Protein Structure Validation from X-Ray Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI Integration

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating protein structures determined by X-ray crystallography.

Protein Structure Validation from X-Ray Data: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI Integration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating protein structures determined by X-ray crystallography. It covers the foundational principles of why validation is critical, detailed methodological workflows for application, strategies for troubleshooting common issues, and comparative validation techniques. The scope also explores the growing integration of artificial intelligence, which is revolutionizing both structure prediction and validation processes, offering insights into how these tools complement traditional experimental data to enhance model accuracy and reliability in biomedical research.

The Critical Role of Validation in Protein X-Ray Crystallography

Why Protein Structure Validation is Non-Negotiable

In structural biology, determining a protein's three-dimensional architecture is merely the first step; validating its accuracy and reliability is non-negotiable. This is because protein structures serve as fundamental frameworks for understanding molecular mechanisms, guiding rational drug design, and interpreting cellular processes. With approximately 85% of all known protein structures determined using X-ray crystallography, the methodology stands as a predominant technique in the field [1]. However, the process from crystal to coordinates involves numerous steps where errors can be introduced, making rigorous validation an essential checkpoint before any biological conclusions can be drawn. This guide examines why validation is indispensable, objectively compares validation methodologies, and provides practical resources for implementing robust validation protocols.

Core Principles of Protein Structure Validation

Core Validation Metrics and Their Interpretations

Protein structure validation employs a suite of quantitative metrics that assess different aspects of model quality. The table below summarizes the key metrics and their significance:

Table 1: Essential Validation Metrics for Protein Structures

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Optimal Range/Value | What It Assesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Quality | Ramachandran plot outliers | >90% in favored regions [2] | Backbone dihedral angle sanity |

| Bond length deviations | Within 0.02 Å [2] | Accuracy of covalent geometry | |

| Bond angle deviations | Within 2° [2] | Accuracy of bond angles | |

| Model-Data Fit | R-factor | Lower values (~0.2 or 20%) [2] | Fit between model and experimental data |

| R-free | Close to R-factor [2] | Validation without overfitting | |

| Steric Quality | Clashscore | Lower values preferred [2] | Steric clashes between atoms |

| Data Quality | Resolution | Lower values (<2.0 Å) [2] | Detail level of experimental data |

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Different experimental and computational methods for structure determination face unique validation challenges. The table below provides a comparative overview:

Table 2: Validation Challenges Across Structure Determination Methods

| Method | Primary Validation Focus | Common Artifacts/Issues | Key Validation Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Model-to-data fit, crystal packing effects, ligand validation [3] | Over-refinement, poor electron density fit [2] | R/R-free, Ramachandran plots, real-space correlation [1] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Distance restraint violations, ensemble reliability [4] | Insufficient restraints, conformational averaging | Restraint violation analysis, ensemble RMSD [4] |

| Cryo-EM | Map-model correlation, resolution variation [2] | Masking effects, flexible region modeling | Map-model FSC, local resolution [2] |

| Computational Models (AlphaFold2) | Structural plausibility, confidence metrics [5] | Flexible regions, novel folds without templates [6] | pLDDT, predicted aligned error, comparison to experimental data [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Structure Validation

Comprehensive Crystallography Validation Workflow

The validation process for an X-ray crystal structure is methodical and multi-stage, ensuring that the final model accurately represents both the experimental data and chemically reasonable geometry.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Validation Experiments

1. Real-Space Ligand Validation with Electron Density

- Objective: To verify that ligand molecules are properly supported by experimental electron density data [3].

- Protocol:

- Calculate an mFo-DFc (difference) electron density map contoured at 3σ to highlight features not accounted for by the protein model [3].

- Generate a 2mFo-DFc map contoured at 1σ to visualize the overall electron density.

- Examine the ligand's atomic positions for clear, continuous density in both maps.

- Use real-space correlation coefficients (RSCC) to quantify fit – values >0.8 indicate good fit [3].

- Data Interpretation: Poor density may indicate partial occupancy, incorrect identity, or conformational disorder. Emerging deep learning approaches using 3D point cloud representations of ligand density show promise for automated validation, achieving segmentation accuracies with F1-scores up to 87.0% [3].

2. Ramachandran Plot Analysis for Backbone Validation

- Objective: To assess the stereochemical quality of protein backbone conformations [2].

- Protocol:

- Calculate dihedral angles φ and ψ for all non-proline, non-glycine residues.

- Plot these angles against known allowed regions for protein backbone conformations.

- Calculate the percentage of residues in favored, allowed, and outlier regions.

- Data Interpretation: High-quality structures typically have >90% of residues in favored regions. Outliers may indicate errors in tracing or regions of genuine strain.

3. Model Refinement Validation with R-free Analysis

- Objective: To prevent overfitting during structure refinement [2].

- Protocol:

- Set aside 5-10% of reflection data before refinement begins.

- Perform refinement against the working set (remaining 90-95% of data).

- Calculate R and R-free factors after each refinement cycle.

- Monitor that R-free remains close to the R-factor (typically within 0.05).

- Data Interpretation: A significantly higher R-free than R-factor suggests overfitting. The structure should be re-examined and refinement strategies adjusted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful structure validation requires both computational tools and experimental reagents. The table below details essential components of a comprehensive validation toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Structure Validation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Crystal Screens | Sparse matrix screens for initial crystallization condition identification [7] | Protein crystallization optimization |

| Cryoprotectants | Compounds (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) to prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling [7] | Data collection from flash-cooled crystals |

| MolProbity Server | All-in-one validation service for steric clashes, rotamers, and geometry [2] | Final structure validation before deposition |

| Phenix Software Suite | Comprehensive package for crystallographic structure solution, refinement, and validation [1] | Throughout structure determination process |

| COOT Software | Model building and real-space refinement against electron density maps [1] | Manual model correction and ligand fitting |

| Dimple v2.6.1 | Automated pipeline for molecular replacement and map calculation [3] | Standardized refinement to highlight ligand density |

| Gemmi v0.5.8 | Library for handling crystallographic data and creating 3D point clouds [3] | Advanced ligand density analysis and machine learning applications |

Case Studies in Validation: From Crystallography to AI Prediction

Validating AlphaFold2 Predictions Against Experimental Data

The emergence of highly accurate computational structure predictions from tools like AlphaFold2 has created new validation challenges and opportunities. In one assessment, AF2 predictions for centrosomal proteins CEP192 and CEP44 were compared to experimental crystal structures [5]. The CEP44 CH domain prediction aligned with the experimental structure with an impressive RMSD of 0.74 Å over 116 residues, outperforming the closest homologous template (RMSD 2.8-3.1 Å) [5]. This case demonstrates that while AF2 predictions can be remarkably accurate, experimental validation remains essential – the AF2 model for the CEP192 Spd2 domain, while generally correct (RMSD 1.83 Å), contained regions with only moderate confidence scores (pLDDT 70-90) that required experimental verification [5].

Ligand Validation in Drug Discovery Contexts

Ligand validation presents particular challenges in structural biology. Traditional validation approaches for known ligands achieve identification accuracies between 32-72.5%, leaving significant room for error [3]. Emerging deep learning methods using 3D point cloud representations of ligand electron density show promise, with validated models achieving mean intersection-over-union (IoU) accuracies up to 77.4% in cross-validation studies [3]. This advancement is particularly crucial for drug discovery, where misplaced ligands can derail entire development programs.

Protein structure validation is fundamentally non-negotiable because structural models form the foundation for downstream biological interpretations and applications. As structural biology continues to evolve with new techniques like Cryo-EM and powerful AI prediction tools, the principles of rigorous validation must remain central to the field. The most robust structural insights emerge when multiple validation approaches converge – when geometric quality checks align with model-to-data fit metrics and biological plausibility. By implementing comprehensive validation protocols, utilizing the appropriate toolkit of reagents and software, and maintaining skeptical scrutiny of all structural models, researchers can ensure that the frameworks they build truly support the weight of scientific discovery.

X-ray crystallography stands as the cornerstone of structural biology, providing the atomic-resolution details that underpin our understanding of biological macromolecules. Despite the emergence of competing techniques and computational methods like AlphaFold, X-ray crystallography remains the dominant experimental method for determining three-dimensional protein structures, accounting for approximately 66-84% of all structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) annually [8] [9]. Its enduring predominance stems from its ability to deliver precise atomic coordinates that are indispensable for elucidating enzyme mechanisms, understanding protein-ligand interactions, and facilitating rational drug design. Within the context of structural validation, crystallography provides the foundational experimental data against which computational models and structures determined by other methods are often evaluated, creating an essential feedback loop for improving accuracy across structural biology.

The technique's supremacy is evident in the numbers: as of September 2024, over 224,000 protein structures have been deposited in the PDB, with over 86% determined using X-ray crystallography [8]. While cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) has seen a dramatic increase in usage in recent years, accounting for up to 40% of new deposits by 2023-2024, crystallography continues to produce the majority of structures released each year [8]. This sustained dominance reflects the technique's maturity, reliability, and suitability for high-throughput structure determination, particularly in industrial drug discovery settings where atomic-level detail of protein-ligand complexes guides the design of more potent and specific therapeutic compounds [9].

Quantitative Technique Comparison

The landscape of experimental structural biology is primarily shaped by three techniques: X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Each method possesses distinct strengths, limitations, and ideal application domains, which are quantified in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Structural Biology Techniques

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy | Cryo-Electron Microscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Atomic (0.5 - 3.0 Å) | Atomic (for defined regions) | Near-atomic to Atomic (2.0 - 4.5 Å) |

| Sample Requirement | 5 mg at ~10 mg/mL (Crystallization) [9] | >200 µM in 250-500 µL [9] | <0.1 mg (for current methods) [10] |

| Sample State | Crystalline solid | Solution | Vitreous ice |

| Size Limitations | No strict upper limit; larger complexes are harder to crystallize [9] | Typically < 25-30 kDa for full structure [9] | Ideal for large complexes > 150 kDa |

| Throughput | High (especially with synchrotrons) | Low to Medium | Medium (increasing rapidly) |

| Key Advantage | High-resolution, high-throughput | Studies dynamics in solution | Handles large complexes, minimal sample prep |

| Key Limitation | Requires diffraction-quality crystals | Sample size and concentration requirements | Resolution can be heterogeneous |

| PDB Share (2023) | ~66% (9,601 structures) [8] | ~1.9% (272 structures) [8] | ~31.7% (4,579 structures) [8] |

The data reveals a clear technical division. X-ray crystallography is the workhorse for high-resolution structure determination at scale. NMR spectroscopy, while providing unique insights into protein dynamics and interactions in solution, contributes less than 10% annually to the PDB due to its limitations with larger proteins and lower throughput [8] [9]. The rise of cryo-EM is the most significant recent development, now accounting for a substantial portion of new deposits, particularly for very large complexes that are difficult to crystallize [8]. However, crystallography remains preeminent for obtaining the precise atomic-level information critical for understanding enzyme mechanisms and for structure-based drug design, where the exact positioning of atoms in a ligand-binding pocket is paramount [9].

Experimental Protocol: From Protein to Structure

The journey to a protein structure via X-ray crystallography is a multi-stage process, each with its own critical requirements and potential bottlenecks. Understanding this workflow is essential for appreciating both the power and the challenges of the technique.

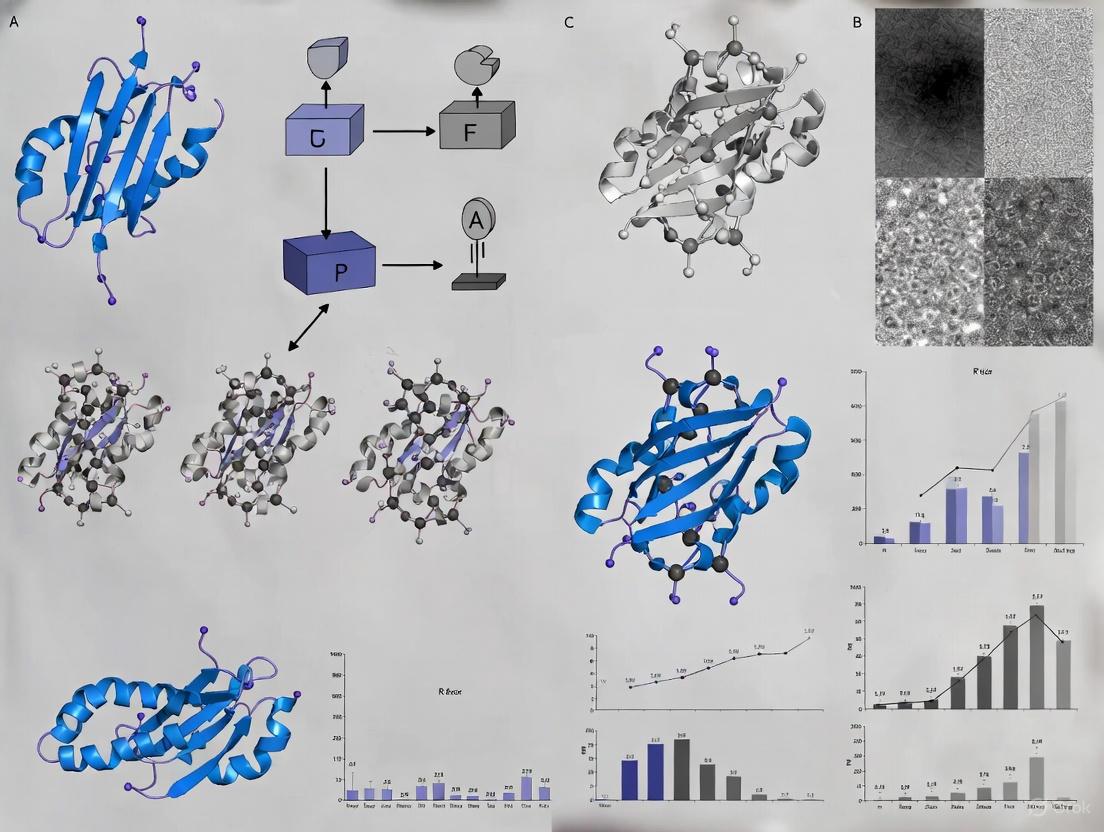

Figure 1: X-ray Crystallography Workflow

Protein Production and Crystallization

The process begins with the production of a homogeneous, stable protein sample. Typically, 5 mg of protein at around 10 mg/mL is a good starting point for crystallization screens [9]. The protein must be purified to homogeneity, as impurities can prevent crystal formation. Stability is crucial because the sample may be incubated with crystallization cocktails for days or weeks before nucleation occurs [9].

Crystallization is often the most significant hurdle. The goal is to slowly bring the protein out of solution in a controlled manner that promotes the formation of a ordered crystal lattice rather than amorphous precipitate. This involves screening a wide range of variables including precipitant type, buffer, pH, protein concentration, temperature, and additives [9]. For particularly challenging targets like membrane proteins, specialized methods such as lipidic cubic phase (LCP) crystallization have been developed to provide a more stable, membrane-mimetic environment [9].

Data Collection and Processing

Once a diffraction-quality crystal is obtained, it is exposed to a high-energy X-ray beam, traditionally at a synchrotron source. When X-rays interact with the electrons in the crystal, they are scattered, producing a diffraction pattern of spots on a detector [9]. The positions and intensities of these spots are recorded.

The diffraction patterns are then processed through indexing, integration, and scaling to produce a set of structure factors that describe the amplitude of each diffracted beam [9]. A critical challenge in crystallography is the "phase problem"—while the amplitudes can be measured directly from the diffraction spots, the phase information is lost during data collection. This phase information must be recovered to calculate an electron density map.

Phase Determination and Model Building

Solving the phase problem is a pivotal step. The most common method is molecular replacement, which searches the data with a known structure that is highly similar to the target [9]. If no suitable model exists, experimental phasing methods are required, such as:

- Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD) or Multiple-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD): These techniques utilize the different scattering properties of specific atoms (often selenium in selenomethionine-labeled proteins or metals) by tuning the X-ray wavelength to their absorption edge [8] [9].

Once initial phases are obtained, an electron density map is calculated. Researchers then build an atomic model into this map, iteratively refining the model to improve the agreement with the observed diffraction data while satisfying standard chemical constraints for bond lengths and angles [9].

Validation of X-ray Structures

The validation of a protein structure derived from X-ray crystallography is a critical process to ensure the integrity and reliability of the model. This involves multiple computational checks against both the experimental data and prior knowledge of molecular geometry.

Key Validation Metrics and Protocols

Validation protocols assess the model's agreement with the experimental data and its stereochemical quality. Key metrics include [11]:

- R-factor and R-free: The R-factor measures the agreement between the model and the observed diffraction data. R-free is calculated using a small subset of reflections not used during refinement and is a crucial indicator for overfitting; a large gap between R-factor and R-free suggests potential problems [11] [12].

- Ramachandran Plot: Analyzes the torsion angles of the protein backbone, identifying residues in allowed, generously allowed, and disallowed regions. A well-refined structure typically has over 90% of residues in the most favored regions [12].

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of Bond Lengths and Angles: Quantifies how much the model's geometry deviates from ideal values.

- MolProbity Clashscore: Identifies steric overlaps between atoms that are too close [11].

- Real-Space Correlation Coefficient: Assesses the fit of the model to the electron density map on a per-residue basis.

Advanced Refinement for Low-Resolution Data

A significant challenge arises when crystals diffract to low resolution (worse than ~3.5 Å), which is common for large, flexible complexes. Traditional refinement methods struggle as the amount of experimental data per model parameter decreases. To address this, advanced methods like the Deformable Elastic Network (DEN) have been developed [12].

The DEN protocol incorporates information from known homologous structures (reference models) but allows for global and local deformations. It uses a combination of target functions during refinement [12]:

F_total = F_data + w_geometry * F_geometry + w_DEN * F_DEN

Where F_data is the fit to the X-ray data, F_geometry enforces standard bond geometry, and F_DEN is the DEN potential that guides the model toward plausible conformations based on the reference model. The weights w_geometry and w_DEN are optimized using R-free [12]. This method can achieve "super-resolution," where the coordinate accuracy is better than the nominal resolution of the data, leading to dramatically improved model quality and electron density maps at resolutions of 3.5-5.0 Å [12].

Figure 2: Validation & Refinement Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful structure determination relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. Table 2 details key solutions and their functions in the crystallography pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for X-ray Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Protein | The macromolecule for structure determination; requires high homogeneity and stability. | Typically 5 mg at ~10 mg/mL for initial screens; buffer exchange may be needed to remove interfering agents like phosphates [9]. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Sparse-matrix screens to identify initial crystallization conditions by sampling diverse chemical space. | Commercial screens (e.g., from Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions) systematically vary precipitant, pH, and salt. |

| Se-Selenomethionine | Used to create selenomethionine-derived protein for experimental phasing via SAD/MAD. | Incorporated via recombinant expression in methionine auxotroph E. coli; provides strong anomalous signal [9]. |

| Heavy Atom Soaks | Salts containing atoms like Hg, Pt, Au, or Pb used for experimental phasing (MIR/SIRAS). | Soaked into pre-grown crystals; must not disrupt crystal lattice [9]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) to prevent ice crystal formation during cryo-cooling. | Soaked with crystal prior to flash-cooling in liquid N₂; essential for data collection at synchrotrons. |

| Detergents/Membrane Mimetics | For solubilizing and crystallizing membrane proteins (e.g., GPCRs, transporters). | Creates a stable hydrophobic environment; LCP (lipidic cubic phase) is a common matrix for crystallization [9]. |

| Synchrotron Beam Time | Access to high-brilliance X-ray sources for data collection. | A limited resource; proposals are typically peer-reviewed. Essential for challenging, small, or weakly diffracting crystals. |

X-ray crystallography maintains its status as the dominant technique in structural biology, a position earned through its unparalleled ability to provide high-resolution, atomic-level structures of biological macromolecules at a high throughput. While cryo-EM has emerged as a powerful complementary technique for very large complexes, and NMR provides unique dynamic information, crystallography remains the workhorse for the drug discovery industry and academic research, as evidenced by its continued majority contribution to the PDB.

The future of crystallography lies in its continued evolution. Techniques like serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and serial millisecond crystallography (SMX) at synchrotrons are pushing the boundaries, enabling the study of microcrystals and the capture of reaction intermediates in real time [10]. Furthermore, advanced refinement and validation methods, such as DEN refinement, are increasing the accuracy and applicability of structures determined from lower-resolution diffraction data [12]. In the context of structural validation, the extensive repository of high-quality crystallographic structures provides an indispensable benchmark for validating and improving computational predictions, ensuring that X-ray crystallography will remain the foundational pillar of structural biology for the foreseeable future.

The determination of atomic-level protein structures is a cornerstone of modern structural biology and drug discovery. X-ray crystallography remains one of the most prominent techniques for achieving this, relying on the interpretation of electron density maps to build and validate atomic models. These maps, generated from X-ray diffraction patterns, provide a continuous function of electron intensity values in three-dimensional space, representing the electron cloud around each atom of the protein and its ligands [3]. The core challenge lies in the accurate transformation of this experimental density data into a reliable atomic model—a process that is both scientifically complex and critical for the integrity of structural science.

This process is particularly vital for applications in drug development, where the precise geometry of a protein-ligand interaction can guide the optimization of therapeutic compounds. The inherent flexibility of proteins means they exist as an ensemble of states, and electron density maps can capture information about major and minor conformations that might be lost in a single, static deposited model [13]. The quality of this interpretation depends on both the resolution of the experimental data and the methodologies used for model building and refinement. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the core principles, computational tools, and validation methodologies that underpin the journey from electron density maps to atomic models, offering researchers a framework for assessing and selecting the most appropriate strategies for their work.

Fundamental Principles of Electron Density Map Interpretation

The Relationship Between Experimental Data and Atomic Models

An electron density map, denoted as ρ(x,y,z), is the primary experimental result of an X-ray crystallography experiment. It is measured in electrons per cubic angstrom (eÅ⁻³) and visualized as a mesh-like network contoured at specific sigma (σ) levels to highlight regions where atoms are located [3]. The map is not directly atomistic; instead, it presents a continuous distribution where atomic positions must be inferred. The most common maps used for model building are the 2Fo-Fc map, which shows the density for the current model, and the Fo-Fc difference map, which highlights features not yet accounted for in the model, such as bound ligands or alternative conformations [14].

The quality of an electron density map is predominantly determined by the resolution of the X-ray data. Higher resolution yields a map where the positions of individual atoms are defined with greater clarity and accuracy. As illustrated in Figure 1, the interpretative power of a map increases dramatically with resolution. At a resolution of 3 Å, the bulky side chain of a tryptophan residue appears as a contiguous blob, making precise atom placement challenging. In contrast, at a resolution of 1.15 Å, the density clearly reveals rings and gaps, allowing for unambiguous positioning of non-hydrogen atoms [15]. This relationship underscores why resolution is one of the most critical parameters for assessing the potential quality of a structural model.

Accounting for Protein Dynamics and Flexibility

Proteins are dynamic systems, and this reality is embedded within their electron density maps. At any point, a protein exists as a collection of major and minor states, and perturbations like ligand binding can reshape the relative populations of these states [13]. Traditional model building often results in a single, static conformation, but the electron density may contain evidence of alternative conformations for side chains and even backbone segments.

Retrospective analyses suggest that up to a third of protein side chains show evidence of minor states in electron-density maps that are not accounted for in the corresponding deposited models [13]. Detecting these areas of flexibility is not just an academic exercise; it can reveal new opportunities for biological insight and technical advances, including the design of selective ligands that exploit conformational dynamics [13]. Therefore, a core principle of modern interpretation is to move beyond a single-conformer model and consider the conformational landscape hidden within the density.

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies and Tools

A range of software tools has been developed to assist researchers in building and refining atomic models into electron density maps. These tools can be broadly categorized into automated model-building suites and specialized utilities for analyzing density and conformational states. The choice of tool often depends on the resolution of the data and the specific biological question.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Software Tools for Model Building and Density Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLEXR-MSA [13] | Electron-density map comparison & multi-conformer modeling | Enables comparison of sequence-diverse proteins via Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA); pinpoints low-occupancy features. | Probing structural differences among homologs/isoforms for selective ligand design. |

| qFit [13] | Automated multi-state modeling | Builds comprehensive multi-conformer models to account for flexibility. | Revealing alternative side-chain and backbone conformations in high-resolution data. |

| Ringer [13] | Electron-density sampling | Visualizes side-chain dynamics without modeling bias by sampling density around chi angles. | Identifying rotameric sub-states that may be missed during manual building. |

| Phenix [14] | Comprehensive structure solution | Integrates tools for molecular replacement, automated building, density improvement, and refinement. | Standard pipeline for de novo structure determination and refinement. |

| Coot [13] [14] | Interactive model building & validation | Graphical tool for manual model building, fitting, and real-space refinement into density maps. | Manual model correction, ligand building, and validation. |

| Gemmi [3] [14] | Data conversion & manipulation | Library and tools for handling crystallographic data, including format conversion and map generation. | Converting between .cif and .mtz formats; creating CCP4 maps for visualization. |

Workflow for Atomic Model Construction

The process of building an atomic model is iterative and involves several well-defined stages, from data preparation to final validation. The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow, integrating the tools from Table 1.

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing atomic models from electron density maps, highlighting the iterative cycle of building, refinement, and validation.

Quantitative Assessment of Map and Model Quality

The quality of a final atomic model is judged by several quantitative metrics that assess how well the model fits the experimental data and conforms to stereochemical expectations.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Model and Map Validation

| Metric | Description | Ideal Range/Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution [15] | Sharpness of the diffraction data. | < 2.5 Å (High), > 3.0 Å (Low) | Defines the interpretable detail in an electron density map. |

| R-factor / Rwork [15] | How well the model fits the experimental data used in refinement. | 14-25% for proteins | Lower values indicate a better fit. |

| Rfree [15] | How well the model fits a subset of data not used in refinement. | Should be close to Rwork (e.g., < 5% higher) | Guards against over-fitting. |

| Ramachandran Outliers [15] | Percentage of residues in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot. | < 1% | Measures the backbone torsion angle sanity. |

| Clashscore [15] | Number of serious steric overlaps per 1000 atoms. | As low as possible | Measures the packing quality and steric strain. |

| B-factors (Temperature) [15] | Measure of atomic displacement/vibration. | Lower average values | High values may indicate disorder or flexibility. |

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Comparative Analysis with FLEXR-MSA

The FLEXR-MSA tool addresses a significant limitation in structural biology: the unbiased comparison of electron-density maps from proteins with non-identical sequences, such as different isoforms or homologs [13]. This is crucial for drug discovery when designing selective ligands.

- Data Acquisition: Obtain coordinates and structure factors for the proteins of interest from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The validation reports from the PDB provide the electron density map coefficients (e.g.,

_validation_2fo-fc_map_coef.cif.gz) required for analysis [14]. - Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Perform an MSA for the target proteins. FLEXR-MSA couples this alignment with its electron-density sampling to handle mutations, dissimilar sequences, and misnumbered residues [13].

- Electron-Density Sampling: The tool samples the electron density at equivalent positions across the aligned structures, bypassing potential biases introduced by differences in the deposited models.

- Visualization and Analysis: FLEXR-MSA generates visualizations that chart low-occupancy features and global changes across the protein surface. This can reveal hidden structural differences, such as rearrangements in flexible loops or alternative conformations in binding sites, that are of interest for designing selective ligands [13].

Protocol for Ligand Building and Validation Using Deep Learning

Interpreting the chemical structure of a ligand from its difference density (Fo-Fc map) is a critical task in structural biology and drug discovery. The LigPCDS dataset and associated deep learning models offer a novel, data-driven approach [3].

Dataset Construction (LigPCDS):

- A list of valid ligands is filtered and downloaded from the RCSB PDB.

- The corresponding PDB entries are refined using Dimple software in a standardized procedure without any added ligands. This normalizes data quality and highlights the ligand blob in the Fo-Fc maps.

- The 3D image of each ligand is derived from its Fo-Fc map using Gemmi software, based on the deposited atomic positions.

- These 3D images are converted into point clouds and labeled pointwise using chemical vocabularies based on atoms and their cyclic structural arrangements [3].

Model Training and Validation:

- A stratified dataset from LigPCDS is used to train deep learning models for semantic segmentation of the ligand's 3D representation.

- The models learn to assign labels (e.g., atom type, part of a ring system) to each point in the 3D point cloud.

- Validated models achieve a mean accuracy (mIoU) of up to 77.4% and an F1-score (mF1) of up to 87.0%, demonstrating their ability to reconstitute ligand chemical structures from electron density [3].

Table 3: Key Resources for Electron Density Map Analysis and Model Validation

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Access / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Validation Map Coefficients [14] | Standardized electron density maps for model validation and analysis. | Downloaded from PDB validation reports (files.wwpdb.org). |

| Gemmi [3] [14] | Software library for converting and manipulating crystallographic data formats (e.g., CIF to MTZ, creating CCP4 maps). | gemmi cif2mtz input.cif output.mtz |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3] | Global archive for experimental structural data, including coordinates and structure factors. | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| LigPCDS Dataset [3] | A large-scale dataset of chemically labeled 3D point clouds of protein ligands for training ML models. | 244,226 ligand entries for known and unknown ligand building. |

| EDBench Dataset [16] | A large-scale dataset of molecular electron densities for training machine learning force fields. | 3.3 million molecules with ED data for quantum-aware modeling. |

| BeStSel Server [17] | Web server for analyzing protein secondary structure from Circular Dichroism (CD) spectra, useful for experimental validation. | https://bestsel.elte.hu |

The journey from an electron density map to a validated atomic model is a sophisticated process that balances experimental data with computational and manual interpretation. The core principles of map quality, multi-conformer modeling, and rigorous validation are paramount for producing reliable structures. As the field advances, tools like FLEXR-MSA for comparative analysis and deep learning approaches trained on datasets like LigPCDS are pushing the boundaries, enabling researchers to extract more nuanced information about protein dynamics and ligand binding from electron density. For researchers in drug development, a firm grasp of these principles and the growing toolkit is essential for critically assessing structural models and leveraging them to guide the design of new therapeutic compounds.

Key Historical Challenges and the Evolution of Validation Standards

The determination of protein structures through X-ray crystallography has been a cornerstone of modern biological science and drug discovery. Since the first protein structure was solved, the methodology has evolved from a laborious process taking years to an almost automatic procedure that can be completed in hours, thanks to key technological advances [18]. However, this acceleration has magnified a fundamental challenge: ensuring that deposited structures are accurate, reliable, and biologically relevant. Validation standards have developed in response to historical limitations and errors in structural determination, evolving from basic geometrical checks to sophisticated multi-parameter analyses. In the modern era, where structural models fuel everything from basic biological hypotheses to structure-based drug design, the rigor of these validation standards directly impacts scientific reproducibility and therapeutic development. This guide objectively compares the evolution of these standards, documenting how the field has addressed persistent challenges in validating protein structures derived from X-ray data.

Historical Challenges in X-ray Crystallography

The journey of X-ray crystallography is marked by several persistent challenges that necessitated the development of robust validation protocols.

Fundamental Methodological Limitations

Early X-ray crystallography faced several technical hurdles that impacted structure quality. A primary challenge was the phase problem, which required complex mathematical and experimental solutions like isomorphous replacement to resolve [18]. Furthermore, the technique inherently provides a static, averaged snapshot of a protein's structure, often biased toward the most populous conformation, thereby failing to resolve critical protein dynamics and conformational diversity [19]. Additionally, the requirement for high-quality crystals introduced a selection bias, as the crystallization process often selects for the most homogeneous fraction of a macromolecule. This made it difficult to study chemical heterogeneity, such as post-translational modifications like phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and glycosylation, which are crucial for protein function [19].

Data Quality and Reproducibility Issues

As the number of macromolecular structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) surpassed 100,000, concerns regarding data quality and reproducibility emerged. A significant number of crystal structures deposited in the PDB were found to be of suboptimal quality [19]. A critical issue relevant to drug discovery has been the incorrect identification and modeling of ligands in protein-ligand complexes. Alarmingly, the fit of complex ligands to electron density has not improved over time, potentially due to overreliance on automation in structure determination and limited use of ligand validation tools [19]. Errors in structural models, if undetected, can propagate through the scientific literature and pollute databases used for computational biology and chemistry, leading to erroneous conclusions and irreproducible results.

The Evolution of Validation Standards

The structural biology community has responded to these challenges with a multi-faceted and evolving set of validation standards and practices.

Establishment of Standard Validation Metrics

The recognition of recurring errors led to the formation of expert task forces, which provided recommendations for the validation of structures determined by X-ray crystallography, NMR, and EM [20]. These recommendations now form the backbone of standard validation reports provided upon deposition to the PDB. The key geometric and stereochemical checks that were instituted include:

- Clashscore: Measures how well atoms are packed together, identifying steric overlaps.

- Ramachandran Outliers: Assesses how well backbone dihedral angles conform to sterically allowed regions.

- Side-chain Rotamer Outliers: Evaluates the plausibility of side-chain conformations.

- Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) and Real-Space R-value (RSR): Measures the agreement between the atomic model and the experimental electron density map at a specific location, which is particularly crucial for validating ligand binding [19].

For X-ray structures, cross-validation metrics like R and Rfree are used. The R factor measures the agreement between the experimental diffraction data and data calculated from the final atomic model. Rfree is calculated using a small subset of diffraction data that was excluded from the refinement process, serving as a safeguard against over-fitting [20].

Community-Wide Initiatives and Data Policies

Beyond specific metrics, broader initiatives have been established to ensure data integrity and reusability.

- The Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF): The International Union of Crystallography (IUCr) has promoted CIF, a family of controlled vocabularies and data formats designed to facilitate accurate interchange and archiving of crystallographic data with all relevant experimental metadata [21].

- Mandatory Deposition of Experimental Data: There is a growing push for the mandatory deposition of unmerged intensity data and even raw diffraction images. This practice is critical for making the results of X-ray crystallography wholly reproducible and allows for future reanalysis of the data as methods improve [19].

- Validation Services and Curated Databases: The IUCr sponsors checkCIF, a validation service for structural data. Furthermore, databases like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) for small molecules exemplify the value of rigorous curation, with over 1.3 million validated and curated crystal structures that are fully discoverable and trusted by the research community [22].

The Rise of Integrative and Hybrid Methods

A major evolution in validation philosophy is the shift from relying solely on crystallographic data to using integrative hybrid approaches. Recognizing the limitations of any single technique, researchers now routinely combine data from multiple sources to validate and complement crystal structures.

- NMR and Dynamics: Solution NMR provides information about the dynamics and flexibility of molecules, represented as an ensemble of structures. Incorporating NMR data helps evaluate the flexibility of various regions of a macromolecule, which is critical for examining drug binding and release mechanisms that may be missed in a static crystal structure [19].

- Cross-linking Mass Spectrometry (XL-MS): This technique is invaluable for validating predicted macromolecular complexes and protein-protein interactions, providing experimental constraints that can confirm or refute models generated by computational methods [23].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Cryo-EM structures can be used to validate the overall architecture and quaternary structure of complexes solved by X-ray crystallography, especially in cases where crystal packing may induce conformational artifacts [23].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Techniques

The following tables summarize the key validation methods, their applications, and their performance in addressing historical challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Validation Metrics and Their Evolution

| Validation Metric | Traditional Application & Limitations | Modern Evolution and Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Rfree [20] | Gold standard for crystallographic model fit, guarding against over-fitting. | Remains a mandatory benchmark. Now supplemented by more granular real-space measures. |

| Geometric Checks (Clashscore, Ramachandran) [20] | Basic sanity checks for stereochemical plausibility. | Automated and integrated into deposition pipelines. Used to identify problematic regions for re-refinement. |

| Ligand Validation (RSCC, RSR) [19] | Initially, a major source of error; poorly fitted ligands were common. | Dedicated ligand validation tools (e.g., in MolProbity) are now emphasized, though ligand fit remains a concern. |

| Structure Precision (Ensemble RMSD) [20] | Used for NMR ensembles, but is a measure of precision, not accuracy. | Clearly distinguished from accuracy. A precise ensemble can still be inaccurate. |

| Chemical Shift Comparison (e.g., ANSURR) [20] | Not traditionally used for crystal structure validation. | Emerging as a powerful method to validate solution-state accuracy of NMR structures, providing a new standard. |

Table 2: Analysis of Techniques for Addressing Specific Validation Challenges

| Validation Challenge | Traditional Approach | Modern/Integrative Approach | Relative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand Placement Accuracy | Visual inspection of electron density (Fo-Fc maps). | Quantitative real-space correlation (RSCC) and automated validation reports [19]. | Modern approach is more objective and standardized, reducing subjective interpretation. |

| Protein Dynamics | Inferred from B-factors, which conflate disorder with motion. | Validation against NMR relaxation data or molecular dynamics simulations [19]. | Integrative approach provides direct, experimental insight into dynamics missing from static structures. |

| Multi-chain Complexes | Reliance on crystal packing contacts, which can be non-biological. | Validation with cross-linking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) and cryo-EM maps [23]. | Hybrid methods provide independent evidence for biologically relevant quaternary structures. |

| Overall Accuracy/Quality | R-value, which can be over-fitted. | Rfree, combined with global validation scores and percentile rankings against the PDB [20]. | Modern suite is more robust against over-fitting and provides context for quality assessment. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Methodologies

Validating Ligand Placement with Real-Space Correlation

Objective: To quantitatively assess the accuracy of a ligand's fit within its electron density map, moving beyond subjective visual inspection. Protocol:

- Generate Electron Density Maps: Using the refined structure model and deposited structure factors, calculate both the

2Fo-Fc(observed) andFo-Fc(difference) maps. - Isolate the Ligand: Within a molecular graphics program (e.g., Coot [19] or PyMOL), select the ligand and any residues within a 5 Å radius.

- Calculate Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC): Use validation software (e.g., MolProbity or Phenix) to compute the RSCC for the ligand. This calculation correlates the electron density values in the

2Fo-Fcmap at every point in the grid with the density calculated from the atomic model. - Interpretation: An RSCC value of >0.9 typically indicates an excellent fit. Values between 0.8 and 0.9 suggest a acceptable but potentially poorly ordered ligand. Values below 0.8 indicate a poor fit, where the model may be incorrect or the ligand is highly disordered [19].

The ANSURR Method for NMR Structure Validation

Objective: To provide an independent measure of NMR structure accuracy by comparing backbone rigidity derived from chemical shifts with rigidity computed from the structure itself [20]. Protocol:

- Input Data Acquisition: Obtain the protein's backbone chemical shift assignments (HN, 15N, 13Cα, 13Cβ, Hα, C′) and the coordinate file of the NMR structure ensemble.

- Predict Rigidity from Shifts (RCI): Use the Random Coil Index (RCI) algorithm to calculate order parameters (S²) for each residue based on the deviation of its chemical shifts from random coil values. This provides an experimental measure of local backbone flexibility.

- Compute Rigidity from Structure (FIRST): Use the Floppy Inclusions and Rigid Substructure Topography (FIRST) software, which applies mathematical rigidity theory to the atomic coordinates. FIRST performs a rigid cluster decomposition, quantifying the probability that each residue is flexible based on the network of covalent and non-covalent constraints.

- Correlation and Scoring: Calculate two scores by comparing the RCI and FIRST outputs: a correlation score (to verify secondary structure placement) and an RMSD score (to measure overall rigidity). The results are presented as percentiles relative to a reference set of NMR structures in the PDB.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

Evolution of Crystallographic Validation

Integrative Validation Workflow

Table 3: Key Software and Database Resources for Structure Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Validation | Relevance | | :--- | | :--- | :--- | | MolProbity [19] | Software | Provides all-atom contact analysis, clashscores, and Ramachandran and rotamer outlier checks. | Industry standard for comprehensive geometric validation. | | Phenix [19] | Software Suite | Includes automated tools for crystallographic structure refinement, validation, and ligand fitting. | Essential for integrated refinement and validation during model building. | | Coot [19] | Software | Interactive model-building tool with built-in validation and real-space refinement capabilities. | Crucial for manual inspection and correction of models based on electron density. | | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository for 3D structural data. Provides mandatory validation reports for every deposit. | Central resource for accessing structures and their associated quality metrics. | | Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [22] | Database | Curated repository of over 1.3 million small molecule organic crystal structures. | Provides reference data for ideal ligand geometry and intermolecular interactions. | | CheckCIF [21] | Web Service | IUCr-sponsored validation service for structural data, particularly for small-molecule crystallography. | Ensures adherence to community standards prior to publication. |

| Reagent/Material | Function in X-ray Crystallography |

|---|---|

| Purified Protein | The target macromolecule (e.g., protein, nucleic acid) must be highly pure and homogeneous to facilitate crystallization [9]. |

| Crystallization Screens | Commercial kits containing a wide range of chemical conditions (precipitants, buffers, salts) to identify initial conditions for crystal growth [9]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Chemicals (e.g., glycerol, ethylene glycol) used to protect crystals from ice formation during flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen for data collection [24]. |

| Heavy Atoms | Elements (e.g., Selenium in Se-Met, or gold/platinum salts) used for experimental phasing by creating derivatives for SAD/MAD methods [9]. |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | A membrane-mimetic environment used for crystallizing challenging integral membrane proteins like GPCRs [9]. |

Understanding the Impact on Drug Design and Basic Research

The determination of three-dimensional protein structures is a cornerstone of modern biology and drug discovery, providing an atomic-level blueprint for understanding function and designing interventions. Among the experimental techniques available, X-ray crystallography has been, and continues to be, a dominant force. As of September 2024, it accounts for approximately 84% of the total structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [9]. This guide provides a comparative overview of X-ray crystallography against other primary structural biology methods—Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)—focusing on their workflows, outputs, and specific impacts on drug design and basic research. Within the critical context of protein structure validation, we will explore how the quantitative metrics derived from X-ray crystallography not only assess model quality but also underpin the reliability of structures used to make pivotal scientific and therapeutic decisions.

Experimental Protocols in X-ray Crystallography

The journey to a protein structure via X-ray crystallography is a multi-stage process where each step is critical for the success of the next. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages from protein preparation to a refined model.

Detailed Methodologies

Protein Crystallization: The purified protein is concentrated and subjected to screens that vary precipitant, buffer, pH, and temperature to find conditions that yield well-ordered, three-dimensional crystals. This step is often the major bottleneck, especially for membrane proteins, which require mimetic environments like the Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) [9].

Data Collection and Processing: A crystal is exposed to a high-energy X-ray beam, producing a diffraction pattern. The Arndt-Wonacott rotation method is the standard, where the crystal is rotated through the beam while collecting hundreds to thousands of images on an area detector [24]. Software packages like XDS, HKL-2000, and MOSFLM are then used for autoindexing, integrating, and scaling the diffraction spots into a set of structure factor amplitudes [24].

Phase Determination and Model Building: The "phase problem" is solved using methods like Molecular Replacement (MR), which uses a known homologous structure, or experimental phasing (e.g., SAD/MAD), which requires the incorporation of heavy atoms [9]. An initial atomic model is built into the experimental electron density map and iteratively refined to improve the fit to the data while maintaining realistic geometry [15].

Key Validation Metrics for X-ray Structures

Validating an X-ray crystal structure is paramount to ensuring its reliability for downstream interpretation. The quality of a structure is assessed using a suite of complementary metrics, which are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics for X-ray Crystallography

| Metric | Definition | Ideal Value/Range | Significance in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | The smallest distance between lattice planes that can be resolved [15]. | As low (high-resolution) as possible (e.g., <2.0 Å). | Higher resolution provides a clearer, more detailed electron density map, allowing for more accurate atomic placement [15]. |

| R-factor (R-work) | Measures the agreement between the observed diffraction data (Fobs) and the data calculated from the model (Fcalc) [25]. | Should be as low as possible. Typically ~14-25% for proteins [15]. | A lower R-work indicates the model better explains the experimental data. Can be artificially improved by overfitting [26]. |

| Free R-factor (R-free) | Calculated the same as R-work, but using a small subset (~5-10%) of data excluded from refinement [25]. | Should be close to R-work (typically 0.02-0.05 higher) [25]. | A key guard against overfitting. A large gap between R-work and R-free suggests the model may not be trustworthy [26] [25]. |

| Ramachandran Outliers | Percentage of amino acid residues with dihedral angles in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot [15]. | As low as possible (e.g., <0.5% for a high-quality structure). | Indicates the stereochemical quality of the protein backbone. A high percentage suggests poor model geometry [15]. |

| Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) | For ligands, measures the correlation between the model's electron density and the experimental density [25]. | >0.90 is acceptable; closer to 1.0 is ideal [25]. | Critical for validating the placement and identity of bound drugs, inhibitors, or cofactors in drug design [25]. |

It is crucial to be aware that these metrics can be manipulated. For instance, truncating a dataset by discarding weak high-resolution data can artificially improve R-work and R-free values, giving a false impression of quality at the expense of actual structural detail [26]. Therefore, resolution should be assessed where the signal-to-noise ratio (I/σ(I)) falls to approximately 1.0-2.0 in the outermost shell [26].

Comparative Analysis with NMR and Cryo-EM

The choice of structural technique depends on the biological question, the properties of the target macromolecule, and the desired information. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the three main techniques.

Table 2: Technique Comparison: X-ray Crystallography, NMR, and Cryo-EM

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | NMR Spectroscopy | Cryo-EM (Single Particle) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sample State | Crystalline solid | Solution in a tube | Vitreous ice on a grid |

| Sample Requirements | High purity, must crystallize (~5 mg at 10 mg/ml) [9]. | High purity, requires isotope labeling (~0.5 ml at >200 µM) [9]. | High purity, requires particle homogeneity and stability. |

| Size Applicability | No strict limit, but larger complexes are harder to crystallize [9]. | Best for smaller proteins (<~40 kDa) [27]. | Ideal for large complexes (>~50 kDa) [9]. |

| Key Output | Single, static atomic model. | Ensemble of models representing dynamics in solution. | 3D density map and atomic model. |

| Resolution Range | Atomic (~1.0 - 3.5 Å) | Atomic (~1.0 - 3.5 Å for distances) | Near-atomic to atomic (~1.5 - 5.0+ Å) |

| Strengths | High-throughput; Atomic resolution; Supports fragment-based drug discovery; Mature and automated workflows [9]. | Studies dynamics and flexibility; No crystallization needed; Provides information on interactions [9]. | No crystallization needed; Handles large, flexible complexes; Can capture multiple states [27]. |

| Limitations | Crystallization is a major hurdle; Static picture of a single conformation; Crystal packing artifacts are possible [9]. | Low-throughput; Limited by molecular size; Complex data analysis [9]. | Lower throughput than X-ray; Requires substantial data collection and computing [28]. |

Impact on Drug Design and Basic Research

Direct Applications in Drug Discovery

X-ray crystallography has an unparalleled track record in rational drug design. By visualizing a drug candidate bound to its protein target, researchers can:

- Guide Lead Optimization: Atomic-level details of protein-ligand interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and water-mediated networks) allow medicinal chemists to systematically modify lead compounds to enhance potency, selectivity, and metabolic stability [9]. A prime example is the development of HIV protease inhibitors and the SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitor, Nirmatrelvir, where crystallography was instrumental in defining the active site and guiding inhibitor design [27].

- Enable Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD): X-ray crystallography is a powerful method for screening libraries of small molecular fragments. Soaking fragments into crystals can identify weak binding events in specific pockets, providing starting points for growing larger, more potent drug molecules [9].

Contributions to Basic Research

Beyond direct drug design, the structures solved by X-ray crystallography form the foundation of our molecular understanding of biology.

- Elucidation of Enzyme Mechanisms: Structures of enzymes trapped with substrates, intermediates, or transition-state analogs have revealed the chemical underpinnings of catalysis for countless biological reactions [27].

- Understanding Macromolecular Complexes: From the ribosome to viruses, X-ray structures have provided breathtaking insights into the assembly and function of complex cellular machines [27].

- A Foundation for AI Prediction: The vast repository of high-quality experimental structures in the PDB, predominantly from X-ray crystallography, served as the essential training data for AI prediction tools like AlphaFold [9]. While these tools are revolutionary, they are not a replacement for experimental data, especially for questions involving mechanisms, protein-ligand interactions, and conformational changes [9].

X-ray crystallography remains a powerful and indispensable tool in the structural biologist's arsenal. Its ability to provide high-resolution, atomic-level structures has fundamentally shaped our understanding of biological processes and continues to be a critical driver in rational drug design. While techniques like Cryo-EM are rapidly advancing and excel at solving structures of large complexes that defy crystallization, the high-throughput capacity and atomic precision of X-ray crystallography secure its enduring role. For the researcher, a critical understanding of both its robust experimental workflow and, just as importantly, the proper interpretation of its validation metrics is essential for leveraging X-ray structures to push the boundaries of science and medicine.

A Practical Workflow for Protein Structure Validation and Quality Assessment

Validating three-dimensional protein structures determined by X-ray crystallography is a foundational step in structural biology and rational drug design. The reliability of a structural model directly impacts subsequent research, from understanding enzyme mechanisms to designing small-molecule inhibitors. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the essential metrics—resolution, R-factor, and R-free—used by researchers to objectively assess the quality of crystallographic models. We frame this discussion within the broader thesis that robust validation is not merely a procedural step but a critical practice that determines the veracity of structural insights derived from X-ray data. For the practicing scientist, understanding the interplay and limitations of these metrics is paramount when selecting a protein structure from the PDB for detailed analysis or as a basis for experimental design [15].

Metric Definitions and Core Principles

Resolution

The resolution of a crystallographic dataset, reported in Angstroms (Å), is the single most important parameter determining the level of detail observable in an electron density map [15]. It is a measure of the quality of the diffraction data and the order of the crystal. In practical terms, resolution limits the minimum distance at which two features can be distinguished as separate.

- High-resolution structures (≤ 1.5 Å): At this level of detail, electron density maps are highly defined, allowing for the unambiguous placement of individual atoms, the discernment of alternate side-chain conformations, and the precise location of ordered water molecules and ions [29].

- Medium-resolution structures (1.5 - 2.5 Å): The overall protein chain tracing is clear, and the conformations of most side chains can be modeled. However, finer details may be less distinct [15].

- Low-resolution structures (≥ 3.0 Å): Only the basic contours of the protein chain are visible. The atomic structure must be inferred, and the placement of individual atoms and side chains becomes ambiguous [29].

The resolution is typically defined by the highest-resolution shell of data where the signal-to-noise ratio, expressed as <I/σ(I)>, falls to a specific value, often around 1.0 to 2.0 [26]. It is crucial to note that some data sets may be artificially truncated at a high <I/σ(I)> to improve apparent R-factor statistics, a practice that discards valuable, albeit weaker, high-resolution data and can trap the model in a local minimum during refinement [26].

R-factor (R-work)

The R-factor (or R-work) is a measure of the global agreement between the crystallographic model and the experimental X-ray diffraction data [30]. It quantifies the disagreement between the observed structure-factor amplitudes (F_obs) and those calculated from the atomic model (F_calc). The standard crystallographic R-factor is defined by the formula:

[R = \frac{\sum{||F{\text{obs}}| - |F{\text{calc}}||}}{\sum{|F_{\text{obs}}|}}]( [30]

A value of 0 represents a perfect fit, while a totally random set of atoms gives an R-value of about 0.63 [29]. For protein structures, typical R-work values range from about 0.14 (14%) to 0.25 (25%), with lower values indicating better agreement [15] [29]. The R-factor can be artificially improved by overfitting the model to the specific dataset used in refinement, adjusting it to match noise or minor fluctuations rather than the true underlying structure [25].

R-free

The free R-factor (R-free) was introduced as a cross-validation tool to guard against overfitting [25]. Before refinement begins, a small subset of the experimental diffraction data (typically 5-10%) is randomly selected and set aside, never used during any step of the model building or refinement process [25] [29]. The R-free is then calculated by comparing the model's predicted structure-factor amplitudes to this completely unused "test set."

R-free provides a less biased measure of the model's predictive power. For a well-refined model that has not been overfitted, the R-free value will be similar to the R-work value, typically only slightly higher (by approximately 0.02 to 0.05) [25]. A significant gap between R-work and R-free is a classic indicator of overfitting or other problems with the model [25] [26]. It is important to note that R-free values can also be manipulated, for example, by strategically excluding weak, high-resolution reflections from the test set, thereby artificially improving the statistic [26].

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

The table below provides a qualitative comparison of the three core validation metrics, highlighting what each measures, its strengths, and its key limitations.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparison of Core Crystallographic Validation Metrics

| Metric | What It Measures | Key Strengths | Key Limitations & Vulnerabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | The fineness of detail in the experimental diffraction data; the resolvability of features. | Single most important indicator of potential model accuracy [15]. Intuitive link to interpretability of electron density. | Does not directly report on model quality. Can be misleading if data is truncated [26]. |

| R-factor (R-work) | Global fit of the atomic model to the entire dataset used for refinement. | Standardized, widely reported metric for model-to-data agreement. | Highly susceptible to overfitting; can be improved by adding unjustified parameters [25]. |

| R-free | Predictive power of the model against a subset of data not used in refinement. | Essential guard against overfitting; provides unbiased validation [25] [29]. | Requires withholding data, reducing refinement power. Can be manipulated via data selection [26]. |

To provide quantitative guidance, the following table summarizes the typical interpretations of these metrics across different resolution ranges for protein structures.

Table 2: Typical Values and Interpretation for Protein Structures at Different Resolutions

| Resolution Range | Typical R-work / R-free Values | Expected Model Detail & Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High (≤ 1.5 Å) | ~14-20% / ~16-22% | Individual atoms resolved. Accurate placement of side-chains, water networks, and ions. High confidence in geometry [15]. |

| Medium (1.5 - 2.5 Å) | ~18-23% / ~21-26% | Clear protein backbone and most side-chain conformations. Some flexibility in surface loops. Standard validation (Ramachandran, clashscore) is critical. |

| Low (≥ 3.0 Å) | ~22-28% / ~26-32%+ | Only backbone trace is reliable. Side-chain placement often ambiguous. High risk of errors; requires cautious interpretation [15] [29]. |

The interplay between these metrics is crucial for a holistic assessment. A high-resolution structure with a poor R-free may be less reliable than a medium-resolution structure with excellent R-work/R-free agreement. The relationship between data, model building, and validation is a cyclical process of improvement, which can be visualized in the following workflow.

Diagram 1: Crystallographic Structure Determination and Validation Workflow. The workflow highlights the critical role of the R-free test set, which is excluded from refinement to provide unbiased validation.

Advanced Metrics and Complementary Validation

Beyond the three core metrics, a thorough structure validation requires assessing the model in real space (i.e., directly in the electron density map) and its geometric rationality.

Real-Space Fit Metrics for Ligands and Residues

For specific parts of the model, such as bound ligands or individual amino acid residues, the real-space fit is critically important.

- Real-Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC): Measures the correlation between the electron density calculated from the model and the experimental electron density in a specific region. A value closer to 1.0 indicates a very good fit. Values around or below 0.80 suggest the experimental data does not strongly support the modeled conformation [25].

- Real-Space R-value (RSR): Measures the disagreement between the observed and calculated electron densities for a specific atom or group. Lower values indicate better agreement, with values approaching or above 0.4 typically suggesting a poor fit [25].

- RSRZ Outliers: The RSR Z-score (RSRZ) is a normalization of the RSR specific to a residue type and resolution. A residue is considered an outlier if its RSRZ value is greater than 2. The global percentage of RSRZ outliers indicates the proportion of the model that fits the electron density poorly [25].

Model Geometry and the Ramachandran Plot

The geometric quality of the protein model is a key internal check. While bond lengths and angles are heavily restrained during refinement, the Ramachandran plot is one of the most sensitive indicators of overall model quality [15]. This plot shows the dihedral angles (Phi and Psi) of each amino acid residue in the protein backbone.

- A high-quality, well-refined model will have over 95% of its residues in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot, with few or no outliers in the disallowed regions [15].

- A poorly refined model will have a significant percentage of residues in additionally allowed and disallowed regions, signaling potential errors in the backbone conformation [15].

The relationship between a model's geometric quality and its resolution can be complex, but high-resolution structures generally provide the data needed to achieve superior geometry.

Experimental Protocols and Data Integrity

Standard Refinement and Cross-Validation Protocol

The internationally accepted best practice for crystallographic refinement involves a strict separation of data for refinement and validation [25] [29].

- Data Set Selection: Upon completing data integration, a random 5-10% of the unique reflection data is selected and designated as the "test set." These reflections are immediately excluded from all subsequent refinement and model-building steps.

- Iterative Refinement: The atomic model is built and refined against the remaining 90-95% of the data (the "working set"). This process involves cycles of manual model adjustment in a graphics program and computational refinement to optimize parameters.

- Cross-Validation: After each refinement cycle, the R-free is computed using the test set. This value is monitored to ensure the model's predictive power is improving alongside the R-work.

- Completion: Refinement is considered complete when the model is chemically sensible, fits the electron density well, and the R-work and R-free values have converged to a stable, minimal gap (typically ≤ 0.05).

Quantifying Systematic Errors and Potential Pitfalls

Recent research highlights that traditional metrics can be vulnerable to statistical manipulation, necessitating a critical eye [26] [31].

- The Dangers of Data Truncation: A common practice to artificially lower R-factor and R-free values is to truncate the high-resolution data at a shell where

<I/σ(I)>is still high (e.g., 2.0 or 3.0), rather than using all available data to the point where<I/σ(I)>falls to 1.0 [26]. This trades a genuine improvement in resolution for a deceptively better R-factor statistic, potentially resulting in a less accurate model trapped in a local minimum. - Goodness-of-Fit and Explanatory Power: To counter this, a global goodness-of-fit metric that considers the explanatory power of the data has been proposed. This metric, related to the observation-to-atoms (O2A) ratio, is defined as

R_O2A / R_work. It encourages the use of all available data by rewarding a high ratio of experimental observations (reflections) to the number of model parameters (non-hydrogen atoms) [26]. A structure with a slightly higher R-free but a much higher O2A ratio may be superior to one with a low R-free but a low O2A ratio. - Quantifying Systematic Error Costs: In small-molecule crystallography, metrics have been developed to quantify the increase in the weighted agreement factor directly attributable to systematic errors. Studies applying this to hundreds of published datasets suggest that systematic errors can increase the weighted agreement factor by a factor of 3 or more in 50% of cases, underscoring that inaccuracies are not unique to macromolecular crystallography [31].

The following table lists key resources and tools used by researchers for protein structure determination, refinement, and validation.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Resources in Structural Biology

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Primary source for retrieving structural models and their associated validation reports and metrics [15]. |

| checkCIF / IUCr | Validation Service | Online service that performs a battery of checks on crystallographic data before publication. | Automated check for consistency and quality, identifying geometric outliers and other potential issues [32]. |

| Coot | Software | Molecular graphics application for model building and validation. | Used to fit atomic models into electron density maps and analyze real-space fit (RSCC, RSR) for individual residues and ligands. |

| PHENIX / Refmac | Software | Comprehensive suites for the automated crystallographic structure solution and refinement. | Perform computational refinement against the working set and automatically calculate R-work and R-free after each cycle. |

| Selenomethionine | Chemical Reagent | Selenium-containing methionine analog used in protein expression. | Used for experimental phasing via anomalous scattering (SAD/MAD), which is crucial for solving novel structures [29]. |

| Synchrotron Beamline | Facility | Source of high-intensity, tunable X-ray radiation. | Enables data collection from weakly diffracting crystals, often to higher resolution, which is fundamental for obtaining high-quality data [33]. |

Interpreting B-factors (Temperature Factors) for Flexibility and Disorder

The B-factor, formally known as the atomic displacement parameter, serves as a fundamental metric in structural biology for quantifying atomic positional variability within macromolecular structures determined by X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Mathematically defined as B = 8π²u², where u represents the root-mean-square displacement of an atom from its equilibrium position, this parameter provides crucial insights into protein dynamics and disorder [34]. In practice, B-factors have found diverse applications across structural biology, from identifying thermal motion pathways and correlating with amino acid rotameric states to guiding protein engineering efforts for enhanced thermostability in industrial enzymes [35].

Despite their utility, B-factors present a significant interpretive challenge for researchers, as they constitute a composite signal influenced by multiple factors beyond local atomic mobility. These parameters incorporate contributions from conformational disorder, crystal defects, large-scale disorder, data quality, and refinement methodologies [36] [34]. This complexity creates an inherent "non-transferability" between structures, where B-factor values for identical atoms can vary substantially across different determinations of the same protein [34]. Within the framework of protein structure validation, recognizing both the informational value and limitations of B-factors becomes essential for proper structural interpretation and avoidance of over-interpretation, particularly for regions exhibiting elevated values [35].

Quantitative Foundations: Accuracy and Limits of B-factor Interpretation

Experimental Accuracy of B-factors

The fundamental accuracy of B-factors in protein structures has been systematically evaluated through comparative analyses of multiple independent determinations of the same protein. A landmark 2022 study examining over 400 crystal structures of Gallus gallus lysozyme revealed that B-factor errors remain substantial, approximately 9 Ų for ambient-temperature structures and 6 Ų for low-temperature (∼100 K) structures [36]. These values strikingly resemble estimates reported two decades prior, indicating limited progress in improving B-factor accuracy despite advances in other aspects of structure determination [36]. This inherent imprecision necessitates caution when interpreting small B-factor differences and underscores the importance of normalization procedures when comparing different structures [36] [34].

Table 1: Experimentally Determined B-factor Accuracies

| Structure Type | Temperature | Estimated Error (Ų) | Basis of Estimation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein crystal structure | Ambient (280-300 K) | ~9 Ų | Comparison of identical atoms in multiple lysozyme structures [36] |

| Protein crystal structure | Low temperature (90-110 K) | ~6 Ų | Comparison of identical atoms in multiple lysozyme structures [36] |

Physically Meaningful B-factor Ranges