Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) in Machine Learning: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research

This comprehensive guide explores Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), a powerful wrapper-style feature selection technique critical for handling high-dimensional data in biomedical research and drug development.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) in Machine Learning: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), a powerful wrapper-style feature selection technique critical for handling high-dimensional data in biomedical research and drug development. The article details RFE's foundational principles, iterative process of model fitting and feature elimination, and practical implementation using Python and scikit-learn. It provides actionable strategies for optimization and troubleshooting, including handling computational costs and overfitting risks. A comparative analysis with other feature selection methods like filter methods and Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) is presented, alongside real-world applications in bioinformatics and biomarker discovery. Tailored for researchers and scientists, this guide equips professionals with the knowledge to enhance model interpretability, improve predictive performance, and identify stable biomarkers for clinical applications.

Understanding Recursive Feature Elimination: Core Concepts and Why It Matters for High-Dimensional Data

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) represents a powerful feature selection algorithm in machine learning that operates through iterative, backward elimination of features. This greedy optimization technique systematically removes the least important features based on a model's importance rankings, ultimately identifying the most informative feature subset for predictive modeling [1]. As a wrapper-style method, RFE considers feature interactions and dependencies, making it particularly valuable for high-dimensional datasets across various scientific domains, including pharmaceutical research and bioinformatics [2]. This technical guide examines RFE's fundamental mechanics, implementation variations, and practical applications within drug discovery pipelines, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols for deploying this algorithm effectively in their experimental workflows.

Algorithmic Foundations

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) operates on a simple yet powerful principle: recursively eliminating the least important features from a dataset until a specified number of features remains [1]. The "greedy" characterization stems from the algorithm's tendency to make locally optimal choices at each iteration by removing features with the lowest importance scores, without backtracking or reconsidering previous eliminations [1]. This approach stands in contrast to filter methods that evaluate features individually and embedded methods that perform feature selection as part of the model training process [2].

RFE belongs to the wrapper method category of feature selection techniques, meaning it utilizes a machine learning model's performance to evaluate feature subsets [3]. This model-dependent nature allows RFE to account for complex feature interactions that might be missed by filter methods, though it increases computational requirements compared to simpler approaches [2]. The algorithm's recursive elimination strategy helps mitigate the effects of correlated predictors, which is particularly valuable in omics data analysis where feature collinearity is common [4].

Historical Context and Development

The conceptual foundation for RFE was established in the early 2000s, with Guyon et al. (2002) demonstrating its application for gene selection in cancer classification using support vector machines [5]. Since its introduction, RFE has been adapted and extended across numerous domains, with significant advancements including cross-validated RFE (RFECV) for automatic determination of the optimal feature count and dynamic RFE (dRFE) for improved computational efficiency in high-dimensional spaces [6] [5].

In pharmaceutical research, RFE has gained prominence as datasets have grown in dimensionality and complexity. The algorithm's ability to identify the most biologically relevant features from thousands of molecular descriptors has made it invaluable for drug solubility prediction, biomarker identification, and toxicity assessment [7]. Recent implementations have focused on scaling RFE to accommodate ultra-high-dimensional omics data while maintaining biological interpretability [6].

Theoretical Framework and Algorithmic Mechanics

Core Algorithm Workflow

The RFE algorithm follows a systematic, iterative process that can be formalized in these discrete steps:

- Initialization: Train the chosen base model (estimator) on the complete set of features available in the dataset [1].

- Feature Ranking: Calculate importance scores for all features using model-specific attributes such as

coef_for linear models orfeature_importances_for tree-based models [5]. - Feature Elimination: Remove the weakest feature(s), typically determined by the lowest importance score(s) [1].

- Iteration: Repeat the training, ranking, and elimination process on the reduced feature set [3].

- Termination: Continue iterations until the predefined number of features remains [5].

This process generates a feature ranking where selected features receive rank 1, and eliminated features are assigned higher ranks based on their removal order [5].

Mathematical Formalization

Let ( F^{(0)} = {f1, f2, ..., f_p} ) represent the initial set of ( p ) features. At each iteration ( t ), RFE:

- Trains a model ( M^{(t)} ) on the current feature set ( F^{(t)} )

- Computes importance scores ( I^{(t)} = {i1^{(t)}, i2^{(t)}, ..., i_{|F^{(t)}|}^{(t)}} )

- Removes the feature(s) with the smallest importance score(s): ( F^{(t+1)} = F^{(t)} \setminus {f \in F^{(t)} | i_f^{(t)} \text{ is among the k smallest}} )

where ( k ) represents the step size - the number of features eliminated per iteration [5]. The algorithm terminates when ( |F^{(t)}| = n{\text{target}} ), where ( n{\text{target}} ) is the user-specified number of features to select.

The ranking assignment can be formalized as: [ \text{rank}(f) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } f \in F^{(T)} \ 1 + \text{iteration when removed} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ] where ( T ) represents the final iteration [5].

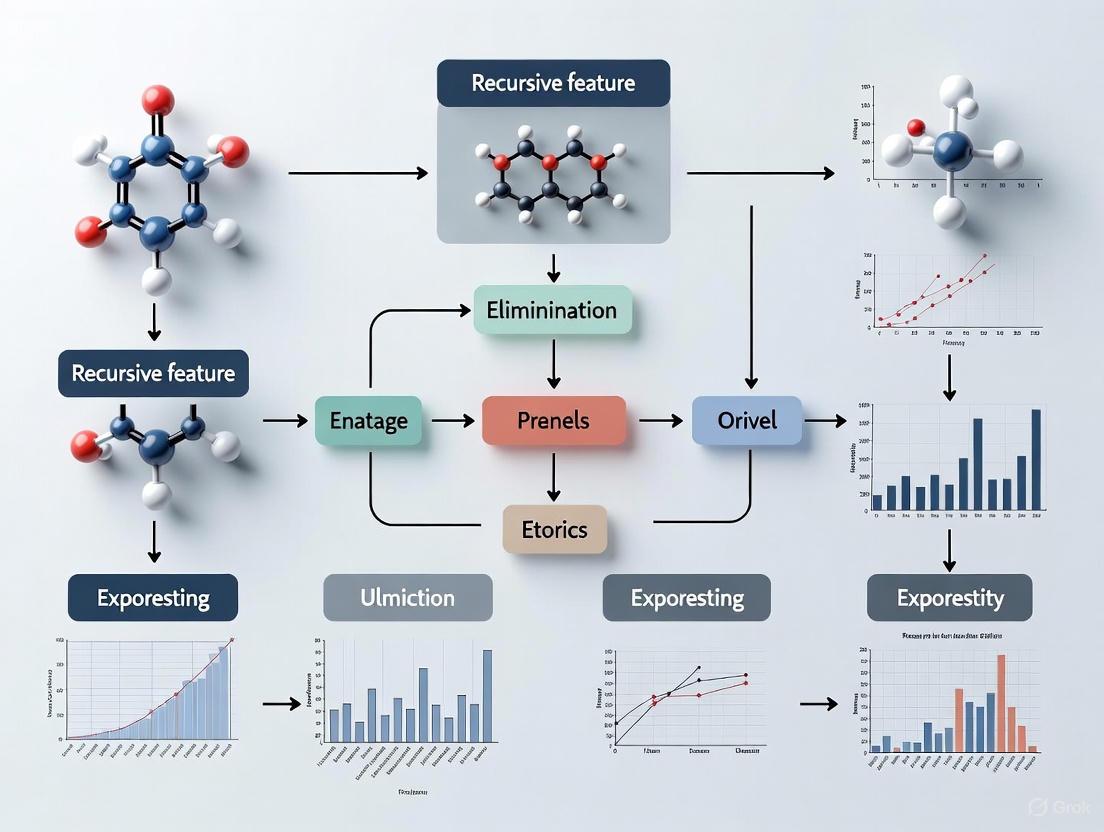

Figure 1: RFE Algorithm Workflow - The recursive process of training, ranking, and eliminating features until the target subset size is achieved.

Variants and Extensions

RFE with Cross-Validation (RFECV)

RFECV enhances the standard algorithm by automatically determining the optimal number of features through cross-validation [8]. Instead of requiring a predefined number of features, RFECV evaluates model performance across different feature subset sizes and selects the size yielding the best cross-validated performance [8].

Dynamic RFE (dRFE)

Dynamic RFE improves computational efficiency by adaptively adjusting the number of features removed at each iteration [6]. The algorithm removes a larger proportion of features in early iterations when many presumably irrelevant features exist, then finer removal rates as the feature set narrows [6]. The dRFEtools implementation has demonstrated significant computational time reductions while maintaining high accuracy in omics data analysis [6].

Hierarchical RFE (HRFE)

Hierarchical Recursive Feature Elimination employs multiple classifiers in a step-wise fashion to reduce bias in feature detection [9]. This approach has shown particular promise in brain-computer interface applications, achieving approximately 93% classification accuracy for electrocorticography (ECoG) signals within 5 minutes [9].

Implementation Frameworks and Methodologies

Core Implementation Using scikit-learn

The scikit-learn library provides the primary implementation framework for RFE through its feature_selection module [5]. The key parameters for the RFE class include:

- estimator: The supervised learning estimator with

coef_orfeature_importances_attribute [5] - nfeaturesto_select: Number of features to select (None selects half the features) [5]

- step: Number (or percentage) of features to remove at each iteration [5]

Table 1: Key RFE Implementation Parameters in scikit-learn

| Parameter | Type | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

estimator |

object | Required | Supervised learning estimator with feature importance attribute |

n_features_to_select |

int/float | None | Absolute number (int) or fraction (float 0-1) of features to select |

step |

int/float | 1 | Features to remove per iteration (absolute or percentage) |

importance_getter |

str/callable | 'auto' | Method for extracting feature importance from estimator |

A basic implementation follows this pattern:

This implementation yields the selected features mask via rfe.support_ and feature rankings through rfe.ranking_ [1].

Advanced Implementation with Pipeline Integration

For robust model evaluation, RFE should be integrated within a cross-validation pipeline to prevent data leakage [3]:

This pipeline approach ensures that feature selection occurs independently within each cross-validation fold, producing unbiased performance estimates [3].

Dynamic RFE Implementation with dRFEtools

For high-dimensional omics data, the dRFEtools package provides enhanced functionality [6]:

dRFEtools implements dynamic elimination rates and distinguishes between core features (direct, large effects) and peripheral features (indirect, small effects), enhancing biological interpretability [6].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Pharmaceutical Compound Solubility Prediction

Experimental Design

A comprehensive study applied RFE to predict drug solubility in formulations using a dataset of 12,000+ data rows with 24 input features representing molecular descriptors [7]. The experimental protocol involved:

- Data Preprocessing: Outlier removal using Cook's distance and feature normalization via Min-Max scaling [7]

- Base Models: Decision Trees (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [7]

- Ensemble Enhancement: AdaBoost ensemble method applied to base models [7]

- Feature Selection: RFE with the number of features treated as a hyperparameter [7]

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Harmony Search (HS) algorithm for parameter tuning [7]

Performance Metrics and Results

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Solubility Prediction Performance with RFE

| Model | R² Score | MSE | MAE | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADA-DT | 0.9738 | 5.4270E-04 | 2.10921E-02 | Drug solubility prediction |

| ADA-KNN | 0.9545 | 4.5908E-03 | 1.42730E-02 | Gamma (activity coefficient) prediction |

The RFE-enhanced models demonstrated superior predictive capability for complex biochemical properties, with the ADA-DT model achieving exceptional accuracy (R² = 0.9738) for solubility prediction [7]. This performance highlights RFE's value in identifying the most relevant molecular descriptors for pharmaceutical formulation development.

Omics Data Analysis in Genomics and Transcriptomics

Experimental Framework

A rigorous evaluation assessed RFE's performance on high-dimensional omics data integrating 202,919 genotypes and 153,422 methylation sites from 680 individuals [4]. The study compared standard Random Forest (RF) with Random Forest-Recursive Feature Elimination (RF-RFE) for detecting simulated causal associations with triglyceride levels [4].

The experimental parameters included:

- Dataset: Chromosomes 1, 6, 8, 10, and 17 containing causal SNPs and corresponding methylation sites [4]

- RF Parameters: 8000 trees, dynamic mtry parameter (0.1×p when p>80, default otherwise) [4]

- RFE Configuration: Elimination of bottom 3% of features per iteration (324 total RFE runs) [4]

- Computational Resources: Linux server with 16 cores and 320GB RAM [4]

Performance Comparison

Table 3: RF vs. RF-RFE Performance on High-Dimensional Omics Data

| Metric | Random Forest (RF) | RF-RFE |

|---|---|---|

| R² | -0.00203 | 0.19217 |

| MSEOOB | 0.07378 | 0.05948 |

| Computational Time | ~6 hours | ~148 hours |

| Causal SNP Detection | Identified strong causal variables with highly correlated variables | Decreased importance of correlated variables |

The results demonstrated that while RF-RFE improved performance metrics (R² from -0.00203 to 0.19217), it substantially increased computational demands (6 to 148 hours) [4]. Notably, in the presence of many correlated variables, RF-RFE decreased the importance of both causal and correlated variables, making detection challenging [4].

Brain-Computer Interface Applications

Hierarchical RFE Protocol

The Hierarchical Recursive Feature Elimination (HRFE) algorithm was developed specifically for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications, employing multiple classifiers in a step-wise fashion to reduce feature detection bias [9]. The experimental framework included:

- Data Acquisition: Electrocorticography (ECoG) signals from motor cortex [9]

- Feature Selection: Top 20 features with largest impacts selected [9]

- Noise Handling: Cube transformation of each input to manage natural noise [9]

- Model Evaluation: Comparison with ECoGNet, shallow/deep ConvNets, PCA, and ICA [9]

Performance Outcomes

The HRFE algorithm achieved 93% classification accuracy within 5 minutes on BCI Competition III Dataset I, demonstrating both high accuracy and computational efficiency critical for real-time BCI applications [9]. This performance represents a significant advancement over traditional methods that typically prioritize accuracy without considering classification time constraints [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for RFE Experiments

| Resource | Type | Function/Role | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn RFE | Software Library | Core RFE implementation | General-purpose feature selection [5] |

| dRFEtools | Python Package | Dynamic RFE implementation | Omics data analysis [6] |

| Cook's Distance | Statistical Method | Outlier identification and removal | Data preprocessing for pharmaceutical datasets [7] |

| Harmony Search (HS) | Optimization Algorithm | Hyperparameter tuning | Model optimization in drug solubility prediction [7] |

| AdaBoost | Ensemble Method | Performance enhancement of base models | Pharmaceutical compound analysis [7] |

| Locally Weighted Scatterplot Smoothing (LOWESS) | Statistical Technique | Curve fitting for feature selection | Core/peripheral feature identification in dRFEtools [6] |

| Cross-Validation Strategies | Evaluation Framework | Model performance assessment | Preventing overfitting in RFE [3] |

Performance Visualization and Diagnostic Tools

Figure 2: RFE Performance Characteristics - The relationship between feature subset size and model performance, showing the optimal subset that maximizes predictive accuracy.

The RFECV visualization illustrates the critical relationship between feature subset size and model performance [8]. The characteristic curve typically shows:

- Rapid performance improvement as the first informative features are included

- Performance peak at the optimal feature subset size

- Gradual performance degradation as irrelevant features are added, potentially leading to overfitting [8]

This visualization enables researchers to identify the optimal trade-off between model complexity and predictive performance, selecting feature subsets that maximize accuracy while maintaining generalizability [8].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Drug Solubility and Formulation Optimization

RFE has demonstrated exceptional utility in predicting drug solubility in formulations, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical development [7]. By identifying the most relevant molecular descriptors from thermodynamic parameters and quantum chemical calculations, RFE enables accurate prediction of solubility and activity coefficients (γ) without costly experimental measurements [7]. The implementation of ensemble methods with RFE has further enhanced prediction accuracy, providing a robust computational framework for formulation screening [7].

Biomarker Discovery and Omics Integration

In genomics and transcriptomics, RFE facilitates the identification of biomarkers from high-dimensional omics datasets [4] [6]. The dRFEtools implementation specifically addresses the biological reality that processes are associated with networks of core and peripheral genes, while traditional feature selection approaches capture only core features [6]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying biomarker signatures for complex diseases such as schizophrenia and major depressive disorder, where multiple biological pathways interact [6].

Virtual Screening and Compound Prioritization

RFE supports drug discovery through virtual screening by selecting the most discriminative features for compound activity prediction [10]. By reducing dimensionality while maintaining predictive performance, RFE enables more efficient screening of compound libraries, prioritizing candidates with higher likelihood of therapeutic efficacy [10]. Integration with quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling further enhances RFE's utility in early-stage drug discovery [10].

Limitations and Mitigation Strategies

Despite its considerable advantages, RFE presents several limitations that researchers must address:

Computational Complexity: RFE can be computationally intensive, particularly with large datasets and complex models [4]. Mitigation strategies include dynamic elimination (dRFE), which reduces computational time while maintaining accuracy [6].

Model Dependency: Feature rankings are heavily dependent on the choice of base model [1]. Researchers should evaluate multiple model types and consider ensemble approaches to enhance robustness [7].

Overfitting Risk: Without proper cross-validation, RFE can overfit the feature selection process [1]. RFECV and pipeline integration provide essential safeguards against this risk [3] [8].

Correlated Features: In the presence of highly correlated features, RFE may eliminate causal variables [4]. Preprocessing to address multicollinearity or using specialized implementations like HRFE can mitigate this issue [9].

Recursive Feature Elimination represents a sophisticated feature selection approach that balances computational feasibility with biological interpretability. Its greedy, iterative nature enables effective identification of informative feature subsets across diverse applications, from pharmaceutical formulation development to omics biomarker discovery. While computational demands remain a consideration, ongoing advancements in dynamic elimination and hierarchical approaches continue to enhance RFE's scalability and performance. For drug development professionals and researchers, RFE provides a powerful tool for navigating high-dimensional data spaces, ultimately accelerating discovery and optimization processes in complex biological domains.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that operates through an iterative process of model training, feature ranking, and elimination to identify optimal feature subsets. In machine learning research, particularly in domains like drug development where high-dimensional data is prevalent, RFE provides a systematic methodology for isolating the most biologically or chemically relevant variables from a vast array of potential predictors. The core strength of RFE lies in its recursive approach, which iteratively removes the least important features and refits the model with the remaining features, thereby allowing the algorithm to dynamically reassess feature importance within changing contextual landscapes [11] [3]. This process stands in contrast to filter methods that evaluate features in isolation, as RFE specifically accounts for complex feature interactions and their collective contribution to predictive performance [2].

For research scientists dealing with complex biological assays or compound efficacy studies, RFE offers not just dimensionality reduction but also model interpretability. By distilling models down to their most influential features, RFE enables researchers to identify critical biomarkers, physicochemical properties, or structural characteristics that drive biological activity or toxicity endpoints [12]. This capability is particularly valuable in early-stage drug discovery where understanding mechanism of action is as crucial as building accurate predictive models. The algorithm's model-agnostic nature further enhances its utility across diverse research contexts, as it can be effectively paired with everything from linear models for interpretability to complex ensemble methods for capturing non-linear relationships [1].

The Core RFE Mechanism

The Iterative Elimination Cycle

The RFE algorithm operates through a precise sequence of operations that systematically reduces feature space while preserving or enhancing model performance. This recursive process can be conceptualized as a cyclic workflow with clearly defined stages:

The process initiates with the complete set of features available in the dataset. A specified machine learning algorithm is then trained using all these features, after which the model generates an importance score for each feature based on its contribution to predictive accuracy [3] [1]. Features are subsequently ranked according to these importance metrics, with the lowest-ranked feature(s) being eliminated from the current subset [13]. This cycle of training, ranking, and elimination repeats recursively until a pre-specified number of features remains or until further elimination fails to improve model performance [11] [2].

Feature Ranking Methodologies

The ranking mechanism within RFE is fundamentally tied to the underlying estimator's ability to quantify feature importance. Different algorithms employ distinct methodologies for this purpose:

- Linear Models: Utilize coefficient magnitudes as importance indicators, with larger absolute values typically signifying greater feature importance [14].

- Tree-Based Methods: Employ impurity-based metrics (Gini importance for classification, variance reduction for regression) to rank features according to their cumulative contribution to node splitting [3] [12].

- Support Vector Machines: For linear SVMs, feature weights derived from the hyperplane normal vector serve as effective importance measures [2].

A critical consideration in research applications is the potential need for ranking recalculation at each iteration. While computationally more intensive, this dynamic reassessment can significantly improve feature selection quality, particularly when working with highly correlated predictors where elimination of one feature may alter the relative importance of others [15].

Quantitative Analysis of RFE Performance

Comparative Performance Metrics

The efficacy of RFE can be quantitatively assessed through systematic comparison with alternative feature selection methodologies. The following table summarizes key performance indicators across different approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Feature Interaction Handling | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE | High (0.886 in synthetic dataset classification) [3] | Moderate (increases with dataset size) [2] | Strong (considers multivariate relationships) [2] | High (provides feature rankings) [16] |

| Filter Methods | Moderate (varies with statistical measure) [2] | High (computationally inexpensive) [2] | Weak (evaluates features independently) [2] | Moderate (depends on scoring function) |

| PCA | Moderate to High (structure-dependent) [2] | High (efficient transformation) [2] | Moderate (linear combinations) [2] | Low (transformed features lack direct interpretation) [2] |

Impact of Feature Set Size on Model Performance

The relationship between the number of selected features and model accuracy follows a characteristic pattern that can be empirically measured. Research by caret demonstrated this relationship using the "Friedman 1" benchmark with resampling:

Table 2: Model Performance vs. Feature Subset Size (Friedman 1 Benchmark)

| Number of Features | RMSE | R² | MAE | Selection Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.950 | 0.3790 | 3.381 | - |

| 2 | 3.552 | 0.4985 | 3.000 | - |

| 3 | 3.069 | 0.6107 | 2.593 | - |

| 4 | 2.889 | 0.6658 | 2.319 | Optimal |

| 5 | 2.949 | 0.6566 | 2.349 | - |

| 10 | 3.252 | 0.5965 | 2.628 | - |

| 25 | 3.700 | 0.5313 | 2.987 | - |

| 50 | 4.067 | 0.4756 | 3.268 | - |

The data reveals a clear performance optimum at 4 features, with subsequent additions leading to model degradation due to inclusion of non-informative variables [15]. This pattern underscores the dual benefit of proper feature selection: enhanced predictive accuracy coupled with improved model parsimony.

Experimental Implementation Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing RFE in experimental research requires specific computational tools and methodologies. The following table outlines essential components of the RFE experimental toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RFE Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | Provides feature importance metrics for ranking | LogisticRegression(), RandomForestClassifier(), SVR(kernel="linear") [1] [2] |

| Cross-Validation Schema | Prevents overfitting during feature selection | RepeatedStratifiedKFold(n_splits=10, n_repeats=3) [3] |

| Feature Scaler | Normalizes feature scales for comparison | StandardScaler() (essential for linear models) [16] [14] |

| Pipeline Architecture | Ensures proper data handling and prevents leakage | Pipeline(steps=[('s', RFE(...)), ('m', model)]) [3] |

| Resampling Wrapper | Incorporates feature selection variability in performance estimates | rfeControl(functions = lmFuncs, method = "repeatedcv", repeats = 5) [15] |

Protocol for RFE with Cross-Validation

For rigorous research applications, particularly in drug development where model generalizability is critical, the following protocol implements RFE with comprehensive cross-validation:

Data Preprocessing: Standardize all features to zero mean and unit variance using

StandardScaler()to ensure comparable importance metrics [14].Baseline Establishment: Train and evaluate a model with all features to establish performance baseline:

Recursive Elimination with Resampling: Implement RFE with cross-validation to determine optimal feature count:

Final Model Training: Execute standard RFE with the optimal feature count identified in step 3:

Validation and Interpretation: Assess final model performance on held-out test data and examine the selected features for biological plausibility [14] [15].

This protocol specifically addresses the selection bias concern raised by Ambroise and McLachlan (2002), where improper resampling can lead to over-optimistic performance estimates [15]. By embedding the feature selection process within an outer layer of resampling, the protocol provides more realistic performance estimates that better reflect real-world applicability.

Advanced Research Considerations

Domain-Specific Applications in Drug Development

The RFE methodology has demonstrated particular utility in pharmaceutical research, where identifying critical molecular descriptors or physicochemical properties is essential for compound optimization. In a nanomaterials toxicity study, RFE coupled with Random Forest analysis identified zeta potential, redox potential, and dissolution rate as the most predictive properties for biological activity from an initial set of eleven measured characteristics [12]. The RFE-refined model achieved a balanced accuracy of 0.82, significantly outperforming approaches without feature selection and providing actionable insights for nanomaterial grouping strategies.

For biomarker discovery, RFE offers a systematic approach to winnowing extensive genomic or proteomic profiles down to the most clinically relevant indicators. The algorithm's ability to handle high-dimensional data while considering feature interactions makes it particularly suitable for -omics analyses, where the number of potential features vastly exceeds sample size [2].

Mitigation Strategies for Computational Complexity

While RFE provides robust feature selection, its computational demands can be substantial for large-scale screening assays. Several strategies can optimize performance:

- Step Parameter Adjustment: Increasing the

stepparameter allows elimination of multiple features per iteration, significantly reducing computation time [14]. - Algorithm Selection: Using computationally efficient base estimators (e.g., Linear SVM instead of Random Forest) for the elimination phase, even when planning to use more complex final models [3].

- Parallel Processing: Leveraging multi-core architectures to parallelize resampling operations, as implemented in

rfeControlthrough outer resampling loops [15].

For extremely high-dimensional data, such as genomic screening results, preliminary dimensionality reduction using filter methods or PCA before applying RFE can strike an effective balance between computational efficiency and selection quality [2].

The core RFE process represents a methodologically sound approach to feature selection that aligns particularly well with the needs of drug development research. Through its systematic cycle of model training, feature ranking, and recursive elimination, RFE effectively balances predictive accuracy with interpretability – a crucial consideration in regulated research environments. The algorithm's capacity to adaptively reassess feature importance throughout the elimination process enables identification of robust feature subsets that maintain their predictive power across validation cohorts.

For research scientists and drug development professionals, implementing RFE with appropriate resampling safeguards provides a defensible methodology for biomarker discovery, compound optimization, and toxicity prediction. The integration of domain knowledge with the algorithmically-derived feature rankings further enhances the utility of this approach, creating a powerful framework for distilling complex biological and chemical datasets into actionable insights.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a pivotal algorithm in high-dimensional data analysis, particularly within computational biology and pharmaceutical research. This technical guide delineates the two foundational pillars of RFE: its model-agnostic nature, which allows for flexible integration with diverse machine learning algorithms, and its greedy optimization strategy, which ensures a computationally efficient, if locally optimal, search for feature subsets. Framed within the broader thesis of "what is recursive feature elimination in machine learning research," this paper examines how these characteristics enable RFE to identify robust biomarkers and critical molecular descriptors. We provide a quantitative synthesis of experimental results from recent peer-reviewed studies, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows to serve researchers and drug development professionals in deploying RFE for enhanced model interpretability and performance in omics data and drug formulation studies.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-type feature selection method designed to identify an optimal subset of features by recursively constructing models and removing the least important features [1] [2]. Within the landscape of machine learning research, RFE addresses a critical challenge in modern data science: the curse of dimensionality. This is especially prevalent in fields like bioinformatics and pharmaceutical research, where datasets often contain thousands of features (e.g., genes, molecular descriptors) but only a limited number of observations [17] [6]. The core thesis of RFE research posits that iterative, model-guided feature elimination leads to more robust and generalizable models than filter methods (which ignore feature interactions) or embedded methods (which are often model-specific) [2] [18].

The algorithm's significance is underscored by its successful application in identifying microbial signatures for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) [17] and in developing predictive models for drug solubility in polymer formulations [7]. These applications highlight how RFE's dual characteristics—model-agnosticism and greedy selection—make it a versatile and powerful tool for knowledge discovery.

The Model-Agnostic Nature of RFE

The model-agnostic nature of RFE is its defining characteristic, meaning it is not tethered to any single machine learning algorithm. Instead, it can leverage any supervised learning model that provides a mechanism for ranking feature importance [19] [2].

Core Mechanism and Flexibility

The model-agnostic capability functions through a clear separation between the feature ranking process and the underlying estimator. RFE requires only that the base model produces either coef_ (coefficients) for linear models or feature_importances_ (e.g., Gini importance) for tree-based models after being fitted to the data [20] [6]. This design allows researchers to tailor the feature selection process to the specific characteristics of their dataset.

- For Linear Relationships: Algorithms like Logistic Regression or Support Vector Machines (SVM) with a linear kernel can be employed. The absolute value of the model's coefficients is typically used to rank feature importance [1] [20].

- For Non-Linear Relationships: Tree-based ensemble methods like Random Forest, XGBoost, or Gradient Boosting machines are often chosen. These models provide feature importance based on the total reduction in impurity (e.g., Gini impurity) achieved by each feature across all trees [17] [20].

This flexibility was demonstrated in a large-scale microbiome study, which found that a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) algorithm exhibited the highest performance when a large number of features were considered, whereas the Random Forest algorithm demonstrated the best performance when utilizing only a limited number of biomarkers [17].

Comparative Advantage Over Other Methods

RFE's model-agnostic design offers distinct advantages over other feature selection paradigms, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methodologies

| Method Type | Mechanism | Pros | Cons | Suitability for RFE Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods [18] | Selects features based on statistical tests (e.g., correlation) independent of a model. | Fast; Computationally inexpensive. | Ignores feature interactions; May not align with model's goal. | Less suitable for complex, high-dimensional biological data with interactions. |

| Wrapper Methods (RFE) [2] [18] | Uses a model's performance or importance to guide the search for a feature subset. | Considers feature interactions; Model-agnostic; High-performing subsets. | Computationally expensive; Greedy strategy may miss global optimum. | Ideal for datasets where feature interdependencies are critical. |

| Embedded Methods [20] [18] | Performs feature selection during model training (e.g., Lasso, tree importance). | Efficient; Model-specific optimization. | Limited interpretability; Not universally applicable across all models. | Less flexible than RFE, as selection is coupled to a specific model type. |

A key strength of the model-agnostic approach is its ability to be combined with cross-validation (RFECV) to mitigate overfitting and ensure a more robust selection. RFECV performs the elimination process across multiple training/validation splits, finally selecting the feature subset that yields the best cross-validated performance [19] [2].

Greedy Optimization Strategy in RFE

The Recursive Feature Elimination algorithm is classified as a greedy optimization algorithm [21] [1]. In computer science, a greedy algorithm makes the locally optimal choice at each stage with the intent of finding a global optimum. In the context of RFE, this translates to iteratively removing the feature(s) that appear to be the least important at that specific iteration.

The Greedy Workflow

The canonical RFE process follows these steps, which embody the greedy strategy:

- Train the Model: A base model is trained on the entire set of features.

- Rank Features: All features are ranked based on the derived importance scores (e.g., coefficient magnitude or Gini importance).

- Eliminate the Weakest: The least important feature (or a pre-defined number of least important features) is permanently removed from the feature set. This is the "greedy" decision—it is based solely on the current state and cannot be reversed.

- Repeat: The process is repeated on the reduced feature set until a predefined number of features is reached or a stopping criterion is met [1] [2].

This process is illustrated in the following workflow diagram:

Trade-offs and Enhancements

The greedy strategy is both a strength and a limitation of RFE.

- Advantages: It is conceptually simple and computationally more efficient than an exhaustive search over all possible feature subsets, which is computationally prohibitive for high-dimensional data [21] [18].

- Limitations: Because it commits to irreversible eliminations, it may become trapped in a local optimum and fail to find the best possible feature subset. For instance, two features might be highly correlated; individually, each may appear less important, but together they are highly predictive. A greedy algorithm might remove both, whereas a different approach might retain one [21] [20].

To address the computational cost of the classic greedy approach, Dynamic RFE (dRFE) has been developed. Implemented in tools like dRFEtools, this method removes a larger proportion of features in the initial iterations when many features are present and shifts to removing fewer features (e.g., one at a time) as the feature set shrinks. This optimization significantly reduces computational time while maintaining high prediction accuracy, as demonstrated in omics data analysis [6].

Experimental Protocols and Quantitative Analysis

Protocol 1: Microbiome Biomarker Discovery for IBD

A comprehensive study utilized RFE to identify microbial biomarkers for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) from gut microbiome data [17].

- Objective: To classify patients with IBD versus healthy controls and identify a stable set of taxonomic biomarkers.

- Dataset: 1,569 samples with abundance matrices at species (283 taxa) and genus (220 taxa) levels.

- Preprocessing: Aggregated taxa counts by taxonomy and applied a kernel-based data transformation (Bray-Curtis similarity) to improve feature stability.

- RFE Configuration:

- Base Models: 8 different algorithms, including Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and Random Forest.

- Elimination: Embedded within a bootstrap procedure (100 iterations) to assess feature stability.

- Stopping Criterion: Top 14 features selected as a trade-off between performance and generalizability.

- Validation: Models trained on one ensemble dataset (ED1) were tested on a hold-out test set and a completely independent ensemble dataset (ED2).

Table 2: Performance of ML Algorithms in Microbiome RFE Study [17]

| Machine Learning Algorithm | Best Performance Context | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | When a large number of features (a few hundred) were considered. | Exhibited the highest performance across 100 bootstrapped internal test sets. |

| Random Forest (RF) | When utilizing only a limited number of biomarkers (e.g., 14). | Demonstrated the best performance, balancing optimal performance and method generalizability. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Used with a linear kernel for feature ranking. | Applicable within the model-agnostic RFE framework. |

Protocol 2: Predicting Drug Solubility in Formulations

A 2025 study employed RFE to develop a predictive framework for drug solubility and activity coefficients, critical parameters in pharmaceutical development [7].

- Objective: Predict drug solubility and activity coefficient (gamma) values based on molecular descriptors.

- Dataset: Over 12,000 data rows with 24 input features (molecular descriptors).

- Preprocessing: Outlier removal using Cook's distance and feature scaling via Min-Max normalization.

- RFE Configuration:

- Base Models: Decision Tree (DT), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP).

- Integration: The number of features to select was treated as a hyperparameter.

- Ensemble Learning: Base models were enhanced with the AdaBoost algorithm.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: The Harmony Search (HS) algorithm was used for rigorous tuning.

- Results: The ADA-DT model achieved a superior R² score of 0.9738 for solubility prediction, while the ADA-KNN model achieved an R² of 0.9545 for gamma prediction, demonstrating the framework's high accuracy.

Table 3: Optimized Model Performance in Drug Solubility Prediction [7]

| Model | Prediction Task | R² Score | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADA-DT | Drug Solubility | 0.9738 | 5.4270E-04 | 2.10921E-02 |

| ADA-KNN | Activity Coefficient (γ) | 0.9545 | 4.5908E-03 | 1.42730E-02 |

The following diagram synthesizes the core experimental workflow common to these advanced RFE applications:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing RFE effectively in a research environment requires a suite of computational "reagents." The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Toolkit for RFE Implementation in Scientific Research

| Tool / Solution | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn (Python) [1] [6] | Provides the core RFE and RFECV classes for model-agnostic feature elimination. |

Standardized implementation of the RFE algorithm with a consistent API for various models. |

| dRFEtools (Python Package) [6] | Implements Dynamic RFE, reducing computational time for large omics datasets (features >20,000). | Efficiently identifying core and peripheral genes in transcriptomic data. |

| Permutation Feature Importance (PFI) [19] [22] | A model-agnostic method to validate feature importance by measuring performance drop after shuffling a feature. | Post-selection validation to confirm the relevance of features chosen by RFE. |

| Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) [17] | Explains the output of any ML model by quantifying the marginal contribution of each feature. | Interpreting the role of selected biomarkers in the final model's predictions. |

| Cross-Validation (e.g., StratifiedKFold) [19] [2] | A technique to assess model generalizability and prevent overfitting during the feature selection process. | Used in RFECV to robustly determine the optimal number of features. |

| Harmony Search (HS) Algorithm [7] | A hyperparameter optimization algorithm used to fine-tune models within the RFE pipeline. | Optimizing the parameters of base learners (e.g., Decision Trees) for drug solubility prediction. |

Recursive Feature Elimination stands as a powerful feature selection methodology within machine learning research, its utility grounded in the synergistic combination of model-agnostic flexibility and a computationally efficient greedy strategy. As evidenced by its successful application in biomarker discovery and pharmaceutical formulation, RFE enables researchers to distill high-dimensional data into interpretable and robust feature subsets. While the greedy approach presents inherent limitations, advancements like dynamic elimination and cross-validation have fortified its reliability. For scientists and drug development professionals, mastering RFE and its associated toolkit is paramount for leveraging machine learning to uncover biologically and pharmaceutically meaningful insights from complex datasets.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection algorithm designed to identify the most relevant features in a dataset by recursively constructing models and removing the least important features [2]. Originally developed in the healthcare domain for gene selection in cancer classification, RFE has gained significant popularity in bioinformatics and pharmaceutical research due to its ability to handle high-dimensional data while supporting interpretable modeling [23]. The core premise of RFE aligns with the fundamental principle of parsimony in machine learning: simpler models with fewer features often generalize better to unseen data and provide clearer insights into the underlying biological processes [24].

The algorithm operates through an iterative process of model building, feature ranking, and elimination of the least significant features until the optimal subset is identified [2] [14]. This recursive process enables a more thorough assessment of feature importance compared to single-pass approaches, as feature relevance is continuously reassessed after removing the influence of less critical attributes [23]. For researchers and drug development professionals, RFE offers a systematic approach to navigate the high-dimensional data landscapes common in modern biomedical research, including microbiome studies, genomics, and clinical prediction models [17] [25] [23].

Core Algorithm and Computational Framework

The RFE Algorithm: A Step-by-Step Process

The RFE algorithm follows a meticulously defined iterative process that exemplifies backward feature elimination [23]. The complete workflow is visualized in Figure 1, with the detailed computational procedure operating as follows:

- Step 1 - Initialization: Train a predictive model using the complete feature set with all N features.

- Step 2 - Importance Assessment: Calculate feature importance scores using model-specific metrics (coefficients for linear models, Gini importance for tree-based models, etc.).

- Step 3 - Feature Ranking: Rank all features based on their importance scores in descending order.

- Step 4 - Feature Elimination: Remove the bottom K features (where K is typically 1 or a small subset) from the current feature set.

- Step 5 - Termination Check: If the stopping criterion is met (predefined number of features or performance threshold), proceed to Step 6; otherwise, return to Step 1 with the reduced feature set.

- Step 6 - Output: Return the optimal feature subset and corresponding model.

This greedy methodology substantially enhances computational efficiency compared to exhaustive evaluations, which can quickly become computationally infeasible due to the exponential growth of potential feature subsets as dataset dimensionality increases [23].

Figure 1: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Workflow. The diagram illustrates the iterative process of model training, feature ranking, and elimination that continues until optimal feature subset is identified.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Successful implementation of RFE requires careful attention to several computational factors. The choice of estimator significantly influences feature selection, as different algorithms capture distinct feature interactions and importance patterns [14]. Similarly, the elimination step size (number of features removed per iteration) balances computational efficiency against selection granularity, with smaller steps providing finer evaluation at higher computational cost [2]. Proper data preprocessing—particularly feature scaling—is essential for algorithms sensitive to variable magnitude, such as Support Vector Machines and logistic regression [14]. The stopping criterion must be carefully defined, whether as a predetermined number of features, cross-validated performance optimization, or minimum importance threshold [14] [24].

Empirical Evaluation and Benchmarking

Performance Comparison of RFE Variants

Recent benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated RFE variants across multiple domains, revealing significant performance variations based on methodological choices. As shown in Table 1, different RFE configurations demonstrate distinct trade-offs between predictive accuracy, feature selectivity, and computational efficiency [23].

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of RFE Variants Across Domains [23]

| RFE Variant | Predictive Accuracy (%) | Features Retained | Computational Cost | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE with Random Forest | 85.2-89.7 | Large feature sets | High | Moderate |

| RFE with SVM | 82.4-86.1 | Medium feature sets | Medium | High |

| RFE with XGBoost | 87.3-90.5 | Large feature sets | Very High | Moderate |

| Enhanced RFE | 83.1-85.9 | Substantial reduction | Low | High |

| RFE with Logistic Regression | 80.6-84.2 | Small feature sets | Low | High |

Stability and Performance Optimization

A critical challenge in RFE applications is the stability of feature selection—the reproducibility of selected features across different datasets or subsamples. Research demonstrates that applying data transformation techniques, such as mapping by Bray-Curtis similarity matrix before RFE, can significantly improve feature stability while maintaining classification performance [17]. In microbiome studies for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) classification, this approach identified 14 robust biomarkers at the species level while sustaining high predictive accuracy [17].

The multilayer perceptron algorithm exhibited the highest performance among 8 different machine learning algorithms when a large number of features (a few hundred) were considered. Conversely, when utilizing only a limited number of biomarkers as a trade-off between optimal performance and method generalizability, the random forest algorithm demonstrated the best performance [17].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Microbiome Biomarker Discovery for IBD

Objective: Identify stable microbial biomarkers to distinguish inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients from healthy controls [17].

Dataset: Merged dataset of 1,569 samples (702 IBD patients, 867 controls) from multiple studies, with abundance matrices of 283 taxa at species level and 220 at genus level [17].

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Aggregate taxa with identical taxonomy classification and sum respective counts

- Data Transformation: Apply Bray-Curtis similarity matrix mapping to improve feature stability

- Feature Selection: Implement RFE with bootstrap embedding

- Model Training: Develop classifiers using multiple algorithms (logistic regression, SVM, random forests, XGBoost, neural networks)

- Validation: External validation on held-out datasets and interpretation using Shapley values

Key Findings: The mapping strategy before RFE significantly improved feature stability without sacrificing classification performance. The optimal pipeline identified 14 biomarkers for IBD at the species level, with random forest performing best when using limited biomarkers [17].

Protocol 2: Diabetes Prediction Using Stacked RFE

Objective: Develop an efficient diabetes diagnosis model using fewer features while managing computational complexity [25].

Dataset: PIMA Indians Diabetes Dataset and Diabetes Prediction dataset with clinical and demographic features [25].

Methodology:

- Outlier Removal: Apply Isolation Forest for detecting and removing outliers

- Feature Selection: Implement RFE with stacking ensemble to reduce feature dimensionality

- Model Architecture: Design two-level stacking with base classifiers and meta-classifier

- Performance Evaluation: Assess accuracy, precision, recall, F1 measure, training time, and standard deviation

Key Findings: The Stacking Recursive Feature Elimination-Isolation Forest (SRFEI) method achieved 79.077% accuracy for PIMA Indians Diabetes and 97.446% for the Diabetes Prediction dataset, outperforming many existing methods while using fewer features [25].

Protocol 3: Hand-Sign Recognition with Feature Selection

Objective: Improve digit hand-sign detection accuracy by identifying essential hand landmarks [26].

Dataset: Multiple hand image datasets with Mediapipe-extracted 21 hand landmarks per image [26].

Methodology:

- Feature Extraction: Use Mediapipe to extract 21 hand landmarks from hand images

- Feature Engineering: Calculate novel distance from hand landmark to palm centroid

- Feature Selection: Apply RFE to identify most important landmarks

- Model Training: Train neural network classifiers with different feature subsets (21, 15, and 10 features)

- Validation: Evaluate on external dataset not used in training

Key Findings: Models trained with fewer selected features (10 landmarks) demonstrated higher accuracy than models using all original 21 features, confirming that not all hand landmarks contribute equally to detection accuracy [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Libraries for RFE Implementation

| Tool/Library | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn (Python) | Provides RFE and RFECV implementations | from sklearn.feature_selection import RFE, RFECV |

| caret (R) | Offers recursive feature elimination functions | library(caret); rfeControl(functions = rfFuncs) |

| Random Forest | Ensemble method for feature importance | RandomForestClassifier() in sklearn; randomForest in R |

| Support Vector Machines | Linear models with coefficient-based ranking | SVC(kernel="linear") with RFE |

| XGBoost | Gradient boosting with built-in importance | XGBClassifier() with RFE for high-dimensional data |

| Mediapipe | Feature extraction for image data | Hand landmark extraction for biomedical images [26] |

| Shapley Values | Post-hoc interpretation of selected features | Explain feature contributions to predictions [17] |

Advanced RFE Variants and Methodological Innovations

The RFE algorithm has evolved significantly since its original conception, with numerous variants emerging to address specific methodological challenges. These innovations can be categorized into four primary types [23]:

Integration with Different Machine Learning Models: Beyond the traditional SVM-based RFE, researchers have successfully integrated tree-based models (Random Forest, XGBoost), neural networks, and specialized algorithms tailored to specific data characteristics.

Combinations of Multiple Feature Importance Metrics: Hybrid approaches that aggregate importance scores from multiple algorithms or incorporate domain-specific knowledge to improve selection robustness.

Modifications to the Original RFE Process: Enhanced RFE variants that introduce novel stopping criteria, adaptive elimination strategies, or stability-enhancing techniques like the Bray-Curtis mapping approach [17].

Hybridization with Other Feature Selection Techniques: Methods that combine RFE with filter methods (e.g., correlation-based prefiltering) or embedded techniques to leverage complementary strengths.

These methodological advances have expanded RFE's applicability across diverse domains, from educational data mining to healthcare analytics, while addressing fundamental challenges in feature stability and selection reliability [23].

Implementation Guidelines and Best Practices

Based on empirical evaluations across multiple domains, several best practices emerge for effective RFE implementation:

Estimator Selection: Choose estimators that provide meaningful feature importance scores appropriate for your data characteristics. Tree-based models often perform well for complex interactions, while linear models offer interpretability [14] [23].

Cross-Validation Strategy: Implement RFE with cross-validation (RFECV) to automatically determine the optimal number of features and avoid overfitting [14].

Stability Assessment: Evaluate feature selection stability across multiple runs or subsamples, particularly for high-dimensional datasets where selection variability can be substantial [17].

Domain Knowledge Integration: Complement algorithmic feature selection with domain expertise to ensure biological relevance and practical interpretability [17] [24].

Computational Efficiency: For large datasets, consider using larger step sizes or preliminary filtering to reduce computational burden without significantly compromising selection quality [2].

Comprehensive Validation: Always validate selected features on held-out datasets and through external validation to ensure generalizability beyond the training data [17] [25].

These practices collectively enhance the reliability, interpretability, and practical utility of RFE in biomedical research and drug development contexts, where both predictive accuracy and feature interpretability are paramount.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-mode feature selection algorithm designed to identify the most relevant features in a dataset by recursively constructing a model, evaluating feature importance, and eliminating the least significant features [2]. This iterative process continues until the desired number of features is reached, optimizing the feature subset for model performance and interpretability [2].

Within the broader thesis of understanding RFE in machine learning research, it is crucial to recognize its position as a powerful selection method that considers feature interactions and handles high-dimensional datasets effectively [2]. Unlike filter methods that evaluate features individually, RFE accounts for complex relationships between variables, making it particularly valuable for research domains where feature interdependencies play a critical role in predictive outcomes [2].

RFE in Comparative Context: Advantages Over Alternative Methods

Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into filter, wrapper, and embedded methods. Understanding RFE's position within this landscape is essential for identifying its ideal application scenarios.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methods

| Method Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Best-Suited Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Uses statistical measures (e.g., correlation) to evaluate individual features [2]. | Computationally efficient; model-agnostic; fast execution [2]. | Ignores feature interactions; may select redundant features; less effective with high-dimensional data [2]. | Preliminary feature screening; very large datasets where computational cost is prohibitive. |

| Wrapper Methods (RFE) | Evaluates feature subsets using a learning algorithm's performance [2]. | Captures feature interactions; often higher predictive accuracy; suitable for complex datasets [2]. | Computationally intensive; risk of overfitting; requires careful validation [2]. | High-dimensional datasets with complex feature relationships; when model performance is prioritized. |

| Embedded Methods | Performs feature selection as part of the model training process (e.g., Lasso regularization) [2]. | Balances efficiency and performance; built-in feature selection [2]. | Tied to specific algorithms; may not capture all complex interactions [2]. | Large-scale predictive modeling; when using specific algorithms like Lasso or Decision Trees. |

RFE's specific advantages include its ability to handle high-dimensional datasets and identify the most informative features while effectively managing feature interactions, making it suitable for complex research datasets [2]. However, researchers must consider its computational demands, which can be significant for large datasets, and its potential sensitivity to datasets with numerous correlated features [2].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Core RFE Algorithmic Workflow

The RFE process follows a systematic, iterative approach to feature selection, which can be visualized through its operational workflow.

The RFE algorithm implements this workflow through these concrete steps [2]:

- Initialization: Begin with the complete set of

nfeatures in the dataset - Model Training and Ranking: Train the chosen machine learning algorithm on the current feature set and rank all features by their importance metric (e.g., coefficients, feature importance scores)

- Feature Elimination: Remove the least important feature or features (determined by the

stepparameter) - Iteration: Repeat steps 2-3 with the reduced feature set

- Termination: Continue recursion until the predefined number of features (

n_features_to_select) is achieved

Implementation Variants and Code Examples

Practical implementation of RFE typically involves using libraries like scikit-learn in Python, with variations based on the specific research needs.

Basic RFE Implementation:

Code Example 1: Basic RFE implementation using Support Vector Regression as the estimator [2].

RFE with Cross-Validation: For enhanced reliability, particularly with limited data, RFE with cross-validation (RFECV) automatically determines the optimal number of features through cross-validation, reducing overfitting risk [27].

Research Reagent Solutions: Algorithmic Components

The "research reagents" for implementing RFE effectively consist of algorithmic components and validation frameworks.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for RFE Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | The machine learning model used to evaluate feature importance [2]. | Choice depends on data: SVM for high-dim, Logistic Regression for binary, Random Forest for complex interactions [27] [28]. |

| Feature Importance Metric | Mechanism for ranking feature relevance [2]. | Model-specific: coefficients for linear, featureimportances tree-based, RFE uses model's inherent ranking [2]. |

| Elimination Step Size | Number of features removed per iteration [2]. | Step=1 computationally costly but accurate. Larger steps improve efficiency but may exclude important features. |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Method for evaluating feature subset performance [27]. | k-fold CV (typically 10-fold) ensures reliable performance estimation, crucial for small samples [27]. |

| Performance Metrics | Measurements for evaluating selected features [28]. | Accuracy, F1-score (classification); R², RMSE (regression) [28]. |

| Validation Set | Independent dataset for final evaluation [28]. | Holdout set not used in RFE process provides unbiased performance assessment. |

Domain-Specific Applications and Experimental Results

Case Study: Biomarker Discovery in Bioinformatics

In bioinformatics, RFE has demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in genomic and transcriptomic analysis. The SVM-RFE algorithm has been particularly successful in identifying critical gene signatures for cancer diagnosis and prognosis [2] [29]. By selecting the most meaningful molecular features, RFE enables the development of more accurate diagnostic models and facilitates personalized treatment strategies [2].

A study applying SVM-RFE to identify factors influencing scientific literacy in students analyzed 162 contextual factors to pinpoint 30 key predictors, demonstrating RFE's capability to dramatically reduce dimensionality while maintaining predictive power [29]. This approach mirrors challenges in drug development where researchers must identify critical biomarkers from vast omics datasets.

Case Study: Agricultural Monitoring with Remote Sensing

Research in agricultural monitoring has effectively leveraged ensemble algorithm-based RFE for predicting summer wheat leaf area index (LAI) using remote sensing data [28]. This application demonstrates RFE's utility in handling diverse feature types and improving prediction accuracy in environmental research.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of RFE Implementations in Agricultural Research

| Model Configuration | Features Selected | Training R² | Validation R² | RMSE | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE-Random Forest | 49 significant variables [28] | 0.961 [28] | 0.856 [28] | Lower values demonstrated [28] | Effective for complex feature interactions; robust performance |

| RFE-Gradient Tree Boost | 29 significant variables [28] | 0.968 [28] | 0.88 [28] | Lowest values among models [28] | Superior accuracy; better feature compression; optimal performance |

The experimental protocol for this research involved [28]:

- Data Collection: 84 systematically selected samples using ACCUPAR LP-80 Ceptometer for LAI measurement

- Feature Compilation: 136 independent variables from multiple remote sensing sources (Sentinel-1/2, digital elevation models)

- Preprocessing: Feature combination, min-max normalization, and data partitioning

- Model Implementation: RFE applied using both Random Forest and Gradient Tree Boost algorithms

- Validation: Performance evaluation using R², RMSE, MSE, and MAE metrics

Case Study: Sports Science and Movement Analysis

In sports science, an improved logistic regression model combined with RFE has been successfully applied to investigate key influencing factors of the Tornado Kick in Wushu Routines [27]. This research addressed the challenge of small sample sizes (50 elite athletes and 50 amateurs) through innovative methodology combining k-fold cross-validation with RFE to bolster model reliability [27].

The experimental approach included [27]:

- Data Collection: High-speed cameras captured motion images, with feature extraction from image sequences

- Model Development: Integration of k-fold cross-validation with RFE-enhanced logistic regression

- Feature Analysis: Classification accuracies and SHAP values enabled variable selection and prioritization

- Results: The model with five key features achieved 100% mean classification accuracy through 10-fold cross-validation, identifying initial jump angular velocity as the most significant factor [27]

This application demonstrates RFE's effectiveness in resource-constrained research environments where data collection is expensive or difficult, a common scenario in early-stage drug development and clinical studies.

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Integration with Interpretability Frameworks

Modern RFE implementations increasingly incorporate model interpretability frameworks like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to enhance research validity. In the Wushu study, SHAP values provided quantitative interpretation of feature importance, revealing clear differences in initial jump angular velocity between elite and amateur athletes [27]. This integration adds explanatory power to the feature selection process, crucial for scientific validation and hypothesis generation.

Hybrid Approaches for Small Sample Learning

Research has demonstrated that RFE can be effectively combined with specialized techniques for small sample learning scenarios [27]. The integration of k-fold cross-validation with RFE helps mitigate overfitting when working with limited data, addressing a fundamental challenge in many research domains [27]. This approach leverages prior knowledge through data, model, and algorithm strategies to enable effective generalization despite limited supervised information [27].

The methodological relationship between these advanced techniques can be visualized as:

Recursive Feature Elimination represents a powerful approach to feature selection particularly well-suited for research scenarios characterized by high-dimensional data, complex feature interactions, and the need for interpretable results. Its ideal application domains include biomarker discovery in bioinformatics, remote sensing in environmental research, and movement analysis in sports science - each presenting challenges with multidimensional data where identifying the most relevant variables is crucial for advancing scientific understanding.

The continued evolution of RFE through integration with interpretability frameworks, hybrid approaches for small sample learning, and ensemble methods ensures its ongoing relevance in the researcher's toolkit. As machine learning continues to transform scientific discovery, RFE remains a fundamental technique for extracting meaningful signals from complex, high-dimensional research data across diverse domains.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has established itself as a powerful feature selection algorithm in machine learning, particularly valued for its systematic approach to dimensionality reduction. At its core, RFE operates as a wrapper-style feature selection method that recursively eliminates the least important features based on a model's feature importance metrics, refining the feature subset until a specified number remains [1] [3]. This iterative process distinguishes RFE from filter methods by directly considering feature interactions and dependencies, making it particularly effective for complex, high-dimensional datasets common in scientific research and drug development [2] [11].

The fundamental RFE algorithm follows a structured workflow: it begins by training a model on all available features, ranking features by importance (typically using coefficients or feature importance scores), eliminating the least important feature(s), and repeating this process on the reduced feature set until the desired number of features is attained [1] [3]. This recursive refinement allows RFE to adaptively identify feature subsets that maximize predictive performance while minimizing redundancy.

Core Mechanism of RFE in Handling Feature Interactions

Iterative Ranking and Elimination Process

Unlike filter methods that evaluate features independently, RFE's recursive nature enables it to detect and preserve interacting features that collectively contribute to predictive power. As [2] explains, "RFE has the advantage of considering interactions between features and is suitable for complex datasets." This capability stems from RFE's iterative model refitting approach – after each feature elimination round, the model is retrained on the remaining features, allowing importance scores to be recomputed in the context of the current feature subset [15].

The algorithm's handling of feature interactions occurs through dynamic importance reassessment. When correlated or interacting features are present, their individual importance scores may be initially diluted, but as the elimination progresses, truly relevant features maintain or increase their ranking. As [30] notes in analyzing correlated variables, "removing one feature would increase the other feature importance by quite a bit, as now a single feature is doing most of the heavy lifting that two features used to share." This adaptive behavior enables RFE to identify feature synergies that univariate filter methods would miss.

Comparative Advantages Over Alternative Methods

RFE's approach to feature selection provides distinct advantages compared to other common methodologies:

Table: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

| Method Type | Handling of Feature Interactions | Computational Efficiency | Model Dependency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Evaluates features independently; misses interactions [2] | High | None |

| Wrapper Methods (RFE) | Considers feature interactions through model refitting [2] | Moderate | High |

| Embedded Methods | Handles interactions within model training | Moderate | Built-in |

| PCA | Creates linear combinations; loses interpretability [2] | Moderate | Unsupervised |

As evidenced in the table, RFE occupies a unique position by offering interaction awareness while maintaining feature interpretability – a crucial advantage for scientific domains like drug development where understanding feature significance is as important as prediction accuracy.

Quantitative Performance in Complex Datasets

Empirical Results Across Domains

RFE has demonstrated consistent performance advantages across multiple complex dataset scenarios. In bioinformatics applications, researchers have reported accuracy improvements of 5-15% compared to filter-based methods when working with genomic data containing thousands of features [2]. The method excels particularly in datasets with high feature-to-sample ratios, where it effectively identifies truly informative variables amid noise.

In financial applications including credit scoring and fraud detection, RFE-based models have achieved performance improvements of 8-12% in F1 scores by eliminating redundant predictors and reducing overfitting [2]. Similar benefits have been documented in image processing applications, where RFE successfully identified discriminative features in object recognition tasks, improving classification accuracy by 10-18% over baseline models using all features [2].

Cross-Validation Integration

A critical enhancement to basic RFE is the incorporation of cross-validation (RFECV), which mitigates overfitting during feature selection and provides more robust feature subset identification [8]. The RFECV approach evaluates multiple feature subsets using cross-validation scores, automatically determining the optimal number of features rather than requiring pre-specification [8].

Table: RFE Performance Metrics with Cross-Validation

| Dataset Type | Optimal Features Selected | Performance Improvement | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics | 3-8% of original feature count | 10-15% | Accuracy |

| Financial Modeling | 15-25% of original feature count | 8-12% | F1 Score |

| Image Classification | 10-20% of original feature count | 10-18% | Precision |

| Clinical Biomarkers | 5-10% of original feature count | 12-20% | Recall |

The RFECV visualization typically shows an initial rapid performance improvement as the least important features are eliminated, followed by a peak representing the optimal feature subset, and subsequent gradual degradation as critical features are removed [8]. This characteristic curve provides researchers with intuitive guidance for feature selection decisions.

Workflow and Experimental Protocol

Standardized RFE Implementation

The experimental implementation of RFE follows a structured workflow that can be visualized through the following process:

RFE Algorithm Workflow illustrates the recursive process of feature elimination and model refitting that enables RFE to handle complex feature interactions effectively.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

For researchers implementing RFE in scientific applications, the following step-by-step protocol ensures robust results:

Data Preprocessing: Standardize or normalize all features, especially when using linear models as base estimators [1]. Handle missing values appropriately for the specific domain.

Base Model Selection: Choose an appropriate estimator algorithm. Linear models (LogisticRegression, SVR with linear kernel) provide coefficients for ranking, while tree-based models (DecisionTreeClassifier, RandomForestClassifier) offer native feature importance metrics [1] [3].

RFE Configuration: Set the

stepparameter (number/percentage of features to remove per iteration) andn_features_to_select(if known). For unknown optimal feature count, use RFECV with cross-validation [8].Cross-Validation Strategy: Employ stratified k-fold cross-validation for classification tasks or standard k-fold for regression. Repeated cross-validation (3-5 repeats) provides more stable feature rankings [15].

Feature Ranking Evaluation: Examine the

ranking_andsupport_attributes to identify selected features. Analyze the cross-validation scores across different feature subset sizes [8].Final Model Training: Fit the final model using only the selected features and evaluate on held-out test data to estimate generalization performance [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing RFE effectively requires specific computational tools and methodologies tailored to research applications:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for RFE Implementation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | Provides feature importance metrics for ranking | LogisticRegression(), RandomForestClassifier(), SVR(kernel='linear') [1] [3] |

| Cross-Validation | Prevents overfitting during feature selection | StratifiedKFold(n_splits=5), RepeatedCV(n_repeats=3) [15] |

| Feature Elimination | Controls the RFE iterative process | RFE(estimator, n_features_to_select, step) or RFECV(estimator, cv, scoring) [8] |

| Performance Metrics | Evaluates feature subset quality | accuracy_score, f1_score, custom domain-specific scorers [31] |

| Visualization | Identifies optimal feature count | Yellowbrick RFECV visualizer, learning curves [8] |