Robust QSAR Modeling: A Guide to Handling Multicollinearity in Molecular Descriptors for Recursive Feature Elimination

Multicollinearity among molecular descriptors presents significant challenges for feature selection in QSAR modeling, particularly when using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE).

Robust QSAR Modeling: A Guide to Handling Multicollinearity in Molecular Descriptors for Recursive Feature Elimination

Abstract

Multicollinearity among molecular descriptors presents significant challenges for feature selection in QSAR modeling, particularly when using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). This comprehensive guide addresses the detection, mitigation, and validation strategies for handling descriptor intercorrelation to build more interpretable and generalizable predictive models. Covering foundational concepts through advanced applications, we explore Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) analysis, gradient boosting integration, and comparative performance evaluation across multiple molecular property prediction tasks. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, this article provides practical methodologies to enhance model robustness while maintaining predictive accuracy in cheminformatics and drug discovery applications.

Understanding Multicollinearity in Molecular Descriptors: Threats to QSAR Model Integrity

Defining Multicollinearity in the Context of Molecular Descriptors

Frequently Asked Questions

What is multicollinearity and why is it a problem in my research? Multicollinearity occurs when two or more independent variables in a model are highly correlated, meaning they share information and explain the same variance in the target variable [1]. In the context of molecular descriptors, this happens when descriptors like molecular weight, hydrophobicity, or the number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors are not independent [2]. This correlation leads to:

- Unreliable and unstable estimates of regression coefficients, making it difficult to determine any one descriptor's individual impact on the model output [3] [1].

- Inflated standard errors for the coefficients of correlated features [1].

- Reduced model interpretability and poor generalization to new, unseen data [3] [1].

How does multicollinearity specifically affect Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE)? RFE is a feature selection method that iteratively removes the least important features to find an optimal subset [4]. Multicollinearity can destabilize this process because:

- The "importance" of a correlated feature can be misleading. If two descriptors are highly correlated, RFE might arbitrarily remove one, even though both carry similar information, leading to an unstable feature subset [4].

- The model's performance metric used to guide RFE can become unreliable due to the inflated variances caused by multicollinearity.

What are the most common methods to detect multicollinearity? You can use several diagnostic tools, often in combination [1]:

| Method | Description | Interpretation / Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation Matrix | A table showing pairwise correlation coefficients between all features [3] [1]. | Coefficients near +1 or -1 indicate high correlation [1]. |

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | Measures how much the variance of a feature's coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity with other features [3] [1]. | A VIF above 5 or 10 is a common rule-of-thumb for severe multicollinearity [4] [3] [1]. |

| Condition Index | A scalar value reflecting the sensitivity of the model to small data changes [1]. | A value above 30 suggests significant multicollinearity [1]. |

| Tolerance | The inverse of VIF (Tolerance = 1/VIF) [3]. | Values near 0 indicate a multicollinearity problem [1]. |

What are the best practices for handling multicollinearity in my dataset? There are multiple strategies, each with trade-offs between interpretability, simplicity, and model performance.

| Strategy | Description | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|

| Remove Features [1] | Manually or automatically (e.g., via RFE) drop one or more correlated features. | You need a simple, interpretable model and can clearly identify redundant descriptors. |

| Transform Features [1] | Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to create new, uncorrelated features (components) that are linear combinations of the original ones. | Maintaining all information is critical, and you are willing to sacrifice some interpretability. |

| Regularize Features [1] | Apply Ridge Regression (shrinks coefficients but never to zero) or Lasso Regression (can shrink coefficients to zero, performing feature selection). | You want to retain all features while reducing the impact of multicollinearity and preventing overfitting. |

Experimental Protocol: Diagnosing and Mitigating Multicollinearity

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for a robust analysis of molecular descriptor data.

1. Data Pre-processing

- Calculate Molecular Descriptors: Use a cheminformatics platform (e.g., RDKit, alvaDesc, Dragon) to generate a wide array of numerical descriptors for your compound dataset [5].

- Scale Features: Standardize or normalize all descriptor values before analysis, as many methods (like regularization) are sensitive to variable scale [1].

2. Detection and Diagnosis

- Compute Correlation Matrix: Calculate the Pearson correlation matrix for all descriptors. Visualize it with a heatmap to quickly identify strongly correlated pairs (e.g., |r| > 0.8 or 0.9).

- Calculate VIF: For each descriptor, calculate the Variance Inflation Factor. A common practice is to iteratively remove the feature with the highest VIF above a threshold (e.g., 10) and recalculate until all VIFs are below the threshold [1].

3. Implementation of Mitigation Strategies

- Option A: Feature Removal via RFE

- Use a supervised learning algorithm (e.g., Support Vector Machine with a linear kernel) as the estimator [4].

- Specify the desired number of features (

n_features_to_select) or let RFE determine it via cross-validation (RFECV). - Fit the RFE model to your data. The

ranking_attribute will show the order of feature elimination, andsupport_will indicate the final selected features [4].

- Option B: Feature Transformation via PCA

- Apply PCA to the scaled descriptor matrix.

- Retain the top k principal components that explain a sufficient amount of the total variance (e.g., 95%).

- Use these new, orthogonal components as features in your downstream predictive model.

- Option C: Feature Regularization via Ridge Regression

- Standardize your features prior to modeling.

- Use cross-validation to find the optimal value for the regularization strength hyperparameter (alpha or lambda).

- Fit the Ridge regression model. The resulting coefficients will be more stable and reliable than those from a standard linear model.

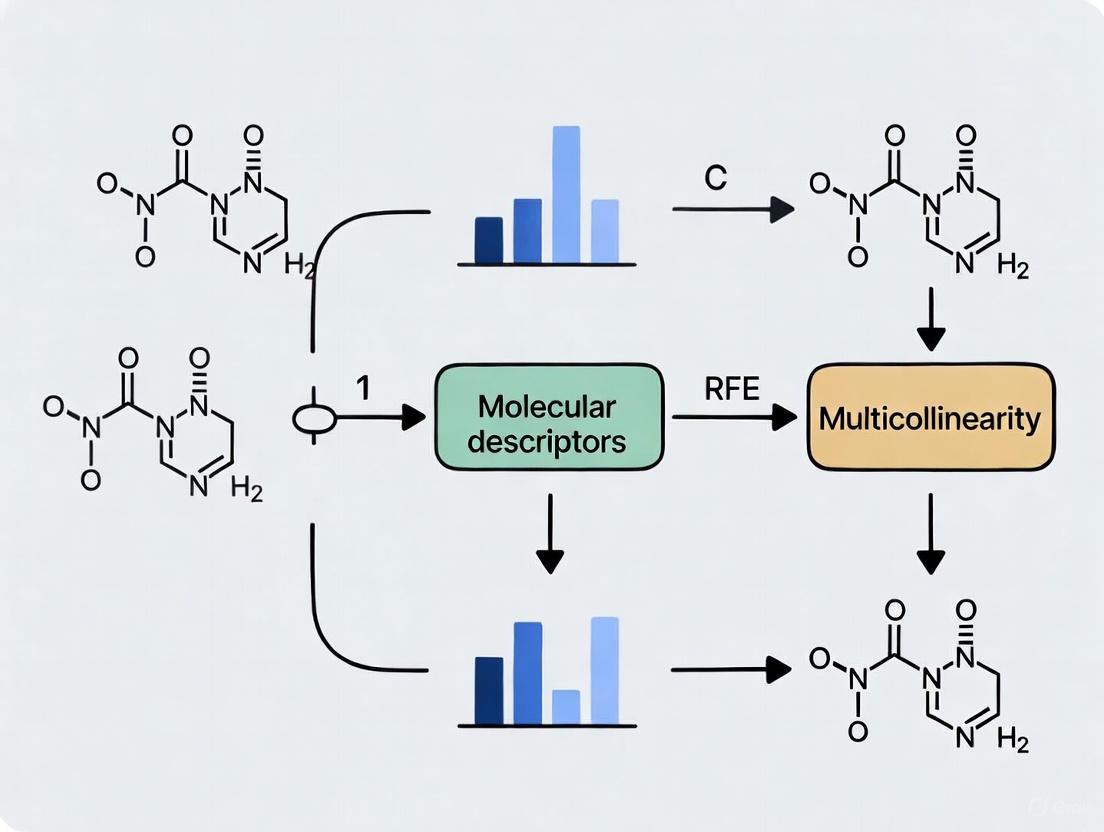

The following workflow summarizes the key steps for diagnosing and treating multicollinearity:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and their functions for handling multicollinearity in molecular descriptor research.

| Tool / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | A key diagnostic metric to quantify the severity of multicollinearity for each feature [3] [1]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | A wrapper method for feature selection that iteratively builds models and removes the weakest features to find an optimal subset [4]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality reduction technique that transforms correlated features into a set of linearly uncorrelated principal components [1]. |

| Ridge Regression | A regularization technique that adds a penalty (L2 norm) to shrink coefficient estimates, improving stability under multicollinearity [3] [1]. |

| Lasso Regression | A regularization technique (L1 norm) that can shrink some coefficients to zero, performing both feature selection and regularization [1]. |

| Scikit-learn (Python) | A comprehensive machine learning library containing implementations for VIF, RFE, PCA, Ridge, and Lasso regression [4]. |

FAQs on Descriptor Intercorrelation

What is descriptor intercorrelation and why is it a problem in QSAR modeling? Descriptor intercorrelation, also known as multicollinearity, occurs when two or more molecular descriptors in a dataset are highly correlated, meaning they provide redundant chemical information. This redundancy poses significant problems for QSAR modeling because it can inflate the variance of model parameter estimates, reduce model stability, and complicate the interpretation of which molecular features truly drive the observed activity or property. While some machine learning methods like Gradient Boosting are inherently more robust to collinearity, it remains a critical issue for many linear models and interpretability-focused studies [6] [7].

What are the common sources of this intercorrelation? Intercorrelation often arises from the fundamental nature of molecular structures. Common sources include:

- Constitutional Redundancy: Descriptors like molecular weight and the number of heavy atoms often scale together with the size of the molecule [8].

- Topological Connectivity: Different topological indices (e.g., Wiener Index, Balaban Index) calculated from the same molecular graph can capture overlapping aspects of molecular branching and connectivity [8] [9].

- Electronic Property Correlation: Electronic descriptors such as partial charges and the HOMO-LUMO gap can be influenced by common underlying electronic effects, leading to correlation [8].

- Descriptor Design: Many 1D, 2D, and 3D descriptors are derived from similar or related mathematical transformations of the molecular structure, inherently creating groups of correlated features [9].

How can I quickly check my dataset for descriptor intercorrelation? A correlation matrix is the most straightforward diagnostic tool. This matrix calculates the Pearson correlation coefficient for every pair of descriptors in your dataset. You can visualize it as a heatmap (Figure 1), where colors indicate the degree of correlation, allowing you to quickly identify highly correlated pairs or blocks of descriptors that may need to be addressed [6].

What is a reasonable correlation threshold for removing descriptors? There is no universally agreed-upon single threshold, as it can be dataset- and goal-dependent. However, studies have investigated the impact of different limits. The table below summarizes findings on how the number of retained descriptors changes with the correlation threshold and the subsequent effect on model performance [7].

Table 1: Impact of Intercorrelation Limits on Descriptor Count and Model Performance

| Absolute Intercorrelation Limit | Effect on Number of Descriptors | Implication for Model Performance |

|---|---|---|

| 0.80 - 0.90 | Drastic reduction | May remove too many relevant descriptors, hurting performance. |

| 0.95 - 0.97 | Substantial reduction | Often a good balance for reducing redundancy. |

| 0.99 - 0.995 | Moderate reduction | Retains more descriptors; models may still suffer from multicollinearity. |

| 1.000 (No limit) | No descriptors removed | High risk of overfitting and unreliable models. |

Are certain types of machine learning models more resistant to intercorrelation? Yes. Tree-based ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting (e.g., XGBoost) and Random Forest are inherently more robust to descriptor intercorrelation. Their architecture, based on sequential splitting (boosting) or independent splitting (bagging) of features, naturally down-weights redundant descriptors, reducing the risk of overfitting to correlated noise [6] [10]. In contrast, models like Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) are highly sensitive to multicollinearity.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Model is Overfitting

Symptoms

- Excellent performance on the training data but poor performance on the validation or test set.

- High variance in model coefficients when the training data is slightly perturbed.

Diagnosis and Solutions

- Generate a Correlation Matrix: Visually inspect the heatmap for large red or blue regions indicating groups of highly correlated descriptors [6].

- Apply a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Analysis: While not explicitly mentioned in the search results, VIF is a standard statistical measure for quantifying multicollinearity in linear models. It can be used alongside correlation analysis.

- Use Robust Algorithms: Switch to algorithms like Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), which are less sensitive to intercorrelation. A case study on hERG inhibition showed that a GBM model significantly outperformed a linear model, in part due to its ability to handle complex, correlated descriptor relationships [6].

- Implement Advanced Feature Selection: Instead of simply filtering by correlation, use Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE). RFE is a wrapper method that iteratively builds a model and removes the least important features, considering the context of all other descriptors. This is a more sophisticated approach to handling redundancy [6] [10].

Problem: Model is Difficult to Interpret

Symptoms

- In a linear model, coefficients for correlated descriptors have counterintuitive signs or magnitudes.

- The "most important" features identified by the model change drastically with small changes in the training data.

Diagnosis and Solutions

- Systematic Feature Selection: Employ a method that systematically reduces feature multicollinearity. One proven approach involves:

- Generating a large pool of molecular descriptors.

- Iteratively identifying and removing one descriptor from each pair with a correlation above a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.95).

- Using a genetic algorithm for variable selection to build a final, interpretable MLR model. This method has been shown to yield models with excellent performance while maintaining interpretability [11].

- Remove Constant and Low-Variance Descriptors: As a first step, filter out descriptors with constant values or very low variance across the dataset, as these contribute no meaningful information and can skew analysis [6] [12].

Experimental Protocol for Managing Intercorrelation

Objective: To preprocess a dataset of molecular descriptors to minimize the negative effects of intercorrelation prior to building a QSAR model, with a specific focus on preparing data for Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE).

Workflow: The following diagram outlines the logical sequence for diagnosing and managing descriptor intercorrelation.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Descriptor Management

| Tool / Software | Type | Primary Function in this Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics Library | Generation of 2D molecular descriptors and fingerprints [8]. |

| DRAGON | Commercial Software | Generation of a wide range of molecular descriptors (2D, 3D) [7]. |

| Python/R | Programming Languages | Calculation of correlation matrices, implementation of filtering scripts, and execution of RFE [6]. |

| QSARINS | Software | Model building with Genetic Algorithm-based variable selection [7]. |

| Flare Python API | Tool/API | Provides scripts for descriptor removal based on variance and multi-collinearity thresholds [6]. |

Methodology:

- Descriptor Generation and Initial Filtering:

- Generate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors using software like RDKit or DRAGON.

- Remove all descriptors that are constant or have missing values across the dataset [7].

- (Optional but recommended) Remove descriptors with very low variance, as they contain little useful information for modeling.

Diagnosing Intercorrelation:

- Compute a correlation matrix for all remaining descriptors.

- Visually inspect the matrix using a heatmap to identify blocks of highly correlated descriptors.

Applying a Correlation Filter:

- Select an appropriate intercorrelation limit based on your modeling goals (see Table 1). For a balance between redundancy reduction and feature retention, a threshold between 0.95 and 0.97 is often effective [7].

- Implement an algorithm to iterate through all descriptor pairs. For any pair with a correlation coefficient whose absolute value exceeds the threshold, remove the descriptor that has a higher average correlation with all other descriptors in the pool [7]. This process ensures a systematic reduction of the most redundant features.

Advanced Feature Selection with RFE:

Visual Guide to the Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Process

RFE is a powerful wrapper method for feature selection that works by recursively building a model and removing the weakest features until the desired number is reached. The following diagram illustrates this iterative process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What specific problems does multicollinearity create for RFE? Multicollinearity causes several critical issues for RFE-based feature selection:

- Unstable Feature Rankings: Correlated features can cause significant swings in feature importance scores, meaning the same feature might be ranked very differently with minor changes to the dataset or model parameters [13] [14].

- Misleading Elimination: RFE may incorrectly eliminate truly important causal variables because their importance is "shared" with correlated features, reducing their perceived contribution [14].

- Reduced Detection Power: In high-dimensional data, multicollinearity can decrease RFE's ability to detect true causal features, even when using specialized algorithms like Random Forest RFE (RF-RFE) [14].

Q2: How can I detect multicollinearity in my dataset before applying RFE? The primary method for detecting multicollinearity is calculating Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) [13] [15]:

- VIF Interpretation: A VIF value of 1 indicates no correlation, values between 1-5 show moderate correlation, and values greater than 5 indicate critical multicollinearity where coefficient estimates become unreliable [13].

- Correlation Matrices: Examine correlation matrices to identify pairs of features with high correlation coefficients, which can help visualize relationships between variables [16].

Q3: Does multicollinearity always require corrective action in RFE? Not necessarily—the need for action depends on your analysis goals [13]:

- Prediction-Focused Models: If the primary goal is prediction accuracy rather than interpretation, multicollinearity has minimal impact on the model's predictive capabilities [13].

- Interpretation-Focused Models: If understanding individual feature contributions is crucial, multicollinearity must be addressed to ensure reliable feature rankings and selections [13].

Q4: Can RFE handle datasets with many correlated molecular descriptors? Standard RFE struggles with highly correlated molecular descriptors. Research shows that in high-dimensional omics data (e.g., 356,341 variables), RF-RFE decreased the importance of both causal and correlated variables, making true signals harder to detect [14]. For such scenarios, consider supplementing RFE with preprocessing methods specifically designed to minimize multicollinearity [11] [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unstable Feature Selection Results

Symptoms:

- Feature importance rankings change dramatically with small changes in the dataset

- Different features are selected when using different random seeds

- Inconsistent feature subsets across cross-validation folds

Solutions:

- Calculate VIF Scores: Quantify multicollinearity for all features using VIF [13] [15].

- Apply Correlation Analysis: Use correlation matrices to identify groups of highly correlated features [16].

- Implement Preprocessing: Center your variables to reduce structural multicollinearity, particularly when using interaction terms [13].

- Alternative Algorithms: For extremely high-dimensional data, consider that RFE may not scale well and explore alternative feature selection methods [14].

Problem 2: Important Features Being Incorrectly Eliminated

Symptoms:

- Known important features are ranked low and eliminated early

- Model performance decreases despite RFE selection

- Final feature subset lacks features with known biological significance

Solutions:

- Combine Filter Methods: Use statistical filter methods (e.g., correlation with target) before RFE to protect potentially important features [4].

- Adjust RFE Parameters: Use a smaller step size (eliminate fewer features per iteration) to make the elimination process more granular [19].

- Validate Externally: Compare selected features with domain knowledge to identify when important features are being lost [11].

Problem 3: Poor Model Performance After RFE

Symptoms:

- Model accuracy decreases after feature selection

- Selected features do not generalize to test datasets

- High variance in cross-validation performance

Solutions:

- Use Cross-Validation: Implement RFE within a cross-validation framework to ensure robust feature selection [4] [19].

- Pipeline Implementation: Ensure RFE and model training are properly encapsulated in a pipeline to prevent data leakage [19].

- Combine with Regularization: Use regularized models (e.g., Lasso) as the estimator within RFE to handle residual multicollinearity [4].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Quantitative Impact of Multicollinearity on RFE

Table 1: Performance Comparison of RF Models With and Without RFE in Presence of Multicollinearity

| Metric | RF Without RFE | RF With RFE (RF-RFE) |

|---|---|---|

| R² | -0.00203 | 0.19217 |

| MSEOOB | 0.07378 | 0.05948 |

| Causal SNP Detection | 1 of 5 identified | Varied performance across SNPs |

| Causal CpG Detection | Poor | Poor |

| Computational Time | ~6 hours | ~148 hours |

Data adapted from RF-RFE study on high-dimensional omics data [14]

VIF Threshold Guidelines for RFE Applications

Table 2: VIF Interpretation Guidelines for RFE Experiments

| VIF Range | Multicollinearity Level | Recommended Action for RFE |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | None | No action needed |

| 1.0-5.0 | Moderate | Monitor but may not require intervention |

| >5.0 | Critical | Address before RFE implementation |

| >10.0 | Severe | Must be resolved for reliable RFE results |

Based on multicollinearity analysis recommendations [13] [15]

Molecular Descriptor Selection Protocol

Objective: Systematically select molecular descriptors while minimizing collinearity for predictive modeling [11] [18]

Workflow:

- Descriptor Calculation: Generate comprehensive molecular descriptors from chemical structures

- Multicollinearity Screening: Calculate VIF for all descriptors and remove those with VIF > 5

- Initial RFE Implementation: Apply RFE with tree-based models to rank remaining features

- Iterative Refinement: Combine RFE with correlation analysis to select non-redundant, predictive features

- Validation: Verify selected features maintain predictive accuracy on holdout datasets

Key Considerations:

- Balance between feature importance and multicollinearity

- Domain knowledge integration to preserve scientifically meaningful features

- Computational efficiency for high-dimensional descriptor spaces [11]

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RFE with Molecular Descriptors

| Tool/Technique | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | Quantifies multicollinearity severity | Pre-RFE screening to identify problematic features [13] [15] |

| Correlation Matrix Analysis | Visualizes pairwise feature relationships | Identifying groups of correlated molecular descriptors [16] |

| Variable Centering/Standardization | Reduces structural multicollinearity | Essential when including interaction terms in models [13] |

| Tree-Based Pipeline Optimization (TPOT) | Automated machine learning pipeline optimization | Developing interpretable models with selected features [11] |

| Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) | Automated feature number selection | Determining optimal feature subset size while managing overfitting [4] [19] |

| Gradient-Boosted Feature Selection (GBFS) | Advanced feature selection workflow | Handling high-dimensional molecular descriptor spaces [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is multicollinearity and why is it problematic in molecular descriptor research? Multicollinearity occurs when two or more explanatory variables in a regression model are highly linearly intercorrelated [20]. In the context of molecular descriptor research, this means your descriptors are not independent, which inflates the variance of regression coefficients, leading to unreliable probability values and wide confidence intervals [20]. This makes it difficult to determine the individual effect of each molecular descriptor on your target property or activity, compromising the interpretability and statistical stability of your Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) model [6].

2. How do I know which specific descriptors are multicollinear? While VIF and condition index can indicate the presence of multicollinearity, you need Variance Decomposition Proportions (VDP) to identify the specific variables involved [20]. When two or more VDPs, which correspond to a common condition index higher than 10 to 30, are higher than 0.8 to 0.9, their associated explanatory variables are considered multicollinear [20].

3. My model has high predictive power but also high multicollinearity. Should I be concerned? If your primary goal is only prediction, a model with high multicollinearity might still be usable [21]. However, for research aimed at understanding the unique contribution of each molecular descriptor (e.g., in Recursive Feature Elimination or RFE), multicollinearity is a critical issue. It masks the individual effect of descriptors, making it difficult to reliably select or eliminate features based on their importance [20] [6]. For interpretable models, correcting multicollinearity is essential.

4. Are some modeling techniques inherently robust to multicollinearity? Yes, machine learning models like Gradient Boosting are more resilient. Their decision-tree-based architecture naturally prioritizes informative splits and down-weights redundant descriptors, making them well-suited for high-dimensional descriptor sets with inherent correlations [6]. However, understanding descriptor intercorrelation remains vital for model interpretation and feature selection.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Unstable Regression Coefficients and Inflated Standard Errors

Problem: The coefficients of your molecular descriptors change dramatically with small changes in the dataset, and their standard errors or confidence intervals are unusually large.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a classic symptom of multicollinearity. Follow this diagnostic workflow to confirm and address the issue.

Detailed Diagnostic Protocol:

Generate a Correlation Matrix

- Objective: Visually identify pairs of descriptors with strong linear relationships.

- Protocol: Create a table of Pearson's correlation coefficients for all pairs of molecular descriptors. Typically, a correlation greater than 0.80 or less than -0.80 indicates strong multicollinearity that requires further investigation [21]. Software like Python (with Pandas/Seaborn), R, or Displayr can be used to create and visualize this matrix [22].

Calculate Variance Inflation Factors (VIF)

- Objective: Quantify how much the variance of a regression coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity.

- Protocol:

- For each descriptor

X_i, run a multiple regression whereX_iis the response variable and all other descriptors are the predictors. - Obtain the R-squared value (Ri²) from this regression.

- Calculate VIF for

X_iusing the formula: VIF = 1 / (1 - Ri²) [23] [24]. - A VIF of 1 indicates no multicollinearity. A VIF above 5 to 10 is generally considered problematic [20] [24].

- For each descriptor

Perform Eigenanalysis (Condition Index and Variance Decomposition Proportions)

- Objective: Identify the specific groups of descriptors that are multicollinear.

- Protocol:

- Standardize your explanatory variables and compute the correlation matrix.

- Calculate the eigenvalues (λ) of this matrix.

- Compute the Condition Index for each eigenvalue: √(λmax / λi). The largest condition index is the Condition Number [20].

- Use the eigenvectors to calculate Variance Decomposition Proportions (VDPs), which show the proportion of variance each eigenvector contributes to each regression coefficient's variance [20].

- Multicollinearity is indicated when two or more VDPs for different descriptors exceed 0.8-0.9 for a condition index greater than 10-30 [20].

Issue 2: High VIFs in a Model with Polynomial or Interaction Terms

Problem: You have included terms like X² or X*Y in your model to capture non-linearity, and these terms show extremely high VIFs.

Diagnosis and Solution:

This is expected because X and X² are often highly correlated. This is a situation where high VIFs can sometimes be safely ignored because the model is correctly specified to capture a non-linear effect [24]. The solution is to center your variables (subtract the mean from each value of X) before creating the polynomial or interaction terms. This reduces the correlation between the linear and quadratic terms and can significantly lower the VIF, without changing the model's fundamental interpretation.

Diagnostic Metrics Reference Tables

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for Key Multicollinearity Diagnostics

| Diagnostic Tool | Calculation | Acceptable Range | Problematic Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) | ( \text{VIF} = \frac{1}{(1 - R_i^2)} ) [23] [24] | 1 - 5 [24] | 5 - 10 or above [20] [21] | Factor by which the variance of a coefficient is inflated due to multicollinearity. |

| Tolerance | ( \text{Tolerance} = 1 - R_i^2 ) [20] | 0.2 - 1.0 | 0.1 - 0.25 or below [24] | Reciprocal of VIF. The amount of variance in a descriptor not explained by the others. |

| Condition Index (CI) | ( \text{CI} = \sqrt{\frac{\lambda{max}}{\lambdai}} ) [20] | Below 10 - 15 | 10 - 30 or above [20] | Indates the presence of multicollinearity. |

| Variance Decomposition Proportion (VDP) | Derived from eigenvectors of the correlation matrix [20] | Below 0.8 - 0.9 | Above 0.8 - 0.9 [20] | Identifies specific multicollinear variables when 2+ VDPs share a high CI. |

Table 2: Summary of Correction Methods for Multicollinear Molecular Descriptors

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remove Variables | Manually remove one or more descriptors from a multicollinear group identified by VDP [20] [21]. | Simple, improves model stability [20]. | Risk of losing valuable information; requires domain knowledge [20]. |

| Feature Selection (RFE) | Use Recursive Feature Elimination to iteratively remove the least important features based on model performance [6]. | Data-driven; retains the most predictive features. | Computationally intensive; complex to implement. |

| Combine Variables | Create a composite index or score by averaging or summing highly correlated descriptors [21]. | Reduces redundancy, preserves information. | May reduce interpretability of individual descriptors. |

| Regularization (Ridge Regression) | Use a biased estimation method that introduces a penalty term on large coefficients [20] [21]. | Keeps all variables in the model; good for prediction. | Coefficients are biased, making interpretation less straightforward. |

| Switch to Robust ML Models | Use algorithms like Gradient Boosting that are inherently resilient to multicollinearity [6]. | Handles multicollinearity automatically; powerful for prediction. | Model can be a "black box"; individual coefficient interpretation is difficult. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Resources for Multicollinearity Analysis in Molecular Research

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance to Multicollinearity |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Programming environments with extensive statistical and machine learning libraries (e.g., statsmodels, scikit-learn in Python). |

Essential for calculating VIF, condition indices, performing PCA, and building regularized or Gradient Boosting models [6]. |

| Molecular Descriptor Calculators (RDKit) | Open-source cheminformatics software that calculates a wide array of 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [6]. | Generates the initial set of features that must be checked for intercorrelation before model building. |

| Flare V10 (Cresset) | An integrated platform for molecular modeling that includes QSAR capabilities and a Python API [6]. | Provides scripts for descriptor removal based on variance and multicollinearity, and built-in robust Gradient Boosting models [6]. |

| Gradient Boosting Machine Learning | A powerful tree-based ensemble algorithm that builds models sequentially to correct errors from previous trees [6]. | A key solution, as it is inherently robust to multicollinearity, reducing the need for extensive pre-filtering of descriptors [6]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality-reduction technique that transforms original variables into a new set of uncorrelated components [21] [24]. | A corrective measure used to create a smaller set of uncorrelated variables from a large number of multicollinear descriptors. |

In the context of building robust Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models for drug discovery, managing multicollinearity within molecular descriptor sets is a critical pre-processing step. Multicollinearity occurs when two or more predictor variables in a dataset are highly correlated, which can lead to unstable model coefficients, inflated standard errors, and reduced statistical power, ultimately compromising the interpretability and reliability of your models [15] [6] [25]. This case study, framed within broader thesis research on handling multicollinearity for Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), provides a technical guide for researchers and scientists encountering these issues during their experiments with RDKit descriptors.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does multicollinearity pose a problem for my QSAR model and subsequent RFE?

Multicollinearity is problematic because it undermines the statistical integrity of your regression-based QSAR models and can confound the feature selection process.

- Unstable Coefficient Estimates: When predictors are highly correlated, the regression coefficients can become highly sensitive to minor changes in the model or the data, making their values unreliable [25].

- Reduced Statistical Power: It becomes harder to detect significant relationships between individual descriptors and the target response variable [25].

- Inflated Standard Errors: This leads to wider confidence intervals and less precise estimates of the coefficients [15] [25].

- Impact on RFE: While wrapper methods like RFE consider feature interactions [4], a dataset plagued by multicollinearity can cause the algorithm to be unstable in its initial rankings, potentially leading to the arbitrary elimination of important features.

FAQ 2: How can I detect multicollinearity in my set of RDKit descriptors?

A multi-faceted approach is recommended to reliably diagnose multicollinearity. The following workflow outlines a robust diagnostic protocol:

Experimental Protocol for Diagnosis:

Calculate the Feature Correlation Matrix

- Methodology: Using Python's pandas library, compute the Pearson correlation coefficient for every pair of descriptors in your dataset. This generates a matrix where each cell shows the correlation between two variables.

- Interpretation: Visually inspect the matrix using a heatmap. Look for pairs of descriptors with correlation coefficients exceeding a predetermined threshold, typically |r| > 0.8 or |r| > 0.9 [6] [25].

Compute the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF)

- Methodology: For each descriptor

X_i, run an ordinary least squares regression whereX_iis the dependent variable predicted by all other descriptors in the set. The VIF is then calculated asVIF = 1 / (1 - R²_i), whereR²_iis the coefficient of determination from that regression. - Interpretation: Use the following table to assess the severity of multicollinearity based on the VIF values [15] [25]:

- Methodology: For each descriptor

| VIF Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| VIF = 1 | No multicollinearity |

| 1 < VIF ≤ 5 | Moderate multicollinearity |

| 5 < VIF ≤ 10 | High multicollinearity; potential issue |

| VIF > 10 | Severe multicollinearity; requires remediation [25] |

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for handling multicollinearity before applying RFE?

Once multicollinearity is diagnosed, you can apply several strategies to mitigate its effects. The table below compares the most common approaches.

| Method | Brief Explanation | Key Consideration for QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Remove Correlated Features | Manually remove one descriptor from each highly correlated pair (based on correlation matrix or VIF) [6] [25]. | Simple and effective, but may discard chemically relevant information if done without domain knowledge. |

| Use Regularization | Apply Ridge Regression (L2 penalty) or Lasso (L1 penalty), which constrains coefficient sizes and handles correlated variables well [15] [25]. | Improves model stability and prediction; Lasso can also perform feature selection by zeroing some coefficients. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Transform original correlated descriptors into a smaller set of linearly uncorrelated principal components [4] [25]. | Preserves variance while eliminating multicollinearity, but the new features lose chemical interpretability. |

| Leverage Robust Algorithms | Use tree-based models like Gradient Boosting or Random Forest, which are inherently less sensitive to multicollinearity [6]. | Algorithms like XGBoost can naturally prioritize important features and are less prone to overfitting [6]. |

FAQ 4: My RFE model is overfitting even after removing correlated features. What else can I do?

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying pattern. If basic multicollinearity handling isn't sufficient, consider these advanced protocols:

Refine Your RFE Protocol:

- Use RFECV: Implement Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV) to automatically determine the optimal number of features, which helps in preventing overfitting by evaluating feature subsets on different validation folds [4].

- Pipeline Integration: Always embed the RFE and your final model within a scikit-learn

Pipelineand perform hyperparameter tuning and validation on this entire pipeline. This prevents data leakage and ensures a more realistic performance estimate [19].

Apply Stronger Regularization: If using linear models, increase the regularization strength (e.g., the

alphaparameter in Ridge or Lasso regression). This more heavily penalizes large coefficients, simplifying the model [25].Tune Model Hyperparameters: For tree-based models, limit model complexity by tuning hyperparameters such as maximum tree depth, minimum samples per leaf, and learning rate (for boosting algorithms) to reduce variance [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key software and libraries essential for implementing the protocols described in this case study.

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| RDKit | A core open-source cheminformatics toolkit used to calculate 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures [9]. |

| Scikit-learn | A fundamental Python library for machine learning. It provides the RFE and RFECV classes, various models, and preprocessing tools [4] [19]. |

| Statsmodels & SciPy | Libraries offering comprehensive statistical functions, including the calculation of Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) and correlation matrices. |

| DOPtools | A specialized Python platform that provides a unified API for calculating chemical descriptors and is especially suited for reaction modeling [26]. |

| Pandas & NumPy | Core Python libraries for data manipulation, analysis, and numerical computations, essential for handling descriptor matrices. |

Integrated RFE Workflows: Combining Statistical and Machine Learning Approaches

For researchers in drug development working with molecular descriptors, pre-processing data is a critical step to ensure robust model performance. Techniques like centering, scaling, and initial filtering are foundational for mitigating multicollinearity—a common issue where correlated predictors inflate model variance and obscure the true effect of individual molecular features. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice to address specific challenges encountered when preparing data for advanced feature selection methods like Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I center and scale my molecular descriptor data before using RFE? Many machine learning algorithms, including those used in RFE, are sensitive to the scale of your features. Molecular descriptors often contain integer, decimal, and binary values on vastly different scales [17]. If one descriptor has a much larger scale (e.g., molecular weight in the hundreds) than another (e.g., a binary indicator), the model may incorrectly perceive it as more important [27]. Centering and scaling ensure all features contribute equally, which is crucial for distance-based models like Support Vector Machines (SVMs)—a common choice for RFE—and gradient-based models to converge effectively [4] [27].

FAQ 2: My model's coefficients are highly unstable and change drastically when I add or remove a variable. What is happening? This is a classic symptom of multicollinearity, where independent variables in your regression model are highly correlated [13] [25]. When descriptors are correlated, it becomes difficult for the model to isolate each one's individual effect on the response variable. This leads to unreliable coefficient estimates, inflated standard errors, and reduced statistical power, making it hard to identify truly significant molecular features [13] [25].

FAQ 3: How can I detect multicollinearity in my dataset of molecular descriptors? The most straightforward method is to calculate the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for each descriptor.

- VIF = 1: No multicollinearity.

- 1 < VIF ≤ 5: Moderate correlation, often acceptable.

- VIF > 5 to 10: High multicollinearity that needs attention [13] [25]. You can also examine a correlation matrix to identify pairs of descriptors with high correlation coefficients [25].

FAQ 4: I have high multicollinearity, but I need to keep all my descriptors for interpretation. What can I do? If your primary goal is prediction rather than interpretation, you can use regularization techniques like Ridge Regression [25]. Ridge regression adds an L2 penalty to the model's coefficients, which shrinks them but does not set any to zero. This helps stabilize the coefficient estimates and mitigate the effects of multicollinearity without removing any features [25].

FAQ 5: Does multicollinearity affect my model's predictive accuracy? Not necessarily. Multicollinearity primarily affects the interpretation of individual coefficients and their p-values. Your model's overall predictions, R-squared value, and goodness-of-fit statistics may remain unaffected [13]. Therefore, if your only goal is to make accurate predictions, severe multicollinearity may not always be a critical problem.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High Multicollinearity Detected by VIF

Problem: The VIF for several molecular descriptors is above the acceptable threshold (e.g., VIF > 5), indicating severe multicollinearity [13] [25].

Solution: Apply one or more of the following strategies.

Table 1: Strategies for Remediating High Multicollinearity

| Strategy | Description | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remove Correlated Features | Identify and remove one of the highly correlated descriptors. | Simplicity; when interpretability is key. | You may lose information from the removed feature. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Transform correlated variables into a new set of uncorrelated principal components. | High-dimensional datasets; when prediction is the main goal. | New components are less interpretable than original descriptors. |

| Ridge Regression | Apply a regularization penalty (L2) that shrinks coefficients but keeps all features. | When you need to keep all descriptors for interpretation. | Coefficients are biased but more stable. |

Experimental Protocol: Using PCA to Handle Multicollinearity

This protocol uses scikit-learn to reduce descriptor correlation.

- Standardize the Data: PCA is affected by feature scale, so you must center and scale the data first [28].

- Apply PCA: Transform the standardized data into principal components.

- Check Explained Variance: Determine how much information the new components retain.

The resulting

X_pcacan be used as input for your RFE model [25].

Issue: Model Performance is Poor or Inconsistent After Pre-processing

Problem: After centering, scaling, and feature filtering, the model's performance does not improve or becomes worse.

Solution: Review your pre-processing sequence and model selection.

- Data Leakage: Ensure that scaling and feature selection are fit only on the training data. Use a

Pipelineto prevent information from the test set leaking into the training process [28]. - Incorrect Scaler for Data Type: Use

MaxAbsScalerfor data that is already centered at zero or sparse data, as centering sparse data would destroy its structure [28]. - Algorithm Choice: Remember that not all models require scaling. Tree-based models (e.g., Random Forests) are insensitive to feature scale, so pre-processing may be an unnecessary step for them [27].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Scaling Methods

| Method | Formula | Use Case | Advantages | Disadvantages | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardization (Z-score) | (X - μ) / σ | PCA, SVMs, linear models. | Results in a standard normal distribution. | Sensitive to outliers. | ||

| Min-Max Scaling | (X - Xmin) / (Xmax - X_min) | Neural networks, data bounded in a range. | Preserves original data distribution. | Also sensitive to outliers. | ||

| MaxAbs Scaling | X / | X_max | Sparse data. | Preserves sparsity and sign of data. | Not suitable if data is not centered. |

Workflow and Process Diagrams

Diagram 1: Pre-processing and Feature Selection Workflow This diagram outlines the logical sequence for handling molecular descriptor data, from raw data to a refined feature set ready for modeling.

Diagram 2: The Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) Process This diagram details the iterative loop at the heart of the RFE algorithm for feature selection.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Software and Libraries for Pre-processing

| Tool / Library | Function | Application in Pre-processing |

|---|---|---|

| scikit-learn [28] [29] | A comprehensive machine learning library for Python. | Provides StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler, VarianceThreshold, RFE, PCA, and Ridge regression, making it a one-stop shop for all pre-processing and modeling steps. |

| RDKit [30] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used to generate canonical molecular descriptors and fingerprints from SMILES strings, which form the initial raw feature set. |

| Mordred [30] | A molecular descriptor calculator. | Can generate a very extensive set of over 1,600 molecular descriptors for a comprehensive feature space. |

| Python (NumPy, pandas) | Programming language and data manipulation libraries. | The foundation for data handling, manipulation, and orchestrating the entire pre-processing workflow. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using GBFS over other feature selection methods for molecular data?

GBFS is a novel feature selection algorithm that satisfies four key conditions ideal for molecular data: it reliably extracts relevant features, can identify non-linear feature interactions, scales linearly with the number of features and dimensions, and allows for the incorporation of known sparsity structure. Its flexibility and scalability make it particularly well-suited for high-dimensional molecular descriptor datasets [31].

Q2: My model performance is good, but the selected molecular descriptors seem biased towards categorical variables with high cardinality. How can I address this?

This is a known issue with standard Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM); their base learners can be biased towards categorical variables with many categories, which can skew feature importance measures. To mitigate this, implement a Cross-Validated Boosting (CVB) framework. In CVB, a variable is selected for splitting based on its cross-validated performance rather than its performance on the training sample alone. This ensures a "fair" comparison between features and leads to more reliable feature importance scores while maintaining predictive accuracy [32].

Q3: How can I improve the stability of my selected feature set when using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with molecular data?

Stability in feature selection can be significantly improved by applying a data transformation before RFE. Specifically, research in microbiome data (which shares high-dimensional characteristics with molecular descriptor data) has shown that using a kernel-based transformation, such as one derived from the Bray–Curtis similarity matrix, before RFE can substantially improve the stability of the selected features without sacrificing classification performance. This method projects data into a new space where correlated features are mapped closer together, making the selection process more robust [33].

Q4: Are there hybrid methods that combine GBFS with other feature selection techniques for better results?

Yes, hybrid methods are highly effective. You can combine the power of GBFS with the precision of Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation (RFECV). For instance, a pipeline can be designed where a Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) is used as the core estimator within the RFECV process (RFECV-GBM). This hybrid approach leverages the GBM's ability to model complex relationships to recursively eliminate the least important features in a cross-validated manner, ensuring an optimal and robust subset of features is selected [34].

Q5: Is there a systematic way to select molecular descriptors to minimize multicollinearity?

A proven method involves systematically selecting molecular descriptor features to reduce feature multicollinearity. This process simplifies feature selection by minimizing redundant information between descriptors. The resulting models are not only interpretable but also maintain high performance, enabling the discovery of new, robust relationships between global molecular properties and their descriptors [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Generalization Despite High Training Accuracy

Symptoms:

- High performance on training data but significant drop in performance on validation or test sets.

- Selected feature set varies greatly with slight changes in the training data.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: High Multicollinearity Among Molecular Descriptors.

- Solution: Implement a pre-processing step to reduce feature multicollinearity. Systematically select descriptors to minimize collinearity before applying GBFS or RFE. This improves model interpretability and stability [11].

- Actionable Step: Calculate the correlation matrix for your molecular descriptors. Use variance inflation factors (VIF) or a similar metric to identify and remove highly correlated descriptors prior to feature selection.

Cause 2: Unstable Feature Selection.

- Solution: Use a hybrid RFECV method with a robust base estimator like GBM or Random Forest. RFECV provides a more stable feature ranking through cross-validation [35] [34].

- Actionable Step: Employ the

RFECVfunction from ML libraries (e.g., scikit-learn) using aGradientBoostingClassifierorGradientBoostingRegressoras the estimator. This will output a cross-validated ranking of your features.

Issue 2: Biased Feature Importance from Categorical Descriptors

Symptoms:

- Categorical molecular descriptors (e.g., functional group presence, atom types) with a large number of categories are consistently ranked as the most important, even when domain knowledge suggests otherwise.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inherent bias in standard GBM implementations towards high-cardinality categorical features.

- Solution: Implement Cross-Validated Boosting (CVB) to correct the bias in feature importance measures [32].

- Actionable Step: Instead of using a standard GBM, modify the tree-growing process. During training, for each split, evaluate a feature's performance using k-fold cross-validation on the training data at that node. Select the feature with the best generalizable performance.

Issue 3: Computationally Expensive Feature Selection

Symptoms:

- The feature selection process takes an impractically long time for large-scale molecular datasets with thousands of descriptors.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The wrapper method (like RFE) requires retraining the model multiple times, which is computationally heavy.

- Solution 1: Leverage the inherent efficiency of the GBFS algorithm, which is designed to scale linearly with the number of features and dimensions [31].

- Solution 2: Use stochastic modifications of GBM, such as those in LightGBM or XGBoost, which use sampling techniques to speed up the training process of each base learner [32].

- Actionable Step: For large datasets, use implementations like LightGBM, which supports categorical features natively and uses histogram-based algorithms for faster training, as the core estimator in your GBFS or RFECV pipeline.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Systematic Descriptor Selection and Modeling

The following protocol, adapted from a study on biofuel molecular properties, outlines a robust pipeline for building interpretable models with selected molecular descriptors [11].

- Data Collection: Assemble a publicly available experimental dataset for the target molecular property (e.g., melting point, boiling point). The study used up to 8,351 organic molecules.

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors for all molecules in the dataset.

- Feature Selection & Multicollinearity Reduction: Apply a systematic method for selecting molecular descriptor features to minimize feature multicollinearity.

- Model Training with AutoML: Use the Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool (TPOT) to train and select the best-performing model architecture on the selected features.

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the final model using metrics like Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE). The cited study achieved MAPE values ranging from 3.3% to 10.5% for various properties.

- Interpretation and Tool Deployment: Analyze the set of features that are well-correlated with the property. Integrate the data and models into an open-source, interactive web tool for broader use.

GBFS Hybrid Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates a hybrid feature selection workflow that combines GBFS and RFECV for robust feature selection on molecular data.

Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Materials and Tools for a GBFS Workflow

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance to GBFS Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| TPOT (Tree-based Pipeline Optimization Tool) | An AutoML tool that automates the process of model selection and hyperparameter tuning using genetic programming. | Used to train and optimize the final predictive models after feature selection, ensuring high performance without manual tuning [11]. |

| LightGBM (LGBM) | A gradient boosting framework that uses tree-based algorithms and supports categorical features directly. It is optimized for high speed and efficiency. | Can serve as a high-performance base learner for GBFS or within an RFECV pipeline, especially with large datasets and categorical molecular descriptors [32]. |

| XGBoost | An optimized distributed gradient boosting library designed to be efficient and flexible. | A common choice for implementing the core boosting algorithm in GBFS, known for its regularization and scalability [32] [34]. |

| RFECV (Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation) | A wrapper method that recursively removes the least important features based on a model's feature importance, using cross-validation to determine the optimal number of features. | Forms the basis of a hybrid approach (e.g., RFECV-GBM) to create a stable and optimal feature subset [35] [34]. |

| Bray-Curtis Similarity / UMAP | A data transformation technique that projects features into a new space based on similarity, improving the stability of subsequent feature selection. | Applied before RFE to improve the stability and reliability of the selected molecular descriptors [33]. |

Implementing RFE with Stability Enhancements for Correlated Descriptors

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my feature selection become unstable when I run Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) on a dataset with highly correlated molecular descriptors?

Highly correlated descriptors create instability in RFE because the algorithm may arbitrarily select one correlated feature over another during its iterative elimination process, as both carry similar predictive information. This can lead to different feature subsets being selected across different runs or data splits, reducing the reproducibility of your model. Implementing a pre-filtering step to reduce multicollinearity before applying RFE is recommended to enhance stability [36] [6].

Q2: What are the practical methods to pre-filter correlated descriptors to stabilize RFE output?

A highly effective method is to first calculate the correlation matrix for all descriptors and then filter them based on a pre-defined threshold (e.g., |r| > 0.8). From each group of highly correlated features, you can retain only the one with the highest correlation to the target property, removing the others. This process reduces redundancy and the arbitrary influence of correlated feature groups on the RFE algorithm, leading to more stable and interpretable feature subsets [36] [6].

Q3: My model performance drops after removing correlated descriptors. Is this normal, and how can I mitigate it?

This can occur if the removed descriptors, while redundant, still contained subtle, unique information. However, this performance drop is often minimal and is counterbalanced by significant gains in model stability and generalizability. To mitigate the drop, consider using machine learning models like Gradient Boosting (GB) or Random Forest (RF), which are inherently more robust to multicollinearity. Their tree-based structure naturally down-weights redundant features, making them ideal for use with RFE on descriptor sets where some correlation may remain [6].

Q4: How can I validate that my stabilized RFE process is truly reproducible?

To validate reproducibility, you should run the entire stabilized pipeline—including correlation filtering and RFE—multiple times using different random seeds for data splitting (e.g., in k-fold cross-validation). A stable process will yield a highly consistent set of selected features across these iterations. You can quantify this stability using metrics like the Jaccard index, which measures the similarity between the feature subsets selected in different runs [36].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The following workflow, termed the Stabilized RFE (S-RFE) Pipeline, integrates correlation filtering with RFE to ensure robust feature selection from a high-dimensional descriptor space.

Stabilized RFE (S-RFE) Workflow

Phase 1: Data Preprocessing and Correlation Filtering

- Descriptor Calculation and Initial Cleaning: Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors (e.g., using RDKit) for all compounds in your dataset. Remove descriptors with zero variance or a high proportion of missing values [6].

- Construct Correlation Matrix: Calculate the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient for all remaining descriptors. Visualize the matrix to identify blocks of highly correlated features [6].

- Apply Correlation Filter:

- Set a correlation threshold (commonly |r| > 0.8 or 0.9).

- Identify clusters of descriptors that exceed this threshold.

- Within each cluster, calculate the absolute correlation between each descriptor and the target property (e.g., biological activity, retention time).

- Retain only the descriptor with the highest absolute correlation to the target and remove the others from the dataset [36].

- This results in a reduced, less redundant descriptor set.

Phase 2: Stabilized Recursive Feature Elimination

- Algorithm Selection: Select a base estimator for RFE. Tree-based models like Gradient Boosting (GB) or Random Forest (RF) are preferred as they are robust to any residual multicollinearity. Alternatively, a linear model like SVM can be used for a more aggressive feature selection approach [6] [10].

- Iterative Feature Elimination:

- The RFE process is run on the pre-filtered descriptor set.

- The model is trained, and feature importance are assessed.

- The least important features (e.g., bottom 10-20%) are pruned.

- The process repeats with the remaining features until the predefined number of features is reached.

- Cross-Validation Integration: To ensure robustness, the entire S-RFE pipeline should be performed within a cross-validation loop (e.g., 5-fold or 10-fold). This prevents data leakage and provides a realistic assessment of the model's performance and the stability of the selected features on unseen data [36].

Phase 3: Validation and Final Model Training

- Stability Assessment: Compare the feature subsets selected across different cross-validation folds. A high degree of overlap indicates a stable feature selection process.

- Final Model Training: Using the stable feature subset identified by the S-RFE pipeline, train a final model on the entire training set. Validate its performance on a held-out test set that was not used at any stage of the feature selection process [10].

The table below summarizes the typical outcomes of applying the S-RFE pipeline compared to standard RFE, as evidenced by related research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Standard RFE vs. Stabilized RFE (S-RFE) Pipeline

| Metric | Standard RFE | S-RFE Pipeline (with Correlation Filtering) | Context / Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Set Stability | Low to Moderate | High | Parkinson's disease detection with XGBoost [36] |

| Model Generalizability | Can be reduced due to overfitting | Improved | QSAR modeling with Gradient Boosting [6] |

| Final Model Accuracy | 96.1% ± 0.8% | 98.3% ± 0.8% | Subject-wise PD detection, XGBoost [36] |

| Number of Final Features | Often larger and redundant | Reduced and informative | Molecular property prediction [11] |

| Computational Cost | Lower per iteration, but may require more runs | Slightly higher initial cost, more efficient long-term | General QSRR modeling [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function in S-RFE Pipeline | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Calculates 2D and 3D molecular descriptors from chemical structures. | Used to generate physicochemical properties, topological indices, and fingerprints as the initial feature pool [6]. |

| scikit-learn (Python) | Provides implementations for RFE, correlation analysis, and various ML models (GB, RF, SVM). | The RFE and SelectFromModel classes are key. Integration with Pipeline ensures a proper workflow [36] [10]. |

| Gradient Boosting Models (XGBoost, GBR) | Acts as the base estimator for RFE; robust to residual multicollinearity. | Provides feature importance scores for the elimination process. XGBoost has been shown to deliver high performance in stabilized pipelines [36] [6]. |

| Correlation Threshold | A user-defined value (e.g., 0.8-0.9) to identify and filter redundant descriptors. | A critical parameter; a higher value retains more features, while a lower value creates a more aggressive filter [36] [6]. |

| k-fold Cross-Validation | Evaluates the stability and generalizability of the selected feature subset. | Prevents overfitting and provides a realistic performance estimate for the final model [36] [10]. |

Integration with Gradient Boosting Models for Inherent Multicollinearity Resistance

Gradient Boosting Models (GBMs), including advanced implementations like XGBoost, are highly regarded in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies and molecular descriptor research for their inherent resistance to multicollinearity. Unlike linear models that can become unstable and produce unreliable coefficient estimates when predictors are highly correlated, tree-based boosting algorithms make splitting decisions based on one feature at a time. This process naturally avoids the pitfalls of multicollinearity, as the model prioritizes the most predictive features regardless of their correlation with others [37] [38]. Furthermore, GBMs possess built-in regularization mechanisms that prevent overfitting and enhance generalization to new data, making them particularly robust for high-dimensional biological data where correlated features are common [38] [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I choose Gradient Boosting over Linear Regression (like LASSO) for my dataset with highly correlated molecular descriptors?

Linear models, including penalized versions like LASSO regression, are highly sensitive to multicollinearity. This can lead to inflated coefficient variances and unstable feature selection, making model interpretation difficult [40] [39]. In contrast, Gradient Boosting is a tree-based ensemble method that makes decisions based on one feature at a time. This fundamental characteristic makes it inherently robust to correlated descriptors, as it can use whichever predictor provides the best split at a given node. While it may not automatically exclude redundant features, it effectively manages them without compromising predictive accuracy [37] [38].

Q2: A highly correlated descriptor was ranked as very important by my GBM. Should I manually remove the other correlated descriptors it's linked to?

Not necessarily. The GBM's feature importance score reflects a feature's utility in the model's prediction, even in the presence of correlation. If a descriptor is ranked as highly important, it means the model consistently finds it valuable for making splits. Manually removing its correlated counterparts could harm performance if those features provide complementary information in different contexts of the tree. It is often better to trust the model's selection unless you have a specific scientific reason (e.g., domain knowledge) to do otherwise [11].

Q3: My GBM model has high predictive accuracy on the training data but performs poorly on the test set. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

This is a classic sign of overfitting. While GBMs are robust to multicollinearity, they can still overfit, especially with noisy data or improper hyperparameter settings [39]. To address this:

- Tune Hyperparameters: Key parameters to adjust are the learning rate (

etain XGBoost), the maximum depth of the trees (max_depth), and the number of boosting rounds (n_estimators). A lower learning rate with a higher number of trees often leads to better generalization [41]. - Increase Regularization: Modern GBMs like XGBoost offer L1 and L2 regularization terms on the weights of the model. Increasing these parameters can penalize complexity and reduce overfitting [39].

- Use Early Stopping: Implement early stopping during training to halt the process when the performance on a validation set stops improving, thus preventing the model from learning the noise in the training data [41].

Q4: How can I improve the interpretability of my GBM model to understand which molecular descriptors are most critical?

Although GBMs are often seen as "black boxes," several techniques can aid interpretation:

- Feature Importance: GBMs natively provide a feature importance score based on how much a feature improves the model's performance (e.g., "gain" in XGBoost). This is an excellent starting point for identifying the most influential descriptors [41] [11].

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) Values: SHAP is a game-theoretic approach that assigns each feature an importance value for a single prediction. It provides a unified and more consistent measure of feature impact than traditional importance scores and can be visualized in various plots (e.g., summary plots, dependence plots) to deepen your understanding [41].

Experimental Protocols & Validation

Protocol 1: Validating GBM's Robustness to Multicollinearity

This protocol outlines a comparative experiment to benchmark GBM's performance against other algorithms in the presence of multicollinearity.

1. Objective: To compare the predictive performance and stability of Gradient Boosting, Linear Regression, and Random Forest when trained on a dataset of highly correlated molecular descriptors.

2. Dataset:

* Utilize a publicly available dataset of known HIV integrase inhibitors, such as the one from the ChEMBL database [42].

* Calculate a standard set of molecular descriptors (e.g., Molecular Weight, LogP, Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors, Topological Polar Surface Area) [42] [11].

3. Introducing Multicollinearity:

* Compute the correlation matrix for all molecular descriptors.

* Artificially engineer new, highly correlated variables (e.g., LogP_x_1.1, TPSA + 0.1*MW) to augment the dataset and simulate a high-collinearity environment.

4. Model Training & Comparison:

* Models: Train a GBM (e.g., XGBoost), a Linear Regression model with L2 regularization (Ridge), and a Random Forest.

* Feature Selection: Apply Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with each model to identify the most predictive descriptors [42] [41].

* Evaluation: Use a hold-out test set or cross-validation. Record key performance metrics and the final set of selected features for each model.

Table 1: Expected Performance Metrics in a High-Multicollinearity Scenario

| Model | Expected RMSE | Expected Accuracy/Precision | Feature Selection Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Low (e.g., ~0.82 AUC) [42] | High (e.g., ~0.79 Precision) [42] | High |

| Ridge Regression | Moderate | Moderate | Low (coefficients shrink but all features retained) |

| Random Forest | Low [41] | High [41] | Moderate (can be affected by correlated features) |

Protocol 2: A Systematic Workflow for Molecular Descriptor Selection with GBM

This workflow integrates GBM with systematic feature selection for building robust QSAR models.

1. Data Curation: Source and clean bioactivity data (e.g., IC50 values from ChEMBL). Standardize molecular structures and convert IC50 to pIC50 for better model performance [42]. 2. Descriptor Calculation & Preprocessing: Calculate a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors. Address missing values and standardize the data. 3. Correlation Analysis: Calculate the inter-descriptor correlation matrix. This step does not require removing features but is crucial for understanding the data structure and later interpreting the model. 4. Model Training with Integrated Feature Selection: * Utilize the GBM's built-in feature importance. * Employ Recursive Feature Elimination with GBM (GBM-RFE) to iteratively prune the least important features. * Use resampling techniques (e.g., bootstrapping) to assess the stability of the selected feature set [37]. 5. Model Interpretation: * Use the final model's feature importance and SHAP analysis to identify and validate the key molecular descriptors driving the predictive activity [41] [11].

GBM-RFE Workflow for Stable Feature Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Resources for GBM-based Molecular Descriptor Research

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Example / Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | Source of bioactivity data for model training. | ChEMBL database [42] |

| Descriptor Calculation | Software to compute molecular features from structure. | RDKit (Python) [42] |

| Gradient Boosting Algorithm | Core machine learning model for robust prediction. | XGBoost, Scikit-learn GBM [41] [39] |

| Feature Selection Wrapper | Integrates with GBM for iterative feature pruning. | Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [42] [41] |

| Model Interpretation Suite | Tools to explain model predictions and feature impact. | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [41] |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Framework for automating model tuning to prevent overfitting. | RandomizedSearchCV, GridSearchCV [41] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Unstable feature selection results across different runs or data splits.

- Solution: Instead of relying on a single run, use a resampling-based feature selection protocol. Perform GBM-RFE on multiple bootstrapped samples of your data. A descriptor's "consistency"—how frequently it is selected across these samples—becomes a more reliable metric of its importance than its rank in a single model [37].

Problem: The final GBM model is complex and difficult to explain to collaborators.

- Solution: Leverage model-agnostic interpretation tools. Create a SHAP summary plot to show the global importance of each descriptor. Furthermore, use SHAP dependence plots to visualize the relationship between a specific descriptor (e.g., Topological Polar Surface Area) and the model's output, which can reveal non-linear effects that linear models would miss [42] [41].

Problem: The model training process is too slow for a large set of molecular descriptors.

- Solution:

- Pre-filtering: Use a fast, univariate feature selection method (like mutual information or F-test) to reduce the descriptor space before applying the more computationally intensive GBM-RFE.

- Efficient Algorithms: Use optimized libraries like XGBoost, which are designed for computational efficiency and can handle large-scale data [39].

GBM Performance Optimization Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is feature selection like RFE critical when building QSAR models with many molecular descriptors? Molecular descriptor sets often contain hundreds of features, many of which may be redundant or irrelevant. Using all descriptors can lead to models that overfit the training data and perform poorly on new compounds [6]. RFE helps by iteratively removing the least important features, which can improve model performance, reduce computational cost, and yield a more interpretable model by identifying the most impactful descriptors [43] [44].

Q2: During RFE, my feature importance rankings change significantly between iterations. Is this normal? Yes, this is an expected and important behavior of RFE, especially when multicollinearity (intercorrelation between descriptors) is present [45]. When a correlated feature is removed, the importance of the remaining correlated features often increases as they now account for the variance previously explained by the removed feature. This re-adjustment is a key advantage of RFE over one-off feature selection methods [45].

Q3: What is the fundamental difference between Scikit-learn's RFE and the implementation in Feature-engine? The core difference lies in the criterion for feature removal.

- Scikit-learn's RFE removes features based solely on the model's intrinsic feature importance (like

coef_orfeature_importances_) [46] [45]. - Feature-engine's RFE removes a feature only if its elimination does not cause the model's performance (e.g., R²) to drop beyond a user-defined threshold [45]. This directly ties feature selection to model performance.

Q4: How can I handle highly correlated descriptors before even starting RFE? A common pre-processing step is to calculate the correlation matrix for all descriptors and remove those with a correlation coefficient above a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.9) [6]. However, this unsupervised method might remove descriptors that are individually informative. An alternative is to use models like Gradient Boosting, which are inherently more robust to multicollinearity [6].

Troubleshooting Guides