Protein Side-Chain Rotamers: From Statistical Foundations to AI-Driven Prediction in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the statistical conformations of protein side-chain rotamers, a critical field for understanding protein structure and function.

Protein Side-Chain Rotamers: From Statistical Foundations to AI-Driven Prediction in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the statistical conformations of protein side-chain rotamers, a critical field for understanding protein structure and function. We begin by exploring the foundational principles of rotamer libraries, from early backbone-dependent statistical analyses to modern dynamics-informed ensembles. The review then details key methodological approaches for rotamer prediction and their diverse applications in protein design, structure prediction, and molecular docking. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses persistent challenges like conformational flexibility and the integration of continuous rotamers, while a final comparative analysis validates current methods against experimental data and benchmarks performance in the post-AlphaFold era. This synthesis is tailored for researchers, structural biologists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage rotamer analysis for biomedical innovation.

The Statistical Basis of Rotamers: From Crystal Structures to Conformational Dynamics

In structural biology and chemistry, rotamers, or rotational isomers, are conformations of a molecule arising from restricted rotation around single bonds. These discrete, energetically stable states are defined by specific torsional angles and are separated by energy barriers. In proteins, rotamers predominantly describe the side-chain conformations of amino acid residues, which are critical for understanding protein folding, function, and dynamics [1]. The study of rotamers provides the foundational framework for analyzing the statistical conformations of protein side-chains, a core aspect of structural bioinformatics and molecular modeling.

The principles of rotational isomeric state theory extend beyond proteins to synthetic polymers, describing how local conformational preferences influence the global statistical properties of polymer chains under theta conditions [2]. This guide details the core principles, quantitative data, and experimental protocols that define rotamers and their central role in statistical protein conformation research.

Core Principles and Definitions

Torsional Angles and Molecular Conformation

A torsion angle (or dihedral angle) describes the geometric relationship between two parts of a molecule connected by a chemical bond. It is defined by four consecutively bonded atoms (A-B-C-D) and represents the angle between the plane containing atoms A-B-C and the plane containing B-C-D [3]. In protein structures, two primary classes of torsion angles are defined:

- Backbone Torsional Angles: The protein backbone is described by three torsional angles: φ (phi, between C'-N-Cα-C'), ψ (psi, between N-Cα-C'-N), and ω (omega, between Cα-C'-N-Cα). The ω angle is typically restricted to 180° (trans) or 0° (cis) due to the partial double-bond character of the peptide bond [3].

- Side-Chain Torsional Angles: The rotations of amino acid side chains are described by a series of χ (chi) dihedral angles. χ1 involves the atoms N-Cα-Cβ-Cγ, χ2 involves Cα-Cβ-Cγ-Cδ, and so on, proceeding outward along the side chain [1] [3].

Rotamers as Rotational Isomers

Rotational isomers are stereoisomers produced by rotation around σ bonds. When this rotation is restricted due to energy barriers, different stable conformations—rotamers—can exist [4]. These conformers are often rapidly interconverting at room temperature [4].

For protein side chains with sp3-hybridized carbons (e.g., leucine, valine, isoleucine), the χ torsional angles tend to cluster around three favored, low-energy positions: approximately +60°, 180°, and -60° [1] [3]. These correspond to specific conformational nomenclatures:

Table 1: Nomenclature for Common Torsional Angles

| Angle (Approx.) | IUPAC Conformation | Common Name (Side-Chain) | Alternate Nomenclature |

|---|---|---|---|

| +60° | gauche+ (g+) |

gauche+ |

p |

| 180° | anti |

trans (t) |

t |

| -60° | gauche- (g-) |

gauche- |

m |

The p (+60°), t (180°), and m (-60°) nomenclature was proposed by Lovell et al. to ensure consistency [1]. A specific rotamer is denoted by the combination of its χ angles; for example, a methionine residue with χ1=p, χ2=t, and χ3=p is described as having a "ptp" rotamer [1].

Rotamer Libraries and Their Applications

A rotamer library is a collection of rotamers classified according to their frequency of occurrence in nature. These libraries are constructed through statistical analysis of side-chain conformations from experimentally determined protein structures or from molecular dynamics simulations [1]. They are indispensable tools for protein structure prediction, homology modeling, and structure validation.

Several types of rotamer libraries exist, each with specific advantages:

- Backbone-Independent Libraries: Classify rotamers based solely on side-chain torsional angles, without considering the backbone conformation. The "penultimate rotamer library" is an example, known for its high quality, good coverage, and a manageable number of rotamer classes (around 153), making it ideal for analysis and visualization [1].

- Backbone-Dependent Libraries: The rotamer preferences are conditional on the backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ). The Dunbrack library is a widely used backbone-dependent library, as side-chain conformational energies are influenced by the local backbone structure [1] [3].

- Dynamics-Derived Libraries: Libraries like the "dynameomics" rotamer library employ Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to predict rotamer populations in a solution environment, providing insights into rotamer flexibility that may not be fully captured by static crystal structures [1].

Quantitative Analysis of Side-Chain Conformations

Quantitative studies of side-chain conformations reveal significant variability and flexibility in protein structures. A large-scale statistical analysis of protein structures has sought to quantify this side-chain polymorphism, which can be categorized into several types [5]:

Table 2: Types of Side-Chain Conformational Variations in Protein Structures

| Conformation Type | Description | Experimental Indication |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Conformation | Side-chains constrained in a defined region; coordinates are definite. | Buried residues with clear, single-state electron density. |

| Discrete Conformation | Different discrete conformations are possible and observable. | Alternate locations (A, B, etc.) in PDB files; different conformations across multiple structures of the same protein. |

| Cloud Conformation | Side-chain covers a limited continuous region. | Elongated or broad electron density that is modeled with fractional occupancies. |

| Flexible Conformation | Conformation is not clearly captured; side-chain is intrinsically flexible. | Weak or missing electron density for some or all side-chain atoms. |

Analysis of a non-redundant set of protein chains showed that approximately 72% of side-chains have completely reliable atom coordinates (electron density >1 sigma). This implies a significant proportion of side-chains exhibit some degree of conformational variability or uncertainty [5]. Furthermore, conformational flexibility is closely related to solvent exposure, degrees of freedom, and hydrophilicity, with solvent-exposed residues showing greater variability [5].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics for Rotamer Analysis (RD Analysis)

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a powerful computational method for studying rotamer behavior in a solution-like environment, highlighting favorable side-chain conformations and their dynamics over time [1].

Protocol for Rotamer Dynamics (RD) Analysis [1]:

- System Setup and MD Simulation: An MD simulation is performed using a program like AMBER, GROMACS, or CHARMM, with appropriate force fields and solvation.

- Trajectory Processing: The resulting trajectory file is converted to PDB format. Using a tool like the

cpptrajmodule in AMBER, each frame of the trajectory is saved as a separate PDB file. - Torsional Angle Extraction: For each individual frame (PDB file), torsional angles (φ, ψ, χ1, χ2, etc.) are calculated for every residue. This can be automated using structural analysis modules like

Bio3Din the R programming language. - Data Transformation: The extracted torsional angle data is reorganized into a table where rows represent simulation frames and columns represent the different angles for each residue.

- Rotamer Classification: The torsional angle data is classified into specific rotamers using a defined rotamer library (e.g., the penultimate rotamer library). This classification is typically implemented using

if/elsestatements or lookup tables in a scripting language like R, assigning a rotamer state (e.g.,t,p,m) to each residue in every frame based on its χ angles.

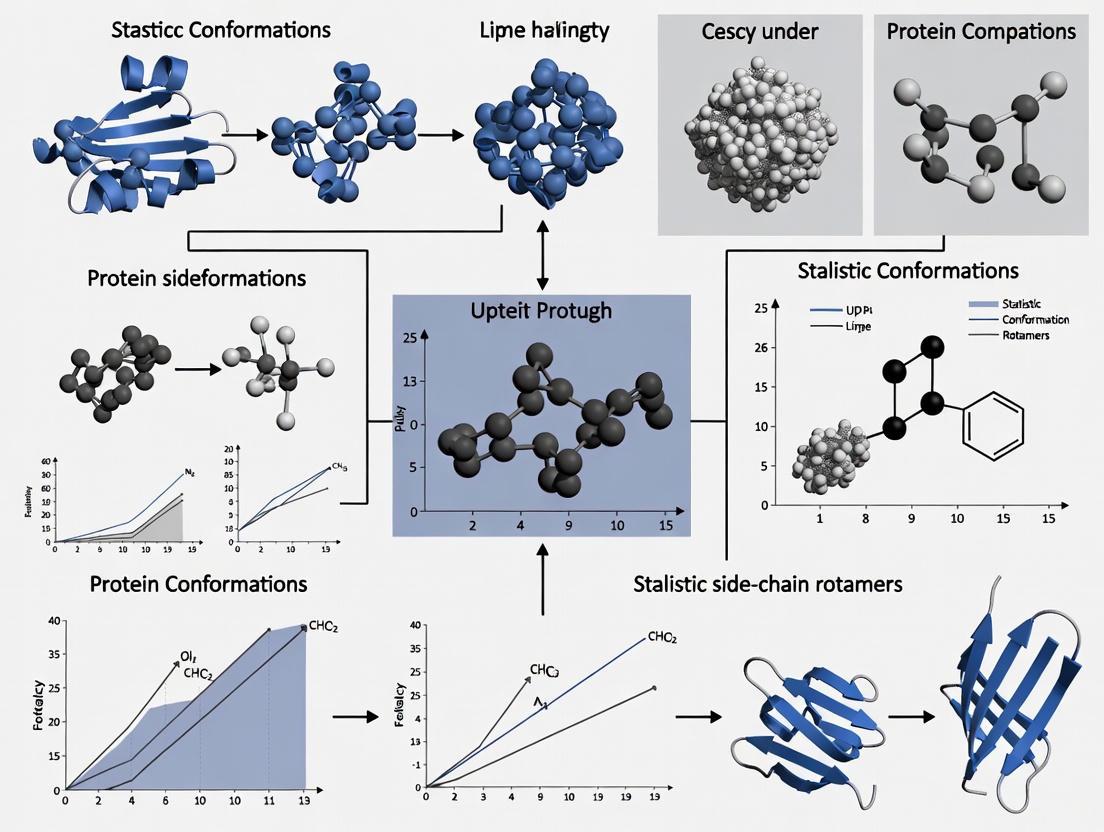

Workflow for Rotamer Dynamics Analysis

Machine Learning for Side-Chain Prediction

AlphaFold2 (AF2) has revolutionized protein structure prediction, but its ability to predict side-chain conformations with high accuracy is an area of active investigation. Studies evaluating ColabFold (an AF2 implementation) on benchmark proteins reveal specific performance characteristics [6] [7]:

- Accuracy by χ Angle: Prediction accuracy is highest for χ1 angles and decreases for outer angles. On average, the error for χ1 angles is ~14%, rising to ~48% for χ3 angles [6].

- Rotamer Bias: AlphaFold2 demonstrates a bias toward the most prevalent rotamer states found in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), which may limit its ability to accurately capture rare side-chain conformations [6].

- Impact of Templates: Using structural templates during prediction improves accuracy, particularly for χ1 angles, where the improvement can be ~31% on average [6].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Rotamer Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| AMBER | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs used to perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, generating trajectories of atomic motions. |

| GROMACS | A high-performance MD simulation software package used to simulate the Newtonian equations of motion for systems with hundreds to millions of particles. |

| CHARMM | A widely used program for energy minimization, MD simulations, and analysis of biological macromolecules, with extensive force fields. |

| cpptraj | A tool within the AMBER package for processing and analyzing MD trajectories, such as converting file formats and stripping solvent molecules. |

| Bio3D (R Package) | A tool for the analysis of protein structure and sequence, including the comparative analysis of protein structures and MD trajectories to extract torsional angles. |

| R / Python | Programming languages with extensive ecosystems for statistical analysis, data transformation, and custom classification of rotamers from raw data. |

| Penultimate Rotamer Library | A backbone-independent rotamer library providing idealized torsional angle ranges and nomenclature for classifying side-chain conformations. |

| Dunbrack Rotamer Library | A backbone-dependent rotamer library that provides rotamer probabilities and dihedral angle distributions conditional on the backbone φ and ψ angles. |

| AlphaFold2 / ColabFold | Machine learning-based tools for predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences, including side-chain atom coordinates. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | The single worldwide repository for the processing and distribution of 3D structural data of large biological molecules, used for library construction and validation. |

Rotamers, defined by specific torsional angles and governed by the principles of rotational isomers, are fundamental to a quantitative understanding of protein structure and dynamics. The field is supported by a robust framework of rotamer libraries, sophisticated computational methods like MD and machine learning, and a growing appreciation for the inherent conformational variability of protein side-chains. As quantitative analyses continue to reveal the complexity of side-chain conformational landscapes, future advancements in rotamer research will rely on integrating dynamic data, improving predictive algorithms for rare conformations, and developing more nuanced assessment methods for side-chain packing in protein modeling. This will be crucial for applications in protein design, drug development, and understanding the molecular basis of disease.

The statistical conformations of protein side chains, known as rotamers, are fundamental to protein structure, function, and design. Rotamer libraries systematically catalog these preferred side-chain conformations, defined by dihedral (χ) angles, which cluster in low-energy staggered positions near +60° (g+ or p), 180° (t), and -60° (g- or m) for tetrahedral geometry [8]. The evolution of these libraries from simple, backbone-independent lists to sophisticated, backbone-dependent probabilistic distributions represents a critical advancement in structural biology. This progression has fundamentally enhanced the accuracy of protein structure prediction, homology modeling, and computational protein design. This whitepaper traces the historical development of rotamer libraries through three pivotal stages: the foundational Ponder-Richards library, the transformative Dunbrack backbone-dependent libraries, and the rigorously validated Penultimate library, framing their development within the broader thesis of statistical conformational analysis.

The Foundational Work: Ponder-Richards Library

The concept of rotamer libraries was introduced in 1987 by Jane S. Ponder and Frederic M. Richards [8] [9]. Their work, "Tertiary templates for proteins: use of packing criteria in the enumeration of allowed sequences for different structural classes," established the first systematic compilation of protein side-chain conformations.

- Theoretical Basis: The library was predicated on the observation that side-chain conformations are not continuous but occupy discrete, low-energy minima. This allowed for the enumeration of a finite set of "rotamers" for each amino acid type, drastically simplifying the conformational space to be searched in modeling endeavors [8].

- Library Composition: The initial library comprised 67 rotamers, providing a single, backbone-independent set of preferred conformations for the 18 amino acids with rotatable χ1 bonds (excluding Gly and Ala) [10].

- Impact and Limitations: The Ponder-Richards library demonstrated that protein side-chain packing could be effectively modeled using a limited set of discrete conformations. It provided a critical proof-of-concept that enabled the development of early protein design and structure prediction algorithms. However, its primary limitation was its backbone-independent nature, treating rotamer preferences as invariant to the local backbone dihedral angles φ and ψ.

The Backbone-Dependent Revolution: Dunbrack Libraries

A major conceptual and practical leap forward was achieved by Roland L. Dunbrack, Jr. and colleagues with the introduction of backbone-dependent rotamer libraries. Initiated in 1993 and significantly refined through Bayesian statistical analysis in 1997, these libraries explicitly modeled rotamer probabilities and mean dihedral angles as a function of the backbone φ and ψ angles [11] [12].

- Theoretical Basis: The backbone-dependence of side-chain conformations is primarily due to steric repulsions between backbone atoms and the side-chain γ heavy atoms (e.g., CG, OG, SG). Dunbrack and Karplus (1994) provided a conformational analysis explaining these preferences through 'butane' and 'syn-pentane' effects, which create steric barriers at specific (φ, ψ) and χ1 combinations [13]. For instance, a valine side chain in the g+ conformation experiences steric clash with the backbone nitrogen of residue i+1 when ψ is near -60° [11].

- Methodological Evolution:

- The 1993 library was derived from 132 high-resolution protein structures and provided rotamer frequencies for each 20°x20° bin of the Ramachandran map [11].

- The 1997 library introduced a Bayesian statistical framework to robustly handle varying amounts of data across the Ramachandran map, using prior distributions derived from pooled data [12].

- The 2010 Smooth Library represented a further refinement, using adaptive kernel density estimates and kernel regressions to generate continuous, smooth probability functions and mean angles as a function of φ and ψ. This was crucial for algorithms that optimize backbone conformation using derivatives [14].

- Impact: Backbone-dependent libraries dramatically improved the accuracy of side-chain prediction in homology modeling [11] and became a cornerstone of powerful protein design and structure prediction software suites, including Rosetta, MODELLER, and PHENIX [11].

The Penultimate Library and Data Quality Focus

As the Protein Data Bank (PDB) grew, it became possible to create rotamer libraries with more stringent quality filters, leading to the development of the "Penultimate Rotamer Library" and its subsequent evolution into the "Ultimate" library used in modern validation tools like MolProbity [8].

- Theoretical Basis: The penultimate library was founded on the principle that previously published libraries contained rotamers with impossible internal atomic clashes when built with ideal geometry and hydrogen atoms. This indicated contamination from poorly modeled regions in the underlying structural data [15] [16].

- Methodology and Filters: To create a cleaner and more reliable library, the developers implemented stringent filtering criteria [15] [8] [16]:

- Data Quality: Removal of residues with high B-factors (≥40) or significant van der Waals overlaps (≥0.4 Å) to eliminate conformations with questionable justification.

- Statistical Robustness: Use of modal values rather than mean angles for rotamer definitions to avoid sensitivity to skew and bin boundaries, more accurately representing local energy minima.

- Enhanced Filtering (Ultimate Library): The subsequent "Ultimate" library, based on the Top8000 dataset, added residue-level electron-density filters (real-space correlation coefficient - RSCC, and local map value) alongside B-factor checks, effectively removing residues with poor electron density [8].

- Outcome: The penultimate library covered 94.5% of examples in high-quality protein data with only 153 rotamers, showing significantly fewer internal clashes and more reliable clustering of rotamer populations [16]. The modern MolProbity distributions use a three-tiered classification (favored, allowed, outlier) for validation, with only 0.3% of high-quality reference data falling into the outlier category [8].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Rotamer Libraries

| Library Name | Year | Key Innovation | Data Source & Filters | Number of Rotamers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ponder-Richards [10] [8] | 1987 | First backbone-independent rotamer library | Not specified | 67 |

| Dunbrack Backbone-Dependent [11] | 1993 | Rotamer preferences conditional on φ and ψ angles | 132 proteins, ≤ 2.0 Å resolution | Not specified |

| Dunbrack Bayesian [12] | 1997 | Bayesian statistics for data analysis | Expanded PDB | Not specified |

| Penultimate [15] [16] | 2000 | Stringent quality filtering (B-factor, steric clashes) | High-quality PDB subsets; B-factor < 40 | 153 |

| MolProbity "Ultimate" [8] | 2016 | Electron-density based residue filtering (RSCC) | Top8000 dataset (7,216 chains) | N/A (Probability Distributions) |

| NCN Algorithm Library [10] | 2004 | Extremely large, fine-step library for prediction | PDB, fine dihedral sampling (5° steps) | ~49,042 |

Experimental Protocols in Rotamer Analysis

The advancement of rotamer libraries has relied on specific experimental and computational protocols for data extraction, analysis, and application.

Protocol for Deriving a Statistical Rotamer Library

This protocol outlines the general process for creating libraries like the Penultimate and Dunbrack libraries.

- Dataset Curation: Collect a non-redundant set of high-resolution protein structures from the PDB (e.g., ≤ 1.8 Å resolution).

- Structure Preprocessing: Add hydrogen atoms to the models using programs like

Reduce, which also corrects amide flips for Asn, Gln, and His residues [8]. - Residue-Level Filtering: Apply stringent quality filters to exclude uncertain residues. Modern protocols use a combination of:

- Dihedral Angle Calculation: Extract φ, ψ, and χ angles for all qualifying residues.

- Statistical Analysis and Clustering:

- For backbone-independent libraries, calculate rotamer frequencies and modal angles across all data.

- For backbone-dependent libraries, bin data by φ and ψ (e.g., 10°x10° bins) and perform statistics within each bin, or use kernel density estimation for smooth libraries [14].

- Use modal values instead of means to define rotamer centers to avoid skew [15].

- Library Validation: Validate the new library by checking for internal atomic clashes in ideal geometry and assessing its coverage of a high-quality reference dataset [16].

Protocol for Side-Chain Prediction Using a Rotamer Library

This protocol is used in homology modeling and protein design to pack side chains onto a fixed backbone.

- Input Backbone: The algorithm starts with a protein backbone structure, either experimentally determined or predicted.

- Rotamer Assignment: For each residue position, a set of possible rotamers is drawn from the library. In backbone-dependent methods, the set is specific to the residue's φ and ψ angles.

- Conformational Search and Scoring: An algorithm (e.g., Dead-End Elimination, Monte Carlo simulated annealing) searches the combinatorial space of possible rotamer assignments across all residues [10]. Each candidate structure is scored by an energy function that may include:

- Van der Waals interactions: To model steric repulsion and attraction.

- Electrostatics and Hydrogen Bonding: To model polar interactions.

- Rotamer Probability: An energy term based on the negative log probability of the rotamer given the backbone (i.e., E = -ln(p(rotamer\|φ,ψ))) [11].

- Structure Selection: The combination of rotamers that minimizes the total energy (or maximizes the probability) is selected as the final predicted structure.

Diagram 1: Workflow for computational side-chain prediction using a rotamer library.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Rotamer and Protein Structure Research

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Rotamer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [8] | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | The fundamental source of raw structural data for deriving and validating rotamer libraries. |

| Dunbrack Rotamer Library [14] | Software/Library | Provides backbone-dependent rotamer frequencies, mean angles, and variances. | The standard reference for rotamer preferences in protein structure prediction, design, and validation. |

| MolProbity [8] | Software Service | All-atom structure validation tool for quantifying and diagnosing model quality. | Employs the "Ultimate" rotamer distributions to identify unlikely side-chain conformations in user-submitted models. |

| PHENIX [8] | Software Suite | Platform for automated crystallographic structure determination and refinement. | Utilizes modern rotamer libraries for model-building (rotamer choice) and validation during refinement. |

| Rosetta [11] | Software Suite | Comprehensive platform for de novo protein structure prediction and design. | Uses the Dunbrack library as a scoring function and for conformational sampling in protein design and folding simulations. |

| Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) [8] | Metric | Measures the fit between an atomic model and the experimental electron density. | A critical filter in creating modern libraries and validating individual side-chain conformations. |

The historical evolution of rotamer libraries from the foundational Ponder-Richards library, through the backbone-dependent revolution of Dunbrack, to the quality-driven penultimate and ultimate libraries, reflects the broader trajectory of structural biology into a data-rich, statistically rigorous discipline. Each stage has addressed limitations of its predecessor: first by enumerating conformations, then by contextualizing them with the backbone, and finally by rigorously vetting the underlying data. These advancements have been instrumental in making computational protein structure prediction, validation, and design reliable tools for research and drug development. The continued integration of side-chain and backbone conformational validation, supported by ever-larger and higher-quality structural datasets, promises further refinement of our understanding of protein structural statistics.

Protein side-chain rotamer libraries are collections of discrete conformations of amino acid side chains, representing local energy minima that arise from rotations around single bonds [17] [18]. These libraries are fundamental tools in structural biology, enabling efficient sampling of conformational space for applications ranging from protein structure prediction to protein design. The development of backbone-dependent rotamer libraries represents a significant advancement over earlier backbone-independent approaches, as they account for the critical influence of local backbone conformation (φ and ψ dihedral angles) on side-chain conformational preferences [11]. This backbone dependence is primarily driven by steric repulsions between backbone atoms and side-chain atoms, which create predictable patterns of allowed and disallowed rotamers across the Ramachandran map [11].

The application of Bayesian statistical analysis to rotamer library development, pioneered by Dunbrack and Cohen in 1997, provided a rigorous mathematical framework for handling varying amounts of structural data across different regions of the Ramachandran map [12] [19]. This approach combines prior knowledge about rotamer distributions with observed data from protein structures to form posterior distributions that represent a compromise between the two information sources [12]. The Bayesian methodology is particularly valuable for addressing sparse data problems in underpopulated regions of the Ramachandran map, allowing for more accurate probability estimates even when experimental observations are limited [20]. By incorporating the probabilistic nature of side-chain conformations, Bayesian-derived rotamer libraries have become indispensable tools for homology modeling, protein folding simulations, and the refinement of X-ray and NMR structures [12] [19].

Core Bayesian Statistical Framework

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Bayesian approach to rotamer library construction treats the estimation of rotamer probabilities as a problem of statistical inference where prior knowledge is systematically combined with experimental data. The foundation of this framework is Bayes' theorem, which in this context can be expressed as:

P(rotamer | backbone, data) ∝ P(data | rotamer, backbone) × P(rotamer | backbone)

where P(rotamer | backbone, data) represents the posterior probability distribution of a rotamer given the backbone conformation and observed data, P(data | rotamer, backbone) is the likelihood function representing how probable the observed data is under different rotamer assumptions, and P(rotamer | backbone) is the prior distribution encoding initial beliefs about rotamer probabilities before observing the data [12] [19].

For practical implementation, Dunbrack and Cohen developed a formulation where the prior distribution for χ₁ rotamers was derived as the product of φ-dependent and ψ-dependent probabilities, effectively assuming that the steric and electrostatic effects of the φ and ψ dihedral angles are independent [12] [11]. For subsequent chi angles (χ₂, χ₃, and χ₄), the prior distributions assumed Markovian dependence, where the probability of each rotamer type depends only on the previous chi rotamer in the chain [12]. This formulation allowed for efficient computation while capturing the essential dependencies between backbone conformation and side-chain rotamer preferences.

Advanced Methodological Developments

Table 1: Evolution of Bayesian Methodologies in Rotamer Library Development

| Methodological Approach | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete Bayesian Analysis (Dunbrack & Cohen, 1997) | Prior distributions from product of φ-dependent and ψ-dependent probabilities; 10°×10° grid of φ,ψ values [12] [19] | Rigorous handling of varying data amounts; improved probability estimates in sparse regions | Jagged probability surfaces; discontinuous derivatives |

| Kernel Density Estimation (Shapovalov & Dunbrack, 2011) | Adaptive kernel density estimates with von Mises distributions; continuous function of φ,ψ [17] | Smooth probability functions; enables gradient-based optimization; better treatment of non-rotameric degrees of freedom | Computational intensity; complex implementation |

| Dynamic Bayesian Networks (BASILISK, 2010) | Generative probabilistic model in continuous space; variable number of slices for different amino acids [18] | Avoids discretization artifacts; models all amino acids in unified framework; enables rigorous sampling with physical force fields | Complex model structure; requires significant training data |

| Markov Random Field Models (Zeng et al., 2011) | Integrates NMR data with empirical energies; Hausdorff-based measure for NOESY data likelihood [21] | Enables structure determination from unassigned NMR data; provable global optimum solutions | Specialized for NMR applications; complex likelihood calculations |

The original Bayesian framework has been substantially refined through several methodological advances. The 2011 smoothed backbone-dependent rotamer library introduced adaptive kernel density estimation with von Mises distribution kernels to address the "bumpiness" of probability surfaces in earlier libraries [17]. This approach replaced the discrete binning of φ and ψ angles with continuous probability density functions, enabling evaluation of rotamer probabilities as smooth functions of backbone dihedral angles [17]. The von Mises distribution, being the circular analogue of the Gaussian distribution, is particularly appropriate for modeling angular data while respecting their periodic nature [17] [18].

For non-rotameric degrees of freedom (such as the terminal χ angles of Asn, Asp, Gln, Glu, Phe, Trp, His, and Tyr), which connect sp³ to sp² hybridized groups and exhibit broad, asymmetric distributions, the kernel density approach models full probability density distributions rather than discrete rotamer bins [17]. This represents a significant improvement in capturing the continuous nature of these conformational degrees of freedom, which are poorly described by traditional rotamer models with simple mean angles and variances.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Preprocessing

The construction of Bayesian rotamer libraries begins with careful data curation from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The foundational 1997 library utilized 518 proteins with resolutions of 2.0 Å or better, applying strict quality filters to ensure structural reliability [12] [20]. For each residue in these structures, backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ) and side-chain dihedral angles (χ₁, χ₂, χ₃, χ₄) are calculated from atomic coordinates. Modern implementations, such as the 2011 smoothed library, incorporate additional filtering based on electron density calculations to remove highly dynamic side chains or protein segments with uncertain conformations [17]. This rigorous curation process ensures that the resulting statistical models are built on high-quality, reliable structural data.

The mathematical workflow for constructing a Bayesian rotamer library involves multiple stages of statistical estimation, each building upon the previous step to transform raw structural data into continuous probability distributions.

Kernel Density Estimation Protocol

The implementation of adaptive kernel density estimation for rotamer probabilities follows a specific computational protocol. For each residue type and rotamer, a probability density estimate ρ(φ,ψ|r) is constructed using von Mises kernels centered on each data point [17]. The von Mises distribution has the form ρ(x) = exp(κ cos x)/I₀(κ), where x is an angular variable, κ is the concentration parameter (inversely related to bandwidth), and I₀ is the modified Bessel function of the first kind of order zero [17]. The adaptive bandwidth varies with local data density, with wider kernels in sparse regions and narrower kernels in dense regions of the Ramachandran map [17]. This adaptability ensures optimal smoothing regardless of local sampling density.

For the rotamer probabilities themselves, Bayes' rule is applied to invert the conditional densities:

P(r|φ,ψ) = ρ(φ,ψ|r)P(r) / Σᵣ' ρ(φ,ψ|r')P(r')

where P(r) is the backbone-independent probability of rotamer r [17]. This formulation allows for continuous estimation of rotamer probabilities at any (φ,ψ) point, rather than being restricted to discrete bins.

For mean dihedral angles and variances, the 2011 library employs adaptive kernel regression estimators, making the concentration parameters κ adaptive to the local density of data around each query point [17]. The variance is modeled as heteroscedastic, meaning it depends on the backbone dihedral angles φ and ψ, providing more accurate uncertainty estimates across different regions of the Ramachandran map.

Steric and Energetic Basis of Backbone Dependence

The fundamental structural mechanism underlying backbone-dependent rotamer preferences involves steric repulsions between backbone atoms and side-chain γ heavy atoms (carbon, oxygen, or sulfur) [11]. These repulsions occur through specific five-atom connections that create predictable patterns of allowed and disallowed conformations. For example, the nitrogen atom of residue i+1 connects to the γ heavy atom of a side chain through the path N(i+1)-C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i)-Cγ(i), where the dihedral angle N(i+1)-C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i) equals ψ+120°, and C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i)-Cγ(i) equals χ₁-120° [11]. When these connecting dihedrals form specific combinations, particularly {-60°,+60°} or {+60°,-60°}, significant steric clashes occur due to a phenomenon analogous to pentane interference in organic chemistry [11].

Molecular mechanics calculations using the CHARMM22 potential energy function demonstrate strong similarity with experimental distributions, indicating that proteins generally attain their lowest energy rotamers with respect to local backbone-side-chain interactions [12] [19]. This agreement between statistical preferences and computational energetics validates the physical relevance of the observed backbone-dependent trends and supports the use of these libraries in physics-based modeling approaches.

Characteristic Backbone-Rotamer Interaction Patterns

Table 2: Characteristic Backbone-Dependent Steric Interactions for χ₁ Rotamers

| χ₁ Rotamer | Backbone Atom | Problematic φ Values | Problematic ψ Values | Structural Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gauche+ (g+) | N(i+1) | - | -60° | N(i+1)-C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i) = ψ+120° = +60°; C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i)-Cγ(i) = χ₁-120° = -60° |

| gauche+ (g+) | O(i) | - | +120° | Steric clash between O(i) and Cγ(i) |

| trans (t) | N(i+1) | - | 180° | N(i+1)-C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i) = ψ+120° = -60°; C(i)-Cα(i)-Cβ(i)-Cγ(i) = χ₁-120° = +60° |

| trans (t) | O(i) | - | 0° | Steric clash between O(i) and Cγ(i) |

| gauche+ (g+) | C(i-1) | +60° | - | Steric clash between C(i-1) and Cγ(i) |

| gauche- (g-) | C(i-1) | -180° | - | Steric clash between C(i-1) and Cγ(i) |

The relationship between backbone conformation and side-chain rotamer preferences follows specific, predictable patterns that can be visualized through their distinctive signatures on the Ramachandran map.

Valine provides an instructive example of these principles in action. Unlike most amino acids where the gauche+ or trans rotamers dominate, valine predominantly adopts the trans rotamer (χ₁~180°) because both its gauche+ and gauche- conformations encounter steric clashes with backbone atoms across most ψ values [11]. The two valine γ heavy atoms (CG1 and CG2) are positioned at χ₁ and χ₁+120° respectively, creating a situation where at most φ and ψ values, only one rotamer is sterically allowed [11]. This example illustrates how the specific geometry of side-chain atoms creates unique backbone-dependent patterns for each amino acid type.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rotamer Libraries | Dunbrack Rotamer Library (http://dunbrack.fccc.edu) | Provides backbone-dependent rotamer probabilities and statistics [17] | Structure prediction, protein design, molecular modeling |

| Molecular Modeling Suites | Rosetta | Uses rotamer libraries as scoring function for structure optimization [17] [11] | Protein design, structure prediction, docking |

| Molecular Mechanics Force Fields | CHARMM22 | Validates energy correspondence with statistical distributions [12] [19] | Molecular dynamics, energy calculations, structure refinement |

| Structural Biology Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of high-resolution structures for library development [12] | Data mining, statistical analysis, method validation |

| Specialized Software | BASILISK | Generative probabilistic model of side chains in continuous space [18] | Continuous sampling, protein design, force field integration |

| Statistical Packages | Custom Bayesian Analysis Tools | Implements kernel density estimation with von Mises distributions [17] | Library development, probability estimation, smoothing |

The effective implementation of Bayesian rotamer analysis requires specialized computational resources and methodologies. The Dunbrack Rotamer Library, available through the Dunbrack lab website, provides regularly updated backbone-dependent rotamer statistics at varying levels of smoothing, enabling researchers to select the appropriate resolution for their specific application [17]. For molecular modeling and design, the Rosetta software suite incorporates these libraries as energy terms in its scoring function, using the negative log probability of rotamers given backbone conformation (E = -ln(P(rotamer|φ,ψ))) to guide structure optimization [11]. This integration enables efficient side-chain packing algorithms that are essential for protein structure prediction and design.

For specialized applications in NMR structure determination, Bayesian approaches have been developed that integrate rotamer libraries with unassigned NOESY data through Markov random field models [21]. These methods employ deterministic dead-end elimination (DEE) and A* search algorithms to find global optimum solutions that maximize posterior probability, providing a rigorous approach to high-resolution structure determination without requiring laborious NOE assignment [21]. The integration of experimental data with prior structural knowledge represents a powerful application of the Bayesian framework to experimental structural biology.

Applications in Structural Biology and Protein Engineering

The Bayesian backbone-dependent rotamer libraries have enabled significant advances across multiple domains of structural biology. In protein structure prediction, these libraries provide critical constraints for side-chain placement during homology modeling and ab initio structure prediction [12] [22]. The backbone-dependent probabilities serve as informative priors that dramatically reduce the conformational search space while maintaining physical relevance. In protein design, rotamer libraries form the discrete search space for identifying sequence and conformation combinations that stabilize target structures [17] [23]. The log probabilities of rotamers are frequently incorporated as statistical energy terms that complement physics-based force fields.

For structure determination and refinement, both in X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy, backbone-dependent rotamer libraries serve as validation metrics and constraints [12] [21]. In X-ray crystallography, they guide the fitting of side chains into electron density, while in NMR they help interpret NOE data and validate proposed structures [21]. The recent integration of machine learning approaches with rotamer-based modeling has further expanded these applications, with neural network models learning the backbone-dependent joint rotamer angle distribution directly from structural data [23]. These learned models achieve performance comparable to established methods like Rosetta in recovering native rotamers and designing stable proteins, demonstrating the continuing relevance of accurate rotamer modeling in modern computational structural biology [23].

The development of continuous probabilistic models like BASILISK, which formulate generative models of side-chain conformational space without discrete rotamer bins, represents an important future direction for the field [18]. By operating entirely in continuous space and employing directional statistics with von Mises distributions, these approaches avoid the discretization artifacts inherent in traditional rotamer libraries while maintaining the efficiency benefits of a probabilistic framework [18]. This integration of Bayesian principles with continuous conformational sampling promises to further enhance the accuracy and applicability of rotamer-based modeling in structural biology and protein engineering.

The study of protein side-chain rotamers (rotational isomers) has long been foundational to structural biology, primarily relying on static snapshots from crystallographic data. These snapshots have been codified into rotamer libraries—statistical summaries of preferred side-chain conformations—which are indispensable for structure prediction, validation, and homology modeling. However, the intrinsic dynamics of proteins in solution are lost in these static representations. This whitepaper frames the emerging paradigm of rotamer dynamics (RD) within a broader thesis on statistical conformations, arguing that integrating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with rotamer analysis provides a critical, dynamic dimension to our understanding. By moving beyond the crystal structure, RD analysis reveals the temporal evolution of side-chain conformations, offering profound insights into protein function, folding, molecular recognition, and creating new opportunities for drug development by characterizing flexible binding sites.

The Foundation: Static Rotamer Libraries

A rotamer describes the side-chain conformation of an amino acid residue, defined by its χ torsional angles [24] [1]. The construction of rotamer libraries is a classic achievement in the field of statistical protein conformation research. These libraries classify rotamers in a way that reflects their frequency in nature, based on two primary approaches:

- Crystal-structure-based libraries: Built from statistical analysis of side-chain conformations in high-resolution protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The "penultimate rotamer library" is a key example, developed using highly refined structures to minimize internal atomic clashes and uncertain residues [24] [1].

- Dynamics-based libraries: Constructed from computational studies, such as the dynameomics library, which uses MD simulations to predict rotamers in a solution environment [1].

A significant advancement was the development of backbone-dependent rotamer libraries. Research demonstrated that amino acid side-chains have rotamer preferences dependent on the backbone dihedral angles φ and ψ [13] [25]. This represented a major improvement over backbone-independent libraries, as simple conformational analysis based on steric repulsions (e.g., the 'butane' and 'syn-pentane' effects) can account for many observed features of this backbone dependence [13].

The Paradigm Shift: Why Dynamics Matter

While invaluable, traditional libraries present a static, time-averaged view. They identify favorable conformations but cannot capture:

- The kinetics of transition between rotameric states.

- The population distribution of rotamers in solution over time.

- The correlation between side-chain dynamics and backbone motion.

- The impact of solvent and thermodynamic fluctuations on side-chain flexibility.

Rotamer Dynamics (RD) analysis directly addresses these limitations by leveraging Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. MD simulates the in silico behavior of molecules in solution, tracking the trajectories of all atoms over time based on molecular force fields. This allows researchers to observe and quantify the dynamic behavior of rotamers, identifying favorable side-chain conformations that exist in a physiological, solvated state [24] [1].

Table 1: Key Rotamer Libraries and Their Characteristics

| Library Name | Type | Basis | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penultimate [24] [1] | Backbone-independent | High-quality crystal structures | Stringent quality; 153 rotamer classes; simple nomenclature (p, t, m) |

| Dunbrack [13] [25] | Backbone-dependent | Crystal structures | Side-chain preferences depend on backbone φ and ψ angles |

| Dynameomics [1] | Dynamics-based | MD simulations (>31 ns at 25°C) | Predicts rotamers in solution; validated with NMR data |

Computational Methodologies for Rotamer Dynamics

The core of RD analysis lies in processing MD simulation data to track and classify side-chain conformations over time.

A Standardized Protocol for RD Analysis

A proven protocol for RD analysis uses accessible computational tools to extract rotamer information from MD trajectories [1]:

- Trajectory Preparation: The MD simulation trajectory is first processed to isolate each frame into separate Protein Data Bank (PDB) files. This can be achieved using the

cpptrajmodule in the AMBER MD package. - Torsional Angle Extraction: For each individual frame (now a PDB file), the torsional (χ) angles for each residue are calculated. The

Bio3Dmodule in the R programming language is capable of performing this extraction, requiring only residue definitions rather than manual specification of every dihedral angle. - Rotamer Classification: The extracted χ angles are then classified into specific rotamer states according to a defined rotamer library, such as the penultimate library. This classification can be implemented programmatically using if/else statements in R, assigning a rotamer label (e.g.,

ptpfor Methionine) for every residue in every frame.

This workflow transforms a raw MD trajectory into a time-series of rotamer states, enabling quantitative analysis of rotameric behavior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful RD analysis relies on a suite of specialized software tools and libraries.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Rotamer Dynamics Research

| Tool Name | Category | Function in RD Analysis | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER (sander, cpptraj) [1] | MD Simulation & Analysis | Runs MD simulations; processes trajectories | Converts trajectory frames to individual PDB files |

| GROMACS [1] | MD Simulation | Alternative MD suite for simulation | Can define dihedral angles in an index file for analysis |

| CHARMM [1] | MD Simulation & Analysis | Alternative MD suite | Uses correlation functions to study χ angle fluctuations |

| R Language / Bio3D [24] [1] | Statistical Analysis | Extracts torsional angles from PDB files | Works on single structures, ideal for automated frame-by-frame analysis |

| Penultimate Rotamer Library [24] [1] | Rotamer Reference | Provides benchmark for rotamer classification | Backbone-independent; countable rotamers easy to visualize |

| Upside [26] | Coarse-Grained MD | High-throughput simulation; chi1 prediction | Efficient for large-scale studies and specific rotamer prediction |

| VMD / MDTraj [1] [26] | Trajectory Visualization & Analysis | Loads and visualizes trajectories; converts file formats | Aids in inspection and presentation of dynamic structural changes |

Advanced Concepts: Continuous Rotamers in Protein Design

A significant innovation extending from dynamic rotamer analysis is the concept of continuous rotamers. In contrast to the traditional rigid-rotamer model used in protein design—where a single discrete conformation represents an entire cluster of side-chain conformations—the continuous-rotamer model allows each rotamer to represent a region in χ-angle space [27].

This approach is critical for accurate protein design. Rigid rotamers can produce steric clashes that would cause a design algorithm to discard a potentially optimal sequence, whereas continuous rotamers can minimize within their specified region to achieve a better-packed, lower-energy structure. Studies show that protein redesign using continuous rotamers results in sequences that are different, have lower energy, and are more similar to native sequences compared to those from a rigid-rotamer model [27]. Algorithms like iMinDEE make searching this continuous space computationally feasible, ensuring the finding of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC) for continuously minimized side chains.

Applications in Protein Science and Drug Development

RD analysis is not merely an academic exercise; it has tangible applications across structural and molecular biology.

Table 3: Key Applications of Rotamer Dynamics Analysis

| Application Field | Specific Use-Case | Impact of RD Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Folding & Stability | Study of structural changes caused by mutations | Identifies how mutations alter side-chain flexibility and energy landscapes, impacting stability. |

| Protein-Protein & Protein-Ligand Interactions | Study of rotamer-rotamer relationships in binding interfaces; preparation for molecular docking | Characterizes the flexibility of side chains in binding sites, leading to more accurate docking preparations. |

| Functional Analysis | Understanding allostery and enzyme mechanism | Serves as a guide to link side-chain dynamics to protein function, e.g., in catalytic cycles. |

| Drug Development | Investigating drug resistance and optimizing binders | Reveals how resistant mutations alter target dynamics; identifies cryptic pockets and transient states for targeting. |

| Force Field Refinement | Improving coarse-grained MD accuracy | Provides parameters for more accurate and faster simulations. |

A Practical Workflow: Visualization and Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflow for conducting a Rotamer Dynamics study, from simulation to analysis.

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the field of Rotamer Dynamics must overcome several challenges to mature.

A primary challenge is validation. The predictions made by RD analysis from in silico simulations require confirmation through easy and inexpensive wet-lab methods [24] [1]. While techniques like NMR relaxation, which measures side-chain order parameters, can provide experimental validation, this realm is yet to be fully explored [1].

Future progress will likely involve:

- Tighter integration of experimental data (e.g., NMR, time-resolved crystallography) to benchmark and refine MD-based RD predictions.

- Development of standardized analysis packages that make RD accessible to non-specialists, moving beyond custom scripts in R and AMBER.

- Application in industrial drug discovery pipelines to systematically account for target flexibility and dynamics in lead optimization.

The analysis of rotamer dynamics represents a necessary evolution in the study of protein side-chain statistical conformations. By leveraging the power of molecular dynamics simulations, researchers can move beyond the static snapshots provided by traditional rotamer libraries and begin to appreciate the full conformational landscape that proteins explore in solution. This dynamic perspective, framed within the broader thesis of statistical rotamer research, offers a more complete understanding of the interplay between protein structure, dynamics, and function. As methodologies for RD analysis become more robust and accessible, they promise to deepen fundamental biological insights and accelerate the rational design of therapeutics that target dynamic, rather than static, protein structures.

Protein side-chain rotamers—discrete, energetically favorable conformations of amino acid side-chains—are a foundational concept in structural biology and computational biophysics. The statistical analysis of these conformations has led to the development of rotamer libraries, which are essential for protein structure prediction, homology modeling, protein design, and drug discovery. These libraries quantify the probabilities of specific side-chain dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4) based on contextual factors like backbone conformation or sequence environment. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to three key resources that offer complementary data for rotamer research: the Protein Data Bank (PDB) as the primary source of experimental structural data, Dynameomics for dynamic simulation data, and SwissSidechain for non-natural amino acid parameters. Together, they provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating the statistical conformations of protein side-chains, enabling advances from fundamental science to applied drug development.

The table below summarizes the core focus, primary content, and key applications of the three databases, highlighting their distinct roles in rotamer research.

Table 1: Core Databases for Rotamer Research

| Resource | Core Focus & Data Type | Primary Content | Key Rotamer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [28] [29] | Experimental 3D structures; Static coordinates | >200,000 experimentally determined structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complexes via MX, 3DEM, NMR [29] | Source for deriving backbone-dependent rotamer libraries; Validation of computational models |

| Dynameomics [30] [31] | Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations; Time-resolved data | Thousands of MD simulations of >1000 proteins; ~340 µs of simulation time; Native-state and unfolding pathways [30] [31] | Study of rotamer dynamics and transitions; Folding/unfolding mechanisms; Solvation effects |

| SwissSidechain [32] [33] | Non-natural amino acids; Parametric data | Structural and molecular mechanics data for 210 non-natural sidechains (L- and D-conformations) [32] | Drug design: incorporating non-natural amino acids; Improving peptide pharmacological properties |

The Protein Data Bank: The Experimental Foundation

Resource Architecture and Data Provenance

The Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB) serves as the US data center for the global PDB archive, a founding member of the Worldwide PDB (wwPDB) partnership [29]. As the Archive Keeper, the RCSB PDB is responsible for the security and weekly updates of the archive, ensuring adherence to the FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) and FACT (Fairness, Accuracy, Confidentiality, and Transparency) principles [29]. The archive has been accredited by CoreTrustSeal, underscoring its reliability as a core data resource for the scientific community. Structures are deposited and processed through the unified wwPDB OneDep system, which standardizes data deposition, validation, and biocuration across all supported experimental methods [29].

Experimental Methods and Data Metrics

The PDB archive encompasses structures determined primarily through three experimental methods, each contributing unique insights and possessing specific characteristics relevant to rotamer analysis:

- Macromolecular Crystallography (MX): The dominant method in the archive, with over 166,000 structures as of mid-2022. MX typically provides high-resolution data (median resolution ~2.0 Å), allowing for precise rotamer assignment, though the crystal environment can influence side-chain conformations [29].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Contributes over 13,000 structures. NMR provides information on dynamics and ensemble conformations in solution, offering a complementary perspective to static crystal structures [29].

- 3D Electron Microscopy (3DEM): The fastest-growing method, with exponential growth in deposits. While traditionally lower resolution, recent technical advances have enabled structures at near-atomic resolution (e.g., 1.15 Å for apoferritin, PDB ID: 7a6a) [29].

Table 2: Key Metrics of the PDB Archive (Data as of mid-2022) [29]

| Metric | Value | Significance for Rotamer Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Total Structures | ~200,000 | Vast statistical base for deriving rotamer probabilities |

| Total Residues | >200 million | Enables analysis of context-dependent rotamer distributions |

| Dominant Method | Macromolecular Crystallography (MX) | Provides high-resolution, static snapshots for library building |

| Structures per Year | ~10,000+ (MX) | Continuous growth refines and expands rotamer statistics |

Protocol: Deriving a Backbone-Dependent Rotamer Library from the PDB

The following methodology outlines the general process for creating a backbone-dependent rotamer library from the PDB archive, a foundational technique in structural bioinformatics [34].

Data Curation and Selection:

- Obtain a representative subset of PDB structures. Selection criteria typically include:

- High resolution (e.g., ≤ 1.75 Å) [32] to ensure precise atomic coordinates.

- Low sequence identity (e.g., < 25-30%) to avoid over-representation of homologous proteins.

- Removal of structures with significant structural defects or missing atoms.

- Obtain a representative subset of PDB structures. Selection criteria typically include:

Data Extraction and Angle Calculation:

- For each amino acid in each selected structure, extract the following data:

- Backbone dihedral angles (φ and ψ) for the residue of interest.

- Side-chain dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4) as relevant for the specific amino acid type.

- For each amino acid in each selected structure, extract the following data:

Bin Assignment and Probability Calculation:

- Discretize the backbone conformational space (φ/ψ angles) into bins (e.g., 10° x 10°).

- Within each (φ/ψ) bin, identify the observed side-chain conformations.

- Cluster the side-chain dihedral angles into discrete rotameric states (e.g., using definitions like gauche(+), trans, gauche(-) for χ1) [35].

- Calculate the probability of each rotamer in a given backbone bin as its frequency of occurrence: P(rotamer | φ, ψ, AA).

Library Assembly:

- Compile the results into a searchable library where, for a given amino acid type and backbone conformation, one can retrieve a list of possible rotamers and their associated probabilities and average dihedral angles.

Workflow for Building a Rotamer Library from the PDB

Dynameomics: The Dynamic Simulation Resource

Project Scope and Simulation Strategy

The Dynameomics project was established to address the critical gap in understanding protein dynamics and folding—the "fourth dimension" of structural biology [30]. Its goal is comprehensive coverage of protein fold space through large-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. The project is built upon a Consensus Domain Dictionary (CDD) that integrates three major domain classification systems—SCOP, CATH, and Dali—to create a non-redundant set of metafolds [30]. By simulating representative proteins from these metafolds, Dynameomics ensures broad coverage of globular protein dynamics. To date, the project has performed over 11,000 simulations of more than 2,000 unique proteins, totaling over 340 microseconds of aggregated simulation time [31].

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Rotamer Analysis

The following protocol details the specific computational methodology employed by the Dynameomics project to generate data on side-chain dynamics and rotamer populations [30].

Target Selection and System Preparation:

- Target Selection: Choose fold representatives from the Consensus Domain Dictionary, prioritizing structures with high quality, medical relevance, and minimal missing atoms [30].

- Structure Preparation: Obtain coordinates from the PDB. Add any missing atoms using computational modeling tools.

- Solvation: Solvate the protein structure in explicit water using the experimental density for the target temperature. The Dynameomics project uses the flexible 3-center (F3C) water model [30].

Simulation Execution:

- Force Field: Utilize an all-atom force field (e.g., the force field developed by Levitt et al. [30]) to describe atomic interactions.

- Simulation Conditions:

- Perform at least one native state simulation at 298 K for a minimum of 31 ns.

- Perform multiple unfolding simulations at 498 K (at least two for 31 ns and three for 2 ns) to map unfolding pathways and denatured states [30].

- Software: Conduct simulations using specialized software like in lucem molecular mechanics (ilmm) [30].

Data Analysis for Rotamer Libraries:

- Trajectory Analysis: From the saved simulation trajectories, extract the time series of side-chain dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, etc.) for all residues.

- Rotamer Assignment: Assign each sampled side-chain conformation to a discrete rotamer state based on its dihedral angles.

- Population Calculation: Calculate the population (probability) of each rotamer state as the fraction of simulation time the side-chain occupies that state. This provides a dynamics-weighted view of rotamer preferences, capturing both native-state fluctuations and transition pathways.

Table 3: Dynameomics Simulation Strategy and Output

| Aspect | Specification | Value for Rotamer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Temperature | 298 K (Native), 498 K (Unfolding) | Captures equilibrium fluctuations and forced transitions |

| Simulation Duration | 31 ns (Native), 2-31 ns (Unfolding) | Allows for observation of rotamer interconversions |

| Number of Proteins | >1000 unique proteins [30] | Covers a wide range of structural contexts and folds |

| Public Data | Native simulations for Top 100 folds [30] | Freely accessible resource for the community |

SwissSidechain: Extending to Non-Natural Amino Acids

Database Composition and Parametric Data

SwissSidechain addresses a critical niche in structural bioinformatics and drug design by providing data for non-natural amino acids. The database contains 210 non-natural sidechains in both L- and D-conformations, in addition to the 20 natural ones [32]. For each sidechain, it provides a comprehensive set of structural and molecular mechanics data, including: 3D coordinates (in PDB and MOL2 formats), chemical structure (SMILES), physico-chemical properties (partial charges, LogP, bond/angle/torsion constants), and most importantly, backbone-dependent rotamer libraries [32]. The selection of sidechains includes those with available structural data in the PDB and those that are commercially available and frequently used in biochemistry and drug design [32].

Protocol: Incorporating a Non-Natural Amino Acid into a Protein Structure

This protocol describes how to use SwissSidechain data to model a non-natural amino acid into an existing protein structure, a common task in rational drug design and protein engineering [32].

Sidechain Selection and Data Retrieval:

- Identify the target natural amino acid in the protein structure to be mutated.

- Browse or search the SwissSidechain database based on desired physico-chemical properties (e.g., volume, hydrophobicity/LogP) or specific functional groups [32].

- Download the relevant data files for the chosen non-natural sidechain, including its rotamer library and topology/parameter files for molecular mechanics software.

Rotamer Library Generation:

- For natural sidechains, SwissSidechain uses statistics from high-resolution X-ray structures (≤1.75 Å) [32].

- For non-natural sidechains, a combined physics-based and knowledge-based approach is used:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Trajectories: The probability of each rotamer is computed based on MD simulations.

- Renormalization: The probabilities for the first dihedral angles (χ1) are renormalized using distributions from experimental natural sidechain libraries [32].

- For D-amino acids, the probabilities are derived from the mirror-image L-conformations, adjusting for the inverted backbone dihedral angles [32].

Structural Modeling and Optimization:

- Replace the coordinates of the native sidechain with those of the non-natural sidechain, sampling from its rotamer library.

- Use the provided plugins for visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, UCSF Chimera) to inspect the fit within the protein structure, assessing steric clashes and potential interactions.

- For advanced applications, use the topology files with simulation packages like CHARMM or GROMACS to perform energy minimization or molecular dynamics simulations to relax and validate the modeled structure [32].

Advanced Rotamer Library Types and Applications

Beyond the standard backbone-dependent libraries derived from the PDB, more sophisticated, context-aware libraries have been developed to improve the accuracy of side-chain modeling.

Table 4: Types of Rotamer Libraries and Their Characteristics

| Library Type | Contextual Information | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Backbone-Independent [36] | Amino acid type only | Averages over all backbone conformations; Useful for coarse-grained modeling |

| Backbone-Dependent [34] | Local backbone (φ/ψ) angles | Standard for protein structure prediction; Improves discriminative power |

| Protein-Dependent [34] | Full protein backbone structure | Encodes spatially local information via MRF; Higher accuracy than backbone-dependent |

| Sequence-Dependent [36] | Identity of adjacent amino acids | Captures local sequence effects on rotamers; Useful in peptide modeling and design |

Protein-Dependent Rotamer Libraries

A protein-dependent rotamer library represents a significant advancement by encoding structural information from all spatially neighboring residues, not just the local backbone. The methodology involves [34]:

- Modeling: The protein structure is modeled as a Markov Random Field (MRF), where residues are vertices in an interaction graph.

- Energy Function: An energy function (e.g., from Scwrl3) is used to define the potentials within the MRF.

- Inference: Probabilistic inference algorithms, such as loopy belief propagation (LBP), are used to compute the marginal probability distributions for the rotamers of each residue.

- Re-ranking: The rotamers from a standard backbone-dependent library are re-ranked based on these computed marginal probabilities, which account for the specific structural environment of the residue in the query protein [34].

This approach has been demonstrated to significantly outperform standard backbone-dependent libraries in side-chain prediction accuracy and rotamer ranking ability [34].

Creating a Protein-Dependent Rotamer Library

The table below lists key computational and data resources essential for conducting advanced research in the field of protein side-chain conformations and rotamer libraries.

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Rotamer Studies

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Rotamer Research |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB [28] [29] | Data Repository | Primary source of experimental structural data for deriving and validating rotamer libraries. |

| Dynameomics Database [30] [31] | Simulation Database | Provides dynamic data on rotamer populations, transitions, and folding/unfolding behavior. |

| SwissSidechain [32] [33] | Parametric Database | Supplies rotamer libraries and molecular parameters for non-natural amino acids for drug design. |

| CHARMM / GROMACS | Simulation Software | Molecular dynamics packages used to run simulations (e.g., like those in Dynameomics) and perform free energy calculations with non-natural amino acids [32]. |

| PyMOL / UCSF Chimera | Visualization Software | Used to visualize and analyze protein structures and rotamer conformations; SwissSidechain provides plugins for these [32]. |

| Markov Random Field (MRF) | Statistical Model | Underlying framework for advanced, protein-dependent rotamer libraries that account for full structural context [34]. |

Predicting and Applying Rotamers in Protein Engineering and Design

The prediction of protein side-chain conformations, or rotamers, represents a cornerstone problem in computational structural biology. The ability to accurately place side chains onto a protein backbone is indispensable for applications ranging from homology modeling and protein design to drug discovery and functional analysis. The core challenge lies in efficiently navigating the vast combinatorial space of possible side-chain conformations to identify the most biologically relevant and energetically favorable arrangements. This in-depth technical guide examines the three pivotal algorithms that form the backbone of modern side-chain prediction systems: rotamer library sampling, dead-end elimination, and simulated annealing. These methodologies are fundamentally interconnected through their shared foundation in the statistical analysis of side-chain conformations derived from experimentally determined protein structures. The thesis of this whitepaper is that the continued evolution and integration of these core algorithms, informed by an increasingly sophisticated understanding of conformational heterogeneity and energy landscapes, is essential for advancing the accuracy and applicability of computational protein modeling.

The statistical nature of side-chain conformations is well-established, with observed torsion angle distributions in high-resolution structures often correlating with Boltzmann-type distributions of model compound energies [37]. This statistical relationship provides the theoretical underpinning for rotamer libraries and energy functions used in prediction algorithms. Furthermore, recent large-scale analyses have quantitatively demonstrated that protein side chains exhibit significant conformational heterogeneity, which can be systematically categorized into distinct types: fixed conformations, discrete conformations, cloud conformations, and flexible conformations [5]. This heterogeneity is not merely structural noise but is functionally significant, as ligand binding has been shown to remodel protein side-chain conformational heterogeneity in ways that can impact binding affinity and allosteric regulation [38]. Understanding these statistical conformational patterns is therefore crucial for developing more physiologically accurate prediction algorithms.

Foundational Concepts and Statistical Framework

Rotamer Libraries: Encoding Conformational Statistics

Rotamer libraries systematically quantify the observed conformational preferences of amino acid side chains in experimentally determined protein structures. These libraries serve as essential prior distributions that constrain the search space for side-chain prediction algorithms. Two primary types of libraries have been developed:

- Backbone-independent libraries encode only amino acid-specific conformational frequencies, providing a baseline statistical model [34].

- Backbone-dependent libraries incorporate the influence of local backbone conformation (ϕ and ψ angles) on side-chain dihedral angle distributions, significantly improving discriminative power by accounting for local structural context [39] [34].

A more recent innovation is the protein-dependent rotamer library, which extends the contextual information beyond local backbone to include the structural information of all spatially neighboring residues. By modeling the protein structure as a Markov Random Field and using inference algorithms to compute marginal distributions, protein-dependent libraries re-rank rotamers based on their specific environmental context, achieving significant improvements in prediction accuracy without global optimization [39] [34].

Table 1: Classification and Evolution of Rotamer Libraries

| Library Type | Contextual Information Encoded | Key Advantages | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Backbone-Independent | Amino acid identity only | Computational simplicity; baseline statistics | Early side-chain prediction methods |

| Backbone-Dependent | Amino acid identity + local ϕ/ψ angles | Improved discriminative power; reduced search space | SCWRL, Rosetta |

| Protein-Dependent | Amino acid identity + full spatial environment | Highest accuracy; context-specific probabilities | Advanced protein design |

Energy Functions: The Driving Force of Optimization

Side-chain prediction is typically formulated as a global optimization problem where the goal is to find the combination of rotamers that minimizes the total energy of the system. The energy function, or scoring function, quantifies the thermodynamic stability of a given side-chain configuration. While specific functional forms vary, most incorporate:

- Van der Waals interactions to model steric repulsion and London dispersion forces.

- Electrostatic interactions between partial atomic charges.

- Hydrogen bonding terms to capture directional polar interactions.

- Solvation effects, either implicitly or explicitly.

These energy terms can be parameterized using first-principles physics (e.g., OPLS or CHARMM parameters) [10], empirical knowledge derived from structural databases, or hybrid approaches. The development of accurate, well-balanced energy functions remains an active area of research, as the accuracy of any search algorithm is ultimately limited by the quality of the energy surface it navigates.

Core Algorithmic Methodologies

Rotamer Library Sampling: Managing Combinatorial Complexity

The fundamental challenge in side-chain prediction is the exponential explosion of possible conformations. A protein with N residues, each with an average of R rotameric states, has R^N possible combinations. Rotamer library sampling addresses this by discretizing the continuous conformational space into a manageable set of statistically probable states.

Modern implementations often employ extremely large libraries to sample conformational space finely. For example, one algorithm utilizing the OPLS force field employed a library of nearly 50,000 rotamers, constructed by sampling dihedral angles in 5° steps (±15° from ideal values), resulting in 7 discrete positions per rotatable bond [10]. While such extensive sampling increases computational cost, it provides critical resolution for identifying optimal conformations and can yield prediction accuracies exceeding 90% for χ1 and 83% for χ1+2 on buried residues when placed on accurate backbone traces [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Side-Chain Prediction Algorithms

| Algorithm/Method | χ1 Accuracy (%) | χ1+2 Accuracy (%) | Overall RMSD (Å) | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCN (Simulated Annealing) | 92 | 83 | 1.0 | Buried residues only (80% of total) [10] |

| Protein-dependent Library | Significant improvement over backbone-dependent | N/A | N/A | Without global optimization [34] |

| Multiconformer Modeling | N/A | N/A | N/A | Quantifies heterogeneity changes upon ligand binding [38] |

Diagram 1: Generalized Rotamer Sampling Workflow (Width: 760px)

Dead-End Elimination (DEE): Pruning the Search Space

The Dead-End Elimination (DEE) algorithm provides a powerful, mathematically rigorous method for reducing the combinatorial complexity of the side-chain prediction problem by identifying and eliminating rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation (GMEC). The core principle of DEE is to eliminate a rotamer i_r for a residue i if another rotamer i_s of the same residue exists that is always of lower energy, regardless of the conformations of all other residues in the protein.

The fundamental DEE criterion can be expressed as:

Where E(i_r) is the self-energy of rotamer i_r, and E(i_r, j_t) is the pairwise energy between rotamer i_r and rotamer j_t from residue j. If this inequality holds, rotamer i_r is provably not part of the GMEC and can be eliminated from further consideration [40].

Experimental Protocol for DEE Implementation:

- Initialization: Load the protein backbone structure and assign all possible rotamers to each side-chain position from a predefined rotamer library.

- Self-Energy Calculation: Compute the self-energy for each rotamer, which includes its internal energy and interactions with the fixed backbone.