Protein Structure Determination by X-Ray Crystallography: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Practice

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the protein structure determination pipeline using X-ray crystallography, a cornerstone technique in structural biology.

Protein Structure Determination by X-Ray Crystallography: A Comprehensive Guide from Principles to Practice

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the protein structure determination pipeline using X-ray crystallography, a cornerstone technique in structural biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of diffraction, a step-by-step methodological walkthrough from crystallization to model refinement, and practical troubleshooting for common challenges. It further details critical structure validation protocols and offers a comparative analysis with other leading structural techniques like Cryo-EM and NMR, empowering readers to effectively apply and interpret crystallographic data in biomedical research and drug discovery.

The Fundamentals of Protein X-ray Crystallography: From Atoms to 3D Models

X-ray crystallography stands as a cornerstone technique for determining the three-dimensional atomic structure of matter, with its application to biological macromolecules like proteins revolutionizing our understanding of biology and empowering drug discovery efforts [1]. At the heart of this powerful method lies Bragg's Law, a fundamental physical principle that describes the condition for diffraction when X-rays interact with a crystalline lattice [2]. This law provides the essential link between the experimentally measured diffraction pattern and the atomic-scale structure of the crystal. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of Bragg's Law is not merely academic; it is critical for planning and interpreting crystallographic experiments, from obtaining the initial protein crystals to solving and validating a structural model [3]. This guide details the core physics, its practical application in protein structure determination, and the advanced methodologies that leverage this foundational principle.

Fundamental Physics of Bragg's Law

Historical Foundation and Theoretical Background

The phenomenon of X-ray diffraction was first demonstrated by Max von Laue in 1912, proving the wave-like nature of X-rays and the periodic arrangement of atoms in crystals [4]. Shortly thereafter, in 1913, Sir William Henry Bragg and his son, Sir William Lawrence Bragg, proposed a simpler explanation for the observed diffraction patterns [2] [5]. They modeled a crystal as a set of discrete, parallel planes of atoms separated by a constant distance, d. Lawrence Bragg proposed that the intense peaks of reflected radiation (now known as Bragg peaks) occurred when X-rays scattering off these different planes interfered constructively [2]. This seminal insight, for which the Braggs were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915, provided a powerful new tool for determining crystal structures and remains the most intuitive way to understand X-ray diffraction [2] [6].

Bragg's Law is a special case of the more general Laue diffraction and applies not only to X-rays but to all types of matter waves, including neutron and electron waves, provided the scattering object is a crystal with a large number of atoms [2].

The Bragg Condition and Mathematical Formulation

Bragg diffraction occurs when radiation, with a wavelength λ comparable to atomic spacings, is scattered in a specular (mirror-like) fashion by atomic planes and undergoes constructive interference [2]. The condition for this constructive interference is given by the well-known Bragg Equation:

Where:

nis a positive integer (1, 2, 3...) representing the order of the diffraction.λis the wavelength of the incident X-ray beam.dis the interplanar spacing between the atomic layers in the crystal.θis the glancing angle (or angle of incidence), measured between the incident ray and the scattering plane, not the surface normal [2].

This equation states that constructive interference, and hence an intense diffraction peak, will only be observed when the path difference between waves reflected from adjacent crystal planes is equal to an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength [5] [6].

Figure 1: A schematic diagram illustrating the geometry of Bragg's Law. The path difference between waves reflecting from adjacent planes is AB + BC = 2d sinθ.

Derivation of Bragg's Law

The derivation of Bragg's Law stems from calculating the path difference between two parallel X-ray waves scattering off two adjacent atomic planes [2] [6].

- Consider two parallel X-ray waves, 1 and 2, incident on two crystal planes separated by a distance

dat a glancing angleθ. - Wave 2 travels an extra distance

ABto reach the second plane and an extra distanceBCafter scattering. The total path difference isAB + BC. - From geometry,

AB = BC = d sinθ. Therefore, the total path difference is2d sinθ. - For constructive interference to occur, this path difference must be an integer multiple of the wavelength

λ. - This leads directly to the Bragg equation:

nλ = 2d sinθ[2] [6].

It is crucial to note that while the phenomenon is described as "reflection," it is fundamentally a result of constructive interference from scattered waves. If this condition is not met, the waves will arrive out of phase and undergo destructive interference, resulting in no detectable signal [3].

Bragg's Law in Protein X-ray Crystallography

Protein X-ray crystallography is a multi-step process for determining the atomic structure of proteins, and Bragg's Law underpins the critical data collection and interpretation phases [3] [1].

The Central Role of Diffraction in Structure Determination

In protein crystallography, the protein is first purified and induced to form a highly ordered crystal [1]. When a crystal is placed in an intense X-ray beam, typically generated by a synchrotron radiation source, the electrons within the crystal scatter the X-rays [3]. Each atom acts as a source of scattered waves, and the regular, repeating arrangement of atoms in the crystal causes these scattered waves to interact and produce a diffraction pattern composed of discrete spots on a detector [3]. The position and intensity of these spots are the primary experimental data.

According to Bragg's model, each spot in the diffraction pattern corresponds to a specific set of atomic lattice planes within the crystal, defined by their Miller indices (hkl) [3]. The crystal is rotated in the X-ray beam (using a goniometer) to bring different lattice planes into their Bragg condition, thereby collecting a complete set of diffraction intensities [3]. Modern synchrotrons, with their high-intensity beams and advanced robotic sample handling, can collect an entire dataset in less than a minute [3].

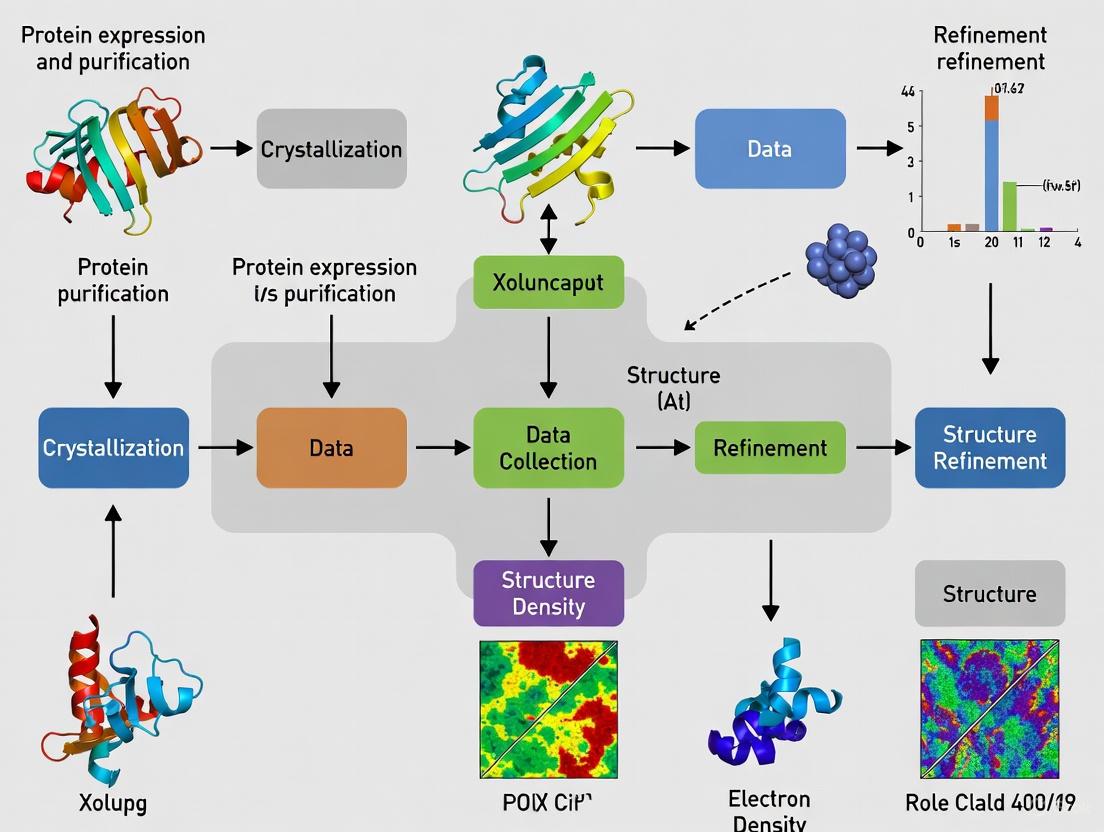

Figure 2: A high-level workflow of protein structure determination by X-ray crystallography, highlighting where Bragg's Law is applied.

From Diffraction Spots to Electron Density

The final goal is to compute an electron density map into which the atomic model of the protein is built. The connection between the observed diffraction pattern and this map is made via a mathematical operation called a Fourier transform [3]. The electron density ρ(xyz) is calculated using the equation:

ρ(xyz) = 1/V Σ_h Σ_k Σ_l |F(hkl)| exp[-2πi(hx + ky + lz) + iϕ(hkl)]

Where:

Vis the volume of the unit cell.|F(hkl)|is the structure factor amplitude, derived from the measured intensity of the diffraction spot with Miller indiceshkl.ϕ(hkl)is the phase of the structure factor [3].

While the intensity of a diffraction spot (which gives |F(hkl)|) can be measured directly, the phase information ϕ(hkl) is lost during data collection. This is known as the "phase problem" in crystallography. Determining the phases requires additional experimental methods, such as heavy atom replacement (e.g., MIR or MAD), or molecular replacement if a related structure is known [3]. Bragg's Law is essential in the initial processing of diffraction images to correctly index and assign Miller indices to each spot, which is the first step in determining the unit cell parameters and preparing the data for phasing [3].

Advanced Quantitative Analysis and Methodologies

Quantitative X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Methods

Beyond biological crystallography, Bragg's Law is the foundation for quantitative phase analysis in materials science and geology. Several sophisticated software-based methods have been developed, each with specific strengths and limitations [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Quantitative X-ray Diffraction Mineral Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Typical Software | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) | Uses the intensity of a single peak and a known reference ratio to quantify phase abundance [7]. | JADE | A handy and simple approach [7]. | Lower analytical accuracy, especially in complex mixtures [7]. |

| Rietveld Refinement | A whole-pattern fitting method that refines a calculated pattern (based on crystal structure models) to match the observed pattern [7]. | HighScore, TOPAS, GSAS, BGMN, Maud | High accuracy for non-clay samples; can refine structural parameters (atom positions, cell parameters) [7]. | Struggles with phases with disordered or unknown crystal structures [7]. |

| Full Pattern Summation (FPS) | The observed pattern is modeled as the sum of reference patterns from pure phases [7]. | FULLPAT, ROCKJOCK | Wide applicability, considered most appropriate for sediments and clay-containing samples [7]. | Requires a comprehensive library of reference patterns [7]. |

Resolution and Data Quality in Protein Crystallography

In protein crystallography, the quality of the final atomic model is directly governed by the resolution of the diffraction data [3]. Resolution refers to the finest detail discernible in the electron density map and is determined by the highest angle diffraction spots collected. It is inversely related to the smallest d-spacing measured, as per Bragg's Law. The resolution dictates what structural features can be reliably interpreted.

Table 2: Interpretation of Resolution Ranges in Protein X-ray Crystallography

| Resolution Range | Structural Features Discernible |

|---|---|

| Low Resolution (> 5 Å) | The overall shape and envelope of the protein molecule; α-helices appear as rods. Individual amino acids cannot be distinguished [3]. |

| Medium Resolution (3.5 - 2.5 Å) | The protein backbone can be traced; side chains become distinguishable, allowing the sequence to be built into the density. Solvent (water) molecules can start to be identified [3]. |

| High/Atomic Resolution (2.4 Å or better) | Individual atoms become resolved; fine structural details are clear. The model-building process is more straightforward, and a large number of solvent molecules can be identified and modeled [3]. |

Modern Advances: Pushing the Limits of Bragg's Law

The field of X-ray diffraction continues to evolve, driven by advancements in source technology and data processing. The recent development of extremely brilliant synchrotron sources, such as the ESRF's Extremely Brilliant Source (EBS), has increased the available coherent flux by a factor of 100 [4]. This brilliance enables new techniques:

- Nanoscale Mapping: Advances in X-ray focusing optics now allow for diffraction mapping with a spatial resolution of 50–100 nm, enabling the quantification and localization of elastic strains and defects in crystalline materials, which is crucial for understanding material properties [4].

- Coherent Diffraction Imaging (CDI): This lensless technique can achieve a spatial resolution of 5–10 nm. It uses the coherent diffraction pattern and phase retrieval algorithms to reconstruct an image of the sample, bypassing the need for crystals large enough for traditional crystallography [4].

- Serial Crystallography: This method, often used with X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), involves collecting diffraction data from a stream of tiny, randomly oriented microcrystals. It has opened new avenues for studying proteins that are difficult to crystallize into large single crystals [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful X-ray crystallography relies on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and instruments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Protein X-ray Crystallography

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Purified Protein Sample | The target macromolecule, typically produced via recombinant expression and purified to homogeneity, is the fundamental starting material [1]. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Commercial kits containing a wide array of chemical conditions (precipitants, buffers, salts, additives) to empirically identify initial conditions for protein crystal growth [3]. |

| Synchrotron Beamline | A large-scale facility that generates high-intensity, focused X-ray beams necessary for collecting high-quality diffraction data from protein crystals [3]. |

| Cryo-Protectant | A chemical (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) used to soak crystals before flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. This prevents ice formation and protects the crystal from radiation damage during data collection [3]. |

| Heavy Atom Compounds | Reagents containing atoms with high atomic numbers (e.g., mercury, platinum, selenium) used for experimental phasing. They are soaked into crystals or incorporated via expression (e.g., selenomethionine) to solve the "phase problem" [3]. |

| X-ray Detector | A two-dimensional hybrid pixel detector that captures the diffraction pattern. Modern detectors offer high dynamic range, fast readout speeds, and low noise, which are critical for efficient data collection [4]. |

Proteins are the fundamental workhorses of biology, orchestrating a vast array of cellular processes, from catalyzing chemical reactions and supporting immune responses to facilitating cellular communication [1]. The specific function of a protein is an direct consequence of its unique three-dimensional (3D) structure. The precise arrangement of atoms within a protein dictates its ability to bind other molecules, form complexes, and perform its biological role. Understanding protein structure is therefore paramount for deciphering the molecular mechanisms of life and disease. In drug discovery, this understanding empowers researchers to design targeted therapies that precisely modulate protein function, offering high efficacy and reduced side effects. This whitepaper explores how elucidating 3D protein architecture, primarily through the powerful technique of X-ray crystallography, provides critical insights into biological function and drives modern drug development.

The Principle of Structure Determination by X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography is a premier method for visualizing the atomic structure of crystallized proteins, providing a detailed snapshot of their 3D architecture [1]. The technique relies on a fundamental principle of physics: when a beam of X-rays strikes a crystalline lattice, it scatters in a phenomenon known as diffraction. The resulting diffraction pattern, a collection of discrete spots captured on a detector, encodes information about the electron density within the crystal.

The birth of this field is credited to Max von Laue, who discovered the diffraction of X-rays by crystals, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 [8]. This was later formalized by William Lawrence Bragg, who formulated the seminal Bragg's Law:

This equation describes the condition for constructive interference, where n is an integer, λ is the wavelength of the X-rays, d is the distance between atomic lattice planes in the crystal, and θ is the angle of incidence. By measuring the angles and intensities of the diffracted beams, it is possible to compute a 3D electron density map and build an atomic model of the protein [3].

A Step-by-Step Technical Workflow

The process of determining a protein structure via X-ray crystallography is methodical and involves several critical stages, each with its own technical challenges and requirements.

Protein Purification and Crystallization

The journey begins with protein isolation to obtain a pure, homogeneous, and conformationally uniform sample [1] [9]. This typically involves recombinant protein expression followed by chromatographic purification. The next and often most critical hurdle is crystal formation. The purified protein solution is encouraged to form ordered, single crystals through careful manipulation of conditions like pH, temperature, and precipitant concentration [3]. This step is a major bottleneck, as not all proteins crystallize readily. Automation, using robots like the Mosquito crystallization robot which dispenses nanoliter volumes with high precision, has greatly improved the efficiency of screening thousands of crystallization conditions [9].

Data Collection and Diffraction Analysis

Once a suitable crystal is obtained, it is harvested and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen to protect it from radiation damage in the X-ray beam [3]. The crystal is then mounted on a goniometer, which precisely rotates it in the path of an X-ray source. While laboratory X-ray sources exist, modern crystallography predominantly uses synchrotron radiation sources, which provide high-intensity, focused X-ray beams that enable rapid data collection—sometimes in less than a minute [3]. As the crystal diffracts the X-rays, a detector captures the resulting pattern of spots. A complete dataset requires collecting thousands of such diffraction spots from all possible orientations of the crystal.

Phase Determination and Model Building

The intensities of the diffraction spots are used to derive structure factors. However, to calculate an electron density map, the phases of the diffracted waves are required, and this phase information is lost during data collection. This is known as the "phase problem," and solving it is a central challenge in crystallography [3]. Common methods include heavy atom replacement, where heavy atoms (e.g., selenium) are introduced into the protein crystal, and the differences in diffraction are used to deduce phase information [3].

Once phases are estimated, an electron density map is calculated via a mathematical operation called Fourier summation. Researchers then build an atomic model of the protein by fitting its known amino acid sequence into this electron density map using specialized software [3] [1].

Model Refinement and Validation

The initial structural model is iteratively refined to achieve the best fit to the experimental electron density data. This process adjusts the atomic coordinates to minimize a value called the R-factor, which gauges the agreement between the observed data and the model [3]. The final step is validation, where the model's quality and stereochemical accuracy are thoroughly checked before it is deposited in the public Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3] [1]. The PDB itself performs validation checks before releasing the structure to the scientific community.

The workflow is summarized in the diagram below:

Interpreting Structural Data: Resolution and Quality

The quality of a crystallographic model is primarily judged by its resolution, a key parameter derived from the diffraction data [3]. Resolution reflects the level of detail visible in the electron density map and is a major determinant of the model's accuracy. The following table summarizes the interpretation of different resolution ranges:

Table: Interpretation of Resolution in X-ray Crystallography

| Resolution Range | Classification | Structural Details Observable |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 5.0 Å | Low Resolution | The overall shape of the protein molecule is distinguishable; alpha-helices are visible as rods [3]. |

| 3.5 - 2.5 Å | Medium Resolution | Side chains begin to be distinguishable, allowing the model to be built; water molecules may be visible at better than 2.8 Å [3]. |

| ≥ 2.4 Å | Atomic Resolution | Detailed atomic modeling is possible; many solvent molecules can be identified and built into the density map [3]. |

Successful structure determination relies on a suite of specialized reagents, equipment, and software. The table below details key resources used in a typical crystallography pipeline.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for X-ray Crystallography

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Homogeneous Protein Sample | Biological Reagent | A pure, conformationally uniform sample is the foundational starting material for successful crystallization [9]. |

| Crystallization Screen Solutions | Chemical Reagent | Pre-formulated solutions varying precipitants, salts, pH, etc., to empirically identify initial crystal growth conditions [9]. |

| Mosquito Robot | Laboratory Equipment | Automates the setup of crystallization trials by dispensing nanoliter-volume droplets with high precision, increasing throughput and reproducibility [9]. |

| Synchrotron Beamline | Large-Scale Facility | Provides a high-intensity, tunable X-ray source for rapid and high-resolution data collection, essential for modern crystallography [3]. |

| Cryoprotectant | Chemical Reagent | A compound (e.g., glycerol) used to protect the protein crystal from ice formation during flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen [3]. |

| Software for Data Processing | Computational Tool | Specialized packages for processing raw diffraction data ("data reduction"), solving structures, and refining models (e.g., PHENIX, CCP4) [3]. |

Application to Drug Discovery: From Structure to Therapy

The impact of protein structures on drug discovery is profound. Knowing the precise 3D structure of a therapeutic target, such as a enzyme or receptor, allows for rational drug design. Researchers can design small molecules that fit snugly into active sites or allosteric pockets to inhibit or activate the protein's function [10].

Analysis of ligands bound to proteins in the PDB reveals that most therapeutic molecules tend toward linear and planar geometries, with few having highly 3D conformations [10]. This "flatness" is partly due to synthetic challenges and adherence to rules for oral bioavailability. There is a growing recognition of the potential utility of libraries with greater 3D topological diversity to explore a wider range of biological targets and improve the success of drug discovery campaigns [10]. By studying protein-ligand complexes, scientists can optimize interactions like hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts, leading to more potent and selective drug candidates.

While X-ray crystallography remains a cornerstone of structural biology, the field is continuously evolving. Techniques like serial crystallography allow data collection from microcrystals, opening avenues for studying challenging proteins [1]. Furthermore, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful complementary technique, enabling the determination of high-resolution structures for proteins that are difficult to crystallize [1].

In conclusion, the determination of protein structure is indispensable for linking 3D architecture to biological function. X-ray crystallography provides a detailed, atomic-level view that is critical for understanding disease mechanisms and designing the next generation of targeted therapeutics. As technologies advance, our ability to visualize and interpret the molecular machinery of life will continue to deepen, fueling ongoing innovation in biomedicine and drug discovery.

X-ray crystallography stands as one of the most transformative techniques in the history of biology, enabling scientists to decipher the three-dimensional atomic structure of biological macromolecules. This breakthrough methodology has fundamentally advanced our understanding of life processes at the molecular level, from enzyme catalysis and immune recognition to genetic inheritance and disease mechanisms. The ability to visualize protein structures has revolutionized fields ranging from molecular biology and biochemistry to pharmaceutical development and biotechnology. This comprehensive review traces the key historical milestones of crystallography in biology, detailing the experimental protocols that enabled these discoveries and examining the technique's profound impact on modern biological research and drug development. By understanding this historical trajectory and the underlying methodologies, researchers can better appreciate both the current capabilities and future directions of structural biology.

Historical Timeline of Key Milestones

The application of X-ray crystallography to biological problems has unfolded over more than a century of innovation, with each breakthrough building upon previous technical and conceptual advances. The table below summarizes the pivotal moments in this scientific journey.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Biological X-ray Crystallography

| Year | Milestone Achievement | Key Researchers/Group | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1912 | First X-ray diffraction pattern from a crystal (copper sulfate) | Max von Laue, Walter Friedrich, Paul Knipping [11] | Established crystals as diffraction gratings for X-rays, founding the field of X-ray crystallography |

| 1913 | Formulation of Bragg's Law | William Lawrence Bragg & William Henry Bragg [11] [12] | Provided the fundamental mathematical relationship explaining X-ray diffraction by crystal planes |

| 1915 | Nobel Prize in Physics for X-ray crystal structure analysis | William Henry Bragg & William Lawrence Bragg [11] | Recognized the profound importance of X-ray crystallography for scientific discovery |

| 1934 | First X-ray diffraction data from a protein (pepsin) | J.D. Bernal & Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin [13] | Demonstrated that proteins, despite their complexity, could form crystals suitable for structural analysis |

| 1958 | First protein structure (myoglobin at 6 Å resolution) | John Kendrew [13] | Provided the first glimpse of a protein's three-dimensional structure, revealing its complex folding |

| 1960 | Structure of hemoglobin | Max Perutz [13] | Elucidated the structural basis of oxygen transport and cooperative binding in this complex protein |

| 1965 | First enzyme structure (lysozyme) | David Phillips [13] | Revealed the structural basis of enzymatic catalysis, identifying the active site and mechanism |

| 1971 | Foundation of the Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Brookhaven National Laboratory [14] | Established a central repository for structural data, enabling global sharing and collaboration |

| 1984 | Structure of the first virus | Extended structural determination to massive macromolecular complexes | |

| 2000 | Structural Genomics Initiatives launch | International consortiums | Systematized structure determination to cover entire protein fold spaces |

| 2020s | SARS-CoV-2 protein structures | Global research community [15] | Accelerated vaccine and therapeutic development during the COVID-19 pandemic |

| 2023+ | ALS beamlines deposit >10,000 protein structures | Advanced Light Source [14] | Demonstrated the high-throughput capabilities of modern synchrotron-based crystallography |

The progression from simple salt crystals to complex biological macromolecules illustrates how methodological advances have continually expanded the boundaries of what can be studied structurally. The early protein structures, while low resolution by today's standards, provided the first direct evidence that proteins had defined three-dimensional structures, confirming the thermodynamic hypothesis of protein folding. The visualization of enzyme active sites represented another transformative moment, moving biochemistry from kinetic inferences to mechanistic understanding based on atomic positioning. Contemporary structural biology continues to build upon this foundation, with recent advances including the determination of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane proteins that represent important drug targets, and the application of time-resolved crystallography to capture reaction intermediates [15].

Fundamental Principles and Experimental Protocols

Core Physical Principles

The theoretical foundation of X-ray crystallography rests on the wave nature of X-rays and the periodic arrangement of atoms within crystals. When X-rays encounter a crystalline lattice, they are scattered by the electrons surrounding the atoms. The scattered waves interfere with each other, producing a diffraction pattern when the conditions for constructive interference are met according to Bragg's Law: nλ = 2d sinθ, where n is an integer, λ is the wavelength of the incident X-ray beam, d is the spacing between atomic planes in the crystal, and θ is the angle of incidence [3] [12]. This relationship allows researchers to calculate the distances between atomic planes from measured diffraction angles.

The diffraction pattern captured on a detector represents the amplitudes of the structure factors, but the phase information is lost during measurement—this constitutes the fundamental "phase problem" in crystallography [3]. Solving this problem requires specialized methods such as molecular replacement (using a known homologous structure), multiple isomorphous replacement (using heavy atom derivatives), or anomalous dispersion (using the anomalous scattering of atoms at specific wavelengths) [3].

Protein Crystallography Workflow

The determination of a protein structure via X-ray crystallography follows a multi-step workflow with specific technical requirements at each stage. The following diagram illustrates this process:

Diagram 1: Protein X-ray Crystallography Workflow

Protein Purification and Crystallization

The process begins with the purification of the target protein to homogeneity, typically using chromatographic methods such as affinity, ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography [16] [17]. High protein purity (>95%) and conformational homogeneity are essential prerequisites for obtaining diffraction-quality crystals. The purified protein is concentrated to high levels (typically 5-20 mg/mL, depending on the protein) in an appropriate buffer [16].

Crystallization represents a critical bottleneck in structural determination and is typically achieved through vapor diffusion methods (hanging or sitting drops) [16]. In these setups, a small volume of protein solution is mixed with a precipitant solution and equilibrated against a larger reservoir containing a higher concentration of the same precipitant. Water vapor diffuses from the protein drop to the reservoir, slowly increasing the concentration of both protein and precipitant until supersaturation is achieved, promoting crystal nucleation and growth [16]. Commercial sparse matrix screens systematically explore combinations of precipitants (e.g., polyethylene glycols, salts), buffers, and additives to identify initial crystallization conditions [16].

Data Collection and Structure Solution

Once suitable crystals are obtained (typically >0.1 mm in smallest dimension), they are harvested and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen to mitigate radiation damage during data collection [3] [16]. Modern data collection occurs predominantly at synchrotron facilities, which provide high-intensity, tunable X-ray beams [3]. The crystal is mounted on a goniometer and exposed to the X-ray beam while being rotated, with diffraction patterns collected at small angular increments (typically 0.1-1.0°) [3] [16].

The resulting diffraction patterns are processed through computational "data reduction" to correct for experimental artifacts and extract structure factor amplitudes [3]. As mentioned previously, the phase problem is then solved using molecular replacement, multiple isomorphous replacement, or anomalous dispersion methods. With both amplitudes and phases determined, an electron density map is calculated through Fourier transformation, into which an atomic model is built and iteratively refined against the experimental data [3]. The quality of the structural model is assessed using validation metrics including the R-factor and R-free, with final structures typically deposited in the Protein Data Bank for public access [3].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials in Protein Crystallography

| Reagent/Material Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) of various molecular weights, ammonium sulfate, sodium chloride, MPD | Promote protein crystallization by reducing solubility and inducing supersaturation |

| Buffers | HEPES, Tris, phosphate, citrate buffers across pH range (3-10) | Maintain protein stability and consistent protonation states during crystallization |

| Additives | Various salts, divalent cations, detergents, small organics | Modulate crystallization by affecting protein interactions, particularly for challenging targets |

| Cryoprotectants | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, sucrose, low-molecular-weight PEG | Prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling by replacing water molecules in crystal lattice |

| Crystallization Plates | 24-well, 96-well format plates for sitting or hanging drops | Enable high-throughput screening of crystallization conditions with minimal sample consumption |

| Synchrotron Beamlines | Advanced Light Source (ALS), MAX IV, other international facilities | Provide high-intensity X-ray sources with advanced optics and detectors for data collection |

Impact on Biological Understanding and Drug Development

Elucidation of Biological Mechanisms

X-ray crystallography has provided unparalleled insights into fundamental biological processes by visualizing their molecular components. The technique revealed the structural basis of enzyme catalysis through the first enzyme structure (lysozyme), which showed how enzymes position substrates for reaction and stabilize transition states [13]. Subsequent structures of numerous enzymes have illuminated the chemical mechanisms underlying virtually every metabolic pathway.

In immunology, crystallography has elucidated how the immune system recognizes pathogens. Structures of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules revealed their peptide-binding grooves, explaining how the immune system displays foreign and self-peptides for T-cell recognition [13]. The structures of antibodies and their complexes with antigens have illuminated the molecular basis of immunological specificity and cross-reactivity [13].

Perhaps most famously, X-ray crystallography played a crucial role in determining the structure of DNA, with Rosalind Franklin's diffraction data from DNA fibers providing key measurements that informed the Watson-Crick model of the double helix [12]. Her "Photo 51" revealed the 3.4 Å spacing between base pairs, the 34 Å helical repeat, and the 20 Å helix diameter [12]. This breakthrough launched the era of molecular biology and our modern understanding of genetics.

Applications in Structure-Based Drug Design

The pharmaceutical industry has leveraged crystallography to transform drug discovery from a largely empirical process to a rational, structure-based endeavor. The approach involves determining the three-dimensional structure of a drug target, typically an enzyme or receptor, and using this information to design small molecules that modulate its activity. The iterative process of structure-based drug design is illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Structure-Based Drug Design Cycle

The impact of this approach is exemplified by the development of HIV protease inhibitors, where crystallographic structures of inhibitor-enzyme complexes guided the design of compounds that effectively treated AIDS [13]. Similarly, the determination of kinase structures has enabled the development of targeted cancer therapies such as imatinib (Gleevec), designed to fit specifically into the ATP-binding pocket of aberrant signaling proteins [13]. More recently, structural studies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and other viral components accelerated the development of therapeutics and vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic [15].

Crystallography continues to drive drug discovery for challenging target classes, including G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane proteins. The ability to visualize how drugs bind to their targets at atomic resolution enables more precise optimization of potency, selectivity, and physicochemical properties, ultimately leading to improved clinical candidates.

Modern Advancements and Future Perspectives

Technical Innovations in Crystallography

The field of X-ray crystallography has undergone revolutionary technical advances that have dramatically expanded its capabilities and applications. Synchrotron radiation sources have largely replaced laboratory X-ray generators, providing beams that are orders of magnitude more intense and enabling the use of smaller crystals and faster data collection [3] [14]. The development of cryo-crystallography (flash-cooling crystals to cryogenic temperatures) has mitigated radiation damage, allowing for more extensive data collection from single crystals [3].

More recently, serial crystallography approaches, particularly at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), have enabled structure determination from microcrystals that are too small for conventional methods [15]. These techniques use the "diffraction before destruction" principle, where ultrashort, extremely bright X-ray pulses collect diffraction patterns before the crystal is vaporized by the beam [15]. Serial crystallography has opened new possibilities for studying radiation-sensitive materials and for time-resolved studies of enzymatic reactions and other dynamic processes [15].

Advances in sample delivery methods have been crucial for enabling these approaches. Liquid injectors stream crystal suspensions across the X-ray beam, while fixed-target devices present crystals on solid supports [15]. These technical innovations have progressively reduced sample requirements—from gram quantities in early serial crystallography experiments to microgram amounts today—making structural studies feasible for more challenging biological targets [15].

Integration with Complementary Methods

Modern structural biology increasingly integrates crystallography with complementary techniques to address complex biological questions. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has emerged as a powerful alternative for determining structures of large macromolecular complexes that may be difficult to crystallize [13] [17]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides information about protein dynamics and solution-state conformations that complements the static snapshots from crystallography [17].

Computational methods, particularly artificial intelligence-based structure prediction as exemplified by AlphaFold2, now provide accurate models for many proteins without experimental determination [17]. These predicted structures can facilitate molecular replacement in crystallographic analyses and guide experimental design [17]. The integration of these diverse approaches represents the future of structural biology, where hybrid methodologies provide comprehensive understanding of biological macromolecules in both static and dynamic contexts.

From its origins in physics laboratories to its current status as an indispensable biological tool, X-ray crystallography has fundamentally transformed our understanding of life at the molecular level. The historical milestones outlined in this review—from the first diffraction patterns to the current era of synchrotron-based high-throughput structural biology—demonstrate how technical innovations have continuously expanded the frontiers of biological knowledge. The experimental protocols developed over decades now enable researchers to visualize biological macromolecules with atomic precision, providing insights into mechanisms of disease and facilitating rational drug design. As crystallography continues to evolve alongside complementary techniques like cryo-EM and computational prediction, its capacity to illuminate biological structure and function will undoubtedly yield further breakthroughs in basic science and therapeutic development. For researchers pursuing protein structure determination, understanding this historical context and methodological foundation provides both practical guidance and inspiration for future investigations.

The determination of three-dimensional protein structures is fundamental to modern biology and drug discovery. X-ray crystallography has been the predominant technique for elucidating atomic-level structures for over a century [18]. This guide details three interconnected concepts that form the theoretical foundation of X-ray crystallography: resolution, which defines the level of detail obtainable from an experiment; electron density, which provides the map for model building; and the phase problem, the central challenge in converting raw diffraction data into meaningful structural information.

Understanding these concepts is critical for researchers interpreting structural data and for drug development professionals relying on accurate protein models for rational drug design. Recent advances, particularly in deep learning, are transforming how we approach these fundamental problems [19] [20].

Core Concept 1: Resolution

Definition and Physical Basis

In X-ray crystallography, resolution describes the finest level of detail discernible in an experimental electron density map. It is quantitatively defined by the smallest interplanar spacing (d-spacing) for which diffraction spots can be measured, typically reported in Ångströms (Å) [16]. The relationship between the diffraction angle and resolution is governed by Bragg's Law: ( nλ = 2d \sin(θ) ), where ( d ) represents the lattice spacing, ( λ ) is the X-ray wavelength, and ( θ ) is the diffraction angle [18].

Higher resolution (corresponding to a smaller numerical value in Å) results from measuring diffraction data to wider angles and provides greater atomic detail. The quality of the crystal primarily determines the achievable resolution; well-ordered crystals with perfectly repeating unit cells produce diffraction to higher angles [16].

Resolution Ranges and Structural Interpretability

The table below summarizes how different resolution ranges affect the interpretability of electron density maps.

Table 1: Interpretation of Electron Density Maps at Various Resolution Ranges

| Resolution Range (Å) | Structural Features Resolvable | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| < 1.2 Å | Individual atoms clearly resolved; alternative conformations discernible. | Small molecule crystallography; ultra-high-resolution protein studies. |

| 1.2 - 1.8 Å | Well-resolved backbone and side chains; water molecules and ions can be placed. | High-accuracy ligand binding studies; detailed mechanism analysis. |

| 1.8 - 2.5 Å | Polypeptide chain trace is clear; bulky side chains are distinguishable. | Standard for protein-ligand complex determination and drug design. |

| 2.5 - 3.2 Å | Secondary structures (α-helices, β-sheets) are visible. | Large complexes or membrane proteins where high resolution is challenging. |

| > 3.2 Å | Course molecular outline and protein domains may be visible. | Low-resolution phasing; often combined with other data for large assemblies. |

Low-resolution data (e.g., >2.5 Å) presents a significant challenge because the resulting electron density map lacks clearly defined atomic features, making the subsequent building of an accurate atomic model subjective, time-consuming, and often intractable [19]. This creates a critical bottleneck in structure determination.

Core Concept 2: Electron Density

Theoretical Foundation

Electron density, denoted as ( ρ(\mathbf{r}) ), is a three-dimensional function that describes the distribution of electrons within the crystal's unit cell [21]. The fundamental goal of X-ray crystallography is to determine this function. The structure factors, ( F(\mathbf{h}) ), obtained from the diffraction experiment are the Fourier components of the electron density.

The mathematical relationship is given by the inverse Fourier transform: [ ρ(\mathbf{r}) = \frac{1}{V} \sum_{\mathbf{h}} e^{-2\pi i \mathbf{h} \cdot \mathbf{r}} F(\mathbf{h}) ] where ( V ) is the volume of the unit cell, ( \mathbf{r} ) is a position vector in real space, and ( \mathbf{h} ) represents the Miller indices (h, k, l) [19] [20].

From Map to Atomic Model

The electron density map is calculated using both the measured amplitudes and the estimated phases of the structure factors. A crystallographer then interprets this map to build an atomic model that fits the observed density, taking into account prior knowledge of protein chemistry, such as known amino acid sequences and standard bond lengths and angles [22]. The quality of the final atomic model is therefore directly dependent on the quality and resolution of the electron density map.

Core Concept 3: The Phase Problem

The Fundamental Challenge

The phase problem is the central obstacle in X-ray crystallography. In a diffraction experiment, the detector records only the intensity of each diffracted beam, which is proportional to the square of the structure factor amplitude, ( |F(\mathbf{h})| ) [23]. However, the structure factor is a complex number characterized by both an amplitude and a phase, ( ϕ(\mathbf{h}) ): [ F(\mathbf{h}) = |F(\mathbf{h})| e^{i ϕ(\mathbf{h})} ] The loss of phase information upon measurement is critical because both amplitude and phase are required to compute the electron density map via Fourier synthesis [23] [20]. This is often described as a holistic relationship: every detail of the real-space structure depends on the totality of information (both amplitudes and phases) in reciprocal space, and vice versa [21].

Historical and Modern Methods for Phase Retrieval

Several experimental and computational methods have been developed to solve the phase problem.

Table 2: Methods for Solving the Crystallographic Phase Problem

| Method | Underlying Principle | Key Requirements / Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Methods [23] | Uses probabilistic relationships between phases of strong reflections. | Requires atomic-resolution data (typically better than 1.2 Å). Works for small molecules, rarely for proteins. |

| Molecular Replacement (MR) [22] [24] | Uses phases from a known, homologous structure as an initial model. | Requires a previously solved structure with significant sequence or structural similarity. |

| Heavy-Atom Methods (MIR) [16] [24] | Involves comparing native data with data from crystals containing incorporated heavy atoms (e.g., Hg, Pt). | Requires derivatives that are isomorphous with the native crystal. Labor-intensive. |

| Anomalous Dispersion (MAD/SAD) [23] [24] | Uses differences in diffraction intensity near the absorption edge of an atom (e.g., Se in selenomethionine). | Requires tunable X-ray source (synchrotron) and incorporation of anomalous scatterers. |

| Patterson Methods [20] | Analyzes a Fourier map calculated with squared amplitudes and zero phases to find heavy atom positions. | Becomes uninterpretable for large structures due to peak overlap (n² peaks for n atoms). |

| Deep Learning (e.g., XDXD) [19] | An end-to-end generative model that predicts a complete atomic model directly from low-resolution diffraction data. | Bypasses traditional phasing and map interpretation; shows 70.4% match rate at 2.0 Å resolution. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these methods integrate into the overall structure determination process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful structure determination relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Crystallography

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Pure Protein Sample (>95% purity) [16] [24] | The target molecule for crystallization. High purity and homogeneity are critical for forming well-ordered crystals. | Assessed by SDS-PAGE and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). |

| Precipitant Solutions [16] [24] | Agents (e.g., PEGs, salts) that reduce protein solubility, encouraging precipitation into an ordered crystal lattice. | A "sparse matrix" of ~50 conditions is typically screened. |

| Cryoprotectants (e.g., glycerol) [16] [24] | Protect crystals from radiation damage by forming a glassy state during flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. | Replaces water in and around the crystal to prevent ice formation. |

| Heavy Atom Derivatives [16] [24] | Used in MIR phasing. Heavy atoms (e.g., Hg, Pt, Au) are incorporated into crystals to provide phasing information. | Soaked into pre-grown crystals or incorporated via protein expression (e.g., selenomethionine). |

| Detergents / Lipids [24] | Solubilize and stabilize membrane proteins for crystallization, which is a major challenge in the field. | Used in lipidic cubic phase crystallization for membrane proteins. |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

The Low-Resolution Bottleneck and AI Solutions

A significant frontier in crystallography is overcoming the limitations of low-resolution data. While methods like molecular replacement can provide initial phases, the resulting electron density maps at resolutions like 2.0 Å are often ambiguous and lack clear atomic features, making model building difficult [19].

Recent breakthroughs in deep learning are offering end-to-end solutions. For instance, the XDXD framework is a diffusion-based generative model that predicts a complete atomic model directly from low-resolution single-crystal X-ray diffraction data, bypassing the need for manual map interpretation [19]. This model has demonstrated a 70.4% match rate for structures with data limited to 2.0 Å resolution, showing robust performance on a benchmark of 24,000 experimental structures [19]. Other approaches involve using convolutional neural networks to interpret Patterson maps, which are computed directly from diffraction intensities without phase information, to produce initial electron-density estimates [20].

Emerging Experimental Modalities

Technologies like X-ray Free Electron Lasers (XFEL) are revolutionizing data collection. In serial femtosecond crystallography, a stream of microcrystals is passed through an extremely bright, pulsed XFEL beam, allowing diffraction data to be collected before the crystals are destroyed by radiation damage [22]. This enables the study of challenging samples and the capture of molecular movies of dynamic processes, such as enzyme catalysis, on femtosecond timescales [22] [24].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationship between the three essential concepts discussed in this guide.

The concepts of resolution, electron density, and the phase problem are not merely sequential steps but are deeply intertwined pillars supporting the edifice of X-ray crystallography. The quality of the final atomic model is contingent upon the resolution of the data and the accuracy of the phases obtained to compute the electron density map. For researchers and drug development professionals, a firm grasp of these principles is indispensable for critically evaluating structural models deposited in databases and for designing effective experiments. The field is dynamic, with emerging computational methods, particularly deep learning, poised to automate structure determination and overcome long-standing challenges like the low-resolution bottleneck, thereby paving the way for new discoveries in structural biology.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: From Protein Purification to Refined Model

Within the framework of protein structure determination via X-ray crystallography, the initial steps of protein purification and crystallization constitute the most significant bottleneck, often determining the success or failure of entire structural initiatives. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of this critical phase, detailing the foundational principles of crystallization, comprehensive purification methodologies, and contemporary experimental protocols. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current practices with emerging trends—such as AI integration and microfluidics—that are poised to alleviate these longstanding challenges. The content is contextualized within the growing protein crystallization market, which is projected to expand from $1.62 billion in 2024 to $2.8 billion by 2029, driven largely by demands in biopharmaceutical development [25] [26].

The Premise of Protein Crystallization

Protein crystallization is the process of inducing proteins to form a highly ordered, three-dimensional lattice. The fundamental principle governing this process is supersaturation [27] [28]. A protein solution becomes supersaturated when the concentration of the protein exceeds its solubility limit under specific chemical and physical conditions. This non-equilibrium state drives the first-order phase transition of nucleation, where spontaneous clusters of protein molecules (nuclei) form and become stable enough to serve as templates for crystal growth [27].

The path from an undersaturated solution to a viable crystal is typically visualized using a phase diagram, which plots protein concentration against precipitant concentration. This diagram reveals several key zones:

- Undersaturated Zone (Stable): The protein remains fully soluble. No crystallization occurs.

- Metastable Zone: Nuclei may form but are metastable. Crystal growth can occur if seeds are present, but new nucleation is unlikely.

- Labile Zone (Nucleation): The region of highest supersaturation where spontaneous nucleation and crystal growth can occur.

- Precipitation Zone: Excessive supersaturation leads to disordered, amorphous aggregation instead of ordered crystals [27] [29].

The objective of any crystallization experiment is to navigate the solution from the undersaturated zone into the labile zone to initiate nucleation, and then to maintain conditions in the metastable zone to allow for slow, ordered crystal growth [27]. The success of this process is highly dependent on the precise control of numerous variables, including pH, temperature, ionic strength, and the nature of the precipitating agent.

The Imperative of High-Quality Protein Purification

The journey to a high-resolution structure begins with the production of a pure, monodisperse, and stable protein sample. The homogeneity of the preparation is arguably the most critical factor in obtaining crystals that diffract to high resolution [30] [28].

Core Purification Methodologies

A combination of chromatographic techniques is typically employed to achieve the requisite purity (>95-99%) [30] [31].

Table 1: Key Chromatographic Techniques for Protein Purification

| Technique | Principle of Separation | Primary Application in Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Chromatography | Utilizes highly specific biological interactions (e.g., His-tag/Ni-NTA, antibody/Protein A) [30]. | Initial capture and significant purification in a single step. |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography | Separates proteins based on their net surface charge. | Polishing step to remove impurities and isoforms with minor charge differences. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Separates molecules based on their hydrodynamic radius or size [30]. | Final polishing step to isolate monodisperse populations and remove aggregates. |

Analysis of Purity and Monodispersity

Beyond chromatographic purity, the conformational homogeneity of a protein sample is vital. Techniques used for assessment include:

- SDS-PAGE: Confirms denaturing purity and approximate molecular weight.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measures the hydrodynamic radius of particles in solution, providing a critical assessment of monodispersity. A single, narrow peak is indicative of a homogeneous sample suitable for crystallization trials [30].

- Mass Spectrometry: Verifies protein identity and can analyze post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation) that can hinder crystallization [30].

Experimental Crystallization Protocols

Once a pure protein sample is concentrated to a suitable level (typically 5-50 mg/mL), systematic crystallization trials begin [28]. Several established methods are used to achieve supersaturation in a controlled manner.

Vapor Diffusion (Hanging and Sitting Drop)

Vapor diffusion is the most widely used technique in high-throughput crystallization screens [27] [28]. The following protocol is typical for a 24-well tray setup:

Materials: Protein sample (≥ 5 mg/mL), 24-well hanging or sitting drop tray, reservoir solutions (precipitants, buffers, salts), silicon grease, siliconized cover slides, micropipette with low-retention tips [28].

Procedure:

- Reservoir Preparation: Fill each well of the tray with 500 μL of a precipitant solution [28].

- Sealing: For hanging drop, place a greased ring around the rim of each well. For sitting drop, optically clear tape is used later [28].

- Drop Setup:

- On a clean cover slide (hanging) or on the shelf (sitting), pipette 1-2 μL of concentrated protein.

- Add an equal volume of reservoir solution to the protein drop, mixing carefully to avoid bubbles [28].

- Sealing and Incubation: For hanging drop, invert the cover slide and carefully place it over the well, pressing down to form a seal. For sitting drop, seal the entire tray row with transparent tape. Place the tray in a stable, vibration-free incubator at a controlled temperature (commonly 4°C or 20°C) [28].

- Monitoring: Check trays daily for crystal growth, handling with extreme care to prevent disturbances. Crystals can appear within hours or take several months [28].

Principle: The drop containing protein and precipitant is initially at a lower concentration than the reservoir. Water vapor diffuses from the drop to the reservoir, slowly concentrating both the protein and the precipitant in the drop until equilibrium is reached. This gradual increase in concentration ideally drives the solution into the labile zone for nucleation and then into the metastable zone for crystal growth [27] [28].

Batch Crystallization under Oil

Batch crystallization is a method where the protein is immediately mixed into a supersaturated state [27] [28].

Materials: Protein sample, 96-well microbatch tray, paraffin/mineral oil mixture, micropipette [28].

Procedure:

- Fill the wells of the microbatch tray with oil to a depth of about 3 mm [28].

- Pipette 1 μL of protein solution directly to the bottom of an oil-filled well.

- Add 1 μL of precipitant solution to the same well, ensuring it fuses with the protein droplet [28].

- Seal the tray and incubate under stable conditions.

Principle: The protein and precipitant are mixed at their final concentrations, immediately establishing supersaturation. The layer of inert oil prevents evaporation of water from the drop, allowing for very small volumes and protecting the sample from airborne contamination [27] [28]. This method is particularly useful for producing microcrystals for serial crystallography experiments [27].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in the purification and crystallization process:

Navigating the Crystallization Bottleneck: Challenges and Optimization

Despite standardized protocols, crystallization remains the primary unpredictable element in structure determination. Key challenges and optimization strategies include:

Intrinsic Protein Challenges

- Membrane Proteins: Their hydrophobic nature requires detergents or lipidic cubic phases (e.g., monoolein) for solubilization, which drastically complicates the phase diagram and crystal lattice formation [27] [29]. As of 2010, membrane proteins represented less than 0.5% of non-redundant entries in the PDB [29].

- Flexible Regions: Dynamic loops and termini prevent the formation of a repeating lattice. Construct optimization via limited proteolysis, sequence alignment, and truncation of flexible regions is a common and often essential strategy to rigidify the protein [27]. For example, truncations in S. typhimurium aspartate receptor improved crystal diffraction from 3.0 Å to 1.85 Å [27].

Screening and Additives

- Sparse Matrix Screening: Initial screens use incomplete factorial design to test a wide range of conditions (pH, precipitants, salts) with minimal experiments [28]. Commercial screens are widely available.

- Rational Additives: Small molecules, cofactors, ligands, or specific ions can enhance crystal quality by stabilizing a particular protein conformation or mediating crystal contacts [27] [30]. For instance, introducing antibody fragments or using PDZ domains as scaffolding modules can facilitate nucleation for problematic targets [27].

Table 2: Common Precipitants and Additives in Crystallization Screens

| Category | Examples | Mode of Action | Frequency of Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salts | Ammonium Sulfate, Sodium Chloride | Reduces protein solubility by competing for water molecules (salting out). | High (~30% of conditions) [28] |

| Polymers | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 3350, PEG 1000 | Excludes volume, increasing effective protein concentration. | Very High (~30% of conditions) [27] [28] |

| Organic Solvents | MPD, Ethanol, Isopropanol | Reduces dielectric constant of solution, promoting association. | Moderate |

| Additives | Ions (e.g., Zn²⁺), Ligands, Detergents | Stabilizes specific conformations or mediates crystal contacts. | Condition-dependent [27] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful crystallization pipeline relies on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Protein Crystallization

| Item | Function | Example Vendors/Products |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Plates | Platforms for setting up nanoliter- to microliter-scale trials. | 24-well hanging/sitting drop trays; 96-well microbatch trays [28]. |

| Sparse Matrix Screens | Pre-formulated solutions to efficiently sample chemical space. | Hampton Research (Crystal Screen), Molecular Dimensions (JCSG+), Rigaku (Morpheus) [32] [28]. |

| Precipitant Reagents | Chemicals to induce supersaturation. | PEGs, Ammonium Sulfate, MPD [27] [28]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Agents like glycerol to protect crystals during flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen. | Glycerol, Ethylene Glycol, Paratone-N Oil [25] [30]. |

| Liquid Handling Robots | Automation for high-throughput, reproducible screen setup. | Tecan Group, Formulatrix Inc., SPT Labtech's mosquito crystal [25] [26]. |

Future Perspectives and Market Context

The persistent challenge of the crystallization bottleneck is driving innovation and significant market growth. The global protein crystallization market is projected to grow from $1.62 billion in 2024 to $2.8 billion by 2029, at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 11.5% [25]. Key trends shaping the future include:

- Automation and AI: Integration of artificial intelligence for predicting crystallization conditions and automated imaging systems for crystal detection is becoming standard, improving success rates and throughput [25] [26].

- Microfluidics: These platforms reduce sample volume requirements to nanoliters, enabling thousands of conditions to be screened with minimal protein material [29] [26].

- Advanced Light Sources: Techniques like serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) at X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs) allow the use of microcrystals, thereby lowering the barrier for proteins that only form small crystals [30] [22].

- Hybrid Methods: The rise of cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) provides an alternative for structures that are persistently recalcitrant to crystallization, especially large complexes and membrane proteins [30] [22].

Protein purification and crystallization represent the critical, rate-limiting step in de novo structure determination via X-ray crystallography. Mastering this phase requires a deep understanding of biophysical principles, meticulous execution of purification and screening protocols, and strategic optimization. While it remains a significant bottleneck, ongoing technological advancements in automation, microfluidics, and computational prediction are steadily increasing the throughput and success rates. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, a rigorous and systematic approach to this first step is the indispensable foundation upon which all subsequent atomic insights are built.

Modern macromolecular X-ray crystallography predominantly relies on synchrotron radiation sources, which have revolutionized the field by providing X-ray beams of unparalleled intensity and quality. These facilities have become indispensable for structural biology, enabling the determination of over 70% of all macromolecular structures in the Protein Data Bank [33]. Synchrotrons generate X-rays through the acceleration of charged particles in magnetic fields, producing beams that are orders of magnitude more brilliant than traditional laboratory X-ray sources [33]. This high brilliance enables researchers to work with smaller crystals, collect data at higher resolutions, and employ advanced experimental techniques such as anomalous dispersion for solving the phase problem in crystallography.

The evolution of synchrotron sources has progressed through distinct generations, each offering significant improvements in beam characteristics and experimental capabilities. Fourth-generation synchrotrons, such as those featuring multi-bend achromat lattice designs, provide dramatically increased coherent flux, enabling novel imaging techniques like coherent X-ray diffraction imaging (CXDI) and expanding the possibilities for studying non-crystalline biological specimens [34]. These advanced sources offer unprecedented opportunities for structural biology, particularly when combined with the latest detector technologies and experimental methodologies.

Key Components of a Synchrotron Beamline

A synchrotron beamline consists of several critical components that work together to deliver optimized X-ray beams for protein crystallography experiments:

Front End and Optics: The beamline begins with insertion devices (undulators or wigglers) that generate specific X-ray characteristics. This is followed by sophisticated optical systems including monochromators for selecting X-ray wavelengths and mirrors for focusing and harmonic rejection. Modern beamlines often feature micro-focusing optics that can produce beam sizes below 10 microns, enabling data collection from microcrystals [15].

Experimental Station: The core of the beamline contains a goniometer for precise crystal positioning and rotation, sample visualization systems, and a detector positioned at optimal distance from the sample. Cryogenic cooling systems are standard for conventional data collection, while specialized environmental chambers are available for room-temperature studies [35].

Robotic Sample Handling: Automated sample changers, such as systems capable of storing 460 samples in liquid nitrogen, allow for high-throughput data collection by automatically mounting and centering crystals in the X-ray beam [3]. This automation has dramatically increased the efficiency of synchrotron facilities, enabling the collection of multiple complete datasets per hour.

Beam Conditioning: Advanced beamlines incorporate adaptive optics and collimation systems to optimize beam characteristics for specific experiments, such as serial crystallography or time-resolved studies.

Modern X-ray Detectors: Technology and Performance

The development of modern X-ray detectors represents a critical advancement in macromolecular crystallography. Current detectors predominantly use hybrid photon counting technology, which provides noise-free detection with high dynamic range and fast readout capabilities [36]. These detectors directly convert X-ray photons into electrical charge, enabling precise counting of individual photons without readout noise.

Table 1: Modern X-ray Detectors for Synchrotron Crystallography

| Detector Model | Technology | Pixel Size | Frame Rate | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIGER2 [36] | Photon-counting | 75 µm | High (kHz range) | High dynamic range, no readout noise | Still/multi-series collection, SX |

| PILATUS4 [36] | Photon-counting | 150 µm | Moderate | Renewed version of popular PILATUS | Standard rotation data collection |

| SELUN [36] | Hybrid Photon Counting | Not specified | 120,000 fps | Sustained frame rate at high count rates | 4th-gen synchrotrons, high-speed SX |

| MYTHEN2 [36] | Microstrip photon-counting | Strip detector | Continuous | Compact, modular design | Specialized applications |

The performance characteristics of modern detectors have enabled new experimental modalities in crystallography. High frame rates are essential for serial crystallography, where thousands of diffraction patterns must be collected in rapid succession [15]. The absence of readout noise ensures accurate measurement of weak diffraction signals, which is particularly important for detecting high-resolution information and for working with small crystals that produce weak diffraction.

Data Collection Strategies and Methodologies

Conventional Rotation Data Collection

Traditional macromolecular crystallography employs the rotation method, where a single crystal is continuously rotated in the X-ray beam while collecting diffraction images at small angular intervals (typically 0.1-1°). This method requires well-diffracting crystals of sufficient size (typically >10-50 μm) and remains the workhorse for most structural biology projects [3]. The crystal is maintained at cryogenic temperatures (approximately 100 K) to mitigate radiation damage, allowing complete datasets to be collected from individual crystals [35].

The optimal data collection strategy depends on crystal characteristics including symmetry, unit cell dimensions, and diffraction quality. Modern beamline control software automatically determines optimal rotation ranges, exposure times, and beam parameters to maximize data quality while minimizing radiation damage. Complete datasets can typically be collected within minutes at modern synchrotron beamlines, a dramatic improvement over the hours or days required with earlier generations of synchrotron sources or laboratory X-ray generators [3].

Serial Crystallography Methods

Serial crystallography (SX) has emerged as a powerful alternative approach, particularly for challenging systems that only produce microcrystals. This method involves collecting diffraction "still" images from thousands of microcrystals, with each crystal typically exposed to a single X-ray pulse before being replaced [15]. The individual diffraction patterns are then indexed and merged to create a complete dataset.

Table 2: Serial Crystallography Delivery Methods and Sample Consumption

| Delivery Method | Principle | Sample Consumption | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection [15] | Crystal slurry injected as liquid stream | ~μL to mL range | High speed, compatibility with time-resolved studies | High sample waste, jet stability issues |

| Fixed-Target [35] | Crystals mounted on solid support | <1 μL | Minimal sample waste, compatibility with slow data collection | Lower throughput, potential background scattering |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion [15] | Crystal suspension in viscous matrix | Reduced waste compared to liquid injection | Reduced flow rates, lower background | Potential damage to crystals, complex operation |

Serial crystallography can be performed at both X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), where it is termed serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX), and at synchrotrons, where it is known as serial millisecond crystallography (SMX) [15]. The "diffraction before destruction" approach at XFELs uses ultrashort femtosecond pulses to outrun radiation damage, while SMX at synchrotrons distributes dose across many crystals to minimize damage [15].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making process and workflow for X-ray data collection at synchrotrons:

Sample Preparation and Mounting

For conventional crystallography, crystals are harvested from crystallization drops and cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen to prevent radiation damage. This process requires adding cryoprotectants to prevent ice formation during freezing [3]. Crystals are then mounted on standardized pins and stored in automated sample changers until data collection.

For fixed-target serial crystallography, advanced approaches involve growing crystals directly on microporous sample holders containing multiple compartments for different protein/ligand complexes [35]. After crystal growth, crystallization solution is removed by blotting through the porous membrane, and ligand solutions are added by pipetting. This approach minimizes sample handling and enables high-throughput screening.

Data Collection Parameters

Critical parameters for data collection include:

Beam Energy: Typically selected between 5-15 keV (0.8-2.5 Å wavelength), with specific energies chosen for anomalous diffraction experiments near elemental absorption edges [33].

Detector Distance: Optimized based on desired resolution, with larger distances providing higher resolution but requiring longer exposure times.

Exposure Time: Balanced between achieving sufficient signal-to-noise and minimizing radiation damage, typically ranging from milliseconds to seconds per image.

Rotation Range: Complete datasets typically require 180-360° of total rotation, depending on crystal symmetry.

Beam Size: Matched to crystal dimensions to minimize background scattering, with micro-focus beams (<10 μm) used for microcrystals [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synchrotron Data Collection

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cryoprotectants [3] | Prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, or commercial solutions; concentration optimized empirically |

| Crystal Mounting Loops [3] | Secure crystal during data collection | Various sizes matched to crystal dimensions; nylon or micro-meshed |

| Microporous Sample Holders [35] | Fixed-target serial crystallography | Enable on-chip crystallization and ligand soaking; 12 compartments for high-throughput |

| Crystallization Screens [37] | Initial crystal condition screening | Commercial 96-well format screens; require ~100-250 μL of purified protein |

| Liquid Handling Robots [37] | Automated crystallization setup | Mosquito robot for nanoliter-volume dispensing; improves reproducibility |

| Fragment Libraries [35] | Ligand screening | F2X entry library (95 molecules) for identifying protein-ligand interactions |

Advanced Applications: Room-Temperature and Time-Resolved Studies

Recent advancements have enabled more physiologically relevant data collection through room-temperature serial crystallography. This approach captures protein conformations closer to native states and can reveal previously unobserved conformational states [35]. Fixed-target serial crystallography has been advanced to enable high-throughput fragment screening at room temperature, achieving resolutions comparable to cryogenic methods while providing insights into biologically relevant protein dynamics [35].

Time-resolved serial crystallography (TR-SX) represents another frontier, enabling the visualization of reaction intermediates in biological processes. Two primary approaches have been developed: light-activated studies using pump-probe lasers for photosensitive proteins, and mix-and-inject serial crystallography (MISC) for enzyme-substrate interactions [15]. These "molecular movie" techniques allow researchers to observe structural changes in real-time, providing unprecedented insights into biochemical mechanisms.

Data Quality Assessment and Optimization

The quality of X-ray diffraction data fundamentally determines the achievable resolution and accuracy of the final atomic model. Key quality metrics include:

Resolution: Determined by the smallest Bragg spacing (dmin) measurable from the diffraction pattern. Higher resolution (lower dmin values) provides greater atomic detail:

Completeness and Redundancy: Essential for accurate intensity measurement and reduction of random errors. Modern detectors and collection strategies typically achieve >95% completeness and high redundancy.

Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Determined by crystal quality, beam intensity, and detector performance. Photon-counting detectors provide essentially noise-free detection [36].

Radiation Damage Management: Particularly critical for room-temperature data collection, where radiation sensitivity is more than 100 times higher than at cryogenic temperatures [35]. Serial crystallography approaches mitigate this by distributing dose across many crystals.