SPR vs ITC: Choosing the Right Method for Protein-Small Molecule Binding Analysis

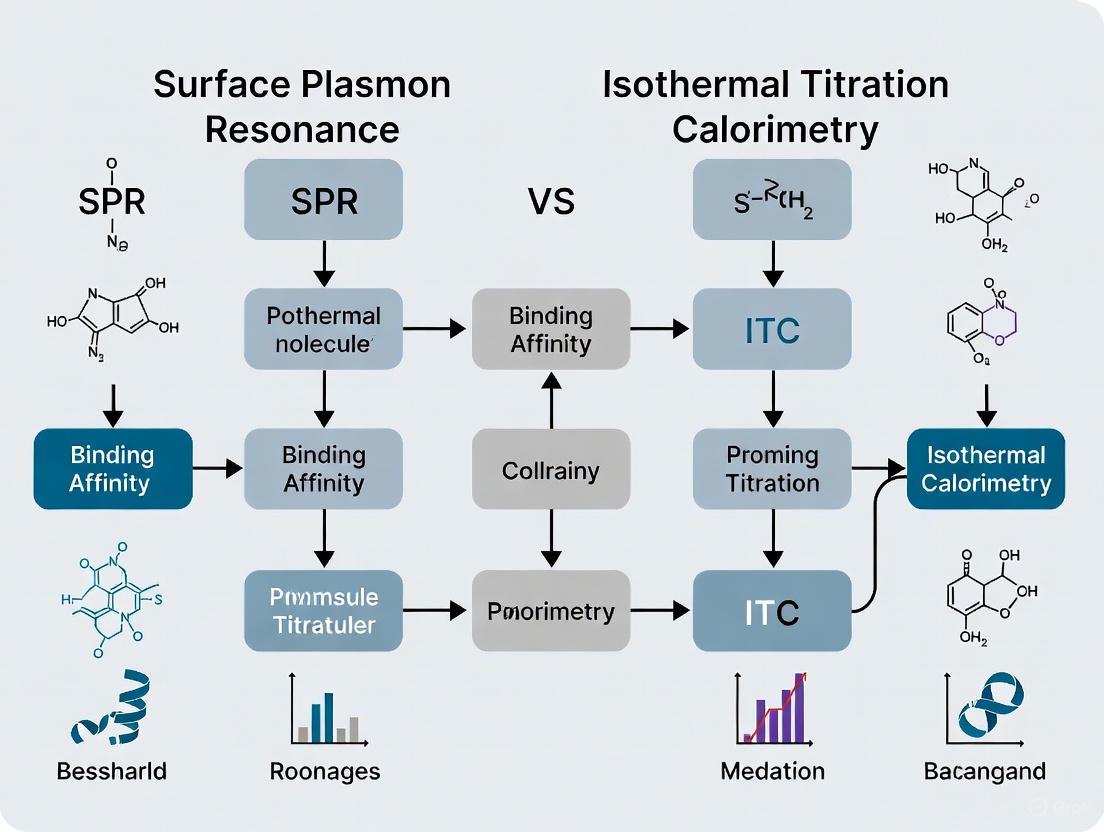

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for characterizing protein-small molecule interactions, a critical task in drug discovery and biophysical research.

SPR vs ITC: Choosing the Right Method for Protein-Small Molecule Binding Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for characterizing protein-small molecule interactions, a critical task in drug discovery and biophysical research. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of both techniques, detailed methodological protocols, common troubleshooting scenarios, and a direct comparative analysis. The guide synthesizes current information to help scientists select the optimal method based on their specific research goals, whether for obtaining kinetic profiles, complete thermodynamic data, or for fragment-based screening, thereby enabling more efficient and informed experimental design.

Understanding SPR and ITC: Core Principles and Measurable Parameters

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) are two powerful, label-free techniques central to characterizing biomolecular interactions in modern drug discovery and basic research [1] [2]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, with a focus on protein-small molecule binding affinity measurement.

Core Principles and Technical Comparison

The Fundamental Mechanism of SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is an optical technique that exploits the sensitivity of electron charge density waves at a metal-dielectric interface [1]. In practice, one binding partner (the ligand) is immobilized onto a sensor chip surface, typically coated with a thin gold film. The other partner (the analyte) is flowed over this surface in solution. The instrument then directs a beam of polarized light at the gold film; the light is reflected and its intensity is measured by a detector [1].

When biomolecules bind to the surface, they increase the local refractive index, which in turn alters the angle at which the minimum reflected light intensity (the resonance angle) occurs. The SPR instrument monitors this angle in real-time, producing a sensorgram where the y-axis is this resonance signal (in Resonance Units, RU) and the x-axis is time. This direct monitoring allows for the precise determination of association and dissociation rates, from which the binding affinity is calculated [1] [3].

Diagram Title: SPR Experimental Workflow and Signal Detection

The Fundamental Mechanism of ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a solution-based technique that directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a molecular binding event [2]. The instrument consists of two cells: a sample cell containing one binding partner and a reference cell containing just buffer. The second binding partner is loaded into a syringe and then injected into the sample cell in a series of small aliquots.

Each binding event produces a heat pulse (exothermic or endothermic), which is measured to maintain a constant temperature between the sample and reference cells. The raw data is a plot of power (µcal/sec) versus time. Integrating these heat peaks for each injection produces a binding isotherm, which is fitted to a model to directly determine the binding affinity, stoichiometry, and thermodynamic parameters like enthalpy and entropy [1] [4].

Diagram Title: ITC Experimental Workflow and Signal Detection

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Direct comparison of SPR and ITC for analyzing molecular interactions.

| Performance Factor | Surface Plasmon Resonance | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Optical; refractive index change [1] | Calorimetric; heat change [2] |

| Primary Data Output | Real-time kinetics (kon, koff) [1] [3] | Thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS, n) [2] [4] |

| Affinity Range | pM - mM [1] | µM - low nM [2] |

| Sample Consumption | Low volumes (25-100 µL/injection), wide concentration range [2] | Large amounts required (300-500 µL at 10-100 µM) [2] |

| Throughput | High [1] | Low (0.25 - 2 hours/assay) [4] |

| Immobilization Required | Yes (one binding partner) [1] | No (both partners in solution) [2] |

| Key Advantage | Real-time kinetic profiling and high sensitivity [5] [2] | Complete thermodynamic profile in one experiment [1] [2] |

| Main Limitation | Requires immobilization; complex data analysis [2] | High sample consumption; lower sensitivity for weak binders [2] [4] |

Table 2: Suitability for different research applications.

| Research Application | Recommended Technique | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment-Based Drug Discovery | SPR | Superior sensitivity for detecting weak, low-affinity binders [2]. |

| Lead Optimization (Kinetics) | SPR | Provides crucial association/dissociation rates (kon, koff) to guide drug design [1] [5]. |

| Mechanistic Studies | ITC | Directly measures enthalpy and entropy, revealing driving forces behind binding [2]. |

| Stoichiometry Determination | ITC | Directly provides the number of binding sites in a single experiment [2] [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Protein-Small Molecule Analysis

SPR Experimental Protocol for Kinetic Analysis

This protocol outlines the key steps for characterizing the binding kinetics of a small molecule inhibitor to its protein target using SPR [1].

- Sensor Chip Preparation: Select an appropriate sensor chip. The protein target is immobilized onto the chip surface using standard coupling chemistry.

- System Equilibration: The SPR instrument is primed and the running buffer is flowed continuously over the sensor chip until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Analyte Binding Phase: A concentration series of the small molecule analyte is prepared and flowed over the protein-immobilized surface for a set time (association phase).

- Dissociation Phase: The flow is switched to running buffer without analyte to monitor the dissociation of the bound complex.

- Surface Regeneration: A regeneration solution is injected to remove any remaining bound analyte, restoring the surface for the next cycle.

- Data Analysis: The resulting sensorgrams for all analyte concentrations are globally fitted to a suitable binding model to determine the kinetic rate constants and affinity.

ITC Experimental Protocol for Thermodynamic Profiling

This protocol describes how to obtain a full thermodynamic profile of a protein-small molecule interaction using ITC [2].

- Sample Preparation: Both the protein and small molecule ligand are dialyzed into an identical, degassed buffer to prevent signal artifacts from mismatched buffers.

- Loading: The sample cell is filled with the protein solution. The syringe is loaded with the small molecule ligand at a concentration typically 10-20 times higher than that in the cell.

- Titration Experiment: The instrument is set to a constant temperature. The ligand is automatically titrated into the protein cell in a series of injections.

- Data Collection: The instrument records the heat required to maintain a constant temperature difference after each injection.

- Data Analysis: The integrated heat data is fitted to a binding model to determine the binding constant, enthalpy change, entropy change, and stoichiometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key reagents and materials required for SPR and ITC experiments.

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Sensor Chips | Provides the gold surface for ligand immobilization [1]. | Available with various functional groups for different chemistries [3]. |

| Immobilization Reagents | Chemicals used to covalently attach the ligand to the sensor chip. | Includes coupling agents for amine, thiol, or His-tag capture [1]. |

| Running Buffer | The solution in which analyte is dissolved and flowed over the chip surface. | Must be optimized for protein stability and to minimize non-specific binding. |

| Regeneration Solution | A solution that removes bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand [3]. | Critical for reusing sensor chips; condition must be empirically determined. |

| High-Purity Protein & Ligand | The interacting molecules under investigation. | ITC requires highly purified samples at relatively high concentrations [2]. |

| Matchable Buffer | The solvent for both binding partners in ITC. | Protein and ligand must be in identical buffer to prevent heat of dilution artifacts [2]. |

In the field of drug discovery and biomolecular research, understanding the interactions between proteins and small molecules is fundamental to developing effective therapeutics. Two principal techniques have emerged as cornerstone methods for characterizing these interactions: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). While both provide critical information about binding events, they differ fundamentally in what they measure and the type of information they yield. ITC directly quantifies the heat changes associated with binding interactions, providing a complete thermodynamic profile of the molecular interaction. In contrast, SPR measures changes in refractive index near a sensor surface to monitor binding events in real-time, offering detailed kinetic information. This guide objectively compares these techniques, with particular emphasis on the unique principles and applications of ITC for studying protein-small molecule interactions.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of ITC and SPR Principles

| Characteristic | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Parameter | Heat change (μcalories) | Refractive index change (Resonance Units) |

| Primary Output | Thermodynamic profile | Kinetic parameters |

| Measurement Environment | Free solution | Solid-liquid interface |

| Molecular Modification | Label-free, no immobilization required | One binding partner requires immobilization |

| Key Measurables | KD, ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, n (stoichiometry) | KD, kon, koff |

The Fundamental Principle of Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Direct Measurement of Binding Heat

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry operates on a fundamentally straightforward principle: it directly measures the heat released or absorbed when two molecules interact at a constant temperature. The instrument consists of two identical cells—a sample cell containing the macromolecule (e.g., a protein) and a reference cell filled with buffer or solvent—both maintained at precisely the same constant temperature. The ligand (typically a small molecule drug candidate) is titrated into the sample cell in a series of controlled injections, while the reference cell receives no injections. When the ligand binds to the macromolecule in the sample cell, heat is either generated (exothermic reaction) or absorbed (endothermic reaction). The instrument continuously measures the tiny power differential (μcalories/second) required to maintain both cells at the identical temperature, providing a direct readout of the binding event's thermal signature [6].

The resulting thermogram displays peaks corresponding to each injection, with the area under each peak representing the total heat change for that binding event. As the binding sites become saturated with successive injections, the heat signal diminishes until only background dilution heat remains. Analysis of this titration curve reveals the complete thermodynamic profile of the interaction, including the binding constant (KD), enthalpy change (ΔH), entropy change (ΔS), and stoichiometry (n) of the complex. The thermodynamic relationships are calculated using the following fundamental equations [6]:

- ΔG = -RTln(Ka)

- ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

where Ka is the association constant (1/KD), R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature.

ITC Instrument Response and Kinetic Modeling

The ITC thermogram with its characteristic asymmetric gaussian-like peaks can be analyzed beyond traditional thermodynamic parameters. Advanced modeling approaches integrate the instrument response with the binding mechanism within a unified kinetic framework. The time-domain data (thermogram without peak integration) can be directly analyzed to obtain kinetic rate constants, incorporating first-order instrument responses for both ligand dilution and heat detection [7].

The dynamic approach models several key processes simultaneously: (1) the kinetics of ligand dilution from the injection site into the bulk solution; (2) the binding mechanism between available ligand and protein; and (3) the instrument response related to the time delay between heat generation and detection. This comprehensive modeling enables researchers to extract both thermodynamic and kinetic information from a single ITC experiment, significantly expanding the technique's capability beyond conventional applications [7].

Diagram 1: ITC Experimental Workflow showing the key stages from sample preparation through data analysis.

Comparative Analysis: ITC vs. SPR for Protein-Small Molecule Interactions

Information Content and Data Output

ITC and SPR provide complementary but fundamentally different information about molecular interactions. ITC excels at delivering a complete thermodynamic profile, revealing the driving forces behind binding events, while SPR specializes in real-time kinetic monitoring, providing insights into binding mechanism and residence times.

Table 2: Comprehensive Technique Comparison for Protein-Small Molecule Studies

| Parameter | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity (KD) | Yes (nM - μM range) [1] | Yes (pM - mM range) [4] [1] |

| Kinetic Constants (kon/koff) | Limited capability [7] | Yes, primary strength [2] |

| Thermodynamic Parameters | Complete profile (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) [1] [6] | Limited thermodynamic information [1] |

| Stoichiometry (n) | Direct measurement [1] [6] | Possible but less direct |

| Throughput | Low (0.25-2 hours/assay) [4] | Moderate to high [4] [8] |

| Immobilization Required | No [2] [1] | Yes [4] [2] |

| Labeling Required | No [2] [6] | No [4] [2] |

| Sample Consumption | High (large quantities of purified protein) [2] | Low (small sample volumes) [4] [2] |

| Solvent Compatibility | Narrow (sensitive to buffer mismatch) [1] | Broad (crude samples compatible) [4] |

Experimental Design and Practical Considerations

The practical implementation of ITC and SPR differs significantly, impacting their suitability for specific research scenarios. ITC experiments require careful buffer matching to minimize dilution heats, with typical protein concentrations in the range of 10-100 μM in the sample cell [6]. The ligand in the syringe is typically at concentrations 10-20 times higher than the protein to ensure complete saturation during the titration. A complete ITC experiment typically takes 30 minutes to several hours, with slower injections providing better data quality for weak interactions [2].

SPR experimental design focuses instead on optimal immobilization strategies to maintain binding partner activity while minimizing non-specific binding. One binding partner is immobilized on a sensor chip surface, while the other flows across in solution. Regeneration conditions must be optimized to remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand. SPR offers higher throughput with shorter cycle times, making it more suitable for screening applications [4] [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed ITC Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Interactions

Sample Preparation:

- Protein and ligand must be in identical buffer conditions to prevent heat of dilution artifacts

- Typical sample cell volume: 200-300 μL with protein concentration 10-100 μM [6]

- Syringe concentration: 10-20 times higher than protein concentration (100-2000 μM)

- Careful degassing of all solutions to prevent bubble formation during injections

Instrument Setup:

- Temperature set to biologically relevant condition (typically 25-37°C)

- Reference cell filled with matched buffer

- Stirring speed set for efficient mixing (typically 750-1000 rpm)

- Injection parameters: 10-25 injections of 1-3 μL with 120-300 second intervals between injections

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Baseline stability established before first injection

- Power differential measured throughout titration

- Raw thermogram integrated to obtain heat per injection

- Data fitted to appropriate binding model (single site, multiple sites, sequential, etc.)

- Nonlinear regression provides KD, ΔH, n values

- ΔG and ΔS calculated using fundamental equations [7] [6]

Case Study: Comparative Analysis of Xylanase Binding

A direct comparison of ITC and SPR for studying substrate binding to Bacillus subtilis xylanase demonstrated the complementary nature of both techniques. Researchers investigated binding to the active site and secondary binding site separately using enzyme variants. Both ITC and SPR yielded similar Kd values (approximately 0.5-1.5 mM range) for xylohexaose binding, validating both methods for quantitative affinity measurements [9].

The ITC experiments provided thermodynamic parameters (ΔH = -6.5 kcal mol⁻¹ and TΔS = -2.5 kcal mol⁻¹) for active site binding, revealing the enthalpically driven nature of the interaction. SPR experiments additionally enabled characterization of the secondary binding site when the active site was blocked with a covalent inhibitor. However, both association and dissociation processes for this low-affinity oligosaccharide binding were too fast for reliable kinetic determination by SPR, highlighting the importance of selecting the appropriate technique based on the expected binding kinetics [9].

Diagram 2: ITC Thermodynamic Relationships showing the fundamental equations and their interpretation for binding interactions.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of ITC and SPR experiments requires specific reagents and materials optimized for each technique. The following table outlines essential components for both methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Binding Studies

| Item | Function/Purpose | ITC-Specific Considerations | SPR-Specific Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Proteins | Binding partner in native conformation | High concentration (mg/mL) required [2] | Lower concentration sufficient; activity critical after immobilization [4] |

| Ultra-Pure Ligands | Small molecule binding partners | Must be soluble at high concentrations | Mass transport limitations for very high affinity binders |

| Matched Buffer Systems | Control experimental conditions | Critical to minimize dilution heats [6] | Must be compatible with sensor surface chemistry |

| ITC Instrument Cells | Contain reaction mixture | Meticulous cleaning to prevent carryover [6] | Not applicable |

| SPR Sensor Chips | Immobilization surface | Not applicable | Various chemistries (CM5, NTA, SA) for different immobilization strategies [2] |

| Regeneration Solutions | Surface regeneration | Not applicable | Must remove bound analyte without damaging immobilized ligand [2] |

| Reference Compounds | System suitability testing | Well-characterized binding pairs for validation | Same as ITC |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Research

Strategic Implementation in Pharmaceutical Development

In drug discovery pipelines, ITC and SPR serve complementary roles that often make them most valuable when used in combination. SPR excels in early-stage high-throughput screening of compound libraries against therapeutic targets due to its lower sample consumption and higher throughput capabilities [2]. Once promising hits are identified, ITC provides comprehensive thermodynamic characterization during lead optimization, helping medicinal chemists understand the structural features driving binding interactions [6].

The thermodynamic profile obtained from ITC is particularly valuable for understanding the balance between enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) contributions to binding. Enthalpy-driven interactions typically indicate strong specific interactions like hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces, while entropy-driven binding often reflects hydrophobic effects and desolvation. This information guides chemical modifications to improve drug specificity and reduce off-target effects [6]. Additionally, ITC's ability to determine binding stoichiometry (n) provides critical insights into dosing and mechanism of action, particularly for allosteric modulators or multi-site binding drugs [6].

Regulatory Considerations and Method Validation

SPR has gained broader acceptance in regulatory submissions for biotherapeutic characterization, with FDA and EMA guidelines specifically referencing binding assays for quantifying functional activity of monoclonal antibodies and biosimilars [8]. However, ITC data provides complementary thermodynamic evidence that supports mechanism of action claims and helps elucidate unexpected binding behavior.

Both techniques require rigorous method validation including demonstration of specificity, accuracy, precision, and robustness. For ITC, this includes validation of concentration determinations, confirmation of buffer matching, and demonstration of binding model appropriateness. SPR validation includes surface stability assessments, regeneration reproducibility, and reference surface correction [8].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry remains an indispensable technique for complete thermodynamic characterization of protein-small molecule interactions, providing unique insights into the fundamental driving forces behind binding events. While SPR offers advantages in throughput, sensitivity, and kinetic analysis, ITC's label-free solution-based approach without requiring immobilization provides a more native environment for studying molecular interactions. The direct measurement of binding heat yields a comprehensive thermodynamic profile that is unmatched by other techniques. In modern drug discovery and basic research, the strategic combination of both ITC and SPR often provides the most powerful approach, with SPR enabling rapid screening and kinetic characterization, and ITC delivering deep thermodynamic understanding for lead optimization and mechanism of action studies.

In the field of protein-small molecule interaction research, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) are two pivotal techniques for binding characterization. While ITC provides a complete thermodynamic profile, including binding affinity, enthalpy, and entropy, SPR stands out by offering real-time kinetic data, revealing not just the strength of an interaction but its speed and dynamics [1] [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), and the resulting binding affinity (K_D) is crucial for applications ranging from lead optimization to anticipating a drug's duration of action in the body. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, detailing what SPR measures and how it complements other methods.

Core Measurements: The Kinetic Parameters of SPR

SPR is a label-free technology that detects molecular interactions in real-time by measuring changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface [4] [10]. This allows it to directly monitor the entire binding event as it happens.

The key parameters measured by SPR are:

- Association Rate Constant (kon): This parameter measures how quickly a protein and small molecule form a complex. A higher kon indicates a faster binding event.

- Dissociation Rate Constant (koff): This parameter measures how quickly the complex breaks apart, with a lower koff indicating a more stable complex that remains bound for longer.

- Binding Affinity (KD): The equilibrium dissociation constant is a ratio of the kinetic rate constants (KD = koff / kon). A lower KD value signifies a tighter interaction. While KD can be measured directly at equilibrium by other techniques, SPR uniquely derives it from the independent kinetic rates [4] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the SPR sensorgram and the kinetic parameters it provides.

SPR vs. ITC: A Technical Comparison

The choice between SPR and ITC often depends on the specific data required. The table below summarizes their core capabilities.

Table 1: Core Capabilities of SPR versus ITC

| Feature | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity (K_D) | Yes [10] [1] | Yes [1] [6] |

| Kinetics (kon, koff) | Yes (direct measurement) [4] [1] | No (kinetics are not its primary function) [4] [1] |

| Thermodynamics | Limited (Only ΔG via K_D) [1] | Yes (full profile: ΔG, ΔH, TΔS) [1] [6] |

| Stoichiometry (n) | No | Yes [1] [6] |

| Immobilization Required | Yes [4] [1] | No [4] [6] |

| Sample Consumption | Low [4] [10] | High [4] [1] |

| Throughput | High [4] [1] | Low [4] [1] |

| Affinity Range | pM - mM [1] [8] | nM - μM [1] |

Key Differentiators in Practice

- Kinetic Profiling: SPR's unique advantage is its ability to independently measure kon and koff. Two protein-small molecule interactions can have the same KD but vastly different kinetic profiles. For instance, a drug candidate with a slow koff (long residence time) can often correlate with better efficacy in vivo [11].

- Thermodynamic Profiling: ITC's strength lies in its direct measurement of enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS), helping researchers understand the driving forces behind a binding event (e.g., hydrogen bonding vs. hydrophobic interactions) [6].

- Experimental Workflow: SPR requires one binding partner to be immobilized on a sensor chip [4] [1], while ITC measures interactions freely in solution, which can be an advantage for some systems [6].

Experimental Protocols: Measuring Kinetics with SPR

Detailed SPR Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction

The following workflow is adapted from a recent study characterizing synthetic cannabinoid binding to the CB1 receptor [10].

Ligand Immobilization:

- A CM5 sensor chip is activated with a mixture of N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS).

- The CB1 receptor protein (the "ligand" in this setup) is diluted in a suitable sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and injected over the activated chip surface, resulting in covalent coupling via amine groups.

- Remaining reactive groups are "capped" by injecting ethanolamine hydrochloride. In the referenced study, a final immobilization level of approximately 2500 Response Units (RU) was achieved [10].

Sample Binding and Detection:

- The small molecule analytes (e.g., synthetic cannabinoids) are prepared in a series of concentrations in running buffer (e.g., HBS-EP).

- The analytes are flowed over the chip surface one by one. The binding and dissociation are monitored in real-time, generating a sensorgram for each concentration.

Data Analysis:

- The resulting sensorgrams, which plot RU against time, are processed using dedicated software (e.g., Biacore T200 Evaluation Software).

- The data is fit to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding). The software calculates the kon and koff for each concentration and then determines the K_D from the ratio of these rates [10].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for an SPR Experiment

| Reagent / Solution | Function |

|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A gold surface with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix that enables covalent immobilization of proteins [10]. |

| EDC / NHS Mixture | Cross-linking reagents that activate carboxyl groups on the chip surface for ligand coupling [10]. |

| Ethanolamine HCl | A blocking agent that deactivates any remaining activated ester groups on the chip surface after ligand immobilization [10]. |

| HBS-EP Buffer | A common running buffer (HEPES, NaCl, EDTA, Polysorbate 20) that maintains pH and ionic strength, and reduces non-specific binding. |

Comparative Experimental Data: SPR in Action

To illustrate the output of an SPR experiment, the following table summarizes affinity data for a set of synthetic cannabinoids binding to the CB1 receptor, demonstrating SPR's ability to differentiate between structurally similar small molecules [10].

Table 3: Experimental SPR Binding Affinities (K_D) of Synthetic Cannabinoids [10]

| Classification | Substance | K_D Value (M) |

|---|---|---|

| Indole-based | JWH-018 | 4.346 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Indole-based | AMB-4en-PICA | 3.295 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Indole-based | MAM-2201 | 2.293 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Indole-based | FDU-PB-22 | 1.844 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Indazole-based | 5F-MDMB-PINACA | 1.502 × 10⁻⁵ |

| Indazole-based | AB-CHMINACA | 7.641 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Indazole-based | MDMB-4en-PINACA | 5.786 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Indazole-based | FUB-AKB-48 | 1.571 × 10⁻⁶ |

This data highlights how SPR can rank compound affinity and reveal structure-activity relationships, such as the generally higher affinity of indazole-based compounds compared to indole-based ones [10].

SPR and ITC are not mutually exclusive but are powerful complementary techniques. For researchers focused primarily on the thermodynamic driving forces and stoichiometry of a binding event, ITC is the unmatched gold standard [6]. However, when the research question demands an understanding of the kinetics of the interaction—how fast a drug binds and how long it stays on its target—SPR is the definitive tool. Its ability to provide real-time, label-free data on kon and koff makes it indispensable in drug discovery and basic research for characterizing protein-small molecule interactions with high precision and insight.

In the field of drug discovery and biochemical research, understanding the precise nature of molecular interactions is paramount. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) have emerged as two powerful, label-free techniques for characterizing these interactions, yet they provide distinct and complementary information. While SPR excels at determining the kinetics of binding events, ITC provides a complete thermodynamic profile of molecular interactions in a single experiment. This guide offers an objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their application in protein-small molecule binding affinity research, to help scientists select the optimal technique for their specific investigational needs.

Understanding the Core Measurements of ITC

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a quantitative technique that directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event. By monitoring these heat changes at constant temperature, researchers can obtain a complete thermodynamic profile of an interaction without requiring labeling or immobilization [1] [12].

The fundamental parameters obtained from an ITC experiment include:

- Binding Affinity (KA or KD): The equilibrium association (KA) or dissociation (KD) constant, which quantifies the strength of the interaction [12] [13].

- Stoichiometry (n): The number of binding sites between the interacting molecules [12] [14].

- Enthalpy (ΔH): The direct heat change measured during binding, representing the net energy from bond formation/breakage [12].

- Entropy (ΔS): The indirect contribution to binding derived from the relationship ΔG = ΔH - TΔS, reflecting changes in solvation and molecular disorder [12].

These parameters are interrelated through the fundamental equation ΔG = -RTlnK_A = ΔH - TΔS, where ΔG represents the overall free energy change, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute temperature [12].

ITC vs. SPR: A Technical Comparison

The following table summarizes the core capabilities of ITC and SPR, highlighting their distinct strengths in characterizing biomolecular interactions:

| Parameter | ITC | SPR |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity (K_D) | Yes [1] | Yes [1] |

| Kinetic Information (kon, koff) | No (with exceptions of kinITC) [1] | Yes [1] [4] |

| Thermodynamic Information | Complete (ΔH, ΔS) [1] | Limited [1] |

| Stoichiometry (n) | Yes [1] [12] | No |

| Affinity Range | nM - μM [1] | pM - mM [1] |

| Label-Free | Yes [1] [4] | Yes [1] [4] |

| Immobilization Requirement | No [1] | Yes [1] [15] |

| Sample Consumption | High [1] [4] | Low [1] [4] |

| Throughput | Low [1] [4] | High [1] [4] |

| Solvent Compatibility | Narrow [1] | Broad [1] |

Key Differentiating Factors

Thermodynamic Profiling

ITC's unique capability to directly measure enthalpy changes (ΔH) provides crucial insights into the binding mechanism. Enthalpy-driven interactions typically indicate strong hydrogen bonding or van der Waals forces, while entropy-driven binding often suggests hydrophobic effects or conformational changes [12]. This information is invaluable in drug design, where understanding the driving forces behind ligand binding can guide optimization efforts.

Immobilization Artifacts

A significant advantage of ITC is that both binding partners remain free in solution, avoiding potential artifacts that can occur in SPR when one molecule is immobilized on a sensor surface [1]. Immobilization in SPR can sometimes alter protein conformation or block binding sites, potentially affecting the measured affinity [15].

Kinetic Capabilities

SPR clearly outperforms ITC in determining association and dissociation rate constants (kon and koff), which provide insights into binding mechanism and residence time [1] [4]. While methods like kinITC have been developed to extract kinetic information from calorimetric data, this remains challenging and not routinely applicable [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

ITC Experimental Workflow

Sample Preparation Requirements

Buffer Considerations: The two binding partners must be in identical buffers to minimize heats of dilution that can mask binding signals. Even small differences in pH, salt concentration, or DMSO content can cause significant background effects [12] [16]. Reducing agents should be kept at low concentrations (≤1 mM), with TCEP recommended over β-mercaptoethanol or DTT [12].

Concentration Guidelines: Typical starting concentrations range from 5-50 μM for the macromolecule in the cell and 50-500 μM for the ligand in the syringe, aiming for a c-value (c = n•[M]cell/KD) between 10-100 for optimal data fitting [12]. Accurate concentration measurement is critical, as errors directly affect stoichiometry and KD determination [12].

Critical Experimental Parameter: The C-Value

The c-value (c = n•[M]cell/KD) fundamentally determines the shape and quality of ITC binding isotherms [12]:

- Ideal Range (10-100): Enables accurate determination of KD, ΔH, and n

- Low C-value (<10): Can sometimes fit KD but stoichiometry becomes unreliable

- High C-value (>1000): Allows accurate stoichiometry determination but not KD

SPR Experimental Methodology

SPR experiments require immobilizing one binding partner (ligand) on a sensor chip surface and flowing the other partner (analyte) over this surface [1] [15]. The binding-induced change in refractive index near the sensor surface is monitored in real-time, producing sensorgrams that track association and dissociation phases [1] [15].

Immobilization Methods: The most common immobilization approach is amine coupling onto carboxymethyl dextran chips (e.g., CM5 chips) [15]. Alternative strategies include capture methods using streptavidin-biotin interactions or antibody-mediated capture, which can better orient molecules and preserve activity [15].

Buffer Considerations: SPR running buffers must be optimized to minimize non-specific binding to the sensor surface. Regeneration solutions that disrupt the binding interaction without damaging the immobilized ligand are required for reusable sensor chips [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Proteins | Primary interacting molecules | Purity and homogeneity critical; aggregates interfere with measurements [12] |

| Matched Buffer Systems | Solvent for both binding partners | Identical composition essential to prevent dilution artifacts [12] [16] |

| ITC Instrument | Measures heat changes during binding | MicroCal PEAQ-ITC, VP-ITC, or iTC200 systems [16] |

| SPR Sensor Chips | Platform for ligand immobilization | CM5 most common; specialized chips available [15] |

| Reducing Agents | Maintain protein stability | TCEP recommended over β-mercaptoethanol or DTT [12] |

| Degassing System | Prevents bubble formation | Essential for stable baselines [12] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

ITC Data Processing

Heat of Dilution Correction: Proper correction for non-binding heat effects is essential. This can be achieved by averaging the heats from the final injections (after saturation), performing a control titration of ligand into buffer, or using fitted offset options in analysis software [16].

Non-linear Curve Fitting: Corrected data is fit to appropriate binding models (typically a single-site model for 1:1 interactions) to extract KD, ΔH, and n values [12] [13]. Global analysis tools like SEDPHAT enable more complex modeling for cooperative or multi-site interactions [1].

Troubleshooting Common ITC Issues

- Large Injection Heats with No Saturation: Typically indicates significant buffer mismatch between cell and syringe solutions [16]

- Failure to Return to Baseline: Caused by insufficient time between injections; increase interval duration [16]

- No Detectable Binding Heat: May indicate no binding, weak affinity, or very small enthalpy change; consider increasing concentrations or changing conditions [16]

- Spikes or Noisy Baseline: Often results from bubbles in the cell/syringe or contamination [16]

Application in Drug Discovery: A Comparative Case Study

In pharmaceutical research, ITC and SPR provide complementary information throughout the drug development pipeline. ITC's ability to delineate enthalpic and entropic contributions is particularly valuable in lead optimization, helping medicinal chemists understand the structural features driving binding [12].

For protein-small molecule interactions, ITC excels at characterizing the thermodynamics of binding, revealing whether interactions are driven by favorable hydrogen bonding (negative ΔH) or hydrophobic effects (positive ΔS) [12]. This information guides molecular design, as enthalpically-driven binders often exhibit better selectivity and optimization potential.

SPR, conversely, provides critical kinetic information that ITC cannot easily obtain. The association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rates determined by SPR help predict drug residence time, which can correlate better with in vivo efficacy than binding affinity alone [1] [4]. SPR's higher throughput also makes it more suitable for screening applications [1] [15].

ITC and SPR represent complementary approaches for characterizing protein-small molecule interactions, each with distinct strengths and limitations. ITC provides a complete thermodynamic profile (K_A, ΔH, ΔS, and n) without immobilization requirements, making it ideal for mechanistic studies and understanding the driving forces behind molecular recognition. SPR offers superior kinetic analysis, sensitivity, and throughput, valuable for screening and detailed binding mechanism studies. The choice between these techniques should be guided by specific research objectives, with many laboratories employing both methods to obtain a comprehensive understanding of biomolecular interactions. As drug discovery efforts increasingly focus on understanding the qualitative aspects of binding beyond simple affinity measurements, both techniques will continue to play crucial roles in advancing therapeutic development.

In the field of protein-small molecule interaction research, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) stand as two powerful, label-free analytical techniques. While both methods are adept at determining binding affinity, they provide fundamentally different and complementary information. SPR is the premier technique for obtaining real-time kinetic data, revealing the rates of association and dissociation. ITC is unparalleled in providing a complete thermodynamic profile, detailing the enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and stoichiometry of an interaction in a single experiment. This guide provides an objective comparison to help researchers select the optimal technique for their specific project in drug discovery and biophysical characterization.

SPR and ITC at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core capabilities and typical requirements of each method.

| Feature | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Kinetics (kon, koff) & Affinity (KD) | Thermodynamics (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS, n) & Affinity (KD) |

| Affinity Range | Picomolar (pM) to millimolar (mM) [1] [8] | Nanomolar (nM) to micromolar (μM) [2] |

| Immobilization | Required (One partner on sensor chip) | Not required |

| Sample State | One partner immobilized on a surface | Both partners in solution |

| Sample Consumption | Low volume and concentration [2] | High quantity of purified protein required[c:1][c:4] |

| Throughput | High to medium[c:1][c:6] | Low (~1-2 hours/assay)[c:1] |

| Key Advantage | Real-time kinetic profiling; high sensitivity | Complete thermodynamic profile in one experiment |

Detailed Technical Comparison

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): The Kinetic Powerhouse

SPR is an optical technique that measures biomolecular interactions in real-time by detecting changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface[c:1].

- Experimental Protocol: One binding partner (the ligand) is immobilized onto a dextran-coated gold sensor chip. The other partner (the analyte) is flowed over the surface in a microfluidic system. Binding events cause a mass change on the chip, altering the refractive index and shifting the SPR angle. This shift, measured in Resonance Units (RU), is monitored over time to generate a sensorgram[c:2][c:4].

- Data Output: The real-time sensorgram is fitted to a kinetic model to determine the association rate constant (kon) and the dissociation rate constant (koff). The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated from the ratio koff/kon[c:1][c:6].

- Strengths and Considerations:

- Kinetic Insight: Direct measurement of on/off rates is crucial for drug discovery, where a slow off-rate (koff) often correlates with long target occupancy and efficacy[c:6].

- High Sensitivity: Requires small sample volumes (25-100 µL per injection) and can detect weak interactions, making it ideal for fragment-based screening[c:3][c:4].

- Immobilization Challenge: Covalent immobilization requires optimization and can potentially affect protein activity or accessibility[c:4].

- Instrument Cost and Maintenance: SPR systems have a high initial cost and require regular maintenance of fluidic systems[c:1][c:4].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): The Thermodynamic Benchmark

ITC directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a molecular binding event at a constant temperature, providing a full thermodynamic characterization[c:1][c:2].

- Experimental Protocol: The sample cell is filled with a solution of one binding partner (e.g., a protein). The second partner (e.g., a small molecule) is loaded into a syringe at a concentration typically 10-20 times higher. The ligand is titrated into the cell in a series of injections, and the instrument measures the power required to maintain a constant temperature difference between the sample and a reference cell. The resulting thermogram plots heat change against time or molar ratio[c:2][c:8].

- Data Output: Integration of the heat peaks from the thermogram allows for the direct determination of the binding constant (KA), reaction stoichiometry (n), and enthalpy (ΔH). The free energy (ΔG) and entropy (ΔS) are then calculated from these parameters[c:2][c:4].

- Strengths and Considerations:

- Complete Thermodynamic Profile: ITC is the only technique that directly measures all binding parameters in a single experiment without a label[c:6]. Understanding whether binding is driven by enthalpy or entropy is vital for rational drug design.

- No Immobilization: Studies molecules in their native, solution state, avoiding potential artifacts from surface attachment[c:4].

- High Sample Consumption: Requires relatively large amounts of sample (e.g., 10-100 µM protein in 300-500 µL) and high concentrations, which can be a limitation for scarce proteins[c:1][c:4].

- Lower Throughput: Each titration is slow, typically taking 30 minutes to 2 hours, making it less suitable for high-throughput screening[c:1].

Experimental Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the fundamental operational and data pathways for SPR and ITC.

SPR Experimental Workflow

ITC Experimental Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and reagents essential for successful SPR and ITC experiments.

| Category | Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| SPR-Specific | Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) | Provides a functionalized gold surface for ligand immobilization. Chip type depends on ligand properties and coupling chemistry[c:4]. |

| Running & Regeneration Buffers | Maintain a consistent environment for binding and remove bound analyte to regenerate the sensor surface for a new cycle[c:6]. | |

| ITC-Specific | High-Purity Solvents & Buffers | Essential to prevent heat artifacts from buffer mismatches or impurities. DMSO compatibility is crucial for small molecule studies[c:4][c:7]. |

| Precision Syringe | Ensures accurate and reproducible injection volumes during the titration process, critical for data quality. | |

| Common to Both | Highly Purified Proteins & Ligands | Sample purity is paramount for both techniques to avoid non-specific binding (SPR) or confounding heat signals (ITC)[c:4]. |

| Buffer Exchange System (e.g., dialysis) | Ensures perfect buffer matching between all samples to eliminate heat of dilution (ITC) and refractive index artifacts (SPR). |

The choice between SPR and ITC is not a matter of which technique is superior, but which is more appropriate for the specific research question.

- Use SPR when your goal is to understand the kinetics of an interaction (how fast it forms and breaks apart), when sample is limited, or when higher throughput is required for screening.

- Use ITC when you need a full thermodynamic understanding (the driving forces behind binding), need to confirm stoichiometry, or when working with systems where surface immobilization is problematic.

In an ideal drug discovery workflow, these techniques are used in tandem. SPR is often employed for initial kinetic screening of compound libraries, while ITC is used for in-depth thermodynamic characterization of the most promising hits, providing a comprehensive picture of molecular interactions for effective drug development[c:4].

The quantitative characterization of molecular interactions, particularly the determination of binding affinity and sensitivity, is fundamental to biological research and pharmaceutical development. For researchers investigating protein-small molecule interactions, selecting the appropriate analytical technique is paramount to obtaining reliable, biologically relevant data. Among the plethora of available methodologies, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) have emerged as two of the most powerful and widely adopted label-free technologies. This guide provides an objective comparison of SPR and ITC, focusing on their operational affinity and sensitivity ranges, to empower scientists in selecting the optimal tool for their specific research context, from early drug discovery to detailed mechanistic studies.

Core Technology Comparison: SPR vs. ITC

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) differ fundamentally in their detection principles, which directly influences the type of information they provide and their suitability for different experimental questions.

SPR is an optical technique that measures changes in the refractive index on a sensor surface. One interactant (the ligand) is immobilized on a specialized sensor chip, while the other (the analyte) flows over the surface in solution. When binding occurs, the resulting mass change alters the refractive index, allowing real-time monitoring of the interaction. This provides a direct readout of association and dissociation rates, from which the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is calculated [8] [2] [17].

ITC, in contrast, is a thermodynamic technique that directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event. In a typical experiment, one molecule is titrated into a solution containing its binding partner. The instrument measures the heat required to maintain a constant temperature between the sample and a reference cell. From a single experiment, ITC can simultaneously determine the binding affinity (KD), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS) of the interaction [8] [1] [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of SPR and ITC

| Feature | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Optical (refractive index change) | Calorimetric (heat change) |

| Primary Data Output | Kinetic rates (kon, koff) | Thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS) |

| Measurement Environment | Solid-liquid interface (immobilization required) | Free solution (no immobilization) |

| Key Measurables | KD, kon, koff | KD, n, ΔH, ΔS, ΔG |

| Label-Free | Yes | Yes |

Figure 1. Comparative experimental workflows for SPR and ITC. The SPR pathway involves surface immobilization and yields kinetic data, while the ITC pathway occurs in solution and provides a full thermodynamic profile.

Affinity and Sensitivity Ranges

The most critical differentiating factor between SPR and ITC for many applications is their effective affinity and sensitivity range. This determines whether a technique can reliably detect and quantify the interaction of interest.

Quantitative Comparison of Operational Ranges

Table 2: Affinity, Sensitivity, and Sample Requirements

| Parameter | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Range (KD) | Picomolar (pM) to Millimolar (mM) [8] [1] | Nanomolar (nM) to Micromolar (μM) [2] [1] |

| Sensitivity | Excellent for weak interactions; detects low nanomolar (nM) to picomolar (pM) binders [2] | Moderate; struggles with very weak interactions (KD > 100 μM) due to low heat signal [2] |

| Sample Consumption | Low volume (25–100 μL per injection); wide concentration range acceptable [8] [2] | High quantity required; typically 300–500 μL at 10–100 μM concentration [2] [4] |

| Sample Purity | Tolerant of some crude samples and buffer components [8] [4] | Requires highly purified samples to avoid confounding heat signals [2] |

SPR demonstrates a broader dynamic range, capable of characterizing interactions from the robust picomolar level to weak millimolar affinities [8] [1]. This makes it particularly powerful in fragment-based drug discovery, where identifying weak, initial binders is essential. Its high sensitivity allows for accurate measurement even when sample is limited.

ITC operates optimally in the nanomolar to micromolar range [2] [1]. Its main limitation for weak binders is the small enthalpy change (heat signal), which can be lost in the background noise [2]. Consequently, ITC requires higher sample concentrations and purity to generate a robust signal, which can be a constraint for difficult-to-purify proteins [2].

Experimental Protocols and Data Output

The distinct operational principles of SPR and ITC necessitate different experimental approaches and data analysis workflows.

Detailed SPR Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction

1. Ligand Immobilization: The protein (or small molecule) is immobilized onto a sensor chip. Common methods include amine coupling (for proteins), or capture via anti-His tags or streptavidin-biotin interactions for higher uniformity [18] [17].

2. Sample Preparation and Running: A concentration series of the small molecule analyte is prepared in a suitable running buffer. For kinetic analysis, a minimum of five concentrations spanning a 10-fold range above and below the expected KD is recommended.

3. Binding Cycle: The analyte is flowed over the ligand surface for the "association" phase, followed by a switch to running buffer for the "dissociation" phase. The sensor surface is then regenerated to remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand [17].

4. Data Analysis: The resulting sensorgrams (real-time binding curves) are fitted to an appropriate kinetic model (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding) to extract the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants. The equilibrium dissociation constant is calculated as KD = koff/kon [18] [17].

Detailed ITC Protocol for Protein-Small Molecule Interaction

1. Sample Preparation: The protein is dialyzed into an appropriate buffer to ensure perfect matching between the cell and syringe solutions. The small molecule (ligand) is dissolved in the final dialysis buffer to minimize heat of dilution artifacts.

2. Experimental Setup: The protein solution is loaded into the sample cell. The ligand solution is loaded into the injection syringe at a concentration typically 10-20 times higher than the protein in the cell [1] [6].

3. Titration Experiment: The ligand is injected into the protein solution in a series of small, sequential aliquots. The instrument measures the heat required to maintain a constant temperature after each injection [6].

4. Data Analysis: The integrated heat peaks are plotted against the molar ratio to generate a binding isotherm. Nonlinear regression fitting of this isotherm yields the binding constant (KA = 1/KD), reaction stoichiometry (n), and enthalpy change (ΔH). The entropy change (ΔS) is calculated using the relationship ΔG = ΔH - TΔS = -RTlnKA [1] [6].

Table 3: Nature and Richness of Data Output

| Data Type | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity (KD) | Yes (calculated from kon/koff) | Yes (directly measured) |

| Kinetics | Yes (real-time kon and koff) | No (primarily) [8] [2] |

| Thermodynamics | Limited (can infer from van't Hoff analysis) | Yes (full profile: ΔH, ΔS, ΔG) [2] [6] |

| Stoichiometry (n) | Indirectly | Yes (directly measured) [1] |

| Throughput | Moderate to High | Low (0.25 - 2 hours/assay) [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of SPR or ITC experiments requires careful selection and preparation of key reagents.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SPR Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) | Provides the surface for ligand immobilization. | Choice depends on ligand properties and coupling chemistry (e.g., SA for biotinylated molecules) [17]. |

| Running Buffer (e.g., PBS, HEPES) | Serves as the solvent and matrix for analytes. | Must be free of interfering additives like high-concentration Tris; should match ITC dialysis buffer for cross-comparison [17]. |

| Purified Target Protein | The macromolecule for interaction studies. | Purity >90% is critical; activity must be preserved after immobilization for SPR [17]. |

| Purified Small Molecule | The analyte or titrant for binding studies. | Solubility in aqueous buffer is a common challenge; DMSO stocks often used (<1% final) [17]. |

| Regeneration Solution (SPR) | Removes bound analyte without denaturing the ligand. | Must be optimized for each interaction (e.g., mild acid/base, high salt) [18]. |

| Dialysis Buffer (ITC) | Ensures perfect buffer matching to minimize dilution heats. | Critical for accurate ITC data; protein is dialyzed, and ligand is dissolved in the final dialysate [6]. |

Application in Drug Development: A Practical Perspective

The choice between SPR and ITC is often dictated by the stage and goal of the research project within the drug development pipeline.

For Hit Identification and Kinetic Profiling: SPR is the preferred tool due to its high sensitivity and ability to measure binding kinetics [8] [2]. The real-time data allows researchers to not only identify binders but also characterize how long the complex remains intact (residence time), a parameter increasingly recognized as critical for drug efficacy [17]. Its lower sample consumption is also advantageous when material is scarce.

For Lead Optimization and Mechanistic Studies: ITC provides the complete thermodynamic profile that is invaluable for understanding the driving forces behind binding [6]. Knowing whether an interaction is enthalpy-driven (often indicative of specific hydrogen bonds/van der Waals forces) or entropy-driven (often indicative of hydrophobic interactions) can guide medicinal chemists in optimizing lead compounds [6]. Its solution-based, label-free nature also most closely mimics the physiological environment.

As reflected in the literature, many cutting-edge research programs employ both techniques in a complementary fashion. For instance, a 2019 study on PROTACs (complex small molecules that induce protein degradation) used SPR to measure the kinetics of ternary complex formation and dissociation, while ITC was used to validate affinities and probe cooperativity thermodynamically [18]. This synergistic approach provides a more comprehensive picture of the molecular interaction than either technique could deliver alone.

Practical Guide: Designing and Executing SPR and ITC Experiments for Small Molecules

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for analyzing biomolecular interactions in real-time, widely used in drug discovery and basic research. Its functionality hinges on a critical step: the precise immobilization of a ligand to a sensor surface. The choice of immobilization strategy and the subsequent optimization of surface chemistry are paramount to the success of any SPR experiment. They directly dictate the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability of the binding data obtained for analytes. A poorly designed surface can lead to issues such as non-specific binding, steric hindrance, loss of ligand activity, and unstable baselines, ultimately compromising data quality. This guide provides a detailed overview of immobilization strategies and surface chemistry, framing them within the broader context of selecting the appropriate tool for measuring protein-small molecule binding affinity, with a comparative focus on SPR and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC).

SPR vs. ITC: A Comparative Framework for Binding Analysis

Before delving into experimental setup, it is essential to understand how SPR compares to ITC, a common alternative technique. The choice between them often depends on the specific informational needs of the research project. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of SPR and ITC for Biomolecular Interaction Analysis

| Parameter | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | Real-time kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (KD) | Thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS, KD) and stoichiometry (n) |

| Affinity Range | Picomolar (pM) to millimolar (mM) [1] | Micromolar (µM) to low nanomolar (nM) [2] |

| Immobilization | Required (ligand immobilized on sensor chip) | Not required; solution-based technique |

| Sample Consumption | Low sample volume and concentration [2] | Large amounts of purified protein required [4] [2] |

| Throughput | High | Low [4] |

| Key Advantage | Provides direct kinetic information; high sensitivity | Provides complete thermodynamic profile in a single experiment; no immobilization |

| Key Challenge | Potential for surface-induced artifacts; complex data analysis | Low sensitivity for weak binders; high sample consumption |

SPR is the preferred method when kinetic rate constants (association and dissociation rates) are critical, such as in antibody characterization and drug candidate screening. In contrast, ITC is unparalleled for providing a complete thermodynamic profile (enthalpy and entropy changes) of an interaction in a single experiment without the need for immobilization [2] [8]. For a holistic understanding, these techniques are often used complementarily.

Foundational Principles of SPR Sensing

SPR is an optical phenomenon that occurs at the interface between a metal (typically gold) and a dielectric (e.g., a buffer solution). In the most common Kretschmann configuration, a polarized light source is directed through a prism onto a sensor chip with a thin gold layer. At a specific angle of incidence, photons couple with free electrons in the metal to create surface plasmons, generating an evanescent wave that extends a short distance (~200 nm) into the solution. This causes a dip in the intensity of the reflected light at the resonance angle [19].

Any change in the refractive index within the evanescent field, such as the binding of an analyte to an immobilized ligand, shifts the resonance angle. The SPR instrument detects this shift in real-time, producing a sensorgram where the response (in Resonance Units, RU) is plotted against time. This signal is proportional to the mass concentration on the surface, allowing for the quantitative assessment of binding events [19].

Diagram Title: SPR Principle and Sensorgram Output

Surface Chemistry and Immobilization Strategies

The goal of immobilization is to attach the ligand stably to the gold sensor chip while preserving its biological activity and allowing the analyte full access to the binding site. Strategies fall into two broad categories: chemical coupling (covalent bonds) and capture methods (non-covalent, affinity-based bonds) [20].

Surface Activation and Functionalization

Before immobilization, the gold surface must be cleaned and functionalized. Common pre-treatments include piranha solution (a mixture of H2SO4 and H2O2) or O2-plasma etching to remove organic contaminants [19]. The most common method for functionalization is the formation of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) using alkanethiols, which spontaneously form a stable layer on the gold via gold-thiol chemistry [19]. The terminal group of the thiol determines the subsequent chemistry.

- 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA): Provides terminal carboxyl groups (-COOH) that can be activated for amine coupling, the most prevalent covalent method [19].

- Mixed SAMs: Using a combination of long-chain functional thiols (e.g., 11-MUA) and short-chain backfiller thiols (e.g., 1-octanethiol or 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) can reduce steric hindrance and minimize non-specific binding by creating a less densely packed surface [19].

Covalent Immobilization Methods

Table 2: Common Covalent Immobilization Chemistries

| Chemistry | Mechanism | Ligand Requirement | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amine Coupling | Activates carboxyl groups on the SAM (via EDC/NHS) to react with primary amines (lysine residues) on the ligand. | Free amine groups. | Simple, versatile, high stability, high ligand density. | Random orientation, risk of denaturation at low pH. |

| Thiol Coupling | Reacts with free sulfhydryl groups (cysteine residues) on the ligand. | Free thiol group (native or introduced). | Site-specific orientation. | Requires a free cysteine, which may not be native. |

| Aldehyde Coupling | Reacts with aldehyde groups generated from oxidizing carbohydrate moieties. | Glycosylated ligands (e.g., antibodies). | Site-specific orientation via Fc region. | Limited to glycosylated proteins. |

Amine Coupling Step-by-Step Protocol: This is a generalized protocol for a carboxymethylated dextran (e.g., CM5) sensor chip.

- Surface Activation: Inject a 1:1 mixture of 0.4 M EDC (N-Ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 0.1 M NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) over the sensor surface for 5-7 minutes. This creates reactive NHS esters.

- Ligand Injection: Dilute the ligand to a concentration typically between 5-100 µg/mL in a low-salt coupling buffer (e.g., 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.0-5.5, determined empirically). Inject this solution over the activated surface for 5-10 minutes.

- Blocking: Inject 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 5-7 minutes to deactivate any remaining NHS esters and block unreacted sites.

- Washing: Perform several wash cycles with running buffer to remove any non-covalently bound ligand.

Capture Immobilization Methods

Capture methods utilize a high-affinity interaction between a pre-immobilized molecule on the chip and a tag on the ligand. This offers superior control over orientation.

Table 3: Common Capture Immobilization Methods

| Method | Sensor Chip | Ligand Requirement | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptavidin-Biotin | SA or NeutrAvidin chip. | Biotinylated ligand. | Very stable, near-covalent strength, excellent orientation. | Requires biotinylation, which must be optimized. |

| Anti-tag Antibody | Chip with immobilized antibody (e.g., anti-His, anti-GST). | His-tag (e.g., 6xHis), GST-tag. | Purifies and orients the ligand simultaneously. | Lower stability, ligand may leach off, requires regeneration. |

| Protein A/G | Chip with immobilized Protein A or G. | Antibodies (Fc region). | Excellent orientation for antibodies. | Lower stability, not suitable for all antibody subtypes. |

His-Tag Capture Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Surface Preparation: Use a pre-functionalized NTA (Nitrilotriacetic acid) sensor chip.

- Conditioning: Inject a short pulse of an EDTA solution to ensure the surface is free.

- Loading: Charge the surface with a 0.5 mM solution of NiCl2 or another divalent cation for 1-2 minutes.

- Ligand Capture: Inject the His-tagged ligand at a low concentration (1-10 µg/mL) in running buffer for 2-5 minutes. The goal is to achieve an optimal density, not maximum capture.

- Regeneration: After the binding experiment with the analyte, the surface is regenerated with a pulse of EDTA or mild acid to strip the ligand and the metal ion, readying the surface for a new cycle.

Diagram Title: Immobilization Method Selection Workflow

Optimization and Troubleshooting of SPR Surfaces

Even with a well-chosen strategy, optimization is crucial for high-quality data.

- Ligand Density Optimization: A density that is too high can cause steric hindrance or mass transport limitation, where the rate of analyte binding is limited by its diffusion to the surface rather than the interaction itself. A density that is too low yields a weak signal. Test a range of densities and choose the lowest that gives a robust signal without kinetic artifacts [21].

- Minimizing Non-Specific Binding (NSB): NSB occurs when the analyte adheres to the sensor surface non-specifically. Strategies to mitigate it include:

- Surface Blocking: After immobilization, block remaining reactive groups with an inert protein like BSA or casein [21].

- Buffer Additives: Include surfactants like Tween-20 (0.005-0.01%) in the running buffer to reduce hydrophobic interactions [21].

- Use a Control Flow Cell: Always immobilize a irrelevant protein or use a blank, blocked surface in a reference flow cell to subtract systemic and non-specific signals.

- Surface Regeneration: This is the process of removing bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand. Finding the right regeneration solution (e.g., low pH, high salt, mild detergent) is often empirical. A good regimen completely resets the baseline while allowing the ligand to be used for tens or hundreds of cycles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Immobilization

| Item | Function | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | A dextran matrix with carboxyl groups for covalent coupling via amine, thiol, or aldehyde chemistry. | General-purpose protein immobilization. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Surface with nitrilotriacetic acid for capturing His-tagged proteins via divalent cations like Ni²⁺. | Capture and orientation of recombinant His-tagged proteins. |

| SA Sensor Chip | Surface coated with streptavidin for capturing biotinylated ligands. | Highly stable and oriented immobilization of biotinylated DNA, proteins, or antibodies. |

| EDC/NHS Reagents | Cross-linking agents that activate carboxyl groups on the sensor chip for covalent coupling. | Essential for amine coupling and other chemistries requiring a reactive ester. |

| HBS-EP Running Buffer | A standard buffer (HEPES, NaCl, EDTA, Surfactant P20) for maintaining pH, ionic strength, and reducing NSB. | Standard running buffer for most protein interaction studies. |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Used to block remaining activated ester groups on the surface after covalent coupling. | Final step in amine coupling to deactivate the surface. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 1.5-2.5) | A common, low-pH regeneration solution for disrupting protein-protein interactions. | Regeneration for antibody-antigen surfaces. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | A strong ionic detergent for removing tightly bound analytes. | Harsh regeneration for very stable complexes (use sparingly). |

The journey to robust and informative SPR data begins at the sensor surface. A deep understanding of the available immobilization strategies—weighing the random but stable nature of covalent coupling against the oriented but sometimes less stable capture methods—is fundamental. Meticulous optimization of surface chemistry, ligand density, and buffer conditions is not merely a preliminary step but an ongoing process that directly dictates the quality of the kinetic and affinity data generated. By mastering these elements, researchers can confidently leverage SPR's unique strength—the provision of real-time kinetic information—to gain deep insights into molecular interactions, effectively complementing the thermodynamic profile provided by techniques like ITC.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a powerful, label-free analytical technique used for the quantitative thermodynamic characterization of biomolecular interactions. It directly measures the heat released or absorbed during a binding event, providing a complete thermodynamic profile in a single experiment without requiring immobilization or modification of the binding partners [8] [1]. This makes ITC an indispensable tool in fundamental research and drug discovery for characterizing interactions between proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, and other biomolecules [2] [6]. Unlike methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) which provide kinetic data, ITC uniquely determines binding affinity (K~a~ or K~D~), enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), and stoichiometry (n) [1] [2] [6]. The following diagram illustrates the core components and workflow of a typical ITC instrument.

Core Principles and Comparison with SPR

ITC operates by titrating one binding partner (the ligand) from a syringe into a solution containing the other binding partner (the macromolecule) housed in a sample cell. A reference cell, filled with buffer or solvent, compensates for background effects. The instrument measures the power required to maintain a constant temperature difference (typically zero) between the sample and reference cells [1] [6]. Each injection of ligand results in a heat pulse (exothermic or endothermic) that is recorded in real time. As binding sites become saturated, the heat signal diminishes until only the heat of dilution is observed. Analysis of the integrated heat data as a function of the molar ratio provides all binding parameters [1].

When selecting a technique for binding characterization, researchers often weigh ITC against Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). The table below summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of ITC and SPR for Binding Characterization

| Feature | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | Thermodynamics (ΔH, ΔS, n) | Kinetics (k~on~, k~off~) |

| Binding Affinity | Yes (K~D~) | Yes (K~D~) |

| Label Requirement | No | No |

| Immobilization | No | Yes [1] [2] |

| Sample Consumption | High (mg quantities) | Low (μg quantities) [2] |

| Throughput | Low | High [1] |

| Affinity Range | nM - μM [1] | pM - mM [8] [1] |

| Key Advantage | Complete thermodynamic profile in solution | Real-time kinetic data and high sensitivity [8] [2] |

Sample Preparation Protocol

Proper sample preparation is the most critical step for a successful ITC experiment, as the quality of the data is directly dependent on the purity and stability of the samples.

Buffer Matching and Dialysis

The macromolecule and ligand must be in identical buffer conditions to prevent artifactual heat signals from buffer mismatches. The recommended protocol is to dialyze both interaction partners into the same large batch of buffer [1]. The ligand from the syringe can be dialyzed separately or prepared by dissolution using the dialysate from the macromolecule. This ensures perfect matching of pH, salt concentration, and all other buffer components. A final dialysis of the macromolecule against a fresh portion of the buffer is performed immediately before the experiment, and this same buffer is used to prepare the ligand solution and to fill the reference cell [22]. This rigorous approach minimizes heat effects from differential dilution.

Sample Purity and Concentration

Proteins should be of high purity (>95%) as assessed by techniques like SDS-PAGE or size-exclusion chromatography to ensure that the measured heat originates from the binding event of interest and not from non-specific interactions or contaminant binding [22].

Concentration determination must be accurate. Use spectrophotometry with calculated extinction coefficients for proteins and nucleic acids. For ligands, quantitative analytical methods are essential. The recommended concentrations are based on the expected binding affinity. The concentration of the macromolecule in the cell should be between 10 to 100 μM, while the ligand in the syringe should be at a concentration 10- to 20-fold higher than that of the macromolecule [1] [22]. This high ligand concentration is necessary to achieve saturation of binding sites by the end of the titration.

Sample Degassing

Prior to loading, both the macromolecule and ligand solutions must be degassed under a light vacuum for approximately 10 minutes. This step removes dissolved gases that can form bubbles in the ITC cell during the experiment, which cause significant noise and baseline instability [6].

Titration Protocol Design

A well-designed titration protocol is key to obtaining data that is both accurate and precise.

Experimental Setup and Instrument Parameters

The standard setup involves loading the macromolecule into the sample cell (typically with a volume of 200-400 μL) and the ligand into the syringe. The following parameters must be defined in the instrument software before starting the experiment [1] [6]:

- Temperature: Typically 25°C or 37°C, but can be adjusted to study temperature-dependent effects.

- Reference Power: The baseline power applied to maintain the temperature difference between cells.

- Stirring Speed: Usually 750-1000 rpm to ensure rapid mixing without foaming or damaging the proteins.

- Number of Injections: Commonly 15-25 injections to adequately define the binding isotherm.

- Injection Volume: The first injection is often a small "dummy" injection (e.g., 0.5 μL) that is excluded from data analysis, as it can be affected by diffusion across the needle tip during equilibration. Subsequent injections are typically 2-10 μL each.

- Spacing between Injections: A duration of 120-300 seconds is standard, allowing the signal to return to baseline before the next injection.

The "c-Value" and Its Importance

The most critical concept in designing an ITC experiment is the c-value, defined as c = n * [M~t~] * K~a~, where n is stoichiometry, [M~t~] is the total macromolecule concentration in the cell, and K~a~ is the association constant [22]. The c-value determines the shape of the binding isotherm and thus the accuracy with which parameters can be fitted.

- Ideal Range: A c-value between 10 and 500 is generally acceptable, but a range of 10 to 100 is optimal for reliably determining both the binding constant (K~a~) and the enthalpy change (ΔH).

- Low c-value (c < 10): Results in a shallow, featureless isotherm, making it difficult to determine K~a~ accurately.

- High c-value (c > 500): Produces a step-shaped isotherm, which allows for precise determination of ΔH and stoichiometry (n), but a less precise K~a~.