Solving the Far From Most String Problem with GRASP: Advanced Heuristics for Bioinformatics and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) metaheuristic for solving the computationally complex Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP).

Solving the Far From Most String Problem with GRASP: Advanced Heuristics for Bioinformatics and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) metaheuristic for solving the computationally complex Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we cover foundational concepts, detail methodological innovations like hybrid GRASP with path relinking and novel probabilistic heuristics, and address key optimization challenges. The content further validates these approaches through comparative analysis with state-of-the-art algorithms, highlighting their significant implications for biomedical applications such as diagnostic probe design and drug target discovery.

Understanding the Far From Most String Problem and the GRASP Metaheuristic

Defining the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP) and its Core Objective

The Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP) is a combinatorial optimization problem belonging to the class of string selection problems. It involves finding a string that is far, in terms of Hamming distance, from as many strings as possible in a given input set [1].

The core objective is to identify a solution string whose Hamming distance from other strings in an input set is greater than or equal to a specified threshold for as many of those input strings as possible [1]. This problem has significant applications in computational biology, such as discovering potential drug targets, creating diagnostic probes, and designing primers [1].

| Problem Element | Description |

|---|---|

| Instance | A triple ($\Sigma$, $S$, $d$), where $\Sigma$ is a finite alphabet, $S$ is a set of $n$ strings ($S^1, S^2, ..., S^n$), all of length $m$, and $d$ is a distance threshold [1]. |

| Candidate Solution | A string $x$ of length $m$ ($x \in \Sigma^m$) [1]. |

| "Far From" Condition | A solution string $x$ is far from an input string $S^i$ if the Hamming Distance $\mathcal{HD}(x, S^i) \geq d$ [1]. |

| Objective Function | Maximize $f(x) = \sum_{S^i \in S} [\mathcal{HD}(x, S^i) \geq d]$. The goal is to maximize the number of input strings from which the solution string $x$ is far [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Researchers often employ metaheuristics like GRASP (Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure) to tackle the FFMSP due to its NP-hard nature [1] [2]. The following workflow outlines a sophisticated memetic approach that incorporates GRASP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

When conducting experiments with FFMSP, consider these key algorithmic "reagents":

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic | Provides a multi-start framework to generate diverse, high-quality initial solutions for the population [1]. |

| Heuristic Objective Function | Evaluates candidate solutions; an improved heuristic beyond the simple objective f(x) can significantly reduce local optima [2]. |

| Path Relinking | Conducts intensive recombination between solutions in the population, exploring trajectories between elite solutions [1]. |

| Hill Climbing | A local search operator that performs iterative, neighborhood-based improvement on individual solutions [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My GRASP heuristic for FFMSP is converging to local optima too quickly. How can I improve exploration?

A: This is a common challenge. Consider these strategies:

- Integrate Path Relinking: Incorporate a path relinking phase, as done in memetic algorithms, to explore trajectories between high-quality solutions, thus enabling a more strategic search of the solution space [1].

- Use an Improved Heuristic Function: The standard objective function

f(x)can create a search landscape with many plateaus and local maxima. Research has shown that using a more advanced, specialized heuristic function during local search can drastically reduce the number of local optima and guide the search more effectively [2].

Q2: What is the computational complexity of FFMSP, and what are the implications for my experiments?

A: The FFMSP is NP-hard [2]. Furthermore, it does not admit a constant-ratio approximation algorithm unless P=NP [2]. This has critical implications:

- Justification for Heuristics: It justifies the use of metaheuristics like GRASP, memetic algorithms, and other approximate methods, as exact algorithms are unlikely to be efficient for large problem instances.

- Experimental Design: Your experimental framework should focus on evaluating solution quality and computational efficiency on benchmark instances, rather than seeking provably optimal solutions.

Q3: How do I evaluate the performance of my FFMSP algorithm, especially against other methods?

A: A robust evaluation should include:

- Benchmark Instances: Test your algorithm on both randomly generated instances and real-world biological strings to demonstrate its versatility [1].

- Statistical Significance: Perform an extensive empirical evaluation and use statistical tests to show that your algorithm's performance is significantly better than state-of-the-art techniques [1].

- Solution Quality Metrics: The primary metric is the value of the objective function

f(x)—the count of input strings from which the solution is far. Report the best, average, and standard deviation of this value across multiple runs.

The Role of Hamming Distance and Thresholds in String Selection

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary role of Hamming Distance in the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP)?

In the FFMSP, the Hamming Distance is the core metric used to evaluate the quality of a candidate solution. For a problem instance (Σ, S, d), where S is a set of n strings of length m and d is a distance threshold, the objective is to find a string x that maximizes the number of input strings from which it has a Hamming Distance of at least d [1]. The Hamming Distance between two strings of equal length is simply the number of positions at which their corresponding symbols differ [3]. The objective function f(x) is defined as the count of strings in S for which ℋ𝒟(x, Si) ≥ d [1].

Q2: My GRASP heuristic is converging to poor local optima. How can I improve its exploration capability?

This is a common challenge. You can enhance the GRASP heuristic by integrating it with a Memetic Algorithm framework, which combines population-based global search with local improvement. Specifically, you can [1]:

- Intensify Recombination: Use Path Relinking to explore trajectories between high-quality solutions discovered by the GRASP procedure.

- Apply Local Improvement: Employ a hill-climbing algorithm to locally optimize individuals within the population. An empirical study has shown that this GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm with Path Relinking performs better than other state-of-the-art techniques for the FFMSP with statistical significance [1].

Q3: How does the choice of distance threshold d impact the FFMSP's difficulty and the experimental results?

The threshold d directly influences the problem's constrained nature. If d is set too high, it may be impossible to find a string that is far from even a single input string, making the problem infeasible for that threshold. The FFMSP is considered a very hard problem to resolve exactly [1]. In experiments, you must report the threshold value used, as the performance of algorithms can vary significantly with different d values. The table below summarizes the effect of this parameter.

Q4: When should I use Hamming Distance versus Levenshtein Distance for my string selection problem?

The choice is determined by the nature of your input data [3]:

- Use Hamming Distance when you are comparing strings of the same length, as it only allows for substitution operations. This is a standard assumption in the FFMSP [1].

- Use Levenshtein Distance when your strings are of different lengths, as it allows for insertions and deletions in addition to substitutions. Note that for strings of equal length, the Hamming Distance is an upper bound on the Levenshtein Distance [3].

Common Experimental Issues and Troubleshooting

Issue: Inconsistent or Poor-Quality Results from Stochastic Heuristics

- Problem: Your GRASP or Memetic Algorithm produces vastly different results on different runs for the same FFMSP instance.

- Solution:

- Parameter Tuning: Systematically calibrate the algorithm's parameters, such as the greediness factor in the GRASP constructive phase or the population size and mutation rate in the Memetic Algorithm.

- Statistical Reporting: Do not report results from a single run. Perform multiple independent runs (e.g., 30) and report statistical summaries like the mean, standard deviation, and best-found value of the objective function.

- Seeding: For reproducibility, control the random number generator seed during development and testing.

Issue: Unacceptably Long Computation Times for Large Instances

- Problem: The algorithm takes too long to find a viable solution, especially with large

n(number of strings) orm(string length). - Solution:

- Objective Function Optimization: The Hamming distance calculation is called thousands of times. Precompute data where possible and ensure this function is highly optimized.

- Termination Criteria: Implement realistic termination criteria, such as a maximum number of iterations, a maximum time budget, or convergence criteria (e.g., no improvement over

Nsuccessive generations). - Algorithm Selection: For very long strings, consider leveraging heuristic techniques specifically designed for the FFMSP, like the one described in [1], rather than exact methods, which are often infeasible.

Issue: Determining the Correct Distance Threshold d

- Problem: It is unclear what value the distance threshold

dshould take for a given dataset. - Solution:

- Domain Knowledge: The threshold is often problem-specific. In biological applications, for example,

dmight relate to a minimum number of nucleotide differences required for a probe to avoid non-specific binding. - Empirical Analysis: If the context allows, conduct sensitivity analysis by running your experiments across a range of

dvalues to understand its impact on solution quality and algorithm performance. The table below provides a guide for this analysis.

- Domain Knowledge: The threshold is often problem-specific. In biological applications, for example,

Quantitative Data Summaries

| Metric | Allowed Operations | String Length Requirement | Computational Complexity (Naive) | Key Property / Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamming Distance [3] [4] | Substitutions | Must be equal | O(m) | Used in FFMSP, error-correcting codes, and DNA sequence comparison for point mutations. |

| Levenshtein Distance [3] | Insertions, Deletions, Substitutions | Can differ | O(m * n) | Suitable for comparing sequences of different lengths, like in spell check or gene alignment with indels. |

| Damerau-Levenshtein Distance [3] | Insertions, Deletions, Substitutions, Transpositions | Can differ | O(m * n) | Better models human typos by including adjacent character swaps. |

Guide to Distance Threshold (d) Impact

| Threshold Value Range | Expected Impact on FFMSP Solution | Experimental Consideration |

|---|---|---|

d is very low (e.g., close to 0) |

Easy to find a string far from many inputs. The problem becomes less constrained. | Solution quality may be high, but the biological or practical significance might be low. |

d is moderate |

Represents a balanced, challenging problem. | The performance of different algorithms can be most clearly distinguished in this regime. |

d is very high (e.g., close to m) |

Difficult to find a string far from any input. The problem becomes highly constrained. | The objective function f(x) may be low. Feasibility of finding a solution satisfying a high d should be checked. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm for FFMSP

This protocol outlines the methodology for applying a hybrid metaheuristic to solve the Far From Most String Problem, as presented in [1].

1. Problem Initialization

- Input: An instance

(Σ, S, d), whereΣis an alphabet,Sis a set ofnstrings each of lengthm, anddis the distance threshold. - Objective: Find a string

x ∈ Σ^mthat maximizesf(x) = \|{ Si ∈ S : ℋ𝒟(x, Si) ≥ d }\|.

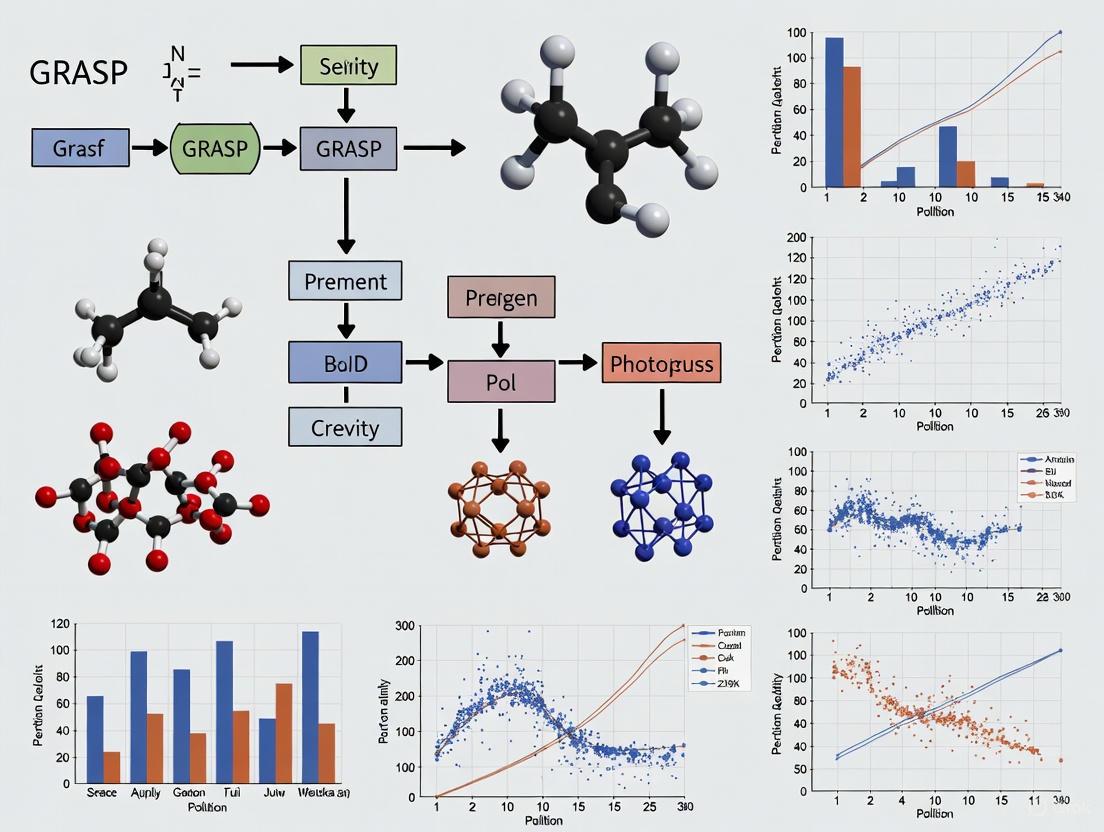

2. Algorithm Workflow The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow of the memetic algorithm.

3. Detailed Methodological Steps

- Step 1: Population Initialization via GRASP

- Use a Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) to generate the initial population of candidate solutions. This involves constructing solutions in a greedy manner while incorporating a degree of randomness to produce a diverse set of starting points [1].

- Step 2: Local Improvement via Hill Climbing

- For each candidate solution in the population, apply a hill-climbing algorithm. This is a local search procedure that iteratively makes small changes (e.g., flipping a single character in the string) to the solution and accepts the change if it improves the objective function

f(x). This step intensifies the search in promising regions of the solution space [1].

- For each candidate solution in the population, apply a hill-climbing algorithm. This is a local search procedure that iteratively makes small changes (e.g., flipping a single character in the string) to the solution and accepts the change if it improves the objective function

- Step 3: Intensive Recombination via Path Relinking

- Select elite solutions from the population and systematically explore trajectories between them. Path Relinking generates new solutions by starting from an "initializing" solution and progressively incorporating attributes from a "guiding" solution. This helps to discover new, high-quality solutions that combine features of the parents [1].

- Step 4: Iteration and Termination

- Iterate the process of local improvement and recombination until a termination condition is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations, a time limit, or convergence is observed). The best solution encountered during the search is returned.

Protocol: Evaluating Distance Threshold Sensitivity

Objective: To analyze the impact of the distance threshold d on the solvability of FFMSP instances and the performance of the proposed algorithm.

Procedure:

- Define Threshold Range: For a fixed FFMSP instance, define a meaningful range of

dvalues to test (e.g., fromd_mintod_maxin stepwise increments). - Run Experiments: For each value of

din the range, execute your algorithm (e.g., the GRASP-based MA) multiple times to account for its stochastic nature. - Data Collection: For each

d, record the average and bestf(x)found, the average computation time, and the number of runs that found a feasible solution. - Analysis: Plot the results to visualize the relationship between

dand the solution quality/algorithm performance. This helps in understanding the problem's phase transition and the robustness of the algorithm.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential computational tools and data types used in FFMSP research, particularly in bioinformatics contexts.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Hamming Distance Calculator | A core function for calculating the number of positional mismatches between two equal-length strings. It is the primary metric for evaluating candidate solutions in FFMSP [4]. |

| GRASP Metaheuristic | A probabilistic search procedure used for generating a diverse initial population of candidate strings. It balances greedy construction with controlled randomization [1]. |

| Memetic Algorithm Framework | A population-based hybrid algorithm that combines evolutionary operators (like selection and recombination) with local search (hill climbing) to effectively explore the solution space [1]. |

| Path Relinking Operator | An intensification strategy that explores the path between high-quality solutions to discover new, potentially better, intermediate solutions [1]. |

| DNA Sequence Dataset (e.g., FASTA) | Real-world biological input data (S). These sequences, representing genomic regions or proteins, are the target strings from which a far-from-most string must be found for applications like diagnostic probe design [1]. |

| Synthetic Benchmark Dataset | Computer-generated string sets of varying size (n) and length (m) used to systematically test and compare the performance and scalability of FFMSP algorithms [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is GRASP and in what context is it used for the Far From Most String Problem? GRASP (Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure) is a multi-start metaheuristic designed for combinatorial optimization problems [5]. Each iteration consists of two phases: a construction phase, which builds a feasible solution using a greedy randomized approach, and a local search phase, which investigates the neighborhood of this solution to find a local optimum [5]. For the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP), the objective is to find a string that is far from (has a Hamming distance greater than or equal to a given threshold) as many strings as possible in a given input set [1]. GRASP has been successfully applied to this NP-hard problem, which has applications in computational biology such as discovering potential drug targets and creating diagnostic probes [1] [2].

Q2: What are the advantages of using a memetic algorithm with GRASP for the FFMSP? A memetic algorithm (MA) that incorporates GRASP leverages the strengths of both population-based and local search strategies [1]. In such a hybrid approach:

- GRASP is often used for the initialization of the population, providing diverse, high-quality starting points for the evolutionary process [1].

- The MA then intensifies the search using operators like path relinking to conduct a structured combination of solutions and hill climbing for local improvement [1].

- This combination has been shown empirically to perform better than other state-of-the-art techniques for the FFMSP with statistical significance, often yielding higher-quality solutions [1].

Q3: My GRASP algorithm is converging to poor-quality local optima. How can I improve its performance? This is a common challenge, particularly in problems like the FFMSP where the standard objective function can lead to a search landscape with many local optima [2]. The following strategies can help:

- Use an Enhanced Heuristic Function: Instead of the problem's standard objective function, employ a more refined heuristic to evaluate candidate solutions during local search. This can significantly reduce the number of local optima and guide the search more effectively [2].

- Incorporate Path Relinking: Use path relinking as an intensification strategy to explore trajectories between elite solutions, which can lead to discovering better solutions [1] [5].

- Adopt a Reactive GRASP Scheme: Implement a self-tuning mechanism for the GRASP parameters, such as the degree of greediness versus randomness in the construction phase, to adaptively respond to the problem instance [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Inconsistent or Poor Solution Quality Across Runs Possible Cause: High sensitivity to the randomness in the construction phase parameters. Solution:

- Systematically tune the key parameters, such as the Restricted Candidate List (RCL) size, which controls the balance between greediness and randomness.

- Consider implementing Reactive GRASP, which adapts the parameter value based on the quality of previously generated solutions [5].

- Increase the number of multi-start iterations, as a higher number of independent trials increases the probability of finding a high-quality solution.

Problem 2: Prolonged Computation Time for Large Problem Instances Possible Cause: The local search phase is computationally expensive, especially with large neighborhoods or complex evaluation functions. Solution:

- Optimize the Heuristic Function: Ensure the heuristic function used for evaluation is as efficient as possible. Profiling the code can identify bottlenecks.

- Use Speed-Up Techniques: Implement strategies like hashing and filtering to avoid re-evaluating previously seen solutions [5].

- Explore Parallelization: GRASP is inherently parallelizable, as multiple construction-and-local-search iterations can be executed concurrently on different processors [5].

Problem 3: Algorithm Struggles with Real Biological Data vs. Random Data Possible Cause: Real biological data often contains structures and patterns that random data lacks, which may not be adequately handled by a general-purpose heuristic. Solution:

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Customize the construction heuristic or the local search moves to leverage known characteristics of biological sequences.

- Hybridize with Other Methods: Combine GRASP with other metaheuristics or problem-specific algorithms to create a more robust solver [5].

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Standard GRASP Protocol for FFMSP

The following workflow outlines a standard experimental procedure for applying GRASP to the FFMSP, which can be enhanced with memetic elements.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes core components of a memetic GRASP with Path Relinking for the FFMSP, as identified in research [1].

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm

| Component | Function / Role | Key Parameter(s) |

|---|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic | Provides a multi-start framework and generates diverse initial solutions. | RCL size, number of iterations. |

| Hamming Distance | Serves as the distance metric to evaluate solution quality against input strings. | Distance threshold d. |

| Hill Climbing | Acts as the local improvement operator, refining individual solutions to local optimality. | Neighborhood structure, move operator. |

| Path Relinking | Functions as an intensive recombination operator, exploring paths between elite solutions. | Pool of elite solutions, path sampling strategy. |

Evaluation Metrics and Comparison

When comparing your GRASP implementation against state-of-the-art techniques, it is crucial to measure the following metrics on both random and biologically-originated problem instances [1] [2].

Table 2: Key Experimental Metrics for Algorithm Evaluation

| Metric | Description | How to Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Quality (Objective Value) | The primary measure of performance; the number of input strings the solution is far from. | Record the best f(x) found over multiple runs. |

| Computational Time | The time required to find the best solution, indicating algorithmic efficiency. | Average CPU time over multiple runs. |

| Statistical Significance | The confidence that the performance difference between algorithms is not due to random chance. | Perform statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test). |

The Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) is a multi-start metaheuristic for combinatorial optimization problems. Each GRASP iteration consists of two principal phases: a construction phase, which builds a feasible solution, and a local search phase, which explores the neighborhood of the constructed solution until a local optimum is found [6] [7]. This two-phase process is designed to effectively balance diversification (exploration of the search space) and intensification (exploitation of promising regions) [6].

In the context of computational biology and drug development, researchers often encounter complex string selection problems. The Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP) is one such challenge. Given a set of strings and a distance threshold, the objective is to find a new string whose Hamming distance is above the threshold for as many of the input strings as possible [8] [2]. Solving the FFMSP has implications for tasks like genetic analysis and drug design, where identifying dissimilar sequences is crucial. However, the FFMSP is NP-hard and does not admit a constant-ratio approximation algorithm, making powerful metaheuristics like GRASP a preferred solution approach [2].

This technical support guide provides researchers and scientists with detailed troubleshooting advice and methodologies for implementing GRASP to tackle the FFMSP and related challenges in bioinformatics.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

1. Why does my GRASP algorithm converge to poor-quality local optima for the FFMSP?

- Problem Analysis: This is a common issue when the heuristic function used during local search fails to effectively guide the search. Using the FFMSP's raw objective function (the count of strings far from the candidate solution) can create a search landscape with many plateaus and local optima, causing search stagnation [2].

- Solution: Implement a more discriminating heuristic function. Research by Mousavi et al. suggests using a function that considers the sum of Hamming distances to all input strings, which provides a finer-grained evaluation of solution quality and helps escape poor local optima [2].

- Recommended Action: Replace the standard objective function with this enhanced heuristic in your local search phase. Experimental results on both random and biological data show this can improve solution quality by orders of magnitude in some cases [2].

2. The construction phase of my GRASP is not generating a sufficiently diverse set of initial solutions. How can I improve it?

- Problem Analysis: Diversity in the construction phase is critical for GRASP to explore the search space widely. If the greedy randomized constructions are too similar, the algorithm is likely to converge to the same region repeatedly.

- Solution: Leverage a Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure specifically for initializing a population of solutions. This method builds solutions one element at a time, selecting from a restricted candidate list (RCL) that contains both high-quality and random choices. This balances greediness and randomization to produce diverse, high-quality starting points [8].

- Recommended Action: For the FFMSP, you can integrate a GRASP-based initialization within a Memetic Algorithm framework, which has been shown to outperform other state-of-the-art techniques with statistical significance [8] [9].

3. How can I enhance my GRASP algorithm to find better solutions without drastically increasing computation time?

- Problem Analysis: After finding local optima, a pure GRASP may struggle to find better solutions in subsequent iterations.

- Solution: Incorporate an intensification strategy like Path Relinking. This technique explores trajectories between high-quality, elite solutions found during the search. It acts as a form of intelligent evolution, generating new solutions that inherit desirable attributes from parent solutions [8] [6] [7].

- Recommended Action: Implement Path Relinking as a post-processing step after the local search. In a Memetic Algorithm for the FFMSP, intensive recombination via Path Relinking combined with local improvement via hill climbing has proven highly effective [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions when implementing GRASP for the FFMSP.

| Research Reagent / Component | Function in the GRASP-FFMSP Experiment |

|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic Framework | Provides the overarching two-phase structure (construction + local search) for the optimization process [6]. |

| Greedy Randomized Construction | Generates diverse and feasible initial candidate solutions for the FFMSP, balancing randomness and solution quality [8]. |

| Enhanced Heuristic Function | Evaluates candidate solutions during local search with greater discrimination than the raw objective function, reducing the number of local optima [2]. |

| Path Relinking | An intensification procedure that explores the solution space between elite solutions to find new, improved solutions [8] [7]. |

| Hill Climbing / Local Search | A iterative improvement algorithm that explores the neighborhood of a solution (e.g., via bit-flips in a string) to find a local optimum [8]. |

| Memetic Algorithm | A hybrid algorithm that combines population-based evolutionary search with individual learning (local search), often using GRASP for population initialization [8]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Standard GRASP for FFMSP with Enhanced Heuristic

This methodology is adapted from successful applications documented in the literature [2].

- Initialization: Define the input set of strings, the distance threshold, and GRASP parameters (e.g., RCL size, maximum iterations).

- Construction Phase:

- Start with an empty candidate string.

- For each character position, create a Restricted Candidate List (RCL) of characters that yield a good greedy myopic score.

- Randomly select a character from the RCL and add it to the candidate string.

- Repeat until a complete string is built.

- Local Search Phase:

- Use an enhanced heuristic function (e.g., sum of Hamming distances) instead of the pure FFMSP objective function.

- Explore the neighborhood of the constructed solution by systematically flipping bits (characters) in the string.

- Accept any change that leads to an improvement according to the enhanced heuristic (first-improve or best-improve strategy).

- Continue until no improving neighbor can be found (local optimum).

- Iteration and Selection: Repeat steps 2 and 3 for a predefined number of iterations. Keep track of the best solution found overall.

Protocol 2: GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm with Path Relinking

This advanced protocol integrates multiple metaheuristics for superior performance [8].

- Population Initialization: Use the GRASP construction heuristic (Protocol 1, Step 2) to generate an initial population of diverse solutions.

- Local Improvement: Apply a hill-climbing local search (Protocol 1, Step 3) to each individual in the population to refine them to local optimality.

- Recombination via Path Relinking:

- Select two or more elite solutions from the population.

- Methodically generate a path in the solution space between these solutions, creating intermediate solutions.

- Apply local search to these intermediate solutions.

- Population Update: Incorporate the new, high-quality solutions found through path relinking back into the population, replacing weaker individuals.

- Termination: Repeat steps 2-4 until a convergence criterion or a maximum number of generations is reached.

The table below synthesizes quantitative results from empirical evaluations of GRASP-based methods, highlighting their effectiveness on the FFMSP.

| Algorithm / Strategy | Key Metric | Performance Findings / Comparative Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| GRASP with Enhanced Heuristic [2] | Solution Quality | Outperformed state-of-the-art heuristics on both random and real biological data; in some cases, the improvement was by "orders of magnitude." |

| GRASP with Standard Heuristic [2] | Number of Local Optima | The search landscape was found to have "many points which correspond to local maxima," leading to search stagnation. |

| GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm with Path Relinking [8] | Statistical Performance | Was "shown to perform better than these latter techniques with statistical significance" when compared to other state-of-the-art methods. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a standard GRASP procedure, integrating both the construction and local search phases.

The diagram below outlines the more advanced hybrid approach of a GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm, which uses a population and path relinking for intensified search.

Key Applications in Bioinformatics and Drug Development

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Bioinformatics Pipeline Errors

Encountering errors in your bioinformatics pipeline can halt research progress. The table below outlines common issues, their possible causes, and solutions.

| Error Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

Pipeline fails with object not found or could not find function errors [10] |

Typographical errors in object/function names; package not installed or loaded [10]. | Check object names with ls(); verify function name spelling; ensure required packages are installed and loaded with library() [10]. |

| Low-quality reads in RNA-Seq analysis [11] | Contaminants or poor sequencing quality in raw data [11]. | Use quality control tools like FastQC to identify issues and Trimmomatic to remove contaminants [11]. |

| Pipeline execution slows significantly [11] | Computational bottlenecks due to insufficient resources or inefficient algorithms [11]. | Profile pipeline stages to identify bottlenecks; migrate workflow to a cloud platform (e.g., AWS, Google Cloud) for scalable computing power [11]. |

Error in if (...) {: missing value where TRUE/FALSE needed [10] |

Logical operations (e.g., if statements) encountering NA values [10]. |

Use is.na() to check for and handle missing values before logical tests [10]. |

| Tool execution fails or produces unexpected results [11] | Software version conflicts or incorrect dependency management [11]. | Use version control (e.g., Git) and workflow management systems (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake); update tools and resolve dependencies [11]. |

| Results are inconsistent or irreproducible [11] | Lack of documentation for parameters, code versions, or tool configurations [11]. | Maintain detailed records of all pipeline parameters, software versions, and operating environment; automate processes where possible [11]. |

Common Drug Development Challenges

The drug development process faces several hurdles that can lead to clinical failure. Here are some key challenges and strategies to address them.

| Challenge | Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of Clinical Efficacy [12] | Accounts for 40-50% of clinical failures [12]. | Employ Structure–Tissue exposure/selectivity–Activity Relationship (STAR) in optimization, considering both drug potency and tissue selectivity [12]. |

| Unmanageable Toxicity [12] | Accounts for ~30% of clinical failures [12]. | Perform comprehensive screening against known toxicity targets (e.g., hERG for cardiotoxicity); use toxicogenomics for early assessment [12]. |

| Unknown Disease Mechanisms [13] | Hinders target identification and validation [13]. | Prioritize human data and detailed clinical phenotyping; utilize multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics) for mechanistic insights [14] [13]. |

| Poor Predictive Validity of Animal Models [13] | Leads to translational failures where efficacy in animals does not translate to humans [13]. | Use animal models to prioritize reagents for clinically validated targets; invest in human cell-based models or microphysiological systems [13]. |

| Patient Heterogeneity [13] | Contributes to failed clinical trials and necessitates larger, more expensive studies [13]. | Increase clinical phenotyping and use biomarkers for patient stratification to create more homogenous trial groups [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary purpose of bioinformatics pipeline troubleshooting?

The primary purpose is to efficiently identify and resolve errors or inefficiencies in data analysis workflows. Effective troubleshooting ensures data integrity, enhances workflow efficiency, improves the reproducibility of results, and prepares pipelines to handle larger datasets [11].

How can GRASP be integrated with bioinformatics in drug discovery?

The DM-GRASP heuristic is a powerful example of such integration. It is a hybrid metaheuristic that combines GRASP with a data-mining process. This allows the method to learn from previously found solutions, making the search for new drug compounds or optimizing molecular structures more robust and efficient against hard optimization problems [15].

What are the most common tools for bioinformatics pipeline troubleshooting?

Popular and indispensable tools include:

- Workflow Management: Nextflow, Snakemake, Galaxy (streamline execution and debugging) [11].

- Data Quality Control: FastQC, MultiQC (assess raw data quality) [11].

- Version Control: Git (ensures reproducibility and tracks script changes) [11].

- Alignment & Mapping: BWA, Bowtie, STAR [11].

- Variant Calling: GATK, SAMtools [11].

Why does 90% of clinical drug development fail, and how can bioinformatics help?

Analyses show clinical failures are due to lack of efficacy (40-50%), unmanageable toxicity (30%), poor drug-like properties (10-15%), and lack of commercial needs (10%) [12]. Bioinformatics helps by:

- Improving Target Validation: Using genomic databases (e.g., OMIM) and comparative genomics to identify and validate high-quality drug targets [16].

- Accelerating Lead Compound Discovery: Using molecular docking and virtual screening to identify potential drugs from large compound libraries more rapidly than high-throughput screening (HTS) alone [14].

- Enabling Drug Repurposing: Analyzing transcriptomic and genomic data to discover new uses for existing approved drugs, significantly reducing development time and cost [16].

How do I ensure the accuracy and reliability of my bioinformatics pipeline?

- Validate Results: Cross-check pipeline outputs using known datasets or alternative analytical methods [11].

- Document Everything: Maintain detailed records of pipeline configurations, tool versions, and all parameters used [11].

- Automate Processes: Use workflow management systems to reduce manual intervention and associated errors [11].

- Engage the Community: Consult tool manuals, community forums, and scientific literature for guidance and best practices [11] [10].

Experimental Workflows & Visualizations

Bioinformatics Pipeline in GRASP-based Research

STAR in Drug Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Item / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Databases [14] | OMIM (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man) | Provides a curated collection of human genes, genetic variations, and their links to diseases, crucial for target identification [16]. |

| SuperNatural, TCMSP, NPACT | Databases containing chemical structures, physicochemical properties, and biological activity of natural compounds, valuable for anticancer drug discovery [14]. | |

| Computational Tools [14] [11] | Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock, GOLD) | Predicts how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a target protein, enabling virtual screening of compound libraries [14]. |

| BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) | Finds regions of local similarity between biological sequences, used to identify homologous genes and proteins [16]. | |

| Phylogeny.fr, ClustalW2-phylogeny | Web-based tools for constructing and analyzing phylogenetic trees, useful for understanding evolutionary relationships in pathogens or disease lineages [16]. | |

| Nextflow / Snakemake | Workflow management systems that enable scalable, reproducible, and portable bioinformatics pipeline deployment [11]. | |

| Key Experimental Concepts | Structure-Tissue exposure/selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR) | A drug optimization framework that classifies candidates based on potency, tissue exposure/selectivity, and required dose to better balance clinical efficacy and toxicity [12]. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | A computational modeling method to relate chemical structure to biological activity, used to screen and optimize lead compounds [14]. |

Computational Complexity and Challenges of Exact FFMSP Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are exact solution methods impractical for the FFMSP? The Far From Most String Problem is considered to be of formidable computational difficulty [1]. Exact or complete methods are often out of the question for non-trivial instances, necessitating the use of heuristic methods to find satisfactory solutions within reasonable timeframes [1].

Q2: What is the formal computational complexity classification of the FFMSP? While the search results do not provide the explicit complexity class (e.g., NP-hard), they consistently emphasize that the problem's resolution has been shown to be "very hard" [1] [9]. This hardness persists even for biological sequence data, which is often subject to frequent random mutations and errors [1].

Q3: How does the GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm circumvent complexity barriers? The MA tackles the FFMSP's hardness by combining several metaheuristic strategies [1]. It avoids exhaustive search through:

- Population initialization via Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP)

- Intensive recombination via path relinking

- Local improvement via hill climbing This hybrid approach efficiently explores the solution space without guaranteeing optimality [1].

Q4: For what instance sizes is the FFMSP considered trivial? The problem becomes trivial when the number of input strings (n) is less than the alphabet size (|Σ|) [1]. In this case, a string far from all input strings can be easily constructed by selecting for each position a symbol not present in that position in any input string [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: GRASP-Based Memetic Algorithm for FFMSP

This protocol outlines the MA described in the search results for tackling the FFMSP [1].

Objective: To find a string that maximizes the number of input strings from which it has a Hamming distance ≥ d [1].

Procedure:

- Problem Instance Definition: Define the input triple (Σ, S, d), where Σ is a finite alphabet, S = {S¹, S², ..., Sⁿ} is a set of n strings each of length m, and d is the distance threshold (1 ≤ d ≤ m) [1].

- Population Initialization: Initialize the solution population using a Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) to generate diverse, high-quality starting solutions [1].

- Memetic Evolution Cycle:

- Recombination: Apply path relinking between population members to intensively explore trajectories connecting promising solutions [1].

- Local Improvement: Perform hill climbing on newly generated solutions to reach local optima [1].

- Evaluation: Calculate the objective function f(x) = Σ [ℋ𝒟(x, Sⁱ) ≥ d] for each candidate solution x, where ℋ𝒟 is the Hamming distance [1].

- Termination: Repeat the evolution cycle until convergence criteria are met (e.g., a fixed number of iterations without improvement).

Validation: Performance is assessed through extensive empirical evaluation using problem instances of both random and biological origin, with statistical significance testing against other state-of-the-art techniques [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function in FFMSP Research |

|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic | Generates a randomized, diverse initial population of candidate solutions for the memetic algorithm [1]. |

| Path Relinking | Conducts intensive recombination between high-quality solutions, exploring trajectories in the solution space [1]. |

| Hill Climbing | Acts as a local search operator within the MA, refining individual solutions to reach local optima [1]. |

| Hamming Distance Metric | Serves as the core distance function (ℋ𝒟) to evaluate the difference between two strings of equal length [1]. |

| Biological Sequence Data | Provides real-world, biologically relevant problem instances for empirical validation of the algorithm [1]. |

FFMSP Problem Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Type/Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alphabet | Σ | Finite set | A finite set of symbols from which strings are constructed [1]. |

| Input Strings | S | Set of n strings | The set of input strings (S¹, S², ..., Sⁿ), each of length m [1]. |

| String Length | m | Integer > 0 | The number of symbols in each input string and the solution string [1]. |

| Distance Threshold | d | Integer (1 ≤ d ≤ m) | The minimum Hamming distance required for a solution to be considered "far" from an input string [1]. |

Memetic Algorithm Performance

| Algorithm Component | Key Metric | Empirical Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Overall MA | Performance vs. State-of-the-Art | Shows better performance with statistical significance compared to other techniques [1]. |

| GRASP Initialization | Population Diversity & Quality | Generates high-quality starting solutions, improving the overall search process [1]. |

| Path Relinking | Recombination Intensity | Enables intensive exploration between promising solutions [1]. |

| Hill Climbing | Local Improvement Efficiency | Refines solutions towards local optima [1]. |

Algorithmic Workflow Visualizations

FFMSP Memetic Algorithm Flow

FFMSP Solution Evaluation

Implementing GRASP for FFMSP: Strategies and Hybrid Approaches

Designing the Greedy Randomized Construction Phase for FFMSP

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary purpose of the Greedy Randomized Construction Phase in GRASP for the FFMSP? This phase constructs an initial, feasible solution for the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP) in a way that balances greediness (making locally optimal choices) with randomization (exploring diverse areas of the solution space). This combination helps avoid getting trapped in poor local optima early in the search process [17].

2. How is the Restricted Candidate List (RCL) built for the FFMSP, and what are common pitfalls? The RCL is built by ranking all possible candidate string symbols for a position based on a greedy function. Only the top candidates, typically those within a certain threshold of the best candidate, are placed in the RCL. A common pitfall is setting the RCL size incorrectly; a list that is too small limits diversity, while one that is too large turns the construction into a random search, degrading solution quality [17] [18].

3. My GRASP algorithm converges to low-quality solutions. How can I improve the construction phase? This often indicates insufficient diversity in the constructed solutions. You can implement a Reactive GRASP approach, where the RCL parameter is self-adjusted based on the quality of solutions found in previous iterations. This allows the algorithm to dynamically balance intensification and diversification [17] [1].

4. What are effective greedy functions for evaluating candidate symbols in the FFMSP construction? The most straightforward greedy function for the FFMSP is the immediate contribution of a candidate symbol to the Hamming distance from the target strings. However, research suggests that using a more advanced heuristic function than the basic objective function can significantly reduce the number of local optima and lead to better final solutions [2].

5. How should I handle the randomization component to ensure meaningful exploration? The randomization should be applied when selecting a candidate from the RCL. The selection is typically done uniformly at random. The key is that the RCL already contains high-quality candidates, so any random choice from it is good, but each choice may lead the search down a different path [17] [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Construction Phase Produces Low-Quality Initial Solutions

Symptoms: The local search phase consistently fails to improve the initial solution significantly, or the algorithm converges to a suboptimal solution across multiple runs.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Check RCL Size:

- Issue: The parameter controlling the RCL size (e.g.,

αor a fixed number of candidates) may be poorly tuned. - Action: Perform a parameter sensitivity analysis. Run your algorithm on benchmark instances with different RCL sizes. A good starting point is a small RCL (e.g., 3-5 candidates) and gradually increase it while monitoring solution quality.

- Issue: The parameter controlling the RCL size (e.g.,

Evaluate Greedy Function:

- Issue: The greedy function may not effectively guide the search.

- Action: Consider a more sophisticated heuristic for evaluating candidate solutions, as the standard objective function can create a landscape with many plateaus [2]. The function should differentiate between candidates that offer similar immediate gains but different future potential.

Verify Randomization:

- Issue: The random number generator may have biases, or the selection from the RCL is not uniformly random.

- Action: Ensure your implementation selects each candidate in the RCL with equal probability. Use a robust pseudo-random number generator.

Problem: Algorithm Lacks Diversity in Constructed Solutions

Symptoms: The initial solutions generated in different GRASP iterations are very similar, leading to the exploration of the same region of the solution space.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Implement Adaptive GRASP:

- Issue: A fixed RCL strategy does not learn from previous iterations.

- Action: Implement a Reactive GRASP variant. Periodically adjust the RCL parameter

αbased on the quality of solutions obtained. If solutions are repetitive, increaseαto allow more diversity [17].

Introduce Bias in RCL Selection:

- Issue: Uniform selection from the RCL may not be optimal.

- Action: Instead of selecting a candidate uniformly, assign a probability proportional to its greedy function value. This introduces a "greedier" randomization while maintaining diversity [17].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Parameter Tuning for the RCL

This protocol helps determine the optimal RCL size for your FFMSP instances.

Methodology:

- Input: Select a set of representative FFMSP instances (both random and biological).

- Parameter: Define a range of values for the RCL parameter (e.g., from 1 to 10, or α from 0.0 to 1.0).

- Execution: For each parameter value, run the GRASP construction phase (without local search) for a fixed number of iterations (e.g., 100).

- Measurement: Record the average objective function value

f(x)of the constructed solutions for each parameter value. - Analysis: Identify the parameter value that yields the best average solution quality.

Expected Output Table:

| RCL Parameter Value | Average Solution Quality f(x) |

Standard Deviation | Best Solution Found |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Greediest) | 14.5 | ± 1.2 | 16 |

| 3 | 16.8 | ± 1.5 | 19 |

| 5 | 17.2 | ± 1.8 | 20 |

| 7 | 16.9 | ± 2.1 | 20 |

| 10 (Most Random) | 15.1 | ± 2.5 | 18 |

Protocol 2: Comparing Greedy Functions

This protocol evaluates the effectiveness of different greedy functions within the construction phase.

Methodology:

- Input: Use a standard set of FFMSP benchmark instances.

- Greedy Functions:

- Execution: For each greedy function, run the full GRASP algorithm (construction + local search) for a fixed number of iterations.

- Measurement: Record the best solution found and the average time per iteration.

Expected Output Table:

| Greedy Function | Best Solution Found (Avg. across instances) | Average Time per Iteration (ms) | Instances Solved to Optimality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Function A | 18.4 | 45 | 4/10 |

| Function B | 21.7 | 52 | 7/10 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and their functions for implementing GRASP for the FFMSP.

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Instance Dataset | A set of input strings S and a threshold d that defines the FFMSP problem instance. Biological data (e.g., sequences from genomic databases) is highly relevant for drug development [1]. |

A set of n strings, each of length m, over an alphabet Σ (e.g., DNA nucleotides). |

| Greedy Function | A heuristic that evaluates and ranks candidate symbols for inclusion in the solution during the construction phase. It drives the "myopic" quality of each choice [2]. | A function calculating the contribution of a candidate symbol to the Hamming distance. |

| RCL Mechanism | A method for creating the Restricted Candidate List, which contains the top-ranked candidates. This is the core component that introduces controlled randomness [17]. | A list built using a threshold value or by taking the top k candidates. |

| Random Selector | A module that pseudo-randomly picks one element from the RCL. This ensures diversity in the search paths explored by different GRASP iterations [1] [17]. | A uniform random selection function from a list. |

| Solution Builder | A procedure that sequentially constructs a solution string by assigning a symbol to each position, based on the output of the greedy function and RCL selector [1]. | Starts with an empty string and iterates over m positions. |

| Local Search Heuristic | An improvement procedure (e.g., hill climbing) applied after the construction phase to refine the initial solution to a local optimum. This is part of the full MA but is crucial for performance [1]. | Explores the neighborhood of the constructed solution by flipping single characters. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and data relationships within the Greedy Randomized Construction Phase of GRASP for the FFMSP.

GRASP Construction Phase Workflow

This diagram details the internal logic for building the Restricted Candidate List (RCL), a critical step in the construction phase.

RCL Building Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does Hill Climbing integrate within the GRASP-based memetic algorithm for the FFMSP? In the proposed GRASP-based memetic algorithm, Hill Climbing acts as the local improvement phase following intensive recombination via path relinking. It leverages a heuristic objective function to perform iterative, neighborhood-based searches to elevate solution quality, moving candidate strings towards a local optimum after initial population initialization by GRASP [8].

Q2: My iterative improvement process is stagnating at local optima for biological sequence data. What advanced techniques can help? The GRASP-based memetic algorithm combats local optima stagnation through two key mechanisms. First, the GRASP metaheuristic in the initialization phase builds a diverse, randomized population. Second, path relinking conducts intensive recombination between solutions, exploring trajectories in the search space that Hill Climbing alone might miss, thus enabling escapes from local optima [8].

Q3: What are the critical parameters to monitor when applying Hill Climbing to the FFMSP? While the specific parameter set for the MA was determined via an extensive empirical evaluation, key aspects generally critical for Hill Climbing performance include the definition of the neighborhood structure (how one string is mutated to form a neighbor) and the choice of the objective function that guides the ascent. Sensitive parameters should be tuned for the specific instance type (random or biological) [8].

Q4: Why is the GRASP metaheuristic particularly suited for initializing the population in FFMSP research? GRASP is well-suited for FFMSP because it constructively builds solutions using a greedy heuristic while incorporating adaptive randomization. This effectively produces a population of diverse, high-quality initial candidate strings, providing a superior starting point for the subsequent memetic algorithm components like Hill Climbing and path relinking, compared to a purely random or purely greedy initialization [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Premature Convergence in Hill Climbing

Symptoms

- The algorithm's objective function value plateaus early.

- Identical or very similar solutions are repeatedly generated.

- Performance is significantly worse on larger or more complex problem instances.

Resolution Steps

- Verify Population Diversity: Ensure the GRASP initialization phase is configured with sufficient randomization. A population of highly similar solutions limits the effectiveness of subsequent local search.

- Integrate Path Relinking: Implement the intensive recombination via path relinking as described in the MA. This explores new trajectories between high-quality solutions, helping the algorithm escape local optima that trap the Hill Climbing routine [8].

- Re-evaluate Neighborhood Structure: Examine how neighboring solutions are defined for the Hill Climbing step. A broader or differently structured neighborhood might reveal better ascent paths.

Problem 2: Inconsistent Performance on Biological vs. Random Instances

Symptoms

- Algorithm performs well on synthetic/random data but poorly on real biological sequences, or vice-versa.

- Parameter sets are not transferable between instance types.

Resolution Steps

- Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Conduct a thorough parameter sensitivity analysis, as was done for the MA. Use a representative set of instances from both categories (biological and random) to find robust parameter values [8].

- Benchmark Against State-of-the-Art: Compare your results with the proposed MA and other existing techniques. The MA was shown to perform better than other techniques with statistical significance, providing a strong benchmark [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Methodology for the GRASP-based MA

The following protocol was used to validate the performance of the memetic algorithm incorporating Hill Climbing [8]:

- Instance Generation: Create problem instances of both random and biological origin.

- Algorithm Configuration:

- Initialize the population using a GRASP metaheuristic.

- Apply intensive recombination via path relinking.

- Execute local improvement via Hill Climbing using a problem-specific heuristic objective function.

- Evaluation: Conduct an extensive empirical evaluation to:

- Assess parameter sensitivity.

- Draw performance comparisons with other state-of-the-art techniques using statistical significance tests.

Performance Comparison Data

The table below summarizes quantitative results showing the performance advantage of the proposed MA.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Algorithms on FFMSP Instances

| Algorithm / Technique | Performance Metric (Relative to MA) | Statistical Significance vs. MA |

|---|---|---|

| GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm (MA) with Hill Climbing | Baseline | N/A |

| Other State-of-the-Art Technique 1 | Worse | Significant [8] |

| Other State-of-the-Art Technique 2 | Worse | Significant [8] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Components for FFMSP Experiments

| Item/Component | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic | Provides a diverse set of high-quality initial candidate solutions for the population. |

| Path Relinking Operator | Enables intensive recombination between solutions, exploring new search trajectories. |

| Hill Climbing Local Search | Iteratively improves individual solutions by moving them to better neighbors in the search space. |

| Heuristic Objective Function | Guides the Hill Climbing and GRASP procedures by evaluating solution quality for the FFMSP. |

Algorithm Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the high-level workflow of the GRASP-based memetic algorithm, highlighting the role of Hill Climbing.

Hybrid GRASP with Path Relinking for Solution Intensification

This technical support center is framed within ongoing thesis research focused on applying a Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP) hybridized with Path-Relinking to tackle the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP). The FFMSP is a computationally challenging string selection problem with significant applications in computational biology and drug development, where the objective is to identify a string that maintains a distance above a given threshold from as many other strings in an input set as possible [8] [9]. The integration of Path-Relinking into the GRASP metaheuristic serves as a crucial intensification mechanism, enhancing the algorithm's ability to find high-quality solutions by systematically exploring trajectories between elite solutions discovered during the search process [19] [20]. This document provides essential troubleshooting and methodological guidance for researchers and scientists implementing this advanced hybrid algorithm.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Algorithm Convergence Issues

Q1: The algorithm appears to stagnate, repeatedly finding similar sub-optimal solutions without improving. What might be causing this, and how can it be resolved?

| Problem Area | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Path-Relinking | Insufficiently diverse elite set [19] | Implement a more restrictive diversity policy for elite set membership. |

| Local Search | Limited neighborhood exploration [8] | Combine hill climbing with periodic perturbation strategies to escape local optima [8]. |

| GRASP Construction | Lack of randomization in greedy choices [20] | Adjust the Restricted Candidate List (RCL) parameter (\alpha) to balance greediness and randomization [20]. |

| General Search | Premature termination of path-relinking [19] | Ensure path-relinking explores the entire path between initial and guiding solutions. |

Guide 2: Managing Computational Expense

Q2: The runtime of the hybrid algorithm is prohibitively high for large biological datasets. What optimizations can be made?

| Symptom | Diagnostic Check | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Slow individual iterations | Profile the code to identify bottlenecks. | Use efficient data structures for string distance calculations [8]. |

| Too many iterations without improvement | Monitor the percentage of improving moves. | Implement a reactive GRASP to adaptively tune parameters like (\alpha) [20]. |

| Path-relinking is slow | Check the number of elite solutions used. | Limit the number of elite solutions used in path-relinking or use a sub-set selection strategy [19]. |

| Memory usage is high | Check the size of the elite set. | Enforce a fixed maximum size for the elite set, replacing the worst solution when needed [20]. |

Guide 3: Handling Infeasible or Poor-Quality Solutions

Q3: The algorithm frequently generates solutions that do not meet the required distance threshold for a sufficient number of strings. How can this be improved?

| Issue | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low solution quality | The construction phase is not generating sufficiently robust starting points. | Incorporate a learning mechanism, such as data mining the elite set to guide the construction phase [21]. |

| Infeasible solutions | The objective function does not penalize infeasibility strongly enough. | Employ a heuristic objective function during the local search that specifically targets the violation of the distance constraints [8]. |

| Failed intensification | Path-relinking is not effectively connecting high-quality solutions. | Apply a local search to the best solution found during the path-relinking phase, not just the endpoints [19] [20]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Workflow for the Hybrid GRASP with Path-Relinking

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the memetic algorithm, integrating GRASP, hill climbing, and Path-Relinking.

Key Parameter Configuration Table

The performance of the algorithm is highly sensitive to its parameters. The table below summarizes key parameters, their functions, and typical values or strategies for initialization based on empirical studies [8] [20].

| Parameter | Function | Empirical Setting / Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| RCL Parameter ((\alpha)) | Controls greediness vs. randomization in construction. | Use reactive GRASP: start with (\alpha = 0.5), adapt based on iteration quality [20]. |

| Elite Set Size | Number of high-quality solutions used for Path-Relinking. | Typically small (e.g., 10-20); critical for balancing memory and computation [19]. |

| Stopping Criterion | Determines when the algorithm terminates. | Max iterations, max time, or iterations without improvement (e.g., 1000 iterations) [8]. |

| Distance Threshold | Defines the target distance for the FFMSP. | Problem-dependent; should be calibrated on a validation set of known instances [8]. |

| Path-Relinking Frequency | How often Path-Relinking is applied. | Can be applied every iteration, or periodically (e.g., every 10 iterations) [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of hybridizing GRASP with Path-Relinking for the FFMSP? The primary advantage is the introduction of a memory mechanism and intensification strategy. While traditional GRASP is a memory-less multi-start procedure, Path-Relinking systematically explores the solution space between high-quality solutions (the current solution and an elite solution from a central pool), leading to a more effective search and statistically significant improvements in solution quality [19] [8].

Q2: When should a specific pencil grasp be addressed or considered functional? Note: This question appears to stem from a conceptual confusion with the term "GRASP." In our context, GRASP is a metaheuristic algorithm, not a physical grip. The following answer clarifies this distinction for our research audience. This troubleshooting guide pertains to the Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure (GRASP), a metaheuristic for combinatorial optimization. It is not related to occupational therapy or pencil grip. A "grasp" in our context refers to the algorithm's greedy and randomized strategy for constructing solutions. A functional "grasp" in this algorithmic sense is one that effectively balances greediness (making the best immediate choice) and randomization (allowing for exploration) via the RCL parameter (\alpha) [20].

Q3: How does the data mining hybridization with GRASP and Path-Relinking work? This advanced hybridization involves extracting common patterns (e.g., frequently occurring solution components) from an elite set of previously found high-quality solutions. These patterns, which represent characteristics of near-optimal solutions, are then used to bias the GRASP construction phase. This guides the algorithm to focus on more promising regions of the solution space, which has been shown to help find better results in less computational time compared to traditional GRASP with Path-Relinking [21].

Q4: What are the best practices for validating results from this algorithm on biological string data?

- Benchmarking: Use publicly available biological sequence datasets and compare your results against known optimal solutions or state-of-the-art algorithms [8].

- Statistical Significance: Perform multiple independent runs and use statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to confirm that performance improvements are significant [8].

- Biological Validation: For drug development applications, the resulting strings (e.g., candidate peptides or DNA sequences) should undergo in silico validation, such as docking studies or homology modeling, to assess their potential biological relevance and activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational "reagents" and components essential for implementing the featured hybrid algorithm.

| Item | Function in the Experimental Setup |

|---|---|

| GRASP Metaheuristic Framework | Provides the multi-start backbone for generating diverse, high-quality initial solutions via a randomized greedy construction and local search [20]. |

| Path-Relinking Module | Acts as an intensification reagent, exploring trajectories between solutions to uncover new, superior solutions and introducing a strategic memory element [19]. |

| Elite Solution Set | A restricted memory pool that stores the best and/or most diverse solutions found during the search, serving as guiding targets for the Path-Relinking process [19]. |

| Hill Climbing Local Search | A fundamental local improvement operator used to ascend local gradients of solution quality, ensuring that solutions are locally optimal before Path-Relinking [8]. |

| Heuristic Objective Function | A problem-specific function that evaluates solution quality; for the FFMSP, this function efficiently counts strings beyond the distance threshold [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using a GRASP-based Memetic Algorithm for the Far From Most String Problem (FFMSP)? The primary advantage is the effective synergy between global exploration and local refinement. The GRASP (Greedy Randomized Adaptive Search Procedure) component constructs diverse, high-quality initial solutions, providing a strong starting point for the population [1] [22]. The memetic framework then intensifies the search by applying local search (like hill climbing) to these solutions, enabling a more thorough exploitation of promising regions of the search space, which is crucial for tackling the computational hardness of the FFMSP [1].

FAQ 2: My algorithm is converging to solutions prematurely. How can I improve population diversity? Premature convergence often indicates an imbalance between exploration and exploitation. You can address this by:

- Implementing Path Relinking: Use this strategy to explore trajectories between high-quality solutions, generating new intermediate solutions and maintaining diversity [1].

- Controlling Population Diversity: Introduce mechanisms for population diversity control in the decision space. This can be achieved through fuzzy systems that self-adapt control parameters, such as crossover rate and scaling factor, based on current population metrics [23].

- Reviewing Local Search Intensity: Overly aggressive local search can lead to premature convergence. Consider implementing a controlled local search procedure or using a saw-tooth function to manage the application of local search and prevent excessive exploitation [23].

FAQ 3: How do I set the parameters for the local search component within the MA? There is no universal setting, as it is often problem-dependent. A recommended methodology is to use a self-adaptive mechanism. For instance, you can control the local search intensity based on the population's state. If diversity drops below a threshold, reduce the local search effort to allow for more exploration. Alternatively, you can use a fixed iteration limit or a probability for applying local search to offspring, which should be tuned experimentally for your specific FFMSP instance [23].

FAQ 4: The algorithm finds good solutions but takes too long. Are there ways to improve computational efficiency? Yes, several strategies can enhance efficiency:

- Parallelization: The evaluation of solutions in a population is often independent and can be parallelized. Look for loops in your algorithm that can be executed concurrently, such as the evaluation of offspring or the application of local search to multiple individuals [22].

- Heuristic Objective Function: As used in the FFMSP MA, a well-designed heuristic objective function can guide the search more effectively, reducing the number of futile evaluations [1].

- Selective Local Search: Avoid applying local search to every individual. Instead, focus it only on the most promising solutions or when the search shows signs of stagnation [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Initial Population Leading to Slow Progress

- Symptoms: The algorithm takes a very long time to find any high-quality solutions; the initial population seems to be of low quality.

- Possible Causes:

- Random initialization is used, which does not leverage problem-specific knowledge [22].

- The GRASP constructive heuristic is poorly designed or its randomness is not adequately controlled.

- Solutions:

- Seeded Initialization: Replace random initialization with a GRASP metaheuristic. GRASP builds solutions iteratively using a greedy function but introduces randomness in the selection process to create a diverse and high-quality initial population [1] [22].

- Problem-Specific Greedy Heuristic: Ensure the greedy heuristic within GRASP is tailored for the FFMSP. For example, when building a string symbol-by-symbol, the greedy function could prioritize choosing symbols that maximize the Hamming distance to the nearest string in the input set.

Problem 2: Local Search Fails to Improve Solutions

- Symptoms: The local search procedure is running but does not yield fitness improvements, or it gets stuck in local optima.

- Possible Causes:

- The neighborhood structure is too small or not effectively defined for the FFMSP.

- The local search is being applied too greedily, accepting only improving moves.

- Solutions:

- Define an Effective Neighborhood: For a string in FFMSP, a neighborhood can be defined by all strings that differ in exactly one symbol (Hamming distance of 1). A larger neighborhood could involve flipping a small, random number of symbols [1].

- Incorporate a Tabu Operator: Use a short-term memory (tabu list) to prevent the search from revisiting recently explored solutions. This helps the local search escape local optima by forcing exploration of new areas [24].

- Use a Controlled Local Search: Implement a local search procedure that is guided by the overall population diversity. Reduce its intensity when diversity is low to favor exploration over exploitation [23].

Problem 3: Difficulty in Tuning Control Parameters

- Symptoms: Small changes in parameters (e.g., mutation rate, crossover rate, local search probability) lead to wildly different performance; finding a good parameter set is tedious.

- Possible Causes:

- Manual parameter tuning is inefficient and often does not find a robust configuration.

- The optimal parameter values may change as the search progresses.

- Solutions:

- Implement Self-Adaptation: Use fuzzy systems or other adaptive mechanisms to dynamically control parameters. For example, a fuzzy system can adjust the Differential Evolution's crossover rate and scaling factor based on feedback from the search process, such as the current population diversity or improvement rates [23].

- Parameter-less or Adaptive Schemes: Design the algorithm with in-built adaptation. For instance, the probability of applying local search could decay over generations, or be triggered only when no improvement is found for a number of iterations.

Problem 4: Unbalanced or Low-Quality Final Solutions

- Symptoms: The final solution set for the FFMSP has poor objective function values, fails to be far from many strings, or lacks diversity in the case of multi-objective optimization.

- Possible Causes:

- The objective function may not effectively guide the search.

- The evolutionary operators (crossover, mutation) are not well-suited for the string-based representation.

- Solutions:

- Exploit a Specialized Crossover Operator: Design a crossover that is aware of the FFMSP structure. For example, a crossover could preferentially inherit symbols from parent solutions that contribute most to being "far" from the input strings [24].

- Layered Operator Application: Structure your MA as a sequence of layers, where each layer applies a different operator (e.g., one for recombination, one for mutation, one for local search). This ensures a balanced and synergistic application of all search components [22].

- Enhanced Selection Pressure: In multi-objective scenarios, use selection methods that consider both non-domination rank and a diversity measure (like crowding distance) to ensure the final population is both high-quality and well-spread along the Pareto front [23].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: GRASP-Powered Initialization for FFMSP

This methodology is used to generate the initial population for the Memetic Algorithm [1].

- Repeat for each individual in the population:

- Construct a Solution:

- Start with an empty string

s. - For each string position

ifrom 1 tom(string length):- Evaluate the greedy function for all candidate symbols

cin the alphabetΣ. For FFMSP, this function could estimate the potential ofcto help make the final string far from the input strings (e.g., based on Hamming distance). - Build a Restricted Candidate List (RCL) containing the best-performing symbols (e.g., those with the highest greedy value).

- Select a symbol randomly from the RCL and set

s[i] = c.

- Evaluate the greedy function for all candidate symbols

- Start with an empty string

- Apply a Local Search (e.g., hill climbing) to the constructed solution