Solving the Knock-In Challenge: A Comprehensive Guide to Boosting CRISPR Efficiency in Primary Cell Cultures

Achieving high-efficiency CRISPR-mediated knock-in in primary cells remains a significant bottleneck in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Solving the Knock-In Challenge: A Comprehensive Guide to Boosting CRISPR Efficiency in Primary Cell Cultures

Abstract

Achieving high-efficiency CRISPR-mediated knock-in in primary cells remains a significant bottleneck in biomedical research and therapeutic development. This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational biology of primary cells, state-of-the-art methodological approaches, advanced troubleshooting strategies, and robust validation techniques. By synthesizing recent scientific advances, we outline practical solutions to overcome key challenges such as low HDR rates and primary cell sensitivity, enabling more reliable and efficient genome engineering for advanced disease modeling and cell therapy applications.

Understanding the Unique Challenges of Primary Cells in Genome Editing

FAQ: Fundamental Biological Differences

What are the core biological differences between primary and immortalized cells?

Primary cells are isolated directly from living tissue and have a finite lifespan, undergoing a limited number of divisions before reaching senescence. In contrast, immortalized cell lines have acquired the ability to proliferate indefinitely, typically through accumulated or induced genetic mutations that bypass normal cellular senescence mechanisms [1].

Key Biological Differences:

| Characteristic | Primary Cells | Immortalized Cells |

|---|---|---|

| Lifespan & Senescence | Finite (Hayflick limit); undergo senescence [2] | Infinite proliferation; bypassed senescence |

| Genetic Background | Normal, diploid genome | Often aneuploid; accumulated mutations [3] |

| Physiological Relevance | High; maintain original tissue morphology and function [1] | Low; often derived from cancers, optimized for proliferation [4] |

| Growth Characteristics | Slow, limited divisions in culture [1] | Fast, robust, easy to culture [1] [4] |

| Response to DNA Damage | Intact cell cycle checkpoints and repair pathways | Frequently altered p53/INK4a/ARF pathways [5] [6] |

Why is CRISPR knock-in efficiency inherently lower in primary cells?

Knock-in editing relies on the Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) pathway, which is inherently less efficient in primary cells due to biological constraints. The competing Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway dominates, especially in non-dividing cells [7] [8].

Key Factors Limiting HDR in Primary Cells:

- Cell Cycle Dependence: HDR is active primarily in the S and G2 phases, when a sister chromatid template is available. Many primary cells, such as resting immune cells, are quiescent (G0 phase) and favor NHEJ [1] [9].

- Senescence Pathways: Primary cells have active tumor suppressor pathways (p16INK4a/p53). These pathways, which guard against uncontrolled proliferation, can also act as a barrier to the reprogramming and high-fidelity DNA repair needed for efficient knock-in [5].

- Cultural Challenges: Primary cells are more sensitive to stress from transfection and manipulation, leading to lower viability during editing protocols [1].

FAQ: Troubleshooting Low Knock-in Efficiency

How can I enhance HDR efficiency in my primary cell culture?

Improving HDR requires strategies to tilt the cellular repair balance away from NHEJ and towards HDR. The table below summarizes effective approaches.

Strategies to Enhance HDR Knock-in Efficiency:

| Strategy | Method | Example Reagents/Techniques | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Synchronization | Enrich for S/G2 phase cells | Serum starvation, contact inhibition release, CDK1 inhibitors [9] | Can impact cell viability; timing is critical. |

| NHEJ Pathway Inhibition | Temporarily suppress competing repair | Small molecule inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648, Nedisertib) [8] [10] | Can be toxic; use transient treatment (24-48 hours). |

| Optimized Delivery Format | Use Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Electroporation of pre-complexed sgRNA:Cas9 RNP [1] | Reduces cytotoxicity and off-target effects compared to plasmid DNA. |

| HDR Donor Design | Optimize homology arms and format | ssODN (30-60 nt arms), dsDNA with ~800 bp arms; disrupt PAM in donor template [8] [9] | Prevents re-cleavage of edited alleles. |

| Modulating Epigenetic State | Alter chromatin accessibility | MEK inhibitors [6] | Effect is cell line-specific. |

My knock-in efficiency is still low after trying standard protocols. What else can I optimize?

Beyond general HDR enhancement, specific parameters in your experimental design are critical for success.

- gRNA and Cut Site Selection: Position the CRISPR cut site as close as possible to the desired insertion point. The highest HDR efficiency is achieved when the insertion is within 10 base pairs of the double-strand break [9]. Some sgRNAs, known as "MMEJ-biased," can lead to higher knock-in efficiency even at the same target locus [10].

- CRISPR Component Delivery: For primary cells, especially sensitive types like T cells, delivery of CRISPR components as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex is highly recommended. The RNP format is less toxic, has a short cellular half-life reducing off-target effects, and can achieve higher editing efficiencies than plasmid or mRNA delivery [1].

- Cell Health and Viability: Ensure your primary cells are healthy and proliferating optimally at the time of editing. Poor cell health is a major contributor to experimental failure. Use low passage numbers and avoid over-confluency [1] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Knock-in Experiments

This table details key reagents and their functions for conducting knock-in experiments in primary cells.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Induces a precise double-strand break at the target genomic locus. | The preferred format for primary cells; complex guide RNA and Cas9 protein before electroporation [1]. |

| HDR Donor Template | Provides the DNA template for the desired insertion via homologous recombination. | Can be single-stranded (ssODN) for small edits or double-stranded (dsDNA) for larger inserts. Must include homology arms [8] [9]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitor (e.g., AZD7648) | A small molecule that inhibits DNA-PKcs, a key kinase in the NHEJ pathway. | Shifts repair towards HDR/MMEJ. Use transiently during editing to reduce toxicity [10]. |

| Electroporation System | Enables efficient delivery of RNP complexes and donor DNA into primary cells. | Systems like the 4D-Nucleofector are optimized for challenging primary cell types [1]. |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Enhances cell viability and recovery post-editing. | Antioxidants like Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) have been shown to accelerate reprogramming and may improve recovery [6]. |

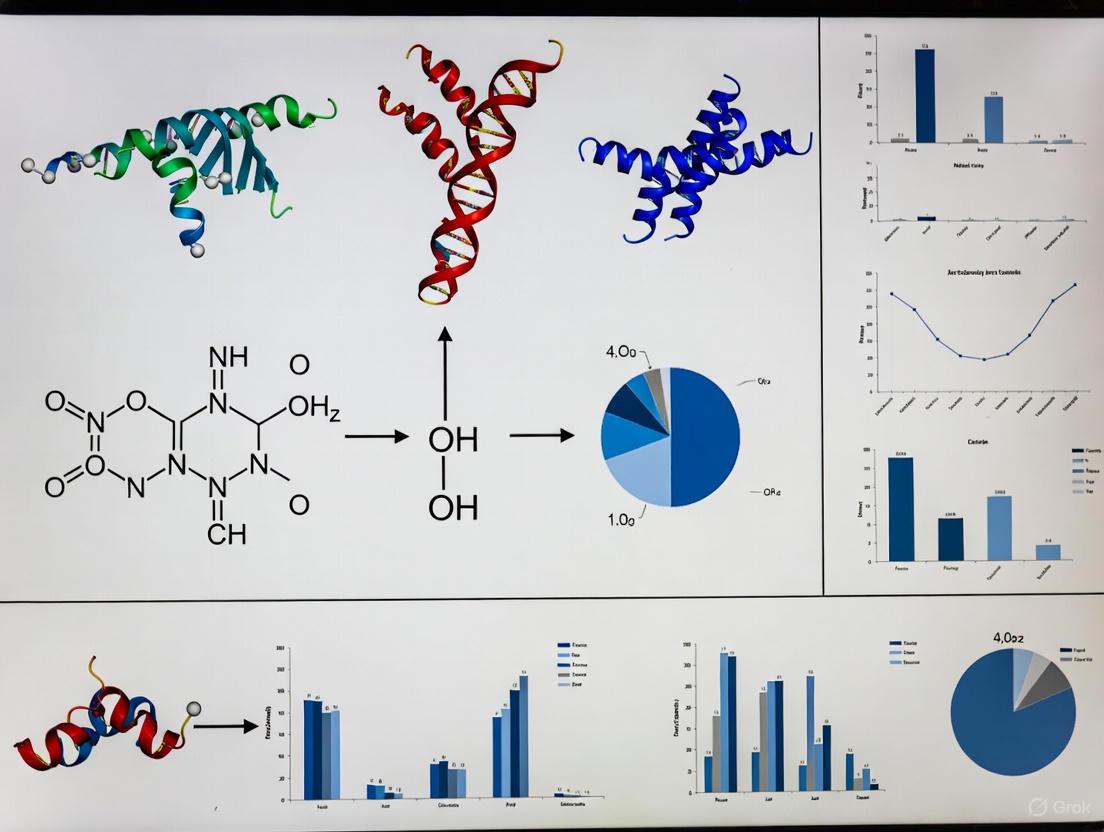

Understanding DNA Repair Pathway Competition

The following diagram illustrates the critical cellular decision point after a CRISPR-induced double-strand break (DSB), which determines the success of your knock-in experiment.

Core Challenge: The Cellular Repair Pathway Bottleneck

Why is achieving knock-in via Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) so inefficient in primary cells?

The fundamental hurdle is a cellular competition between two DNA repair pathways after a CRISPR-Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB). The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these competing pathways.

Table 1: Key DNA Repair Pathways in Primary Cells

| Repair Pathway | Full Name | Mechanism | Efficiency in Primary Cells | Primary Cell Cycle Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | Non-Homologous End Joining | Error-prone; ligates broken ends, often causing small insertions or deletions (indels). | High; active throughout the cell cycle and favored in quiescent cells. [11] [7] [12] | All phases [12] |

| HDR | Homology-Directed Repair | Precise; uses a donor DNA template to copy in a specific sequence. | Low; restricted to late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. [13] [1] [12] | S/G2 phases only [12] |

The following diagram illustrates how this pathway competition unfolds after a CRISPR-induced break, leading to the low HDR efficiency typical in primary cells.

Strategic Solutions: Tipping the Balance Toward HDR

What strategies can I use to enhance HDR knock-in efficiency in my primary cell experiments?

Given the natural biological bias, successful knock-in requires strategies to suppress NHEJ and/or promote HDR. The following table compares key strategic approaches.

Table 2: Strategies to Enhance HDR Knock-In Efficiency

| Strategy Category | Specific Approach | Mechanism of Action | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modulate Repair Pathways | Inhibit key NHEJ proteins (e.g., DNA-PKcs). [14] [12] | Shifts repair balance away from NHEJ, favoring HDR. | Risk: May exacerbate large-scale genomic aberrations (e.g., chromosomal translocations). [14] |

| Use HDR-enhancing proteins (e.g., Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein). [15] | Specifically boosts the HDR pathway. | Benefit: Early data shows up to 2-fold HDR increase in challenging cells (iPSCs, HSPCs) without increased off-target effects. [15] | |

| Cell Cycle Manipulation | Synchronize cells in S/G2 phase. [12] | Creates a temporal window where HDR machinery is active. | Technically challenging, especially for sensitive primary cells. HDR is confined to these phases. [1] [12] |

| Optimize Delivery & Template | Use Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. [1] | Shortens editor exposure, reduces toxicity, and improves editing efficiency in primary T cells. | Superior to plasmid DNA for hard-to-transfect primary cells. [1] |

| Optimize HDR template design (single vs. double-stranded, homology arm length). [11] | Increases likelihood of template being used for repair. | For short inserts, single-stranded templates with 30-60 nt homology arms are recommended. [11] |

The workflow for a optimized knock-in experiment, incorporating these strategies, is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for HDR Knock-In

What key reagents are essential for a successful knock-in experiment in primary cells?

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Knock-In in Primary Cells

| Reagent | Function | Key Features & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates a precise double-strand break in the target DNA. | High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects. Delivering as a protein in an RNP complex is most effective for primary cells. [7] [1] |

| Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 nuclease to the specific genomic target site. | Chemically modified sgRNAs (e.g., with 2'-O-methyl analogs) increase stability and editing efficiency in primary cells. [1] |

| HDR Donor Template | Provides the homologous DNA sequence for precise integration. | Can be single-stranded (ssODN) or double-stranded (dsDNA). Design with optimized homology arm lengths (e.g., 30-60 nt for ssODN). [11] |

| HDR Enhancer | A small molecule or protein that biases repair toward HDR. | Examples include IDT's Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein or HDAC inhibitors like Tacedinaline. [15] [16] |

| Cell Culture Media | Supports the health and proliferation of sensitive primary cells. | Must be optimized for the specific primary cell type to maintain viability during and after editing. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My primary T cell viability is low after electroporation. What can I do? Low viability is a common challenge. Switching from plasmid-based delivery to pre-assembled Cas9 RNP complexes can significantly reduce toxicity. RNPs have a short half-life, act quickly, and are less toxic than prolonged expression from plasmids, which helps maintain primary cell health. [1]

Q2: I confirmed the knock-in via PCR, but my protein of interest is not expressed. What could be wrong? This could be due to large, unintended structural variations (SVs) at the target site. Traditional short-read sequencing can miss kilobase- or even megabase-scale deletions that remove your knock-in or critical regulatory elements. Employ specialized assays like CAST-Seq or LAM-HTGTS to rule out these major aberrations. [14]

Q3: Are there any safety concerns with using NHEJ inhibitors to boost HDR? Yes. Inhibiting key NHEJ factors like DNA-PKcs, while effective at boosting HDR rates, has been linked to a significant increase in large-scale, genotoxic structural variations, including chromosomal translocations. [14] It is crucial to carefully assess the balance between efficiency and safety for your specific application, especially for therapeutic development.

Q4: Why should I avoid using plasmid DNA for delivery into primary cells? Plasmid DNA is less efficient and more toxic in many primary cell types, such as T cells. Furthermore, the persistent expression of Cas9 from a plasmid increases the window for off-target editing and re-cutting of the successfully edited locus, which can disrupt your precise knock-in. [1]

FAQs: Understanding the Quiescence-HDR Relationship

Why is Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) inefficient in quiescent primary cells?

HDR is a DNA repair pathway that is actively restricted to the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle. This is because it relies on the sister chromatid, which is only present after DNA replication, as a natural template for repair [12]. Quiescent cells, by definition, are in a non-cycling state (often considered G0) and do not undergo DNA replication. Consequently, they lack this essential template and the molecular machinery that is upregulated during S/G2 phases, making HDR inherently inefficient [17] [12].

What are the primary DNA repair pathways active in quiescent cells?

In quiescent cells, double-strand breaks (DSBs) are predominantly repaired by the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway. NHEJ is active throughout all cell cycle phases and functions without a homologous template by directly ligating broken DNA ends [11] [12]. While this allows for continuous DNA repair, it is an error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. Additionally, alternative pathways like Microhomology-Mediated End Joining (MMEJ) can also contribute to DSB repair in these cells [10].

How does the cellular environment in quiescent cells suppress the HDR pathway?

The suppression of HDR in quiescent cells is a multi-faceted process. Key NHEJ factors, such as the Ku70-Ku80 heterodimer and 53BP1, are constitutively expressed and act as the first responders to DSBs. They bind to broken DNA ends and protect them from resection, which is the critical initial step required for initiating HDR [12]. Furthermore, the expression of many genes essential for HDR (e.g., those involved in homologous recombination) is cell cycle-regulated and is low or absent in quiescent cells [18].

Troubleshooting Guides: Enhancing HDR in Quiescent and Primary Cells

Strategy 1: Modulating DNA Repair Pathway Balance

A primary method to enhance HDR is to shift the balance of DNA repair away from NHEJ and toward HDR by using small-molecule inhibitors.

Table 1: Small-Molecule Inhibitors for Enhancing HDR Efficiency

| Inhibitor Name | Target | Mechanism of Action | Effect on HDR |

|---|---|---|---|

| AZD7648 [10] | DNA-PKcs (NHEJ) | Inhibits a key kinase in the canonical NHEJ pathway. | Shifts DSB repair towards MMEJ/HDR, can be combined with other strategies for a universal knock-in approach. |

| M3814 [17] | DNA-PKcs (NHEJ) | Potent and selective inhibitor of DNA-PKcs, suppressing NHEJ. | Boosts HDR efficiency; cited in patent applications for HDR-boosting modules. |

| SCR7 [17] | DNA Ligase IV (NHEJ) | Targets the final ligation enzyme in the NHEJ pathway. | Enhances gene editing directed by CRISPR-Cas9 and ssODN in human cancer cells. |

Experimental Protocol: Inhibitor Treatment

- Reconstitution: Prepare stock solutions of inhibitors according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Transfection & Treatment: Introduce the CRISPR-Cas9 components (e.g., Cas9 RNP) and HDR donor template into your primary cells via your preferred method (e.g., electroporation).

- Timing: Add the chosen NHEJ inhibitor to the cell culture medium at the time of or shortly after transfection.

- Duration: Incubate the cells with the inhibitor for a defined period, typically 12-48 hours, post-transfection. Optimization of the duration and concentration is critical to balance HDR enhancement with cytotoxicity.

Strategy 2: Optimizing HDR Donor Template Design

The design and delivery of the donor template are critical for successful HDR. Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors are often favored in primary cells.

Table 2: Optimized Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Donor Design

| Design Parameter | Recommendation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Template Structure | Single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) | Lower cytotoxicity and higher specificity/ efficiency in precise editing compared to dsDNA donors [17]. |

| Total Length | ~120 nucleotides | Longer sequences may introduce synthesis errors and form secondary structures that reduce efficiency [17]. |

| Homology Arm Length | At least 40 bases (for ssODNs) | Required to achieve robust HDR [17]. For longer dsDNA donors, 200-300 nt arms are recommended [11]. |

| Chemical Modifications | 5'-Phosphate, 3'-Phosphorothioate bonds | These modifications protect the donor from exonuclease degradation and significantly improve HDR potency and efficacy [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: ssODN Donor Design for a Point Mutation

- Identify Target Site: Select the genomic locus and the specific nucleotide(s) to be changed.

- Design Homology Arms: Flank the desired edit with 5' and 3' homology arms, each ≥40 nucleotides in length, perfectly matching the genomic sequence.

- Synthesize ssODN: Order the ssODN with the recommended chemical modifications to enhance stability.

- Co-deliver: Co-electroporate the ssODN donor together with the pre-assembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into the primary cells.

Strategy 3: Forcing Cell Cycle Entry and Controlling Timing

Since HDR is restricted to S/G2, one strategy is to transiently induce proliferation in quiescent primary cells or synchronize transfected cells in HDR-permissive phases.

Experimental Protocol: Cell Cycle Synchronization

- Approach: Use compounds like thymidine or nocodazole to synchronize cells at the G1/S boundary or in M phase, respectively [18].

- Procedure: Synchronize the cells, then release them into the cell cycle and perform the CRISPR-Cas9 transfection at the time when the highest proportion of cells is expected to be traversing S phase. This method is generally more feasible for cultured cell lines than for sensitive primary cells.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the core molecular competition between the NHEJ and HDR pathways at a Cas9-induced double-strand break (DSB), and how cellular quiescence biases this competition.

Diagram: Molecular Pathway Competition Between NHEJ and HDR. This figure illustrates how a double-strand break is repaired in a quiescent cell. The NHEJ pathway, active in all cell cycle phases, is favored and rapidly engaged, leading to imperfect repair and gene disruption. The HDR pathway, which requires a homologous template and specific proteins expressed during S/G2, is suppressed. Using NHEJ inhibitors can shift this balance, promoting precise HDR-mediated knock-in.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enhancing HDR in Challenging Cells

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., M3814, AZD7648) | Small molecules that suppress the error-prone NHEJ pathway, freeing up DSBs for repair via HDR [17] [10]. | Critical for shifting repair balance; require toxicity testing in primary cells. |

| Chemically Modified ssODNs | Single-stranded DNA donors with phosphorothioate bonds that resist nuclease degradation, improving donor stability and HDR efficiency [17]. | The preferred donor type for introducing point mutations and short tags in primary cells. |

| HDR-Boosting Fusion Proteins (e.g., CtIP, RAD51 fusions) | Proteins engineered to fuse with Cas9, which recruit HDR factors directly to the cut site to promote homologous recombination [17]. | Can be encoded in plasmids or expressed as part of the RNP complex. |

| Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) | Pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and guide RNA. | Enables rapid editing with reduced off-target effects; ideal for primary cells where extended Cas9 expression is undesirable. |

| Cell Cycle Reporter Dyes (e.g., Fucci) | Fluorescent dyes that allow for tracking and sorting of cells based on their cell cycle stage (G1, S, G2/M) [19]. | Useful for isolating the small fraction of transfected cells that are in S/G2 phase for analysis or expansion. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the health of my primary cell culture directly impact knock-in efficiency? Healthy, actively dividing cells are fundamental for high knock-in efficiency. The homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, required for incorporating knock-in sequences, is primarily active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [9] [1]. Quiescent or slow-growing cells favor the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which leads to random insertions and deletions rather than precise knock-ins [8] [1]. Furthermore, stressed, contaminated, or sub-optimally cultured cells experience DNA damage and repair mechanisms that can compete with or hinder the desired HDR process.

What are the most critical factors to optimize in my culture conditions to improve HDR? Beyond standard culture practices, key factors to optimize for HDR include:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: While challenging, synchronizing cells to S/G2 phase can enhance HDR [9].

- Culture Media and Growth Factors: Using optimized media and appropriate concentrations of growth factors is crucial for maintaining robust cell health and proliferation, thereby supporting HDR [20].

- Cell Density: Maintaining cells in an active growth phase without allowing them to become over-confluent is important, as nutrient depletion and contact inhibition can drive cells into quiescence [9].

My cells are healthy, but my knock-in efficiency is still low. What else should I check? If cell health is confirmed, investigate these areas:

- CRISPR Delivery Format: Using pre-assembled Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes is highly recommended for primary cells, as it leads to higher editing efficiency and lower toxicity compared to plasmid or mRNA delivery [1].

- HDR Donor Design: Ensure your donor template has homology arms of sufficient length and is designed to disrupt the PAM site or gRNA binding sequence to prevent re-cleavage after successful HDR [8] [9].

- HDR Enhancement Reagents: Consider using small molecule inhibitors of the NHEJ pathway (e.g., Nedisertib) or novel reagents like ubiquitin variant peptides that block 53BP1 recruitment, which have been shown to increase HDR rates 2 to 4-fold in primary T cells [8] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Cell Viability Post-Transfection

| Potential Cause | Investigation & Verification | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Electroporation/Nucleofection Toxicity | Check viability of mock-transfected control (cells subjected to the transfection protocol without CRISPR components) [21]. | Optimize electroporation parameters (voltage, pulse length). Switch to a gentler delivery method, such as the RNP format, which is less toxic than plasmid DNA [1]. |

| Cellular Stress from Culture Conditions | Check for signs of contamination (e.g., mycoplasma, which can alter cell metabolism without causing cloudiness) [22]. Ensure cells are not over-confluent. | Use antibiotics and antimycotics prophylactically. Strictly follow aseptic techniques. Use high-quality, fresh media and supplements. Passage cells at appropriate densities [22]. |

Problem: High Indel Percentage but Low Knock-In Rate

This problem occurs when cells are being edited, but the DNA breaks are being repaired predominantly via NHEJ instead of HDR.

| Potential Cause | Investigation & Verification | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient HDR Pathway | Use a positive editing control (validated gRNA with known high HDR efficiency) to establish a baseline [21]. | Use small molecule inhibitors (e.g., Reomidepsin) to suppress NHEJ and favor HDR [8]. Transfert cells in their exponential growth phase [9] [1]. |

| Suboptimal HDR Donor Template | Verify the design of your donor DNA, particularly homology arm length [8] [9]. | For point mutations or short tags (<200 bp), use single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with 30-60 nt homology arms. For larger inserts, use double-stranded donors with 500-1000 bp homology arms [8] [9]. |

| Re-cleavage of Integrated Donor | Check if your donor template contains a silent mutation in the PAM sequence or gRNA binding site [9]. | Re-design the donor template to mutate the PAM site, preventing the Cas9 nuclease from re-cutting the DNA after successful HDR [9]. |

Key Reagents and Solutions for Enhancing Knock-In

The following table summarizes critical reagents discussed for improving knock-in outcomes in primary cells.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., Nedisertib) | Suppresses the error-prone NHEJ repair pathway, tilting the balance towards HDR-mediated repair [8]. | Use at optimized concentrations and timing to avoid excessive toxicity; typically added transiently during/after editing. |

| HDR Enhancers (Ubiquitin Variant Peptides) | Blocks 53BP1 recruitment to double-strand breaks, a key factor that suppresses HDR, thereby increasing knock-in rates [20]. | A novel approach shown to boost HDR 2 to 4-fold in primary T cells without observed toxicity [20]. |

| Cas9 RNP Complex | Pre-complexed Cas9 protein and guide RNA. Offers rapid activity, high efficiency, and reduced toxicity in primary cells compared to nucleic acid delivery [1]. | The gold standard for editing primary cells; short half-life limits off-target effects. |

| ssODN / dsDNA HDR Donor | Provides the template for precise incorporation of the desired sequence via the HDR pathway [8] [9]. | Format and arm length are critical. Use ssODNs for small edits and dsDNA plasmids/viral vectors for large inserts [9]. |

| Cell Synchronization Agents | Arrests cells in S/G2 phase of the cell cycle, where the HDR machinery is most active [9]. | Can be cytotoxic if prolonged; requires careful optimization of timing and concentration. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing HDR in Primary T Cells

This protocol outlines a strategy to maximize knock-in efficiency in primary human T cells by combining optimized culture practices with CRISPR best practices.

1. Pre-work: Cell Preparation and Health

- Activation: Activate isolated primary T cells using CD3/CD28 beads or similar agents in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with IL-2 (e.g., 100 U/mL). Proper activation is required for both proliferation and efficient gene editing [20].

- Culture: Maintain cells at a density that supports active growth (e.g., 0.5-1.5 x 10^6 cells/mL) and do not allow them to become over-confluent. Use pre-warmed, fresh media for feeding [9].

2. CRISPR Component Preparation

- Format: Use Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

- Complex chemically synthesized, modified sgRNA with high-quality Cas9 protein at a molar ratio of 1:1 to 1:2 (Cas9:gRNA). Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes before transfection [1].

- HDR Donor: For a CAR transgene, a double-stranded DNA template (linearized plasmid or PCR product) with 500-800 bp homology arms is typical. Include mutations in the PAM site within the donor sequence to prevent re-cleavage [9].

3. Transfection and HDR Enhancement

- Method: Use electroporation/nucleofection optimized for primary T cells.

- HDR Boost: Co-deliver the RNP complex and HDR donor template with an HDR-enhancing reagent, such as an NHEJ inhibitor or a ubiquitin variant peptide [8] [20].

4. Post-Transfection Recovery

- Culture: Immediately after transfection, transfer cells to pre-warmed, complete culture medium.

- Remove Inhibitors: If using small molecule NHEJ inhibitors, remove them within 24-48 hours to restore normal DNA repair functions and maintain cell viability [9].

5. Validation and Analysis

- Genotyping: After 3-5 days, extract genomic DNA and use PCR to amplify the target locus. Analyze the product by Sanger sequencing and use a tool like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) to calculate the knock-in efficiency [23].

- Functional Assays: Perform flow cytometry for surface markers or CAR expression, and/or conduct functional assays to confirm the protein's activity [23].

Essential Experimental Controls

To accurately interpret your knock-in experiments, especially when troubleshooting, include the following controls [21]:

- Mock Transfection Control: Cells subjected to the transfection protocol without any CRISPR components. Controls for effects of the transfection process itself.

- Targeting Negative Control: Cells transfected with Cas9 protein only (no gRNA) or with a non-targeting "scrambled" gRNA. Controls for non-specific effects of Cas9 or gRNA presence.

- Positive Editing Control: Cells transfected with an RNP targeting a well-characterized, easy-to-edit locus (e.g., AAVS1). Verifies that your transfection and editing workflow is functioning optimally.

Visual Workflow: From Double-Strand Break to Successful Knock-In

The diagram below illustrates the critical cellular decision point after a CRISPR-induced double-strand break and the strategies you can use to steer the outcome toward a successful knock-in.

Strategic Interventions to Steer DNA Repair Toward Precise Knock-In

Advanced Delivery Systems and Template Design for Enhanced Knock-In

For researchers troubleshooting low knock-in efficiency in primary cell cultures, the delivery method of CRISPR-Cas9 components is often a critical, overlooked factor. While viral vectors and chemical transfection have been widely used, electroporation of Cas9 Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) has emerged as a superior strategy for primary cells. This approach involves delivering pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and guide RNA directly into cells, offering high editing efficiency with transient activity that minimizes off-target effects and cellular toxicity [24] [25].

This guide addresses common experimental challenges and provides proven solutions to enhance your knock-in efficiency in primary cell research.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is my gene knock-in efficiency low in primary cells despite high transfection rates?

The Challenge: Primary cells often favor error-prone DNA repair pathways (NHEJ) over precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), which is necessary for knock-ins [11].

Solutions:

- Modify DNA repair pathways: Quiescent primary B cells strongly favor NHEJ over HDR [11]. Consider using small molecule inhibitors like AZD7648 to shift repair toward HDR-compatible pathways. In mouse embryo studies, combining AZD7648 with Polq knockdown significantly enhanced knock-in efficiency [10].

- Optimize HDR template design: For short single-stranded oligos, use 30-60 nt homology arms; for longer donors, 200-300 nt lengths are recommended [11]. The positioning of edits matters: the targeting strand is preferred for PAM-proximal edits, while the non-targeting strand benefits PAM-distal edits [11].

- Implement SMART template design: The "Silently Mutate And Repair Template" strategy can dramatically improve knock-in efficiency when the PAM site is far from your desired modification site by preventing the gap sequence from acting as an unintended homology arm [26].

FAQ 2: How can I improve cell viability after electroporation while maintaining high editing efficiency?

The Challenge: Electroporation parameters that maximize editing often compromise cell viability, especially in sensitive primary cells.

Solutions:

- Optimize electroporation parameters: Different systems require different optimization approaches. The table below demonstrates how parameter adjustments affect outcomes in various cell types:

Table 1: Electroporation Optimization Across Cell Types and Systems

| Cell Type | Electroporation System | Optimal Parameters | Editing Efficiency | Cell Viability | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Human Hepatocytes | Not Specified | Not Specified | 52.4% indels | >65% | [24] |

| Primary Mouse Hepatocytes | MaxCyte GTx | Hepatocyte-3 program | ~100% indels | 89.9% | [27] |

| Bovine Zygotes | Neon | High voltage, multiple pulses | 65.2% edited blastocysts | 50% cleavage rate | [28] |

| HSPCs, T cells | Clinical-grade systems | Pre-optimized protocols | High (Clinical use) | Maintained engraftment | [29] [27] |

- Use commercial electroporation enhancers: NEPA21 electroporation with a commercial electroporation enhancer reagent produced up to 47.6% transfected bovine embryos, though viability remained a challenge [28].

- Validate with positive controls: Always use validated positive control gRNAs (e.g., targeting human AAVS1, CDK4, HPRT1, or mouse Rosa26) to distinguish between delivery issues and guide RNA problems [30].

FAQ 3: What RNP format and ratio should I use for optimal results?

The Challenge: Suboptimal Cas9:gRNA ratios or component formats can significantly reduce editing efficiency.

Solutions:

- Use pre-complexed RNPs: The pre-formed RNP format does not require transcription or translation, leading to faster editing and reduced off-target effects [25].

- Maintain proper molar ratios: For gene editing, highest editing efficiency is typically achieved with a 1:1 molar ratio of gRNA to Cas9 protein [30]. In some difficult-to-transfect cells like iPSCs and THP1, researchers have successfully used up to 2 μg TrueCut Cas9 Protein v2 and 400 ng gRNA per well in a 24-well format [30].

- Ensure proper nuclear delivery: Since pre-formed RNPs require nuclear access for editing, use electroporation methods optimized for nuclear delivery (nucleofection), especially in non-dividing primary cells [25].

Advanced Strategies: Enhancing Knock-in Efficiency

DNA Repair Pathway Manipulation

Table 2: Strategies to Modulate DNA Repair for Enhanced Knock-in

| Approach | Mechanism | Effect on Knock-in | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMEJ Enhancement | Shifts repair toward microhomology-mediated pathways | Positive correlation with dsDNA donor integration | AZD7648 treatment [10] |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Reduces competing error-prone repair | Variable effects; context-dependent | DNA-PKcs inhibitors [10] |

| Polθ Knockdown | Blocks key MMEJ enzyme | Enhances HDR for MMEJ-biased sgRNAs | CasRx-mediated Polq silencing [10] |

| Combined Approach | Simultaneously modulates multiple pathways | Dramatically improves efficiency | ChemiCATI (AZD7648 + Polq KD) [10] |

Template Design Innovation

The SMART (Silently Mutate And Repair Template) approach represents a significant advance in HDR template design. By introducing silent mutations in the gap sequence between the cut and insertion sites, SMART prevents this region from acting as an unintended homology arm, thereby increasing correct integration efficiency, especially when the PAM site is distant from your desired modification site [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for RNP Electroporation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | CRISPR nuclease for DNA cleavage | S. pyogenes Cas9 from IDT or Aldevron [29] |

| Synthetic gRNA | Target-specific guide RNA | Chemically modified sgRNAs from TriLink or Synthego [24] |

| Electroporation System | Physical delivery method | Neon, NEPA21, or MaxCyte GTx systems [30] [28] [27] |

| Electroporation Buffer | Cell-friendly conductive solution | MaxCyte Electroporation Buffer [27] |

| HDR Template | Donor DNA for precise editing | ssDNA or dsDNA with optimized homology arms [11] |

| Cell Culture Media | Maintain cell viability post-electroporation | Cell-specific optimized formulations [24] |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol

Standardized RNP Electroporation Protocol for Primary Cells

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Cell Preparation: Isolate primary cells using established protocols. For hepatocytes, use a three-step perfusion procedure with Liberase digestion [24]. Ensure high initial viability (>70% for hepatocytes) [27].

RNP Complex Assembly:

Electroporation Setup:

- Use the appropriate electroporation system for your cell type.

- For the MaxCyte GTx system with primary hepatocytes, use the Hepatocyte-3 program [27].

- Mix cells with assembled RNPs in electroporation buffer immediately before pulsing.

Post-Electroporation Recovery:

DNA Repair Pathway Dynamics

Understanding the competitive relationship between DNA repair pathways is essential for troubleshooting knock-in efficiency issues. The following diagram illustrates how DSB repair pathway balance affects knock-in outcomes:

Key Insights:

- Primary cells naturally favor NHEJ,

- MMEJ-biased repair shows stronger correlation with successful knock-in than NHEJ-biased repair [10].

- Strategic inhibition of competing pathways (e.g., using AZD7648 or Polq knockdown) can significantly shift the balance toward HDR [10].

RNP electroporation represents a robust, efficient, and clinically relevant method for genome editing in primary cells. By understanding the principles outlined in this guide—particularly the optimization of electroporation parameters, strategic manipulation of DNA repair pathways, and implementation of advanced template designs—researchers can systematically troubleshoot and overcome the common challenge of low knock-in efficiency in their primary cell culture experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary advantages of using single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) templates over double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) for HDR?

Using single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) as a Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) template offers several key advantages over double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), especially when working with sensitive primary cells like T cells. The main benefits include:

- Reduced Cellular Toxicity: ssDNA demonstrates significantly less cytotoxicity compared to dsDNA. This allows researchers to use higher concentrations of template DNA to boost knock-in efficiency without severely impacting cell viability and final yield of edited cells [31] [32].

- Lower Off-Target Integration: ssDNA templates are associated with a substantial reduction in off-target, random integration events. One case study showed that off-target integration with ssDNA was reduced to nearly undetectable levels, similar to a negative control, whereas dsDNA induced significant off-target integration [31].

- High Editing Efficiency: ssDNA is a preferred substrate for the HDR machinery. With optimized designs, ssDNA can achieve knock-in efficiencies of over 80-90% in primary human cells [32].

What are the optimal homology arm lengths for different types of HDR templates?

The optimal length for homology arms is highly dependent on the type of DNA template used, largely due to the differences in size and structure of the molecules [33].

- For ssDNA templates (ssODNs): These are typically used for shorter insertions (like point mutations or small tags) and work efficiently with relatively short homology arms. A length of 30–60 nucleotides (nt) per arm is often sufficient for good HDR efficiency [33].

- For double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates: These are used for larger insertions (e.g., 1-2 kb). They generally require much longer homology arms to achieve efficient recombination. For dsDNA HDR donor blocks, recommended arm lengths are typically in the range of 200–300 base pairs (bp) [33].

How can I further improve knock-in efficiency when using ssDNA templates?

A powerful strategy to enhance the performance of ssDNA templates is the use of ssCTS (single-stranded DNA with Cas9 Target Sequences). This hybrid design involves a predominantly single-stranded template with short, double-stranded regions at the ends that contain a Cas9 (or Cas12a) target sequence [32] [34].

- Mechanism: The Cas9 nuclease binds to these CTS sites on the donor template, which facilitates the co-delivery of the RNP and the HDR template to the nucleus. This physical tethering increases the local concentration of the repair template at the site of the double-strand break, thereby boosting HDR efficiency [32].

- Efficiency: Studies have shown that ssCTS templates can boost knock-in efficiency and yield by an average of two- to threefold compared to standard dsDNA templates with CTS. This method has achieved HDR efficiencies of >80-90% in primary human T cells, B cells, and NK cells [32]. For Cas12a-based editing, ssCTS designs have achieved up to 90% knock-in at certain loci [34].

Table 1: Direct Comparison of ssDNA vs. dsDNA HDR Templates

A summary of key performance metrics helps in selecting the appropriate template type [31] [32].

| Feature | Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) | Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Cellular Toxicity | Lower | Higher |

| Off-Target Integration | Significantly reduced | Higher |

| Knock-in Efficiency | High (can exceed 90% with ssCTS) | Moderate to High |

| Typical Insert Size | Shorter inserts (ssODN); several kb with long ssDNA [32] | Larger inserts (1-2 kb is common) [33] |

| Optimal Homology Arm Length | 30-60 nt (for ssODNs) [33] | 200-300 bp [33] |

Table 2: Optimized ssCTS Design Parameters

When constructing an ssCTS template, specific sequence requirements must be met for maximal enhancement [32].

| ssCTS Component | Requirement | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| CTS (Cas9 Target Sequence) | Must be a matching sequence recognized by the cognate Cas9-gRNA complex. | Enables specific binding of the RNP to the template. |

| PAM Sequence | Required (NGG for SpCas9). | Essential for Cas9 recognition and binding to the CTS. |

| Homology Arm Downstream of CTS | A stretch of nucleotides within the homology arm directly downstream of the CTS site must be double-stranded. | Critical for enhancing knock-in efficiency. |

| 5' Buffer Region | Not required; can be omitted. | Inclusion may reduce knock-in efficiency. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Template Toxicity and Knock-in Efficiency in Primary T Cells

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing ssDNA and dsDNA templates [31].

- Template Design: Design dsDNA and ssDNA HDR templates with identical homology arms and a GFP reporter construct to target a specific locus (e.g., a house-keeping gene).

- Cell Preparation: Isolate primary human T cells from healthy donors and activate them.

- Electroporation: Co-electroporate the cells with pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes and varying amounts (e.g., 0.5 µg to 4 µg) of either ssDNA or dsDNA HDR templates.

- Viability Measurement: Two days post-electroporation, measure cell viability using a method like flow cytometry with a live/dead stain. Expect to see higher viable cell counts in the ssDNA groups across most template concentrations [31].

- Efficiency Analysis: Four days post-electroporation, measure the percentage of GFP-positive cells via flow cytometry to determine the knock-in efficiency. The efficiency should increase with the amount of template, with ssDNA potentially showing higher efficiency at the highest concentrations [31].

Protocol 2: Implementing ssCTS for High-Efficiency Knock-in

This methodology is based on the hybrid ssCTS template design [32].

- Template Production: Synthesize a long single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) containing your transgene and homology arms.

- CTS Addition: Create short, double-stranded CTS regions on both the 5' and 3' ends of the ssDNA by annealing complementary oligonucleotides. These oligos must cover the gRNA target sequence, the PAM, and a short stretch of the homology arm downstream of the CTS.

- Electroporation: Co-electroporate primary T cells with the Cas9 RNP and the purified ssCTS template.

- HDR Enhancement (Optional): To further increase HDR rates, include small-molecule HDR enhancers in the culture media post-electroporation. These can provide an additional two- to threefold increase in efficiency [32].

- Validation: Confirm knock-in efficiency and sequence fidelity using flow cytometry (for reporter genes) and long-read sequencing to verify precise integration and reduced partial integration events [34].

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Toolkit

Diagram: Workflow for Optimized HDR Template Selection and Testing

The following diagram outlines a logical decision path for selecting and testing HDR templates to troubleshoot low knock-in efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and reagents for implementing the optimized HDR protocols described in this guide.

| Reagent / Material | Function in HDR Experiment |

|---|---|

| Long ssDNA HDR Templates | The repair template for precise gene insertion; offers low toxicity and high efficiency. Commercially available from providers like GenScript [31]. |

| Cas9 Protein (WT or High-Fidelity) | Creates a double-strand break at the target genomic locus. High-fidelity variants reduce off-target effects [7]. |

| Chemically Synthesized sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific DNA target sequence [7]. |

| HDR-Enhancing Small Molecules | Small molecule compounds that inhibit the NHEJ pathway or promote the HDR pathway to increase knock-in efficiency [32]. |

| Electroporation System | A device for delivering RNP complexes and HDR templates into primary cells (e.g., T cells) with high efficiency [32]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Constructs | Genes like GFP or cell surface markers like tNGFR enable rapid assessment of knock-in efficiency via flow cytometry [31] [32]. |

For researchers troubleshooting low knock-in efficiency in primary cell cultures, achieving high editing rates remains a significant challenge. Primary cells, particularly immune cells like T cells and hematopoietic stem cells, often reside in a quiescent state that favors error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) over precise homology-directed repair (HDR), the pathway required for knock-ins [8]. Furthermore, these cell types exhibit robust innate immune responses that can degrade unmodified guide RNAs (gRNAs) before they can direct Cas proteins to their genomic targets, dramatically reducing editing efficiency [35]. Chemical modifications to synthetic single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) represent a crucial solution to these challenges by protecting the RNA molecule from degradation and mitigating immune responses, thereby significantly enhancing both stability and performance in clinically relevant cell types [35]. This guide addresses the specific issues researchers face when working with hard-to-transfect primary cells and provides actionable solutions to improve experimental outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why should I use chemically modified sgRNAs instead of plasmid-expressed or in vitro transcribed (IVT) gRNAs for my primary cell experiments? Chemically modified sgRNAs are synthetically produced, allowing precise incorporation of stabilizing chemical groups into the RNA backbone. Unlike plasmid or IVT guides, they are armored against nucleases present in primary cells, which rapidly degrade unmodified RNA. This protection is crucial because primary human cells, such as T cells and CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells, trigger strong immune responses against foreign RNA, leading to cell death and low editing yields. Modified sgRNAs resist degradation, leading to higher Cas9 activity, improved cell viability, and significantly enhanced knock-in efficiency in these challenging but clinically relevant cell types [35].

2. What are the most effective chemical modifications for CRISPR sgRNAs? The most common and effective chemical modifications are 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me) and phosphorothioate (PS) bonds, often used in combination [35].

- 2'-O-Methyl (2'-O-Me): A backbone modification where a methyl group is added to the 2' hydroxyl of the ribose sugar. This is the most common natural RNA modification and protects against nuclease degradation.

- Phosphorothioate (PS): A backbone modification where a non-bridging oxygen atom in the phosphate group is replaced with sulfur. This modification increases resistance to nucleases.

- Combined Modifications (MS): When 2'-O-Me and PS are used together, they provide greater stability than either modification alone, creating a synergistic protective effect.

These modifications are typically added at the terminal nucleotides of both the 5' and 3' ends of the sgRNA molecule, as these regions are particularly vulnerable to exonuclease attack. They are avoided in the "seed region" at the 3' end of the crRNA sequence, as modifications here could impair hybridization to the target DNA [35].

3. Do chemical modifications work with Cas enzymes other than SpCas9? Yes, but the optimal modification strategy depends on the specific nuclease. For example, while SpCas9 tolerates modifications at both the 5' and 3' ends, Cas12a will not tolerate any 5' modifications. High-fidelity variants like hfCas12Max may require slightly different 3' end modifications compared to SpCas9. It is essential to consult the literature or your nuclease supplier for modification patterns optimized for your specific enzyme [35].

4. Can chemically modified sgRNAs reduce off-target effects? Yes, certain chemical modifications can improve editing specificity. For instance, 2′-O-methyl-3′-phosphonoacetate (MP) modifications have been shown to reduce off-target editing while maintaining on-target activity. By stabilizing the sgRNA and ensuring a more precise interaction with the target DNA, these modifications help prevent partial binding to off-target sites with sequence similarity [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Knock-in Efficiency in Primary Cells

Problem: Low HDR Efficiency Due to sgRNA Instability

Symptoms:

- Low rates of precise template integration.

- High cell death post-electroporation/transfection.

- High levels of indels at the target site instead of precise editing.

Solutions:

- Implement Chemically Modified sgRNAs: Use synthetic sgRNAs with 2'-O-Me and PS modifications at the 5' and 3' ends. This is the most critical step for primary cells, as it protects the guide from degradation and improves cell viability by evading immune responses [35].

- Choose the Right HDR Template: For small insertions (e.g., point mutations, FLAG-tags), use single-stranded oligonucleotide donors with 30-60 nt homology arms. For larger insertions (e.g., fluorescent proteins), use double-stranded DNA templates (such as plasmids) with longer homology arms (500+ nt) [8].

- Inhibit the NHEJ Pathway: Use small molecule inhibitors (e.g., nedisertib) to temporarily suppress the NHEJ pathway, thereby favoring HDR. Caution: Some potent DNA-PKcs inhibitors have been linked to increased genomic aberrations, including large deletions and chromosomal translocations. Evaluate the safety profile of such compounds carefully for your application [14].

Problem: High Cell Toxicity and Poor Viability

Symptoms:

- Low post-transfection cell recovery.

- Activation of cell death pathways.

Solutions:

- Use Chemically Modified sgRNAs: Unmodified RNA can trigger the innate immune system, leading to apoptosis. Chemically modified guides are less immunogenic, which directly improves cell health and yield [35].

- Utilize Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery: Deliver the Cas9 protein pre-complexed with the sgRNA as an RNP complex via electroporation. This method is fast, minimizes Cas9 exposure, and is highly effective in primary cells [8].

- Optimize Cell Health: Ensure cells are in optimal condition pre-editing. Using cells at an appropriate passage number and density, and providing proper cytokine support can significantly impact outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Knock-in

Protocol 1: Knock-in in Primary T Cells Using Modified sgRNAs

This protocol is adapted from a case study achieving high-efficiency knockout in resting CD4+ T cells [35].

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Research Reagent | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA (e.g., Synthego's Research sgRNA) | Protects guide from degradation; reduces immune response; increases editing efficiency. |

| Cas9 Nuclease (WT or HiFi) | Creates a double-strand break at the target genomic locus. |

| 4D-Nucleofector (Lonza) | Device for efficient RNP delivery into hard-to-transfect primary cells. |

| HDR Template (ssODN or dsDNA) | Provides the homologous DNA template for the desired precise edit. |

| Small Molecule NHEJ Inhibitor (e.g., nedisertib) | Temporarily suppresses NHEJ to tilt repair balance toward HDR. |

Methodology:

- Complex Formation: Pre-complex high-quality Cas9 protein with chemically modified sgRNA to form the RNP complex. Incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature.

- Cell Preparation: Isolate and activate primary human T cells using CD3/CD28 beads if necessary.

- Electroporation: Combine the RNP complex and HDR template with the cell suspension. Electroporate using a primary cell-optimized program on the 4D-Nucleofector system.

- Post-Transfection Handling: Immediately transfer cells to pre-warmed media. Optionally, add an NHEJ inhibitor to the culture media for 24-48 hours to enhance HDR rates.

- Recovery and Analysis: Allow cells to recover for 48-72 hours before assessing viability and editing efficiency via flow cytometry or next-generation sequencing.

Protocol 2: Evaluating sgRNA Modification Efficacy

Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the key steps for testing and validating the performance of chemically modified sgRNAs against their unmodified counterparts.

Quantitative Data on Modification Benefits

Table 1: Impact of Chemical Modifications on Editing Outcomes in Primary Cells

| Cell Type | Editing Goal | Modification Type | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Human T Cells | Knockout | 2'-O-Me & PS (MS) | Enhanced editing efficiency and cell viability | [35] |

| CD34+ Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells (HSPCs) | Knockout | 2'-O-Me & PS (MS) | Enabled efficient editing in clinically relevant cells | [35] |

| Resting Human CD4+ T Cells | Knockout | Proprietary Modified Research sgRNA | Achieved unprecedented knockout efficiencies and sustained viability | [35] |

Table 2: Survey Data on CRISPR Workflow Difficulty by Cell Type

| Cell Model | Percentage Finding CRISPR "Easy" | Percentage Finding CRISPR "Difficult" |

|---|---|---|

| Immortalized Cell Lines | 60% | 33.3% |

| Primary T Cells | 16.2% | 50% |

Source: Synthego CRISPR Benchmark Report [36]. This data highlights why specialized tools like modified sgRNAs are essential for difficult-to-edit primary cells.

Essential Pathways and Workflows

sgRNA Protection Mechanism

Chemically modified sgRNAs protect against two primary failure modes in primary cells: nuclease degradation and immune recognition. The following diagram visualizes this protective mechanism.

Troubleshooting Low Knock-In Efficiency in Primary Cell Cultures

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is knock-in efficiency generally low in my primary cell cultures? Knock-in efficiency is low primarily because the homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, required for precise knock-in, is not the cell's primary method for repairing double-strand breaks. In most mammalian cells, HDR accounts for less than 10% of DNA repair events, with the more error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway dominating. This ratio can be even less favorable in non-cycling or slowly dividing primary cells [9].

2. How do I improve HDR efficiency in difficult-to-transfect cells like T cells and neurons? Improving HDR requires a multi-faceted strategy. Key approaches include:

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: Favoring HDR by enriching for S-phase cells, as HDR is most active during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [9].

- NHEJ Inhibition: Using small molecule inhibitors (e.g., nedisertib) to suppress the competing NHEJ pathway [8].

- Optimal Template Design: Using single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) with 30-60 nt homology arms for small insertions and double-stranded DNA donors with 200-1000 nt arms for larger inserts [9] [8].

3. My knock-in works in a cell line but fails in my primary hepatocytes. What is the cause? Primary hepatocytes are often quiescent (non-dividing), a state that strongly favors the NHEJ repair pathway over HDR. Furthermore, primary cells can have limited viability and metabolic activity in culture compared to immortalized cell lines, further reducing the likelihood of successful HDR-mediated editing [9] [8].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDR Efficiency | Low HDR rates across all cell types | NHEJ outcompetes HDR; Cells not in optimal cell cycle phase | Use NHEJ inhibitors; Enrich for S/G2 phase cells; Use Cas12a or HR-factor fused Cas9 [9] [8] |

| Cell Type Viability | Poor health/viability post-transfection (Primary Neurons) | Innate fragility; Electroporation/transfection toxicity | Optimize electroporation parameters; Use specialized media (e.g., MACS NeuroBrew-21); Use gentle handling protocols [37] |

| Donor Design | Failed integration or low efficiency | Donor cut site too far from edit; Short homology arms; Re-cleaving of edited locus | Position cut within 10 bp of edit; Use correct homology arm length; Introduce silent PAM-site mutations in donor [9] |

| Culture Conditions | Slow growth & low knock-in efficiency (T Cells) | Quiescent state; Incorrect cytokine support | Use activation stimuli (e.g., CD3/CD28); Add supportive cytokines (e.g., IL-2) [8] |

| Culture Conditions | Incorrect pH affecting cell health | Mismatch between CO₂ levels and medium bicarbonate | Use 5-10% CO₂ for 1.5-3.7 g/L NaHCO₃; Use CO₂-independent medium or HEPES buffer [38] |

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

Table 1: Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Template Design Guidelines

| Insert Size | Donor Template Type | Recommended Homology Arm Length | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small (e.g., point mutations, tags) | Single-stranded Oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) | 30 - 60 nucleotides [8] | Highest efficiency when cut site is <10 bp from insertion [9] |

| Large (e.g., fluorescent proteins) | Double-stranded DNA (plasmid, dsDNA fragment) | 500 - 1000 nucleotides [9] | Can be effective with shorter arms (~200-300 nt) [8]; Prevents re-cleaving by mutating PAM site [9] |

Table 2: Cell Type-Specific HDR Challenges and Enhancements

| Cell Type | Native HDR Efficiency Challenge | Strategies to Enhance HDR |

|---|---|---|

| T Lymphocytes | Quiescent state favors NHEJ [8] | Activate cells prior to editing (e.g., CD3/CD28 beads); Use NHEJ inhibitors [8] |

| Hepatocytes | Low division rate in culture | Optimize seeding density and media for health; Consider Cas enzymes that promote HDR (e.g., Cas12a) [9] |

| Neural Cells (Astrocytes/Neurons) | Post-mitotic or slow-dividing; Delicate viability | Use high-fidelity transfection methods; Cell cycle synchronization is less effective; Prioritize donor design and NHEJ suppression [9] [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Procedures

Protocol 1: Enhancing HDR in Activated Primary T Cells

- Isolate and Activate T Cells: Isolate primary human T cells from whole blood or PBMCs. Activate using anti-CD3/CD28 beads and culture in RPMI medium supplemented with IL-2 (e.g., 100 U/mL) for 48-72 hours [8].

- Prepare RNP Complex: Complex a high-specificity Cas9 protein with synthesized sgRNA to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex.

- Prepare HDR Template: Design a single-stranded or double-stranded HDR donor template with appropriate homology arms and silent PAM-site mutations [9] [8].

- Electroporation: Co-electroporate the RNP complex and HDR template into the activated T cells using a specialized electroporation system.

- Post-Transfection Culture: Immediately after electroporation, add an NHEJ inhibitor (e.g., 5 µM nedisertib) to the culture medium for 24 hours to favor HDR. Remove the inhibitor thereafter to maintain cell viability [8].

- Validation: Allow cells to recover for 72-96 hours before analyzing knock-in efficiency via flow cytometry or sequencing.

Protocol 2: Culturing and Transfection of Primary Human Neural Cells

- Isolation of Primary Human Astrocytes:

- Isolation of Primary Human Neurons:

- Deplete MHC class I-expressing cells and red blood cells from the dissociated neural cell mixture using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) with anti-HLA-ABC and anti-CD235a antibodies [37].

- Culture the negative fraction (neurons) in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 2% MACS NeuroBrew on poly-D-lysine-coated dishes [37].

- Use neurons within 12 days in culture, replacing half the medium every 3-4 days [37].

- Transfection: Use a low-toxicity transfection reagent or a specialized electroporation system designed for sensitive primary cells. Given the low division rate of neurons, HDR efficiency will be inherently low, and NHEJ-based knock-out strategies may be more feasible.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: HDR and NHEJ pathway competition.

Diagram 2: Cell type-specific knock-in workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Knock-In in Primary Cells

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA & Cas9 Protein | Forms RNP complex for targeted DNA cleavage. | Using pre-complexed RNP reduces off-target effects and is efficient for electroporation. |

| HDR Donor Template | Provides homologous template for precise repair. | Type (ssODN vs. dsDNA) and homology arm length are critical and size-dependent [9] [8]. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors | Shifts repair balance from NHEJ to HDR. | Use at optimized concentration; prolonged exposure can be toxic [8]. |

| Cell Activation Reagents | Promotes cycling in quiescent cells (e.g., T cells). | Anti-CD3/CD28 beads for T cells; essential for improving HDR efficiency [8]. |

| Specialized Culture Medium | Maintains health and function of primary cells. | e.g., MACS NeuroBrew for neurons; requires precise CO₂ levels for pH balance [37] [38]. |

| Electroporation System | Delivers CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect cells. | Essential for primary T cells and neurons; parameters must be optimized for each cell type. |

Strategic Manipulation of DNA Repair Pathways and Culture Conditions

FAQs: Understanding the NHEJ-HDR Balance

Why does the NHEJ pathway dominate over HDR in mammalian cells? NHEJ is the predominant and fast DSB repair pathway in mammalian cells because it is active throughout all phases of the cell cycle. In contrast, HDR is restricted to the S and G2 phases when a sister chromatid is available as a repair template. This cell cycle dependency makes HDR inherently less frequent, with studies indicating that NHEJ repair efficiency can approach 90% in many contexts [39] [40].

What are the primary cellular factors that limit HDR efficiency in primary cells? Key limiting factors include the cell cycle phase (HDR only occurs in S/G2), the chromatin conformation at the target site, and the intrinsic expression levels of HDR-related proteins. Additionally, primary cells and post-mitotic cells are particularly challenging for HDR due to their low division rates [40] [7].

Which DNA repair pathway is more error-prone, and why? NHEJ is an error-prone pathway because it directly ligates broken DNA ends without a homologous template, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels). HDR is a high-fidelity repair mechanism that uses a homologous DNA template to accurately restore the sequence at the break site [41] [39].

Troubleshooting Low HDR Efficiency

Problem: Consistently low knock-in efficiency despite successful Cas9 cutting.

Question: My CRISPR-Cas9 system demonstrates good cutting efficiency at the target locus, confirmed by cleavage assays. However, my knock-in rates via HDR remain extremely low (<1%). What are the main strategies to shift this balance toward HDR?

Solution: The competition between the NHEJ and HDR pathways is the core issue. Implement a multi-pronged approach to suppress NHEJ and enhance HDR.

- Inhibit Key NHEJ Pathway Proteins: Transiently inhibit critical proteins in the classical NHEJ pathway. The following table summarizes common reagents and their targets.

Table 1: Chemical Inhibitors of the NHEJ Pathway to Enhance HDR

| Reagent | Target | Mechanism | Reported HDR Increase | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCR7 | DNA Ligase IV | Inhibits the final ligation step in c-NHEJ [39]. | Up to 4-fold [39] | Specificity can vary between commercial sources. |

| KU-0060648 | DNA-PKcs | Inhibits DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit activity [7]. | Documented in multiple studies [7] | A potent and specific inhibitor of the NHEJ pathway. |

| RS-1 | RAD51 | Enhances the activity of RAD51, a key protein in the HDR pathway [7]. | Up to 6-fold [7] | Acts by stimulating the core HDR machinery. |

- Synchronize the Cell Cycle: Since HDR is active primarily in the S and G2 phases, synchronizing your cells at these stages can significantly boost HDR efficiency. Use compounds like aphidicolin (to arrest cells at the G1/S boundary) or nocodazole (to arrest cells in G2/M) prior to and during CRISPR-Cas9 delivery [7].

- Utilize High-Fidelity and HDR-Optimized Cas9 Variants: Wild-type Cas9 generates blunt-ended DSBs that are ideal for NHEJ. Consider using Cas9 variants known as "high-fidelity" Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) to reduce off-target effects. Furthermore, novel Cas9 proteins have been fused with specific motifs to interact with HDR proteins (HDR-Cas9), directly recruiting the HDR machinery to the cut site [7].

- Optimize the Donor Template Design: The design and delivery of the donor template are critical.

- Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs): Use ssODNs with symmetric homology arms (30-50 bp on each side) for point mutations or small insertions [40].

- Double-Stranded Donors: For larger insertions, use double-stranded DNA donors (e.g., plasmids) with longer homology arms (≥500 bp). Strategies like using overlapping homology arms can also improve HDR rates [39].

- Protection from Exonucleases: Chemically modify the ends of your donor template (e.g., phosphorothioate linkages) to prevent degradation by cellular exonucleases [40].

Problem: High cell death following CRISPR editing in primary T cells.

Question: I am working with primary human T cells for CAR-T engineering. After nucleofection with CRISPR-Cas9 RNP and a donor template, I observe significant cell death, which compromises the yield of HDR-edited cells. How can I improve cell viability?

Solution: Primary T cells are highly sensitive to transfection and the DNA damage induced by Cas9.

- Use RNP Complexes, Not Plasmid DNA: Deliver the CRISPR machinery as a pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. RNP delivery is fast, leading to a shorter exposure time of Cas9 nuclease, which reduces off-target effects and cellular toxicity. It is also DNA-free, eliminating the risk of random plasmid integration [41] [42].

- Optimize the Nucleofection Protocol: Use a cell-type specific nucleofection program and kit designed for primary T cells. Titrate the amount of RNP complex to find the balance between high editing efficiency and minimal toxicity. Overloading cells with RNP is a common cause of death.

- Fluorescently Label RNP for Enrichment: To quickly identify and enrich successfully transfected cells without relying on HDR, fluorescently label the RNP complex. This allows you to sort and culture only the cells that received the editing machinery, increasing the likelihood of obtaining HDR-edited clones and reducing background from dead or untransfected cells [42].

- Employ Small Molecule Supplements: Add small molecules to the recovery media that enhance cell survival after electroporation. For instance, adding an inhibitor of p53 can transiently reduce DNA damage-induced apoptosis in primary stem cells, and similar strategies can be explored for T cells.

Problem: Persistent protein expression despite confirmed genomic knockout.

Question: I have confirmed by sequencing that my CRISPR edit successfully introduced a frameshift mutation in the target gene. However, my Western blot and functional assays show persistent, albeit sometimes lower, protein expression. What could be happening?

Solution: This is a common issue often related to protein stability, alternative splicing, or the specific edit made.

- Confirm Guide RNA Placement: Your sgRNA may not target an exon common to all major protein isoforms. Re-design your sgRNA to target a shared early exon to increase the likelihood of disrupting all functional isoforms [43].

- Consider Alternative Start Codons and Truncated Proteins: A frameshift mutation may not introduce a premature stop codon immediately. Even if it does, the cell may use a downstream alternative start codon (ATG) to produce a truncated but still partially functional protein. Analyze the predicted mRNA transcript from your edited sequence [43].

- Account for Protein Half-Life: The target protein may be very stable and have a long half-life. Protein expression assays performed immediately after editing may still detect pre-existing protein. Allow sufficient time (several cell doublings) for the existing protein to dilute out before performing your assay [43] [44].

- Validate at the Clonal Level: The pooled cell population after editing is a mixture of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous edited cells. The signal from unedited cells can mask the knockout in edited ones. Isolate single-cell clones and validate the knockout in a pure clonal population where the genomic edit is biallelic [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Pathway Engineering

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Shifting the NHEJ-HDR Balance

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., SCR7, KU-0060648) | Chemically block key proteins in the NHEJ pathway, reducing error-prone repair. | Shifting repair balance toward HDR by suppressing the competing pathway [39] [7]. |

| HDR Enhancers (e.g., RS-1) | Stimulate the activity of core HDR proteins like RAD51 to promote homologous recombination. | Actively increasing the efficiency and capacity of the HDR machinery [7]. |

| Cell Cycle Synchronizers (e.g., Aphidicolin, Nocodazole) | Arrest cells at specific cell cycle phases (S/G2) where HDR is active. | Creating a cellular environment that is primed for HDR-mediated repair [7]. |

| HDR-Optimized Cas9 Variants (e.g., miCas9, eCas9) | Engineered Cas9 proteins with higher fidelity or fused to HDR-promoting peptides. | Reducing off-target effects while directly recruiting the cellular HDR machinery to the DSB [7]. |

| Chemically Modified Donor Templates | Donor DNA with stabilized ends (e.g., phosphorothioated) to resist degradation. | Increasing the intracellular availability and stability of the HDR template [40]. |

| Fluorescently Labeled RNP | Cas9-gRNA complexes tagged with a fluorophore (e.g., CX-rhodamine) for visualization. | Enabling FACS-based enrichment of transfected cells, crucial for hard-to-transfect primary cells [42]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

NHEJ vs HDR Pathway Competition

Experimental Workflow for Optimizing Knock-In

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: What is AZD7648 and how does it enhance HDR efficiency?

Answer: AZD7648 is a highly potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor of the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). It enhances Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) efficiency by strategically manipulating the cellular DNA repair machinery.

- Mechanism of Action: The CRISPR-Cas9 system creates double-strand breaks (DSBs). In mammalian cells, the dominant repair pathway is Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), which is error-prone. DNA-PKcs is a critical kinase that promotes NHEJ and actively represses the HDR pathway [40] [12]. By inhibiting DNA-PKcs, AZD7648 suppresses the competing NHEJ pathway, thereby redirecting the cell's repair resources toward the more precise HDR mechanism when a donor template is present [45] [46]. This shift in the repair balance can lead to a significant increase in the frequency of precise gene edits.

FAQ: What are the key risks and considerations when using AZD7648?

Answer: Recent studies have revealed that while AZD7648 can dramatically increase HDR rates measured by standard short-read sequencing, it also introduces a significant risk of large-scale, on-target genomic alterations that often evade conventional detection methods [45].

The primary risk is the induction of large-scale genomic alterations, including:

- Kilobase-scale and megabase-scale deletions

- Chromosome arm loss

- Translocations [45]

These events are concerning because they are frequently missed by standard short-range PCR amplification and short-read sequencing assays, which can lead to an overestimation of true HDR efficiency and a failure to detect these potentially harmful genotoxic outcomes [45].

Troubleshooting Guide: My HDR efficiency is still low after using AZD7648. What can I optimize?

Answer: Low HDR efficiency can be multifactorial. Beyond adding a small-molecule enhancer, consider optimizing these key parameters of your experiment.

Problem 1: Suboptimal Donor Template Design.

- Solution: Ensure your homology arms are sufficiently long. For single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs), arms of 30-50 nucleotides are common, but for larger insertions via plasmid donors, arms of 500-1000 base pairs can improve efficiency [47]. Critically, disrupt the PAM site or the sgRNA binding sequence in your donor template to prevent continuous re-cleavage of the successfully edited locus by Cas9 [47].

Problem 2: Poor Transfection and Cell Health.

- Solution: For sensitive primary cells like Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cells (HSPCs), extended ex vivo culture can be detrimental. Integrate a p38 inhibitor into your culture medium to reduce detrimental cellular stress responses and help preserve the long-term functionality of edited cells [48]. Always use healthy, high-viability cells and optimize delivery methods (e.g., electroporation parameters).

Problem 3: Incorrect AZD7648 Dosing or Timing.

- Solution: Adhere to published protocols for dosing. The compound should be present during and after the gene editing event to effectively bias the repair pathway. Refer to established workflows for the timing of addition and removal [46].

Quantitative Data on AZD7648 Performance

The following table summarizes quantitative findings on AZD7648's efficacy and risks from recent studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Genome Editing with AZD7648

| Cell Type | Target Locus | Key Finding (Efficacy) | Key Finding (Risk) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPCs (Mobilized Peripheral Blood) | CD40LG | ~60% HDR efficiency; 1.6-fold increase in HDR-edited long-term HSPCs in xenotransplants [46] | Not specifically assessed | [46] |

| RPE-1 p53-null cells | GAPDH | Marked increase in apparent HDR by short-read sequencing [45] | 43.3% of reads contained kilobase-scale deletions (a 35.7-fold increase) [45] | [45] |

| Primary Human HSPCs (Donors) | Multiple Loci | Increased apparent HDR [45] | 1.2 to 4.3-fold increase in kilobase-scale deletions [45] | [45] |

| Upper Airway Organoids | GAPDH 3' UTR | Increased apparent HDR [45] | Up to 47.8% of cells showed loss of a 6.5 Mb telomeric segment [45] | [45] |

Troubleshooting Guide: How can I properly assess editing outcomes when using HDR enhancers?

Answer: Relying solely on short-read sequencing (e.g., Illumina) of small amplicons around the cut site is insufficient and can be misleading. A comprehensive analysis strategy is required to detect the full spectrum of editing outcomes.

- Problem: Inadequate detection of large structural variations.

- Solution: Implement orthogonal assays to capture different types of edits.

- Long-Range PCR & Long-Read Sequencing (e.g., Nanopore): Essential for detecting kilobase-scale deletions that cause "allelic dropout" in short-range PCR [45].

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): Precisely quantifies copy number variations (e.g., gene loss) across large genomic distances [45].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Can identify large heterozygous deletions through the loss of coherent blocks of gene expression in the edited region [45].