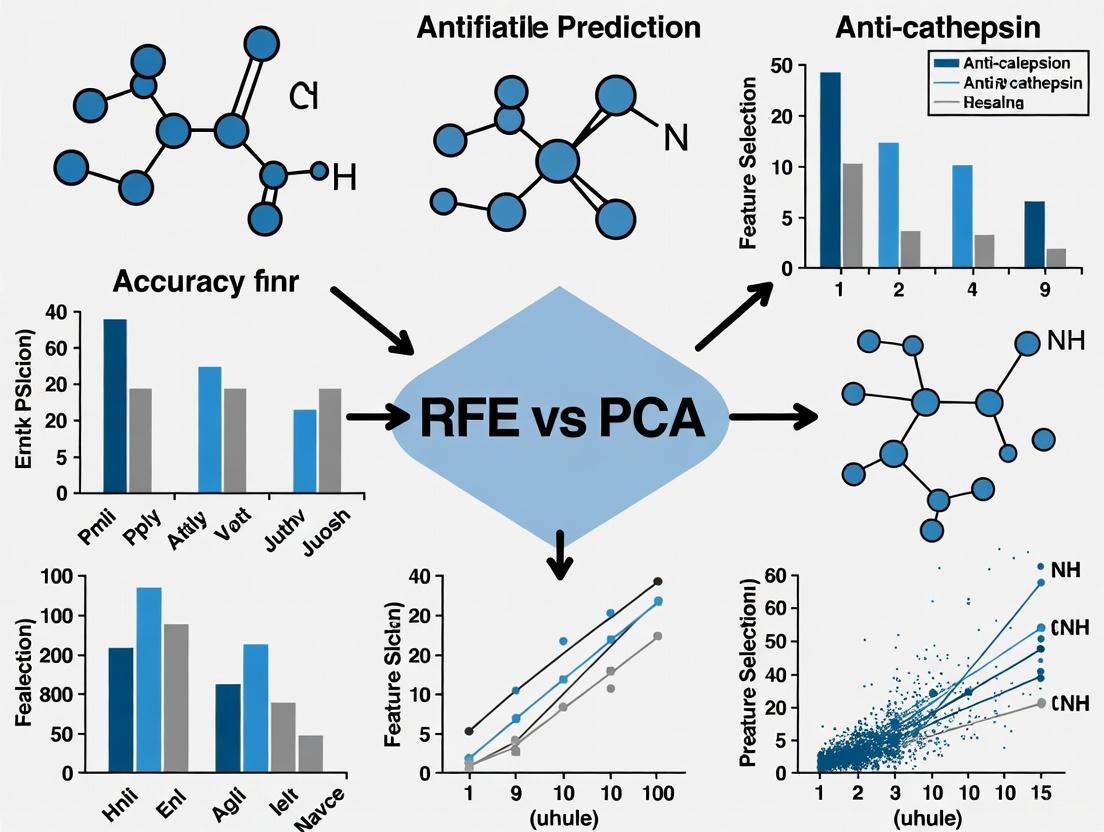

RFE vs PCA: A Machine Learning Guide to Boost Anti-Cathepsin Prediction Accuracy

Selecting the optimal feature selection technique is critical for developing accurate and generalizable machine learning models in drug discovery.

RFE vs PCA: A Machine Learning Guide to Boost Anti-Cathepsin Prediction Accuracy

Abstract

Selecting the optimal feature selection technique is critical for developing accurate and generalizable machine learning models in drug discovery. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, comparing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for predicting anti-cathepsin activity. We explore the foundational principles of cathepsin L as a therapeutic target and the role of molecular descriptors. A detailed methodological guide for implementing RFE and PCA is presented, alongside strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like overfitting and computational constraints. The discussion is grounded in comparative validation, reviewing performance metrics and real-world case studies to guide the selection of the most effective feature selection strategy for robust anti-cathepsin inhibitor discovery.

Cathepsin L Inhibition and Molecular Descriptors: Building Blocks for Predictive Modeling

The Role of Cathepsin L in Cancer and Disease Pathogenesis

Cathepsin L (CTSL) is a lysosomal cysteine protease that plays a crucial role in intracellular protein degradation, antigen presentation, and tissue remodeling [1]. Under physiological conditions, CTSL is confined within lysosomes and operates optimally in acidic environments. However, in pathological states—particularly in cancer—CTSL expression becomes dysregulated, its subcellular localization alters, and it is often secreted into the extracellular space [2] [3]. This ectopic expression enables CTSL to degrade components of the extracellular matrix (ECM), including collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, facilitating tumor invasion and metastatic dissemination [2]. Elevated CTSL expression correlates strongly with poor prognosis across various cancers, including glioma, melanoma, and pancreatic, breast, and prostate carcinomas [2]. Beyond its well-characterized role in tumor progression, recent research has identified CTSL as a critical mediator of cancer stemness, multidrug resistance, and viral entry mechanisms, positioning it as a promising therapeutic target in oncology and infectious disease [4] [3].

Mechanistic Roles of Cathepsin L in Cancer Progression

Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Metastasis

The degradation of the extracellular matrix is a fundamental step in cancer metastasis, and CTSL is a master regulator of this process. In the acidic tumor microenvironment, secreted CTSL directly cleaves ECM components such as collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, dismantling structural barriers that would otherwise contain tumor growth [2]. Furthermore, CTSL promotes invasion by cleaving E-cadherin, a key cell-cell adhesion molecule. The loss of E-cadherin function enhances the dissociation of cancer cells from the primary tumor, enabling their migration and invasion into surrounding tissues [2]. Clinical evidence consistently shows that high CTSL expression is associated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and metastatic progression.

Induction of Stemness and Multidrug Resistance

Emerging evidence underscores the role of CTSL in promoting cancer stemness and chemoresistance. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), spheroid-forming cells (enriched for cancer stem cells) exhibit significantly higher CTSL expression compared to adherent cells. This elevated CTSL expression is functionally linked to the upregulation of stem cell markers (CD133 and CD44), stemness-maintaining transcription factors (OCT4 and SOX2), and drug-resistance proteins (MDR1 and ABCG2) [3]. Mechanistically, CTSL directly transcriptionally regulates HGFAC (HGF activator), thereby activating the HGF/Met signaling axis. This pathway critically enhances stemness properties and confers resistance to a broad spectrum of chemotherapeutic agents, including paclitaxel, docetaxel, and platinum-based drugs [3]. Targeting CTSL with inhibitors or siRNA sensitizes NSCLC spheroids to these chemotherapeutics, reduces stemness, and suppresses tumor growth in vivo, confirming its pivotal role in multidrug resistance.

Regulation of Immune Responses

Within the tumor immune microenvironment, CTSL significantly influences antigen presentation and immune cell function. In thymic epithelial cells (TECs), CTSL is essential for the degradation of the invariant chain (Ii) during the processing of MHC class II molecules [1]. This proteolytic activity is required for the formation of the class II-associated invariant chain peptide (CLIP), a critical step in loading antigenic peptides onto MHC II for presentation to CD4+ T cells [1]. Although this function is vital for adaptive immunity under normal conditions, its dysregulation in the tumor context can contribute to immune evasion. Furthermore, in certain cancer types, CTSL can also influence the cross-presentation of antigens on MHC-I molecules, potentially modulating CD8+ T cell responses [1].

Facilitation of Viral Entry

Independent of its role in cancer, CTSL has been identified as a host factor required for viral entry of certain pathogens, most notably SARS-CoV-2. A 2025 study employing a clickable photo-crosslinking probe identified CTSL as the direct molecular target of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) in host cells [4]. The study demonstrated that HCQ significantly inhibits CTSL protease activity, thereby suppressing the CTSL-dependent cellular entry pathway utilized by coronaviruses. This finding elucidates the mechanistic basis for the observed antiviral effects of HCQ and CQ and positions CTSL as a potential therapeutic target for emerging infectious diseases [4].

Comparative Analysis of Cathepsin L in Therapeutic Targeting

The development of CTSL inhibitors encompasses a range of strategies, from novel compound discovery to drug repurposing. The table below summarizes key therapeutic approaches and their current status.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cathepsin L-Targeting Strategies

| Therapeutic Approach | Key Findings/Compounds | Model System | Therapeutic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Compound Inhibition [2] | ZINC4097985 & ZINC4098355 identified via machine learning; Binding affinity: -7.9 kcal/mol and -7.6 kcal/mol; Stable complex in 200ns MD simulation. | In silico screening (IC(_{50}) dataset, Biopurify & Targetmol libraries) | High potential for cancer management; Pending experimental validation. |

| Drug Repurposing [4] | Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) identified as direct CTSL binder; Inhibits CTSL protease activity. | Cell-based coronavirus entry assays, in silico analysis | Suppresses viral entry; Reveals mechanism for HCQ's antiviral effect. |

| Computational QSAR Modeling [5] | LMIX3-SVR model (R²=0.9676 training, 0.9632 test) for predicting IC(_{50}); 578 new compounds designed. | In silico QSAR modeling and molecular docking | Robust predictive tool for efficient screening of novel CatL inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2. |

| Direct CTSL Inhibition [3] | CTSL inhibitor combined with docetaxel; Suppressed tumor growth in vivo. | NSCLC spheroid models, in vivo mouse models | Overcame multidrug resistance; Effective in reducing cancer stemness. |

Experimental Protocols for CTSL Research

In Vitro Functional Assays

Tumorsphere Formation Assay: This is a key method for evaluating cancer stem cell activity. Cells are cultured at low density (e.g., 200 cells/well) in ultra-low attachment plates using serum-free medium supplemented with growth factors (e.g., bFGF and EGF at 20 ng/mL). After 7 days, tumorspheres with a diameter >100 μm are counted to quantify self-renewal capacity. Interfering with CTSL via siRNA or pharmacological inhibitors significantly reduces tumorsphere formation, indicating a loss of stemness [3].

CCK-8 Viability and Drug Sensitivity Assay: To assess chemoresistance, adherent cells and spheroids are plated in 96-well plates (e.g., 3x10³ cells/well) and treated with a range of concentrations of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g., Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Cisplatin) for 48 hours. The CCK-8 solution is then added, and after 4 hours of incubation, the absorbance at 450 nm is measured. Dose-response curves generated from this assay clearly demonstrate that CTSL inhibition increases sensitivity to multiple drugs [3].

Western Blot and qRT-PCR Analysis: These techniques are used to validate the molecular mechanisms of CTSL. Western blotting can assess the protein levels of CTSL, stemness markers (CD133, CD44, OCT4, SOX2), and drug-resistance proteins (MDR1, ABCG2) [3]. Concurrently, qRT-PCR measures the corresponding mRNA expression levels, often revealing that CTSL inhibition downregulates these key players. The direct transcriptional regulation of HGFAC by CTSL can be confirmed using Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by qPCR (ChIP-qPCR) [3].

Computational Screening and Modeling

Machine Learning (ML)-Guided Virtual Screening: A robust ML model, such as Random Forest, can be trained on a large dataset of compounds with known CTSL IC(_{50}) values (e.g., 2000 active and 1278 inactive molecules from CHEMBL). The model, achieving high accuracy (AUC ~0.91), is then used to screen natural compound libraries. Top hits are subsequently subjected to structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) via molecular docking to predict binding affinity and interaction modes with key CTSL active site residues (e.g., Cys25, His163, Asp162). This combined ML/SBVS approach efficiently filters promising candidates like ZINC4097985 [2].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling: An enhanced Support Vector Regression (SVR) model with a hybrid linear-RBF-polynomial kernel (LMIX3-SVR) can be developed to predict the IC(_{50}) of novel CatL inhibitors. The model's performance is optimized using the Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm and rigorously validated via 5-fold and leave-one-out cross-validation (R² > 0.96). This model can rapidly predict the activity of hundreds of newly designed compounds, significantly accelerating the lead identification process [5].

Signaling Pathways Regulated by Cathepsin L

The following diagram illustrates the central role of Cathepsin L in promoting cancer stemness and multidrug resistance, as revealed in recent studies.

Figure 1: CTSL Drives Stemness and Chemoresistance via the HGF/Met Axis. Cathepsin L transcriptionally upregulates HGFAC, leading to activation of the HGF/Met signaling pathway. Downstream PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling promotes the expression of stemness factors, survival proteins, and drug efflux pumps, collectively inducing a multidrug-resistant phenotype.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Cathepsin L in Cancer Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CTSL siRNA | Gene silencing to study loss-of-function phenotypes. | Validating the role of CTSL in stemness and drug sensitivity in spheroid models [3]. |

| Specific CTSL Inhibitors | Pharmacological blockade of CTSL protease activity. | In vivo combination therapy with chemotherapy (e.g., Docetaxel) to overcome resistance [3]. |

| Clickable Photo-Crosslinking Probe | Chemical proteomics to identify direct molecular targets of drugs. | Identifying CTSL as the direct binding target of Hydroxychloroquine [4]. |

| Anti-CTSL Antibody | Detection of CTSL protein expression via Western Blot, Immunohistochemistry. | Correlating high CTSL levels with poor prognosis in patient tissue samples [2] [3]. |

| ML/SBVS Computational Pipeline | In silico screening of large compound libraries to identify novel inhibitors. | Discovery of natural compound inhibitors like ZINC4097985 with high predicted binding affinity [2]. |

Cathepsin L has emerged as a master regulator of cancer progression, metastasis, stemness, and multidrug resistance, with additional implications in infectious disease. Its multifaceted roles, particularly in activating the HGFAC/HGF/Met axis and modulating the tumor immune landscape, make it a compelling therapeutic target. While challenges remain in developing specific, clinically effective inhibitors, integrated research strategies combining robust in vitro and in vivo models with advanced computational methods like machine learning and QSAR modeling are accelerating drug discovery. Future work should focus on translating these promising pre-clinical findings into targeted therapies that can disrupt the pathogenic functions of CTSL and improve patient outcomes in cancer and beyond.

In the realm of computer-aided drug discovery, molecular descriptors serve as the fundamental link between a compound's chemical structure and its predicted biological activity and physicochemical properties. Among the vast array of available descriptors, three have consistently proven critical for predicting compound behavior: hydrogen bond donors (HBD), rotatable bonds (nRotB), and lipophilicity (most commonly measured as LogP or LogD). These descriptors provide crucial insights into a molecule's ability to permeate membranes, interact with biological targets, and exhibit favorable pharmacokinetic profiles. The strategic selection of these features is paramount, particularly in specialized research contexts such as the development of anti-cathepsin agents, where the balance between molecular complexity, flexibility, and permeability dictates therapeutic potential. This guide objectively compares the predictive performance of models utilizing these key descriptors, with a specific focus on evaluating Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) versus Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for feature selection within anti-cathepsin activity prediction research. The analysis synthesizes experimental data and methodologies from recent studies to provide researchers with a validated framework for descriptor selection and model optimization.

Critical Molecular Descriptors in Drug Discovery

Molecular descriptors quantitatively capture key physicochemical properties that govern a compound's behavior in biological systems. The following table summarizes the three focal descriptors of this review, their recommended values, and their impact on drug-like properties.

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors and Their Significance in Drug Discovery

| Descriptor | Recommended Value | Average in Marketed Drugs | Impact on Drug Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBD (Hydrogen Bond Donors) | ≤ 5 [6] | 1.9 [6] | Impacts permeability and absorption; lower counts generally improve cell membrane penetration [6]. |

| nRotB (Number of Rotatable Bonds) | ≤ 10 [6] | 4.9 [6] | Reflects molecular flexibility; influences oral bioavailability and binding entropy [6]. |

| Lipophilicity (clogP/LogD) | 1-3 [6] | clogP: 3; LogD7.4: 1.59 [6] | Critical for solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability; excessively high values correlate with promiscuity and toxicity [6]. |

The predictive power of these descriptors is consistently demonstrated across diverse research domains. In a study focused on predicting inhibitors of HIV integrase, a critical antiviral target, these descriptors were engineered as input features for machine learning models. The resulting random forest model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC-ROC) of 0.886 and an accuracy of 81.5%, underscoring the utility of these fundamental properties in classifying bioactive compounds [7]. Furthermore, research into quercetin analogues aimed at improving blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability utilized principal component analysis (PCA) and identified descriptors related to intrinsic solubility and lipophilicity (LogP) as the primary factors responsible for clustering compounds with the most favorable permeability profiles [8]. This evidence reinforces the role of these core descriptors in predicting central pharmacokinetic parameters.

Feature Selection Methodologies: RFE vs. PCA

The process of selecting the most relevant molecular descriptors from a high-dimensional feature space is a critical step in building robust and interpretable predictive models. Two prominent methodologies for this task are Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is an iterative, model-driven feature selection technique. It begins by training a model on all available features, ranking the features based on their importance (e.g., coefficients for linear models or feature importance for tree-based models), and then eliminating the least important feature(s) [9] [10]. This process repeats until an optimal subset of features is identified. For instance, in a study to predict human pregnane X receptor (PXR) activators, RFE coupled with a random forest classifier was used to define an optimal subset from 208 molecular descriptors and multiple fingerprints, which subsequently led to a high-performance model [10].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA), in contrast, is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms the original features into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs) [8]. These PCs are linear combinations of the original features and are ordered such that the first few capture the majority of the variance in the dataset [8]. While not a feature selector in the traditional sense, PCA allows researchers to identify the original molecular descriptors that contribute most significantly to the most informative PCs, thereby revealing the underlying structural properties driving the observed variance [9] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for applying RFE and PCA in a molecular descriptor selection pipeline.

Feature Selection Workflow: RFE vs. PCA

Comparative Analysis in Anti-Cathepsin Research

The broader thesis on feature selection methodologies finds a specific and relevant application in the prediction of anti-cathepsin activity. A comparative analysis of preprocessing methods for molecular descriptors in this domain explicitly identified RFE, forward selection, backward elimination, and stepwise selection as key techniques for optimizing predictive models [11]. While the specific quantitative results for anti-cathepsin models are not detailed in the available literature, performance data from comparable drug discovery applications provide a robust proxy for understanding their relative merits.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RFE and PCA in Predictive Modeling

| Research Context | Feature Selection Method | Key Selected Descriptors / Components | Model Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| PXR Activator Classification [10] | RFE with Random Forest | An optimal subset of RDKit descriptors and fingerprints. | XGBoost model with selected features achieved an AUC of 0.913 (training) and 0.860 (external test). |

| RPLC Retention Time Prediction [9] | PCA-based Strategy | MDs most correlated with the first principal component (PC1). | The PCA-based model's performance was comparable to other methods, with the study concluding RFE and Lasso offered slight advantages. |

| RPLC Retention Time Prediction [9] | RFE | 16 descriptors including maxtsC, MWC2, nN, k2. |

The model built with RFE-selected features demonstrated strong performance, with the study noting that RFE and Lasso provided the best results. |

| HIV Integrase Inhibition [7] | RFE with Random Forest | Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), Molecular Weight (MW), LogP. | Random Forest model achieved an AUC-ROC of 0.886 and accuracy of 81.5%. |

The experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that RFE tends to produce models with superior predictive accuracy for specific biological endpoints. This is attributed to its model-centric approach, which directly selects features based on their contribution to predicting the target variable [9] [7] [10]. In contrast, PCA is highly valuable for understanding the intrinsic structure of the chemical data and mitigating multicollinearity, as it prioritizes the overall variance in the descriptor data, which may not always align perfectly with variance related to the specific activity being predicted [9] [8]. For anti-cathepsin research, where the primary goal is often to build a highly accurate classifier or predictor, RFE emerges as the more directly advantageous technique.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementing the aforementioned methodologies, this section outlines detailed experimental protocols derived from the cited literature.

Protocol 1: RFE for Molecular Descriptor Selection

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in PXR activator and HIV integrase inhibitor prediction studies [7] [10].

Data Curation and Calculation of Descriptors:

- Collect a dataset of chemical structures with associated experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC50 for anti-cathepsin activity).

- Standardize molecular structures (e.g., using RDKit) by removing salts, neutralizing charges, and generating canonical SMILES strings.

- Calculate an initial, comprehensive set of 1D and 2D molecular descriptors (e.g., using RDKit, ChemDes, or ACD software). HBD, nRotB, and LogP should be included in this initial set [9] [7].

Data Preprocessing:

- Remove descriptors with constant values or zero variance across the dataset.

- Handle missing values, either by imputation or removal of the offending descriptors/compounds.

- Split the curated dataset into a training set (typically 80%) and a hold-out test set (20%) using stratified sampling to maintain class balance.

Recursive Feature Elimination:

- Initialize a machine learning algorithm (e.g., Random Forest or Logistic Regression) on the training set.

- Use the RFE class from a library such as Scikit-learn, specifying the model and the desired number of final features.

- The RFE process will: a. Fit the model on the current set of features. b. Rank all features by their importance (e.g., Gini importance for Random Forest). c. Prune the least important feature(s). d. Repeat steps a-c until the target number of features is reached.

- The output is an optimized, ranked list of molecular descriptors.

Model Training and Validation:

- Train the final predictive model using only the features selected by RFE.

- Evaluate model performance on the hold-out test set using metrics such as AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, and recall [7].

Protocol 2: PCA for Descriptor Analysis and Selection

This protocol is based on approaches used in QSRR modeling and analysis of quercetin analogues [9] [8].

Data Preparation and Standardization:

- Follow the same data curation and descriptor calculation steps as in Protocol 1.

- Crucially, standardize the descriptor data by scaling each feature to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one. This is essential for PCA, which is sensitive to variable scales.

Principal Component Analysis:

- Apply PCA (e.g., using Scikit-learn) to the standardized training set descriptor matrix.

- Retain the number of principal components (PCs) that capture a sufficiently high percentage (e.g., >95%) of the cumulative variance in the data, or based on the scree plot inflection point.

Identification of Key Descriptors:

- Analyze the loadings (coefficients) of the original descriptors for the first few PCs. Each loading represents the contribution of a descriptor to a PC.

- Identify the original molecular descriptors that have the highest absolute loadings on the first one to three PCs. These are the descriptors that contribute most significantly to the major axes of variance in the dataset [8]. For example, in the study of quercetin analogues, LogP was found to be a primary contributor to the PCs associated with BBB permeability [8].

Model Building and Interpretation:

- Either use the top PCs as new, uncorrelated features for model training, or use the analysis to select a subset of the original, high-loading descriptors (e.g., HBD, nRotB, LogP) for building a more interpretable model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key software tools and computational resources essential for implementing the experimental protocols and calculating molecular descriptors.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Software for Descriptor-Based Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [7] [10] | Open-source Cheminformatics Library | Calculates 1D/2D molecular descriptors (e.g., HBD, nRotB, TPSA) and fingerprints from structures. | Used for feature engineering in model development for HIV integrase and PXR activator prediction. |

| Scikit-learn [7] [10] | Python ML Library | Provides implementations of RFE, PCA, and machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, SVM, etc.). | Core library for building and evaluating the predictive models. |

| ChemDes [9] | Online Platform | Computes a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (1,834+). | Used in QSRR studies to generate a wide array of descriptors for retention time prediction. |

| ACD/Percepta [9] | Commercial Software | Calculates physicochemical properties like LogP and LogD. | Employed in studies requiring accurate lipophilicity predictions. |

| Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT) [12] | Automated Machine Learning Tool | Automates the process of model selection and hyperparameter tuning. | Used to develop interpretable models without sacrificing accuracy for properties like melting point. |

In the field of modern bioinformatics and drug discovery, researchers routinely face datasets where the number of features (such as genes, proteins, or metabolites) vastly exceeds the number of samples. This phenomenon, known as the "curse of dimensionality," presents significant challenges for building accurate predictive models [13]. Excessive features can lead to overfitting, where models perform well on training data but fail to generalize to new data [14]. This is where feature selection becomes indispensable.

Feature selection is the process of automatically selecting the most relevant and non-redundant subset of features from the original data for use in model construction [14] [13]. For researchers working on high-dimensional bioactivity data—such as predicting anti-cathepsin activity or other drug-target interactions—implementing robust feature selection is not merely an optimization step; it is a foundational component of building biologically meaningful and clinically translatable models.

RFE vs. PCA: Core Methodologies Compared

Two predominant approaches for tackling high-dimensional data are Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA). While both aim to reduce dimensionality, their underlying philosophies and outputs differ significantly.

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

RFE is a wrapper-type feature selection method that works by recursively constructing a model (e.g., SVM or Random Forest), removing the least important feature(s) based on model-derived criteria, and then repeating the process with the remaining features until the optimal subset is identified [14].

- Mechanism: It operates through a backward elimination process, prioritizing features that contribute most to the model's predictive power.

- Output: A subset of the original features, preserving their biological interpretability. This allows researchers to pinpoint specific genes or proteins, such as Cathepsin S, for further experimental validation [15].

- Advantage: High performance in selecting features that lead to excellent classification accuracy [14].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that transforms the original features into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components [16].

- Mechanism: It creates new features as linear combinations of the original ones, maximizing the variance captured in the data.

- Output: A set of synthetic components. While these components effectively reduce redundancy, they are often not biologically interpretable, as they do not correspond to individual, measurable biological entities [16].

- Advantage: Effectively handles feature dependencies and multicollinearity.

Table 1: Core Comparison Between RFE and PCA

| Aspect | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Category | Wrapper Method | Feature Transformation |

| Core Mechanism | Recursively removes least important features | Creates new, uncorrelated components from original features |

| Primary Output | Subset of original, interpretable features | Synthetic components (linear combinations) |

| Biological Interpretability | High | Low |

| Model Dependency | Yes, requires an estimator (e.g., SVM, Logistic Regression) | No, it is unsupervised |

| Handling Multicollinearity | Dependent on the base model | Excellent |

Experimental Data: A Case Study in Predictive Accuracy

The theoretical advantages of RFE are borne out in experimental data. A study investigating the impact of acetyl tributyl citrate (ATBC) on erectile dysfunction (ED) successfully identified Cathepsin S (CTSS) as a critical regulator. This discovery was made by integrating network toxicology with machine learning models, underscoring the power of feature selection to pinpoint biologically relevant targets [15].

Further independent research directly compares the performance of different feature selection strategies. One study proposed a hybrid method (PFBS-RFS-RFE) that combines Random Forest feature importance with RFE. This method demonstrated superior performance on RNA gene datasets, achieving near-perfect classification metrics [14].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods in Cancer Classification

| Study Focus | Feature Selection Method | Classifier | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAD Classification [17] | Bald Eagle Search Optimization (BESO) | Random Forest | 92% Accuracy |

| Cancer Classification [14] | PFBS-RFS-RFE (Hybrid RFE) | Multiple | 99.99% Accuracy, 1.000 ROC Area |

| Prostate Cancer [18] | Filter + Wrapper + Embedded | Random Forest | Outperformed SVM, k-NN, and ANN |

| Various Cancers [14] | Standard RFE | Logistic Regression | High Performance, but prone to over-fitting |

The data consistently shows that advanced wrapper methods, particularly those based on or enhancing RFE, can achieve exceptional accuracy. Moreover, Random Forest consistently emerges as a powerful classifier that, when paired with effective feature selection, delivers top-tier performance across multiple biological datasets [18] [14] [17].

Essential Workflows and Signaling Pathways

The process of building a predictive model for a target like cathepsin S follows a structured workflow, from raw data to biological insight.

Machine Learning Workflow for Bioactivity Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for creating a predictive model, highlighting the critical role of feature selection.

Simplified Signaling Pathway of ATBC-Induced Erectile Dysfunction

The identification of cathepsin S through feature selection fits into a broader biological pathway. The diagram below summarizes a proposed mechanism linking ATBC exposure to erectile dysfunction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Building a reliable machine learning pipeline for bioactivity prediction requires more than just algorithms. The following table details key resources and their functions, as utilized in the cited research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for ML-Driven Discovery

| Category | Item / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Databases | PubChem, ChEMBL, CTD | Provides chemical structures, target predictions, and known toxicogenomic data for compounds like ATBC [15]. |

| Target Prediction | SwissTargetPrediction, SEA | Predicts potential protein targets of a small molecule based on its structure [15]. |

| Gene Expression Data | GEO (e.g., GSE206528) | Public repository of functional genomics data; primary source for training and testing models [15]. |

| Analysis Tools | R (Caret, FSelector, randomForest) | Core software environment for implementing feature selection algorithms and building predictive models [16]. |

| Validation Tools | STRING Database, Molecular Docking | Validates protein-protein interactions of predicted targets and studies ligand-receptor binding affinities [15]. |

In the context of high-dimensional bioactivity data, the choice of feature selection method is a critical determinant of a project's success. While PCA serves as a valuable tool for visualizing data and reducing technical noise, RFE and its advanced hybrid derivatives offer a direct path to generating biologically interpretable and highly accurate models. The ability to identify specific, actionable targets—such as Cathepsin S in the ATBC study—makes RFE a cornerstone methodology for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate complex datasets into meaningful scientific discoveries.

In the field of machine learning-based drug discovery, feature reduction is an indispensable preprocessing step for managing high-dimensional data, such as molecular descriptors or radiomic features [19]. It enhances model performance by removing noisy, redundant, and noncontributory features, thereby reducing computational cost, mitigating overfitting, and improving generalizability [20] [19]. The two predominant methodological approaches are feature selection, which chooses a subset of the original features, and feature extraction (a form of dimensionality reduction), which creates new, transformed features from the original set [19]. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are flagship techniques from these respective camps. Their core difference is foundational: RFE selects a subset of existing features, preserving their intrinsic meaning and interpretability, while PCA creates a new set of combined features, often at the cost of direct interpretability but with the benefit of maximum information compression [21] [22]. This distinction becomes critically important in domains like anti-cathepsin inhibitor screening, where identifying which specific molecular descriptors contribute to predictive accuracy can be as valuable as the prediction itself [23].

Core Principles

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)

RFE is a supervised wrapper method for feature selection. Its core principle is to recursively construct a model, identify the least important features in the current model, and remove them before the next iteration, thereby refining the feature set towards the most predictive ones [20].

- Mechanism: RFE operates through an iterative, backward elimination process.

- It begins by training a model (e.g., a classifier or regressor) on the entire set of features.

- It then ranks all features based on a defined importance metric (e.g., coefficients in linear models, featureimportances in tree-based models).

- The least important feature(s) are pruned from the feature set.

- This process repeats with the reduced feature set until a predefined number of features remains [20].

- Supervised Nature: As a wrapper method, RFE directly uses the target variable and a machine learning model's performance to guide the selection process. Its sole objective is to find the feature subset that leads to optimal model performance [20].

- Interpretability: A key advantage of RFE is that it preserves the original features, allowing researchers to understand which specific, measurable variables (e.g., specific molecular descriptors) are most predictive of the biological outcome [20] [23].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is an unsupervised dimensionality reduction technique. Its core principle is to transform a set of potentially correlated variables into a new set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components, which are ordered by the amount of variance they capture from the data [20] [19].

- Mechanism: PCA performs a linear transformation of the data.

- It standardizes the data to have a mean of zero and a unit variance.

- It computes the covariance matrix of the data to understand the relationships between features.

- It performs eigendecomposition on this covariance matrix to obtain the eigenvectors (principal components) and eigenvalues (the amount of variance explained by each component).

- The eigenvectors are ranked by their corresponding eigenvalues in descending order.

- The original data is then projected onto the top k eigenvectors to create a lower-dimensional dataset [19].

- Unsupervised Nature: PCA is agnostic to the target variable. It focuses exclusively on the input data's internal structure and maximizes variance, not predictive power for a specific task [21].

- Information Compression: The primary goal of PCA is to compress the information in the original features into a smaller number of new features. However, these new components are linear combinations of all original features, making them difficult to interpret in a domain-specific context [21] [24].

Mechanistic Differences

The fundamental differences between RFE and PCA stem from their opposing approaches to feature reduction. The table below provides a structured comparison of their core mechanics.

Table 1: A mechanistic comparison of RFE and PCA.

| Aspect | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Select the most predictive feature subset [20] | Capture maximum variance via feature transformation [19] |

| Methodology | Iterative model training & backward elimination [20] | Linear algebraic transformation (eigen-decomposition) [19] |

| Nature | Supervised (uses the target variable) [20] | Unsupervised (ignores the target variable) [21] |

| Output | Subset of original features [20] | New features (linear combinations of originals) [19] |

| Interpretability | High (preserves original feature meaning) [20] | Low (new features lack direct biological meaning) [24] |

| Model Dependency | High (relies on a base estimator) [20] | None (statistical, model-agnostic method) [19] |

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the distinct step-by-step processes of each method.

RFE Workflow

PCA Workflow

Performance in Predictive Modeling

General Benchmarking Evidence

A large-scale 2025 benchmarking study in radiomics provides compelling, generalizable evidence on the performance of feature selection versus projection methods. The study evaluated nine feature selection methods (including ET, LASSO, and Boruta) and nine feature projection methods (including PCA and NMF) across 50 binary classification datasets. The results clearly demonstrated that feature selection methods, on average, achieved the highest performance [24].

Table 2: Summary of key findings from the radiomics benchmarking study (Scientific Reports, 2025).

| Metric | Best Performing Methods (Type) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Average AUC | Extremely Randomized Trees (Selection), LASSO (Selection) [24] | Selection methods, particularly ET and LASSO, achieved the highest average AUC [24]. |

| Best Method Frequency | Bhattacharyya (Selection), Factor Analysis (Projection) [24] | Performance was highly dataset-dependent, but no projection method consistently outperformed the top selection methods [24]. |

| PCA Performance | Outperformed by all feature selection methods tested [24] | The commonly used PCA was less effective than all feature selection methods and was the best performer on only one dataset [24]. |

The study concluded that while projection methods can occasionally outperform selection methods on individual datasets, feature selection should remain the primary approach in a typical radiomics study. This conclusion is highly relevant to other high-dimensional, biomarker-oriented fields like drug discovery [24].

Direct Evidence from Anti-Cathepsin Research

Specific research in anti-cathepsin activity prediction aligns with these general findings. A research project focused on predicting the activity of chemical molecules using molecular descriptors successfully applied feature selection techniques like RFE, Forward/Backward Selection, and Gradient Boosting to optimize descriptor selection. The application of these feature elimination techniques was crucial for obtaining an optimal descriptor set. Subsequent training of a 1D CNN model, combined with SMOTE to handle class imbalance, led to a high accuracy of 97% in identifying potent cathepsin inhibitors [23]. This demonstrates the practical efficacy of rigorous feature selection in this specific domain, enabling both high model performance and improved transparency by identifying the key molecular descriptors driving the predictions.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Detailed Methodology for a Comparative Study

To objectively compare RFE and PCA, a nested cross-validation protocol, as used in the cited radiomics study, is recommended to ensure unbiased performance estimation [24].

- Dataset Preparation: A collection of 50 binary classification radiomic datasets derived from CT and MRI was used. Evaluation was performed using nested, stratified 5-fold cross-validation with 10 repeats [24].

- Feature Reduction Application:

- RFE Pathway: Apply RFE with a chosen estimator (e.g., Logistic Regression or SVM). The number of features to select can be determined via an inner cross-validation loop.

- PCA Pathway: Apply PCA to the training fold. The number of components can be set to retain a pre-defined proportion of variance (e.g., 95%) or be optimized via inner cross-validation.

- Model Training and Evaluation: After feature reduction is applied to the training fold, a classifier (e.g., Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest) is trained. The model is then evaluated on the left-out test fold. Performance metrics such as Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC), Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), and F-scores (F1, F0.5, F2) are calculated [24].

- Comparison and Statistical Testing: Model performances across all datasets and folds are aggregated. A Friedman test can determine if there are significant differences among the methods, followed by a post-hoc Nemenyi test for pairwise comparisons [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key components required for conducting a rigorous comparative analysis of feature reduction methods in a bioinformatics or drug discovery context.

Table 3: Key research reagents, tools, and their functions for comparative feature reduction studies.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors | Quantifiable properties of chemical structures that serve as the high-dimensional input features for models predicting biological activity (e.g., anti-cathepsin inhibition) [23]. |

| Experimentally Validated Bioactivity Datasets | Publicly available databases (e.g., IEDB, ChEMBL) providing curated positive and negative samples for model training and validation [25]. |

| Scikit-learn (Sklearn) Library | A core Python ML library providing implemented implementations of both RFE and PCA, along with a wide array of models and evaluation metrics [20]. |

| Cross-Validation Framework | A resampling procedure (e.g., stratified k-fold) used to reliably estimate model performance and tune hyperparameters without data leakage [24]. |

| Performance Metrics (AUC, AUPRC, F1) | Standard metrics for evaluating and comparing classifier performance, with AUPRC being particularly informative for imbalanced datasets [24]. |

The mechanistic distinction between RFE and PCA is clear and carries significant implications for predictive modeling in research. RFE, as a supervised feature selection method, is fundamentally geared towards optimizing predictive accuracy by identifying and retaining the most relevant original features. This makes it exceptionally valuable in domains like anti-cathepsin prediction, where interpretability is crucial and the link between specific molecular descriptors and biological activity is a key research insight [23]. PCA, as an unsupervised dimensionality reduction technique, excels at compressing data and mitigating multicollinearity by creating new, orthogonal features that capture maximum variance.

The prevailing experimental evidence, including a comprehensive 2025 benchmarking study, indicates that feature selection methods like RFE generally achieve superior predictive performance compared to projection methods like PCA [24]. This is likely because selection methods directly leverage the relationship between features and the target variable, while PCA operates blindly to the prediction task. Therefore, for researchers and scientists in drug development, RFE and related feature selection techniques should be considered the primary approach for building interpretable and high-performing predictive models. However, given the dataset-dependent nature of performance, testing both paradigms within a rigorous nested cross-validation framework remains a prudent and recommended strategy.

Implementing RFE and PCA: A Step-by-Step Guide for Anti-Cathepsin Modeling

For researchers in drug discovery, predicting the interaction between a chemical compound and its biological targets is a fundamental challenge. The accuracy of such predictions heavily depends on the quality of the underlying bioactivity data and the sophisticated preprocessing of chemical descriptors before model training. This guide objectively compares the process of sourcing and utilizing data from two major public bioactivity resources—ChEMBL and the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB). The analysis is framed within a specific research context: evaluating the performance of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) against Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for enhancing prediction accuracy in anti-cathepsin research. The focus lies on the practical aspects of data acquisition, curation, and feature engineering that are crucial for building robust machine-learning models.

The first step in any computational drug discovery project is selecting the appropriate database. The table below compares two pivotal resources for bioactivity data.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of ChEMBL and IEDB

| Feature | ChEMBL | IEDB |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Bioactive drug-like small molecules & their targets [26] [27] | Immune epitopes for infectious, allergic, and autoimmune diseases |

| Key Data Types | - 2D compound structures- Bioactivity values (e.g., IC50, Ki)- Calculated molecular properties- Target information [27] [28] | - Antibody & T-cell epitopes- Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) binding data- Assay context information |

| Data Volume | >2.2 million compounds; >18 million bioactivity records [27] | Highly curated, context-specific immunological data |

| Main Applications | - Target identification/fishing- Polypharmacology prediction- Drug repositioning [29] [28] | - Vaccine design- Immunodiagnostic development- Understanding immune-mediated disease mechanisms |

Data Acquisition and Curation Protocols

Sourcing Data from ChEMBL

ChEMBL is a manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, making it the primary resource for a project focused on small-molecule inhibitors like anti-cathepsin compounds [27] [28]. The typical workflow involves:

- Data Retrieval: Bioactivity data can be accessed via a web interface, data downloads, or API endpoints [28] [30]. For anti-cathepsin activity, you would search for the specific cathepsin protein targets (e.g., Cathepsin B, S, K).

- Critical Curation and Filtering: To build a reliable dataset for model training, a rigorous filtering strategy is essential. A standard protocol, as used in recent predictive models, includes [29]:

- Selecting only assays reporting IC50 values.

- Converting all units to a consistent measure (e.g., micromolar,

μM). - Handling duplicate compound-target pairs by computing the median absolute deviation for outlier detection and using the median IC50 value.

- Defining an activity cutoff (e.g.,

IC50 <= 10 μMfor active associations andIC50 > 10 μMfor inactive ones) to create a binary classification problem.

This curated data from ChEMBL provides the foundational features (molecular descriptors) and labels (active/inactive) for the subsequent machine-learning task.

Sourcing Data from IEDB

While IEDB is less directly relevant for small-molecule drug discovery, it is an indispensable resource for immunological research. Its data acquisition process is centered on epitope-related information. The general workflow involves querying the database for specific antigens, organisms, or immune responses, followed by filtering results based on assay type (e.g., MHC binding, T-cell response) and host organism.

Experimental Framework: RFE vs. PCA in Anti-Cathepsin Prediction

This section details the core experimental methodology for comparing feature preprocessing techniques, using anti-cathepsin activity prediction as a case study.

Research Context and Objective

The "curse of dimensionality" is a significant challenge in building Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. Molecular descriptors can number in the thousands, making models prone to overfitting and computationally expensive [22] [31]. Feature selection and dimensionality reduction are two preprocessing strategies to mitigate this.

- Feature Selection (e.g., RFE): Identifies and retains the most important features from the original set. It maintains interpretability, as the original molecular descriptors are preserved [11].

- Dimensionality Reduction (e.g., PCA): Transforms the original features into a new, smaller set of components that capture the most critical information (like variance). This can lead to loss of interpretability as the new components are linear combinations of the original features [22].

The objective is to empirically determine which method, RFE or PCA, yields superior model accuracy in predicting anti-cathepsin activity from ChEMBL-derived molecular descriptors.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow outlines the end-to-end process from data acquisition to model evaluation.

Key Experimental Steps:

- Data Preparation: Following the ChEMBL curation protocol in Section 3.1, a high-quality dataset for a specific cathepsin target is compiled. Molecular descriptors (e.g., ECFP, MACCS) are computed for each compound [29].

- Dataset Splitting: The curated data is split into training and testing sets to ensure unbiased evaluation.

- Preprocessing Application:

- RFE Pathway: RFE is a "wrapper" method that recursively removes the least important features based on model weights (e.g., from a Support Vector Machine) until the optimal number is reached [32] [11].

- PCA Pathway: PCA is applied as an unsupervised "feature reduction" method. It transforms the original descriptors into a set of linearly uncorrelated principal components that capture the maximum variance [22].

- Model Training & Evaluation: A classifier (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) is trained on both the RFE-selected features and the PCA-transformed data. Model performance is evaluated on the held-out test set using metrics like accuracy and F1-score.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below synthesizes findings from the literature on the performance of RFE and PCA in similar bioactivity prediction contexts.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RFE and PCA in Bioactivity Modeling

| Criterion | RFE (Feature Selection) | PCA (Dimensionality Reduction) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Selects a subset of original features by recursively pruning least important ones [32] [11]. | Projects data into lower-dimensional space using orthogonal components of maximum variance [22]. |

| Model Performance | Often outperforms PCA when coupled with nonlinear models; one study showed R-squared of 0.7685 for Naive Bayes [11]. | Can be outperformed by RFE; may lead to overfitting on wide data if global variance includes noise [31]. |

| Interpretability | High. Retains original molecular descriptors, allowing for clear SAR insights [22] [11]. | Low. Transforms features into new components, obscuring original chemical meaning [22]. |

| Computational Load | Higher cost due to iterative model training during feature elimination [31]. | Generally faster, as it relies on linear algebraic decomposition [22]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Prioritizing model interpretability and identifying key molecular drivers of activity [11]. | Maximizing computational efficiency when interpretability is not the primary concern [22]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Building and testing a predictive model for anti-cathepsin activity requires a suite of computational and data resources.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for Computational Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Description | Relevance to Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules and assay data [26] [27]. | Primary source for bioactivity data (e.g., IC50 values) and compound structures. |

| Molecular Descriptor Software (e.g., RDKit) | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics. | Calculates numerical descriptors (e.g., ECFP, MACCS) from compound structures for machine learning [29]. |

| RFE Algorithm | A wrapper feature selection method available in libraries like scikit-learn. | Identifies the most predictive molecular descriptors by recursively pruning features [32] [11]. |

| PCA Algorithm | A linear dimensionality reduction technique available in libraries like scikit-learn. | Reduces the dimensionality of the molecular descriptor space to improve model efficiency [22]. |

| Machine Learning Library (e.g., scikit-learn) | Provides a unified interface for classification algorithms and model evaluation tools. | Used to train predictive models (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) and assess their performance [29] [32]. |

Calculating and Standardizing Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints

In modern computational drug discovery, the accurate prediction of biological activity relies heavily on the effective transformation of chemical structures into numerical representations. This process is paramount in targeting cysteine cathepsins, proteases identified as crucial therapeutic targets for conditions ranging from osteoporosis to SARS-CoV-2 infection [33] [34]. The selection of optimal molecular descriptors and fingerprints, followed by robust feature selection techniques, forms the backbone of predictive Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. Within this context, a central thesis has emerged: For anti-cathepsin activity prediction, wrapper-based feature selection methods, particularly Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), yield superior model accuracy and interpretability compared to linear transformation techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), by preserving critical chemical information relevant to protease inhibition.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of software tools for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints, and evaluates the performance of subsequent feature selection strategies, focusing on their application in cathepsin inhibitor development.

Molecular Descriptor and Fingerprint Calculation Platforms

A diverse array of software libraries exists for calculating molecular descriptors and fingerprints, each with distinct strengths, descriptor counts, and operational characteristics. The choice of platform significantly influences the feature space available for model building.

Table 1: Comparison of Molecular Descriptor and Fingerprint Calculation Software

| Software Platform | Descriptor Count | Key Features | License | Primary Interface |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOPtools [35] | Extensive Array (Unified API) | Descriptor calculation, hyperparameter optimization, and QSPR model building; Specialized for reaction modeling. | Freely Available | Python library & Command Line |

| Mordred [36] | >1800 2D & 3D Descriptors | High calculation speed, can handle very large molecules; automated preprocessing. | BSD License | Python library, CLI, & Web UI |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [36] | 1875 Descriptors & Fingerprints | Graphical User Interface; Command Line Interface. | Freely Available | GUI, CLI, KNIME |

| RDKit [35] [37] | Core Descriptor Set & Fingerprints | De facto standard for cheminformatics; includes Morgan fingerprints. | Freely Available | Python library |

| Dragon [36] | Extensive (Proprietary) | Widely used, many descriptors; commercial software. | Proprietary | GUI, CLI |

Beyond the calculation of basic descriptors, molecular fingerprints are topological representations that capture substructural patterns. The Morgan fingerprint (also known as Circular fingerprints), calculated by the RDKit library, has demonstrated exceptional performance in capturing olfactory cues in benchmark studies, outperforming functional group and classical molecular descriptor sets [37]. This highlights the critical importance of selecting an appropriate molecular representation for the specific prediction task.

Experimental Comparison of RFE and PCA for Anti-Cathepsin Prediction

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To objectively evaluate the core thesis, we analyze published experimental protocols that benchmark RFE and PCA for building predictive models of cathepsin inhibition.

Protocol 1: QSAR Modeling of Cathepsin L Inhibitors using Hybrid SVR [33]

- Objective: Predict the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) of peptidomimetic analogues against Cathepsin L (CatL), a target for blocking SARS-CoV-2 viral entry.

- Descriptors: A total of 604 molecular descriptors were computed using CODESSA software.

- Feature Selection & Modeling: Heuristic Method (HM) was used to select the five most critical descriptors. A hybrid Support Vector Regression (SVR) model with a triple kernel (LMIX3-SVR) integrating linear, radial basis, and polynomial functions was then developed.

- Validation: Model robustness was evaluated through five-fold cross-validation and leave-one-out cross-validation.

Protocol 2: Selectivity Classification of Cathepsin K/S Inhibitors using Self-Organizing Maps (SOM) [34]

- Objective: Classify compounds as selective for Cathepsin K (K/S), selective for Cathepsin S (S/K), or non-selective (KS).

- Fingerprints: Two types of 2D structural fingerprints—MACCS and BAPs—were used as molecular representations.

- Feature Selection & Modeling: The Self-Organizing Map (SOM), an unsupervised clustering algorithm, was used to project high-dimensional fingerprint data into a 2D space, grouping compounds based on structural similarity and selectivity profile.

- Validation: Model purity was assessed by analyzing clusters composed exclusively of compounds with a specific selectivity profile.

Protocol 3: Benchmarking Machine Learning for Odor Prediction [37]

- Objective: Benchmark machine learning models for predicting fragrance odors from molecular structure.

- Fingerprints/Descriptors: Compared Functional Group (FG) fingerprints, classical Molecular Descriptors (MD), and Morgan structural fingerprints (ST).

- Modeling: Three tree-based algorithms—Random Forest (RF), XGBoost (XGB), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM)—were trained for multi-label classification.

- Validation: Models were evaluated using stratified five-fold cross-validation, with performance measured by Area Under the Receiver Operating Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC).

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow common to these experimental protocols, from chemical structure to validated predictive model:

Comparative Performance Data

The performance of cathepsin prediction models is highly dependent on the chosen algorithm and feature selection strategy. The table below summarizes key quantitative results from the cited studies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of Various Models in Cathepsin and Cheminformatics Studies

| Study Focus | Model / Algorithm | Key Performance Metrics | Feature Selection / Input |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin L Inhibition [33] | LMIX3-SVR (Triple Kernel) | R²training = 0.9676, R²test = 0.9632, RMSEtest = 0.0322 | Heuristic Method (5 descriptors) |

| Cathepsin L Inhibition [33] | Heuristic Method (HM) | R²training = 0.8000, R²test = 0.8159, RMSEtest = 0.0764 | Heuristic Method (5 descriptors) |

| Cathepsin K/S Selectivity [34] | SOM (MACCS Fingerprints) | Coverage: 97%, Correct Classification: 86% | MACCS Structural Fingerprints |

| Cathepsin K/S Selectivity [34] | SOM (BAPS Fingerprints) | Coverage: 94%, Correct Classification: 76% | BAPS Structural Fingerprints |

| Odor Prediction [37] | XGBoost with Morgan Fingerprints | AUROC = 0.828, AUPRC = 0.237 | Morgan (Structural) Fingerprints |

| Odor Prediction [37] | XGBoost with Molecular Descriptors | AUROC = 0.802, AUPRC = 0.200 | Classical Molecular Descriptors |

Analysis of Feature Selection Methodologies: RFE vs. PCA

The debate between RFE and PCA is central to optimizing QSAR models. These techniques represent fundamentally different approaches to dimensionality reduction.

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): An embedded/wrapper method that recursively removes the least important features based on model weights (e.g., from SVM or Random Forest) to find the optimal subset that maximizes predictive performance [38]. It preserves the original, interpretable features.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A filter method that transforms the original features into a new set of uncorrelated variables (principal components) that are linear combinations of the original data [16]. This often comes at the cost of direct feature interpretability.

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for choosing between these two feature selection strategies in a cheminformatics pipeline:

For anti-cathepsin research, where understanding which structural features contribute to potency and selectivity is paramount for lead optimization, RFE is generally the preferred approach. By retaining the original molecular descriptors, RFE allows researchers to identify specific chemical moieties influencing activity. For instance, the Heuristic Method effectively identified five key descriptors for CatL inhibition, including "Relative number of rings" and "Max PI-PI bond order," providing concrete chemical insights [33]. In contrast, while PCA can sometimes help improve raw prediction accuracy by eliminating multicollinearity, its transformed components are often uninterpretable, limiting their utility for guiding chemical synthesis [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of the workflows described requires a suite of reliable software tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software Solutions

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOPtools [35] | Python Library | Unified descriptor calculation & model optimization. | Simplifies pipeline from descriptors to optimized QSPR models, especially for reactions. |

| Mordred [36] | Descriptor Calculator | Calculates >1800 2D/3D molecular descriptors. | High-speed, comprehensive descriptor calculation for QSAR model building. |

| RDKit [35] [37] | Cheminformatics Library | Fundamental cheminformatics functions and fingerprint calculation. | The foundational library for handling chemical structures and calculating Morgan fingerprints. |

| Scikit-learn [35] | Python Library | Machine learning algorithms (SVM, RF) and model validation. | Implementing RFE, PCA, and training final predictive models with cross-validation. |

| CODESSA [33] | Descriptor Software | Calculates a wide range of molecular descriptors. | Used in QSAR studies to generate a large pool of initial descriptors for feature selection. |

| XGBoost [35] [37] | Machine Learning Library | Gradient boosting framework for classification/regression. | Building high-performance predictive models that can handle complex, non-linear relationships. |

The calculated choice of molecular representation—be it classical descriptors or topological fingerprints—and the subsequent feature selection strategy are pivotal in developing robust QSAR models for cathepsin inhibition. Evidence from recent research supports the thesis that Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) provides a more effective pathway for anti-cathepsin modeling compared to Principal Component Analysis (PCA). RFE's superiority stems from its ability to maintain a direct link between model predictions and chemically interpretable structural features, such as ring counts and bond orders, which is indispensable for rational drug design. While PCA remains a valuable tool for managing multicollinearity and visualization, its loss of chemical interpretability often limits its practical utility in this domain. For researchers aiming to accelerate the discovery of novel cathepsin inhibitors, a workflow leveraging comprehensive descriptor calculators like Mordred or DOPtools, followed by RFE-driven feature selection embedded within powerful algorithms like XGBoost or hybrid SVR, represents a state-of-the-art approach that successfully balances predictive accuracy with chemical insight.

In the field of drug development, particularly in the search for novel biomarkers, high-dimensional data presents both an opportunity and a challenge. Feature selection has become an indispensable step for building interpretable and robust predictive models, such as those aimed at anti-cathepsin drug targeting. Among the various techniques available, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) has emerged as a powerful wrapper-style method, especially when combined with the Random Forest (RF) algorithm. RFE operates on a simple yet effective principle: it starts with all available features and iteratively removes the least important ones, refitting the model each time until a predefined number of features remains [39] [40].

This guide provides a detailed objective comparison between the RFE-RF workflow and a common alternative, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), within the context of predictive accuracy research for anti-cathepsin biomarkers. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical toolkits to help researchers and scientists select the most appropriate feature selection strategy for their specific project needs. The core distinction lies in their fundamental objectives: RFE is a feature selection method that preserves the original features' interpretability, while PCA is a feature extraction technique that creates new, transformed components, often at the cost of direct interpretability [41] [42].

Algorithmic Fundamentals: RFE-RF vs. PCA

The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with Random Forest Workflow

RFE wrapped with a Random Forest classifier is a greedy, backward selection algorithm. Its strength lies in its recursive nature, which allows for a continuous re-assessment of feature importance after the removal of the least contributory variables [42]. The algorithm, as implemented in libraries like scikit-learn, is configured with the chosen estimator (a Random Forest in this case) and the number of features to select [39]. The process is ideally encapsulated within a cross-validation pipeline to prevent data leakage and ensure robust performance estimates [39] [43].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the RFE-RF algorithm.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for Dimensionality Reduction

In contrast, PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that works by transforming the original, potentially correlated features into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components [41] [44]. These components are linear combinations of the original features and are ranked in order of the variance they capture from the data [44]. The first principal component (PC1) accounts for the largest possible variance, PC2 for the next largest while being orthogonal to PC1, and so on [41]. The key limitation of PCA in a biomarker context is its lack of direct interpretability; the resulting components are mathematical constructs that do not directly correspond to the original, biologically meaningful features like specific gene expressions or protein sequences [45] [42].

Experimental Comparison: Benchmarking Performance in Predictive Modeling

The following table synthesizes findings from empirical evaluations, including studies on educational and clinical datasets, to highlight the characteristic performance trade-offs between RFE variants and PCA [42].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of RFE Variants vs. PCA in Predictive Modeling

| Method | Predictive Accuracy | Interpretability | Feature Set Size | Computational Cost | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE with Random Forest | High | High (uses original features) | Small to moderate | High | Moderate to High [42] [46] |

| RFE with XGBoost | Very High | High (uses original features) | Small to moderate | Very High | Moderate to High [42] |

| Enhanced RFE | Moderate to High | High (uses original features) | Very Small | Moderate | High [42] |

| PCA + Classifier | Varies, can be lower | Low (transformed components) | Fixed number of components | Low to Moderate | High [42] |

Detailed Experimental Data and Protocols

To provide a concrete example of how these methods are benchmarked, we detail a representative experimental protocol and its outcomes.

Experimental Objective: To compare the classification accuracy and feature selection efficacy of RFE-RF against PCA on a synthetic binary classification problem.

Dataset: A synthetic dataset generated using make_classification from scikit-learn, with 1000 samples, 10 input features (5 informative, 5 redundant), and a random state of 1 for reproducibility [39].

Protocol 1: RFE with Random Forest and Decision Tree Classifier

- Feature Selection: The RFE algorithm was configured with a

DecisionTreeClassifier()as the estimator and set to select the top 5 features. - Model Training: A

DecisionTreeClassifier()was used as the final model on the selected features. - Validation: The entire process was wrapped in a

Pipelineand evaluated usingRepeatedStratifiedKFoldcross-validation (10 folds, 3 repeats) [39]. - Results: The model achieved a mean classification accuracy of 88.6% (standard deviation 3.0%) [39].

Protocol 2: PCA with Logistic Regression

- Feature Extraction: PCA was applied to standardize the data and reduce dimensions. The number of components was set to 2.

- Model Training: A

LogisticRegressionmodel was fit on the transformed training data consisting of the two principal components. - Validation: The dataset was split into 70% training and 30% testing sets [44].

- Results: Performance is reported via a confusion matrix, illustrating the classification outcomes on the test set, though a direct accuracy comparison to the RFE result is not provided in the sourced example [44].

Key Insight: The RFE-RF workflow, while computationally more intensive, directly leverages the model's intrinsic feature importance (e.g., Gini-based Variable Importance Measure) to select a subset of meaningful, original features, leading to high accuracy and full interpretability [39] [47].

The Researcher's Toolkit for RFE-RF Implementation

Successfully implementing an RFE-RF workflow requires specific software tools and libraries. The following table lists essential "research reagent solutions" for this task.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Software Tools

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn (Python) | Provides RFE, RandomForestClassifier, Pipeline, and cross-validation utilities. |

The primary library for implementation; ensures a consistent API and integration of the workflow [39]. |

| caret (R) | Offers the rfe function with resampling-based RFE and pre-defined functions for random forests (rfFuncs). |

Handles the outer layer of resampling to incorporate feature selection variability into performance estimates [43]. |

| ranger (R) | A fast implementation of Random Forests. | Used within caret or standalone to reduce computation time for the multiple model fits required by RFE [46]. |

| optRF (R) | A specialized package for determining the optimal number of trees in a random forest. | Enhances the stability of RFE-RF by ensuring the underlying forest model is robust, leading to more reliable feature importance estimates [46]. |

| StandardScaler | A preprocessing step to standardize features by removing the mean and scaling to unit variance. | Critical for PCA; often beneficial for RF models as well, especially when features are on different scales [44]. |

The choice between RFE-RF and PCA is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather a strategic decision based on research goals. For applications like anti-cathepsin prediction, where understanding which specific biomarkers drive the model is crucial, RFE-RF offers an unparalleled combination of high predictive accuracy and clear interpretability. The iterative, model-guided nature of RFE allows it to select a compact set of biologically relevant features. The main trade-off is its higher computational cost.

Conversely, PCA excels as a pre-processing step for simplifying data structure and mitigating multicollinearity, but its utility is limited when the research question demands direct insight into the original features. Recent trends point towards hybrid methods and enhanced variants of RFE that aim to improve its stability and efficiency, making it an even more powerful tool for biomarker discovery and drug development in the era of high-dimensional biological data [42].

In the field of machine learning and data science, high-dimensional datasets present significant challenges, including increased computational costs, model overfitting, and difficulty in visualization. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a powerful unsupervised linear transformation technique that addresses these challenges by converting correlated features into a set of linearly uncorrelated principal components. This transformation allows researchers to reduce dimensionality while retaining the most critical patterns and variance in the data.

Within pharmaceutical research, particularly in anti-cathepsin drug development, the choice between feature transformation techniques like PCA and feature selection methods such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) can significantly impact prediction model accuracy. This guide provides an objective comparison of PCA's performance against alternative feature selection methods, examining their respective strengths, limitations, and optimal applications within drug discovery pipelines.

Understanding PCA: Core Concepts and Workflow

Theoretical Foundation

Principal Component Analysis operates on a simple yet powerful geometric principle: it identifies the directions (principal components) in which the data varies the most and projects the data onto a new coordinate system aligned with these directions. The first principal component captures the maximum variance in the data, with each succeeding component capturing the next highest possible variance while being orthogonal to the preceding components. This process effectively compresses the dataset while preserving its essential structure [48] [49].

The mathematical foundation of PCA involves several key steps. Initially, data standardization ensures all features contribute equally by transforming them to have zero mean and unit variance. The algorithm then computes the covariance matrix to understand feature relationships, followed by eigenvalue decomposition of this matrix to identify the principal components. The eigenvalues represent the amount of variance captured by each component, while the eigenvectors define the direction of these components [49] [50].

The Standardized PCA Pipeline

A well-structured PCA pipeline consists of methodical steps that transform raw data into its principal components:

- Data Standardization: Standardize the dataset to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one for each feature, ensuring features with larger scales do not disproportionately influence the components [49].

- Covariance Matrix Computation: Calculate the covariance matrix to capture relationships and redundancies between all pairs of features in the standardized data [49] [50].

- Eigenvalue Decomposition: Compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. The eigenvectors represent the principal components (directions of maximum variance), while the eigenvalues indicate the magnitude of variance along each component [49] [50].

- Component Selection: Sort the eigenvalues in descending order and select the top (k) eigenvectors corresponding to the largest eigenvalues to form a projection matrix [49].

- Data Transformation: Project the original standardized data onto the selected principal components to create a transformed dataset with reduced dimensions [49].

Determining Optimal Components