Protein X-Ray Crystallography: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to protein X-ray crystallography, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Protein X-Ray Crystallography: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to protein X-ray crystallography, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of the technique, from protein crystallization and the phase problem to data collection. The scope extends to detailed methodological workflows and key applications in structure-based drug design and fragment-based discovery. Furthermore, the article addresses common challenges like growing high-quality crystals and mitigating radiation damage, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it outlines the critical process of structure validation and compares crystallographic data with insights from other methods like NMR, providing a holistic view for critical evaluation of macromolecular structures.

The Foundation of Structural Biology: Core Principles of Protein X-Ray Crystallography

In the field of structural biology, X-ray crystallography remains a cornerstone technique, responsible for determining over 85% of the macromolecular structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1]. The process, however, is entirely dependent on the availability of high-quality crystals, a step that is frequently described as the primary bottleneck in structure determination [2]. This technical guide details the foundational principles and practical methodologies for protein crystallization, framed within the broader context of basic protein X-ray crystallography research. The process of crystallization is, at its core, a controlled precipitation event. It requires the delicate manipulation of a protein solution into a supersaturated state where molecules can spontaneously arrange into a periodic, three-dimensional lattice [1] [2]. Success hinges on a deep understanding of both the biochemical nature of the protein sample and the physical chemistry of crystal nucleation and growth. The following sections provide an in-depth examination of the critical parameters, standard protocols, and key reagents that researchers must master to successfully transition from a purified protein solution to a diffraction-ready crystal.

Fundamental Principles of Protein Crystallization

The Crystallization Phase Diagram

The journey from a soluble protein to a crystal is best understood through the lens of a phase diagram, which maps the protein's behavior under varying concentrations of both protein and precipitant [3] [2]. The diagram is divided into distinct zones:

- Undersaturated Zone: Here, the protein concentration is below its solubility limit. The solution is stable, and no nucleation or crystal growth can occur [2].

- Metastable Zone: In this region, the solution is supersaturated, but the energy barrier for spontaneous nucleation is high. While pre-existing nuclei can grow, new nucleation events are unlikely [2].

- Labile or Nucleation Zone: This zone represents a higher level of supersaturation where the solution is unstable and the probability of spontaneous nucleation is highest. This is the target zone for initial crystal formation [3] [2].

- Precipitation Zone: At very high supersaturation, the protein precipitates out of solution in a disordered, amorphous form, preventing the ordered assembly required for crystal growth [3].

The objective of all crystallization methods is to guide the protein solution from the undersaturated zone into the labile zone to initiate nucleation, and then to maintain conditions in the metastable zone to allow for controlled crystal growth [2].

Key Biochemical Requirements for Crystallization

The quality of the starting protein sample is the single most critical factor for successful crystallization. The following requirements are essential:

- High Purity: Samples must be highly homogeneous, typically >95% pure, as impurities can disrupt the orderly packing of molecules into a crystal lattice [3] [1].

- Structural Homogeneity: The protein must exist in a single, stable conformational state. Sources of heterogeneity include flexible regions, oligomerization, misfolded populations, and post-translational modifications like glycosylation [1].

- Sample Stability: Crystals can take days to months to nucleate and grow. The protein must remain stable and soluble throughout this period. Techniques like differential scanning fluorimetry can be used to identify optimal buffer conditions, pH, and ligands that enhance stability [1].

- Monodispersity: The protein solution should be monodisperse, meaning it consists of uniform particles without aggregation. Techniques such as dynamic light scattering (DLS) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) are used to assess this property [1].

Table: Key Biochemical Properties for Successful Crystallization

| Property | Target | Common Assessment Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | >95% | SDS-PAGE, Mass Spectrometry |

| Structural Homogeneity | Single Conformational State | SEC-MALS, Analytical Ultracentrifugation |

| Stability | Stable for days to months | Differential Scanning Fluorimetry, Circular Dichroism |

| Solubility/Monodispersity | Monodisperse, no aggregation | Dynamic Light Scattering, Size-Exclusion Chromatography |

Core Crystallization Methodologies

Several experimental techniques are employed to achieve the controlled supersaturation required for crystallization. The following are the most widely used protocols in structural biology laboratories.

Vapor Diffusion (Hanging and Sitting Drop)

Vapor diffusion is the most extensively used crystallization method [2]. The principle involves placing a small drop containing a mixture of protein and precipitant solutions in a sealed chamber with a larger reservoir of precipitant solution. Water vapor diffuses from the drop towards the reservoir until the osmolarity of the drop and the reservoir are equal. This slowly concentrates both the protein and the precipitant, ideally driving the solution into the nucleation zone of the phase diagram [3].

Hanging Drop Procedure [3]:

- Fill the wells of a 24-well tray with 500 µL of precipitant solution (reservoir).

- Create a silicone grease ring around the edge of each well.

- Place a clean cover slide on a stable surface.

- Pipette 1-2 µL of concentrated protein solution onto the center of the cover slide.

- Add an equal volume of reservoir solution directly to the protein drop, carefully avoiding bubble formation.

- Gently flip the cover slide and place it over the well, pressing down to form a seal with the grease.

- Place the tray on a shock-absorbing material in a constant-temperature incubator (commonly 20°C) and avoid disturbance.

- Check for crystals regularly over days to months, documenting the results.

Sitting Drop Procedure: The procedure is nearly identical, except the protein-precipitant mixture is dispensed onto a small shelf or bridge that sits above the reservoir solution. The well is then sealed with transparent tape instead of a cover slide and grease [3].

Batch Crystallization under Oil

The batch method relies on bringing the protein directly into the nucleation zone by mixing it with an appropriate amount of precipitant [3]. This is typically performed under a paraffin or mineral oil layer to prevent evaporation of water from the drop [3] [2].

Microbatch Procedure [3]:

- Air-spray a new 96-well microbatch tray to remove dust.

- Fill the wells with paraffin oil to a height of about 3 mm.

- Load 1 µL of concentrated protein solution directly to the bottom of an oil-filled well.

- Load 1 µL of precipitant solution into the same well, ensuring it sinks and fuses with the protein droplet.

- Move to the next well until the tray is complete.

- Follow the same incubation and monitoring procedures as for vapor diffusion.

Advanced and Emerging Techniques

- Liquid-Liquid Diffusion: Also known as counter-diffusion, this technique involves injecting protein and precipitant on opposite sides of a closed channel (e.g., a capillary). The components gradually mix via diffusion, creating a gradient of conditions that can sample the phase diagram and promote crystal growth [2].

- Serial Crystallography: This method, often performed at room temperature, involves merging diffraction data from thousands of microcrystals. It is particularly valuable for capturing protein conformations at near-physiological temperatures and for time-resolved studies [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful crystallization requires careful selection of reagents that modulate protein solubility and promote lattice formation.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Crystallization

| Reagent Category | Function | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants | To reduce protein solubility and drive the solution toward supersaturation [2]. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) 3350, Ammonium sulfate, Sodium chloride, 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) [3] [2] |

| Buffers | To control the pH of the crystallization condition, typically within 1-2 pH units of the protein's pI [1] [2]. | HEPES, Tris hydrochloride, Sodium cacodylate, MES, Sodium acetate [2] |

| Salts | To enhance stability at lower concentrations and compete for water molecules at higher concentrations (salting-out) [1]. | Ammonium sulfate, Sodium chloride, various metal salts [1] |

| Additives | To promote protein stability, solubility, or specific crystal contacts [2]. | Substrates/ligands, metal ions, detergents (for membrane proteins), reducing agents [1] [2] |

| Reducing Agents | To maintain cysteine residues in a reduced state and prevent disulfide-mediated aggregation [1]. | DTT, TCEP (noted for its long solution half-life) [1] |

Optimization and Screening Strategies

Given the empirical nature of crystallization, a systematic approach to screening and optimization is crucial.

- Initial Screening: Sparse matrix incomplete factorial screens are commonly used for initial trials. These screens, available commercially, are biased toward conditions that have been successful for other macromolecules and efficiently sample a wide range of precipitants, salts, and pH levels [3] [5].

- Construct Optimization: If a protein proves difficult to crystallize, the protein itself may be modified. This involves using bioinformatics tools and limited proteolysis to design constructs that remove flexible regions, thereby reducing conformational heterogeneity and improving crystallization propensity [1] [2].

- Iterative Optimization: Modern software platforms, such as ROCK MAKER, can automate the optimization process. For example, Iterative Screen Optimization (ISO) automatically adjusts precipitant concentrations in successive rounds of experiments based on user scores from previous trials, systematically driving conditions toward the nucleation zone [6].

The path from a purified protein to a diffraction-quality crystal is a complex and often challenging endeavor. It demands a rigorous approach to protein biochemistry, a solid understanding of the physical principles of crystallization, and meticulous execution of experimental protocols. While the process remains partly empirical, the strategies outlined in this guide—emphasizing sample quality, systematic screening, and iterative optimization—provide a robust framework for success. Mastering this critical first step of crystallization unlocks the power of X-ray crystallography, enabling researchers to visualize biological macromolecules at atomic resolution and profoundly advancing our understanding of cellular function and drug discovery.

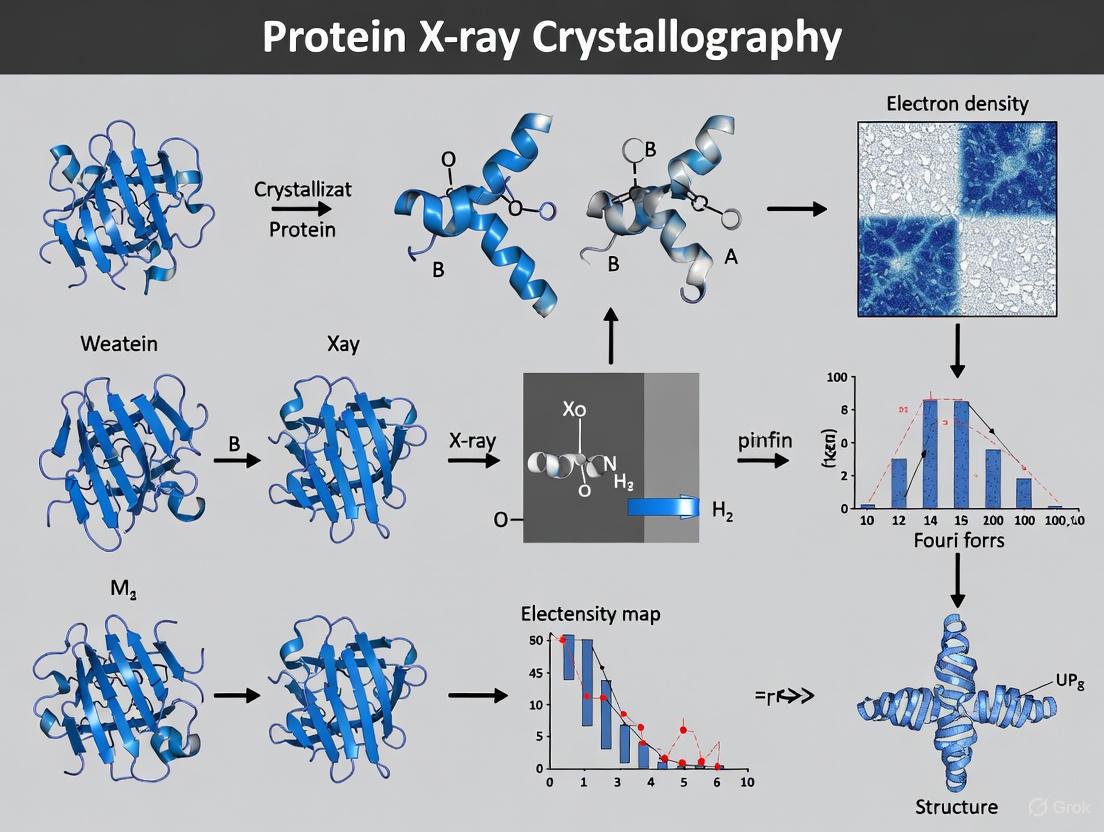

Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

Crystallization Workflow

Phase Diagram Zones

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a powerful non-destructive analytical technique that has revolutionized our understanding of crystalline materials, from simple inorganic compounds to complex biological macromolecules [7]. At its core, XRD exploits the wave nature of X-rays, which have wavelengths (typically 0.1-10 nm) comparable to the interatomic spacing in crystals [7]. When X-rays interact with a crystalline sample, they scatter from the electrons around atoms in the crystal lattice. While most scattered X-rays interfere destructively and cancel each other out, in specific directions determined by the crystal's internal structure, they interfere constructively and reinforce one another, producing detectable diffraction patterns [8]. This phenomenon provides unparalleled insights into the atomic and molecular structure of materials, enabling researchers to determine the precise arrangement of atoms within a crystal [7].

The technique is particularly valuable in structural biology, where it has been instrumental in determining the structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and other biological macromolecules [9]. The diffraction pattern generated during an XRD experiment serves as a unique "fingerprint" for material identification and structural analysis [7]. Unlike many other analytical techniques, XRD is non-destructive, meaning the sample remains intact after analysis, allowing for further investigation if needed [10]. For protein crystallography specifically, XRD provides both qualitative and quantitative information about crystal structure, phase identification, lattice parameters, and molecular geometry [7] [8].

Theoretical Foundation: Bragg's Law and the Diffraction Condition

The fundamental principle governing X-ray diffraction is Bragg's Law, formulated by William Lawrence Bragg in 1913 [7]. This elegant mathematical relationship describes the precise conditions under which constructive interference of X-rays occurs from parallel crystal planes.

Mathematical Formulation

Bragg's Law is expressed by the equation:

nλ = 2d sinθ

Where:

- n = order of diffraction (integer: 1, 2, 3...)

- λ = wavelength of the incident X-ray radiation

- d = interplanar spacing, the perpendicular distance between parallel crystal planes

- θ = Bragg angle, the angle between the incident X-ray beam and the crystal plane [7] [11]

This condition must be satisfied for a diffraction peak to be observed. The path difference between X-rays scattered from adjacent parallel crystal planes must equal an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength for constructive interference to occur [8].

Physical Interpretation

In a crystalline material, atoms are arranged in a regular, repeating pattern forming various sets of parallel planes with characteristic interplanar spacings (d-spacings) [10]. When monochromatic X-rays strike these planes, each atom acts as a scattering center, emitting secondary X-rays with the same frequency as the incident beam [7]. Bragg's Law essentially treats diffraction as a "reflection" of X-rays from these atomic planes, but only at specific angles where the path length difference between waves reflected from successive planes results in constructive interference [8] [12].

The relationship shows that larger interplanar spacings (d) produce diffraction peaks at smaller angles (θ), while smaller spacings produce peaks at larger angles [12]. This inverse relationship enables researchers to calculate unknown interplanar spacings by measuring diffraction angles, forming the basis for crystal structure determination [7].

Table: Key Parameters in Bragg's Law and Their Significance

| Parameter | Symbol | Significance in XRD | Typical Values/Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | λ | Determines resolution capability; defines scale of observable structures | ~1.54 Å (Cu Kα) [7] |

| Interplanar Spacing | d | Reveals distances between atomic planes in crystal | 0.5 - 20 Å [12] |

| Bragg Angle | θ | Angle between incident beam and crystal plane; measured during experiment | 5° - 80° (2θ) [11] |

| Diffraction Order | n | Integer representing harmonic order of diffraction | 1, 2, 3... [7] |

Instrumentation and Data Collection Methods

Modern X-ray diffraction instruments, known as diffractometers, are sophisticated systems designed to precisely control and measure the diffraction phenomenon [7]. While configurations vary depending on the specific application, all diffractometers share fundamental components that work in coordination to produce reliable diffraction data [12].

Core Components of an X-Ray Diffractometer

A typical X-ray diffractometer consists of several essential components:

X-ray Source: Generates monochromatic X-rays through electron bombardment of a metal target. The most common sources use copper (Cu Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å) or molybdenum (Mo Kα, λ = 0.71 Å) targets [7]. Copper radiation is ideal for most routine analyses, while molybdenum radiation is preferred for samples containing heavy elements or when higher resolution is needed [7]. Modern sources include X-ray tubes, rotating anode generators, microfocus tubes, and synchrotron facilities [12].

Incident Beam Optics: Various optical elements condition the X-ray beam, including Soller slits for controlling beam divergence, monochromators for wavelength selection, and focusing mirrors for beam concentration [7].

Sample Stage: Holds the specimen and allows precise positioning and rotation during measurement. For protein crystallography, samples are typically mounted in nylon loops or on glass fibers and maintained at controlled temperatures (often cryogenic) to minimize radiation damage [7] [11].

Detector System: Records the diffracted X-rays and converts them into digital data. Modern diffractometers employ position-sensitive detectors (PSDs) or area detectors that simultaneously collect data over a range of angles, significantly reducing measurement time while maintaining high resolution [7].

Goniometer: The precision mechanical system controlling angular relationships between X-ray source, sample, and detector. Modern goniometers achieve angular accuracy better than 0.001° [7].

Data Collection Geometries

Different experimental approaches are employed based on sample characteristics and research objectives:

Table: Comparison of XRD Data Collection Methods

| Method | Sample Type | Pattern Characteristics | Primary Applications | Advantages/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal XRD [7] [8] | Large, well-ordered single crystal | Defined spots on detector | Complete structural determination; absolute configuration | Advantage: Highest information content; complete 3D structure Limitation: Requires large, high-quality crystals |

| Powder XRD [7] [12] | Microcrystalline powder | Concentric rings (Debye rings) | Phase identification; quantitative analysis; crystallite size | Advantage: Simple sample preparation; fast analysis Limitation: Peak overlap; lower information content |

| Fiber Diffraction [12] | Partially oriented fibers | Arcs or partial rings | Helical structures; DNA; fibrous proteins | Advantage: Handles partially ordered materials Limitation: Limited orientation information |

| Grazing Incidence XRD [12] | Thin films, surfaces | Elongated streaks | Surface structure; thin film characterization | Advantage: Surface-sensitive; minimal substrate interference Limitation: Specialized geometry required |

Protein Crystallography: Special Considerations and Techniques

Protein X-ray crystallography presents unique challenges compared to small molecule crystallography, primarily due to the complexity, flexibility, and fragility of biological macromolecules [13]. Proteins are large, often containing thousands of atoms, with delicate structures that can be easily damaged by X-ray radiation [13].

Sample Preparation and Optimization

The quality of protein crystals directly determines the success and resolution of an XRD experiment. Several specialized techniques have been developed for protein sample preparation:

Crystal Growth: Protein crystallization typically requires testing hundreds or thousands of conditions to find the optimal combination of pH, precipitant concentration, temperature, and additives that promote ordered crystal formation [9]. This process has been revolutionized by high-throughput robotic screening systems [13].

Cryocooling: To mitigate radiation damage during data collection, protein crystals are typically flash-cooled to cryogenic temperatures (around 100 K) using liquid nitrogen [13]. This requires cryoprotectants to prevent ice formation that could damage the crystal lattice.

Crystal Mounting: Protein crystals are extremely fragile and typically manipulated using specialized loops or micro-tools [11]. They are then mounted on a goniometer that allows precise rotation in the X-ray beam [7].

Advanced Methodologies in Protein XRD

Recent technological advances have addressed many challenges in protein crystallography:

Serial Crystallography (SX): This approach has revolutionized structural biology by enabling data collection from micro-to-nano-sized crystals [13]. Instead of collecting a complete dataset from a single large crystal, SX combines diffraction patterns from thousands of microcrystals, each exposed to X-rays only once [13]. This includes:

- Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX): Performed at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) using the "diffraction before destruction" principle, where ultra-bright femtosecond X-ray pulses capture diffraction patterns before the crystal is destroyed [13].

- Serial Millisecond Crystallography (SMX): Conducted at synchrotron sources with longer exposure times [13].

Time-Resolved Crystallography: This technique captures structural changes in proteins during biochemical reactions, creating "molecular movies" of biological processes [13]. Reactions can be initiated by light (for light-activated proteins) or by rapid mixing of substrates with enzyme crystals (Mix-and-Inject Serial Crystallography, MISC) [13].

Sample Delivery Systems: Various methods have been developed to efficiently deliver microcrystals to the X-ray beam in serial crystallography:

Data Analysis and Interpretation Workflow

The transformation of raw diffraction data into an atomic model involves a multi-step computational process with rigorous validation at each stage. The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Key Steps in Structure Determination

Data Reduction and Processing: Raw diffraction images are processed to determine the crystal orientation (indexing), integrate spot intensities, and scale measurements from different images [7]. This step yields a list of structure factor amplitudes (but not phases) for each reflection [8].

Phase Problem Solution: The critical challenge in crystallography is that diffraction patterns contain information about the amplitude but not the phase of structure factors [8]. Several approaches address this:

Electron Density Map Interpretation: The phased structure factors are used to calculate an electron density map, which is interpreted by building an atomic model that fits the observed density [8] [14]. Modern software tools facilitate this process through automated model building algorithms [7].

Refinement and Validation: The initial model is iteratively refined to improve agreement with the experimental data while maintaining stereochemical合理性 [12]. The final model is validated using various metrics including R-factors, Ramachandran plots, and real-space correlation coefficients [14].

Table: Key Metrics in Protein Structure Validation

| Validation Metric | Purpose | Ideal Values |

|---|---|---|

| R-factor/R-free [14] | Measures agreement between model and experimental data | R-free < 0.20 (high resolution) |

| Ramachandran Plot [14] | Assesses protein backbone torsion angles | >98% in favored regions |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) [14] | Evaluates bond lengths and angles | Bond lengths: <0.02 Å Bond angles: <2° |

| Clashscore [14] | Identifies steric conflicts between atoms | <10 (low clashes) |

| Real-Space Correlation Coefficient [14] | Measures local fit to electron density | >0.8 (well-defined regions) |

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein XRD

Successful protein X-ray crystallography requires specialized reagents and materials at each stage of the process. The following table outlines essential solutions and their applications:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Protein X-Ray Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Application Stage | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screening Kits [9] | Crystal Growth | Initial condition screening | Sparse matrix screens; PEG/Ion screens; Grid screens |

| Cryoprotectants [13] | Sample Preparation | Prevent ice formation during cryocooling | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, sucrose, paraffin oil |

| Heavy Atom Compounds [14] | Experimental Phasing | Provide anomalous scattering for phase determination | Platinum, gold, mercury, selenium derivatives |

| Crystal Mounting Loops [11] | Sample Mounting | Secure fragile crystals during data collection | Nylon, litholoops; various sizes (50-500 μm) |

| Synchrotron Beam Time [12] [13] | Data Collection | High-intensity X-ray source | Sector 22-ID at APS; Beamline 8.3.1 at ALS |

| Structure Solution Software [7] | Data Processing | Data analysis, phasing, refinement | Phenix, CCP4, HKL-3000, SHELX, Coot |

| Liquid Injection Systems [13] | Serial Crystallography | Deliver crystal streams to X-ray beam | Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN); Viscous extruders |

Applications in Drug Development and Metallodrug Research

X-ray crystallography plays a crucial role in modern drug development, particularly in structure-based drug design and understanding metallodrug mechanisms [14]. The technique provides atomic-level insights that are invaluable for rational drug optimization.

Protein-Metallodrug Interactions

The interaction between metal-based therapeutic compounds and their protein targets is a particularly important application of XRD in pharmaceutical research [14]. Protein metalation—the process by which a metal compound reacts with a protein to form a metal/protein adduct—underlies many biological events and therapeutic mechanisms [14]. X-ray crystallography has been used to characterize adducts formed between proteins and platinum (e.g., cisplatin), gold, ruthenium, rhodium, iridium, copper, manganese, and vanadium-based drugs [14].

These studies reveal precise metal coordination sites within protein structures, such as:

- Cisplatin fragments binding to His15 of hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) [14]

- Platinum binding to His105 and His119 side chains of bovine pancreatic ribonuclease (RNase A) [14]

- Cisplatin interaction with Cy

In protein X-ray crystallography, the phase problem represents the fundamental challenge that researchers must overcome to determine accurate three-dimensional macromolecular structures. While X-ray diffraction experiments readily yield the amplitudes of structure factors, the crucial phase information is lost during measurement, making direct reconstruction of electron density maps impossible. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of contemporary phasing methodologies, including molecular replacement, experimental phasing via anomalous scattering, and emerging computational approaches. Designed for structural biologists and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current technical protocols, quantitative comparisons of method efficacy, and visualization of core workflows essential for successful structure determination in basic and applied research contexts.

The phase problem constitutes the primary bottleneck in protein structure determination via X-ray crystallography. When X-rays scatter from a protein crystal, the detector records only the intensities of the diffracted waves, which provide the amplitudes of the structure factors (denoted as |Fₕₖₗ|), but fails to capture their phase relationships (denoted as αₕₖₗ) [15] [16]. This measurement incompleteness arises because X-ray frequencies (~10¹⁸ Hz) are too high for direct phase measurement [17]. Since both amplitude and phase are required to compute an electron density map through Fourier synthesis, this loss of phase information creates a fundamental reconstruction challenge [18] [19].

The critical importance of phases stems from their dominant role in defining structural features. As illustrated in Figure 1, phases carry substantially more structural information than amplitudes alone [16]. When electron density is calculated using correct phases, the atomic structure emerges clearly, whereas incorrect phases produce unrecognizable or misleading density. This sensitivity underlies why an estimated ~40% of crystallography projects encounter significant phasing difficulties, particularly for novel proteins lacking homologous structures [17]. Solving the phase problem is thus a prerequisite for obtaining accurate atomic models that enable rational drug design, enzyme mechanism elucidation, and understanding of biological function at the molecular level.

Theoretical Framework

Mathematical Foundation

The electron density ρ(xyz) at any point within the crystal unit cell is calculated through the Fourier transform:

$$ρ(xyz) = \frac{1}{V} \sum{h} \sum{k} \sum{l} |F{hkl}| e^{iα_{hkl}} e^{-2πi(hx+ky+lz)}$$

where V is the unit cell volume, |Fₕₖₗ| represents the structure factor amplitude, and αₕₖₗ is the phase angle for each reflection index hkl [16]. The measured intensity Iₕₖₗ in the diffraction pattern is proportional to the square of the amplitude (|Fₕₖₗ|²), enabling straightforward amplitude derivation but leaving the phase term undetermined.

The Patterson function provides an alternative representation that does not require phase information:

$$P(uvw) = \frac{1}{V} \sum{h} \sum{k} \sum{l} |F{hkl}|^2 e^{-2πi(hu+kv+lw)}$$

This function, computable directly from diffraction intensities, generates a map of interatomic vectors within the crystal [20]. While Patterson maps contain all necessary information for structure solution, their interpretation is challenging for proteins due to the high number of overlapping peaks (approximately n² for n atoms) [20].

Historical Context and Significance

The phase problem has been intrinsically linked to crystallography since the field's inception. The pioneering work of Perutz, Kendrew, Blow, and Crick developed early solutions through isomorphous replacement, enabling the first protein structures to be determined [16]. Over decades, crystallography has produced over 200,000 deposited structures in the Protein Data Bank, with nearly 10,000 added annually [13] [18], each requiring some solution to the phase problem. Despite technical advances, phasing remains the crucial step that transforms diffraction data into biological insight, particularly for structure-based drug design where accurate atomic positions determine binding site characterization and ligand optimization strategies.

Methodologies for Solving the Phase Problem

Molecular Replacement

Molecular replacement (MR) leverages prior structural knowledge to generate initial phase estimates. When a structurally similar model is available (typically >25% sequence identity and <2.0 Å Cα root-mean-square deviation) [16], its coordinates can be positioned within the unknown crystal's unit cell to calculate theoretical structure factors, including phases.

The MR workflow, depicted in Figure 2, involves two sequential searches:

- Rotation function: The model is rotated to match the orientation of molecules in the target crystal, typically analyzed using Patterson correlation methods [16].

- Translation function: The correctly oriented model is translated to its proper position within the unit cell by examining vectors between symmetry-related molecules [16].

Recent advances have significantly expanded MR applicability through machine learning-predicted models from AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold, which can provide adequate search models even without experimental structures of homologs [17]. However, MR remains ineffective for low-homology proteins or highly flexible regions where model inaccuracies introduce phase bias.

Figure 2: Molecular replacement workflow utilizing known structural information.

Experimental Phasing Methods

Experimental phasing techniques derive phase information empirically by introducing heavy atoms into protein crystals and measuring their differential scattering effects. These methods remain essential for de novo structure determination.

Anomalous Scattering

Anomalous scattering exploits the wavelength-dependent absorption and re-emission of X-rays by specific elements, causing phase shifts that enable phase determination [21] [15]. Key implementations include:

- Single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD): Uses a single X-ray wavelength to measure anomalous differences from incorporated heavy atoms [16].

- Multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD): Collects data at multiple wavelengths near the absorption edge of anomalous scatterers to optimize phasing power [15].

Selenium-methionine (Se-Met) labeling has become the dominant anomalous scattering approach, contributing to over 70% of de novo structures in the PDB [17]. By biosynthetically incorporating selenium into methionine residues, proteins generate sufficient anomalous signal without requiring additional heavy-atom soaking.

Isomorphous Replacement

Multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) involves creating heavy-atom derivatives by soaking native crystals in solutions containing electron-dense atoms (e.g., mercury, platinum, or uranium compounds) [16]. The key requirement is isomorphism - the protein structure and crystal packing must remain unchanged aside from the added heavy atoms. By comparing diffraction intensities between native and derivative crystals, the heavy-atom positions can be determined and used to derive phase information [21] [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Experimental Phasing Methods

| Method | Key Requirement | Typical Atoms Used | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD | Anomalous scatterers | Se (met), S, Hg, Pt | De novo phasing | Single dataset sufficient |

| MAD | Tunable X-ray source | Se, lanthanides | De novo phasing | Enhanced phasing power |

| MIR | Isomorphous derivatives | Hg, Pt, U, Au | De novo phasing | No special equipment |

| SIRAS | Isomorphous derivative + anomalous signal | Hg, Pt | De novo phasing | Combines MIR & anomalous |

Direct Methods and Density Modification

For small molecules diffracting to atomic resolution (<1.2 Å), direct methods can resolve phases using probabilistic relationships between structure factor amplitudes [15] [16]. These methods apply positivity and atomicity constraints (atoms as discrete scatterers) to establish phase relationships through the tangent formula:

$$\tan(αh) = \frac{\sum{h'} |E{h'}E{h-h'}| \sin(α{h'}+α{h-h'})}{\sum{h'} |E{h'}E{h-h'}| \cos(α{h'}+α_{h-h'})}$$

where E represents normalized structure factors [16]. While rarely applicable to macromolecules due to resolution limitations, direct methods are routinely used to locate heavy atoms in experimental phasing [16].

Density modification techniques improve initial phases by incorporating prior knowledge about electron density distributions:

- Solvent flattening: Exploits the uniform electron density of disordered solvent regions [15] [16]

- Histogram matching: Adjusts density statistics to match expected distributions [15]

- Non-crystallographic symmetry averaging: Applies known molecular symmetry constraints [15]

These approaches are particularly powerful in combination with experimental phasing, often enabling structure solution from marginal initial phase information.

Experimental Protocols

Selenomethionine SAD Phasing

Protocol Objective: Obtain experimental phases for a novel protein structure using selenomethionine incorporation and single-wavelength anomalous diffraction.

Materials and Reagents:

- Expression System: Methionine auxotroph E. coli strain or mammalian expression system

- Selenomethionine: L-selenomethionine for metabolic labeling

- Crystallization Reagents: Sparse-matrix screening kits optimized for the target protein

- Cryoprotectants: Glycerol, ethylene glycol, or other cryoprotective solutions

Procedure:

- Protein Expression and Purification:

- Grow expression host in minimal media supplemented with L-selenomethionine (50-100 mg/L)

- Induce protein expression at optimal temperature for soluble folding

- Purify using affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography

- Verify selenium incorporation by mass spectrometry

Crystallization:

- Concentrate Se-Met protein to 5-20 mg/mL

- Screen crystallization conditions using vapor diffusion methods

- Optimize crystal growth for size (>50 μm) and morphology

Data Collection:

- Flash-cool crystal in liquid nitrogen with appropriate cryoprotectant

- Collect single-wavelength dataset at the selenium absorption peak (~12.66 keV)

- Collect high-completeness dataset with redundant measurements for accurate anomalous signal

- Ensure maximum resolution better than 3.0 Å for interpretable maps

Structure Solution:

- Process data to obtain intensities and anomalous differences

- Locate selenium positions using direct methods (SHELXD or HySS)

- Calculate experimental phases and perform density modification

- Build atomic model into improved electron density

Technical Considerations: Radiation damage is a significant concern at synchrotron sources. Collect inverse-beam data or use multiple crystals to minimize decay. For membrane proteins, consider lipidic cubic phase crystallization with Se-Met labeling [17].

Molecular Replacement with Predicted Models

Protocol Objective: Solve protein structure using AlphaFold-predicted models as molecular replacement search models.

Materials and Software:

- AlphaFold Model: Predicted structure from AlphaFold Protein Structure Database or custom prediction

- MR Software: Phaser, Molrep, or MR-Rosetta

- Model Preparation Tools: CHAINSAW or Sculptor for model editing

Procedure:

- Model Preparation:

- Download or generate AlphaFold model for target protein

- Remove low-confidence regions (pLDDT < 70)

- Split multi-domain proteins into individual domains if necessary

- Convert model to search format compatible with MR software

Molecular Replacement:

- Perform rotation function search with trimmed model

- Execute translation function with top rotation solutions

- Assess solutions by log-likelihood gain and translation function Z-scores

- Combine multiple domains if protein contains distinct folded regions

Phase Improvement:

- Calculate initial phases from positioned model

- Apply automated model building (ARP/wARP or Buccaneer)

- Iteratively refine model against experimental data

- Validate final model geometry and fit to electron density

Technical Considerations: AlphaFold models may contain topological errors in challenging regions. Use composite omit maps to validate areas with potential model bias and consider manual rebuilding for discrepant regions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Crystallographic Phasing

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| L-selenomethionine | Anomalous scatterer | SAD/MAD phasing |

| Heavy-atom compounds (HgAc₂, K₂PtCl₄, UO₂Ac₂) | Isomorphous replacement | MIR/SIRAS phasing |

| Crystallization screens (sparse-matrix) | Crystal formation | Initial crystal growth |

| Cryoprotectants (glycerol, ethylene glycol) | Crystal preservation | Cryo-crystallography |

| Lipidic cubic phase materials | Membrane protein stabilization | Membrane protein crystallography |

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

Machine Learning and Deep Learning

Recent advances in deep learning have demonstrated potential for directly solving the phase problem. Convolutional neural networks can predict electron density maps from Patterson maps, effectively learning the transformation between autocorrelation and density functions [20]. Specific architectures include:

- CrysFormer: Uses Patterson maps and attention mechanisms to infer atomic coordinates directly from diffraction data [17]

- 3D convolutional networks: Process Patterson maps to output electron density estimates, trained on known structures from the PDB [20]

These approaches represent a paradigm shift from traditional phasing, potentially enabling direct structure solution without heavy atoms or homologous models. Current limitations include resolution dependencies and training dataset requirements, but rapid progress suggests increasing applicability to challenging phasing problems.

XFEL and Serial Crystallography

X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) enable serial femtosecond crystallography using the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle [13]. By collecting diffraction from microcrystals before radiation damage occurs, XFELs expand the range of phasing possibilities:

- De novo phasing from native sulfur-SAD: Enhanced anomalous signal from native sulfurs due to reduced radiation damage [13]

- Time-resolved phasing: Tracking structural changes during biochemical reactions [13]

- Reduced sample consumption: Modern sample delivery methods require as little as 450 ng of protein for complete datasets [13]

The integration of XFEL capabilities with traditional phasing methods continues to expand the boundaries of soluble and membrane protein structure determination.

Figure 3: Relationship between major phasing methodologies and their applications.

Solving the phase problem remains the pivotal step in transforming X-ray diffraction data into biologically meaningful protein structures. While traditional methods like molecular replacement and experimental phasing continue to evolve with improved algorithms and instrumentation, emerging approaches leveraging machine learning and XFEL technology promise to expand the frontiers of structural biology. The choice of phasing strategy depends critically on available resources, protein characteristics, and project goals. For researchers engaged in drug development and functional studies, understanding these methodologies enables informed experimental design and maximizes the likelihood of successful structure determination. As structural biology continues to integrate hybrid approaches and computational advances, the phase problem—while still central—becomes increasingly tractable for ever more challenging biological systems.

Within the framework of basic principles of protein X-ray crystallography research, the process of transforming experimental X-ray diffraction data into an accurate atomic model represents a critical pathway to understanding biological function at the molecular level. This technique has been foundational, enabling high-resolution structural determination of a plethora of biomolecules and playing a key role in areas such as structure-based drug design and the elucidation of enzyme mechanisms [13] [19]. The core aim of X-ray crystallography is to obtain a three-dimensional molecular structure from a crystal by analyzing the diffraction patterns produced when a crystal is exposed to an X-ray beam [19]. The journey from data to model hinges on solving the phase problem, a fundamental challenge that must be overcome to calculate electron density maps and ultimately build the atomic structure of the protein under investigation. This guide details the technical workflow, from the initial diffraction data to the refined structural model, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Experimental Foundation: Data Collection

The process begins with the growth of a high-quality protein crystal. A purified sample at high concentration is crystallised, often using vapour diffusion methods, and the resulting crystals must be of a sufficient size (typically a minimum of 0.1 mm) to diffract effectively [19]. Serial crystallography (SX), which uses microcrystals, has revolutionized the field by enabling studies of previously intractable targets, though it requires specialized sample delivery methods such as fixed-targets or liquid injection to manage significant sample consumption [13].

During data collection, the crystal is mounted in an X-ray beam, either from a laboratory source or a much more intense synchrotron, and rotated to capture diffraction from all possible crystal lattice planes [19]. The primary output is a set of diffraction images, where the positions of the spots indicate the geometry of the crystal lattice, and their intensities are the key data used for structure determination [19]. A critical quality metric is the resolution of the data, which determines the level of atomic detail visible; a resolution of 3 Å or better is generally required to distinguish amino acid side chains [19].

Table 1: Key Data Collection Parameters and Their Impact on Structure Determination

| Parameter | Description | Typical Requirements/Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | The finest level of detail observable in the data. | ≤ 3 Å to resolve side chains; ≤ 1.5 Å for atomic detail. |

| Unit Cell | The fundamental repeating unit of the crystal. | Determined from spot spacing; defines crystal system. |

| Space Group | The symmetry of the crystal lattice. | Determined from spot symmetry; 65 possible groups for proteins. |

| Completeness | The fraction of possible diffraction data collected. | Should be >95% for a robust dataset. |

| Redundancy (Multiplicity) | The average number of times each unique reflection is measured. | Higher redundancy improves data quality and statistical accuracy. |

The Core Computational Challenge: The Phase Problem

Once the intensities of the diffraction spots are measured and processed, they are used to calculate the structure factor amplitudes (|F|). Each structure factor has both an amplitude and a phase, and together they are used to compute the electron density map of the crystal via a Fourier transform [19]. The central challenge, known as the "phase problem," is that while the amplitudes can be directly measured from the spot intensities, the phase information is lost in the experiment. Since accurate phases are essential for producing an interpretable electron density map, several computational and experimental methods have been developed to recover them.

Methods for Solving the Phase Problem

- Molecular Replacement (MR): This is the most common method when a structurally similar model is already available. The known model is oriented and positioned within the unit cell of the unknown structure, and its calculated phases provide an initial estimate to start the process [19].

- Experimental Phasing: For novel structures with no known homolog, experimental methods are required. These include:

- Isomorphous Replacement: Involves binding heavy atoms (e.g., mercury, platinum) to the protein without disturbing the crystal lattice. The differences in diffraction intensity between native and derivative crystals allow for phasing.

- Anomalous Dispersion: Utilizes the anomalous scattering signal from atoms like selenium (incorporated via selenomethionine) or heavy metals when using X-rays of a specific wavelength. This method is particularly powerful and is the basis for Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD) or Multi-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD) phasing.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the pathway from a protein sample to an initial electron density map, highlighting the critical phasing step.

From Electron Density to Atomic Model

Calculating and Interpreting the Electron Density Map

With both structure factor amplitudes and estimated phases in hand, the three-dimensional electron density map, ρ(xyz), is calculated using the following fundamental equation of crystallography:

ρ(xyz) = 1/V Σh Σk Σl |F(hkl)| eiφ(hkl) e-2πi(hx+ky+lz)

Where:

- ρ(xyz) is the electron density at point (x,y,z) in the unit cell.

- V is the volume of the unit cell.

- |F(hkl)| is the structure factor amplitude for reflection hkl.

- φ(hkl) is the phase for reflection hkl.

- The triple summation is over all measured reflections (h,k,l) [19].

The quality of this initial map is often improved through a process of density modification, which uses prior chemical knowledge (e.g., that density should be flat in the solvent region) to refine the phases and yield a clearer, more interpretable map.

Model Building and Refinement

The improved electron density map is used as a guide to build the atomic model. Researchers use software to fit the known protein sequence into the electron density, placing atoms for the main chain and side chains. This initial model is then refined against the original diffraction data in an iterative cycle.

Refinement is the process of adjusting the atomic model (atomic coordinates and atomic displacement parameters) to best fit the observed diffraction data (|Fobs|) while respecting known stereochemical constraints. The fit is quantified by R-factors (R and Rfree). Modern approaches within quantum crystallography, such as Hirshfeld Atom Refinement (HAR), are now becoming more accessible. These methods use more physically realistic non-spherical atoms, allowing for extremely accurate structure determination, including hydrogen atom positions, with the same precision as neutron diffraction [22].

Table 2: Key Software and Algorithms in Structure Solution

| Software/Algorithm | Primary Function | Technical Application |

|---|---|---|

| HAR (Hirshfeld Atom Refinement) | Quantum crystallographic refinement. | Determines accurate hydrogen atom positions and anisotropic displacement parameters using aspherical atoms [22]. |

| XD | Multipole model refinement. | Used for experimental charge-density determination via multipole modelling [22]. |

| XCW (X-ray Constrained Wavefunction) Fitting | Quantum crystallographic refinement. | Fits a wavefunction to the X-ray diffraction data to derive electron densities and chemical bonding information [22]. |

| Diffusion Generative Modeling | AI-powered structure solution. | Machine learning technique that augments low-information nanocrystal diffraction data to solve previously intractable structures [23]. |

The following diagram summarizes the iterative process of model building and refinement, leading to the final deposited structure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and software solutions essential for conducting protein X-ray crystallography experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Protein Crystallography

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Screen Kits | Sparse matrix screens for initial crystallization condition screening. | Commercial solutions covering a wide range of precipitants, buffers, pH, and salts to identify initial crystallization hits [19]. |

| Cryoprotectants | Protect crystals from ice formation during flash-cooling. | Solutions like glycerol or ethylene glycol are used to cryoprotect crystals before flash-freezing in liquid N₂ for data collection at 100 K [19]. |

| Heavy Atom Derivatives | reagents for experimental phasing. | Compounds containing atoms like Hg, Pt, Au, or Lu used for isomorphous replacement or anomalous dispersion phasing (e.g., K₂PtCl₄, EMTS) [19]. |

| Selenomethionine | Anomalous scatterer for phasing. | Used in metabolic labeling of proteins to incorporate Se atoms for SAD/MAD phasing without altering protein structure. |

| Lithium Chloride (LiChroprep) | Purification and homogenization. | Used in column chromatography for final purification and homogenization of the protein sample prior to crystallization [24]. |

| HAR & XD Software | Software for advanced quantum crystallographic refinement. | Enable accurate refinement of hydrogen positions and experimental electron density analysis beyond the independent atom model [22]. |

From Theory to Therapy: Methodological Workflow and Drug Discovery Applications

Within the broader principles of protein X-ray crystallography research, the technique stands as a foundational pillar for understanding the three-dimensional structure of biological macromolecules. This method is responsible for determining approximately 85-90% of the structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), making it the most dominant technique in structural biology [25] [26]. The power of X-ray crystallography lies in its ability to provide an atomic-resolution model, which is indispensable for inferring protein function, understanding enzyme mechanisms, guiding site-directed mutagenesis, and facilitating structure-based drug design [19] [26]. This guide details the comprehensive, multi-step workflow required to transition from a heterogeneous protein sample to a refined, validated atomic model, a process that is often described as both a science and an art [18].

The Protein Crystallography Workflow

The journey to a refined protein structure is a linear and sequential process, where the success of each stage is a prerequisite for the next. The entire pipeline can be visualized as a series of interdependent steps, from gene to final model.

The following diagram maps the entire pathway from protein purification to a refined model, highlighting the key stages and their relationships.

Step 1: Protein Production and Purification

The initial and crucial stage of the workflow is obtaining a pure, homogeneous, and stable sample of the protein of interest. The quality of the final structural model is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the protein sample at this stage.

Protein Purification Metrics and Targets

A successful purification must meet specific quantitative and qualitative benchmarks, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Benchmarks for Protein Purification prior to Crystallization

| Parameter | Ideal Target | Importance for Crystallization |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | >95% (ideally >99%) [25] | Impurities disrupt the ordered lattice formation necessary for crystal growth [25]. |

| Concentration | 5 - 50 mg/mL (often 10-20 mg/mL) [3] [18] | A high concentration is required to achieve supersaturation, the driving force for crystallization. |

| Homogeneity | Monodisperse in solution [25] | Ensures all molecules are chemically and conformationally identical, allowing for a regular crystal lattice. |

| Stability | Maintains folded state and monodispersity over time. | The protein must remain intact and non-aggregated during the often slow crystallization process. |

Detailed Purification Protocol

The standard approach involves a combination of chromatographic techniques to achieve the required homogeneity.

- Protein Production: The gene encoding the protein is cloned into an expression plasmid, which is then used to transform a host system like Escherichia coli. Protein expression is induced, and cells are lysed to release the contents [18].

- Affinity Chromatography: This is typically the first purification step. The target protein is engineered with a specific tag (e.g., His-tag). As the cell lysate passes over a chromatography column with immobilized metal ions or other binding partners, the tagged protein binds specifically, while impurities are washed away. The pure protein is then eluted [25].

- Further Purification (Polishing): To achieve the high purity required, one or more additional steps are often necessary:

- Ion-Exchange Chromatography: Separates proteins based on their surface charge [25].

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Separates proteins according to their size and hydrodynamic radius. SEC is also a key analytical method for confirming the monodispersity and oligomeric state of the purified sample [25].

- Concentration and Buffer Exchange: The purified protein is concentrated using centrifugal filters and exchanged into a suitable, non-crystallizing buffer for the next stage. The final concentration is determined by measuring absorbance at 280 nm using the protein's extinction coefficient [3].

Step 2: Protein Crystallization

Crystallization is widely considered the major bottleneck in protein crystallography [3] [19]. The objective is to bring the protein solution to a state of supersaturation slowly and controllably, prompting the molecules to come out of solution and form a highly ordered, three-dimensional crystal lattice rather than an amorphous precipitate [3] [19].

The Crystallization Phase Diagram

Understanding the phase diagram is key to navigating the crystallization process, as it guides the selection of conditions to reach the nucleation zone.

Detailed Crystallization Protocols

The most common method for initial screening is vapor diffusion, which can be set up in two configurations.

Hanging Drop Vapor Diffusion [3]:

- A reservoir well is filled with 500 μL of a precipitant solution.

- A silicone grease ring is applied around the rim of the well.

- A cover slide is cleaned, and a drop (typically 1-2 μL) of the concentrated protein solution is mixed with an equal volume of the precipitant solution on the slide.

- The cover slide is carefully flipped and sealed over the reservoir, creating a closed chamber.

- The drop is initially at a lower concentration than the reservoir. Water vapor diffuses from the drop to the reservoir over hours to days, slowly concentrating both the protein and the precipitant in the drop until equilibrium is reached. This slow concentration increase ideally guides the solution into the nucleation zone of the phase diagram.

Sitting Drop Vapor Diffusion: The principle is identical, but the protein-precipitant mixture is dispensed onto a small shelf or post, and the well is sealed with transparent tape instead of a cover slide [3].

Microbatch Crystallization under Oil: An alternative method where 1 μL of protein solution is directly mixed with 1 μL of precipitant solution under a layer of paraffin oil. The oil prevents evaporation of the drop, and crystallization occurs without vapor diffusion [3].

Common Precipitants and Screening

Initial screening uses commercially available "sparse matrix" screens, which contain 96 different conditions that sample a wide range of precipitants, salts, buffers, and pH values [19]. The most common precipitants are polyethylene glycol (PEG) of various molecular weights and ammonium sulfate, which together account for about 60% of successful crystallization conditions [3].

Step 3: Crystal Harvesting and Data Collection

Once a crystal of adequate size (typically > 0.1 mm in the longest dimension) has grown, it must be prepared for X-ray exposure [19].

Crystal Harvesting and Cryocooling Protocol

- Cryoprotection: Protein crystals are typically ~50% solvent by volume and are highly sensitive to radiation damage. To mitigate this, crystals are cryocooled to ~100 K in a stream of liquid nitrogen. The crystal is first transferred for a few seconds into a solution identical to its mother liquor but with an added cryoprotectant (e.g., 20-25% glycerol or ethylene glycol) to prevent the formation of destructive ice crystals upon freezing [19].

- Mounting: The cryoprotected crystal is fished from the drop using a small nylon or plastic loop. The loop, with the crystal suspended in a thin film of solution, is then rapidly vitrified by plunging it into liquid nitrogen [19].

- X-ray Source and Detector: The frozen crystal is placed on a goniometer, which allows for precise rotation in the X-ray beam. Data can be collected using an in-house laboratory source (e.g., rotating anode) or, more commonly for high-quality data, at a synchrotron facility, which provides extremely intense, tunable X-rays [19] [27]. The diffracted X-rays are recorded on detectors such as hybrid photon-counting (HPC) detectors [27].

Step 4: Data Processing, Phasing, and Model Building

This stage transitions from experimental work to computational analysis, transforming the raw diffraction images into an atomic model.

Data Processing and Reduction Protocol

- Indexing and Integration: The series of diffraction images (see figure below) is processed by specialized software (e.g., XDS, DIALS, HKL-2000). The software indexes the pattern to determine the crystal's unit cell dimensions (a, b, c, α, β, γ) and space group. It then integrates the images to measure the intensity of each reflected X-ray beam (reflection) [19] [27].

- Data Quality Assessment: The integrated data are scaled and merged to produce a final set of structure factors. Key metrics for assessing data quality are summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Assessing X-ray Diffraction Data Quality

| Metric | Ideal Target | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | As high as possible (e.g., <2.0 Å) | The minimum interplanar spacing (d) resolved. Higher resolution (lower number) allows for clearer atomic detail. A carbon-carbon bond is ~1.5 Å [19]. |

| Completeness | >95% (>99% for low resolution) | The fraction of possible reflections that were actually measured [27]. |

| Rmerge / Rmerge | <10% (lower is better) | A measure of the agreement between multiple measurements of the same reflection. Critical for assessing the signal-to-noise ratio [27]. |

| I/σ(I) | >2.0 (at high resolution) | The average intensity of a reflection divided by its uncertainty. A measure of the signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Multiplicity | As high as feasible (e.g., 3-10) | The average number of times each unique reflection was measured. High redundancy improves the accuracy of the final merged intensity [27]. |

The Phase Problem and Molecular Replacement Protocol

The measured intensities give the amplitude of the structure factor, but the phase information is lost in the diffraction experiment. This is known as the "phase problem." The most common method to solve it is Molecular Replacement (MR) [25].

- Search Model Preparation: A previously solved structure of a homologous protein is used as a search model. This model is often modified to match the target sequence as closely as possible.

- Rotation and Translation Functions: Computational algorithms perform a six-dimensional search to find the correct orientation (rotation function) and position (translation function) of the search model within the unit cell of the target crystal.

- Phasing: Once correctly placed, the search model provides an initial set of phases. These phases are combined with the experimental amplitudes to calculate an initial electron density map [25].

Model Building, Refinement, and Validation Protocol

- Model Building: The initial electron density map is often of poor quality. Using programs like Coot, the researcher fits the amino acid sequence of the target protein into the electron density, correcting the model to match the data [28].

- Refinement: The atomic model is iteratively improved against the diffraction data using refinement programs (e.g., REFMAC, phenix.refine). This is a cyclic process of adjusting atomic coordinates and temperature factors (B-factors) to minimize the difference between the observed data (Fobs) and the data calculated from the model (Fcalc). The progress is tracked by the R-work and R-free factors. R-free is calculated using a small subset of reflections not used in refinement and is a crucial indicator of model quality and lack of overfitting [27].

- Validation: The final model is rigorously checked for geometric and stereochemical correctness (e.g., using MolProbity). This includes analyzing bond lengths, angles, rotamer outliers, and Ramachandran plot outliers to ensure the model is both chemically reasonable and fits the experimental data [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful crystallography project relies on a suite of specialized reagents, equipment, and software.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Protein Crystallography

| Category | Item / Technique | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Purification | Affinity Chromatography (e.g., His-tag) | Primary capture and purification step [25]. |

| Ion-Exchange Chromatography | Polishing step; separates by charge [25]. | |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Polishing step; separates by size; assesses monodispersity [25]. | |

| Crystallization | Sparse Matrix Screens (e.g., from Hampton Research) | Initial condition screening using incomplete factorial design [3] [19]. |

| 24-well Hanging/Sitting Drop Trays | Plates for setting up vapor diffusion experiments [3]. | |

| Liquid Handling Robot (e.g., Mosquito) | Automates dispensing of nanoliter-volume crystallization drops for high-throughput screening [29] [28]. | |

| Data Collection | Synchrotron Beamline | Intense X-ray source for high-quality, rapid data collection [25] [27]. |

| Cryostream (Liquid N2) | Maintains crystal at ~100 K to minimize radiation damage [19]. | |

| CCD or Hybrid Photon-Counting (HPC) Detector | Records diffraction images with high sensitivity and speed [19] [27]. | |

| Software | CCP4 Suite | Comprehensive collection of programs for data processing, phasing, refinement, and analysis [28]. |

| Phenix | Software platform for automated structure determination [28]. | |

| Coot | Interactive tool for model building, rebuilding, and validation [28]. | |

| PyMOL | Molecular graphics system for visualization and figure generation [28]. |

Identifying and Validating Drug Targets through 3D Structure

The process of drug discovery has been revolutionized by the ability to visualize biological macromolecules at atomic resolution. Among the techniques available for structure determination, X-ray crystallography has been the most prolific, providing approximately 85% of all protein structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [26] [30]. This guide details how the three-dimensional structures of potential drug targets, determined primarily through X-ray crystallography, are identified and validated in modern drug development pipelines. The foundational principle is that knowing the precise atomic arrangement of a target protein enables researchers to understand its function and design molecules that can modulate that function with high specificity [31].

The critical importance of this approach stems from its direct impact on understanding disease mechanisms and therapeutic intervention. By analyzing crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes, researchers can study specific interactions between a drug candidate and its target at the atomic level, enabling rational design and optimization of therapeutic compounds [31]. This structural perspective is particularly valuable for tackling increasingly challenging targets such as G-protein coupled receptors, ion channels, and other macromolecules with complex mechanisms [13] [32].

Fundamental Principles of Protein X-Ray Crystallography

Protein X-ray crystallography relies on several key principles that enable the determination of atomic structures. When a crystal is exposed to an X-ray beam, the regular arrangement of molecules within the crystal diffracts the X-rays, producing a characteristic pattern of spots [33] [30]. The fundamental relationship governing this diffraction is Bragg's Law: (nλ = 2d sinθ), where (λ) is the wavelength of the X-rays, (d) is the spacing between atomic planes in the crystal, (θ) is the angle of incidence, and (n) is an integer [33]. This relationship allows researchers to calculate the dimensions of the unit cell from the diffraction pattern.

The intensity of these diffraction spots is measured and used to calculate an electron density map, which is then interpreted to build an atomic model of the protein [30]. However, a major challenge in this process is the "phase problem" – while the intensities of the diffraction spots can be measured directly, the phase information is lost during data collection. This missing information must be determined through specialized methods such as molecular replacement or experimental techniques like multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion to reconstruct the electron density map [30].

The entire process, from protein purification to structure determination, requires highly specialized equipment and reagents. The table below summarizes key components of the modern crystallographer's toolkit.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Protein Crystallography

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | X-ray Diffractometers, Microfluidic Systems, Incubators & Temperature Control Devices [34] | Generate X-rays, control crystal growth conditions, and maintain crystal stability during data collection |

| Consumables | Crystallization Reagents, Microplates, Screens & Buffers, Cryoprotectants [34] | Create optimized chemical environments for protein crystallization and crystal cryopreservation |

| Software & Services | Crystallography Data Analysis Software, AI-Based Structure Prediction Tools, Custom Crystallization Services [34] | Process diffraction data, build atomic models, predict crystallization conditions, and provide expert services |

Recent advances in serial crystallography have transformed the field, particularly for studying reaction mechanisms. This approach uses microcrystals and either synchrotron or X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) sources to collect data from thousands of crystals, enabling studies of previously inaccessible targets [13]. The method of serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) at XFELs utilizes the "diffraction before destruction" concept, where ultra-bright femtosecond X-ray pulses capture diffraction patterns before the sample is destroyed, opening new possibilities for time-resolved studies [13] [30].

Experimental Workflow for Structure Determination

The journey from a potential drug target to a validated three-dimensional structure follows a multi-step experimental pathway, with each stage being critical to the success of the overall process.

Sample Preparation and Crystallization

The initial and often most challenging phase involves producing high-quality protein samples suitable for crystallization. This begins with protein purification to obtain homogeneous, stable protein solutions [26]. The purified protein is then subjected to crystallization trials, where thousands of chemical conditions are screened to identify those that promote the formation of well-ordered crystals [26] [30]. This process has been significantly accelerated through automation and high-throughput approaches, which are now supported by specialized companies and core facilities [34].

Data Collection and Processing

Once suitable crystals are obtained, they are exposed to intense X-ray beams at synchrotron facilities. The rotation method is most commonly employed, where the crystal is continuously rotated while being exposed to X-rays, and diffraction images are captured on area detectors [35]. The resulting diffraction patterns are then processed through specialized software packages such as Mosflm, HKL-2000, XDS, or DIALS [35]. Key steps in processing include autoindexing to determine crystal orientation and unit cell parameters, integration to measure spot intensities, and scaling to put all measurements on a common scale [35].

Structure Solution and Refinement

The processed diffraction data are used to solve the crystal structure through molecular replacement (if a related structure exists) or experimental phasing methods (for novel folds) [30]. An initial atomic model is built into the experimental electron density map and undergoes iterative cycles of refinement to improve the agreement between the model and the experimental data [30]. The final refined model represents the atomic structure of the protein, which is then deposited in the public Protein Data Bank for the scientific community to access [30].

Analytical Methods for Structure-Based Drug Discovery

Once a high-quality structure is obtained, it becomes a powerful tool for drug discovery through various analytical approaches.

Binding Site Identification and Analysis

The first analytical step typically involves identifying and characterizing potential binding sites on the protein surface. Ligand-binding pockets are often located in concave surface regions and can be identified through computational analysis of surface geometry and physicochemical properties. Critical analysis includes assessing the druggability of these sites – evaluating whether a binding pocket possesses the necessary properties to bind drug-like molecules with high affinity and specificity [31].

Structure-Based Drug Design

With a characterized binding site, researchers can employ several structure-based strategies for drug design. Molecular docking computationally screens small molecules for their predicted binding affinity and orientation within the target site. Structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis uses structures of multiple ligand complexes to understand how chemical modifications affect binding, guiding iterative compound optimization [31]. Additionally, de novo drug design builds novel chemical entities directly within the constraints of the binding pocket.

Advanced Applications: Time-Resolved Studies

Beyond static structures, advanced techniques like time-resolved crystallography can capture proteins in action, providing unprecedented insights into functional mechanisms. A notable example is Electric-field stimulated time-resolved X-ray crystallography (EFX), which has been used to visualize ion conduction through potassium channels in real-time [32]. Such "molecular movies" offer direct observation of dynamic processes that are fundamental to protein function, enabling more sophisticated drug design strategies that target specific conformational states [32].

Structure Validation and Quality Assessment

Before a protein structure can be confidently used for drug discovery applications, it must undergo rigorous validation to assess its reliability. The quality assessment should be factored into any structural analysis, as it indicates which parts of the 3D structure are determined with high confidence and which parts should not be relied upon [36].

Table 2: Key Validation Metrics for X-ray Crystallography Structures

| Quality Measure | Description | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Measure of detail visible in the experimental data; lower values indicate better resolution [36] | <1.5 Å: Very high quality; 1.5-2.5 Å: High quality; 2.5-3.5 Å: Medium quality; >3.5 Å: Low quality [36] |

| R-factor & R-free | R-factor measures agreement between model and experimental data; R-free is calculated against a subset of data not used in refinement [36] | Lower values indicate better agreement (typically 0.15-0.25); Large difference between R-factor and R-free may indicate over-fitting [36] |

| Real Space Correlation Coefficient (RSCC) | Measures how well atomic coordinates match experimental electron density for each residue [36] | Values close to 1.0 indicate excellent fit; Residues with RSCC in lowest 1% should not be trusted [36] |

| Ramachandran Plot | Assesses the stereochemical quality of protein backbone torsion angles [36] | High-quality structures have >98% of residues in favored and allowed regions [36] |

Validation reports are available for all structures in the PDB, generated according to recommendations from expert Validation Task Forces [36]. These reports provide an executive summary image of key quality indicators to help non-experts assess structure reliability [36]. Particular attention should be paid to regions of the structure that will interact with potential drug compounds, ensuring that the electron density support and geometric quality are sufficient for informed drug design decisions.

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The field of structure-based drug discovery continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to enhance its impact. Serial crystallography methods are addressing the challenge of sample consumption, with recent approaches reducing protein requirements from grams to micrograms, making previously intractable targets accessible [13]. The convergence of artificial intelligence with structural biology is creating new opportunities, as demonstrated by AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold for protein structure prediction [36] [37]. These computational advances are particularly valuable for studying disordered proteins and characterizing conformational ensembles that represent significant challenges for traditional structural methods [37].

The market for protein crystallization reflects these technological shifts, with projections showing growth from $1.62 billion in 2024 to $2.8 billion by 2029, driven by rising demand for protein-based drug development and advancements in protein-ligand interaction research [34]. This growth is accompanied by increased integration of AI-based structure prediction tools and automated crystallization platforms, further accelerating the structure determination pipeline [34].