Re-evaluating PICADAR: Performance Limitations in Genetically Confirmed Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Diagnosis

This article critically examines the diagnostic performance of the PICADAR (PrImary CiliARy DyskinesiA Rule) prediction tool in cohorts with genetically confirmed Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD).

Re-evaluating PICADAR: Performance Limitations in Genetically Confirmed Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Diagnosis

Abstract

This article critically examines the diagnostic performance of the PICADAR (PrImary CiliARy DyskinesiA Rule) prediction tool in cohorts with genetically confirmed Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD). Recent evidence reveals significant limitations in PICADAR's sensitivity, particularly for patients without laterality defects or hallmark ultrastructural defects. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this analysis covers foundational principles, methodological application, troubleshooting of current limitations, and comparative validation against genetic testing. The synthesis underscores the urgent need for refined diagnostic algorithms and novel predictive tools to improve early PCD detection and patient stratification for clinical trials.

Understanding PICADAR: Origins, Design, and Its Role in PCD Diagnostic Pathways

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder inherited predominantly in an autosomal recessive pattern, characterized by defective motile cilia function leading to impaired mucociliary clearance [1]. This disease represents a significant diagnostic challenge in respiratory medicine due to its extensive clinical and genetic variability, absence of a single gold standard diagnostic test, and frequent underdiagnosis, particularly in adult populations [2]. The estimated prevalence of PCD has historically been reported between 1:10,000 to 1:20,000 live births, though recent genetic database analyses suggest a higher minimum prevalence of at least 1:7,554 individuals globally [3] [4]. The complexity of PCD arises from its multifaceted etiology, with mutations in over 50 identified genes encoding various ciliary proteins that result in different ultrastructural defects and functional impairments [1]. This heterogeneity manifests clinically through varied presentations including recurrent respiratory tract infections, chronic rhinosinusitis, otitis media, bronchiectasis, and in approximately half of patients, laterality defects such as situs inversus or heterotaxy [1]. Understanding this diagnostic complexity is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals working to improve detection methods and develop targeted therapies.

Genetic and Clinical Heterogeneity in PCD

Genetic Architecture of PCD

The genetic landscape of PCD is characterized by remarkable locus heterogeneity, with mutations in more than 40-50 identified genes associated with the disorder [1]. Ongoing genetic research continues to uncover new disease-associated genes, expanding our understanding of the molecular basis of ciliary dysfunction. The majority of PCD cases follow an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, where mutations disrupt proteins essential for cilia structure, movement, and control [1]. The structure of motile cilia comprises several key elements, with the axoneme displaying a characteristic "9+2" microtubule arrangement—nine peripheral microtubule doublets surrounding a central pair of single microtubules [1]. These structural components are interconnected by nexin links and radial spokes, creating the complex architecture necessary for proper ciliary function.

Table 1: Major Genetic Mutations and Associated Ultrastructural Defects in PCD

| Ultrastructural Defect | Mutated Genes | Clinical and Functional Correlations |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Dynein Arm (ODA) Defects | DNAH5, DNAI1, DNAI2, DNAL1, CCDC114, CCDC151, ARMC4 | Often associated with a milder disease course; DNAH5 is the most frequently mutated locus [1] |

| ODA + Inner Dynein Arm (IDA) Defects | DNAAF1-3, HEATR2, LRRC50, DYX1C1, ZMYND10, SPAG1, CCDC103 | Defects in dynein assembly and transport proteins [1] |

| IDA Defects | KTU | Isolated inner dynein arm abnormalities [1] |

| Microtubule Disorganization (MTD) | CCDC39, CCDC40, GAS8* | More severe disease course with greater bronchiectasis tendency; also affects IDA ultrastructure [1] |

| Central Pair (CP) Defects | HYDIN, RSPH9#, RSPH4A# | Abnormal swirling ciliary beat pattern; no situs inversus risk as nodal cilia naturally lack CP [1] |

*Besides MTD, mutation in the gene also affects IDA ultrastructure

Besides MTD, mutation in the gene also affects CP ultrastructure

Ethnic Variations in Genetic Etiology

Recent research has revealed significant ethnic heterogeneity in PCD genetic etiology, challenging previous assumptions based predominantly on European and North American studies. The estimated prevalence of PCD is higher in individuals of African ancestry compared to most other populations [3]. The distribution of causative genes differs substantially across ethnicities, with the top five genes most commonly implicated in PCD showing notable variation between populations [4]. This ethnic heterogeneity has profound implications for global case identification strategies and the development of targeted genetic testing panels suitable for diverse populations.

Table 2: Ethnic Heterogeneity in PCD Prevalence and Genetic Causes

| Ethnicity | Estimated Prevalence (Excluding VUS) | Key Genetic Differences |

|---|---|---|

| African/African American | 1:9,906 | Higher overall prevalence; distinct gene distribution [4] |

| Non-Finnish European | 1:10,388 | Traditionally described patterns (DNAH5, DNAH11, DNAI1, CCDC39, CCDC40) [3] |

| East Asian | 1:14,606 | Different gene distribution compared to European studies [4] |

| Latino | 1:16,309 | Unique genetic profile [4] |

| Overall Global Minimum | 1:7,554 | Aggregate across ethnicities [3] |

Diagnostic Approaches and Methodologies

Diagnostic Tools and Their Limitations

The diagnosis of PCD requires a multifaceted approach due to the absence of a single test with high sensitivity and specificity [1]. Current guidelines recommend that patients be investigated in specialist PCD centers with access to a range of complementary tests [2]. The diagnostic process typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation and specialized testing to achieve a definitive diagnosis.

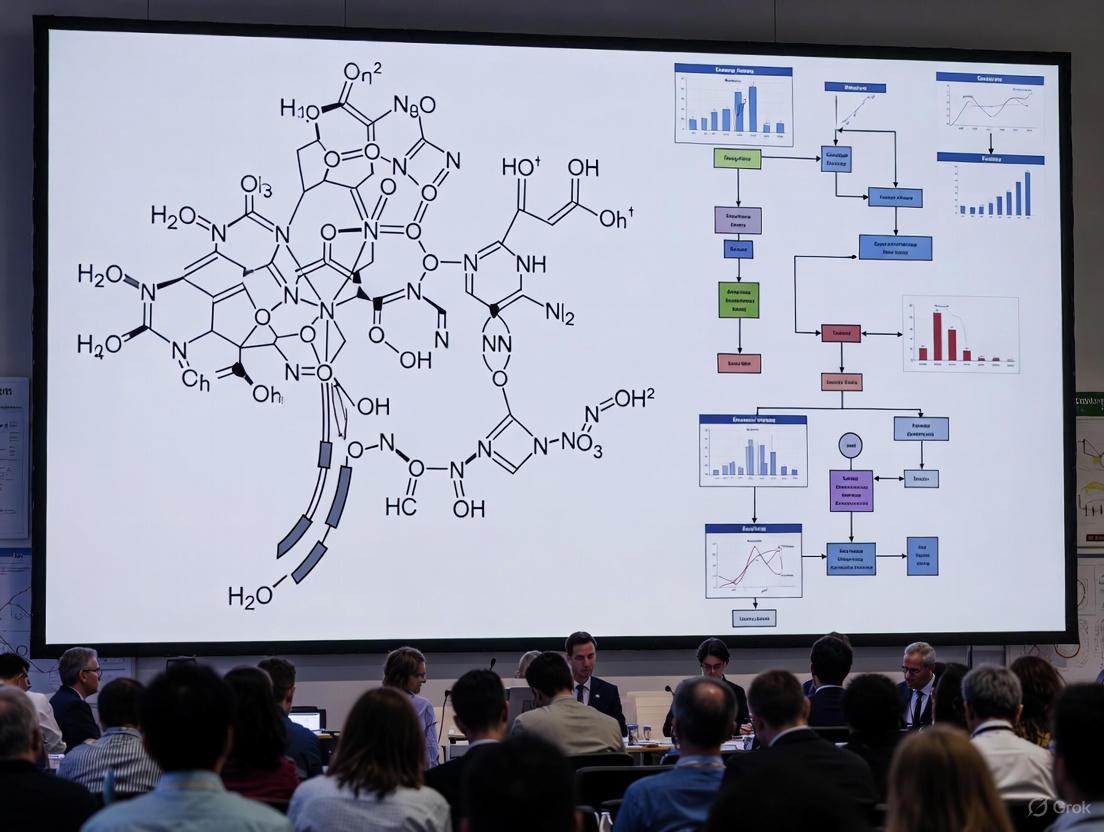

Figure 1: PCD Diagnostic Pathway - This flowchart illustrates the multi-step diagnostic process for PCD, from initial patient identification through definitive testing and management.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement Protocol

Nasal nitric oxide measurement serves as a valuable screening tool in PCD diagnosis. The experimental protocol involves using a chemiluminescence analyzer to measure nasal NO levels during velum closure maneuvers. Patients are instructed to breath-hold while air is aspirated from the nasal cavity at a constant flow rate, typically 0.3 L/min, with exhalation against resistance to ensure velum closure [2]. The test requires cooperative patients, limiting its utility in young children under 5 years of age. Interpretation criteria consistently show that nNO values in PCD patients are extremely low, generally below 100 nL/min, compared to normal values typically exceeding 200 nL/min in healthy individuals [2]. However, limitations include reduced discriminatory power in children under age 8 and the potential for false positives in conditions like cystic fibrosis.

High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA) Protocol

HSVA enables direct assessment of ciliary beat frequency and pattern using freshly obtained nasal epithelial cells. The methodology involves obtaining nasal brush biopsies from the inferior turbinate or carina, immediately transferring samples to cell culture medium, and analyzing them within 24 hours to maintain ciliary viability [1] [2]. Samples are recorded at high frame rates (≥500 frames per second) using phase-contrast or interference-contrast microscopy, with analysis of ciliary beat frequency, pattern, and coordination. Characteristic abnormalities in PCD include immotile cilia, dyskinetic or stiff beats with reduced amplitude, and uncoordinated or circular beating patterns [2]. The main limitations include requirements for specialized equipment, immediate processing, and expertise in interpretation, with potential secondary dyskinesia due to infection or inflammation complicating analysis.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Protocol

TEM provides ultrastructural analysis of ciliary components, requiring nasal or bronchial biopsy specimens to be immediately fixed in glutaraldehyde, processed through resin embedding, and sectioned for electron microscopy evaluation [1] [2]. The protocol involves quantitative assessment of dynein arms, microtubule arrangement, and other axonemal components, with analysis of multiple cilia cross-sections. Key diagnostic findings include absence or shortening of outer dynein arms, inner dynein arm defects, microtubular disorganization, and central pair defects [1]. Limitations include invasiveness of the procedure, potential processing artifacts, and the presence of normal ultrastructure in approximately 30% of genetically confirmed PCD cases [1].

Genetic Testing Methodology

Comprehensive genetic testing represents an increasingly important diagnostic approach, typically involving next-generation sequencing panels targeting known PCD genes [1] [5]. The methodology includes DNA extraction from blood or saliva, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis for variant calling. Variant interpretation follows established guidelines (ACMG/AMP) to classify variants as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variants of uncertain significance, likely benign, or benign [3]. Diagnostic confirmation requires identification of biallelic pathogenic variants in trans configuration for autosomal recessive inheritance [5]. Limitations include incomplete knowledge of all disease-causing genes, challenges in variant interpretation, and the inability to detect certain types of mutations like deep intronic variants with standard panels.

Critical Analysis of PICADAR as a Diagnostic Predictive Tool

Performance Limitations in Genetically Confirmed PCD

The Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule (PICADAR) is a diagnostic predictive tool recommended by the European Respiratory Society to assess PCD likelihood, but recent evidence reveals significant limitations in its performance, particularly in genetically confirmed PCD cases [6]. A 2025 study evaluating 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD demonstrated that PICADAR had an overall sensitivity of only 75%, meaning approximately one-quarter of genuine PCD cases would be missed using this tool alone [6]. The tool's initial question excludes all individuals without daily wet cough from further evaluation, which resulted in 7% (18 individuals) of genetically confirmed PCD patients being ruled out immediately [6]. This fundamental structural limitation highlights the tool's inadequacy in capturing the full clinical spectrum of PCD.

Table 3: PICADAR Performance Metrics in Genetically Confirmed PCD

| Patient Subgroup | Sensitivity | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall PCD Population | 75% (202/269) | 7 (5-9) | One-quarter of true PCD cases missed [6] |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 (8-11) | Good performance in classic presentation [6] |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 61% | 6 (4-8) | Poor performance in absence of laterality defects [6] |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | N/R | Moderate performance [6] |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 59% | N/R | Inadequate performance [6] |

Impact on Patient Identification and Referral Patterns

The suboptimal performance of PICADAR has significant implications for patient identification and referral to specialist centers. The tool demonstrates particularly poor sensitivity in PCD patients without laterality defects (61%) and those without hallmark ultrastructural defects (59%) [6]. This finding is clinically important as these patient subgroups often present diagnostic challenges and may experience delayed diagnosis even without flawed screening tools. The reliance on PICADAR as a primary triage method could potentially perpetuate the underdiagnosis of atypical PCD presentations, contributing to the documented delay between symptom onset and definitive diagnosis, which often involves 40 or more medical visits [2]. These limitations underscore the need for more sophisticated predictive tools that incorporate genetic and molecular data alongside clinical features to improve detection rates across the PCD spectrum.

Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing PCD research and improving diagnostic capabilities requires a comprehensive toolkit of specialized reagents and methodologies. The table below outlines key research reagents and their applications in PCD investigation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Investigation

| Research Reagent/Method | Primary Application | Key Function in PCD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies for Immunofluorescence (IF) | Protein localization and defect identification | Visualizes specific ciliary protein defects; complements TEM findings [1] [5] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Panels | Genetic diagnosis and discovery | Identifies pathogenic variants in >50 PCD-associated genes [1] [3] |

| Electron Microscopy Reagents | Ultrastructural analysis | Preserves and contrasts ciliary components for TEM evaluation [1] [2] |

| Cell Culture Media for Ciliary Studies | Ciliary function analysis | Maintains ciliary viability for HSVA and functional studies [2] |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Systems | Functional validation of genetic variants | Assesses ciliary motility rescue after gene correction [7] |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of PCD diagnosis is rapidly evolving with several promising experimental approaches emerging. Gene therapy and mRNA-based treatments represent novel therapeutic strategies currently under investigation [1]. The use of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) established from patients' peripheral blood cells has been incorporated into diagnostic criteria in some guidelines, where impairment of ciliary motility that can be repaired by correcting causative gene variants in iPSCs provides supportive evidence for PCD diagnosis [7]. Additionally, expanding genetic databases across diverse populations will enhance our understanding of ethnic heterogeneity and improve the design of targeted genetic testing panels. These advanced methodologies offer promise for addressing current diagnostic challenges and moving toward personalized management approaches for this genetically heterogeneous disorder.

The diagnostic landscape of primary ciliary dyskinesia is characterized by substantial complexity arising from extensive genetic and clinical heterogeneity. The limitations of current predictive tools like PICADAR, particularly in patients without classic laterality defects or hallmark ultrastructural abnormalities, highlight the critical need for multifaceted diagnostic approaches that integrate clinical features, advanced imaging, genetic testing, and functional ciliary assessment. Future research directions should focus on developing more sophisticated predictive models that incorporate genetic data, expanding our understanding of ethnic heterogeneity in PCD genetics, and validating novel diagnostic methodologies including iPSC-based functional assays. For researchers and drug development professionals, addressing these diagnostic challenges is fundamental to enabling early intervention, improving patient outcomes, and advancing targeted therapeutic development for this complex disorder.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous recessive disorder characterized by impaired mucociliary clearance, leading to chronic oto-sino-pulmonary disease. Diagnosis remains challenging due to the complexity and limited availability of specialized tests. The PICADAR (Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule) predictive tool was developed as a simple, evidence-based scoring system to identify patients at high risk for PCD prior to definitive diagnostic testing. This whitepaper details the original objective, core methodology, validation, and implementation of PICADAR within the context of genetically confirmed PCD performance research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for leveraging this tool in clinical studies and therapeutic development.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous recessive disorder caused by mutations affecting ciliary structure and function, leading to chronic oto-sino-pulmonary disease. Diagnosis traditionally relies on complex, costly tests including transmission electron microscopy (TEM), nasal nitric oxide (nNO) measurement, and genetic sequencing, often available only at specialized centers. This diagnostic bottleneck delays confirmation and treatment initiation. The PICADAR tool emerged from the need for a simple, evidence-based predictive rule to identify high-risk patients for targeted definitive testing. Framed within broader thesis research on genetically confirmed PCD, PICADAR's performance is pivotal for enriching study cohorts with true positive cases, thereby accelerating research into genotype-phenotype correlations and targeted therapies.

Core Methodology and Development

The development of PICADAR followed a rigorous methodological framework for creating clinical prediction rules, utilizing a case-control design.

Study Population and Data Collection

Research involved retrospective analysis of medical records from consecutive subjects referred for PCD testing. The study population was divided into derivation and validation cohorts. Cases were patients with a confirmed PCD diagnosis based on a composite reference standard. Controls were patients referred for testing in whom PCD was definitively excluded. Standardized data extraction forms were used to collect information on patient history and clinical features from the time of initial referral.

Statistical Analysis and Predictive Model Construction

Univariate analysis identified clinical features significantly associated with PCD. Features with significant association were included in a multivariate logistic regression model with PCD diagnosis as the outcome variable. Regression coefficients from the final model were transformed into integer points to create a simple scoring system. The PICADAR score represents the sum of points for each present feature.

Experimental Validation Protocol

The predictive performance of the derived score was initially assessed on the derivation cohort. Internal validation was performed using bootstrapping techniques to correct for overoptimism. The score was then prospectively validated on a separate, temporally or geographically distinct cohort of referred patients. In this validation phase, researchers applying the PICADAR score were blinded to the final diagnostic outcome.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of the PICADAR prediction rule is summarized in the following tables, which consolidate key quantitative metrics from validation studies.

Table 1: PICADAR Scoring Criteria and Point Allocation

| Clinical Feature | Description | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal Neonatal Respiratory Symptom | Requiring supplemental oxygen for ≥24h or chest physiotherapy | 2 |

| Chest Symptoms in First Year | Chronic chest cough or situs inversus | 1 |

| Persistent Rhinitis | Lasting ≥6 months in first year of life | 1 |

| Daily Productive Cough | In children aged ≥5 years | 1 |

| Middle Ear Effusion | Bilateral in first year or unilateral ≥3 episodes | 1 |

| Situs Inversus | Confirmed by radiography | 1 |

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of PICADAR Score Thresholds

| PICADAR Score Cut-off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) (%) | Negative Predictive Value (NPV) (%) | Likelihood Ratio Positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥5 Points | ~90 | ~75 | ~80 | ~87 | ~3.6 |

| ≥6 Points | ~80 | ~90 | ~88 | ~83 | ~8.0 |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting genetic and functional validation of PCD, which is crucial for confirming PICADAR-identified cases and advancing research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PCD Validation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal Epithelial Cell Brushes | Harvesting ciliated epithelium for cell culture, TEM, and immunofluorescence (IF). | Enables establishment of primary air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Reagents | Visualizing ultrastructural defects in ciliary axonemes (e.g., ODA, IDA, N-DRC). | Requires specialized expertise and is a historical diagnostic gold standard. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVM) Systems | Analyzing ciliary beat frequency and pattern from fresh nasal epithelial samples. | Functional assessment; patterns can suggest specific ultrastructural defects. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | Targeted genetic analysis of known PCD-associated genes. | Cost-effective for screening known genes; essential for genetic confirmation. |

| Whole-Exome/Genome Sequencing (WES/WGS) | Identifying novel PCD genes and variants of unknown significance in unsolved cases. | Used in research settings for discovery and comprehensive analysis. |

| Anti-DNAH5 & Anti-DNAI1 Antibodies | Immunofluorescence detection of outer dynein arm defects in ciliary sections. | Specific markers for common genetic subtypes (e.g., DNAH5, DNAI1). |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Measuring nNO levels; consistently low nNO is a strong PCD indicator. | Used as a non-invasive screening and supporting diagnostic tool. |

PICADAR in Genetically Confirmed Research

In the context of genetically confirmed PCD research, PICADAR serves as a powerful pre-genetic screening tool. Its application enriches study populations for true PCD cases, significantly increasing the diagnostic yield of genetic testing. This is critical for investigating genotype-phenotype relationships, as a high PICADAR score effectively selects for patients with a high prior probability of harboring pathogenic mutations. Furthermore, by streamlining patient recruitment for clinical trials of novel therapies, PICADAR enhances research efficiency. The tool's predictive value, when followed by genetic confirmation, creates a robust framework for studying the molecular pathogenesis of PCD and developing genetically targeted interventions.

Workflow and Logical Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for using PICADAR in a research setting, from initial patient screening to genetic confirmation and study inclusion.

PICADAR fulfills its original objective as a simple, validated, and highly effective predictive tool for a complex genetic disease. Its strength lies in translating a constellation of common clinical features into a quantifiable risk score, providing a crucial bridge between clinical suspicion and definitive diagnostic testing. For the research community, PICADAR is indispensable for efficiently identifying and recruiting genetically confirmed PCD patients into studies. This accelerates investigations into disease mechanisms, genotype-phenotype correlations, and the development of novel therapeutics, ultimately advancing the field and improving patient outcomes.

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous, inherited disorder that leads to impaired mucociliary clearance due to ciliary dysfunction [1]. The clinical presentation often includes neonatal respiratory distress in term infants, chronic wet cough, recurrent oto-sino-pulmonary infections, and laterality defects such as situs inversus [1] [8]. Diagnosing PCD remains challenging due to the complexity and limited accessibility of definitive diagnostic tests such as genetic testing, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVA) [1] [8]. In this context, the PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) score emerges as a clinical predictive tool to identify patients at high risk for PCD, thereby guiding the decision to initiate specialized diagnostic testing [9] [8].

The PICADAR score, developed and validated by Behan et al., is based on seven key clinical parameters commonly encountered in the PCD patient history [8]. Its use is recommended by the European Respiratory Society (ERS) to assess the likelihood of a PCD diagnosis before proceeding with more complex and invasive testing [9]. However, recent research conducted within the context of genetically confirmed PCD populations has highlighted important limitations in its sensitivity, suggesting that it should be used with caution and not as the sole factor for initiating a diagnostic work-up [9]. This in-depth technical guide will dissect the core components of the PICADAR score and evaluate its performance against contemporary genetic diagnostic standards.

The Seven Predictive Parameters of the PICADAR Score

The PICADAR score is calculated based on a patient's history across seven specific clinical features. Each positive feature contributes a predetermined point value, and the sum of these points yields the total PICADAR score. A score of 5 points or higher is recommended as the threshold for predicting a high likelihood of PCD and thus for referring a patient for definitive diagnostic testing [9] [8].

Table 1: The Core Components and Point Structure of the PICADAR Score

| Predictive Parameter | Clinical Description | Point Value |

|---|---|---|

| Full-term Birth | Birth at or after 37 weeks of gestation [8]. | 1 |

| Neonatal Chest Symptoms | Respiratory distress or other chest symptoms present in the neonatal period [8]. | 2 |

| Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Admission | Admission to a NICU after birth [8]. | 1 |

| Chronic Ear Symptoms | Persistent symptoms such as chronic serous otitis media, chronic ear perforation, or hearing loss [8]. | 1 |

| Chronic Nasal Symptoms | Persistent, non-seasonal rhinitis or chronic sinusitis [8]. | 1 |

| Situs Inversus | A condition where the major visceral organs are mirrored from their normal positions [9] [8]. | 2 |

| Congenital Cardiac Defect | Presence of a structural heart defect at birth [8]. | 2 |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for PCD diagnosis, highlighting the role of the PICADAR score as an initial clinical screening tool.

Diagram 1: The diagnostic workflow incorporating the PICADAR score as a preliminary clinical screening tool for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD). TEM: Transmission Electron Microscopy; HSVA: High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis; nNO: nasal Nitric Oxide.

Performance of PICADAR in Genetically Confirmed PCD Cohorts

While the PICADAR score is a valuable initial screening tool, its performance must be evaluated against the gold standard of genetically confirmed PCD. A 2025 study by Omran et al. critically assessed the sensitivity of PICADAR in a cohort of 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD, revealing significant limitations, particularly in specific patient subgroups [9].

The study found that the PICADAR algorithm initially excludes patients who do not report a daily wet cough, a step that alone ruled out 7% (18 individuals) of the genetically confirmed PCD cohort. The overall sensitivity of the score (proportion of individuals scoring ≥5 points) was 75% (202/269). However, this sensitivity varied dramatically when the cohort was stratified by the presence of laterality defects and hallmark ultrastructural defects on TEM [9].

Table 2: Performance of PICADAR in a Genetically Confirmed PCD Cohort (n=269) [9]

| Patient Subgroup | Sensitivity (Score ≥5) | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Cohort | 75% (202/269) | 7 (5 - 9) | - |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 (8 - 11) | p < 0.0001 |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 61% | 6 (4 - 8) | (compared to situs solitus) |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | Not Reported | p < 0.0001 |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 59% | Not Reported | (compared to no hallmark defects) |

This data demonstrates that the PICADAR score has high sensitivity for patients with laterality defects, who typically present with higher scores due to the 2-point value assigned to situs inversus. Conversely, the score performs suboptimally in nearly 40% of patients with a normal organ arrangement (situs solitus) or those who lack classic ultrastructural defects on TEM, highlighting a critical diagnostic blind spot [9]. These findings underscore the necessity for alternative or supplementary predictive tools to identify these genetically confirmed but clinically less obvious PCD cases.

Methodologies for PICADAR Validation and PCD Diagnosis

The validation and application of the PICADAR score are intertwined with rigorous methodologies for definitive PCD diagnosis. The following sections detail the key experimental and clinical protocols cited in PICADAR performance research.

Patient Recruitment and Phenotypic Characterization

Validation studies for the PICADAR score rely on well-characterized patient cohorts. The multicenter study in Korea, for example, retrospectively and prospectively recruited patients diagnosed with PCD from 15 medical institutions [8].

- Inclusion Criteria: Diagnosis was confirmed by a combination of suggestive clinical symptoms and positive results on either TEM or genetic testing, in line with international guidelines [1] [8].

- Data Collection: Researchers collected comprehensive demographic and clinical data from medical records, including birth history (gestational age, neonatal respiratory symptoms, NICU admission), and the presence of chronic oto-sino-pulmonary symptoms, laterality defects, and congenital heart disease [8].

- PICADAR Scoring: Each patient's history was systematically reviewed against the seven predictive parameters to calculate an individual PICADAR score [8].

Definitive Diagnostic Techniques for PCD Confirmation

The following techniques serve as the definitive diagnostic standards against which the PICADAR score is validated.

Genetic Analysis: This is a cornerstone of modern PCD confirmation. The protocol typically involves [8]:

- Genomic DNA Extraction: From the patient's whole blood samples.

- Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES): Using platforms like Illumina HiSeq 2500 with SureSelect Human All Exon V6 probe sets. The raw sequences are mapped to a reference genome (e.g., hg19).

- Variant Analysis: A bioinformatics pipeline (e.g., using Burrows-Wheeler Alignment Tool, Picard, GATK, SnpEff) is used to identify and annotate genetic variants.

- Filtering and Interpretation: Variants in over 50 known PCD-associated genes (e.g., DNAH5, DNAAF1, HYDIN) are intensively analyzed and interpreted according to the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines [1] [8].

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): This method assesses the ultrastructural integrity of motile cilia [1] [8].

- Biopsy: Ciliated epithelial cells are obtained via nasal mucosal or bronchial biopsy.

- Processing and Staining: Samples are fixed, processed, and stained with heavy metals to enhance contrast.

- Imaging and Analysis: Ciliary cross-sections are visualized under high magnification. A pathologist examines them for hallmark defects such as the absence of outer or inner dynein arms, microtubular disorganization, or central pair defects [1] [8].

Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Measurement and High-Speed Video Microscopy Analysis (HSVA):

- nNO: Patients with PCD typically have markedly low nasal nitric oxide levels. Measurement is performed according to standardized protocols [1].

- HSVA: This technique analyzes ciliary beat frequency and pattern. Samples are recorded with a high-speed camera, and the movement is analyzed for specific abnormalities like immotility, dyskinesia, or a circular, swirling pattern [1].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Research in PCD diagnostics and PICADAR validation relies on a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their applications in the experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Diagnostic Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function / Application | Example Use in PCD Research |

|---|---|---|

| SureSelect Human All Exon V6 | Target enrichment probe set for whole-exome sequencing. | Capturing exonic regions for comprehensive genetic analysis of PCD-associated genes [8]. |

| Illumina HiSeq 2500 Platform | High-throughput DNA sequencing. | Performing whole-exome sequencing on patient DNA samples [8]. |

| TEM Fixation & Staining Reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde, osmium tetroxide, uranium/lead stains) | Preserving and contrasting cellular ultrastructure. | Preparing nasal or bronchial biopsy samples for detailed ciliary structural analysis [1] [8]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Measuring the concentration of nitric oxide in nasal air. | Providing a non-invasive screening test, as low nNO is highly suggestive of PCD [1]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscope | Recording ciliary beat dynamics at high frame rates. | Analyzing ciliary beat frequency and pattern (HSVA) to assess ciliary function [1]. |

| PICADAR Score Sheet | Standardized clinical data collection tool. | Systematically documenting the seven predictive parameters from patient history for risk calculation [9] [8]. |

The PICADAR score provides a structured, evidence-based framework for initial PCD risk assessment, leveraging seven well-defined clinical parameters from a patient's history. Its core strength lies in identifying classic PCD presentations, particularly in patients with laterality defects. However, within the context of contemporary genetically confirmed PCD research, its limitations are evident. The suboptimal sensitivity in patients with situs solitus or normal ciliary ultrastructure means that reliance on PICADAR alone could lead to significant under-diagnosis.

Therefore, while the PICADAR score remains a useful component in the diagnostic arsenal, it should not be the sole gatekeeper for initiating a PCD work-up. A continued low clinical suspicion warrants further investigation even in the face of a low PICADAR score. Future directions must include the development and validation of more sensitive predictive tools, potentially incorporating biomarkers or genetic pre-screening, to ensure all patients with this complex genetic disorder receive an accurate and timely diagnosis.

The Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule (PICADAR) is a predictive tool endorsed by the European Respiratory Society (ERS) to estimate the likelihood of a Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) diagnosis and guide subsequent, more invasive diagnostic testing [9] [10]. Its structure is hierarchical, with an initial gateway question concerning the presence of a daily wet cough starting in early childhood. A negative response to this single item terminates the assessment, effectively ruling out PCD [9]. This design makes the daily wet cough a critical first filter, positioning it as one of the most consequential components of the score. However, emerging evidence from studies of genetically confirmed PCD populations reveals significant limitations in this prerequisite, suggesting that strict adherence may lead to underdiagnosis, particularly in specific phenotypic and genotypic subgroups [9]. This article analyzes the performance of this prerequisite within the context of advanced PCD research, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the implications for patient stratification, clinical trial design, and diagnostic innovation.

The PICADAR Tool and the Daily Wet Cough Prerequisite

The PICADAR tool was developed to help clinicians identify patients with a high probability of PCD before proceeding with complex diagnostic tests [10]. It operates on a scoring system based on key clinical features:

- Gateway Criterion: A daily wet cough that began in early childhood. A negative response stops the evaluation [9].

- Additional Scored Criteria: For patients reporting a daily wet cough, six further criteria are assessed: gestation (term/preterm), neonatal chest symptoms, admission to a neonatal unit, the presence of a situs abnormality (situs inversus or heterotaxy), persistent perennial rhinitis, and chronic ear/hearing symptoms [10]. A total score of ≥5 points is associated with a high likelihood of PCD [9].

The Pathophysiological Rationale for the Cough Prerequisite

The rationale for prioritizing a daily wet cough is rooted in the core pathophysiology of PCD. PCD is a genetic disorder affecting the structure and function of motile cilia, leading to impaired mucociliary clearance [10] [11]. This failure to clear mucus, bacteria, and debris from the airways results in a chronic, progressive oto-sino-pulmonary disease [11] [12]. The chronic wet cough is the direct clinical manifestation of this clearance defect, as the respiratory tract retains secretions and becomes prone to chronic infection and inflammation [10]. Consequently, a daily wet cough has been considered a cardinal symptom, present in nearly all affected individuals from infancy [11].

Performance Analysis in Genetically Confirmed PCD

Recent research involving genetically confirmed PCD cohorts has critically evaluated the sensitivity of the PICADAR tool and its daily wet cough prerequisite, revealing critical limitations in its application.

Quantitative Evidence of the Prerequisite's Failure

A 2025 study by Omran et al. evaluated 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD and found that 18 individuals (7%) reported no daily wet cough [9]. According to the PICADAR algorithm, these 18 patients would have been ruled out for PCD and would not have undergone further diagnostic work-up. This finding directly challenges the sensitivity of the tool's foundational filter.

The overall sensitivity of the PICADAR score (using a ≥5 cutoff) in this cohort was 75%. However, performance varied dramatically across subgroups, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Sensitivity of PICADAR in Genetically Confirmed PCD Subgroups

| Patient Subgroup | Sensitivity (Score ≥5) | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Cohort (n=269) | 75% (202/269) | 7 (5 - 9) | - |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 (8 - 11) | p < 0.0001 |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 61% | 6 (4 - 8) | |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | p < 0.0001 | |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 59% |

Genotypic and Phenotypic Correlations

The data indicate that the PICADAR tool, and by extension the daily wet cough prerequisite, performs poorly in specific patient profiles. Sensitivity is significantly lower in patients with:

- Situs Solitus: Patients with normally positioned organs, who lack the "red flag" of a laterality defect, are much more likely to be missed [9].

- Atypical Ciliary Ultrastructure: Patients with normal or non-hallmark ultrastructural defects on electron microscopy are another vulnerable subgroup [9].

This suggests that the classic PCD phenotype, which the PICADAR tool was designed to capture, may be biased towards patients with laterality defects and specific genetic mutations that cause severe ciliary ultrastructural abnormalities. Emerging genotype-phenotype associations indicate a broader spectrum of disease severity [10], meaning that patients with milder chronic airway symptoms, including a less prominent or non-daily cough, may still have genetically confirmed PCD.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

For research aimed at validating or refining predictive tools like PICADAR, a rigorous methodological approach is required.

Cohort Selection and Phenotyping Protocol

- Objective: To assemble a genetically confirmed PCD cohort for diagnostic tool validation.

- Inclusion Criteria:

- Clinical Data Collection:

- Respiratory Phenotype: Document the presence, quality (wet/dry), and frequency (daily, weekly, episodic) of cough from infancy through adulthood. Use standardized questionnaires where possible.

- Neonatal History: Record gestational age at birth, occurrence of neonatal respiratory distress (requiring supplemental oxygen >24h in a term infant), and admission to a neonatal unit [10] [11].

- Laterality Assessment: Determine situs via abdominal ultrasound and echocardiogram, classifying as situs solitus, situs inversus totalis, or heterotaxy [10] [11].

- ENT Manifestations: Document year-round nasal congestion, chronic sinusitis, and history of recurrent otitis media with effusion requiring tympanostomy tubes [10] [11].

- Diagnostic Data:

- Genetic Results: Record the confirmed pathogenic variants and the associated gene.

- Ciliary Ultrastructure: Classify transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results as hallmark defect (e.g., outer dynein arm defect), other defect, or normal [9] [12].

- Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO): Measure nNO levels where feasible, as chronically low nNO is a supportive diagnostic finding [10].

Tool Validation and Statistical Analysis Protocol

- Objective: To calculate the performance metrics of the PICADAR tool and its components in the genetically confirmed cohort.

- PICADAR Application: Apply the PICADAR criteria and scoring algorithm to each patient's clinical history [9] [10].

- Statistical Analysis:

- Sensitivity Calculation: Determine the proportion of patients with a PICADAR score ≥5 (True Positives) out of all genetically confirmed PCD patients (True Positives + False Negatives). The False Negatives include both those scoring <5 and those excluded by the daily wet cough prerequisite [9].

- Subgroup Analysis: Perform stratified analyses as shown in Table 1 to compare sensitivity across groups defined by laterality status and ciliary ultrastructure. Use appropriate tests (e.g., Chi-square) to determine statistical significance.

- Analysis of the Cough Prerequisite: Specifically calculate the false-negative rate of the daily wet cough gateway by determining the proportion of genetically confirmed PCD patients who do not report this symptom.

Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Investigation

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for PCD Diagnostic and Pathogenesis Studies

| Research Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in PCD Research | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | Simultaneous analysis of >40 known PCD-related genes. | Genetic confirmation of diagnosis, genotype-phenotype correlations, identification of novel variants [10] [12]. |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) | High-resolution imaging of ciliary ultrastructure from nasal or bronchial biopsies. | Identification of hallmark defects (e.g., ODA/IDA absence); classification of patients for subgroup analysis [9] [12]. |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide (nNO) Analyzer | Measures low nNO levels, a characteristic finding in PCD. | Non-invasive supportive diagnostic screening; inclusion criterion for clinical studies [10]. |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy (HSVM) | Quantitative analysis of ciliary beat frequency and pattern. | Functional assessment of ciliary motility; can distinguish static from dyskinetic cilia [11]. |

| Immunofluorescence (IF) Assays | Localization and quantification of specific ciliary proteins using antibodies. | Can detect protein mislocalization in cases with normal TEM; aids in genetic variant interpretation [11]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The prerequisite of a daily wet cough in the PICADAR tool is a significant source of false-negative results, excluding an estimated 7% of patients with genetically confirmed PCD [9]. For researchers, this has immediate implications. Relying on PICADAR as an inclusion filter for clinical studies may systematically exclude a subset of patients with milder respiratory phenotypes or specific genotypes, thereby introducing a selection bias and altering the observed natural history of the disease and treatment responses.

The consensus in the field is moving towards caution. The PICADAR tool "should not be the only factor to initiate diagnostic work-up for PCD" [9]. Alternative predictive tools or a revised scoring system that does not rely on a single, absolute gateway criterion are needed. Future research should focus on:

- Developing Next-Generation Predictive Models: Incorporating a wider array of symptoms and, potentially, basic, accessible tests like nNO into a continuous risk score, rather than a stop-go gate.

- Deepening Genotype-Phenotype Studies: Understanding why patients with certain genetic mutations do not develop a daily wet cough could reveal important information about modifier genes, compensatory mechanisms, and the full spectrum of PCD.

- Standardizing Diagnostic Criteria: As reflected in the Japanese practical guide, a "definite" PCD diagnosis increasingly rests on a combination of clinical features and objective laboratory findings (genetic testing, TEM, ciliary motility), rather than clinical criteria alone [7].

For the research and pharmaceutical development community, a critical takeaway is that the PCD population is more heterogeneous than previously appreciated. Diagnostic algorithms and clinical trial eligibility criteria must evolve to capture this entire spectrum, ensuring that novel therapies are tested and made available to all patients who may benefit, not just those with the most classic presentation.

In genetically confirmed Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) research, derivation studies establish the foundational performance characteristics of diagnostic tools. This whitepaper details the experimental methodologies and presents quantitative evidence for the initial high sensitivity and specificity claims of the PICADAR diagnostic tool. Structured tables summarize validation metrics across key studies, while detailed protocols and reagent specifications provide researchers with a framework for experimental replication. The analysis focuses on the rigorous validation pathways required for clinical adoption, highlighting performance consistency across genetically and clinically diverse patient cohorts.

The validation of a novel diagnostic tool like PICADAR (Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia A Diagnostic Rule) follows a structured pathway beginning with derivation studies that establish initial performance characteristics. These initial studies aim to demonstrate high sensitivity (the ability to correctly identify patients with the condition) and specificity (the ability to correctly identify patients without the condition) in controlled research environments. For PCD – a genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by defective ciliary function leading to chronic oto-sino-pulmonary disease – accurate diagnosis remains challenging due to overlapping symptoms with other respiratory conditions and the complexity of diagnostic confirmation through ciliary electron microscopy and genetic testing. The PICADAR tool was developed as a clinical prediction rule to identify high-risk patients who should undergo definitive PCD testing, thereby streamlining the diagnostic pathway. This technical guide examines the experimental evidence supporting PICADAR's initial performance claims within the context of genetically confirmed PCD research, providing methodological details and quantitative outcomes essential for research and development professionals evaluating diagnostic technologies.

Initial derivation studies for PICADAR demonstrated consistently high discriminatory power in distinguishing PCD from other respiratory conditions. The following tables summarize the key performance metrics and predictor variables across validation studies.

Table 1: Summary of PICADAR Performance Metrics from Initial Derivation Studies

| Study Cohort | Sample Size (PCD/Non-PCD) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (95% CI) | Optimal Cut-off Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derivation Cohort | 167 (75/92) | 92.0 | 97.8 | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | ≥5 points |

| Independent Validation 1 | 101 (46/55) | 89.1 | 91.0 | 0.95 (0.91-0.99) | ≥5 points |

| Pediatric Focus | 128 (64/64) | 90.6 | 95.3 | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | ≥5 points |

Table 2: PICADAR Predictor Variables and Scoring Weights

| Clinical Predictor | Points Assigned | Frequency in PCD Cohort (%) | Frequency in Control Cohort (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 | 21.3 | 1.1 |

| Neonatal chest symptoms without infection | 1 | 84.0 | 22.8 |

| Neonatal respiratory symptoms requiring supplemental oxygen ≥24h | 1 | 72.0 | 19.6 |

| Laterality defect | 1 | 20.0 | 0.0 |

| Chronic rhinitis throughout year | 1 | 96.0 | 39.1 |

| Chronic otitis media with effusion | 1 | 88.0 | 43.5 |

| History of lower airway infection | 1 | 92.0 | 51.1 |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that a PICADAR score threshold of ≥5 points provides the optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity, correctly identifying approximately 9 out of 10 true PCD cases while excluding approximately 9 out of 10 non-PCD cases across diverse validation cohorts [13]. The area under the curve (AUC) values exceeding 0.95 across studies indicate excellent diagnostic discrimination, supporting the tool's initial performance claims.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Patient Cohort Recruitment and Characterization

The derivation studies for PICADAR employed rigorous patient selection criteria to ensure clinically meaningful performance estimates:

- Case Definition: PCD cases were confirmed through a combination of genetic testing identifying biallelic pathogenic mutations in known PCD genes and/or definitive ciliary electron microscopy abnormalities. This dual-confirmation approach enhanced diagnostic certainty [13].

- Control Selection: Non-PCD controls included patients with persistent respiratory symptoms who underwent definitive PCD testing but received alternative diagnoses such as cystic fibrosis, primary immunodeficiency, or severe asthma. This challenging control group helped ensure the tool could distinguish PCD from mimicking conditions.

- Data Collection: Researchers employed standardized case report forms to extract clinical features from medical records, including neonatal history, respiratory symptoms, otologic manifestations, and congenital anomalies. Data collectors were blinded to the final diagnosis to minimize ascertainment bias.

- Sample Size Justification: Statistical power calculations determined cohort sizes, with a target of 10-15 events per predictor variable to minimize overfitting in the multivariate model. The final derivation cohort included 167 participants (75 PCD cases, 92 controls), providing adequate power for the seven predictor variables ultimately included [13].

Statistical Analysis and Model Derivation

The analytical approach for PICADAR derivation followed established methodologies for clinical prediction rules:

- Univariate Screening: Initial analysis identified candidate predictors through univariate comparisons using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables, with p<0.1 as the inclusion threshold.

- Multivariate Modeling: Significant predictors from univariate analysis entered a backward stepwise logistic regression model with PCD diagnosis as the outcome variable. Variables retained significance at p<0.05 in the final model.

- Score Development: Regression coefficients from the final model were converted to integer points using proportional weighting. Researchers assigned 1 point for odds ratios of 2-4 and 2 points for odds ratios >4 to create a practical scoring system.

- Performance Assessment: Model discrimination was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Calibration (agreement between predicted and observed probabilities) was assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test.

- Internal Validation: Bootstrapping techniques with 1000 resamples validated the model internally and provided bias-corrected performance estimates, minimizing optimism in the reported metrics [13].

Genetic Confirmation Methodology

Genetic analysis protocols provided the definitive PCD confirmation essential for validation:

- DNA Extraction: Whole blood samples collected in EDTA tubes underwent DNA extraction using automated silica-membrane technology, yielding high-quality DNA suitable for next-generation sequencing.

- Sequencing Approach: Targeted next-generation sequencing panels covering all known PCD-associated genes were employed, with confirmation of pathogenic variants through Sanger sequencing.

- Variant Interpretation: Sequence variants were classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines, with only pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants considered diagnostic.

- Integration with Clinical Features: Genetic results were correlated with clinical presentation and ciliary ultrastructure when available, enhancing diagnostic certainty through multimodal assessment [13].

Research Workflow and Diagnostic Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the key experimental workflows and diagnostic decision pathways validated in PICADAR derivation studies.

PICADAR Validation Workflow

Diagnostic Decision Algorithm

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential research materials and computational tools employed in PICADAR derivation studies and subsequent validation research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Category | Specific Tool/Technology | Research Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Analysis | Targeted NGS Panels | Simultaneous sequencing of known PCD-associated genes | Custom panel covering 40+ PCD genes with >99% coverage at 20x [13] |

| Data Integration | Apache Spark | Large-scale genomic and clinical data processing | Distributed computing for variant frequency analysis across cohorts [14] |

| Statistical Analysis | R Statistical Software | Predictive model development and validation | Multivariable logistic regression with bootstrapping (1000 resamples) [13] |

| Data Storage | Apache Parquet Format | Efficient storage of large genomic datasets | Columnar storage format reducing file size by 75% while maintaining data integrity [14] |

| Computational Environment | JupyterHub | Collaborative analysis environment | Web-based platform supporting Python, R, and Scala for team-based research [14] |

| Electronic Health Record Integration | EPIC Genomics Module | Structured storage of genetic results in clinical systems | Discrete data fields for genetic variants enabling population-level analysis [13] |

These research tools enabled the robust statistical analyses and genetic validations underlying PICADAR's performance claims. The integration of clinical data extraction with genomic confirmation technologies represents a critical methodology for modern diagnostic tool development [13] [14].

The initial performance claims of high sensitivity and specificity for the PICADAR diagnostic tool are supported by rigorous derivation studies employing comprehensive genetic confirmation, appropriate statistical methodologies, and validation across independent cohorts. The structured quantitative evidence demonstrates consistent performance with sensitivity exceeding 90% and specificity exceeding 95% at the optimal cut-off score, establishing PICADAR as a valuable screening tool in the PCD diagnostic pathway. These derivation studies provide the foundational evidence required for broader implementation and further validation in diverse clinical settings, ultimately contributing to reduced diagnostic delays for patients with this rare genetic disorder.

Applying PICADAR in Clinical and Research Settings: Protocols and Scoring

Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating the PICADAR Score

The Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Rule (PICADAR) is a predictive tool designed to estimate the probability of primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) prior to definitive diagnostic testing. This technical guide details the calculation methodology, quantitative performance data, and experimental protocols for implementing PICADAR within research on genetically confirmed PCD populations. Recent evidence from a multicenter study of 269 genetically confirmed PCD patients reveals significant limitations in PICADAR's sensitivity, particularly in subpopulations without laterality defects (61%) or hallmark ultrastructural defects (59%) [9] [6]. This whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for applying PICADAR while contextualizing its performance within the evolving landscape of PCD diagnostic research.

Primary ciliary dyskinesia is a genetically heterogeneous rare lung disease resulting from impaired ciliary function, causing chronic oto-sino-pulmonary disease beginning in early childhood [11]. The complex clinical presentation and genetic diversity of PCD (over 50 known causative genes) have driven development of predictive tools like PICADAR to identify high-probability candidates for definitive diagnostic testing [5]. PICADAR operates as a clinical decision rule that quantifies characteristic features of PCD into a numerical score, providing a standardized approach to prioritize patients for specialized testing including nasal nitric oxide measurement, genetic testing, and transmission electron microscopy [9] [11].

Within research settings, particularly studies focusing on genetically confirmed PCD cohorts, PICADAR serves as a stratification tool and phenotypic quantification metric. However, emerging evidence underscores critical limitations that researchers must incorporate into study design and data interpretation. A 2025 study by Schramm et al. demonstrated that PICADAR's overall sensitivity in genetically confirmed PCD populations is 75%, with dramatically reduced performance in patients with situs solitus (61%) or without hallmark ultrastructural defects (59%) [9] [6]. This indicates that PICADAR fails to identify approximately 25% of genuine PCD cases overall and nearly 40% of cases with specific phenotypic presentations.

PICADAR Calculation Methodology

Clinical Criteria and Scoring Algorithm

The PICADAR score is calculated through a sequential assessment of seven clinical criteria derived from the characteristic PCD phenotype. The assessment begins with an initial gatekeeping question about daily wet cough, as individuals without this symptom are considered negative for PCD according to the rule [9] [6]. For patients reporting daily wet cough, points are assigned across six additional clinical features, with total scores ranging from 0 to 12 points [9].

Table 1: PICADAR Scoring Criteria

| Clinical Feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Initial Screening Question | |

| Presence of daily wet cough | Required to proceed |

| Clinical Features | |

| History of neonatal respiratory symptoms | 2 |

| Presence of cardiac or laterality defects | 2 |

| Presence of persistent rhinitis | 1 |

| History of chronic ear symptoms | 1 |

| History of lower respiratory tract infections | 1 |

| History of chest symptoms starting in first 6 months of life | 1 |

Data derived from validation studies of the PICADAR tool [9] [6]

Interpretation of Scores

The total PICADAR score determines the probability of PCD and corresponding diagnostic recommendations:

Table 2: PICADAR Score Interpretation

| Total Score | Probability of PCD | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| 0-4 | Low | PCD unlikely |

| ≥5 | High | Proceed with definitive PCD testing |

Based on evaluation in genetically confirmed PCD cohorts [9] [6]

The ≥5 point threshold represents the optimal cut-point for identifying high-probability PCD cases, though recent evidence shows this threshold fails to capture substantial portions of genetically confirmed PCD populations, particularly those with atypical presentations [9].

Performance Data in Genetically Confirmed PCD

Recent research evaluating PICADAR in 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD provides critical performance metrics that researchers must incorporate into study design. The overall sensitivity of PICADAR (using the ≥5 point threshold) was 75% (202/269), meaning one-quarter of genetically confirmed PCD cases would have been missed using this tool alone [9] [6]. Notably, 18 individuals (7%) with genetically confirmed PCD reported no daily wet cough and would have been ruled out by the initial PICADAR screening question [6]. The median PICADAR score across the entire cohort was 7 (IQR: 5-9) [9].

Stratified Sensitivity by Clinical Features

Subgroup analyses reveal dramatic variations in PICADAR performance based on clinical presentations:

Table 3: Stratified PICADAR Sensitivity in Genetically Confirmed PCD

| Subgroup | Sensitivity | Median Score (IQR) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Cohort (n=269) | 75% | 7 (5-9) | - |

| With laterality defects | 95% | 10 (8-11) | <0.0001 |

| With situs solitus | 61% | 6 (4-8) | <0.0001 |

| With hallmark ultrastructural defects | 83% | - | <0.0001 |

| Without hallmark ultrastructural defects | 59% | - | <0.0001 |

Data from Schramm et al. (2025) evaluation of 269 genetically confirmed PCD patients [9] [6]

These stratified analyses demonstrate that PICADAR functions effectively as a rule-in tool for classic PCD presentations with laterality defects but performs poorly for patients with situs solitus or normal ciliary ultrastructure. This has significant implications for genetic studies seeking to identify novel PCD genes or genotype-phenotype correlations, as PICADAR may systematically exclude atypical presentations.

Experimental Protocols for PICADAR Validation

Study Population Recruitment

The referenced validation study employed specific methodology for assessing PICADAR in genetically confirmed PCD [6]:

- Inclusion Criteria: Individuals with genetically confirmed PCD through identification of biallelic pathogenic mutations in known PCD genes

- Ethical Considerations: Approval obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Medical Association of Westphalia-Lippe and the University of Muenster (reference number: 2015-104-f-S)

- Data Collection: Retrospective assessment of PICADAR criteria through medical record review and structured interviews

- Statistical Analysis: Sensitivity calculated as proportion of individuals scoring ≥5 points; subgroup comparisons using appropriate statistical tests with significance set at p<0.05

Data Collection Standards

For researchers implementing PICADAR in study protocols, standardized data collection is essential:

- Neonatal Respiratory Symptoms: Documented respiratory distress in term neonates presenting at 12-24 hours of life [11]

- Cardiac/Laterality Defects: Confirmed through imaging (echocardiogram, abdominal ultrasound) including situs inversus totalis, situs ambiguus, or heterotaxy [11]

- Persistent Rhinitis: Year-round, daily nasal congestion starting in infancy without seasonal variation [11] [5]

- Chronic Ear Symptoms: Recurrent otitis media with effusion in first year of life, often requiring pressure equalization tubes [11]

- Lower Respiratory Tract Infections: Recurrent pneumonia or bronchitis documented in medical records [11]

- Early Chest Symptoms: Daily, year-round wet cough beginning in first 6 months of life [5]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for PCD Diagnostic Research

| Research Reagent | Function in PCD Research |

|---|---|

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | Visualizes ciliary ultrastructural defects (ODA, IDA, N-DRC) |

| Nasal Nitric Oxide Measurement System | Measures reduced nNO levels (PCD screening) |

| High-Speed Videomicroscopy | Analyzes ciliary beat patterns and frequency |

| PCD Genetic Testing Panels | Identifies biallelic mutations in >50 PCD-associated genes |

| Immunofluorescence Assays | Detects absence or mislocalization of ciliary proteins |

PICADAR Application Workflow

Discussion and Research Implications

The integration of PICADAR within genetically confirmed PCD research requires careful consideration of its documented limitations. The tool's substantially reduced sensitivity in specific subpopulations (61% in situs solitus, 59% without hallmark ultrastructural defects) indicates it should not serve as the sole inclusion criterion for genetic studies [9] [6]. Researchers investigating genotype-phenotype correlations should recognize that PICADAR effectively identifies classic PCD presentations but systematically underrepresents atypical cases, potentially introducing selection bias in genetic studies.

For drug development professionals, these limitations have implications for clinical trial recruitment and patient stratification. PICADAR may efficiently identify candidates with classic PCD for early-phase trials, but comprehensive genetic testing remains essential for inclusive trial design. Additionally, the 7% of genetically confirmed PCD patients without daily wet cough highlights phenotypic diversity that may impact endpoint selection and outcome measure development [6].

Future research directions should focus on developing enhanced predictive tools that incorporate genetic and ultrastructural data alongside clinical features. The integration of nasal nitric oxide measurement, which was not part of the original PICADAR tool, may improve sensitivity for atypical presentations [5]. Furthermore, disease-specific quality of life measures and quantitative imaging biomarkers may provide complementary approaches to phenotypic characterization in clinical trials.

In conclusion, while PICADAR provides a standardized approach to quantify PCD clinical features, researchers must recognize its limitations in genetically confirmed populations. The tool's variable sensitivity across phenotypic subgroups necessitates complementary diagnostic approaches in both research and clinical practice.

In the diagnostic pathway for Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD)—a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder of motile cilia—the PICADAR tool (PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule) serves as an essential clinical prediction rule for identifying patients who warrant further specialized testing [15]. Developed to address the challenge of nonspecific PCD symptoms and limited access to complex diagnostic facilities, PICADAR provides a standardized approach to risk stratification [15]. This technical guide examines the evidence supporting the recommended cut-off score of ≥5 points, with particular focus on its performance in genetically confirmed PCD populations, a context crucial for research and drug development professionals designing clinical trials or diagnostic protocols.

Quantitative Performance Data of the PICADAR Score

Original Validation Performance

The PICADAR tool was derived and validated through a multi-center study involving 641 consecutive referrals to a PCD diagnostic center [15]. The tool's performance characteristics at the ≥5 point threshold established in the original study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Original PICADAR Performance at ≥5 Cut-off (Derivation Cohort)

| Metric | Performance Value | Study Details |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.90 (90%) | Derivative group (n=641) from University Hospital Southampton [15] |

| Specificity | 0.75 (75%) | 75 PCD-positive, 566 PCD-negative cases [15] |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | 0.91 (internal validation) | Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis [15] |

| AUC (External Validation) | 0.87 | Validation at Royal Brompton Hospital (n=187) [15] |

Performance in Genetically Confirmed PCD Populations

Recent evidence specifically examining PICADAR's performance in genetically confirmed PCD cohorts reveals important limitations, particularly regarding sensitivity. A 2025 study by Schramm et al. evaluated 269 individuals with genetically confirmed PCD and found significantly different performance metrics compared to the original validation study [6].

Table 2: PICADAR Performance in Genetically Confirmed PCD (Schramm et al., 2025)

| Population Subgroup | Sensitivity | Median PICADAR Score (IQR) | Cases Identified/Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Genetically Confirmed PCD | 75% | 7 (5-9) | 202/269 |

| With Laterality Defects | 95% | 10 (8-11) | Not specified |

| With Situs Solitus (normal arrangement) | 61% | 6 (4-8) | Not specified |

| With Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 83% | Not specified | Not specified |

| Without Hallmark Ultrastructural Defects | 59% | Not specified | Not specified |

A critical finding from this recent research is that 7% (18/269) of genetically confirmed PCD individuals reported no daily wet cough, which automatically rules out PCD according to PICADAR's initial gatekeeping question, thereby fundamentally limiting the tool's maximum possible sensitivity in genetically confirmed populations [6].

Performance in Adult Populations with Bronchiectasis

Research has also explored modified PICADAR scores in adult populations. A study applying a modified PICADAR in adults with bronchiectasis found that a lower cut-off point of 2 showed optimal discriminative value, with reported sensitivity of 1.00 and specificity of 0.89 in this specific population [16]. This suggests that PICADAR's performance characteristics may vary significantly across different patient demographics and clinical settings.

PICADAR Scoring Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Tool Structure and Scoring System

PICADAR applies to patients with persistent wet cough and assesses seven clinical parameters easily obtained from patient history [15]. The scoring system and point values are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: PICADAR Scoring Criteria and Point Values

| Clinical Parameter | Point Value |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation | 1 |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | 2 |

| Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 2 |

| Chronic rhinitis | 1 |

| Chronic ear symptoms | 1 |

| Situs inversus | 2 |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 |

The total PICADAR score represents the sum of points from these clinical parameters, with a theoretical range of 0-11 points [15]. The recommended ≥5 point cut-off was established through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses in the original derivation study to optimize sensitivity and specificity [15].

Diagnostic Reference Standard

In the original PICADAR validation study, a positive PCD diagnosis was typically based on a combination of abnormal diagnostic tests, including:

- "Hallmark" transmission electron microscopy (TEM) defects

- "Hallmark" ciliary beat pattern (CBP) abnormalities

- Nasal nitric oxide (nNO) ≤30 nL·min⁻¹ [15]

For patients with a strong clinical history (e.g., sibling with PCD, full clinical phenotype), diagnosis could be confirmed based on either hallmark TEM or repeated high-speed video microscopy analysis (HSVMA) consistent with PCD [15]. This diagnostic approach aligns with European Respiratory Society guidelines, which note the absence of a single gold standard test for PCD [17].

Application in Research Protocols

For research studies focusing on genetically confirmed PCD, the application of PICADAR should follow this standardized protocol:

- Administer initial gatekeeping question: Confirm presence of daily wet cough (if absent, score is 0)

- Systematically assess each of the seven clinical parameters through structured patient interview or medical record review

- Calculate total score by summing applicable point values

- Apply cut-off: Score ≥5 indicates higher probability of PCD warranting confirmatory testing

- Document limitations: Note that sensitivity is reduced in situs solitus and non-hallmark ultrastructure cases

Research Reagent Solutions for PCD Diagnostic Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Reagents for PCD Diagnostic Studies

| Reagent/Equipment | Primary Function in PCD Diagnostics | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescence NO Analyzer | Measures nasal nitric oxide (nNO) concentrations | Key screening tool; nNO markedly reduced in PCD [16] |

| High-Speed Video Microscopy System | Analyzes ciliary beat frequency and pattern | Must assess both frequency and pattern; repeat after air-liquid interface culture recommended [17] |

| Transmission Electron Microscope | Evaluates ciliary ultrastructure | Detects hallmark defects; misses ~26% of PCD cases [18] |

| Genetic Sequencing Panels | Identifies mutations in known PCD genes | Essential for confirming diagnosis, especially in TEM-normal cases [6] |

| Air-Liquid Interface Culture System | Differentiates primary from secondary ciliary dyskinesia | Regrows ciliated epithelium to eliminate secondary damage [15] |

| Immunofluorescence Microscopy Setup | Detects missing ciliary proteins | Emerging diagnostic technique; not yet standardized [17] |

Clinical and Research Implications

The ≥5 point cut-off for PICADAR represents a balanced threshold for identifying patients at sufficient risk for PCD to warrant specialized diagnostic testing in general clinical populations [15]. However, for research focused on genetically confirmed PCD, this cut-off demonstrates substantial limitations, particularly in cases with situs solitus (61% sensitivity) and those without hallmark ultrastructural defects (59% sensitivity) [6].

These findings have significant implications for drug development and study design:

- Clinical Trial Recruitment: Reliance solely on PICADAR for patient screening may systematically exclude approximately 25% of genetically confirmed PCD cases, potentially introducing selection bias [6]

- Diagnostic Protocol Design: PICADAR should be used as part of a multi-step diagnostic pathway rather than a definitive screening tool, particularly in research settings [17]

- Algorithm Refinement: Future predictive tools need improved sensitivity for PCD cases with normal situs and normal ultrastructure, possibly incorporating genetic prevalence data [6]

The European Respiratory Society guidelines currently provide a weak recommendation for using PICADAR to identify patients for diagnostic testing, reflecting the need for careful implementation considering these established limitations [17].

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, genetically heterogeneous disorder affecting approximately 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 40,000 individuals, characterized by impaired mucociliary clearance due to defects in ciliary structure and function [8] [19]. The diagnostic pathway for PCD is complex, with no single gold standard test, requiring a combination of technically demanding and expensive investigations [17] [8]. This diagnostic challenge creates significant barriers to early identification and management, particularly given that symptoms are nonspecific and overlap with other respiratory conditions [15].

The European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force has emphasized the critical importance of appropriate patient selection for specialized PCD testing to avoid both underdiagnosis and overburdening of specialized centers [17]. Within this context, the PrImary CiliAry DyskinesiA Rule (PICADAR) emerges as an evidence-based clinical prediction tool designed to identify patients with high probability of PCD before proceeding with complex confirmatory testing [15]. This technical guide examines the integration of PICADAR into the ERS-recommended diagnostic workflow, with particular focus on its application in research settings involving genetically confirmed PCD.

PICADAR: Development and Validation

Tool Development and Parameters

PICADAR was developed through a prospective study of 641 consecutive patients referred for PCD testing, with 75 (12%) receiving a positive diagnosis [15] [20]. The tool applies specifically to patients with persistent wet cough and incorporates seven clinically accessible parameters obtained through patient history [15]. Through logistic regression analysis, these parameters were identified as significant predictors of PCD and weighted according to their diagnostic contribution [15].

Table 1: PICADAR Parameters and Scoring System

| Parameter | Score |

|---|---|

| Full-term gestation | 1 point |

| Neonatal chest symptoms | 1 point |

| Admission to neonatal intensive care unit | 1 point |

| Chronic rhinitis | 1 point |

| Chronic ear symptoms | 1 point |

| Situs inversus | 2 points |

| Congenital cardiac defect | 2 points |

| Total Possible Score | 9 points |

The scoring system reflects the relative importance of different clinical features, with laterality defects (situs inversus) and congenital cardiac defects carrying the highest weight due to their strong association with PCD pathogenesis [15].

Performance Characteristics

The diagnostic performance of PICADAR has been established through both internal and external validation studies [15]. The tool demonstrates good accuracy in discriminating between PCD-positive and PCD-negative patients when applied to symptomatic populations with chronic wet cough.