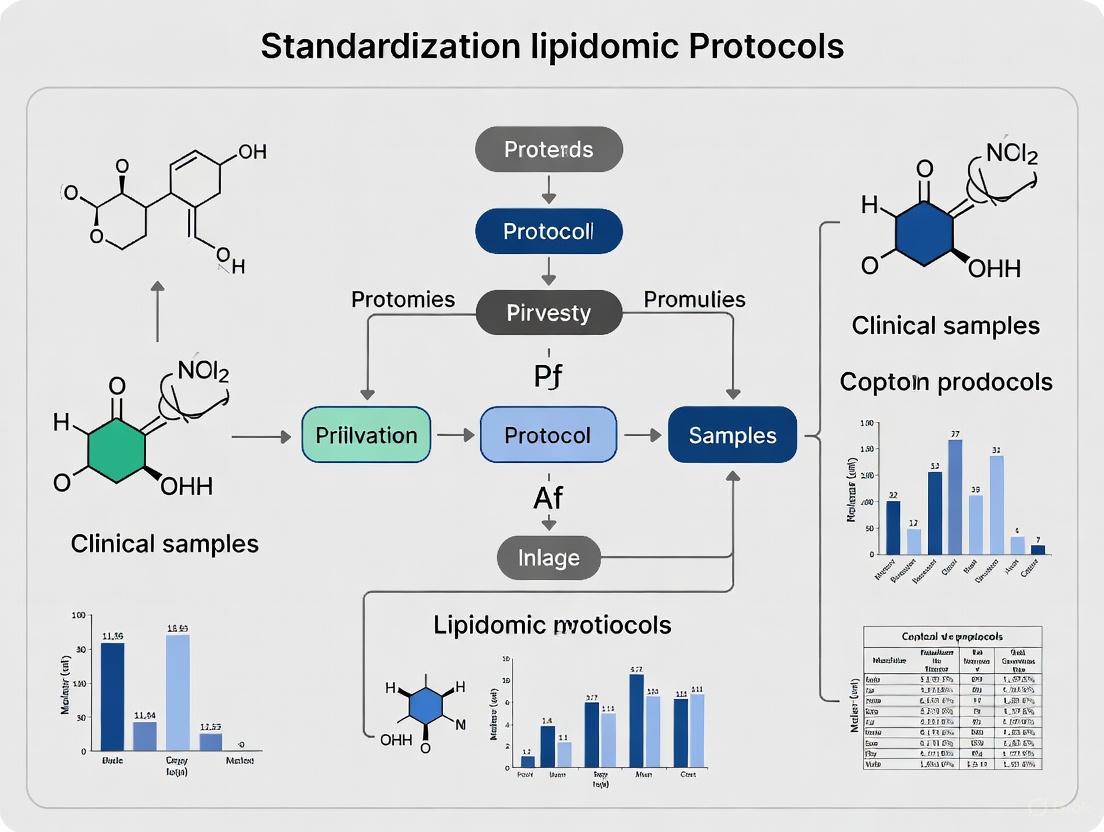

Standardizing Lipidomic Protocols for Clinical Samples: A Roadmap from Bench to Bedside

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on standardizing lipidomic protocols for clinical samples.

Standardizing Lipidomic Protocols for Clinical Samples: A Roadmap from Bench to Bedside

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on standardizing lipidomic protocols for clinical samples. It explores the foundational importance of pre-analytical standardization for reliable biomarker discovery, details methodological strategies from sample collection to data acquisition, addresses key troubleshooting and data analysis challenges, and establishes frameworks for analytical validation and cross-platform reproducibility. By synthesizing the latest evidence and guidelines, this review aims to bridge the gap between foundational lipid research and robust clinical application, ultimately enhancing the translational potential of lipid-based biomarkers in precision medicine.

The Critical Role of Standardization in Clinical Lipidomics

Why Pre-analytical Standardization is Non-negotiable for Reliable Biomarkers

Core Concepts: The Impact of Pre-analytical Variables

What is the pre-analytical phase and why is it a major source of error?

The pre-analytical phase encompasses all processes from test selection and patient preparation to sample collection, handling, transport, and storage before analysis [1]. This phase is the most error-prone part of the total testing process, contributing to 46% to 68.2% of all laboratory errors [2]. For metabolomics and lipidomics, pre-analytical issues account for up to 80% of laboratory testing errors [3]. Because many pre-analytical tasks occur outside the controlled laboratory environment, they present a significant challenge for ensuring reproducible and accurate biomarker data [4].

How do pre-analytical errors specifically affect lipidomics and metabolomics results?

Lipids and metabolites exhibit a wide range of stabilities ex vivo. Prolonged exposure of whole blood to room temperature allows continued metabolic activity in blood cells, altering the concentrations of sensitive species [5]. For example, in EDTA whole blood:

- After 24 hours at 21°C, 325 lipid species remained stable, but significant instabilities were detected for fatty acids (FA), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) [5].

- After 48 hours at room temperature, more than 30% of 1012 tested metabolites showed significant changes, with nucleotides, energy-related metabolites, peptides, and carbohydrates being most affected [3].

These ex vivo distortions can lead to the misinterpretation of data, the pursuit of false biomarker candidates, and reduced inter-laboratory comparability [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unstable Lipidomics Results in Multi-Center Studies

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Variable whole blood handling times [5] | Audit SOPs at all collection sites. Track time from draw to centrifugation for a sample batch. | Standardize a maximum hold time (e.g., 4 hours) and implement immediate cooling of whole blood tubes on ice water or at 4°C [6] [3]. |

| Inconsistent whole blood holding temperatures [5] [3] | Review temperature logs during transport and storage. | Provide all sites with standardized cool packs or portable refrigerated boxes. Mandate permanent cooling of whole blood before processing [5]. |

| Use of different anticoagulants [7] | Confirm the anticoagulant used in all samples. Check for chemical interferences in MS data (e.g., formate clusters). | Harmonize the type of blood collection tube across the entire study. For metabolomics, heparin is often recommended, but consistency is paramount [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Lipid Stability in Whole Blood

- Objective: To determine the stability of your lipid species of interest under different pre-analytical conditions.

- Methodology:

- Collect blood from ≥5 healthy volunteers into standardized K3EDTA tubes [5].

- Immediately aliquot whole blood and expose aliquots to different conditions (e.g., 0.5h, 1h, 2h, 4h, 24h) at 4°C, 21°C (RT), and 30°C [5].

- After each time point, centrifuge samples at 4°C (e.g., 3,100 g for 7 min) to obtain plasma [5].

- Store all plasma aliquots at -80°C until batch analysis.

- Perform lipid extraction using a validated method (e.g., MTBE/methanol/water) [5] and analyze via UHPLC-high resolution mass spectrometry.

- Data Analysis: Use fold-change analysis to compare lipid concentrations at each time/temperature point against the baseline (time 0) sample. Lipids with a significant fold-change (e.g., >±20%) are considered unstable under that condition [6].

Problem: High Rate of Sample Rejection or Hemolysis

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Improper phlebotomy technique [8] | Observe collection technique. Check if samples are drawn from IV lines. | Implement training for phlebotomists and clinical staff. Draw blood from the opposite arm of an IV infusion [2]. |

| Incorrect sample mixing [2] | Check for clots in anticoagulant tubes. Interview staff on mixing practices. | Educate on the need for gentle inversion (e.g., 8-10 times) immediately after collection. |

| Prolonged tourniquet application [8] | Time tourniquet application during draws. | Enforce a tourniquet time of less than 60 seconds. |

Problem: Degradation of Metabolites During Sample Processing

| Potential Cause | Investigation Steps | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Delayed centrifugation [3] [7] | Audit the time from sample collection to plasma separation. | Centrifuge within 2 hours of collection for most metabolites. For maximum stability, process immediately on ice or at 4°C [3]. |

| Inconsistent clotting time for serum [7] | Record the exact clotting time for serum samples. | Standardize clotting time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) at room temperature [7]. |

| Multiple freeze-thaw cycles [7] | Review sample storage logs and freeze-thaw history. | Aliquot samples into single-use portions before initial freezing. Strictly limit freeze-thaw cycles. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles

Q1: What are the most critical steps to control immediately after blood collection? The most critical steps are temperature and time until centrifugation [5] [3]. Whole blood should be cooled immediately (on ice water or at 4°C) and plasma should be separated from cells within a defined, short time frame, ideally within 2 hours [3]. This step is more critical than the handling of plasma/serum itself, as the billions of cells in whole blood remain metabolically active and can rapidly alter the concentration of labile lipids and metabolites [5].

Q2: Should I use plasma or serum for my lipidomics study? Both are acceptable, but plasma is generally recommended for better standardization [3]. The clotting process for serum generation introduces variability (clotting time) and can lead to the release of lipids and metabolites from platelets. Plasma generation is faster and easier to standardize. Crucially, you must be consistent throughout your study and clearly report which matrix was used [7].

Q3: How many freeze-thaw cycles can my samples tolerate? Freeze-thaw cycles should be minimized as much as possible. The stability of individual lipids and metabolites varies, but repeated cycling increases the risk of degradation. The best practice is to aliquot samples before the first freezing to avoid any freeze-thaw cycles for future analyses [7].

Sample Collection & Handling

Q4: Which anticoagulant should I use for plasma lipidomics? K3EDTA and heparin are common choices. However, the anticoagulant can affect the results for specific metabolites. For instance, sodium citrate interferes with the measurement of citric acid [7]. Test the tubes beforehand for interferences. The key is to use the same type of tube throughout your entire study [3] [7].

Q5: My samples were left at room temperature for 6 hours before processing. Can I still use them? It depends on your analytes of interest. While many lipid species are stable for 24 hours at 21°C, a significant number are not [5]. For a broad, untargeted analysis, this delay would likely introduce major artifacts. You should check your data against stability lists from studies like [5] or use quality control markers (e.g., a rise in lysolipids) to flag potentially compromised samples. For future experiments, this scenario should be avoided.

Q6: How does hemolysis affect lipidomics results? Hemolysis releases intracellular contents, including metabolites and enzymes, into the plasma or serum. Intracellular metabolite concentrations can be over 10 times higher than extracellular levels, leading to significant increases in many measured concentrations [7]. Hemolyzed samples should be noted during preparation, and their data should be interpreted with extreme caution or the sample excluded.

Storage & Analysis

Q7: What is the best long-term storage temperature for lipidomics samples? -80°C is the standard for long-term storage of plasma and serum samples for lipidomics and metabolomics studies. Even at -80°C, some metabolites may degrade over very long periods (years), so monitoring sample quality over time is advised [7].

Q8: How can I check if my samples have undergone pre-analytical degradation? Incorporate Quality Control (QC) samples during your analysis. A QC sample can be a pooled sample from all individuals that is analyzed repeatedly throughout the sequence. Drift in the signal of specific lipids in the QC sample can indicate analytical issues. Furthermore, research has identified potential QC markers for pre-analytical artifacts, such as specific lysophospholipids that increase with prolonged whole blood contact [5]. Monitoring these can help assess sample quality.

Essential Data & Protocols

Stability of Lipid Classes in Whole Blood

The following table summarizes quantitative data on lipid stability in EDTA whole blood, based on a study of 417 lipid species [5]. This can guide the urgency of processing for your target lipids.

| Lipid Class / Category | Key Stability Findings in Whole Blood | Recommendation for Max Hold Time (at RT) |

|---|---|---|

| Robust Lipids (e.g., many PC, SM, CE species) | 325 species stable for 24h at 21°C; 288 species stable for 24h at 30°C. | ≤ 24 hours [5] |

| Sensitive Lipids (e.g., FA, LPE, LPC) | Most significant instabilities detected in these classes. | Process as quickly as possible (within 2h) [5] |

| Oxylipins | No alterations beyond 20% variance for up to 4h at 20°C. | ≤ 4 hours [3] |

| General Metabolome (non-targeted) | ~10% of metabolite features changed significantly within 120 min at RT. | ≤ 2 hours (with immediate cooling strongly advised) [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Importance in Pre-analytical Standardization |

|---|---|

| K3EDTA Blood Collection Tubes | Preferred anticoagulant for plasma preparation in many lipidomics studies; prevents clotting by chelating calcium. Consistency in tube type is critical [6] [5]. |

| Pre-chilled Cool Packs / Ice Water Bath | Essential for immediate cooling of whole blood tubes after draw. Slows down cellular metabolism ex vivo, preserving the profile of unstable lipids and metabolites [6] [3]. |

| Timer | To accurately track and record the time from blood draw to centrifugation. This is a key variable that must be standardized and documented [5]. |

| Refrigerated Centrifuge | Allows for centrifugation at 4°C, further stabilizing the sample during processing by reducing enzymatic activity [5]. |

| Cryogenic Vials (Pre-labeled) | For aliquoting plasma/serum after centrifugation. Using pre-labeled vials saves time and reduces the risk of sample mix-ups. Aliquoting avoids repeated freeze-thaw cycles [7]. |

| Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) | A detailed, written protocol for every step from patient preparation to final storage. This is the most important tool to ensure consistency across personnel and sites [3]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Sample Journey from Blood Draw to Analysis

Decision Tree for Sample Usability

Foundational Knowledge: Lipid Classification and Functions

Lipids are a diverse group of hydrophobic or amphipathic molecules, insoluble in water but soluble in organic solvents, that are essential for all known forms of life [9] [10]. The LIPID MAPS classification system, a widely accepted framework in lipidomics research, categorizes lipids into eight main categories based on their chemical structures and biosynthetic pathways [11] [10].

Table 1: Lipid Categories, Structures, and Primary Biological Functions

| Lipid Category | Core Structure | Key Subclasses | Primary Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acyls (FA) [10] | Carboxylic acid with hydrocarbon chain [12] | Fatty acids, Eicosanoids, Prostaglandins [10] | Energy source, inflammatory signaling, pain/fever mediation [13] |

| Glycerolipids (GL) [10] | Glycerol backbone with fatty acyl chains [12] | Mono-, Di-, Triacylglycerols [10] | Long-term energy storage, thermal insulation [12] [13] |

| Glycerophospholipids (GP) [10] | Glycerol, two fatty acids, phosphate headgroup [12] | Phosphatidylcholine (PC), Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), Phosphatidylinositol (PI) [10] | Primary structural component of cell membranes, cell signaling, metabolic precursors [12] [13] |

| Sphingolipids (SP) [10] | Sphingoid base backbone [10] | Ceramides (Cer), Sphingomyelins, Gangliosides [12] [10] | Membrane structural components, powerful signaling molecules regulating inflammation and cell death [12] [14] |

| Sterol Lipids (ST) [11] | Four fused hydrocarbon rings [12] | Cholesterol, Steroid hormones [12] | Membrane fluidity, precursor to bile acids, vitamin D, and steroid hormones [12] [13] |

| Prenol Lipids (PR) [11] | Isoprene subunits [10] | Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K), Polyprenols [10] [13] | Enzyme activation, antioxidant function, molecular transport across membranes [13] |

| Saccharolipids (SL) [11] | Fatty acids linked to sugar backbones [10] | Acylated glucosamine precursors [10] | Membrane components in some microorganisms [10] |

| Polyketides (PK) [11] | Condensation of ketoacyl subunits [10] | Various macrocycles and polyethers [10] | Often have antimicrobial or pharmacological activity [10] |

The diagram below illustrates the hierarchical relationship of this classification system and the primary biological functions of the main lipid categories.

Methodologies in Lipidomics: A Technical Comparison

Lipidomics, the large-scale study of lipid molecular species and their biological functions, relies on advanced analytical technologies [11]. The choice of methodology is critical and depends on the research question, with a fundamental divide between targeted and untargeted approaches.

Table 2: Core Lipidomics Methodologies and Their Characteristics

| Methodology | Description | Key Applications | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untargeted Lipidomics [11] | Global profiling to detect & quantify all measurable lipids in a sample. | Biomarker discovery, novel pathway identification, comprehensive phenotyping [11]. | Hypothesis-generating; broad coverage of lipid species [11]. | Limited sensitivity for low-abundance lipids; requires complex data processing; lower reproducibility [11] [15]. |

| Targeted Lipidomics [11] | Precise quantification of a predefined set of lipids. | Validation of biomarkers, clinical assays, focused pathway analysis [16]. | High sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility; ideal for clinical translation [11] [16]. | Limited to known lipids; requires prior knowledge [11]. |

| Pseudotargeted Lipidomics [11] | Combines wide coverage of untargeted with precision of targeted. | Bridging discovery and validation phases [11]. | Improved reproducibility and coverage compared to untargeted [11]. | More complex method development [11]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy [16] | Quantifies lipids based on magnetic properties in a magnetic field. | High-throughput clinical lipoprotein subclass analysis (e.g., LipoProfile) [16]. | High reproducibility, non-destructive, minimal sample prep [16]. | Lower sensitivity and lipidomic coverage compared to MS [16]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting for Lipidomics Research

Q1: Our lipid identifications lack reproducibility between software platforms. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: Inconsistent identifications across different lipidomics software are a major, yet underappreciated, challenge. A 2024 study found that two popular platforms, MS DIAL and Lipostar, showed only 14.0% identification agreement from identical LC-MS spectra using default settings. Even with fragmentation (MS2) data, agreement only rose to 36.1% [15].

- Primary Causes: Discrepancies stem from the use of different lipid spectral libraries (e.g., LipidBlast vs. LipidMAPS), varying peak alignment algorithms, and insufficient use of retention time information. Co-elution of lipids can also lead to incorrect MS2 spectral assignments [15].

- Solutions:

- Mandatory Manual Curation: Do not rely solely on automated "top-hit" identifications. Visually inspect spectra for quality and plausibility [15].

- Cross-Platform Validation: Process your data with more than one software platform to identify conflicting annotations.

- Utilize MS2 Data: Always strive to acquire and use fragmentation data to confirm identifications.

- Data-Driven Outlier Detection: Implement machine learning-based quality control steps, such as support vector machine regression, to flag potential false positives [15].

Q2: What are the critical pre-analytical factors to control when collecting clinical samples for lipidomic analysis?

A: Pre-analytical variability is a major obstacle to standardizing clinical lipidomics.

- Fasting State: For plasma/serum lipidomics, a 12-hour fasting period is essential to allow for the clearance of dietary chylomicrons, which otherwise dominate the lipid profile and mask endogenous signals [12].

- Standardized Sampling: Use specialized blood collection tubes that prevent lipid oxidation (e.g., containing butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT)) [14]. Standardize the time of day for collection to account for diurnal rhythms.

- Sample Processing and Storage: Ensure consistent processing protocols (e.g., centrifugation speed and time to separate plasma/serum). Snap-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C to preserve lipid integrity [17].

Q3: Which lipid classes are currently showing the highest translational potential as clinical biomarkers?

A: While many lipids are under investigation, two classes stand out for their strong clinical evidence:

- Sphingolipids, specifically Ceramides: Certain ceramide species are powerful predictors of cardiovascular death. A clinically available assay (CERT2 score) that combines ceramides with phosphatidylcholines has been validated across large cohorts and licensed to major diagnostic companies for predicting cardiovascular risk [16] [14].

- Phospholipids: Specific phosphatidylcholine (PC) species are integral to the aforementioned CERT2 score. Furthermore, a ratio of phosphatidylinositol (36:2) to PC (38:4) has been identified as a potential biomarker for predicting which patients will benefit from statin treatment [16].

The diagram below summarizes a generalized workflow for a lipidomics study, highlighting key steps where the issues from the FAQs commonly arise.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Serum Lipidomics for Biomarker Discovery

The following protocol is adapted from current best practices for untargeted lipidomic profiling of human serum, a common workflow in clinical research [17].

Objective: To comprehensively profile lipid species from human serum for the discovery of disease biomarkers.

Materials & Reagents:

- Serum Samples (collected after 12-hour fast, stored at -80°C)

- Internal Standards (ISTDs): A mixture of deuterated or otherwise isotopically labeled lipids (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX) covering multiple lipid classes is essential for quantification [15].

- Extraction Solvents: Chilled methanol, methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) or chloroform, with 0.01% BHT to prevent oxidation [15].

- LC-MS Solvents: LC-MS grade water, acetonitrile, isopropanol, supplemented with 10 mM ammonium formate/acetate for mobile phase additives [17] [15].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Thaw serum samples on ice.

- Pipette a precise volume (e.g., 10 µL) of serum into a glass tube.

- Add a known amount of the ISTD mixture to every sample, quality control (QC) pool, and blank. This corrects for variability in extraction and ionization.

- Vortex thoroughly.

Lipid Extraction (MTBE/Methanol Method):

- Add a volume of methanol (e.g., 225 µL) to the serum, vortex.

- Add a larger volume of MTBE (e.g., 750 µL), vortex and shake for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Add volumes of water and/or water:methanol mixture (e.g., 188 µL) to induce phase separation. Centrifuge.

- The upper organic (MTBE) layer, containing the lipids, is collected and evaporated to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Reconstitute the dried lipid extract in a suitable solvent mix (e.g., 9:1 isopropanol:acetonitrile) for LC-MS analysis [15].

LC-MS Analysis:

- Chromatography: Use a reversed-phase C18 column (e.g., 50-100mm length, sub-2µm particle size) maintained at a controlled temperature (e.g., 45-55°C). Employ a binary gradient from a polar (A: acetonitrile/water 60:40) to a non-polar solvent (B: isopropanol/acetonitrile 90:10) over a 10-20 minute run time [15].

- Mass Spectrometry: Acquire data in both positive and negative ionization modes using data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) on a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF). This ensures broad lipid coverage. MS2 fragmentation spectra are crucial for identification [11] [15].

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Process raw data using software (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar, XCMS) for peak picking, alignment, and identification against databases (e.g., LipidMAPS, LipidBlast).

- Crucially, perform manual curation of identifications as outlined in FAQ #1 [15].

- Export a normalized data matrix (lipid species vs. abundance) for statistical and bioinformatic analysis, including multivariate statistics and machine learning for biomarker model development [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Clinical Lipidomics

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Corrects for losses during extraction and ion suppression/enhancement during MS analysis; enables absolute quantification [15]. | Avanti EquiSPLASH LIPIDOMIX; a mixture covering multiple lipid classes. |

| Antioxidants | Prevents oxidation of unsaturated lipids during extraction and storage, which can generate artifacts [15]. | Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT), added to extraction solvents at ~0.01%. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Minimizes background noise and ion suppression, ensuring high-quality chromatographic separation and mass spec detection. | Water, acetonitrile, isopropanol, methanol, chloroform/MTBE. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Used in targeted assays as internal standards for specific lipid species or pathways. | e.g., Deuterated Ceramide (d18:1/17:0) for quantifying specific ceramides [16]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (SRM) | Provides a benchmark for instrument performance, method validation, and inter-laboratory comparison [16]. | National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Standard Reference Materials. |

| Specialized Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes the lipidome at the moment of collection, reducing pre-analytical variability. | Tubes with specific preservatives for metabolomics/lipidomics (e.g., with BHT or other stabilizers) [14]. |

In clinical lipidomics, the integrity of research data is heavily dependent on the biological fidelity of samples before they ever reach the mass spectrometer. The pre-analytical phase—encompassing sample collection, processing, and storage—introduces significant vulnerabilities that can distort the native lipid profile. Lipids are particularly sensitive to enzymatic degradation, oxidation, and chemical modification when exposed to suboptimal handling conditions. Recognizing and standardizing these pre-analytical procedures is therefore a critical prerequisite for ensuring reliable measurement of metabolites and lipids in LC-MS-based clinical research [18]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and validated protocols to help researchers identify, mitigate, and correct for these ex vivo vulnerabilities, supporting the broader goal of standardizing lipidomic protocols for clinical samples.

Quantitative Impact of Pre-Analytical Variables

Understanding the specific impact of different handling conditions is the first step in troubleshooting. The following table summarizes how key variables quantitatively affect major lipid classes, based on controlled studies.

Table 1: Impact of Sample Handling Conditions on Major Lipid Classes

| Pre-Analytical Variable | Affected Lipid Classes | Nature of Distortion | Documented Magnitude of Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delayed Processing (at Room Temperature) | Lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC), Phosphatidylcholines (PC), Free Fatty Acids [18] | Increase in lysolipids (e.g., LPC, LPE) and free fatty acids due to enzymatic activity (e.g., phospholipases) [18] | Significant alterations reported; specific compound classes show high sensitivity to processing delays [18]. |

| Inappropriate Freezing/Thawing | Phospholipids, Sphingolipids [18] [19] | Phase separation, membrane disruption, and accelerated hydrolysis [18] | Multiple freeze-thaw cycles lead to progressive degradation; single cycles can be detrimental for certain species [18]. |

| Collection Tube Anticoagulant (e.g., K3EDTA vs. Heparin) | Multiple classes including Sphingomyelins, Ether-linked Phospholipids [18] [19] | Altered enzymatic activity and chemical stability; ion chelation can affect metal-dependent processes [18] | Profound differences in lipid profiles observed; K3EDTA plasma is often standardized for clinical research [18]. |

| Ex Vivo Oxidation (due to prolonged RT exposure) | Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs), Phospholipids containing PUFAs [18] | Formation of oxidized lipid species and hydroperoxides, loss of native unsaturated lipids [18] | Can be mitigated by antioxidants like BHT; otherwise, rapid and significant for vulnerable species [18]. |

Troubleshooting Common Pre-Analytical Artifacts

This section addresses specific issues users might encounter, providing diagnostic steps and corrective actions.

Problem 1: Inconsistent Lysophospholipid Levels Between Sample Batches

- Question: "Why are my LPC and LPE levels highly variable across samples collected on different days, even from the same subject?"

- Background: Lysophospholipids are signaling lipids generated by the hydrolysis of phospholipids. Their levels are highly sensitive to pre-analytical enzymatic activity.

- Diagnosis:

- Check the time between blood draw and plasma separation. Prolonged contact with blood cells at room temperature is a primary cause.

- Verify the temperature during this interval. Enzymatic activity is temperature-dependent.

- Review the centrifugation protocol. Inconsistent g-force or time can lead to variable cell removal.

- Solution:

- Standardize the plasma processing time. The "clip-to-freezer" time should be minimized and consistent (e.g., consistently within 30 minutes) [18].

- Process all samples at a standardized temperature (e.g., 4°C) to slow enzymatic degradation.

- Ensure consistent centrifugation conditions (e.g., 2000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) across all samples.

Problem 2: Appearance of "Ghost Peaks" or High Baseline in Chromatograms

- Question: "My LC-MS chromatograms show unexpected peaks and a noisy baseline, interfering with quantitation. What could be causing this?"

- Background: Ghost peaks and baseline anomalies often stem from chemical contaminants introduced during sample handling or from the degradation of samples during storage [20].

- Diagnosis:

- Run a blank injection (solvent only). If ghost peaks persist, the contamination is from the mobile phase, solvents, or the LC system itself [20].

- If blanks are clean, the issue is likely in the sample. Check:

- Leaching from plasticware: Certain lipids can adsorb to or leach from specific types of tubes.

- Sample carryover in the autosampler.

- Degradation during storage, leading to new, oxidized lipid species.

- Solution:

- Use high-purity, MS-grade solvents and additives for both mobile phase and sample preparation.

- Use low-adsorption, certified tubes for sample storage.

- Implement rigorous autosampler washing protocols.

- Store samples at -80°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Use single-use aliquots.

Problem 3: Shifts in Retention Time or Poor Peak Shape

- Question: "My lipid peaks are tailing or their retention times are drifting, making alignment and identification difficult."

- Background: While often related to the LC-MS instrument itself (e.g., column degradation, pump issues), pre-analytical factors can also be the root cause [20].

- Diagnosis:

- Check the sample matrix. An over-abundance of proteins or salts from inefficient protein precipitation can foul the LC column.

- Inspect for non-volatile contaminants in the sample that can accumulate on the column head.

- Review the sample reconstitution solvent. Mismatched solvent strength can cause peak broadening.

- Solution:

- Optimize and validate the protein precipitation step to ensure efficiency and reproducibility.

- Ensure samples are properly centrifuged after preparation to remove any particulate matter before injection.

- Reconstitute the final extract in a solvent that matches the initial mobile phase composition.

Standardized Experimental Protocols for Robust Lipidomics

To ensure reproducibility, follow these detailed methodologies for key stages of sample processing.

Protocol 1: Standardized Blood Collection and Plasma Processing for Lipidomics

Objective: To obtain plasma with lipid profiles that closely reflect the in vivo state by minimizing ex vivo alterations.

Reagents & Materials:

- K3EDTA vacuum blood collection tubes (validated for low lipid absorption) [18]

- Pre-chilled centrifuge capable of maintaining 4°C

- Polypropylene cryovials (low-adsorption)

- Liquid nitrogen or -80°C freezer

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Antioxidant (e.g., 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol, BHT) [18]

Workflow:

- Collection: Perform venipuncture using K3EDTA tubes. Invert gently to mix.

- Immediate Transfer: Place tubes in a pre-chilled rack (4°C) or ice-water slurry immediately after draw.

- Prompt Processing: Centrifuge within 30 minutes of collection at 2000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C [18].

- Careful Aliquotting: Using a pipette, carefully transfer the upper plasma layer to pre-labeled cryovials, avoiding the buffy coat and platelet layer.

- Rapid Freezing: Flash-freeze aliquots in liquid nitrogen or place directly in a -80°C freezer. Record the exact freeze time.

- Storage: Store samples at -80°C until analysis. Avoid freeze-thaw cycles.

The following diagram illustrates the critical control points in this workflow to prevent a cascade of ex vivo degradation.

Protocol 2: Quality Control and Batch Monitoring

Objective: To monitor analytical performance and ensure data quality across different sample batches.

Reagents & Materials:

- Stable Isotope Labeled Internal Standards (IS) for key lipid classes [19]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) plasma reference material [19]

- Quality Control (QC) pool created from a small aliquot of all study samples

Workflow:

- Internal Standard Addition: Add a mixture of stable isotope-labeled lipid internal standards to every sample at the beginning of extraction to correct for losses during preparation and instrument variability [19].

- QC Sample Preparation: Create a large, homogeneous pool of human plasma from a subset of samples or a commercial source. Aliquot and store at -80°C.

- Batch Analysis Design: Include multiple replicates of the NIST plasma and the study-specific QC pool dispersed evenly throughout the sample sequence in each batch.

- Performance Monitoring: Track the retention time stability, peak area of key lipids in the QC samples, and internal standard response across all runs. A between-batch reproducibility (coefficient of variation) of <15% (and ideally <10%, as demonstrated in large studies) is a common target [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials required for implementing robust clinical lipidomic protocols.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Clinical Lipidomics

| Item | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| K3EDTA Tubes | Preferred anticoagulant for plasma collection in lipidomics. Prevents coagulation by chelating calcium. | Standardized use minimizes inter-study variability. Shown to yield more consistent lipid profiles compared to heparin [18] [19]. |

| Stable Isotope Internal Standards | Synthetic lipids with heavy isotopes (e.g., ^13C, ^2H) added to each sample prior to extraction. | Corrects for matrix effects, recovery variations, and instrument sensitivity drift. Essential for precise quantification [19]. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT) | Added during sample processing to inhibit ex vivo oxidation of unsaturated lipids. | Crucial for preserving the native state of polyunsaturated fatty acids and preventing the formation of oxidation artifacts [18]. |

| MS-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (ACN, MeOH, MTBE, etc.) for lipid extraction and LC-MS analysis. | Minimizes chemical noise, background interference, and injector/column contamination, which is a common source of ghost peaks and high baseline [20]. |

| NIST SRM 1950 | Standard Reference Material for human plasma. | Used as a quality control to monitor method performance and ensure inter-laboratory comparability [19]. |

Welcome to the Lipidomics Technical Support Center. This resource is designed to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigate the specific challenges of implementing data-driven lipidomics protocols with clinical samples. A core challenge in the field is the balance between analytical rigor, which is essential for reproducible biomarker discovery, and clinical feasibility, which dictates the practical application of these methods in healthcare settings.

A primary source of technical difficulty is the lack of standardization across platforms and laboratories [21]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice, frequently asked questions (FAQs), and detailed protocols to help you overcome these hurdles and generate high-quality, clinically relevant lipidomic data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inconsistent Lipid Identifications Between Software Platforms

Problem: Users obtain different lipid identification results when processing the same LC-MS spectral data with different software platforms (e.g., MS DIAL vs. Lipostar), leading to irreproducible biomarker discovery [22].

Symptoms:

- Low overlap in identified lipid species when the same raw data file is processed with two different software tools.

- Putative lipid biomarkers cannot be validated across different laboratory sites or in meta-analyses.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale and Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Cross-Platform Verification | Process identical LC-MS spectra in at least two open-access platforms (e.g., MS DIAL, Lipostar) and compare outputs. | A case study showed only 14.0% identification agreement using default settings with MS1 data and 36.1% with MS2 spectra [22]. This step highlights the scale of the problem. |

| 2. Mandatory Manual Curation | Manually inspect the MS2 fragmentation spectra for putative lipid identifications, especially for key biomarkers. | This is the most critical step for reducing false positives caused by co-elution of closely related lipids or limitations in library matching algorithms [22]. |

| 3. Multi-Mode LC-MS Validation | Collect and compare data from both positive and negative ionization modes for the same sample. | A lipid identified with high confidence in both modes is more likely to be a correct annotation. This adds a layer of verification [22]. |

| 4. Data-Driven Outlier Detection | Apply a machine learning-based quality control step, such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) regression with leave-one-out cross-validation, to retention time data. | This can help flag lipid identifications that are outliers from predicted retention behavior, indicating potential false positives for further manual review [22]. |

Guide 2: Managing Missing Values in Lipidomics Datasets

Problem: Lipid concentration tables contain a significant number of missing values (NA, NaN), complicating statistical analysis and biological interpretation [23].

Symptoms:

- Many lipid species have concentration values missing in a non-random pattern across sample groups.

- Statistical software fails or produces biased results during multivariate analysis.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Step | Action | Rationale and Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Investigate the Cause | Before imputation, investigate why values are missing. Is it due to low abundance (common in clinical samples), peak picking errors, or alignment issues? | Correctly classifying the type of missing data—Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR)—is essential for choosing the right imputation strategy [23]. |

| 2. Pre-filter the Data | Remove lipid species where the number of missing values exceeds a defined threshold (e.g., >35% of samples) [23]. | This simplifies the dataset and avoids imputing data for lipids that are effectively undetected in your experiment. |

| 3. Select an Imputation Method | Choose an imputation method based on the nature of your missing data. | k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) : Often recommended for MCAR and MNAR data in shotgun lipidomics [23]. Random Forest : Performs well for MCAR/MAR data in LC/MS metabolomics [23]. Half-minimum (hm) : Imputing with a percentage of the lowest measured concentration is a common and effective method for MNAR data (e.g., values below the limit of detection) [23]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the two most critical types of lipids for health and how do they impact clinical biomarker discovery?

While many lipids are important, two classes have a major impact on health and are central to clinical biomarker research:

- Phospholipids: These are the structural foundation of all cell membranes. Their composition influences membrane fluidity and how cells respond to hormones and medications. Abnormalities can appear years before clinical symptoms of metabolic disorders [14].

- Sphingolipids (particularly ceramides): These function as powerful signaling molecules that regulate inflammation, cell death, and metabolism. Elevated ceramide levels are a strong predictor of cardiovascular events, often outperforming traditional cholesterol measurements [14].

FAQ 2: Our clinical lipidomics data is very complex. What are the best practices for statistical processing and visualization?

For robust and reproducible analysis, a solid core of freely available tools in R or Python is recommended [23].

- Data Preparation: Handle missing values as described in the troubleshooting guide above. Normalize data to remove unwanted technical variation (e.g., batch effects) using quality control (QC) samples.

- Statistical Analysis: Use both univariate (e.g., student's t-test, ANOVA) and multivariate methods (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA). PCA is excellent for visualizing overall data structure and identifying outliers [24] [23].

- Visualization: Create standard plots like volcano plots (to visualize significance vs. fold-change) and heatmaps (to show clustering of samples and lipids) [23]. These tools help identify statistically significant trends and biologically relevant differences.

FAQ 3: What is the core difference between untargeted and targeted lipidomics workflows, and when should I use each?

The choice of workflow is fundamental to experimental design.

- Untargeted Lipidomics (Discovery): The goal is to comprehensively profile as many lipids as possible without prior hypothesis. It is used for hypothesis generation and biomarker discovery. This typically involves LC-MS workflows to separate complex mixtures, or shotgun workflows for rapid profiling [24] [25].

- Targeted Lipidomics (Validation): This method focuses on accurate identification and absolute quantification of a predefined set of lipids. It is hypothesis-driven and used to validate findings from untargeted studies on a larger cohort [25].

FAQ 4: How can I visually diagnose problems in my LC-MS/MS method to improve data quality?

The open-source platform DO-MS (Data-driven Optimization of MS) is designed for this purpose [26].

- It interactively visualizes data from all levels of a bottom-up LC-MS/MS analysis (e.g., from MaxQuant output).

- You can diagnose specific issues like poor sampling of elution peak apexes, MS2-level co-isolation, or contamination.

- By using DO-MS to optimize parameters, one study achieved a 370% increase in the efficient delivery of ions for MS2 analysis [26].

Experimental Protocol Tables

Table 1: Standardized LC-MS Lipidomics Protocol for Clinical Serum/Plasma Samples

This protocol provides a foundational workflow for robust lipid analysis of common clinical samples [22] [24] [25].

| Step | Parameter | Specification | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sample Prep | Lipid Extraction | Modified Folch (Chloroform: Methanol, 2:1) or MTBE method. | Include a cocktail of deuterated internal standards (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH) added before extraction to monitor recovery and enable quantification [22] [21]. |

| 2. LC Separation | Column | Reversed-Phase (e.g., C18 or C30). | C30 columns offer superior separation for lipid isomers [24]. |

| Mobile Phase | (A) Water/Acetonitrile; (B) Isopropanol/Acetonitrile. Both with 10mM Ammonium Formate [22]. | Additive promotes positive ion formation. | |

| 3. MS Analysis | Ionization | Electrospray Ionization (ESI). | Soft ionization for intact lipid molecules. |

| Mode | Data-Dependent Acquisition (DDA). | Acquires MS1 spectra followed by MS2 fragmentation of the most abundant ions. | |

| Polarity | Switch between Positive and Negative mode in separate runs. | Essential for comprehensive coverage of different lipid classes [22] [24]. | |

| 4. Data Processing | Software | MS DIAL, Lipostar, or commercial platforms. | Always perform manual curation of top lipid identifications using MS2 spectra [22]. |

| Database | LipidBlast, LipidMAPS. | Use consistent library versions for project-long reproducibility. |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Lipidomics

This table details essential materials and their critical functions in ensuring accurate and reproducible lipidomics data [22] [21].

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Lipid Internal Standards | - Correct for loss during extraction.- Monitor ionization efficiency.- Enable absolute quantification. | Chemically pure, synthetic standards (e.g., from Avanti Polar Lipids) are optimal. A mixture covering multiple lipid classes (e.g., Avanti EquiSPLASH) is recommended [22] [21]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Sample | - Monitor instrument stability over the run.- Assess technical variability and batch effects. | Typically a pool of a small aliquot of all biological samples analyzed. Run QCs repeatedly throughout the sequence [23]. |

| Standard Reference Material (SRM) | - Benchmark laboratory performance.- Cross-lab standardization. | For plasma/serum, NIST SRM 1950 is a commonly used reference material with consensus concentrations for many metabolites and lipids [23]. |

| Specialized Solvents | - High-purity, LC-MS grade solvents (e.g., Chloroform, Methanol, Isopropanol). | Minimize background noise and ion suppression. Use solvents with low UV absorbance and without plasticizers or antioxidants that interfere with MS. |

Lipidomics Workflow and Data Analysis Diagrams

Lipidomics Clinical Sample Workflow

Data Analysis & Troubleshooting Pathway

Implementing Robust Lipidomics Workflows: From Sample to Data

Core Concepts in Pre-analytical Lipidomics

Why Pre-analytical Phase is Critical: The pre-analytical phase encompasses all steps from patient preparation to the point where the sample is ready for analysis. Studies indicate that 46% to 68% of errors in laboratory testing occur in this phase, making it the most error-prone part of the workflow [27]. For lipidomics, the inherent chemical complexity and susceptibility of lipids to degradation mean that inappropriate sampling techniques, storage temperatures, and handling protocols can result in the degradation of complex lipids and the generation of oxidized or hydrolyzed artifacts [28]. Adhering to standardized pre-analytical practices is therefore fundamental for ensuring data quality, reproducibility, and the validity of biological conclusions.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our lipidomics data shows unexpectedly high levels of lysophospholipids. What could be causing this during sample handling?

Unexpectedly high levels of lysophospholipids are a common pre-analytical artifact. The primary causes and solutions are:

- Cause: Improper Sample Storage Temperature. Leaving plasma or serum samples at room temperature for extended periods leads to the enzymatic breakdown of phospholipids. Phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity increases, hydrolyzing the sn-2 ester bond of phosphatidylcholines (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE), generating lysophosphatidylcholines (LPC) and lysophosphatidylethanolamines (LPE) [29] [30].

- Solution: Process samples as quickly as possible after collection. If immediate processing is not possible, flash-freeze samples and store them at -80 °C to quench enzymatic activity. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [29] [30] [28].

- Cause: Acidic Extraction Conditions. While acidic conditions can improve the extraction efficiency of anionic lipids, using excessively high acid concentrations or prolonged extraction times can promote non-enzymatic hydrolysis of ester bonds, artificially inflating lysophospholipid levels [30].

- Solution: If using an acidic extraction protocol, strictly control the acid concentration and extraction time as defined during method validation [30].

Q2: We are observing significant lipid oxidation in our samples. How can we prevent this?

Lipid oxidation, particularly for polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), is a major concern. Prevention requires a multi-step approach:

- Cause: Exposure to Oxygen and Free Radicals. Auto-oxidation is a free radical chain reaction that is accelerated by the presence of oxygen and metal ions [28].

- Solution: Add antioxidants like butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) to the extraction solvents to quench free radicals [29] [28]. After preparation, store lipid extracts in airtight containers with an inert gas headspace (e.g., nitrogen) to minimize oxygen exposure.

- Cause: Exposure to Light and Heat. Photooxidation and thermally induced decomposition can generate peroxides and other secondary oxidation products [28].

- Solution: Perform extraction and handling steps under dimmed light or amber glass vials where possible. Keep samples on ice or in the cold whenever feasible. Store lipid extracts at -20 °C or lower in organic solvents with antioxidants [28].

Q3: What is the single most important step to ensure correct patient sample identification?

The most critical step is positive patient identification at the bedside using at least two permanent identifiers.

- Procedure: Confirm the patient's identity by checking their identification wristband and asking the patient to state their full name and date of birth. This must be cross-referenced with the specimen labels and request form [27] [31].

- Pitfall to Avoid: Never pre-label specimen tubes before collection, as this dramatically increases the risk of the wrong sample being placed into a pre-labeled tube [31]. Label the tube in the presence of the patient after venipuncture.

Standardized Protocols for Lipidomic Samples

Blood Collection and Initial Handling

The foundation of a reliable lipidomic analysis is proper blood collection.

- Fasting Status: For routine lipid profiling (cholesterol, triglycerides), fasting is no longer universally recommended as postprandial changes are often clinically insignificant. However, follow the specific requirements of your study protocol [27].

- Anticoagulants: Use the anticoagulant specified by your validated method. Be aware that calcium-chelating anticoagulants like EDTA and citrate can affect calcium-dependent lipid formation or degradation ex vivo [29].

- Order of Draw: Adhere to a strict order of draw to prevent cross-contamination between tubes. A typical sequence is: 1. Blood culture tubes, 2. Sodium citrate, 3. Serum gel tubes, 4. Lithium heparin, 5. EDTA tubes [27].

- Avoiding Haemolysis: Minimize tourniquet time, use an appropriately sized needle, and avoid transferring blood through a needle. Gently invert tubes to mix; never shake them, as haemolysis can alter analyte concentrations [27].

Sample Homogenization Techniques

Homogenization is critical for tissues and cells to ensure lipids from all compartments are equally accessible.

- Shear-Force Grinding: Using a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer or ULTRA-TURRAX in a cold solvent is a frequently used method [30].

- Cryogenic Crushing: For frozen tissues, crushing the material under liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar is effective. Be aware that frozen tissue may contain ice, which can distort results if normalized by frozen weight [30].

- Cell Disruption: Cells can be effectively disrupted using a pebble mill with beads or a nitrogen cavitation bomb, the latter of which avoids shear stress on biomolecules [30].

Lipid Extraction Methodologies

The choice of extraction method impacts the recovery of different lipid classes. The table below summarizes common techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Lipid Extraction Methods

| Method | Solvent System | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folch / Bligh & Dyer [30] | Chlorform/Methanol/Water | Considered the "gold standard"; high efficiency for many lipids. | Uses hazardous chloroform; lower phase is organic, making pipetting less convenient. | Broad-range lipidomics. |

| MTBE [30] | MTBE/Methanol/Water | Less toxic than chloroform; upper phase is organic, simplifying pipetting. Comparable efficiency to Folch. | May be less efficient for saturated fatty acids and plasmalogens [30]. | High-throughput, safer laboratory environment. |

| BUME [30] | Butanol/Methanol & Heptane/Ethyl Acetate | Designed for full automation in 96-well plates; avoids chloroform. | Requires specific solvent systems. | Automated, high-throughput screening. |

| Protein Precipitation (One-step) [29] [30] | e.g., Isopropanol, Methanol, Acetonitrile | Fast, robust; higher efficiency for very polar lipids (e.g., S1P, LPC) [30]. | Extracts more non-lipid compounds, increasing ion suppression and instrument contamination. | Rapid preparation for specific, polar lipid targets. |

Lipid Degradation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the primary pathways of lipid degradation that can occur during poor sample handling, leading to analytical artifacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table details key reagents used in the pre-analytical phase to maintain lipid stability and integrity.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Pre-analytical Lipidomics

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants [29] [28] | Quench free radicals to prevent lipid oxidation. | Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) is commonly added to extraction solvents. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails [29] | Stabilize proteinaceous factors; crucial when also measuring obesity-associated hormones (leptin, adiponectin). | Added to serum/plasma to prevent hormone degradation. |

| Chloroform [30] | Organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction. | Used in Folch and Bligh & Dyer methods. Hazardous; requires careful handling. |

| Methyl tert-Butyl Ether (MTBE) [30] | Less hazardous alternative to chloroform for liquid-liquid extraction. | Organic phase forms the upper layer, simplifying pipetting. |

| Internal Standards (IS) [29] | Correct for variability in extraction efficiency and instrument response. | Stable isotope-labeled analogs of target lipids should be added as early as possible in the protocol. |

| Acid (e.g., Formic Acid) [30] | Improve extraction efficiency of anionic lipids. | Must be used with strict control of concentration and time to avoid hydrolysis artifacts. |

In clinical lipidomics, the choice of analytical strategy is a fundamental decision that directly impacts the quality, reliability, and interpretability of your data. Whether your goal is hypothesis generation or rigorous validation, no single approach fits all research questions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of targeted, untargeted, and pseudo-targeted lipidomics strategies to help you select and optimize the right methodology for your clinical samples, supporting the broader standardization of lipidomic protocols in clinical research.

Core Strategy Comparison: Key Technical Specifications

The table below summarizes the primary technical characteristics of the three main lipidomics approaches to guide your initial selection.

| Feature | Untargeted Lipidomics | Targeted Lipidomics | Pseudo-targeted Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Comprehensive, hypothesis-generating exploration of all measurable lipids [32] [25] | Precise, accurate quantification of a predefined set of lipids [32] [33] | Combines broad coverage with improved quantification accuracy [32] |

| Analytical Focus | Global lipid profiling; discovery of novel biomarkers [32] | Validation of candidate biomarkers; absolute quantification [32] [25] | High-coverage lipid profiling and structural characterization [34] |

| Data Acquisition | DDA, DIA, IDA on HRMS (Q-TOF, Orbitrap) [32] | MRM/PRM on UPLC-QQQ MS or TQ MS [32] [33] | Integrated workflow from untargeted to targeted, sometimes with derivatization (e.g., PB reaction) [32] [34] |

| Throughput | Medium (longer chromatographic runs) | High (shorter, optimized runs) | Medium to High |

| Key Clinical Application | Biomarker discovery; pathophysiological mechanism investigation [32] [25] | Diagnostic biomarker validation; therapeutic monitoring [32] [33] | Comprehensive profiling and precise structural elucidation of complex samples [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting Guides

Study Design and Strategy Selection

Q: How do I choose the right strategy for my clinical research question?

A: Follow this decision workflow to align your research objective with the appropriate lipidomics strategy.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Discovery study yields too many insignificant lipid hits.

- Solution: Ensure adequate sample size and statistical power during the design phase. For case-control studies, preliminary power analysis is crucial [35].

- Problem: Targeted assay lacks coverage for unexpected but biologically relevant lipids.

- Solution: Consider a pseudo-targeted approach, which uses information from initial untargeted analyses to ensure high coverage and quantitative accuracy [32].

Sample Preparation and Lipid Extraction

Q: Which lipid extraction method should I use for my clinical sample type to ensure optimal recovery and reproducibility?

A: The optimal extraction protocol depends heavily on your sample matrix and the lipid classes of interest. The table below summarizes validated methods for common clinical sample types.

| Sample Type | Recommended Extraction Method(s) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum | Folch (Chloroform/Methanol) | Considered a "gold standard" for efficacy and reproducibility [36]. |

| Plasma/Serum | BUME (Butanol/Methanol) | Effective alternative to Folch; more amenable to automation [36]. |

| Liver / Intestine | MMC (Methanol/MTBE/Chloroform) or BUME | These methods are more favored for these specific tissues [36]. |

| Brain Tissue | Folch (Chloroform/Methanol) | Optimum for efficacy and reproducibility [36]. High in cholesterol and sphingolipids [25]. |

| Cultured Cells | Folch or MTBE (Methanol/MTBE) | MTBE offers ease of use (organic top layer) [36]. |

| General Use | MTBE (Methanol/MTBE) | Chloroform-free; organic phase is top layer, simplifying collection [36]. |

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Poor reproducibility and high technical variation in lipid recovery.

- Solution: Avoid monophasic methods like IPA and EE, which have shown poor reproducibility for many tissues [36]. Always add stable isotope-labeled internal standards (SIL-ISTDs) prior to extraction to correct for losses and matrix effects [33] [36].

- Problem: Low recovery of specific lipid classes (e.g., LysoPLs, Sphingolipids).

- Solution: The MTBE method can show significantly lower recoveries for lysophospholipids and sphingosines. This can be compensated for by the use of class-specific SIL-ISTDs [36].

Data Quality and Analytical Robustness

Q: How can I monitor and ensure data quality throughout my lipidomics workflow?

A: Implement a comprehensive quality control (QC) framework. Key steps include:

- Use Pooled QC (PQC) Samples: Create a pooled sample from all study samples and analyze it repeatedly throughout the batch to monitor instrument stability [37].

- Use Surrogate QC (sQC): Commercial reference plasma can be evaluated as a long-term reference and surrogate QC to assess analytical variation [37].

- Incorporate Extraction Quality Controls (EQCs): Use EQCs to monitor variability introduced during the sample preparation stage, effectively helping to mitigate batch effects [35].

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Batch effects are obscuring biological signals.

- Solution: Randomize sample analysis order and intersperse pooled QC samples throughout the run. Apply batch effect correction algorithms (e.g., Wave) during data pre-processing [35].

- Problem: Inaccurate quantification in untargeted lipidomics.

- Solution: For relative quantification in untargeted workflows, use class-specific internal standards. For absolute quantification, transition to a targeted MRM method, which provides higher accuracy and reproducibility [32] [33].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful lipidomics study relies on high-quality reagents and standards. The following table lists essential materials for setting up a robust clinical lipidomics workflow.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-ISTDs) | Correct for extraction efficiency, ionization suppression, and instrument variability; enable absolute quantification. | Critical: Add as early as possible in the workflow (prior to extraction). Use a mixture covering all lipid classes of interest [33] [36]. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Lipid extraction, mobile phase preparation. | Use high-purity solvents (e.g., Methanol, Chloroform, Isopropanol, MTBE) to minimize background noise and ion suppression [36]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Plates | Clean-up of lipid extracts; fractionation of lipid classes. | Useful for removing interfering compounds in complex samples (e.g., plasma) prior to MS analysis. |

| Pooled Quality Control (PQC) Material | Monitoring instrument stability and data quality throughout the analytical batch. | Prepare from a pool of all study samples or use a commercial surrogate QC (sQC) [37] [35]. |

| Chromatography Columns | Separation of complex lipid mixtures. | C18 columns are standard for reversed-phase LC-MS lipidomics. |

| Mass Spectrometers | Lipid detection, identification, and quantification. | Q-TOF / Orbitrap: For untargeted discovery [32]. Triple Quadrupole (TQ/UPLC-QQQ): For targeted quantification (MRM) [32] [33]. |

Standardizing lipidomic protocols for clinical samples requires a clear understanding of the strengths and limitations of each analytical strategy. The path to robust, reproducible data involves selecting the right approach for your biological question, employing a rigorously tested and well-controlled sample preparation protocol, and implementing a comprehensive QC system from sample collection to data processing. By adhering to these guidelines, researchers can generate high-quality, reliable lipidomic data that advances our understanding of disease mechanisms and accelerates biomarker discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How can I protect my LC-MS system from contamination when analyzing complex clinical lipidomic samples? Contamination can lead to signal suppression and increased instrument maintenance. To mitigate this:

- Use a Divert Valve: Install a valve between the HPLC and MS to direct only the peaks of interest into the mass spectrometer, diverting the solvent front and high organic wash portions of the gradient away from the ion source [38].

- Implement Robust Sample Preparation: For complex clinical matrices like plasma or serum, simple filtration may be insufficient. Techniques like solid-phase extraction (SPE) are often necessary to remove dissolved contaminants and endogenous matrix components that can foul the system [38].

2. What are the critical considerations for preparing mobile phases in LC-MS lipidomics? Mobile phase composition is crucial for robust ionization and preventing source contamination.

- Use Volatile Additives: Always use volatile buffers and acids, such as ammonium formate, ammonium acetate, or formic acid. Avoid non-volatile additives like phosphate buffers, as they will contaminate the ion source [38].

- Ensure High Purity: Use LC-MS grade solvents and additives of the highest possible purity to reduce chemical noise [39].

- Start with Low Concentrations: A good starting point is 10 mM for buffers or 0.05% (v/v) for acids. A general principle is: "If a little bit works, a little bit less probably works better" [38].

3. What is the first thing I should do when my LC-MS results seem abnormal? Your first step should be to run a benchmarking method [38]. This method consists of five replicate injections of a standard compound like reserpine on a method known to be working. If the benchmark performs as expected, the problem lies with your specific method or sample preparation. If the benchmark fails, the issue is likely with the instrument itself, guiding your troubleshooting efforts efficiently [38].

4. How often should I vent my mass spectrometer? You should avoid venting the instrument too frequently [38]. Mass spectrometers are most reliable when kept under stable vacuum. Venting increases wear and tear, with the turbo pump being particularly vulnerable. The rush of atmospheric air when re-establishing vacuum places significant strain on the turbo vanes and bearings, accelerating wear [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Solving Common Chromatographic Peak Problems

The following table outlines symptoms, potential causes, and solutions for issues with peak shape, which are critical for accurate identification and quantification in lipidomics.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Chromatographic Peak Anomalies

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing | Column overloading | Dilute the sample or decrease the injection volume [39]. |

| Contamination | Prepare fresh mobile phase, flush or replace the column, and use a matched guard column [39]. | |

| Interactions with active silanol sites | Add a volatile buffer (e.g., 10 mM ammonium formate) to your mobile phase to block active sites [39]. | |

| Peak Fronting | Sample solvent stronger than mobile phase | Dilute the sample in a solvent that matches (or is weaker than) the initial mobile phase composition [39]. |

| Column contamination or degradation | Flush the column following the manufacturer's procedure or replace it if regeneration fails [39]. | |

| Peak Splitting | Sample solvent incompatibility | Ensure the sample is dissolved in the same solvent composition (or weaker) as the initial mobile phase [39]. |

| Poor tubing connections | Check and ensure all tubing and ferrules are fully seated in the column and system ports [39]. | |

| Broad Peaks | Flow rate too low | Increase the mobile phase flow rate within method limits [39]. |

| Column temperature too low | Raise the column temperature [39]. | |

| Excessive extra-column volume | Use shorter tubing with a smaller internal diameter to minimize peak dispersion [39]. | |

| Decreased Sensitivity | Sample adsorption or system issues | For initial injections, condition the system with preliminary sample injections. For general loss, check for calculation errors, leaks, or incorrect injection volumes [39]. |

| Analyze a known standard. If the response is low, the issue is instrument-related; if normal, the problem is in sample preparation [39]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Baseline and System Pressure Issues

An unstable baseline or abnormal system pressure can indicate underlying problems.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Baseline and Pressure Issues

| Symptom | Pattern | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erratic Baseline | Irregular, noisy signal | Air bubble in the flow cell or a system leak | Purge the system with fresh mobile phase and check all fittings for leaks [39]. |

| UV detector lamp or flow cell failure | Change the detector lamp or clean/replace the flow cell [39]. | ||

| Cyclical Baseline | Regular, repeating pattern | Pump piston or seal issues | Perform routine maintenance on the pump, including replacing seals and pistons [39]. |

| High Backpressure | Sustained increase | Clogged frit or guard column | Replace the guard column. If pressure remains high, the analytical column may be clogged and require flushing or replacement [39]. |

| Blocked inline filter or tubing | Check and clean or replace the system’s inline filter and capillary tubing [39]. |

Workflow and Logic Diagrams

Troubleshooting Logic

Method Development & Optimization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Clinical Lipidomics LC-MS

| Reagent/Material | Function in LC-MS Workflow | Technical Notes for Lipidomics |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Provides low background signal; reduces ion source contamination. | Essential for high-sensitivity detection of low-abundance lipids. |

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate | Volatile buffer salts for controlling mobile phase pH. | Promotes stable ionization; 10 mM is a standard starting concentration [38] [39]. |

| Formic Acid | Volatile acidic additive to promote positive ionization. | A good alternative to TFA, which can cause significant signal suppression [38]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Kits | Clean-up and pre-concentration of lipid samples from complex matrices. | Critical for removing phospholipids and other interferents from clinical samples [38]. |

| Guard Column | Protects the analytical column from contaminants and particulates. | Should match the stationary phase of the analytical column; requires regular replacement [39]. |

| Divert Valve | Directs HPLC flow to waste or MS. | Preserves ion source by diverting non-analyte portions of the run (e.g., solvent front) [38]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I use a single solvent system for all my sample types? Different biological matrices have varying compositions of polar and non-polar metabolites, as well as different physical properties. For instance, plasma and liver tissue require distinct optimization strategies. A biphasic CHCl₃/MeOH/H₂O method is suitable for polar and lipid extraction from plasma after NMR-based metabolomics analysis. In contrast, for liver tissue, a two-step extraction involving CHCl₃/MeOH followed by MeOH/H₂O is recommended due to its complex structure and lipid diversity [40].

FAQ 2: What is the impact of using multiple analytical platforms on my limited sample? Using multiple platforms (e.g., NMR and various UHPLC-MS setups) provides a more unbiased and comprehensive metabolic profile. The challenge of limited sample material is addressed by developing sequential extraction protocols that allow for multi-platform analysis from a single sample. This approach enables polar metabolite profiling via NMR and UHPLC-MS, and lipidomics from the resuspended dried lipid extract [40].

FAQ 3: How critical is standardized nomenclature for my lipidomics data? Standardized nomenclature is crucial for data reproducibility, sharing, and comparative analysis. Inconsistent naming is a significant source of confusion. It is recommended to use the LIPID MAPS classification system and shorthand notation, which have been widely adopted by journals and repositories to ensure clarity and enable meta-analyses across different studies [41] [42].

FAQ 4: Where should I deposit my lipidomics data? Large lipidomics datasets should be deposited in recognized repositories to support future data mining and integration. Recommended repositories include the Metabolomics Workbench and MetaboLights. Using these resources with the LIPID MAPS nomenclature facilitates data standardization and reuse in systems biology [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Recovery of Both Polar and Non-Polar Metabolites

Problem: The extraction protocol fails to efficiently isolate a broad range of metabolites, leading to low coverage.

Solution: Implement an optimized, sequential extraction protocol tailored to your sample type.

- For Plasma Samples: Use a biphasic CHCl₃/MeOH/H₂O system. This method is optimal in terms of the number of annotated metabolites, reproducibility, and sample conservation. It allows for sequential analysis of the same sample [40].

- For Liver or Other Tissues: Employ a two-step extraction.

- First, extract with CHCl₃/MeOH for lipids.

- Follow with MeOH/H₂O for polar metabolites. The dried lipid extract can be resuspended for lipidomics, while the polar extract can be used for further untargeted profiling [40].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Lipid Identification and Nomenclature

Problem: Lipid names are inconsistent across datasets, hampering comparison with other studies.

Solution: Adhere to international standards for lipid identification and reporting [41] [42].

- Use LIPID MAPS: Apply the LIPID MAPS classification system and the updated shorthand notation for reporting lipid structures.

- Match Authentic Standards: For targeted assays, confirm that the retention time of lipids in your biological samples matches that of synthetic standards to avoid misidentifying isomers.

- Report Level of Identification: Clearly state the level of structural detail confirmed by your mass spectrometric data (e.g., based on accurate mass, retention time, or MS/MS fragmentation).

- Follow Reporting Guidelines: Consult the guidelines developed by the Lipidomics Standard Initiative (LSI) for major lipidomics workflows [43].

Issue 3: Challenges in Quantitative Accuracy

Problem: Quantitative results vary due to methodological inconsistencies.

Solution: Implement rigorous quantitative practices [41].

- Use Internal Standards: Utilize stable isotope-labeled internal standards for absolute quantitation where possible. For relative quantitation, ensure the experimental series is well-controlled.

- Chromatographic Resolution: Ensure peaks are properly resolved. For targeted methods, chromatographic peaks should be Gaussian-shaped with a signal-to-noise ratio of at least 5:1 for quantification, and have 6-10 data points across the peak.

- Validate with Raw Data: Perform limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) determinations using raw, unsmoothed data. Manually inspect raw data chromatograms to verify software-generated assignments.

Experimental Protocols for Clinical Samples

Optimized Sequential Extraction for Multi-Platform Analysis

This protocol enables NMR-based metabolomics and UHPLC-MS-based lipidomics from a single sample of plasma or liver tissue [40].

Protocol for Plasma

- Sample Preparation: Start with a single plasma sample.

- NMR Analysis: First, analyze the native or minimally prepared sample using

¹H NMR. - Biphasic Extraction: Following NMR, subject the sample to a biphasic extraction using CHCl₃/MeOH/H₂O.

- Phase Separation: Separate the polar (aqueous) and non-polar (organic) phases.

- Multi-Platform Analysis:

- Analyze the polar phase for metabolomics using UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS.

- Analyze the non-polar phase for lipidomics using UHPLC-QqQ MS.

Protocol for Liver Tissue

- Sample Preparation: Start with a single liver tissue sample.

- NMR Analysis: Begin with

¹H NMRanalysis. - Two-Step Sequential Extraction:

- Step 1 (Lipid-rich fraction): Extract with CHCl₃/MeOH. Resuspend the dried extract for lipidomics analysis (e.g., via UHPLC-MS).

- Step 2 (Polar metabolite fraction): Subsequently, extract the residue with MeOH/H₂O. Use this polar extract for further untargeted metabolomics by UHPLC-Q-Orbitrap MS.

Table 1: Comparison of optimized extraction methods for plasma and liver tissue.

| Sample Type | Recommended Method | Key Advantages | Sequential Analysis Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Biphasic CHCl₃/MeOH/H₂O | Comprehensive coverage of polar and lipid metabolites; high reproducibility; sample-conserving [40]. | 1. NMR → 2. Polar & Lipid UHPLC-MS |

| Liver Tissue | Two-step: CHCl₃/MeOH followed by MeOH/H₂O | Effective for complex tissue; allows separate, in-depth analysis of lipid and polar fractions [40]. | 1. NMR → 2. Lipidomics (from 1st extract) → 3. Metabolomics (from 2nd extract) |

Key Data Reporting Standards

Adhering to community-developed guidelines is essential for the quality and reproducibility of lipidomics data in clinical research [41].

Table 2: Essential guidelines for reporting lipidomics data.

| Aspect | Minimum Reporting Standard | Example/Additional Detail |

|---|---|---|

| Nomenclature | Use LIPID MAPS classification and shorthand notation [42]. | e.g., PC(16:0_18:1) for a glycerophosphocholine. |

| Authentic Standards | Confirm retention time matches synthetic standards for positive identification [41]. | Critical for discriminating between lipid isomers. |

| Peak Quality | Report signal-to-noise, data points across a peak, and provide raw chromatograms [41]. | S/N ≥5:1 for LOQ; 6-10 data points per peak. |

| Quantitation | Specify whether absolute or relative; describe internal standards used [41]. | Stable isotope dilution is the gold standard for absolute quantitation. |

| Data Deposition | Deposit in recognized repositories (e.g., Metabolomics Workbench) [41]. | Use LIPID MAPS nomenclature upon deposition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key reagents, standards, and software for robust lipidomics.

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) & Methanol (MeOH) | Primary solvents for biphasic extraction, effectively separating polar and non-polar metabolites [40]. |

| Synthetic Lipid Standards | Authentic chemical standards for validating lipid identification and retention time, and for quantitative calibration [41]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Added to samples for correcting losses during preparation and enabling absolute quantitation via mass spectrometry [41]. |

| LIPID MAPS Database | The primary curated resource for lipid structures, classification, nomenclature, and mass spectrometric data [42]. |

| Lipid Data Analyzer (LDA) | Open-source software for automated processing and quantification of lipidomic MS data [41]. |

| Metabolomics Workbench | A public repository for depositing, sharing, and discovering metabolomics and lipidomics data [41]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Optimized Lipidomics Workflow

Lipid Identification & Reporting Standards

Overcoming Analytical Challenges and Data Complexity

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying Your Missing Data Mechanism