Revolutionizing Hematologic Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Analysis of NGS vs. Traditional Methods in Acute Leukemia

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is fundamentally transforming the diagnostic landscape for acute leukemia, offering unprecedented resolution into the genetic architecture of these heterogeneous malignancies.

Revolutionizing Hematologic Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Analysis of NGS vs. Traditional Methods in Acute Leukemia

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is fundamentally transforming the diagnostic landscape for acute leukemia, offering unprecedented resolution into the genetic architecture of these heterogeneous malignancies. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring how NGS surpasses traditional cytogenetics and molecular methods in detecting cryptic fusions, guiding risk stratification, and enabling measurable residual disease (MRD) monitoring. We examine the technical foundations of both approaches, present validated clinical applications across ALL and AML, address implementation challenges including data interpretation and cost considerations, and provide evidence-based comparisons of diagnostic yield. The integration of NGS into diagnostic workflows represents a paradigm shift toward precision medicine, with significant implications for therapeutic development and clinical trial design in hematologic oncology.

The Evolving Diagnostic Landscape: From Morphology to Molecular Precision in Acute Leukemia

The diagnosis of acute leukemia has long relied on a multi-modal approach, with cytomorphology and cytochemistry serving as the foundational first steps in the diagnostic workflow. For decades, these techniques have provided the initial evidence of malignant transformation, guiding subsequent confirmatory testing. While technological advancements have introduced powerful genomic tools like next-generation sequencing (NGS), the microscopic examination of blood and bone marrow specimens remains indispensable for initial diagnosis and classification. This review objectively compares the performance characteristics, applications, and limitations of these traditional cornerstone techniques against emerging molecular methodologies within the integrated diagnostic paradigm for acute leukemia.

The contemporary diagnostic framework for acute leukemia increasingly incorporates artificial intelligence (AI) for image analysis and leverages NGS for comprehensive genomic profiling [1] [2]. These advancements are transforming a field once dominated by manual microscopic review. However, the initial recognition of leukemia still fundamentally depends on the accurate morphological identification of blast cells and their differentiation from normal hematopoietic precursors [2]. This analysis evaluates how traditional and modern techniques complement each other, providing researchers and clinicians with a clear comparison of their respective roles in precision diagnostics.

Traditional Diagnostic Cornerstones: Technical Foundations and Workflows

Cytomorphology: The First Line of Identification

Cytomorphology represents the most fundamental diagnostic procedure in the evaluation of suspected leukemia [3]. The process begins with the preparation of peripheral blood smears (PBS) and bone marrow smears (BMS), which are stained—typically with May-Grünwald-Giemsa or Wright-Giemsa—to reveal cellular details [2]. Microscopic examination then focuses on assessing cell size, nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear chromatin pattern, nucleoli presence and characteristics, and cytoplasmic granulation [3].

In acute leukemias, blasts are typically characterized by increased cell size, a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, reduced cytoplasmic volume, and abnormal granule distribution [2]. The diagnostic threshold for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is generally set at ≥20% blasts in the bone marrow or peripheral blood, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification, though specific genetic abnormalities can define AML even with lower blast percentages [2]. A critical limitation of morphological assessment is its dependence on experienced hematologists and its susceptibility to inter-observer variability, with diagnostic error rates in morphological assessments reportedly as high as 40% [2].

Table 1: Standard Staining Methods in Leukemia Cytomorphology and Cytochemistry

| Staining Method | Primary Application | Key Diagnostic Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| May-Grünwald-Giemsa/Wright-Giemsa | General morphology assessment | Nuclear chromatin pattern, cytoplasmic basophilia, granulation, nucleoli | Cannot identify lineage-specific enzymes |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Myeloid lineage confirmation | Dark cytoplasmic granules in myeloid cells | Negative in immature blasts and monocytic cells |

| Sudan Black B (SBB) | Myeloid lineage confirmation | Stains phospholipids and sterols in granules of myeloid cells | Similar staining pattern to MPO but less specific |

| Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) | Erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation | Block-like positivity in erythroblasts in ALL | Can be positive in other cell types |

| Non-Specific Esterase (NSE) | Monocytic differentiation | Diffuse cytoplasmic staining in monocytic cells | Inhibited by sodium fluoride |

Cytochemistry: Lineage Assignment and Subclassification

Cytochemical staining builds upon morphological assessment by detecting specific intracellular enzymes and substrates that enable lineage assignment. These reactions are crucial for distinguishing between acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and for further classifying AML subtypes [4]. The most established cytochemical stains include myeloperoxidase (MPO) for myeloid lineage, Sudan Black B (SBB) with a similar application, and non-specific esterase (NSE) for monocytic differentiation [4].

The experimental protocol for cytochemical analysis requires standardized conditions to ensure reproducible results. For MPO staining, air-dried blood or bone marrow smears are fixed in formalin-ethanol and incubated with a substrate solution containing hydrogen peroxide and benzidine derivative. Myeloid cells exhibit dark cytoplasmic granules due to peroxidase activity. For NSE staining, smears are fixed in formalin vapor and incubated with alpha-naphthyl acetate as substrate at pH 6.3; monocytic cells show diffuse cytoplasmic staining inhibited by sodium fluoride [4]. The entire staining and interpretation process typically requires 2-4 hours per sample, providing relatively rapid results compared to more complex immunophenotypic or molecular methods.

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Modern Diagnostic Techniques

Diagnostic Accuracy and Turnaround Time

When evaluating diagnostic techniques, performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, turnaround time, and applicability across leukemia subtypes provide critical comparison parameters. Cytomorphology and cytochemistry offer rapid assessment but with limitations in sensitivity and objectivity compared to advanced methodologies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Diagnostic Techniques in Acute Leukemia

| Parameter | Cytomorphology/Cytochemistry | Multiparameter Flow Cytometry | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Turnaround Time | 2-4 hours [2] | 4-6 hours [5] | 24-72 hours [3] [6] |

| Sensitivity for Blast Detection | ~60% (highly operator-dependent) [2] | 1 in 10^4 (10⁻⁴) [5] | 1 in 10^6 (10⁻⁶) for MRD [5] [7] |

| Lineage Assignment Accuracy | 70-80% (with cytochemistry) [4] | >95% [4] | Indirect through mutation patterns |

| Subclassification Capability | Basic (FAB classification) | Intermediate (immunologic subtypes) | High (molecular subtypes) |

| Operator Dependency | High (error rate up to 40%) [2] | Moderate (requires expertise) [5] | Low (automated pipelines) |

| Capital Equipment Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling via NGS

Next-generation sequencing represents the most technologically advanced approach for leukemia diagnosis and classification. NGS enables massive parallel sequencing of thousands of genes in a single test, simultaneously detecting single nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy-number alterations, and structural variants including balanced rearrangements [8]. The experimental protocol involves DNA extraction from peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirates, library preparation with fragmentation and adapter ligation, followed by massive parallel sequencing and complex bioinformatic analysis [4].

Targeted NGS panels have emerged as the preferred clinical application, focusing on genes with established diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic relevance in acute leukemia [4]. The sensitivity of NGS depends on sequencing depth (coverage), with panel-based approaches typically targeting >1000x coverage, enabling detection of variants with ~5% variant allele frequency (VAF) [4]. For measurable residual disease (MRD) monitoring, NGS offers exceptional sensitivity down to 10⁻⁶, significantly surpassing the capabilities of morphology (5% sensitivity) and flow cytometry (10⁻⁴ sensitivity) [5] [7].

Long-read sequencing technologies, such as Oxford Nanopore platforms, further expand diagnostic capabilities by enabling real-time genomic characterization. Recent studies demonstrate that adaptive sampling whole genome sequencing can identify driving alterations in pediatric acute leukemia in as little as 15 minutes for karyotype abnormalities and up to 6 hours for complex structural variants [6]. This represents a dramatic reduction from the 24-72 hours typically required for short-read NGS approaches [3].

Integrated Diagnostic Workflows: From Microscopy to Precision Medicine

The modern diagnosis of acute leukemia employs an integrated workflow that begins with traditional techniques and progresses through increasingly specialized molecular analyses. This sequential approach maximizes both efficiency and diagnostic accuracy.

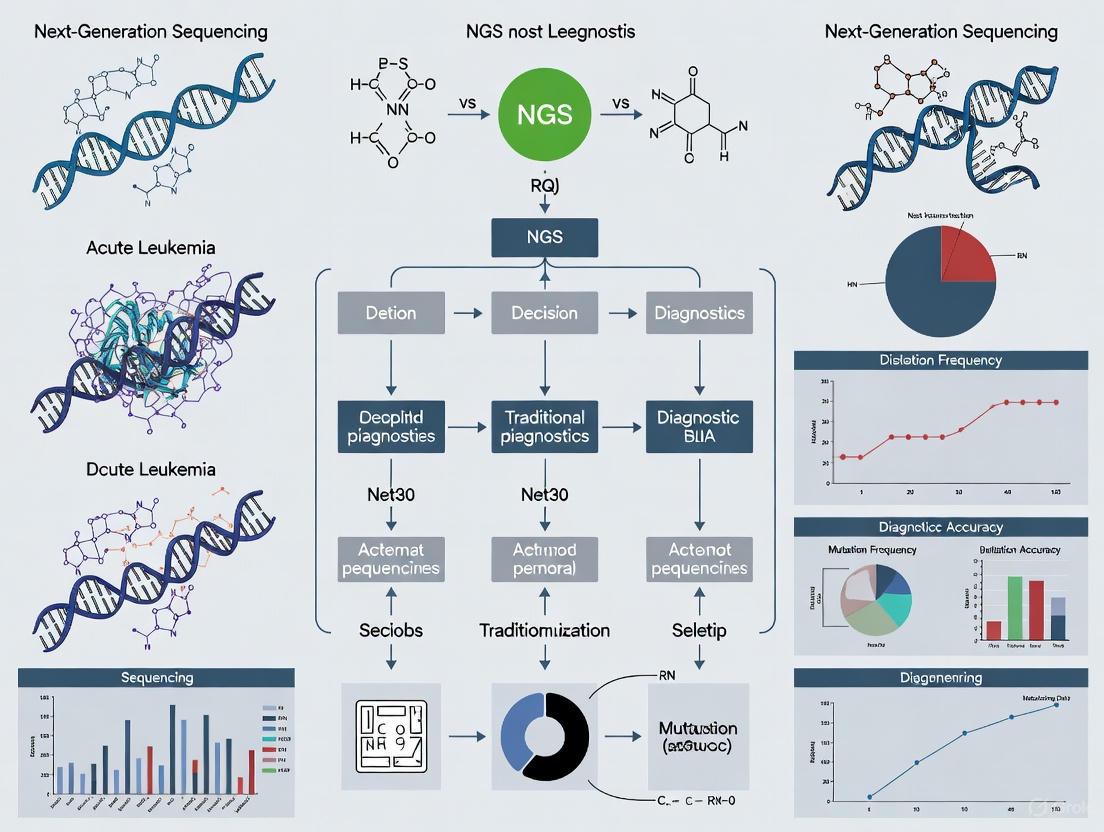

Diagram 1: Integrated Diagnostic Workflow for Acute Leukemia (Max Width: 760px)

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Leukemia Diagnostics

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morphological Stains | May-Grünwald-Giemsa, Wright-Giemsa | Cellular visualization and differential counting | Standardized staining protocols essential for consistency |

| Cytochemical Stains | MPO, SBB, NSE, PAS | Lineage determination and FAB classification | Requires positive and negative controls for validation |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies | CD45, CD34, CD33, CD13, CD19, CD3 | Immunophenotyping and blast characterization | 8+ color panels now standard for comprehensive analysis |

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Illumina DNA Prep, Swift Accel AML | Target enrichment and library construction | Unique dual indexing reduces index hopping |

| NGS Hybridization Panels | Custom myeloid/lymphoid panels | Targeted sequencing of relevant genes | Panels typically cover 50-200 genes with >1000x coverage |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GATK, ClinVar, COSMIC, IGV | Variant calling and annotation | AI-assisted pathogenicity prediction emerging |

Cytomorphology and cytochemistry remain indispensable initial diagnostic procedures for acute leukemia, providing rapid assessment that guides subsequent testing. Their strengths lie in low cost, rapid turnaround, and ability to survey the complete cellular landscape. However, these traditional techniques demonstrate significant limitations in sensitivity, objectivity, and molecular resolution when compared to modern methodologies.

The integration of AI for image analysis and the application of NGS for comprehensive genomic profiling represent transformative advancements in leukemia diagnostics. NGS-based approaches provide unparalleled sensitivity for MRD detection and enable precision medicine through identification of therapeutic targets. Rather than rendering traditional methods obsolete, these technological advancements have redefined their role within a sophisticated diagnostic ecosystem where each technique contributes unique, complementary information. The future of leukemia diagnosis lies not in replacement of traditional methods, but in their intelligent integration with genomic technologies to provide comprehensive diagnostic insights that guide targeted therapeutic interventions.

Multiparameter Flow Cytometry for Immunophenotyping and Lineage Assignment

Accurate diagnosis and classification of acute leukemia are fundamental to selecting appropriate therapy and predicting patient outcomes. This process traditionally relied on morphological examination, but the inherent limitations of morphology have necessitated more precise technologies. Multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) has emerged as a cornerstone technology for immunophenotyping and lineage assignment in leukemia diagnosis by enabling the simultaneous measurement of multiple physical and chemical characteristics of individual cells as they flow past lasers in a focused fluid stream [9]. Within the context of modern hematopathology, MFC must now be evaluated alongside next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, which offer deep insights into the genetic underpinnings of disease. The central thesis of this guide is that while NGS provides unparalleled genetic characterization, MFC delivers rapid, functional immunophenotypic data at the single-cell level, and the two technologies are often complementary rather than mutually exclusive in acute leukemia diagnostics [10].

The critical importance of lineage assignment was highlighted in a study of 100 acute leukemia cases, where immunophenotyping by MFC significantly changed the lineage diagnosis compared to morphology alone in 16% of cases (p<0.001) [11]. This reclassification has direct therapeutic implications, as misdirected therapy based on inaccurate lineage assignment can lead to poor outcomes. Meanwhile, the detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) has emerged as a powerful prognostic indicator, with studies demonstrating that MRD levels at specific treatment timepoints strongly predict relapse risk in both acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [12] [10]. This comparison guide will objectively evaluate the performance of MFC against alternative technologies, particularly NGS, focusing on their respective roles in immunophenotyping, lineage assignment, and MRD detection within acute leukemia research and diagnosis.

Principles of Multiparameter Flow Cytometry

Multiparameter flow cytometry operates on the principle of hydrodynamic focusing to guide cells single-file past one or multiple laser beams. As cells intersect with these lasers, they scatter light and emit fluorescence from conjugated antibodies, providing rich data on cell size, granularity, and the presence of specific surface and intracellular markers [9]. Modern flow cytometers can simultaneously detect up to 20-30 parameters per cell, enabled by advances in laser technology, fluorescent dye chemistry, and optical detection systems [9]. The strength of MFC lies in its ability to rapidly analyze thousands of cells per second, providing quantitative data on heterogeneous cell populations within a sample.

For immunophenotyping, fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies are used to probe well-characterized molecules that serve as biomarkers associated with particular cell types in normal or disease states [9]. The simultaneous measurement of multiple fluorescence parameters allows detailed analyses of co-expressed structural, receptor, signaling, and effector molecules. In the context of leukemia, this enables the identification of leukemia-associated immunophenotypes (LAIPs)—abnormal patterns of antigen expression that deviate from normal hematopoietic progenitors [10]. These alterations can include overexpression or underexpression of antigens normally present, asynchronous expression of markers typically restricted to specific developmental stages, or aberrant expression of lineage-inappropriate antigens [10].

Key Methodologies for MFC in Leukemia Diagnostics

Sample Preparation and Staining Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for reliable MFC results. Bone marrow or peripheral blood samples are typically collected with anticoagulants such as heparin or EDTA. For the standardized EuroFlow method used in multiple myeloma MRD detection, a lyse-wash-and-stain sample preparation protocol is employed, measuring high numbers of cells (≥5×10⁶ cells/tube) to achieve sensitive detection of rare cell populations [13]. The staining process involves incubating cells with antibody panels under optimized conditions—typically room temperature for 30 minutes in the dark—followed by washing steps to remove unbound antibody [14] [15].

For intracellular antigen detection, such as phosphorylated signaling proteins or cytoplasmic immunoglobulins, cells must first be fixed and permeabilized using specialized buffers. The optimization of these protocols is challenging, as many buffers used for intracellular epitope detection can adversely affect surface marker staining [9]. As noted in salivary gland research, permeabilization with 100 μL BD Phosflow Perm Buffer II (64.9% methanol) for 30 minutes at -20°C, followed by intracellular antibody staining overnight at 4°C, has proven effective for preserving both surface and intracellular epitopes [14].

Instrument Setup and Quality Control

Robust instrument setup and quality control procedures are essential for generating reproducible MFC data. The voltage walk method is recommended for determining the minimum voltage requirement (MVR) for each detector, allowing clear resolution of dim fluorescent signals from background noise [15]. This process involves running dimly fluorescent beads at increasing voltage settings and plotting the coefficient of variation (CV) against the voltages to identify the optimal setting.

Antibody titration is another critical optimization technique for multiparameter flow cytometry, helping to minimize nonspecific binding and increase signal detection [15]. As illustrated in Figure 2 of the best practices guide, performing serial 2-fold dilutions from the manufacturer's recommended concentration and plotting the stain index (SI) helps identify either a separating concentration (providing greatest difference between positive and negative cells) or a saturating concentration (required for low-abundance antigens) [15]. Appropriate controls, including fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls, compensation controls, and viability controls, are indispensable for accurate data interpretation in multiparameter panels [15].

Next-Generation Sequencing Methodologies

In contrast to MFC's protein-focused approach, NGS technologies sequence DNA or RNA to identify genetic alterations in leukemia cells. For MRD detection, the ImmunoSEQ platform (Adaptive Biotechnologies) can be used to sequence immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor genes, tracking malignant clones based on their unique receptor rearrangements [13]. Sample processing for NGS involves nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, target enrichment or amplification, and sequencing on platforms such as Illumina or Ion Torrent systems [16]. The analytical sensitivity of NGS-based MRD detection depends on sequencing depth, with deeper sequencing enabling more sensitive detection of rare clones.

Performance validation of NGS assays requires demonstrating analytical sensitivity (detection limit), analytical specificity, and accuracy using well-characterized reference materials [16]. For qualitative detection, verification requires at least 5 negative and 10 positive samples (including weak positives), with expected 100% positive and negative agreement [16]. The validation process must also establish the linear range, precision, and reference intervals for the assay.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Lineage Assignment in Acute Leukemia

The accurate determination of lymphoid versus myeloid lineage is a critical first step in acute leukemia management, as it dictates fundamentally different treatment approaches. The comparative performance of MFC versus morphology and NGS in this domain reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each technology.

Table 1: Comparison of Technologies for Acute Leukemia Lineage Assignment

| Technology | Methodology | Turnaround Time | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphology | Microscopic examination of stained cells | Hours (after processing) | Low cost, rapid assessment of cell structure | Subjective interpretation, limited accuracy |

| Multiparameter Flow Cytometry | Detection of surface and intracellular proteins using antibody panels | 4-6 hours | High accuracy for lineage assignment, rapid results, detects aberrant immunophenotypes | Limited to known protein targets |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Detection of genetic alterations (mutations, fusions) | Days to weeks | Identifies therapeutic targets, prognostic markers | Does not directly assess protein expression |

A direct comparison study of 100 acute leukemia cases demonstrated the superior accuracy of MFC over morphology alone. While morphology established lineage in all cases, MFC significantly reclassified lineage assignment in 16% of cases (p<0.001) [11]. In 8 cases, what was initially classified as myeloid by morphology was reclassified as lymphoid by MFC, while another 8 cases originally called lymphoid were reclassified as myeloid [11]. This reclassification has profound clinical implications, as it directly determines whether a patient receives lymphoid-directed or myeloid-directed chemotherapy.

NGS contributes to lineage assessment indirectly by identifying genetic alterations characteristic of specific lineages, such as the RUNX1-RUNX1T1 fusion in AML or ETV6-RUNX1 in ALL. However, NGS does not directly assess protein expression and thus cannot replace MFC for immunophenotypic lineage assignment. Instead, the integration of MFC and genetic methods provides the most comprehensive diagnostic picture.

Minimal Residual Disease Detection

MRD detection has emerged as one of the most powerful prognostic factors in acute leukemia, with both MFC and NGS offering sensitive approaches for detecting submicroscopic disease.

Table 2: Comparison of MRD Detection Performance Between MFC and NGS

| Parameter | Multiparameter Flow Cytometry | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity | Typically 0.001%-0.01% (10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁵) [10] [13] | Can exceed 0.0001% (10⁻⁶) with sufficient sequencing depth [13] |

| Applicability | >90% of AML cases [10] | Virtually 100% for B-ALL with immunoglobulin receptor targets |

| Key Strengths | Rapid turnaround, functional protein data, widely available | High sensitivity, clonal tracking ability, standardized quantification |

| Key Limitations | Requires fresh samples, expertise-dependent analysis | Higher cost, longer turnaround, complex bioinformatics |

In B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), MFC-based MRD monitoring at specific timepoints provides powerful prognostic information. A study of 153 pediatric B-ALL patients found that MRD levels ≥1×10⁻³ at day 33 of induction therapy were associated with significantly lower 3-year relapse-free survival (RFS) rates (33.0% vs 89.3%, P=0.000) [12]. Similarly, at day 84, MRD ≥1×10⁻⁴ was associated with higher relapse rates (41.7% vs 13.0%, P=0.022) [12]. These findings demonstrate the clinical utility of MFC-MRD monitoring for risk stratification.

In core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia (CBF-AML), direct comparisons between MFC and molecular methods reveal a more complex relationship. One study of 93 CBF-AML patients found only weak agreement between MFC and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) during consolidation therapy (κ=0.083) and maintenance/follow-up (κ=0.164) [10]. Notably, in cases with intermediate qRT-PCR results (0.1-10%), MFC provided additional prognostic value for relapse prediction (P=0.006) [10], suggesting complementary roles for the two technologies.

In multiple myeloma, a comparison of 8-color MFC (EuroFlow method) and NGS for MRD detection in autografts found that NGS offered higher sensitivity, detecting MRD in 82% of cases versus 55% by MFC [13]. While there was a correlation between MRD levels measured by both methods, only NGS-negative cases showed a trend toward better progression-free survival (P=0.114), suggesting superior prognostic value for NGS in this specific context [13].

Figure 1: Comparative MRD Detection Workflow Using MFC and NGS

Comprehensive Diagnostic Profiling

The most advanced diagnostic approaches for acute leukemia integrate multiple technologies to achieve comprehensive disease characterization. MFC excels at providing rapid immunophenotypic profiling, while NGS offers deep genetic characterization. The evolving diagnostic paradigm leverages the respective strengths of each technology.

Immunophenotypic profiling by MFC typically employs standardized antibody panels tailored to specific clinical questions. For example, the EuroFlow consortium has developed optimized 8-color, 2-tube antibody panels for multiple myeloma MRD detection that include markers such as CD138, CD27, CD38, CD56, CD45, CD19, CD117, CD81, and cytoplasmic immunoglobulin light chains [13]. Similarly, for CBF-AML, comprehensive 8-color panels incorporate markers including CD7, CD33, CD19, CD34, CD13, CD38, CD45, HLA-DR, CD117, CD4, CD123, and others to identify aberrant immunophenotypes [10].

Genetic profiling by NGS can identify mutations with prognostic and therapeutic significance, such as TP53, FLT3, NPM1, and IDH1/2 in AML. The integration of immunophenotypic and genetic data enables more precise risk stratification and therapeutic selection than either approach alone.

Essential Reagents and Research Solutions

Successful implementation of MFC for leukemia immunophenotyping requires access to high-quality reagents and standardized protocols. The following research toolkit outlines essential components for robust MFC analysis.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Leukemia Immunophenotyping

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorochrome-Conjugated Antibodies | CD45-V500, CD38-FITC, CD10-PE, CD20-PE-Cy7, CD19-APC, CD34-PerCP-cy5.5, CD33-BV421 [12] | Cell identification and lineage determination |

| Viability Dyes | LIVE/DEAD Fixable Violet Dead Cell Stain [15] | Exclusion of dead cells to reduce non-specific binding |

| Sample Preparation Reagents | BD Cytofix Fixation Buffer, BD Phosflow Perm Buffer II [14] | Cell fixation and permeabilization for intracellular staining |

| Cell Separation Kits | MojoSort Human CD45 Selection Kit [14] | Immune cell enrichment from complex tissues |

| Standardization Tools | BD Quantibrite Beads [9] | Quantitation of cell-surface marker expression |

| Tissue Dissociation Kits | Human Multi Tissue Dissociation Kit [14] | Preparation of single-cell suspensions from solid tissues |

The careful selection and titration of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies is particularly critical for panel performance. As noted in best practices guides, bright fluorophores should be paired with antibodies for low-abundance targets, while dimmer fluorophores are suitable for highly expressed antigens [15]. This strategy helps minimize spillover spreading and optimizes resolution of dim populations. Antibody titration is essential for identifying the optimal concentration that provides clear separation between positive and negative populations while conserving reagent and minimizing background [15].

For specialized applications such as analysis of signaling pathways, additional reagents for intracellular staining are required. Studies of Sjögren's Disease minor salivary glands, for example, successfully detected phosphorylated interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) following methanol-based permeabilization and overnight antibody incubation at 4°C [14]. Similar approaches can be adapted for leukemia signaling studies.

Figure 2: Technology Integration in Leukemia Diagnostics

Multiparameter flow cytometry remains an indispensable technology for immunophenotyping and lineage assignment in acute leukemia diagnosis. Its strengths include rapid turnaround, ability to analyze protein expression at single-cell resolution, and widespread availability in clinical laboratories. The evidence demonstrates that MFC significantly improves diagnostic accuracy over morphology alone, with 16% of cases being reclassified upon immunophenotypic analysis [11]. For MRD monitoring, MFC provides clinically actionable information at multiple treatment timepoints, with specific thresholds (e.g., ≥1×10⁻³ at day 33) showing significant prognostic value in B-ALL [12].

While NGS technologies offer superior sensitivity for MRD detection in some contexts [13] and unparalleled ability to identify genetic alterations, they complement rather than replace MFC in the diagnostic workflow. In CBF-AML, for example, MFC and molecular methods show only weak agreement, with MFC providing prognostic value particularly in cases with intermediate qRT-PCR results [10]. This suggests that these technologies capture different biological aspects of residual disease.

The future of leukemia diagnostics lies in the intelligent integration of multiple technologies, leveraging the respective strengths of MFC for immunophenotyping and NGS for genetic characterization. Standardized 8-color MFC protocols such as the EuroFlow method enhance reproducibility across laboratories [13], while ongoing developments in mass cytometry and spectral flow cytometry promise even higher parameter analysis. For researchers and clinicians, the optimal approach involves selecting technology combinations based on specific clinical questions, available resources, and the need for rapid versus comprehensive diagnostic information. As both technologies continue to evolve, their synergistic application will undoubtedly advance our understanding and management of acute leukemia.

The diagnosis and risk stratification of acute leukemia have long relied on conventional cytogenetic techniques to identify chromosomal abnormalities that drive disease pathogenesis and progression. Karyotyping and Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) represent two foundational methods in the cytogeneticist's toolkit, providing complementary insights into the genomic landscape of hematologic malignancies [17]. While next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies are increasingly transforming diagnostic paradigms, traditional cytogenetic methods remain clinically indispensable for detecting chromosomal abnormalities in acute leukemia [18] [19]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of karyotyping and FISH, examining their technical principles, performance characteristics, and clinical applications within the evolving context of modern genomic medicine. Understanding the relative strengths and limitations of these established techniques is paramount for researchers and clinicians navigating the complex genetic landscape of acute leukemia and optimizing diagnostic workflows in the NGS era.

Technical Principles and Methodologies

Karyotyping: Macroscopic Genomic Analysis

Karyotyping is a classical cytogenetic technique that provides a macroscopic overview of the entire genome, allowing for the simultaneous assessment of chromosomal number and structure. The standard workflow begins with cell culture, where viable cells from bone marrow or blood samples are stimulated to proliferate and arrested during metaphase, the stage of cell division where chromosomes are most condensed and visible [17]. These metaphase cells are then harvested, fixed on slides, and subjected to banding techniques—most commonly G-banding using Giemsa stain—which produces a characteristic pattern of light and dark bands unique to each chromosome type [17]. The stained chromosomes are visualized under a microscope, captured digitally, and systematically arranged into a karyogram based on their size, banding pattern, and centromere position for analysis. This process enables the detection of numerical abnormalities (aneuploidy) and large-scale structural rearrangements including translocations, deletions, duplications, and inversions, typically at a resolution of 5-10 megabases [20]. A significant limitation of this technique is its requirement for viable, actively dividing cells and the expertise needed for complex interpretation.

FISH: Targeted Molecular Cytogenetics

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) represents a molecular cytogenetic approach that bridges the gap between traditional karyotyping and modern molecular genetics. This technique utilizes fluorescently labeled DNA probes that are complementary to specific chromosomal sequences or genes of interest [17]. The FISH protocol involves preparing interphase or metaphase cells on slides, denaturing both the chromosomal DNA and the probes to create single-stranded DNA, and allowing the probes to hybridize to their complementary target sequences. After washing away unbound probe, the samples are visualized using a fluorescence microscope [21]. The presence, absence, or abnormal positioning of fluorescent signals reveals specific genetic abnormalities, including microdeletions, translocations, and aneuploidies, often at a much higher resolution than karyotyping—down to hundreds of kilobases depending on the probe design [21]. FISH can be performed on non-dividing (interphase) cells, circumventing the need for cell culture, and allows for the analysis of hundreds to thousands of cells to detect low-level mosaicism [22]. Various FISH adaptations exist, including multicolor FISH (mFISH) and spectral karyotyping (SKY), which enable the simultaneous visualization of all chromosomes using chromosome-specific painting probes [17].

Visualizing the Diagnostic Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complementary roles of karyotyping, FISH, and NGS in a comprehensive diagnostic workflow for acute leukemia:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Diagnostic Accuracy in Clinical Settings

Multiple studies have systematically compared the diagnostic performance of karyotyping and FISH across various hematologic malignancies. In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), both techniques demonstrate high reciprocal agreement for detecting major prognostic translocations such as t(9;22)(BCR::ABL1), t(12;21)(TEL/AML1), and t(11q23)(MLL rearrangements) [18]. However, their sensitivities vary significantly for specific abnormalities. Karyotyping shows notably lower sensitivity (approximately 70-80%) for detecting the TEL-AML1 fusion gene, whereas FISH reliably identifies this rearrangement [18]. Similarly, in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL), a comparative study of 69 patients found conventional karyotyping was abnormal in only 65% of cases and detected 14q32/TCL1 rearrangements in just 43%, while TCL1 rearrangement assessment by FISH was positive in 85% of cases [22]. This demonstrates FISH's superior sensitivity for identifying specific, clinically significant rearrangements that may be cryptic or missed by karyotyping alone.

Technical Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of karyotyping and FISH based on experimental data from clinical studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Karyotyping and FISH in Leukemia Diagnostics

| Parameter | Karyotyping | FISH |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | 5-10 Mb [20] | 100-500 kb (probe-dependent) [17] |

| Cell Requirement | Viable, actively dividing cells required [17] | Non-dividing (interphase) or metaphase cells [21] |

| Turnaround Time | 7-14 days (culture-dependent) [17] | 24-72 hours (minimal culture) [21] |

| Success Rate | ~86% (due to culture failure) [20] [23] | >95% (avoids culture issues) [23] |

| Abnormality Detection Scope | Genome-wide, unbiased screening [17] | Targeted analysis of specific loci [22] |

| Sensitivity for Specific Abnormalities | Variable (e.g., ~70-80% for TEL-AML1) [18] | High (>85% for most targeted abnormalities) [18] [22] |

| Mosaicism Detection | Limited to ~5-10% in metaphases | Can detect 1-5% in interphase nuclei [21] |

Complementary Diagnostic Value

Despite their individual limitations, karyotyping and FISH provide complementary information that enhances overall diagnostic accuracy. Karyotyping offers an unbiased genome-wide assessment that can reveal unexpected chromosomal abnormalities and provide a comprehensive view of the chromosomal landscape, including complex rearrangements [22]. Meanwhile, FISH delivers targeted, high-resolution analysis of specific genomic regions with enhanced sensitivity, making it particularly valuable for identifying cryptic abnormalities, monitoring minimal residual disease, and analyzing samples with low mitotic indices [18] [22]. This complementary relationship was demonstrated in a study of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) where the combination of cytogenetic analyses and targeted FISH markers yielded evaluable results in 91% of cases, with NGS enabling risk stratification in the remaining cases where conventional cytogenetics failed [23]. The integrated use of both techniques remains crucial because any detection of a significant chromosomal aberration, irrespective of the diagnostic mode, must be considered in therapy planning and risk assessment [18].

Experimental Protocols for Acute Leukemia Analysis

Standard Karyotyping Protocol for Bone Marrow Samples

The following detailed protocol is adapted from established clinical laboratory procedures for karyotypic analysis of acute leukemia samples [17]:

Sample Collection and Culture: Under aseptic conditions, collect 1-2 mL of bone marrow aspirate into sodium heparin tubes. Inoculate 0.5-1.0 mL of marrow into 10 mL of chromosome media containing phytohemagglutinin or other mitogens. Culture for 24-48 hours at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ incubator. For certain abnormalities with poor growth characteristics (e.g., monosomy 7), multiple cultures with different harvest times may be necessary.

Metaphase Arrest and Harvesting: Add colcemid (0.05 μg/mL final concentration) to the culture for 15-30 minutes to arrest cells in metaphase. Transfer cells to centrifuge tubes and pellet by centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 10 minutes. Carefully resuspend the cell pellet in pre-warmed 0.075 M KCl hypotonic solution and incubate for 20-30 minutes at 37°C. Fix cells by slowly adding 3:1 methanol:acetic acid fixative, then perform three additional fixative changes with 15-minute intervals.

Slide Preparation and Banding: Drop the fixed cell suspension onto clean, wet microscope slides and allow to air dry. Age slides overnight at 60°C or by artificial aging methods. Perform G-banding using trypsin-EDTA treatment followed by Giemsa staining. Optimize trypsin exposure time to achieve optimal banding resolution (typically 350-400 bands per haploid genome).

Microscopy and Karyotype Analysis: Screen slides under low magnification to identify well-spread metaphase cells with minimal chromosome overlap. Capture 20-30 metaphase images using an automated cytogenetics imaging system. Analyze each metaphase for chromosomal number and structure. Arrange chromosomes into a standardized karyogram according to ISCN (International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature) guidelines.

FISH Protocol for Leukemia-Associated Translocations

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for detecting common leukemia-associated translocations using locus-specific FISH probes [21]:

Slide Preparation and Denaturation: Select areas with adequate cellularity on fixed specimen slides. Dehydrate slides through an ethanol series (70%, 85%, 100%) for 2 minutes each and air dry. Denature chromosomal DNA by incubating slides in 70% formamide/2× SSC solution at 73°C for 5 minutes. Immediately dehydrate through cold ethanol series (70%, 85%, 100%) for 2 minutes each and air dry.

Probe Preparation and Hybridization: For each target area, prepare 10 μL of hybridization mixture containing 7 μL of LSI/WCP probe mixture, 2 μL of purified water, and 1 μL of DNA. Denature the probe mixture at 73°C for 5 minutes and pre-anneal at 37°C for 15-30 minutes. Apply denatured probe to the denatured slide target area, cover with a coverslip, and seal with rubber cement. Hybridize in a moist chamber at 37°C for 12-16 hours (overnight).

Post-Hybridization Washes and Detection: Remove coverslip and perform stringency washes in 0.4× SSC/0.3% NP-40 at 73°C for 2 minutes, followed by 2× SSC/0.1% NP-40 at room temperature for 1 minute. Air dry slides in darkness. Counterstain with 10-15 μL of DAPI/Antifade solution and apply coverslip.

Signal Enumeration and Interpretation: Analyze slides using a fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filter sets. Score a minimum of 200 interphase nuclei or 20 metaphase cells for specific signal patterns. For BCR::ABL1 fusion detection, for example, count cells showing juxtaposition of green (BCR) and red (ABL1) signals, indicating fusion. Establish normal cut-off values for false positives by analyzing control samples, typically setting the threshold at 1-5% depending on the probe type [21].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of karyotyping and FISH requires specific reagent systems optimized for hematologic malignancies. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in leukemia cytogenetics:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Leukemia Cytogenetics

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Culture Media | Chromosome Medium P with phytohemagglutinin; RPMI-1640 with growth factors | Metaphase chromosome preparation | Optimize culture duration (24-72h) based on blast count; use multiple harvest times for complex abnormalities |

| Chromosome Banding Reagents | Trypsin-EDTA solution; Giemsa stain; Wright's stain | G-banding pattern generation | Titrate trypsin concentration (0.025-0.05%) for optimal banding resolution (350-400 bands) |

| FISH Probe Systems | LSI BCR/ABL ES Dual Color; LSI MLL Break Apart; CEP 8 SpectrumOrange | Detection of leukemia-specific translocations and aneuploidies | Validate each probe batch with positive and negative controls; establish laboratory-specific cut-off values |

| Hybridization Buffers | Formamide-based denaturation solutions; SSC wash buffers; NP-40 detergents | Stringency control in FISH | Maintain consistent pH (7.0-7.5) and temperature (±0.5°C) for reproducible stringency washes |

| Counterstains & Mounting Media | DAPI/Antifade; ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant | Chromatin visualization and signal preservation | Use antifade mounting medium to prevent photobleaching during fluorescence microscopy |

Integration with Next-Generation Sequencing

The emergence of NGS technologies has transformed the diagnostic landscape for acute leukemia, yet conventional cytogenetics maintains a crucial role in comprehensive genomic assessment. Modern integrated approaches combine these methodologies to leverage their complementary strengths. A 2025 study on pediatric AML demonstrated that an integrated whole genome and whole transcriptome sequencing (iWGS-WTS) approach improved identification of clinically relevant genetic alterations while streamlining diagnostic workflows [24]. However, even with advanced NGS implementation, certain chromosomal abnormalities—particularly balanced translocations, complex rearrangements, and aneuploidies—remain readily detectable by conventional cytogenetics [24] [23].

In clinical practice, karyotyping continues to provide the initial genome-wide screen for chromosomal abnormalities, followed by targeted FISH analysis for specific prognostic markers and NGS for mutation profiling. This tiered approach maximizes diagnostic yield while conserving resources. Real-world data from an Austrian tertiary care center showed that while NGS successfully enabled risk stratification in cases where conventional karyotyping failed (due to dry taps or culture failure), the combination of cytogenetics and targeted FISH markers still provided critical structural information that complemented NGS findings [23]. The continuing evolution of diagnostic workflows suggests that rather than being replaced by NGS, conventional cytogenetics will increasingly be integrated with molecular methods to provide a comprehensive genomic profile that guides risk-adapted therapy in acute leukemia.

Karyotyping and FISH remain indispensable tools in the diagnostic workup of acute leukemia, each offering distinct advantages that continue to complement emerging genomic technologies. Karyotyping provides an unbiased genome-wide assessment of chromosomal integrity, while FISH delivers targeted, sensitive detection of specific prognostic markers. Their combined use, often in conjunction with NGS, creates a powerful diagnostic synergy that enhances abnormality detection, refines risk stratification, and informs therapeutic decisions. As precision medicine in hematologic malignancies continues to advance, the integration of conventional cytogenetics with molecular methods will remain fundamental to unraveling the complex genomic landscape of acute leukemia and optimizing patient outcomes.

Acute leukemias represent a heterogeneous group of hematologic malignancies characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of immature lymphoid or myeloid cells. The molecular revolution in hematology has fundamentally transformed our understanding of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), revealing complex genetic landscapes that drive pathogenesis, prognosis, and therapeutic responses. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a powerful tool that surpasses conventional diagnostic approaches by providing comprehensive genomic profiling, enabling high-resolution detection of genetic mutations, clonal evolution, and resistance mechanisms [19]. This technological advancement has catalyzed a shift from morphology-based classifications to molecularly-driven diagnostic frameworks that integrate genetic abnormalities with clinical decision-making, ultimately paving the way for precision medicine in leukemia management.

The clinical integration of NGS presents both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges. While conventional methods like cytomorphology, multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC), and cytogenetics remain fundamental to leukemia diagnosis, they offer limited resolution for detecting subtle genetic alterations that inform risk stratification and targeted treatment selection [25]. NGS technologies now enable the identification of molecular markers with prognostic significance, allowing for more refined classification systems and dynamic disease monitoring through measurable residual disease (MRD) assessment [26]. This comparative analysis examines the evolving roles of established and emerging diagnostic methodologies in elucidating the genetic drivers of ALL and AML, with particular emphasis on their technical capabilities, clinical applications, and performance characteristics in contemporary practice.

Traditional Diagnostic Methods: Established Approaches and Limitations

Conventional Techniques in Leukemia Diagnosis

The diagnostic workup for acute leukemias has historically relied on an integrated approach employing multiple complementary techniques. Cytomorphology serves as the foundational first step, providing rapid assessment of cellular morphology and enabling initial classification based on French-American-British (FAB) criteria [25] [2]. This method remains indispensable for diagnosing AML and differentiating it from other hematological neoplasms, though it suffers from significant inter-observer variability and limited sensitivity for genetic characterization. Multiparameter flow cytometry (MFC) adds critical immunophenotyping data, allowing for detection, characterization, and quantification of normal and malignant cell populations through surface and cytoplasmic antigen expression patterns [5] [25]. MFC also facilitates sensitive MRD monitoring by identifying aberrant immunophenotypic features of leukemic cells, with typical sensitivity reaching 10⁻⁴ [5].

Cytogenetic analysis through chromosome banding and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) provides essential information about numerical and structural chromosomal alterations that define prognostically significant leukemia subtypes [19] [25]. These techniques identify critical biomarkers such as the Philadelphia chromosome in ALL [19] and various translocations in AML that guide risk stratification according to European LeukemiaNet (ELN) guidelines [25]. Molecular techniques including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) enable sensitive detection and quantification of specific genetic abnormalities, achieving sensitivities up to 10⁻⁶, making them particularly valuable for MRD assessment [25]. However, these targeted approaches require prior knowledge of specific mutations and cannot comprehensively profile the diverse genetic alterations present in acute leukemias.

Limitations of Conventional Approaches

Despite their established role in leukemia diagnostics, traditional methods present several significant limitations. Morphological evaluation depends heavily on experienced hematologists and is susceptible to subjective interpretation, with diagnostic error rates reportedly as high as 40% [2]. Flow cytometry results vary considerably across laboratories due to differences in detection protocols, antibody panel configurations, and analytical standards, compromising reproducibility [2]. While cytogenetics identifies clinically relevant chromosomal abnormalities, it requires cell culture and has limited resolution for detecting subtle structural variations and point mutations [19].

Molecular techniques like qPCR, though highly sensitive for known targets, have restricted applicability. In ALL, qPCR for immunoglobulin (Ig) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements is laborious and time-consuming, requiring 3-4 weeks for primer selection and analysis [5]. This approach also faces false-negative results due to clonal evolution during treatment. Similarly, qPCR for fusion gene transcripts has limited utility as over 50% of ALL cases lack detectable fusion genes tested standardly at diagnosis [5]. Even when detectable, quantification accuracy is affected by variability in RNA transcript numbers per leukemic cell [5]. These limitations collectively underscore the need for more comprehensive, efficient, and standardized diagnostic approaches capable of capturing the full genetic complexity of acute leukemias.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Diagnostic Methods in Acute Leukemia

| Method | Key Applications | Sensitivity | Turnaround Time | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytomorphology | Initial diagnosis, blast percentage quantification | ~5% (morphological) | 1-2 hours | Subjective interpretation, limited genetic information |

| Multiparameter Flow Cytometry | Immunophenotyping, MRD monitoring | 10⁻⁴ | 4-6 hours | Antigen shift during treatment, inter-laboratory variability |

| Cytogenetics/Karyotyping | Detection of chromosomal abnormalities | ~5% | 1-3 weeks | Requires cell culture, low resolution |

| PCR/qPCR | Specific mutation/fusion detection, MRD monitoring | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ | 1-3 days | Limited to known targets, primer design challenges |

Next-Generation Sequencing: Technical Advancements and Applications

NGS Methodologies and Workflows

Next-generation sequencing represents a transformative approach that enables massive parallel sequencing of DNA or RNA fragments, providing unprecedented resolution for genetic characterization of hematologic malignancies [19]. The NGS workflow encompasses multiple standardized steps, beginning with nucleic acid extraction from patient specimens (typically peripheral blood or bone marrow aspirates), followed by library preparation through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification [25]. Unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) may be incorporated during library preparation to distinguish true variants from PCR artifacts, enhancing detection accuracy [25]. Subsequent sequencing occurs on platforms such as Illumina MiSeq or NextSeq, generating millions to billions of short reads that are computationally aligned to reference genomes and analyzed through sophisticated bioinformatic pipelines for variant calling and annotation [25] [27].

The applications of NGS in leukemia diagnostics are diverse and can be tailored to specific clinical needs. Targeted gene panel sequencing represents the most widely implemented approach in clinical settings, focusing on curated sets of genes with established significance in leukemia pathogenesis, classification, or treatment [25]. These panels balance comprehensive coverage with practical considerations of cost, turnaround time, and data interpretation complexity. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) examines all protein-coding regions, while whole-genome sequencing (WGS) provides complete genomic coverage, including non-coding regions [25]. Whole-transcriptome sequencing (WTS) facilitates detection of fusion transcripts, expression profiling, and variant calling in transcribed regions [25]. Each approach offers distinct advantages, with targeted panels currently dominating routine clinical practice due to their cost-effectiveness and streamlined interpretation.

NGS Applications in Genetic Characterization

NGS has revolutionized our understanding of the molecular landscapes in both ALL and AML. In ALL, NGS panels frequently focus on sequencing immunoglobulin (IGH) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements to establish unique molecular fingerprints for each leukemic clone, enabling highly sensitive MRD monitoring [5]. Additionally, NGS detects recurrent genetic abnormalities with prognostic significance, including ETV6::RUNX1 fusions in pediatric ALL, IKZF1 deletions, and CRLF2 rearrangements [19]. The technology's comprehensive nature allows for simultaneous assessment of multiple genetic alterations, providing a more complete molecular profile than sequential single-gene testing.

In AML, NGS has been instrumental in characterizing the complex mutational architecture that underlies disease pathogenesis and heterogeneity. The PETHEMA cooperative group demonstrated the clinical utility of NGS through a nationwide diagnostic network that provided standardized sequencing studies for 2,668 adult AML patients [28]. Their approach utilizing a 30-gene consensus panel identified at least one mutation in 97% of patients, with distinct mutational patterns according to disease phase, age, and sex [28]. This comprehensive genetic profiling facilitated accurate diagnosis and reliable prognosis stratification according to genomic classification systems, validating the clinical value of NGS in routine AML management [28]. Importantly, NGS can identify novel molecular subgroups with clinical significance, such as mutated WT1 and mutations in multiple myelodysplasia-related genes, which are associated with adverse prognosis [28].

Comparative Performance: NGS Versus Traditional Methods

Sensitivity and Detection Capabilities

The enhanced sensitivity of NGS represents a significant advantage over conventional diagnostic methods, particularly for MRD assessment. In ALL, NGS demonstrates superior sensitivity in detecting MRD-positive cases compared to MFC. Studies have shown that NGS identifies a greater number of MRD-positive patients than MFC at the 0.01% threshold, with one analysis reporting NGS detection of 57.5% versus 26.9% positive cases in B-ALL and 80% versus 46.7% in T-ALL [5]. The concordance between NGS and MFC was notably higher for MRD-positive cases (97.2%) than for MRD-negative cases (57.1%), indicating that NGS reliably identifies additional patients with persistent disease that would be classified as MRD-negative by flow cytometry [5].

Similar advantages are observed in AML, where ultradeep NGS targeting specific mutations achieves sensitivities between 10⁻⁴ and 10⁻⁵, comparable to reference methodologies like qPCR [29]. The implementation of circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis by NGS further enhances monitoring capabilities, providing a minimally invasive approach for quantifying mutational burden with variant allele frequencies detectable as low as 0.08% [27]. This exceptional sensitivity enables earlier detection of residual disease than conventional chimerism analysis in post-transplant patients, with significant implications for relapse prediction and preemptive intervention [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MRD Detection Methods

| Parameter | Multiparameter Flow Cytometry | qPCR | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 10⁻⁴ | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ |

| Applicability | ~90-100% of cases | 40-50% (fusion genes) | >95% of cases |

| Turnaround Time | 4-6 hours | 1-3 days | 3-5 days |

| Key Advantages | Rapid, widely available | High sensitivity for known targets | Comprehensive, detects clonal evolution |

| Major Limitations | Antigen shift effects | Limited to known targets | Cost, bioinformatics complexity |

Clinical Utility and Prognostic Value

The prognostic value of NGS-based MRD assessment has been demonstrated across multiple studies in acute leukemias. In ALL, NGS-based MRD stratification correlates strongly with clinical outcomes, with patients achieving NGS-MRD negativity exhibiting superior event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) rates [5]. The technology has proven highly predictive of relapse following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and CAR-T cell therapy, providing critical information for post-treatment management [5]. The use of IGH rearrangements as primary markers in NGS panels has demonstrated particularly good prognostic value in B-ALL, establishing this approach as a robust method for risk stratification [5].

In AML, NGS of cfDNA has shown promising prognostic utility in patients following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Research has revealed that patients with donor chimerism ≥90% but mutation-positive cfDNA had a probability of progression-free survival of 64% at 17 months post-transplantation, compared to 100% in patients with undetectable MRD [27]. This finding indicates that NGS-based cfDNA analysis offers higher sensitivity for detecting residual leukemic cells than chimerism analysis alone and provides superior prognostic stratification [27]. The ability to simultaneously track multiple mutations through NGS also enables monitoring of clonal evolution during disease progression or treatment, capturing dynamic changes in the genetic landscape that may inform therapeutic resistance [19].

Experimental Approaches and Research Applications

Methodological Protocols for NGS-Based MRD Detection

The implementation of NGS for MRD monitoring requires standardized experimental protocols to ensure reproducible and clinically actionable results. For ALL, the EuroClonality-NGS study group has developed guidelines for Ig/TCR sequencing to establish clonality and track malignant clones [5]. The methodology begins with DNA extraction from bone marrow or peripheral blood samples obtained at diagnosis and during follow-up. For library preparation, multiplex PCR amplifies rearranged Ig/TCR genes using consensus primers targeting framework regions, incorporating sample-specific barcodes for multiplex sequencing [5]. Sequencing is typically performed on Illumina platforms to achieve high coverage (≥100,000 reads per sample), enabling detection of low-frequency clones. Bioinformatic analysis involves alignment to reference sequences, clonotype identification, and quantification of leukemia-derived sequences relative to total reads, with results reported as clonal cell frequencies [5].

For AML MRD detection, protocols often utilize targeted panels covering recurrently mutated genes. The approach described by [27] employs commercially available core myeloid panels (e.g., ArcherDx VariantPlex Core Myeloid panel spanning 37 genes) for cfDNA analysis. Cell-free DNA is isolated from blood collected in specialized stabilization tubes, with quality assessment through pre-sequencing QC assays [27]. Library preparation incorporates unique molecular identifiers to distinguish true low-frequency variants from sequencing artifacts. Ultra-deep sequencing (>100,000x coverage) enables sensitive variant detection down to 0.08% variant allele frequency [27]. Bioinformatics pipelines (e.g., Archer Analysis) with customized parameters (minimal depth=1, error-correction enabled) facilitate sensitive mutation calling, with manual review of mutations previously identified at diagnosis but filtered automatically [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for Leukemia Genomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NGS-Based Leukemia Characterization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Stabilization | Cell-free DNA BCT tubes (Streck) | Preserves cfDNA profile in blood samples | Prevents dilution from leukocyte lysis during transport |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA | Maintains fragment integrity for library preparation |

| Target Enrichment | VariantPlex Core AML/Myeloid panels (ArcherDx) | Targeted sequencing of leukemia-associated genes | Customizable content based on research objectives |

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep kits | NGS library construction with dual indices | Reduces index hopping with unique dual indexing |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, NextSeq | Massively parallel sequencing | Balance between throughput, read length, and cost |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Archer Analysis, ClinVar, COSMIC | Variant calling, annotation, and interpretation | Integration of clinical databases for pathogenicity assessment |

Signaling Pathways and Genetic Networks

The genetic landscape of acute leukemias involves complex interactions between multiple signaling pathways that regulate hematopoiesis, cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. In ALL, key pathways frequently disrupted include B-cell development (governed by PAX5, IKZF1, EBF1), tyrosine kinase signaling (activated by ABL1, JAK-STAT mutations), and tumor suppressor pathways (regulated by TP53, CDKN2A/B) [19]. These genetic alterations collectively promote uncontrolled expansion of lymphoid precursors while blocking differentiation, creating the characteristic phenotype of immature blast accumulation.

In AML, the molecular pathogenesis typically involves mutations in distinct functional categories: signaling molecules (FLT3, KIT, RAS), transcription factors (RUNX1, CEBPA), tumor suppressors (TP53, WT1), and epigenetic modifiers (DNMT3A, TET2, IDH1/2) [28] [25]. These mutations disrupt normal myeloid differentiation, enhance self-renewal capacity, and confer survival advantages to leukemic stem cells. The specific combination and order of acquisition of these mutations influence disease initiation, progression, and clinical behavior, highlighting the importance of comprehensive genetic profiling for understanding disease biology.

Integration into Clinical Practice and Future Directions

Current Implementation Challenges

Despite its transformative potential, the integration of NGS into routine leukemia diagnostics faces several significant challenges. Technical complexities include the need for specialized bioinformatics expertise, standardized protocols, and rigorous quality control measures to ensure reproducible results across laboratories [5] [25]. The PETHEMA cooperative group addressed these challenges through a nationwide network of reference laboratories implementing standardized NGS studies, complemented by regular cross-validation rounds to maintain quality [28]. This model demonstrates that standardization is achievable through coordinated efforts, though it requires substantial infrastructure investment.

Economic barriers also impact NGS implementation, with high costs associated with sequencing instrumentation, reagents, and computational resources [19]. Additionally, data interpretation complexities present ongoing challenges, as the distinction between pathogenic mutations and benign variants or variants of unknown significance requires sophisticated bioinformatic tools and curated databases [25]. The growing incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) in variant classification helps streamline this process by integrating publicly available information and predicting variant pathogenicity [25] [2]. However, these approaches still require validation and standardization before widespread clinical adoption.

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

The future trajectory of NGS in leukemia diagnostics points toward increasingly comprehensive and integrated approaches. The transition from targeted panels to whole-genome sequencing is anticipated within the next five years, driven by reduced sequencing costs and enhanced computational power [25]. This expansion will enable detection of novel genetic alterations beyond currently known targets, potentially revealing new therapeutic vulnerabilities and biomarkers. The integration of transcriptomic and epigenetic profiling with DNA sequencing will provide multidimensional insights into disease mechanisms, capturing the functional consequences of genetic alterations [25].

Liquid biopsy approaches using cfDNA represent another promising direction, offering minimally invasive disease monitoring that captures spatial heterogeneity and enables real-time tracking of clonal evolution [27]. As these technologies mature, their integration with conventional methods will likely create synergistic diagnostic workflows that leverage the respective strengths of each approach. For instance, combining MFC for rapid assessment with NGS for comprehensive genetic characterization may provide complementary advantages in MRD monitoring [5]. Ultimately, these advancements will support more dynamic and personalized treatment strategies, moving beyond static diagnostic classification toward adaptive therapeutic approaches that evolve with the changing genetic landscape of each patient's disease.

The diagnosis and risk stratification of acute leukemia have long relied on a combination of traditional diagnostic methodologies, including cytomorphology, cytogenetic analysis, and targeted molecular tests. While these approaches have formed the standard of care for decades, the rapidly evolving understanding of leukemia pathogenesis has revealed significant resolution gaps and diagnostic blind spots in conventional testing platforms. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into clinical practice represents a paradigm shift, offering an unbiased, comprehensive approach to genetic characterization that addresses many limitations of traditional methods. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of NGS against traditional diagnostic approaches within the context of acute leukemia research, providing experimental data and methodological details to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The limitations of traditional approaches are particularly evident in their inability to detect novel or rare genetic alterations, comprehensively assess structural variants, and identify minimal residual disease (MRD) at clinically relevant sensitivities. Furthermore, the sequential nature of traditional testing often results in prolonged turnaround times and insufficient tissue sampling, potentially delaying critical treatment decisions. This analysis systematically examines these limitations through direct comparison with NGS-based methodologies, focusing specifically on their application in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as a model system, with broader implications for other leukemia subtypes.

Methodological Comparison: Traditional versus NGS Approaches

Experimental Protocols in Traditional Diagnostic Methods

Traditional diagnosis of acute leukemia typically follows an integrated stepwise protocol known as the MICM framework, which incorporates Morphology, Immunophenotype, Cytogenetics, and Molecular abnormalities [2] [30]. The initial assessment involves peripheral blood tests, including complete blood count and morphological analysis of blood smears, to detect abnormalities in cell counts and morphology. This is followed by bone marrow aspiration and biopsy to evaluate blast cell percentage and cytomorphological features, with a diagnostic threshold of >20% blasts in bone marrow or peripheral blood according to World Health Organization (WHO) classification, though specific genetic abnormalities allow diagnosis even with lower blast percentages [30]. Flow cytometry immunophenotyping represents the third component, enabling detection of surface and cytoplasmic antigen expression patterns to assist in leukemia subtyping, typically using antibody panels against markers such as CD34, CD117, CD13, CD33, and lineage-specific antigens.

For cytogenetic analysis, conventional karyotyping requires G-banding metaphase analysis of cultured bone marrow cells, with a typical resolution limit of 5-10 Mb, thereby missing smaller structural variants [31]. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) employs fluorescently labeled DNA probes targeting known recurrent genetic rearrangements (e.g., PML::RARA, RUNX1::RUNX1T1) with higher resolution than karyotyping but limited to predefined targets. Targeted molecular testing typically uses polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods including quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) and fragment analysis for mutation detection in specific genes (e.g., FLT3-ITD, NPM1), with sensitivity generally limited to variants with >5% variant allele frequency (VAF) [31].

NGS-Based Methodological Frameworks

In contrast to traditional approaches, NGS methodologies offer comprehensive genetic profiling through several experimental frameworks. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) provides complete coverage of nuclear DNA, typically achieving 80-100x coverage for diagnostic applications, enabling detection of single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants (SVs) from a single assay [31]. Whole transcriptome sequencing (WTS) profiles the entire RNA content, allowing for detection of gene fusions, alternative splicing, and expression abnormalities, with particular utility for identifying cryptic rearrangements missed by conventional methods. Integrated WGS-WTS (iWGS-WTS) approaches combine genomic and transcriptomic data to provide a comprehensive molecular portrait, enhancing variant detection accuracy and biological interpretation [31].

Targeted NGS panels focus sequencing on clinically relevant genes using hybrid capture or amplicon-based approaches, achieving deeper coverage (500-1000x) suitable for detecting low-frequency mutations and MRD monitoring. For methylation profiling, methods like the MARLIN (Methylation- and AI-guided Rapid Leukemia Subtype Inference) tool utilize long-read nanopore sequencing technology to classify acute leukemia based on DNA methylation patterns, achieving results within two hours of biopsy receipt [32]. This approach has demonstrated capability to resolve diagnostic blind spots missed by conventional methods, such as identifying cryptic rearrangements involving the DUX4 gene and revealing novel predictive signatures like HOX-activated subgroups [32].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of Traditional and NGS-Based Diagnostic Approaches for Acute Leukemia. Traditional methods (yellow) are sequential and targeted, while NGS approaches (green) provide comprehensive genetic assessment. Key limitation and advantage differentiators are highlighted.

Resolution Gaps: Comparative Performance Data

Detection of Genetic Variants

Direct comparative studies demonstrate significant resolution gaps between traditional and NGS-based approaches across all variant classes. A systematic study from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital implementing integrated WGS-WTS in 153 pediatric AML patients revealed critical limitations in conventional testing approaches [31]. The iWGS-WTS approach identified 330 somatic pathogenic or likely pathogenic SNV/Indels in 135/153 patients, with high concordance between WGS and whole exome sequencing (WES) for variants with VAF ≥5% (~96% concordance rate) [31]. However, manual review identified nine additional variants not called by WES, predominantly complex indels, while 15 variants detected by WES with VAFs ranging from 5–12.5% did not meet established reporting criteria for iWGS-WTS, highlighting detection variability at lower VAFs.

For structural variant detection, WGS analysis identified 106 AML-associated oncogenic or likely oncogenic fusions in 105 cases, of which 96 were predicted to produce fusion oncogenes and 10 were suspected enhancer-hijacking structural alterations [31]. WTS analysis alone diagnosed 94/96 (98%) of the WGS-detected fusion oncogenes, with no false positive findings. Importantly, research from the University of Michigan demonstrated that adding RNA-based fusion testing to standard NGS panels identified gene fusions in 15% of over 600 AML patients, including approximately 4% (23 cases) where fusions were missed by conventional cytogenetics [33] [34]. These included clinically significant rearrangements involving NUP98 and KMT2A that directly influence treatment approaches.

For copy number variations, WGS revealed 42 pathogenic/likely pathogenic focal CNVs (<5 Mb) in 24 patients, including 15 alterations smaller than 50 kb (12 ≤ 10 kb) that presented as intragenic/exonic CNVs leading to truncation of functional proteins [31]. Among alterations smaller than 50 kb, recurrent findings included deletions in CBL affecting exons 8 and/or 9 and KMT2A partial tandem duplications, all of which were supported by WTS evidence. This resolution far exceeds the capability of conventional cytogenetics, which has a resolution limit of 5-10 Mb, unable to detect these clinically significant smaller alterations.

Minimal Residual Disease Monitoring

The limitations of traditional approaches are particularly pronounced in MRD monitoring, where sensitivity thresholds directly impact relapse prediction and treatment decisions. Traditional flow cytometry-based MRD detection typically achieves sensitivity of 0.01% (10^-4), while PCR-based methods can reach 0.001% (10^-5) for specific mutations [2]. In contrast, NGS-based approaches demonstrate significantly enhanced capabilities for MRD monitoring.

Researchers at Moffitt Cancer Center validated a highly sensitive NGS-based test for tracking FLT3 mutations in AML patients, demonstrating detection at extraordinarily low allelic fractions down to 0.0014% (1.4x10^-5) with strong accuracy and reproducibility [33] [34]. This enhanced sensitivity enables more confident assessment of remission status, better selection of patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and earlier intervention upon molecular relapse signals. Furthermore, a University of California San Diego study utilizing NGS to track cancer-related gene mutations in 74 AML patients at diagnosis, post-chemotherapy, and post-transplant found that lingering mutations after transplant strongly predicted relapse, particularly in epigenetic regulators such as TET2 and DNMT3A [33] [34]. This approach provided critical prognostic information not obtainable through conventional monitoring.

Table 1: Comparative Detection Rates of Genetic Alterations in Acute Leukemia

| Variant Type | Traditional Methods | Detection Rate | NGS-Based Methods | Detection Rate | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Fusions | Conventional Cytogenetics | ~70-80% [33] | RNA-seq + WGS | 98% of known fusions; +15% additional yield [31] [33] | Identifies cryptic drivers (e.g., NUP98, KMT2A) affecting treatment |

| SNVs/Indels | Targeted PCR/Panel | Limited to predefined targets | WGS/WES | ~96% concordance for VAF ≥5%; additional complex indels [31] | Comprehensive mutation profiling for risk stratification |

| Focal CNVs (<50 kb) | Cytogenetics (resolution limit 5-10 Mb) | Undetectable | WGS | 42 focal CNVs in 24 patients, including 15 <50 kb [31] | Detects clinically significant intragenic deletions (e.g., CBL, KMT2A-PTD) |

| FLT3-ITD | Fragment Analysis | 28 ITDs in 18 patients; 1 subclonal ITD missed [31] | WGS + WTS | 28 ITDs detected; 10 borderline cases with weak WGS evidence [31] | Improved detection of complex ITD patterns |

| MRD (FLT3 mutations) | qPCR (sensitivity ~0.001%) | Limited by predefined targets | Deep Sequencing | Sensitivity 0.0014% (14x10^-6) [33] [34] | Earlier relapse prediction and intervention |

Diagnostic Blind Spots: Unresolved Challenges in Traditional Approaches

Cryptic Genetic Events and Novel Alterations

Traditional diagnostic approaches exhibit several critical blind spots that impact accurate classification and risk stratification of acute leukemia. Cryptic genetic events represent a significant challenge, as conventional cytogenetics frequently misses subtle structural rearrangements that lack apparent chromosomal banding alterations. The MARLIN study demonstrated that methylation profiling combined with machine learning could identify diagnostic blind spots missed by conventional methods, successfully detecting cryptic rearrangements involving the DUX4 gene that are associated with favorable clinical outcomes [32]. Similarly, the University of Michigan study found that approximately 4% of AML patients harbored fusion events undetectable by standard cytogenetics [33] [34], highlighting a substantial diagnostic gap in conventional approaches.