence | BLAST, FASTA | Pairwise sequence alignment | Single sequence | E-value, bit score |

| Profile-Sequence | PSI-BLAST | Iterative profile building | Single sequence | PSSM, E-values |

| Profile-Profile | COMPASS, PROF-SIM | Alignment-to-alignment comparison | Multiple Sequence Alignment | E-value, alignment score |

| HMM-HMM | HHsearch, HHblits | Probabilistic model comparison | HMMs built from MSAs | Probability, E-value |

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Comparison

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

The performance of homology detection methods is typically evaluated using datasets with known ground truth, such as SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins) or CATH, which provide hierarchical classifications of protein domains based on evolutionary and structural relationships [45]. A standard protocol involves:

- Dataset Curation: Using a curated set of protein sequences with low sequence identity (e.g., SCOP-20, with ≤20% sequence identity) to avoid bias [45].

- Homology Definition: Defining true positives (TPs) as domain pairs within the same SCOP superfamily and true negatives (FPs) as pairs from different SCOP classes [45]. Alternative definitions based on structural similarity (e.g., MaxSub score ≥0.1) can also be employed [45].

- Performance Metrics: Generating true positive (TP) vs. false positive (FP) curves across all-against-all comparisons and calculating the proportion of homologs detected at fixed error rates [45].

- Alignment Quality Assessment: Superimposing 3D structures based on sequence alignments and computing scores like MaxSub or Sbalance, which measure spatial agreement [45].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

In a comprehensive benchmark described in the HHsearch publication, multiple methods were evaluated on their ability to detect homologs within the SCOP-20 dataset [45]. The results demonstrated a clear hierarchy of sensitivity:

Table 2: Homolog Detection Performance at 10% Error Rate (Adapted from [45])

| Method | Category | Approximate Homologs Detected | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Sequence-Sequence | ~22% | Speed, simplicity for close homologs |

| PSI-BLAST | Profile-Sequence | Better than BLAST | Iterative search, database size |

| HMMER | HMM-Sequence | Better than PSI-BLAST | Probabilistic foundations |

| COMPASS | Profile-Profile | Better than HMMER | Sensitive for remote homologs |

| HHsearch0 | Basic HMM-HMM | Better than COMPASS | Foundation for advanced variants |

| HHsearch4 | Full HMM-HMM | Best performance | Incorporates secondary structure |

The benchmark further revealed that methods incorporating evolutionary and structural information show particularly dramatic improvements when detecting the most challenging remote homologs (pairs from different families) [45]. When evaluating alignment quality using metrics like MaxSub and Sbalance, the hierarchy generally held, with HHsearch variants incorporating secondary structure (HHsearch3 and HHsearch4) producing the most accurate alignments for distant homologs, which is crucial for reliable homology modeling [45].

The Structural Alignment Context

While advanced sequence methods push the boundaries of homology detection, structural alignment remains the gold standard for establishing evolutionary relationships when sequence similarity is undetectable. Structure alignment algorithms like TM-align and FATCAT operate on fundamentally different principles [43] [22].

TM-align is a sequence-independent algorithm that generates optimized residue-to-residue alignment based on structural similarity using heuristic dynamic programming iterations [43]. It returns a TM-score, which scales structural similarity between 0 and 1, where 1 indicates a perfect match. Scores below 0.2 suggest unrelated proteins, while scores above 0.5 generally indicate the same fold [43]. The FATCAT (Flexible structure AlignmenT by Chaining Aligned fragment pairs allowing Twists) algorithm offers both rigid-body and flexible alignment, the latter of which introduces twists to accommodate conformational changes between compared structures [22].

These tools are invaluable for validating predictions made by sensitive sequence-based methods like HHsearch, especially when they confidently group domains from different superfamilies or folds [45]. The convergence of evidence from both sequence-based and structure-based approaches provides the strongest foundation for inferring deep evolutionary relationships and functional annotations.

The Modern Toolkit: Integrated Approaches and Research Reagents

Contemporary protein function prediction pipelines, such as the one that excelled in the Critical Assessment of Function Annotation (CAFA), leverage a three-level hierarchical approach combining complementary methods [46]:

- Profile-Sequence Alignment (PSI-BLAST): For detecting clear homologs in databases like SwissProt.

- Profile-Profile Alignment (HHSearch): For gathering remote homologs from domain databases like Pfam.

- Domain Co-Occurrence Networks (DCN): For ab initio function prediction when no homology is detectable, based on contextual genomic information [46].

This integration "effectively increased the recall of function prediction while maintaining a reasonable precision" and is particularly adept at handling multi-domain proteins [46].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Comparison Studies

| Research Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCOP / CATH Databases | Classification Database | Provide ground truth for fold/superfamily for benchmarking | SCOP, CATH |

| Pfam Database | Protein Family Database | Source of curated multiple sequence alignments and HMMs | Pfam [46] |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Structure Repository | Source of 3D coordinates for structure validation and comparison | RCSB PDB [22] |

| SwissProt Database | Annotated Sequence Database | High-quality source of sequences and functional annotations | SwissProt [46] |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Data Structure | Input for building profiles and HMMs; represents evolutionary history | Generated by tools like PSI-BLAST, HHblits |

| Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) | Data Structure | Profile representation used by PSI-BLAST for sensitive search | Generated by PSI-BLAST |

| Hidden Markov Model (HMM) | Probabilistic Model | Enhanced profile with state transitions; input for HHsearch | Generated by tools like HHblits, HMMER |

Experimental Workflow and Visualization

The typical workflow for detecting remote homologs using the most sensitive methods involves a multi-step process that transforms sequence data into increasingly informative comparative models. The following diagram illustrates the key stages from initial sequence input to final homology assessment:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Remote Homology Detection

A critical experimental protocol in benchmarking these methods is the all-against-all comparison on a curated dataset like SCOP-20, which allows for the calculation of sensitivity and precision. The following workflow details this evaluation process:

Diagram 2: Protein Comparison Method Benchmarking

The evolution from PSI-BLAST to HHsearch represents a fundamental shift in how we detect protein relationships, moving from comparing sequences to comparing evolutionary histories encapsulated in profiles and HMMs. The experimental data clearly demonstrates that HMM-HMM comparison methods, particularly those incorporating secondary structure like HHsearch, provide superior sensitivity for detecting remote homologs and generating accurate alignments compared to profile-sequence or sequence-sequence methods [45].

Nevertheless, the most effective modern approaches combine these sensitive sequence-based methods with structural validation and other contextual information like domain co-occurrence networks [46]. For researchers in drug development and functional genomics, this integrated strategy offers the most powerful framework for annotating the ever-growing universe of protein sequences, ensuring that even the most evolutionarily distant relationships can be uncovered to drive biological discovery and therapeutic innovation.

In the field of protein science, comparing proteins to identify evolutionary, functional, or structural relationships is a fundamental task. Two primary computational approaches exist for this purpose: sequence-based alignment and structure-based alignment. Sequence-based methods, which include tools like BLAST and ClustalW, identify similarities by aligning the primary amino acid sequences of proteins. In contrast, structure-based methods, such as TM-align and MADOKA, compare the three-dimensional spatial arrangements of protein structures. While sequence comparison has been the traditional workhorse due to its computational efficiency, structural alignment can reveal deep evolutionary relationships that persist even when sequence similarity has faded to undetectable levels. The exponential growth of protein structure databases, fueled by advances in AI-based prediction tools like AlphaFold, has made structural comparison increasingly accessible and critical for modern research. This guide provides an objective framework for selecting the optimal protein comparison tool based on specific research scenarios, particularly in drug discovery and functional annotation.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data Analysis

Accuracy and Speed Benchmarks

The performance of alignment tools varies significantly across different metrics. The following table summarizes experimental data from large-scale benchmark studies evaluating common software.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Alignment Tools

| Tool | Alignment Type | Average Precision | Relative Speed | Key Strength | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARST2 [49] | Structure | 96.3% | Very High (Fastest) | Accuracy & efficiency | Massive database searches |

| Foldseek [49] | Structure | 95.9% | High | Speed with good accuracy | Large-scale structural searches |

| TM-align [50] [49] | Structure | 94.1% | Moderate | Robustness, interface alignment | General-purpose structural alignment |

| MAMMOTH [40] | Structure | High (Specific value not reported) | Moderate | Reliability at low sequence identity | Challenging, low-similarity alignments |

| MUSTANG [40] | Structure | High (Specific value not reported) | Moderate | Handling of distantly related proteins | Multiple structure alignment |

| BLAST [49] | Sequence | Lower than structure-based | High (Sequence-based) | Established, fast for clear homologs | Initial sequence similarity search |

| MADOKA [51] | Structure | High TM-score | Very High | Ultra-fast similarity searching | Rapid structural neighbor identification |

Performance in Critical Research Scenarios

Tool performance is highly dependent on the research context. The data below highlights how different tools perform under specific, common research challenges.

Table 2: Tool Performance in Specific Research Scenarios

| Research Scenario | Performance Finding | Implication for Tool Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Low Sequence Identity (<30%) [40] | Structure-based methods (e.g., MAMMOTH, MATRAS) show significantly higher accuracy than sequence-based methods. | Structural alignment is essential for detecting distant evolutionary relationships. |