Serial Femtosecond Crystallography with XFELs: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions in Structural Biology

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) using X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) represents a paradigm shift in structural biology.

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography with XFELs: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions in Structural Biology

Abstract

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) using X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) represents a paradigm shift in structural biology. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of the 'diffraction-before-destruction' method that enables damage-free, room-temperature structure determination from microcrystals. It details practical methodologies for sample preparation, data collection, and processing, and explores transformative applications in studying membrane proteins like GPCRs and capturing reaction dynamics through time-resolved studies. The article also addresses key technical challenges and optimization strategies, offers a comparative analysis with traditional synchrotron-based crystallography, and discusses the future potential of SFX to accelerate structure-based drug discovery for challenging targets.

The SFX Revolution: Understanding XFEL Fundamentals and the 'Diffraction-Before-Destruction' Principle

X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) represent a revolutionary class of light sources that generate extremely bright, ultrashort X-ray pulses, enabling researchers to probe matter at atomic spatial and femtosecond temporal scales. These facilities have transformed numerous scientific fields, including structural biology, materials science, and drug development, by allowing investigators to "film" chemical reactions, map atomic details of viruses, and study processes occurring deep inside planets [1] [2]. Unlike conventional synchrotron X-ray sources, XFELs produce light through the self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE) process, where high-energy electron beams passing through periodic magnetic structures called undulators emit coherent radiation that amplifies exponentially [3]. The unique "diffraction before destruction" technique enables the determination of damage-free molecular structures at room temperature, providing biologically relevant insights crucial for pharmaceutical development [4] [5]. This application note frames XFEL technology within serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with essential information on facility capabilities, experimental methodologies, and practical tools for leveraging these powerful resources.

Key Properties and Technological Foundations

Fundamental Operating Principles

XFELs generate X-ray flashes through a multi-step process beginning with electron acceleration to high energies, typically in the gigaelectronvolt (GeV) range. These electron bunches are then directed through special arrangements of magnets called undulators, where the particles emit radiation that gets increasingly amplified until an extremely short and intense X-ray flash is created [1]. The fundamental wavelength of the radiation depends on the electron beam energy and undulator parameters according to the equation:

$$\lambda=\frac{{\lambda }_{u}}{2{\gamma }^{2}}\left(1+\frac{{K}^{2}}{2}\right)$$

where λ is the radiation wavelength, λ_u is the undulator period, γ is the Lorentz factor, and K is the deflection parameter [3]. This relationship allows facilities to tune their output across a wide energy range by adjusting these parameters.

Recent technological advances have enhanced XFEL capabilities substantially. Superconducting accelerator technology, operating at -271°C, enables the creation of electron beams of especially high quality composed of many electron bunches, thereby generating significantly more light flashes per second than conventional technologies [6]. Additionally, novel undulator designs like the APPLE-X modules implemented at SwissFEL provide full polarization control, while integrated magnetic chicanes enable tailored pulse properties, reduced saturation lengths, and increased saturation power [3].

Critical Performance Parameters

Several key parameters define XFEL performance for scientific applications:

- Brilliance: XFELs produce X-ray light with brilliance billions of times higher than conventional synchrotron sources, enabling the study of extremely small samples and weak scattering phenomena [1] [2].

- Repetition Rate: The number of X-ray flashes per second varies significantly between facilities, ranging from 60 Hz at PAL-XFEL to 27,000 Hz at European XFEL and an anticipated 1,000,000 Hz at LCLS-II and SHINE [6] [4] [3].

- Pulse Duration: XFELs generate ultrashort pulses typically lasting from a few to hundreds of femtoseconds, fast enough to capture atomic-scale motions during chemical reactions and biological processes [5].

- Photon Energy: Facilities operate across different energy ranges, with "hard" XFELs typically covering 5-20 keV and "soft" XFELs covering lower energy ranges, enabling element-specific studies through access to particular absorption edges [3].

Table 1: Key Performance Parameters of Major XFEL Facilities

| Facility | Country | Start Year | Electron Energy (GeV) | Repetition Rate (flashes/sec) | Min. Wavelength (nm) | Special Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European XFEL | Germany | 2016 | 17.5 | 27,000 | 0.05 | Superconducting technology |

| LCLS | USA | 2009 | 14.3 | 120 | 0.15 | Normal-conducting |

| LCLS-II (SCRF) | USA | 2020 | 5 | 1,000,000 | 0.05 | Superconducting upgrade |

| SACLA | Japan | 2011 | 8.5 | 60 | 0.08 | Compact design |

| SwissFEL | Switzerland | 2016 | 5.8 | 100 | 0.1 | APPLE-X undulators |

| PAL-XFEL | South Korea | 2016 | 10 | 60 | 0.06 | Hard X-ray focus |

| SHINE | China | 2025 | 8 | 1,000,000 | 0.05 | Under construction |

Global XFEL Facility Landscape

The global XFEL landscape has expanded significantly, with currently eight facilities in user operation worldwide and several others under construction or in advanced planning stages [3]. These facilities represent substantial investments in scientific infrastructure and provide complementary capabilities to the international research community.

European XFEL in Germany stands as the world's largest XFEL facility, spanning 3.4 kilometers from the DESY campus in Hamburg to Schenefeld in Schleswig-Holstein [1]. Its superconducting accelerator technology enables unprecedented repetition rates of 27,000 flashes per second, far exceeding other facilities, with six instrument stations currently serving the international user community [6] [2]. The facility's partnership includes 12 countries: Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom [1].

In the United States, the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at SLAC pioneered XFEL operations beginning in 2009, with the LCLS-II upgrade implementing superconducting RF technology to dramatically increase its repetition rate to 1 million pulses per second [6] [3]. SwissFEL at the Paul Scherrer Institute features innovative design elements including APPLE-X undulator modules and integrated chicanes that enable advanced operational modes with precise control over FEL properties including polarization, peak power, and pulse duration [3].

Asian facilities include SACLA in Japan, noted for its compact design, and PAL-XFEL in South Korea, which began operations in 2016 [6] [5]. China's SHINE facility is under construction and expected to begin commissioning in 2025, featuring superconducting technology for high repetition rates [6] [3].

Table 2: Scientific Instrumentation and Experimental Capabilities at Major XFEL Facilities

| Facility | Undulator Technology | Number of Undulators | Number of Experiment Stations | Primary Experimental Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| European XFEL | Superconducting | 3 | 6 | SFX, DX, SP, HED, SCS, MID |

| LCLS | Normal-conducting | 1 | 5 | SFX, XAS, XES, XRS |

| SACLA | Normal-conducting | 1 | 3 | SFX, CDI, XPCS |

| SwissFEL | APPLE-X | N/A | 3 | SFX, non-linear, quantum materials |

| PAL-XFEL | Normal-conducting | N/A | Multiple | SFX, CDI, SAXS/WAXS |

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) Methodologies

Fundamental Principles of SFX

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) using XFELs has emerged as a transformative technique for determining damage-free structures of biological macromolecules at room temperature. Unlike conventional crystallography at synchrotrons, which suffers from both global and specific radiation damage that compromises crystal quality and structural accuracy, SFX leverages the "diffraction before destruction" principle [4]. The ultrashort XFEL pulses (typically tens of femtoseconds) scatter from the crystal sample before the onset of radiation damage, enabling the collection of damage-free structural information [5]. This approach allows data collection at physiological temperatures, providing biologically relevant macromolecular structures that more accurately reflect native states [4].

The technical workflow for SFX involves several critical steps. Crystal samples are exposed to XFEL pulses only once, yielding partial diffraction patterns, thus requiring the collection of thousands to tens of thousands of diffraction patterns to determine a three-dimensional structure [4]. Various sample delivery systems have been developed to serially deliver microcrystals to the X-ray interaction point, including injectors, viscous media injection, and fixed-target scanning methods [4]. Fixed-target (FT) approaches are particularly advantageous for their low sample consumption and reduced physical damage to crystals during data collection [4].

Sample Delivery Systems for SFX

Fixed-target (FT) sample delivery systems provide a straightforward approach for SFX experiments, enabling crystals to be positioned precisely using programmable movements [4]. At PAL-XFEL, the FT-SFX sample chamber features an L-shaped design with a translation stage, sample mounting stage, and pinhole mounting stage [4]. The translation stage, controlled by piezoelectric actuators, moves the fixed target in horizontal and vertical directions, capable of scanning without overlap at the maximum XFEL repetition rate of 60 Hz [4]. Real-time monitoring of fixed targets is enabled by an ultra-long-working-distance microscope and high-speed CMOS camera installed on the chamber [4].

FT sample holders are designed to eliminate the need for synchronization between the sample holder and XFEL beam during data collection, significantly improving experimental efficiency [4]. These holders are constructed from materials that allow XFEL transmission to prevent beam reflection or refraction that could damage detectors [4]. The nylon mesh-based delivery method represents one approach where crystal suspensions are loaded onto the mesh, with excess solution removed to minimize background scattering [4].

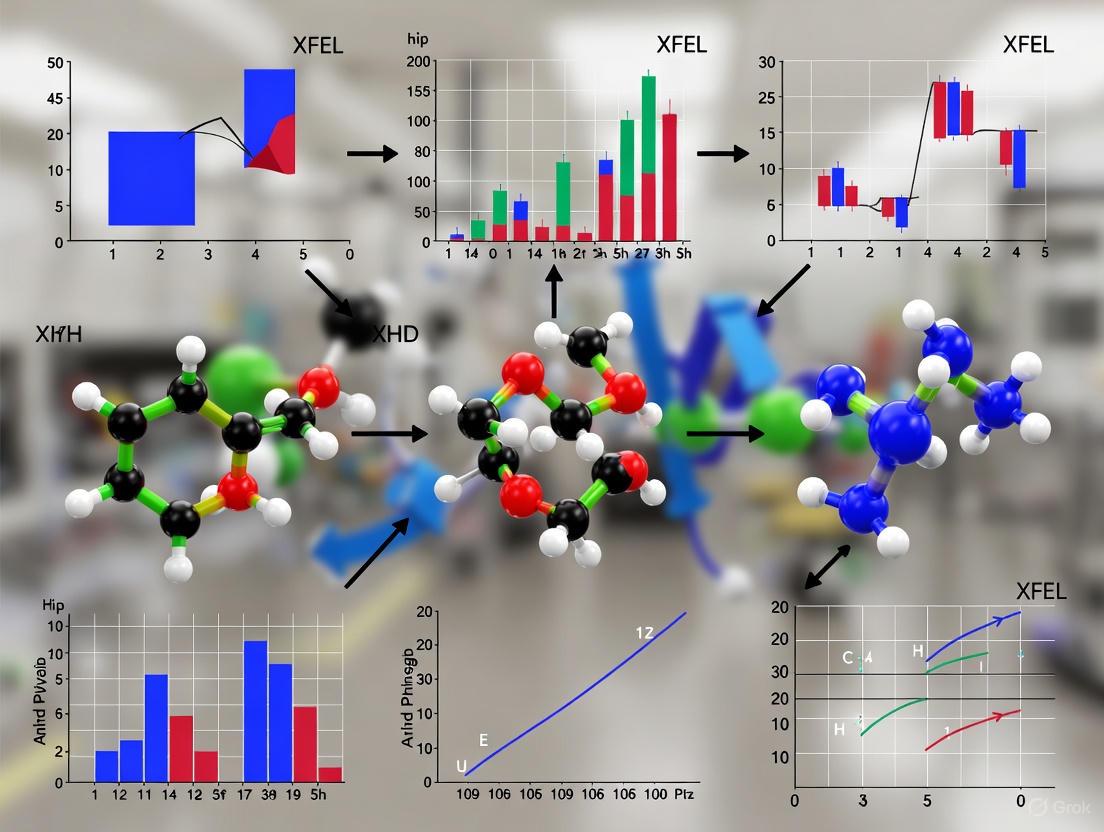

Diagram 1: SFX Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in serial femtosecond crystallography experiments, from sample preparation through data collection and processing.

Time-Resolved SFX Methodologies

Time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography (TR-SFX) enables the visualization of molecular dynamics in real-time, providing unprecedented insights into reaction mechanisms of photoactive proteins and small molecules [5]. TR-SFX experiments observe reaction processes in crystal samples following external stimuli, typically using optical lasers for photoactivation or mixing devices for introducing substrates [5]. The technical implementation requires precise synchronization between the pump (laser or mixer) and probe (XFEL pulse) sources, with timing jitter minimized to femtosecond precision.

At PAL-XFEL, TR-SFX experiments are performed in the Nano Crystallography and Coherent Imaging (NCI) experimental hutch, which features a forward-scattering geometry [5]. The beamline provides X-rays in the energy range of 6-15 keV, with a photon flux of >10¹¹ photons/pulse at 9.7 keV [5]. The XFEL beam is focused using Kirkpatrick-Baez (K-B) mirrors to approximately 2×2 μm at the sample position at 12.4 keV, providing the high photon density necessary for these experiments [5].

Experimental Protocols and Procedures

Sample Preparation and Characterization

Successful SFX experiments require careful sample preparation and characterization. Two sample preparation laboratories (SPLs) located near the NCI experimental hutch at PAL-XFEL provide user groups with facilities for sample preparation before or during XFEL beamtime [5]. These laboratories are equipped with:

- Temperature-controlled incubators for crystal growth optimization

- Centrifuges of various tube sizes for sample processing

- High-resolution microscopes for crystal screening

- Second-order nonlinear imaging of chiral crystals (SONICC) for nanocrystal detection and monitoring [5]

For fixed-target SFX experiments, crystal samples are typically suspended in their mother liquor and deposited onto the sample holder. Excess solution is carefully removed to minimize background scattering while maintaining crystal hydration [4]. The loaded sample holder is then mounted in the FT-SFX chamber, which can be operated under ambient conditions or in a helium environment to reduce air scattering when weak diffraction signals are anticipated [4].

Beamline Instrumentation Setup

The installation and inspection of SFX instruments typically occurs prior to official beamtime. At PAL-XFEL, various studies including SFX and coherent diffraction imaging (CDI) utilize different sample chambers and detectors tailored for specific research purposes [5]. The standard setup procedure includes:

- Replacement of the sample chamber with either a MICOSS (for injector-based delivery) or FT chamber (for fixed-target delivery) positioned on the chamber positioning module (CPM)

- Installation of an MX225-HS detector on the detector stage

- Rough alignment of beamline instruments using a reference laser system on the front side of the CPM

- Fine adjustment of instrument positions using an XFEL beam with the CPM motorized stage [5]

Beamline scientists and engineers typically complete these setup procedures before user groups arrive for their allocated beamtime, ensuring instruments are properly aligned and calibrated for data collection.

Data Collection and Processing

During SFX experiments, data collection is monitored in real-time using the OnDA program or a detector image viewer provided by the MX225-HS detector [5]. The OnDA graphical interface enables diffraction pattern accumulation monitoring, which helps assess data completeness throughout the experiment. The program also calculates Bragg peak intensities and displays hit rates, providing immediate feedback on crystal diffraction quality [5].

Data processing for SFX experiments involves multiple steps:

- Indexing: Diffraction patterns are indexed using algorithms such as XGANDALF (extended gradient descent algorithm for lattice finding) or XDS [5]

- Integration: Bragg spot intensities are extracted and integrated from indexed patterns

- Merging: Partial reflections from thousands of patterns are merged to create complete datasets

- Model Building and Refinement: Structures are determined and refined using programs like COOT for model building and CCP4 suite for refinement [5]

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SFX Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Reagents | Commercial screening kits (e.g., Hampton Research), Precipitant solutions, Buffers | Crystal growth and optimization |

| Sample Support Materials | Nylon meshes, Silicon nitride membranes, Polyimide films | Fixed-target sample mounting |

| Sample Delivery Consumables | GDVN nozzles, DFFN nozzles, High-viscosity injectors | Injector-based sample delivery |

| Cryoprotectants | Glycerol, Ethylene glycol, Paratone-N | Cryo-protection for low-temperature experiments |

| Specialty Chemicals | Substrate solutions, Activation ligands, Photoswitching compounds | Time-resolved and mix-and-inject studies |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Applications in Drug Development and Structural Biology

XFEL-based methodologies have enabled groundbreaking applications in drug development and structural biology. The ability to determine damage-free structures at physiological temperatures provides more accurate information for rational drug design, particularly for membrane proteins and other challenging targets [4]. Time-resolved SFX techniques allow researchers to visualize drug-target interactions in real-time, revealing intermediate states and reaction mechanisms that were previously inaccessible [5].

The mix-and-inject approach enables tracking of enzymatic reactions and drug binding processes by rapidly mixing protein crystals with substrates or inhibitors before XFEL exposure [4] [5]. This technique has been applied to study antibiotic resistance mechanisms, viral replication processes, and signal transduction pathways, providing crucial insights for pharmaceutical development [4]. Furthermore, the capability to collect data from microcrystals enables studies of proteins that resist crystallization in large formats, expanding the range of tractable drug targets.

Emerging Technological Developments

The field of XFEL science continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising technological developments on the horizon. Compact XFEL designs based on laser plasma accelerators (LPAs) represent a significant advancement, potentially making these powerful tools more accessible [7]. Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have demonstrated that LPAs can generate high-quality electron beams with acceleration gradients 1,000 times stronger than conventional linear accelerators, dramatically shrinking the required distance from kilometers to meters [7].

Advanced undulator designs, such as those implemented at SwissFEL, enable precise control over FEL properties including polarization, peak power, and pulse duration [3]. The APPLE-X undulator modules with integrated chicanes allow for operational modes that reduce saturation length by 35% compared to standard configurations and generate more powerful pulses [3]. These developments create new opportunities for scientific discoveries across multiple research disciplines.

Diagram 2: Future Directions in XFEL Technology. This diagram illustrates emerging technological advances and their potential applications in XFEL science.

The ongoing development of high-repetition-rate facilities like LCLS-II and SHINE, capable of generating 1 million pulses per second, will dramatically increase data collection efficiency and enable new classes of experiments [6] [3]. These facilities will particularly benefit high-throughput structural studies and time-resolved investigations of rare intermediate states in biological and chemical systems. As these technologies mature, they will further expand the impact of XFELs on drug development and basic scientific research.

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) represents a transformative methodology in structural biology that leverages the unique properties of X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) to determine macromolecular structures at room temperature with unprecedented temporal resolution [8]. This technique fundamentally differs from conventional crystallography by employing an ultrashort, extremely bright X-ray pulse that traverses the crystal in a femtosecond (10⁻¹⁵ seconds) timescale, enabling the principle of "diffraction-before-destruction" [9]. In practice, SFX involves collecting single diffraction snapshots from thousands of microcrystals delivered in a serial fashion across the XFEL beam, with each crystal providing a partial dataset that computational methods merge into a complete, high-resolution structure [10]. This approach has successfully overcome long-standing limitations in traditional crystallography, particularly radiation damage and the requirement for large, well-ordered crystals, thereby opening new frontiers for studying membrane proteins, radiation-sensitive systems, and transient reaction intermediates that were previously intractable to structural analysis [10] [11].

The genesis of SFX is rooted in the early theoretical proposals and subsequent demonstration experiments at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) in 2011 [8]. The proliferation of XFEL facilities worldwide—including SACLA (Japan), SwissFEL (Switzerland), EuXFEL (Germany), and PAL-XFEL (Korea)—has accelerated methodological advancements and expanded scientific applications [10]. Unlike synchrotron sources that deliver X-rays continuously at lower peak brilliance, XFELs produce pulses with durations of femtoseconds yet deliver as many photons per pulse as synchrotrons deliver per second [10]. This extraordinary peak brilliance enables data collection from smaller and more weakly diffracting samples while the brief pulse duration effectively outruns the manifestation of radiation damage, which fundamentally alters the structural information obtained from sensitive biological samples [10] [9].

Core Principles of SFX

The "Diffraction-Before-Destruction" Principle

The foundational operating principle of SFX centers on the "diffraction-before-destruction" mechanism [9]. When an ultra-intense XFEL pulse interacts with a crystal, the desired X-ray scattering that produces diffraction patterns occurs almost instantaneously on attosecond (10⁻¹⁸ seconds) timescales [10]. However, the subsequent processes that lead to crystal disintegration—including photoionization (~10–100 as), Auger electron emission (femtosecond range), and ionization cascades that cause nuclear motions—occur on slightly longer timescales [10]. Consequently, for XFEL pulses with durations of tens of femtoseconds, the diffraction pattern forms and is recorded before significant radiation damage manifests and the sample is ultimately destroyed [10] [9]. This phenomenon enables the collection of damage-free structural information at room temperature, bypassing the need for cryo-cooling that can alter conformational distributions and preclude time-resolved studies of functional dynamics [10] [9].

The femtosecond duration of data collection effectively eliminates the role of conventional beam damage during the measurement process [12]. This is particularly crucial for studying systems prone to radiation damage, such as metalloproteins containing redox-sensitive metal cofactors or systems with large conjugated structures [10] [9]. In conventional crystallography, even with cryo-cooling, radiation damage accumulates during measurement, often leading to reduced resolution and structural artifacts, especially in small crystals or those with sensitive functional groups [10]. The SFX approach circumvents these limitations entirely by ensuring that the diffraction signal is generated before damage-induced atomic displacements occur, thereby providing more physiologically relevant structural information [9].

Serial Data Collection from Microcrystals

SFX employs a fundamentally different data collection strategy from conventional crystallography. Rather than collecting a complete dataset through rotational shots of a single large crystal, SFX gathers partial "still" images from thousands of microcrystals sequentially delivered into the XFEL beam path [10] [8]. Each crystal is exposed to a single XFEL pulse, producing a diffraction pattern corresponding to a thin slice through reciprocal space at a random orientation [10]. Specialized software then processes these thousands of diffraction patterns by indexing the random orientations, determining partial intensities, and merging them into a complete set of structure factors for phasing and refinement [8].

This serial approach necessitates extremely high throughput data collection, with sample delivery systems designed to replenish crystals at rates commensurate with the XFEL repetition rate [10]. The requirement for numerous microcrystals is offset by several advantages: radiation damage is eliminated since each crystal is used only once; room temperature data collection preserves native conformational states; and the ability to use microcrystals expands the range of accessible targets, including membrane proteins that often form only small crystals in lipidic cubic phase (LCP) [10] [11]. Furthermore, this methodology enables time-resolved studies by capturing short-lived intermediate states through pump-probe approaches, where a reaction is initiated (e.g., by laser light) before the X-ray probe pulse captures the structural state at precisely defined time delays [13].

SFX Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete SFX experimental workflow, from sample preparation to final structure determination:

Sample Preparation and Delivery Systems

Successful SFX experiments begin with the production of high-quality microcrystals, typically ranging from hundreds of nanometers to a few micrometers in size [10]. Microcrystal growth requires optimization of standard crystallization conditions with adjustments to favor numerous small crystals over fewer large ones [10]. Characterization methods such as dynamic light scattering, UV microscopy, and second-order nonlinear imaging of chiral crystals (SONICC) help assess crystal size distribution, quality, and diffraction potential before XFEL experiments [10].

Table 1: SFX Sample Delivery Methods

| Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid jet accelerated by concentric helium stream [8] | Low background scattering [8] | High sample consumption [8] | Soluble proteins, high repetition rate sources [8] |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Injector | Highly viscous mesophase delivery [8] | Low sample consumption, ideal for membrane proteins [8] | Higher background scattering [8] | Membrane proteins, GPCRs [11] |

| Fixed Target Systems | Crystals mounted on silicon chips or loops [8] | Very low sample consumption [8] | Mechanically complex [8] | Precious samples, high-throughput screening [8] |

| Viscous Media Injectors | Grease or other viscous carriers [8] | Reduced sample consumption [8] | High background [8] | Radiation-sensitive samples [8] |

| Tape Drives | Automated crystal deposition on moving tape [8] | Combines low consumption with mechanical simplicity [8] | Limited to lower repetition rates [8] | Intermediate throughput applications [8] |

Sample delivery represents a critical component of SFX experiments, with system selection dependent on the specific sample properties and scientific objectives [10]. The continuous advancement of delivery technologies aims to reduce sample consumption, increase data collection efficiency, and enable new experimental paradigms [8].

Data Collection and Processing Pipeline

SFX data collection involves exposing sequentially delivered microcrystals to XFEL pulses at repetition rates ranging from 10 Hz to megahertz levels, depending on the facility [10]. The diffraction patterns are recorded on high-speed, high-dynamic-range detectors capable of recording single-shot frames [10]. The resulting datasets comprise hundreds of thousands to millions of diffraction patterns, each containing partial reflections from randomly oriented crystals [8].

Data processing follows a well-established computational pipeline [13]:

- Hit Finding: Initial filtering to identify frames containing valid diffraction patterns from crystals, distinguishing them from empty shots or those with only background scattering [13].

- Indexing: Determining the orientation matrix for each crystal using algorithms that analyze the geometric arrangement of Bragg spots [8] [13]. For small-molecule systems with sparse reflections, specialized approaches like graph theory or maximum clique algorithms may be employed [12].

- Integration: Extracting intensity values for each Bragg spot while accounting for partiality—the fraction of the reflection that intersected with the Ewald sphere during the still exposure [8].

- Merging: Combining the partial intensities from all indexed patterns, with appropriate scaling and error modeling, to produce a complete set of structure factors for subsequent phasing and refinement [8] [13].

Specialized software suites like CrystFEL have been developed specifically for processing SFX data, incorporating algorithms optimized for the unique characteristics of serial crystallography datasets [8].

Key Technical Specifications of Major XFEL Facilities

Table 2: XFEL Facility Beamline Parameters for SFX Applications

| Facility (Location) | Beamline | Photon Energy Range (keV) | Repetition Rate | Pulse Duration (fs) | Sample Delivery Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCLS (USA) | MFX | 5 – 24 | 120 Hz | 30 – 100 | GDVN, LCP, Fixed Target [10] |

| LCLS (USA) | CXI | 6 – 25 | 120 Hz | <10 – 100 | GDVN, LCP, Fixed Target [10] |

| SACLA (Japan) | BL3 | 4 – 20 | 30 (60) Hz | <10 | GDVN, LCP, Fixed Target [10] |

| EuXFEL (Germany) | SPB/SFX | 6 – 15 | 1.1 MHz / 4.5 MHz | ~25 | GDVN, Aerosol, Fixed Target [10] |

| SwissFEL (Switzerland) | Alvra | 2 – 12.4 | 100 Hz | - | GDVN, LCP [10] |

| PAL-XFEL (Korea) | NCI/SFX | 2.2 – 15 | 60 Hz | 25 | GDVN, LCP, Fixed Target [10] |

The choice of XFEL facility depends on specific experimental requirements, including desired photon energy, temporal resolution, crystal size, and sample consumption constraints [10]. Facilities like the European XFEL with megahertz repetition rates offer unprecedented data collection speeds but require specialized high-speed delivery systems, while other facilities may offer different specialized capabilities [10] [14].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SFX Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Membrane matrix for crystallization and delivery [11] | Optimal for membrane proteins; provides native-like lipid environment [11] |

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid jet generator for sample delivery [8] | Suitable for soluble proteins; requires substantial sample volumes [8] |

| Viscous Carriers (e.g., Grease) | Medium for crystal suspension and delivery [8] | Redsample consumption; compatible with various crystal types [8] |

| Silicon Chips/Loops | Fixed target substrates [8] | Minimize sample consumption; enable high-throughput screening [8] |

| Cryoprotectants | Preserve crystal quality during handling | Typically not needed for room temperature SFX [9] |

| Microcrystal Suspensions | Primary samples for data collection | Size homogeneity critical for high hit rates [10] |

Applications Overcoming Traditional Limitations

Membrane Protein Structure Determination

SFX has revolutionized membrane protein structural biology, particularly for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which represent approximately 40% of drug targets but have proven exceptionally challenging for traditional crystallography [11]. The ability to collect high-resolution data from microcrystals grown in LCP has enabled determination of structures that were previously inaccessible [11]. GPCRs typically exhibit low expression levels, inherent flexibility, and conformational heterogeneity, making them difficult to crystallize in large, well-ordered crystals [11]. SFX circumvents these limitations by enabling data collection from microcrystals at room temperature, preserving native conformational states and providing insights into mechanistic signaling processes [11]. This advancement has dramatically accelerated structure-based drug discovery for this therapeutically important protein family [11] [15].

Time-Resolved Studies of Reaction Dynamics

The femtosecond pulse duration of XFELs enables time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography (TR-SFX) for capturing short-lived reaction intermediates with atomic resolution [13]. In TR-SFX, a pump pulse (typically laser light) initiates a biochemical reaction in the crystal, followed after a precisely controlled delay by the XFEL probe pulse that captures a structural snapshot [13]. By collecting complete datasets at multiple time delays, researchers can reconstruct molecular movies of functional processes, including enzyme catalysis, photocycles in light-sensitive proteins, and signal transduction mechanisms [13]. This capability provides unprecedented insights into dynamic structural biology that were previously inaccessible, as cryogenic temperatures required for conventional crystallography trap proteins in static conformations and preclude observation of transient intermediates [10] [9].

Radiation-Damage-Prone Systems

SFX has enabled structural determination of proteins containing radiation-sensitive metal centers and cofactors that are often reduced or damaged during conventional X-ray data collection, even under cryogenic conditions [10] [9]. Metalloproteins involved in redox chemistry, such as those containing Fe, Mn, Cu, or other metals with large conjugated systems, are particularly susceptible to radiation damage that alters their electronic and geometric structures [10]. By outrunning damage processes, SFX provides accurate structural information for these systems in their native states, enabling precise characterization of metal-ligand coordination, bond lengths, and active site architectures that are crucial for understanding mechanistic biochemistry [9]. This capability has proven particularly valuable for studying photosynthetic complexes, redox enzymes, and metalloproteins involved in biological energy conversion [10].

Extension to Chemical Crystallography

The application of SFX principles has expanded beyond macromolecular crystallography to small-molecule serial femtosecond crystallography (smSFX) for characterizing beam-sensitive hybrid materials and chemical compounds [12]. Many inorganic-organic hybrid materials form only microcrystals with low symmetry and severe radiation sensitivity, impeding characterization by conventional single-crystal X-ray diffraction or electron microdiffraction [12]. SFX enables room-temperature structure determination of these materials from microcrystalline suspensions without cryoprotection or special handling [12]. This approach has been successfully applied to determine previously unknown structures of silver benzenechalcogenolates and other hybrid materials whose structures had resisted determination by other methods [12]. The ability to conduct these measurements at near-ambient temperature and pressure provides more relevant structural information for materials with potential applications in optoelectronics, catalysis, and energy storage [12].

Serial femtosecond crystallography represents a paradigm shift in structural science, overcoming fundamental limitations of traditional crystallography through the synergistic combination of XFEL technology, advanced sample delivery methods, and sophisticated computational approaches [10] [8]. By eliminating radiation damage through the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle and enabling room-temperature studies of microcrystals, SFX has opened new frontiers in membrane protein structural biology, time-resolved dynamics, and radiation-sensitive systems [10] [11]. The continued development of XFEL sources worldwide, coupled with advancements in sample delivery efficiency and data processing algorithms, promises to further expand the applications and impact of this transformative technology [14]. As SFX methodologies mature and become more accessible, they are poised to accelerate structure-based drug discovery, advance our understanding of biochemical mechanisms, and enable new discoveries across the structural sciences [11] [15].

Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) at X-ray Free-Electron Lasers (XFELs) represents a revolutionary advance in structural biology, enabling the determination of macromolecular structures free from radiation damage. The core principle enabling this breakthrough is "diffraction-before-destruction" [16] [9]. This paradigm leverages the unique temporal structure of XFEL pulses, which deliver extremely high-intensity X-ray photons within femtosecond durations (approximately 10⁻¹⁵ seconds) [10]. These pulses are brief enough to outrun the damaging effects of X-ray irradiation that have long plagued conventional crystallography.

In practical terms, the X-ray scattering that generates the diffraction signal occurs on attosecond timescales (10⁻¹⁸ seconds), while the processes that lead to radiation damage—such as photoionization, Auger electron emission, and ionization cascades—occur on longer femtosecond timescales [10]. Consequently, an XFEL pulse can capture a complete diffraction snapshot before the sample undergoes Coulomb explosion [16] [9]. This fundamental insight has transformed structural biology by allowing researchers to study macromolecules at room temperature with unprecedented accuracy, particularly for systems prone to radiation damage such as metalloproteins and membrane proteins [10] [9] [8].

Technical Foundations of SFX

XFEL Instrumentation and Capabilities

The implementation of the diffraction-before-destruction principle requires specialized XFEL facilities that generate ultrafast, high-brilliance X-ray pulses. These facilities operate with parameters distinctly different from synchrotron sources, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Key XFEL Facility Parameters for SFX Experiments

| Facility | Photon Energy Range (keV) | Repetition Rate | Pulse Duration (fs) | Beam Focus (μm) | Sample Delivery Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCLS (MFX) | 5 – 24 | 120 Hz | 30 – 100 | 3×3 (2×2) | GDVN, MESH, HVE, DoD, Fixed targets |

| EuXFEL (SPB/SFX) | 6 – 15 | 1.1 MHz / 4.5 MHz | ~25 | 3 / <0.4 | GDVN, aerosol injection, HVE, fixed target |

| SACLA (BL3) | 4 – 20 | 30 (60) Hz | <10 | >1 | SF-ROX, fixed targets, GDVN, HVE, DoD |

| SwissFEL (Alvra) | 2 – 12.4 | 100 Hz | - | 1.5 | HVE, GDVN (user supplied) |

| PAL-XFEL (NCI) | 2.2 – 15 | 60 Hz | 25 | 5×5 / 2×2 | GDVN, HVE, fixed targets |

These parameters enable unique experimental possibilities. The high peak brilliance of XFELs (typically >10¹² photons/pulse) allows data collection from micro- and nanocrystals that are too small for conventional synchrotron studies [10]. Furthermore, the ability to conduct experiments at room temperature rather than cryogenic temperatures preserves physiological conformations and enables time-resolved studies of biochemical dynamics [9].

Critical Sample Delivery Systems

Successful SFX experiments require efficient delivery of thousands of fresh crystals into the X-ray interaction point. Various systems have been developed, each with distinct advantages for specific applications, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Sample Delivery Methods in Serial Femtosecond Crystallography

| Delivery Method | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid jet in vacuum accelerated by helium gas [8] | Low background scattering [8] | High sample consumption [8]; Only method for high repetition rate sources [8] | Standard soluble proteins; High repetition rate experiments |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Injector | Viscous medium injection [8] | Low sample consumption [8]; Minimal physical stress on crystals | Relatively high background scattering [8] | Membrane proteins [8] |

| Fixed-Target (FT) Scanning Systems | Crystals mounted on stationary chips or meshes [4] [8] | Very low sample consumption [4]; Precise crystal positioning [4] | Mechanically complex [8]; Requires precise alignment [4] | Precious samples; Low consumption experiments |

| Tape Drive Systems | Crystals on moving tape [8] | Low sample consumption; Fewer moving parts than some FT systems [8] | Limited to compatible crystal types | Routine high-throughput studies |

| Viscous Media Injection | Grease or other viscous carriers [8] | Low sample consumption [8] | High background scattering [8] | Radiation-sensitive systems |

The choice of delivery system represents a critical experimental consideration, balancing factors such as sample consumption, hit rate, background scattering, and compatibility with the specific XFEL beamline parameters [4].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Microcrystal Preparation and Characterization

The SFX workflow begins with the production of high-quality microcrystals typically ranging from 0.5 to 5 micrometers in size [10] [17]. For the model system hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL), an established protocol involves growing microcrystals of approximately 2×2×2 μm in size using a solution of 10% NaCl and 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer at pH 4.0 [17]. The crystal suspension must be filtered through stainless steel frits with pore sizes of 20 and 10 μm to remove larger crystals and aggregates that could clog delivery systems [17]. For fixed-target approaches, crystals are typically deposited onto specially designed sample holders. At PAL-XFEL, for instance, these holders are made of XFEL-transparent materials to prevent beam reflection or refraction that could damage detectors [4].

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection protocols vary depending on the sample delivery method. For injector-based systems, the crystal suspension is typically injected into the X-ray beam using devices such as the Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle. In a documented EuXFEL experiment, researchers used a 3D-printed GDVN with a liquid orifice diameter of 75 μm, gas orifice diameter of 60 μm, and distance between the liquid and gas orifices of 75 μm [17]. The jet velocity is a critical parameter that must be optimized to ensure a fresh crystal is delivered for each X-ray pulse while minimizing sample consumption.

For fixed-target approaches at PAL-XFEL, the sample chamber includes a translation stage with piezoelectric actuators (SLLV42 and SLL12) that move the sample holder in horizontal and vertical directions with high precision [4]. The system includes real-time monitoring using an ultra-long-working-distance microscope (UWZ-300) and a high-speed CMOS camera (mvBlueCOU-GAR-XD) to track sample positioning [4]. Data collection can be performed under ambient conditions or in a helium environment to reduce air scattering when weak diffraction signals are anticipated [4].

Data Processing and Analysis

The SFX data processing workflow involves multiple specialized steps to convert hundreds of thousands of individual diffraction patterns into a coherent electron density map, as visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: SFX Data Processing Workflow

For detectors like the AGIPD at EuXFEL, the calibration process is particularly complex due to the three gain stages required to cover the high dynamic range. The calibration involves: (1) gain stage identification using threshold values, (2) offset correction using calibration constants, and (3) gain correction with appropriate multiplication factors [17]. Following detector calibration, specialized software such as CrystFEL is used for peak finding, indexing, integration, and merging of the partial reflections from thousands of crystal snapshots [8] [17].

A significant challenge in SFX is that typically less than 10% of collected frames contain usable crystal diffraction, making accurate and efficient image classification critical [17]. For time-resolved studies, additional complexities arise in analyzing small structural changes of intermediates with low occupancy. Methods such as jackknifing (taking subsets of unique images) or bootstrapping (random drawing with replacement) are employed to estimate coordinate errors in time-resolved structures [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful SFX experiments require careful selection of specialized materials and reagents. The following toolkit summarizes critical components:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for SFX Experiments

| Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Reagents | 10% NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0) [17] | Standardized conditions for growing microcrystals of model proteins like lysozyme |

| Sample Delivery Media | Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) [8] | Specialized matrix for membrane protein crystal delivery, reducing physical stress on crystals |

| Fixed-Target Materials | Nylon mesh [4], Silicon chips [4] | Substrates for mounting crystals in fixed-target approaches; minimal background scattering |

| Calibration Standards | Hen egg-white lysozyme (HEWL) [17] | Well-characterized model system for beamline calibration and method development |

| Crystal Suspension Solutions | Storage solution with 10% NaCl, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer pH 4.0 [17] | Maintains crystal integrity during data collection |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Structural Biology

The diffraction-before-destruction paradigm has enabled several transformative applications in structural biology and drug development. In membrane protein structural biology, SFX has overcome traditional barriers by allowing structure determination from microcrystals that were previously considered too small for conventional crystallography [10] [9]. This is particularly valuable for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane targets of pharmaceutical interest [8].

In structure-based drug design, SFX provides more accurate information on drug binding pockets by solving structures at ambient temperature with minimal radiation damage [9]. This enables the detection of subtle conformational changes and binding interactions that might be obscured by radiation damage or cryo-artifacts in conventional structures.

For metalloproteins, which contain radiation-sensitive metal cofactors, SFX enables the determination of intact metal-ligand geometries that are often altered by radiation-induced reduction at synchrotrons [9]. This provides more accurate structural information for enzymes like cytochrome P450s, which are important in drug metabolism.

The time-resolved capabilities of SFX allow researchers to track enzymatic reactions with femtosecond resolution, providing unprecedented insights into reaction mechanisms and intermediate states [9] [4]. When combined with mix-and-inject systems, SFX can visualize reaction mechanisms between proteins and substrates or inhibitors, enabling direct observation of drug-target interactions [4].

The diffraction-before-destruction paradigm has fundamentally transformed structural biology by enabling radiation-damage-free structure determination at room temperature. As XFEL facilities continue to evolve with higher repetition rates and improved detectors, the throughput and resolution of SFX experiments will further increase [10] [17]. The ongoing development of more efficient sample delivery methods, particularly fixed-target systems that minimize sample consumption, will make SFX accessible to a broader range of biological systems [4].

Challenges remain in establishing standardized data processing protocols and validation metrics specifically tailored for SFX data [18]. The community is working toward improved standards for data deposition and structure validation to ensure the reliability of structural models derived from SFX experiments [18]. As these technical and computational challenges are addressed, SFX is poised to become an increasingly powerful tool for visualizing biological structures in their native states and advancing structure-based drug design.

Serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) using X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) represents a paradigm shift in structural biology. This technique overcomes two fundamental limitations of conventional cryogenic crystallography: the trapping of proteins in non-physiological conformational states and the pervasive effects of radiation damage. By enabling data collection at room temperature with ultrashort pulses, SFX captures protein structures in functionally relevant states while mitigating radiation damage through the "diffraction before destruction" principle [19]. This application note details the concrete advantages of SFX, supported by quantitative data and practical protocols for researchers in structural biology and drug development.

Core Advantages and Comparative Data

Physiological Relevance of Room-Temperature Structures

Proteins are dynamic machines whose functional mechanisms are often obscured by the cryogenic temperatures required for conventional crystallography. Room-temperature SFX captures this intrinsic flexibility, revealing conformational states that are functionally significant.

A comparative study of the Fosfomycin-resistance protein A from Klebsiella pneumoniae (FosAKP) demonstrated that RT-SFX identified a previously unobserved conformational state of the active site, offering additional starting points for drug design [20]. Similarly, the first room-temperature structure of cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) revealed that several loops were better defined at room-temperature despite the lower resolution of the structure, providing a more accurate picture of the enzyme's native architecture [21].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Room-Temperature vs. Cryogenic Crystallography

| Aspect | Room-Temperature SFX | Conventional Cryo-Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Physiological (≈ 20-25°C) | Non-physiological (≈ 100 K) |

| Protein Conformation | Captures functionally relevant, flexible states [20] | May trap proteins in non-physiological states [22] |

| Active Site Dynamics | Can reveal novel conformational states [20] | May miss relevant conformational diversity |

| Disordered Regions | Better defined loops and flexible regions [21] | Often disordered or obscured |

| Cryoprotectant | Not required | Required, can perturb structure [22] |

Advanced Radiation Damage Mitigation

In conventional crystallography, radiation damage accumulates during measurement, degrading data quality and causing structural artifacts. XFEL's femtosecond pulses outrun key damage processes.

The "diffraction before destruction" principle is fundamental to SFX. Ultrashort, ultrabright XFEL pulses capture the diffraction pattern before the onset of extensive radiation damage that plagues conventional methods [23] [19]. This allows for damage-free structural analysis of sensitive samples, particularly metalloproteins whose metal active centers are susceptible to X-ray photoreduction [19]. Furthermore, the shorter pulse duration outruns the generation of hydrated electrons, which are responsible for breaking chemical bonds in conventional synchrotron experiments [19].

Table 2: Radiation Damage Profile Across Crystallographic Methods

| Damage Mechanism | Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) | Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SMX) | Conventional Cryo-Crystallography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Electronic Damage | Mitigated via femtosecond pulse duration [23] | Present (millisecond exposure) | Present |

| Secondary Damage (Hydrated Electrons) | Outrun (generated on picosecond scale) [19] | Significant | Partially reduced by cryo-cooling |

| Structural Consequences | Essentially damage-free structures [19] | Some radiation damage effects | Cumulative radiation damage |

| Metal Center Photoreduction | Minimized [19] | Can occur | Can occur |

Experimental Protocols for SFX

Microcrystallization of Hen Egg-White Lysozyme

Purpose: To produce high-quality microcrystals for initial SFX trials, detector calibration, and data-collection optimization [19].

Materials:

- Sodium acetate trihydrate

- Acetic acid

- Sodium chloride

- PEG 6000, 50% (w/v)

- Lysozyme (egg white)

- pH meter, filters (0.22 µm), centrifuge tubes, thermomixer, high-performance microscope, CellTrics filter (30 µm)

Procedure:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare 1 M sodium acetate buffer (Buffer A) by adding ~2.5 ml of 1 M sodium acetate to 100 ml of 1 M acetic acid and adjusting to pH 3.0.

- Crystallization Solution: Combine 10 ml of Buffer A with 28 g of sodium chloride and 16 ml of 50% (w/v) PEG 6000. Adjust the final volume to 100 ml with ultrapure water. Mix until all components are fully dissolved and filter through a 0.22-µm filter.

- Harvest Solution: Prepare a solution containing 10% (w/v) sodium chloride and 1 M acetate buffer at pH 3.0.

- Crystallization: Mix the protein solution with the crystallization solution. For 5-µm crystals, incubate the mixture at a constant temperature of 17°C.

- Crystal Harvesting: Once crystals form, concentrate them by centrifugation and resuspend in a small volume of harvest solution. Filter the crystal suspension through a 30-µm mesh to remove large aggregates and ensure uniform crystal size [19].

Fixed-Target Serial Femtosecond Crystallography

Purpose: To collect XFEL diffraction data from protein microcrystals using a fixed-target approach, minimizing sample consumption [24].

Materials:

- Protein microcrystals (e.g., equine skeletal muscle myoglobin)

- Nylon mesh-based sample holder (pore size: 60 µm)

- Polyimide film frames (25 µm thickness)

- Crystallization solution or harvest buffer

Procedure:

- Crystal Loading: Gently resuspend the harvested microcrystals and transfer the suspension onto the nylon mesh of the sample holder.

- Excess Solution Removal: Carefully remove approximately 20 µL of excess solution from the crystal suspension on the mesh to reduce X-ray background scattering.

- Sealing: Immediately cover the crystal suspension with a polyimide film frame to prevent evaporation during data collection.

- Data Collection: Mount the sample holder on a fixed-target translation stage within the XFEL beamline. Raster-scan the holder at fine intervals (e.g., 50 µm). Expose each crystal position to a single XFEL pulse (e.g., 20 fs pulse width, 3x3 µm² beam size) and record the diffraction pattern on a fast-readout detector [24].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated SFX workflow from sample preparation to data collection:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful SFX experiments depend on specialized materials and reagents for sample preparation, delivery, and data collection.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SFX

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Target Sample Holder | Holds microcrystals for raster-scanning by XFEL beam. | Nylon mesh (60 µm pore) on polyimide frame [24]. |

| High-Vacuum Grease | Medium for mixing and presenting small-molecule microcrystals in smSFX. | Dow Corning high vacuum grease [25]. |

| Size-Filtration Mesh | Filters crystal slurry to ensure uniform microcrystal size. | CellTrics filter, 30 µm [19]. |

| Cryo-Protectant | Not required for RT-SFX, but essential for cryo-crystallography. | Various (e.g., glycerol, PEGs) - can perturb structure [22]. |

| Precipitants | Drives protein crystallization. | Ammonium sulfate, PEG 6000 [19] [24]. |

Serial femtosecond crystallography at room temperature provides a powerful framework for advancing structural biology and rational drug design. By providing atomic-resolution insights into proteins under physiological conditions and mitigating the longstanding challenge of radiation damage, SFX enables researchers to visualize previously inaccessible conformational states and dynamic processes. The protocols and data presented herein offer a foundation for leveraging these advantages to uncover novel biological mechanisms and inform the development of new therapeutic agents.

From Microcrystals to Molecular Movies: Practical SFX Workflows and Transformative Applications

Serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) using X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has emerged as a revolutionary technique in structural biology, enabling the determination of high-resolution structures from microcrystals at room temperature while overcoming radiation damage through the "diffract-before-destroy" principle [26] [8]. The success of SFX experiments is fundamentally dependent on the ability to produce large quantities of high-quality nano- or microcrystals with homogeneous size distribution [27]. Unlike traditional crystallography that prioritizes large, single crystals, SFX specifically requires microcrystals typically ranging from 1 to 20 micrometers in size, making method development for microcrystal growth a critical yet relatively unexplored frontier [27] [28].

This protocol outlines essential microcrystallization techniques developed specifically for SFX, using established model systems including photosystem II and cytochrome P450 to demonstrate practical methodologies [27] [21]. We provide detailed protocols, quantitative comparisons, and workflow visualizations to guide researchers in preparing samples that maximize data quality while conserving often-precious biological material.

Essential Microcrystallization Techniques

Core Methodologies and Their Applications

Three primary methods have been developed and optimized for growing microcrystals suitable for SFX experiments. The table below summarizes their key characteristics, requirements, and applications:

Table 1: Comparison of Microcrystallization Techniques for SFX

| Method | Optimal Crystal Size | Sample Consumption | Key Equipment | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Method | 1-10 μm | Moderate | Standard crystallization plates | Proteins crystallizing easily from solution [27] | Limited control over nucleation |

| Free Interface Diffusion (FID) | 1-5 μm | Low | Capillary tubes or microfluidic devices | Membrane proteins; delicate complexes [27] | Requires optimization of diffusion parameters |

| FID Centrifugation | 1-5 μm (highly homogeneous) | Low | Centrifuge, capillary tubes | Producing uniform crystal sizes; difficult-to-crystallize targets [27] | Additional equipment requirement; optimization critical |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | 1-20 μm | Very low | LCP injector or syringe mixer | Membrane proteins (GPCRs, rhodopsins, transporters) [26] | High background scattering; viscous handling |

| Viscous Media Injection | 1-20 μm | Very low | Viscous injector or syringe mixer | Samples requiring extreme sample conservation [26] [8] | High background scattering |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful microcrystallization requires specific materials and reagents tailored to each method. The following table details the essential components:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microcrystallization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycols (PEGs) | Precipitation agent | Molecular weight critical; low MW PEGs (<1000) work best with ultrafiltration [27] |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase Matrix | Membrane protein crystallization matrix | Mimics native membrane environment; used for GPCRs and photosystems [26] |

| Beta-dodecylmaltoside | Detergent for membrane protein solubilization | Maintains protein stability during crystallization [27] |

| High Vacuum Grease | Viscous carrier for fixed-target delivery | Enables sample conservation for small molecules and proteins [28] |

| Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) | Liquid jet sample delivery | Creates focused crystal stream; standard for solution samples [17] [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Batch Microcrystallization Method

The batch method is ideal for initial screening and proteins that crystallize readily from solution.

Materials Required:

- Purified protein (10-20 mg/mL concentration)

- Precipitant solution (typically PEG-based)

- Crystallization plates (96-well or 24-well format)

- Sealing tape

Procedure:

- Prepare protein solution at 10-20 mg/mL in appropriate buffer [27].

- Mix protein and precipitant solutions in a 1:1 to 2:1 ratio directly in crystallization wells.

- Seal the plates and maintain at constant temperature (typically 20°C).

- Monitor crystal growth daily using dynamic light scattering (DLS) or microscopy.

- Harvest crystals when they reach 1-10 μm size (typically 3-7 days).

Optimization Notes:

- For smaller crystals, increase precipitant concentration by 5-10%.

- For more uniform size distribution, optimize protein:precipitant ratio [27].

Free Interface Diffusion (FID) Centrifugation Protocol

This advanced protocol produces highly homogeneous microcrystals ideal for high-resolution SFX.

Materials Required:

- Purified protein (≥10 mg/mL)

- Precipitant solution

- Capillary tubes (0.1-0.5 mm diameter)

- Microcentrifuge

Procedure:

- Load protein solution into capillary tubes using capillary action.

- Carefully overlay with precipitant solution to create a sharp interface.

- Seal tube ends with clay or specialized seals.

- Allow diffusion to proceed for 12-24 hours at constant temperature.

- Centrifuge capillaries at 2000-5000 × g for 5 minutes to concentrate microcrystals.

- Harvest crystals from the bottom of the capillary [27].

Critical Steps:

- Maintain sharp interface during loading for controlled nucleation.

- Optimize centrifugation speed to prevent crystal damage.

- Use second-order nonlinear imaging of chiral crystals (SONICC) for crystal detection [27].

Sample Preparation and Characterization for SFX

Microscopy and Size Characterization:

- Perform optical or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to verify crystal size (1-20 μm in at least two dimensions) [28].

- Ensure crystals are well-separated, not aggregated, for uniform distribution.

Powder X-ray Diffraction (pXRD) for Crystallinity:

- Confirm crystallinity using pXRD with sharp, well-defined peaks [28].

- Reject samples with broad peaks indicating poor crystallinity.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS):

- Use DLS for size distribution analysis and crystal quality assessment [27].

Integrated Workflow for SFX Sample Preparation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from protein purification to data collection:

Troubleshooting and Quality Control

Common Microcrystallization Issues and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Microcrystallization

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No crystals formed | Impure protein, incorrect precipitant | Re-purify protein; screen precipitant conditions |

| Crystals too large | Too low precipitant concentration | Increase precipitant by 5-15%; reduce protein concentration |

| Crystals too small | Too high precipitant concentration | Reduce precipitant by 5-15%; increase protein concentration |

| Irregular size distribution | Uneven nucleation | Implement FID centrifugation; optimize mixing |

| Crystal aggregation | High crystal density or improper handling | Dilute crystal suspension; optimize delivery medium |

Quality Assessment Metrics

Before proceeding to SFX data collection, ensure your microcrystals meet these quality criteria:

- Size Distribution: 1-20 μm in at least two dimensions [28]

- Concentration: 10¹⁰-10¹¹ crystals/mL for liquid injection [27]

- Homogeneity: >80% of crystals within ±2 μm of target size

- Morphology: Well-formed, distinct edges, not aggregated

- Stability: Stable in mother liquor for at least 24 hours

The development of robust microcrystallization techniques has been instrumental in advancing SFX as a powerful method for determining structures of challenging biological targets, particularly membrane proteins and large complexes [27] [26]. The protocols outlined here provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for producing high-quality microcrystals optimized for XFEL experiments. As SFX continues to evolve, particularly in time-resolved studies, further refinement of these microcrystallization approaches will enable unprecedented insights into dynamic structural biology, ultimately facilitating drug discovery efforts and our understanding of fundamental biological processes [21] [29].

Serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) has revolutionized structural biology by enabling room-temperature structure determination of biomolecules without radiation damage, based on the "diffraction-before-destruction" principle [30] [31]. A critical technical challenge in SFX experiments is the rapid and reliable delivery of millions of microcrystals into the X-ray interaction point, matching the repetition rate of the XFEL source [32] [30]. Sample delivery systems have consequently emerged as pivotal components determining the efficiency, sample consumption, and ultimately the success of SFX experiments. This application note provides a comprehensive technical overview of the three primary sample delivery methodologies—liquid injectors, fixed-target scanners, and viscous extruders—with detailed protocols and quantitative comparisons to guide researchers in selecting and implementing optimal delivery strategies for their specific experimental needs.

Liquid Injectors

Liquid injectors propel crystal suspensions in a continuous stream across the X-ray beam, requiring stable jet formation and precise velocity matching to the XFEL repetition rate.

Gas Dynamic Virtual Nozzle (GDVN) Injectors create a narrow liquid jet by focusing a sample stream with coaxial helium gas, achieving jet diameters of 0.3-5 μm at flow rates of 10-30 μL/min [32] [30]. While GDVNs provide stable injection and maintain native crystallization conditions, their high flow rates result in substantial sample waste at current XFEL repetition rates (60-120 Hz), with approximately 1600 crystals wasted between pulses at typical operating conditions [32]. This inefficiency necessitates large sample volumes (∼10 mg protein per dataset) [32].

Particle Solution Delivery (PSD) Injectors utilize tapered capillaries (50-200 μm inner diameter) with coaxial gas focusing similar to GDVNs but with customizable capillary sizes for different crystal types [30]. These systems require high flow rates (20-30 μL/min) for stable liquid streams, making them suitable for solution-based samples but inefficient for precious samples due to significant sample waste [30].

Table 1: Liquid Injector Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | GDVN Injector | PSD Injector |

|---|---|---|

| Jet Diameter | 0.3 - 5 μm | Customizable via capillary ID (50-200 μm) |

| Flow Rate | 10 - 30 μL/min | 20 - 30 μL/min |

| Flow Velocity | ~10 - 100 m/s | Not specified |

| Sample Consumption | High (~10 mg/dataset) | High |

| Key Advantage | Stable jet, maintains native conditions | Customizable for different crystal sizes |

| Key Limitation | High sample waste | High sample consumption |

Fixed-Target Scanners

Fixed-target approaches deposit crystals onto solid supports that are raster-scanned through the X-ray beam, eliminating continuous flow and associated sample waste.

Silicon Micro-Patterned Chips contain regular arrays of wells or through-holes into which crystals self-localize [33] [34]. These devices enable precise positioning and efficient sample usage, with demonstrated hit rates up to 30%—significantly higher than liquid injectors [33]. The Roadrunner translation stage system allows fast raster scanning of chip pores, enabling complete datasets in minutes (e.g., 12 minutes at LCLS) with reduced sample consumption compared to liquid jets [33].

Sheet-on-Sheet (SOS) Devices sandwich crystal slurries between transparent polymer films (typically 2-6 μm thick) without predefined patterning [34]. This approach accommodates diverse crystal sizes (nanocrystals to microcrystals) and growth media (aqueous to viscous matrices) without the constraints of fixed well sizes [34]. SOS devices are cost-effective, using inexpensive polymer films as consumables, and enable visual monitoring of sample distribution and crystal density [34].

Table 2: Fixed-Target Scanner Characteristics

| Parameter | Silicon Patterned Chips | SOS Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Crystal Positioning | Self-localization in wells | Random in sandwich layer |

| Scan Method | Stepwise raster between wells | Continuous raster scanning |

| Hit Rate | Up to 30% | Depends on crystal density |

| Sample Consumption | Low | Very low |

| Compatibility | Limited by well size | All crystal sizes and media types |

| Cost | High (expensive chips) | Low (inexpensive films) |

Viscous Extruders

High-viscosity extrusion (HVE) injectors embed crystals in viscous matrices extruded as continuous streams at dramatically reduced flow rates, minimizing sample waste.

Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Injectors extrude membrane protein crystals in their growth medium at flow rates of 0.02-2.5 μL/min (stream velocity 0.05-4 mm/s) [32] [35]. LCP is particularly valuable for membrane proteins but has limited compatibility with many crystallization solutions used for soluble proteins [35].

Hydrogel-Based Matrices include hydrophilic polymers like sodium carboxymethyl cellulose, Pluronic F-127, hyaluronic acid, and hydroxyethyl cellulose that provide broad chemical compatibility with various crystallization conditions [35] [36]. These matrices produce stable streams with low background scattering and adjustable viscosity [35].

Grease Matrices including mineral oil-based greases, dextrin palmitate/paraffin grease, and dextrin palmitate/DATPE grease offer extreme viscosity for minimal sample consumption (flow rates ~0.5 μL/min) [36]. These matrices enable data collection with less than 1 mg of protein but may produce higher background scattering [36].

Table 3: Viscous Extruder Matrix Properties

| Matrix Type | Viscosity | Flow Rate | Compatibility | Background Scattering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCP | ~500 Pa·s | 0.02 - 2.5 μL/min | Membrane proteins | Low |

| Hydrogels | Adjustable | 0.17 - 3.1 μL/min | Wide, various precipitants | Low to medium |

| Grease Matrices | Very high | ~0.5 μL/min | Wide, but may interact with samples | Medium to high |

Experimental Protocols

GDVN Liquid Injector Operation

Equipment Required: GDVN nozzle assembly, high-pressure HPLC pump or pressure regulator, helium gas supply, three-axis translation stages, vacuum chamber, in-line cameras for jet monitoring [30].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare crystal suspension with concentration ~10⁹ crystals/mL. Filter through appropriate mesh to remove aggregates that may clog nozzle [32].

- Nozzle Priming: Load crystal suspension into sample reservoir. Apply low pressure (1-2 bar) to initiate slow flow through capillary until stable droplet forms at nozzle tip.

- Gas Focusing: Initiate coaxial helium flow at 0.1-0.5 bar pressure to focus liquid stream. Adjust gas pressure until liquid jet diameter reaches 3-5 μm.

- Jet Optimization: In vacuum chamber, gradually increase liquid pressure to achieve stable jet velocity of ~10 m/s. Monitor jet stability using in-line cameras.

- Beam Alignment: Using translation stages, align unbroken section of jet (before Rayleigh-Plateau breakup) with X-ray beam path.

- Data Collection: Maintain jet flow at 10-30 μL/min with X-ray pulses at 60-120 Hz repetition rate. Continuously monitor jet stability and adjust as needed [32] [30].

Troubleshooting:

- Clogging: Reduce crystal concentration or increase filter size. Apply brief pressure pulses to clear partial clogs.

- Jet Instability: Adjust gas-to-liquid pressure ratio. Ensure nozzle tip is clean and undamaged.

- Freezing in Vacuum: Optimize helium sheath flow to provide sufficient cooling prevention [32].

Silicon Chip Fixed-Target Operation

Equipment Required: Micro-patterned silicon chip (e.g., Roadrunner system), crystal suspension, pipettes, blotting tools, fast-scanning XY-raster stages, humidity chamber [33].

Procedure:

- Chip Preparation: Clean silicon chip with appropriate solvent. Place in humidity chamber (>90% RH) to prevent sample dehydration.

- Sample Loading: Pipette 0.5-2 μL crystal suspension onto chip surface. Spread evenly using pipette tip or coverslip.

- Excess Solution Removal: Carefully blot excess mother liquor using filter paper or vacuum suction, leaving crystals trapped in wells/funnels.

- Chip Mounting: Secure loaded chip in holder compatible with translation stages. Maintain high humidity during transfer to beamline.

- Raster Scanning: Program XY stage for sequential scanning of array positions. Set exposure time and step size based on beam size and crystal density.

- Data Collection: Execute raster pattern with X-ray exposure at each position. Monitor hit rate and adjust scanning parameters if needed [33] [34].

Troubleshooting:

- Low Hit Rate: Increase crystal concentration in loading solution. Optimize blotting to retain crystals in wells.

- Sample Dehydration: Maintain >90% RH throughout loading and data collection. Use humidity chamber during preparation.

- Multiple Crystals per Well: Reduce crystal concentration or optimize loading volume [33].

High-Viscosity Extrusion Preparation

Equipment Required: High-viscosity injector (e.g., CMD injector or MLV syringe injector), viscous matrix (LCP, hydrogel, or grease), dual-syringe mixer, HPLC pump for pressure delivery [35] [30] [36].

Procedure:

- Matrix Preparation:

- Crystal Embedding:

- Transfer concentrated crystal suspension to empty syringe.

- Connect to second syringe containing viscous matrix via coupler.

- Mix thoroughly by pushing plungers back and forth between syringes until crystals are uniformly distributed.

- Injector Loading:

- For MLV syringe injectors: Use mixed syringe directly in injector assembly.

- For CMD injectors: Transfer mixture to 40 μL reservoir.

- Stream Optimization:

- Data Collection:

- Align stream with X-ray beam.

- Set flow rate to match XFEL repetition rate (typically 0.1-0.5 μL/min for 30-120 Hz).

- Collect diffraction data with minimal sample waste.

Troubleshooting:

- Stream Curling: Increase matrix viscosity or adjust coaxial gas flow.

- Intermittent Flow: Clear nozzle obstruction or increase pressure. Ensure uniform crystal distribution without aggregates.

- Crystal Damage: Optimize mixing technique to minimize shear forces. Test matrix compatibility with crystals beforehand [36].

Workflow Integration

The sample delivery workflow integrates multiple components from crystal preparation to data collection, with decision points based on sample characteristics and experimental goals. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow and logical relationships between different delivery systems:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GDVN Nozzle | Creates focused liquid jet for crystal delivery | Liquid injection of solution-based crystal suspensions |

| Micro-Patterned Silicon Chips | Provides ordered array for crystal positioning | Fixed-target scanning with precise crystal localization |

| SOS Polymer Films | Forms sandwich for crystal containment without patterning | Fixed-target scanning with diverse crystal types and sizes |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | Viscous matrix for membrane protein crystals | Viscous extrusion of membrane proteins |

| Hydroxyethyl Cellulose | Hydrogel matrix for crystal embedding | Viscous extrusion of soluble proteins |

| Pluronic F-127 | Thermo-reversible polymer for viscosity control | Viscous extrusion with adjustable properties |

| Dextrin Palmitate Grease | High-viscosity matrix for minimal flow rate | Ultra-low sample consumption applications |

| Dual-Syringe Mixer | Homogeneously incorporates crystals into viscous matrices | Sample preparation for viscous extrusion |

| Roadrunner Scanner | High-speed translation stage for fixed-target rastering | Fast data collection from chip-based samples |

| MICOSS Chamber | Multi-purpose injection chamber with visualization and vacuum capabilities | Liquid injection experiments at XFEL facilities |

The selection of an appropriate sample delivery system represents a critical decision point in SFX experimental design, with implications for data quality, sample consumption, and technical feasibility. Liquid injectors provide robust performance for solution samples but incur high sample consumption. Fixed-target approaches maximize sample efficiency, particularly valuable for precious biological samples. Viscous extruders balance continuous delivery with reduced consumption, enabling time-resolved studies. As XFEL facilities continue advancing with increased repetition rates (to 1 MHz and beyond), sample delivery technologies must correspondingly evolve, particularly toward higher-speed fixed-target scanning and optimized viscous delivery matching these repetition rates. The development of novel matrix materials with enhanced compatibility and reduced background will further expand the biological applicability of SFX methods, opening new frontiers in structural biology and drug discovery.