RFE vs. Correlation-Based Feature Selection: A Practical Guide for Molecular Data Analysis in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and correlation-based feature selection methods for high-dimensional molecular data.

RFE vs. Correlation-Based Feature Selection: A Practical Guide for Molecular Data Analysis in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and correlation-based feature selection methods for high-dimensional molecular data. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, practical applications, and optimization strategies for both techniques. Drawing on recent research across cancer genomics, transcriptomics, and clinical diagnostics, the guide offers actionable insights for selecting the optimal feature selection approach to improve biomarker discovery, enhance classification accuracy, and ensure robust model performance in biomedical research.

Understanding Feature Selection: Core Concepts and Challenges in Molecular Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes high-dimensional omics data so problematic for standard machine learning models?

High-dimensional omics data, where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of samples, poses several critical problems. This situation, often called the "curse of dimensionality," leads to long computation times, increased risk of model overfitting, and decreased model performance as algorithms can be misled by irrelevant input features [1] [2]. Furthermore, models with too many features become difficult to interpret, which is a significant hurdle in scientific domains where understanding the underlying biology is essential [3].

Q2: How does feature selection differ from dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA?

Feature selection and dimensionality reduction are both used to simplify data but achieve this in fundamentally different ways. Feature selection chooses a subset of the original features (e.g., selecting 50 informative genes from 30,000), thereby preserving the original meaning and interpretability of the features [4] [5]. In contrast, dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) transforms the original features into a new, smaller set of features (components) that are linear combinations of the originals. This process makes the results harder to interpret in the context of the original biological variables [4] [3].

Q3: My model is overfitting on my transcriptomics data. How can feature selection help?

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise and spurious correlations in the training data instead of the underlying pattern. Feature selection directly combats this by removing irrelevant and redundant features [3]. By focusing the model on a smaller set of features that are truly related to the target variable (e.g., cell type or disease status), the model becomes less complex and less likely to overfit, leading to better performance on new, unseen data [2] [3].

Q4: When should I choose Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) over a simpler correlation-based filter method?

The choice depends on your goal and the nature of your data. Correlation-based filter methods (e.g., selecting top features by Pearson correlation) are computationally fast and simple but evaluate each feature independently. They may miss complex interactions between features [6].

RFE is a more sophisticated wrapper method that considers feature interactions by recursively building models and removing the weakest features. It is often more effective for complex datasets where features are interdependent but is computationally more expensive [6] [2]. If interpretability and speed are paramount, a correlation filter may suffice. If maximizing predictive accuracy and capturing feature interactions is key, RFE is often the better choice.

Q5: What are the best practices for implementing RFE in Python for an omics dataset?

Best practices for using RFE include [6] [2]:

- Use a Pipeline: Always integrate RFE and your final model within a scikit-learn

Pipelineto avoid data leakage during cross-validation. - Tune the Number of Features: Do not guess the optimal number of features. Use

RFECV(RFE with cross-validation) to automatically find the best number. - Choose an Appropriate Estimator: Select a base estimator that provides feature importance scores (e.g., LinearSVC, Random Forests).

- Scale Your Data: If using a model sensitive to feature scales (like SVMs), ensure your data is standardized before applying RFE.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Classification Accuracy After Feature Selection

Problem: After applying feature selection, your model's accuracy is low or worse than using all features.

Solution Steps:

- Re-evaluate the Feature Selection Method: The chosen method or its parameters might be unsuitable. Try a different algorithm (e.g., switch from a univariate filter to RFE) or adjust key parameters like the number of features to select [5] [3].

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that feature selection was performed within each fold of the cross-validation loop, not on the entire dataset before splitting. Using a

Pipelineis crucial to prevent this [2]. - Verify the Estimator in RFE: If using RFE, the choice of estimator (e.g., SVM, Decision Tree) can significantly impact which features are selected. Experiment with different estimators to see if results improve [7] [2].

- Inspect the Selected Features: Perform a sanity check on the selected features. Do they include genes or proteins known from literature to be biologically relevant to your condition?

Issue 2: Inconsistent Feature Selection Across Different Datasets

Problem: When analyzing data from multiple sources (e.g., different labs or experimental protocols), the most significant features selected vary greatly between datasets [4].

Solution Steps:

- Account for Batch Effects: The significance of individual features can differ from source to source due to technical variation (batch effects). Apply appropriate batch effect correction methods before feature selection [4].

- Use a Source-Specific Selection Strategy: As proposed in research on single-cell transcriptomics, perform feature selection separately for each data source based on their intrinsic correlations, and then combine the results into a unified feature set for final modeling [4].

- Employ Robust Algorithms: Consider using feature selection algorithms designed to handle multi-source or multi-omics data that can account for these variations inherently [5].

Comparative Analysis: RFE vs. Correlation-Based Selection

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two prominent feature selection methods.

Table 1: Comparison between Recursive Feature Elimination and Correlation-based Feature Selection.

| Aspect | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Correlation-Based Filter |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Iteratively removes the least important features based on model weights/importance [7] [6]. | Ranks features by their individual correlation with the target variable (e.g., Pearson, Mutual Information) [4] [8]. |

| Method Category | Wrapper Method [2] [3] | Filter Method [3] |

| Key Advantage | Considers feature interactions; often leads to higher predictive accuracy [6]. | Very fast and computationally efficient; simple to implement and interpret [3]. |

| Main Disadvantage | Computationally intensive; risk of overfitting to the model [6] [3]. | Ignores dependencies between features; may select redundant features [6]. |

| Interpretability | Good (retains original features) [7]. | Excellent (straightforward statistical measure) [4]. |

| Best Suited For | Complex datasets where feature interactions are suspected; when model accuracy is the primary goal [2]. | Large-scale initial screening; high-dimensional datasets where speed is critical [4] [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

Application: Selecting a robust, non-redundant feature subset for classification/regression on omics data.

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Clean, normalize, and scale the dataset (

X). - Initialize RFE: Use

sklearn.feature_selection.RFEorRFECV. - Fit the Selector: Fit the RFE object on the training data (

X_train,y_train). Crucially, this should be done inside a cross-validation loop or pipeline. - Model Training: Train your final model on the transformed training data (containing only the selected features).

- Validation: Evaluate the model on the held-out test set (

X_test).

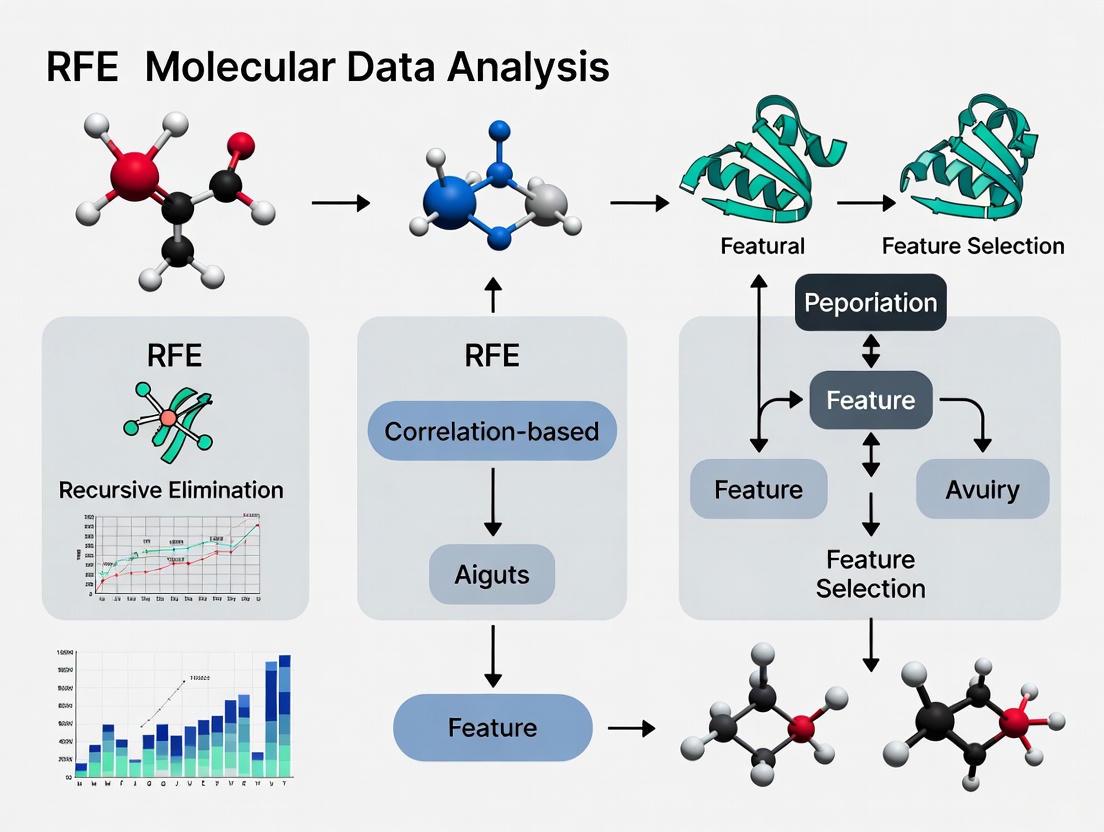

The following diagram illustrates the iterative RFE process:

Protocol 2: Correlation-Based Feature Selection for Multi-Source Data

Application: Efficiently selecting features from transcriptomics or other omics data pooled from multiple sources (e.g., different experimental batches or labs) [4].

Methodology:

- Data Stratification: Split the dataset by its source.

- Per-Source Correlation Analysis: For each data source and each class (e.g., cell type), calculate the correlation (e.g., Pearson or Mutual Information) between every feature and the class label [4].

- Per-Source Feature Ranking: For each source, rank the features based on their correlation scores and select the top

kfeatures from each class. - Feature Set Union: Combine all features selected from every source and class into a single, unified set of significant features.

- Final Model Training: Use this unified feature set to train a final machine learning model.

This two-step workflow is depicted below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and packages for feature selection in omics research.

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

scikit-learn (RFE, RFECV) [7] [2] |

Provides the core implementation of the Recursive Feature Elimination algorithm in Python. | General-purpose feature selection for any omics data (genomics, proteomics). |

| MoSAIC [9] | An unsupervised, correlation-based feature selection framework specifically designed for molecular dynamics data. | Identifying key functional coordinates in biomolecular simulation data. |

| FSelector R Package [1] | Offers various algorithms for filtering attributes, including correlation, chi-squared, and information gain. | Statistical feature ranking within the R programming environment. |

| Caret R Package [1] | A comprehensive package for classification and regression training that streamlines the model building process, including feature selection. | Creating predictive models and wrapping feature selection within a unified workflow in R. |

| Mutual Information [4] [5] | A statistical measure that captures any kind of dependency (linear or non-linear) between variables, used as a powerful filtering criterion. | Feature selection when non-linear relationships between features and the target are suspected. |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [3] | A measure of multicollinearity among features in a regression model. Helps identify and remove redundant features. | Diagnosing and handling multicollinearity in linear models after an initial feature selection. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Pearson correlation and Mutual Information for feature selection?

Pearson correlation measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two quantitative variables. Mutual Information (MI), an information-theoretic measure, quantifies how much knowing the value of one variable reduces uncertainty about the other, and can capture non-linear and non-monotonic relationships [10]. While MI is more general, extensive benchmarking on biological data has shown that for many gene co-expression relationships, which are often linear or monotonic, a robust correlation measure like the biweight midcorrelation can outperform MI in yielding biologically meaningful results, such as co-expression modules with higher gene ontology enrichment [10].

Q2: In the context of a thesis comparing RFE and correlation-based methods, when should I prefer correlation-based filtering?

Correlation-based feature selection is often an excellent choice for a rapid and computationally efficient initial dimensionality reduction, especially with high-dimensional data. It is a filter method, independent of a classifier, which makes it fast. In contrast, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper method that uses a machine learning model's internal feature weights (like those from Random Forest or SVM) to recursively remove the least important features [11]. RFE can be more powerful but is computationally intensive and may be influenced by correlated predictors [11]. A hybrid approach, using correlation-based filtering to reduce the feature set before applying RFE, is a common and effective strategy to manage computational cost [12].

Q3: How do I handle highly correlated features when using a model like Random Forest?

Random Forest's performance can be impacted by correlated predictors, which can dilute the importance scores of individual causal variables [11]. The Random Forest-Recursive Feature Elimination (RF-RFE) algorithm was proposed to mitigate this. However, in high-dimensional data with many correlated variables, RF-RFE may also struggle to identify causal features [11]. In such cases, leveraging prior knowledge to guide selection or using a data transformation that accounts for feature similarity (like a mapping strategy with a Bray-Curtis similarity matrix) before applying RFE has been shown to improve feature stability significantly [13].

Q4: How can I ensure my selected biomarker list is stable and biologically interpretable?

Stability—the robustness of the selected features to variations in the dataset—is a key challenge. To improve stability:

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use a mapping strategy that projects data into a new space using a feature similarity matrix (e.g., Bray-Curtis). This ensures that correlated and biologically similar features are treated as closer in the new space, leading to more stable selection [13].

- Employ Robust Metrics: For correlation, consider using robust measures like the biweight midcorrelation or Spearman's correlation, which are less sensitive to outliers than Pearson correlation [10].

- Validate with Biological Context: Use tools like Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the contribution of selected features in your model and validate their known biological roles [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Model Performance Despite a Large Number of Features

Symptoms: Your classifier (e.g., Random Forest or SVM) shows high accuracy on training data but poor performance on the test set or independent validation cohorts, indicating potential overfitting.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apply an initial correlation-based filter to reduce dimensionality. | High-dimensional data with many irrelevant features (noise) can easily lead to overfitted models. A quick pre-filtering step removes low-variance and non-informative features [4]. |

| 2 | Use a correlation coefficient threshold to select features most related to the outcome. | This creates a smaller, more relevant feature subset. For example, one study achieved a 73.3% reduction in features with a negligible performance drop by selecting tripeptides based on their Pearson correlation with the target [14]. |

| 3 | Compare the performance of your full model against the reduced model. | Use nested cross-validation for a robust evaluation. Studies have shown that a feature-selection stage prior to a final model like elastic net regression can lead to better-performing estimators than using elastic net alone [12]. |

Problem 2: Unstable Feature Selection Across Different Datasets

Symptoms: The list of top features (biomarkers) changes drastically when the analysis is run on different splits of your data or on similar datasets from different sources.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check for technical batch effects between datasets. | Features may be unstable because their relationship with the outcome is confounded by non-biological technical variation. |

| 2 | Implement a feature selection method that accounts for correlation structures. | Methods like DUBStepR use gene-gene correlations and a stepwise regression approach to identify a minimally redundant yet representative subset of features, which can improve stability [15]. |

| 3 | Apply a kernel-based data transformation before feature selection. | Research on microbiome data found that mapping features using the Bray-Curtis similarity matrix before applying Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) significantly improved the stability of the selected biomarkers without sacrificing classification performance [13]. |

Problem 3: Choosing Between Pearson Correlation and Mutual Information

Symptoms: You are unsure which association measure to use for your biological data to find the most biologically relevant features.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Start with a robust correlation measure. | For many biological relationships, a robust measure like the biweight midcorrelation (bicor) is sufficient and often leads to superior results in functional enrichment analyses compared to MI [10]. It is also computationally efficient. |

| 2 | If you suspect strong non-linear relationships, use Mutual Information or model-based alternatives. | If exploratory analysis suggests non-linearity, MI can be used. However, a powerful alternative is to use spline or polynomial regression models, which can explicitly model and test for non-linear associations while providing familiar statistical frameworks [10]. |

| 3 | Benchmark the methods for your specific goal. | Compare the functional enrichment (e.g., Gene Ontology terms) of gene modules or biomarker lists derived from correlation versus MI. The best method is the one that produces the most biologically interpretable results for your specific data and research question [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Correlation-Based Feature Pre-Filtering

This protocol details a method for reducing feature dimensionality using correlation coefficients, as applied in virus-host protein-protein interaction prediction [14].

1. Feature Extraction:

- From biological sequences (e.g., proteins), calculate the frequency of each possible tripeptide (or k-mer) based on a reduced amino acid alphabet (e.g., 7 clusters) [14].

- Normalize the frequency vectors for each sequence using min-max scaling over the range [0, 1].

- For a pair of interacting entities (e.g., virus and host proteins), concatenate their normalized feature vectors into a single, long vector.

2. Feature Selection:

- Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between each individual tripeptide feature and the binary outcome (e.g., interacting vs. non-interacting pairs).

- Rank all features based on the absolute value of their correlation coefficient.

- Apply a threshold (e.g., top 200 features, or a specific p-value cutoff) to select the most relevant features for downstream machine learning modeling.

Protocol 2: DUBStepR for Feature Selection in Single-Cell Data

This protocol outlines the DUBStepR (Determining the Underlying Basis using Stepwise Regression) workflow for identifying a minimally redundant feature set in single-cell transcriptomics data [15].

1. Calculate Gene-Gene Correlation Matrix:

- Compute the pairwise correlation matrix for all genes. DUBStepR leverages the fact that cell-type-specific marker genes tend to be highly correlated or anti-correlated with each other.

2. Stepwise Regression:

- Perform stepwise regression on the gene-gene correlation matrix to identify an initial set of "seed" genes.

- At each step, the gene that explains the largest amount of variance in the residual from the previous step is selected. This identifies a representative, minimally redundant subset of genes that span the major expression signatures in the dataset [15].

- Use the elbow point of the stepwise regression scree plot to determine the optimal number of seed genes.

3. Feature Set Expansion:

- Expand the seed gene set using a guilt-by-association approach. Iteratively add correlated genes from the initial candidate set to prioritize genes that strongly represent an expression signature.

- The expansion continues until an optimal number of feature genes is reached, as determined by a novel graph-based measure of cell aggregation called the Density Index (DI) [15].

Key Workflow Diagrams

Correlation vs. Mutual Information Selection Workflow

RFE vs. Correlation-Based Pre-Filtering

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and resources used in the experiments and methodologies cited in this guide.

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bray-Curtis Similarity Matrix [13] | Computational Metric / Transformation | Used to map microbiome features into a new space where similar features are closer, significantly improving the stability of subsequent feature selection algorithms like RFE. |

| DUBStepR [15] | R Software Package | A correlation-based feature selection algorithm for single-cell RNA-seq data that uses stepwise regression and a Density Index to identify an optimal, minimally redundant set of features for clustering. |

| Biweight Midcorrelation (bicor) [10] | Robust Correlation Metric | A median-based correlation measure that is more robust to outliers than Pearson correlation. Benchmarking shows it often leads to biologically more meaningful co-expression modules than mutual information. |

| Random Forest-Recursive Feature Elimination (RF-RFE) [11] | Machine Learning Wrapper Algorithm | An algorithm that iteratively trains a Random Forest model and removes the least important features to account for correlated variables and identify a strong predictor subset. |

| SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) [13] | Model Interpretation Framework | Used post-feature selection to interpret the output of machine learning models, explaining the contribution of each selected biomarker to individual predictions. |

| Reduced Amino Acid Alphabet [14] | Feature Engineering Technique | Groups the 20 standard amino acids into 7 clusters based on physicochemical properties, used to generate tripeptide composition features for sequence-based prediction tasks. |

This guide addresses common technical challenges when implementing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), a wrapper-style feature selection method that prioritizes predictive power by iteratively removing the least important features based on a model's internal importance metrics [6] [2]. For researchers in molecular data science, choosing between RFE and faster correlation-based filter methods (like Pearson correlation) is a critical decision. RFE often provides superior performance on complex biological datasets by accounting for feature interactions, albeit at a higher computational cost [6] [16]. The following sections provide troubleshooting and best practices for deploying RFE effectively in your research.

Troubleshooting Common RFE Implementation Issues

1. Problem: High Computational Time or Memory Usage

- Question: "My RFE process is too slow or runs out of memory, especially with high-dimensional omics data. What can I do?"

- Answer: This is a common issue with wrapper methods. Several strategies can help:

- Increase Step Size: Instead of removing one feature per iteration (

step=1), remove a percentage of features (e.g.,step=0.1to remove 10% of features each round) or a fixed numberfeature_numberto reduce the total number of model fits [17]. - Leverage Distributed Computing: For very large datasets, consider frameworks like the Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector and Distributed Multi-Kernel Classification Framework (SKR-DMKCF), which distributes computations across nodes, significantly improving speed and memory efficiency [18].

- Pre-Filtering: Use a fast filter method (e.g., correlation analysis) for initial dimensionality reduction before applying the more computationally intensive RFE [19].

- Increase Step Size: Instead of removing one feature per iteration (

2. Problem: Inconsistent or Suboptimal Feature Subsets

- Question: "The selected features change drastically with small changes in the dataset, or the final model performance is poor."

- Answer: Instability can arise from model overfitting or high variance in importance scores.

- Use Cross-Validation: Employ RFE with Cross-Validation (RFE-CV) to robustly estimate the optimal number of features. This runs RFE inside each cross-validation fold to find the feature set size that delivers the best and most stable performance [6] [17].

- Ensemble Methods: For high-dimensional, low-sample-size data (like microarrays), use ensemble RFE approaches. The WERFE algorithm, for example, aggregates results from multiple gene selection methods within an RFE framework, producing a more robust and compact gene subset [20]. Similarly, MCC-REFS uses an ensemble of classifiers with the Matthews Correlation Coefficient for a balanced evaluation, especially in imbalanced datasets [21].

- Check Algorithm Choice: Ensure the core estimator (e.g., SVM with linear kernel, Random Forest) is well-suited to your data. Tree-based models and linear SVMs are common, reliable choices [6] [2].

3. Problem: Handling Multicollinearity in Molecular Data

- Question: "My dataset has many correlated molecular features (e.g., genes in a pathway). How does RFE handle this compared to correlation-based selection?"

- Answer: This is a key differentiator between the methods.

- RFE Approach: RFE can handle multicollinearity to some degree, as the model-based importance score will reflect the contribution of correlated features. However, it may arbitrarily select one feature from a correlated group. Using a tree-based model can help, as it can reveal which feature in a correlated group is most consistently informative [6].

- Correlation-Based Limitation: Simple correlation analysis selects features based only on their individual relationship with the target, potentially choosing many redundant, highly correlated features that do not improve the model [19].

- Best Practice: If multicollinearity is a primary concern, consider combining RFE with a method like the Kruskal-RFE Selector, which integrates rank aggregation for more robust selection, or using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) before RFE, though this sacrifices the interpretability of original features [6] [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose RFE over a faster correlation-based filter method for my molecular dataset? A: The choice involves a trade-off between predictive power and computational efficiency. Use RFE when your primary goal is maximizing predictive accuracy, your dataset has complex feature interactions, and you have sufficient computational resources. Use correlation-based filter methods for a very quick, initial pass for dimensionality reduction, when interpretability of simple univariate relationships is key, or when dealing with extremely large datasets where RFE is computationally prohibitive [6] [19] [16].

Q2: How do I determine the optimal number of features to select with RFE?

A: Manually setting the number of features (n_features_to_select) can be difficult. The best practice is to use RFE with Cross-Validation (RFE-CV), which automatically determines the number of features that yields the best cross-validated performance [6] [2] [17]. Scikit-learn provides the RFECV class for this purpose.

Q3: Can RFE be used with any machine learning algorithm? A: RFE requires the underlying estimator (algorithm) to provide a way to calculate feature importance scores. It works well with algorithms that have built-in importance measures, such as: * Support Vector Machines (with linear kernel) * Decision Trees and Random Forests * Gradient Boosting Machines (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM) [2] [17] Algorithms without native importance support are not suitable for the standard RFE process.

Q4: How does RFE perform on highly imbalanced class data, common in medical diagnostics? A: Standard RFE can struggle with imbalanced data because the feature importance is based on the model's overall performance, which may be biased toward the majority class. For such cases, use variants designed for imbalance. The MCC-REFS method, which uses the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) as the selection criterion, is explicitly highlighted as effective for unbalanced class datasets [21].

Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

The table below summarizes a benchmark study comparing RFE to other methods on multi-omics data, providing a quantitative basis for method selection [16].

Table 1: Benchmarking Feature Selection Methods on Multi-Omics Data

| Method Type | Method Name | Key Characteristics | Average AUC (RF Classifier) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrapper | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Iteratively removes least important features | High | Very High |

| Filter | Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) | Selects features that are relevant to target and non-redundant | Very High | Medium |

| Embedded | Permutation Importance (RF-VI) | Uses Random Forest's internal importance scoring | Very High | Low |

| Embedded | Lasso (L1 regularization) | Performs feature selection during model fitting | High | Low |

| Filter | ReliefF | Weights features based on nearest neighbors | Low (for small feature sets) | Medium |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing RFE with Cross-Validation

This protocol outlines a robust workflow for using RFE in a molecular data classification task, such as cancer subtype identification from gene expression data.

1. Data Preprocessing:

* Scale Features: Standardize or normalize all features (e.g., using StandardScaler from scikit-learn), as model-based importance scores can be sensitive to feature scale [6].

* Address Imbalance: If present, apply techniques like SMOTE or use class weights in the underlying estimator [21].

2. Define the RFE-CV Process:

* Core Estimator: Choose an algorithm with feature importance (e.g., SVR(kernel='linear') or RandomForestClassifier()).

* RFE-CV Setup: Use RFECV in scikit-learn. Specify the estimator, cross-validation strategy (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold), and a scoring metric appropriate for your problem (e.g., scoring='accuracy' or 'auc').

* Fit the Model: Execute the fit() method on your training data.

3. Validation and Final Model Training:

* Identify Optimal Features: After fitting, RFECV will indicate the optimal number of features and which features to select (support_ attribute).

* Train Final Model: Transform your dataset to include only the selected features. Train your final predictive model on this reduced dataset and evaluate its performance on a held-out test set.

RFE Workflow and Method Comparison

RFE Iterative Process: This diagram illustrates the core, iterative workflow of the Recursive Feature Elimination algorithm.

RFE vs. Correlation-Based Selection: A direct comparison of the fundamental characteristics of wrapper (RFE) and filter (correlation) feature selection methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Algorithms

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for RFE Experiments

| Item / Algorithm | Function / Application Context |

|---|---|

Scikit-learn (sklearn.feature_selection.RFE / RFECV) |

Primary Python library for implementing RFE and RFE with Cross-Validation [6] [2]. |

| Linear SVM | A core estimator often used with RFE; its weight coefficients provide feature importance [6] [20]. |

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Tree-based algorithms whose built-in importance metrics (Mean Decrease in Impurity) are effective for RFE [2] [17]. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | A balanced performance measure used as the selection criterion in RFE variants for imbalanced datasets [21]. |

| mRMR (Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance) | A high-performing filter method often used in benchmarks as a strong alternative to RFE [16]. |

| WERFE / MCC-REFS | Ensemble-based RFE algorithms designed for robustness in high-dimensional, low-sample-size bioinformatics data [21] [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core trade-off between interpretability and model performance? Interpretability is the ability to understand and explain a model's decision-making process, while performance refers to its predictive accuracy. Simpler models like linear regression are highly interpretable but may lack complexity to capture intricate patterns. Complex models like neural networks can achieve high performance but act as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand why a prediction was made [22] [23].

2. When should I prioritize an interpretable model in molecular research? Prioritize interpretability in high-stakes applications where understanding the reasoning is critical. In molecular research, this includes:

- Biomarker Discovery: Identifying specific taxa or genes responsible for classifying disease states requires clear feature importance [13].

- Drug Development: Understanding which biological features a model uses for prediction is crucial for target identification and regulatory approval [23].

- Clinical Diagnostics: Providing explanations for a diagnosis, such as which microbial signatures influenced the prediction, builds trust and accountability [24] [23].

3. When can I justify using a higher-performance, less interpretable model? A higher-performance black-box model can be justified when:

- The primary goal is pure predictive accuracy for screening or prioritization.

- The model's output can be validated and trusted through extensive testing, even if its internal workings are complex [22].

- You use post-hoc explanation tools like SHAP to provide insights into the model's predictions after the fact [23].

4. How does feature selection impact this trade-off? Feature selection itself can improve both interpretability and performance. By reducing the number of features to the most relevant ones, you create a simpler model that is easier to interpret. This also lowers the risk of overfitting and reduces computational cost, which can enhance performance on new data [13] [25].

5. What are common pitfalls when using RFE on high-dimensional molecular data?

- Correlated Predictors: RFE can be negatively impacted by many correlated variables, which may cause it to discard causally important features [11].

- Instability: The feature selection process can be unstable, meaning small changes in the data can lead to different sets of selected features [13].

- Computational Demand: Running RFE on high-dimensional data (e.g., hundreds of thousands of features) is computationally intensive and requires significant memory and processing power [26] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unstable Feature Selection with RFE

Symptom: The list of top selected features changes significantly between different runs or data splits.

| Solution | Description | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Apply Data Transformation | Use a kernel-based data transformation (e.g., with a Bray–Curtis similarity matrix) before RFE. This projects features into a new space where correlated features are mapped closer together, improving stability. | [13] |

| Embed Prior Knowledge | Incorporate external data or domain knowledge to compute feature similarity, which can guide the selection process toward more robust biomarkers. | [13] |

| Use Bootstrap Embedding | Perform RFE within a bootstrap resampling framework to better assess the robustness of features across multiple data subsets. | [13] |

Problem: Poor Model Performance After Feature Selection

Symptom: The model's accuracy, precision, or other performance metrics drop after feature selection is applied.

| Solution | Description | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Check for Data Leakage | Ensure that no information from the test set was used during the feature selection process. Preprocessing and feature selection should be fit only on the training data. | [25] |

| Re-evaluate Feature Set Size | The number of features selected might be suboptimal. Use cross-validation to tune the number of features and find a better trade-off between simplicity and performance. | [13] |

| Try a Correlation-Based Method | If using RFE, consider switching to a correlation-based feature selection method like DUBStepR, which leverages gene-gene correlations and may perform better with certain data structures. | [15] |

Problem: Model is Accurate but Unexplainable

Symptom: Your model (e.g., a neural network) has high predictive performance, but you cannot explain its decisions to stakeholders or regulators.

| Solution | Description | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Use Explainability Tools | Apply post-hoc explanation methods such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to attribute the model's output to its input features for each prediction. | [23] |

| Create a Composite Model | Build a pipeline that uses a high-performance model for prediction and an inherently interpretable model (like logistic regression) on a reduced feature set to provide approximate explanations. | [24] |

| Quantify Interpretability | Use a framework like the Composite Interpretability (CI) score to systematically evaluate and compare models based on simplicity, transparency, and explainability, helping to justify your choice. | [24] |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: ML-Based RFE for Microbiome Biomarker Discovery

This protocol is adapted from a study classifying inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) using gut microbiome data [13].

Data Preparation:

- Data Source: Merge multiple abundance matrices from public repositories (e.g., Qiita). The example study used 1,569 samples (702 IBD patients, 867 healthy controls).

- Preprocessing: Aggregate taxa at the species (283 taxa) or genus (220 taxa) level. Normalize the data.

Stability-Enhancing Transformation:

- Compute the Bray–Curtis similarity matrix between samples.

- Use this matrix to map the original data into a new feature space, which accounts for correlation between taxa and improves the stability of subsequent feature selection.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE):

- Wrapper Setup: Use a machine learning algorithm (the study found Multilayer Perceptron best for large feature sets, and Random Forest for small sets) as the estimator for RFE.

- Process: Iteratively train the model, rank features by importance, and remove the least important ones. This is often done within a bootstrap embedding (e.g., 100 bootstraps) for robustness.

- Output: A ranked list of stable biomarkers.

Validation:

- Train a final model on the selected features.

- Evaluate classification performance on a held-out test set and an external ensemble dataset to ensure generalizability.

- Use Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to interpret the role and impact of each selected biomarker.

Quantitative Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

The table below summarizes findings from benchmarking studies on high-dimensional biological data [13] [15] [11].

| Method | Core Principle | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best-Suited Data Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE | Iteratively removes the least important features based on a model's feature importance. | Can improve performance by removing noise; works with any ML model. | Stability can be low; hindered by highly correlated features; computationally demanding. | Smaller datasets with fewer, less correlated predictors. |

| Correlation-Based (DUBStepR) | Selects features based on gene-gene correlations and a density index to optimize cluster separation. | High stability; outperforms other methods in cluster separation; robustly identifies marker genes. | Performance benchmarked mainly for clustering tasks; may be less straightforward for classification. | Large single-cell RNA-seq datasets for clustering; data with block-like correlation structures. |

| Highly Variable Genes (HVG) | Selects genes with variation across cells that exceeds a technical noise model. | Simple and fast; widely used in single-cell analysis. | Inconsistent performance across datasets; ignores correlations between genes. | A default, fast method for initial dimensionality reduction in single-cell analysis. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

Scikit-learn (sklearn.feature_selection.RFE) |

A Python library that provides the standard implementation of Recursive Feature Elimination, allowing integration with various estimators [7]. |

Caret R Package (rfe function) |

An R package that provides a unified interface for performing RFE with various models, including random forests, with built-in cross-validation [26]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A unified game theory-based framework to explain the output of any machine learning model, crucial for interpreting black-box models [13] [23]. |

| DUBStepR | An R package for correlation-based feature selection designed for single-cell data, but potentially applicable to other molecular data types [15]. |

| Bray–Curtis Similarity | A statistic used to quantify the compositional similarity between two different sites, used in microbiome studies to create a stability-enhancing mapping for RFE [13]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Feature Selection Method

Diagram 2: Enhanced RFE Workflow for Stability

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do RFE and correlation-based methods compare for high-dimensional molecular data?

Answer: The choice between Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and correlation-based feature selection involves a direct trade-off between computational cost and selection robustness. The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Feature | RFE | Correlation-based |

|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Wrapper method; recursively removes least important features using a model [7] [2]. | Filter method; ranks features by statistical measures (e.g., Pearson, Mutual Information) with the target [4]. |

| Handling Feature Interactions | Excellent; uses a model that can capture interactions between features [2]. | Poor; typically evaluates each feature independently, missing interactions [27]. |

| Computational Cost | High; requires training a model multiple times [27] [2]. | Low; relies on fast statistical computations [27] [4]. |

| Risk of Overfitting | Moderate; can be prone to overfitting, especially with complex base models [2]. | Lower; model-agnostic approach reduces risk of learning algorithm-specific noise [28]. |

| Performance on Imbalanced Molecular Data | Good, especially with balanced metrics. MCC-REFS uses Matthews Correlation Coefficient for better performance on imbalanced data [21]. | Variable; may favor majority class unless paired with sampling techniques [27]. |

| Best For | Identifying small, highly predictive feature sets where computational resources are sufficient [21]. | Rapidly reducing feature space on very large datasets as a first step [4]. |

FAQ 2: My model performs well on training data but fails on new data. Is this overfitting, and how can feature selection help?

Answer: Yes, this is a classic sign of overfitting, where a model learns noise and spurious patterns from the training data instead of the underlying biological signal [28] [29].

Feature selection reduces overfitting by:

- Reducing Model Complexity: A model with fewer parameters is less capable of memorizing noise [28] [29].

- Eliminating Irrelevant Features: By removing non-informative genes/variables, you reduce the chance the model will find false correlations [28].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- If you suspect overfitting: Compare your model's performance on training vs. validation/hold-out test sets. A significant drop in performance on the test set indicates overfitting [29].

- Solution with RFE: Ensure you are using a simple base estimator (e.g., Linear SVM) for the RFE process, or combine RFE with strong cross-validation [7] [2].

- Solution with Correlation: Use mutual information instead of Pearson correlation to capture non-linear relationships that may be more biologically relevant [4].

FAQ 3: My dataset has severe class imbalance. How does this impact feature selection?

Answer: Class imbalance can cause both RFE and correlation-based methods to bias feature selection toward the majority class, degrading model performance for the rare class (e.g., a rare cell type or disease subtype) [27].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- For RFE: Use a feature selection method designed for imbalance. The MCC-REFS algorithm, which uses the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) as its core metric, has been shown to outperform other methods on imbalanced bioinformatics datasets [21].

- For Correlation-based Methods: Combine them with data sampling techniques. Research has shown that applying the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) before feature selection can significantly improve the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for imbalanced datasets [27].

- General Practice: Always use evaluation metrics that are robust to imbalance (e.g., MCC, F1-score, Precision-Recall AUC) instead of accuracy when tuning the feature selection process [21] [27].

FAQ 4: The computational cost of my feature selection is too high. What can I do?

Answer: High computational cost is a common challenge with wrapper methods like RFE on large molecular datasets (e.g., 30,000+ genes) [4].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Strategy 1: Hybrid Approach. Use a fast filter method (like correlation) for an initial, aggressive feature reduction. Then, apply a more computationally expensive method like RFE on the shortlisted features [27] [4].

- Strategy 2: Optimize RFE Parameters. Increase the

stepparameter in RFE to remove a larger percentage of features in each iteration, significantly reducing the number of model training cycles [7]. - Strategy 3: Leverage Embedded Methods. Use models with built-in feature selection, such as Lasso regression or Random Forests. The

SelectFromModelfunction in scikit-learn can use these for efficient selection [28] [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Robust RFE Workflow for Molecular Data

This protocol is designed to mitigate overfitting while handling high-dimensional data.

1. Problem Formulation:

- Define your predictive target (e.g., cancer vs. normal, cell type classification).

- Prepare your data matrix where rows are samples and columns are molecular features (e.g., gene expression levels).

2. Initial Setup and Preprocessing:

- Split Data: Divide data into training, validation, and test sets. The test set should only be used for the final evaluation. [29]

- Normalize Data: Apply appropriate normalization (e.g., Z-score) to the training data and use the same parameters to transform the validation/test sets.

3. Configure and Execute RFE with Cross-Validation:

- Create a Pipeline: Combine RFE and a classifier within a

sklearn.pipeline.Pipelineto prevent data leakage [2]. - Choose Base Estimator: Select an estimator that provides feature importance (e.g.,

DecisionTreeClassifier, Linear SVM) [7] [2]. - Determine Number of Features: Use

RFECV(RFE with cross-validation) to automatically find the optimal number of features, or perform a grid search forn_features_to_select[7].

4. Validation and Final Model Training:

- Validate on Hold-out Set: Assess the performance of the model with the selected features on the validation set.

- Final Training: Once satisfied, train the final model on the entire training set (training + validation) using the selected feature subset.

- Final Evaluation: Report the final performance on the untouched test set [29].

Protocol 2: A Two-Step Correlation-Based Selection for Multi-Source Data

This protocol is particularly useful for large-scale transcriptomics data integrated from multiple sources, as it accounts for source-specific biases [4].

1. Data Preparation:

- Organize your dataset by source. For example, if combining data from GEO, 10X, and in-house platforms, keep them as separate logical groups.

2. Step 1: Intra-Source Feature Selection:

- For each data source individually:

- Calculate Correlation: For each feature, compute its correlation with the target variable. Use Pearson's correlation for linear relationships or Mutual Information for non-linear relationships [4].

- Select Top Features: Within each source and for each class (if multi-class), retain the top k most correlated features. The value of k can be a fixed number or a percentile.

3. Step 2: Inter-Source Feature Aggregation:

- Union of Features: Combine all features selected from any source in Step 1 into a final global feature set. This ensures features that are predictive in specific contexts are retained [4].

4. Model Training and Evaluation:

- Create Unified Dataset: Extract the global feature set from all samples across all sources.

- Train and Evaluate: Proceed with model training and evaluation using standard practices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn Library | Provides standardized implementations of RFE, correlation-based selection, and various models for a reproducible workflow [7] [28]. | Use sklearn.feature_selection.RFE and sklearn.feature_selection.SelectKBest. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | A robust metric for feature selection and evaluation on imbalanced binary and multi-class datasets; more informative than accuracy [21]. | Core component of the MCC-REFS method [21]. |

| Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) | A sampling technique to generate synthetic samples for the minority class, used alongside feature selection to handle imbalance [27]. | Applying SMOTE before feature selection improved AUC by up to 33.7% in one study [27]. |

| Mutual Information | A filter-based feature selection metric that can capture non-linear relationships between features and the target, unlike Pearson correlation [4]. | Crucial for finding functional dependencies in gene expression data [4]. |

| Pearson's Correlation Coefficient | A fast, linear statistical measure to quantify the association between a feature and a continuous target or a binary class [4]. | Computed per feature; scale-invariant [4]. |

| Pipeline Utility | A software tool to chain data preprocessing, feature selection, and model training to prevent data leakage and ensure rigorous validation [2]. | Available in sklearn.pipeline.Pipeline. |

Practical Implementation: Applying RFE and Correlation Methods to Real-World Data

Step-by-Step Guide to Correlation-Based Feature Selection for Transcriptomics Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use correlation-based feature selection over Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for my transcriptomics data?

Correlation-based feature selection is a filter method that is generally faster and less computationally expensive than wrapper methods like RFE because it doesn't require training a model multiple times [3]. It helps minimize redundancy by selecting features that are highly correlated with the target but have low correlation with each other, which can lead to more interpretable models, a key concern in biological research [30]. RFE, while powerful, can be computationally intensive and may overfit to the specific model used during the selection process [16].

Q2: I'm working with single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from multiple sources. Why does my feature selection performance vary, and how can I improve it?

The significance of individual features (genes) can differ greatly from source to source due to differences in sample processing, technical conditions, and biological variation [4]. A simple but effective strategy is to perform feature selection per source before combining results. First, select the most significant features for each data source and cell type separately using correlation coefficients or mutual information. Then, combine these source-specific features into a single set for your final model [4].

Q3: My clustering results seem to erroneously subdivide a homogeneous cell population. How can I prevent this false discovery?

This is a known challenge where some feature selection methods fail the "null-dataset" test. To address this, consider using anti-correlation-based feature selection [31]. This method identifies genes with a significant excess of negative correlations with other genes. In a truly homogeneous population, these anti-correlation patterns disappear, and the algorithm correctly identifies no valid features for sub-clustering, thus preventing false subdivisions [31].

Q4: How many features should I ultimately select for my analysis?

The optimal number depends on your dataset and biological question. For some tasks, a few hundred well-chosen features can be sufficient [32] [15]. It is good practice to evaluate the stability of your downstream results (e.g., clustering accuracy or classification performance) across a range of feature set sizes. Benchmarking studies suggest that methods like minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) can achieve strong performance with relatively few features (e.g., 10-100) [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Performance After Feature Selection

- Potential Cause 1: High Redundancy in Selected Features. Your feature set may contain many highly correlated genes, providing duplicate information.

- Solution: Incorporate a redundancy check. Use the

findCorrelationfunction from thecaretR package with a high cutoff (e.g., 0.75) to remove features that are highly correlated with others [33].

- Solution: Incorporate a redundancy check. Use the

- Potential Cause 2: Exclusion of Weak but Informative Features.

- Solution: Avoid relying on a single metric. Combine correlation with other filter methods, such as mutual information, which can capture non-linear relationships between genes and the target variable [4].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Across Different Datasets or Batches

- Potential Cause: Batch effects or source-specific technical variation are dominating the biological signal.

- Solution: Implement a multi-source feature selection strategy. Perform feature selection individually on each batch or data source, then integrate the results by taking the union of the top features from each source. This ensures selected features are robust across different conditions [4].

Problem: Feature Selection Leads to Over-subclustering

- Potential Cause: The feature selection method is sensitive to technical noise rather than true biological variation, especially in single-cell data.

- Solution: Apply an anti-correlation-based feature selection algorithm. This method is specifically designed to prevent the false discovery of subpopulations in homogeneous data by leveraging the principle that true cell-type marker genes often exhibit mutual exclusivity [31].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: A Two-Step Correlation-Based Feature Selection for Multi-Source Transcriptomics Data This protocol is adapted from a study on single-cell transcriptomics data from multiple sources [4].

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize your transcriptomics data (e.g., counts per million for bulk RNA-seq, standard normalization for scRNA-seq) separately for each data source.

- Step 1 - Per-Source Feature Selection:

- For each data source and each cell type or phenotype of interest, calculate the correlation (e.g., Pearson for regression, mutual information for classification) between each gene and the target label.

- For each source, rank the genes based on their correlation strength and select the top k genes (e.g., top 500) from this ranked list.

- Step 2 - Feature Set Integration:

- Aggregate all the genes selected from the individual sources in Step 1 into a unified set of candidate features.

- This final set is used for downstream training of your classification or clustering model.

Protocol: Implementing Correlation-based Feature Selection with a Redundancy Check This is a general protocol for a single dataset, applicable in programming environments like R [33] [30].

- Calculate Correlation Matrix: Compute the correlation matrix for all features (genes) and the target variable.

- Rank Features: Rank the features based on the absolute value of their correlation with the target variable in descending order.

- Select Top Features: Choose a threshold (e.g., top 100 features) or a correlation coefficient cutoff.

- Remove Redundant Features: On the selected top features, apply a redundancy filter. Identify and remove features that have a correlation higher than a set cutoff (e.g., 0.75) with another, more highly-ranked feature.

Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods The table below summarizes findings from benchmark studies on omics data [16].

| Method | Type | Key Strength | Computational Cost | Note on Transcriptomics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRMR | Filter | Selects features with high relevance and low redundancy [16]. | Medium | Often a top performer with few features [16]. |

| RF-VI (Permutation Importance) | Embedded | Model-specific, often high accuracy [16]. | Low | Leverages Random Forest; robust. |

| Lasso | Embedded | Performs feature selection as part of model fitting [34]. | Low | Tends to select more features than mRMR/RF-VI [16]. |

| RFE | Wrapper | Can yield high-performing feature sets [16]. | Very High | Prone to overfitting; computationally expensive [3] [16]. |

| Anti-correlation | Filter | Prevents false sub-clustering in single-cell data [31]. | Medium | Specifically addresses a key pain point in scRNA-seq. |

Key Reagent Solutions for Transcriptomics Feature Selection

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Normalized Transcriptomics Matrix | The primary input data (e.g., gene-by-cell matrix). Normalization is critical for valid correlation calculations. |

| Correlation Metric (Pearson/Spearman) | Measures linear (Pearson) or monotonic (Spearman) relationships between a gene and the target variable. |

| Mutual Information Metric | Measures linear and non-linear dependencies between variables, useful for classification tasks [4] [30]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for processing large transcriptomics datasets with thousands of features and samples [4]. |

| DUBStepR Algorithm | A scalable, correlation-based feature selection method designed for accurately clustering single-cell data [15]. |

Methodology Visualization

Correlation-Based Feature Selection Workflow

RFE vs. Correlation-Based Feature Selection

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my RFE process extremely slow when using tree-based models like Random Forest or XGBoost on my high-dimensional molecular dataset?

Answer: This is a common issue stemming from the inherent computational complexity of wrapper methods like RFE when combined with ensemble classifiers.

Detailed Explanation: Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a greedy wrapper method that iteratively constructs models and removes the least important features [35]. When wrapped around computationally intensive models like Random Forest or XGBoost, the process can become prohibitively slow on high-dimensional data. Empirical evaluations have shown that RFE wrapped with tree-based models such as Random Forest and XGBoost, while yielding strong predictive performance, incurs high computational costs and tends to retain large feature sets [35].

Solutions:

- Implement Enhanced RFE: Consider using a variant known as Enhanced RFE, which achieves substantial feature reduction with only marginal accuracy loss, offering a favorable balance between efficiency and performance [35].

- Use a Hybrid Approach: For an initial rapid reduction of the feature space, employ a fast filter method (like correlation-based selection) before applying RFE with your chosen classifier [35].

- Leverage Computational Optimizations: Utilize hardware acceleration (GPUs) and ensure you are using optimized libraries (like scikit-learn) that can leverage parallel processing for tree-based algorithms.

FAQ 2: My RFE results are unstable between runs, selecting different feature subsets each time. How can I improve reproducibility?

Answer: Instability in feature selection, especially in the presence of highly correlated features, is a recognized challenge.

Detailed Explanation: Most standard feature selection methods focus on predictive accuracy, and their performance can degrade in the presence of correlated predictors [36]. In molecular data, features are often highly correlated (e.g., gene expressions from the same pathway). In such "tangled" feature spaces, different features can be interchangeably selected across runs, leading to instability [36].

Solutions:

- Stability Selection Framework: Implement a framework like

TangledFeatures, which identifies representative features from groups of highly correlated predictors [36]. This involves:- Clustering: Grouping features based on pairwise correlations above a defined threshold.

- Selection: Using an ensemble-based stability procedure to pick a single, robust representative feature from each cluster.

- Refinement: Applying a final RFE step to the set of cluster representatives [36].

- Ensemble Feature Selection: Use multiple algorithms to select features and take the union of the selected subsets. For example, the Union with RFE (U-RFE) framework uses LR, SVM, and RF as base estimators within RFE and then performs a union analysis of the resulting subsets to determine a final, more robust feature set [37].

FAQ 3: I have a limited sample size for my molecular study. Is RFE still a suitable feature selection method?

Answer: Yes, RFE can be effectively applied to small sample sizes, but it requires specific methodological enhancements to prevent overfitting.

Detailed Explanation: Small sample sizes are a common challenge in molecular research (e.g., patient cohort studies). Traditional RFE may overfit in such scenarios. However, an improved Logistic Regression model combined with k-fold cross-validation and RFE has been successfully applied to a small sample size (n=100) to select important features [38]. The k-fold cross-validation ensures the model makes full use of the limited data for reliable performance estimation [38].

Solutions:

- Integrate Cross-Validation: Embed k-fold cross-validation directly into the RFE process. This helps in obtaining a more reliable estimate of feature importance and model performance at each iteration [38].

- Choose Simpler Base Classifiers: For very small sample sizes, using a simpler model like Logistic Regression as the base estimator for RFE can be more stable and less prone to overfitting than complex ensemble methods [38].

FAQ 4: How do I choose the best base classifier (SVM, RF, XGBoost) for RFE in the context of molecular data?

Answer: The choice involves a trade-off between predictive performance, computational cost, and the interpretability of the final feature set.

Detailed Explanation: Different classifiers have different strengths when used within RFE. The table below summarizes empirical findings from benchmarking studies [35] [37].

Performance Comparison of Classifiers within RFE

| Classifier | Predictive Performance | Computational Cost | Feature Set Size | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVM | Good performance in various tasks [37]. | Moderate | Varies | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; feature importance is based on model coefficients [39]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Strong performance, captures complex interactions [35]. | High | Tends to retain larger feature sets [35] | Robust to noise; provides intrinsic feature importance measures [39]. |

| XGBoost | Strong performance, slightly outperforms RF in some cases [37]. | High | Tends to retain larger feature sets [35] | Handles complex non-linear relationships; includes regularization to prevent overfitting [39]. |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | Good performance, especially with enhanced RFE for small samples [38]. | Low | Can achieve substantial reduction [38] | Simple, efficient, highly interpretable [38]. |

Decision Guide:

- For high interpretability and efficiency with small-to-medium datasets, consider Logistic Regression or SVM.

- For maximum predictive accuracy and you have sufficient computational resources, use Random Forest or XGBoost.

- For a balanced approach between performance and feature set size, explore Enhanced RFE variants [35].

Experimental Protocols for Key RFE Experiments

Protocol 1: Benchmarking RFE Variants on a Molecular Classification Task

This protocol outlines a comparative evaluation of RFE with different classifiers, suitable for a thesis chapter comparing feature selection methods.

1. Objective: To evaluate and compare the performance of RFE when implemented with SVM, Random Forest, and XGBoost on a high-dimensional molecular dataset (e.g., gene expression or proteomics data).

2. Materials and Dataset:

- A curated molecular dataset (e.g., from TCGA for colorectal cancer classification [37]).

- Computing environment with Python and libraries: scikit-learn, XGBoost, pandas.

3. Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values, normalize or standardize features, and encode the target variable.

- Model Training & Feature Selection:

- Initialize the three classifiers (SVM, RF, XGBoost) with their recommended default or tuned hyperparameters.

- For each classifier, create an

RFEobject. Specify the number of features to select or use automatic selection based on cross-validation. - Fit the

RFEobject on the training data. This process will recursively train the model and eliminate the least important features. - Extract the final selected feature subset from each

RFEinstance.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Train a final model on the training set using only the features selected by each RFE variant.

- Evaluate the model on the held-out test set using metrics such as Accuracy, F1-score (weighted for imbalanced data), and Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [37].

- Analysis:

- Compare the classification performance of the three RFE-classifier combinations.

- Compare the size and composition of the feature subsets selected by each method.

- Record and compare the computational time for each RFE process.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Union-RFE (U-RFE) Framework for Robust Feature Selection

This protocol is for a more advanced experiment, demonstrating how to combine the strengths of multiple classifiers to achieve a more stable feature set.

1. Objective: To implement the U-RFE framework to select a union feature set that improves classification performance for multi-category outcomes on a complex dataset [37].

2. Materials and Dataset:

- A dataset with clinical and omics data, such as the TCGA dataset for colorectal cancer with multi-category causes of death [37].

3. Methodology:

- Stage 1: Parallel RFE with Multiple Estimators

- Use three different base estimators (e.g., LR, SVM, RF) to run RFE independently on the dataset.

- From each RFE run, obtain a feature subset containing the top N features (e.g., top 50).

- Stage 2: Union Analysis

- Perform a union operation on the three feature subsets obtained from Stage 1. The resulting union set may contain more than N features.

- This final union feature set combines the advantages of the different algorithms [37].

- Stage 3: Final Model Building and Evaluation

- Train various classification algorithms (LR, SVM, RF, XGBoost, Stacking) using the union feature set.

- Evaluate and compare the performance of all models to identify the best performer for your specific task [37].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

RFE with Single Classifier Workflow

Union RFE (U-RFE) Framework Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for RFE Experiments in Molecular Research

| Item | Function | Example Application in RFE |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn Library | A core machine learning library in Python providing implementations for SVM, Random Forest, and the RFE class. |

Used to create the RFE wrapper around any of the supported classifiers and manage the entire recursive elimination process [35]. |

| XGBoost Library | An optimized library for gradient boosting, providing the XGBClassifier. | Serves as a powerful base estimator for RFE to capture complex, non-linear relationships in molecular data [39] [37]. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Libraries for data manipulation and numerical computations. | Used for loading, cleaning, and preprocessing the molecular dataset (e.g., handling missing values, normalization) before applying RFE. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model. | Used for post-hoc interpretation of the RFE-selected model, providing consistent and reproducible feature importance scores, which is crucial for biological insight [36]. |

| Stability Selection Algorithms | Frameworks (e.g., TangledFeatures) designed to select robust features from highly correlated spaces. |

Applied to the results of RFE or in conjunction with it to improve the stability and reproducibility of the selected molecular features (e.g., genes, proteins) [36]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the key innovation of the Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector? The Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector introduces a novel feature selection method that combines the Kruskal-Wallis test with Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). This hybrid approach efficiently handles high-dimensional medical datasets by leveraging the Kruskal-Wallis test's ability to evaluate feature importance without assuming data normality, followed by recursive elimination to select the most informative features. This synergy reduces dimensionality while preserving critical characteristics, achieving an average feature reduction ratio of 89% [18].

FAQ 2: How does the Kruskal-Wallis test improve feature selection in RFE? The Kruskal-Wallis test is a non-parametric statistical method used to determine if there are statistically significant differences between two or more groups of an independent variable. When used within RFE, it serves as a robust feature ranking criterion, especially effective for high-dimensional and low-sample size data. It does not assume a normal distribution, making it suitable for various data types, including omics data, and performs well with imbalanced datasets common in molecular research [40] [41].

FAQ 3: My model performance plateaued after feature selection. What could be wrong? Performance plateaus can often be traced to a misordering of features during the selection process. This occurs when the feature selection metric (e.g., Kruskal-Wallis) ranks a feature differently than how the final classification model (evaluated by accuracy) would. This is a known challenge when using filter methods like Kruskal-Wallis with wrapper or embedded models. Ensure that the feature importance metric aligns with your model's objective and validate selected features using the target model's performance [42].

FAQ 4: What are the computational benefits of using a distributed framework like DMKCF? The Distributed Multi-Kernel Classification Framework (DMKCF) is designed to work with feature selection methods like Kruskal-RFE in a distributed computing environment. Its primary benefits include a significant reduction in memory usage (up to 25% compared to existing methods) and a substantial improvement in processing speed. This scalability is crucial for handling large-scale molecular datasets in resource-limited environments [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling High-Dimensional Data with Low Sample Sizes

Problem: Feature selection is unstable or produces inconsistent results when the number of features (p) is much larger than the number of samples (n), a common scenario in molecular data research.

Solution:

- Implement Ensemble Stability: Use an ensemble approach like MCC-REFS (Matthews Correlation Coefficient - Recursive Ensemble Feature Selection). This method employs multiple machine learning classifiers to rank features, improving robustness. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) is a more reliable performance measure for imbalanced datasets than accuracy [21].

- Leverage Distributed Computing: For extremely large datasets, implement the selection process within a distributed computing framework (e.g., Apache Spark) to partition the workload and reduce memory constraints, as demonstrated in the SKR-DMKCF architecture [18].

- Protocol: The MCC-REFS protocol involves:

- Training an ensemble of eight diverse classifiers.

- Using MCC to evaluate and rank features from each classifier.

- Aggregating the rankings to select the most compact and informative feature set automatically, without pre-defining the number of features [21].

Issue 2: Managing Class Imbalance in Molecular Datasets

Problem: The selected features are biased towards the majority class, leading to poor predictive performance for minority classes (e.g., a rare disease subtype).

Solution:

- Use Balanced Metrics: Replace standard feature importance scores with the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) during the recursive elimination process. MCC provides a balanced evaluation even when class sizes are very different [21].

- Validate with Appropriate Metrics: During the evaluation phase, do not rely solely on accuracy. Monitor precision and recall, or the F1-score, to get a complete picture of model performance across all classes. The SKR-DMKCF framework, for instance, reported precision of 81.5% and recall of 84.7%, demonstrating balanced performance [18].

Issue 3: Interpreting Feature Selection Results for Biomarker Discovery

Problem: It is difficult to justify and explain why specific features (potential biomarkers) were selected for downstream drug development decisions.

Solution:

- Integrate Interpretability: Choose methods that provide transparent feature rankings. The Kruskal-Wallis test provides a clear H-statistic for ranking features based on their ability to separate sample groups. Similarly, RFE provides a

ranking_attribute that shows the relative importance of all features [7] [40]. - Visualization and Reporting: Generate feature importance plots from the RFE object. For the Kruskal-Wallis test, report the H-statistic and p-value for top-ranked features to provide statistical evidence for their selection.

Experimental Data & Performance

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Medical Datasets

| Method | Average Accuracy | Precision | Recall | Feature Reduction Ratio | Memory Usage Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKR-DMKCF (Proposed) | 85.3% | 81.5% | 84.7% | 89% | 25% |

| REFS | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Not Reported |

| GRACES | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Not Reported |

| DNP | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Not Reported |

| GCNN | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Available in source [21] | Not Reported |

Source: Adapted from [18] and [21].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Ensemble of Classifiers (e.g., SVM, Random Forest, etc.) | Used in MCC-REFS to provide robust, aggregated feature rankings and avoid reliance on a single model [21]. |

| Distributed Computing Framework (e.g., Spark) | Enables scalable processing of large-scale molecular datasets by distributing computational workloads across multiple nodes [18]. |

| Multi-Kernel Learning Framework | Combines different kernel functions to capture various nonlinear relationships in the data after feature selection, improving classification [18]. |

| Kruskal-Wallis H Test | Serves as a non-parametric criterion for ranking features based on their association with the target variable, without assuming data normality [40] [41]. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | Provides a balanced measure of classification performance for feature evaluation, especially critical for imbalanced molecular datasets [21]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the Synergistic Kruskal-RFE Selector