Protein Crystallization for Beginners: A 2025 Guide from Principles to Practice

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to the protein crystallization process, a critical step in X-ray crystallography for determining 3D protein structures.

Protein Crystallization for Beginners: A 2025 Guide from Principles to Practice

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive introduction to the protein crystallization process, a critical step in X-ray crystallography for determining 3D protein structures. Tailored for researchers and professionals in drug discovery, it covers foundational principles, from the importance of sample purity and stability to an overview of standard methods like vapor diffusion. It then delves into practical troubleshooting for common challenges and explores how modern automation, AI, and complementary techniques are revolutionizing the field. The article synthesizes established methodologies with the latest 2025 advancements, offering a clear pathway for beginners to approach and succeed in their crystallization experiments.

The What and Why: Understanding Protein Crystallization Fundamentals

Defining Protein Crystallization and Its Role in Structural Biology

Protein crystallization is the process of forming a highly ordered, three-dimensional array of protein molecules stabilized by crystal contacts [1]. This process serves as the critical gateway to X-ray crystallography, the predominant method for determining the high-resolution three-dimensional structures of biological macromolecules [2] [3]. The knowledge of these atomic-scale structures is fundamental to understanding biological function and is instrumental in fields such as drug development [4].

The indispensability of structural knowledge

Understanding the precise three-dimensional structure of a protein is crucial for elucidating its mechanism of action, including how it interacts with other molecules, substrates, and drugs [4]. Crystal-based diffraction methods are responsible for approximately 85-90% of all biomolecular structural models deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), the worldwide repository for atomic-level structural data [3] [5] [6]. This dominance underscores the technique's unparalleled importance in modern structural biology.

The following table compares the primary methods used in structural biology.

Table 1: Key Structural Biology Methods for Macromolecular Structure Determination

| Method | Primary Use | Approximate PDB Share | Key Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Determining atomic-level 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and viruses [2]. | ~85-90% [3] [5] | High-quality, well-ordered single crystals [2]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Studying protein structures and dynamics in solution [5]. | ~14% [5] | Proteins must be soluble and not too large. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Determining structures of large complexes and membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize [4]. | Growing share | A thin, vitrified layer of the sample in solution [4]. |

The theory and practice of protein crystallization

The thermodynamic principle

At its core, protein crystallization is a thermodynamic process aimed at achieving a supersaturated solution, where the protein concentration exceeds its equilibrium solubility [2] [1]. In this metastable state, the dissolved protein molecules begin to self-organize into a crystal lattice, a process governed by the need to lower the system's overall free energy (ΔG) by forming stable, low-energy intermolecular contacts, despite an associated decrease in entropy [1]. The process occurs in two critical steps:

- Nucleation: The initial formation of a small, stable aggregate of protein molecules that acts as a template for the crystal.

- Crystal Growth: The subsequent, ordered addition of protein molecules to the nucleus, leading to the formation of a macroscopic crystal [1].

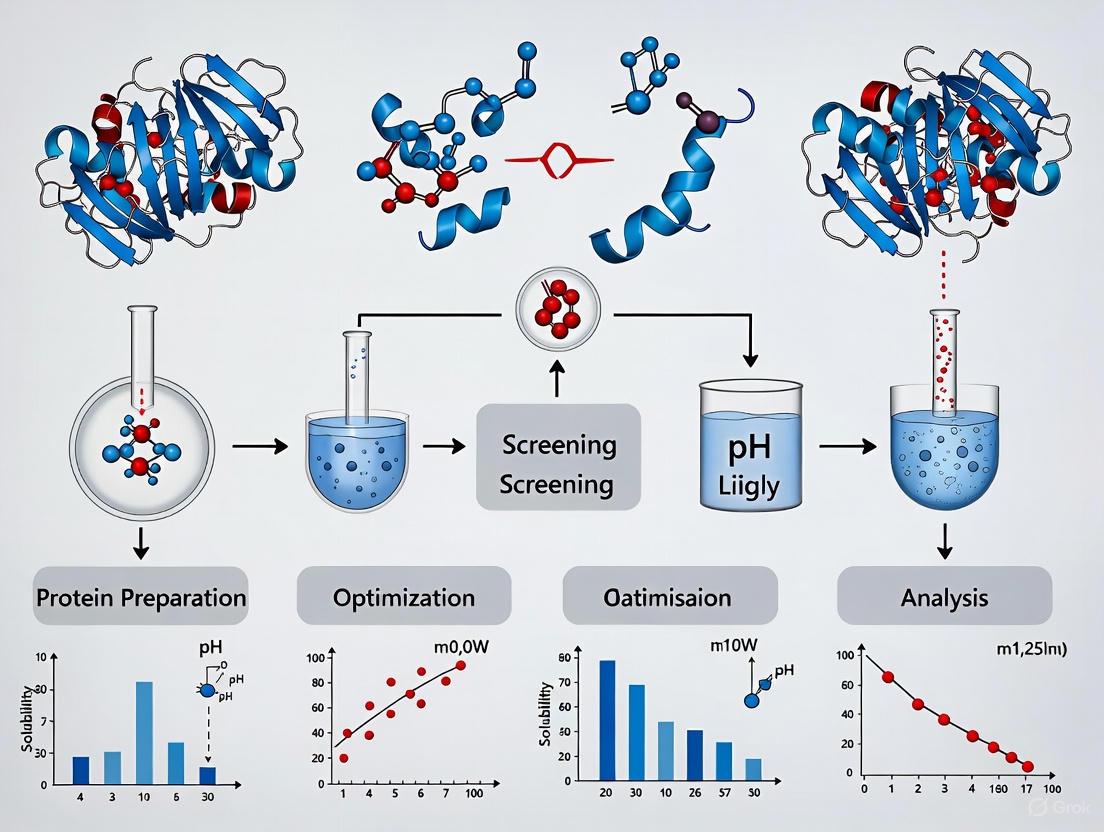

A practical workflow for structure determination

The journey from a protein of interest to a refined three-dimensional structure involves a series of critical, interconnected steps, summarized in the workflow below.

Essential reagents for crystallization trials

Successful crystallization depends on creating a chemical environment that promotes the orderly association of protein molecules. The following table details key reagents used in formulating crystallization conditions.

Table 2: Key Reagents in Protein Crystallization

| Reagent Category | Examples | Primary Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Ammonium Sulfate, 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) | Reduce protein solubility by excluding water (PEGs) or competing for hydration (salts), driving the solution toward supersaturation [3] [1] [7]. |

| Buffers | HEPES, Tris, MES | Maintain a stable pH, which critically influences the ionization state of surface residues and their potential for forming crystal contacts [3] [8]. |

| Salts | Sodium Chloride, Magnesium Chloride, Ammonium Sulfate | Modulate electrostatic interactions between protein molecules; at high concentrations, they can "salt out" the protein [3] [8]. |

| Additives | Metal Ions, Ligands, Substrates, Reducing Agents (DTT, TCEP) | Enhance protein stability, lock specific conformations, or mediate specific intermolecular contacts in the crystal lattice [2] [3]. |

Methodologies in protein crystallization

Several experimental methods are employed to gently drive a protein solution to supersaturation. The most common and widely used techniques are based on vapor diffusion.

Vapor diffusion methods

Vapor diffusion is the cornerstone of modern protein crystallization [1] [7]. In this method, a small droplet containing a mixture of purified protein and precipitant solution is sealed in an enclosure with a larger reservoir of a solution containing a higher concentration of precipitant. Water slowly evaporates from the droplet and diffuses to the reservoir until the vapor pressure equilibrates. This gradual process increases the concentration of both the protein and the precipitant in the droplet, guiding the solution into a supersaturated state ideal for crystal nucleation and growth [1] [7]. The two primary setups are:

- Hanging Drop: The protein-precipitant droplet is suspended from a coverslip over the reservoir [8].

- Sitting Drop: The droplet rests on a small pedestal or ledge separated from the reservoir [1].

The physical setup of these two methods is illustrated below.

Other crystallization techniques

While vapor diffusion is most prevalent, other methods are valuable for specific applications:

- Batch Crystallization: The protein is directly mixed with a precipitant to achieve immediate supersaturation, and the mixture is left undisturbed for crystals to form [4]. This method is often performed under oil to prevent evaporation [1].

- Microdialysis: The protein solution is separated from a larger precipitant solution by a semi-permeable membrane. Small molecules and ions diffuse across the membrane, slowly changing the chemical environment of the protein to induce crystallization [1].

- Free-Interface Diffusion: Solutions of protein and precipitant are brought into contact without mixing, allowing crystallization to occur at the interface where the two solutions diffuse into one another [1].

Guiding principles and current innovations

Biochemical prerequisites for success

The likelihood of successful crystallization is heavily dependent on the quality and stability of the protein sample itself. Key prerequisites include:

- High Purity: Samples should typically be >95% pure, as impurities can disrupt the uniform packing of molecules required for a crystal lattice [3] [8].

- Homogeneity and Monodispersity: The protein must be conformationally uniform and exist as a single oligomeric species in solution. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) are key techniques for assessing this [3].

- Stability: The protein must remain stable and folded for the duration of the crystallization experiment, which can take days to months [3]. Buffer components, salts, and additives like reducing agents (e.g., TCEP) are often included to maintain stability [3].

- Construct Design: Modern tools like AlphaFold can guide the design of protein constructs by identifying and removing flexible regions that introduce heterogeneity and hinder crystallization [3].

Key parameters influencing crystallization

Crystallization is influenced by a multitude of interconnected factors that must be empirically optimized for each unique protein. The most critical parameters to screen include [7]:

- pH: Dramatically affects the surface charge and bonding potential of the protein. Crystallization often occurs near the protein's isoelectric point (pI) [3] [1].

- Temperature: Alters protein solubility and kinetics of crystal growth. Trials are often conducted at both 4°C and 20°C [1].

- Protein Concentration: Must be high enough to reach supersaturation but not so high as to cause immediate, amorphous precipitation [7].

- Precipitant Type and Concentration: The nature and concentration of the precipitant are primary drivers of supersaturation [3].

- Additives and Ligands: Ions, substrates, or inhibitors can stabilize specific conformations and mediate crucial crystal contacts [2] [3].

Emerging trends and rational design

The field is evolving from a purely empirical endeavor toward a more rational science. Notable innovations include:

- High-Throughput Robotics: Automation allows researchers to set up thousands of crystallization trials with nanoliter volumes of protein, drastically increasing the speed and efficiency of screening [2] [7].

- Advanced Computational Prediction: Machine learning models and tools like DSDCrystal are being developed to predict a protein's crystallization propensity based on its dynamic and physico-chemical features, guiding experimental efforts [9] [6].

- Surface Engineering: Techniques like surface entropy reduction (SER) involve mutating large, flexible surface residues to smaller ones (e.g., lysine to alanine) to create patches conducive to forming crystal contacts [3] [6].

Protein crystallization remains the foundational pillar of structural biology, enabling the visualization of biological macromolecules at an atomic level. While the process presents significant challenges, its principles are well-established, revolving around the careful manipulation of a protein's solution environment to foster spontaneous self-assembly into an ordered crystal. Continued advancements in automation, computational prediction, and rational protein engineering are steadily increasing the success rate and expanding the frontiers of this indispensable technique, solidifying its central role in driving discovery in basic research and drug development.

Why Crystallize? The Critical Link to X-ray Crystallography and Drug Discovery

Protein crystallization represents a fundamental prerequisite for X-ray crystallography, a technique responsible for determining approximately 86% of the macromolecular structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [10]. This method enables researchers to elucidate the three-dimensional structure of biological macromolecules at atomic resolution, providing a deep and unique understanding of protein function and the inner workings of living cells [10]. The process of transforming proteins from a disordered solution into a highly ordered crystalline state creates a repeating lattice that can diffract X-rays, allowing scientists to deduce the precise spatial arrangement of atoms within the protein [11]. This structural information has become indispensable in modern drug discovery, particularly for understanding drug-target interactions at the molecular level and facilitating the development of targeted therapies [12] [13].

The critical importance of protein crystallization is reflected in its growing market impact, with the global protein crystallization market projected to increase from $1.84 billion in 2023 to $3.84 billion by 2033, registering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.5% [14]. This growth is driven by rising investments in biopharmaceutical research and development and the expanding use of protein therapies for treating various diseases [14]. As the demand for novel therapeutics escalates, the tools and technologies supporting protein crystallization are positioned for robust expansion, reflecting the necessity for precise structural insights in complex biological systems [12].

The Science of Protein Crystallization: From Principle to Practice

Fundamental Principles

The process of protein crystallization requires bringing the macromolecule to a state of supersaturation, where the solution contains a higher protein concentration than its equilibrium solubility [10]. This is typically achieved by concentrating the protein sample to the highest possible concentration without causing aggregation or precipitation (usually 2-50 mg/mL) and introducing it to a precipitating agent that promotes the nucleation of protein crystals in the solution [10]. The crystallization process can be understood through phase diagrams that map the relationship between protein concentration and precipitant concentration, identifying zones where the solution is undersaturated, metastable (where crystal growth occurs), or labile (where spontaneous nucleation happens) [10].

The homogeneity of the protein preparation is a key factor in obtaining crystals that diffract to high resolution [10]. Proteins must be purified to homogeneity, or as close as possible to homogeneity, before crystallization attempts can begin. Even minor impurities can disrupt the orderly packing of protein molecules into a crystal lattice, preventing the formation of diffraction-quality crystals. This requirement for extreme purity makes protein production and purification critical preliminary steps in the crystallography pipeline [11].

Key Crystallization Techniques

Several experimental approaches have been developed to achieve the controlled supersaturation necessary for protein crystallization:

Vapor Diffusion (Hanging Drop and Sitting Drop): In vapor diffusion, a drop containing a mixture of precipitant and protein solutions is sealed in a chamber with pure precipitant [10]. Water vapor then diffuses out of the drop until the osmolarity of the drop and the precipitant are equal. The dehydration of the drop causes a slow concentration of both protein and precipitant until equilibrium is achieved, ideally in the crystal nucleation zone of the phase diagram [10]. In the hanging drop method, the protein-precipitant mixture is suspended from a cover slide above the reservoir, while in the sitting drop method, the mixture is placed on a small platform or shelf within the well.

Batch Crystallization under Oil: This method relies on bringing the protein directly into the nucleation zone by mixing the protein with the appropriate amount of precipitant [10]. This method is usually performed under a paraffin/minimal oil mixture to prevent the diffusion of water out of the drop, maintaining constant conditions throughout the crystallization experiment [10].

Microbatch Crystallization: A modern variation of batch crystallization conducted in 96-well trays where small volumes (typically 1-2 μL) of protein and precipitant solutions are mixed under oil to prevent evaporation [10]. This approach enables high-throughput screening of crystallization conditions with minimal reagent consumption.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Protein Crystallization Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Drop Vapor Diffusion | Slow equilibration through vapor phase | Allows gradual approach to supersaturation; widely used | Initial screening; optimization |

| Sitting Drop Vapor Diffusion | Equilibration from elevated platform | Reduced surface contact; better for automated systems | High-throughput screening |

| Batch Crystallization | Direct mixing to supersaturation | Simplified setup; constant conditions | Known conditions; membrane proteins |

| Microbatch under Oil | Small-volume mixing under oil | Minimal reagent use; high-throughput | Sparse matrix screening; precious samples |

The Crystallization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete protein crystallization and structure determination workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful protein crystallization requires specialized reagents, equipment, and consumables. The market for these tools continues to expand, with consumables representing the largest product segment in the protein crystallization market [14]. The following table details essential components of the protein crystallization toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Crystallization

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Protein Sample | Macromolecule for crystallization | High purity (>95%); concentration 5-50 mg/mL; filtered through 0.22 μm filter [10] |

| Crystallization Screens/Kits | Sparse matrix incomplete factorial screening | Commercial screens (Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions); PEG-based, ammonium sulfate conditions [10] |

| Precipitating Agents | Induce supersaturation | Polyethylene glycol (PEG), ammonium sulfate (account for ~60% of successful conditions) [10] |

| Buffers | Control pH environment | NaOAc (pH 4.0-4.9), HEPES, Tris; various pH ranges to optimize crystallization [10] |

| Salts and Additives | Modify chemical environment | NaCl (0.6-1.6 M concentrations); cations, anions, and small molecules that promote ordering [10] |

| Crystallization Plates | Platform for crystallization experiments | 24-well hanging/sitting drop trays; 96-well microbatch trays; Corning CrystalEX Microplates [10] [14] |

| Liquid Handling Systems | Precise dispensing of small volumes | Automated systems for high-throughput screening; minimize human error [15] |

| Imaging Systems | Monitor crystal growth | Automated crystal imaging systems; document drop morphologies over time [15] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and equipment is crucial for successful crystallization. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) followed by ammonium sulfate are the most commonly successful precipitating agents, accounting for approximately 60% of all recorded macromolecular precipitants used for crystallization [10]. Commercial screens that exploit the sparse matrix incomplete factorial method of trial conditions provide an efficient starting point for initial crystallization trials of new proteins [10].

Applications in Drug Discovery: From Structure to Function

Enabling Rational Drug Design

X-ray crystallography provides the structural basis for rational drug design by revealing atomic-level details of protein-ligand interactions [13]. When the three-dimensional structure of a therapeutic target is known, researchers can design molecules that precisely fit into binding pockets, optimizing interactions for higher affinity and specificity. This structure-based approach has revolutionized drug discovery, particularly for targets where natural products serve as starting points for drug development [13].

Natural products have often been viewed as "privileged structures" in drug discovery, which may be attributable to evolution driving biological activity irrespective of molecular structure [13]. Analysis of drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 1981 to 2019 shows that nearly 30% of clinical drugs come from natural products or natural product derivatives [13]. The dual characteristics of evolution-driven bioactive property and unique chemical structure make natural products valuable leads in drug discovery [13].

Case Studies: Successful Drugs Developed Through Crystallography

Several blockbuster drugs have been developed using structural information obtained through X-ray crystallography:

Taxol/Paclitaxel: This natural product anticancer drug binds to tubulin, stabilizing microtubules and preventing cell division [13]. The co-crystal structure of tubulin with taxol provided insights into its mechanism of action and has guided the development of analogs with improved therapeutic properties.

Rapamycin (Sirolimus): Originally discovered as an antifungal antibiotic, rapamycin's complex with FKBP12 was determined through X-ray crystallography [13]. This structural information revealed its unique mechanism as a molecular glue that forms a complex with mTOR, leading to its development as an immunosuppressant and anticancer agent [13].

Artemisinin: This natural product antimalarial, discovered by Nobel laureate Tu Youyou, has saved millions of lives [13]. Structural studies have helped elucidate its mechanism of action and guided the development of more stable derivatives.

Berberine: A natural product with multiple therapeutic applications, berberine's complex with phospholipase A2 was determined at 1.93Å resolution, providing a rationale for its anti-inflammatory activity [13].

The following diagram illustrates how structural information enables the drug discovery and optimization process:

Market Impact and Therapeutic Areas

The critical role of protein crystallization in drug discovery is reflected in market trends and investment patterns. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies represent the largest end-user segment of the protein crystallization market, utilizing these techniques for drug discovery and protein engineering [12] [14]. The fastest-growing application segment in terms of revenue is in drug discovery and development, driven by the increasing demand for precision medicine and biologics in targeted therapies, which rely heavily on detailed structural insights from crystallographic data [12].

The expanding focus on protein therapeutics has significantly contributed to market growth. Biopharmaceuticals offer targeted treatments for chronic conditions, leveraging protein crystallization for precise protein structure determination, yielding effective and stable therapeutics [15]. Investments in research and development, such as Australia's $4.34 billion allocation in 2022-23, underline the sector's influence on market acceleration [15].

Table 3: Protein Crystallization Market Analysis by Segment and Region

| Segment | Market Size/Share | Growth Trends | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Market | $1.84B (2023) to $3.84B (2033) [14] | CAGR 8.5% (2025-2033) [14] | Demand for protein therapeutics; biopharmaceutical R&D [14] |

| Product Type (Consumables) | Largest revenue share [14] | Recurrent revenue stream | Need for reagents, kits, microplates for screening [14] |

| Technology (X-ray Crystallography) | Largest market share [14] | Sustained dominance | High resolution; well-established methodology [12] |

| End User (Pharma/Biotech) | Largest market share [14] | Strong growth | Targeted drug development; structural biology applications [12] |

| Region (North America) | 40% market share [12] | CAGR 8.1% [14] | Advanced research facilities; drug development funding [12] |

| Region (Asia-Pacific) | 20% market share [12] | Fastest-growing (CAGR 8.8%) [14] | Expanding biotechnology sectors; increasing healthcare investment [12] [14] |

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

Technological Advancements

The field of protein crystallization is being transformed by several cutting-edge technologies that are addressing traditional challenges and expanding capabilities:

Automation and High-Throughput Screening: Enhanced robotic systems streamline the crystallization process, improving efficiency and reproducibility while reducing manual labor [12]. Automated liquid handling systems can rapidly set up thousands of crystallization trials with minimal protein consumption.

Microfluidics and Miniaturization: Miniaturized techniques allow for high-throughput screening and reduced reagent use, accelerating discovery and enabling work with scarce protein samples [12]. These systems can manipulate nanoliter volumes, dramatically reducing consumption of precious protein samples.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI-driven algorithms optimize crystallization conditions and predict outcomes, reducing trial-and-error approaches [12]. Machine learning models can analyze historical crystallization data to recommend promising conditions for new targets.

Advanced Imaging and Analysis: Improved crystallization imaging systems coupled with sophisticated software enable automated crystal detection and monitoring [15]. These systems can detect early crystal formation and track growth kinetics without manual intervention.

Cell-Free Protein Crystallization: Innovative methods, such as that developed by the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 2022, represent groundbreaking approaches that offer improved crystallization processes for structural biology and drug discovery [15]. This technique enables the study of unstable proteins that are not amenable to investigation using conventional methods [14].

Addressing Challenges and Limitations

Despite significant advances, protein crystallization remains a bottleneck in structural biology due to several persistent challenges:

Membrane Protein Complexity: Membrane proteins pose significant challenges in terms of purification and crystallization [14]. Several proteins in this category, such as transmembrane receptors and ion channels, are highly intriguing regarding drug development but difficult to crystallize [14].

Sample Requirements: The technique requires relatively large amounts (milligrams) of pure protein, and for each protein of interest, a large number of crystallization conditions must be tried [11]. Producing high-quality crystals from proteins beyond well-characterized examples remains challenging [14].

Dynamic and Flexible Proteins: Proteins with inherent flexibility or multiple conformations often resist crystallization because they lack the rigid structure needed to form ordered lattices.

The scientific community is addressing these challenges through collaborative efforts, shared resources, and technological innovations. As these barriers are overcome, the application of protein crystallization in drug discovery will continue to expand, enabling the development of novel therapeutics for an increasingly diverse range of biological targets.

Protein crystallization serves as the critical gateway to atomic-resolution structure determination through X-ray crystallography, providing indispensable insights for modern drug discovery. The process, while sometimes considered more art than science, has been systematically improved through technological advancements in automation, miniaturization, and computational approaches. As the field continues to evolve, protein crystallization remains foundational to understanding biological function at the molecular level and developing targeted therapies for human disease. The continued growth of the protein crystallization market, driven by demand for protein therapeutics and biopharmaceutical innovation, underscores its enduring importance in structural biology and drug development. For researchers entering the field, mastering the principles and techniques of protein crystallization provides access to a powerful toolkit for elucidating biological mechanisms and advancing human health.

Protein crystallization is a pivotal technique in structural biology, enabling the determination of three-dimensional protein architectures that are essential for understanding function, studying interactions, and guiding drug discovery [16] [17]. Despite its importance, the process of growing high-quality protein crystals remains challenging and is often characterized by trial and error rather than predictable outcomes [18]. At the heart of understanding and controlling this process lies the protein-water phase diagram, which maps the thermodynamic conditions under which a protein solution transitions between different physical states [18]. For researchers beginning investigations in this field, mastering the interpretation and navigation of this phase diagram is fundamental to achieving reproducible and diffraction-quality crystals.

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of protein crystallization through the lens of phase diagram principles. It is structured to lead beginner researchers from core theoretical concepts to practical experimental methodologies, emphasizing how a rational approach to phase behavior can dramatically increase crystallization success rates [19]. By establishing a firm foundation in these core principles, researchers can transform crystal growth from an empirical art to a more predictable scientific process.

Theoretical Foundations of the Protein Phase Diagram

Essential Zones of the Phase Diagram

The phase diagram of a protein-water system graphically represents the relationship between protein concentration, precipitant concentration, and the resulting physical states of the solution. The characteristic features of this diagram can be captured by a relatively simple model with parameters describing interactions between protein molecules in both solution and crystalline states [18]. This model allows researchers to predict and identify optimal conditions for crystal growth. The diagram is typically divided into several key zones, each representing a distinct thermodynamic regime critical for understanding crystallization pathways [20]:

- Undersaturated Zone: At low concentrations of both protein and precipitant, the protein is completely soluble and remains in a homogeneous solution. No phase separation occurs under these conditions.

- Metastable Zone: At moderate supersaturation, the solution is thermodynamically primed for crystal growth, but spontaneous nucleation is unlikely. Existing crystals will grow, but new nuclei do not form. Crystals grown in this zone are often better ordered and yield higher diffraction quality than those from higher concentration regions [20].

- Nucleation Zone: At higher supersaturation, the solution becomes favorable for the spontaneous formation of crystal nuclei. This region often produces showers of small crystals, but controlling their size and quality can be challenging.

- Precipitation Zone: At very high concentrations, the protein forms amorphous aggregates rather than ordered crystals, resulting in irreversible and unproductive precipitation.

Table 1: Key Zones in the Protein Crystallization Phase Diagram

| Zone | Protein/Precipitant Concentration | Thermodynamic Behavior | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undersaturated | Low | Soluble, homogeneous solution | No phase separation |

| Metastable | Moderate | Supersaturated, no spontaneous nucleation | Crystal growth from existing nuclei; often produces highest quality crystals [20] |

| Nucleation | High | Spontaneous nucleation possible | Formation of new crystal nuclei; may yield many small crystals |

| Precipitation | Very High | Rapid, disordered aggregation | Amorphous, non-crystalline precipitate |

The Role of Supersaturation

The journey from a soluble protein to a crystalline solid begins with achieving supersaturation, the fundamental driving force behind crystallization [18]. A solution becomes supersaturated when the concentration of protein exceeds its equilibrium solubility under given conditions of precipitant concentration, temperature, and pH. This metastable state provides the thermodynamic potential for molecules to leave the solution phase and incorporate into a solid crystal lattice.

Creating a supersaturated state typically involves gradually reducing protein solubility through the careful addition of precipitating agents such as salts or polymers [21] [16]. These precipitants act by competing for water molecules (salting-out) or creating macromolecular crowding environments that effectively increase protein-protein interactions while decreasing protein-solvent interactions [21]. The trajectory of this process through the phase diagram must be carefully controlled, as moving too rapidly into high supersaturation often leads to irreversible precipitation rather than productive crystallization [18] [20].

Advanced Phase Behavior: Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation

An interesting phenomenon observed in some protein systems is metastable liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), where a protein solution separates into protein-rich and protein-poor liquid phases [22]. This creates a distinct region in the phase diagram where two liquid phases coexist, typically located within the supersaturated region above the crystal solubility curve. While LLPS is metastable with respect to crystallization, it can significantly enhance crystal nucleation through two proposed mechanisms: the wetting mechanism, where a protein-rich liquid layer lowers the interfacial energy of crystal nuclei, and the two-step mechanism, where crystal nucleation proceeds through intermediate liquid-like protein clusters [22].

Research on lysozyme has demonstrated that LLPS can be harnessed to dramatically improve crystallization yields. One study reported that combining a traditional salting-out agent (NaCl) with an organic buffer (HEPES) under LLPS conditions resulted in crystallization yields exceeding 90% at fairly low ionic strength within approximately one hour—more than three times the yield achieved without HEPES [22]. This suggests a promising strategy for enhancing crystallization of challenging proteins by strategically manipulating the phase diagram with multiple additives.

Experimental Determination of Phase Diagrams

Microbatch Method for Phase Diagram Mapping

The microbatch technique under oil is an efficient approach for rapidly determining the phase diagram of a target protein [20]. This method involves dispensing numerous small-volume trials (typically nanoliter to microliter scale) containing varying concentrations of protein and precipitant, then observing the outcomes after incubation. The procedure can be broken down into the following detailed protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a highly pure (>95%) and homogeneous protein sample in a stabilizing buffer. Assess monodispersity using dynamic light scattering (DLS) or size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to ensure the sample is aggregation-free [21].

- Experimental Design: Select a range of protein concentrations (e.g., 5-100 mg/mL) and precipitant concentrations (e.g., 0-30% PEG) that will adequately probe the different zones of the phase diagram.

- Dispensing: Using automated liquid handling or manual techniques, dispense trials with systematic variations of protein and precipitant concentrations into a microbatch plate. Each trial combines protein solution and precipitant solution in a defined ratio.

- Sealing and Incubation: Cover the trials with a layer of oil to prevent evaporation and incubate at a constant temperature for a defined period (days to weeks).

- Observation and Scoring: Regularly examine each trial under a microscope to identify clear drops (undersaturated), crystals (nucleation or metastable zone), or precipitate (precipitation zone).

- Diagram Construction: Plot the results on a graph with protein concentration on one axis and precipitant concentration on the other, delineating the boundaries between different zones based on experimental outcomes.

Table 2: Crystallization Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitating Salts | Ammonium sulfate, Sodium chloride | Competes for water molecules, reduces protein solubility (salting-out) [21] | Concentration-dependent effect; easily form insoluble salts with certain buffers [21] |

| Polymers | PEG 4000, PEG 8000 | Creates macromolecular crowding, excludes protein from solution [21] | Longer polymers generally more effective at lower concentrations [19] |

| Buffers | HEPES, Acetate, Tris | Controls pH, affects protein charge and electrostatic interactions [21] | Keep concentration below ~25 mM; avoid phosphate with certain salts [21] |

| Organic Additives | MPD, HEPES | Modifies hydration shell, binds hydrophobic regions, may stabilize crystals [21] [22] | HEPES can act as salting-out for crystallization while salting-in for LLPS [22] |

| Reducing Agents | DTT, TCEP, BME | Prevents cysteine oxidation, maintains protein stability [21] | Consider half-life at experimental pH (TCEP most stable) [21] |

Microseeding from Metastable Zone Conditions

Once the phase diagram is established, the identified metastable zone can be exploited through microseeding to produce high-quality crystals consistently [20]. This technique separates the nucleation and growth phases of crystallization, allowing each to be optimized independently:

- Seed Stock Preparation: Transfer a well-formed crystal to a harvesting buffer containing a precipitant concentration approximately 20% higher than the nucleation zone concentration.

- Crystal Crushing: Gently crush the crystal using a glass fiber or similar tool to create a suspension of microscopic seeds.

- Seed Serial Dilution: Prepare a series of dilutions (e.g., from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁴) in harvesting buffer to obtain an appropriate seed density.

- Seeded Crystallization Setup: Set up vapor diffusion trials with reservoir solutions containing precipitant at the metastable zone concentration determined from the phase diagram.

- Seed Introduction: Add a small volume (0.3 μL) of the seed dilution to the crystallization drops. The seeds will then grow in the metastable environment where spontaneous nucleation is unfavorable.

- Optimization: The 10⁻³ dilution typically provides the optimal seed density for producing large, single crystals. Fresh seed stocks should be used immediately as they lose effectiveness upon storage [20].

This approach was successfully applied to a bacterial enzyme that previously produced poorly diffracting crystals (≤3.5 Å). By employing microseeding based on a phase diagram determined via microbatch, researchers obtained crystals that diffracted to 2 Å resolution, demonstrating the power of this rational approach [20].

Rational Screening Based on Phase Behavior

Phase Diagram-Informed Screening Strategy

Traditional crystallization screening often employs generic sparse-matrix approaches that sample chemical space without considering the specific biophysical properties of the target protein. In contrast, a rational screening strategy based on detailed phase behavior knowledge has been shown to significantly increase success rates for challenging proteins [19]. This approach involves:

- High-Throughput Solubility Screening: Using microfluidics to perform hundreds of protein solubility experiments across diverse chemical conditions, identifying reagents that significantly affect protein aggregation behavior.

- Phase Diagram Generation: Constructing complete phase diagrams for the most promising reagents identified in the initial screen, mapping out solubility boundaries under each condition.

- Customized Screen Design: Designing individualized crystallization screens tailored to target the solubility boundary of the protein with each effective reagent.

This methodology was applied to 12 diverse and challenging proteins, most of which had failed to crystallize using traditional techniques. The phase diagram-based approach achieved a remarkable 75% crystallization success rate, with an overall diffraction success rate of approximately 33%—roughly double what was achieved with conventional automation in large-scale structural genomics consortia [19].

Key Factors Influencing Phase Behavior

Several biochemical parameters significantly impact protein phase behavior and should be carefully controlled during crystallization experiments:

- pH: Reagents with pH values near the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the target protein are identified as potential crystallizing agents with higher frequency, consistent with reduced intermolecular electrostatic repulsion near the pI [19]. The ideal pH is typically within 1-2 units of the protein's pI [21].

- Precipitant Properties: Longer-chain PEG polymers generally produce more crystallization hits than shorter polymers, with chemically modified PEGs (e.g., monomethyl ether end groups) showing different effectiveness depending on polymer size [19].

- Ionic Strength: Higher ionic strengths typically increase the number of identified crystallization reagents, though the effect is generally less pronounced than that of precipitant composition [19].

- Protein Quality and Concentration: High purity (>95%) and homogeneity are essential for crystallization success [21]. Both insufficient and excessive protein concentration can hinder crystallization, with the optimal range being protein-specific and determinable through pre-crystallization testing [21].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Automation and Advanced Imaging

Automation technologies are revolutionizing protein crystallization by increasing throughput, improving reproducibility, and enabling more precise phase diagram mapping. Integrated systems now combine laboratory information management software (LIMS), automated screen builders, nanoliter-scale drop setters, and automated imagers [16]. These systems significantly reduce human error in liquid handling and allow researchers to set up thousands of crystallization trials with minimal protein consumption.

Advanced imaging modalities enhance the ability to detect and characterize crystal formation:

- Visible Light Imaging: Suitable for analyzing large crystals but cannot distinguish between protein and salt crystals.

- Ultraviolet (UV) Imaging: Utilizes natural protein fluorescence to distinguish protein crystals from salt.

- Multi-fluorescent Imaging (MFI): Employs trace fluorescent labeling to efficiently identify protein crystals in complex mixtures.

- SONICC: Combines second harmonic generation with UV two-photon excited fluorescence to detect microcrystals, even those obscured in lipid cubic phase or aggregates [16].

Artificial intelligence-based autoscoring models are increasingly being integrated with crystallization software to help researchers analyze the extensive image datasets generated by high-throughput experiments [16].

Innovative Approaches: Microgravity and Bioassemblers

Microgravity environments in space offer unique advantages for protein crystallization by minimizing buoyancy-driven convection, sedimentation, and hydrostatic pressure [17]. These quiescent conditions promote more orderly crystal packing and can produce crystals with improved order, fewer defects, and better diffraction properties compared to Earth-grown crystals.

Recent innovations include the development of bioassembler systems specifically engineered for protein crystallization in space. One such system, the "Organ.Aut," employs magnetic forces to assemble biomaterials in a controlled manner and has successfully produced highly ordered lysozyme crystals diffracting to approximately 1 Å resolution in space [17]. These systems allow for direct mixing of protein and precipitant solutions on space stations and real-time observation of crystal growth, addressing previous challenges in sample handling and inspection during space-based crystallization experiments.

Navigating the protein phase diagram from supersaturation to crystal growth represents the core principle underlying rational approaches to protein crystallization. For beginning researchers, understanding that crystallization is not a single event but a pathway through different thermodynamic zones is fundamental to designing successful experiments. The metastable zone, in particular, offers the most promising conditions for growing high-quality, well-ordered crystals, especially when accessed through techniques like microseeding [20].

The future of protein crystallization lies in increasingly rational approaches that leverage detailed phase behavior knowledge, high-throughput automation, and innovative technologies like microgravity crystallization [17] [19]. By continuing to shift from empirical screening to principle-based design, researchers can overcome the challenges of crystallizing complex targets, ultimately accelerating structural biology and drug discovery efforts. For those beginning research in this field, mastering the phase diagram provides not only practical experimental guidance but also a deeper theoretical framework for understanding and innovating in protein crystallization science.

In the realm of structural biology, protein crystallization represents the critical gateway to elucidating three-dimensional molecular structures through X-ray crystallography. This process, essential for understanding protein function, facilitating drug design, and unraveling disease mechanisms, is absolutely dependent on the quality of the initial protein sample [23]. The journey from a protein solution to a highly ordered crystal lattice is remarkably demanding, requiring the protein molecules to self-organize into a translationally periodic arrangement with long-range order [24]. To achieve this molecular self-assembly, the protein sample must meet stringent prerequisite conditions. Sample purity, stability, and homogeneity are not merely advantageous—they are fundamental, non-negotiable requirements without which crystallization efforts are fundamentally compromised [25] [24] [3]. This technical guide examines the indispensable role of these three pillars in the protein crystallization workflow, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge and practical methodologies needed to prepare samples capable of forming diffraction-quality crystals.

The Critical Triad: Purity, Stability, and Homogeneity

Pillar 1: Protein Purity

Protein purity is arguably the most critical factor for successful crystallization. The presence of impurities, even in small amounts, can severely disrupt the highly ordered process of crystal lattice formation. Impurities may include other proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, or carbohydrates that co-purify with the target protein [3]. These contaminants compete with the target protein for interactions, leading to non-specific aggregation, amorphous precipitation, or disordered crystals that lack the periodic regularity required for diffraction [3]. Crystallization typically requires a purity level of at least 95% as assessed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie-blue staining [25]. However, for particularly challenging proteins, even higher purity levels may be necessary. Furthermore, post-translational modifications such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, or proteolytic cleavage must be homogeneous throughout the sample, as heterogeneity in these modifications creates chemical variability that prevents uniform molecular packing [25] [24].

Table 1: Analytical Methods for Assessing Protein Purity

| Method | Key Application in Purity Assessment | Optimal Outcome for Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE | Assesses protein size homogeneity and detects contaminating proteins [25] | Single band at expected molecular weight [25] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Detects chemical heterogeneity, post-translational modifications, and proteolysis [24] | Single major species with expected mass [24] |

| Chromatography (SEC, IEX) | Evaluates sample composition and separates protein variants [23] | Single, symmetric elution peak [23] |

Pillar 2: Protein Stability

Protein stability encompasses both conformational stability (the maintenance of native structure) and compositional stability (the maintenance of chemical identity over time) [24]. A protein must remain stable throughout the crystallization process, which can take days to months [3]. Conformational instability, manifested as flexible regions, disordered domains, or dynamic variability, prevents proteins from adopting consistent orientations needed for lattice formation [24]. Intrinsically disordered proteins or regions are particularly challenging for this reason [24]. Compositional instability, such as degradation through proteolysis, oxidation of cysteine residues, or deamidation of asparagine and glutamine, introduces chemical heterogeneity that disrupts crystal packing [24] [3]. Stability must be maintained not only in the storage buffer but also under the conditions of the crystallization experiment itself.

Table 2: Reducing Agents for Maintaining Protein Stability

| Reducing Agent | Solution Half-Life | Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | 40 h (pH 6.5), 1.5 h (pH 8.5) [3] | Short-term experiments at lower pH [3] |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | >500 h (pH 1.5–11.1) in non-phosphate buffers [3] | Long-term experiments, wide pH range [3] |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | 100 h (pH 6.5), 4.0 h (pH 8.5) [3] | Less efficient than DTT or TCEP [3] |

Pillar 3: Protein Homogeneity

Homogeneity refers to the uniformity of the protein sample in terms of conformational state, oligomeric state, and monodispersity. Even a pure and stable protein may fail to crystallize if it exists in multiple conformational or oligomeric states [25] [3]. The goal is a monodisperse solution where all protein molecules have identical shape, size, and interaction surfaces. This uniformity allows them to pack into a repeating lattice. Gel filtration is commonly used to ensure a homogenous sample following purification, while dynamic light scattering (DLS) is invaluable for confirming a single, homogenous protein population in solution [25]. Samples prone to aggregation, as indicated by multiple peaks in size-exclusion chromatography or polydisperse populations in DLS, are notoriously difficult to crystallize [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatography Resins | Protein purification to achieve >95% purity [25] [23] | Affinity, Ion-Exchange, Size-Exclusion resins [23] |

| Precipitating Agents | Reduce protein solubility to drive crystallization [3] | Ammonium sulfate, Polyethylene glycols (PEGs) [3] |

| Buffers and Salts | Maintain protein stability and pH [3] | HEPES, Tris; Sodium Chloride (keep <200 mM) [3] |

| Stabilizing Additives | Enhance solubility and maintain native conformation [26] | Glycerol (<5% v/v), ligands, substrates, metal ions [3] [26] |

| Reducing Agents | Prevent cysteine oxidation and maintain activity [3] | DTT, TCEP, BME (choice depends on pH and timescale) [3] |

Experimental Workflows for Quality Assessment

Workflow for Evaluating Sample Quality

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for preparing and evaluating a protein sample to ensure it meets the essential prerequisites for crystallization trials.

Comprehensive Stability Assessment Protocol

Evaluating protein stability requires a multi-faceted approach. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive protocol for assessing both conformational and compositional stability, which is critical for successful crystallization.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) for Homogeneity

Principle: SEC separates proteins based on their hydrodynamic volume, providing information about oligomeric state and aggregation [23]. A monodisperse sample appears as a single, symmetric peak at the elution volume corresponding to the correct oligomeric state.

Protocol:

- Column Equilibration: Equilibrate the SEC column with at least two column volumes of your storage buffer (e.g., 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5).

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge the protein sample (≥95% pure) at high speed (e.g., 14,000 × g) for 10 minutes to remove any insoluble material.

- Sample Loading: Load a volume appropriate for your column size (typically 0.5-1% of the column volume) onto the pre-equilibrated column.

- Chromatography: Run the chromatography at a flow rate suitable for the column, monitoring the UV absorbance at 280 nm.

- Data Analysis: Collect fractions corresponding to the major peak. Analyze the peak symmetry and elution volume compared to standards. A single, symmetric peak indicates homogeneity suitable for crystallization [25].

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for Monodispersity

Principle: DLS measures fluctuations in scattered light caused by Brownian motion of particles in solution, providing a hydrodynamic size distribution [25] [3]. It is a rapid method to assess sample monodispersity and detect aggregation.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Clarify the protein sample by centrifugation (≥95% pure). For crystallization purposes, use the same concentrated stock intended for crystallization trials.

- Instrument Setup: Load 15-20 μL of sample into a quartz cuvette or plate. Set the instrument to the appropriate temperature (typically 4°C or 20°C).

- Data Collection: Perform multiple measurements (typically 10-15) per sample to ensure reproducibility.

- Data Interpretation: Examine the size distribution plot. An ideal sample for crystallization shows a single, sharp peak with a polydispersity value below 20-30%. The presence of multiple peaks indicates heterogeneity, which must be addressed before crystallization trials [3].

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) for Stability

Principle: Also known as a thermal shift assay, DSF monitors the unfolding of a protein as temperature increases using a fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic patches exposed during denaturation [3]. The midpoint of the unfolding transition (melting temperature, Tₘ) indicates conformational stability.

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a protein solution at 0.5-2 mg/mL in the desired buffer. Include a 1:1000 dilution of a fluorescent dye such as SYPRO Orange.

- Plate Setup: Dispense 20-25 μL of the protein-dye mixture into each well of a real-time PCR plate. For buffer screening, include different buffer conditions in adjacent wells.

- Run Experiment: Place the plate in a real-time PCR instrument and ramp the temperature from 25°C to 95°C at a rate of 1°C per minute while monitoring fluorescence.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence versus temperature and calculate the Tₘ for each condition. The buffer condition yielding the highest Tₘ provides the greatest conformational stability and is optimal for crystallization trials [3].

The path to successful protein crystallization is fundamentally predicated on meticulous sample preparation. Purity exceeding 95%, conformational and compositional stability, and rigorous homogeneity are not merely beneficial attributes but absolute prerequisites that directly determine the feasibility of forming a well-ordered crystal lattice [25] [24]. Neglecting any one of these pillars undermines the entire structural biology enterprise. By implementing the systematic assessment workflows and detailed experimental protocols outlined in this guide—including SEC, DLS, and DSF—researchers can objectively quantify these essential parameters. This disciplined, analytical approach to sample preparation transforms protein crystallization from a black art into a rational scientific process, ultimately accelerating the generation of high-quality structural data to drive scientific discovery and drug development.

Protein crystallization is a critical step for structural biology, enabling the determination of three-dimensional protein structures through techniques like X-ray crystallography. This process is highly sensitive to the biochemical environment, where factors such as buffer composition, salt concentration, pH, and redox potential must be meticulously controlled. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these key factors, offering established methodologies and practical insights to assist researchers in designing robust crystallization experiments. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on protein crystallization for beginner researchers, this whitepaper synthesizes foundational principles with advanced optimization strategies to enhance crystallization success rates for scientists and drug development professionals.

The elucidation of protein structure via X-ray crystallography begins with the growth of high-quality, well-ordered crystals. This process is thermodynamically driven and occurs in distinct phases of nucleation and growth, both of which are profoundly influenced by the solution conditions [27] [28]. A fundamental understanding and careful manipulation of the biochemical environment—specifically the buffers, salts, pH, and reducing agents—is therefore not merely beneficial but essential for successful crystallization outcomes.

The challenge lies in the unique nature of each protein; conditions that promote crystallization for one may lead to precipitation or amorphous aggregation for another. Buffer components maintain pH stability, salts modulate electrostatic interactions, pH determines net charge and solubility, and reducing agents control disulfide bond integrity. This guide deconstructs these critical variables, providing a systematic framework for beginners to navigate the complex landscape of protein crystallization. The subsequent sections will delve into each factor's specific roles, present optimized experimental protocols, and provide practical tools to integrate this knowledge into effective crystallization strategies.

The Fundamental Role of Buffers

Buffer Composition and Selection

Buffers are crucial for maintaining a stable pH environment, which is a prerequisite for protein stability and consistent crystallization results. The choice of buffer system directly influences protein behavior by affecting its charge state, solubility, and conformational homogeneity. While standard chromatography buffers (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5 with 100 mM NaCl) are common starting points, they are often suboptimal for crystallization [29]. Research indicates that screening and selecting optimal buffer components can significantly enhance protein solubility, which in turn increases the number of successful crystallization conditions in initial screens [29] [30].

Advanced strategies involve the use of multi-buffer systems that allow sampling of a broad pH range without altering the chemical composition of the buffering component, thereby simplifying the optimization process by reducing variable interdependence [31]. The ionic effects of the buffer should also be considered; for instance, high salt concentrations (e.g., 1 M NaCl) in Tris-HCl or HEPES buffers have been shown to significantly stabilize proteins like Beta-lactoglobulin, correlating with improved crystallization success [30].

Buffer Optimization Methodology

Optimizing the buffer for a specific protein is a critical step preceding crystallization trials. The primary goal is to identify conditions that maximize protein solubility and stability, thereby promoting ordered crystal growth instead of precipitation.

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Protocol: DSF is a high-throughput method for rapidly assessing protein stability across a wide range of buffer conditions.

- Sample Preparation: Dispense a commercial 96-condition buffer screen (e.g., the RUBIC screen from Molecular Dimensions) into a 384-well PCR plate. Each condition is typically tested with multiple replicates.

- Protein Addition: Add the target protein to each well. A final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL is commonly used.

- Thermal Ramp: Load the plate into a DSF instrument (e.g., SUPR-DSF) and perform a thermal ramp, for example, from 10°C to 95°C at a rate of 1°C per minute. The instrument monitors changes in fluorescence related to protein unfolding.

- Data Analysis: Determine the melting temperature (Tm) for each condition using algorithms like the barycentric mean. Generate a heat map of Tm values to visually identify the most stabilizing conditions (highest Tm). These conditions are prime candidates for downstream crystallization screening [30].

Solubility Enhancement Protocol:

- Initial Assessment: Estimate relative solubility improvements by observing the protein's resistance to precipitation when challenged with a precipitant like Polyethylene Glycol 8000 [29].

- Additive Screening: For proteins with limited solubility improvement from buffer optimization alone, additives like glycerol can be introduced to further enhance solubility.

- Maximum Solubility Determination: Concentrate the optimized protein solution until a precipitate forms. The concentration of protein in the supernatant then provides an estimate of the upper solubility limit, which directly informs the ideal starting protein concentration for crystallization trials [29].

Critical Influence of Salts and Ionic Strength

Mechanisms of Salt Action

Salts exert a dual influence on proteins in solution, affecting both stability and solubility through two primary mechanisms: electrostatic shielding and altering water structure.

- Electrostatic Shielding: At low to moderate concentrations, salts shield charges on the protein surface, reducing electrostatic repulsions between protein molecules. This is governed by the Debye-Hückel theory and can promote the close approach necessary for crystal lattice formation [27].

- Hofmeister Series: At high concentrations, salts directly affect protein solubility based on their position in the Hofmeister series. Kosmotropic salts (e.g., sulfate, phosphate) stabilize the native protein structure and decrease solubility ("salting out"), making them effective crystallizing agents. In contrast, chaotropic salts (e.g., thiocyanate, perchlorate) destabilize the protein structure and can increase solubility ("salting in") [27].

The marginal ionic strength required for crystallization increases as the difference between the protein's pI and the buffer pH grows larger, consistent with the need for greater electrostatic screening under conditions of high net charge [27].

Optimizing Salt Concentration

The optimal salt concentration is a delicate balance. It must be high enough to provide necessary stabilization and screening but not so high as to cause non-specific precipitation or to destabilize the protein.

Table 1: Effects of Salt Concentration on Crystallization

| Salt Level | Impact on Protein | Impact on Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Too Low | Insufficient charge shielding; high solubility | Fails to reach marginal concentration for nucleation in the drop [27] |

| Optimal | Balances solubility and attractive interactions | Promotes slow dehydration and controlled crystal growth [27] |

| Too High | Can destabilize or "salt out" the protein | Leads to uncontrolled nucleation and precipitation [27] |

For large macromolecular complexes or viruses, high salt concentrations are often ineffective at inducing crystallization, and polymers like Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) are instead the preferred precipitant [27]. Furthermore, the type of salt can influence the crystal form and quality, necessitating empirical screening.

Controlling pH and the Isoelectric Point (pI)

The pH-pI Relationship

The pH of the solution relative to a protein's isoelectric point (pI) is a master variable controlling its net charge and electrostatic interactions. A protein carries a net positive charge at pH values below its pI and a net negative charge above its pI. At the pI, the net charge is zero, electrostatic repulsion is minimized, and the protein is most prone to aggregation and precipitation [27]. While this precipitation can be detrimental, a controlled approach towards the pI can facilitate the weak attractions needed for crystallization.

A general guideline observed in crystallization databases is that acidic proteins (pI < 7) tend to crystallize at approximately one pH unit above their pI, while basic proteins (pI > 7) often crystallize at about 1.5–3 pH units below their pI [27]. This strategy ensures the protein has a small, defined net charge that can facilitate ordered lattice formation without causing irreversible aggregation.

pH-Modulation Crystallization

For compounds with challenging solubility profiles, such as zwitterionic molecules that possess both an amino group and a carboxylic acid group, pH-modulation crystallization is a powerful technique. This method involves carefully adjusting the pH to traverse the solubility curve and enter the metastable zone where nucleation and growth can be controlled [32].

Protocol for pH-Modulation Crystallization:

- pKa Determination: Intensively investigate the pKa values of the ionizable groups to understand the compound's dissociation equilibrium and solubility profile [32].

- Metastable Zone Width: Identify the metastable zone width (MZW)—the region between the solubility curve and the spontaneous nucleation boundary—where crystal growth can occur without excessive nucleation [32].

- Controlled Nucleation: The key to success is controlling the number of primary particles that aggregate into secondary particles. A higher number of primary particles can lead to the formation of larger, monodisperse crystals with better filtration properties [32].

The Role of Reducing Agents

Disulfide Bond Management

Reducing agents are essential for cleaving and preventing the reformation of disulfide bonds, both within (intramolecular) and between (intermolecular) protein molecules. Uncontrolled disulfide bonding can lead to protein aggregation, heterogeneity, and precipitation, all of which inhibit the formation of high-quality crystals [27] [33]. These agents are particularly critical for proteins that contain cysteine residues, especially when those residues are surface-exposed.

The most common reducing agents are thiol-based, such as Dithiothreitol (DTT), Dithioerythritol (DTE), and β-Mercaptoethanol (BME). They work through a thiol-disulfide exchange mechanism to maintain cysteine residues in their reduced (-SH) state. A key advancement in this area is Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), which is a strong, odor-free, and thiol-free reducing agent that is more stable than DTT or BME and effective over a wider pH range [33].

Selection and Use of Reducing Agents

The choice of reducing agent depends on the specific needs of the protein and the crystallization experiment. Some agents can interact with metal ions present in the protein sample or buffer; for example, BME is sensitive to cobalt and copper, while DTT is sensitive to nickel [27].

Table 2: Common Reducing Agents for Crystallization

| Reagent | Key Features | Common Use in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| TCEP | Thiol-free; odor-free; more stable; wide pH range | Ideal for long-term stability; preferred for metalsensitive samples [33] |

| DTT/DTE | Strong reductant; common in storage buffers | Used to prevent aggregation during purification; may need to be removed pre-crystallization [27] [33] |

| β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) | Volatile; less potent than DTT or TCEP | Less favored for crystallization due to volatility and odor [27] [33] |

It is often advisable to use reducing agents during protein purification and storage to maintain homogeneity. However, for the crystallization experiment itself, it may be beneficial to remove the reducing agent via dialysis or buffer exchange to avoid potential interference with crystal contacts. The use of immobilized TCEP columns can facilitate this removal [33].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Pre-Crystallization Optimization Workflow

A systematic approach to buffer optimization before setting up crystallization screens can dramatically improve success rates. The following workflow integrates key concepts from previous sections into a logical sequence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

A well-stocked laboratory is crucial for efficiently navigating the optimization process. The table below lists key reagents and their specific functions in preparing a protein for crystallization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pre-Crystallization Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Systems | HEPES, Tris, Citric Acid, SPG buffer [30] [31] | Maintain pH stability; screen for optimal protein stability. |

| Salts | Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Ammonium Sulfate, Sodium Citrate [27] [30] | Modulate ionic strength and protein solubility via electrostatic shielding or "salting out". |

| Reducing Agents | TCEP, DTT, β-Mercaptoethanol [27] [33] | Maintain disulfide bonds in reduced state to prevent aggregation and ensure sample homogeneity. |

| Solubility Additives | Glycerol, L-Arginine, L-Glutamate [27] | Increase protein solubility and prevent aggregation without disrupting specific interactions. |

| Precipitants | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Methylpentanediol (MPD) [29] [27] | Excluded from protein surface, they increase effective protein concentration and induce supersaturation. |

| Denaturants | Guanidine-HCl, Urea [33] | Solubilize hydrophobic proteins under denaturing conditions for refolding studies. |

The path to successful protein crystallization is paved with meticulous attention to the biochemical environment. As detailed in this guide, the interplay between buffers, salts, pH, and reducing agents is not a matter of chance but one of controlled, rational design. Beginners must internalize that optimizing these factors before embarking on extensive crystallization screens is not an optional prelude but a fundamental requirement. By leveraging high-throughput stability assays like DSF, understanding the relationship between pH and pI, carefully selecting salts and ionic strength, and judiciously employing reducing agents, researchers can transform a problematic protein sample into a candidate ripe for crystallization. The integrated workflows and toolkit provided here offer a strategic starting point. Ultimately, mastering these key biochemical factors empowers researchers to systematically navigate the challenges of protein crystallization, thereby accelerating progress in structural biology and rational drug design.

From Theory to Bench: A Practical Guide to Crystallization Techniques and Setup

Protein crystallization is a critical step in structural biology, enabling researchers to determine the three-dimensional structures of proteins via techniques like X-ray crystallography. This process, which involves bringing a purified protein to a supersaturated state to form ordered crystals, remains a significant bottleneck in structural determination [10] [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate crystallization technique is paramount to success. The chosen method influences the consumption of often-precious protein, the time required to obtain results, and the ultimate quality and size of the crystals. This guide provides an in-depth comparison of the three most common laboratory methods: vapor diffusion, microbatch, and dialysis. By understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each technique, scientists can make informed decisions to optimize their crystallization trials.

Core Principles of Protein Crystallization

Protein crystallization requires the careful creation of a supersaturated solution where protein molecules are driven to form an ordered, repeating lattice. The fundamental principle involves gradually altering the protein's solvent environment to reduce its solubility. This is typically achieved by adding mild precipitating agents (such as salts or polymers), adjusting the pH, changing the temperature, or a combination of these factors [2]. The goal is to slowly cross the boundary into the metastable zone of the phase diagram, where crystal nucleation and growth can occur without spontaneous precipitation [10]. The resulting protein crystals are notably different from their small-molecule counterparts; they contain a large amount of solvent (often 25-90%) within their lattice, making them soft, sensitive to handling, and susceptible to dehydration [2].

Method 1: Vapor Diffusion

Vapor diffusion is the most widely employed method for initial protein crystallization screening [10]. Its popularity stems from its simplicity and effectiveness in exploring a wide range of conditions.

How It Works

In vapor diffusion, a small drop containing a mixture of the protein sample and precipitant solution is suspended (hanging drop) or placed on a platform (sitting drop) above a much larger reservoir of precipitant solution within a sealed chamber [10]. The reservoir solution has a higher concentration of precipitant than the drop. This creates a vapor pressure differential, causing water to slowly evaporate from the drop and diffuse into the reservoir. Consequently, the drop dehydrates, gradually concentrating both the protein and the precipitant until equilibrium with the reservoir is reached [10]. This slow concentration change systematically moves the drop from an undersaturated state into a zone of supersaturation conducive to crystal nucleation and growth.

Experimental Protocol: Hanging Drop Vapor Diffusion

The following protocol, adapted from a standardized methodology, uses lysozyme as a model protein [10].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample (e.g., 50 mg/mL lysozyme)

- 24-well hanging drop tray

- Precipitant solutions (e.g., NaCl at varying molarities in NaOAc buffer at varying pH)

- Silicon grease

- Siliconized cover slides

- Low-retention pipette tips (0.1-2 µL)

- Tweezers

- Professional wipes

Procedure:

- Prepare Precipitant Solutions: Filter stock solutions using a 0.22 µm filter. Prepare a matrix of conditions varying precipitant concentration and pH [10].

- Prepare Protein Sample: Thaw the protein sample on ice. Centrifuge at 18,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove any aggregates. Keep on ice until use [10].

- Set Up Tray: Fill the reservoir wells with 500 µL of precipitant solution. Create a continuous, thin ring of silicone grease around the rim of each well [10].

- Prepare Drop: Clean a cover slide with compressed air or a professional wipe. Pipette 2 µL of the protein solution onto the center of the cover slide. Add 2 µL of the reservoir solution to the same drop, carefully avoiding bubble formation [10].

- Seal Chamber: Gently flip the cover slide and place it over the corresponding well, ensuring the drop is centered. Press down lightly to seal the well with grease, taking care to leave a small gap to prevent air pressure buildup [10].

- Incubate and Monitor: Place the tray gently in a stable-temperature incubator (commonly 20°C). Avoid vibrations and temperature fluctuations. Check for crystal formation after 24 hours and then periodically over days or weeks [10].

Figure 1: Vapor diffusion workflow.

Method 2: Microbatch Crystallization

The microbatch method is characterized by its simplicity and low consumption of protein, making it excellent for high-throughput screening, particularly when protein quantity is limited [34] [35].

How It Works

In microbatch crystallization, the protein and precipitant solutions are directly mixed together in a single droplet, instantly bringing the protein to the desired supersaturated concentration [10]. This droplet is then dispensed under a layer of oil. The oil layer serves a dual purpose: it prevents evaporation of the drop (in standard microbatch) and protects the protein from airborne contaminants [10] [35]. A key variant, known as "modified microbatch" or "microbatch diffusion," uses a mixture of paraffin and silicone oils. Silicone oil is permeable to water, allowing for slow, controlled evaporation from the drop over time. This introduces a concentrating effect similar to vapor diffusion, enabling the method to scan through a broader range of conditions [34] [35].

Experimental Protocol: Microbatch Under Oil

This protocol outlines the procedure for setting up a standard microbatch experiment [10].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample

- 96-well microbatch tray or a shallow well plate

- Paraffin oil (or a 1:1 mixture of paraffin and silicone oil for modified microbatch)

- Low-retention pipette tips

Procedure:

- Prepare Plate: Air-spray the tray to remove dust. Fill the wells with paraffin oil (or the oil mixture) to a depth of about 3 mm, enough to cover subsequent drops [10].

- Dispense Protein: Pipette 1 µL of protein solution directly to the bottom of an oil-filled well [10].

- Dispense Precipitant: Add 1 µL of precipitant solution to the same well, ensuring it sinks and fuses with the protein droplet [10].

- Repeat and Incubate: Move to the next well and repeat the process until the tray is complete. Seal the plate if necessary and place it in a stable-temperature environment for incubation. Monitor as for vapor diffusion [10].

Method 3: Dialysis

Dialysis is a powerful technique for crystallizing proteins that are sensitive to gradual changes in ionic strength or pH, and it is particularly useful for growing large, high-quality crystals [36] [37].

How It Works

Dialysis employs a semi-permeable membrane that allows the passage of small molecules and water but retains the large protein molecules. The protein solution is placed on one side of the membrane, which is exposed to a large volume of precipitant solution. The precipitant and buffer components slowly diffuse across the membrane, gradually changing the environment of the protein in a very controlled and gentle manner [36]. This slow equilibration allows for precise control over the level of supersaturation. A "double-dialysis" technique, which incorporates a second membrane to further slow the rate of equilibration, has been shown to reduce the number of nucleation sites and can lead to a significant increase in crystal size [36].