Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) in Bioinformatics: A Guide to Robust Gene Selection for Disease Prediction

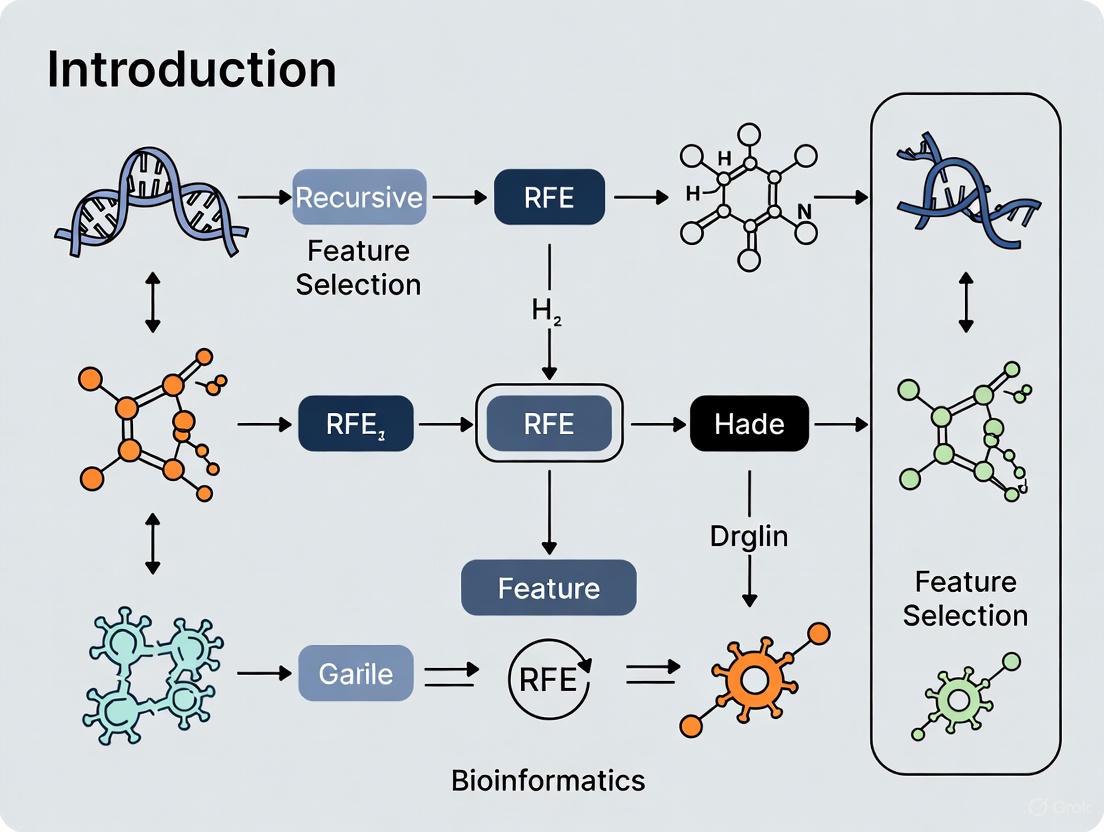

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for feature selection in bioinformatics, specifically tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) in Bioinformatics: A Guide to Robust Gene Selection for Disease Prediction

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for feature selection in bioinformatics, specifically tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of RFE and its critical role in overcoming the 'curse of dimensionality' in genomic datasets, such as those from GWAS. The scope includes a detailed walkthrough of methodological implementation using popular libraries like scikit-learn, best practices for troubleshooting and optimizing RFE to handle computational costs and feature correlation, and a comparative analysis with other feature selection methods like Permutation Feature Importance. The article synthesizes insights from real-world applications in cancer diagnosis and biomarker discovery, offering a practical resource for building more accurate, interpretable, and generalizable predictive models in biomedical research.

Why Feature Selection is Paramount in Bioinformatics: Tackling High-Dimensional Data with RFE

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has revolutionized genomic research but simultaneously introduced the profound challenge known as the "curse of dimensionality." This phenomenon, characterized by datasets where the number of features (p) drastically exceeds the number of samples (n), plagues everything from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to machine learning applications in bioinformatics. This technical guide examines the impact of high-dimensional genomic data, where the exponential increase in feature volume can lead to model overfitting, unreliable parameter estimates, and heightened computational costs. We explore strategic responses to this challenge, with a focused examination of feature selection methodologies, particularly Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), as a critical pathway to robust biological discovery. By integrating current research and experimental protocols, this review provides a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate the complexities of genomic data analysis, enhance model interpretability, and accelerate the translation of genomic insights into therapeutic innovations.

In biomedical research, the shift toward data-intensive science has resulted in an exponential growth in data dimensionality, a trend characterized by the simple formula: D = S * F, where the volume of data generated (D) increases in both the number of samples (S) and the number of sample features (F) [1]. Genomic studies epitomize this "Big Data" challenge, frequently generating datasets with tens of thousands to millions of features—such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or gene expression values—from a limited number of biological samples. This creates a "p >> n" problem, where the feature space massively dwarfs the sample size.

The "curse of dimensionality," a term first introduced by Bellman in 1957, describes the problems that arise when analyzing data in high-dimensional spaces [1]. In genomics, this high-dimensional environment complicates many modeling tasks, leading to several critical issues:

- Overfitting: Models may fit noise or spurious correlations in the training data, impairing generalizability to new data.

- Increased Computational Burden: Longer computation times and greater memory requirements.

- Decreased Model Performance: Redundant or irrelevant features can dilute the predictive power of models [1] [2].

- Problems with Statistical Inference: Accurate parameter estimation becomes difficult, and multiple testing corrections may fail due to underlying feature dependencies, increasing Type I error rates [2].

Consequently, reducing data complexity through feature selection (FS) has become a non-trivial and crucial step for credible data analysis, knowledge inference using machine learning algorithms, and data visualization [1].

The Impact of High Dimensionality on Genomic Analysis

Challenges in Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and Genomic Selection

In GWAS and genomic selection (GS), high-dimensionality presents significant hurdles. While GS technology represents a paradigm shift from "experience-driven" to "data-driven" crop breeding, the surge in available SNP markers—from 9K to over 600K in wheat—introduces the "curse of dimensionality" [3]. When the number of markers far exceeds the sample size, models become prone to overfitting, and computational costs increase exponentially [3]. Redundant markers can lead to "noise amplification," where random fluctuations of non-associated SNPs mask genuine association signals.

Challenges in Transcriptomics and Machine Learning

Transcriptome data, such as from RNA-sequencing experiments, also suffers from the "curse of dimensionality," as tens of thousands of genes are profiled from a limited number of subjects [4]. This high-dimensional landscape makes it challenging to identify consistent disease-related patterns amidst technical and biological heterogeneity. For machine learning-based classification, in a multidimensional space, many data points can lie near the true class boundaries, leading to ambiguous class assignments [2].

Table 1: Summary of Challenges Posed by High-Dimensional Genomic Data

| Domain | Typical Feature Scale | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS/Genomic Selection | 10,000 to 11+ million SNPs [3] [2] | Overfitting, noise amplification, high computational cost, population structure confounding |

| Transcriptomics | 20,000+ genes [4] | Sample heterogeneity, false positive findings, difficulty in biomarker identification |

| General ML Classification | Varies (Thousands to Millions) | Ambiguous class boundaries, model interpretability loss, feature correlation (multicollinearity) |

Navigating the High-Dimensional Landscape: A Taxonomy of Feature Selection Strategies

Feature selection methods are broadly classified into three categories: filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. A fourth category, hybrid methods, combines elements from the others.

Filter Methods

Filter methods select features based on statistical properties (e.g., correlation with the target variable, variance) independently of any machine learning model [5]. They are computationally efficient and scalable. Common examples include ANOVA F-test, correlation coefficients, and chi-squared tests. In bioinformatics, univariate correlation filters are often used as an initial step to remove features not directly related to the class or predicted variable [1]. A limitation is that they may not account for interactions between features.

Wrapper Methods

Wrapper methods evaluate feature subsets by training a specific ML model and assessing its performance. They are often more computationally intensive than filter methods but can capture feature interactions and yield high-performing feature sets [1] [5]. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a prominent wrapper method that iteratively removes the least important features based on model-derived importance rankings [6].

Embedded Methods

Embedded methods integrate feature selection as part of the model training process. Algorithms like LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) and Ridge Regression incorporate regularization to shrink or eliminate less important feature coefficients [5]. Tree-based models like Random Forest also provide native feature importance scores.

Hybrid and Ensemble Approaches

Hybrid methods combine techniques to leverage their respective strengths. For instance, the GRE framework integrates GWAS (a filter-like method) with Random Forest (an embedded/wrapper method) to select SNPs with both biological significance and predictive power [3]. Ensemble approaches aggregate feature importance scores from multiple models to improve robustness [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection Method Categories

| Method Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Genomic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter | Statistical scoring | Fast, model-agnostic, scalable | Ignores feature interactions | Pre-filtering genes/SNPs [1] |

| Wrapper | Model performance | Captures feature interactions, high accuracy | Computationally expensive, risk of overfitting | RFE for gene selection [6] |

| Embedded | In-model regularization | Balances performance and efficiency, model-specific | Tied to a specific algorithm's bias | LASSO for SNP selection [5] |

| Hybrid/Ensemble | Combines multiple methods | Improved robustness & biological interpretability | Complex implementation | GWAS + ML for SNP discovery [3] |

Recursive Feature Elimination: A Deep Dive

Core Algorithm and Workflow

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper method that systematically prunes features to find an optimal subset. Its algorithm works as follows [6] [5]:

- Train Model: Train a chosen machine learning model on the entire set of features.

- Rank Features: Rank all features based on the model's feature importance metric (e.g., coefficients for linear models, Gini importance for tree-based models).

- Eliminate Least Important: Remove the least important feature(s). The number removed per iteration is defined by the

stepparameter. - Repeat: Repeat steps 1-3 on the remaining features until the desired number of features is reached.

Implementation and Best Practices

RFE can be implemented using libraries like scikit-learn in Python. A basic implementation is shown below [6]:

For optimal results, consider these best practices [6]:

- Choose the Appropriate Number of Features: Use cross-validation to determine the optimal number of features.

- Set Cross-Validation Folds: Proper cross-validation reduces overfitting and improves model generalization.

- Handle High Dimensions: For ultra-high-dimensional data, consider an initial filter step to reduce feature space before applying RFE.

- Address Multicollinearity: RFE can handle correlated features, but other techniques like PCA may be more effective in some cases.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- Interaction Awareness: Considers interactions between features, making it suitable for complex datasets [6].

- Model Flexibility: Can be used with any supervised learning algorithm (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, Logistic Regression) [6] [5].

- Overfitting Mitigation: By selecting a parsimonious feature set, it reduces the risk of overfitting [5].

Limitations:

- Computational Cost: Can be expensive for large datasets and complex models [6].

- Correlated Features: May not be the best approach for datasets with many highly correlated features [6].

- Model Dependency: The selected feature subset is dependent on the underlying estimator used.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Case Study: An Explainable ML Pipeline for Transcriptomic Data

A study on Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) developed an explainable ML pipeline to classify 453 donor retinas based on transcriptome data, identifying 81 genes distinguishing AMD from controls [4].

Protocol:

- Feature Selection: Three filter methods (ANOVA F-test, AUC, and Kruskal-Wallis test) were applied to the training set. The top 100 features from 1000 iterations of each method were compared, revealing 81 consensus "ML-genes."

- Model Training and Validation: Data was split into training (64%), validation (16%), and an external test set (20%). Four models were evaluated: Neural Network, Logistic Regression, XGBoost, and Random Forest.

- Performance Evaluation: The XGBoost model performed best (AUC-ROC = 0.80). The robustness of the 81-gene set was validated against gene sets from GWAS loci, literature, and a permuted dataset.

- Model Interpretation: SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) was used to explain predictions and rank the contribution of each gene.

Case Study: The GRE Framework for Genomic Selection in Wheat

The GRE framework was designed to address genomic selection in wheat yield traits by combining GWAS and Random Forest for hybrid feature selection [3].

Protocol:

- Data Preparation: A population of 1,768 winter wheat breeding lines was genotyped. After quality control (MAF > 0.05, <10% missing data), 11,089 SNPs were retained.

- Hybrid Feature Selection:

- GWAS: The FarmCPU model was used to perform association testing between SNPs and yield traits. SNPs were ranked by P-value.

- Random Forest: RF was used to rank SNPs by their predictive importance.

- Subset Construction: Multiple SNP subsets (intersection, union, and individual selections) from GWAS and RF were constructed to analyze the impact of marker scale.

- Genomic Selection Modeling: Six GS algorithms (GBLUP and five ML models) were evaluated on the different SNP subsets.

- Performance and Interpretation: Model performance was assessed using prediction accuracy (PCC) and error (MSE). SHAP analysis was applied to the best-performing model (XGBoost) to interpret the main and interaction effects of significant SNPs.

Table 3: Performance of GS Models on Union SNP Subset (383 SNPs) in GRE Framework [3]

| Model | Prediction Accuracy (PCC) | Stability (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | > 0.864 | < 0.005 |

| ElasticNet | > 0.864 | < 0.005 |

| Other Models (GBLUP, etc.) | Lower than XGB/ElasticNet | Higher than XGB/ElasticNet |

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genomic Feature Selection

| Item / Tool Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn | Software Library | Provides implementations of RFE, various ML models, and feature selection methods in Python [6]. |

| SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) | Software Library | Explains output of ML models by quantifying the contribution of each feature to individual predictions [4] [3]. |

| GAPIT3 | Software | Performs Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) analysis to identify significant trait-associated markers [3]. |

| Caret R Package | Software Library | Streamlines the process for creating predictive models, including feature selection and model training [1]. |

| Random Forest | Algorithm | Provides embedded feature importance scores; can be used as the estimator within RFE or for standalone selection [1] [3]. |

| SVM (Support Vector Machines) | Algorithm | A popular model to pair with RFE for feature selection, particularly in high-dimensional biological data [6]. |

| High-Dimensional Genomic Dataset | Data | e.g., WGS SNPs (11M+ features) [2], gene expression arrays (27k+ features) [1]; used as input for testing FS methods. |

The curse of dimensionality is an inescapable reality in modern genomic research. Effectively navigating this high-dimensional landscape is not merely a computational exercise but a prerequisite for robust biological discovery and translation. As demonstrated, feature selection—and particularly structured approaches like Recursive Feature Elimination and hybrid frameworks—provides an essential pathway to distill millions of features into meaningful biological signals. By leveraging these methodologies, researchers and drug developers can enhance model performance, gain clearer insights into disease mechanisms, and ultimately accelerate the development of diagnostics and therapeutics. The integration of explainable AI tools like SHAP further enriches this process, ensuring that complex models yield interpretable and actionable biological hypotheses. The continued refinement of feature selection strategies will be paramount in unlocking the full potential of genomic data in the era of precision medicine and intelligent breeding.

What is Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)? Core Principles and Workflow

In the field of bioinformatics and computational biology, researchers increasingly encounter datasets where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins, chemical descriptors) far exceeds the number of observations. This "curse of dimensionality" is particularly prevalent in omics technologies, including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics, where thousands of features are measured across limited samples. Not all features contribute equally to predictive models; some are irrelevant or redundant, leading to increased computational costs, decreased model performance, and potential overfitting [7] [8]. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a powerful feature selection method to address these challenges by systematically identifying the most informative features for machine learning models.

RFE is particularly valuable in bioinformatics research and drug development because it moves beyond simple univariate filter methods by considering complex feature interactions within biological systems [6]. Biological processes are often governed by networks of core features with direct, large effects and peripheral features with smaller, indirect effects [8]. Traditional feature selection methods often capture only the core features, potentially missing biologically relevant context. RFE's iterative, model-based approach helps address this limitation, making it suitable for complex biomedical datasets where both core and peripheral features may hold predictive power and biological significance.

Core Principles of RFE

Definition and Key Characteristics

Recursive Feature Elimination is a backward selection algorithm that works by recursively removing features and building a model on the remaining attributes. It uses a model's coefficients or feature importance scores to identify which features contribute least to the prediction task and systematically eliminates them until a specified number of features remains [6] [9]. The "recursive" nature of this process refers to the repeated cycles of model training, feature ranking, and elimination of the least important features.

Think of RFE as a sculptor meticulously chipping away the least important parts of your dataset until you're left with only the most essential features that truly matter for your predictions [9]. This process stands in contrast to filter methods, which evaluate features individually based on statistical measures, and transformation methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), which create new feature combinations that may lack biological interpretability [6].

Comparison with Other Feature Selection Methods

Table 1: Comparison of RFE with Other Feature Selection Approaches

| Method Type | How It Works | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Evaluates features individually using statistical measures (e.g., correlation, mutual information) [6]. | Fast computation; Model-independent; Simple implementation [6]. | Ignores feature interactions; May not be effective with high-dimensional datasets [6]. | Preliminary feature screening; Very large datasets where computational efficiency is critical. |

| Wrapper Methods (including RFE) | Uses a learning algorithm to evaluate feature subsets; Selects features based on model performance [6]. | Considers feature interactions; Often more effective for high-dimensional data [6]. | Computationally intensive; Prone to overfitting; Sensitive to choice of learning algorithm [6]. | Complex datasets with interacting features; When model performance is prioritized. |

| Embedded Methods | Feature selection is built into the model training process (e.g., Lasso regularization) [10]. | Less computationally intensive than wrappers; Considers feature interactions [10]. | Tied to specific algorithms; May not provide optimal feature sets for all models. | Scenarios where specific algorithms with built-in selection are appropriate. |

| RFE | Iteratively removes least important features based on model weights/importance [6] [11]. | Model-agnostic; Handles feature interactions; Provides feature rankings; Reduces overfitting [6] [9]. | Computationally expensive for large datasets; May not be optimal for highly correlated features [6]. | High-dimensional datasets (e.g., omics data); When feature interpretability is important. |

The RFE Workflow

Step-by-Step Algorithm

The RFE algorithm follows a systematic, iterative process to identify the optimal feature subset:

Train Model with All Features: Begin by training the chosen machine learning model using the entire set of features [6] [9].

Rank Features by Importance: Calculate feature importance scores using the model's

coef_orfeature_importances_attributes [11]. Features are ranked based on these scores.Eliminate Least Important Feature(s): Remove the feature(s) with the lowest importance scores. The number of features removed per iteration is determined by the

stepparameter [11] [9].Repeat Process: Repeat steps 1-3 using the reduced feature set until the desired number of features is reached [6].

Return Selected Features: Output the final set of selected features [9].

This process can be visualized through the following workflow:

Dynamic RFE and Advanced Variants

To address computational limitations of standard RFE with large datasets, researchers have developed enhanced versions. Dynamic RFE implements a more flexible elimination strategy, removing a larger number of features initially and transitioning to single-feature elimination as the feature set shrinks [8]. This approach significantly reduces computation time while maintaining high prediction accuracy.

Another important advancement is SVM-RFE with non-linear kernels, which extends RFE's capability to work with non-linear support vector machines and survival analysis [12]. This is particularly valuable for biomedical data where relationships between predictors and outcomes are often complex and non-linear.

For multi-modal or highly complex datasets, Hybrid RFE (H-RFE) approaches integrate multiple machine learning algorithms to determine feature importance. One implementation combines Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machine, and Logistic Regression, aggregating their feature weights to determine the final feature importance ranking [10]. This ensemble approach leverages the strengths of different algorithms to produce more robust feature selection.

Implementation and Experimental Protocols

RFE with scikit-learn

The scikit-learn library in Python provides comprehensive implementations of RFE through the RFE and RFECV (RFE with Cross-Validation) classes [6] [9]. The following code example demonstrates a basic implementation:

RFE with Cross-Validation (RFECV)

A significant challenge in standard RFE is determining the optimal number of features to select. RFECV addresses this by automatically finding the optimal number of features through cross-validation [11] [9]:

The RFECV visualization plots the number of features against cross-validated scores, typically showing improved performance as irrelevant features are eliminated, eventually plateauing or declining as important features are removed [11].

dRFEtools for Omics Data

For large-scale omics data, the dRFEtools package implements dynamic RFE specifically designed for high-dimensional biological datasets [8]. Key functions include:

rf_rfeanddev_rfe: Main functions for dynamic RFE with regression and classification modelsextract_max_lowess: Extracts core feature set based on local maximum of LOWESS curveextract_peripheral_lowess: Identifies both core and peripheral features by analyzing the rate of change in the LOWESS curve

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RFE Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn RFE/RFECV | Feature selection implementation [6] [11] | General machine learning applications | Model-agnostic; Integration with scikit-learn pipeline; Cross-validation support |

| dRFEtools | Dynamic RFE for omics data [8] | Bioinformatics; Large-scale omics datasets | Dynamic step sizes; Reduced computational time; Core/peripheral feature identification |

| Yellowbrick RFECV | Visualizes RFE process [11] | Model selection and evaluation | Visualization of feature selection process; Cross-validation scores plotting |

| Padel Software | Molecular descriptor calculation [13] | Drug discovery; Chemical informatics | Calculates 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors; Fingerprint generation |

| SVM-RFE | Feature selection with non-linear kernels [12] | Complex biomedical data analysis | Works with non-linear relationships; Survival analysis support |

Applications in Bioinformatics and Drug Discovery

Bioinformatic Case Studies

RFE has demonstrated significant utility across various bioinformatics domains:

Gene Selection for Cancer Diagnosis: RFE has been applied to select informative genes for cancer diagnosis and prognosis, helping improve diagnostic accuracy and enabling personalized treatment plans [6] [8]. In one study using BrainSeq Consortium data, dRFEtools identified biologically relevant core and peripheral features applicable for pathway enrichment analysis and expression QTL studies [8].

Drug Discovery and Repurposing: RFE facilitates identification of key molecular descriptors and fingerprints that differentiate bioactive compounds. In the development of NFκBin, a tool for predicting TNF-α induced NF-κB inhibitors, RFE was employed to select relevant features from 10,862 molecular descriptors, resulting in a model with AUC of 0.75 for classifying inhibitors versus non-inhibitors [13].

Channel Selection in Brain-Computer Interfaces: In EEG-based motor imagery recognition, H-RFE has been used for channel selection, integrating random forest, gradient boosting, and logistic regression to identify optimal channel subsets, achieving 90.03% accuracy on the SHU dataset using only 73.44% of total channels [10].

Academic Performance Prediction

Beyond bioinformatics, RFE has proven valuable in educational data mining. In constructing academic early warning models, SVM-RFE was used to identify key factors impacting student performance, resulting in a model with 92.3% prediction accuracy and 7.8% false alarm rate [14].

Best Practices and Considerations

Implementation Guidelines

For optimal RFE performance in bioinformatics research:

Scale Features: Normalize or standardize features before applying RFE, particularly for distance-based algorithms like SVM [6] [9].

Choose Appropriate Estimator: Select an estimator that provides meaningful feature importance scores aligned with your data characteristics and research question [9].

Balance Computational Cost and Precision: For large datasets, consider larger step sizes initially or use dynamic RFE to reduce computation time [8] [9].

Validate on Holdout Data: Always evaluate the final model with selected features on completely unseen data to assess generalizability [9].

Incorporate Domain Knowledge: When possible, combine algorithmic feature selection with domain expertise for biologically meaningful results [9].

Advantages and Limitations

Table 3: Advantages and Limitations of RFE

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Handles high-dimensional datasets effectively [6] | Computationally expensive for very large datasets [6] |

| Considers interactions between features [6] | May not be optimal for datasets with many highly correlated features [6] |

| Model-agnostic - works with any supervised learning algorithm [6] | Performance depends on the choice of underlying estimator [6] |

| Reduces overfitting by eliminating irrelevant features [9] | May not work well with noisy or irrelevant features [6] |

| Improves model interpretability through feature reduction [9] | Requires careful parameter tuning (step size, number of features) [11] |

Recursive Feature Elimination represents a powerful approach to feature selection that is particularly well-suited for bioinformatics research and drug development. Its ability to handle high-dimensional data while considering complex feature interactions makes it valuable for analyzing omics datasets, identifying biomarkers, and building predictive models in drug discovery. The core RFE algorithm systematically eliminates less important features through iterative model training, with enhancements like dynamic RFE and hybrid RFE addressing computational challenges and improving performance for specific applications.

As biomedical datasets continue to grow in size and complexity, RFE and its variants will remain essential tools in the bioinformatician's toolkit, enabling more efficient, interpretable, and robust predictive models. By following best practices and selecting appropriate implementations for specific research contexts, scientists can leverage RFE to uncover biologically meaningful patterns and enhance their computational research pipelines.

Feature selection stands as a critical preprocessing step in the analysis of high-dimensional biological data, serving to improve model performance, reduce overfitting, and enhance the interpretability of machine learning models. In bioinformatics research, where datasets often encompass thousands to millions of features (such as genes, single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or microbial operational taxonomic units), identifying the most biologically relevant features is paramount for extracting meaningful insights. Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three approaches: filter methods that select features based on statistical measures independently of the model, wrapper methods that use a specific machine learning model to evaluate feature subsets, and embedded methods that integrate feature selection directly into the model training process. Among these, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a particularly effective wrapper method, especially in bioinformatics applications ranging from cancer genomics to microbial ecology. Originally developed for gene selection in cancer classification, RFE's iterative process of recursively removing less important features and rebuilding the model has demonstrated robust performance in identifying critical biomarkers and biological signatures despite the high-dimensionality and complex interactions characteristic of biological data [15] [16]. This technical guide examines RFE's methodological advantages over filter and embedded techniques, providing bioinformatics researchers with practical frameworks for implementation and evaluation.

The Recursive Feature Elimination Algorithm: Core Mechanics

Foundational Principles and Workflow

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) operates as a greedy backward elimination algorithm that systematically removes the least important features through iterative model retraining. The core intuition underpinning RFE is that feature importance should be recursively reassessed after eliminating less relevant features, thereby accounting for changing dependencies within the feature set. The algorithm begins by training a designated machine learning model on the complete feature set, then ranks all features based on a model-specific importance metric, eliminates the lowest-ranked feature(s), and repeats this process with the reduced feature set until a predefined stopping criterion is met [15] [6] [17].

The standard RFE workflow comprises the following operational steps:

- Initialization: Train the selected machine learning model (e.g., Support Vector Machine, Random Forest) using all available features in the dataset.

- Feature Ranking: Compute importance scores for each feature using model-specific metrics (e.g., regression coefficients for linear models, Gini importance for tree-based models, or permutation importance for non-linear models).

- Feature Elimination: Remove the bottom

kfeatures (wherekis typically 1 or a small percentage of remaining features) based on the computed importance ranking. - Iteration: Retrain the model using the retained features and repeat steps 2-3.

- Termination: Continue iterations until a predefined number of features remains or until model performance deteriorates beyond a specified threshold [15] [6].

This recursive process enables RFE to perform a more thorough assessment of feature importance compared to single-pass approaches, as feature relevance is continuously reevaluated after removing potentially confounding or redundant features [17].

RFE Process Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the recursive workflow of the RFE algorithm:

Implementation Considerations for Bioinformatics

Successful implementation of RFE in bioinformatics requires careful consideration of several algorithmic parameters. The step size (k), or number of features eliminated per iteration, significantly impacts computational efficiency versus resolution of the feature ranking. Smaller step sizes (e.g., 1-5% of features) provide finer-grained assessment but increase computational burden, which can be substantial with large genomic datasets [6] [18]. The stopping criterion must be deliberately selected, either as a predetermined number of features (requiring domain knowledge or separate validation) or through performance-based termination when model accuracy begins to degrade [17]. For enhanced robustness, cross-validation should be integrated directly into the RFE process (as with RFECV in scikit-learn) to mitigate overfitting and provide more reliable feature rankings [18] [19].

Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Paradigms

Methodological Comparison Framework

To objectively evaluate RFE's position within the feature selection landscape, it is essential to understand the fundamental characteristics of the three primary selection paradigms. Filter methods operate independently of any machine learning model, selecting features based on univariate statistical measures such as correlation coefficients, mutual information, or variance thresholds. While computationally efficient, these approaches cannot account for complex feature interactions or multivariate relationships [20] [21]. Wrapper methods, including RFE, evaluate feature subsets by directly measuring their impact on a specific model's performance. Though computationally more intensive, this approach captures feature dependencies and interactions, typically resulting in superior predictive performance [15] [6]. Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly within the model training process, with examples including LASSO regularization (which penalizes absolute coefficient values) and tree-based importance measures. These approaches balance computational efficiency with consideration of feature interactions but are often algorithm-specific [20] [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methodologies

| Characteristic | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods (RFE) | Embedded Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Criteria | Statistical measures (correlation, variance) | Model performance metrics | In-model regularization or importance |

| Feature Interactions | Generally not considered | Explicitly accounts for interactions | Algorithm-dependent consideration |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | Moderate |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low | Moderate to high (requires cross-validation) | Moderate |

| Model Specificity | Model-agnostic | Model-specific | Algorithm-specific |

| Primary Advantages | Fast execution, scalability | High performance, interaction detection | Balance of efficiency and performance |

| Typical Bioinformatics Applications | Preliminary feature screening, large-scale genomic prescreening | Biomarker identification, causal feature discovery | High-dimensional regression, feature analysis with specific algorithms |

Empirical Performance Benchmarks

Recent benchmarking studies across diverse bioinformatics domains provide quantitative evidence of RFE's performance characteristics. In metabarcoding data analysis, RFE combined with tree ensemble models like Random Forest demonstrated enhanced performance for both regression and classification tasks, effectively capturing nonlinear relationships in microbial community data [19]. A comprehensive evaluation across educational and healthcare predictive tasks revealed that while RFE wrapped with tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost) yielded strong predictive performance, these methods tended to retain larger feature sets with higher computational costs. Notably, an Enhanced RFE variant achieved substantial feature reduction with only marginal accuracy loss, offering a favorable balance for practical applications [15] [17].

Table 2: Empirical Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Domain/Dataset | Filter Method Performance | RFE Performance | Embedded Method Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes Dataset (Regression) | R²: 0.4776, MSE: 3021.77 (9 features) | R²: 0.4657, MSE: 3087.79 (5 features) | R²: 0.4818, MSE: 2996.21 (9 features) | Embedded method (LASSO) provided best performance with minimal feature reduction [20] |

| Video Traffic Classification | Moderate accuracy, low computational overhead | Higher accuracy, significant processing time | Balanced accuracy and efficiency | RFE achieved superior accuracy where performance prioritized over efficiency [21] |

| Metabarcoding Data Analysis | Variable performance across datasets | Enhanced Random Forest performance across tasks | Robust without feature selection | RFE improved model performance while identifying biologically relevant features [19] |

| Educational and Healthcare Predictive Tasks | Not benchmarked | Strong predictive performance with larger feature sets | Not benchmarked | Enhanced RFE variant offered optimal balance of accuracy and feature reduction [15] |

RFE Advantages in Bioinformatics Applications

Handling High-Dimensional Biological Data

Bioinformatics datasets characteristically exhibit the "curse of dimensionality," with feature counts (e.g., genes, SNPs) often dramatically exceeding sample sizes. RFE has demonstrated particular effectiveness in these high-dimension, low-sample-size scenarios common to genomic and transcriptomic studies [15] [17]. The method's recursive reassessment of feature importance enables it to navigate complex dependency structures among biological features, where the relevance of one biomarker may be contingent on the presence or absence of others. This capability is particularly valuable in genomics, where epistatic interactions (gene-gene interactions) play crucial roles in disease etiology [16].

Preservation of Feature Interpretability

Unlike dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) that transform original features into composite representations, RFE preserves the original biological features throughout the selection process [15] [17]. This characteristic is paramount in bioinformatics, where maintaining the biological interpretability of selected features (e.g., specific genes, polymorphisms, or microbial taxa) is essential for deriving mechanistic insights and generating biologically testable hypotheses. The method produces a transparent ranking of features based on their contribution to model performance, providing researchers with directly interpretable results [6] [18].

Detection of Complex Feature Interactions

RFE's model-wrapped approach enables it to detect and leverage complex, nonlinear feature interactions that are frequently present in biological systems. This capability represents a significant advantage over filter methods, which typically evaluate features in isolation [6] [16]. For example, in cancer genomics, RFE has successfully identified interacting single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that exhibit minimal marginal effects but significant combinatorial effects on disease risk—patterns that would be undetectable through univariate screening approaches commonly employed in genome-wide association studies [16].

Implementation Protocols for Bioinformatics Research

Experimental Design Considerations

Implementing RFE effectively in bioinformatics research requires careful experimental design. The initial critical step involves estimator selection, where the choice of machine learning model should align with both data characteristics and biological question. Support Vector Machines with linear kernels provide transparent coefficient-based feature rankings, while tree-based methods like Random Forests or XGBoost effectively capture complex interactions at the cost of increased computational requirements [15] [19]. The stopping criterion must be established through cross-validation rather than arbitrary feature counts, with the RFECV implementation providing automated optimization of this parameter [18]. For genomic applications, data preprocessing including normalization, batch effect correction, and addressing compositional effects in sequencing data is essential, as technical artifacts can significantly distort feature importance rankings [19].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RFE Implementation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Functionality | Bioinformatics Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | Python, R | Core computational infrastructure | Python's scikit-learn provides extensive RFE implementation; R offers caret and randomForest packages |

| Core Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn, XGBoost, MLR | RFE algorithm implementations | scikit-learn provides RFE and RFECV classes compatible with any estimator exposing feature importance attributes |

| Specialized Bioinformatics Packages | Bioconductor, SciKit-Bio, QIIME2 | Domain-specific data handling | Critical for proper preprocessing of genomic, transcriptomic, and metabarcoding data prior to feature selection |

| Visualization Tools | Matplotlib, Seaborn, ggplot2 | Results visualization and interpretation | Essential for creating feature importance plots, performance curves, and biological validation figures |

| High-Performance Computing | Dask, MLflow, Snakemake | Computational workflow management | Crucial for managing computational demands of RFE on large genomic datasets |

Advanced RFE Variants for Complex Biological Data

Several RFE variants have been developed to address specific analytical challenges in bioinformatics. RFEST (RFE by Sensitivity Testing) employs trained non-linear models as approximate oracles for membership queries, "flipping" feature values to test their impact on model predictions rather than simply deleting them [16]. This approach has demonstrated particular utility for identifying features involved in complex interaction patterns, such as correlation-immune functions where individual features show no marginal association with the outcome. Enhanced RFE incorporates additional optimization techniques within the recursive framework, achieving substantial dimensionality reduction with minimal accuracy loss, making it particularly valuable for clinical applications with extreme dimensionality [15] [17]. Model-agnostic RFE implementations leverage permutation importance rather than model-specific importance metrics, enabling application with any machine learning algorithm, including deep neural networks increasingly employed in bioinformatics [19].

Recursive Feature Elimination represents a powerful wrapper approach for feature selection in bioinformatics, offering distinct advantages in handling high-dimensional biological data while maintaining feature interpretability. Its capacity to recursively reassess feature importance and account for complex interactions makes it particularly suited to the multifaceted nature of biological systems, from gene-gene interactions in cancer genomics to microbial co-occurrence patterns in microbiome studies. While computationally more intensive than filter methods and less algorithmically constrained than embedded approaches, RFE's performance benefits and flexibility justify its application in biomarker discovery, causal feature identification, and predictive model development. As bioinformatics continues to grapple with increasingly complex and high-dimensional datasets, RFE and its evolving variants will remain essential tools in the researcher's arsenal, enabling the extraction of biologically meaningful insights from complex data landscapes.

The "missing heritability" problem represents a fundamental conundrum in modern genetics. Coined in 2008, this problem describes the significant discrepancy between heritability estimates derived from traditional quantitative genetics and those obtained from molecular genetic studies [22] [23]. Quantitative genetic studies, particularly those using twin and family designs, have long indicated that genetic factors explain approximately 50-80% of variation in many complex traits and diseases. For intelligence (IQ), for instance, twin studies suggest heritability of 0.5 to 0.7, meaning 50-70% of variance is statistically associated with genetic differences [23]. In stark contrast, early genome-wide association studies (GWAS) could only account for a small fraction of this expected genetic influence—approximately 10% for IQ in initial studies [23]. This substantial gap between what family studies suggest and what molecular methods can detect constitutes the core of the missing heritability problem.

The resolution to this problem has profound implications for our understanding of genetic architecture. Early optimistic forecasts following the Human Genome Project suggested that specific genes and variants underlying complex traits would be quickly identified [22]. However, the discovered variants through candidate-gene studies and early GWAS explained surprisingly little phenotypic variance. This prompted a reevaluation of genetic architecture and statistical approaches. Over time, evidence has accumulated that a substantial portion of this missing heritability can be explained by thousands of variants with very small effect sizes that early GWAS were underpowered to detect [22] [24]. For example, a recent study on human height including 5.4 million individuals identified approximately 12,000 independent variants, largely resolving the missing heritability for this model trait [22]. Nevertheless, for many complex traits, particularly behavioral phenotypes, a significant heritability gap persists, prompting investigation into more complex genetic architectures involving feature interactions.

The Limits of Conventional GWAS and The Need for Advanced Feature Selection

The Evolution of Heritability Estimation Methods

Traditional heritability estimation (h²Twin) primarily derives from quantitative analyses of twins and families, comparing phenotypic similarity between monozygotic (sharing 100% of DNA) and dizygotic twins (sharing approximately 50% of DNA) [23]. This approach provides coarse-grained estimates of genetic influence. The advent of molecular methods introduced several distinct metrics: h²GWAS, which sums the effect sizes of individual single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that meet genome-wide significance thresholds; and h²SNP (or h²WGS), which analyzes all SNPs simultaneously without significance thresholds by comparing overall genetic similarity to phenotypic similarity in unrelated individuals [24] [23]. Typically, these metrics follow a consistent pattern: h²GWAS < h²SNP < h²Twin, with the gaps between them representing different components of missing heritability [23].

Why Conventional Approaches Miss Feature Interactions

Conventional GWAS methodologies face several limitations in detecting the full genetic architecture of complex traits. First, they primarily focus on additive genetic effects from individual SNPs, largely ignoring epistasis (gene-gene interactions) and gene-environment interactions [22] [25]. Second, the statistical corrections for multiple testing in GWAS require stringent significance thresholds (typically p < 5 × 10⁻⁸), making it difficult to detect variants with small effect sizes or those whose effects are conditional on other variables [23]. Third, GWAS often fails to account for rare variants (MAF < 1%) that may contribute substantially to heritability but are poorly captured by standard genotyping arrays [24].

The fundamental challenge is that complex traits likely involve module effects, where the influence of a gene can only be detected when considered jointly with other genes in the same functional module [25]. As noted in one study, "gene–gene interaction is difficult due to combinatorial explosion" [25]. With tens of thousands of potential variables and exponentially more potential interactions, conventional methods struggle both computationally and statistically.

Table 1: Types of Heritability Estimates and Their Characteristics

| Heritability Type | Methodology | Key Characteristics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| h²Twin | Twin/family studies | Coarse-grained; compares MZ/DZ twins | Confounds shared environment; cannot pinpoint specific variants |

| h²GWAS | Genome-wide association studies | Sums effects of significant SNPs (p < 5×10⁻⁸) | Misses non-additive effects; underpowered for small effects |

| h²SNP | Genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) | Uses all SNPs simultaneously; unrelated individuals | Still primarily additive; requires large sample sizes |

| h²WGS | Whole-genome sequencing | Captures rare variants (MAF < 1%) and common variants | Computationally intensive; still emerging |

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): A Primer for Bioinformatics

Core Principles of RFE

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful feature selection algorithm that operates through iterative model refinement. As a wrapper-style feature selection method, RFE evaluates feature subsets using a specific machine learning algorithm's performance, making it particularly suited for detecting complex, interactive genetic effects [26] [6] [27]. The fundamental premise of RFE is to recursively eliminate the least important features based on a model's feature importance metrics, ultimately arriving at an optimal feature subset that maximizes predictive performance while minimizing dimensionality [6].

The RFE algorithm follows these core steps [6] [27]:

- Initialization: Train a model using all available features in the dataset

- Ranking: Rank features based on importance scores (e.g., regression coefficients, featureimportances)

- Elimination: Remove the least important feature(s)

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1-3 on the reduced feature set until reaching the predetermined number of features

This recursive process ensures that feature selection considers interactions between features, as the importance of each feature is continually re-evaluated in the context of the remaining feature set [6].

RFE Implementation Considerations for Genomic Data

Implementing RFE effectively on genomic data requires careful consideration of several factors. The choice of estimator (base algorithm) significantly influences feature selection results. While linear models like SVM with linear kernels or logistic regression provide transparent coefficient interpretation, non-linear models like random forests or SVM with non-linear kernels can capture more complex relationships but may be less interpretable [28]. For genomic data where interaction effects are expected, non-linear kernels may be preferable despite computational costs.

The step parameter determines how many features are eliminated each iteration. Smaller steps (e.g., step=1) are more computationally expensive but may produce more optimal feature subsets, particularly when features have complex interdependencies [26]. For high-dimensional genomic data with thousands to millions of variants, larger step sizes may be necessary for computational feasibility.

Cross-validation is essential when using RFE with genomic data to avoid overfitting. The RFECV implementation in scikit-learn automatically performs cross-validation to determine the optimal number of features [27]. Additionally, data preprocessing including standardization and normalization is crucial, particularly for distance-based algorithms like SVM [6].

Diagram 1: RFE Algorithm Workflow

Interaction-Based Feature Selection: Bridging the Heritability Gap

Theoretical Foundation for Interaction Effects in Genetics

The case for considering feature interactions in genetic studies is supported by both biological plausibility and empirical evidence. From a biological perspective, genes operate in complex networks and pathways rather than in isolation [25]. Proteins interact in signaling cascades, transcription factors cooperate to regulate gene expression, and metabolic pathways involve sequential enzyme interactions. These biological realities suggest that non-additive genetic effects should be widespread, particularly for complex traits influenced by multiple biological systems.

Epistasis (gene-gene interaction) has been proposed as a significant contributor to missing heritability [25]. As one study notes, "There is a growing body of evidence suggesting gene–gene interactions as a possible reason for the missing heritability" [25]. The combinatorial nature of these interactions creates challenges for detection, as the number of potential interactions grows exponentially with the number of variants. This "combinatorial explosion" necessitates sophisticated feature selection methods like RFE that can efficiently navigate this vast search space.

Advanced Interaction Detection Methods

Several advanced methodologies have been developed specifically to detect interaction effects in genetic data. The Influence Measure (I-score) represents one innovative approach designed to identify variable subsets with strong joint effects on the response variable, even when individual marginal effects may be weak [25]. The I-score is calculated as:

I = Σj(nj)(Ȳj - Ȳ)²

Where nj is the number of observations in partition element j, Ȳj is the mean response in partition element j, and Ȳ is the overall mean response [25]. This measure captures the discrepancy between conditional and marginal means of Y, without requiring specification of a model for the joint effect.

The Backward Dropping Algorithm (BDA) works in conjunction with the I-score, operating as a greedy algorithm that searches for variable subsets maximizing the I-score through stepwise elimination [25]. The algorithm:

- Selects an initial subset of k explanatory variables

- Computes the I-score

- Tentatively drops each variable and recalculates the I-score

- Permanently drops the variable that results in the highest I-score when removed

- Continues until only one variable remains, retaining the subset with the highest I-score

For non-linear relationships, SVM-RFE with non-linear kernels extends the standard RFE approach. This method is particularly valuable when variables interact in complex, non-linear ways [28]. The RFE-pseudo-samples variant allows visualization of variable importance by creating artificial data matrices where one variable varies systematically while others are held constant, then examining changes in the model's decision function [28].

Table 2: Interaction Detection Methods in Genetic Studies

| Method | Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-score with BDA | Partitions data and measures deviation from expected distribution | Model-free; detects higher-order interactions | Computationally intensive with many variables |

| SVM-RFE with Non-linear Kernels | Uses kernel functions to capture complex decision boundaries | Can detect non-linear interactions; well-established | Black box interpretation; computational cost |

| RF-Pseudo-samples | Creates pseudo-samples to visualize variable effects | Enables visualization of complex relationships | May not scale to ultra-high dimensions |

| DeepResolve | Gradient ascent in feature map space | Visualizes feature contribution patterns; reveals negative features | Limited to neural network models |

Experimental Protocols for Interaction Detection

Protocol 1: I-score with Backward Dropping Algorithm

The I-score with BDA protocol provides a powerful method for detecting interactive feature sets without pre-specified model assumptions [25].

Sample Preparation and Data Requirements:

- Collect genomic data with n observations and p genetic variants (typically SNPs)

- Ensure all explanatory variables are discrete (can be binned if continuous)

- For case-control studies, ensure adequate sample size in both groups

- Recommended minimum sample size: 150+ observations for initial validation [25]

Initialization and Sampling:

- Select an initial subset of k explanatory variables (Sₖ) through random sampling or based on prior knowledge

- Typical initial subset size: 5-15 variables depending on computational resources

- Multiple initial subsets may be tested in parallel to explore different regions of feature space

Iterative Dropping Procedure:

- Compute I-score for current subset Sₖ using formula: I = Σj(nj)(Ȳj - Ȳ)²

- For each variable in Sₖ, tentatively drop it and compute I-score for the reduced subset

- Permanently drop the variable that yields the highest I-score when removed

- Continue the process with the reduced subset (Sₖ₋₁)

- Repeat until only one variable remains

- Identify the return set Rₛ as the subset that achieved the maximum I-score during the entire dropping process

Validation and Interpretation:

- Validate identified feature sets on independent test data

- Assess biological plausibility of interacting variants through pathway analysis

- Consider functional relationships between genes in the identified subset

Protocol 2: SVM-RFE with Non-linear Kernels for Genetic Data

This protocol adapts the standard RFE algorithm to detect non-linear interactions using support vector machines [28].

Data Preprocessing:

- Standardize all genetic variants to mean=0, variance=1

- For categorical traits, ensure balanced representation where possible

- Split data into training and testing sets (typical 70/30 or 80/20 split)

Model Initialization and Parameter Tuning:

- Select non-linear kernel (RBF recommended for initial analysis)

- Tune hyperparameters (C, γ for RBF kernel) using cross-validation

- Initialize RFE with chosen SVM model and step parameter (step=1 for highest precision)

Recursive Elimination with Visualization:

- Train SVM model with current feature set

- Compute feature importance using model-specific metrics

- For linear kernels: absolute coefficient values

- For non-linear kernels: permutation importance or RFE-pseudo-samples approach

- Rank features by importance scores

- Remove the least important feature(s) based on step parameter

- Repeat until desired number of features remains

- For visualization: Implement RFE-pseudo-samples to plot decision values against feature values

RFE-Pseudo-samples Implementation (for visualization):

- After model optimization, create pseudo-sample matrices for each feature

- For each variable, create q equally-spaced values across its range

- Hold all other variables at their mean (typically 0 after standardization)

- Obtain predicted decision values from SVM for each pseudo-sample

- Compute variability in predictions using Median Absolute Deviation (MAD): MADₚ = median(|D_qp - median(Dₚ)|)

- Plot decision values against feature values to visualize relationship patterns

Diagram 2: Interaction Detection Protocol

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Software | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | Whole-genome sequencing data | Variant calling (SNPs, indels) with MAF > 0.01% | h²WGS estimation; rare variant analysis [24] |

| Biobank Resources | UK Biobank, TOPMed | Large-scale genomic datasets with phenotypic data | Method validation; power analysis [24] |

| Software Libraries | scikit-learn (Python) | RFE, RFECV implementation | Core feature selection algorithms [26] |

| Specialized Packages | SVM-RFE extensions | Non-linear kernel support | Interaction detection in non-linear spaces [28] |

| Visualization Tools | DeepResolve | Gradient ascent in feature map space | Feature contribution patterns in DNNs [29] |

| Computational Resources | High-performance computing | Parallel processing capabilities | Handling genomic-scale data [25] |

Results Interpretation and Integration into Broader Research Context

Evaluating Method Performance and Biological Significance

Interpreting results from interaction-based feature selection requires careful consideration of both statistical and biological criteria. Statistically significant feature sets should demonstrate reproducibility across multiple initializations in BDA or cross-validation folds in RFE [25]. The magnitude of improvement in prediction accuracy when considering interactions versus additive effects provides evidence for the importance of epistasis. For example, one study on gene expression datasets found that "classification error rates can be significantly reduced by considering interactions" [25].

Biological interpretation remains paramount—identified feature interactions should be evaluated within the context of known biological pathways and networks. Overlap with previously established disease-associated genes provides supporting evidence, as demonstrated in a breast cancer study where "a sizable portion of genes identified by our method for breast cancer metastasis overlaps with those reported in gene-to-system breast cancer (G2SBC) database as disease associated" [25].

Integration with Modern Genomic Approaches

Interaction-based feature selection does not operate in isolation but should be integrated with contemporary genomic approaches. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data increasingly provides the foundation for these analyses, capturing rare variants (MAF < 1%) that contribute substantially to heritability—approximately 20% on average across phenotypes according to recent research [24]. The combination of WGS data with interaction detection methods represents a powerful strategy for resolving missing heritability.

Recent advances demonstrate promising progress. One 2025 study analyzing WGS data from 347,630 individuals found that "WGS captures approximately 88% of the pedigree-based narrow sense heritability," with rare variants playing a significant role [24]. For specific traits like lipid levels, "more than 25% of rare-variant heritability can be mapped to specific loci using fewer than 500,000 fully sequenced genomes" [24]. These findings suggest that integrating interaction-based feature selection with large-scale WGS data may substantially advance our ability to explain and map heritability.

The missing heritability problem represents both a challenge and opportunity for developing more sophisticated analytical approaches in genetics. While additive effects explain substantial heritability for many traits, evidence increasingly supports the importance of feature interactions, particularly for complex behavioral and disease phenotypes. RFE and related interaction detection methods provide powerful tools for navigating the combinatorial complexity of epistasis, offering strategies to identify feature sets that jointly influence traits.

The framework proposed by Matthews & Turkheimer (2022) suggests that missing heritability comprises three distinct gaps: the numerical gap (discrepancy in heritability estimates), prediction gap (challenge in predicting traits from genetics), and mechanism gap (understanding causal pathways) [23]. Interaction-based feature selection primarily addresses the prediction gap, with potential downstream benefits for understanding mechanisms. As these methods evolve alongside increasing sample sizes and more diverse genomic data, they promise to not only detect missing heritability but also illuminate the complex biological networks underlying human traits and diseases.

For researchers implementing these approaches, success will depend on thoughtful integration of biological knowledge, appropriate method selection based on specific research questions, and rigorous validation across multiple datasets. The continued development of visualization tools and interpretable models will further enhance our ability to translate statistical findings into biological insights, ultimately advancing both basic science and precision medicine applications.

Implementing RFE for Genomic Data: A Step-by-Step Guide from Theory to Practice

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that iteratively removes the least important features from a dataset until a specified number of features remains [30] [6]. Introduced as part of the scikit-learn library, RFE leverages a machine learning model's inherent feature importance metrics to rank and select features [30]. This methodology is particularly valuable in bioinformatics, where datasets often involve high-dimensional data with thousands of features (e.g., gene expression levels, single nucleotide polymorphisms, or protein structures) but relatively few samples [31] [32]. The primary goal of RFE is to streamline datasets by retaining only the most impactful features, thereby reducing overfitting, decreasing computational time, and improving model interpretability without significantly sacrificing predictive power [30] [7].

The core principle of RFE involves a cyclic process of model training, feature ranking based on importance scores, and elimination of the lowest-ranking features [6]. This process continues until a predefined number of features is reached or until model performance begins to degrade significantly. What makes RFE particularly effective is its ability to account for feature interactions, as the importance of each feature is evaluated in the context of others throughout the iterative process [6]. This characteristic is crucial for bioinformatics applications where biological systems often involve complex interactions between molecular components.

RFE Methodology and Workflow

Core Algorithmic Steps

The RFE algorithm follows a systematic, iterative approach to feature selection [30] [6]:

- Initialization: Train the chosen base estimator (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, or XGBoost) on the entire dataset with all features.

- Feature Ranking: Calculate importance scores for all features using the trained model. The method for determining importance depends on the base estimator.

- Feature Elimination: Remove the least important feature(s) from the current feature set. The number of features removed per iteration is determined by the

stepparameter. - Model Rebuilding: Retrain the model on the reduced feature set.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-4 until the desired number of features is reached.

This process can be computationally intensive, particularly with high-dimensional bioinformatics data. To mitigate this, the step parameter can be adjusted to remove multiple features per iteration, though this risks eliminating potentially important features too early [6]. Cross-validation techniques, such as RFECV (Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation) in scikit-learn, are often employed to automatically determine the optimal number of features [6].

RFE Process Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and iterative nature of the RFE algorithm:

Base Estimator Comparison for Bioinformatics

Support Vector Machines (SVM)

Theory and Mechanics: SVMs work by finding the optimal hyperplane that maximally separates data points of different classes in a high-dimensional space [32]. The "support vectors" are the data points closest to this hyperplane and are critical for defining its position and orientation [32]. In RFE, the absolute magnitude of the weight coefficients in the linear SVM model is typically used to rank feature importance. For non-linear kernels, permutation importance or other methods may be employed.

Bioinformatics Applications: SVMs have demonstrated remarkable success in various bioinformatics domains [31] [32]. In gene expression classification, they effectively differentiate between healthy and cancerous tissues based on microarray or RNA-seq data. For protein classification and structure prediction, SVMs trained on encoded protein sequences can accurately predict secondary and tertiary structures. Additionally, SVMs are valuable in disease diagnosis and biomarker discovery, where they integrate genomic data with clinical parameters to identify potential diagnostic markers [32].

Advantages: SVMs are particularly effective in high-dimensional spaces, which is common in genomics and proteomics [32]. They also have strong theoretical foundations in statistical learning theory and are relatively memory efficient. Their effectiveness with linear kernels provides good interpretability when used with RFE.

Limitations: SVM performance can be sensitive to the choice of kernel and hyperparameters (e.g., regularization parameter C, kernel parameters) [32]. They may also be computationally expensive for very large datasets and provide less intuitive feature importance metrics compared to tree-based methods.

Random Forests (RF)

Theory and Mechanics: Random Forests are ensemble learning methods that construct multiple decision trees during training and output the mode of the classes (classification) or mean prediction (regression) of the individual trees [33] [34]. In RFE, the feature importance is typically measured by the mean decrease in impurity (Gini importance) or permutation importance, which quantifies how much shuffling a feature's values increases the model's error [33].

Bioinformatics Applications: RF has been widely applied in genomic selection [34], drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction [35], and integrating multi-omics data [33]. A notable application is in predicting DTI using 3D molecular fingerprints (E3FP), where pairwise similarities between ligands are computed and transformed into probability density functions. The Kullback-Leibler divergence between these distributions then serves as a feature vector for the random forest model, achieving high prediction accuracy (mean accuracy: 0.882, ROC AUC: 0.990) [35].

Advantages: RF can handle high-dimensional problems with complex, nonlinear relationships between predictors [33] [34]. They naturally model interactions between features and are robust to outliers and irrelevant variables. Additionally, they provide intuitive feature importance measures.

Limitations: The presence of correlated predictors has been shown to impact RF's ability to identify strong predictors by decreasing the estimated importance scores of correlated variables [33]. While RF-RFE was proposed to mitigate this issue, it may not scale effectively to extremely high-dimensional omics datasets, as it can decrease the importance of both causal and correlated variables [33].

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting)

Theory and Mechanics: XGBoost is an advanced implementation of gradient boosted decision trees that builds models sequentially, with each new tree correcting errors made by previous ones [36] [34]. The "gradient boosting" approach minimizes a loss function by adding trees that predict the residuals or errors of prior models. In RFE, the feature importance is calculated based on how frequently a feature is used to split the data across all trees, weighted by the improvement in the model's performance gained from each split.

Bioinformatics Applications: While specific bioinformatics applications of XGBoost with RFE were limited in the search results, one study demonstrated its utility in breast cancer detection, where it was used alongside LASSO for feature selection [36]. Its general effectiveness in predictive modeling makes it suitable for various bioinformatics tasks, including disease subtype classification, survival analysis, and biomarker identification.

Advantages: XGBoost often achieves state-of-the-art performance on structured data and includes built regularization to prevent overfitting. It efficiently handles missing values and provides feature importance measures. The algorithm is also computationally efficient and highly scalable.

Limitations: XGBoost has multiple hyperparameters that require careful tuning and may be more prone to overfitting on noisy datasets if not properly regularized. The sequential nature of boosting can make training slower than Random Forests, and the model is less interpretable than a single decision tree.

Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Base Estimators

| Metric | Random Forests | Boosting (XGBoost) | Support Vector Machines | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation with True Breeding Values | 0.483 | 0.547 | 0.497 | Genomic Selection [34] |

| 5-Fold CV Accuracy (Mean) | 0.466 | 0.503 | 0.503 | Genomic Selection [34] |

| Reported Accuracy | 90.68% | N/A | N/A | Breast Cancer Detection [36] |

| DTI Prediction Accuracy | 88.2% | N/A | N/A | Drug-Target Interaction [35] |

| Computational Demand | Medium | Medium-High | High (with tuning) | General [6] [34] |

Table 2: Qualitative Characteristics of Base Estimators for RFE

| Characteristic | SVM | Random Forest | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handling High-Dimensional Data | Excellent [32] | Excellent [33] [34] | Excellent [36] |

| Handling Feature Interactions | Limited (linear kernel) | Strong [33] [34] | Strong [34] |

| Handling Correlated Features | Moderate | Decreased importance of correlated features [33] | Moderate |

| Interpretability | Moderate (linear kernel) | High | Moderate |

| Hyperparameter Sensitivity | High [32] | Low-Medium [34] | High |

Experimental Protocols and Bioinformatics Case Studies

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction with Random Forest RFE

Objective: Predict novel drug-target interactions using 3D molecular similarity features and Random Forest-based RFE [35].

Dataset Preparation:

- Source biological activity data from public databases like CHEMBL [35].

- Focus on specific pharmacological targets (e.g., 17 targets from a benchmark study).

- Remove duplicate compounds to avoid sampling bias.

- Generate 3D molecular conformers using tools like OpenEye Omega or RDKit.

Feature Engineering:

- Compute 3D molecular fingerprints (E3FP) for all compounds using RDKit [35].

- Calculate pairwise 3D similarity scores between ligands within each target (Q-Q matrix) and between queries and ligands (Q-L vector).

- Transform similarity vectors and matrices into probability density functions using kernel density estimation.

- Compute Kullback-Leibler divergence (KLD) between distributions as feature vectors for DTI prediction [35].

RF-RFE Implementation:

- Initialize Random Forest regression or classification model.

- Set elimination parameters (e.g., remove 3% of lowest-ranking features per iteration).

- Iteratively run RF, rank features by importance, and eliminate weakest features.

- Assign final ranks to variables based on removal order and most recent importance scores [33].

Validation:

- Use out-of-bag (OOB) error estimates to evaluate model performance during RFE.

- Apply external validation on holdout test sets.

- Assess final model performance using metrics like accuracy, ROC AUC, and precision-recall curves [35].

Gene Selection for Cancer Classification with SVM-RFE

Objective: Identify minimal gene sets that accurately classify cancer subtypes using SVM-RFE [32].

Microarray/RNA-seq Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize gene expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., RMA for microarray, TPM for RNA-seq).

- Perform quality control to remove low-expression genes and batch effects.

- Split data into training and validation sets while preserving class distributions.

SVM-RFE Execution:

- Standardize features to zero mean and unit variance.

- Initialize linear SVM classifier with appropriate regularization parameter (C).

- For each iteration:

- Train SVM model on current feature set.

- Compute feature weights (coefficients) from the trained model.

- Rank features by the square of the weight magnitudes.

- Remove features with smallest rankings [32].

- Continue until desired number of features remains.

Performance Evaluation:

- Use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold) to assess classification accuracy at each feature subset size.

- Select the feature subset that maximizes cross-validation accuracy.

- Validate selected gene signature on independent datasets.

- Perform functional enrichment analysis on selected genes to assess biological relevance.

Genomic Selection with XGBoost-RFE

Objective: Select informative SNP markers for predicting complex traits using XGBoost-RFE [36] [34].

Genotype and Phenotype Processing:

- Obtain dense SNP genotypes and corresponding phenotypic measurements.

- Encode SNP genotypes (e.g., 0 for homozygous reference, 1 for heterozygous, 2 for homozygous alternative).

- Perform quality control: remove SNPs with high missing rates, low minor allele frequency, or deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

- Impute missing genotypes using appropriate methods.

XGBoost-RFE Implementation:

- Initialize XGBoost regressor or classifier with appropriate parameters (learning rate, max depth, subsample ratio, etc.).

- Use built-in feature importance metrics (gain, cover, or frequency) for ranking.

- Implement custom RFE wrapper to iteratively eliminate features.