Revolutionizing Neuropharmacology: Advances in 3D Bioprinted Blood-Brain Barrier Models for Drug Discovery

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) represents a major challenge in developing therapeutics for central nervous system diseases.

Revolutionizing Neuropharmacology: Advances in 3D Bioprinted Blood-Brain Barrier Models for Drug Discovery

Abstract

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) represents a major challenge in developing therapeutics for central nervous system diseases. This article explores the transformative role of three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting in creating physiologically relevant in vitro BBB models. We examine the foundational anatomy of the BBB, methodological advances in bioprinting techniques and bioink design, strategies for overcoming technical challenges in model fabrication, and validation frameworks for assessing model performance. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these engineered BBB constructs offer unprecedented opportunities to study neurodegenerative disease mechanisms, enhance drug permeability prediction, and accelerate CNS drug development with greater human relevance than traditional 2D cultures or animal models.

The Blood-Brain Barrier Blueprint: Anatomy, Function, and Modeling Imperatives

The neurovascular unit (NVU) represents a functional multicellular complex that is critical for maintaining the sophisticated microenvironment of the central nervous system (CNS). At its core lies the blood-brain barrier (BBB), a highly selective interface that not only protects the brain from potentially harmful substances in the blood but also regulates the transport of nutrients and essential molecules [1] [2]. The BBB's exceptional properties are not intrinsic to a single cell type but emerge from the continuous, dynamic interplay between brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), pericytes, and astrocytes [1] [3]. This tri-cellular relationship forms the fundamental biological basis for advanced in vitro modeling, particularly through 3D bioprinting technologies that seek to recapitulate human neurovascular physiology for drug development and disease modeling [4] [5].

The growing emphasis on developing physiologically relevant in vitro models stems from recognized limitations of traditional systems. While animal models have provided foundational knowledge, they cannot fully mimic the complexity of the human brain due to species-specific adaptations, including differences in gene expression patterns, lipid profiles, and the proportion and complexity of astrocytes [1]. Furthermore, conventional 2D in vitro models fail to replicate the crucial dimensionality, cell-ECM interactions, and mechanical cues present in the native neurovascular environment [4]. The integration of 3D bioprinting technologies addresses these limitations by enabling precise spatial organization of multiple cell types within biomimetic hydrogels, creating engineered tissue constructs with enhanced physiological relevance for studying BBB function and pathology [4] [5].

Core Cellular Components of the NVU

Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMECs)

BMECs constitute the primary physical barrier between the blood and brain parenchyma. Unlike peripheral endothelial cells, BMECs exhibit distinctive morphological, structural, and functional characteristics that underlie their barrier properties [1] [2]. These include continuous, complex tight junctions (TJs) that significantly limit paracellular flux, an absence of fenestrations, minimal pinocytic activity, and expression of specialized transport mechanisms [1]. The TJs are molecularly unique structures composed of various proteins including claudins, occludins, junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), and accessory proteins that collectively form the "physical barrier" of the BBB [1] [2].

BMECs also express specific enzymes and transporters that facilitate efficient nutrient transport into the CNS while actively effluxing toxic metabolites [1]. These functional capabilities are not autonomously established but depend on continuous signaling interactions with neighboring pericytes and astrocytes [1] [3]. The BMECs' strategic position allows them to serve as the interface for molecular exchange between the vascular system and neural tissue, making them the primary determinant of BBB selectivity and a critical component in 3D bioprinted BBB models [4] [5].

Pericytes

Pericytes are mural cells embedded within the basement membrane that intimately surround the brain microvascular endothelium. These cells play multifaceted roles in BBB development, maintenance, and regulation [2] [3]. Through the secretion of signaling factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta, pericytes dynamically regulate endothelial tight junction integrity and permeability [2]. They are also involved in critical vascular processes including angiogenesis, vascular maturation, and regulation of cerebral blood flow [2] [3].

Experimental evidence from 3D human BBB-on-chip models demonstrates that pericytes contribute significantly to neuroinflammatory responses. When stimulated with inflammatory triggers like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), the presence of pericytes results in distinct secretion profiles for cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) [3]. This highlights the active role of pericytes in neuroimmune regulation beyond their structural support functions. In 3D bioprinting applications, incorporating pericytes is essential for establishing proper barrier function and replicating the cellular crosstalk that maintains BBB integrity [4] [6].

Astrocytes

Astrocytes, the most abundant glial cells in the CNS, extend numerous end-feet processes that extensively cover the abluminal surface of brain capillaries. These end-feet formations create an almost continuous envelope around the microvasculature, facilitating bidirectional communication between vascular and neural compartments [1] [2]. Astrocytes promote endothelial cell differentiation and enhance tight junction stability through the release of soluble factors including brain-derived neurotrophic factor [2]. They also indirectly regulate nutrient transport efficiency by sensing and responding to metabolic demands within the brain parenchyma [2].

Human brains possess a higher proportion and complexity of neocortical astrocytes compared to rodent brains, underscoring the importance of human-cell-based models for translational research [1]. Astrocytes exhibit numerous receptors involved in innate immunity and, when activated, secrete soluble factors mediating both innate and adaptive immune responses [3]. In engineered 3D BBB models, the inclusion of astrocytes is crucial for replicating the neurovascular interface, as they provide essential cues for BMEC differentiation and barrier function while contributing to the neuroinflammatory responses observed in pathological conditions [3] [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Characteristics of Human Brain Microvasculature and Cellular Components

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total microvessel length | ~600 km | Extensive surface area for blood-brain exchange [7] |

| Microvessel density | ~500 m/cm³ | High vascularization meets metabolic demands [7] |

| Neuron density scaling | ∝ V⁻¹⁄⁶ | Inverse relationship with brain volume across species [7] |

| Capillary diameter | 7-10 μm | Smaller than peripheral capillaries [7] |

| Intercapillary distance | ~40 μm | Ensures oxygen diffusion to all neurons [7] |

| Neuron-to-capillary distance | 10-20 μm | Optimized for nutrient/waste exchange [7] |

Cell-Cell Signaling and Functional Integration

The functional integrity of the BBB emerges from sophisticated cell-cell signaling between BMECs, pericytes, and astrocytes. This signaling occurs through both direct contact and paracrine mechanisms, creating a dynamic regulatory network that maintains CNS homeostasis [3] [6]. Several evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways have been identified as crucial for BBB development and function, including Wnt/β-catenin, retinoic acid, and sonic hedgehog pathways [6]. Recent research has revealed that the endothelial transmembrane receptor Unc5B and its ligand netrin-1 regulate BBB integrity by maintaining Wnt/β-catenin signaling [6].

In neuroinflammatory conditions, the distinct contributions of each cell type become particularly evident. When exposed to inflammatory triggers such as TNF-α, the cellular components of the NVU respond with cell-type-specific cytokine secretion patterns [3]. Studies using 3D human BBB-on-chip models have demonstrated that the presence of astrocytes or pericytes significantly influences the secretion profiles of G-CSF and IL-6, with response levels significantly greater than those observed in static Transwell co-culture systems [3]. This highlights the importance of physiologically relevant models for studying neurovascular inflammation and cell-type-specific contributions to disease processes.

Diagram 1: NVU signaling and inflammation response pathways.

3D Bioprinting Strategies for NVU Modeling

3D bioprinting has emerged as a powerful biofabrication technology for creating sophisticated in vitro models of the NVU that better replicate the human brain's cellular composition, microenvironment, and architecture [1] [4]. Unlike traditional 2D models or self-assembled organoids, 3D bioprinting offers precise control over tissue architecture and matrix properties while maintaining good cell viability [4]. This precision is particularly valuable for modeling complex structures like the NVU, where the spatial arrangement of different cell types directly influences functionality [4] [5].

The fundamental approach to bioprinting NVU models involves depositing cell-laden hydrogels (bioinks) in predefined patterns to recreate the hierarchical structure of brain tissue [1] [4]. These biofabrication strategies can be categorized based on whether cellular components are seeded onto constructs after device fabrication or encapsulated in biomaterials during the fabrication process [4]. The cell-encapsulating approach enables superior control over cell number and positioning, resulting in better reproducibility, and allows cells to encounter ECM cues from all directions, resembling their physiological state [4]. Common bioprinting modalities include extrusion-based, inkjet, and stereolithographic systems, each with distinct advantages for specific aspects of NVU modeling [4].

Advanced 3D-bioprinted BBB models incorporate multiple cell types (BMECs, pericytes, and astrocytes) within a vascular-like architecture, often using collagen gels or other biomimetic hydrogels as the supporting matrix [3]. These models can better replicate the cylindrical geometry of brain microvessels and incorporate relevant mechanical cues compared to rigid ECM substrates used in conventional models [3]. The ability to create reproducible, personalized models makes 3D bioprinting especially suitable for modeling diseases with high interpatient heterogeneity, such as glioblastoma [4].

Table 2: Advanced 3D Bioprinting Models of the NVU/BBB

| Model Type | Key Features | Advantages | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D BBB-on-a-chip | Cylindrical collagen gel with hollow lumen; Primary human BMECs, pericytes, astrocytes | Permits analysis of individual cell type contributions; Enhanced neuroinflammatory responses | [3] |

| 3D-bioprinted GBM/BBB | Patient-derived cells; Controlled spatial organization in hydrogels | Reproducible, personalized models for high heterogeneity diseases | [4] |

| Microfluidic BBB models | Integration of fluid flow and shear stress; Real-time permeability monitoring | Dynamic conditions better mimic physiology; Suitable for drug transport studies | [8] [9] |

Experimental Protocols for NVU Modeling

3D Human BBB-on-Chip Fabrication

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a microengineered 3D model of the human BBB within a microfluidic chip, adapted from Herland et al. [3]. The model recapitulates key features of the neurovascular unit, including a cylindrical vascular structure, relevant cellular components, and physiological flow conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMVECs)

- Primary human brain pericytes

- Primary human astrocytes

- Collagen type I solution

- Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)

- Microfluidic channel molds (1 mm width × 1 mm height × 20 mm length)

- CSC complete medium

- Astrocyte medium

- Attachment factor

Procedure:

Microfluidic Device Fabrication:

- Produce microfluidic devices using soft lithography with PDMS.

- Pour degassed 10:1 base:crosslinking PDMS mix onto the mold.

- Crosslink at 80°C for 18 hours.

- Punch inlets and outlets of 1.5 mm diameter in the molded PDMS.

- Bond the device to a 100 μm layer of spin-coated PDMS using oxygen plasma treatment (50 W for 20 seconds).

- Bake at 80°C for 18 hours to strengthen bonding.

Collagen Gel Preparation and Loading:

- Prepare collagen solution according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Inject collagen solution into the microfluidic channel and allow polymerization at 37°C.

- Create a central hollow lumen within the collagen gel using a needle or similar implement.

Cell Seeding and Culture:

- Culture hBMVECs on the inner surface of the collagen gel lumen.

- For co-culture models, seed primary human brain pericytes beneath the endothelium or primary human brain astrocytes within the surrounding collagen gel.

- Initiate medium flow through the lumen after cell attachment.

- Maintain cells with appropriate media (CSC complete medium for hBMVECs and pericytes, Astrocyte medium for astrocytes).

- Culture for 5-7 days to establish mature barrier function before experimentation.

Barrier Function Assessment:

- Measure transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) using microelectrodes.

- Perform permeability assays with fluorescent tracers (e.g., FITC-dextran).

- Assess tight junction localization via immunostaining for ZO-1, occludin, and claudin-5.

Inflammatory Stimulation and Cytokine Analysis

This protocol describes the methodology for evaluating neuroinflammatory responses in 3D BBB models, enabling the identification of distinct contributions from astrocytes and pericytes [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Recombinant human TNF-α

- Cell culture media appropriate for the BBB model

- Multiplex cytokine assay kits (e.g., for G-CSF, IL-6)

- Collection tubes for conditioned media

Procedure:

Inflammatory Stimulation:

- Replace culture media with fresh media containing TNF-α (recommended starting concentration: 10-100 ng/mL).

- Include control conditions without TNF-α stimulation.

- Incubate for 6-24 hours depending on experimental objectives.

Conditioned Media Collection:

- Collect conditioned media from each experimental condition at designated time points.

- Centrifuge media to remove cellular debris (1000 × g, 10 minutes).

- Aliquot and store supernatants at -80°C until analysis.

Cytokine Measurement:

- Quantify cytokine levels (G-CSF, IL-6) using multiplex bead-based immunoassays or ELISA according to manufacturer protocols.

- Normalize cytokine concentrations to total protein content or cell number.

- Compare secretion profiles between different cellular configurations (endothelium alone, endothelium with pericytes, endothelium with astrocytes).

Data Analysis:

- Perform statistical analysis to identify significant differences in cytokine secretion between conditions.

- Relate cytokine profiles to barrier function measurements from parallel experiments.

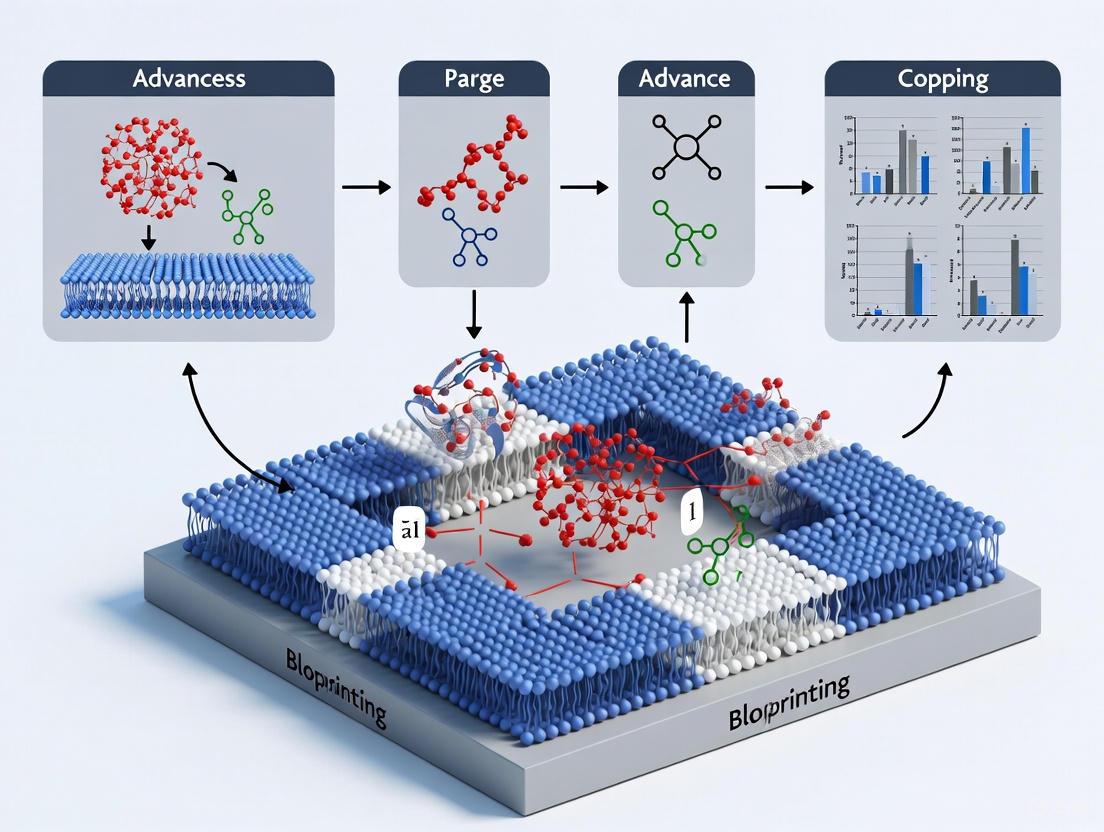

Diagram 2: 3D BBB model fabrication and analysis workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for 3D NVU Modeling

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Human BMVECs | Core barrier-forming endothelial cells | Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMVECs) from cortical origin [3] |

| Primary Human Pericytes | Vascular support and barrier regulation | Human brain pericytes from cortical origin [3] |

| Primary Human Astrocytes | Glial support and barrier induction | Human astrocytes of cortical origin [3] |

| Collagen Type I | Natural hydrogel for 3D matrix support | Cylindrical collagen gel containing central hollow lumen [3] |

| PDMS | Microfluidic device fabrication | Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane [3] |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory stimulus for barrier challenge | Recombinant human TNF-α for neuroinflammatory studies [3] |

| Cytokine Assays | Quantification of inflammatory responses | Multiplex assays for G-CSF, IL-6 measurement [3] |

The cellular architecture of the neurovascular unit, comprising BMECs, pericytes, and astrocytes, represents a highly integrated system whose functionality emerges from sophisticated intercellular crosstalk. Understanding this tri-cellular relationship is fundamental to advancing 3D bioprinting technologies for creating physiologically relevant BBB models. These advanced models demonstrate superior performance in recapitulating human neurovascular physiology, particularly in complex processes such as neuroinflammation where the distinct contributions of individual cell types become evident [3].

The continued refinement of 3D-bioprinted NVU models holds significant promise for transforming neuroscience research and drug development. By incorporating patient-derived cells and controlling spatial organization within biomimetic hydrogels, these models offer unprecedented opportunities for studying disease mechanisms, screening neurotherapeutics, and developing personalized medicine approaches for neurological disorders [4] [5]. As bioprinting technologies evolve to better replicate the dynamic mechanical and biochemical microenvironment of the native neurovascular unit, they will increasingly bridge the gap between conventional in vitro models and in vivo physiology, accelerating the development of effective therapies for CNS disorders.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective, dynamic interface that separates the central nervous system (CNS) from the systemic circulation, maintaining the precise microenvironment required for neural function and protecting the brain from blood-borne pathogens and toxins [10] [11]. This barrier function primarily resides at the level of the endothelial cells lining cerebral microvessels, which are uniquely characterized by robust, continuous tight junctions that eliminate the paracellular space between adjacent cells [12] [11]. These junctional complexes are more than just physical seals; they are dynamic structures that regulate paracellular permeability, help maintain cellular polarity, and contribute to signaling pathways that control proliferation and differentiation [12].

The integrity of the BBB is critically dependent on the molecular composition of tight junctions, whose key transmembrane proteins include occludin, claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs) [12] [13]. These proteins are connected to the actin cytoskeleton via intracellular scaffold proteins, such as zonula occludens (ZO)-1 and ZO-2, forming a supramolecular complex that is essential for barrier properties [12] [14]. Dysregulation of these proteins is a hallmark of BBB breakdown in numerous neurological conditions, including ischemic stroke, multiple sclerosis, and neurodegenerative diseases, and also presents a major challenge for the delivery of therapeutics to the CNS [15] [14] [11].

Recent advances in 3D bioprinting are revolutionizing the study of these proteins by enabling the creation of sophisticated, physiologically relevant human BBB models [16] [10] [13]. These in vitro platforms incorporate multiple cell types, perfusable flow, and customized extracellular matrices, providing unprecedented opportunities to investigate tight junction biology, model neurological diseases, and screen for drugs designed to modulate barrier permeability [16] [13]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical review of the core tight junction proteins—occludin, claudins, and JAMs—and details their critical role in barrier integrity within the context of modern 3D bioprinting research.

Structural and Functional Anatomy of Tight Junctions

The Supramolecular Complex of the Tight Junction

Tight junctions (TJs) form an apical belt-like network of protein strands between neighboring endothelial and epithelial cells, creating the primary seal that limits the paracellular diffusion of solutes, ions, and cells [12]. Ultrastructurally, these strands appear in freeze-fracture electron micrographs as closely spaced particles with a diameter of approximately 10 nm [12]. The TJ is not a simple static seal but a dynamic, multi-protein complex composed of transmembrane proteins, cytoplasmic plaque proteins, and their links to the cytoskeleton.

The figure below illustrates the organization of this supramolecular complex and its critical role in maintaining the blood-brain barrier.

- Transmembrane Proteins: The core sealing function is provided by the claudin family, which polymerizes to form the primary paracellular seal [12]. Occludin contributes to the regulation of solute diffusion and TJ dynamics, while JAMs are involved in the initial establishment of cell-cell contacts and leukocyte transmigration [12] [13].

- Scaffold Proteins and Cytoskeletal Linkage: Intracellularly, the zonula occludens (ZO) proteins, particularly ZO-1 and ZO-2, serve as critical plaque proteins [12] [14]. They contain multiple protein-binding domains, including PDZ domains, which allow them to simultaneously bind the cytoplasmic tails of claudins, occludin, and JAMs, and connect the entire complex to the actin cytoskeleton [12]. This linkage is vital for both the structural stability of the TJ and its ability to rapidly respond to extracellular and intracellular signals.

Core Tight Junction Proteins: Composition and Properties

The functional properties of the TJ are determined by the specific composition and stoichiometry of its transmembrane proteins. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the major TJ protein families.

Table 1: Core Tight Junction Transmembrane Proteins

| Protein Family | Key Members at BBB | Gene (Human) | Molecular Weight | Primary Function | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claudins [12] [11] | Claudin-5, -3, -1 | CLDN5 (Chr. 22) | 20-29 kDa | Primary seal formation; determines paracellular charge and size selectivity [12]. | - 4 transmembrane domains- Two extracellular loops (ECL1 & ECL2)- N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic tails- PDZ-binding motif on C-terminus [11]. |

| Occludin [12] [14] | Occludin | OCLN | ~65 kDa | Regulates paracellular diffusion and TJ stability; signaling functions [14]. | - 4 transmembrane domains- Two extracellular loops- C-terminal cytoplasmic tail binds ZO proteins. |

| JAMs [12] [13] | JAM-A (JAM-1) | F11R | ~32 kDa | Cell adhesion; leukocyte transmigration; early TJ assembly [13]. | - Single transmembrane domain- Two extracellular Ig-like domains- PDZ-binding motif on C-terminus. |

In-Depth Analysis of Key Tight Junction Proteins

Claudins: The Architects of Paracellular Selectivity

The claudin family, with its 27 known members, forms the backbone of tight junction strands and is the principal determinant of paracellular permeability properties [12] [17]. These ~20-29 kDa proteins contain four transmembrane domains, two extracellular loops (ECL1 and ECL2), and intracellular N- and C-terminal tails. The first extracellular loop (ECL1) is particularly critical for the barrier function, containing a consensus sequence with two cysteine residues that form a disulfide bridge, which is essential for the sealing function [12] [11]. The second extracellular loop (ECL2) is involved in strand formation via trans-interactions between claudins on adjacent cells [11]. Most claudins possess a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif that facilitates interaction with scaffold proteins like ZO-1 [12].

Claudin-5 is the most abundant and best-studied claudin at the BBB. Its mRNA levels are approximately 600 times higher than those of other claudins found at the barrier, such as claudin-1, -3, and -12 [11]. It is often termed the "gatekeeper" of the BBB, and its deletion in mouse models leads to a selective increase in permeability to small molecules (<800 Da) while the barrier remains intact against larger molecules [11]. Its expression is regulated by signals from other cells in the neurovascular unit, notably Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) secreted from astrocytes [11].

Other claudins present at the BBB include claudin-3, which also contributes to barrier tightness, and claudin-1 [13] [11]. The specific combination and density of different claudin types determine the overall permeability and ion selectivity of the paracellular pathway.

Table 2: Functional Roles of Selected Claudin Family Members

| Claudin | Primary Tissue/Barrier Expression | Paracellular Function | Relevance to BBB & Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Claudin-5 [12] [11] | Brain endothelial cells (BBB) | Forms a tight seal against small molecules [11]. | Critical for BBB integrity; downregulation implicated in stroke, MS, and psychiatric disorders [11]. |

| Claudin-1 [12] [17] | Skin, liver, BBB | Maintains tight junction integrity. | Downregulation increases BBB permeability and may facilitate tumor cell invasion [17]. |

| Claudin-3 [13] [11] | Brain endothelial cells, epithelia | Contributes to tight junction formation. | Expressed at the BBB; role in barrier function is an active area of research [13]. |

| Claudin-11 [12] | Oligodendrocytes, Sertoli cells | Forms electrical seal in myelin; blood-testis barrier. | Not a BBB component, but critical for CNS insulation. |

Occludin: A Key Regulatory Protein

Occludin was the first transmembrane protein identified in TJs. While not essential for the initial formation of TJ strands, it plays a crucial modulatory role in barrier function. In vitro studies have long suggested its importance in regulating paracellular diffusion of solutes and TJ stability [14].

Recent in vivo evidence using occludin-deficient mice subjected to ischemic stroke has solidified its critical role. These mice exhibited:

- Continuously impaired neurological function compared to wild-type mice.

- Increased BBB permeability in both acute and chronic phases after stroke, as measured by leakage of Evans blue and fluorescent tracers.

- Larger infarct volumes and higher post-stroke mortality.

- Reduced expression of claudin-5 and ZO-1, suggesting occludin is necessary for maintaining the full expression of other key TJ components [14].

This study demonstrates that occludin plays a vital role in the pathophysiology of stroke, modulating BBB integrity and long-term neurological outcome.

Junctional Adhesion Molecules (JAMs): Multifunctional Adhesion Proteins

JAMs are immunoglobulin superfamily proteins that localize to tight junctions and are involved in a diverse set of functions. They contribute to the early stages of TJ assembly by promoting homophilic trans-interactions between adjacent endothelial cells [12] [13]. Beyond their structural role, JAMs are critically involved in regulating the transmigration of leukocytes across the endothelium during inflammatory responses [12]. For example, JAM-1 is essential for BBB integrity and is implicated in the inflammatory processes of diseases like multiple sclerosis [13].

Tight Junction Dysfunction in Neurological Pathologies

Dysregulation of tight junction proteins is a common pathogenic mechanism in a wide array of neurological disorders, leading to BBB breakdown and subsequent neuronal damage.

- Ischemic Stroke: Following cerebral ischemia, a biphasic opening of the BBB occurs, with permeability peaks at 3h and 72h after reperfusion [15]. This correlates with a significant decrease in the mRNA and protein expression of claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1, as well as a redistribution of these proteins away from the cell borders [15] [14]. The protein kinase C delta (PKCδ) pathway has been implicated in this TJ disruption [15].

- Neurodegenerative Diseases (NDDs): BBB dysfunction is an early hallmark of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) [10] [13]. In AD, impaired clearance of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and disruption of TJ proteins contribute to disease progression [13]. Similarly, in PD, BBB breakdown may allow entry of neurotoxins and inflammatory mediators that exacerbate the pathology linked to misfolded alpha-synuclein [13].

- Neuroinflammation (e.g., Multiple Sclerosis): In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model for MS, 3D imaging reveals a heterogeneous and fragmented loss of claudin-5 staining, particularly in venules, which are the primary sites of leukocyte extravasation [18]. This focal disruption of TJs is a key step in allowing immune cells to invade the CNS.

- Brain Metastases: Tumor cells from cancers such as lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma must breach the BBB to form metastatic lesions in the brain. They achieve this by altering the expression of TJ proteins, particularly claudin-5, thereby increasing BBB permeability and facilitating their transmigration [19] [17].

3D Bioprinting for Advanced BBB Modeling

Two-dimensional (2D) Transwell cultures have been the workhorse of in vitro BBB modeling but fail to recapitulate the spatial geometry, fluid shear stress, and complex cell-cell interactions of the native neurovascular unit [16] [10]. 3D bioprinting has emerged as a powerful technology to overcome these limitations by creating customizable, physiologically relevant human BBB models.

Key Design Considerations for 3D Bioprinted BBB Models

To create a mini-BBB that accurately mimics in vivo function, several key parameters must be addressed:

- Cellular Composition: The model must incorporate the three key cell types of the neurovascular unit: brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), pericytes, and astrocytes [10] [13]. The inclusion of all three enhances TJ formation and barrier tightness.

- Perfusable Flow and Shear Stress: Incorporating dynamic flow is critical to apply physiological shear stress (5–23 dyn/cm²), which influences endothelial cell alignment, morphology, and upregulation of TJ proteins [13].

- Physiological Parameters: The model should strive to replicate in vivo metrics, including capillary-like diameters of 7–10 μm and trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values ranging from 1,500 to 8,000 Ω·cm² [13].

Experimental Workflow for 3D Bioprinting a Human BBB Model

The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for creating and validating a 3D bioprinted BBB model, integrating key steps from recent research.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Bioprinting a Vascularized BBB Model for TBI Research

Based on a study by Galpayage Dona et al. (2021) that used a CELLINK LUMEN X DLP bioprinter, the following protocol can be adapted to model Tight Junction disruption in Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) [16].

Objective: To create a 3D vascularized BBB model and subject it to a stretch injury (TBI model) to study subsequent TJ disruption and barrier dysfunction.

Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for 3D BBB Bioprinting

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| PEGDA PhotoInk [16] | Synthetic hydrogel polymer; provides structural integrity and tunable mechanical properties. | CELLINK (Note: Specific product lines updated) |

| GelMA PhotoInk [16] | Methacrylated gelatin; provides natural cell-adhesion motifs within the hydrogel matrix. | CELLINK (Note: Specific product lines updated) |

| Primary Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (HBMECs) [16] | The core cell type forming the barrier; primary cells are preferred for physiological relevance. | Commercial cell vendors |

| DL-based 3D Bioprinter [16] | High-resolution printer for crosslinking photosensitive bioinks into complex 3D microfluidic scaffolds. | e.g., CELLINK LUMEN X |

| Perfusion System [16] | Mimics blood flow; provides shear stress critical for endothelial cell function and TJ formation. | Custom or commercial microfluidic systems |

| Antibodies for Immunostaining [18] | For visualizing and quantifying TJ proteins (e.g., anti-Claudin-5, anti-Occludin, anti-ZO-1). | Multiple commercial suppliers |

Methodology:

- Bioink Preparation and Bioprinting: Prepare a combination of PEGDA and GelMA PhotoInks. Using the DLP bioprinter, fabricate a 3D cube containing a network of microchannels with diameters ranging from 100 to 300 microns, based on a pre-designed CAD file [16].

- Cell Seeding and Culture: On day 1 post-printing, seed primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) into the lumens of the bioprinted scaffold. Allow the cells to adhere and form a confluent, endothelialized monolayer over 5-7 days of culture [16].

- Barrier Maturation and Validation: Connect the endothelialized scaffold to a perfusion apparatus to introduce physiological flow. Validate barrier integrity at day 7 by measuring the permeability to fluorescent tracers (e.g., dextran) that should be blocked by an intact BBB, and/or by immunostaining for claudin-5 and occludin to confirm proper TJ formation [16].

- TBI Induction via Stretch Injury: On day 7, apply a controlled tensile strain to the 3D model using a stretching device to simulate a traumatic brain injury [16].

- Post-Injury Analysis:

- Permeability Assay: Post-injury, re-perfuse with dextran to quantify any increase in permeability, indicating BBB dysfunction.

- TJ Protein Analysis: Fix the model at various time points post-injury and perform immunofluorescence staining for claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1. Use 3D imaging and analysis software to quantify changes in protein expression, density, and localization [18].

Quantitative Analysis of TJ Proteins in 3D Models

Advanced 3D imaging and quantification techniques are essential for accurately assessing TJ integrity in complex models. A study by Paul et al. (2013) demonstrated a method for 3D contour-based segmentation of spinal cord microvessels to quantify junctional claudin-5 density [18]. The workflow involves:

- Acquiring confocal z-stacks of thick (e.g., 60µm) tissue sections or 3D models immunostained for claudin-5 and a vascular marker (e.g., Laminin).

- Using software (e.g., Imaris) to create an individual contour for each confocal z-slice by tracing the vessel of interest.

- Merging the individual contours into a single 3D contour surface, which is used to isolate the microvessel and estimate its surface area.

- Creating an isosurface for the claudin-5 signal within the contoured volume to calculate the number of voxels and their intensity, providing a measure of claudin-5 density [18].

This approach allows researchers to move beyond qualitative assessments and obtain precise, quantitative data on TJ protein expression in specific vascular segments under normal and pathological conditions.

The tight junction proteins occludin, claudins, and JAMs form a sophisticated complex that is fundamental to the integrity and function of the blood-brain barrier. A deep understanding of their structure, interactions, and regulation is crucial for elucidating the pathogenesis of a wide spectrum of neurological diseases and for developing strategies to enhance drug delivery to the CNS. The advent of 3D bioprinting technology marks a significant leap forward, providing researchers with powerful, human-relevant models to study these proteins in a physiologically authentic context. These advanced in vitro systems enable the dissection of molecular mechanisms underlying TJ disruption in disease, the screening of therapeutics designed to restore barrier function, and the generation of personalized models for precision medicine. As bioprinting resolution, bioink fidelity, and functional validation continue to improve, these 3D-bioprinted BBB models are poised to become an indispensable tool in translational neuroscience research.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective, multi-component interface that rigorously controls molecular exchange between the bloodstream and the central nervous system (CNS). This dynamic barrier is formed by brain capillary endothelial cells (BCECs) whose maturation and function depend on intricate interactions with astrocytes, pericytes, and neurons, collectively forming the neurovascular unit (NVU) [20] [10]. The BBB's primary function is to maintain brain homeostasis by protecting neural tissue from neurotoxic plasma components, blood cells, and pathogens while ensuring optimal neuronal function [13]. For researchers developing CNS therapeutics, the BBB presents a formidable delivery challenge, as it selectively restricts the passage of most pharmaceutical agents [20] [21].

Understanding the specialized transport mechanisms that govern molecular transit across the BBB is crucial for advancing neurological drug development. These pathways can be broadly categorized into three principal systems: solute carriers (SLCs) for facilitated transport of small molecules, receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) for macromolecule delivery, and ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux pumps that actively exclude xenobiotics [20] [22] [23]. The emergence of sophisticated 3D bioprinted BBB models now provides unprecedented opportunities to study these transport mechanisms in physiologically relevant human systems, offering insights that could accelerate the development of CNS-targeted therapies [13] [24].

Solute Carrier (SLC) Transport Systems

Solute carriers represent a large superfamily of membrane transport proteins that facilitate the movement of essential nutrients, ions, and metabolites across the BBB. These transporters are crucial for maintaining the nutritional and metabolic balance required for proper brain function. The SLC superfamily includes 244 genes expressed in brain microvessels, encompassing transporters for glucose (slc2a1), lactate (slc16a1), cationic amino acids (slc7a1), and neutral amino acids (slc7a5) [25].

Mechanism and Classification of SLC Transporters

SLC transporters primarily operate through facilitated diffusion or secondary active transport mechanisms. Facilitated diffusion involves the passive movement of substrates down their concentration gradients without energy expenditure, while secondary active transport couples substrate movement to ion gradients (typically Na+) to drive accumulation against concentration gradients [22] [25]. These transporters can be further categorized based on their membrane polarization within brain endothelial cells, with distinct transporters strategically localized to either the luminal (blood-facing) or abluminal (brain-facing) membranes to enable vectorial transport of substrates [25].

A key feature of many SLC transporters is their exchange mechanism, where the influx of one substrate is coupled to the efflux of another. For instance, the large neutral amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5) facilitates the uptake of essential amino acids into the brain in exchange for intracellular glutamine [25]. This antiport system enables the brain to acquire dietary essential amino acids that cannot be synthesized internally while simultaneously eliminating potentially neurotoxic metabolites.

Major SLC Transporter Families at the BBB

Table 1: Key SLC Transporters at the Blood-Brain Barrier

| Transporter Family | Representative Members | Substrates | Transport Mechanism | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Transporters | LAT1 (SLC7A5/SLC3A2) | Large neutral AAs (phenylalanine, leucine) | Facilitated diffusion (antiport) | Luminal & abluminal |

| CAT1 (SLC7A1) | Cationic AAs (arginine, lysine) | Facilitated diffusion | Primarily luminal | |

| EAAT1-3 (SLC1A1-3) | Acidic AAs (glutamate, aspartate) | Na+-dependent symport | Primarily abluminal | |

| Carbohydrate Transporters | GLUT1 (SLC2A1) | Glucose, galactose | Facilitated diffusion | Luminal & abluminal |

| Monocarboxylate Transporters | MCT1 (SLC16A1) | Lactate, pyruvate, ketone bodies | H+-coupled symport | Luminal & abluminal |

| Organic Anion/Cation Transporters | OATP1A2 (SLCO1A2) | Organic anions, steroids | Na+-independent exchange | Luminal |

| OCTN2 (SLC22A5) | Carnitine, organic cations | Na+-dependent symport | Luminal |

The amino acid transporters represent one of the most diverse and critical SLC groups at the BBB. The concentration of amino acids in brain extracellular fluid is approximately tenfold lower than in plasma, with glutamine being the exception [25]. This gradient is tightly regulated by polarized AA transporters distributed across both membranes of endothelial cells. For example, sodium-independent transporters (Systems L and y+) are located on both luminal and abluminal membranes and mediate bidirectional AA transport, while sodium-dependent transporters (Systems A, ASC, N, and X-AG) are predominantly located on the abluminal membrane and actively pump AAs from brain to blood [25].

The glucose transporter GLUT1 (SLC2A1) is particularly abundant at the BBB and is responsible for supplying glucose to meet the brain's high metabolic demands. GLUT1 facilitates the bidirectional transport of glucose down its concentration gradient, with expression levels approximately three times higher on the abluminal side compared to the luminal side, potentially reflecting the brain's priority for glucose uptake over export [10].

Diagram 1: SLC-mediated amino acid transport across the BBB. Sodium-independent transporters (red) facilitate bidirectional exchange, while sodium-dependent transporters (blue) actively clear neurotoxic metabolites from the brain.

Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis (RMT)

Receptor-mediated transcytosis is a vesicular transport pathway that enables the selective movement of macromolecules across the BBB. This process represents a promising route for delivering therapeutic biologics, including proteins, antibodies, and nanoparticle drug carriers, to the CNS [21] [26]. RMT begins with the specific binding of a ligand to its cognate receptor on the luminal surface of brain endothelial cells, triggering clathrin-coated pit formation, followed by endocytosis, vesicular trafficking through various intracellular compartments, and eventual exocytosis at the abluminal membrane [21].

Key RMT Receptors at the BBB

Several receptors have been identified as mediators of transcytosis at the BBB, each with distinct expression patterns, ligand specificities, and transport capacities. A comprehensive transcriptomics study comparing RMT receptor expression in mouse and human brain microvessels revealed significant species differences that must be considered when translating preclinical findings [26].

Table 2: Major RMT Receptors at the Blood-Brain Barrier

| Receptor | Primary Ligands | Species Expression Pattern | Relative Abundance | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transferrin Receptor (TfR) | Transferrin, iron | Higher in mouse vs. human BMV | High in both species | Historical "prototypical" target for RMT |

| Insulin Receptor (INSR) | Insulin | Enriched in human BMV vs. brain and lung | Moderate | Clinical trials for antibody-mediated delivery |

| Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Receptor (IGF1R) | IGF-1 | Enriched in mouse BMV vs. periphery | Moderate | Potential target for antibody shuttles |

| Low-density Lipoprotein Receptor (LDLR) | ApoE, ApoB | Similar expression across tissues | High | Angiopep-2 platform (LRP1 ligand) |

| LRP1 | Multiple ligands | Similar expression across tissues | High | Angiopep-2 platform in clinical trials |

| LRP8 | ApoE, thrombospondin | Enriched in mouse BMV vs. periphery | Low | Potential specialized transport |

| Leptin Receptor (LEPR) | Leptin | Not enriched in BMV | Moderate | Natural transport system for leptin |

The transferrin receptor (TfR) has served as the prototype RMT receptor for decades and has been extensively exploited for brain delivery of therapeutic antibodies and nanoparticles [26]. However, recent studies have revealed challenges with TfR-targeting approaches, including fast systemic clearance, on-target toxicity against TfR-rich reticulocytes, and limited transport efficiency in primates [26]. These limitations have prompted the exploration of alternative RMT receptors.

The insulin receptor (INSR) has emerged as a promising target for RMT-mediated brain delivery, particularly in humans where it shows enrichment in brain microvessels compared to both brain parenchyma and peripheral tissues like lung [26]. This expression profile is ideal for therapeutic targeting, as it may enable extended systemic half-life, reduced peripheral toxicity, and efficient brain delivery. Anti-human INSR antibodies are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for CNS drug delivery [26].

RMT Mechanisms and Intracellular Trafficking

The RMT process involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of intracellular events. After ligand binding, the receptor-ligand complex is internalized via clathrin-coated vesicles, which subsequently lose their clathrin coat and acidify to form early endosomes [21]. The acidic environment of the compartment of uncoupling receptor and ligand (CURL) promotes dissociation of the ligand from the receptor, allowing the receptor to recycle back to the plasma membrane while the ligand proceeds through the transcytotic pathway [22] [21].

The intracellular fate of RMT cargo is influenced by multiple factors, including receptor affinity, binding site occupancy, and the specific signaling pathways activated upon receptor engagement. Some receptors, like TfR, undergo constitutive recycling regardless of ligand occupancy, while others may require specific activation or display regulated trafficking patterns [26]. Understanding these subtleties is crucial for engineering effective RMT-based delivery systems that can successfully navigate the complex intracellular environment of brain endothelial cells.

ABC Efflux Pumps

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters constitute a major defense mechanism at the BBB that actively restricts the brain penetration of xenobiotics and contributes to multidrug resistance in neurological disorders and brain cancers [20] [23]. These primary active transporters utilize energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to pump substrates against their concentration gradients, effectively limiting their accumulation in the CNS.

Major ABC Transporters at the BBB

The ABC superfamily encompasses 48 distinct transporters categorized into seven families (ABCA-ABCG), with several members playing critical roles in BBB function [20]. The most extensively studied and clinically relevant ABC transporter at the BBB is P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1), a 170 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that recognizes an extraordinarily diverse array of structurally unrelated compounds [20] [23].

Table 3: ABC Efflux Transporters at the Blood-Brain Barrier

| Transporter | Gene | Substrates | Localization | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-glycoprotein | ABCB1 (MDR1) | Diverse chemotherapeutic agents, opioids, HIV protease inhibitors | Luminal membrane | Major determinant of CNS drug penetration; contributes to pharmacoresistance in epilepsy and brain tumors |

| Breast Cancer Resistance Protein | ABCG2 (BCRP) | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, flavinoids, statins | Luminal membrane | Limits brain penetration of chemotherapeutics; works synergistically with P-gp |

| Multidrug Resistance Proteins | ABCC1 (MRP1) | Conjugated metabolites, antivirals, antibiotics | Luminal & abluminal membranes | Contributes to drug resistance in epilepsy; effluxes β-amyloid peptides |

| ABCC2 (MRP2) | Glucuronide and glutathione conjugates | Luminal membrane | Upregulated in refractory epilepsy | |

| ABCC4 (MRP4) | Nucleoside analogs, oseltamivir | Luminal membrane | Limits CNS penetration of antiviral drugs |

P-gp is strategically localized primarily on the luminal membrane of brain capillary endothelial cells, where it efficiently extrudes substrates back into the bloodstream, preventing their CNS entry [23]. Immunogold cytochemistry studies have revealed that P-gp density is approximately 1.4-fold higher at the abluminal compared to the luminal membrane, suggesting a potential additional role in directing substances toward brain interstitial fluid [23]. The functional importance of P-gp is dramatically illustrated in mdr1a/mdr1b knockout mice, which display significantly increased brain penetration of P-gp substrates like ivermectin, resulting in neurotoxicity at normally subtherapeutic doses [23].

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) often works synergistically with P-gp, exhibiting overlapping substrate specificities and creating a formidable cooperative barrier function [23]. The multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs/ABCC) transport a diverse array of organic anions, including drug conjugates (e.g., glucuronide, glutathione) and various anticancer and antiviral agents [20]. MRP4 is particularly notable for its role in limiting the brain penetration of oseltamivir, the active metabolite of the influenza drug Tamiflu [20].

Regulation and Inhibition of ABC Transporters

The expression and function of ABC transporters are influenced by various factors, including inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, and drug interactions. Several pharmacological inhibitors have been developed to block ABC transporter function, including verapamil, cyclosporine A, and valspodar for P-gp [23]. However, clinical trials combining these inhibitors with CNS drugs have largely failed due to dose-limiting toxicities resulting from simultaneously increased penetration into non-CNS tissues, where P-gp also serves protective functions [23].

More recent strategies have focused on developing specific and potent third-generation inhibitors like tariquidar and elacridar, which show improved efficacy and safety profiles [23]. Alternatively, rather than systemic inhibition, some approaches aim to temporarily disrupt BBB efflux transport through localized delivery or prodrug designs that bypass recognition by ABC transporters altogether.

3D Bioprinted BBB Models for Transport Studies

Advanced in vitro BBB models created through 3D bioprinting technologies represent a transformative approach for studying transport mechanisms and screening CNS drug candidates. These models overcome critical limitations of traditional 2D systems and animal models by recapitulating the multicellular architecture, dynamic flow conditions, and cell-matrix interactions of the human NVU [13] [24].

Key Design Considerations for 3D Bioprinted BBB Models

Physiologically relevant BBB models must incorporate several critical design elements to accurately mimic in vivo barrier function and transport properties. The inclusion of all three key BBB cell types—brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs), astrocytes, and pericytes—is essential for achieving appropriate tight junction formation and barrier tightness [13]. Cellular composition can be derived from various sources, including primary cells, immortalized cell lines, and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), with iPSCs showing particular promise for generating patient-specific models [13].

The incorporation of dynamic, perfusable flow is another critical factor, as physiological shear stress (typically 5-23 dyn/cm² in human brain capillaries) significantly influences endothelial cell alignment, morphology, and tight junction protein expression [13]. Furthermore, 3D-bioprinted models must replicate key physical parameters of brain capillaries, including diameters of 7-10 μm and trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values ranging from 1,500 to 8,000 Ω·cm² to match in vivo measurements [13].

Experimental Protocols for Transport Studies in 3D-Bioprinted BBB

Model Fabrication Using Digital Light Processing (DLP): Recent advances in DLP-based bioprinting enable the creation of complex, perfusable vascular networks with tunable topology and selective functionalization with bioactive peptides [24]. The protocol typically involves:

- Preparing a photocrosslinkable bioink containing gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) and polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)

- Functionalizing with specific peptide motifs (RGD, IKVAV, HAVDI) to mediate endothelial cell attachment and coverage

- Printing the 3D channel architecture using DLP with precise spatial control

- Seeding endothelial cells into the luminal channels and astrocytes in the surrounding hydrogel

- Establishing physiological flow conditions using perfusion systems [24]

Barrier Integrity Assessment: TEER measurement remains the gold standard for evaluating barrier integrity in 3D-bioprinted models. Advanced systems incorporate real-time TEER monitoring electrodes directly within the perfusion chips to enable continuous assessment without disrupting the culture environment [13]. Additionally, the localization and expression of tight junction proteins (ZO-1, occludin, claudin-5) are routinely evaluated using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy [24].

Permeability and Transport Studies: The permeability of test compounds across 3D-bioprinted BBB models is typically quantified using fluorescent or radiolabeled tracers with known permeability profiles. The apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) is calculated using the formula: Papp = (dQ/dt)/(A × C₀), where dQ/dt is the transport rate, A is the surface area, and C₀ is the initial concentration [13]. Specific transport pathways can be characterized using inhibitors of particular mechanisms: phloretin for GLUT1, AMD3100 for CXCR4-mediated transport, and Ko143 for BCRP efflux [10].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for 3D-bioprinted BBB model development and transport studies, highlighting key validation and application stages.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for BBB Transport Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Photocrosslinkable Bioinks | 3D scaffold fabrication | GelMA (5-15% w/v), PEGDA, peptide-functionalized hydrogels |

| Bioactive Peptides | Functionalization of hydrogels | RGD (cell adhesion), IKVAV (neurite outgrowth), HAVDI (cell-cell adhesion) |

| Primary Cells/iPSCs | BBB cellular components | Brain microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes, pericytes |

| TEER Measurement System | Barrier integrity assessment | Epithelial voltohmmeter, integrated electrodes |

| Tight Junction Markers | Immunofluorescence validation | Anti-ZO-1, anti-claudin-5, anti-occludin antibodies |

| Transport Inhibitors | Mechanistic transport studies | Phloretin (GLUT1), Ko143 (BCRP), Verapamil (P-gp) |

| Permeability Tracers | Barrier function assessment | Sodium fluorescein (376 Da), Dextran (4-70 kDa) |

| Cytokine Cocktails | Disease modeling | TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β for neuroinflammation studies |

The sophisticated transport systems of the BBB—solute carriers, receptor-mediated transcytosis, and ABC efflux pumps—collectively maintain CNS homeostasis while presenting formidable challenges for therapeutic delivery. Advances in 3D bioprinting have revolutionized our ability to model these transport mechanisms in physiologically relevant human systems, enabling more predictive screening of CNS drug candidates and investigation of disease-specific barrier alterations. These technologies allow researchers to dissect the complex interplay between transport pathways while maintaining the multicellular architecture and hemodynamic forces critical to BBB function. As 3D bioprinting methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to accelerate the development of novel strategies for overcoming the BBB and treating neurological disorders with enhanced precision and efficacy.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective, dynamic interface that separates the circulating blood from the central nervous system (CNS), playing a dual role in protecting the brain from potentially toxic substances while regulating the transport of essential nutrients and metabolites [27] [28]. This sophisticated biological barrier is composed of brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) interconnected by tight junctions (TJs), which are supported by pericytes, astrocytes, and the basement membrane in a specialized structure known as the neurovascular unit (NVU) [27] [29]. The BBB's impeccable barrier function, characterized by transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values reaching 1500-8000 Ω·cm² in humans, presents a formidable challenge for drug delivery to the CNS, with more than 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly 100% of large-molecule therapeutics failing to cross this protective interface [27] [30]. Understanding and modeling the BBB is therefore crucial for developing treatments for the increasing burden of CNS disorders, which represent one of the leading causes of global disability and mortality [29].

The pursuit of effective CNS therapies has been hampered by the limitations of traditional models used in preclinical research. For decades, scientists have relied primarily on two-dimensional (2D) in vitro cultures and animal models to study BBB function and screen potential therapeutics. However, these conventional approaches often fail to recapitulate the structural complexity and physiological functions of the human BBB, leading to unreliable predictions of drug efficacy and safety in humans [28] [29]. This review comprehensively examines the technical and physiological shortcomings of these traditional models within the context of advancing 3D bioprinting technologies for BBB modeling, highlighting how emerging biofabrication strategies offer promising solutions to overcome these limitations.

Fundamental Shortcomings of Two-Dimensional (2D) In Vitro Models

Structural and Physiological Limitations

Two-dimensional monolayer cultures, particularly the widely used Transwell system, represent the most basic approach to modeling the BBB in vitro. In this setup, endothelial cells are cultured on porous membranes, sometimes in co-culture with other NVU cells placed in the lower chamber. While these models offer simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and scalability for high-throughput screening, they suffer from significant limitations in replicating the physiological BBB environment [13] [28].

The most notable shortcoming of 2D models is their inability to mimic the cylindrical geometry of human brain capillaries, which typically range from 7-10 μm in diameter in the human brain [31]. This geometrical disparity profoundly affects cell morphology, polarity, and cell-cell interactions. In vivo, BMECs experience curvature that influences their behavior, with human BMECs resisting elongation and alignment in response to curvature—a potential evolutionary adaptation to reduce paracellular transport [31]. In flat 2D cultures, this natural curvature is absent, resulting in abnormal cell spreading and functionality.

Furthermore, 2D static models fail to incorporate hemodynamic forces, particularly the shear stress generated by blood flow. In human brain capillaries, endothelial cells experience wall shear stress ranging from 20-40 dyne/cm² in capillaries to 1-4 dyne/cm² in post-capillary venules [31]. This mechanical stimulation is crucial for maintaining BBB integrity, as it regulates the expression of tight junction proteins and transporters. The absence of these critical biomechanical cues in 2D models results in aberrant gene expression, reduced junctional tightness, and altered transporter activity compared to the in vivo BBB [13].

Simplified Cellular Microenvironment and Junctionality

The oversimplified cellular composition of most 2D models represents another significant limitation. While the BBB functions as a multicellular system, basic Transwell models typically utilize only endothelial cells, neglecting essential interactions with pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons that are critical for barrier induction and maintenance [27] [13]. Even when implemented in co-culture systems, the spatial organization of these supporting cells does not recapitulate their natural anatomical positions relative to the endothelial cells.

This simplified microenvironment leads to deficient tight junction formation and functionality. While 2D models develop some junctional complexity, their TJ networks are structurally and functionally inferior to those in the physiological BBB. The TEER values achieved in 2D models rarely exceed 1000 Ω·cm², significantly lower than the 1500-8000 Ω·cm² measured in humans [31]. Similarly, the expression of key tight junction proteins like claudin-5, occludin, and ZO-1 is often reduced or improperly localized in 2D cultures compared to the in vivo setting [27].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key BBB Parameters Between 2D Models and Human In Vivo Conditions

| Parameter | 2D In Vitro Models | Human In Vivo BBB |

|---|---|---|

| TEER (Ω·cm²) | Typically 130-857 [27], rarely >1000 | 1500-8000 [31] |

| Vessel Geometry | Flat monolayer | Cylindrical, 7-10 μm diameter capillaries [31] |

| Shear Stress | Absent (static) or non-physiological (flow systems) | 20-40 dyne/cm² (capillaries) [31] |

| Cellular Interactions | Limited contact in co-culture | Direct physical contact in neurovascular unit |

| TJ Protein Expression | Reduced claudin-5, occludin expression | Fully developed junctional complexes |

| Efflux Transporter Activity | Often diminished or aberrant | Fully functional P-gp, BCRP, MRP-1 |

The functional expression of transporters is also compromised in 2D models. Critical efflux transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) often exhibit altered expression levels and activity compared to in vivo conditions [27]. This transporter dysfunction significantly impacts drug permeability assessments, potentially leading to false positives in CNS drug screening campaigns. Additionally, receptor-mediated transcytosis systems—increasingly exploited for therapeutic delivery—are frequently inadequately represented in simplified 2D systems [28].

Critical Species Differences and Translational Limitations of Animal Models

Molecular and Functional Disparities

Animal models have long been considered the gold standard for preclinical BBB and CNS drug development studies. However, significant species differences between animal models and humans profoundly limit their predictive value and translational potential. These interspecies variations manifest at multiple levels, from molecular expression patterns to functional barrier properties.

Critical differences exist in the expression and functionality of transport systems at the BBB. For instance, Jamieson et al. reported that humans have 1.85-fold higher expression of BCRP and 2.33-fold lower expression of P-glycoprotein compared to mice [27]. Such divergence in key efflux transporters can dramatically alter the brain penetration profiles of their substrate drugs, leading to misleading predictions about human pharmacokinetics. Similarly, species differences in the expression of tight junction proteins and receptors further complicate the extrapolation of animal data to human clinical settings [27] [29].

The variability in transporter expression profiles across species significantly impacts drug development. A comparative analysis of membrane transporter proteins revealed substantial differences between humans and common preclinical species like rats, mice, and non-human primates [32]. These molecular disparities contribute to the high failure rate of CNS drugs in clinical trials, as compounds that show promising penetration in animal models may exhibit completely different distribution characteristics in humans due to differences in transporter affinity, density, or activity.

Inadequate Disease Modeling and Technical Limitations

Animal models frequently fail to recapitulate human pathophysiology of neurological disorders. The complex, multifactorial nature of conditions like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and glioblastoma involves intricate interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and aging processes that are challenging to model accurately in animals [33] [30]. Additionally, many neurological disorders exhibit species-specific manifestations that further limit the translational relevance of animal studies.

From a technical perspective, animal models present challenges for real-time monitoring and mechanistic studies. The complex physiology of living animals and difficulties in experimental procedures limit the ability to perform detailed, real-time measurements of analyte distribution and barrier function [29]. While advanced imaging techniques have been developed to study BBB dysfunction in animal models, the translation of these methods into clinical applications remains slow [34].

Table 2: Limitations of Animal Models in BBB Research and Drug Development

| Limitation Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Differences | 1.85-fold higher BCRP in humans vs. mice [27]; Different TJ protein expression patterns | Altered drug permeability predictions; Poor translation to human responses |

| Functional Variations | Differences in efflux transporter activity; Species-specific metabolic pathways | Misleading pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data |

| Disease Modeling | Inability to fully recapitulate human neurodegenerative diseases; Species-specific pathophysiology | Limited understanding of disease mechanisms; Poor predictive value for therapeutic efficacy |

| Technical Challenges | Difficult real-time monitoring; Complex surgical procedures; Ethical constraints | Limited mechanistic insights; Reduced experimental throughput |

| Resource Considerations | High costs; Time-consuming protocols; Specialized facilities required | Limited accessibility; Reduced scalability for screening |

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of the limitations of animal models comes from clinical translation statistics. Reports indicate that more than 80% of drugs shown to be effective in animal models eventually fail in human clinical trials [29]. This staggering attrition rate underscores the critical need for more human-relevant models that can better predict therapeutic outcomes in patients.

The Promise of 3D Bioprinting for Next-Generation BBB Modeling

In response to the limitations of traditional models, researchers have developed increasingly sophisticated three-dimensional (3D) in vitro models that better recapitulate the structural and functional complexity of the human BBB. Among these advanced approaches, 3D bioprinting has emerged as a particularly promising technology for creating physiologically relevant BBB models [13] [33].

3D bioprinting enables the precise spatial organization of multiple cell types within a biomimetic extracellular matrix, allowing for the creation of complex tissue architectures that closely resemble the native neurovascular unit. This capability addresses a fundamental limitation of 2D models by permitting the appropriate 3D arrangement of endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes relative to one another [13] [30]. Furthermore, 3D bioprinting facilitates the incorporation of perfusable vascular networks that can be subjected to physiological shear stress, thereby restoring this critical biomechanical cue missing from traditional static cultures [16].

The technology also enables the creation of patient-specific models through the use of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). These patient-derived cells can be differentiated into the various cellular components of the NVU, providing a powerful platform for studying personalized therapeutic responses and disease-specific BBB pathologies [32] [30]. This approach is particularly valuable for neurodegenerative disease research, where BBB dysfunction is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor to disease pathogenesis [13] [30].

Diagram 1: Evolutionary progression from traditional models to 3D bioprinted BBB platforms, highlighting key advantages of the bioprinting approach.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced BBB Modeling

The development of physiologically relevant 3D BBB models requires specialized materials and reagents to replicate the native brain microenvironment. The table below outlines key components used in advanced BBB model systems, particularly 3D bioprinting approaches.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 3D Bioprinted BBB Models

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinks | PEGDA, GelMA, Hyaluronic acid, Fibrin | Provide tunable 3D microenvironment with appropriate mechanical properties (2-4 kPa) matching brain tissue [30] [16] |

| Cellular Components | hiPSC-derived BMECs, Pericytes, Astrocytes, Neural stem cells | Enable species-matched, patient-specific modeling of neurovascular unit [13] [32] |

| Basement Membrane Proteins | Collagen IV, Laminin, Fibronectin, Heparan sulfate proteoglycans | Recreate native basement membrane composition for proper cell-matrix interactions [31] |

| Perfusion Systems | Microfluidic chips, Tubing networks, Peristaltic pumps | Introduce physiological shear stress (5-23 dyne/cm²) and nutrient delivery [13] [31] |

| Characterization Tools | TEER measurement electrodes, Tracer molecules (dextran), Confocal microscopy | Assess barrier integrity, permeability, and 3D structure non-invasively [16] [31] |

The limitations of traditional 2D cultures and animal models in BBB research are substantial and multifaceted. Two-dimensional models fail to recapitulate the structural complexity, physiological shear stress, and proper cellular interactions of the native neurovascular unit, while animal models are hampered by significant species differences that limit their translational predictive value. These shortcomings have contributed to the high failure rate of CNS therapeutics in clinical development, highlighting the critical need for more human-relevant models.

Advanced 3D bioprinting technologies represent a promising paradigm shift in BBB modeling, offering unprecedented capabilities to create physiologically relevant human-specific platforms with appropriate geometry, mechanical cues, and multicellular complexity. By addressing the fundamental limitations of traditional approaches, 3D bioprinted BBB models have the potential to accelerate CNS drug discovery, improve translational predictability, and advance our understanding of BBB function in health and disease. As these biofabrication technologies continue to evolve, they are poised to become indispensable tools in the quest to develop effective therapies for neurological disorders.

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) represents a critical frontier in the understanding and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs). This complex multicellular structure, once viewed primarily as a static protective shield, is now recognized as a dynamically impaired interface in conditions like Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD). BBB dysfunction is not merely a secondary consequence but may constitute an early pathogenic event that initiates and amplifies neurodegenerative processes [35] [36]. The growing burden of NDDs on global healthcare systems, with approximately 15% of the global population affected, has intensified research focus on the BBB as both a contributor to disease pathology and a potential therapeutic target [13] [37]. Current data reveals that BBB breakdown can significantly impact neuronal and synaptic function, influencing neurodegenerative processes through multiple interconnected mechanisms including impaired clearance of toxic metabolites, neuroinflammation, and disrupted cerebral homeostasis [35] [36].

The clinical imperative to understand BBB dysfunction stems from its dual role in NDDs: its pathological contribution to disease progression and its formidable obstruction to CNS-targeted therapies. With over 98% of small-molecule drugs and nearly 100% of large-molecule therapeutics failing to cross the BBB, developing strategies to either protect BBB integrity or leverage its transport mechanisms represents one of the most significant challenges in modern neurology and drug development [2]. This review examines the cellular and molecular underpinnings of BBB dysfunction in neurodegeneration, explores advanced 3D bioprinting approaches for modeling these pathological changes, and discusses emerging therapeutic strategies targeting the BBB in NDDs.

Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of BBB Dysfunction

Structural and Functional Components of the Neurovascular Unit

The BBB functions as a highly specialized vascular interface primarily formed by brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) that exhibit unique properties distinguishing them from peripheral endothelial cells. These BMECs are characterized by continuous tight junctions (TJs), minimal transcytosis rates, and expression of specialized transport systems that collectively maintain CNS homeostasis [13] [36]. The TJs comprise transmembrane proteins including occludin, claudins (particularly claudin-3 and claudin-5), and junctional adhesion molecules (JAMs), which are linked to the actin cytoskeleton via cytoplasmic scaffolding proteins such as ZO-1 [13]. These junctional complexes create a high-resistance barrier with transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values ranging from 1,500 to 8,000 Ω·cm² in physiological conditions [13].

Beyond the endothelial layer, the BBB incorporates other critical cellular components within the neurovascular unit (NVU). Pericytes are embedded within the vascular basement membrane and play essential roles in regulating BBB permeability, stabilizing vascular structure, and coordinating clearance of toxic metabolites [10] [36]. Astrocytes extend end-feet processes that envelop cerebral microvessels, contributing to BBB integrity through the release of trophic factors and regulation of water and ion homeostasis via aquaporin-4 channels [10]. The basement membrane, composed of collagen IV, laminin, nidogen, and other glycoproteins, provides structural support and biochemical cues that influence BBB cellular behavior [13] [10].

Table 1: Cellular Components of the Neurovascular Unit and Their Functions

| Cell Type | Location | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells (BMECs) | Lumen of cerebral capillaries | Form tight junctions; express transport systems; regulate molecular passage |

| Pericytes | Embedded in vascular basement membrane | Regulate permeability; stabilize vasculature; clear toxins; coordinate immune response |

| Astrocytes | Parenchymal side with end-feet enveloping vessels | Release trophic factors; regulate water/ion homeostasis; modulate blood flow |

| Neurons | Adjacent to neurovascular unit | Regulate cerebral blood flow via neurovascular coupling |

Transport Mechanisms Across the BBB

The BBB regulates molecular transit through multiple specialized transport pathways that become compromised in neurodegenerative states. Paracellular transport of polar solutes is severely restricted under physiological conditions by TJ complexes but may become aberrantly permeable in NDDs due to junctional protein disruption [10]. Transcellular transport mechanisms include: (1) carrier-mediated transport (CMT) of essential nutrients such as glucose (via GLUT1) and amino acids (via LAT1); (2) receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) of larger molecules including transferrin and lipoproteins; (3) adsorptive-mediated transcytosis (AMT) utilizing charge interactions; and (4) active efflux transport via ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters like P-glycoprotein (P-gp) that expel neurotoxins and therapeutic drugs [10] [36] [2]. The proper functioning of these transport systems is crucial for brain health, as they ensure adequate nutrient delivery while preventing accumulation of toxic metabolites.

Pathological Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Diseases

BBB dysfunction manifests across multiple NDDs through shared and distinct pathological mechanisms. In Alzheimer's disease, BBB impairment involves impaired clearance of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, partly due to reduced expression of efflux transporters at the BBB [13] [36]. The lipoprotein receptor LRP1, which normally mediates Aβ clearance from brain to blood, shows decreased expression, while the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), which facilitates Aβ influx into the brain, demonstrates increased expression [10] [36]. This imbalance promotes Aβ accumulation and contributes to neurovascular uncoupling, ultimately leading to regional cerebral blood flow deficits [36].

In Parkinson's disease, BBB dysfunction permits increased entry of neurotoxicants from the circulation and reduces clearance of accumulated α-synuclein aggregates [13]. Neuroinflammatory signaling induces TJ disruption through pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, which downregulate claudin-5 and occludin expression [13] [38]. Additionally, ABC transporter dysfunction may limit the efflux of α-synuclein, further promoting its accumulation [13].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular mechanisms of BBB dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases:

Diagram 1: Molecular mechanisms of BBB dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Neurodegenerative processes trigger multiple BBB dysfunction mechanisms including tight junction disassembly, neuroinflammation, cerebral blood flow disruption, transport system dysfunction, and pericyte degeneration. These mechanisms collectively contribute to pathological consequences such as amyloid-β accumulation, α-synuclein aggregation, oxidative stress, and immune cell infiltration.