Synchrotron Radiation in Protein Crystallography: Accelerating Structural Biology and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of synchrotron facilities in protein crystallography, a cornerstone technique in modern structural biology.

Synchrotron Radiation in Protein Crystallography: Accelerating Structural Biology and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of synchrotron facilities in protein crystallography, a cornerstone technique in modern structural biology. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of synchrotron radiation, from its historical development to current third- and fourth-generation light sources. It delves into advanced methodological applications, including high-throughput crystallography and serial synchrotron crystallography (SSX), which are crucial for studying complex biological mechanisms and membrane proteins. The article also addresses common challenges in sample preparation and data collection, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies to maximize success. Finally, it provides a comparative analysis, validating the continued critical importance of synchrotron-derived structures against emerging techniques like cryo-EM and AI-predicted models, highlighting its indispensable role in structure-based drug design and the development of new therapeutics.

From Parasitic Mode to Powerhouse: The Foundation of Synchrotron Radiation in Biology

The evolution of synchrotron light sources from third-generation facilities to the fourth-generation era has fundamentally transformed structural biology research capabilities. This whitepaper examines how synchrotron facilities, particularly those employing multi-bend achromat (MBA) technology, have revolutionized protein crystallography by enabling studies of increasingly challenging biological systems. We document the technical specifications and performance metrics of modern beamlines, detail experimental methodologies for cutting-edge approaches like serial crystallography, and analyze the direct implications for drug discovery pipelines. The integration of these advanced capabilities with complementary structural techniques has established synchrotron facilities as indispensable tools for elucidating biological mechanisms and facilitating structure-based drug design.

The impact of structural biology over the past five decades has been tremendous, with protein structures providing fundamental insights into biological function, molecular interactions, and the mechanistic underpinnings of life itself [1]. Macromolecular structures have become essential tools for rational drug development and engineering of enzymes for green chemistry applications. The growth of this field is quantitatively demonstrated by the Protein Data Bank (PDB), which has expanded from its inaugural 7 structures to a repository containing over 220,000 structures as of August 2024 [1]. This exponential growth has been critically dependent on parallel advances in synchrotron radiation sources, which have evolved through multiple generations to dramatically enhance the capabilities of macromolecular crystallography (MX).

The transition to fourth-generation synchrotron facilities using multi-bend achromat (MBA) technology represents the most recent revolutionary leap, delivering significant reductions in electron beam emittance that result in increased X-ray brightness and coherence [1]. These technical advances produce more stable X-ray beams that enable faster data collection, reducing experimental time requirements and opening new possibilities for high-throughput crystallography applications. The enhanced beam characteristics have been particularly transformative for studying difficult-to-crystallize targets such as membrane proteins and large complexes, while simultaneously enabling time-resolved studies of enzymatic mechanisms.

The Evolution of Synchrotron Facilities and Beamline Capabilities

The development of synchrotron facilities has progressed through distinct generations characterized by fundamental improvements in source design and performance. Third-generation sources provided substantial gains in brightness through the implementation of insertion devices such as undulators and wigglers. However, the introduction of multi-bend achromat lattice structures in fourth-generation machines represents a qualitative leap in performance, enabling dramatic reductions in emittance that yield X-ray beams with unprecedented brightness and coherence [1].

The MAX IV Laboratory in Lund, Sweden, stands as the pioneer of fourth-generation storage ring technology, having been inaugurated in 2016 as the first facility to implement MBA technology in its storage ring design [1]. The 3 GeV ring at MAX IV, with a 528 m circumference operating at 400 mA current, has achieved a horizontal emittance of just 328 pm rad [1]. This exceptional performance establishes it as an ideal source for hard X-ray experiments including protein crystallography, providing the foundation for two dedicated protein crystallography beamlines: BioMAX and MicroMAX.

Complementary Beamline Design at MAX IV

The strategic design of BioMAX and MicroMAX exemplifies how modern synchrotron facilities optimize beamline capabilities to address diverse research needs while maintaining some operational overlap for flexibility [1].

BioMAX is conceived as a versatile, stable, high-throughput beamline catering to most protein crystallography experiments [1]. Its technical configuration includes an in-vacuum, room temperature permanent magnet undulator with an 18 mm magnetic period, 111 periods, and a minimum gap of 4.2 mm [1]. The beamline employs an Si(111) horizontal double-crystal monochromator followed by Kirkpatrick-Baez (KB) focusing mirrors, enabling stable operation between 6-24 keV with a relative bandwidth of 2×10⁻⁴ [1]. BioMAX offers four major focusing modes (100×100 μm², 50×50 μm², 20×20 μm², and 20×5 μm²), with the 50×50 μm² option being predominantly used as it aligns with average crystal sizes typically employed by users [1].

MicroMAX represents a more specialized facility dedicated to serial crystallography approaches including time-resolved experiments [1]. As the latest addition to MAX IV's structural biology portfolio, becoming operational in 2024, it is designed to exploit the special characteristics of fourth-generation beamlines provided by the 3 GeV ring [1]. The beamline shares common instruments, control software, computing facilities, and support staff with BioMAX, benefiting from integrated development while concentrating on advancing specific capabilities for serial crystallography.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of MAX IV Protein Crystallography Beamlines

| Parameter | BioMAX | MicroMAX |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | High-throughput macromolecular crystallography | Serial crystallography and time-resolved studies |

| X-ray Source | In-vacuum undulator (18 mm period) | Fourth-generation MBA source |

| Energy Range | 6-24 keV | Optimized for serial experiments |

| Focusing Modes | 100×100 μm², 50×50 μm², 20×20 μm², 20×5 μm² | Specialized for microcrystals |

| Special Capabilities | Continuous fast energy scanning (~1 s for absorption spectra) | Time-resolved measurements from ms to μs |

| Sample Environment | Automated sample changer (464 samples), room temperature capability | Optimized for serial sample delivery |

Additional Specialized Facilities

Beyond the dedicated protein crystallography beamlines, MAX IV hosts complementary facilities that expand the experimental possibilities for structural biologists. The FragMAX fragment-based drug discovery platform is hosted at BioMAX, supporting screening campaigns directly at the beamline [1]. Additionally, the FemtoMAX beamline at the short pulse facility located at the end of the linear accelerator enables protein diffraction experiments exploring ultrafast time resolution, bridging the gap between synchrotron and X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) capabilities [1].

Technical Advancements Enabling New Biological Insights

Serial Crystallography: Overcoming Traditional Limitations

Serial crystallography (SX) has emerged as a transformative methodology that liberates researchers from traditional constraints of macromolecular crystallography. This approach revolutionized structural biology by enabling high-resolution structure determination for important classes of proteins that were previously intractable, including studies of relevant biomolecular reaction mechanisms [2]. The technique addresses one of the most significant historical challenges in structural biology: the requirement for large, well-diffracting single crystals.

The fundamental principle of serial crystallography involves collecting diffraction data from thousands of microcrystals, with each crystal typically exposed to X-rays only once before replacement [2]. This "diffraction before destruction" approach was initially pioneered at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs), where ultra-bright femtosecond X-ray pulses outrun radiation damage processes [3]. The method was subsequently adapted for synchrotron sources as serial millisecond crystallography (SMX), leveraging the increased brightness of modern beamlines to enable data collection from crystal slurries [2].

The implementation of SX at synchrotron sources has been particularly enabled by the improved performance of fourth-generation facilities [1]. The higher brightness and stability of MBA-based beamlines allow for precise focusing to micrometer-sized beams, making it possible to employ serial crystallography approaches with micrometre-sized crystals [1]. This capability has opened new opportunities for studying membrane proteins and other challenging systems that typically produce only microcrystals in crystallization experiments.

Sample Consumption and Delivery Methodologies

A persistent challenge in serial crystallography has been the efficient utilization of precious macromolecular samples, whose availability is often limited [2]. Early SX experiments required gram quantities of purified protein, making studies of biologically and medically relevant targets prohibitive for many research groups [2]. Advances in sample delivery technologies have progressively reduced these requirements, with modern approaches consuming microgram amounts rather than milligrams [2].

Table 2: Sample Delivery Methods for Serial Crystallography

| Delivery Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Sample Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Injection | Continuous jet of crystal suspension | High data collection rates | Historically high (grams), now reduced to milligrams |

| Fixed-Target | Crystals loaded on reusable chips | Minimal sample waste between pulses | Microgram amounts achievable |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion | Crystal suspension in viscous matrix | Reduced flow rates, lower background | Significantly reduced consumption |

| Hybrid Methods | Combination of approaches | Customized for specific experiments | Variable, optimized for specific needs |

The theoretical minimum sample requirement for a complete SX dataset has been estimated based on specific experimental parameters. Assuming 10,000 indexed patterns are sufficient for a full dataset, with microcrystal dimensions of 4×4×4 μm and a protein concentration in the crystal of approximately 700 mg/mL, the ideal sample consumption would be approximately 450 ng of protein [2]. While practical implementations have not yet reached this theoretical minimum, current methodologies have dramatically reduced sample requirements compared to early SX experiments.

Time-Resolved Studies: Capturing Molecular Movies

The high brightness and rapid data collection capabilities of modern synchrotron beamlines have enabled time-resolved structural studies that capture enzymatic reactions and conformational changes in real time. Time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography (TR-SFX) experiments can be performed using photosensitive proteins with pump-probe lasers to study light-activated proteins with typical reaction timescales from microseconds to femtoseconds [2]. An alternative approach, mix-and-inject serial crystallography (MISC), involves mixing reactants and substrates with protein crystals to induce conformational changes immediately before X-ray exposure, enabling structural studies over second to sub-millisecond timescales [2].

These time-resolved approaches have led to the conceptualization of "molecular movies" that allow researchers to visualize various biomolecular reactions as they occur [2]. The ability to capture intermediate states in enzymatic cycles and signaling processes provides unprecedented insights into biological mechanism that static structures cannot reveal.

Experimental Protocols for Serial Crystallography

Sample Preparation and Characterization

Successful serial crystallography experiments require optimization of microcrystal growth conditions and thorough characterization of crystal quality and size distribution. The following protocol outlines key steps for sample preparation:

Microcrystal Optimization: Screen crystallization conditions using standard vapor diffusion or batch methods while varying precipitant concentration, temperature, and incubation time to identify conditions yielding abundant microcrystals (1-20 μm in size).

Size Homogenization: Pass crystal suspensions through appropriately sized mesh filters or perform density gradient centrifugation to ensure uniform crystal size distribution, which improves data quality and reduces sample consumption.

Crystal Stability Assessment: Monitor diffraction quality over time using a test dataset collected at a synchrotron microfocus beamline to ensure crystals maintain integrity during data collection.

Concentration Adjustment: Concentrate crystal suspensions to optimal density (typically 10⁸-10¹⁰ crystals/mL) using gentle centrifugation or filtration to balance hit rate against crystal wastage.

Fixed-Target Data Collection

Fixed-target approaches offer minimal sample consumption and are particularly suitable for precious samples where crystal supply is limited:

Chip Loading: Apply 0.5-2 μL of crystal suspension to fixed-target chips composed of low-X-ray-background materials such as silicon nitride or polymer-based substrates.

Excess Solution Removal: Briefly blot chips to remove excess mother liquor while maintaining crystal hydration, typically leaving a thin film of approximately 1-5 μm thickness.

Mounting and Alignment: Secure the chip in the beamline sample holder and align using on-axis video microscopy to ensure the crystal-containing region is positioned in the X-ray beam path.

Raster Scanning: Program a raster pattern with step size matching the beam diameter (typically 5-20 μm) to ensure most crystals are centered during exposure while minimizing repeated measurements of the same crystal.

Data Collection: Collect diffraction patterns at each raster position with exposure times typically ranging from 1-100 ms per location depending on beam intensity and crystal diffracting power.

Liquid Jet Injection for Time-Resolved Studies

Liquid injection methods enable truly continuous data collection and are preferred for time-resolved experiments:

Injector Setup: Assemble gas dynamic virtual nozzle (GDVN) or similar liquid injector system, ensuring all components are clean and properly aligned.

Sample Loading: Transfer crystal suspension into the injector reservoir, taking care to avoid introduction of air bubbles that would disrupt stable jet formation.

Jet Optimization: Adjust flow rate (typically 10-50 μL/min) and nozzle position to establish a stable liquid jet of consistent diameter (10-50 μm) at the X-ray interaction point.

Beline Synchronization: Synchronize X-ray pulse timing with jet position for maximum hit rate, typically achieved through optical imaging and feedback systems.

Data Collection: Continuously collect diffraction patterns at the maximum repetition rate supported by the detector system, typically achieving hit rates of 5-20% depending on crystal density and jet stability.

Visualization of Serial Crystallography Workflow

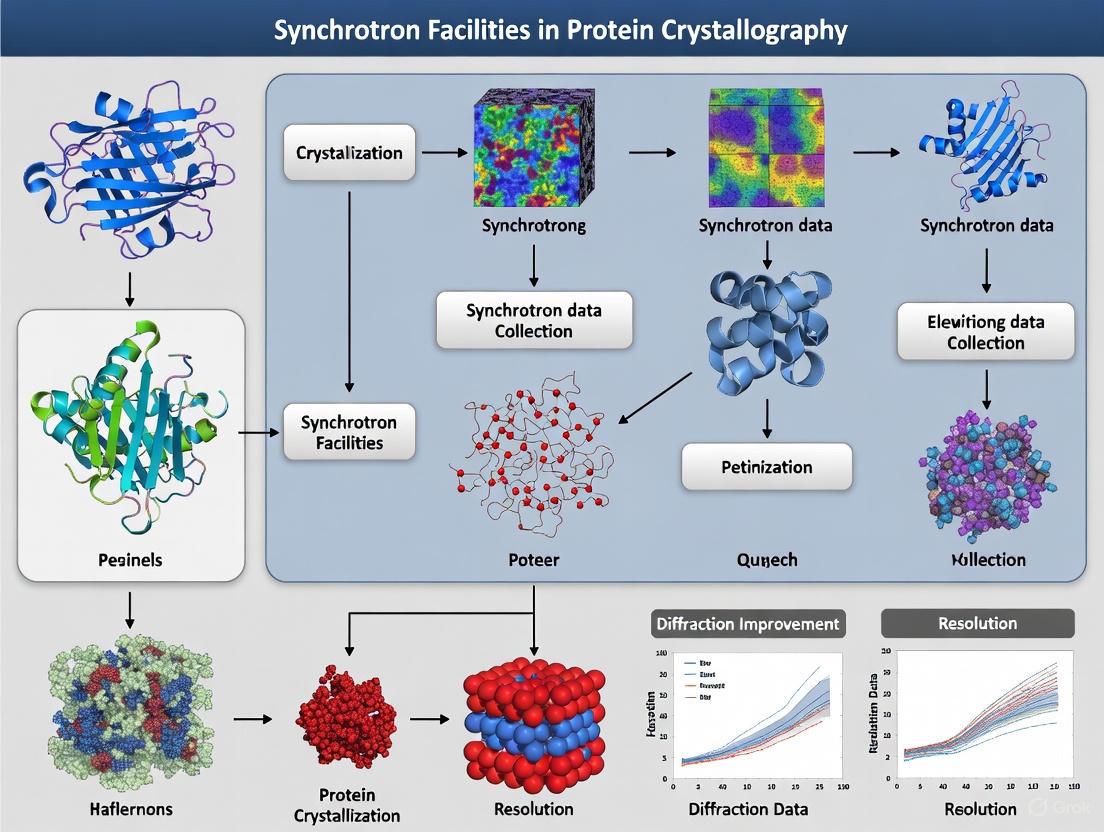

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for serial crystallography experiments at modern synchrotron facilities:

Diagram 1: Serial Crystallography Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the comprehensive process from sample preparation to final structure deposition, highlighting the iterative data collection and processing steps characteristic of serial methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Synchrotron-Based Crystallography

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Initial identification of crystallization conditions | Commercial sparse matrix screens (e.g., from Hampton Research) cover diverse chemical space |

| Microseeding Tools | Improve crystal size and quality homogeneity | Essential for generating microcrystals suitable for serial studies |

| Cryoprotectants | Prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling | Glycerol, ethylene glycol, or sucrose solutions at appropriate concentrations |

| Fixed-Target Chips | Sample support for minimal consumption approaches | Silicon nitride membranes or polymer-based chips with predefined apertures |

| Liquid Injectors | Continuous sample delivery for time-resolved studies | Gas dynamic virtual nozzles (GDVNs) provide stable micron-diameter jets |

| Sample Pucks/Cassettes | Standardized sample storage and handling | UNI pucks compatible with automated sample changers enable high-throughput |

| Crystal Harvesting Tools | Manipulation of microcrystals | Specialized loops and micromeshes for crystal mounting and cryo-cooling |

Impact on Drug Discovery and Future Perspectives

The advanced capabilities of modern synchrotron beamlines have profoundly impacted structure-based drug design, particularly through the implementation of fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) platforms. The FragMAX platform at BioMAX exemplifies this integration, enabling direct screening of fragment libraries against pharmaceutical targets at the beamline [1]. This approach leverages the high-throughput capabilities of fourth-generation beamlines to rapidly identify and characterize weak-binding fragments that can be developed into potent drug leads.

The future development of synchrotron-based structural biology will focus on further integration of complementary techniques, including small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [1]. This multi-modal approach will provide comprehensive insights into macromolecular function across multiple spatial and temporal resolutions. Additionally, ongoing developments in sample delivery methods aim to further reduce sample requirements, potentially approaching the theoretical minimum of 450 ng of protein per complete dataset [2]. These advancements will continue to expand the accessible range of biological targets, particularly for proteins that are difficult to express or purify in large quantities.

As synchrotron facilities continue to evolve, the accidental tool that revolutionized structural biology has become an indispensable foundation for understanding biological mechanism and developing therapeutic interventions. The integration of advanced beamline capabilities with innovative experimental approaches ensures that synchrotron-based structural biology will remain central to biological discovery for decades to come.

Synchrotron radiation, the powerful electromagnetic light produced by particle accelerators, has fundamentally transformed structural biology. Within protein crystallography, its unique properties have enabled researchers to determine the three-dimensional structures of biological molecules with unprecedented speed and precision, providing critical insights for understanding disease mechanisms and guiding rational drug design [4] [5]. This technical guide details the core properties of this exceptional light source and its pivotal role in modern scientific discovery.

Key Properties of Synchrotron Radiation

The utility of synchrotron radiation in protein crystallography stems from a combination of exceptional properties that far surpass those of conventional laboratory X-ray sources.

Table 1: Key Properties of Synchrotron Radiation and Their Impact on Protein Crystallography

| Property | Technical Description | Significance for Protein Crystallography |

|---|---|---|

| High Brilliance | Ultra-high photon flux per unit area, solid angle, and bandwidth [6]. | Enables data collection from micro-crystals and weakly diffracting samples [4]. |

| Broad Spectrum | Continuous wavelength range from infrared to hard X-rays [4]. | Allows tuning to optimal wavelengths for experiments like MAD phasing [4]. |

| High Collimation | Light emitted with very low divergence (nearly parallel beams) [4]. | Results in higher resolution diffraction data and sharper spots on detectors. |

| Pulsed Time Structure | Light emitted in short, femtosecond-to-picosecond pulses [6]. | Facilitates time-resolved studies to observe molecular dynamics in real-time [6]. |

| Partial Coherence | High degree of spatial coherence [6]. | Enables advanced imaging techniques and methods to mitigate radiation damage. |

| Polarization | Primarily linearly polarized in the plane of the electron orbit. | Reduces background noise in certain experimental geometries. |

The historical impact is clear; early experiments demonstrated that synchrotron radiation could provide at least 60 times greater diffracted intensity than a sealed X-ray tube, allowing data collection to higher resolution from smaller crystals [4].

The Role of Synchrotron Light in Protein Crystallography

The properties of synchrotron radiation directly address key challenges in protein crystallography.

Overcoming Technical Limitations

The high intensity and brilliance of synchrotron beams mitigate the primary bottlenecks of crystallography. Researchers can now work with crystals that are orders of magnitude smaller than previously possible. Furthermore, the tunable nature of the source allows for the optimization of anomalous scattering, which is fundamental to solving the crystallographic "phase problem" [4].

Enabling Cutting-Edge Methodologies

- Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX): Performed at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) like the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), this technique uses ultra-bright, femtosecond pulses to obtain high-resolution data from a stream of microcrystals before the onset of radiation damage [6].

- Time-Resolved Studies: The pulsed time structure of synchrotrons and XFELs enables "molecular movies," allowing scientists to image transient states and functional dynamics of proteins at atomic resolution [6].

- Operando and In Situ Studies: The high penetration of high-energy beams allows for novel experimental setups, such as studying the atomic structure of battery electrode materials while the battery is charging or discharging [7].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Leveraging synchrotron light requires specialized experimental setups and protocols.

Key Experimental Methodology: Operando X-ray Diffraction

This protocol is used to study structural changes in functional devices, such as a battery, in real-time [7].

- Sample Environment Preparation: A specially designed battery test cell is constructed. This cell must allow the X-ray beam to penetrate through the entire battery assembly, including its casing and electrodes [7].

- Synchrotron Beamline Setup: The experiment is conducted at a beamline equipped for high-energy, penetrating diffraction. The beam is focused on the sample [7].

- Data Collection: The battery is connected to a cycler and placed in the beam path. A sequence of high-resolution X-ray diffraction images is collected continuously at regular intervals (e.g., every 10-30 seconds) during battery charge and discharge cycles [7].

- Data Processing & Analysis: The series of diffraction images are processed to create an "X-ray movie." Changes in the diffraction patterns are analyzed to reveal how the atomic structure of the electrode materials evolves during operation [7].

Key Experimental Methodology: Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX)

This protocol describes the general workflow for collecting data at an XFEL [6].

- Sample Delivery: A suspension of microcrystals is injected into the path of the X-ray pulses in a continuous stream or as droplets.

- Pump-Probe Initiation (for time-resolved studies): A laser pulse ("pump") is fired to initiate a photochemical reaction in the crystals. After a precisely controlled time delay, an X-ray pulse ("probe") arrives to collect the diffraction pattern.

- Data Acquisition: The ultrashort X-ray pulse (<100 femtoseconds) diffracts from a single microcrystal, and a "snapshot" is recorded on a high-speed detector before the crystal is destroyed. This process is repeated for thousands of crystals in random orientations.

- "Still" Shot Indexing: The individual diffraction snapshots are indexed and integrated using specialized software.

- Data Merging: The integrated intensities from hundreds of thousands of snapshots are merged to produce a complete, high-resolution dataset.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a time-resolved SFX experiment at an XFEL.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful synchrotron-based research relies on specialized tools and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Synchrotron-Based Research

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Sample Cells | Sample Environment | Allows X-ray penetration and controlled conditions for operando studies (e.g., of batteries) [7]. |

| Grating Monochromators | Beamline Optics | Selects a specific wavelength from the broad synchrotron spectrum for the experiment [6]. |

| Laue Analyzer Crystals | Instrumentation | Used in advanced spectrometers to achieve high energy resolution for emission studies [6]. |

| Serial Crystallography Injectors | Sample Delivery | Delivers a continuous stream of microcrystals into the X-ray beam for SFX experiments [6]. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Workshop (SRW) | Software | A powerful tool for simulating the propagation of synchrotron radiation through beamline optics and samples [8]. |

| Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks (cGANs) | Software/Data Processing | A machine learning approach used to suppress artifacts (e.g., from air) in phase-contrast micro-CT data, improving visualization [6]. |

The unique properties of synchrotron radiation—high brilliance, broad spectrum, and pulsed time structure—have made it an indispensable tool for protein crystallography. By enabling the study of smaller crystals, more complex molecular machines, and faster dynamic processes, it continues to push the boundaries of structural biology. As synchrotron facilities worldwide undergo continuous upgrades, the brightness and capabilities of these light sources will only increase, ensuring their central role in scientific innovation and drug development for years to come.

Synchrotron light sources have revolutionized the field of structural biology, enabling scientists to determine the three-dimensional structures of biological molecules at atomic resolution. For protein crystallography, which informs on the function of biological molecules and drives processes in drug development and green chemistry, synchrotron radiation has been transformative [1]. The growth of structural information is evidenced by the Protein Data Bank, which has expanded from an initial 7 structures to over 220,000 structures today, largely enabled by synchrotron-based macromolecular crystallography (MX) [1]. This technical guide traces the evolution of synchrotron technology through four distinct generations, examining how each advancement has expanded capabilities for protein structure determination within the broader context of a thesis on the role of synchrotron facilities in protein crystallography research.

The exceptional importance of X-rays was recognized from their discovery in 1895, with Röntgen receiving the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 [9]. However, synchrotron radiation itself was first observed decades later on April 24, 1947, at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York [9] [10]. This discovery initiated a technological revolution that has seen the brightness of X-ray sources increase by approximately 12 orders of magnitude over 60 years, with each generation of synchrotrons bringing new capabilities to protein crystallography [11].

The Theoretical Foundation of Synchrotron Radiation

The theoretical basis for synchrotron radiation dates to the late 19th century. In 1897, Larmor derived an expression for the instantaneous total power radiated by an accelerated charged particle from classical electrodynamics [9]. Liénard extended this result in 1898 to the case of a relativistic particle undergoing centripetal acceleration in a circular trajectory, showing the radiated power to be proportional to (E/mc²)⁴/R², where E is particle energy, m is the rest mass, and R is the trajectory radius [9]. Later work by Schwinger in the 1940s provided a detailed classical theory of radiation from accelerated relativistic electrons, demonstrating major features including the strongly forward-peaked distribution that gives synchrotron radiation its highly collimated property [9].

Synchrotron radiation is characterized by several unique properties that make it particularly valuable for protein crystallography: high brilliance (photons per second per unit area per solid angle per bandwidth), broad spectral distribution from infrared to hard X-rays, strong polarization, and pulsed time structure [11]. The spectral distribution is characterized by the critical energy (εc), which depends on the electron beam energy (Ee) and magnetic field (B), expressed as εc(keV) = 0.665Ee²(GeV)B(T) [11]. For a typical 3 GeV storage ring, this provides useful photon energies up to about 30 keV, ideal for protein crystallography experiments.

First Generation: Parasitic Facilities

The first generation of synchrotron radiation facilities emerged as parasitic operations on accelerators built primarily for high-energy physics research [9] [12]. The first experimental program using synchrotron radiation began in 1961 when the National Bureau of Standards modified its 180-MeV electron synchrotron to allow access to radiation via a tangent section into the machine's vacuum system [9]. This facility, named SURF (Synchrotron Ultraviolet Radiation Facility), began measurements to determine the potential of synchrotron radiation for standards and spectroscopy in the ultraviolet region [9].

Early first-generation facilities also included the 1.15-GeV synchrotron at Frascati laboratory near Rome, where researchers measured absorption in thin metal films, and the 750-MeV synchrotron in Tokyo, where scientists formed the INS-SOR group and made measurements of soft X-ray absorption spectra of solids by 1965 [9]. A significant advancement came with the use of the 6-GeV Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, which began operating in 1964 and provided synchrotron radiation at wavelengths in the X-ray region down to 0.1 Å [9]. Despite their parasitic nature, these first-generation facilities demonstrated the potential of synchrotron radiation for scientific research, particularly in spectroscopy and absorption measurements.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of First-Generation Synchrotron Facilities

| Facility | Location | Energy | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NBS (SURF) | USA | 180 MeV | Ultraviolet standards and spectroscopy |

| Frascati Synchrotron | Italy | 1.15 GeV | Absorption in thin metal films |

| INS-SOR | Japan | 750 MeV | Soft X-ray absorption spectra of solids |

| DESY | Germany | 6 GeV | Spectral distribution verification, absorption measurements |

Second Generation: Dedicated Storage Rings

Second-generation synchrotron light sources represented a significant advancement through the development of dedicated electron storage rings designed specifically to produce synchrotron radiation [12]. These facilities, including BESSY I in Berlin and the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at Brookhaven, employed storage rings where electrons circulated at constant energy, with radiation loss replenished by RF power [11]. The key innovation was that these facilities were optimized specifically for synchrotron radiation production rather than particle physics.

The transition to storage rings provided more stable and reliable beams for experimental users. These facilities incorporated bending magnets as the primary source of synchrotron radiation, where electrons were deflected by uniform magnetic fields to produce broadband radiation [12]. The second generation established the dedicated user facility model, where scientists from various disciplines could apply for beamtime to conduct experiments, laying the foundation for the expanding scientific applications of synchrotron radiation.

Third Generation: Insertion Devices and Beamline Optimization

Third-generation synchrotron light sources marked another substantial leap forward by optimizing the intensity of radiation through the incorporation of long straight sections in the storage rings for "insertion devices" - undulator and wiggler magnets [12]. These facilities, including the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in France, the Advanced Photon Source (APS) in the United States, and SPring-8 in Japan, represented the state of the art for decades [13].

Insertion devices dramatically enhanced the capabilities of synchrotron sources. Wigglers create a broad but intense beam of incoherent light, effectively extending the usable photon energy range to higher energies through larger magnetic fields [11]. Undulators, consisting of periodic magnet structures with many periods, produce a narrower and significantly more intense beam of coherent light through constructive interference of emission as electrons traverse each period [10]. The radiation from undulators is characterized by the dimensionless deflection parameter K, calculated as K = 0.934λu(cm)Bo(T), where K < 1 defines an undulator [11].

For protein crystallography, third-generation sources enabled routine high-resolution structure determination through dedicated macromolecular crystallography beamlines. The high brilliance allowed for smaller crystals and faster data collection, while the tunability of undulator radiation facilitated advanced techniques like multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) phasing [1].

Table 2: Major Third-Generation Synchrotron Facilities for Protein Crystallography

| Facility | Location | Energy | Notable MX Beamlines |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESRF | Grenoble, France | 6 GeV | ID23, ID29, ID30 |

| APS | Lemont, USA | 7 GeV | GM/CA-CAT, NE-CAT, SBC-CAT |

| SPring-8 | Hyōgo, Japan | 8 GeV | BL41XU, BL32XU |

| Diamond Light Source | Oxfordshire, UK | 3 GeV | I02, I03, I04, I24 |

Fourth Generation: Multi-Bend Achromats and Diffraction Limited Storage Rings

Fourth-generation synchrotron sources represent the current frontier, characterized by the implementation of multi-bend achromat (MBA) lattices in storage ring design to achieve dramatically reduced electron beam emittance [1] [10]. This technology, pioneered by MAX IV in Lund, Sweden, which opened in 2016, enables storage rings to approach the diffraction limit across a wide energy range [1] [14]. The MBA concept provides a way to control the trajectories of giga-electron-volt electrons to micrometer precision, resulting in X-ray beams with significantly increased brightness and coherence [10].

The revolutionary improvement in fourth-generation sources is quantified by brightness (or brilliance), which describes how much light a source emits per second and unit area into each solid angle over a particular bandwidth [10]. For an intrinsically incoherent source like a synchrotron, the coherence of the X-ray beam is directly proportional to the source size and inversely proportional to the distance at which it is measured [14]. The MBA lattice minimizes both the transverse size and divergence of the electron beam, increasing the coherent flux by up to a factor of 200 in the 6-10 keV energy range compared to third-generation sources [14].

Following MAX IV, other facilities have implemented MBA upgrades, including ESRF-EBS (Extremely Brilliant Source) in 2020, which achieved a 30-fold increase in brightness, and Sirius at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory [10]. Other major facilities including the Advanced Photon Source, Advanced Light Source, SPring-8, and Diamond Light Source are pursuing similar upgrades [10]. This new generation enables techniques that demand high coherence, such as ptychography and coherent diffraction imaging, while dramatically improving the performance of more established methods like protein crystallography [14].

Table 3: Comparison of Synchrotron Generations

| Characteristic | First Generation | Second Generation | Third Generation | Fourth Generation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Bending magnets from particle physics accelerators | Bending magnets in dedicated storage rings | Undulators in optimized storage rings | Undulators in MBA lattice storage rings |

| Emittance | High | Medium | Low | Ultra-low (diffraction limited) |

| Brightness | Low | Medium | High | Very high (100-1000× improvement over 3rd gen) |

| Coherence | Minimal | Partial | Significant | High (full transverse coherence for softer X-rays) |

| Example Facilities | DESY, SURF | BESSY I, NSLS | ESRF, APS, SPring-8 | MAX IV, ESRF-EBS, Sirius |

Synchrotron Applications in Protein Crystallography: Methodologies and Workflows

Evolution of Crystallography Techniques at Synchrotrons

The development of synchrotron sources has directly enabled increasingly sophisticated protein crystallography methodologies. Traditional macromolecular crystallography (MX) requires large, well-diffracting crystals and involves collecting complete datasets from single crystals at cryogenic temperatures to mitigate radiation damage [1]. At third-generation sources, microfocus beamlines allowed work with smaller crystals (10-50 μm), while tunable beams enabled multi-wavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) phasing [1].

The advent of fourth-generation sources has facilitated the adoption of serial crystallography approaches, particularly serial synchrotron crystallography (SSX) [1]. This method involves collecting diffraction patterns from thousands of microcrystals, with each crystal exposed only once to X-rays before replacement [2]. SSX can be performed at room temperature, enabling time-resolved studies of enzymatic reactions and the investigation of membrane proteins and other challenging systems that typically produce only microcrystals [1].

Diagram 1: Protein Crystallography Workflows

Serial crystallography at synchrotrons, often called serial millisecond crystallography (SMX), has been particularly advanced by fourth-generation sources [2]. The high brightness and coherence of MBA-based storage rings enable the collection of usable diffraction patterns from micrometer-sized crystals, while the stability of these sources supports the high data rates required for serial approaches [1].

Two primary sample delivery methods have been developed for serial crystallography. Fixed-target approaches mount microcrystals on a solid support that is raster-scanned through the X-ray beam, minimizing sample consumption by precisely positioning crystals [2]. Liquid injection methods continuously deliver crystal slurries to the interaction point via thin tubes or high-viscosity extruders, allowing high data rates but typically consuming more sample [2]. For a complete dataset requiring approximately 10,000 indexed patterns from 4×4×4 μm microcrystals with a protein concentration of ~700 mg/mL, the theoretical minimum sample consumption is approximately 450 ng of protein [2].

Time-resolved serial crystallography (TR-SX) enables the study of biomolecular reaction mechanisms by initiating reactions through light activation (for photosensitive proteins) or rapid mixing of substrates with enzymes [2]. The mix-and-inject serial crystallography (MISC) approach combines reactants with protein crystals immediately before X-ray exposure to study structural changes on timescales from seconds to sub-milliseconds [2].

Table 4: Sample Delivery Methods for Serial Crystallography

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Sample Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Target | Crystals mounted on solid support and raster-scanned | Minimal sample consumption, compatible with various sample environments | Lower data rate, potential crystal harvesting issues | As low as micrograms |

| Liquid Injection | Crystal slurry continuously delivered to beam | High data rate, efficient for abundant samples | High sample consumption, jetting stability issues | Typically milligrams |

| High-Viscosity Extrusion | Crystal suspension in viscous matrix | Reduced flow speed, lower sample consumption | Potential background scattering, matrix compatibility | Hundreds of micrograms |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallization Screens | Sparse matrix of chemical conditions to promote crystal formation | Initial crystal screening and optimization |

| Cryoprotectants | Prevent ice formation during cryo-cooling | Crystal preservation for data collection at cryogenic temperatures |

| LCP (Lipidic Cubic Phase) | Membrane mimetic environment for crystallization | Particularly for membrane proteins |

| High-Viscosity Carriers | Matrix for crystal suspension and delivery | High-viscosity extrusion serial crystallography |

| Microfluidic Chips | Miniaturized platforms for crystal growth and manipulation | High-throughput screening and fixed-target data collection |

| In Situ Crystallization Plates | Integrated crystal growth and data collection platforms | Minimizing crystal handling damage |

Case Study: MAX IV - A Fourth-Generation Facility for Protein Crystallography

The MAX IV Laboratory in Lund, Sweden represents the pioneering implementation of fourth-generation synchrotron technology, featuring a 3 GeV storage ring with a 528 m circumference that achieves a horizontal emittance of 328 pm rad through its multi-bend achromat lattice [1]. This facility operates two dedicated protein crystallography beamlines - BioMAX and MicroMAX - designed to complement each other while maintaining some experimental overlap [1].

BioMAX serves as a versatile, stable, high-throughput beamline catering to most protein crystallography experiments [1]. Its technical specifications include an in-vacuum, room temperature permanent magnet undulator with an 18 mm magnetic period, an Si(111) double-crystal monochromator, and Kirkpatrick-Baez focusing mirrors that provide a stable beam between 6-24 keV [1]. The beamline offers four major focusing modes (100×100, 50×50, 20×20, and 20×5 μm²) and is equipped with an ISARA robotics sample changer capable of storing 464 samples [1]. Continuous fast energy scanning enables measurement of X-ray absorption spectra near absorption edges in approximately one second [1].

MicroMAX, operational since 2024, specializes in serial crystallography including time-resolved experiments [1]. Designed to exploit the special characteristics of fourth-generation beamlines, it enables data collection from micrometre-sized crystals using serial approaches, particularly valuable for membrane proteins and other challenging systems that typically produce only microcrystal slurries [1]. Additionally, MAX IV hosts the FragMAX platform for fragment-based drug discovery and the FemtoMAX beamline for studying ultrafast structural dynamics in proteins [1].

The performance advantages of fourth-generation sources are quantifiable in experimental outcomes. At the NanoMAX beamline of MAX IV, Bragg ptychography experiments demonstrated the ability to retrieve high-quality images of crystalline samples with unprecedented quality, achieving results that would not be possible with third-generation sources due to limited coherent flux [14]. The increased available coherent flux produces datasets with sufficient information to overcome experimental limitations such as deteriorated scanning conditions, making advanced microscopy methods more accessible and suitable for high-throughput studies [14].

The evolution from first-generation to fourth-generation synchrotron sources represents a remarkable technological journey that has fundamentally transformed protein crystallography and structural biology. Each generation has brought orders-of-magnitude improvements in source performance, particularly in brilliance and coherence, enabling increasingly sophisticated experiments with smaller samples, higher resolution, and time-resolved capabilities.

The ongoing development of synchrotron light sources continues to push scientific boundaries. Future directions include further optimization of MBA lattices, development of diffraction-limited storage rings for higher energy ranges, and increased integration between storage rings and free-electron lasers [10]. The challenges of fourth-generation facilities - including managing vast data volumes, developing high-speed detectors, and creating automated experimental workflows - are being addressed through synergies with X-ray free-electron laser facilities [10].

For protein crystallography, fourth-generation synchrotrons enable structural biology to address increasingly complex biological questions. The integration of crystallography with complementary techniques like cryo-electron microscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering provides comprehensive views of biological systems [1]. High-throughput approaches facilitated by these sources allow crystallography to be used as a screening method in drug discovery, while time-resolved studies provide "molecular movies" of enzymatic reactions and biological processes [1] [2].

In conclusion, the generational progress in synchrotron technology has positioned these facilities as indispensable tools for understanding biological systems at atomic resolution. From their origins as parasitic operations on particle physics accelerators to the dedicated, ultra-bright sources of today, synchrotrons have continually expanded the frontiers of structural biology. As fourth-generation facilities mature and new technologies emerge, synchrotron-based protein crystallography will continue to drive advances in basic science, drug development, and our fundamental understanding of life processes.

The determination of macromolecular structures through X-ray crystallography has been revolutionized by the development of anomalous diffraction methods, which directly address the fundamental phase problem in crystallography. These techniques, predominantly multi-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) and single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD), now dominate de novo structure determination of biological macromolecules. This transformation has been enabled by tunable X-ray sources at synchrotron facilities, which provide the precise wavelength control required to exploit elemental absorption edges. Within the broader context of synchrotron facilities' role in structural biology, this technical guide examines the physical principles, methodologies, and cutting-edge applications of anomalous dispersion techniques that have become cornerstone approaches in modern drug development and protein engineering.

The Phase Problem in X-ray Crystallography

Fundamental Challenge

In X-ray crystallography, diffraction patterns from crystals contain decisive information for determining atomic-level structures. When X-rays scatter from a crystal, we measure the intensities of the diffracted waves, from which we can derive the amplitudes of the structure factors. However, the experimental measurement systematically loses information about the phase of these diffracted waves [15] [16]. This constitutes the fundamental phase problem: without phase information, atomic positions cannot be directly determined from diffraction data alone [17].

The electron density ρ(xyz) at a position in the unit cell is calculated by the Fourier synthesis: [ ρ(xyz) = \frac{1}{V} \sum{h} \sum{k} \sum{l} |F{hkl}| \cos[2π(hx + ky + lz) - α{hkl}] ] where |Fhkl| represents the structure factor amplitude and α_hkl is the required phase angle for each reflection (hkl) [17]. The critical importance of phases is visually demonstrated when calculated electron density maps using correct phases yield interpretable atomic structures, while maps with incorrect phases are unrecognizable.

Historical Solutions

Traditional approaches to solving the phase problem in macromolecular crystallography included:

- Multiple Isomorphous Replacement (MIR): Using heavy-atom derivatives to create isomorphic crystals [15]

- Molecular Replacement: Using known structures of homologous proteins [16] [17]

- Direct Methods: Extracting phase information from intensity relationships (effective only at very high resolution) [17]

These methods presented significant challenges including the need for multiple crystals, difficulties finding suitable heavy-atom derivatives, and limitations for novel structures without known homologs.

Physical Basis of Anomalous Scattering

Theoretical Foundation

Anomalous scattering arises from interactions between X-rays and bound electrons in atomic orbitals. Unlike the "normal" Thomson scattering from free electrons, anomalous scattering occurs when the X-ray frequency approaches resonant frequencies of electronic transitions [15]. This phenomenon perturbs the atomic scattering factor, making it a complex quantity:

[ f = f^\circ + f^\Delta = f^\circ + |f^\Delta|e^{iδ} = f^\circ + f' + if'' ]

where:

- (f^\circ) is the normal atomic scattering factor

- (f') is the real part of the anomalous dispersion correction

- (f'') is the imaginary part of the anomalous dispersion correction [15] [18]

The (f'') component is related to absorption and is maximum at the absorption edge, while (f') decreases sharply through the absorption edge [15]. These wavelength-dependent effects create measurable differences in diffraction intensities that contain phase information.

Breakdown of Friedel's Law

In conventional scattering, Friedel's law states that |F(hkl)| = |F(-h-k-l)| for a given reflection and its Friedel mate. Anomalous scattering causes breakdown of this symmetry, creating measurable differences between |F(+)| and |F(-)| [19]. These anomalous differences provide the key experimental observables that enable phase determination in SAD and MAD methods.

Table 1: Characteristics of Anomalous Scattering Components

| Component | Symbol | Physical Meaning | Spectral Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal scattering | (f^\circ) | Thomson scattering from free electrons | Decreases with scattering angle |

| Real anomalous component | (f') | Dispersion correction | Decreases sharply at absorption edge |

| Imaginary anomalous component | (f'') | Absorption component | Maximum at absorption edge |

Anomalous Diffraction Methodologies

Multi-Wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (MAD)

The MAD method exploits anomalous scattering effects at multiple wavelengths near an absorption edge of an incorporated element. By collecting data at different wavelengths, the variations in both (f') and (f'') components provide sufficient information to determine phases [15] [18].

Key requirements for MAD phasing:

- Tunable X-ray source (synchrotron radiation)

- Element with strong anomalous scattering signal (selenium, sulfur, metals)

- Data collection at 2-3 wavelengths optimally chosen around absorption edge

The typical MAD experiment utilizes:

- Remote wavelength (above edge, low (f''))

- Peak wavelength (maximum (f''))

- Inflection point (maximum change in (f'))

Single-Wavelength Anomalous Diffraction (SAD)

SAD phasing uses anomalous diffraction data collected at a single wavelength, making it more efficient but potentially more challenging [19]. The technique leverages both the anomalous differences and the heavy-atom substructure information to resolve phase ambiguities [19].

Advantages of SAD:

- Single data set collection

- No non-isomorphism issues

- Does not require scanning across absorption edge

- Wider range of usable anomalous scatterers [19]

SAD has become the dominant method for de novo structure determination due to its efficiency and reliability, particularly with selenomethionine-labeled proteins.

Synchrotron Enabling Technology

Synchrotron radiation provides the essential characteristics for anomalous diffraction experiments:

- High spectral brightness: Enables measurement of weak anomalous signals

- Tunability: Precise wavelength selection for optimizing anomalous signals

- Beam stability: Essential for accurate measurement of small intensity differences [20]

The development of third-generation synchrotron sources (ESRF, APS, SPring-8) dramatically expanded MAD and SAD capabilities through increased flux and beam stability [20]. Modern facilities operate in "top-up" mode to maximize X-ray output and stability, improving accuracy in measuring weak anomalous signals [20].

Current Source Developments

Recent advancements continue to enhance anomalous diffraction capabilities:

- Ultimate storage ring designs: MAX IV and ESRF Upgrade Phase II promise increased coherence and flux density [20]

- X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs): Enable time-resolved studies and damage-free diffraction [20] [21]

- Two-colour XFEL operation: Simultaneous data collection at two wavelengths for MAD phasing [21]

Table 2: Evolution of Synchrotron Sources for Anomalous Diffraction

| Generation | Key Facilities | Impact on Anomalous Diffraction |

|---|---|---|

| First Generation | SPEAR, DORIS | Demonstrated tunability for absorption spectroscopy |

| Second Generation | NSLS, Photon Factory | Early MAD experiments |

| Third Generation | ESRF, APS, SPring-8 | Routine MAD/SAD phasing, automation |

| Fourth Generation | MAX IV, ESRF-EBS | Enhanced signal from microcrystals |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MAD Data Collection Protocol

Sample Preparation

- Incorporate anomalous scatterers (selenomethionine, heavy atoms)

- Cryo-cool crystals for radiation damage reduction

- Characterize crystal quality and check for anisotropy

Absorption Edge Determination

- Collect X-ray fluorescence scan around predicted edge

- Identify precise inflection point (maximum f') and peak (maximum f")

- Select remote wavelength (high energy side of edge)

Data Collection Strategy

- Collect complete dataset at each wavelength (peak, inflection, remote)

- Maintain similar completeness, resolution, and redundancy

- Use inverse beam geometry or high redundancy to measure Friedel mates closely in time

Critical Parameters

- Resolution: As high as possible (typically 2.0-2.5 Å minimum)

- Redundancy: High to measure weak anomalous signal accurately

- Completeness: >95% for overall and anomalous signals

- Signal-to-noise:

Two-Colour XFEL MAD Protocol

Recent developments at XFELs enable simultaneous two-colour data collection:

- Beam generation: Split undulator operation produces two colours with large energy separation [21]

- Spatial separation: Two diffraction patterns recorded simultaneously on one detector [21]

- Data processing: Specialized pipelines (CASS, Cheetah) handle wavelength assignment and integration [21]

- Phase determination: MAD phasing from simultaneous two-wavelength datasets [21]

This approach halves sample consumption and eliminates non-isomorphism between wavelengths, demonstrating the ongoing innovation in anomalous diffraction methodologies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful anomalous diffraction experiments require careful selection and preparation of phasing reagents. The table below summarizes key reagents and their applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Anomalous Diffraction Phasing

| Reagent/Element | Typical Incorporation Method | Absorption Edge | Applications & Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selenomethionine | Biosynthetic incorporation | Se K-edge (0.9795 Å) | Standard for MAD/SAD; minimal perturbation |

| Iodine | Soaking or chemical modification | I K-edge (0.3748 Å) | Strong anomalous signal |

| Lanthanides (Gd, Sm, Yb) | Soaking or engineered tags | L-edges (1.0-1.9 Å) | Very strong anomalous signal |

| Zinc, Iron, Copper | Native metalloproteins | K-edges | Phasing without modification |

| Sulfur | Native methionine and cysteine | S K-edge (5.02 Å) | Native SAD phasing |

| Halogen compounds | Soaking or covalent modification | Varies | Convenient for crystal soaking |

Visualization of Methodologies

Phase Problem in Crystallography

MAD Experimental Workflow

Impact and Current Applications

Anomalous diffraction methods have transformed structural biology, with MAD and SAD now dominating de novo protein structure determination [15]. Approximately 90% of X-ray single-crystal structure determinations now utilize synchrotron sources [20], with anomalous phasing playing a crucial role.

Key impact areas:

- Drug discovery: Structure-based drug design against novel targets

- Enzyme mechanisms: Understanding catalytic centers in metalloenzymes

- Membrane proteins: Structural insights into transporters and receptors

- Macromolecular complexes: Elucidating molecular machines

The ongoing development of XFEL sources has enabled two-colour MAD phasing, which provides more accurate phase angles than single-colour phasing while halving sample consumption [21]. This represents the cutting edge of anomalous diffraction methodology.

Tunable wavelengths at synchrotron facilities have fundamentally enabled the anomalous dispersion techniques that now dominate macromolecular structure determination. The physical phenomenon of anomalous scattering, when coupled with precision wavelength control, provides a powerful solution to the phase problem that once limited crystallographic progress. As synchrotron and XFEL technologies continue to advance with brighter beams, better detectors, and innovative methodologies like two-colour operation, anomalous diffraction will remain essential for elucidating biological structures and mechanisms relevant to therapeutic development. The integration of these technical capabilities with robust experimental protocols ensures that MAD and SAD phasing will continue to drive discoveries in structural biology and drug development for the foreseeable future.

Beyond Static Structures: Advanced Synchrotron Methods Driving Discovery

The evolution of structural biology has been profoundly accelerated by the integration of high-throughput methodologies within synchrotron facilities. These advancements have transformed macromolecular crystallography (MX), enabling a dramatic increase in the pace of structure determination, particularly for challenging targets like membrane proteins. The progress in X-ray microbeam applications using synchrotron radiation has been fundamental to structure determination from macromolecular microcrystals, such as small in meso crystals [22]. Synchrotron radiation provides highly brilliant X-ray beams across a wide range of wavelengths, improving data quality while simultaneously decreasing the crystal size required for successful structure determination [22]. This technological revolution has positioned synchrotron MX beamlines as the primary source for the majority of X-ray structures deposited annually in the Protein Data Bank, which contained over 120,000 structures by September 2016 and continues to grow exponentially [22].

The critical importance of high-throughput crystallography extends beyond mere efficiency. It enables researchers to tackle scientifically pressing targets that were previously inaccessible, including human membrane proteins with direct relevance to disease mechanisms and drug discovery [22]. The demanding nature of these targets—often yielding crystals with limited size and diffracting power—has driven the development of sophisticated experimental apparatus, novel data-collection strategies, and automated processing protocols. Within this context, synchrotron facilities have emerged as indispensable hubs, providing the specialized instrumentation and computational infrastructure necessary to support the streamlined workflows from crystal to structure that define modern structural biology.

Core Technologies Enabling High-Throughput workflows

Microfocus Beamlines and Advanced Detection

The development of microfocus beamlines represents a cornerstone of high-throughput crystallography. These specialized beamlines provide a high-flux microbeam with a focal size smaller than a few tens of micrometers and a flux density exceeding 10¹⁰ photons μm⁻² s⁻¹ at the sample position [22]. The relationship between the number of incident photons and the obtained resolution limit is direct; as crystals are exposed to more X-ray photons, the achievable resolution improves significantly [22]. For microcrystals, which have a smaller diffraction volume and consequently weaker diffraction intensities, maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio is paramount. Using a high-intensity microbeam with a size comparable to the target crystal is therefore essential for successful structure determination from microcrystalline samples [22].

High-speed detectors represent another critical technological advancement. Modern detectors with fast readout capabilities dramatically increase the number of datasets that can be collected within a practical beamtime allocation. This speed is crucial for serial crystallography approaches, which rely on collecting data from hundreds or thousands of crystals. When combined with automated sample changers that allow rapid sample exchange without manual intervention, these systems create a seamless pipeline for high-volume data acquisition. Furthermore, the development of sophisticated software has made it feasible to process and merge the multiple datasets generated by these methods, completing the technological ecosystem for high-throughput operations [22].

Serial Crystallography Methods

Inspired by the success of serial femtosecond crystallography (SFX) with X-ray free-electron lasers, serial synchrotron crystallography (SSX) has emerged as a powerful method for high-throughput data collection at synchrotron microfocus beamlines [22]. This method overcomes the radiation-dose limit in diffraction data collection by distributing the dose across a sufficient number of microcrystals [22]. SSX encompasses two primary approaches:

- Fixed-target SSX: In this method, large numbers of diffraction images are collected through two-dimensional raster scanning from multiple crystals loaded on specialized substrates such as nylon loops or thin films [22].

- Injection-based SSX: This approach utilizes a continuous flow of a microcrystal suspension through a capillary or injectors, often in combination with a high-viscosity medium to maintain crystal stability during data collection [22].

The transition toward multi-crystal data collection strategies marks a significant shift in crystallographic methodology. While traditional approaches relied on single, well-diffracting crystals, modern high-throughput workflows frequently employ data collection from dozens of crystals [22]. This approach is particularly valuable for challenging systems where crystal size or quality is limited, as it allows researchers to merge partial datasets from multiple crystals to obtain a complete, high-quality structure.

Time-Resolved and Cryo-Trapping Methodologies

Recent advancements in time-resolved crystallography have expanded the capabilities of high-throughput synchrotron-based research. The introduction of integrated benchtop devices like the spitrobot-2 has enabled time-resolved cryo-trapping crystallography with unprecedented time resolution [23]. This automated crystal plunging system permits reaction quenching via cryo-trapping with a delay time of under 25 milliseconds, facilitating the observation of conformational changes and ligand binding events that occur on fast timescales [23].

A key advantage of cryo-trapping approaches lies in their ability to uncouple sample preparation from data collection. Researchers can prepare their samples well in advance of a beamtime, focusing exclusively on data collection during their synchrotron access period [23]. This methodology is compatible with established high-throughput infrastructure and automated data-processing routines, making it particularly valuable for studying enzymatic mechanisms and transient reaction intermediates. Furthermore, its compatibility with both macroscopic and micro-crystals, as well as canonical rotation and serial data collection methods, makes it a versatile tool in the high-throughput crystallographer's arsenal [23].

High-Throughput Workflow: From Crystal to Structure

Integrated Experimental Pipeline

The high-throughput crystallography workflow represents an integrated pipeline that transforms protein crystals into atomic structures through a series of optimized, interconnected steps. The workflow begins with crystal generation and proceeds through sample mounting, data collection, and computational analysis, with each stage incorporating specialized technologies to maximize efficiency and success rates.

Figure 1: High-Throughput Crystallography Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline from crystal generation to structure analysis, highlighting the automated transitions between stages that enable rapid structure determination.

Data Collection Strategies and Decision Matrix

Selecting the appropriate data collection strategy is crucial for successful high-throughput crystallography. The choice depends on multiple factors, including crystal characteristics, scientific objectives, and available instrumentation. The table below summarizes the key methodologies and their optimal applications.

Table 1: Data Collection Strategies in High-Throughput Crystallography

| Method | Crystal Requirements | Radiation Damage Management | Time Resolution | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Crystal Rotation | Large, well-diffracting crystals (>20 μm) | Cryo-cooling, dose attenuation | Seconds to minutes | Standard structure determination, ligand screening |

| Multi-Crystal Merging | Multiple microcrystals (5-20 μm) | Dose fractionation across crystals | Minutes to hours | Challenging targets, difficult-to-grow crystals |

| Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SSX) | Hundreds to thousands of microcrystals (<10 μm) | Ultra-low dose per crystal | Milliseconds to seconds | Time-resolved studies, radiation-sensitive systems |

| Cryo-Trapping TRX | Macroscopic or microcrystals | Rapid vitrification of intermediates | 25 ms and longer [23] | Enzymatic mechanisms, reaction intermediates |

The implementation of these strategies at synchrotron facilities has been facilitated by specialized sample handling technologies. For fixed-target approaches, crystals are mounted on specialized substrates that allow automated rastering through the X-ray beam. For injection-based methods, high-viscosity injectors enable stable delivery of crystal suspensions while minimizing sample consumption [22]. The compatibility of these approaches with the SPINE standard allows direct integration with high-throughput infrastructure available at most synchrotrons, including automated sample changers and sample tracking systems [23].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of high-throughput crystallography relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials that optimize each stage of the workflow. The table below details key solutions and their specific functions in the experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Crystallography

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lipidic Mesophases | Membrane protein crystallization matrix | Essential for in meso crystallization of challenging targets like GPCRs [22] |

| High-Viscosity Carriers | Crystal suspension medium for injection | Reduces flow turbulence and crystal settling during serial data collection [22] |

| Cryoprotectants | Prevent ice formation during vitrification | Critical for maintaining crystal integrity during cryo-cooling procedures |

| LAMA Nozzles | Precise ligand application for time-resolved studies | Enables reaction initiation with picoliter droplets; adjustable deposition up to 3 nL/ms [23] |

| SPINE Standardized Sample Containers | Universal sample holder system | Ensures compatibility with automated sample changers and storage systems at synchrotrons [23] |

The selection and optimization of these reagents directly impact experimental success rates. For example, the development of lipidic mesophases as crystallization matrices has been instrumental for membrane protein structural biology, enabling the determination of groundbreaking structures like the β2-adrenergic receptor [22]. Similarly, specialized nozzles for the liquid application method for time-resolved applications (LAMA) permit in situ mixing with minimal substrate volumes while achieving reaction initiation times in the millisecond domain, which is crucial for capturing transient reaction intermediates [23].

Data Management and Processing Pipelines

The exponential growth in structural data generated by high-throughput crystallography has been supported by the development of sophisticated data management resources. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as the primary worldwide repository for biological macromolecular structure data, providing critical archival and distribution functions for the global research community [24]. Specialized databases complement the PDB for specific applications, including the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) for small molecules, the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) for inorganic compounds, and the Nucleic Acid Database (NDB) dedicated to nucleic acid structures [24].

These resources are interconnected through standardized data formats and access protocols, facilitating seamless data retrieval and integration. The Reciprocal Net represents a distributed database used by research crystallographers to store molecular structure information, with much of the data accessible to the public [24]. This ecosystem of data resources ensures that structural information generated through high-throughput methods is preserved, curated, and made available to support further scientific discovery.

Automated Data Processing

The volume of data produced by high-throughput crystallography, particularly serial methods, necessitates automated processing pipelines. These pipelines integrate multiple software components to handle data from raw diffraction images to refined structural models with minimal manual intervention. For serial crystallography approaches, specialized algorithms process thousands of diffraction patterns, identifying hit rates, indexing patterns, and merging partial datasets from multiple crystals into complete data sets [22].

Modern processing pipelines incorporate radiation damage assessment protocols that monitor metrics like diffraction resolution decay and specific structural signatures of damage during data collection [22]. This capability is particularly important for high-throughput operations where multiple samples may be screened sequentially, as it allows researchers to adjust collection strategies in real-time to optimize data quality. The integration of these automated systems with synchrotron beamline controls enables feedback loops where processing results can inform subsequent data collection parameters, creating an adaptive, intelligent experimental workflow.

High-throughput crystallography, empowered by synchrotron radiation, has fundamentally transformed structural biology, enabling researchers to address increasingly complex biological questions with unprecedented efficiency. The field continues to evolve through several key trends that will further streamline workflows and expand scientific capabilities. The ongoing development of time-resolved methodologies promises to provide deeper insights into dynamic biological processes, with devices like spitrobot-2 pushing the temporal resolution for cryo-trapping experiments to under 25 milliseconds [23]. This advancement expands the range of target systems that can be studied using cryo-trapping time-resolved crystallography [23].

The proliferation of serial data collection methods at synchrotron facilities represents another significant trend, making time-resolved studies more accessible to a broader research community [23]. As these methods become more robust and user-friendly, they enable more researchers to undertake ambitious structural studies of dynamic processes. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in various stages of the crystallographic pipeline, from crystal recognition to molecular replacement, promises to further accelerate structure determination and reduce manual intervention requirements.

In conclusion, high-throughput crystallography at synchrotron facilities has matured into a sophisticated, integrated pipeline that efficiently transforms protein crystals into biological insights. By combining advanced instrumentation, automated workflows, and specialized reagent systems, this approach has dramatically accelerated structural biology research, particularly for challenging targets like membrane proteins. As synchrotron technologies continue to advance and computational methods become increasingly powerful, high-throughput crystallography will remain a cornerstone technique for elucidating biological mechanisms and supporting structure-based drug design efforts.

Serial Synchrotron Crystallography (SSX) has emerged as a transformative methodology within structural biology, enabling high-resolution structure determination from microcrystals at physiological temperatures. By leveraging the intense, focused X-ray beams of modern synchrotron facilities, SSX facilitates time-resolved studies of enzymatic reactions and ligand binding processes. This technical guide details the core principles, methodologies, and applications of SSX, with a special emphasis on its capacity to produce "molecular movies" that capture protein dynamics in action, thereby playing a pivotal role in modern drug development and biomedical research [2] [25].

Synchrotron facilities are paramount for protein crystallography, providing the high-brilliance X-ray beams essential for probing macromolecular structures. The advent of fourth-generation synchrotrons, such as MAX IV, with their multi-bend achromat (MBA) storage ring designs, has significantly reduced beam emittance, resulting in unprecedented brightness and beam coherence [1]. This technological leap has been instrumental in the rise of SSX.

Traditional macromolecular crystallography often relied on large, single crystals flash-cooled to cryogenic temperatures. This approach can obscure functionally relevant conformational states and is not amenable to studying rapid, dynamic processes [26] [27]. SSX circumvents these limitations by collecting diffraction data from thousands of microcrystals in a serial fashion, with each crystal exposed to the X-ray beam only once. This "diffraction-before-destruction" approach, pioneered at X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) and now robustly implemented at synchrotrons, allows data collection at room temperature and enables time-resolved studies [1] [25]. Facilities like MicroMAX at MAX IV are dedicated to such serial and time-resolved experiments, showcasing the central role of synchrotron beamlines in advancing this field [1].

Technical Foundations of SSX

The power of SSX stems from the synergistic combination of microcrystals, advanced beamlines, and innovative sample delivery methods.

- The Microcrystal Advantage: Microcrystals (typically only a few micrometres in size) are not merely a fallback for samples that fail to produce larger crystals; they are often the preferred sample form. Their small size ensures rapid and uniform diffusion of substrates or ligands, which is crucial for synchronized reaction initiation in time-resolved studies [25]. Furthermore, their minimal dimensions mitigate X-ray radiation damage during the brief exposure, allowing data collection under near-physiological conditions [28].

- Synchrotron Beamline Capabilities: Modern beamlines like BioMAX and MicroMAX at MAX IV are engineered for SSX. They feature micro-focused beams (e.g., 20 × 5 µm²), fast-readout detectors, and high-precision goniometers capable of rapid raster scanning [1]. The high photon flux of these beamlines enables the collection of usable diffraction patterns from crystals once considered too small for structural analysis.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

A successful SSX experiment integrates several critical components, from sample preparation to data collection.

Sample Delivery Systems