Protein Structure Analysis and Validation in 2025: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of protein structure analysis and validation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein Structure Analysis and Validation in 2025: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of protein structure analysis and validation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, explores the latest methodological advancements driven by AI and deep learning, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for challenging scenarios. A dedicated section on validation and comparative analysis equips readers with the knowledge to rigorously assess model quality, a critical step for ensuring reliability in structural biology and structure-based drug design. By synthesizing information on tools like AlphaFold, DeepSCFold, BeStSel, and various validation servers, this guide aims to be an essential resource for leveraging protein structural data to accelerate biomedical discovery.

The Fundamental Principles of Protein Structure and Analysis

Why 3D Structure Determines Biological Function

The central dogma of molecular biology posits that biological information flows from DNA sequence to RNA to protein. A foundational hypothesis, powerfully articulated by Christian Anfinsen, states that a protein's native three-dimensional conformation is determined solely by its amino acid sequence [1]. This structure, in turn, dictates the protein's specific biological function. Proteins are the primary workhorses of the cell, executing nearly all cellular processes—including catalysis, signal transduction, transport, and immune defense—by interacting with other molecules with exquisite specificity. These functions are impossible without precise spatial arrangement of amino acid residues into active sites, binding pockets, and interaction interfaces. The 3D structure of a protein therefore creates a unique molecular landscape that enables selective binding and chemical activity, making the relationship between structure and function one of the most critical concepts in modern biology and drug discovery.

Recent revolutions in artificial intelligence and machine learning, exemplified by AlphaFold2, have dramatically underscored this principle by demonstrating that protein structure can be predicted from sequence with remarkable accuracy [1] [2]. This breakthrough, recognized with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, confirms the deterministic relationship between sequence and structure and opens new frontiers for exploring biological function at a molecular level. This review examines the fundamental principles linking protein structure to biological activity, details the experimental and computational methods for structure determination and validation, and explores applications in therapeutic development, all within the context of ongoing research in protein structure analysis and validation methods.

Fundamental Principles Linking Structure and Function

The Sequence-Structure-Function Paradigm

The flow of information from amino acid sequence to three-dimensional structure to biological function is the cornerstone of structural biology. The sequence encodes the thermodynamic landscape that guides protein folding into a specific, stable, three-dimensional conformation [1]. This native state represents a global energy minimum where the totality of interatomic interactions—including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions, and hydrophobic effects—is optimized [3]. This structurally ordered state competes with the conformational entropy of the unfolded chain, resulting in a well-defined near-native structural ensemble [3].

Function arises directly from this architecture. The specific spatial orientation of amino acid side chains creates unique microenvironments capable of remarkable chemical feats. For instance, the precise arrangement of catalytic residues in an enzyme's active site lowers the activation energy for biochemical reactions, enabling efficient catalysis. Similarly, the structure of hemoglobin creates binding pockets for heme groups that exhibit cooperative oxygen binding, a phenomenon that would be impossible without precise quaternary arrangement [1]. The structural complementarity between proteins and their ligands—whether small molecules, nucleic acids, or other proteins—enables the selective recognition that underlies most cellular processes [4].

Structural Conservation and Functional Adaptation

Evolutionary processes highlight the primacy of structure over sequence in maintaining biological function. Protein folds and functional sites are often more conserved than amino acid sequences, with structurally similar binding patterns observed across diverse protein-protein interactions [4]. This structural conservation occurs because the physical and chemical requirements for specific functions constrain the evolutionary possibilities at key structural positions. Consequently, proteins with vastly different sequences can converge on similar folds and functions, while minor structural changes in critical regions can completely abolish function or lead to disease.

Table 1: Key Structural Elements and Their Functional Roles

| Structural Element | Functional Role | Representative Example |

|---|---|---|

| Active Site | Contains catalytic residues for biochemical transformations | Serine protease triad (His, Asp, Ser) |

| Binding Pocket/Cleft | Recognizes specific ligands through shape and chemical complementarity | ATP-binding pocket in kinases |

| Protein-Protein Interface | Mediates specific interactions between polypeptide chains | Antibody-antigen binding surface |

| Allosteric Site | Binds effector molecules to regulate activity at distant sites | Hemoglobin heterotropic allosteric regulation |

| Transmembrane Domain | Anchors proteins in lipid bilayers and facilitates transport | G protein-coupled receptor helices |

Experimental Methodologies for Structure Determination

Determining protein structure experimentally remains essential for understanding function, despite advances in computational prediction. The three primary high-resolution techniques—X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM)—each provide unique insights into protein architecture and dynamics.

High-Resolution Structural Techniques

X-ray crystallography has been the workhorse of structural biology since the determination of myoglobin in 1958 [3]. This technique involves exposing protein crystals to X-rays and analyzing the resulting diffraction patterns to calculate electron density maps, which are then used to build atomic models. The resolution, determined by the quality of the crystals and the diffraction data, dictates the level of atomic detail visible. While crystallography provides precise structural snapshots, it has limitations: it requires high-quality crystals, may capture non-native conformations induced by crystal packing, and typically reveals minimal information about molecular dynamics [3].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei to determine protein structures in solution [3] [1]. Unlike crystallography, NMR can capture conformational dynamics and transitions, offering insights into protein flexibility and rare states [3]. This technique is particularly valuable for studying intrinsically disordered proteins and mapping interaction surfaces. However, traditional NMR faces size limitations, though methodological advances have progressively pushed these boundaries [3]. NMR generates structural ensembles that represent the conformational space sampled by the protein, providing a more dynamic view of structure [1].

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has recently revolutionized structural biology, especially for large complexes and membrane proteins that are difficult to crystallize [3]. This technique involves flash-freezing protein samples in vitreous ice and imaging them with electrons, followed by computational reconstruction to generate three-dimensional density maps. Technological advances in direct electron detectors and image processing software have propelled cryo-EM to achieve near-atomic resolution for many targets [3]. Its principal advantages include requiring small amounts of sample, capturing multiple conformational states, and visualizing proteins in near-native conditions.

Table 2: Comparison of Major Experimental Structure Determination Methods

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy | Cryo-EM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample State | Crystal | Solution | Vitreous ice |

| Size Range | No upper limit | Typically < 100 kDa | No upper limit, best for > 150 kDa |

| Resolution Range | Atomic (0.5-3.0 Å) | Atomic (1.5-3.0 Å) | Near-atomic to intermediate (1.8-4.5 Å) |

| Time Resolution | Static snapshot | Picoseconds to seconds | Static snapshot |

| Key Advantage | High resolution, well-established | Solution state, dynamics | Minimal sample prep, size flexibility |

| Principal Limitation | Requires crystallization, packing artifacts | Molecular weight limitations, complexity | Resolution variability, equipment cost |

Experimental Workflow and Validation

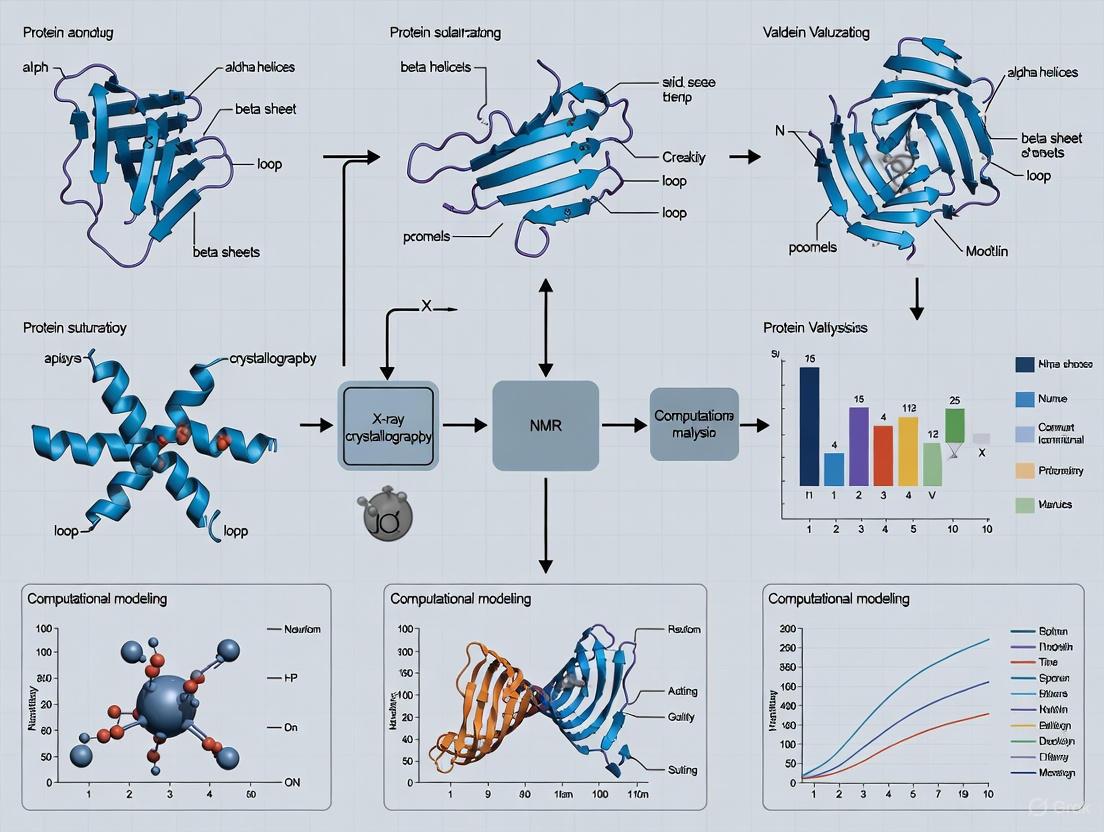

The process of determining protein structures involves careful sample preparation, data collection, model building, and rigorous validation. The following workflow diagram illustrates the generalized pathway from protein to validated structure:

Structural validation is a critical step ensuring the reliability and accuracy of determined models. Validation methods assess both the agreement between the model and experimental data and the model's geometric and stereochemical quality [5]. Key validation parameters include:

- R-factor and R-free: Statistical measures comparing calculated structure factors from the model to experimental data, with R-free calculated using a subset of data excluded from refinement to prevent overfitting [5].

- Ramachandran plot analysis: Assesses the backbone torsion angles of amino acid residues, identifying energetically favorable and unfavorable conformations [5].

- Rotamer analysis: Evaluates the side chain conformations for outliers from preferred rotameric states.

- Clashscore: Quantifies steric overlaps between atoms in the structure.

- pLDDT: In AlphaFold predictions, the predicted Local Distance Difference Test estimates the confidence in each residue's positioning [2].

These validation metrics help identify errors in model building and refinement, ensuring that structural interpretations and subsequent functional inferences are based on reliable atomic coordinates [5].

Computational Approaches for Structure Prediction and Analysis

The Rise of AI-Driven Structure Prediction

Computational methods have evolved from physical simulation-based approaches to knowledge-based methods and, most recently, to artificial intelligence-driven prediction. Early methods included threading, where target sequences were aligned to backbone templates of known structures [3], and fragment-based assembly, which built structures from libraries of short structural fragments [3]. The critical breakthrough came with the recognition that evolutionary information encoded in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) could reveal co-evolving residue pairs that contact each other in the folded structure—a principle known as direct coupling analysis (DCA) [3].

AlphaFold2 represents the culmination of these approaches, combining MSAs, structural templates, and a novel attention-based neural network architecture to achieve unprecedented accuracy in protein structure prediction [1] [2]. Its success in the CASP14 competition demonstrated that computational predictions could reach experimental accuracy for many targets [2]. The model's architecture enables it to reason about spatial relationships between residues and implicitly learn the physical rules of protein folding from the thousands of structures in the Protein Data Bank.

Following AlphaFold2's release, adaptations for predicting complexes have emerged. AlphaFold-Multimer extends the framework to protein-protein interactions, while newer methods like DeepSCFold further enhance accuracy by incorporating sequence-derived structural complementarity and interaction probability metrics [4]. DeepSCFold demonstrates particular improvement for challenging targets like antibody-antigen complexes, achieving 24.7% and 12.4% higher success rates for binding interface prediction compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [4].

Workflow for Computational Structure Prediction

The process of computational structure prediction, particularly for protein complexes, involves multiple stages of data gathering and analysis as illustrated below:

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Protein Structure Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | UniRef [4], UniProt [4] [1], Metaclust [4], BFD [4], MGnify [4] | Provide evolutionary information via homologous sequences for MSA construction |

| Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [4] [1], AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [2] | Archive experimentally determined and predicted structures for template-based modeling and validation |

| Specialized Databases | SAbDab (antibody structures) [4], Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank (BMRB) [1] | Provide domain-specific structural data for specialized applications |

| Computational Tools | AlphaFold-Multimer [4], DeepSCFold [4], RoseTTAFold [1], ESMFold [1] | Perform AI-driven protein structure and complex prediction from sequence |

| Validation Services | PROCHECK [5], MolProbity, SWISS-MODEL Workspace | Assess stereochemical quality and structural validity of protein models |

Applications in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Structure-Based Drug Design

Understanding protein structure at atomic resolution has transformed drug discovery by enabling rational drug design instead of purely empirical screening. Structure-based approaches analyze the three-dimensional properties of target proteins—typically enzymes, receptors, or other functionally significant molecules—to design small molecules that modulate their activity. Key applications include:

- Virtual screening: Computational docking of compound libraries into target binding sites to identify potential lead compounds.

- Lead optimization: Using structural information to guide chemical modifications that improve drug potency, selectivity, and pharmacokinetic properties.

- Allosteric modulator discovery: Identifying compounds that bind to regulatory sites rather than active sites, offering potentially finer control over protein function.

The determination of protein-ligand complex structures provides direct insight into molecular recognition patterns, hydrogen bonding networks, and hydrophobic interactions that drive binding affinity and specificity. This structural information is particularly valuable for addressing challenges like drug resistance, where atomic-level understanding of mutation effects can guide the design of next-generation therapeutics.

Understanding Disease Mechanisms

Many human diseases originate from alterations in protein structure that disrupt normal function. Missense mutations can cause misfolding, aggregation, or loss of functional activity, leading to pathological states. For example:

- In sickle cell anemia, a single glutamate-to-valine substitution in hemoglobin promotes polymerization under low oxygen conditions.

- In Alzheimer's disease, structural transitions in amyloid-β and tau proteins lead to pathogenic aggregation and neurofibrillary tangles.

- In cancer, mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressors often alter protein conformations to drive uncontrolled proliferation.

Structural biology provides the foundation for understanding these pathological mechanisms at the molecular level. The AlphaFold Database, with over 200 million predicted structures, has dramatically expanded access to structural models for disease-related proteins, enabling researchers worldwide to formulate and test hypotheses about genetic variants and their functional consequences [2].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite tremendous progress, significant challenges remain in protein structure analysis. Predicting and characterizing protein-protein interactions remains difficult, especially for transient, weak, or flexible complexes [6]. Particular challenges include host-pathogen interactions, complexes involving intrinsically disordered regions, and immune-related interactions [6]. These systems often lack clear co-evolutionary signals and exhibit considerable structural flexibility, complicating both experimental determination and computational prediction [4] [6].

Future advances will likely focus on predicting multiple conformational states and dynamic transitions rather than single static structures [1]. Integrating experimental data from cryo-EM, NMR, and mass spectrometry with computational approaches will be essential for capturing the full structural heterogeneity of proteins in solution [3] [1]. As one research group noted, "It appears highly likely that sequence encodes not just a single idealized 3D structure but also the conformational dynamics of a protein and, therefore, biochemical/biological function" [1]. The continued development of AI/ML methods trained on diverse structural and dynamic data promises to further bridge the gap between sequence, structure, and function, with profound implications for basic biology and therapeutic development.

The Expanding Market and Impact of Structural Biology

Structural biology is dedicated to determining the three-dimensional (3D) architectures of biological macromolecules, such as proteins, RNA, and DNA, to understand their functions and mechanisms of action at the atomic level [7]. This discipline has become indispensable for fundamental biological research and is a critical driver in applied fields like drug discovery and biotechnology. By visualizing the intricate shapes of molecules, researchers can decipher how they interact, how they are regulated, and how malfunctions lead to disease.

The field is currently experiencing rapid expansion, fueled by converging technological revolutions. High-resolution experimental methods like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have broken new ground in visualizing large complexes, while artificial intelligence (AI) has dramatically accelerated the pace and accuracy of protein structure prediction [7] [8] [9]. This growth is further amplified by the integration of structural data with other biological information through integrative or hybrid modeling (I/HM) approaches, providing a more holistic view of complex cellular machinery [10]. This guide explores the core techniques, emerging trends, and profound impact of these advancements on scientific research and therapeutic development.

Core Methodologies in Structural Biology

A multifaceted toolkit, comprising both experimental and computational techniques, is used to determine biomolecular structures. Each method offers unique advantages and faces specific limitations, making them complementary for tackling different biological questions.

Experimental Structure Determination Techniques

The three primary experimental workhorses of structural biology are X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy.

- X-ray Crystallography: This method has been the gold standard for determining high-resolution structures. It requires purifying the biomolecule and growing a highly ordered crystal. When an intense beam of X-rays hits the crystal, it diffracts, producing a characteristic pattern of spots. This pattern is then used to calculate an electron density map, into which an atomic model is built [10]. A significant bottleneck is crystallization itself, as many proteins, particularly flexible ones, are difficult to crystallize. The quality of a crystal structure is often summarized by its resolution; lower values (e.g., 1.5 Å) indicate higher detail and confidence in the atomic positions [10].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: NMR studies proteins in solution, making it ideal for capturing the intrinsic dynamics and flexibility of biomolecules. The protein is placed in a strong magnetic field and probed with radio waves. The resulting spectra provide information on distances between atoms and local conformation, which are used as restraints to calculate an ensemble of structures that are all consistent with the experimental data [10]. A key strength of NMR is its ability to study conformational changes and binding events in a near-physiological environment. Traditionally limited by the size of the protein, innovations like the novel "top-down" NMRFAM-BPHON approach, which treats spectra as continuous images, are helping to overcome these challenges [11].

- Cryogenic Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM): Cryo-EM has revolutionized structural biology by enabling the determination of high-resolution structures for large and complex macromolecular assemblies that are difficult to crystallize. The sample is rapidly frozen in vitreous ice and then imaged with an electron microscope. Thousands of 2D particle images are collected from the sample and computationally combined to reconstruct a 3D density map [7] [10]. Advances in direct electron detectors and image processing software have pushed cryo-EM resolutions to near-atomic levels, allowing researchers to visualize side chains and ligand-binding sites in massive complexes like ribosomes and viruses [7] [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Experimental Structure Determination Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Resolution | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | X-ray diffraction from crystals | Atomic (0.8 - 3.0 Å) | Very high resolution; detailed atomic information | Requires crystallization; difficult for flexible proteins [10] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Radio wave absorption in magnetic field | Atomic to residue level | Studies dynamics/flexibility in solution; no crystallization needed | Size-limited; spectrum overlap in large proteins [10] |

| Cryo-EM | Electron scattering from frozen-hydrated samples | Near-atomic to sub-nanometer (<1 - ~5 Å) | Visualizes large complexes; no crystallization needed | Small proteins challenging; complex data processing [10] |

| Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) | X-ray scattering in solution | Low (nanometer scale) | Studies overall shape & flexibility in solution; low sample consumption | Low resolution; ensemble-averaged information [12] |

Computational and AI-Driven Modeling

Computational methods have grown from supportive roles to primary tools for structure determination, especially with recent AI breakthroughs.

- Homology Modeling: This technique predicts a protein's 3D structure based on its sequence similarity to one or more proteins with known structures (templates). It relies on the observation that evolutionary related proteins (homologs) share similar structures [7].

- Threading/Fold Recognition: Used when sequence similarity is low, threading identifies structural templates from the fold library that are compatible with the target protein's sequence, even in the absence of clear homology [7] [3].

- AI and Deep Learning Revolution: The field was transformed by DeepMind's AlphaFold2, which achieved accuracy comparable to experimental methods for many protein monomers [9] [4]. Its successor, AlphaFold3, and alternatives like RoseTTAFold All-Atom have expanded capabilities to predict the structures of complexes involving proteins, nucleic acids, ligands, and antibodies [8]. These tools use deep learning on vast datasets of known structures and sequences to predict atomic coordinates directly from amino acid sequences. A key innovation in methods like DeepSCFold is the use of deep learning to predict protein-protein structural complementarity from sequence, leading to more accurate complex modeling even without strong co-evolutionary signals [4].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized integrative workflow that combines multiple data sources for structure determination, a common approach in modern structural biology.

Figure 1. Integrative Workflow for Structure Determination. This workflow shows how experimental data and computational predictions are combined to generate and validate a final atomic model.

Emerging Trends and Techniques (2025 Outlook)

The structural biology landscape is evolving rapidly, with several key trends shaping its future.

- The Rise of Open-Source AI Tools: While AlphaFold3 represents a major step forward, its initial release was not freely available for commercial use, sparking controversy and driving the development of fully open-source alternatives like OpenFold and Boltz-1. 2025 is expected to see increased evaluation and adoption of these community-driven platforms [8].

- Focus on Complexes and Dynamics: Research is shifting from single proteins to biologically relevant complexes and their conformational dynamics. Techniques like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are used to study protein folding, ligand binding, and the effects of mutations over time, providing atomistic insights into molecular behavior [7]. Cryo-EM is particularly powerful for capturing multiple conformational states of a complex [3].

- Integrative/Hybrid Methods (I/HM): I/HM is becoming standard for studying large, heterogeneous systems. It combines data from multiple techniques (e.g., cryo-EM, X-ray, NMR, SAXS, cross-linking) to build models that are consistent with all available information, providing a fuller picture of molecular structure and motion [3] [10].

- Automation and High-Throughput Technologies: Automation in labs, using robotics and liquid handling systems, is accelerating sample preparation and data collection. When combined with AI for data analysis, this enables high-throughput structural genomics efforts [9].

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists essential reagents and materials commonly used in structural biology experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Structural Biology

| Reagent/Material | Function in Structural Biology |

|---|---|

| Purified Protein Sample | The fundamental starting material for all major techniques (Crystallography, Cryo-EM, NMR). Requires high purity and homogeneity. |

| Crystallization Screens | Commercial kits containing diverse chemical conditions to empirically identify optimal parameters for protein crystallization [10]. |

| Grids for Cryo-EM | Specimen supports (e.g., gold or copper grids with a carbon film) onto which the purified sample is applied and vitrified for imaging [10]. |

| Deuterated Solvents & Labels | Essential for NMR spectroscopy; deuterated solvents reduce background signal, while isotopic labeling (15N, 13C) enables residue assignment [10]. |

| Detergents & Lipids | Used to solubilize and stabilize membrane proteins, which are notoriously difficult to work with but represent major drug targets. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Key therapeutic proteins studied using structural biology; the Structural Antibody Database (SabDab) contained over 7,471 structures by 2023 [7]. |

Impact on Drug Discovery and Development

Structural biology is a cornerstone of modern rational drug design, significantly impacting the entire therapeutic development pipeline.

- Target Identification and Validation: Determining the 3D structure of a disease-related protein (e.g., a receptor or enzyme) confirms its druggability and provides a direct starting point for drug design [7].

- Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD): Researchers use atomic structures to design small-molecule inhibitors or biologics that fit precisely into a target's active site or binding pocket. Molecular docking predicts the optimal binding orientation of a ligand, while MD simulations assess the stability of the interaction and estimate binding affinity [7]. This structure-based approach accelerates lead optimization and reduces the time and cost of drug development.

- Understanding Drug Resistance: Structural insights into how mutations in drug target proteins alter their binding sites are critical for designing next-generation therapies that overcome resistance [7]. By analyzing these structural variants, researchers can develop inhibitors that maintain efficacy against mutated targets.

- Antibody and Biologic Therapeutics: The structural biology of monoclonal antibodies is a major research area. By understanding the structural regions responsible for antigen binding, such as complementarity-determining regions (CDRs), researchers can design more effective and stable therapeutic antibodies [7]. Methods like DeepSCFold have shown particular success in improving the prediction of antibody-antigen binding interfaces [4].

- Personalized Medicine: Variability in drug response among patients is often due to genetic differences that affect protein structure. Structural bioinformatics helps understand these variations by examining how coding mutations impact protein-drug interactions, paving the way for treatments tailored to an individual's genetic profile [7].

The diagram below outlines a typical structure-based drug design cycle, highlighting the iterative process between structural analysis and compound design.

Figure 2. Structure-Based Drug Design Cycle. This iterative process uses structural information to design, test, and refine potential drug compounds.

Validation and Best Practices

As structural models, especially computational ones, become more prevalent, robust validation is crucial.

- Experimental Data Validation: A model must fit the experimental data it was derived from. In crystallography, the R-value and R-free measure how well the atomic model agrees with the experimental X-ray data [10]. For cryo-EM, the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) is used to assess resolution and map quality.

- Geometric and Stereochemical Validation: Models are checked for reasonable bond lengths, bond angles, and torsion angles. Tools like MolProbity analyze the distribution of dihedral angles on a Ramachandran plot to identify outliers and steric clashes [13].

- Database Cross-Validation: Resources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) provide validation reports for deposited structures. Efforts like PDBMine aim to reformat PDB data to facilitate structural data mining and validation through machine learning approaches, helping to detect and correct inaccuracies in models [13].

- Reporting Standards: The community has developed strict guidelines for reporting structural studies. For example, updated template tables for biomolecular Small-Angle Scattering (SAS) ensure transparent reporting of sample details, data acquisition parameters, and model quality, enabling readers to assess the validity of the work [12].

Structural biology is in a period of unprecedented expansion, driven by synergies between revolutionary experimental techniques and powerful computational AI tools. The ability to rapidly and accurately determine the structures of proteins and their complexes has transformed our understanding of biological function and has become an indispensable component of therapeutic development. As the field moves forward, the integration of diverse data sources through hybrid methods, the continued improvement of open-source AI tools, and a strong emphasis on validation and standardization will further solidify structural biology's role as a foundational pillar of life science research and biotechnology innovation.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three principal experimental methods for protein structure determination: X-ray Crystallography, Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Within the broader context of protein structure analysis and validation methods research, we detail the fundamental principles, experimental workflows, and technical requirements for each technique. The data presented herein are critical for researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate methodologies for structural biology programs. Quantitative comparisons reveal that X-ray crystallography remains the dominant workhorse for high-throughput structure determination, while Cryo-EM usage has exploded recently due to instrumental advances, and NMR provides unique insights into protein dynamics in solution [14] [15]. Adherence to the detailed protocols and reagent specifications outlined below is essential for generating high-quality, validated structural models.

The determination of three-dimensional protein structures is fundamental to understanding biological mechanisms at the molecular level and for enabling structure-based drug design. The three major experimental techniques—X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, and NMR spectroscopy—each elucidate atomic-level details but operate on different physical principles and have distinct sample requirements and operational domains. According to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) statistics, as of 2023, X-ray crystallography accounted for approximately 66% of released structures, Cryo-EM for about 31.7%, and NMR for nearly 1.9% [14]. The strategic selection of a method depends on the protein's properties, such as size, flexibility, and the ability to crystallize, as well as the desired structural information, whether it be a static high-resolution snapshot or dynamic behavior in a near-native environment.

The following table provides a high-level quantitative comparison of the three core structural biology techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Structural Biology Techniques

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-Electron Microscopy | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Atomic (~1–3 Å) | Near-atomic to Atomic (~3–5 Å, often better) | Atomic (distance constraints) |

| Sample State | Crystalline solid | Vitrified solution | Solution (or solid state) |

| Sample Requirement | High-purity, crystallizable protein (~5 mg at 10 mg/mL) [15] | High-purity protein, ideally >50 kDa [16] | Isotope-labeled protein (< 100 kDa), high concentration (>200 µM) [15] [17] |

| Key Advantage | High throughput; Atomic resolution | No crystallization needed; Handles large complexes | Studies dynamics & interactions in solution |

| Key Limitation | Requires crystallization; Static picture | Small proteins are challenging (<50 kDa) [18] | Low throughput; Size limited |

| Throughput | High | Medium (increasing) | Low |

| PDB Prevalence (2023) | ~66% [14] | ~31.7% [14] | ~1.9% [14] |

X-Ray Crystallography

Fundamental Principles

X-ray crystallography determines structure by measuring the diffraction pattern generated when a beam of X-rays interacts with the electron clouds of atoms arranged in a crystalline lattice. The angles and intensities of the diffracted spots are used to calculate an electron density map, into which an atomic model is built [14] [19] [20]. The fundamental relationship is described by Bragg's Law: ( nλ = 2d sinθ ), where ( λ ) is the X-ray wavelength, ( d ) is the spacing between crystal planes, and ( θ ) is the diffraction angle [20] [21].

Experimental Protocol

The workflow for structure determination via X-ray crystallography involves several critical, sequential steps.

Diagram 1: X-ray Crystallography Workflow

- Protein Production and Purification: The target protein is expressed, typically recombinantly in E. coli or other systems, and purified to high homogeneity (>95% purity). A typical starting point requires at least 5 mg of protein at a concentration of ~10 mg/mL [19] [15] [21].

- Crystallization: This is often the rate-limiting step. The purified protein solution is mixed with a precipitant and slowly concentrated, often via vapor diffusion (hanging or sitting drop methods), to induce the formation of a highly ordered crystal lattice. This process involves extensive screening of conditions (precipitant, buffer, pH, temperature) [19] [21].

- Data Collection: A single crystal is harvested, cryo-cooled to minimize radiation damage, and exposed to an intense X-ray beam (from a laboratory source or synchrotron). The resulting diffraction pattern is recorded on a detector [19].

- Data Processing and Phasing: The diffraction images are processed to determine the crystal's unit cell and space group symmetry. The "phase problem" is solved using methods like molecular replacement (using a similar known structure) or experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD with selenomethionine-labeled protein) to generate an initial electron density map [14] [15].

- Model Building and Refinement: An atomic model is built into the electron density map and iteratively refined to improve the fit to the experimental data while adhering to stereochemical restraints [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for X-ray Crystallography

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Commercial sparse-matrix kits (e.g., from Hampton Research) that pre-dispense a wide range of chemical conditions to empirically identify initial crystal hits [19]. |

| Selenomethionine | An amino acid used to create selenomethionine-labeled proteins for experimental phasing via anomalous dispersion (SAD/MAD) [15]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals like glycerol or ethylene glycol that replace water in the crystal lattice to prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling in liquid nitrogen [19]. |

| Synchrotron Beamtime | Access to a synchrotron radiation source, which provides highly intense and tunable X-ray beams essential for high-resolution data collection, especially for challenging samples [19] [15]. |

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Fundamental Principles

Cryo-EM, specifically single-particle analysis, determines structures by imaging individual protein particles frozen in a thin layer of vitreous ice. Thousands of 2D projection images are collected, computationally sorted by orientation, and averaged to reconstruct a 3D volume [16]. A key concept is the Contrast Transfer Function (CTF), which describes how the electron microscope's lenses modify the image; CTF correction is essential for achieving high resolution [16].

Experimental Protocol

The standard workflow for single-particle Cryo-EM is outlined below.

Diagram 2: Cryo-EM Single-Particle Workflow

- Sample Vitrification: A small aliquot (~3-5 µL) of the purified protein sample is applied to an EM grid, blotted to form a thin film, and rapidly plunged into liquid ethane. This vitrification process traps the particles in a near-native, hydrated state without forming destructive ice crystals [16].

- Data Collection: The vitrified grid is loaded into a transmission electron microscope equipped with a direct electron detector. Images are collected automatically under low-dose conditions (10–20 e⁻/Ų) to minimize beam-induced radiation damage, often as a series of "movie" frames [16].

- Image Pre-processing: The movie frames are aligned to correct for specimen drift and beam-induced motion. The CTF for each micrograph is estimated and corrected to restore accurate structural information [16].

- Particle Picking and 2D Classification: Individual protein particles are automatically identified and extracted from the micrographs. These particles undergo 2D classification to generate averages and remove non-particle images or contaminants.

- 3D Reconstruction and Refinement: An initial 3D model is generated, often from class averages or a known homologous structure. All extracted particle images are then aligned and averaged against this reference to iteratively refine and improve the final 3D reconstruction map.

Special Considerations for Small Proteins

A significant challenge in Cryo-EM is the study of proteins smaller than 50 kDa, as they provide insufficient signal for high-resolution alignment. Strategies to overcome this include:

- Fusion to a Scaffold Protein: The protein of interest is fused to a larger, rigid partner (e.g., a coiled-coil motif like APH2, or a DARPin cage) to increase the effective particle size and mass, facilitating alignment and reconstruction [18].

- Use of Nanobodies or Fabs: Binding of large, rigid antibody fragments can increase particle size and provide additional fiduciary marks for alignment.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cryo-EM

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Direct Electron Detector | A camera that directly records incident electrons with high sensitivity and fast readout, enabling movie-based collection and motion correction. This has been the primary driver of the "resolution revolution" [16]. |

| Holey Carbon Grids | EM grids with a regular array of holes that support the vitreous ice film. Gold grids are often preferred over copper for improved stability and reduced drift [16]. |

| Scaffold Proteins | Well-characterized proteins or protein cages (e.g., DARPins, APH2) used as rigid fusion partners to facilitate the structural analysis of small protein targets [18]. |

| Nanobodies / Fabs | Engineered antibody fragments that bind specifically and rigidly to a target or scaffold protein, increasing the particle's size and complexity for improved image alignment [18]. |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles

NMR spectroscopy probes the magnetic properties of atomic nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹⁵N, ¹³C) in a strong magnetic field. The resonant frequency (chemical shift) of a nucleus is exquisitely sensitive to its local chemical environment. Through-bond and through-space interactions (e.g., NOE) between nuclei are measured to derive distance and dihedral angle restraints, which are used to calculate the 3D structure of the protein in solution [17].

Experimental Protocol

The workflow for protein structure determination by solution-state NMR involves the following stages.

Diagram 3: Protein NMR Spectroscopy Workflow

- Isotope Labeling: The protein must be produced recombinantly in a host (typically E. coli) grown on a minimal medium containing ¹⁵N-ammonium chloride and/or ¹³C-glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources. This uniform isotopic labeling is essential for the multi-dimensional NMR experiments required to resolve and assign signals [15] [17].

- Sample Preparation: The purified, labeled protein is concentrated (>200 µM) in a volume of 250-500 µL of an aqueous buffer, often containing a small percentage of D₂O for instrument locking. The sample must be highly stable for the duration of data collection, which can take several days [15] [17].

- Data Collection: A suite of multi-dimensional NMR experiments is performed. Key experiments include:

- HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence): Serves as a "fingerprint" of the protein, showing one peak for each amide ¹H-¹⁵N pair. It is used to assess sample quality and folding [17].

- Triple-Resonance Experiments (e.g., HNCA, HNCACB): Through-bond correlations that allow for the sequential assignment of backbone atoms [17].

- NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy): Measures through-space interactions between protons, providing crucial distance restraints for 3D structure calculation [17].

- Resonance Assignment: The signals in the NMR spectra are systematically assigned to specific atoms in the protein sequence using the data from triple-resonance experiments.

- Structure Calculation: The assigned NOE-derived distance restraints, along with restraints from J-couplings and chemical shifts, are used in computational simulated annealing protocols to calculate an ensemble of structures that satisfy all experimental data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for NMR Spectroscopy

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Nutrients | ¹⁵N-labeled ammonium salts and ¹³C-labeled glucose are used in bacterial growth media to produce uniformly ¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled recombinant proteins, which are mandatory for modern protein NMR [15] [17]. |

| NMR Tubes | High-quality, thin-walled glass tubes (e.g., 5 mm outer diameter) designed to hold the aqueous protein sample and fit precisely into the NMR spectrometer's probe [17]. |

| Shift Reagents | Paramagnetic ions or other compounds that can be used to resolve overlapping signals or probe molecular interactions. |

| High-Field NMR Spectrometer | Instruments with powerful superconducting magnets (≥600 MHz for ¹H frequency) equipped with cryogenically cooled probes to maximize sensitivity [15]. |

X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, and NMR spectroscopy form a complementary toolkit for protein structure analysis. X-ray crystallography provides the majority of high-resolution structures but is gated by the crystallization bottleneck. Cryo-EM has emerged as a powerful competitor, especially for large complexes that are difficult to crystallize, with its capabilities now extending to smaller proteins via innovative scaffolding strategies. NMR remains unique in its ability to probe protein dynamics and interactions directly in solution, despite its lower throughput and size limitations. The ongoing integration of structural data from these methods with computational predictions from tools like AlphaFold promises to further accelerate the pace of discovery in structural biology and rational drug design. Validation of models generated by any method, through careful examination of the experimental data and stereochemistry, remains a cornerstone of rigorous research.

The quest to determine the three-dimensional structure of proteins from their amino acid sequence represents one of the most significant challenges in modern biology. For decades, scientists relied on experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize protein structures [22] [23]. While these methods provide invaluable insights, they are often time-consuming, expensive, and technically demanding, creating a substantial gap between the number of known protein sequences and experimentally determined structures [22]. This limitation propelled the development of computational methods, initiating a revolutionary transition from traditional homology modeling to the current era of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven prediction.

This evolution has fundamentally transformed structural biology, enabling researchers to predict protein structures with atomic-level accuracy rivaling experimental methods [24]. The groundbreaking success of AlphaFold at the 14th Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) competition and its subsequent recognition with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry marked a pivotal moment in this revolution [25] [22]. This whitepaper examines the core computational methodologies, from their inception to the current state-of-the-art, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical guide to navigating this rapidly advancing field.

The Era of Traditional Computational Methods

Before the advent of AI, computational protein structure prediction primarily relied on two fundamental approaches: Template-Based Modeling (TBM) and Template-Free Modeling (TFM). These methods established the foundational principles upon which modern AI systems were built.

Template-Based Modeling (TBM)

TBM operates on the principle that evolutionarily related proteins share similar structures. When a protein with a known structure (a "template") exists for a query sequence, comparative modeling can be employed. The specific workflow involves:

- Step 1: Template Identification. A homologous protein structure serving as a template for the target protein is identified. A sequence identity of at least 30% between the target and template is typically required for reliable modeling [23].

- Step 2: Sequence Alignment. A sequence alignment is created between the target sequence and the template sequence, establishing the correspondence between amino acid positions [23].

- Step 3: Model Building. Amino acids from the target sequence are mapped onto the spatial positions of their counterparts in the template structure. This process is facilitated by homology modeling software such as MODELLER or SwissPDBViewer [23].

- Step 4: Quality Assessment and Iteration. The generated model undergoes quality evaluation. Based on the assessment results, the sequence alignment may be refined, and the model rebuilding process repeated until satisfactory quality is achieved [23].

- Step 5: Atomic-Level Refinement. The 3D structure is refined at the atomic level to produce the final predicted model [23].

TBM can be subdivided into comparative modeling (for targets with clearly homologous templates) and threading (or fold recognition), designed for cases where sequence similarity is minimal but the protein may share a similar fold with a known structure [23].

Template-Free Modeling (TFM)

Also referred to as ab initio or free modeling, TFM predicts protein structure directly from the amino acid sequence without relying on a global template. The workflow generally follows these steps:

- Step 1: Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA). MSAs are performed between the target protein and its homologous sequences to gather information on amino acid conservation and co-evolutionary patterns [23].

- Step 2: Local Structure Prediction. The target sequence and MSAs are used to predict local structural frameworks, including torsion angles and secondary structures [23].

- Step 3: Fragment Assembly and Contact Prediction. Backbone fragments are extracted from proteins with similar local structures. Additionally, residue pairs that may be in spatial contact are predicted based on co-evolutionary signals in the MSAs [23].

- Step 4: 3D Model Construction. Three-dimensional models are built by integrating predictions of local structure and residue contacts using methods such as gradient-based optimization, distance geometry, and fragment assembly [23].

- Step 5: Energy-Based Optimization. The model is refined using energy functions to identify low-energy conformational states, navigating the vast search space of possible protein folds [23].

Table 1: Key Traditional Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method Name | Type | Key Features | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Modeling | TBM | Relies on high sequence similarity to a known template; fast and accurate when templates exist. | MODELLER, Swiss-Model [23] |

| Threading | TBM | Matches sequence to structural folds even with low sequence identity; useful for remote homology detection. | HHsearch, HMM-based methods [23] [26] |

| Fragment Assembly | TFM | Assembles 3D structures from short protein fragments; effective for novel folds without templates. | Rosetta (early versions) [23] |

| Contact-Assisted Prediction | TFM | Uses predicted residue-residue contacts as restraints for 3D modeling; improved accuracy for ab initio prediction. | TrRosetta [23] |

The AI Revolution: Deep Learning Enters the Scene

The application of deep learning to protein structure prediction represents a paradigm shift, moving from reliance on physical principles and explicit templates to data-driven inference learned from vast repositories of known structures.

AlphaFold2: A Quantum Leap in Accuracy

The release of AlphaFold2 (AF2) by Google DeepMind in 2020 marked a watershed moment. Its architecture and performance represented a monumental advance over all previous methods.

Core Architectural Components: AF2's architecture consists of two key components working in an iterative manner [22]:

- Evoformer: A neural network module that processes the input multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and pairwise representations. It uses attention mechanisms to reason about the relationships between amino acids, capturing both evolutionary and potential spatial constraints [22].

- Structure Module: This module takes the output from the Evoformer and generates the atomic coordinates of the protein backbone and side chains. It operates in 3D space, progressively refining the predicted structure [22].

AF2's performance at CASP14 was unprecedented, achieving a median backbone accuracy (RMSD) of 0.8 Å, compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method [22]. Its success was largely attributed to its ability to leverage deep learning to interpret MSAs and directly predict atomic coordinates, effectively learning the "language" of protein folding from data.

Expanding the Horizon: Predicting Complexes and Interactions

Following AF2's success, the field rapidly advanced to address the greater challenge of predicting the structures of protein complexes and their interactions with other biomolecules.

AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3: An extension of AF2, AlphaFold-Multimer, was specifically tailored for predicting multi-chain protein complexes [4] [24]. This was a significant step forward, though its accuracy for complexes remained lower than AF2's for single chains [4]. The recently released AlphaFold3 (AF3) represents another major leap. It employs a refined diffusion-based architecture capable of predicting the structures and interactions of a wide range of biomolecules—including proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and metals—with unparalleled precision [22].

DeepSCFold: Enhancing Complex Prediction with Structural Complementarity: DeepSCFold is a state-of-the-art pipeline that addresses a key limitation in complex prediction: the frequent absence of clear co-evolutionary signals between interacting chains, as seen in antibody-antigen or virus-host systems [4]. Instead of relying solely on sequence-level co-evolution, DeepSCFold uses deep learning to predict protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) and interaction probability (pIA-score) directly from sequence information [4]. These scores are used to construct high-quality paired MSAs, providing reliable inter-chain interaction signals. Benchmark results are impressive, showing an 11.6% improvement in TM-score over AlphaFold-Multimer and a 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 on CASP15 multimer targets. For challenging antibody-antigen complexes, it boosted the success rate for interface prediction by 24.7% and 12.4% over the same respective tools [4].

RoseTTAFold All-Atom: Another significant advancement is RoseTTAFold All-Atom, a three-track neural network that simultaneously reasons about protein sequence, distance relationships, and 3D coordinates [24]. This next-generation tool can model full biological assemblies containing proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, metals, and post-translational modifications [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Advanced AI Prediction Tools

| Tool | Primary Application | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Single-chain protein structure | RMSD (Backbone) | 0.8 Å (CASP14 median) [22] | 2020 |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Protein complexes (multimers) | TM-score (CASP15) | Baseline for comparison [4] | 2022 |

| AlphaFold3 | Biomolecular complexes (proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands) | Interface Prediction Success Rate (on SAbDab) | Baseline + 12.4% improvement by DeepSCFold [4] | 2024 |

| DeepSCFold | Protein complexes, especially lacking co-evolution | TM-score (vs. AF-Multimer) | +11.6% improvement [4] | 2025 |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Biomolecular assemblies with ligands/metals | Docking Power | High accuracy in modeling diverse molecular interactions [24] | 2024 |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments and workflows cited in contemporary research, enabling researchers to understand and implement these advanced techniques.

DeepSCFold Protocol for Protein Complex Structure Modeling

The DeepSCFold protocol is designed for high-accuracy prediction of protein complex structures through a specialized paired MSA construction process [4].

- Input and Monomeric MSA Generation: The process begins with the input protein complex sequences. DeepSCFold first generates monomeric multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) for each individual chain from multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, UniRef90, BFD, MGnify, ColabFold DB, etc.) [4].

- Structural Similarity Scoring (pSS-score): A deep learning model predicts the pSS-score, which quantifies the structural similarity between the input sequence and its homologs in the monomeric MSAs. This score complements traditional sequence similarity, enhancing the ranking and selection of monomeric MSA sequences [4].

- Interaction Probability Scoring (pIA-score): A second deep learning model predicts the pIA-score, estimating the interaction probability for each potential pair of sequence homologs derived from the distinct subunit MSAs [4].

- Biological Information Integration: Multi-source biological information, including species annotations, UniProt accession numbers, and experimentally determined complexes from the PDB, is integrated to construct additional paired MSAs with enhanced biological relevance [4].

- Paired MSA Construction and Structure Prediction: The pIA-scores and biological data are used to systematically concatenate monomeric homologs, constructing the final, high-quality paired MSAs. These are then used by AlphaFold-Multimer to perform complex structure predictions [4].

- Model Selection and Refinement: The top-1 model is selected using an in-house complex model quality assessment method (DeepUMQA-X). This model is then used as an input template for a final iteration of AlphaFold-Multimer to generate the ultimate output structure [4].

Protocol for Comparative Modeling of Short Peptides

A 2025 study provided a detailed protocol for comparing the efficacy of different algorithms in predicting the structure of short, unstable peptides, such as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) [27].

- Peptide Selection and Property Calculation: A set of peptides is randomly selected. Their charge and isoelectric point (pI) are determined using tools like Prot-pi. Physicochemical properties, including aromaticity, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), and instability index, are calculated using ExPASy's ProtParam tool [27].

- Disorder and Secondary Structure Prediction: The secondary structure, solvent accessibility, and disordered regions of the peptides are predicted using the RaptorX server, which employs a deep learning model (DeepCNF) [27].

- Structure Prediction with Multiple Algorithms: Each peptide's structure is predicted using four distinct algorithms: AlphaFold, PEP-FOLD3, Threading, and Homology Modeling (using Modeller) [27].

- Initial Structural Validation: The predicted structures from each algorithm are initially analyzed using a Ramachandran plot and the validation tool VADAR to assess stereochemical quality [27].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: To further validate structural stability, MD simulations are performed on all structures generated by the four algorithms. Each simulation is typically run for a period of 100 ns [27].

- Stability and Algorithmic Suitability Analysis: The MD simulation trajectories are analyzed to determine the stability (e.g., via RMSD, RMSF) of the peptide structures predicted by each algorithm. The findings are correlated with the peptides' physicochemical properties to determine which algorithm is most suitable for which type of peptide [27]. The study found that AlphaFold and Threading complement each other for more hydrophobic peptides, while PEP-FOLD and Homology Modeling are better for more hydrophilic peptides [27].

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Evolution of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

This diagram visualizes the key milestones and the evolutionary trajectory of computational protein structure prediction methods, from early template-based approaches to the current AI-driven revolution.

High-Level Architecture of AlphaFold2

This diagram illustrates the core iterative architecture of the AlphaFold2 system, highlighting the flow of information between its two primary neural network components.

This section details key databases, software tools, and computational resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers working in the field of computational protein structure prediction.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Protein Analysis

| Category | Item/Resource | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and complex assemblies; serves as the gold standard for validation and training [22]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database (AlphaFold DB) | Open-access database providing over 200 million AI-predicted protein structure models; accelerates research by providing reliable models for uncharacterized proteins [2]. | |

| UniProt | Comprehensive resource for protein sequence and functional information; used for generating multiple sequence alignments and gathering sequence data [4]. | |

| Software & Tools | AlphaFold2/3 | Deep learning system for predicting protein structures (AF2) and biomolecular interactions (AF3) with high accuracy. Available via code or web server [2] [22]. |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Deep learning-based three-track neural network for modeling complexes of proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, and metals [24]. | |

| DeepSCFold | A pipeline that improves protein complex structure modeling by using sequence-derived structural complementarity, especially useful for complexes lacking co-evolution [4]. | |

| MODELLER | A computational tool for comparative or homology modeling of protein three-dimensional structures; a gold-standard for template-based modeling [27] [23]. | |

| PEP-FOLD3 | A de novo approach for predicting peptide structures from amino acid sequences, useful for modeling short peptides [27]. | |

| Analysis & Validation | VADAR | A comprehensive web server for the quantitative assessment of protein structure quality including volume, area, dihedral angle, and rotamer analysis [27]. |

| Foldseek | A fast and sensitive method for comparing protein structures and large-scale clustering of predicted models, enabling efficient homology detection [26]. | |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation | Computational method for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time; used to assess the stability and dynamics of predicted models [27]. |

The computational revolution in protein structure prediction, from its origins in homology modeling to the current dominance of AI, has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of structural biology and drug discovery. AlphaFold2 and its successors have provided scientists with a powerful tool that delivers predictions of remarkable accuracy, dramatically expanding the structural coverage of the protein universe. As evidenced by the latest research, the field continues to advance rapidly, with innovations like DeepSCFold and RoseTTAFold All-Atom pushing the boundaries to tackle more complex challenges, such as predicting transient protein interactions and modeling full biomolecular assemblies.

This progress, however, does not render experimental methods obsolete. Instead, it creates a powerful synergy where computational predictions can guide and prioritize experimental work, as demonstrated by tools like ESMBind for predicting metal-binding sites [28]. The future of protein structure analysis lies in the continued integration of computational and experimental approaches, leveraging the strengths of each to achieve a deeper, dynamic understanding of protein function and interaction. This integrated approach, supported by the extensive toolkit of databases and software now available to researchers, promises to accelerate discoveries across biology and medicine, from deciphering disease mechanisms to designing novel therapeutics.

Protein structure analysis is a cornerstone of modern biological science and drug discovery, providing critical insights into molecular functions and mechanisms. The field is underpinned by two pivotal resources: the Protein Data Bank (PDB), the global archive for experimentally determined structures, and the AlphaFold Database, a repository of highly accurate AI-predicted protein structures. The advent of deep learning systems like AlphaFold has revolutionized structural bioinformatics by providing atomic-level accuracy predictions for nearly all known proteins. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core databases, their interoperability, and their application in protein structure validation and analysis. Framed within a broader thesis on protein structure analysis, this review equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage these resources for advancing scientific discovery.

The PDB and AlphaFold Database represent complementary pillars of structural biology infrastructure, each with distinct origins, data acquisition methodologies, and use cases.

The Protein Data Bank (PDB) established in 1971, serves as the primary global archive for experimentally determined biomolecular structures. Managed by the worldwide PDB (wwPDB) consortium, it contains over 200,000 structures elucidated through experimental methods including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [29]. The PDB provides curated, validated structural data essential for understanding biological mechanisms and facilitating drug development.

The AlphaFold Database, launched in 2021 through a partnership between Google DeepMind and EMBL's European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), provides open access to over 200 million protein structure predictions generated by the AlphaFold AI system [2]. This comprehensive resource covers nearly the entire UniProt knowledgebase, representing a monumental expansion of accessible structural information for the scientific community.

Table 1: Core Database Specifications and Capabilities

| Feature | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | AlphaFold Database |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Content | Experimentally determined structures (X-ray, NMR, Cryo-EM) | AI-predicted protein structures |

| Entry Count | >200,000 curated experimental structures | >200 million predicted structures [2] |

| Data Sources | Experimental deposition community | AlphaFold AI predictions on UniProt sequences |

| Structure Coverage | Limited to experimentally solved structures | Broad coverage of catalogued proteins |

| Confidence Metrics | Experimental resolution, validation reports | pLDDT (per-residue confidence score) [30] |

| Access Methods | RCSB portal, API downloads, FTP services [31] | Web interface, bulk downloads, API access [2] |

| Licensing | Public domain with attribution requirements | CC-BY-4.0 [2] |

| Update Frequency | Continuous with new experimental determinations | Periodic updates with new sequences and model versions |

The transformative impact of these resources is evidenced by their widespread adoption. The AlphaFold Database has garnered over two million users from 190 countries and has been referenced in more than 30,000 scientific publications worldwide [32]. Independent evaluations indicate that approximately 35% of AlphaFold predictions are considered highly accurate, with an additional 45% deemed broadly usable for many research applications [32].

Technical Architectures and Methodologies

AlphaFold Neural Network Architecture

AlphaFold represents a fundamental advancement in protein structure prediction through its novel neural network architecture. The system employs an end-to-end deep learning approach that directly predicts the 3D coordinates of all heavy atoms from amino acid sequences and evolutionary information [30].

The architecture comprises two primary components: the Evoformer and the Structure Module. The Evoformer operates as the core computational block that processes input multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) through a series of attention mechanisms to generate refined representations of evolutionary relationships. This module produces two key outputs: a processed MSA representation and a pair representation that encodes relationships between residues [30].

The Structure Module then translates these representations into explicit 3D atomic coordinates through a series of rigid body transformations. A critical innovation is the iterative refinement process known as "recycling," where outputs are recursively fed back into the network to progressively enhance accuracy. The network employs a specialized loss function that emphasizes both positional and orientational correctness, enabling the prediction of geometrically precise atomic structures [30].

PDB Data Processing and Curation Pipeline

The PDB maintains rigorous data processing protocols to ensure the quality and reliability of its structural archive. The deposition pipeline begins with data extraction and format conversion using specialized tools such as pdb_extract and SF-Tool for structure factor conversion [33]. Following initial processing, structures undergo comprehensive validation against experimental data and geometric principles.

The validation process employs standardized metrics developed through wwPDB Validation Task Forces, assessing factors including stereochemical quality, fit to experimental data, and overall structure geometry [33]. Validation reports provide depositors and users with critical quality assessments, highlighting potential concerns and comparing structures against others in the archive. This meticulous curation process ensures the scientific integrity of the PDB as a reference resource for the research community.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Structure Prediction Using AlphaFold

For researchers requiring predictions beyond the pre-computed structures in the AlphaFold Database, the following protocol outlines the process for generating custom structure predictions:

Sequence Preparation: Obtain the target amino acid sequence in FASTA format. Ensure sequence integrity and correct residue numbering.

Multiple Sequence Alignment Generation: Search sequence databases (UniRef90, UniProt, MGnify) using tools like JackHMMER or HHblits to construct a diverse multiple sequence alignment [30]. The depth and diversity of the MSA significantly impact prediction accuracy.

Template Identification (Optional): For structures with known homologs, identify potential templates from the PDB to provide additional structural constraints.

Model Inference: Input the MSA and templates into the AlphaFold neural network. The model processes inputs through the Evoformer and Structure Module to generate atomic coordinates.

Iterative Refinement: Enable the recycling mechanism (typically 3-6 iterations) to allow progressive refinement of the predicted structure.

Model Selection and Validation: Select the highest-ranking model based on predicted confidence metrics (pLDDT). Evaluate global and local quality measures before downstream application.

Complex Structure Modeling with DeepSCFold

For modeling protein complexes, advanced protocols like DeepSCFold leverage structural complementarity to enhance prediction accuracy:

Monomeric MSA Construction: Generate individual MSAs for each protein chain using multiple sequence databases (UniRef30, BFD, MGnify) [4].

Structural Similarity Assessment: Calculate predicted protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) between query sequences and their homologs to enhance MSA ranking and selection.

Interaction Probability Prediction: Estimate interaction probabilities (pIA-score) between sequence homologs from different subunit MSAs using deep learning models.

Paired MSA Construction: Systematically concatenate monomeric homologs using interaction probabilities, species annotations, and known complex information from the PDB.

Complex Structure Prediction: Input paired MSAs into AlphaFold-Multimer to generate quaternary structure models.

Model Quality Assessment: Select top-ranking models using specialized assessment methods like DeepUMQA-X, then use selected models as templates for final refinement iterations [4].

Benchmark results demonstrate that DeepSCFold achieves an 11.6% improvement in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and a 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 on CASP15 multimer targets [4].

Experimental Structure Validation Using NMR

For experimental validation of protein structures, a novel "top-down" NMR approach provides robust validation without requiring complete resonance assignments:

Spectra Acquisition: Collect multidimensional NMR spectra, prioritizing 13C-detected magic angle spinning solid-state NMR for membrane proteins or large complexes.

Candidate Structure Preparation: Generate structural models through prediction or experimental determination for validation.

Spectra Simulation: Use NMRFAM-BPHON to simulate NMR spectra from candidate structures using physics-based polarization transfer models to predict cross-peak intensities from internuclear distances [11].

Image Analysis Comparison: Treat experimental and simulated spectra as continuous images. Calculate normalized cross-correlation between images to quantify agreement.

Fitness Scoring: Generate fitness scores between 0-1, with higher values indicating better agreement between experimental data and candidate structures.

Model Discrimination: Use fitness scores to rank candidate structures and identify optimal models that best explain experimental data.

This approach is implemented in the user-friendly NMRFAM-BPHON graphical interface for ChimeraX, making advanced NMR validation accessible without extensive manual analysis [11].

Data Access and Interoperability

Programmatic Access and File Retrieval

Both databases provide comprehensive programmatic access interfaces to support automated data retrieval and integration into research pipelines.

The PDB offers multiple access methods through its file download services [31]:

- Direct File Access: Structures can be retrieved using concise URLs (e.g.,

https://files.rcsb.org/download/4hhb.ciffor mmCIF format orhttps://files.rcsb.org/download/4hhb.pdbfor legacy PDB format). - Bulk Download: Scripted downloads using wget or custom scripts can access structured directories organized by PID middle characters.

- Rsync Capabilities: Efficient synchronization of entire archive subsets using rsync protocols.

- Format Variants: Data available in mmCIF, PDBML/XML, BinaryCIF, and legacy PDB formats, compressed or uncompressed.

The AlphaFold Database provides similar access patterns for its predicted structures, with specialized endpoints for proteome-scale downloads and individual protein queries [2]. The database integrates with UniProt identifiers, enabling seamless cross-referencing between sequence and structure information.

Table 2: Database Access Endpoints and File Formats

| Access Method | PDB Examples | AlphaFold Database Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Single Structure | https://files.rcsb.org/download/4hhb.cif.gz |

Proteome-specific downloads |

| Bulk Download | rsync://rsync.rcsb.org/pub/pdb/data/structures/divided/pdb/ |

Full database downloads |

| Biological Assemblies | https://files.rcsb.org/download/5a9z-assembly1.cif |

N/A |

| Legacy Format | https://files.rcsb.org/download/4hhb.pdb |

N/A |

| Header-Only | https://files.rcsb.org/header/4hhb.cif |

Annotation-specific endpoints |

| Validation Data | https://files.rcsb.org/validation_reports/ |

pLDDT confidence scores |

Visualization and Analysis Tools

Both platforms provide integrated visualization capabilities alongside extensive data access. The RCSB PDB website offers structure summary pages with molecular visualization using Mol* and analysis tools for exploring relationships within the archive [29]. The AlphaFold Database includes interactive 3D visualization with confidence metrics mapping and, as of November 2025, new functionality for custom sequence annotation visualization [2] [34].

Table 3: Core Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Repository of 200M+ predicted structures | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [2] |

| RCSB PDB | Database | Archive of experimental structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ [29] |

| DeepSCFold | Software Pipeline | Protein complex structure modeling | Academic use [4] |

| NMRFAM-BPHON | Validation Tool | NMR spectra-structure fitness scoring | ChimeraX plugin [11] |

| pdb_extract | Data Tool | Extracts data from structure determination programs | wwPDB [33] |

| SF-Tool | Conversion Tool | Converts structure factor file formats | wwPDB [33] |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | Prediction Software | Alternative AI structure prediction tool | Non-commercial license [8] |

| OpenFold | Prediction Software | Open-source AlphaFold alternative | MIT License [8] |

Future Directions and Research Challenges

The field of protein structure prediction and validation continues to evolve rapidly. Recent developments include AlphaFold3's expansion to model protein complexes with DNA, RNA, and ligands, though its initial release with restricted access sparked debate regarding openness versus commercialization [32] [8]. The research community has responded with open-source initiatives such as OpenFold and Boltz-1 aiming to provide fully accessible alternatives [8].