SOX9 in Autoimmunity and Inflammation: A Janus-Faced Regulator in Disease Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Development

This article comprehensively examines the dual role of the transcription factor SOX9 in autoimmune and inflammatory disorders.

SOX9 in Autoimmunity and Inflammation: A Janus-Faced Regulator in Disease Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Development

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the dual role of the transcription factor SOX9 in autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge of SOX9's structure and its context-dependent functions as both a driver of pathology and a mediator of tissue repair. The scope spans exploratory mechanisms in diseases like thyroid eye disease and osteoarthritis, methodological advances in targeting SOX9, strategies to navigate its complex biology, and comparative analyses validating its prognostic and therapeutic utility. The review aims to bridge molecular understanding with clinical translation, highlighting SOX9's emerging promise as a biomarker and therapeutic target.

The Dual Nature of SOX9: Unraveling Its Structure and Context-Dependent Roles in Immunity

The SOX9 (SRY-related HMG-box 9) protein is a transcription factor belonging to the SOX family, characterized by a conserved high-mobility group (HMG) box DNA-binding domain. As a pivotal regulator of diverse developmental processes, SOX9 functions as a master controller of chondrogenesis, male sex determination, gliogenesis, and numerous other differentiation pathways. In the context of autoimmune diseases and inflammatory disorders, SOX9 has emerged as a significant autoantigen and regulatory factor, with demonstrated roles in conditions such as autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I (APS I) and vitiligo [1] [2]. Understanding the precise architectural organization of SOX9—its functional domains, DNA-binding specificity, and regulatory mechanisms—provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for these conditions. This technical guide comprehensively details the protein architecture of SOX9, with particular emphasis on aspects relevant to immune dysregulation and inflammatory disease pathogenesis.

SOX9 Domain Architecture and Functional Organization

The functional capabilities of SOX9 are encoded within a modular domain structure that facilitates DNA binding, dimerization, transcriptional activation, and protein-protein interactions. The human SOX9 protein comprises 509 amino acids organized into several functionally distinct domains [3].

Table 1: Functional Domains of Human SOX9 Protein

| Domain Name | Position | Key Functions | Molecular Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimerization Domain (DIM) | N-terminal | Facilitates SOX9 self-association | Critical for functional plasticity and partner interaction [4] |

| HMG Box | Central | DNA binding and bending; nuclear localization | Contains nuclear localization (NLS) and export (NES) signals; binds sequence (A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G [4] [3] [5] |

| Transcriptional Activation Domain Middle (TAM) | Central | Transcriptional activation | Synergizes with TAC; interaction platform for cofactors [3] |

| Transcriptional Activation Domain C-terminal (TAC) | C-terminal | Primary transcriptional activation | Interacts with cofactors (e.g., Tip60); inhibits β-catenin in chondrogenesis [3] |

| PQA-rich Domain | C-terminal | Transcriptional enhancement | Proline/Glutamine/Alanine-rich; enhances transactivation potential [4] [3] |

The DIM domain enables SOX9 dimerization, which is essential for its transcriptional regulatory functions. The central HMG domain represents the core DNA-binding module that confers sequence-specific DNA recognition and bending. The transactivation domains (TAM and TAC) facilitate recruitment of transcriptional co-regulators, while the PQA domain provides additional transactivation capacity, particularly in mammalian systems [4] [3].

Evolutionary analyses reveal that the DIM and TAD domains exhibit higher tolerance for molecular changes (as indicated by elevated Ka/Ks ratios) compared to the HMG box, suggesting these domains contribute significantly to SOX9's functional plasticity and ability to undergo subfunctionalization, as observed in teleost duplicates Sox9a and Sox9b [4].

DNA-Binding Specificity and Mechanisms

The DNA-binding specificity of SOX9 is primarily determined by its HMG box domain, which recognizes and binds to specific DNA sequences through minor groove interactions.

Core Binding Motif and Flanking Sequences

Systematic analyses using random oligonucleotide selection assays have defined the optimal SOX9 binding sequence as AGAACAATGG [5]. This sequence contains the core SOX family binding element AACAAT, flanked by 5' AG and 3' GG nucleotides, which enhance binding specificity for SOX9.

Table 2: DNA-Binding Specificity of SOX9 HMG Domain

| Binding Element | Sequence | Relative Binding Affinity | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimal SOX9 Site | AGAACAATGG | Highest | Confirmed by EMSA, competition, dissociation studies [5] |

| Core SOX Element | AACAAT | Moderate | Common binding motif for SOX family proteins [5] |

| SRY Preference | Differing flanking nucleotides | Lower for SOX9 | Demonstrates specificity among SOX family members [5] |

The DNA-binding mechanism involves SOX9-induced DNA bending, which facilitates the assembly of enhanceosome complexes through recruitment of additional transcriptional co-regulators. This bending is achieved through intercalation of specific hydrophobic amino acid residues from the HMG domain into the DNA minor groove, creating a significant bend angle that promotes chromatin remodeling and transcriptional activation [4].

Transcriptional Regulation of Target Genes

Through its DNA-binding capability, SOX9 directly regulates numerous target genes involved in development and disease, including:

- Col2a1: Encodes type II collagen, essential for cartilage matrix [6]

- Aggrecan: Major proteoglycan in cartilage extracellular matrix [6]

- COL11A2: Fibrillar collagen component of cartilage [6]

- Hexokinase 1 (Hk1): Key glycolytic enzyme implicated in neuropathic pain [7]

The specificity of SOX9 for its target genes is further refined through cooperative interactions with partner transcription factors and contextual cellular cues.

SOX9 Regulation and Post-Translational Modifications

SOX9 activity is subject to complex regulatory controls, including transcriptional, post-translational, and epigenetic mechanisms. Phosphorylation represents a particularly significant regulatory mechanism with implications for disease pathogenesis.

Phosphorylation at Serine 181

Phosphorylation at serine 181 (S181) represents a critical regulatory switch controlling SOX9 function:

- Subcellular localization: Phosphorylation enhances nuclear translocation and DNA binding [7]

- Transcriptional activity: Phosphorylated SOX9 exhibits enhanced transactivation of target genes [8]

- Pathological implications: Elevated pSOX9 levels are observed in systemic sclerosis (SSc) fibroblasts and contribute to fibrotic processes [8]

In neuropathic pain models, nerve injury induces aberrant SOX9 phosphorylation, triggering increased transcription of hexokinase 1 (Hk1) and resulting in heightened glycolytic flux in astrocytes [7]. The resulting lactate overproduction promotes histone lactylation (H3K9la), which remodels chromatin to favor expression of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic genes, ultimately establishing chronic pain states [7].

Transcriptional Regulation of SOX9 Expression

SOX9 expression is itself regulated at the transcriptional level, primarily through its promoter region which contains two functional CCAAT boxes (CCAAT-1 and CCAAT-2) that bind the CCAAT-binding factor (CBF/NF-Y) [6]. Mutation or deletion of these CCAAT boxes significantly diminishes SOX9 promoter activity, highlighting their essential role in SOX9 transcription [6].

Additional regulatory inputs include:

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-1β and TNF-α suppress SOX9 expression via NF-κB signaling [6] [9]

- Growth factors: FGFs upregulate SOX9 through MAP kinase pathways [6]

- NF-κB signaling: Directly binds SOX9 promoter to positively regulate expression in osteoarthritis [9]

SOX9 in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disease Contexts

SOX9 as an Autoantigen

SOX9 functions as an autoantigen in autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type I (APS I), with approximately 15% of APS I patients exhibiting immunoreactivity against SOX9 [1] [2]. Notably, among APS I patients with vitiligo, 63% show positive reactivity against SOX10 (a SOX9-related protein), and all SOX9-reactive patients also display SOX10 reactivity, suggesting shared epitopes between these SOX family members [1]. This autoantigen status positions SOX9 as a significant factor in autoimmune disease pathogenesis.

SOX9 in Fibrotic Disorders

In systemic sclerosis (SSc), phosphorylated SOX9 (pSOX9) contributes to the persistent activation of myofibroblasts, the effector cells responsible for excessive extracellular matrix deposition characteristic of fibrosis [8]. TGF-β potently stimulates pSOX9 levels, establishing a pro-fibrotic feedback loop that drives disease progression [8].

Experimental Analysis of SOX9 Function

Key Methodologies for SOX9 Investigation

Table 3: Essential Experimental Protocols for SOX9 Functional Analysis

| Method | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) | Identify direct SOX9 target genes; map binding sites | Use validated SOX9 antibodies; include negative control regions |

| Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA) | Detect protein-protein interactions in situ | Optimize antibody concentrations; include single-antibody controls [10] |

| RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) | Investigate SOX9-RNA interactions | Cross-linking methods preserve transient interactions [10] |

| Luciferase Reporter Assays | Measure SOX9 transcriptional activity | Include SOX-binding (SOX) and control (SAC) constructs [10] |

| Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) | Analyze DNA-binding specificity | Use purified HMG domain; include competition experiments [5] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Determine functional domain requirements | Target key residues (e.g., S181, W143R) [10] [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for SOX9 Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Applications and Functions |

|---|---|---|

| SOX9 Antibodies | Mouse monoclonal anti-SOX9 (Sigma-Aldrich); Rabbit anti-SOX9 (Merck) | Western blot, immunofluorescence, PLA, ChIP [10] |

| Expression Constructs | N-terminally FLAG-tagged wild-type SOX9 (pcDNA3); SOX9 mutants (K68E, R94H, W143R) | Functional domain analysis; structure-function studies [10] [4] |

| Reporter Systems | SOX-luciferase reporter (7× AACAAAG); Control SAC-luciferase | Transcriptional activity measurement [10] |

| SOX9 Mutants | DelDIM (dimerization deficient); MiniSOX9 | Domain functional analysis [10] [4] |

| Knockdown Approaches | SOX9-specific siRNAs | Functional validation; target gene identification [10] |

| Interaction Partner Antibodies | Anti-p54nrb, Anti-PSF, Anti-Y14, Anti-SAM68 | Co-immunoprecipitation; PLA for complex detection [10] |

SOX9-RNA Binding and Splicing Regulation

Beyond its canonical function as a transcription factor, SOX9 exhibits RNA-binding capacity and regulates alternative splicing of hundreds of genes independently of its transcriptional activity [10]. SOX9 associates with several RNA-binding proteins, including the core exon junction complex component Y14, and approximately half of SOX9 splicing targets require Y14 for regulation [10]. This moonlighting function expands the mechanistic repertoire of SOX9 in gene regulation.

SOX9 represents a multifunctional regulatory protein with complex domain architecture that facilitates its diverse roles in development, homeostasis, and disease. The modular organization of SOX9—comprising dimerization, DNA-binding, and transactivation domains—enables context-dependent functions through differential protein interactions and post-translational modifications. In autoimmune and inflammatory disease contexts, SOX9 operates as both an autoantigen and a pathogenic regulator, contributing to conditions including vitiligo, systemic sclerosis, and neuropathic pain through distinct molecular mechanisms. The experimental frameworks and reagent tools outlined in this guide provide foundational resources for advancing SOX9-focused research, with particular relevance for therapeutic development targeting SOX9 in immune-related pathologies.

SOX9 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 9) is emerging as a critical transcription factor with remarkably dualistic functions in immune and inflammatory regulation. As a member of the SOX family characterized by a conserved high-mobility group (HMG) box DNA-binding domain, SOX9 plays essential roles in development, chondrogenesis, and stem cell maintenance [3] [11]. Recent research has illuminated its complex, context-dependent roles in immunological processes, where it can simultaneously drive pro-inflammatory pathways in certain environments while exerting protective, anti-inflammatory effects in others [3]. This dichotomous nature positions SOX9 as a "Janus-faced" regulator with significant implications for understanding autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders, and cancer immunology. The precise molecular mechanisms that determine SOX9's functional orientation remain a vibrant area of investigation, particularly within the broader context of autoimmune disease and inflammatory disorder research. This technical guide comprehensively examines the molecular basis for SOX9's dual immune functions, analyzes its roles in specific pathological contexts, and provides detailed experimental methodologies for researchers investigating this multifaceted regulator.

Structural Basis and Molecular Mechanisms of SOX9 Function

Protein Architecture and Functional Domains

The SOX9 protein contains several structurally and functionally distinct domains that enable its diverse regulatory capabilities. The N-terminal dimerization domain (DIM) facilitates protein-protein interactions, while the central HMG box domain mediates sequence-specific DNA binding, nuclear localization, and DNA bending [3]. This domain contains embedded nuclear localization (NLS) and nuclear export (NES) signals that enable nucleocytoplasmic shuttling [3]. The C-terminal region houses two transcriptional activation domains - a central transcriptional activation domain (TAM) and a C-terminal transcriptional activation domain (TAC) - which interact with various cofactors like Tip60 to enhance transcriptional activity [3]. Additionally, a proline/glutamine/alanine (PQA)-rich domain is essential for full transcriptional activation potential [3].

Table 1: Functional Domains of SOX9 Protein

| Domain | Position | Key Functions | Interacting Partners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimerization Domain (DIM) | N-terminal | Protein-protein interactions, dimer formation | Other SOX9 molecules, transcription cofactors |

| HMG Box Domain | Central | DNA binding, nuclear localization, DNA bending | Specific DNA sequences (CCTTGAG), importin proteins |

| Transcriptional Activation Domain (TAM) | Central | Transcriptional activation | Transcriptional co-activators |

| Transcriptional Activation Domain (TAC) | C-terminal | Transcriptional activation, β-catenin inhibition | Tip60, β-catenin |

| PQA-rich Domain | C-terminal | Transcriptional activation | Transcriptional machinery components |

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Interactions

SOX9 participates in multiple signaling networks that contextualize its dual immune functions. In neuropathic pain, SOX9 transcriptionally regulates hexokinase 1 (HK1), catalyzing the rate-limiting first step of glycolysis [7]. Nerve injury induces abnormal SOX9 phosphorylation at serine 181, triggering aberrant HK1 activation and high-rate astrocytic glycolysis [7]. The resulting excessive lactate production remodels histone modifications via lactylation (H3K9la), promoting transcriptional activation of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic genes [7]. This SOX9-HK1-H3K9la axis represents a crucial immunometabolic pathway in neuroinflammation.

In cartilage and inflammatory joint environments, SOX9 interacts with the NF-κB signaling pathway, which can positively regulate SOX9 expression by directly binding to its promoter region [9]. The NF-κB-SOX9 signaling axis contributes significantly to osteoarthritis pathogenesis, linking inflammation with cartilage homeostasis disruption [9]. Additionally, computational docking analyses reveal that pharmaceutical agents like Lopinavir/Ritonavir can interact with osteoarthritis-related targets including HIF-1α, SOX9, and IL-1β, suggesting modulation of hypoxic, inflammatory, and epigenetic pathways [12].

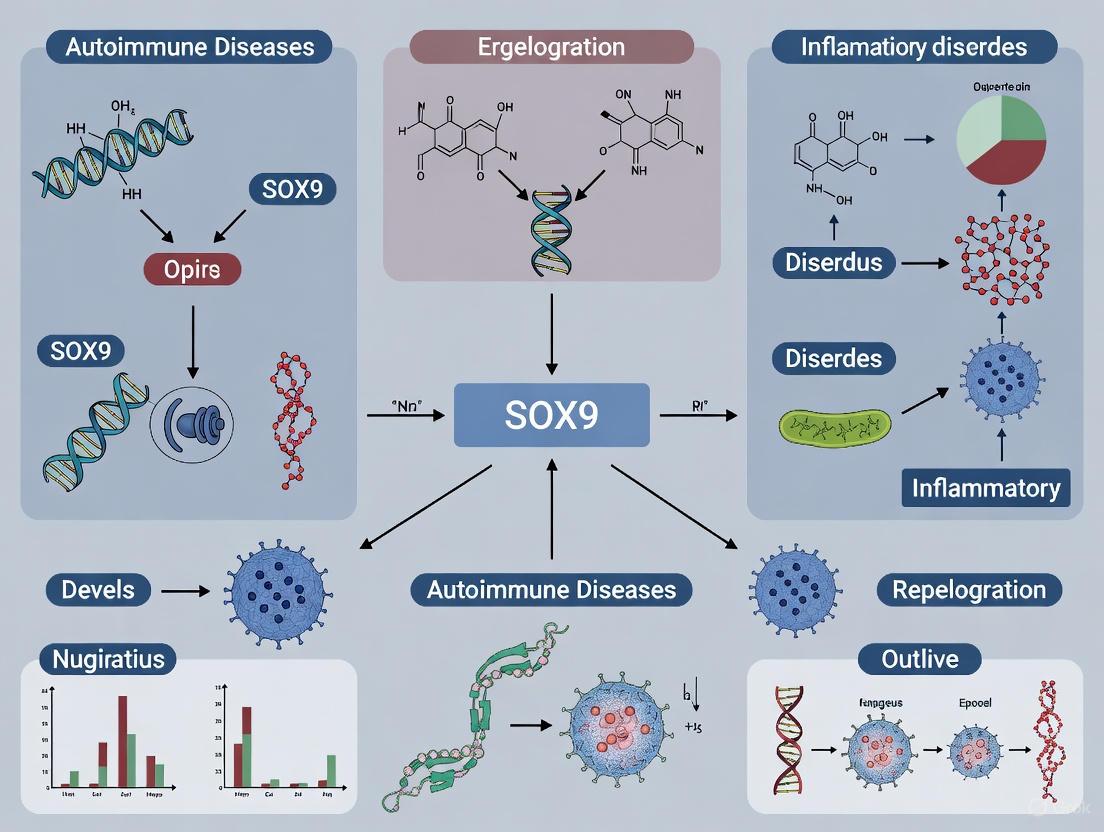

Figure 1: SOX9-Driven Pro-Inflammatory Pathway in Neuropathic Pain. This diagram illustrates the SOX9-HK1-H3K9la axis through which SOX9 activation promotes neuroinflammation following nerve injury.

Pro-Inflammatory Functions of SOX9

SOX9 in Neuroinflammation and Pain Pathogenesis

Single-cell RNA sequencing studies of dorsal spinal astrocytes in neuropathic pain models have revealed distinct astrocyte subpopulations with SOX9 playing a central role in driving pro-inflammatory phenotypes [7]. Following nerve injury, SOX9 phosphorylation triggers a metabolic shift toward heightened glycolysis through HK1 activation, resulting in lactate production and subsequent histone lactylation that promotes expression of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic genes [7]. This mechanism drives the expansion of pathogenic astrocyte clusters (particularly Astro1) characterized by elevated expression of pro-inflammatory signaling molecules (NF-κB pathway components, Gstm1) and neurotoxic factors (C3, Cfb) [7]. These SOX9-driven neuroinflammatory astrocytes sustain central sensitization and chronic pain states even after peripheral injury resolution.

SOX9 in Tumor Immunosuppression

In cancer contexts, SOX9 frequently exhibits pro-tumorigenic and immunosuppressive functions. Bioinformatics analyses of tumor microenvironment data reveal that SOX9 overexpression negatively correlates with anti-tumor immune cell infiltration and function [3]. Specifically, SOX9 expression shows negative correlations with infiltration levels of B cells, resting mast cells, resting T cells, monocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils, while positively correlating with neutrophils, macrophages, activated mast cells, and naive/activated T cells [3]. Furthermore, SOX9 overexpression negatively correlates with genes associated with the cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and M1 macrophages [3]. This immunomodulatory capacity enables SOX9 to facilitate tumor immune escape by creating an "immune desert" microenvironment that suppresses effective anti-tumor immunity [3].

Table 2: SOX9 Correlation with Immune Cell Infiltration in Cancer

| Immune Cell Type | Correlation with SOX9 Expression | Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| B Cells | Negative | Reduced antibody production, impaired humoral immunity |

| Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cells | Negative | Diminished tumor cell killing capacity |

| NK Cells | Negative | Reduced innate immune surveillance |

| M1 Macrophages | Negative | Decreased pro-inflammatory, anti-tumor responses |

| Neutrophils | Positive | Increased immunosuppressive microenvironment |

| M2 Macrophages | Positive | Enhanced tissue repair, pro-tumor functions |

| Tregs | Positive | Suppressed effector T cell responses |

Protective and Anti-Inflammatory Functions of SOX9

SOX9 in Tissue Homeostasis and Resolution of Inflammation

In direct contrast to its pro-inflammatory roles, SOX9 demonstrates significant protective functions across multiple tissue contexts. In Alzheimer's disease research, boosting SOX9 expression in astrocytes enhanced clearance of amyloid-β plaques through increased phagocytic activity, effectively acting as a "vacuum cleaner" to remove toxic protein aggregates [13]. Importantly, in symptomatic Alzheimer's mouse models that already exhibited cognitive impairment and established plaque pathology, elevating SOX9 levels improved cognitive performance and reduced plaque burden over time [13]. This suggests SOX9 enhancement represents a natural, cell-based mechanism to combat neurodegenerative decline.

In dental pulp inflammation models, SOX9 acts as a critical maintainer of tissue homeostasis. Normal dental pulp tissue exhibits strong SOX9 expression (76.56% positive cells), which significantly decreases in inflamed pulp (16.40% positive cells) [14] [15]. SOX9 knockdown experiments demonstrate that reduced SOX9 expression inhibits type I collagen production, stimulates MMP2 and MMP13 enzymatic activities, and regulates IL-8 secretion [14]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation confirms SOX9 protein directly binds to MMP-1, MMP-13, and IL-8 gene promoters, with this binding reduced by TNF-α treatment [15]. These findings position SOX9 as a key regulator of extracellular matrix balance and inflammatory mediator production in tissue-specific contexts.

SOX9 in Cartilage Integrity and Joint Homeostasis

In osteoarthritis, SOX9 plays complex, context-dependent roles in maintaining cartilage integrity. While certain inflammatory conditions can exploit SOX9 activities for pathological outcomes, in joint homeostasis SOX9 serves as a "master regulator" of chondrocyte function [9] [16]. SOX9 is essential for chondrocyte differentiation and directly regulates expression of cartilage-specific genes and extracellular matrix components including collagen type II and aggrecan [16]. The transcription factor cooperates with SOX5 and SOX6 to maintain chondrocyte phenotype and cartilage structural integrity [16]. Research demonstrates elevated SOX9 mRNA expression in OA-affected articular cartilage compared to control tissue, suggesting a compensatory mechanism to counteract disease progression [16].

Figure 2: Context-Dependent Outcomes of SOX9 Modulation. This diagram illustrates how SOX9 enhancement produces protective effects in neurodegenerative contexts while SOX9 reduction promotes inflammatory responses in peripheral tissues.

Experimental Approaches and Research Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Investigating SOX9 in Inflammatory Models

SOX9 Knockdown in Human Dental Pulp Cells (HDPCs) to Study Inflammatory Responses

Objective: To elucidate SOX9's role in regulating extracellular matrix balance, cytokine expression, and immune cell recruitment in inflammatory contexts.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Maintain HDPCs in appropriate growth media. Treat cells with recombinant human TNF-α (10-50 ng/mL) or P. gingivalis lysate to induce inflammatory conditions.

- SOX9 Knockdown: Transfert HDPCs with SOX9-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) using lipid-based transfection reagents. Include scrambled siRNA as negative control.

- Gene Expression Analysis:

- Extract total RNA using TRIzol reagent

- Perform quantitative PCR (qPCR) with SOX9-specific primers

- Analyze expression of extracellular matrix genes (COL1A1, MMP1, MMP2, MMP13) and inflammatory mediators (IL-8)

- Protein Analysis:

- Perform Western blotting to confirm SOX9 knockdown at protein level

- Use gelatin/collagen zymography to assess MMP enzymatic activity

- Cytokine Profiling:

- Analyze culture supernatants using antibody arrays to screen multiple cytokines

- Validate key findings with ELISA for IL-8 quantification

- Immune Cell Functional Assays:

- Condition media from SOX9-knockdown HDPCs and apply to THP-1 monocyte cultures

- Perform cell migration assays using transwell systems

- Assess cell attachment and phagocytic activity

- Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP):

- Crosslink proteins to DNA with formaldehyde

- Immunoprecipitate with SOX9-specific antibody

- Analyze bound DNA fragments for MMP-1, MMP-13, and IL-8 promoter regions

Expected Outcomes: Successful SOX9 knockdown should result in reduced type I collagen production, increased MMP2 and MMP13 activity, elevated IL-8 secretion, and enhanced monocyte recruitment and activation [14] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SOX9 Immunology Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOX9 Modulation | SOX9 siRNA, SOX9 overexpression plasmids, CRISPR/Cas9 SOX9 knockout systems | Gain/loss-of-function studies | Validate efficiency via qPCR and Western blot |

| Cell Culture Models | Human dental pulp cells (HDPCs), primary chondrocytes, astrocytes, cancer cell lines | Tissue-specific functional studies | Primary cells better reflect physiological responses |

| Inflammation Inducers | Recombinant human TNF-α, P. gingivalis lysate, LPS | Establishing inflammatory conditions | Optimize concentration and exposure time |

| Analysis Antibodies | Anti-SOX9 (ChIP-grade), anti-collagen I, anti-MMP2/13, anti-IL-8 | Protein detection, localization, ChIP | Verify antibody specificity for application |

| Molecular Biology Assays | qPCR primers for SOX9/target genes, gelatin/collagen zymography kits | Gene expression, enzymatic activity | Include proper controls for zymography |

| Animal Models | Spared nerve injury (SNI) rats, Alzheimer's mouse models, osteoarthritis models | In vivo validation | Choose model relevant to research question |

Research Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The dual nature of SOX9 as both pro-inflammatory and protective regulator presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development. In cancer contexts, SOX9 inhibition may counteract immunosuppression and enhance anti-tumor immunity [3] [11]. Conversely, in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, SOX9 enhancement could promote clearance of pathological protein aggregates [13]. In inflammatory joint diseases, the situation is particularly complex, as SOX9 contributes to both cartilage maintenance and pathological processes [12] [9] [16].

Drug development strategies must account for this context dependence. Computational analyses suggest existing pharmaceuticals like Lopinavir/Ritonavir can interact with the SOX9-HIF-1α-IL-1β network, potentially offering repurposing opportunities for osteoarthritis treatment [12]. Future research should focus on identifying the precise molecular switches that determine SOX9's functional orientation in specific tissues and disease states, potentially enabling development of context-specific therapeutics that can either inhibit or enhance SOX9 activity based on therapeutic need.

For researchers in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, SOX9 represents a compelling target that integrates metabolic programming (glycolysis), epigenetic regulation (histone lactylation), and immune cell function—three pillars of modern immunology research. The experimental frameworks and technical resources provided in this guide offer foundational methodologies for advancing our understanding of this multifaceted transcription factor and harnessing its therapeutic potential.

The transcription factor SOX9 (SRY-box transcription factor 9) has emerged as a critical regulator of fibrotic processes across diverse organ systems and disease contexts. Originally identified for its fundamental role in developmental processes including chondrogenesis and sex determination, SOX9 is now recognized as a central mediator of pathological fibrosis—a common endpoint in chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases characterized by excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition that leads to tissue scarring and organ dysfunction [17] [18]. This whitepaper synthesizes current mechanistic understanding of SOX9-driven fibrogenesis, with specific focus on its roles in thyroid eye disease (TED), schistosomiasis-induced liver fibrosis, and hepatic fibrosis, contextualized within the broader framework of autoimmune and inflammatory disorder research. The findings presented herein underscore SOX9's potential as a therapeutic target for antifibrotic interventions.

SOX9 Expression and Function in Fibrotic Diseases: Quantitative Evidence

Table 1: SOX9-Associated Fibrotic Markers Across Disease Contexts

| Disease Context | SOX9 Expression Change | Key Regulated ECM Components | Functional Consequences | Experimental Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thyroid Eye Disease | Significantly increased in TED orbital fibroblasts vs. healthy controls [19] | COL1, OPN, FN1, VIM [19] | Enhanced contraction, migration, proliferation, antiapoptotic ability of OFs [19] | Primary human OF cultures (TED: n=10; controls: n=6) [19] |

| Liver Fibrosis (General) | Upregulated in activated hepatic stellate cells [20] | OPN, GPNMB, FN1, SPARC, VIM [20] | Progressive ECM deposition, scarring, impaired liver function [20] | CCl4 and BDL mouse models; human patient serum [20] |

| Schistosomiasis-Associated Liver Fibrosis | Ectopically expressed in myofibroblasts within granuloma and hepatocytes [21] | Collagens, granuloma-associated ECM components [21] | Disorganized granuloma formation, diffuse liver injury [21] | S. mansoni-infected SOX9-deficient mice [21] |

| Tracheal Fibrosis | Upregulated in TGF-β1-treated tracheal fibroblasts [22] | MMP10, COL1, other ECM components via Wnt/β-catenin [22] | Fibroblast activation, proliferation, apoptosis resistance [22] | Rat tracheal fibroblast (RTF) models [22] |

Table 2: Quantitative Changes in SOX9-Regulated ECM Proteins in Liver Fibrosis Patient Serum

| SOX9 Target Protein | Change in Fibrosis | Performance as Biomarker | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteopontin (OPN) | Significantly increased [20] | Superior to established clinical biomarkers for early-stage detection [20] | Directly regulated by SOX9; strongly correlates with fibrosis severity [20] |

| Vimentin (VIM) | Significantly increased [20] | Superior to established clinical biomarkers for early-stage detection [20] | Correlates with fibrosis severity; may be indirectly regulated by SOX9 [20] |

| Fibronectin (FN1) | Significantly increased [20] | Effective for fibrosis stratification [20] | Direct SOX9 target with conserved binding motifs [20] |

| Osteoactivin (GPNMB) | Significantly increased [20] | Effective for fibrosis stratification [20] | Contains conserved SOX9 binding motifs; confirmed by ChIP [20] |

| Osteonectin (SPARC) | Significantly increased [20] | Effective for fibrosis stratification [20] | Direct SOX9 target with conserved binding motifs [20] |

Disease-Specific Mechanistic Insights

Thyroid Eye Disease (TED)

In TED, an autoimmune disorder, SOX9 is significantly overexpressed in orbital fibroblasts (OFs) compared to healthy controls [19]. Mechanistically, SOX9 drives fibrotic pathogenesis through multiple pathways. It directly binds to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promoter, activating the MAPK/ERK1/2 signaling pathway, which in turn promotes OF proliferation, differentiation, contractility, and migration [19]. SOX9 also transcriptionally regulates numerous extracellular matrix (ECM)-related genes, creating a profibrotic cellular environment. Experimental SOX9 knockdown ameliorates these effects, while its overexpression exacerbates the fibrotic phenotype [19].

Schistosomiasis-Associated Liver Fibrosis

During Schistosoma mansoni infection, SOX9 becomes ectopically expressed in hepatic myofibroblasts within egg granulomas and surrounding hepatocytes [21]. This expression is crucial for forming organized granulomatous barriers that contain toxic egg secretions. SOX9 deficiency results in significantly diminished granuloma size and disrupted ECM barrier formation, leading to more diffuse liver injury and altered immune responses characterized by pronounced eosinophilia and expansion of Ly6clo monocytes [21]. This demonstrates SOX9's critical role in balancing immune cell recruitment and fibrotic containment during parasitic infection.

Liver Fibrosis (General)

In hepatic fibrosis, SOX9 is upregulated in activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs)—the primary fibrogenic cells in the liver [20]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that approximately 30-37% of genes regulated by SOX9 in HSCs are ECM-related [20]. SOX9 directly transcriptionally activates multiple profibrotic factors including osteopontin (OPN), osteoactivin (GPNMB), fibronectin (FN1), osteonectin (SPARC), and vimentin (VIM) through conserved binding motifs in their promoter regions [20]. These SOX9-regulated proteins are significantly elevated in serum from patients with liver fibrosis and correlate with disease severity, suggesting their utility as biomarkers [20].

Core Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Figure 1: SOX9-Regulated Signaling Pathways in Fibrosis. SOX9 operates within a complex network of signaling pathways, including MAPK/ERK, Wnt/β-catenin, and metabolic pathways, to drive fibrotic processes through transcriptional regulation of ECM components and profibrotic factors.

Experimental Methodologies and Research Workflows

Table 3: Key Experimental Approaches for SOX9 Fibrosis Research

| Methodology | Key Applications | Technical Considerations | Representative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cell Culture | Culture of orbital fibroblasts (TED), hepatic stellate cells (liver fibrosis), tracheal fibroblasts [19] [20] [22] | Use early passages (P3-P8); confirm phenotype; maintain from multiple donors [19] | TED-OFs show higher SOX9 vs. controls; enhanced contractility, proliferation [19] |

| SOX9 Modulation | siRNA knockdown; lentiviral overexpression; CRISPR/Cas9; transgenic models [19] [21] [22] | Confirm efficiency via qPCR/Western; use multiple targeting sequences [19] | SOX9 knockdown reduces ECM genes, contraction; overexpression promotes fibrosis [19] |

| Transcriptomic Analysis | RNA-seq; microarray; single-cell RNA-seq; ChIP-seq [19] [20] [7] | Multiple bioinformatics validation; pathway enrichment analysis; integration with ChIP [19] [20] | ~30% SOX9-regulated genes are ECM-related; identified EGFR, MMP10 as direct targets [19] [20] [22] |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation | Identify direct SOX9 target genes; mapping binding sites [19] [20] [22] | Validate antibody specificity; include positive/negative controls; qPCR validation [19] | SOX9 binds promoters of EGFR, OPN, GPNMB, FN1, SPARC [19] [20] |

| Animal Fibrosis Models | CCl4-induced liver fibrosis; bile duct ligation; schistosoma infection; tracheal injury [21] [20] [22] | Use inducible, cell-specific knockout models; monitor survival with global KO [21] | SOX9 deficiency reduces scarring, improves function; disrupts granuloma formation [21] [20] |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for SOX9 Fibrosis Research. Comprehensive approach integrating sample collection, genetic manipulation, multi-omics analysis, functional assays, and clinical validation to elucidate SOX9's role in fibrotic pathogenesis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SOX9 Fibrosis Investigations

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOX9 Modulation Tools | SOX9 siRNA/shRNA; SOX9 overexpression lentiviruses/adenoviruses; Cre-lox conditional KO models [19] [21] [22] | Gain/loss-of-function studies; target validation | Validate efficiency via qRT-PCR/Western; use multiple targeting sequences; control for off-target effects [19] |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary orbital fibroblasts (TED); hepatic stellate cells; tracheal fibroblasts; immortalized cell lines [19] [20] [22] | Disease-specific mechanistic studies; drug screening | Use early passages; confirm phenotype; maintain cells from multiple donors [19] |

| Antibodies | Anti-SOX9 (ChIP-grade); anti-phospho-SOX9 (S64, S181); anti-ECM proteins (COL1, OPN, FN1); anti-αSMA [19] [20] | Immunofluorescence; Western blot; IHC; ChIP | Verify specificity for application; species compatibility; validate phospho-specific antibodies [19] |

| Animal Models | Inducible SOX9 knockout mice; CCl4 liver fibrosis model; bile duct ligation; schistosoma infection; tracheal injury [21] [20] [22] | In vivo target validation; therapeutic testing | Consider temporal control with inducible systems; monitor animal welfare with global KO [21] |

| Analysis Kits/Assays | Collagen gel contraction assay; EdU proliferation kit; migration assay systems; ELISA for ECM proteins [19] [20] | Functional characterization; biomarker quantification | Standardize conditions across experiments; include appropriate controls [19] |

The accumulated evidence unequivocally establishes SOX9 as a master regulator of fibrotic pathogenesis across multiple disease contexts, including thyroid eye disease, schistosomiasis, and organ fibrosis. SOX9 drives fibrosis through conserved mechanisms involving transcriptional activation of ECM components, regulation of key signaling pathways (MAPK/ERK, Wnt/β-catenin), and modulation of cellular phenotypes including proliferation, contraction, and apoptosis resistance. The consistent finding that SOX9 ablation ameliorates fibrosis across diverse disease models highlights its potential as a promising therapeutic target. Future research should focus on developing cell-specific targeting strategies and small molecule inhibitors directed against SOX9 or its critical downstream effectors to combat fibrotic diseases.

SOX9, a master transcription factor, is indispensable for chondrogenesis and the maintenance of articular cartilage. Its precise regulation ensures a balance between anabolic processes, driven by extracellular matrix (ECM) components like type II collagen and aggrecan, and catabolic processes mediated by enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13). Disruption of SOX9 homeostasis is a hallmark of osteoarthritis (OA), leading to progressive cartilage degradation. This whitepaper delves into the molecular mechanisms governing SOX9 expression and activity, highlighting its role as a pivotal node in the interplay between anabolic and catabolic signaling. Within the broader context of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, understanding the dual-faced nature of SOX9 in tissue homeostasis and inflammation provides critical insights for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for OA and related conditions.

SOX9 is a member of the SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG) box family of transcription factors. In healthy articular cartilage, chondrocytes maintain tissue homeostasis by balancing the synthesis and breakdown of the ECM [23]. SOX9 is a central orchestrator of this equilibrium, directly transactivating genes for essential anabolic components including type II collagen (COL2A1) and aggrecan (ACAN) [24] [25]. It often functions in a trio with the related transcription factors SOX5 and SOX6 to activate the full repertoire of chondrocyte-specific genes [26] [25]. The persistence of chondrocytes and the maintenance of SOX9 activity are what distinguish articular cartilage from the cartilaginous templates that undergo endochondral ossification during skeletal development [23]. The loss of this homeostatic balance, frequently associated with decreased SOX9 function, is a fundamental driver of OA pathology [23] [24].

Molecular Regulation of SOX9

The expression and transcriptional activity of SOX9 are controlled through multiple intricate layers of regulation, ensuring precise spatial and temporal control over chondrocyte function.

Transcriptional and Post-Translational Control

SOX9 protein contains several critical functional domains: a dimerization domain (DIM), the HMG box DNA-binding domain, and two transcriptional activation domains (TAM and TAC) [3]. The HMG domain facilitates nuclear localization and DNA binding, while the TAC domain interacts with cofactors like Tip60 to enhance transcriptional activity [3]. SOX9 activity is significantly modulated by post-translational modifications (PTMs). Phosphorylation can influence its transactivation potential, and sumoylation targets SOX9 for proteasomal degradation [27]. Recent research underscores that SOX9 stability is a critical control point. The E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 targets SOX9 for ubiquitination and degradation, a process that can be counteracted by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP28, which stabilizes the SOX9 protein [28].

Post-Transcriptional Regulation by RNA-Binding Proteins and microRNAs

RNA-binding proteins (RNABPs) are crucial post-transcriptional regulators of SOX9. The RNABP tristetraprolin (TTP) binds to adenine-uracil (AU)-rich elements in the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of SOX9 mRNA, promoting its decay. Knockdown of TTP results in increased SOX9 mRNA half-life and elevated protein expression [27]. Conversely, the RNABP HuR regulates catabolic factors like MMP13 [27]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent another key regulatory layer. For instance, miRNA-145 directly inhibits SOX9 expression, while miRNA-140, whose expression is strengthened by the SOX trio, promotes chondrocyte proliferation [25]. This creates a complex network of checks and balances fine-tuning SOX9 levels.

SOX9 in Cartilage Anabolism and Catabolism

SOX9 sits at the fulcrum of cartilage homeostasis, directly promoting anabolic pathways while suppressing catabolic ones.

SOX9-Driven Anabolic Pathways

SOX9 is the primary factor driving the expression of the major structural components of the cartilage ECM. It binds to enhancer elements in genes such as COL2A1 and ACAN, dramatically upregulating their transcription [25]. This activity is essential for both cartilage development and its maintenance in adulthood. The cooperation between SOX9, SOX5, and SOX6 is particularly important for achieving high-level expression of these genes [26].

SOX9 Dysregulation and Catabolic Activation

In OA, the disruption of SOX9 homeostasis leads to a catabolic shift. Degradation of SOX9, driven by factors like metabolic stress, results in the diminished transcription of COL2A1 and ACAN [24]. Furthermore, SOX9 deficiency can lead to the epigenetic upregulation of major catabolic enzymes. For example, elevated fatty acid oxidation in chondrocytes leads to acetyl-CoA accumulation, which alters histone acetylation patterns and promotes the transcriptional activation of MMP13 and ADAMTS7, even as SOX9 itself is degraded [24]. This creates a vicious cycle of ECM destruction.

Table 1: SOX9 Target Genes in Cartilage Homeostasis

| Gene | Function | Effect of SOX9 | Role in Homeostasis |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL2A1 | Encodes Type II Collagen | Transcriptional Activation | Anabolic: Forms structural fibrillar network of cartilage |

| ACAN | Encodes Aggrecan | Transcriptional Activation | Anabolic: Provides osmotic resistance for load-bearing |

| MMP13 | Encrates Collagenase 3 | Indirect Repression | Catabolic: Degrades Type II collagen; repressed by SOX9 activity |

Metabolic Dysregulation and SOX9 in OA Pathogenesis

Emerging evidence positions OA as a metabolic disease, where lipid and energy metabolism directly impinge upon SOX9 function.

Lipid Stress and SOX9 Degradation

In obesity-related OA (ObOA), synovial fluid contains elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFAs) [24]. Chondrocytes uptake these FFAs, which then undergo mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (FAO). This process yields acetyl-CoA, a key metabolic intermediate. Excessive acetyl-CoA accumulation leads to hyperacetylation and activation of the FAO enzyme HADHA, creating a feed-forward loop that further boosts FAO [24]. Crucially, elevated FAO reduces AMPK activity, which impairs SOX9 phosphorylation. This altered PTM status makes SOX9 more susceptible to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby crippling anabolic functions [24].

Glycolysis and Epigenetic Remodeling

A parallel metabolic pathway, glycolysis, also interfaces with gene regulation in a SOX9-dependent manner. In neuropathic pain models (a different but related pathological state), aberrant SOX9 phosphorylation increases its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation of hexokinase 1 (Hk1), the rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis [7]. The resulting high glycolytic flux produces excessive lactate, which drives histone lactylation (H3K9la) on promoters of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic genes, promoting a pathogenic cellular phenotype [7]. This illustrates a mechanism where SOX9 activity can, under specific pathological metabolic conditions, inadvertently fuel a catabolic state.

The diagram below illustrates the core regulatory network and pathological mechanisms of SOX9 in OA.

Experimental Approaches and Research Reagents

Investigating SOX9 requires a multifaceted approach, from in vitro cell culture to sophisticated molecular biology techniques.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Investigating RNABP Regulation of SOX9 mRNA Stability [27]

- Cell Culture: Use primary human articular chondrocytes (HACs) or SW1353 chondrosarcoma cells. Culture in DMEM with 10% FBS.

- Gene Knockdown: Transfect cells at 90-95% confluence with 10 pmol/cm² of siRNA targeting TTP, HuR, or a non-targeting control siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000.

- mRNA Decay Analysis: 24-48 hours post-transfection, treat cells with a transcriptional inhibitor like Actinomycin D. Harvest cells at time points (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 hours).

- Analysis: Isolate total RNA, perform reverse transcription, and analyze SOX9 mRNA levels using RT-qPCR. Calculate half-life from the decay curve.

- Validation: Confirm protein knockdown and SOX9 protein level changes via western blotting.

Protocol 2: Modeling Lipid Stress and SOX9 Degradation [24]

- In Vitro Model: Treat primary mouse chondrocytes with free fatty acids (FFAs) or adipocyte-conditioned medium (adipo-CM) to mimic lipid stress.

- Assessment:

- ECM Deposition: Use 3D agarose culture or micromass co-culture, staining for proteoglycans (e.g., Alcian Blue) to visualize ECM reduction.

- Gene Expression: Extract RNA from treated chondrocytes and perform RT-qPCR for anabolic (SOX9, COL2A1, ACAN) and catabolic (MMP13) markers.

- Protein Analysis: Perform western blotting to monitor SOX9 protein levels and associated PTMs (e.g., phosphorylation, ubiquitination).

- In Vivo Model: Utilize a high-fat diet (HFD)-fed mouse model subjected to destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) to study metabolism-associated post-traumatic OA.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for SOX9 and Cartilage Homeostasis Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| siRNA (TTP, HuR) | Post-transcriptional gene knockdown | Elucidating RNABP control of SOX9 mRNA stability [27] |

| Free Fatty Acids (FFAs) | Inducing metabolic stress in vitro | Modeling lipid-induced SOX9 degradation and catabolic shift [24] |

| Trimetazidine | FAO inhibitor, AMPK activator | Testing therapeutic intervention in OA models [24] |

| AZ1 (USP28 Inhibitor) | Induces SOX9 degradation via USP28 inhibition | Exploring SOX9 protein stabilization mechanisms [28] |

| Anti-SOX9 Antibody | Protein detection (Western Blot, IHC) | Quantifying SOX9 protein expression and localization [27] [28] |

| HFD-DMM Mouse Model | In vivo model of metabolism-associated OA | Studying SOX9 in a context of obesity and joint injury [24] |

Discussion and Therapeutic Implications

The central role of SOX9 in cartilage homeostasis makes it an attractive yet complex therapeutic target. Its dual nature—essential for anabolism but whose dysregulation can contribute to catabolism—requires nuanced intervention strategies. Simply overexpressing SOX9 may be insufficient if the pathological microenvironment, such as metabolic stress, remains unaddressed.

Promising therapeutic avenues emerging from recent research include:

- Targeting SOX9 Regulators: Inhibiting deubiquitinases like USP28 to promote SOX9 degradation could be explored in contexts where SOX9 is pathologically stabilized, such as in cancer [28]. Conversely, stabilizing SOX9 by targeting its upstream regulators (e.g., with the FAO inhibitor Trimetazidine) shows efficacy in preclinical OA models [24].

- Modulating Metabolic Pathways: Given the strong link between lipid/glucose metabolism and SOX9 stability/function, interventions that normalize chondrocyte metabolism hold great promise for restoring SOX9 homeostasis [7] [24].

- Epigenetic Therapies: Targeting the downstream epigenetic consequences of SOX9 dysregulation, such as specific histone lactylation or acetylation marks, could offer a way to suppress catabolic gene expression without directly manipulating SOX9 itself [24] [29].

In the broader context of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, the immunomodulatory functions of SOX9, including its role in macrophage function and T-cell differentiation, suggest that insights from cartilage biology may have relevance for other inflammatory tissue-destructive diseases [3]. Future research must focus on achieving cell-type and context-specific modulation of SOX9 to halt disease progression and promote genuine cartilage regeneration.

The SRY-related HMG-box 9 (SOX9) transcription factor, a member of the evolutionarily conserved SOX family, has emerged as a critical regulator of tumor progression and immune modulation. Recent research reveals that SOX9 exhibits a dual, "Janus-faced" nature in immunology, functioning as a master orchestrator of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [3]. On one hand, SOX9 promotes tumor immune escape by creating an immunosuppressive niche; on the other hand, it contributes to tissue repair and regeneration in inflammatory contexts [3]. This paradoxical role positions SOX9 at the interface of cancer biology and immunology, offering promising therapeutic avenues for targeting the TME. The protein's functional complexity stems from its multi-domain structure, which includes a dimerization domain (DIM), the characteristic HMG box DNA-binding domain, two transcriptional activation domains (TAM and TAC), and a proline/glutamine/alanine (PQA)-rich domain [3]. This structural composition enables SOX9 to interact with diverse cofactors and target genes, allowing it to regulate wide transcriptional programs that shape immune responses within the TME.

Structural Basis of SOX9 Function

The SOX9 protein contains several functionally specialized domains that enable its role as a transcriptional regulator. The high mobility group (HMG) box domain serves dual purposes: it facilitates DNA binding and contains nuclear localization and export signals that enable nucleocytoplasmic shuttling [3]. The C-terminal transcriptional activation domain (TAC) interacts with cofactors like Tip60 to enhance transcriptional activity and is essential for β-catenin inhibition during cell differentiation [3]. The central transcriptional activation domain (TAM) functions synergistically with TAC to augment SOX9's transcriptional potential. Ahead of the HMG box lies the dimerization domain (DIM), while the PQA-rich domain is necessary for transcriptional activation [3]. This modular structure allows SOX9 to integrate into multiple signaling networks and regulate diverse target genes involved in immune cell function and communication within the TME.

SOX9-Mediated Mechanisms of Immune Evasion

Suppression of Anti-Tumor Immune Cell Infiltration

SOX9 orchestrates a comprehensive immunosuppressive program within the TME by limiting the infiltration and function of cytotoxic immune cells. In KrasG12D-driven lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) models, SOX9 expression significantly suppresses the recruitment of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and dendritic cells [30]. This exclusion of effector immune cells creates an "immune desert" microenvironment that facilitates tumor immune escape. The mechanisms underlying this exclusion involve SOX9-mediated elevation of collagen-related gene expression and substantial increases in collagen fibers, resulting in increased tumor stiffness that physically impedes immune cell infiltration [30]. Additionally, bioinformatics analyses of colorectal cancer data reveal that SOX9 expression negatively correlates with infiltration levels of B cells, resting mast cells, resting T cells, monocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils, while showing positive correlation with neutrophils, macrophages, activated mast cells, and naive/activated T cells [3]. These findings position SOX9 as a master regulator of the immune landscape across multiple cancer types.

Regulation of Immunosuppressive Cell Populations

Beyond excluding cytotoxic immune cells, SOX9 actively promotes the accumulation and function of immunosuppressive cell populations. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics analyses in prostate cancer patients demonstrate that SOX9 expression is associated with increased immunosuppressive cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs) and M2 macrophages (TAM Macro-2), while decreasing effector immune cells such as CD8+CXCR6+ T cells [3]. This imbalance establishes an immunosuppressive milieu conducive to tumor progression. In liver cancer, SOX18 (a SOX family member related to SOX9) promotes the accumulation of Tregs and immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) by transactivating PD-L1 and CXCL12 [31]. Similarly, SOX12 increases intratumoral Treg infiltration and decreases CD8+ T-cell infiltration in liver cancer [31]. These findings across the SOX family highlight a conserved mechanism whereby SOX transcription factors shape the immunosuppressive landscape of the TME.

Metabolic Reprogramming of the Immune Microenvironment

Emerging evidence indicates that SOX9 drives immunometabolic reprogramming that sustains the immunosuppressive TME. In neuropathic pain models, which share features with cancer-associated inflammation, SOX9 transcriptionally regulates hexokinase 1 (Hk1), the enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting first step of glycolysis [7]. Nerve injury induces abnormal SOX9 phosphorylation, triggering aberrant Hk1 activation and high-rate astrocytic glycolysis [7]. The resulting excessive lactate production remodels histones of gene promoters via lactylation (H3K9la), promoting transcriptional modules of pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic genes while reducing beneficial cell populations [7]. This SOX9-Hk1-H3K9la axis represents a novel immunometabolic mechanism that may similarly operate in the TME to promote pathogenic cellular states and suppress anti-tumor immunity. The metabolic reprogramming driven by SOX9 creates a hostile environment for effector immune cells while supporting immunosuppressive populations that thrive in lactate-rich conditions.

Table 1: SO9-Mediated Effects on Immune Cell Populations in the Tumor Microenvironment

| Immune Cell Type | Effect of SOX9 | Mechanism | Cancer Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD8+ T cells | Suppresses infiltration and function | Increased collagen deposition and tumor stiffness; negative correlation with cytotoxic gene signatures | Lung adenocarcinoma, Colorectal cancer [3] [30] |

| Natural Killer (NK) cells | Suppresses infiltration | SOX9-driven physical barriers in TME; suppressed recruitment signals | Lung adenocarcinoma [30] |

| Dendritic cells | Suppresses infiltration and antigen presentation | Collagen-rich physical barriers; altered chemokine profiles | Lung adenocarcinoma [30] |

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | Promotes accumulation and function | Direct and indirect transcriptional regulation; potential PD-L1 transactivation | Prostate cancer, Liver cancer [3] [31] |

| M2 Macrophages | Promotes polarization and function | Complex cytokine and chemokine regulation; metabolic reprogramming | Prostate cancer, Multiple solid tumors [3] [31] |

| B cells | Suppresses infiltration | Altered chemotactic signals in TME | Colorectal cancer [3] |

SOX9 in Cancer Progression and Clinical Outcomes

Prognostic Significance Across Cancers

SOX9 overexpression is frequently associated with advanced disease stage and poor prognosis across multiple cancer types, reflecting its potent role in driving tumor progression and immune evasion. A meta-analysis of gastric cancer studies demonstrated that SOX9 expression significantly correlates with depth of invasion and advanced TNM stage [32]. Patients with high SOX9 expression exhibited significantly shorter 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival, establishing SOX9 as a potential prognostic biomarker [32]. In non-small cell lung cancer, patients with SOX9-high tumors show significantly shorter survival, while SOX9-low patients experience significantly longer survival [30]. Interrogation of The Cancer Genome Atlas data confirms this association, with SOX9 upregulation linked to poorer outcomes [30]. Interestingly, in glioblastoma, high SOX9 expression shows a complex relationship with prognosis, being remarkably associated with better prognosis in lymphoid invasion subgroups but serving as an independent prognostic factor for IDH-mutant cases [33]. These context-dependent associations highlight the tissue-specific functions of SOX9 and its integration with other molecular pathways in determining clinical outcomes.

Functional Role in Tumor Development

The functional importance of SOX9 in tumor development extends beyond correlation to direct causation. In KrasG12D-driven mouse lung adenocarcinoma models, loss of Sox9 significantly reduces lung tumor development, burden, and progression, contributing to significantly longer overall survival [30]. Sox9 knockout mice exhibited dramatically fewer high-grade tumors, with SOX9 being predominantly expressed in larger, proliferative, and high-grade tumors [30]. Similarly, in liver cancer models, deletion of the tumor suppressor Pten in SOX9+ cells induces their transformation, enabling them to give rise to mixed-lineage tumors manifesting features of both hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [34]. The tumorigenic potential of these transformed SOX9+ cells requires liver injury for activation, demonstrating how SOX9 interfaces with environmental cues to drive carcinogenesis [34]. These functional studies establish SOX9 not merely as a biomarker but as a bona fide driver of tumor development and progression across multiple cancer types.

Table 2: Clinical and Prognostic Significance of SOX9 in Human Cancers

| Cancer Type | Expression Pattern | Clinical Correlations | Prognostic Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric Cancer | Upregulated | Depth of invasion, TNM stage | Shorter 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival [32] |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | Upregulated | Tumor grade, proliferation index | Shorter overall survival [30] |

| Glioblastoma | Upregulated | IDH mutation status, lymphoid invasion | Better prognosis in lymphoid invasion subgroups; independent prognostic factor in IDH-mutant cases [33] |

| Colorectal Cancer | Upregulated | Altered immune cell infiltration patterns | Associated with immunosuppressive TME [3] |

| Liver Cancer | Upregulated | Advanced tumor stage, higher tumor grade | Poorer recurrence-free and overall survival [34] |

| Breast Cancer | Upregulated | Tumor initiation, progression, stemness | Associated with basal-like subtype and poor outcomes [11] |

Experimental Models and Methodologies

In Vivo Cancer Models

Studies elucidating SOX9's role in immune regulation have employed sophisticated genetically engineered mouse models that enable precise manipulation of Sox9 expression in specific cellular contexts. The KrasLSL-G12D; Sox9flox/flox (KSf/f) model utilizes Cre-LoxP technology to achieve Sox9 knockout specifically in KrasG12D-driven tumor cells [30]. This approach demonstrates that Sox9 loss significantly reduces lung tumor burden and prolongs survival, with immunohistochemical analysis revealing decreased Ki67+ proliferating cells in SOX9- tumors [30]. Alternatively, the pSECC CRISPR-mediated genome editing system combines CRISPR and Cre recombinase to knockout Sox9 and activate KrasG12D simultaneously, confirming that Sox9 deletion decreases tumor number and burden while suppressing progression to high-grade tumors [30]. For lineage tracing studies, the PtenloxP/loxP; Sox9-CreERT+; R26RYFP model enables tamoxifen-inducible deletion of Pten in SOX9+ cells while labeling them with YFP [34]. This model revealed that transformed SOX9+ cells can give rise to mixed-lineage liver tumors, with all tumor cells expressing YFP, confirming their origin from SOX9+ cells [34]. These models provide powerful tools for dissecting SOX9's cell-autonomous and non-autonomous functions in tumor progression and immune modulation.

Immunological Assessment Techniques

Comprehensive immunological profiling in SOX9 studies employs multiple complementary techniques to characterize the immune microenvironment. Flow cytometry analysis of dissociated tumors enables quantification of immune cell populations, demonstrating SOX9-mediated suppression of CD8+ T cells, NK cells, and dendritic cells [30]. Gene expression analysis by RNA sequencing and RT-qPCR reveals SOX9-associated signatures related to collagen deposition, immune cell function, and metabolic pathways [3] [30]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) provides unprecedented resolution of cellular heterogeneity, as demonstrated in neuropathic pain models where scRNA-seq identified distinct astrocyte clusters and elucidated metabolic regulation of neuroinflammatory subsets [7]. Bioinformatic analysis of human cancer datasets, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas, enables correlation of SOX9 expression with immune signatures and patient outcomes [3] [32] [33]. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence validate protein expression and localization, showing co-expression of hepatocyte and cholangiocyte markers in SOX9-derived liver tumors [34]. These multidisciplinary approaches collectively provide a comprehensive understanding of how SOX9 shapes the immunological landscape of tumors.

Diagram 1: SOX9 Mechanisms in Immune Evasion: This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which SOX9 orchestrates tumor immune evasion, including direct immune suppression, metabolic reprogramming, creation of physical barriers, and promotion of pro-tumor inflammation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating SOX9 in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Features | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sox9-floxed mice (Sox9flox/flox) | Conditional Sox9 knockout | Enables cell-type specific Sox9 deletion; compatible with Cre drivers | Studying Sox9 loss-of-function in specific cell populations [30] [34] |

| Sox9-CreERT+ mice | Inducible genetic targeting | Tamoxifen-inducible Cre expression in SOX9+ cells; enables lineage tracing | Fate mapping of SOX9+ cells and their progeny [34] |

| pSECC CRISPR system | In vivo genome editing | Combines CRISPR-mediated gene knockout with Cre-dependent oncogene activation | Simultaneous Sox9 knockout and KrasG12D activation in lung models [30] |

| R26RYFP reporter | Lineage tracing | Cre-dependent YFP expression; permanent labeling of targeted cells | Tracking SOX9+ cell fate in liver carcinogenesis [34] |

| Anti-SOX9 antibodies | IHC, IF, Western blot | Detection of SOX9 protein expression and localization | Assessing SOX9 expression in tumor tissues [30] [32] |

| scRNA-seq platforms | Cellular heterogeneity analysis | High-resolution transcriptomic profiling of individual cells | Identifying SOX9-associated cell clusters in TME [7] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

SOX9 as a Therapeutic Target

The compelling evidence for SOX9's role in driving immune evasion positions it as an attractive therapeutic target for cancer treatment. Several strategies emerge for targeting SOX9 therapeutically. Small molecule inhibitors that disrupt SOX9's transcriptional activity or its interactions with cofactors could potentially reverse its immunosuppressive programming [3]. Alternatively, targeting downstream effectors of SOX9, such as the SOX9-Hk1-H3K9la axis identified in neuropathic pain models, may provide more specific approaches to modulate SOX9 function without completely abrogating its physiological roles [7]. Given SOX9's role in promoting tumor stiffness and collagen deposition, combining SOX9-targeted approaches with anti-fibrotic agents may enhance immune cell infiltration and improve response to immunotherapy [30]. Additionally, the context-dependent functions of SOX9 suggest that patient stratification based on SOX9 expression patterns or activity signatures will be essential for developing effective SOX9-directed therapies. The dual nature of SOX9 in immunity necessitates careful therapeutic modulation rather than complete inhibition to avoid compromising its beneficial roles in tissue homeostasis and repair [3].

Integration with Immunotherapy

The immunosuppressive functions of SOX9 suggest that its inhibition could synergize with existing immunotherapies, particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors. SOX9-mediated suppression of CD8+ T cell and NK cell infiltration likely contributes to resistance against anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies [30]. Preclinical models demonstrate that SOX9 promotes an "immune desert" phenotype characterized by exclusion of cytotoxic immune cells, which is associated with poor response to checkpoint blockade [3] [30]. Therefore, combining SOX9 inhibition with immune checkpoint blockade may convert immune-excluded tumors into immune-inflamed ones, potentially expanding the proportion of patients who benefit from immunotherapy. Furthermore, the correlation between SOX9 expression and immune checkpoint molecules like PD-L1 in some cancer contexts suggests interconnected regulatory networks [31] [33]. Future studies should explore whether SOX9 directly regulates checkpoint molecule expression and whether SOX9 inhibition can enhance the efficacy of adoptive cell therapies, such as CAR-T cells, by improving their trafficking and persistence within tumors.

Diagram 2: SOX9-HK1 Immunometabolic Axis: This diagram outlines the SOX9-HK1 immunometabolic axis identified in neuropathic pain, demonstrating how SOX9 activation drives glycolytic reprogramming and epigenetic changes via lactate production, potentially mirroring mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment.

SOX9 emerges as a master orchestrator of the tumor immune microenvironment, integrating transcriptional control, metabolic reprogramming, and extracellular matrix remodeling to create an immunosuppressive niche that facilitates tumor progression. Its dual functions in immune regulation—promoting immunosuppressive cell populations while excluding cytotoxic effector cells—highlight its potential as both a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target. The experimental models and methodologies reviewed provide robust tools for further dissecting SOX9's complex roles in cancer-immune interactions. As research continues to unravel the context-dependent functions of SOX9 across different cancer types and its integration with autoimmune and inflammatory pathways, targeting this multifaceted transcription factor may offer novel opportunities to overcome resistance to current immunotherapies and improve patient outcomes across multiple cancer types.

Targeting SOX9: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Interventions

Gene therapy represents a transformative frontier for treating autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, aiming to address the underlying pathological mechanisms rather than merely alleviating symptoms. Within this landscape, adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated gene delivery has emerged as a promising vehicle for sustained therapeutic gene expression. This technical guide focuses on the coordinated delivery of two potent biological agents: Sex-determining region Y-box 9 (SOX9), a transcription factor critical for tissue homeostasis and repair, and Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1Ra), a natural inhibitor of the key pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1. The synergistic potential of SOX9 and IL-1Ra is particularly compelling within the context of chronic inflammatory diseases such as osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, where inflammation and tissue destruction are intertwined. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the therapeutic rationale, experimental evidence, technical protocols, and clinical translation of AAV vectors engineered to co-deliver SOX9 and IL-1Ra, framed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Therapeutic Rationale and Biological Mechanisms

The IL-1 Pathway and Rationale for IL-1Ra Gene Therapy

The interleukin-1 (IL-1) signaling pathway is a master regulator of inflammation and innate immunity. Its dysregulation is a pathogenic cornerstone of numerous chronic inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and osteoarthritis (OA) [35] [36]. IL-1α and IL-1β, the two primary agonists, initiate a potent pro-inflammatory cascade upon binding to the IL-1 receptor type 1 (IL-1R1). This triggers the recruitment of the myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) adapter protein, leading to the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways, and ultimately the production of cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF), chemokines, and destructive enzymes [36].

The body's natural counterbalance to this pathway is the Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist (IL-1Ra), a secreted protein that competes with IL-1α and IL-1β for binding to IL-1R1 without initiating signal transduction. In many chronic inflammatory diseases, the balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra is skewed towards inflammation. Traditional protein-based therapies with recombinant IL-1Ra (e.g., anakinra) are limited by short half-lives, necessitating frequent injections and failing to maintain effective joint concentrations [37]. AAV-mediated gene therapy surmounts this hurdle by enabling long-term, local production of IL-1Ra within the joint, thereby re-establishing the physiological anti-inflammatory balance [38] [35].

SOX9: A Master Regulator of Homeostasis and Repair

SOX9 is a transcription factor belonging to the SRY-related high-mobility group (HMG)-box family. It is a critical specifier and regulator in multiple biological processes, including chondrogenesis, glial cell function, and male sex determination [7] [39] [40]. Its role in maintaining tissue homeostasis and mitigating inflammatory responses is of particular therapeutic interest.

In the context of inflammatory joint disease, SOX9 is essential for chondrocyte health and cartilage matrix synthesis. It directly regulates the expression of key cartilage-specific extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as type II collagen (COL2A1) and aggrecan. Furthermore, evidence suggests SOX9 exerts anti-inflammatory effects. Inhibition of SOX9 in dental pulp cells was shown to promote a pro-inflammatory state, increasing production of IL-8 and enhancing matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity, which leads to ECM degradation [14]. Conversely, boosting SOX9 in astrocytes promotes a protective phenotype, enhancing their phagocytic capacity to clear amyloid-β plaques in Alzheimer's disease models [13]. In neuropathic pain, aberrant SOX9 phosphorylation drives a metabolic shift towards glycolysis in a deleterious astrocyte subset, fueling neuroinflammation [7]. Thus, SOX9's function is highly context-dependent, but its targeted delivery can promote an anti-inflammatory, pro-regenerative state.

Table 1: Key Biological Functions of SOX9 and IL-1Ra

| Therapeutic Agent | Primary Function | Role in Inflammatory Disease | Consequence of Deficiency/Dysregulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1Ra | Natural antagonist of IL-1R1 | Blocks IL-1-driven inflammation and tissue destruction | Unchecked IL-1 signaling; chronic inflammation; cartilage degradation [35] [36] |

| SOX9 | Transcription factor; master regulator of cartilage and glial function | Promotes cartilage matrix synthesis; maintains tissue homeostasis; can inhibit inflammatory responses | Reduced matrix synthesis; increased MMP activity; emergence of pathogenic cell states [38] [14] [7] |

Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

Efficacy of Co-delivery in Osteoarthritis Models

Recent preclinical studies provide compelling evidence for the superior efficacy of co-delivering SOX9 and IL-1Ra compared to either treatment alone. A 2025 study investigated this combination in surgically induced osteoarthritis animal models (rats and rabbits) using a single-stranded AAV (scAAV) vector [38].

Key findings from this study are summarized in the table below:

Table 2: Summary of Efficacy Outcomes from AAV-Mediated SOX9 and IL-1Ra Co-delivery in Preclinical OA Models [38]

| Model System | Treatment | Key Efficacy Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| MMT/ACLT-induced KOA (Rat) | scAAV-oIL-1Ra | Improved gait (increased footprint area & pressure); reduced subchondral bone lesions; significantly reduced cartilage wear and pathological scores. |

| MMT-induced KOA (Rabbit) | scAAV-oIL-1Ra | Improved weight-bearing symmetry (indicating pain relief) after 8 weeks; decreased Kellgren-Lawrence (K-L) scores on X-ray; reduced cartilage loss and pathology scores. |

| ACLT+MMT-induced KOA (Rat) | scAAV-oIL-1Ra + SOX9 | Significantly alleviated subchondral bone lesions, cartilage destruction, and synovial inflammation. Demonstrated superior efficacy versus single treatments. |

The study concluded that the combination therapy not only inhibited IL-1-mediated inflammatory signaling but also promoted cartilage homeostasis and repair, suggesting strong clinical potential [38].

Advanced IL-1Ra Gene Therapy Constructs

Innovations in vector design are enhancing the safety and specificity of IL-1Ra therapy. One advanced approach involves the use of an inflammation-inducible promoter to control the expression of a secreted human IL-1Ra (sIL-1Ra). This system, delivered via a recombinant AAV (rAAV), is designed to mimic the body's natural feedback mechanism by "turning on" sIL-1Ra production specifically in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines and bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) enriched in inflamed joints [35].

In a mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis, this inducible sIL-1Ra was remarkably more effective than a constitutively expressed version in ameliorating inflammatory arthritis. Treated mice showed significant reductions in circulating immune cells, expression of inflammatory genes, joint swelling, and bone destruction. Furthermore, a single systemic administration of this rAAV-sIL-1Ra vector almost completely reversed spontaneous inflammatory arthritis and skeletal abnormalities in IL-1Ra-deficient mice, modeling the human DIRA syndrome [35]. This highlights the potential of pathophysiology-responsive gene regulation for treating chronic inflammatory diseases.

Clinical Trial Landscape

The translation of AAV-mediated gene therapy for joint disease is underway, though the clinical landscape is still nascent. Pacira BioSciences is advancing a notable candidate, PCRX-201 (enekinragene inzadenovec), an intra-articular gene therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee designed to boost local production of IL-1Ra [41].

PCRX-201 incorporates an inducible promoter and is based on a proprietary high-capacity adenovirus (HCAd) vector platform, which offers advantages over traditional AAV, including a larger transgene capacity and potential for re-dosing [41]. The ongoing two-part, multicenter Phase 2 ASCEND study is evaluating the safety and efficacy of PCRX-201. The company reported continued durable and clinically meaningful improvements in knee pain, stiffness, and function through three years post-administration, with a well-tolerated safety profile [41]. PCRX-201 has received Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation from the U.S. FDA, underscoring its potential.

Table 3: Overview of Selected Clinical Trials for Joint Disease Gene Therapy

| Therapeutic Candidate / Identifier | Vector / Gene | Indication | Sponsor | Key Design Features / Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCRX-201 (ASCEND study) | HCAd / IL-1Ra | Osteoarthritis of the Knee | Pacira BioSciences | Inflammation-inducible promoter; Phase 2 ongoing; RMAT designation [41]. |

| NCT02790723 | AAV2.5 / IL-1Ra | Knee Osteoarthritis | Mayo Clinic | Phase I/II trial assessing safety, tolerability, and effects on pain and function [37]. |

| ICM-203 (NCT05454566) | AAV5.2 / Nkx3.2 | Knee Osteoarthritis | ICM Co., Ltd. | Encodes a transcription factor involved in chondrocyte activity; interim results show mixed outcomes [37]. |

| NCT03445715 | AAV5 / sTNFR1 | Rheumatoid Arthritis (Wrist) | Arthrogen | Delivers soluble TNF receptor to block TNF-α; one of several trials for RA [37]. |

Technical and Methodological Guide

Experimental Protocol for Preclinical OA Model Validation

The following detailed methodology is adapted from the 2025 co-delivery study, providing a robust framework for validating AAV-SOX9/IL-1Ra efficacy [38].

1. Vector Construction and Preparation:

- Therapeutic Genes: Clone full-length cDNA for the species-specific IL-1Ra and SOX9 genes.

- Vector Backbone: Utilize a single-stranded AAV (scAAV) backbone (e.g., scAAV2) to enable rapid transgene expression. The use of a self-complementary genome is optional but enhances kinetics.

- Promoter Selection: Employ a strong, ubiquitous promoter such as CAG (hybrid CMV early enhancer/chicken β-actin) or a synthetic, inflammation-inducible promoter (e.g., based on NF-κB response elements) for context-specific expression [35].