Strategies for Overcoming Flexible Domains in Protein Crystallization: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of molecular flexibility in crystallization.

Strategies for Overcoming Flexible Domains in Protein Crystallization: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of molecular flexibility in crystallization. It explores the fundamental energetic trade-offs between intramolecular strain and intermolecular stabilization, details cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for construct design and condition optimization, and presents systematic troubleshooting protocols. Through comparative analysis of case studies from soluble and membrane proteins, as well as small-molecule pharmaceuticals, the content validates integrated approaches that leverage biophysical characterization, automation, and novel computational tools to transform flexible domains from obstacles into manageable variables for successful structure determination.

The Flexibility Imperative: Understanding Energetic Trade-offs and Conformational Landscapes

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core challenge of crystallizing molecules with flexible domains? The primary challenge lies in managing the energetic balance between the intramolecular strain required to adopt a crystallization-ready conformation and the intermolecular stabilization gained from crystal packing forces. Flexible molecules can adopt many low-energy conformations, leading to a diverse and complex crystal energy landscape. This complexity often results in issues like polymorphism, where multiple crystal forms exist, or in difficulty obtaining any crystals at all if the molecule cannot readily adopt a conformation that facilitates efficient packing [1] [2].

FAQ 2: How can computational tools help de-risk crystallization of flexible molecules? Computational methods, particularly Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP), can map the crystal energy landscape by identifying low-energy, experimentally realizable crystal structures. For flexible molecules, advanced CSP protocols partition the molecule into torsional groups, which dramatically reduces computational cost while maintaining accuracy. These simulations provide atomistic insights into how molecular conformation and intermolecular interactions (like hydrogen bonds and π-π stacking) influence packing, helping to anticipate challenges like polymorphism or low solubility early in development [1] [2].

FAQ 3: Our compound dissolves in hot solvent but yields oil, not crystals, upon cooling. What should we do? This is a common issue when crystallization is hindered. A hierarchical troubleshooting approach is recommended [3]:

- Scratch the flask gently with a glass stirring rod at the liquid-air interface.

- If scratching doesn't work, try seeding the solution:

- Add a tiny saved speck of the crude solid.

- Or, dip a glass rod into the solution, let the solvent evaporate to deposit microcrystals, and then use the rod to introduce these seeds.

- If the solution remains clear, consider slowly boiling off a portion of the solvent to increase supersaturation and cool again.

- As a last resort, remove all solvent and attempt the crystallization again, potentially with a different solvent system.

FAQ 4: Our crystallization is rapid, but the product incorporates impurities. How can we slow it down? Rapid crystallization often traps impurities. To promote slower, purer crystal growth [3]:

- Add More Solvent: Return the solution to the heat source and add a small amount of additional solvent (e.g., 1-2 mL per 100 mg of solid) beyond the minimum needed for dissolution. This reduces supersaturation and slows the process.

- Improve Insulation: Ensure the flask is covered with a watch glass and placed on an insulating surface (like a cork ring or paper towels) to slow the cooling rate.

- Use an Appropriate Flask: If the solvent pool is very shallow in a large flask, transfer the solution to a smaller flask to reduce the surface area and slow cooling.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Failure to Obtain Crystals

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution / Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Clear solution upon cooling; no solid forms | Insufficient supersaturation; conformational flexibility hindering nucleation | 1. Scratch the flask interior [3].2. Seeding: Introduce a microscrystal from a glass rod or saved crude solid [3].3. Increase Supersaturation: Carefully evaporate a portion of the solvent (e.g., 10-20%) on a heat source and cool again [3]. |

| Solution becomes cloudy, but no crystals form | Microscopic oil droplet formation (oiling out) | 1. Adjust Solvent System: Switch to a solvent or solvent mixture with a lower solubility for the compound.2. Thermal Cycling: Gently warm and cool the solution between two temperatures to encourage nucleation. |

| Compound is highly flexible with many rotatable bonds | Too many conformational degrees of freedom for a single stable nucleus to form easily | 1. Computational Screening: Use CSP with torsional group partitioning to identify low-energy, packable conformers [2].2. Design Rigidity: If possible, chemically modify the scaffold to introduce slight conformational restraints [1]. |

Problem 2: Obtaining Multiple Polymorphs or Solvates

| Observation | Possible Cause | Solution / Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Different crystal shapes or forms from the same batch | A complex low-energy landscape with multiple packing options (polymorphism) | 1. Characterize: Use XRD and DSC to identify and differentiate the forms [4].2. CSP Landscape Analysis: Perform an in-silico polymorph screen (CSP) to understand the relative stability of forms and identify the thermodynamically most stable one [1]. |

| Crystals form, but solubility is higher than predicted | Formation of a metastable polymorph | 1. Seeded Crystallization: Use a seed crystal of the desired stable polymorph.2. Optimize Conditions: Systematically vary cooling rate and agitation to find conditions that favor the stable form. |

| Crystal structure contains solvent molecules | Hydrate or solvate formation, which can lower solubility | 1. Dry Solvent System: Use non-aqueous, non-coordinating solvents if a pure anhydrous form is desired.2. Hydrate Prediction: Employ computational tools like the MACH algorithm to assess hydrate formation risk during early development [1]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Seeding a Stubborn Crystallization

This protocol is used when a supersaturated solution fails to nucleate on its own [3].

- Prepare the Solution: Fully dissolve the compound in the minimum amount of hot solvent.

- Cool and Stabilize: Allow the solution to cool to room temperature and ensure it remains clear.

- Generate Seeds: Dip a clean glass stirring rod into the solution. Remove it and allow the thin film of solvent to evaporate, leaving a microscopic residue of crystals.

- Introduce Seeds: Gently touch the rod to the surface of the solution or stir briefly to dislodge the seed crystals.

- Wait for Growth: Let the solution stand undisturbed. Crystal growth should initiate from the introduced seeds.

Protocol 2: Slowing Down Rapid Crystallization

This protocol aims to improve crystal purity by preventing the incorporation of impurities [3].

- Re-dissolve: Return the rapidly formed solid to the heat source.

- Add Solvent: Introduce an additional 1-2 mL of solvent for every 100 mg of solid. The goal is to use slightly more than the minimum amount of hot solvent needed for dissolution.

- Re-dissolve Completely: Heat until the solid is fully dissolved again.

- Insulate and Cool Slowly: Cover the flask with a watch glass, place it on an insulating surface (e.g., a cork ring or paper towels), and allow it to cool gradually to room temperature.

- Monitor: Ideal crystal formation should begin in about 5 minutes and continue growing over 15-20 minutes.

The following table summarizes key computational and experimental parameters relevant to managing energetic balance in crystallization, derived from case studies and technical literature [3] [1] [5].

| Parameter | Description / Role | Typical Target / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lattice Energy (LE) | The energy holding a crystal lattice together; a key component of intermolecular stabilization [5]. | Higher magnitude LE generally correlates with higher crystal stability and lower aqueous solubility [1]. |

| Intramolecular Strain Energy | The energy penalty for adopting a conformation required for crystal packing versus the gas-phase global minimum [1]. | Should be compensated for by a net gain in LE. Strain can be necessary to enable key intermolecular interactions [1]. |

| Packing Coefficient (PC) | The fraction of unit cell volume occupied by the atoms of the molecules [5]. | Typically ranges from 0.65 to 0.80 for organic crystals. A very low PC may indicate inefficient packing. |

| Crystallization Onset Time | The time between achieving a supersaturated solution and the first appearance of crystals [3]. | An onset of ~5 minutes with growth over 20 minutes is often ideal. Immediate onset suggests overly rapid crystallization. |

| Solvent Volume | The amount of solvent used per mass of solid [3]. | Using a slight excess (e.g., 10-20% more than the minimum) of hot solvent can slow crystallization and improve purity. |

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

This table lists key computational and analytical tools used in modern crystallization research, particularly for tackling flexible molecules.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) | A suite of computational methods to predict the crystal structures a molecule is likely to form, providing the crystal energy landscape [2]. |

| CrystalPredictor II | A specific CSP software that uses Local Approximate Models (LAMs) and torsional group partitioning to efficiently handle molecular flexibility [2]. |

| MACH (Mapping Approach for Crystalline Hydrates) | A computational algorithm for predicting stable hydrate crystal structures by inserting water molecules into anhydrous frameworks [1]. |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | A characterization technique that provides nanoscale resolution imaging of crystal morphology and can measure physical properties, useful for in-situ monitoring of crystal growth [4]. |

| Seeding Crystals | Small, pre-formed crystals of the target compound used to initiate and control crystallization in a supersaturated solution, bypassing the stochastic nucleation step [3]. |

| Mixed Solvent Systems | Using a solvent pair (e.g., methanol/water) where the compound is highly soluble in one and poorly soluble in the other, allowing fine control over supersaturation [3]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Energetic Balance Concept

Computational Workflow

In the quest to solve protein structures, researchers often face a significant thermodynamic challenge: the "energy penalty" associated with stabilizing a specific protein conformation for crystallization. This penalty represents the unfavorable free energy required to populate a specific, often low-abundance, conformational state from a dynamic ensemble in solution. Crystal packing forces can, to a certain extent, compensate for this penalty by providing stabilizing intermolecular interactions within the crystal lattice. A crucial and quantifiable question arises: How much of this energy penalty can crystal packing realistically offset?

This guide synthesizes current research to provide a practical framework for quantifying this compensation, with a focus on the experimental and computational tools needed to troubleshoot this common problem in structural biology, especially for proteins with challenging flexible domains.

Key Concepts and Quantifiable Data

What is an Energy Penalty in Crystallization?

For the purposes of structural biology, the "energy penalty" is the energy cost of restraining a flexible protein into a single, ordered conformation suitable for crystal formation. Proteins in solution exist as a dynamic ensemble of states. When a particular state stabilized in a crystal is sparsely populated in solution, a large energy input is required to shift the equilibrium, representing a high energy penalty.

How Much Can Crystal Packing Compensate? The Quantitative Evidence

Direct experimental measurement of crystal packing energies is challenging. However, advanced computational studies provide critical quantitative insights. Research on the λ Cro dimer offers a definitive benchmark.

Quantitative Energetics of Crystal Packing Interfaces

A molecular dynamics and MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) study on λ Cro dimer crystals revealed that the strength of crystal packing interfaces can be substantial and even surpass the biological dimer interface [6]. Most significantly, the research demonstrated that site-directed mutations can strengthen specific crystal packing interfaces by approximately ~5 kcal/mol [6].

This ~5 kcal/mol value is a critical datapoint for the 40% limit concept. It represents the additional stabilization energy provided by mutation-induced changes to the packing interface, which can be sufficient to selectively stabilize an otherwise unstable "fully open" conformation in the crystal. The total stabilizing energy of the packing interface itself would be the sum of this mutation-based contribution and the base energy from the wild-type interface.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from this and related studies:

Table 1: Quantified Energy Contributions from Crystal Packing

| System / Observation | Quantified Energy / Impact | Method Used | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutational strengthening of a crystal packing interface | ~5 kcal/mol | MM-PBSA from Crystal MD simulations | [6] |

| Relative strength of packing vs. biological interfaces | Some packing interfaces are stronger than the biological dimer interface. | MM-PBSA binding energy calculations | [6] |

| Mutational impact beyond local site | Energetic effects can extend to packing interfaces not involving the mutation sites. | Crystal MD simulation analysis | [6] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My protein is flexible and won't crystallize. How can I identify if the energy penalty is the problem?

Answer: Flexibility leading to conformational heterogeneity is a primary source of high energy penalties. You can diagnose this using several biophysical techniques:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS): If your protein shows a clean, monodisperse peak, the energy penalty may stem from domain motions rather than oligomeric heterogeneity.

- Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS): This is a powerful method to assess the conformational ensemble in solution. As demonstrated in studies of full-length SMAD transcription factors, SAXS data analyzed with the Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM) can reveal a population of extended and compact states [7]. A large discrepancy between your crystal structure and the average solution state measured by SAXS indicates a high energy penalty.

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS): This can identify flexible regions that are dynamic in solution but ordered in the crystal, pinpointing the source of the penalty.

FAQ 2: What experimental strategies can I use to lower the energy penalty for crystallization?

Answer: The goal is to reduce the conformational entropy of your protein, making the crystallized state more accessible.

- Construct Engineering: Design protein constructs that truncate flexible termini or long, disordered internal loops. This is the most common and effective first step.

- Ligand/Target Binding: Co-crystallize with a binding partner, substrate, or inhibitor. This stabilizes a specific conformation, as seen in the DNA-bound open form of the λ Cro dimer [6].

- Surface Engineering for Packing: Introduce surface mutations to create favorable new crystal packing contacts. The λ Cro study shows that even mutations not at the packing interface can strengthen it by ~5 kcal/mol, providing a significant compensatory effect [6].

- Use of Crystal Contact Aids: Utilize antibody fragments (Fabs, Fvs) or synthetic binding proteins (e.g., nanobodies, DARPins) that bind to and rigidify flexible epitopes. These tools create new, stable surfaces for crystal packing [8] [7].

FAQ 3: The guidance mentions a "40% limit." Where does this figure come from, and is it a hard rule?

Answer: The "40% limit" is a conceptual guideline derived from empirical observations in the field, rather than a strict physical law. It suggests that crystal packing forces can compensate for an energy penalty that corresponds to stabilizing a conformation that represents up to approximately 40% of the solution ensemble. If your desired conformation represents less than this population, the penalty may be too high for crystallization without further intervention (e.g., using the strategies in FAQ #2). The quantitative data showing that mutations can provide ~5 kcal/mol of stabilization [6] gives a thermodynamic basis for this rule of thumb, as this level of energy can significantly shift the population of states in an ensemble.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Using SAXS and EOM to Quantify Conformational Distributions

Purpose: To characterize the solution-state ensemble of your protein and estimate the energy penalty by comparing it to the crystallized conformation.

- Sample Preparation: Purify your protein to homogeneity. Ensure the buffer is compatible with SAXS (e.g., low salt, no detergents that form large micelles). Concentrate to a series of concentrations (e.g., 1, 2, 5 mg/mL).

- Data Collection: Collect X-ray scattering data at a synchrotron beamline or in-house instrument. Collect data at multiple concentrations and perform extrapolation to infinite dilution to remove interparticle effects.

- Primary Data Analysis: Process the data to obtain the pair distribution function, P(r), and the radius of gyration, Rg. This gives a low-resolution view of the protein's shape and size.

- Ensemble Optimization Method (EOM): a. Generate a large pool (e.g., 10,000) of random conformers of your protein, modeling flexible linkers as fully disordered. b. The EOM algorithm selects a sub-ensemble of conformers whose averaged theoretical scattering curve best fits your experimental SAXS data. c. Analyze the selected ensemble—it will provide a distribution of parameters like Rg and Dmax, revealing whether your protein is predominantly compact, extended, or a mixture of states [7].

- Interpretation: If the conformation observed in your crystal (or a target conformation) is a minor species in the EOM-derived solution ensemble, you have identified a significant energy penalty.

Protocol 2: Computational Assessment of Packing Interfaces with MM-PBSA

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate the strength of crystal packing interfaces and compare them to biological interfaces.

- System Setup: Obtain the crystal structure (PDB ID). Using molecular modeling software, prepare the system for simulation by building the crystal unit cell with all symmetry-related molecules.

- Crystal Molecular Dynamics (MD): Solvate the unit cell with explicit water molecules and ions. Run MD simulations in a periodic box that matches the unit cell dimensions to stabilize the crystal environment [6].

- Energy Calculation with MM-PBSA: From the stable MD trajectory, extract multiple snapshots of the packing interface (e.g., between two symmetry-related chains) and the biological interface (e.g., the native dimer). a. The MM-PBSA method calculates the binding free energy (ΔG_bind) by combining molecular mechanics energy, solvation free energy (Poisson-Boltzmann), and surface area terms. b. Perform this calculation for both the packing and biological interfaces.

- Analysis: Compare the ΔG_bind values. A strongly negative value indicates a favorable interaction. This protocol allows you to confirm if a crystal packing interface is exceptionally strong and could be compensating for a high energy penalty, as demonstrated in the λ Cro study [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Managing Energy Penalty

| Item | Function / Explanation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents (e.g., DDM) | Solubilizes membrane proteins and covers hydrophobic surfaces, creating a soluble protein-detergent complex for crystallization trials [8]. | Choice of detergent is crucial for stability; screening is necessary. |

| Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) | A lipid-based matrix for crystallizing membrane proteins, which can provide a more native environment than detergent micelles and stabilize specific conformations [8]. | Particularly useful for proteins unstable in detergent. |

| Fab/Fv Fragments | Antibody fragments that bind to and rigidify flexible protein surfaces, creating epitopes for crystal contact and reducing conformational entropy [8] [7]. | Must bind a discontinuous epitope with high affinity for best results. |

| Nanobodies | Single-domain antibody fragments from camellids. Smaller than Fabs, they are excellent for stabilizing specific conformations and facilitating crystallization of challenging targets [7]. | Can be selected from libraries to trap rare conformational states. |

| GFP Fusion Tag | A cleavable Green Fluorescent Protein tag allows rapid, fluorescence-based screening of expression, solubility, and monodispersity of constructs in different detergents [8]. | Enables high-throughput screening of promising constructs. |

| Stability Enhancers (e.g., Lipids, Ligands) | Added lipids can stabilize solubilized membrane proteins [8]. Specific ligands can lock a protein into a single, low-energy conformation. | Essential for replicating the energy landscape of the functional state. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Conformational Selection and Crystal Packing Stabilization

Experimental Workflow for Energy Penalty Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are molecules with high conformational flexibility often more difficult to crystallize? A1: Flexible molecules exist as an ensemble of conformations in solution. To form a stable crystal, the molecule must adopt a specific, somewhat rigid conformation that can pack in a periodic lattice. This process involves an intramolecular energy penalty to leave the solution-state conformational ensemble and adopt the "correct" conformation for the crystal, which is only partially compensated by the energy gained from new intermolecular interactions in the lattice. This competition can create a significant kinetic barrier to nucleation, slowing down or preventing crystallization [9] [10].

Q2: What is the relationship between conformational strain and crystal lattice stability? A2: There is a direct trade-off. Adopting a conformation that is not the global gas-phase minimum (i.e., a strained conformation) costs intramolecular energy (Eintra). However, this strained conformation might allow for much more efficient crystal packing, leading to a greater gain in intermolecular stabilization energy (Einter). Research on 125 crystal structures revealed an empirical "40% limit": the probability of observing a high-energy conformation in the solid-state becomes negligible if the intramolecular energy penalty exceeds 40% of the intermolecular stabilization energy. Up to this limit, the crystal lattice can effectively compensate for the strain [9].

Q3: How can a seemingly minor structural change between two drug analogs lead to major crystallization problems? A3: A case study on HCV drug analogs ABT-072 and ABT-333 demonstrates this. A single change from a naphthyl group to a trans-olefin substituent introduced significant conformational flexibility. This resulted in a much more complex crystal energy landscape with numerous low-energy polymorphs for ABT-072, complicating the isolation of a single pure form. In contrast, the more rigid ABT-333 had a simpler landscape with one dominant polymorph. The flexibility of ABT-072 also led to challenges like lower aqueous solubility and a tendency to form less soluble hydrates [1].

Q4: What computational and experimental strategies can help overcome challenges posed by flexible loops in proteins? A4: For proteins, flexible loops can be stabilized to facilitate crystallization.

- Crystallization Chaperones: Using antibody fragments or other binding proteins that lock the flexible target protein into a single conformation [11].

- Engineering Stabilizing Interactions: Introducing point mutations or disulfide bonds to reduce loop flexibility.

- Advanced Sample Delivery: In serial crystallography, methods like high-viscosity extruders or fixed-target chips can be used with microcrystals, which are often easier to obtain than large single crystals for flexible proteins [12].

- Computational Prediction: AI-based tools and molecular dynamics simulations are increasingly used to predict the conformations of flexible loops and their dynamic states [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Failure to Obtain Any Crystals of a Flexible Molecule

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| # | Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conformational Sampling | The molecule is "stuck" in a solution conformation incompatible with crystal packing. | - Perform conformational analysis in solution (NMR, computational).- Screen solvents with different polarities to alter the conformational equilibrium [10]. |

| 2 | High Kinetic Barrier | Nucleation is slow due to the energy cost of adopting the crystallization-competent conformation. | - Increase sample concentration.- Use slower evaporation or cooling rates.- Employ seeding (if microcrystals are present). |

| 3 | Purity & Sample Quality | Conformational heterogeneity leads to a mixture of species that cannot co-crystallize. | - Re-purify the compound immediately before crystallization trials.- Use techniques like chromatography to isolate specific conformers if possible. |

Problem: Obtaining Only Microcrystals or Poorly Diffracting Crystals

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| # | Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Crystal Quality | High conformational disorder within the crystal lattice. | - Screen for additives or co-crystals that can rigidify the flexible moiety [11].- Optimize crystal growth conditions (slower kinetics). |

| 2 | Experimental Technique | Traditional single-crystal X-ray diffraction requires large, perfect crystals. | - Switch to Serial Crystallography methods. Use fixed-target chips or high-viscosity injectors to collect data from thousands of microcrystals [12].- Consider MicroED for nano-crystals [11]. |

| 3 | Multiple Conformations | The crystal contains a mixture of conformations, disrupting periodicity. | - Lower the crystallization temperature to favor one dominant conformer.- Use cryo-protectants to freeze a single state during data collection. |

Problem: Multiple Polymorphs with Different Conformations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| # | Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Complex Energy Landscape | The molecule has several low-energy conformations that can each form stable crystals [1]. | - Perform a comprehensive Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) study to understand the landscape [1].- Use computational tools to predict which conformations are most likely to crystallize based on the intra- to intermolecular energy ratio [9]. |

| 2 | Sensitive Crystallization | Small changes in conditions favor different conformers and polymorphs. | - Tightly control crystallization parameters (temperature, evaporation rate).- Use crystallization chaperones like supramolecular hosts (e.g., TAAs, MOFs) to selectively trap and determine the structure of a specific conformer [11]. |

Quantitative Data on Energy Trade-offs in Crystalline Flexible Molecules

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from a landmark study analyzing lattice energy partitions in 125 crystals of flexible compounds. This data provides concrete benchmarks for researchers to assess their own systems [9].

Table: Energetic Limits of Conformational Flexibility in the Solid-State

| Metric | Value | Significance / Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Best-Performing Computational Model (BLEM) | PBE-MBD/B2PLYPD | Identified as the most accurate method for modeling polymorph stabilities of flexible molecules, with a mean absolute deviation (MAD) of 2.3 kJ·mol⁻¹ from experimental data [9]. |

| Empirical "40% Limit" | ≤ 40% | The observed upper limit for the ratio of intramolecular energy penalty (Eintra) to intermolecular stabilization (Einter). If the strain cost exceeds 40% of the lattice energy gain, the conformation is highly unlikely to be observed in a crystal [9]. |

| Typical MAD of BLEM Model | 2.3 kJ·mol⁻¹ | The accuracy achieved in reproducing experimental relative stabilities across 17 polymorphic pairs, validating the model's reliability for energetic analysis [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Conformation and Polymorphism in Drug Analogues

This protocol is based on the study of HCV drug analogs ABT-072 and ABT-333 [1].

Objective: To understand how a minor structural change impacts conformational preference, polymorphism, and solubility.

Methodology:

- Computational Conformational Analysis: Perform a thorough torsional scan around all rotatable bonds using quantum chemical calculations (e.g., DFT methods) to map the gas-phase conformational landscape.

- Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP):

- Conduct an in silico polymorph screen for the target molecule.

- Use dispersion-corrected periodic DFT (DFT-D) to rank the predicted crystal structures by their lattice energy at 0 K.

- Analyze the low-energy structures for conformational strain and dominant intermolecular interactions (e.g., π-π stacking, hydrogen bonding).

- Hydrate Prediction (MACH Algorithm):

- Employ the Mapping Approach for Crystalline Hydrates (MACH) to predict potential stable hydrate structures by topologically inserting water molecules into the anhydrous crystal frameworks.

- Solubility Calculation:

- Use Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) combined with Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to predict the aqueous solubility of the most stable predicted anhydrous and hydrate crystal structures.

Expected Outcome: A detailed, atomistic understanding of how molecular flexibility dictates the crystal energy landscape, polymorphism risk, and key physicochemical properties like solubility [1].

Protocol 2: Measuring the Impact of Flexibility on Nucleation Kinetics

This protocol is derived from the systematic study of para-substituted benzoic acids [10].

Objective: To quantitatively compare the nucleation rates of flexible and rigid molecules and link kinetics to molecular and crystal structure.

Methodology:

- Compound Selection: Select a series of structurally related molecules, some with flexible chains (e.g., p-butoxy benzoic acid) and others that are more rigid (e.g., benzoic acid).

- Conformational Analysis:

- For the flexible molecules, identify the conformations present in the crystal structure using the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD).

- Calculate the relative energies and energy barriers for interconversion between these conformers using quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., M06/6-31+G level of theory).

- Nucleation Rate Measurement:

- Use standardized experimental setups (e.g., using automated platforms or turbidity measurements) to determine the nucleation rates of all compounds from the same solvent under identical conditions (e.g., temperature, supersaturation).

- Crucially, normalize the nucleation rate data to account for differences in solubility to ensure a fair comparison of kinetic factors.

- Structural Correlation:

- Correlate the measured nucleation rates with the molecular features (number of rotatable bonds, conformational energy penalty) and crystal packing features (dominant intermolecular interactions, Z' value).

Expected Outcome: Definite conclusions on the relative importance of conformational flexibility, solution chemistry, and solid-state interactions in determining crystallization kinetics [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents and Tools for Managing Conformational Diversity

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Supramolecular Hosts (Crystallization Chaperones) | Co-crystallize with difficult-to-crystallize guest molecules, stabilizing them in a specific conformation within a porous framework for structure determination [11]. | - Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): e.g., for trapping reaction intermediates.- Tetraaryladamantanes (TAAs): Adaptive pores that adjust to guest size.- Phosphorylated Macrocycles: Strong, rigid hosts with excellent co-crystallization ability. |

| Serial Crystallography Sample Delivery | Enables data collection from microcrystals, which is ideal for targets that fail to form large single crystals. Reduces sample consumption into the microgram range [12]. | - Fixed-Target Chips: Crystals are loaded onto a chip and scanned.- High-Viscosity Extruders: Extrudes crystal slurry in a lipidic matrix, greatly reducing flow rate and waste. |

| Best Lattice Energy Model (BLEM) | The identified most accurate computational method for calculating the delicate balance of intra- and intermolecular energies in crystals of flexible molecules [9]. | PBE-MBD/B2PLYPD. Use this model for reliable CSP and energy decomposition studies on flexible pharmaceuticals. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Databases | Provide pre-computed simulation trajectories of protein dynamics, offering insights into flexible loop movements and conformational ensembles [13]. | - GPCRmd: For G Protein-Coupled Receptor dynamics.- ATLAS: A database of MD simulations for general proteins. |

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Energetic Trade-off in Conformational Crystallization

Diagram Title: Energy Trade-off Drives Conformer Selection

Diagram 2: Integrated Strategy for Flexible Systems

Diagram Title: Multi-Technique Workflow for Structure Solution

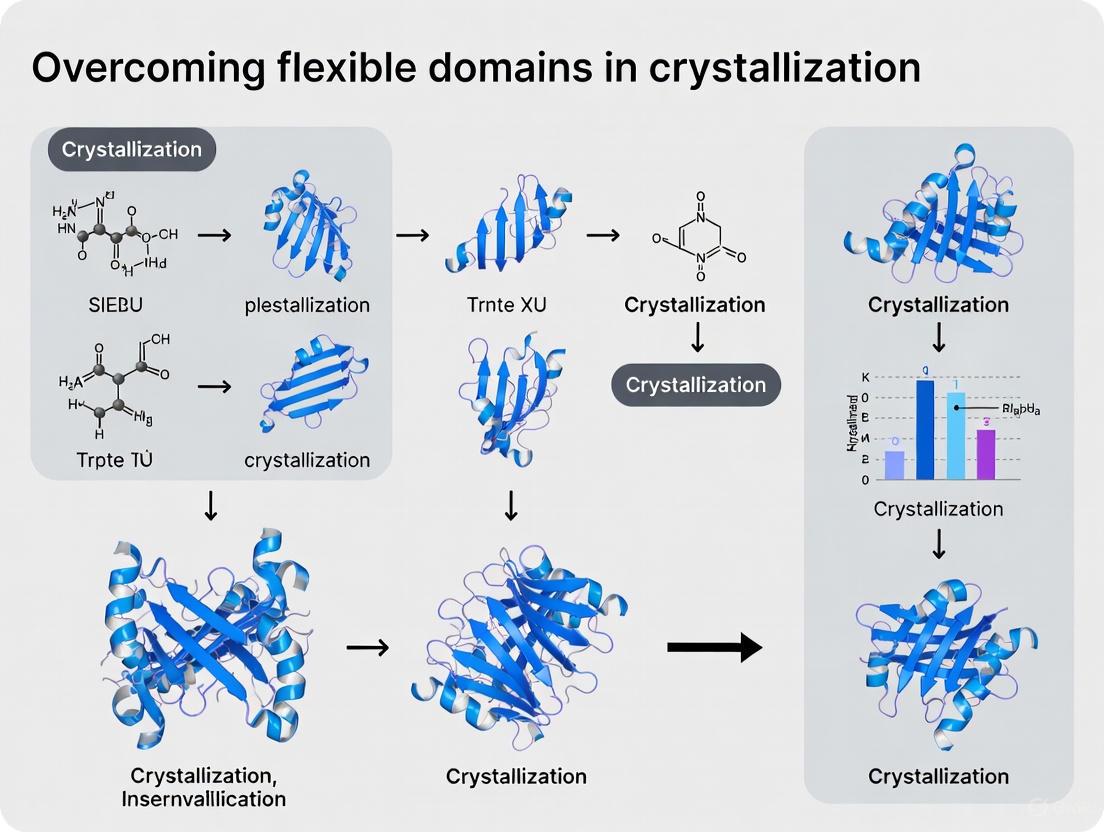

Within the bacterial cellulose synthase (Bcs) complex, the BcsC subunit is essential for exporting cellulose to the extracellular matrix [14] [15]. A key component of BcsC is its large periplasmic tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain, which is believed to play a critical role in the polysaccharide export process [14] [16]. However, structural studies of this domain have been hampered by its inherent flexibility—a common obstacle in crystallization research. This case study delves into the experimental strategies used to overcome the challenge of flexible domains, using the BcsC-TPR domain as a primary example. We will provide a detailed troubleshooting guide and FAQs to assist researchers in navigating similar structural biology problems.

Understanding the System: BcsC in Cellulose Biosynthesis

The Role of the Bcs Complex

Bacterial cellulose is a major component of biofilms, contributing to reduced susceptibility to antimicrobial treatments [15]. The Bcs secretion system in E. coli is a multi-subunit complex that spans the bacterial cell envelope. The core catalytic subunits are BcsA and BcsB, which synthesize and guide the cellulose polymer, respectively [15] [17] [18]. The BcsA-BcsB complex is sufficient for cellulose synthesis and translocation across the inner membrane [17]. The system is allosterically regulated by the bacterial second messenger cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP), which binds to a PilZ domain on BcsA, releasing an auto-inhibited state [17] [18].

BcsC's TPR Domain and Its Proposed Function

BcsC is an outer membrane protein thought to function as the exporting pore for cellulose [14] [15]. It is predicted to consist of two main domains:

- A large N-terminal periplasmic region containing TPR motifs (BcsC-TPR)

- A C-terminal β-barrel outer membrane domain [14]

Proteins with TPR-like domains, such as AlgK and PgaA, are found in other bacterial polysaccharide export systems, suggesting a conserved functional role [14] [16]. The structure of the BcsC-TPR domain from Enterobacter CJF-002 revealed an unexpected feature: an extra non-TPR α-helix inserted between two clusters of TPR motifs [14]. This inserted helix acts as a molecular hinge, conferring significant flexibility to the chain and changing the direction of the TPR super-helix. This flexibility is hypothesized to be important for the export of glucan chains [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Flexible Domains in Crystallography

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein is being degraded during purification. How can I identify a stable fragment for crystallization? A: Employ limited proteolysis combined with mass spectrometry. Treat your purified protein with a protease like trypsin for a limited time, then isolate the stable fragments and determine their molecular weights and N-terminal sequences. This approach successfully identified a stable 27,430 Da fragment (Asp24–Arg272) of the BcsC-TPR domain, which was subsequently crystallized [14].

Q2: My protein sample is heterogeneous. What methods can assess homogeneity for crystallization? A: Several biophysical methods are essential for assessing sample quality:

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Evaluates elution profile monodispersity.

- SEC coupled with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS): Provides absolute molecular weight and assesses oligomeric state.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measures the polydispersity of the sample; an ideal sample is monodisperse and not prone to aggregation [19].

Q3: I have a hit condition, but my crystals are small or poorly diffracting. What optimization strategies can I use? A: Systematic optimization is key. Consider these strategies:

- Fine Screening: Create a grid or random matrix around your hit condition, slightly varying the concentration of precipitant, salt, and buffer.

- Additive Screening: Add small molecules (e.g., salts, ligands, or other chemicals) to your base condition to subtly alter crystal packing.

- Seeding: Transfer small crystal fragments (seeds) from previous experiments into new crystallization drops to promote growth over spontaneous nucleation.

- Drop Modulation: Vary the drop size, protein-to-precipitant ratio, or temperature to change the kinetics of crystal growth [20].

Q4: How does inherent protein flexibility hinder crystallization, and what can be done? A: Flexible regions, such as the hinge in BcsC-TPR, induce conformational heterogeneity, which prevents the formation of a well-ordered crystal lattice [14] [19]. Solutions include:

- Construct Redesign: Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., AlphaFold3) to identify and truncate flexible regions [19].

- Limited Proteolysis: As in Q1, to isolate stable, rigid domains [14].

- Use of Chaperones: Affinity tags can sometimes improve solubility and act as crystallization chaperones [19].

Experimental Protocols for Challenging Targets

Protocol 1: Identifying Stable Domains via Limited Proteolysis

- Purify the target protein to high homogeneity (>95%).

- Incubate the protein with a low concentration of protease (e.g., trypsin) at a defined temperature.

- Quench the reaction at various time points by adding a protease inhibitor or by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer.

- Analyze the digestion pattern by SDS-PAGE.

- Isolate stable fragments from a non-denaturing gel for N-terminal sequencing and Molecular Weight determination via MALDI-TOF-MS [14].

Protocol 2: Assessing Solution Structure using SEC-SAXS For flexible proteins, understanding the solution conformation is critical.

- Purify the protein fragment as in Protocol 1.

- Inject the sample onto a size-exclusion column coupled directly to a Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) instrument.

- Collect X-ray scattering data throughout the elution peak.

- Analyze the data to generate an low-resolution ab initio envelope model of the protein's shape in solution. This technique confirmed the elongated, flexible nature of the BcsC-TPR domain [14].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Key Structural Findings from the BcsC-TPR(N6) Study

The crystal structure of the N-terminal part of BcsC-TPR (BcsC-TPR(N6), Asp24–Arg272) provided crucial insights into its flexible nature. The table below summarizes the quantitative findings from the structural analysis.

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of BcsC-TPR(N6) from Crystallographic Analysis

| Feature | Observation | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Fold | 14 α-helices forming 6 TPR motifs and 2 non-TPR helices [14] | Unlike most TPR proteins which have continuous motifs [21] |

| Inserted α-helix | α5 (Ala97–Leu108) is a non-TPR helix between TPR2 and TPR3 [14] | Acts as a flexible hinge, disrupting the continuous super-helix |

| Conformational Variability | 5 independent molecules in crystal had 3 distinct conformations (Type 1: A,C; Type 2: B,D; Type 3: E) [14] | Direct evidence of structural flexibility at the hinge region |

| Angular Deviation | C-terminal halves (α6–α11) showed directional differences of 18.9°–78.4° when N-terminal halves were superimposed [14] | Quantifies the range of motion conferred by the hinge |

| SEC-SAXS Analysis | Elongated envelope model for full BcsC-TPR (Asp24–Leu664) in solution [14] | Confirms flexibility is retained in the near-full-length domain |

Essential Reagents and Materials

A successful structural study of a flexible protein requires a toolkit of specialized reagents and equipment. The following table lists key solutions used in the featured BcsC-TPR study and related crystallization experiments.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Crystallization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel-NTA Resin | Affinity purification of His-tagged recombinant proteins | Used for initial purification of BcsC-TPR fragments [14] |

| Size Exclusion Media | Polishing step for sample homogeneity and oligomerization state analysis | Used after affinity chromatography for final purification [14] [15] |

| Crystallization Screen Kits | Empirically test a wide range of conditions to find initial "hits" | Commercial screens often include ammonium sulfate and PEGs [19] |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Precipitant that induces crystallization via "salting-out" [19] | A very common salt in crystallization screens |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer that induces macromolecular crowding and reduces solubility [19] | Molecular weight can significantly impact results |

| Trypsin | Protease for limited proteolysis to identify stable domains [14] | Concentration and incubation time must be optimized |

| TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) | Reductant to prevent cysteine oxidation; long half-life across wide pH range [19] | Preferred over DTT for long crystallization experiments |

Visualizing Experimental Strategies and Structural Flexibility

Workflow for Crystallizing Flexible Domains

The following diagram outlines the logical workflow for tackling crystallization of flexible proteins, integrating key strategies from the BcsC-TPR case study.

Diagram 1: Crystallization workflow for flexible domains.

Mechanism of Hinge-Mediated Flexibility in BcsC-TPR

This diagram illustrates the structural basis for flexibility in the BcsC-TPR domain, as revealed by the crystal structure.

Diagram 2: Mechanism of hinge flexibility in BcsC-TPR.

In modern drug development, molecular flexibility is not an exception but a rule. Nearly all modern drug molecules exhibit significant conformational flexibility, which is a fundamental feature influencing their behavior and properties [9]. This flexibility, defined as the ability of a molecule to adopt multiple three-dimensional shapes via bond rotations, directly impacts critical pharmaceutical characteristics including bioavailability, metabolic stability, and solid-form performance [9].

The prevalence of flexible molecules in pharmaceuticals stems from advanced drug discovery approaches that often produce complex molecules with multiple rotatable bonds. While this flexibility is essential for biological activity—enabling specific conformations that interact with protein receptors—it introduces substantial challenges for pharmaceutical scientists, particularly in controlling and reproducing the crystallization process that is crucial for drug product manufacturing [9]. Understanding these challenges is the first step toward developing effective strategies to overcome them.

FAQ: Understanding Flexibility Challenges in Pharmaceutical Development

Q1: Why does molecular flexibility complicate pharmaceutical crystallization?

Molecular flexibility exponentially increases the complexity of crystallization by expanding the conformational space that must be sampled during crystal formation. Each rotatable bond introduces an independent variable, leading to what crystallographers call "the curse of dimensionality" [9]. Flexible molecules must pay an intramolecular energy penalty to adopt the specific conformations required for optimal crystal packing. This creates a delicate balance between intramolecular strain and intermolecular stabilization that determines whether a molecule will crystallize and what crystal form it will adopt [9].

Q2: How does molecular flexibility relate to polymorphic control?

Different conformations of the same flexible molecule can pack into distinct crystal structures, giving rise to conformational polymorphism [9]. Each polymorph may exhibit different physical properties, including melting point, solubility, dissolution rate, and mechanical strength [22]. These differences directly impact drug product performance, making polymorphic control essential for ensuring consistent drug quality, stability, and efficacy [22] [23].

Q3: What is the connection between flexibility and crystallizability?

Large, flexible molecules often present significant crystallization challenges, sometimes failing to crystallize altogether or requiring extensive experimental efforts to form suitable crystals [9]. This occurs because flexible molecules in solution can adopt a wide range of conformations that may differ from those required for efficient crystal packing. The adoption of the "correct" conformer for crystallization is a critical step, and "incorrect" solution conformations can even lead to self-poisoning during crystal growth, where non-crystallographic conformers inhibit further crystal development [9].

Q4: What are the key energetic considerations for flexible molecules in crystals?

Recent research has revealed a striking empirical trend called the "40% limit" for flexible molecules in the solid state [9]. This principle states that up to 40% of the intermolecular stabilization energy in a crystal can compensate for intramolecular energy penalties associated with conformational changes. Beyond this threshold, the probability of observing a higher-energy conformation in the solid state becomes negligible. Understanding this balance is crucial for predicting crystal structures and anticipating crystallization difficulties [9].

Table: Key Energetic Terms in Crystalline Flexible Molecules

| Energy Term | Symbol | Definition | Significance in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice Energy | Elatt-global | Total energy of the crystal structure | Determines overall crystal stability |

| Intermolecular Energy | Einter | Energy from molecule-molecule interactions within crystal lattice | Provides driving force for crystallization |

| Intramolecular Energy | Eintra-global | Energetic penalty for conformational distortion | Represents cost of adopting crystal conformation |

| Adjustment Energy | Eadjustment | Energy required to distort gas-phase conformer to crystal conformation | Measures molecular strain in crystal environment |

| Global Change Energy | ΔEchange-global | Energy difference between crystal-forming conformer and most stable gas-phase conformer | Indicates conformational shift required for packing |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Characterizing Flexible Systems

Computational Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) for Flexible Molecules

Purpose: To predict possible crystal structures of flexible pharmaceutical compounds and assess their relative stabilities.

Procedure:

- Conformational Search: Perform comprehensive sampling of the molecule's conformational landscape using tools like the CSD Conformer Generator [9].

- Crystal Structure Generation: Generate thousands of hypothetical crystal structures for each low-energy conformer using space group symmetry and packing considerations.

- Energy Ranking: Calculate accurate lattice energies for all generated structures using validated computational models.

- Stability Analysis: Compare relative stabilities of predicted structures and identify potentially relevant polymorphs.

Key Considerations: For flexible molecules, CSP requires substantial computational resources. Recent blind tests reported consumption of 600,000 to nearly 4 million CPU hours for single flexible molecules [9]. The accuracy of CSP depends critically on the computational method used to balance intra- and intermolecular interactions.

Table: Benchmark Performance of Computational Methods for Polymorph Energy Ranking

| Computational Method | Intermolecular Treatment | Intramolecular Treatment | Mean Absolute Deviation (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBE-MBD/B2PLYPD | PBE-MBD | B2PLYPD | 2.3 |

| PBE-MBD/ωB97XD | PBE-MBD | ωB97XD | 2.4 |

| PBE-TS/B2PLYPD | PBE-TS | B2PLYPD | 3.1 |

| PBE-TS/ωB97XD | PBE-TS | ωB97XD | 3.2 |

Technical Note: The PBE-MBD/B2PLYPD method identified as the Best Lattice Energy Model (BLEM) in recent benchmarking reproduces experimental polymorph stabilities with a mean absolute deviation of just 2.3 kJ·mol⁻¹ across 17 polymorphic pairs [9].

Controlling Polymorphism Through Seeded Crystallization

Purpose: To reliably produce the desired polymorphic form of a flexible pharmaceutical compound.

Procedure:

- Seed Preparation: Prepare small, pre-formed crystals of the desired polymorph through careful screening of crystallization conditions [22] [23].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a saturated solution of the compound in an appropriate solvent system at controlled temperature.

- Supersaturation Generation: Carefully adjust conditions (cooling, anti-solvent addition, or evaporation) to create a metastable supersaturated solution.

- Seeding: Introduce pre-formed seeds into the supersaturated solution at the appropriate temperature and supersaturation level.

- Controlled Growth: Maintain crystallization conditions to promote growth on seeds while suppressing spontaneous nucleation of other forms.

Key Considerations: Seeding is particularly effective when controlling polymorphic forms is critical or when the compound is prone to forming amorphous solids [22]. The timing, temperature, and quantity of seeds significantly impact success. Seeding can also help manage oiling out (liquid-liquid phase separation) common with flexible molecules [23].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Flexibility Research

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Crystallization of Flexible Molecules

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Considerations for Flexible Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolution and crystallization medium | All crystallization experiments | Polarity and hydrogen-bonding capacity influence conformational selection |

| Anti-solvents | Reduce API solubility to induce crystallization | Anti-solvent crystallization | Addition rate controls nucleation; compatibility prevents degradation [22] |

| Polymer Additives | Modify crystal habit and suppress unwanted forms | Polymorph control | Can preferentially interact with specific conformers or crystal faces |

| Seeds of Desired Polymorph | Template for controlled crystal growth | Seeded crystallization | Critical for flexible molecules with multiple stable polymorphs [22] [23] |

| Surface-Active Agents | Control crystal agglomeration and interfacial energy | Prevention of oiling out | Can stabilize intermediate conformations during crystallization |

| Computational Tools | Predict conformational landscape and crystal packing | Crystal structure prediction | Essential for understanding energy balances in flexible systems [9] |

Advanced Strategies: Sequential Crystallization and Kinetic Control

For particularly challenging flexible molecules, traditional crystallization approaches may be insufficient. Sequential crystallization strategies that decouple the crystallization process into distinct stages offer enhanced control for complex systems [24]. This approach involves temporally separating nucleation and growth phases or controlling the crystallization of different components in a mixture.

The fundamental principle involves creating a metastable network during initial crystallization stages, followed by controlled maturation or secondary crystallization within this pre-formed framework [24]. This strategy helps maintain optimal domain size while enhancing crystallinity, directly addressing the crystallinity-domain size paradox common with flexible molecules [24].

Implementation Example: Dual-additive approaches using compounds with contrasting binding affinities (e.g., o-DCB with low binding energy and FN with high binding energy to the API) can create temporally resolved crystallization. One additive mediates initial co-crystallization into a metastable network during film formation, while the second drives confined crystallization within this framework upon subsequent processing [24].

This advanced approach has demonstrated broad applicability across multiple pharmaceutical systems, achieving optimized morphologies with enhanced crystallinity while maintaining appropriate domain sizes—critical for balancing stability and dissolution requirements in final drug products [24].

The challenges posed by molecular flexibility in pharmaceuticals are significant but not insurmountable. By understanding the fundamental energetics—particularly the 40% compensation limit between intramolecular strain and intermolecular stabilization—and implementing robust experimental protocols including computational prediction, seeded crystallization, and advanced kinetic control strategies, researchers can successfully navigate these complexities [9].

The future of managing flexibility in pharmaceutical development lies in integrated approaches that combine computational prediction with experimental validation, enabling rational design of crystallization processes rather than empirical optimization. As these methodologies continue to advance, they will transform molecular flexibility from a formidable challenge into a manageable design parameter in drug development.

Practical Approaches for Taming Flexibility: Construct Design, Screening, and Computational Prediction

FAQs: Systematic Truncation for Protein Crystallization

1. What is the primary goal of systematic truncation in construct engineering? The primary goal is to identify a protein's stable core domain by methodically removing flexible amino acids from the N and C termini. This process aims to improve the protein's solubility, stability, and propensity to crystallize, which is often hindered by dynamic or disordered regions [25].

2. Why do flexible domains prevent successful crystallization? Flexible domains often lack a single, stable conformation. For a crystal to form, millions of protein molecules must pack into a highly ordered, repeating lattice. Flexibility prevents this consistent packing, leading to poor-quality crystals or no crystals at all [25].

3. How do I determine where to truncate my protein? A multi-pronged approach is most effective:

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Use sequence alignment with homologs of known structure to identify conserved core regions.

- Existing Structural Data: If available, examine structures of your protein or close relatives to locate disordered termini or flexible loops.

- Experimental Screening: Design and test a library of constructs with varying N and C termini. The optimal truncation points are identified empirically by screening for expression, solubility, and stability [25].

4. What biophysical techniques can identify stable constructs?

- High-Throughput Melting Point Analysis: Measures a protein's thermal stability. Constructs with a higher melting point ((T_m)) are typically more stable and better candidates for crystallization [25].

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Assesses the monodispersity and oligomeric state of a protein sample. A sharp, symmetrical SEC peak suggests a homogeneous, well-behaved sample [25].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Determines the size distribution and polydispersity of particles in solution. Low polydispersity indicates a uniform protein population suitable for crystallization trials [25].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions in Truncation Construct Engineering

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Solubility or Expression | Hydrophobic or charged residues on the new terminus; core domain destabilized by truncation [25]. | Screen a broader range of truncation variants; fuse with a solubility tag (e.g., GST, MBP); test different expression conditions (temperature, inducer concentration). | Design constructs that end with stable secondary structure elements (e.g., alpha-helices, beta-sheets); use bioinformatics tools to predict disordered regions. |

| Poor Crystallization Results | Retained flexible residues; insufficient stability; low sample homogeneity [25]. | Further truncate termini based on initial results; use surface entropy reduction mutagenesis; improve purification to >95% purity and ensure monodispersity. | Employ biophysical characterization (e.g., melting point analysis) to select the most stable constructs before crystallization trials [25]. |

| Inadequate Stability | Truncation has compromised the protein's hydrophobic core or key stabilizing interactions. | Revert to a slightly longer construct; screen for stabilizing ligands or co-factors; use thermal shift assays to identify stabilizing conditions. | Create incremental truncation libraries to finely map the minimal stable domain without over-truncating [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Systematic Truncation

This protocol outlines a multi-step process for identifying a stable protein core domain, based on high-throughput methodologies [25].

1. Construct Design and Library Generation

- Design: Based on sequence analysis and homology modeling, design a set of 10-20 constructs with varying N and C termini. Include both large incremental changes and fine-scale truncations, especially near suspected domain boundaries.

- Cloning: Clone all constructs into an appropriate expression vector, preferably with a cleavable affinity tag (e.g., GST, His-tag) to facilitate purification.

2. Small-Scale Expression and Solubility Screening

- Expression: Test express each construct in small culture volumes (e.g., 1-5 mL).

- Lysis and Clarification: Lyse cells and separate soluble and insoluble fractions via centrifugation.

- Analysis: Analyze fractions by SDS-PAGE to identify constructs that express well and are soluble.

3. Parallelized Automated Purification

- Affinity Purification: Purify soluble constructs using an automated system (e.g., ÄKTAxpress) with affinity chromatography.

- Tag Cleavage: Cleave the affinity tag with a specific protease (e.g., thrombin).

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Perform SEC as a polishing step and to assess sample homogeneity. Constructs yielding a single, sharp peak are prioritized.

4. Biophysical Characterization

- Melting Point Analysis: Use a high-throughput method (e.g., differential scanning fluorimetry) to determine the thermal stability ((Tm)) of each construct. Constructs with the highest (Tm) are the most stable [25].

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Confirm the monodispersity of the top candidates.

5. Crystallization Trials

- Scale-Up: Conduct large-scale purification of the most promising constructs (high solubility, high (T_m), monodisperse).

- Screening: Set up high-throughput crystallization trials. Constructs identified through this pipeline have a significantly higher probability of yielding diffracting crystals [25].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Systematic Truncation Workflow

Analytical Selection Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Systematic Truncation |

|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for cloning constructs, often featuring cleavable tags (GST, His) to facilitate expression and purification [25]. |

| E. coli Expression Strains | Engineered bacterial cells optimized for high-yield protein expression, used in initial small-scale screening [25]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Media (e.g., Glutathione Sepharose for GST, Ni-NTA for His-tag) for the initial capture and purification of tagged protein constructs [25]. |

| Proteases for Tag Cleavage | Enzymes like thrombin or TEV protease that specifically cleave the affinity tag from the protein of interest after purification [25]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Used to separate proteins based on size, serving as a polishing step and a critical analytical tool for assessing sample homogeneity [25]. |

| Automated Liquid Handling & FPLC | Systems (e.g., ÄKTAxpress) that enable parallel, reproducible purification of multiple constructs, increasing throughput and efficiency [25]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes for DSF | Dyes (e.g., SYPRO Orange) used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry to measure protein thermal stability ((T_m)) and identify the most stable constructs [25]. |

Within structural biology, a significant barrier to obtaining high-resolution crystal structures is the presence of intrinsically flexible domains and surface features on proteins. These high-entropy regions, often called an "entropic shield," impede the formation of orderly crystal lattices by resisting the immobilization required for crystal contacts [27]. Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) is a rational mutagenesis strategy designed to overcome this exact problem. The method systematically replaces clusters of surface-exposed, high-flexibility residues (typically Lys, Glu, Arg, and Gln) with smaller, less flexible amino acids like alanine, threonine, or serine [28] [29]. By reducing the local surface entropy, these mutations lower the thermodynamic penalty of incorporating the protein molecule into a crystal lattice, thereby promoting the formation of crystal contacts and facilitating the growth of diffraction-quality crystals [27] [30]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and foundational protocols for implementing SER within your crystallization research, particularly when confronting challenging proteins with dynamic surfaces.

SER Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My SER mutant expressed well but still won't crystallize. What should I check?

- A: If your initial SER construct fails to crystallize, consider these corrective actions:

- Employ Alternate Screening Conditions: Re-screen your mutant using a broad matrix of conditions. Impressively, more than half of SER mutants that failed in standard screens yielded crystals when re-screened using 1.5 M NaCl as the primary precipitant [28]. This can greatly increase the variety of conditions that yield crystals.

- Verify Protein Quality: Re-assess your purified protein. Ensure your final purification step is gel filtration to guarantee monodispersity and check for aggregation using dynamic light scattering (DLS) [31] [32]. Inconsistent protein quality is a common culprit.

- Increase Protein Concentration: Try crystallizing at a significantly higher protein concentration. For some problematic systems, increasing the concentration from 8 mg/mL to 30 mg/mL can be necessary [31].

- Utilize Seeding: Introduce microseeds from related crystalline samples or pre-formed microcrystals of your protein into new drops. Seeding is a highly effective method for promoting crystal growth in stubborn systems [31].

FAQ 2: How can I apply SER to a protein for which I have no structural model?

- A: The absence of a 3D structure does not preclude using SER. You can use the SERp (Surface Entropy Reduction prediction) online server [27] [33]. This tool requires only your protein's amino acid sequence. It performs three primary analyses to suggest mutation clusters:

- Secondary Structure Prediction: Identifies coil regions, which are favorable mutation sites as they tend to be surface-exposed and effective for SER.

- Entropy Profiling: Computes a side-chain entropy profile across your sequence to find clusters of high-entropy residues.

- Sequence Conservation Analysis: Identifies conserved residues (disfavored for mutation) and residues that are naturally mutated to alanine or serine in homologs (favored for mutation) [27]. The server outputs a ranked list of residue clusters recommended for simultaneous mutation.

FAQ 3: My SER mutant precipitated or lost solubility. How can I prevent this?

- A: Replacing charged surface residues with neutral ones can reduce solubility. To mitigate this:

- Limit Mutation Number: A key SER principle is to introduce a minimal number of mutations (typically 2-3 residues within a single cluster) to sufficiently reduce entropy without critically compromising solubility [27] [34].

- Consider Alternative Residues: While alanine is the most common replacement, threonine, serine, and tyrosine are excellent alternatives. These residues still have low conformational entropy but can participate in favorable hydrogen-bonding interactions that may mediate crystal contacts and help maintain solubility [28] [29].

- Use Solubility-Enhancing Additives: Include additives like arginine or detergents in your crystallization and protein storage buffers to help stabilize the protein and prevent aggregation [31].

FAQ 4: The crystals I obtained from an SER mutant diffract poorly. What optimization strategies can I try?

- A: Obtaining crystals is a major step, but improving diffraction quality is often the next challenge.

- Post-Crystallization Treatments: Controlled dehydration of crystals can sometimes contract the crystal lattice, improving order and resolution [32].

- Optimize Cryoprotection: Experiment with different cryoprotectant solutions and protocols. A gradual increase in cryoprotectant concentration or the use of sugars (e.g., sucrose) as cryoprotectants can better preserve crystal order [31].

- Check for Crystal Form Variation: Sometimes, a single condition can produce multiple crystal forms. Carefully mount dozens of crystals and compare their diffraction to find the best form [31].

Core Experimental Protocols

SER Mutagenesis Design Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key decision points for designing an SER mutagenesis experiment.

Key Reagents and Materials for SER

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for SER Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SERp Web Server [27] | Computational prediction of optimal surface entropy reduction clusters based on primary sequence. | Input: Amino acid sequence. Output: Ranked list of mutation clusters. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduction of point mutations into the protein expression plasmid. | e.g., QuikChange II kit [35] [30]. |

| Crystallization Sparse-Matrix Screens | Initial screening of crystallization conditions for wild-type and mutant proteins. | e.g., The Classics, PEGs Suites [35]. |

| High-Salt Screening Conditions | Alternative screening strategy specifically effective for many SER mutants [28]. | Use 1.5 M NaCl as a primary component in reservoir solutions. |

| Seeding Tools | To initiate crystal growth in metastable conditions, particularly after SER. | Microseed stock solutions [31]. |

| Maltose Binding Protein (MBP) | A solubility-enhancing fusion partner used in synergistic SER-carrier protein strategies [34]. | N-terminal fusion to target protein can improve expression and solubility. |

Protocol: Implementing SER for a Challenging Target

This protocol outlines the steps from design to crystallization screening for an SER mutant, using the successful crystallization of Human Aurora kinase C (Aurora-C) as a case study [29].

Step 1: Construct and Mutagenesis Design

- Begin with the most promising "first-generation" truncation construct of your target protein that expresses solubly but does not crystallize [29].

- Identify a surface-exposed patch of high-entropy residues. For Aurora-C, the cluster R195-R196-K197 was identified.

- Design a mutant in which all residues in the cluster are replaced with alanines (e.g., R195A/R196A/K197A) [29]. All mutations within a predicted cluster should be introduced concurrently [27].

Step 2: Generating the SER Mutant

- Perform site-directed mutagenesis on your expression plasmid to introduce the desired mutations. Verify the final plasmid sequence by DNA sequencing [35] [30].

- Express and purify the SER mutant protein using the same protocol optimized for the wild-type protein. The goal is to produce a homogeneous, monodisperse sample at a high concentration (>10 mg/mL) [29].

Step 3: Crystallization Trials and Optimization

- Set up initial crystallization trials with the purified SER mutant using a standard sparse-matrix screen in parallel with the wild-type protein as a control.

- Crucially, also screen using a condition where the standard reservoir is replaced with 1.5 M NaCl, as this has proven highly effective for many SER mutants [28].

- If initial hits are obtained (even poor microcrystals), proceed to optimization. For Aurora-C, the initial condition of 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 5.5, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 25% PEG 3350 was optimized to 0.1 M bis-Tris pH 5.5, 0.025–0.050 M ammonium sulfate, 9–12% PEG 3350, yielding high-quality crystals [29].

Data Presentation: SER Strategies and Outcomes

Comparing SER Mutation Strategies

Table 2: Summary of SER Mutagenesis Approaches

| Strategy | Mechanism | Typical Substitutions | Key Advantages | Reported Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Alanine SER [28] [27] | Maximizes entropy reduction by replacing flexible side chains with a small, rigid methyl group. | K/E → A | Strongest reduction in conformational entropy; often the most effective. | Established robust crystallization for numerous targets; enabled structure of Aurora-C [29]. |

| Polar Residue SER [28] [29] | Reduces entropy while introducing potential for hydrogen bonding in crystal contacts. | K/E → S, T, Y | Can mediate specific contacts via H-bonding; may better maintain surface solubility. | Tyrosine and threonine mutants showed considerable potential to mediate crystal contacts [28]. |

| Permissive SER [35] | Promotes crystallization primarily by removing steric/electrostatic barriers rather than adding new interactions. | K → S (in Ubiquitin study) | Removes impediments to packing, allowing native surfaces to form contacts. | In ubiquitin, some lysine-to-serine mutations enabled crystallization primarily by lysine removal [35]. |

Case Study: Quantitative SER Outcomes

Table 3: Experimental Results from SER Case Studies

| Protein Target | SER Mutation(s) | Experimental Outcome | Impact on Structure Determination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human O-GlcNAcase (HsOGA) [33] | E602A, E605A | New crystal form obtained. | Enabled modelling of previously disordered regions (88% of structure vs. 83% in WT). |

| Ubiquitin [35] | K11S, K33S, K63S | Crystallization "hit rates" varied by two orders of magnitude across 7 lysine mutants. | High-resolution structures revealed mutant serine residues directly participating in favorable packing interactions. |

| Aurora-C Kinase [29] | R195A, R196A, K197A | Successful crystallization where wild-type and activation-mimic mutants failed. | Enabled structure determination of the Aurora-C–INCENP complex at 2.8 Å resolution. |

FAQs: Addressing Core Experimental Challenges

Q1: Why would I use a T4 Lysozyme (T4L) fusion strategy instead of other crystallization chaperones?

T4L fusion is particularly effective for G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) and other membrane proteins because it replaces flexible, unstructured regions (like the third intracellular loop - ICL3 - or the N-terminus) with a stable, well-folded soluble domain. This serves two main purposes: it stabilizes the overall conformation of the target protein and provides a large, polar surface area to mediate crucial crystal packing contacts that the native protein lacks [36] [37]. While other tools like Fragment antigen-binding domains (Fabs) are also powerful chaperones, T4L is often favored for its proven track record and the ability to be engineered directly into the construct.

Q2: My GPCR-T4L fusion protein is expressed and pure, but I still cannot get diffracting crystals. What are my next steps?

This is a common hurdle. Your next steps should involve engineering the T4L fusion partner itself. As demonstrated in research on the M3 muscarinic receptor, wild-type T4L may not be optimal for all targets due to its inherent flexibility. You can consider:

- Disulfide-stabilized T4L (dsT4L): Introduce disulfide bonds (e.g., via I3C, T21C, A97C, and T142C mutations) to lock the N- and C-terminal lobes of T4L, reducing flexibility and potentially leading to alternate crystal lattices [36].

- Minimal T4L (mT4L): Delete the flexible N-terminal lobe of T4L and connect the remaining helices with a short linker (e.g., -GGSGG-). This reduces the size of the fusion partner and can promote new packing interactions, potentially yielding higher-resolution structures [36].

Q3: What should I do if my crystals form too quickly, resulting in poor diffraction quality?

Rapid crystallization often incorporates impurities and leads to poorly ordered crystals. To slow crystal growth [3]:

- Increase Solvent Volume: Redissolve your sample by adding a small amount of extra solvent (e.g., 1-2 mL for 100 mg of solid) beyond the minimum required for dissolution. This creates a more dilute environment that slows nucleation and growth.

- Improve Insulation: Ensure your crystallization setup is properly insulated. Use a watch glass over the flask and place it on an insulating surface like a cork ring or paper towels to slow the cooling rate.

Q4: How can I initiate crystallization if no crystals appear after cooling?

If your solution remains clear with no nucleation [3]:

- Mechanical Scratching: Use a glass rod to gently scratch the inside surface of the crystallization vessel to create microscopic grooves that can induce nucleation.

- Seeding: Introduce a minuscule "seed" crystal from a previous batch or a speck of crude solid.

- Solvent Reduction: Return the solution to the heat source and carefully boil off a portion of the solvent to increase concentration, then cool again.

Troubleshooting Guides: From Problem to Solution

Problem: Crystal Twinning or Low-Resolution Diffraction

This problem often arises from excessive flexibility in the fusion protein or suboptimal crystal packing.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Experimental Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal twinning | Excessive flexibility in the wild-type T4L domain. | Replace wild-type T4L with a disulfide-stabilized T4L (dsT4L) variant. | In the M3 muscarinic receptor, switching to dsT4L changed the crystal lattice from twinned (P1) to a non-twinned space group (P41212) [36]. |

| Low-resolution diffraction | The large, flexible T4L domain dominates packing and prevents optimal contacts. | Use a minimal T4L (mT4L) variant with the N-terminal lobe deleted. | For the M3 receptor, the mT4L fusion yielded a significantly higher 2.8 Å resolution structure compared to the original 3.4 Å structure [36]. |

| No crystals obtained | The flexible ICL3 or N-terminus is not fully stabilized, or the fusion linker is too long. | Optimize the fusion linkers and truncate flexible regions. For N-terminal fusions, a short, rigid linker (e.g., 2-Ala) is often effective. | For the β2AR, a two-alanine linker between T4L and the receptor, combined with truncation of ICL3 and the C-terminus, enabled crystallization [37]. |

Protocol: Engineering and Testing a Disulfide-Stabilized T4L (dsT4L) Fusion

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduce the mutations I3C, T21C, A97C, and T142C into your plasmid containing the wild-type T4L sequence. Note that the common "wild-type" T4L used in GPCR fusions already contains C54T and C97A mutations [36].

- Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify your target protein fused to the dsT4L variant using your standard protocol.