Taming Complexity: A Practical Guide to RFE for Large-Scale Chemical Data

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful feature selection technique critical for analyzing the high-dimensional datasets prevalent in modern chemical and pharmaceutical research.

Taming Complexity: A Practical Guide to RFE for Large-Scale Chemical Data

Abstract

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful feature selection technique critical for analyzing the high-dimensional datasets prevalent in modern chemical and pharmaceutical research. This article provides a comprehensive guide for scientists and researchers on applying RFE to large chemical datasets, where computational complexity becomes a significant concern. We explore the foundational mechanics of RFE, detail its methodological application in domains like drug discovery and materials science, and address key troubleshooting strategies for managing computational cost and data imbalance. Furthermore, we review advanced RFE variants and validation frameworks, offering a comparative analysis to guide the selection of efficient and accurate feature selection pipelines for real-world chemical data challenges.

RFE and the Big Data Challenge in Chemical Sciences

The Critical Need for Feature Selection in Modern Chemical Datasets

In the fields of chemistry and materials science, the advent of high-throughput computational and experimental methods has led to an explosion in the dimensionality of datasets. Researchers now routinely face datasets with hundreds or even thousands of molecular descriptors, features, and properties. However, not all features contribute equally to predictive modeling tasks, and the inclusion of irrelevant or redundant features can severely diminish model performance, increase computational costs, and reduce interpretability. This challenge is particularly acute for chemical datasets, which are often characterized by their small sample sizes, high dimensionality, and inherent noise.

The "curse of dimensionality" is a significant concern when the number of features increases while the training sample size remains fixed, leading to deteriorated predictive power [1]. This technical support article explores how Feature Selection (FS) methods, particularly Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), address these challenges within chemical research. We frame this discussion within the context of a broader thesis on managing the computational complexity of RFE for large chemical datasets, providing practical guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

FAQs: Addressing Common Feature Selection Challenges in Chemical Data

How does feature selection specifically benefit machine learning on small chemical datasets?

Feature selection is particularly crucial for small chemical datasets, which are common in experimental studies due to constraints in data acquisition time, cost, and technical barriers [2]. When training datasets are limited and imbalanced, models become prone to overfitting and exhibit diminished generalization capabilities [2]. The "curse of dimensionality" (Hughes phenomenon) occurs when the number of features increases with a fixed training sample size, causing predictive power to deteriorate beyond a certain point of dimensionality [1]. By selecting only the most relevant features, researchers can create more robust models that maintain predictive accuracy even with limited data.

What makes Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) well-suited for chemical data analysis?

RFE is a powerful wrapper method that offers several advantages for chemical data analysis. It can handle high-dimensional datasets and identify the most important features while considering interactions between features, making it suitable for complex chemical datasets [3]. Unlike filter methods that evaluate features individually, RFE considers feature subsets using a learning algorithm, enabling it to capture complex relationships in molecular data [3]. The recursive nature of RFE allows it to effectively reduce dataset dimensionality while preserving the most informative features, which is essential for maintaining model interpretability in chemical applications.

What are the primary computational challenges when applying RFE to large chemical datasets?

The main computational challenge with RFE is its expense, as the iterative process of repeatedly fitting models and evaluating feature importance significantly increases computational costs [2]. For large chemical datasets with thousands of features and complex models, this process can become prohibitively slow. Additionally, RFE may not be the optimal approach for datasets with many highly correlated features, which are common in chemical descriptor spaces [3]. These challenges are particularly pronounced when working with complex molecular representations and high-dimensional feature spaces typical in modern chemical informatics.

How can researchers mitigate the computational complexity of RFE in chemical applications?

Several strategies can help mitigate RFE's computational demands. Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be applied before RFE to reduce the initial feature space [3]. For SVM-RFE specifically, alpha seeding approaches have been proposed to reduce computational complexity by approximating generalization errors [4]. Alternatively, researchers can employ filter methods as a preprocessing step to reduce the number of features before applying RFE, or use efficient sampling methods like Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) in property-designated chemical feature spaces to create well-distributed training sets [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Prohibitively Long Computation Time for RFE

Problem: RFE is taking too long to complete with your chemical dataset.

Solution:

- Reduce Feature Space Pre-Filtering: Apply a faster filter method (e.g., correlation-based feature selection) to reduce the number of features before running RFE [1].

- Adjust RFE Parameters: Increase the

stepparameter to eliminate multiple features per iteration rather than one at a time [3]. - Leverage Dimensionality Reduction: Apply PCA or other dimensionality reduction techniques before RFE [3].

- Use Efficient Implementations: Utilize optimized libraries like Scikit-learn's

RFEorRFECVwhich include computational optimizations [3].

Issue: Model Performance Decreases After Feature Elimination

Problem: Your model's predictive accuracy drops after applying RFE.

Solution:

- Cross-Validation: Use RFE with cross-validation (RFECV) to automatically determine the optimal number of features [3].

- Algorithm Selection: Ensure the estimator used in RFE matches your final model type (e.g., use SVR for regression problems).

- Feature Importance Re-evaluation: Validate feature importance rankings with alternative methods or domain knowledge.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Re-tune model hyperparameters after feature selection, as the optimal parameter space may change.

Issue: Handling Highly Correlated Molecular Descriptors

Problem: RFE struggles with chemically relevant but highly correlated features.

Solution:

- Correlation Analysis: Pre-filter features using pairwise correlation thresholds.

- Alternative Methods: Consider using regularization-based methods (L1 regularization) that naturally handle multicollinearity [3].

- Ensemble Approaches: Combine RFE with other feature selection methods to create a consensus feature set.

- Domain Knowledge Integration: Incorporate chemical knowledge to guide which correlated features to prioritize.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard RFE Implementation Protocol for Chemical Data

Objective: To identify the most predictive molecular features for a target chemical property using RFE.

Materials:

- Chemical dataset with annotated properties (e.g., adsorption energies, sublimation enthalpies)

- Computing environment with Python and Scikit-learn

- Molecular descriptors calculated using RDKit [2] or AlvaDesc [1]

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Scale and normalize the dataset to ensure features are comparable [3].

- Descriptor Calculation: Compute molecular descriptors using tools like RDKit or AlvaDesc [2] [1].

- Initial Model Setup: Select an appropriate estimator (e.g., SVM for classification, SVR for regression).

- RFE Configuration: Initialize RFE with desired parameters (

n_features_to_select,step). - Feature Elimination: Execute the RFE process, which will:

- Validation: Assess model performance on held-out test set using appropriate metrics.

Advanced Protocol: RFE with Cross-Validation for Small Chemical Datasets

Objective: To determine the optimal number of features while accounting for limited dataset sizes.

Procedure:

- Data Splitting: Partition data into training and test sets, preserving class distributions if possible.

- RFECV Setup: Use

RFECVinstead ofRFEwith appropriate cross-validation strategy (e.g., 5-fold CV). - Parameter Tuning: Optimize both the estimator parameters and feature selection simultaneously.

- Stability Assessment: Repeat the process with different random seeds to assess feature selection stability.

- Final Model Training: Train the final model using only the selected features on the entire training set.

Performance Data & Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Chemical Datasets

| Method | Dataset Size | Original Features | Selected Features | Model Performance | Computational Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFE | Boiling Point Data [2] | 12 | 2 | MSE: ~0.025 (Test) | Moderate |

| FPS-PDCFS [2] | Boiling Point Data | 12 | N/A | Enhanced predictive accuracy vs. random sampling | Lower than RFE |

| Practical Feature Filter [1] | Adsorption Energies | 12 | 2 | Accurate results maintained | Low |

| SVM-RFE with Model Selection [4] | Bioinformatics Datasets | Varies | Varies | Exceeds compared algorithms | High (reduced with alpha seeding) |

Table 2: Computational Complexity Comparison of Feature Selection Techniques

| Method | Computational Complexity | Suitable for Large Datasets | Handles Feature Interactions | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | Low | Yes | No | Initial feature screening, large-scale preprocessing |

| RFE | High | With limitations | Yes | Final feature selection, complex chemical relationships |

| FPS-PDCFS [2] | Moderate | Yes | Through space construction | Small chemical datasets, diversity preservation |

| Practical Feature Filter [1] | Low | Yes | Limited | Small datasets, limited computational resources |

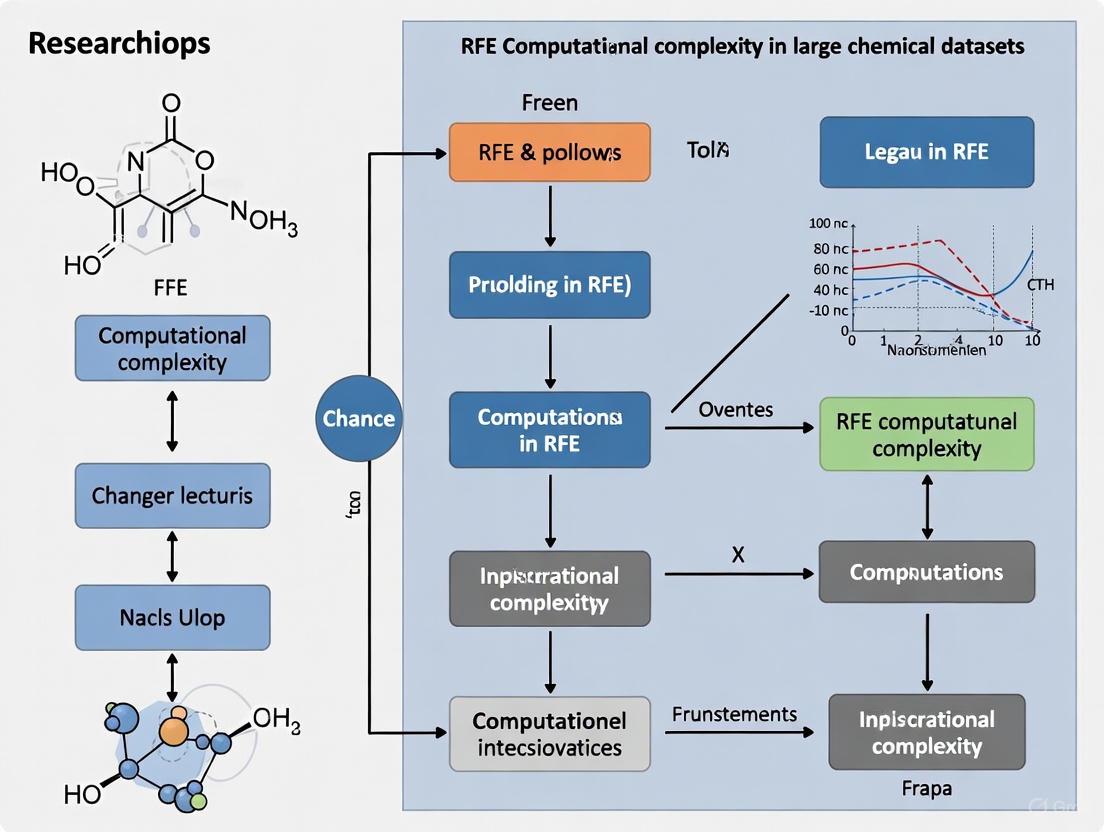

Workflow Visualization

RFE for Chemical Data Workflow

Computational Complexity Optimization Strategies

Table 3: Essential Tools for Feature Selection in Chemical Machine Learning

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Chemical Data |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn [3] | Python ML library providing RFE, RFECV implementations | General-purpose feature selection for chemical datasets |

| RDKit [2] | Cheminformatics software | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints |

| AlvaDesc [1] | Molecular descriptor calculation software | Generating comprehensive molecular feature sets |

| SVM/SVR [3] | Machine learning algorithm | Commonly used estimator for RFE in chemical applications |

| Farthest Point Sampling (FPS) [2] | Sampling method for high-dimensional spaces | Creating diverse training sets in chemical feature space |

| AutoML [1] | Automated machine learning | Efficient feature filter strategy for small datasets |

| PCA [3] | Dimensionality reduction technique | Preprocessing step to reduce feature space before RFE |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common RFE Challenges and Solutions

Q1: My RFE model is performing poorly on new chemical data despite high training accuracy. What could be wrong? A1: This is often a sign of selection bias or overfitting during the feature selection process itself. When the RFE procedure is performed on a single, static training set, it can overfit to the nuances of that specific data split. The solution is to use a robust resampling method [5].

- Solution: Encapsulate the entire RFE process within an outer layer of resampling, such as repeated cross-validation. This ensures that the feature selection is performed independently on each resampled training set, providing a more reliable estimate of model performance on unseen data and a probabilistic assessment of feature importance [5]. Tools like

RFECVin scikit-learn automate this process [3] [6].

Q2: The feature rankings from my RFE process are unstable with each run. How can I get consistent results? A2: Instability can arise from several factors, including the model used within RFE and high correlations between features.

- Solution 1: Recompute rankings. For models like linear models with highly collinear predictors, recomputing feature importance rankings at each iteration of the elimination process can slightly improve performance and stability [5].

- Solution 2: Use a robust base algorithm. The choice of estimator (e.g., Linear SVM, Decision Tree) heavily influences the rankings. Experiment with different, more stable algorithms. Furthermore, standardizing your data before applying RFE, especially with linear models, is crucial for obtaining meaningful importance scores [7] [6].

Q3: RFE is too slow on my large, high-dimensional chemical dataset. How can I improve its efficiency? A3: The computational cost of RFE is a known limitation, as it requires building multiple models [3] [7].

- Solution 1: Adjust the step size. Increase the

stepparameter to remove a larger percentage of features at each iteration, significantly reducing the number of model fits required [3]. - Solution 2: Pre-process with dimensionality reduction. Before applying RFE, use a fast dimensionality reduction technique like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the feature space, then run RFE on the principal components [3] [6].

- Solution 3: Leverage parallel processing. If using resampling with RFE (e.g.,

rfein thecaretpackage), the outer resampling loop can be parallelized to take advantage of multiple processors [5].

RFE Performance Metrics on a Synthetic Dataset

The following table summarizes the performance of an RFE model, using a Decision Tree classifier, on a synthetic binary classification dataset with 10 features (5 informative, 5 redundant). The evaluation uses repeated stratified k-fold cross-validation [8].

| Evaluation Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Dataset Samples | 1000 |

| Total Features | 10 |

| Features Selected by RFE | 5 |

| Mean Accuracy | 88.6% |

| Standard Deviation of Accuracy | ± 3.0% |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing RFE with Cross-Validation for Predictive Modeling

This protocol details the steps to evaluate a model with RFE for feature selection, ensuring a robust performance estimate.

1. Problem Definition and Dataset Creation:

- Define a synthetic classification problem using

make_classificationfromsklearn.datasets. - Configure the dataset with

n_samples=1000,n_features=10,n_informative=5, andn_redundant=5[8].

2. Algorithm and Pipeline Configuration:

- Create the RFE Object: Initialize the

RFEclass fromsklearn.feature_selection. Select an estimator that provides feature importance (e.g.,DecisionTreeClassifier) and set then_features_to_select=5[8]. - Create the Final Model: Instantiate the model to be used for final prediction (e.g., another

DecisionTreeClassifier). - Build the Pipeline: Create a

Pipelinefromsklearn.pipelineto chain the RFE feature selector ('s') and the final model ('m'). This prevents data leakage [8].

3. Model Evaluation with Resampling:

- Define Resampling Method: Use

RepeatedStratifiedKFoldfor robust evaluation, configured withn_splits=10,n_repeats=3, and a fixedrandom_state[8]. - Evaluate the Pipeline: Pass the entire pipeline, the dataset, and the resampling strategy to

cross_val_scoreto compute performance metrics (e.g., accuracy). This evaluates the entire process of feature selection and model training on resampled data [8].

4. Final Model Fitting and Prediction:

- Fit the Pipeline: Call

pipeline.fit(X, y)to fit the RFE and the final model on the entire dataset [8]. - Make Predictions: Use the fitted pipeline's

predict()function on new data to get predictions [8].

Workflow Visualization: The RFE Algorithm with Cross-Validation

The following diagram illustrates the recursive feature elimination process embedded within a cross-validation framework, which is a best practice for obtaining reliable feature subsets and performance estimates [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for an RFE Experiment

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and tools required to implement an RFE experiment successfully in a chemical research context.

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example in Python Ecosystem |

|---|---|---|

| Base Estimator | The core machine learning model used by RFE to rank features based on importance. | LinearSVC, DecisionTreeClassifier, RandomForestRegressor [3] [7]. |

| RFE Wrapper | The algorithm that orchestrates the iterative process of fitting, ranking, and feature elimination. | RFE or RFECV from sklearn.feature_selection [3] [8]. |

| Resampling Method | A technique to evaluate model performance and mitigate overfitting by creating multiple train/test splits. | RepeatedStratifiedKFold, K-Fold Cross-Validation [5] [8]. |

| Pipeline Utility | A tool to chain the RFE step and the final model training together, preventing data leakage. | Pipeline from sklearn.pipeline [8]. |

| Data Preprocessor | A scaler or normalizer to standardize features, which is critical for models sensitive to feature scales. | StandardScaler from sklearn.preprocessing. |

Note on Chemical Data: When working with large, imbalanced chemical datasets (common in drug discovery where active molecules are rare), consider applying techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) before RFE to balance class distribution and improve model sensitivity to minority classes [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary factors that cause RFE to become computationally expensive on large chemical datasets? The computational cost of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) scales with dataset size due to three primary factors: the iterative model retraining process, the high dimensionality (number of features), and the sample size. RFE is a greedy wrapper method that repeatedly constructs models, each time removing the least important features [10] [11]. With large-scale data, such as the high-dimensional features extracted from chemical structures or medical sensor images [12], each iteration involves significant computation. Furthermore, complex models like Random Forest or XGBoost, while accurate, further increase runtime due to their inherent complexity [10].

Q2: My dataset has over 100,000 features. Will RFE be feasible, and what are my options? Handling over 100,000 features is challenging but feasible with strategic choices. Standard RFE wrapped with tree-based models may retain strong predictive performance but will likely incur high computational costs and retain large feature sets [10]. For such high-dimensional scenarios, consider:

- Enhanced RFE Variants: Algorithms that achieve substantial feature reduction with minimal accuracy loss, offering a favorable balance [10].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine RFE with other dimensionality reduction techniques like Dynamic Principal Component Analysis (DPCA) as a preprocessing step to first reduce the feature space [12].

- Linear Models: Using a linear model like Linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) for the ranking step can be significantly faster than tree-based models, though it may capture fewer complex interactions.

Q3: How does the choice of the underlying estimator (e.g., SVM vs. Random Forest) impact RFE's computational complexity? The choice of estimator is a major determinant of complexity. Linear models, such as Linear SVM, generally have a faster training time per iteration compared to ensemble methods like Random Forest or XGBoost [10]. Tree-based models capture complex, non-linear feature interactions effectively, which can lead to slightly better predictive performance, but this comes at the cost of significantly higher computational resources and longer runtimes [10]. The trade-off is between predictive power and computational efficiency.

Q4: What are the trade-offs between accuracy, interpretability, and computational cost across different RFE variants? Our evaluation shows clear trade-offs [10]:

- Tree-based RFE (e.g., RF-RFE, XGBoost-RFE): High predictive accuracy, good at capturing complex feature interactions, but high computational cost and less aggressive feature reduction.

- Linear Model-based RFE (e.g., SVM-RFE): Lower computational cost, high interpretability, but may miss complex non-linear relationships.

- Enhanced RFE: Offers a balanced approach, achieving substantial feature reduction with only a marginal loss in accuracy, thus favoring interpretability and efficiency.

Q5: For a real-time chemical process monitoring application, how can I make RFE more efficient? For real-time applications like silicon content prediction in blast furnaces [13] or real-time anomaly detection in medical sensors [12], static RFE is unsuitable. Implement dynamic feature selection algorithms. For example, the BOSVRRFE algorithm integrates Bayesian online sequential updating with SVR-RFE, allowing feature importance to be adjusted in real-time without full model retraining [13]. This leverages the recursive optimization of RFE while adding a lightweight adaptation mechanism for changing process conditions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Extremely Long Training Times on High-Dimensional Data

Symptoms: The RFE process is taking hours or days to complete. Each model training iteration is slow. The system runs out of memory.

Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pre-filter Features | Use a fast filter method (e.g., correlation, mutual information) for preliminary feature selection to reduce the initial feature set fed into RFE [9]. |

| 2 | Optimize Estimator | Use a computationally efficient base estimator. For the first pass, use a Linear SVM or Logistic Regression model instead of Random Forest or XGBoost [10] [4]. |

| 3 | Adjust RFE Parameters | Increase the step parameter to remove a larger percentage of features per iteration, thus reducing the total number of iterations required. |

| 4 | Leverage Hardware | Utilize cloud computing or high-performance computing (HPC) clusters with parallel processing capabilities to distribute the computational load. |

Issue 2: Unstable Feature Selection Results

Symptoms: The final set of selected features changes significantly when the dataset is slightly perturbed or different data splits are used.

Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ensure Data Quality | Address missing values and normalize the data. Inconsistent data preprocessing is a common source of instability. |

| 2 | Use Stable Base Models | Models like Random Forest, which are inherently more robust to data variations, can produce more stable feature rankings than less robust models [10]. |

| 3 | Incorporate Cross-Validation | Perform feature ranking with RFE across multiple cross-validation folds. Only select features that are consistently ranked as important across most folds [11]. |

| 4 | Hybridize with Embedded Methods | Combine RFE with stable embedded feature importance measures from tree-based models to improve selection consistency [10]. |

Issue 3: Poor Model Performance After Feature Elimination

Symptoms: The model's predictive accuracy (e.g., RMSE, F1-score) drops significantly after applying RFE.

Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Review Stopping Criterion | The preset number of features to select might be too low. Use a performance-based stopping criterion (e.g., stop when performance drops below a threshold) instead of a fixed number [10] [11]. |

| 2 | Check for Feature Interactions | The base estimator might be unable to capture critical non-linear feature interactions. Switch to a non-linear estimator like Random Forest or XGBoost [10]. |

| 3 | Validate Data Leakage | Ensure that the feature selection process is performed only on the training set within each cross-validation fold to prevent optimistic bias. |

| 4 | Re-evaluate Data Balance | For classification, if data is imbalanced, use techniques like SMOTE before RFE to ensure the minority class is represented [9]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking RFE Variants for Predictive Performance

This protocol is derived from a study benchmarking RFE variants across education and healthcare domains [10].

1. Objective: To empirically evaluate the performance, stability, and computational efficiency of different RFE variants.

2. Materials and Datasets:

- Dataset 1 (Regression): Large-scale educational dataset for predicting mathematics achievement.

- Dataset 2 (Classification): Clinical dataset on chronic heart failure.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Algorithm Selection: Select representative RFE variants:

- Standard RFE with a linear model.

- RF-RFE (Random Forest).

- XGBoost-RFE.

- Enhanced RFE.

- RFE with local search.

- Step 2 - Evaluation Setup: For each algorithm and dataset, run the RFE process, tracking:

- Predictive Accuracy: Using metrics like Accuracy or RMSE.

- Number of Selected Features.

- Runtime.

- Feature Selection Stability.

- Step 3 - Analysis: Compare the trade-offs between accuracy, feature set size, and computational cost across all variants.

4. Key Results Summary (Illustrative): The following table summarizes hypothetical findings based on the described study [10]:

| RFE Variant | Predictive Accuracy | Number of Features Selected | Computational Cost (Runtime) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF-RFE | High | Large | Very High |

| XGBoost-RFE | High | Large | Very High |

| SVM-RFE | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Enhanced RFE | Slightly below High | Small | Low |

Protocol 2: Dynamic Feature Selection for Industrial Process Prediction

This protocol is based on the BOSVRRFE algorithm for silicon content prediction in blast furnaces [13].

1. Objective: To implement a dynamic feature selection algorithm that adapts to changing industrial operating conditions in real-time.

2. Materials and Datasets:

- Dataset: Large-scale, real-time sensor data from a blast furnace ironmaking process, including burden composition, gas flow, and temperature readings [13].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Feature Categorization: Group initial features based on process zones (e.g., charging zone, combustion zone) for interpretability [13].

- Step 2 - Algorithm Implementation:

- Integrate Bayesian online sequential updating to dynamically track changes in feature relevance.

- Employ Support Vector Regression-based Recursive Feature Elimination (SVR-RFE) for recursive feature ranking.

- Develop a lightweight real-time adaptation mechanism that adjusts feature importance without full model retraining.

- Step 3 - Validation: Compare the prediction accuracy and stability of BOSVRRFE against traditional static feature selection methods under dynamic operating conditions.

RFE Computational Bottleneck Workflow

Dynamic vs. Static Feature Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in RFE Experiment |

|---|---|

| Scikit-learn Library | Provides the core RFECV implementation and base estimators (SVM, Random Forests) for standard RFE workflows. |

| XGBoost | A highly optimized gradient boosting library; used as the base estimator in XGBoost-RFE for capturing complex, non-linear relationships in data [10]. |

| Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) | A resampling technique used prior to RFE on imbalanced chemical datasets (e.g., active vs. inactive compounds) to prevent bias towards the majority class [9]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A dimensionality reduction technique often used in hybrid approaches to pre-filter features and reduce the input space for RFE, mitigating initial computational load [12]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | The core wrapper algorithm itself, used to recursively prune features and identify an optimal subset based on model performance [10] [11]. |

| Bayesian Online Sequential Algorithm | A key component in dynamic RFE variants like BOSVRRFE, enabling real-time updating of feature importance without complete retraining [13]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What is the OMol25 dataset and what makes its scale and dimensionality challenging?

The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset is a large-scale molecular dataset comprising over 100 million density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, representing billions of CPU core-hours of compute [14]. The dataset uniquely blends elemental, chemical, and structural diversity, featuring 83 elements, a wide range of intra- and intermolecular interactions, explicit solvation, variable charge/spin, conformers, and reactive structures [14]. It contains approximately 83 million unique molecular systems covering small molecules, biomolecules, metal complexes, and electrolytes, with systems of up to 350 atoms [14]. The scale presents challenges in data storage, transfer, and computational resources for processing and model training.

Q2: My feature matrix for OMol25 is too large for memory. What are the primary strategies for dimensionality reduction?

For high-dimensional chemical data, two proven strategies are:

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): A systematic method for selecting molecular descriptors and minimizing multicollinearity. RFE ranks features by their importance and recursively removes the least important ones, helping to discover new relationships between global properties and molecular descriptors [15] [16]. This method is effective for creating interpretable machine learning models without sacrificing accuracy.

Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) for Visualization: Tools like tmap use MinHash and LSH Forest to enable fast nearest-neighbor searches and visualization of very large, high-dimensional data sets (e.g., millions of data points) by creating interpretable tree-based layouts [17]. This is crucial for visualizing datasets with dimensions like the ChEMBL database (1,159,881 x 232) or larger [17].

Q3: How does RFE improve model performance and interpretability on a dataset like OMol25?

RFE improves model performance and interpretability by:

- Reducing Overfitting: By eliminating redundant and noisy features, RFE helps models generalize better to new data.

- Enhancing Discoveries: The process uncovers key molecular descriptors strongly correlated with target properties, offering new scientific insights [16].

- Managing Computational Cost: A reduced feature set decreases the computational load for algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) [15].

For example, in protein structural class prediction, using SVM-RFE on integrated features from PSSM, PROFEAT, and Gene Ontology led to significantly higher accuracies (84.61% to 99.79%) on benchmark datasets, especially for low-similarity sequences [15].

Q4: What are the computational bottlenecks when applying RFE to petabyte-scale chemical data?

The primary bottlenecks are:

- Memory Consumption: Storing and processing the entire feature matrix for large datasets can exceed available RAM.

- Processing Time: The recursive process of training a model, ranking features, and removing the weakest can be time-consuming on massive data.

- Feature Ranking Calculation: Efficiently computing the feature importance ranking at each iteration is critical.

Solution: Implement incremental learning and leverage high-performance computing (HPC) resources. The OMol25 data is made available via the Eagle cluster at the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility (ALCF) through a high-performance Globus endpoint, which is designed to handle such large-scale data [18].

Q5: Are there pre-trained models available for the OMol25 dataset to bypass full-scale training?

Yes, Meta's FAIR team has released several pre-trained models, which can be fine-tuned for specific tasks, saving immense computational resources.

- eSEN models: Small, medium, and large direct-force prediction models, plus a small conservative-force model are available. The conservative-force model generally outperforms direct-force counterparts [19].

- Universal Model for Atoms (UMA): A unified model architecture trained on OMol25 and other datasets using a novel Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) approach, enabling knowledge transfer across datasets and superior performance [19].

These models achieve "essentially perfect performance" on molecular energy benchmarks and can be accessed via platforms like Hugging Face or run on services like Rowan [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Feature Selection using RFE for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol is adapted from methods used for predicting protein structural classes and physiochemical properties of biofuels [15] [16].

Objective: To reduce the dimensionality of a high-dimensional feature set derived from molecular structures and improve the performance and interpretability of a property prediction model.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Feature Extraction and Integration:

- Generate or gather diverse feature representations for each molecule in your dataset. For a comprehensive approach, integrate features from multiple sources:

- Evolutionary Information: Create a Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) using PSI-BLAST against a non-redundant database [15].

- Structural & Physicochemical Properties: Use a tool like PROFEAT to compute descriptors (e.g., dipeptide composition, sequence-order-coupling number), generating a ~1080-dimensional vector [15].

- Functional Annotations: Map Gene Ontology (GO) terms to each protein, creating a binary feature vector indicating the presence or absence of each relevant GO term [15].

- Concatenate these diverse feature vectors into a single, high-dimensional vector for each molecule.

- Generate or gather diverse feature representations for each molecule in your dataset. For a comprehensive approach, integrate features from multiple sources:

Build Initial Feature Matrix:

- Construct a matrix where rows represent molecular samples and columns represent all integrated features.

Initialize SVM and RFE:

- Select a linear SVM as the core classifier. Choose a performance metric (e.g., accuracy, mean absolute error).

- Specify the desired number of features to select or the removal rate (e.g., remove one feature per step).

Recursive Feature Elimination Loop:

- Train SVM Model: Train the linear SVM on the current feature set.

- Rank Features: Use the model's weights (e.g., the square of the coefficients) to rank features by their importance [15].

- Remove Lowest-Ranked Feature: Prune the feature with the smallest ranking score from the dataset.

- Iterate: Repeat the train-rank-remove cycle until the predefined number of features remains.

Final Model Training and Validation:

- Train your final predictive model (e.g., SVM) using the optimal subset of features identified by RFE.

- Validate model performance using rigorous cross-validation (e.g., jackknife tests) on held-out test sets [15].

Protocol 2: Visualizing High-Dimensional Chemical Space with TMAP

Objective: To create an intuitive, tree-based visualization of a large molecular dataset (e.g., a subset of OMol25) to explore chemical space and identify clusters or patterns.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Data Preparation:

- Load your molecular dataset (e.g., in SMILES or SDF format).

- Compute molecular descriptors or fingerprints (e.g., MAP4, ECFP) for each molecule. This creates the initial high-dimensional representation.

Minhash Encoding:

Indexing and k-NN Graph Generation:

Tree-Based Layout:

- Use TMAP's layout algorithm (e.g.,

tmap.layout) to arrange the k-NN graph into a visual tree structure, specifically a Minimum Spanning Tree (MST). This step simplifies the complex graph into a more interpretable hierarchy [17].

- Use TMAP's layout algorithm (e.g.,

Visualization:

- For large datasets, use the Faerun library to create an interactive web-based visualization. This can handle millions of data points and allows for coloring by properties, adding structure drawings, and interactive exploration [17].

Table 1: Scale and Diversity of the OMol25 Dataset

| Metric | Value | Significance / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Total DFT Calculations [14] | > 100 Million | Represents billions of CPU core-hours |

| Unique Molecular Systems [14] | ~83 Million | Vast coverage of chemical space |

| Number of Elements [14] | 83 | Extensive elemental diversity beyond common organic elements |

| Maximum System Size [14] | 350 Atoms | Enables study of large biomolecules and complexes |

| Data Volume (Raw Outputs) [18] | ~500 TB | Unprecedented scale for public molecular data |

| Level of Theory [14] [19] | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD | High-accuracy DFT functional and basis set |

Table 2: Performance of Predictive Models Trained on OMol25

| Model | Architecture | Key Feature | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| eSEN (Small, Cons.) [19] | Equivariant Transformer | Conservative force prediction | Outperforms direct-force models; suitable for MD |

| UMA [19] | Universal Model for Atoms | Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) | Knowledge transfer across datasets; state-of-the-art accuracy |

| Feature Selection Model [16] | TPOT + Selected Features | Systematic descriptor selection | MAPE: 3.3% - 10.5% for various molecular properties |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Handling OMol25-Scale Data

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset [14] [19] | Training data for ML models | Provides high-quality, diverse molecular data with quantum chemical properties |

| eSEN & UMA Models [19] | Pre-trained Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Fast, accurate energy and force predictions; transfer learning |

| SVM-RFE [15] [16] | Feature selection algorithm | Identifies most relevant molecular descriptors; reduces dimensionality |

| TMAP [17] | High-dimensional data visualization | Creates tree-based maps of chemical space for millions of molecules |

| PROFEAT [15] | Protein feature computation | Calculates structural and physicochemical descriptors from sequence |

| LSH Forest [17] | Fast nearest-neighbor search | Enables efficient similarity search and graph creation in large datasets |

| Argonne ALCF / Globus [18] | High-performance data transfer | Accessing and transferring the massive (~500 TB) OMol25 dataset |

Implementing RFE in Your Chemical Data Workflow: From Theory to Practice

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Feature Selection. This resource is designed for researchers and scientists working with large chemical datasets, where the high-dimensional nature of data—from molecular descriptors to protein embeddings—poses significant challenges. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful wrapper-style feature selection method, but its performance and computational cost are highly dependent on the machine learning model paired with it. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you optimize RFE for your research, with a specific focus on managing computational complexity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving High Computational Time in RFE

Problem: The RFE process is taking an impractically long time to complete on your large chemical dataset.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Using a computationally intensive model | Check if you are using a model like SVM with a non-linear kernel or a large tree-based ensemble. | Switch to a linear model: Use Linear SVM or Logistic Regression for the ranking process [10] [3]. Use the step parameter: Increase the step parameter to eliminate a percentage of features per iteration instead of one, reducing the number of model retrainings [3]. |

| Too many features in the initial set | Review the dimensionality of your starting feature set. | Pre-filter features: Use a fast filter method (e.g., ANOVA F-test) to remove obviously irrelevant features before applying RFE [20]. |

| Dataset with a massive number of samples | Check the number of instances in your dataset. | Leverage embedded methods: For tree-based models like Random Forest or XGBoost, use their built-in feature importance attributes directly instead of wrapping them in the full RFE process, which can be more efficient [10] [21]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Model Performance After RFE

Problem: After performing RFE, your final model's predictive performance has dropped significantly.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly aggressive feature elimination | Check the final number of features selected. Is it too small to capture the underlying signal? | Use cross-validation: Employ RFECV (RFE with cross-validation) to automatically find the optimal number of features [3]. Adjust n_features_to_select: Manually increase the number of features to retain and re-evaluate performance [3]. |

| Model mismatch for the data | Consider if the model used for RFE is suitable for your data's characteristics. | Match model to data: For complex, non-linear relationships in chemical data, tree-based models like Random Forest may identify a more robust feature subset than linear models [10] [21]. Validate on a holdout set: Always evaluate the performance of the feature-selected model on a completely unseen test set to ensure generalization [3]. |

| Presence of highly correlated features | Check for multicollinearity in your dataset. | RFE is generally robust, but if performance is poor, consider combining RFE with methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to handle multicollinearity [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does the choice of model impact the RFE process and results?

The model you choose for RFE is critical because it determines how "feature importance" is calculated, which in turn drives the elimination process. Different models have different strengths and computational profiles [10] [3]:

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Using a linear SVM is a classic choice for RFE. It provides a clear weight for each feature, is efficient, and works well for many high-dimensional problems [22] [3].

- Tree-Based Algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost): These models can capture complex, non-linear relationships and interactions between features, which can lead to a more robust feature subset [10] [21]. However, they are often more computationally intensive than linear models [10].

- Linear Models (e.g., Logistic Regression, Linear Regression): These are computationally efficient and provide a strong baseline. They are a good choice when computational cost is a primary concern [10].

When should I use a tree-based model over an SVM with RFE for chemical data?

Consider a tree-based model like Random Forest or XGBoost with RFE when:

- Your dataset involves complex, non-linear relationships between molecular features and the target property [10] [21].

- Predictive performance is the highest priority and you can accommodate the higher computational cost [10].

- You require robust performance without heavy preprocessing, as tree-based models are less sensitive to the scale of the features.

Choose an SVM with RFE when:

- You are working with very high-dimensional data (e.g., thousands of features) and need a computationally efficient ranking [10] [3].

- The relationships in your data are suspected to be approximately linear.

What are the best practices for implementing RFE on large chemical datasets?

To manage computational complexity and ensure success with large datasets, follow these protocols:

- Preprocessing is Key: Always scale your data (e.g., StandardScaler) before using SVM-based RFE, as SVMs are sensitive to feature scales. Tree-based models do not require this step [3].

- Leverage Hybrid Approaches: For the largest datasets, a hybrid feature selection method is highly recommended. First, use a fast filter method (like ANOVA F-test) to reduce the feature space to a manageable size (e.g., a few hundred). Then, apply RFE to this pre-filtered set for a more refined selection [20].

- Optimize the

stepParameter: Instead of the defaultstep=1(removing one feature per iteration), setstepto a higher integer or a percentage of features to remove (e.g.,step=0.1to remove 10% of features per iteration). This dramatically reduces the number of model retraining cycles [3]. - Use Cross-Validation with Care: While

RFECVfinds the optimal feature count, it multiplies the computation time. For a very large initial analysis, you might first run a standard RFE with a largestepto narrow the feature range, then useRFECVfor fine-tuning.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: A Standard RFE Workflow for Model Comparison

This protocol outlines a robust methodology to benchmark different ML models wrapped with RFE, as referenced in empirical evaluations [10].

Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the performance and computational efficiency of SVM, Random Forest, and Linear Regression when used with RFE on a single dataset.

Workflow:

Materials and Reagents (Computational):

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Dataset (e.g., WDCM dataset) | Provides the high-dimensional chemical/biological data for the benchmarking task [10]. |

Scikit-learn's RFE & RFECV |

The core library implementations for performing Recursive Feature Elimination [3]. |

| SVM, Random Forest, Linear Regression | The candidate machine learning models to be wrapped by RFE for comparison [10]. |

| Cross-Validation Folds | A resampling procedure used to reliably evaluate model performance and tune hyperparameters [3]. |

Protocol 2: A Hybrid Feature Selection Workflow for Large-Scale Data

This protocol is designed for enterprise-scale chemical datasets where computational efficiency is paramount, drawing from recent research on scalable feature selection [20].

Objective: To drastically reduce the computational time and resources required for feature selection on a very large, high-dimensional dataset without significantly compromising model performance.

Workflow:

Key Quantitative Findings from Benchmark Studies

Table: Benchmarking RFE Model Pairings (Based on [10])

| Model Used with RFE | Predictive Accuracy | Feature Set Size | Computational Cost | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Strong | Tends to retain larger subsets | High | Complex, non-linear data where accuracy is critical |

| Enhanced RFE | Strong with marginal loss | Achieves substantial reduction | Moderate | An excellent balance of efficiency and performance |

| Linear SVM | Good | Reduces to smaller subsets | Lower | High-dimensional data where speed is a priority |

Table: Performance of Hybrid Feature Selection (Based on [20])

| Metric | Standard PSO (Alone) | FeatureCuts + PSO (Hybrid) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Reduction | Baseline | +25 percentage points | Significant |

| Computation Time | Baseline | 66% less | Drastic |

| Model Performance | Maintained | Maintained | Preserved |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for RFE Experiments

| Item | Specification / Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn | A core Python ML library providing RFE and RFECV classes, plus all standard ML models. |

The primary toolkit for implementing the RFE workflows and models described in these guides [3]. |

| ANOVA F-test | A filter-based statistical test used to rank features based on their relationship with the target variable. | Used in the first stage of the hybrid workflow to quickly reduce the feature search space [20]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | An evolutionary algorithm that searches for an optimal feature subset by simulating social behavior. | Used as a powerful wrapper method in the final stage of the hybrid workflow for refined selection [20]. |

| Dragonfly Algorithm | A nature-inspired optimization algorithm used for hyperparameter tuning. | Can be used to optimize the parameters of the final ML model after feature selection is complete [23]. |

This guide provides technical support for researchers implementing Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) on large chemical datasets. RFE is a wrapper-style feature selection algorithm that recursively removes the least important features and rebuilds the model, ideal for high-dimensional cheminformatics data where identifying the most relevant molecular descriptors is critical [8] [3]. The computational complexity of RFE becomes a significant consideration when working with the massive feature spaces common in computational chemistry, such as those found in the Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset with its 100+ million molecular snapshots [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use RFE for my cheminformatics dataset instead of other feature selection methods?

RFE offers specific advantages for cheminformatics tasks. Unlike filter methods that score features individually, RFE considers feature interactions by recursively retraining a model, which is crucial for capturing complex relationships in chemical data [3]. It's model-agnostic and can handle high-dimensional datasets effectively, identifying the most informative molecular descriptors or fingerprints while reducing overfitting and improving model interpretability [25] [3].

Q2: How do I choose between RFE and RFECV for my project?

The choice depends on whether you know the optimal number of features to select and your computational constraints. Use standard RFE when you have a predefined number of features to select, which is useful when prior domain knowledge exists or for consistency across comparable datasets [26]. Choose RFECV (Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation) when you need to automatically determine the optimal number of features, as it identifies the feature subset that maximizes cross-validation performance [27] [25].

Q3: What are the most common errors when implementing RFE with large chemical datasets and how can I avoid them?

Common issues include memory errors during computation, inappropriate feature scaling, and data leakage. For large datasets, consider using the step parameter to remove multiple features at once, reducing iterations [26] [25]. Always scale features before applying RFE with distance-based algorithms like SVM, and use pipelines to prevent data leakage during cross-validation [25]. For extremely large datasets like OMol25, start with subsetted data to establish parameters before scaling up [24].

Q4: My RFE process is taking too long. How can I improve its computational efficiency?

Several strategies can improve runtime: (1) Increase the step parameter to remove more features per iteration [26]; (2) Use a faster estimator for the feature elimination process (e.g., Linear SVM instead of Random Forest); (3) For tree-based models, utilize the n_jobs parameter for parallel processing [27]; (4) Consider using feature pre-selection with a faster filter method before applying RFE; (5) For the largest datasets like those in cheminformatics, leverage specialized high-performance computing resources similar to those used for the OMol25 dataset, which required billions of CPU hours [24].

Q5: Different algorithms select different features. How do I know which result to trust?

This is expected behavior since different algorithms calculate importance differently [25]. Validate the selected features by: (1) Comparing model performance using a holdout test set; (2) Using domain knowledge to assess if selected features align with chemical intuition; (3) Testing stability through multiple runs with different random seeds; (4) Considering ensemble approaches that combine results from multiple algorithms. The stability of feature selection can be as important as pure accuracy in scientific contexts [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Memory Errors with Large Feature Sets

Symptoms: Python kernel crashes or MemoryError exceptions during RFE fitting.

Solution:

- Reduce feature space first: Apply variance threshold or correlation filter before RFE

- Adjust RFE parameters: Set a larger

stepvalue (e.g., 5-10% of features per iteration) - Use efficient data types: Convert data to float32 where precision permits

- Batch processing: For extremely large datasets, implement custom batched RFE

Example code for memory-efficient RFE:

Issue 2: Inconsistent Feature Selection Results

Symptoms: Different features selected when running RFE multiple times with same parameters.

Solution:

- Set random seeds: Ensure reproducibility by setting random_state in estimators

- Check data stability: Ensure input data isn't changing between runs

- Increase stability: Use RFECV or run multiple RFE iterations and select frequently chosen features

- Algorithm-specific fixes: For Random Forest, increase nestimators and set maxfeatures

Diagnostic workflow:

- Verify all random states are set in the estimator and RFE

- Check for data shuffling without fixed random state

- Run RFE multiple times and measure selection consistency

- Consider using more stable estimators for feature ranking

Issue 3: Poor Model Performance After Feature Selection

Symptoms: Selected features yield worse performance than using all features.

Solution:

- Review target feature count: The automatically selected number might be suboptimal

- Try different algorithms: Some algorithms work better with certain data types

- Check feature scaling: Many algorithms require scaled features for proper importance calculation

- Validate preprocessing: Ensure no data leakage during scaling or imputation

Performance optimization approach:

- Use RFECV to find optimal feature count rather than guessing

- Compare multiple estimator types (SVM, Random Forest, etc.)

- Ensure proper train-test separation before any preprocessing

- Validate with domain knowledge to ensure selected features are chemically plausible

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard RFE Implementation Protocol for Cheminformatics

Materials and Setup:

- Python 3.7+ with scikit-learn 1.0+

- Chemical dataset (e.g., OMol25 subset [24])

- Molecular descriptors or fingerprints as features

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Load chemical structures and target properties

- Calculate molecular descriptors/fingerprints (≥1000 features)

- Split data into training (80%) and test sets (20%)

- Scale features using StandardScaler

RFE Configuration:

- Select estimator based on data characteristics

- Define nfeaturesto_select or use RFECV for automatic determination

- Set step parameter based on computational resources (start with 1-5% of features)

Feature Selection Execution:

- Initialize RFE with chosen parameters

- Fit RFE on training data only

- Extract selected features and rankings

Validation:

- Train final model on selected features

- Evaluate performance on held-out test set

- Compare with baseline (all features) model

Example Implementation:

Advanced Protocol: Nested Cross-Validation with RFECV

For robust performance estimation with limited data:

- Outer loop: 5-fold cross-validation for performance estimation

- Inner loop: 3-fold cross-validation within each training fold for feature selection via RFECV

- Final evaluation: Average performance across outer test folds

Table 1: RFE Algorithm Comparison for High-Dimensional Data

| Algorithm | Optimal Use Case | Computational Complexity | Key Parameters | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard RFE | Known target feature count | O(niterations × modelfit_time) | n_features_to_select, step |

Simple, fast when feature count known [26] |

| RFECV | Unknown optimal feature count | O(niterations × modelfittime × cvfolds) | min_features_to_select, cv, scoring |

Automatically finds optimal feature count [27] |

| SVM-RFE | Linear datasets with many features | High for non-linear kernels | kernel, C |

Effective for high-dimensional data [28] |

| Tree-based RFE | Non-linear relationships | Medium to high | n_estimators, max_depth |

Handles complex interactions [29] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of RFE Variants on Benchmark Datasets

| RFE Variant | Average Accuracy (%) | Feature Reduction (%) | Runtime (relative units) | Stability (score 1-10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFECV with Linear SVM | 88.6 [8] | 50-90 | 1.0 | 8 |

| RFECV with Random Forest | 89.2 [10] | 30-70 | 3.5 | 7 |

| Enhanced RFE | 87.8 [10] | 70-95 | 0.7 | 9 |

| SVM-RFE | 92.3 [28] | 60-85 | 2.1 | 8 |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for RFE in Cheminformatics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scikit-learn RFE/RFECV | Core feature selection implementation | Use RFECV for automatic feature count optimization [26] [27] |

| OMol25 Dataset | Large-scale chemical structures with DFT properties | Contains 100M+ molecular snapshots for training robust models [24] |

| StandardScaler | Feature standardization | Critical for models sensitive to feature scales (SVM, neural networks) [25] |

| Pipeline Class | Prevents data leakage | Ensures scaling and RFE applied correctly during cross-validation [8] |

| Random Forest/SVM | Base estimators for RFE | Provide feature importance metrics; choose based on data characteristics [25] [28] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Chemical feature representation | RDKit or Mordred descriptors capture structural properties |

| Cross-Validation | Performance estimation | 5-10 folds recommended for reliable performance estimates [27] |

Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a powerful feature selection technique that iteratively constructs a model, identifies the least important features, and removes them until the optimal subset of features remains. In research involving large chemical datasets, RFE is critical for managing computational complexity by reducing dimensionality, improving model interpretability, and enhancing predictive accuracy by eliminating redundant or irrelevant variables. This guide provides practical solutions for researchers applying RFE to complex chemical data across various scientific domains.

Practical Implementation of RFE

RFE Workflow and Methodology

The standard RFE workflow involves a sequential process of model training, feature ranking, and elimination. The following diagram illustrates this iterative cycle:

Detailed Experimental Protocol for RFE:

Initial Model Training: Begin by training a baseline model (typically Random Forest or similar ensemble method) using the entire feature set [30] [21].

Feature Importance Ranking: Calculate feature importance scores. For Random Forest, this is commonly based on metrics like Mean Decrease in Accuracy (MDA) or Gini importance [30].

Iterative Elimination: Remove the bottom 10-20% of features or a single least important feature in each iteration. The elimination step size can be adjusted based on dataset size and computational resources.

Performance Evaluation: At each iteration, evaluate model performance using cross-validation to ensure robustness. Track metrics such as accuracy, precision, and recall.

Termination Condition: Continue the process until a predefined number of features remains, or until model performance begins to significantly degrade [21].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential computational tools and data resources for implementing RFE in chemical research:

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Random Forest Classifier | Core ML model for RFE; provides robust feature importance metrics [30] [21]. |

| OMol25 Dataset | Training data for MLIPs; enables large-scale chemical simulations with DFT-level accuracy [24]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Model optimization algorithm that can be combined with RFE to enhance predictive performance [31]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Post-hoc explanation framework for interpreting feature importance and model predictions [31]. |

| QuEChERS-HPLC-MS/MS | Analytical method for pesticide and metabolite monitoring; generates complex data for RFE processing [32]. |

RFE Application Case Studies & Data

Case Study 1: Nanomaterial Grouping and Toxicity Prediction

Objective: Identify the most predictive physico-chemical properties for nanomaterial (NM) toxicity to support grouping and reduce safety testing [30].

Methodology:

- Dataset: Eleven well-characterized nanomaterials with extensive physico-chemical properties [30].

- Model: Random Forest combined with RFE.

- Comparison: Performance was benchmarked against unsupervised methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [30].

Results Summary:

| Method | Balanced Accuracy | Key Predictive Features Identified |

|---|---|---|

| PCA + k-Nearest Neighbors | Lower than supervised methods | Not directly focused on correlation with activity |

| Random Forest (Full Feature Set) | Less than RFE-enabled model | Multiple features, including uninformative ones |

| Random Forest + RFE | 0.82 | Zeta potential, Redox potential, Dissolution rate |

Conclusion: RFE significantly enhanced model performance by identifying a minimal set of three highly predictive properties, demonstrating its power for NM grouping and risk assessment [30].

Case Study 2: Agrochemical Health Risk Assessment

Objective: Develop a precise predictive model for assessing health risks from synthetic agrochemicals using large-scale environmental and health data [31].

Methodology:

- Data Sources: Compiled data from WHO, CDC, EPA, NHANES, and USDA [31].

- Feature Selection: Employed multi-level feature selection, including Mutual Information (MI) and RFE.

- Models & Optimization: Tested Random Forest, LightGBM, and CatBoost, with optimization via Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Genetic Algorithms (GA) [31].

Performance Results:

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LightGBM + PSO | 98.87% | 98.59% | 99.27% | 98.91% |

| Other Ensemble Models | High performance | High performance | High performance | High performance |

Conclusion: The study confirmed that ensemble models, particularly when optimized and combined with rigorous feature selection like RFE, can achieve exceptional accuracy in predicting health risks, thereby informing public health policy [31].

Case Study 3: Environmental Metabarcoding Data Analysis

Objective: Benchmark the performance of feature selection and ML methods across 13 environmental metabarcoding datasets to analyze microbial communities [21].

Methodology:

- Datasets: 13 diverse environmental metabarcoding datasets [21].

- Workflow Evaluation: Assessed workflows involving data preprocessing, feature selection (including RFE), and machine learning models.

Key Findings:

| Scenario | Recommended Approach | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| General Use | Random Forest without feature selection | Robust performance for regression and classification [21]. |

| Performance Enhancement | Random Forest with RFE | Can improve performance across various tasks [21]. |

| High-Dimensional Data | Ensemble Models | Demonstrated robustness without mandatory feature selection [21]. |

Conclusion: While tree ensemble models are inherently robust, RFE remains a valuable tool for specific datasets and tasks, capable of enhancing model performance and interpretability in ecological studies [21].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My model performance drops significantly after applying RFE. What could be wrong? A: This is often caused by over-aggressive feature elimination. The step size (number of features removed per iteration) might be too large. Try eliminating a single feature per iteration instead of a percentage. Also, verify that your performance evaluation uses a robust method like k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting to a particular data split [21].

Q2: How do I handle highly correlated features in RFE? A: Random Forest with RFE can be effective for correlated features, as the model can handle redundancy better than linear models. However, if the correlation is perfect, it may arbitrarily choose one feature. You can pre-process data by removing features with a correlation coefficient above a specific threshold (e.g., >0.95) before applying RFE, or use domain knowledge to manually group correlated features.

Q3: When should I avoid using RFE? A: RFE may be unnecessary or even impair performance for tree ensemble models like Random Forest on some metabarcoding datasets, as these models have built-in robust feature importance measures [21]. RFE is also computationally expensive for extremely high-dimensional data (e.g., >100,000 features). In such cases, univariate filter methods (like Mutual Information) might be a more efficient first step for feature reduction.

Q4: The features selected by RFE are not scientifically interpretable. How can I improve this? A: Ensure the input features are biologically or chemically meaningful. Combine RFE with model interpretation tools like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [31]. SHAP provides consistent, theoretically grounded feature importance values that can help validate whether the selected features align with domain knowledge, thereby building trust in the model.

Q5: What is the relationship between large chemical datasets (like OMol25) and RFE? A: Large-scale datasets such as the OMol25, which contains over 100 million molecular snapshots, provide a rich, chemically diverse training ground for machine learning models [24]. RFE becomes crucial in this context to manage the computational complexity associated with the vast number of potential descriptors and features. It helps identify the most critical molecular properties that govern chemical behavior, leading to more efficient and accurate predictive models.

Integrating RFE into End-to-End Automated ML Frameworks like MatSci-ML Studio

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and why is it important for large chemical datasets? Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is a wrapper-based feature selection technique that works by recursively removing the least important features and retaining a subset that best predicts the target variable [10] [11]. For large chemical datasets, which are often high-dimensional, RFE helps reduce overfitting, improves model interpretability, and lowers computational costs [33].

Q2: How does MatSci-ML Studio integrate RFE into its automated workflow? MatSci-ML Studio features a comprehensive, end-to-end ML workflow with a graphical user interface. Its feature engineering and selection module includes a multi-strategy feature selection workflow, which allows users to employ advanced wrapper methods, including Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), to systematically reduce dimensionality [34].

Q3: My RFE process is very slow on a large dataset. What can I do to improve runtime? RFE is computationally intensive as it requires fitting multiple models [10] [33]. To improve runtime:

- Use a faster, simpler base estimator (e.g., Linear SVM instead of tree-based models) for the feature ranking step.

- Increase the number of features eliminated per step (

stepparameter). - Utilize the computational efficiency features of frameworks like MatSci-ML Studio, which is built on PyTorch Lightning and supports different hardware platforms (CPU, GPU, XPU) [35].

Q4: The final feature set from RFE seems to change drastically with small changes in the dataset. How can I improve stability? The instability of RFE can be due to highly correlated features or random variations in the training data [33]. To enhance stability:

- Use Enhanced RFE or RFE with cross-validation, which provide more robust feature selection by evaluating subsets more rigorously [10] [11].

- Consider combining RFE with filter methods as a pre-processing step to remove highly redundant features first.

Q5: Can I use RFE for both regression and classification tasks in materials science? Yes, RFE is a versatile algorithm that can be wrapped around any machine learning model that provides feature importance scores, making it suitable for both regression (e.g., predicting material properties) and classification tasks [34] [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Predictive Performance After RFE Problem: The model's accuracy decreases significantly after applying RFE. Solution:

- Diagnosis: The RFE process might be eliminating important features too aggressively.

- Actions:

- Adjust Stopping Criteria: Do not eliminate too many features too quickly. Reduce the

stepparameter so fewer features are removed in each iteration. - Validate with Cross-Validation: Use RFE with built-in cross-validation (e.g.,

RFECV) to automatically find the optimal number of features. - Try a Different RFE Variant: Benchmark different RFE variants. For instance, while RFE with tree-based models (RF-RFE) may yield strong performance, Enhanced RFE can offer a better balance between accuracy and feature reduction [10].

- Check the Base Model: Ensure the underlying estimator (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) is well-tuned, as its hyperparameters directly impact feature ranking.

- Adjust Stopping Criteria: Do not eliminate too many features too quickly. Reduce the

Issue 2: High Computational Resource Consumption Problem: The RFE process is taking too long or consuming excessive memory, especially with large-scale chemical data. Solution:

- Diagnosis: Wrapper methods like RFE are inherently computationally expensive [33].

- Actions:

- Leverage Hardware Acceleration: Utilize frameworks like MatSci-ML Studio that support GPU/XPU acceleration to speed up model training within the RFE loop [35].

- Implement Strategic Feature Pre-Filtering: Apply a fast filter method (e.g., correlation analysis) before RFE to reduce the initial feature pool, thus lessening the computational load on the wrapper method [34].

- Parallelize Workflows: Use the distributed data parallel training capabilities of integrated frameworks to run experiments across multiple nodes [35].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Feature Selection Results Problem: RFE selects different feature subsets when run multiple times on the same dataset. Solution:

- Diagnosis: This is a known challenge with RFE related to feature stability, often caused by correlated features or model randomness [33].

- Actions:

- Set a Random State: For models that have inherent randomness (e.g., Random Forest), set a fixed random seed for reproducible results.

- Use Ensemble RFE: Run RFE multiple times with different data subsamples and aggregate the results to create a more stable, consensus-based feature set.

- Explore Hybrid Methods: Combine RFE with embedded methods; for example, use Lasso regression for initial feature coefficient estimation before applying RFE [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Benchmarking RFE Variants on a Large Chemical Dataset This protocol outlines how to evaluate different RFE integration strategies, based on methodologies used in EDM and healthcare [10] [11].

1. Objective: Compare the performance of Standard RFE, RF-RFE (Random Forest), and Enhanced RFE on a large chemical dataset.

2. Materials & Dataset Setup:

- Dataset: Use a structured, tabular dataset of composition-process-property relationships (e.g., from the Materials Project or OQMD, accessible via MatSci-ML Studio) [35].

- Software: Utilize an automated ML framework like MatSci-ML Studio for its integrated project management and version control, which ensures reproducibility [34].

3. Procedure: 1. Data Preprocessing: Within the framework, handle missing data and outliers using interactive cleaning tools (e.g., KNNImputer). 2. Model & RFE Configuration: - Standard RFE: Wrap RFE around a linear Support Vector Machine (SVM). - RF-RFE: Use a Random Forest estimator within the RFE process. - Enhanced RFE: Implement an RFE variant that incorporates cross-validation for feature set evaluation. 3. Execution: For each variant, run the RFE process to identify the top 50 most important features. 4. Evaluation: Train a final predictive model (e.g., XGBoost) on the selected features from each variant and evaluate on a held-out test set using metrics like R² (regression) or Accuracy (classification).

4. Expected Outcomes and Analysis:

- Performance: RF-RFE is expected to show strong predictive performance due to its ability to capture complex interactions.

- Efficiency: Enhanced RFE should achieve substantial dimensionality reduction with minimal accuracy loss.

- Computational Cost: RF-RFE will likely have the highest runtime, while Standard RFE will be the fastest [10].

Table 1: Computational Characteristics of RFE Variants

| RFE Variant | Base Estimator | Relative Predictive Performance | Relative Computational Cost | Feature Set Stability | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard RFE | Linear SVM | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Initial fast filtering, high-dimensional data |

| RF-RFE | Random Forest | High | High | Low | Maximizing accuracy, complex feature interactions |

| Enhanced RFE | Algorithm-specific | High (with minimal loss) | Moderate | High | Balanced approach for practical applications |

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for RFE Experiments

| Item | Function in the RFE Workflow |

|---|---|

| Structured Tabular Data | The foundational input for RFE, containing material compositions, processes, and target properties. |

| Base ML Estimator | The core model (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) used by RFE to rank feature importance. |

| Automated ML Framework (e.g., MatSci-ML Studio) | Provides an integrated, code-free environment for data management, RFE execution, and result tracking [34]. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Library (e.g., Optuna) | Automates the tuning of the base estimator's parameters, which is critical for accurate feature ranking [34]. |

| Validation Metric (e.g., MAE, R², Accuracy) | The performance measure used to guide the feature elimination process and select the optimal feature subset. |

Workflow Visualization

RFE in Automated ML Framework

Optimizing RFE Performance and Overcoming Common Pitfalls

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My dataset has over a million samples. Is it practical to run standard RFE on it? Standard Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE), which removes one feature at a time, is often computationally prohibitive for datasets of this scale [36]. However, several practical strategies make RFE feasible. The key insight is that large datasets often contain significant data redundancy; research on materials datasets has shown that up to 95% of the data can often be removed for training with little impact on the in-distribution prediction performance [37]. Leveraging this by working with informative subsets of your data, combined with optimized RFE variants, can reduce computation from potentially months to hours or days [36].

2. What is the most effective way to reduce the computational cost of RFE? The most impactful approach is a two-pronged strategy: reducing data volume and using a more efficient RFE variant.

- Reduce Data Redundancy: Before even starting RFE, analyze your dataset for redundancy. Techniques like uncertainty-based active learning can help identify and remove redundant samples, creating a much smaller but highly informative training set [37].

- Use an Efficient RFE Variant: Instead of removing one feature per iteration, use algorithms like RFE-Annealing, which removes a large chunk of less important features in early iterations and progressively finer chunks in later iterations. This can reduce computation time from 58 hours to just 26 minutes on a sizable dataset while maintaining comparable accuracy [36].