Rapid Antigen Tests vs. RT-PCR: A Comprehensive 2025 Performance Analysis for Clinical Research

This article provides a systematic evaluation of the comparative diagnostic performance of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests (RATs) and real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Rapid Antigen Tests vs. RT-PCR: A Comprehensive 2025 Performance Analysis for Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a systematic evaluation of the comparative diagnostic performance of SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests (RATs) and real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). For researchers and drug development professionals, we synthesize current evidence on RAT sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values across different viral loads, variants, and clinical scenarios. The analysis covers foundational principles, methodological applications in real-world settings, strategies for troubleshooting performance limitations, and validation through manufacturer-independent studies. Evidence confirms that while RATs offer operational advantages of speed and accessibility, their significantly lower sensitivity compared to the RT-PCR gold standard necessitates a context-dependent application, particularly in low-prevalence settings or for early infection detection.

Understanding the Core Technologies: Principles and Performance Benchmarks of Antigen and Molecular Tests

The accurate and timely detection of pathogenic agents represents a cornerstone in the effective management and control of infectious diseases. The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has underscored the critical importance of reliable diagnostic tools for containing disease spread and guiding clinical interventions. Two principal laboratory diagnostic methodologies have emerged as pivotal technologies: antigen detection via immunoassay and nucleic acid amplification via reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). These techniques operate on fundamentally different biological principles, offering distinct advantages and limitations in sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, and operational requirements.

This comparative analysis examines the fundamental mechanisms underlying these diagnostic approaches, evaluates their performance characteristics based on recent clinical studies, and discusses their appropriate applications within clinical and public health contexts. The objective is to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive, evidence-based guide for test selection and implementation within their specific operational frameworks and diagnostic objectives.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Technical Principles

Antigen Detection via Immunoassay

Antigen detection assays are designed to identify the presence of specific viral proteins, typically the nucleocapsid (N) or spike (S) proteins of SARS-CoV-2. The core principle relies on antibody-antigen interactions, where labeled antibodies bind specifically to target viral antigens present in clinical specimens.

Key Mechanism Steps:

- Sample Preparation: Nasopharyngeal or nasal swab samples are collected and placed in viral transport media or specific extraction buffers. The sample may be treated to disrupt viral particles and release internal antigens.

- Antigen-Antibody Binding: The prepared sample is applied to a test platform containing immobilized capture antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 antigens. If viral antigens are present, they form complexes with the capture antibodies.

- Signal Generation and Detection: A labeled detection antibody (conjugated to enzymes, fluorescent tags, or colored particles) binds to the captured antigen, forming a "sandwich" complex. Unbound components are washed away. The signal is generated through:

- Chromogenic substrates that produce visible lines (lateral flow assays)

- Chemiluminescence where enzyme-substrate reactions emit light (CLIA)

- Electrochemiluminescence where electrochemical reactions trigger light emission (ECLIA)

Technical Variations:

- Lateral Flow Immunoassays (LFIA): Simple, rapid tests providing visual results within 15-30 minutes, suitable for point-of-care settings [1].

- Automated Immunoassays: Utilize chemiluminescence (CLIA) or electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA) technology on automated platforms (e.g., Lumipulse, VITROS, Elecsys), offering semi-quantitative results with enhanced sensitivity and throughput in laboratory settings [2] [3] [4].

Nucleic Acid Detection via RT-PCR

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) represents the gold standard for molecular detection of SARS-CoV-2, targeting specific sequences of the viral RNA genome through enzymatic amplification.

Key Mechanism Steps:

- Viral RNA Extraction: Viral particles in the specimen are lysed, and viral RNA is purified from other sample components using magnetic bead or column-based extraction methods to remove potential inhibitors.

- Reverse Transcription: The single-stranded RNA genome is reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase enzymes.

- Target Amplification: The cDNA undergoes exponential amplification through repeated temperature cycles (denaturation, annealing, extension) in the presence of:

- Sequence-specific primers that flank the target region (e.g., N, E, RdRp, ORF1ab genes)

- Fluorogenic probes (TaqMan) that bind specifically to the target sequence and emit fluorescence upon cleavage

- Real-Time Detection: Fluorescence intensity is measured after each amplification cycle. The cycle threshold (Ct) value is determined as the number of cycles required for the signal to exceed a background threshold, providing an inverse correlation with viral load [1] [5].

Technical Variations:

- Conventional RT-PCR: Requires post-amplification processing and detection.

- Real-Time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR): Enables simultaneous amplification and detection, providing quantitative results and reduced contamination risk.

- Automated NAAT Systems: Integrated platforms (e.g., Xpert Xpress, FilmArray) that streamline extraction, amplification, and detection in self-contained cartridges, reducing hands-on time and operational complexity [5].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Clinical evaluations across diverse populations and settings have demonstrated significant differences in the diagnostic performance of antigen and RT-PCR assays.

Table 1: Overall Diagnostic Performance of Antigen Tests Versus RT-PCR

| Study & Platform | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Sample Size (N) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Q Ag Test [1] | 98.33 | 98.73 | 454 | Symptomatic & asymptomatic |

| VITROS CLIA [2] | 73.47 | 100.00 | 148 | Symptomatic & asymptomatic |

| Zydus RAT [6] | 75.17 | 98.89 | 329 | Symptomatic & asymptomatic |

| Roche Elecsys ECLIA [4] | 72.40 | 95.00 | 170 | Suspected COVID-19 |

| Quidel Sofia FIA [7] | 72.10 (Symptomatic) 60.50 (Asymptomatic) | 98.70 (Symptomatic) 99.50 (Asymptomatic) | 2,039 | Hospital admissions |

| PCL Saliva RAT [8] | 67.00 | 75.00 | 320 | Suspected COVID-19 |

RT-PCR consistently demonstrates superior analytical sensitivity, capable of detecting minute quantities of viral RNA (as low as 100 copies/μL) [4]. In contrast, antigen tests exhibit substantially variable sensitivity (56-98%) but generally maintain high specificity (93-100%) when compared to the RT-PCR gold standard [9] [1].

Impact of Viral Load on Test Performance

The diagnostic sensitivity of antigen tests demonstrates a strong inverse correlation with cycle threshold (Ct) values, serving as a proxy for viral load.

Table 2: Antigen Test Sensitivity Stratified by RT-PCR Ct Values

| Ct Value Range | Viral Load Category | Antigen Test Sensitivity (%) | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤25 | High | 94.3-97.6 | [2] [3] |

| 21-25 | High-Intermediate | 63.0-72.8 | [2] [8] |

| 26-30 | Low-Intermediate | 2.9-70.8 | [8] [4] |

| >30 | Low | 2.9-47.2 | [3] [4] |

This relationship underscores a critical performance characteristic: antigen tests demonstrate optimal sensitivity during the acute phase of infection when viral loads are highest, typically within the first 5-7 days of symptom onset [9] [7]. One study noted that antigen test sensitivity decreased from 74% to 60% within 24 hours of symptom onset, contrasting with maintained RT-PCR sensitivity during this period [9].

Impact of Symptom Status

Symptomatic individuals generally present with higher viral loads, resulting in enhanced antigen test performance compared to asymptomatic carriers.

Table 3: Performance Comparison Between Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Individuals

| Performance Metric | Symptomatic Patients | Asymptomatic Patients | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antigen Test Sensitivity | 72.1% | 60.5% | [7] |

| False Negative Rate | 27.9% | 39.5% | [7] |

| PPV at 70% Prevalence | 86.36% | - | [8] |

The Quidel Sofia antigen test demonstrated 72.1% sensitivity in symptomatic patients compared to 60.5% in asymptomatic individuals [7]. This performance differential highlights the significant challenge antigen tests face in detecting pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic infections, which typically feature lower viral loads.

Methodological Approaches in Comparative Studies

Standardized Evaluation Protocols

Robust comparative studies follow standardized methodologies to ensure valid performance assessments:

Sample Collection and Handling:

- Paired nasopharyngeal swabs collected simultaneously from each participant

- Swabs placed in viral transport media and stored at 2-8°C if processed within 24-72 hours

- For antigen testing: Direct application of swab or VTM to test device

- For RT-PCR: RNA extraction from VTM using automated or manual systems [1] [6]

Testing Procedures:

- Antigen Tests: Performed according to manufacturer instructions, with results interpreted within specified timeframes (typically 15-30 minutes)

- RT-PCR: Extracted RNA amplified using approved kits with Ct value thresholds (generally <35-40 cycles) defining positivity [6] [5]

Data Analysis:

- Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) with 95% confidence intervals

- Statistical analysis using MedCalc, SPSS, or R software

- Correlation analysis between antigen levels and Ct values using Pearson's correlation coefficients [2] [3]

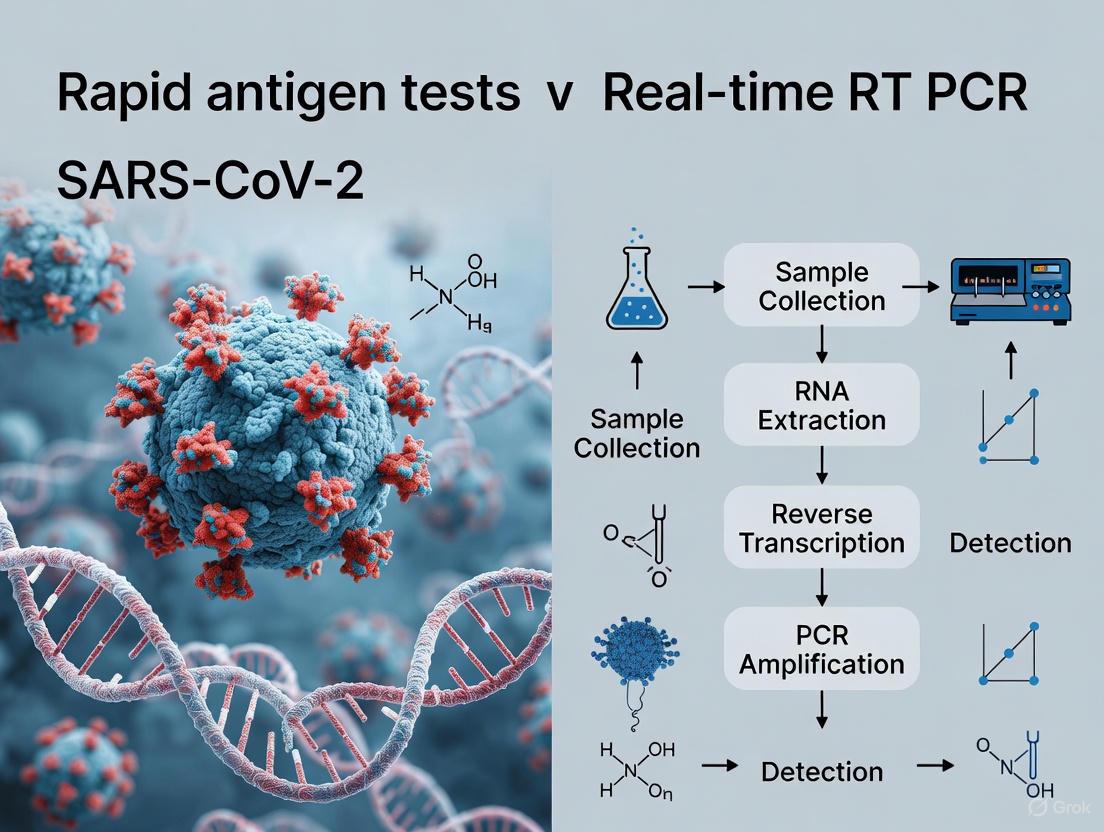

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the typical methodological workflow for comparative studies evaluating antigen and molecular assays:

Mechanistic Basis for Performance Differences

Fundamental Detection Principles

The performance disparities between antigen detection and nucleic acid amplification methods originate from their fundamental operational mechanisms:

Antigen Detection Limitations:

- Threshold Requirement: Requires sufficient viral protein concentrations (typically >10^4-10^5 copies/mL) to generate detectable signal

- No Amplification: Lacks target amplification capability, limiting detectability to higher viral loads

- Epitope Dependency: Dependent on antibody affinity and specificity; potential cross-reactivity or variant escape

- Protein Stability: Affected by protein degradation during transport or storage

Molecular Detection Advantages:

- Target Amplification: Exponential amplification (theoretically 2^n) enables detection of single RNA molecules

- Signal Amplification: Fluorogenic probes enhance detection sensitivity

- Target Conservation: Multiple target genes (N, E, RdRp, ORF1ab) reduce variant escape risk

- RNA Stability: RNA generally more stable than proteins in clinical specimens

Relationship Between Viral Load and Detection Probability

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic relationship between viral load and detection probability for both methods:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

| Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Antigen Tests | Standard Q COVID-19 Ag Test (SD Biosensor) | Qualitative detection of nucleocapsid antigen | Sensitivity: 98.3%, Specificity: 98.7% [1] |

| Zydus Cadila RAT | Lateral flow immunoassay for N protein | Sensitivity: 75.2%, Specificity: 98.9% [6] | |

| Automated Antigen Systems | VITROS SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test (CLIA) | Chemiluminescent immunoassay | Sensitivity: 94.3% (Ct≤25), 73.5% (overall) [2] |

| Lumipulse SARS-CoV-2 Ag Test (CLEIA) | Chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay | Sensitivity: 92.3%, strong inverse correlation with Ct (r=-0.93) [5] [3] | |

| Elecsys SARS-CoV-2 Ag (ECLIA) | Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay | Sensitivity: 72.4%, Specificity: 95% [4] | |

| RNA Extraction Kits | MagLEAD 12gC (PSS) MagMax Viral/Pathogen (Thermo Fisher) HighPure Complete (Roche) | Viral RNA purification from clinical specimens | Essential for RT-PCR sensitivity; automated platforms reduce processing time [1] [5] |

| RT-PCR Assays | Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay (Seegene) TaqPath COVID-19 RT-PCR (Thermo Fisher) RealStar SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR (Altona) | Multiplex real-time RT-PCR detection | Target multiple genes (E, RdRP, N, S); Ct<35-40 for positivity [1] [6] |

| Automated NAAT Systems | Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 (Cepheid) FilmArray Respiratory Panel (bioMérieux) | Integrated sample-to-answer NAAT testing | Sensitivity: 98-99%, Specificity: 100%, rapid turnaround (45min) [5] |

The comparative analysis of antigen detection immunoassays and nucleic acid amplification via RT-PCR reveals complementary diagnostic profiles with distinct advantages for specific applications. RT-PCR maintains its position as the gold standard for diagnostic sensitivity, capable of detecting low viral loads throughout the infection cycle, making it indispensable for confirmatory testing, asymptomatic screening, and situations requiring maximal sensitivity.

Antigen-based immunoassays offer distinct advantages in settings requiring rapid results, point-of-care testing, and high-throughput screening, particularly during the acute phase of infection when viral loads are highest. The strong correlation between antigen test sensitivity and viral load creates a valuable public health tool, as positive results frequently correlate with transmissible infections.

The optimal diagnostic strategy incorporates both methodologies within a structured testing algorithm that leverages their complementary strengths. This integrated approach enables effective pandemic control through rapid identification of potentially infectious individuals while maintaining the sensitivity required for comprehensive case detection and confirmation. Future developments in both technologies will likely focus on enhancing sensitivity of rapid tests while reducing complexity and turnaround time for molecular methods, further blurring the performance boundaries between these fundamental detection mechanisms.

The accurate and timely detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been a cornerstone of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the various diagnostic tools developed, real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has emerged as the undisputed gold standard. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of RT-PCR against rapid antigen tests, presenting experimental data and methodological protocols to elucidate the technical foundations of RT-PCR's superior performance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. While antigen tests offer advantages in speed and convenience, the analytical validity of RT-PCR remains unmatched for sensitive and specific detection of SARS-CoV-2, particularly in cases with low viral loads or asymptomatic presentations.

Performance Comparison: RT-PCR vs. Rapid Antigen Tests

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance Metrics of RT-PCR vs. Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs)

| Test Characteristic | RT-PCR | Rapid Antigen Tests | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sensitivity | 95.2% (95% CI: 86.7–98.3%) | 56.2% (95% CI: 29.5–79.8%) | [10] |

| Overall Specificity | 98.9% (95% CI: 97.3–99.5%) | 99.5% (95% CI: 98.1–99.9%) | [10] |

| Sensitivity in Asymptomatic Individuals | Gold Standard | 35.8% – 48.1% | [11] [10] |

| Detection Limit | ~4-6 copies/reaction (RT-ddPCR) | N/A | [12] |

| Impact of Viral Load (Ct Value) | Reliable across a wide range | Sensitivity drops significantly at Ct >25 and falls to 27-32% at Ct >30 | [13] [11] |

Table 2: Performance Variation of Antigen Tests with Viral Load

| Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value | Approximate Viral Load | RAT Sensitivity | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ct < 25 | High | 95% – 100% | [13] [11] |

| Ct 25 - <30 | Moderate | ~95% | [11] |

| Ct 30 - <35 | Low | 44.8% | [11] |

| Ct ≥ 35 | Very Low | 22.2% | [11] |

The data consistently demonstrates the superior sensitivity of RT-PCR. A Cochrane review confirmed that molecular tests like RT-PCR have an average sensitivity of 95.2%, drastically outperforming antigen tests, which have an average sensitivity of 56.2% [10]. This performance gap widens in asymptomatic individuals, where antigen test sensitivity can be as low as 35.8% to 48.1%, making them unreliable for screening populations without symptoms [11] [10]. The defining factor for this disparity is viral load. Antigen tests are only reliable when the viral load is high, typically during the symptomatic phase. As the cycle threshold (Ct) value increases (indicating lower viral load), the sensitivity of antigen tests plummets to as low as 22.2% [11].

Key Experimental Protocols

Understanding the experimental methodologies is crucial for interpreting performance data. Below are outlines of standard protocols for RT-PCR and rapid antigen test evaluations.

RT-PCR Methodology for SARS-CoV-2 Detection

Protocol 1: Standard RT-PCR Workflow for SARS-CoV-2

- 1. Sample Collection: Nasopharyngeal or nasal swabs are collected from patients and placed in universal viral transport medium [13] [12].

- 2. RNA Extraction: Viral RNA is extracted from the samples using commercial kits, such as the Zymo Quick Viral RNA Kit or the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). This purifies and concentrates the nucleic acids for amplification [13] [12].

- 3. Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR):

- The extracted RNA is added to a master mix containing reverse transcriptase, primers, probes, nucleotides, and buffer.

- Reverse Transcription: The single-stranded RNA genome is transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA).

- Real-Time Amplification: The cDNA is amplified through ~40 cycles of PCR. TaqMan probes labeled with a fluorophore and quencher bind to the target sequence. The fluorescence released during amplification is measured in real-time [13].

- 4. Result Interpretation: The cycle threshold (Ct) is determined. A positive result is indicated when the fluorescence exceeds a predetermined threshold within a certain number of cycles (e.g., <40) [13].

Advanced molecular methods like Droplet Digital RT-PCR (RT-ddPCR) offer absolute quantification without a standard curve and demonstrate even higher sensitivity for low viral loads. This method partitions the sample into thousands of droplets, performs PCR on each, and counts the positive droplets to absolutely quantify the target nucleic acid [12].

Rapid Antigen Test Evaluation Protocol

Protocol 2: Evaluating Rapid Antigen Test (RAT) Performance vs. RT-PCR

- 1. Study Design: A cross-sectional study is conducted where participants provide nasopharyngeal samples [13] [14].

- 2. Simultaneous Testing: The same sample or duplicate samples are tested simultaneously using the RAT and the reference standard RT-PCR.

- 3. Antigen Test Procedure: The sample is applied to the test cartridge, which contains labeled antibodies that bind to the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein. This complex migrates along the strip and is captured at the test line, producing a visual or digital signal within 10-30 minutes [11] [10].

- 4. Data Analysis: Diagnostic parameters are calculated using RT-PCR as the reference standard:

- Sensitivity = (True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)) × 100

- Specificity = (True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives)) × 100

- Positive and Negative Predictive Values (PPV, NPV) are also calculated, which are influenced by disease prevalence [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Example Product(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Viral RNA Extraction Kit | Purifies and concentrates viral RNA from clinical samples. | Zymo Quick Viral RNA Kit, RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) [13] [12] |

| One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for combined reverse transcription and PCR amplification. | Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay (Seegene), LabTurbo Multiplex RT-PCR Kit [13] [15] |

| SARS-CoV-2 Primers and Probes | Target-specific oligonucleotides for gene amplification and detection. Common targets include N, S, E, and ORF1ab genes. | Custom synthesized (e.g., Shanghai Sangon) [12] |

| Positive Control RNA | Quantified SARS-CoV-2 RNA used for assay validation, standard curve generation, and determining the limit of detection (LOD). | SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus Quantification Reference Material (Fantasiabio) [12] |

| Digital PCR Reagents | For absolute quantification of viral load without a standard curve. | One-Step RT-ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes (Bio-Rad) [12] |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The experimental data unequivocally establishes RT-PCR as the gold standard due to its high sensitivity and specificity, driven by its ability to amplify tiny amounts of viral genetic material. While rapid antigen tests are useful for quickly identifying individuals with high viral loads (and thus likely high transmissibility) in specific settings, their variable and often low sensitivity, particularly in asymptomatic cases, is a major limitation [16] [10]. A negative antigen test cannot rule out infection, especially when the clinical pretest probability is high.

The choice of diagnostic method must be aligned with the testing objective. RT-PCR is indispensable for confirmatory diagnosis, surveillance of emerging variants, and detection in low-prevalence or asymptomatic populations. Antigen tests, with their speed and lower cost, find utility in rapid screening and triage scenarios where immediate results are critical, albeit with an understanding of their higher risk of false negatives.

In the landscape of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics, RT-PCR remains the benchmark for accuracy. Its robust experimental methodology, high analytical sensitivity, and specificity provide reliable results across diverse clinical scenarios. Rapid antigen tests serve as a complementary tool but are hampered by significantly variable sensitivity, especially in low viral load situations. For researchers and clinicians, the evidence affirms that RT-PCR is the definitive choice when diagnostic accuracy is paramount, forming the foundation for effective clinical management, public health surveillance, and ongoing research into the virus and its variants.

The evaluation of any diagnostic test, including those for respiratory pathogens like SARS-CoV-2 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), relies on a standardized set of performance metrics compared against a reference standard. Sensitivity measures the test's ability to correctly identify infected individuals (true positive rate), while specificity measures its ability to correctly identify non-infected individuals (true negative rate). Positive Predictive Value (PPV) indicates the probability that a positive test result truly indicates infection, and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) indicates the probability that a negative test result truly indicates no infection. Accuracy represents the overall proportion of correct test results among all tests performed.

These metrics are particularly crucial when comparing different testing methodologies, such as rapid antigen tests and real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays. RT-PCR, with its ability to detect minute quantities of viral RNA, is widely considered the gold standard for detecting active SARS-CoV-2 infection due to its high analytical sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, rapid antigen tests (RATs) detect viral proteins and offer advantages in speed, cost, and deployment but may differ in their performance characteristics. Understanding these metrics allows researchers and clinicians to appropriately select, implement, and interpret tests based on the specific clinical or public health context.

Comparative Performance Data: Rapid Antigen Tests vs. RT-PCR

Extensive research has directly compared the performance of rapid antigen tests and RT-PCR across various populations and settings. The tables below summarize key findings from multiple studies investigating tests for SARS-CoV-2 and RSV.

Table 1: Performance of SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Tests Compared to RT-PCR

| Study Population & Context | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General symptomatic & asymptomatic (n=4,881) | 56.0 | 93.0 | Not reported | Not reported | [9] |

| Asymptomatic university students (n=692) | 63.5 (Overall); 35.0 (Asymptomatic) | 100.0 | 100.0 | Not reported | [17] |

| Asymptomatic individuals in Chile (n=842) | 69.9 | 99.6 | 94.4 | 97.2 | [18] |

| Symptomatic outpatients (n=928) | 87.4 (Overall); 96.5 (VL≥10⁶ copies/mL) | 100.0 | 100.0 | Not reported | [19] |

| Suspected cases & contacts in Thailand (n=454) | 98.3 | 98.7 | Not reported | Not reported | [1] |

| Evaluation of 18 different RATs | Varies by test | Varies by test | Varies by test | Varies by test | [20] |

Table 2: Performance of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Rapid Antigen Test Compared to Reference Methods

| Reference Method | Study Population | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex RT-PCR (n=557) | Pediatric | 46.4 | 99.3 | 95.6 | 84.7 | [21] |

| RT-qPCR (n=311) | Pediatric | 72.2 | 97.0 | 90.0 | 91.0 | [21] |

| Virus Culture (n=270) | Pediatric | 81.7 | 98.7 | 97.9 | 87.9 | [21] |

| RT-PCR & Virus Isolation (n=521) | Pediatric (<5 years) | 79.0 | 98.0 | 97.0 | 88.0 | [22] |

The data reveals that the sensitivity of rapid antigen tests is highly dependent on viral load. For SARS-CoV-2, when the viral load is high (often corresponding to a cycle threshold (Ct) value <25 in RT-PCR), the sensitivity of RATs can exceed 95% and even reach 100% in some studies [23] [19]. However, overall sensitivity is significantly lower in asymptomatic populations, who tend to have lower viral loads [18] [17]. Specificity is consistently high across most studies, meaning false positives are rare. For RSV, the BinaxNOW test showed variable but generally moderate sensitivity, which was lower in older children and when co-infections with other respiratory viruses were present [21].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The comparative data presented are derived from rigorous experimental protocols. A typical study design for evaluating a rapid antigen test against the gold standard RT-PCR involves the following key steps, also summarized in the workflow below.

Participant Recruitment and Sample Collection

Studies typically enroll a cohort of participants that may include symptomatic individuals, asymptomatic contacts of confirmed cases, or pre-operative patients to ensure a spectrum of viral loads [18] [1] [19]. Ethical approval and informed consent are mandatory. From each participant, paired samples are collected concurrently. The most common procedure involves a healthcare professional collecting two nasopharyngeal swabs. One swab is used immediately for the rapid antigen test, and the other is placed in viral transport medium (VTM) for RT-PCR analysis. Some study designs also include a self-collected saliva sample under supervision to evaluate an alternative sampling method for PCR [19].

Test Execution and Analysis

The rapid antigen test is performed on-site according to the manufacturer's instructions, often by staff blinded to the eventual PCR result. The result (positive or negative) is typically read visually within 15-30 minutes and recorded [18] [19]. The second swab in VTM is transported to a laboratory under refrigerated conditions. RNA is then extracted using automated platforms (e.g., MagLEAD 12gC, MagnaPureLC) and subjected to RT-PCR using approved kits (e.g., Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay, GenomeCov19 Detection Kit) [18] [1]. A sample is considered positive if the cycle threshold (Ct) value is below a predefined cutoff (usually Ct<40). Data analysis is performed by comparing the RAT results to the RT-PCR reference standard to calculate sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. Discrepant results (e.g., false negatives) are often further investigated by examining the Ct values, where a higher Ct indicates a lower viral load [9] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Diagnostic Test Comparison Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Products/Catalogs |

|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal Swabs | Sample collection from the nasopharynx. | Sterile, synthetic fiber swabs. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserves viral integrity during transport. | Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution with supplements. |

| Rapid Antigen Test Kits | For on-site, qualitative detection of viral antigens. | SD Biosensor Standard Q, Abbott Panbio, BinaxNOW [18] [17] [1]. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | Isolates viral nucleic acid from specimens. | MagLEAD 12gC kit, MagnaPure LC Total NA Isolation Kit [18] [22]. |

| RT-PCR Master Mix | Amplifies and detects viral RNA sequences. | Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay, COVITECH one-step RT-PCR kit [1] [24]. |

| Positive & Negative Controls | Validate test performance and reagent integrity. | Provided with commercial kits or sourced externally. |

The comparative analysis of diagnostic tests relies on a firm understanding of key performance metrics. The body of evidence demonstrates that while RT-PCR remains the gold standard for sensitivity, rapid antigen tests offer an excellent tool for specific applications, particularly when a rapid turnaround time is critical for public health interventions. Their performance is optimal in symptomatic individuals and those with high viral loads, who are also most likely to be contagious. The choice between these diagnostic methodologies should be guided by the specific context, including the prevalence of disease, the resources available, and the intended use of the test results—whether for individual patient diagnosis or broad community surveillance.

The accurate and timely detection of SARS-CoV-2 infection has been a cornerstone of the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) remains the gold standard for diagnostic confirmation, Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) have emerged as a vital tool for mass screening and rapid case identification due to their quick turnaround time, lower cost, and operational simplicity [25] [6]. This guide objectively compares the performance of RATs against RT-PCR, aggregating data from multiple meta-analyses and clinical studies to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive overview of their diagnostic accuracy. The focus is on presenting consolidated quantitative data on sensitivity and specificity, detailing the experimental methodologies that generate this evidence, and identifying key factors influencing test performance.

Aggregated findings from meta-analyses and cross-sectional studies provide a high-level overview of RAT performance against the RT-PCR gold standard. The following table synthesizes key metrics from multiple studies, illustrating the range of observed performance.

Table 1: Aggregated Performance Metrics of Rapid Antigen Tests vs. RT-PCR

| Study / Meta-Analysis | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Number of Studies / Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis (2022) [25] | 69% (68-70) | 99% (99-99) | Not specified | Not specified | 60 studies |

| Cross-Sectional Study, Brazil (2025) [26] | 59% (56-62) | 99% (98-99) | 97% | 78% | 2,882 samples |

| Hospital-Based Study, India (2023) [27] | 85.3% | 99.5% | Not specified | Not specified | 1,000 samples |

| Prospective Study, Greece (2023) [28] | 96.1% (91.1-98.7) | 100% (99.4-100.0) | 100% | 99.2% | 782 samples |

| Retrospective Study, Singapore (2024) [29] | 84.6% (83.3-85.7) | 99.4% (99.1-99.6) | Not specified | Not specified | 8,620 encounters |

The data reveals a range of sensitivities, from 59% to 96.1%, while specificity remains consistently high (≥99% in most studies) [25] [26] [27]. This variation underscores that while a negative RAT result may sometimes require confirmation, a positive result is highly reliable for identifying SARS-CoV-2 infection. The meta-analysis of 60 studies consolidates this view, showing a pooled sensitivity of 69% and a pooled specificity of 99% [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The performance data presented above are derived from rigorous comparative studies. The following workflow outlines the standard methodology for a head-to-head comparison of RAT and RT-PCR.

The core components of these experimental protocols are detailed below.

Participant Recruitment and Sample Collection

Studies typically enroll participants presenting with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 or those identified as contacts of confirmed cases [26] [6] [28]. For each participant, two nasopharyngeal swabs are collected simultaneously by trained healthcare personnel. The use of paired swabs from the same individual at the same time is critical for a direct, head-to-head comparison of the two testing methods, eliminating variability that could arise from sampling at different times or from different anatomical sites [6] [28].

Index Test: Rapid Antigen Test (RAT)

One swab is immediately tested at the point-of-care using the specified RAT kit, which operates on a lateral flow immunoassay principle. These tests are designed to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. The test procedure involves placing the swab into an extraction buffer tube, mixing it, and then applying a few drops of the solution to the test device. Results are interpreted visually within 15-30 minutes, as per the manufacturer's instructions [27] [6] [28]. The entire process is performed without the need for complex laboratory equipment.

Reference Standard: Real-Time RT-PCR

The second swab is placed in Viral Transport Medium (VTM) and transported to a laboratory under a controlled cold chain (typically 4°C) [27] [6]. Viral RNA is extracted using automated, magnetic bead-based nucleic acid extraction systems [6] [30]. The RT-PCR reaction targets at least two SARS-CoV-2 genes (commonly the E, N, RdRp, or ORF1ab genes) [27] [30]. A sample is considered positive if the amplification curve crosses the threshold for one or more targets within a pre-defined cycle threshold (Ct), usually below 35-40 cycles [27] [6]. The Ct value serves as a semi-quantitative proxy for viral load, with a lower Ct indicating a higher viral load [26] [30].

Statistical Analysis

The results are compiled into a 2x2 contingency table to calculate performance metrics:

- Sensitivity: Proportion of RT-PCR-positive cases that are correctly identified by the RAT (True Positives / [True Positives + False Negatives]).

- Specificity: Proportion of RT-PCR-negative cases that are correctly identified by the RAT (True Negatives / [True Negatives + False Positives]).

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV): Probability that a person with a positive RAT result is truly infected.

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV): Probability that a person with a negative RAT result is truly not infected. These measures, along with 95% confidence intervals, are calculated to quantify diagnostic accuracy [25] [26] [6].

Factors Influencing Test Performance

The diagnostic accuracy of RATs is not uniform but is influenced by several biological and technical factors. Understanding these is crucial for the correct interpretation of test results and for guiding test development.

Table 2: Key Factors Affecting Rapid Antigen Test Performance

| Factor | Impact on Sensitivity | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Load | Strongly positive correlation with higher viral load (lower Ct value). | Sensitivity was 90.85% for Cq<20 vs. 5.59% for Cq≥33 [26]. |

| Time Since Symptom Onset | Highest sensitivity in early infection (first 5-7 days). | Sensitivity decreased when testing ≥6 days from symptom onset [29]. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Variant | Minimal impact for major Omicron sublineages. | No significant difference in performance between BA.2, BA.5, and XBB.1 [29]. |

| Previous Infection | Potentially lower sensitivity in reinfections. | Reinfection cases had higher odds of RAT-negative/RT-PCR-positive results [29]. |

| Test Manufacturer | Performance varies between brands and kits. | Significant differences found between two widely used test kits in Brazil [26]. |

The relationship between these factors and the testing process is illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting rigorous evaluations of SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Brands/Types |

|---|---|---|

| Nasopharyngeal Swabs | Collecting patient samples from the nasopharynx. | Dacron or polyester flocked swabs [27]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preserving viral integrity during sample transport. | Commercially available VTM or Eswab [6] [30]. |

| Rapid Antigen Test Kits | Index test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. | Panbio, BinaxNOW, Flowflex, Standard Q, Zydus Cadila [25] [29] [6]. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolating viral RNA from VTM samples for RT-PCR. | Magnetic bead-based kits (e.g., MagMax) [26] [6] [30]. |

| RT-PCR Assays/Kits | Gold standard test for detecting SARS-CoV-2 RNA. | TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit, CDC 2019-nCoV RT-PCR Panel, Argene SARS-CoV-2 R-Gene [6] [28] [30]. |

| Positive Control Material | Ensuring the RT-PCR assay is functioning correctly. | Provided with commercial kits or sourced from organizations like the Pasteur Institute [30]. |

Rapid Antigen Tests are a highly specific and invaluable tool for the rapid identification of SARS-CoV-2, particularly in settings with high transmission or limited resources. Their primary limitation is variable and often modest sensitivity, which is strongly linked to viral load. Consequently, a negative RAT result may require confirmation with RT-PCR in individuals highly suspected of having COVID-19, especially those who are symptomatic or have a known exposure. For researchers and public health officials, these findings support the use of RATs as a screening tool for infectious individuals, who typically harbor high viral loads, while underscoring the importance of understanding the factors that modulate their performance to optimize testing strategies.

Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) have become a cornerstone in the management of the COVID-19 pandemic, offering rapid turnaround times and point-of-care usability. However, their diagnostic sensitivity is not uniform and is profoundly influenced by the viral load present in a patient sample, most commonly quantified through the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value derived from reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing. This review synthesizes evidence from clinical studies and meta-analyses to delineate the direct correlation between Ct values and RAT sensitivity. We demonstrate that RATs achieve high sensitivity (often >95%) in samples with low Ct values (high viral load), making them excellent tools for identifying infectious individuals. The article also provides a detailed overview of standard experimental protocols for evaluating RAT performance and offers visual tools and reagent references to support ongoing research and development in the field of rapid diagnostics.

The cycle threshold (Ct) value is a semi-quantitative measure derived from real-time RT-PCR assays, representing the number of amplification cycles required for a target gene's signal to cross a predefined detection threshold [31]. It exhibits an inverse logarithmic relationship with viral load; a lower Ct value indicates a higher quantity of viral RNA in the sample [31]. For example, a Ct value of 20 signifies a substantially higher viral load than a Ct value of 30.

While RT-PCR is exquisitely sensitive for detecting viral RNA, the detection of viral antigens via RATs requires a sufficient concentration of proteins, such as the nucleocapsid (N) protein, to generate a visible signal on a lateral flow assay [32]. This fundamental difference explains why the sensitivity of RATs is not a fixed value but is intrinsically linked to the viral load present in the sample. Individuals with high viral loads are not only more likely to test positive on a RAT but are also considered to be at the highest risk of transmitting the virus to others [33] [34]. Thus, understanding the interplay between Ct values and RAT sensitivity is critical for deploying these tests effectively in public health strategies and for interpreting their results in a clinical and research context.

Quantitative Data: The Correlation Between Ct Values and RAT Sensitivity

A substantial body of evidence confirms a strong, direct correlation between viral load (as indicated by Ct value) and the sensitivity of Rapid Antigen Tests. The relationship is consistently demonstrated across multiple studies and meta-analyses, which show RAT sensitivity peaks in samples with high viral loads and declines sharply as viral load decreases.

Table 1: Summary of RAT Sensitivity Across Different Ct Value Ranges

| Ct Value Range | Viral Load Category | Reported RAT Sensitivity | Source / Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 20 | Very High | 97.9% (95% CI: 96.9–98.9%) | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis [34] |

| < 25 | High | 90.6% (95% CI: 88.3–93.0%) | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis [34] |

| 91.67% | Boson RAT Evaluation (for Ct ≥30) [32] | ||

| 21-25 | Intermediate | 63% | PCL Spit RAT Study [8] |

| ≥ 25 | Low | 54.4% (95% CI: 47.3–61.5%) | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis [34] |

| 26-30 | Low | 22% | PCL Spit RAT Study [8] |

| ≥ 30 | Very Low | 18.7% (95% CI: 13.9–23.4%) | Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis [34] |

This quantitative relationship underscores a key performance characteristic of RATs: they are exceptionally good at identifying individuals who are most likely to be infectious. Research has shown that the mean Ct value for true positive RAT results is significantly lower (mean Ct ~22.2) than that for false negative results (mean Ct ~30.4) [34]. This indicates that false negatives predominantly occur in samples with lower viral loads, where the risk of transmission is also likely reduced.

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating RAT Performance

To generate the data presented above, researchers adhere to rigorous experimental designs that compare the performance of RATs against the gold standard, RT-PCR. The following outlines the key methodological components of such studies.

Subject Selection and Sample Collection

Studies typically enroll a cohort of participants that includes both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals suspected of SARS-CoV-2 infection [32] [8]. Informed consent is obtained, and paired samples are collected from each participant. The standard procedure involves:

- Sample Type: Collection of nasopharyngeal (NP), anterior nasal/mid-turbinate (AN/MT), or oropharyngeal swabs [32] [34]. Some studies also evaluate saliva samples [8].

- Paired Sampling: For direct comparison, two swabs are collected from the same individual at the same time. One swab is placed in Viral Transport Media (VTM) for RT-PCR analysis, and the other is used for the rapid antigen test immediately or placed in a specific buffer provided with the RAT kit [35].

Laboratory Methods: RT-PCR and Antigen Testing

RT-PCR Protocol

- RNA Extraction: Viral RNA is extracted from the VTM sample using commercial kits, such as the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit, often on automated platforms [32] [31].

- Amplification and Detection: The extracted RNA is amplified using real-time PCR kits targeting specific SARS-CoV-2 genes (e.g., E, N, RdRP). The process involves reverse transcription followed by 40-50 amplification cycles [32] [8]. The Ct value for each sample is recorded. A sample is considered positive if the Ct value is below a validated cutoff (e.g., <36 or <40, depending on the kit) [31] [8].

- Quality Control: Internal controls are included to monitor for PCR inhibition and ensure successful RNA extraction [32].

Rapid Antigen Test Protocol

- Test Execution: The second swab is processed according to the manufacturer's Instructions for Use (IFU). This typically involves placing the swab in an extraction buffer, rotating it to release the antigen, and then dispensing drops of the solution onto the test device [32] [1].

- Result Interpretation: Results are read visually after 15-20 minutes. The appearance of both control and test lines indicates a positive result. The tests are often performed blinded to the RT-PCR result to avoid bias [32].

- Data Analysis: The results are compiled into a 2x2 contingency table to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) against the RT-PCR reference standard [8] [35].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow of a typical comparative accuracy study.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The evaluation of RAT performance and the study of viral load dynamics rely on a suite of specific reagents and kits. The table below details essential materials and their functions in this field of research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for SARS-CoV-2 Detection Studies

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) | Viral RNA extraction from swab samples | Prepares purified RNA for downstream RT-PCR analysis [32] [36] |

| Allplex 2019-nCoV Assay (Seegene) | Multiplex real-time RT-PCR | Detects multiple SARS-CoV-2 genes (E, N, RdRP) and provides Ct values [1] |

| SacACE SARS-CoV-2 Test Kit | Real-time RT-PCR | Gold standard comparison for RAT evaluations, targeting E and N genes [32] |

| Standard Q COVID-19 Ag Test (SD Biosensor) | Rapid antigen detection | Lateral flow immunoassay for detecting SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein [1] [36] |

| Panbio COVID-19 Ag Test (Abbott) | Rapid antigen detection | Lateral flow immunoassay commonly evaluated in comparative studies [36] |

| Boson Rapid SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Test Card | Rapid antigen detection | A RAT evaluated for self-testing with high reported accuracy [32] |

| Viral Transport Media (VTM) | Preservation of specimen integrity | Maintains virus viability and nucleic acid integrity during sample transport [31] |

Discussion and Clinical Relevance

The inverse relationship between Ct values and RAT sensitivity has profound implications for public health strategy and clinical practice. The primary strength of RATs lies in their ability to rapidly identify individuals with high viral loads, who are most likely to be infectious. This makes them invaluable tools for mass screening in high-transmission settings, such as outbreaks, and for informing immediate isolation decisions [33] [34].

However, the lower sensitivity in individuals with high Ct values (low viral loads) is a critical limitation. This is particularly relevant for testing asymptomatic individuals, who may have lower viral loads on average, or for testing later in the course of illness when viral loads are declining [37] [34]. Therefore, a negative RAT result should not be used as a definitive rule-out in all scenarios, especially when clinical suspicion is high. Understanding this performance characteristic prevents the misinterpretation of results and guides the appropriate use of confirmatory RT-PCR testing.

Furthermore, the Ct value itself has demonstrated clinical prognostic value. Studies have shown that patients with lower Ct values (higher viral loads) were significantly more likely to require prescription drug therapy for COVID-19 than those with higher Ct values [31]. This highlights the potential utility of quantitative viral load assessment in patient management and risk stratification.

In the comparative performance analysis of rapid antigen tests versus RT-PCR, viral load, as quantified by Ct value, emerges as the paramount factor determining RAT sensitivity. The collective evidence demonstrates that RATs fulfill a specific and crucial niche: the efficient detection of highly infectious individuals. Their performance is optimized when viral loads are high (Ct values < 25), with sensitivity exceeding 90% in this range. Researchers and clinicians must therefore interpret RAT results within the context of viral load dynamics. Future developments in rapid diagnostics should focus on enhancing sensitivity without compromising speed and accessibility, potentially through improved antibody affinity or novel detection technologies. For now, a clear understanding of the critical role of viral load ensures that RATs can be deployed and interpreted effectively within a comprehensive diagnostic and public health framework.

Strategic Deployment in Research and Clinical Practice: Contextual Test Selection

The comparative analysis of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) detection methods reveals a complex performance landscape where Rapid Antigen Diagnostic Tests (Ag-RDTs) and real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) serve complementary roles. While RT-PCR remains the gold standard for diagnostic sensitivity due to its ability to detect minute viral RNA quantities, extensive research demonstrates that Ag-RDTs provide substantial value in specific use cases where speed, cost, and operational simplicity are paramount. The strategic deployment of each technology must be informed by their documented performance characteristics across different viral loads, patient populations, and operational environments.

Recent multi-study analyses indicate that Ag-RDTs achieve optimal sensitivity (approaching 100%) in patients with high viral loads, typically corresponding to RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values below 25 [23] [38] [8]. This high viral load state frequently correlates with peak transmissibility, positioning Ag-RDTs as valuable tools for identifying infectious individuals during the most contagious phase of infection. The performance differential between these methodologies narrows significantly in symptomatic individuals and during early infection when viral concentrations are highest, supporting the targeted application of Ag-RDTs for rapid triage and mass screening initiatives.

Comparative Performance Data Analysis

Comprehensive Performance Metrics Across Studies

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Ag-RDTs Versus RT-PCR Across Multiple Studies

| Study & Setting | Samples (n) | Overall Sensitivity | Overall Specificity | Sensitivity at Ct<25 | Sensitivity at Ct>30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lahore, Pakistan (2024) [8] | 320 | 67.0% | 75.0% | 100% | 22.0% |

| Mali, Africa (2023) [38] | 390 | 57.1-61.9% | 94.1-95.8% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Comparative Study (2024) [23] | 268 | 76.5-80.3% | 96.8-97.3% | 100% | 27.3-31.8% |

| Resource-Limited RDT (2021) [39] | 80 | 87.5% | 100% | Not specified | Not specified |

The aggregated data reveals a consistent performance pattern across diverse geographical settings and study designs. Ag-RDTs demonstrate strong specificity (generally >90%), ensuring false positives remain low [23] [38] [39]. However, sensitivity shows considerable variation, heavily dependent on viral load as approximated by RT-PCR Ct values. This fundamental relationship between viral concentration and detection capability underpins the strategic deployment recommendations for Ag-RDTs in specific use cases.

Variant-Specific Performance

Table 2: Ag-RDT Sensitivity by SARS-CoV-2 Variant

| Variant | FIA Sensitivity | LFIA Sensitivity | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | 78.9% | 69.2% | [23] |

| Delta | 72.2% | 83.3% | [23] |

| Omicron | 100% | 100% | [23] |

Variant-specific performance data indicates that Ag-RDTs maintain effectiveness across variants of concern, with particularly strong performance against the Omicron variant [23]. This consistent detection capability supports the ongoing utility of Ag-RDTs despite viral evolution, though continuous monitoring remains necessary as new variants emerge.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Comparative Evaluation Protocol

The foundational methodology for comparing Ag-RDT and RT-PCR performance follows a standardized approach employed across multiple studies [23] [38] [8]:

Sample Collection: Simultaneous collection of nasopharyngeal, anterior nasal, or oropharyngeal swabs from participants. Swabs are placed in viral transport medium for RT-PCR analysis or directly applied to Ag-RDT devices according to manufacturer specifications.

RT-PCR Reference Testing: RNA extraction using commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen QIAamp Viral RNA mini kit). RT-PCR amplification using approved platforms (e.g., Bosphore Novel Coronavirus Detection Kit v4) with Ct value cut-offs typically set at ≤33-36 for positive classification [38] [8]. Target genes include nucleocapsid (N), envelope (E), and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp).

Ag-RDT Execution: Direct application of swab samples or swab extracts to lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA) or fluorescence immunoassay (FIA) devices. Visual or instrumental reading at 15-30 minutes following manufacturer guidelines.

Viral Load Quantification: Ct values from RT-PCR serve as proxy for viral load. Stratification of samples by Ct ranges (<20, 21-25, 26-30, >30) enables correlation of Ag-RDT sensitivity with viral concentration.

Statistical Analysis: Calculation of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and overall accuracy with 95% confidence intervals. Cohen's kappa coefficient determination to assess agreement between methods.

Specialized Protocol for Resource-Limited Settings

Studies focused on resource-limited environments implement modified protocols to address operational constraints [38] [39]:

Point-of-Care Adaptation: Training of healthcare workers or laboratory personnel without specialized molecular biology expertise to perform Ag-RDTs and interpret results visually.

Sample Processing Simplification: Anterior nasal swabs instead of nasopharyngeal swabs to improve patient tolerance and simplify collection. Direct application of swabs to extraction buffer without intermediate processing steps.

Decentralized Testing Model: Evaluation of Ag-RDT performance at primary health centers without reliable cold chain infrastructure. Assessment of stability under variable temperature and humidity conditions.

Control Measures: Incorporation of positive and negative control swabs to verify test integrity in challenging environments.

High-Value Application Domains

Mass Screening Initiatives

Ag-RDTs provide distinct advantages in mass screening scenarios where testing throughput, speed, and frequency outweigh the need for maximum sensitivity [23] [39]. The 15-30 minute time-to-result enables immediate action, while the minimal infrastructure requirements facilitate deployment in non-traditional testing venues such as workplaces, schools, and community centers.

The operational characteristics of Ag-RDTs align with the epidemiological understanding that individuals with high viral loads (Ct<25) drive the majority of transmission events [23]. By reliably identifying these highly infectious individuals, Ag-RDT-based screening programs can effectively interrupt transmission chains despite reduced sensitivity in low viral load cases. The cost-benefit analysis favors frequent Ag-RDT screening over infrequent RT-PCR testing for outbreak containment.

Resource-Limited Settings

In environments with constrained laboratory infrastructure, reagent supply chain challenges, or limited technical expertise, Ag-RDTs offer a pragmatic diagnostic solution [38] [39]. Studies in Mali demonstrated that although Ag-RDT sensitivity (57.1-61.9%) was lower than optimal, the tests still provided substantial value in triaging symptomatic patients and monitoring known positive cases during treatment [38].

The minimal equipment requirements (no electricity, temperature control, or sophisticated instrumentation) and ease of training make Ag-RDTs particularly suitable for remote or underserved regions. The operational model proposed for these settings often incorporates Ag-RDTs as frontline tests with RT-PCR confirmation reserved for negative results in high-probability cases, thereby optimizing resource allocation [39].

Rapid Triage Scenarios

In clinical settings where immediate disposition decisions are required, Ag-RDTs enable effective patient triage based on infectious status [23] [40]. Emergency departments, urgent care facilities, and preoperative screening programs benefit from the rapid exclusion of high viral load SARS-CoV-2 infections, permitting appropriate infection control measures.

The high specificity of Ag-RDTs (>90% across most studies) ensures that positive results can be acted upon with high confidence, facilitating immediate isolation precautions [23] [38]. The superior sensitivity of Ag-RDTs in symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients (80.25% vs 73.68% for FIA) further supports their application in triaging individuals with clinical manifestations consistent with COVID-19 [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Comparative Test Evaluation

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer/Provider | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARGENE SARS-CoV-2-R-GENE | BioMérieux | RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 | Targets N and E genes; used as reference standard [38] |

| Bosphore Novel Coronavirus Detection Kit v4 | Anatolia Turkiye | RT-PCR amplification | Ct value cut-off of 36 for positivity determination [8] |

| GF-1 Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Vivantis | RNA extraction from swab samples | Compatible with various viral transport media [8] |

| PCL Spit Rapid Antigen Test | PCL (Germany) | SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid detection | Saliva-based; used in Pakistan study [8] |

| Standard Q COVID-19 Ag | SD Biosensor | Lateral flow antigen detection | Evaluated in Mali study; 94.1% specificity [38] |

| Realy Tech COVID-19 Ag | Hangzhou Realy Tech | Fluorescent immunoassay | Higher sensitivity in asymptomatic cases [23] |

| Viral Transport Medium | Various | Sample preservation and transport | Maintains viral integrity during transport [38] |

| Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid | Bio-Techne | Positive control for assay validation | Sf21 (baculovirus)-derived; Met1-Ala419 [39] |

The comprehensive analysis of Ag-RDT versus RT-PCR performance supports a nuanced implementation strategy based on specific use case requirements rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. Ag-RDTs deliver maximum value in scenarios prioritizing speed, accessibility, and operational simplicity, particularly when targeting individuals with high viral loads who represent the greatest transmission risk. The documented performance characteristics—high specificity, excellent detection capability at Ct values <25, and minimal infrastructure requirements—position Ag-RDTs as indispensable tools for mass screening, resource-limited settings, and rapid triage applications.

RT-PCR maintains its essential role in confirmatory testing, asymptomatic screening, and situations demanding maximum diagnostic sensitivity. The strategic integration of both technologies within a coherent public health framework—leveraging their complementary strengths—represents the optimal approach to SARS-CoV-2 detection and outbreak control. Future development efforts should focus on enhancing Ag-RDT sensitivity without compromising their operational advantages, particularly for use in low-prevalence settings and asymptomatic screening programs.

The comparative performance of SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) versus real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) has been a critical area of research throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. While both methods aim to detect active infection, their fundamental differences in technology, sensitivity, and operational characteristics lead to varying performance across different patient populations. A key factor influencing test accuracy is the patient's symptom status, with numerous studies demonstrating significantly different performance in symptomatic versus asymptomatic individuals. This review synthesizes evidence from multiple clinical studies to provide a structured comparison of test performance across these distinct populations, offering researchers and clinicians a data-driven foundation for test selection and interpretation in both diagnostic and screening contexts.

Table 1: Summary of RAT Performance in Symptomatic vs. Asymptomatic Populations

| Study Population & Setting | Sample Size | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic Individuals | ||||||

| University Campuses, Wisconsin | 227 | 80.0 | 98.9 | 94.1 | 95.9 | [41] |

| Hospital Patients, Ethiopia | 200* | 95.0 | 97.0 | N/R | N/R | [42] |

| Various Settings, India | 329 | 75.2 | 98.9 | 98.3 | 82.8 | [6] |

| Asymptomatic Individuals | ||||||

| University Campuses, Wisconsin | 871 | 41.2 | 98.4 | 33.3 | 98.8 | [41] |

| Community Screening, Chile | 842 | 69.9 | 99.6 | 94.4 | 97.2 | [18] |

| Hospital/Community, India | 329 | Lower in asymptomatic* | 98.9 | 98.3 | 82.8 | [6] |

| Note: PPV = Positive Predictive Value; NPV = Negative Predictive Value; N/R = Not Reported. *This study included a mixed population; the sensitivity was notably higher in symptomatic versus asymptomatic participants, though a precise split was not provided in the abstract. The Ethiopian study primarily focused on confirmed COVID-19 patients, and while symptom status is not detailed in the abstract, the high sensitivity suggests a cohort with a high viral load. |

Table 2: Impact of Viral Load (Cycle Threshold Values) on RAT Sensitivity

| RT-PCR Cycle Threshold (Ct) Value Range | Viral Load Category | RAT Sensitivity (%) | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 20 | High | 100.0 | Lahore, Pakistan [8] |

| 21 - 25 | Intermediate | 63.0 | Lahore, Pakistan [8] |

| > 26 | Low | 22.0 - 36.1 | Lahore, Pakistan [8], Iquique, Chile [18] |

Experimental Insights and Methodologies

Key Comparative Study Designs

The data presented in the summary tables are derived from rigorous comparative studies. A typical protocol involved collecting paired nasopharyngeal swabs from each participant. One swab was tested immediately using a RAT, often at the point of care, while the second swab was placed in viral transport media (VTM) and transported under refrigeration (typically 4°C) to a laboratory for RNA extraction and RT-PCR analysis [18] [6]. For example, the study in Chile with 842 asymptomatic individuals used the SD Biosensor RAT and compared it with RT-PCR using the GenomeCov19 Detection Kit, with a cycle threshold (Ct) value ≤ 40 considered positive [18]. This parallel testing design allows for a direct head-to-head comparison of the two methods, using RT-PCR as the reference standard.

The Relationship Between Viral Load, Symptoms, and Test Sensitivity

A consistent finding across studies is the inverse correlation between RT-PCR Ct values and RAT sensitivity. The Ct value represents the number of amplification cycles required for the viral RNA to reach a detectable level; a lower Ct value indicates a higher viral load [43]. Research from Pakistan clearly demonstrated this relationship, showing RAT sensitivity was 100% for samples with Ct ≤ 20, but dropped to 22% for samples with Ct > 26 [8]. This is a critical factor explaining the performance difference between symptomatic and asymptomatic populations. Symptomatic individuals typically have higher viral loads and lower Ct values, making them more likely to be detected by RATs, which require a substantial amount of viral protein to generate a positive signal [10] [41]. Asymptomatic individuals often have lower viral loads, leading to a higher rate of false-negative RAT results despite a positive RT-PCR.

Diagram 1: The relationship between symptom status, viral load, and resulting Rapid Antigen Test (RAT) performance. Symptomatic status is frequently associated with higher viral loads, leading to higher RAT sensitivity.

Implications for Test Interpretation and Public Health Strategy

The documented performance differences have profound implications for how test results are interpreted and how testing is deployed in public health strategy. The pretest probability of infection—influenced by symptom status, known exposures, and community prevalence—is a crucial factor in interpreting a RAT result [10] [44]. For a symptomatic individual or a close contact of a confirmed case (high pretest probability), a negative RAT result should be viewed with caution, and confirmatory RT-PCR testing is often recommended [10] [41]. Conversely, a positive RAT in an asymptomatic person with no known exposures (low pretest probability) may also require RT-PCR confirmation due to the lower positive predictive value in this group [44] [41]. These considerations are vital for researchers designing surveillance studies and for health officials allocating limited testing resources, as RATs offer advantages in speed and cost for mass screening, despite their lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers [18] [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for SARS-CoV-2 Test Performance Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Manufacturers/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Transport Media (VTM) | Preserves specimen integrity during transport for RT-PCR. | HiMedia [6] |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolates viral RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs for RT-PCR. | Mag-Bind Viral DNA/RNA 96 Kit (Omega Bio-Tek), Mag Max Viral/Pathogen Kit (Thermo Fisher) [18] [6] |

| RT-PCR Master Mixes | Detects and amplifies specific SARS-CoV-2 gene targets. | GenomeCov19 Detection Kit (ABM), TaqPath COVID-19 RT-PCR Kit (Thermo Fisher), Bosphore Novel Coronavirus Detection Kit [18] [8] [6] |

| Rapid Antigen Test Kits | For point-of-care detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. | SD Biosensor Standard Q, Zydus Cadila RAT, PCL Spit Rapid Antigen Test, Sofia SARS Antigen FIA (Quidel) [18] [6] [41] |

| Positive Control Material | Validates RT-PCR assay performance and standard curve generation. | 2019-nCoV N Positive Control (IDT) [45] |

Substantial and consistent evidence confirms that the performance of SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Tests is markedly different in symptomatic versus asymptomatic populations. The significantly higher sensitivity observed in symptomatic individuals is closely tied to their correspondingly higher viral loads. While RATs offer immense value for rapid screening and are highly specific, researchers, clinicians, and public health officials must account for these performance limitations, particularly when deploying them for asymptomatic screening. The choice between RAT and RT-PCR should be guided by the testing objective: RATs are excellent for quickly identifying infectious individuals in high-prevalence or high-pretest probability settings, whereas RT-PCR remains the unrivaled gold standard for diagnostic confirmation and detection of low viral loads in surveillance or low-prevalence scenarios.

The continuous evolution of SARS-CoV-2 has presented significant challenges to COVID-19 diagnostic strategies. The emergence of the Omicron variant and its sublineages, characterized by an unprecedented number of mutations, has raised critical questions regarding the reliability of both rapid antigen tests (Ag-RDTs) and molecular methods like real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). This guide provides a systematic comparison of diagnostic test performance, focusing on the differential detection of Delta and Omicron variants. We synthesize experimental data and analytical evaluations to offer researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals evidence-based insights into diagnostic shifts in the face of viral evolution, framing this within the broader thesis of Ag-RDT versus RT-PCR comparative performance.

The table below summarizes the core findings from recent studies evaluating diagnostic test performance across SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Table 1: Summary of Diagnostic Test Performance Across Variants

| Study Focus | Key Comparative Finding | Variant-Specific Performance Notes | Primary Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag-RDT Clinical Sensitivity (Meta-Analysis) | Pooled sensitivity: 67.1% for Omicron [46]. | Performance is highly dependent on viral load; sensitivity drops significantly at Ct values >25 [46]. | Systematic review & meta-analysis of 18 studies [46]. |

| Ag-RDT vs. PCR (Serial Testing) | No statistically significant difference in Ag-RDT sensitivity between Delta and Omicron was found [47]. | Sensitivity on the same day as first positive PCR was low for both (Delta: 15.5%, Omicron: 22.1%), improving with serial testing [47]. | Prospective cohort study (n=207 PCR-positive) [47]. |

| Ag-RDT Analytical Sensitivity | Marked heterogeneity exists among different Ag-RDT brands for detecting Omicron BA.4/BA.5 [48] [49]. | Up to 443-fold higher viral load required for the worst-performing RAT vs. the best-performing one for BA.4 [48] [49]. | Retrospective lab evaluation of 10 RATs (n=171 swabs) [48] [49]. |

| RT-PCR for Variant Identification | Specific RT-PCR assays can accurately differentiate VOCs, serving as a surrogate for sequencing [50]. | Assays targeting mutations (e.g., K417N, E484-, N501Y for Omicron; L452R for Delta) showed 100% accuracy versus sequencing [50]. | Laboratory evaluation of multiplex RT-PCR on 100 positive swabs [50]. |

Comparative Performance Data: Antigen Tests vs. RT-PCR

A comprehensive meta-analysis of 18 studies concluded that the pooled sensitivity of Ag-RDTs for the Omicron variant was 0.671 (95% CI: 0.595-0.721), while specificity remained high at 1.000 (95% CI: 0.997-1.000) [46]. This confirms that while Ag-RDTs are excellent for ruling out non-infected individuals, their ability to confirm infection (sensitivity) is moderate and can be influenced by the viral variant and other factors.

Impact of Viral Load

The most critical factor affecting Ag-RDT sensitivity is viral load, inversely correlated with RT-PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values. The performance disparity between Ag-RDTs and RT-PCR becomes most apparent in samples with low to medium viral loads.

Table 2: Ag-RDT Performance Based on Viral Load (Ct Values) for Omicron

| Ct Value Range | Viral Load Category | Ag-RDT True Positive Rate Range | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 25 | Very High | 94.3% to 34.3% | [48] [49] |

| 25 - 30 | High / Medium | 25.6% to 0% | [48] [49] |

| > 30 | Low | Very low to negligible | [46] |

One study noted that only 7.2% of individuals who were RT-PCR-positive for less than 48 hours tested positive via Ag-RDT within a week, highlighting the lag in Ag-RDT detectability during early infection [47].

Variant-Specific Performance

While early reports suggested Ag-RDTs had lower sensitivity for Omicron, larger controlled studies offer a more nuanced view. A secondary analysis of a large prospective cohort in the U.S. found no statistically significant difference in Ag-RDT sensitivity between Delta and Omicron variants, whether tested on the same day as the first positive PCR or 48 hours later [47]. The study emphasized that serial testing improves the sensitivity of Ag-RDTs for both variants [47].

However, a major challenge is the significant heterogeneity between different Ag-RDT brands. An independent laboratory evaluation of ten commonly used tests revealed vast differences in their ability to detect Omicron BA.4 and BA.5. The 50% limit of detection (LoD50) varied considerably, requiring up to 443-fold (for BA.4) and 56-fold (for BA.5) higher RNA copy numbers for the worst-performing test compared to the best [48] [49]. This indicates that the choice of brand is a critical variable when assessing overall Ag-RDT performance against Omicron.

Experimental Protocols for Diagnostic Evaluation

Protocol for Evaluating Ag-RDT Clinical Sensitivity

Objective: To determine the clinical sensitivity and specificity of rapid antigen tests (Ag-RDTs) against SARS-CoV-2 variants in comparison to RT-PCR.

Methodology Overview: This protocol is based on a prospective longitudinal cohort study design [47].

- Study Population & Sampling: Asymptomatic or symptomatic individuals are enrolled. Participants self-collect anterior nasal swabs every 48 hours for a period of 15 days.

- Sample Processing: For each testing time point, two swabs are collected. One swab is used for the Ag-RDT immediately, following the manufacturer's instructions. The second swab is placed in viral transport medium (VTM) and shipped to a central laboratory for RT-PCR analysis.

- Reference Testing: RT-PCR is performed using a validated assay (e.g., Roche cobas SARS-CoV-2 assay). Cycle threshold (Ct) values for target genes (e.g., the E gene) are recorded as a surrogate for viral load.

- Variant Determination: Variant assignment is performed via whole-genome sequencing or variant-specific PCR on RT-PCR-positive samples. Cut-off dates based on local variant prevalence or sequencing results can be used for classification [47].

- Data Analysis: Ag-RDT results are compared to RT-PCR results for each matched sample. Sensitivity is calculated as (Number of true positives / (Number of true positives + Number of false negatives)) * 100. Analysis is stratified by variant and viral load (Ct value).

Protocol for Evaluating Ag-RDT Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

Objective: To assess and compare the analytical sensitivity (Limit of Detection, LoD) of various Ag-RDTs for specific SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Methodology Overview: This protocol is based on a retrospective in vitro laboratory study [48] [49].

- Sample Panel Creation: A panel of characterized respiratory swab samples is created from SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR-positive patients. Samples are selected to cover a range of viral loads (e.g., Ct values from 17 to 36) and are confirmed for their variant (e.g., BA.4, BA.5) using variant-specific PCR.

- Test Execution: A defined volume (e.g., 50 µL) of the virus-containing transport medium from each characterized sample is applied to each Ag-RDT under evaluation by trained staff, following a standardized operating procedure to minimize variability. The tests are performed in a blinded manner regarding the viral load and variant.

- Result Interpretation: After the manufacturer-specified incubation time (e.g., 15 minutes), the tests are read under consistent lighting conditions. Any visible test line, regardless of intensity, is considered positive.

- Data Analysis: The 50% limit of detection (LoD50) is determined, representing the viral load (in RNA copies per test) at which 50% of the test replicates return a positive result. The LoD50 values are compared across different Ag-RDTs and variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the cited studies for evaluating SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic tests.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior Nasal Swabs | Sample collection from study participants. | Used for both self-testing Ag-RDTs and sample collection for RT-PCR [47]. |

| Viral Transport Medium (VTM) | Preservation of virus viability and nucleic acids during transport. | Used to store swabs destined for central lab RT-PCR testing [47] [49]. |

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality viral RNA from clinical samples. | e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Kits used on QIAcube platform [50]. Critical for reliable RT-PCR results. |

| RT-PCR Master Mixes | Amplification and detection of viral RNA targets. | Contains reverse transcriptase, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers. Often include probes for real-time detection [51]. |

| Variant-Specific PCR Assays | Rapid presumptive identification of SARS-CoV-2 variants. | e.g., Seegene Allplex SARS-CoV-2 Variants II Assay, Clonit COVID-19 Ultra Variant Catcher. Target key spike mutations [50]. |